Abstract

Polyphenols have received great attention as important phytochemicals beneficial for human health. They have a protective effect against cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer and diabetes. The utilization of polyphenols as natural antioxidants, functional ingredients and supplements is limited due to their low stability caused by environmental and processing conditions, such as heat, light, oxygen, pH, enzymes and so forth. These disadvantages are overcome by the encapsulation of polyphenols by different methods in the presence of polyphenolic carriers. Different encapsulation technologies have been established with the purpose of decreasing polyphenol sensitivity and the creation of more efficient delivery systems. Among them, spray-drying and freeze-drying are the most common methods for polyphenol encapsulation. This review will provide an overview of scientific studies in which polyphenols from different sources were encapsulated using these two drying methods, as well as the impact of different polysaccharides used as carriers for encapsulation.

1. Introduction

Polyphenols are secondary plant metabolites consisting of an aromatic ring to which one or more hydroxyl groups are attached [1]. These compounds are synthesized through plant development and/or as a plant’s response to environmental stress conditions [2]. Even when they are at low concentrations in plants, polyphenols protect them from predators or ultraviolet damage [3]. They are known as natural antioxidants and therefore have many beneficial effects on health (e.g., antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant effect, etc.) [4,5,6]. The health benefits of polyphenols are influenced by the matrix in which they are processed and ultimately consumed [7]. One well-known property of polyphenols is the positive influence on diabetes and obesity due to the possibility of inhibition of digestive enzymes such as α-glucosidase and α-amylase [8]. Anthocyanins are a group of polyphenols responsible for the red, blue and purple color of fruit and vegetables. The major anthocyanin found in most plants is cyanidin-3-glucoside, correlated with reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and antioxidant potential in in vitro conditions [9,10]. Flavan-3-ols are a subgroup of flavonoids and their main representatives are catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin and epigallocatechin-3-gallate. These compounds are abundantly found in green tea, strawberries and black grapes. Studies showed a positive effect of catechin in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, diabetes and in cancer treatment [11]. Gallic acid, a polyphenol from a group of phenolic acids, a subgroup of hydroxybenzoic acids was the subject of many studies that have proven its significant antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, antimicrobial and antimutagenic effects [12].

Due to the presence of unsaturated bonds in their structures, polyphenols are sensitive to various environmental conditions such as the presence of oxygen, light and water [2]. The presence of water is the most important factor, due to its essentiality in most chemical reactions [13,14]. In the food industry, thermal processes are mostly used to obtain edible, microbiologically safe foods, to improve digestibility, and to modulate their textures, flavors and colors [14]. During these processes, structural changes occur leading to the degradation of polyphenols which are often ignored [14]. In order to maintain their stability, they need to be protected, and one of the possible ways is encapsulation in which polysaccharides, proteins, lipids or combinations thereof can be utilized as carriers. In that way, the preservation of polyphenolic properties is achieved over longer periods because the carrier materials represent a barrier to oxygen and water [2]. By encapsulation of polyphenols, besides increased stability, mitigation of unpleasant tastes or flavors, controlled release, improved aqueous solubility and bioavailability can be achieved [3]. Drying has effect on the material’s appearance and chemical composition. It also prolongs shelf life and inhibits enzymatic degradation and microbial growth of materials or foods [15]. Adequate selection of a drying method and operating conditions yields foods with slight changes in appearance and maximum retention of bioactive compounds [15].

Spray-drying is a commonly used method for encapsulating due to its simple regulation and control, limited cost, and continuous operation [16]. Freeze-drying is also often used for encapsulation of thermosensitive compounds and materials with some disadvantages such as higher unit cost and long processing time [17]. Suitable selection of carrier and encapsulation technique leads to successful incorporation and retention of bioactive compounds [2]. Food enriched with encapsulated polyphenols can be a versatile and cost-effective approach [14]. In addition, this approach enables other features such as controlled release, improved bioaccessibility and bioavailability for absorption [14].

This paper will provide the literature review of spray-drying and freeze-drying for the encapsulation of polyphenols from different sources. Moreover, with emphasis on polysaccharides, the influence of carrier materials on polyphenol encapsulation will be reviewed.

2. Polyphenols

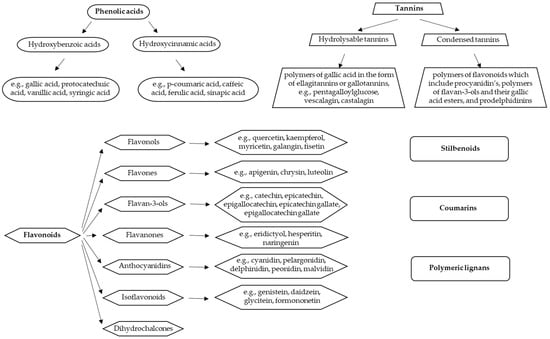

Polyphenols include various different compounds divided into several classes: phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenoids, tannins, coumarins, and polymeric lignans (Figure 1) [18]. Their chemical structure may vary from simple to complex. The largest group of polyphenols is that of flavonoids, divided into several subgroups (flavonols, flavones, flavanols, flavanones, anthocyanidins, isoflavonoids, and chalcones) [19]. Their structure consists of two phenyl groups linked with a three-carbon bridge. According to the degree of oxidation and unsaturation of the three-carbon segment, they differ from each other. Different sugar molecules can be attached to the hydroxyl groups of flavonoids. They are usually in a glycosidic form which improves their solubility in water. Acylation of the glycosides where sugar hydroxyls are derivatized with acid (such as ferulic and acetic acids) is also common. The interconnection between several basic units of polyphenols makes larger and more complex structures, such as hydrolysable tannins and condensed tannins [20]. Phenolic acids represent a large group of hydrophilic polyphenols and they are constituted of a single phenyl ring [14]. Due to the diversity in the structures of polyphenols, they possess different properties (such as solubility and polarity) [20].

Figure 1.

Classification of polyphenols and the most important representatives of individual groups (adapted from Dobson et al. [18]).

Polyphenols exist ubiquitously in vegetables and fruits and their consummation is very desirable [14]. Various positive bioactivities of polyphenols toward pathologic conditions are known, through their antioxidant properties. These molecules are capable of donating hydrogen atoms and electrons [14]. One such activity is the anticancer property of polyphenols [21]. Hollman et al. [22] reviewed the antioxidant activities of polyphenols within the organism and their positive impact on cardiovascular health. In addition, polyphenols contribute to the sensory quality of the products (wine, jellies, juices, chocolate, etc.). They affect color, bitterness, turbidity, etc. [6,23]. Due to their many functional properties, polyphenols are of great interest to the food, chemical and pharmaceutical industries [2].

3. Encapsulation

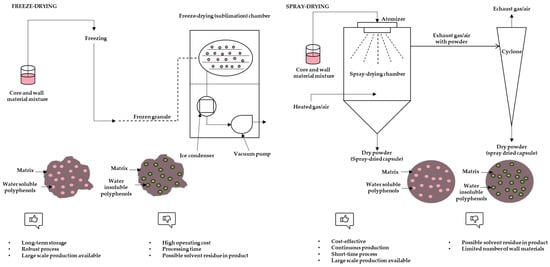

Encapsulation is the process of entrapment of active compounds into particles to enable isolation or controlled release of given compounds. The main role of encapsulation is the protection of sensitive active compounds from degradation [17]. Various techniques can be used for encapsulation depending on core material, size of required particles, physical state, or sensitivity to high temperature [24]. These techniques include freeze-drying, spray-draying, extrusion, fluidized bed coating, spray-cooling/chilling, coacervation, liposome entrapment, cocrystallization, vacuum-drying, centrifugal suspension separation, nanoencapsulation, molecular inclusion and emulsification [13]. Encapsulation with coacervation is based on phase separation of a hydrocolloid from an initial solution and subsequent deposition of the formed coacervate phase around an active ingredient suspended in media. It is considered an expensive technique but very beneficial for high-value compounds [25]. Extrusion is a process based on passing a polymer solution with active ingredients through a nozzle (or syringes) into a gelling solution. Usually the used wall material is sodium alginate while calcium chloride solution serves for capsule forming. It is easy to execute on a laboratory scale with long shelf-life capsules, while scale-up of this technique is expensive and demanding with a limited choice of wall materials [26]. Emulsification includes the dispersion of one liquid into the other (two immiscible liquids) in the form of droplets. An emulsifier is required for stabilization and by application of drying, a powder form of encapsulates can be achieved [26]. The molecular inclusion method is also known as host-guest complexation. Apolar guest molecules are trapped inside the apolar cavity of host molecules (such as cyclodextrins) through non-covalent bonds [26]. Cocrystallization techniques include modification of the crystalline structure of sucrose to an irregular agglomerated crystal with porous structure in which active ingredient can be incorporated [25]. Fluidized bed coating is also referred to as fluidized bed processing, air suspension coating, or spray coating. The principle is that coating is applied to the particles suspended in the air. For this technique a wide range of coating materials such as aqueous solutions of cellulose, starch derivates, gums, or proteins is suitable [27]. Spray chilling is also known as spray cooling, prilling, or spray congealing. The basic principle is similar to spray drying with the key difference of using a cooling chamber instead of a drying chamber. Regarding coating materials, only lipid-based materials (fats, waxes, fatty acids, fatty alcohols and polyethylene glycols) are used [27]. Nanoencapsulation is an innovative trend in the field of food technologies. The final results are particles of diameters ranging from 1 to 1000 nm. The term nanoparticles includes nanospheres and nanocapsules. The first one has a matrix-type structure where the active ingredients can be adsorbed at the sphere surface or encapsulated in particles. In nanocapsules, the active ingredient is limited to a cavity with an inner liquid core surrounded by a polymeric membrane. Nanoparticles have a larger surface area, increased solubility, enhanced bioavailability and improved controlled release [25]. Freeze-drying and spray-drying are the most frequently employed methods for removing water from foods with encapsulation effects [28]. A schematic view of these methods is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic view of freeze-drying and spray-drying process, characteristics of particles and advantages and disadvantages of methods (adapted from Fang and Bhandari, [25]; Grgić et al., [26]).

The wide range of polyphenol biological activities can be restricted due to their low stability, low bioavailability, and unpleasant flavor [14]. Encapsulation of polyphenols improves their stability during storage and can also be used to achieve the masking of unpleasant flavors in foods (such as bitter taste and astringency) [2]. Food with high intensity of bitterness and astringency elicit negative consumer reactions. Compounds responsible for that are flavanols and flavonols. Flavan-3-ol monomers such as catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, epicatechin gallate and epigallocatechin gallate as well as their oligomers proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins) are abundant in wine and tea. It can be said that flavanols are the main compounds that cause bitterness and astringency in tea and red wine (with the exception of caffeine in tea) [29]. The method selected for encapsulation must be based on the polyphenol’s characteristics such as chemical structure, thermophysical stability, solubility, affinity to coating material, target properties such as particle size and morphology, among others [14].

3.1. Freeze-Drying

Freeze-drying, also known as lyophilization, is a drying technique based on the phenomenon of sublimation. This technique allows the long-term preservation of heat-sensitive and oxidation-prone compounds, as well as foods and other biological materials, since it is conducted at low temperatures and under vacuum [30]. This method does have disadvantages such as higher unit cost and processing time [17]. Despite those issues, freeze-drying is widely used to obtain high-value food products and is considered a standard method for encapsulation in most research studies [30].

The freeze-drying process includes the complete freezing of samples, ice sublimation (primary drying) and desorption of remaining unfrozen/bond water (secondary drying). In the first step, the freezing rate determines the formation and size of ice crystals. Large ice crystals formed by the slow rate of freezing can sublimate easily and increase the primary drying rate. In primary drying, the shelf temperature will increase using a vacuum to start the sublimation. It is necessary that product temperature is 2–3 °C below the temperature level of collapse, at which the product can lose its macroscopic structure. The endpoint of the primary drying phase is a key parameter to determine because the increased temperature (in the secondary drying) before the sublimation of all ice could collapse the final product quality [30].

3.2. Spray-Drying

In the food industry spray-drying is the most frequently used technique. It is economical, flexible and can be used continuously with easy scale-up [13]. Advantages over the other methods are higher effectiveness and shorter drying time [16]. This technique is based on transforming a material from liquid form into powder form [24]. However, when spray-drying is used for polyphenol encapsulation, conditions must be optimized in order to avoid an accelerated degradation [17]. Depending on process conditions and formulations, spray-drying micrometric capsules can be core-and-shell, multiple core or matrix type [14]. Before spray-drying, a solution or suspension of polyphenols with carriers must be obtained, followed by atomizing into a hot air stream.

3.3. Particle Morphology

Spray-dried particles are usually spherical with varying diameters and concavities, regardless of the choice of coating material [17]. Mean size range of such particles range from 10 µm to 100 µm [25]. The formation of concavities is associated with shrinkage of the particles due to dramatic loss of moisture after cooling. On the other hand, powders obtained by freeze-drying have a flake-like structure or one that resemble broken glass. The reason could be the low temperature of the process which results in the absence of forces to break the frozen liquid into droplets. Differences in surface morphology of freeze-dried powders could be due to different coating agents. For example, powder with soybean protein and maltodextrin as coating materials had a spherical porous structure, while powders with only maltodextrin lost their porous structure [17]. The final particle size of freeze-dried powders depends on the grinding procedure, not on the drying process [31].

3.4. Polyphenol Carriers

Materials used for encapsulation, which makes a protective shell, should be biodegradable and food-grade. They also must be able to establish a barrier between an internal phase and its surroundings [13]. Selection of coating material influences encapsulation efficiency and encapsulates stability [24]. Commonly used materials are carbohydrates such as maltodextrin, cyclodextrins, gum Arabic and modified starch. These materials lead to an increase in the glass transition temperature of the dried product. By trapping a bioactive compound, they enable its preservation against stickiness, temperature, enzymatic and chemical changes [13].

Maltodextrin is one of the most often used carriers, having a low bulk density and viscosity and high solubility at high solids contents [16,24]. It is obtained by partial hydrolysis of starch using an enzyme or acid. Maltodextrin has the ability to retain volatile compounds. Its disadvantages, such as low emulsibility, are often overcome by combining maltodextrin with other materials [16].

Cyclodextrins are safe for food applications and broadly studied as hosts for encapsulation [3]. The commonly used cyclodextrins are α-, β- and γ-cyclodextrin. They possess a hydrophobic central cavity and a hydrophilic external part [32]. Due to this structure, guest molecules (different organic and inorganic molecules) are able to be accommodated into the cavity. The hydrophilic external surface provides aqueous solubility [3,24]. The application of cyclodextrins in spray-drying is limited due to their low water solubility (1.8%). This limitation can be overcome by cyclodextrin modification. An example of such modification is hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin which has a higher water solubility (60%) and thus can be subjected to drying techniques [24].

Gum Arabic consists of galactose, rhamnose, arabinose, 4-O-methyglucuronic acid and glucuronic acid and its natural source is the acacia plant (stems and branches). Furthermore, its low viscosity and high solubility, stable emulsions and high retention rates of volatile compounds have enabled a broad range of applications of this polymer [16]. On the other hand, some disadvantages such as low production yield and a consequently higher price make it less accessible [33].

4. Application of Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying for Encapsulation of Polyphenols

During freeze-drying of foods rich in polyphenols, cells are disrupted, and therefore exposed to an increased enzyme activity (polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase enzyme) upon thawing, and the degradation of the polyphenols can occur [34,35]. However, some studies have shown that the amount of polyphenols may increase after this process. The flavonol content in freeze-dried onions increased, which can be attributed to the release of polyphenols from the matrix [36]. Wilkowska et al. [24] observed that freeze-dried powders had 1.5 times higher retention of anthocyanins than spray-dried ones. From studying the values of total polyphenols content, it has been noticed that when applying spray-drying, 73% of compounds were lost. Encapsulates of polyphenols in coffee grounds extract achieved by freeze-drying and spray-drying with maltodextrin, gum Arabic and maltodextrin:gum Arabic (1:1) as carrier materials were evaluated for total polyphenols content and flavonoid content. The results showed that freeze-drying was a more effective technique for retention of polyphenols and flavonoids and maltodextrin a more efficient carrier. On the other hand, spray-dried particles possessed a higher antioxidant activity than freeze-dried ones [2]. One interesting investigation was conducted on developing novel protein ingredients fortified with blackcurrant concentrate. As a source of protein, they used whey protein isolate and freeze-drying and spray-drying techniques. Encapsulates obtained by spray-drying possessed a higher total polyphenols content, anthocyanins content and encapsulation efficiency compared to the freeze-dried ones [28]. Robert et al. [37] encapsulated polyphenols from pomegranate juice and ethanolic extract by spray-drying, and observed a higher encapsulation efficiency when soy protein isolates were used compared to the maltodextrin. On the other hand, capsules with maltodextrin, stored at 60 °C in an oven for 56 days, resulted in a lower degradation of polyphenols and anthocyanins. Wu et al. [38] investigated the physicochemical properties and nutritional characteristics of functional cookies with incorporated encapsulated blackcurrant polyphenols. For the preparation of encapsulates, whey protein isolate and blackcurrant concentrate were used and the applied encapsulating techniques used were freeze-drying and spray-drying. The results of total polyphenols content were higher for enriched cookies with freeze-dried encapsulates than for those with spray-dried encapsulates.

Ersus and Yurdagel [39] observed that during spray-drying, maltodextrins with higher DE (equivalents of dextrose) are more sensitive to higher outlet air temperatures. Heating could lead to structural deformations due to shorter chains and oxidation of free glucose functional groups at the open ends. Their results confirmed the encapsulation of black carrot anthocyanins using maltodextrin DE 20-21 for 20% feed solid content and 160–180 °C drying temperatures. Gomes et al. [40] obtained a higher retention of papaya pulp polyphenol and flavonoid compounds in spray-dried products than in freeze-dried products. Vanillic acid had an enormous decrease of 76% after freeze-drying. Enzymatic reactions with the action of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase are likely to occur in the freeze-drying process. Moreover, the disrupted material structure caused by the formation of ice crystals and lower exposure to oxygen can cause the liberation of these enzymes. Furthermore, artepillin C concentration increased three times after drying, which can lead to the false-positive results of the spray-drying technique. It is known that processes at high temperatures may release more bound polyphenols which cannot be detected in fresh samples [40]. Saikia et al. [41] encapsulated polyphenols from Averrhoa carambola pomace using maltodextrin and freeze-drying and spray-drying methods. The authors obtained a higher encapsulation efficiency in freeze-dried encapsulates. It might be that some polyphenols are destroyed during spray-drying, due to their sensitivity to heat. During the spray-drying process, fine misty droplets with increased surface are obtained and due to that higher surface, they are more exposed to heat. Moreover, during atomization, some amount of carrier can be eliminated from the core material and the partially covered capsules thus obtained can be destroyed by heat. During the freeze-drying process, no atomization or heat exposure are present. These authors also observed a decrease in surface polyphenols with higher maltodextrin content [41]. On the other hand, high inlet temperatures applied in spray-drying are short-lived, so this technique is less destructive for bioactive compounds compared to the other conventional thermal processes [42]. It has to be taken into consideration that in the freeze-drying process, obtained powders are ground and this process increases the possibility of contact with air, resulting in oxidation reactions [42,43]. In the freeze-drying process, the formation of a sawdust-like form is usual, leading to a lower surface area/volume ratio. Additionally, by the spray-drying process, smaller sized microspheres with a larger surface area were obtained using the spray-drying process (for the same amount of material as for freeze-drying), which led to the deterioration of the surface polyphenols [2]. Considering the short time of exposure to high temperatures during spray-drying, this technique seems good for the encapsulation of polyphenols. Dealing with thermosensitive and highly valuable materials, freeze-drying is a suitable method [33]. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 present the studies on the encapsulation of polyphenols using freeze-drying and spray-drying techniques.

Table 1.

Studies of spray-drying application for encapsulation of polyphenols from different sources.

Table 2.

Studies of freeze-drying application for encapsulation of polyphenols from different sources.

Table 3.

Studies of spray-drying (SD) and freeze-drying (FD) applications for encapsulation of polyphenols from different sources.

5. Application of Encapsulated Polyphenols in Food Products

Due to the increasing awareness of consumers toward health and the consumption of food that promotes health, the enrichment of food products with encapsulated polyphenols and replacement of artificial food additives with natural ones is strongly supported [78]. Over the last few years, applying encapsulated polyphenols in food products has been on the rise. In reviewing scientific papers, those dealing with encapsulated polyphenols with polysaccharides were singled out.

Yogurt has high water content and a low pH value which makes it challenging to incorporate polyphenols with poor solubility. Encapsulated polyphenols into hydrophilic wall materials can overcome these shortcomings [78]. Robert et al. [37] encapsulated polyphenols from pomegranate with maltodextrin and soybean protein isolates and incorporated them in yogurt. Encapsulates with maltodextrin had the lower degradation rate during storage. Moreover, mushroom extract rich in polyphenols, encapsulated with maltodextrin crosslinked with citric acid, was incorporated in yogurt [79]. In a study of El-Messery et al. [77], polyphenols extracted from apple peel were encapsulated with maltodextrin, whey protein and gum Arabic using spray-drying and freeze-drying. The obtained powders were used in supplementing yogurt. Results showed no significant influence of powders on the physiochemical and texture properties of samples. The authors suggested that those encapsulated polyphenols can be used as a functional food ingredient for yogurt. One interesting study dealt with encapsulation of eugenol-rich clove extract in maltodextrin and gum Arabic by spray-drying. These encapsulates were incorporated into soybean oil for increasing antioxidant activity. Potatoes fried in that oil had better sensorial properties than ones fried in oil with butylated hydroxytoluene (synthetic antioxidant) [80]. Encapsulated polyphenols can also be incorporated into bread. Ezhilarasi et al. [81] enriched bread with encapsulated Garcinia fruit polyphenols with maltodextrin and whey protein isolates. Furthermore, green tea polyphenols, encapsulated using β-cyclodextrin and maltodextrin by freeze-drying and spray-drying, were added to bread. Bread quality (volume and crumb firmness) didn’t change compared to the control sample [82]. Furthermore, anthocyanins from red onion skins were encapsulated using gum Arabic, soy protein isolate and carboxymethyl cellulose as wall materials, and applying the gelation and freeze-drying techniques. The powder, which has the highest encapsulation efficiency, has been added to crackers and results showed improved antioxidant activity of these enriched crackers. The authors suggest the suitability of applying such additives in bakery products [83]. Table 4 presents some other studies that dealt with incorporating encapsulated polyphenols with polysaccharides using freeze-drying and spray-drying techniques into food products.

Table 4.

Selected studies on the incorporation of encapsulated polyphenols into food products.

6. Conclusions

Bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols attract a lot of attention from scientists, functional food product developers and consumers due to their health-promoting effects. Most of these compounds are chemically unstable and encapsulation techniques have been widely applied in order to enhance their stability. Nevertheless, freeze-drying is still assumed to be the most suitable for heat-sensitive compounds. The adequate method of encapsulation depends on the type of polyphenol and material for encapsulation, however. Therefore, it cannot be generally said that freeze-drying is better than spray-drying or vice versa. Choosing a polyphenol carrier is important in order to achieve effective encapsulation. While freeze-drying will definitely result in a higher quality and better bioactivity retention compared with conventional spray drying methods, its application is excessively expensive, time consuming and limited in throughput capacity for most commercial applications. Therefore, in order to increase the number and variety of products on the consumer markets, as well as the application range of encapsulated polyphenols, new technologies will need to be researched and if necessary developed.

This paper contributes to the insights into previously researched and optimized encapsulating conditions for a large number of polyphenol-rich materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., A.P. and J.Š.; methodology, I.B. and A.P.; investigation, I.B. and A.P.; writing—I.B.; writing—review and editing, M.K., A.P. and J.Š.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was part of the project PZS-2019-02-1595 which has been fully supported by the “Research Cooperability” Program of the Croatian Science Foundation, funded by the European Union from the European Social Fund under the Operational Program for Efficient Human Resources 2014–2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Quirόs-Sauceda, A.E.; Palafox-Carlos, H.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Bello-Perez, L.A.; Álvarez-Parrilla, E.; de la Rosa, L.A.; Gonzáles-Cόrdova, A.F.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Dietary fiber and phenolic compunds as functional ingredients: Interaction and possible effect after ingestion. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Ramirez, M.J.; Orrego, C.E.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Encapsulation of antioxidant phenolic compounds extracted from spent coffee grounds by freeze-drying and spray-drying using different coating materials. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malapert, A.; Reboul, E.; Tourbin, M.; Dangles, O.; Thiéry, A.; Ziarelli, F.; Tomao, V. Characterization of hydroxytyrosol-β-cyclodextrin complexes in solution and in the solid state, a potential bioactive ingredient. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 102, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velderrain-Rodríguez, G.R.; Palafox-Carlos, H.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Chen, C.Y.O.; Robles-Sánchez, M.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Phenolic compounds: Their journey after intake. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma, M.V.; Espin, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Interaction between phenolics andgut microbiota: Role in human health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6485–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Interactions between cell wall polysaccharides and polyphenols. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 1808–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardum, N.; Glibetic, M. Polyphenols and their interactionswith other dietary compounds: Implications for human health. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 84, 103–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiner, M.; Blake, D.A.; Fullerton, M.L.; Suner, S.S.; Sunol, A.K.; Sahiner, N. Enhancement of biocompatibility and carbohydrate absorption control potential of rosmarinic acid through crosslinking into microparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: Colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, S.; Mathew, S.; Nair, P.; Ramadan, W.S.; Vazhappilly, C.G. Health benefits of cyanidin-3-glucoside as a potent modulator of Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suner, S.S.; Sahiner, M.; Mohapatra, S.; Ayyala, R.S.; Bhethanabotla, V.R.; Sahiner, N. Degradable poly(catechin) nanoparticles as a versatile therapeutic agent. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2021, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, P.V.; Nkambule, B.B.; Jack, B.; Mkandla, Z.; Mutize, T.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Tiano, L.; Louw, J.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E. Inflammation and oxidative stress in an obese state and the protective effects of gallic acid. Nutrients 2019, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramírez, M.J.; Giraldo, G.I.; Orrego, C.E. Modeling and stability of polyphenol in spray-dried and freeze-dried fruit encapsulates. Powder Technol. 2015, 277, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Saroglu, O.; Karadag, A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Zoccatelli, G.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Gonzales-Aguilar, G.A.; Ou, J.; Bai, W.; Zamarioli, C.M.; et al. Available technologies on improving the stability of polyphenols in food processing. Food Front. 2021, 2, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Lech, K.; Nowicka, P.; Hernandez, F.; Figiel, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Influence of Different Drying Techniques on Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant Capacity and Colour of Ziziphus jujube Mill. Fruits. Molecules 2019, 24, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Dang, T.T.; Nguyen, T.V.L.; Dung Nguyen, T.T.; Mguyen, N.N. Microencapsulation of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) anthocyanins: Effects of different carriers on selected physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of spray-dried and freeze-dried powder. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Golding, J.; Vuong, Q.; Pristijono, P.; Stathopoulos, C.; Scarlett, C.; Bowyer, M. Encapsulation of Citrus By-Product Extracts by Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying Using Combinations of Maltodextrin with Soybean Protein and ι-Carrageenan. Foods 2018, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dobson, C.C.; Mottawea, W.; Rodrigue, A.; Buzati Pereira, L.B.; Hammami, R.; Power, A.K.; Bordenave, N. Impact of molecular interactions with phenolic compounds on food polysaccharides functionality. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 90, 135–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, A.; Jaganath, I.B.; Clifford, M.N. Dietary phenolics: Chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1001–10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L. Interactions of polyphenols with carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellion, P.; Digles, J.; Will, F.; Dietrich, H.; Baum, M.; Eisenbrand, G.; Janzowski, C. Polyphenolic apple extracts: Effects of raw material and production method on antioxidant effectiveness and reduction of DNA damage in Caco-2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6636–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.H.; Cassidy, A.; Comte, B.; Heinonen, M.; Richelle, M.; Richling, E.; Richling, E.; Serafini, M.; Scalbert, A.; Sies, H.; et al. The biological relevance of direct antioxidant effects of polyphenols for cardiovascular health in humans is not established. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 989S–1009S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le Bourvellec, C.; Renard, C.M.G.C. Interactions between Polyphenols and Macromolecules: Quantification Methods and Mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 213–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkowska, A.; Ambroziak, W.; Czyżowska, A.; Adamiec, J. Effect of Microencapsulation by Spray-drying and Freeze Drying Technique on the Antioxidant Properties of Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) Juice Polyphenolic Compounds. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 66, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, Z.; Bhandari, B. Encapsulation of polyphenols—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgić, J.; Šelo, G.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Role of the Encapsulation in Bioavailability of Phenolic Compounds. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.; Islam Shishir, M.R.; Ferdowsi, R.; Tanver Rahman, M.R.; Van Vuong, Q. Micro and nano encapsulation, retention and controlled release of flavor and aroma compounds: A critical review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Hui, X.; Mu, J.; Brennan, M.A.; Brennan, C.S. Functionalization of whey protein isolate fortified with blackcurrant concentrate by spray-drying and freeze-drying strategies. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesschaeve, I.; Noble, A.C. Polyphenols: Factors influencing their sensory properties and their effects on food and beverage preferences. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 330S–335S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatta, S.; StevanovicJanezic, T.; Ratti, C. Freeze-Drying of Plant-Based Foods. Foods 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Li, P.; Kong, L.; Xu, B. Microencapsulation of curcumin by spray drying and freeze drying. LWT 2020, 132, 109892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Khiev, D.; Can, M.; Sahiner, M.; Biswal, M.R.; Ayyala, R.S.; Sahiner, N. Chemically cross-linked poly(β-cyclodextrin) particles as promising drug delivery materials. Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 6238–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepelevs, I.; Stepanova, V.; Galoburda, R. Encapsulation of Gallic Acid with Acid-Modified Low Dextrose Equivalent Potato Starch Using Spray-and Freeze-Drying Techniques. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 68, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shofian, N.M.; Hamid, A.A.; Osman, A.; Saari, N.; Anwar, F.; Dek, M.S.; Hairuddin, M.R. Effect of Freeze-Drying on the Antioxidant Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Selected Tropical Fruits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4678–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tan, J.J.Y.; Lim, Y.Y.; Siow, L.F.; Tan, J.B.L. Effects of drying on polyphenol oxidase and antioxidant activity of Morus alba leaves. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gregorio, M.R.; Regueiro, J.; González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Simal-Gándara, J. Changes in antioxidant flavonoids during freeze-drying of red onions and subsequent storage. Food Control 2011, 22, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, P.; Gorena, T.; Romero, N.; Sepulveda, E.; Chavez, J.; Saenz, C. Encapsulation of polyphenols and anthocyanins from pomegranate (Punica granatum) by spray-drying. Int. J. Food Sci. 2010, 45, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Hui, X.; Stipkovits, L.; Rachman, A.; Tu, J.; Brennan, M.A.; Brennan, C.S. Whey protein-blackcurrant concentrate particles obtained by spray-drying and freeze-drying for delivering structural and health benefits of cookies. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 68, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersus, S.; Yurdagel, U. Microencapsulation of anthocyanin pigments of black carrot (Daucus carota L.) by spray drier. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, W.F.; França, F.R.M.; Denadai, M.; Andrade, J.K.S.; da Silva Oliveira, E.M.; de Brito, E.S.; Rodrigues, S.; Narain, N. Effect of freeze- and spray-drying on physico-chemical characteristics, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of papaya pulp. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2095–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, S.; Mahnot, N.K.; Mahanta, C.L. Optimisation of phenolic extraction from Averrhoa carambola pomace by response surface methodology and its microencapsulation by spray and freeze drying. Food Chem. 2015, 171, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Lv, Y. Degradation kinetic of anthocyanins from rose (Rosa rugosa) as prepared by microencapsulation in freeze-drying and spray-drying. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 2009–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, S.A.; Hameed, A.; Nazir, Y.; Naz, T.; Wu, Y.; Suleria, H.; Song, Y. Microencapsulation and the Characterization of Polyherbal Formulation (PHF) Rich in Natural Polyphenolic Compounds. Nutrients 2018, 10, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Bandera, D.; Villanueva-Carvajal, A.; Dublán-García, O.; Quintero-Salazar, B.; Dominguez-Lopez, A. Assessing release kinetics and dissolution of spray-dried Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) extract encapsulated with different carrier agents. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibin, L.I.; Wu, L.; Weng, M.; Tang, B.; Lai, P.; Chen, J. Effect of different encapsulating agent combinations on physicochemical properties and stability of microcapsules loaded with phenolics of plum (Prunus salicina lindl.). Powder Technol. 2018, 340, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.C.P.A.; Nogueira, R.I.; Paim, D.R.S.F.; Gouvêa, A.C.M.S.; Godoy, R.L.O.; Peixoto, F.M.; Pacheco, S.; Freitas, S.P. Effects of encapsulating agents on anthocyanin retention in pomegranate powder obtained by the spray-drying process. LWT 2016, 73, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroschi, L.C.; Brito de Souza, V.; Echalar-Barrientos, M.A.; Tulini, F.L.; Comunian, T.A.; Thomazini, M.; Baliero, C.C.; Roudaut, G.; Genovese, M.I.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Production of spray-dried proanthocyanidin-rich cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) extract as a potential functional ingredient: Improvement of stability, sensory aspects and technological properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.F.; Yusoff, M.M.; Gimbun, J. Assessment of phenolic compounds stability and retention during spray-drying of Orthosiphon stamineus extracts. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 37, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sansone, F.; Mencherini, T.; Picerno, P.; d’Amore, M.; Aquino, R.P.; Lauro, M.R. Maltodextrin/pectin microparticles by spray-drying as carrier for nutraceutical extracts. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, H.S.; Torun, M.; Özdemir, F. Spray-drying of the mountain tea (Sideritis stricta) water extract by using different hydrocolloid carriers. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saénz, C.; Tapia, S.; Chávez, J.; Robert, P. Microencapsulation by spray-drying of bioactive compounds from cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica). Food Chem. 2009, 114, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Anthocyanin stability and antioxidant activity of spray-dried açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) juice produced with different carrier agents. Int. Food Res. J. 2010, 43, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.I.; Stringheta, P.C.; Teófilo, R.F.; de Oliveira, I.R.N. Parameter optimization for spray-drying microencapsulation of jaboticaba (Myrciaria jaboticaba) peel extracts using simultaneous analysis of responses. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bušić, A.; Komes, D.; Belšćak-Cvitanović, A.; VojvodićCebin, A.; Špoljarić, I.; Mršić, G.; Miao, S. The Potential of Combined Emulsification and Spray-drying Techniques for Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Leaves. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, S.; Generalov, R.; Pereira, M.C.; Peres, I.; Juzenas, P.; Coelho, M.A. Epigallocatechin gallate-loaded polysaccharide nanoparticles for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Nanomed. J. 2011, 6, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AniesraniDelfiya, D.S.; Thangavel, K.; Natarajan, N.; Kasthuri, R.; Kailappan, R. Microencapsulation of Turmeric Oleoresin by Spray-drying and In Vitro Release Studies of Microcapsules. J. Food Process Eng. 2015, 38, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan Mahdavi, S.; Jafari, S.M.; Assadpoor, E.; Dehnad, D. Microencapsulation optimization of natural anthocyanins with maltodextrin, gum Arabic and gelatin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 85, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archaina, D.; Vasile, F.; Jiménez-Guzmán, J.; Alamilla-Beltrán, L.; Schebor, C. Physical and functional properties of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) extract spray-dried with maltodextrin-gum arabic mixtures. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.C.; Germer, S.P.M.; Alvim, I.D.; Vissotto, F.Z.; de Aguirre, J.M. Influence of carrier agents on the physicochemical properties of blackberry powder produced by spray-drying. Int. J. Food Sci. 2012, 47, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczykolan, E.; Kurek, M.A. Use of guar gum, gum arabic, pectin, beta-glucan and inulin for microencapsulation of anthocyanins from chokeberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias-Cervantes, V.S.; Chávez-Rodríguez, A.; García-Salcedo, P.A.; García-López, P.M.; Casas-Solís, J.; Andrade-González, I. Antimicrobial effect and in vitro release of anthocyanins from berries and Roselle obtained via microencapsulation by spray-drying. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, V.; Baeza, R.; Galmarini, M.V.; Zamora, M.C.; Chirife, J. Freeze-Drying Encapsulation of Red Wine Polyphenols in an Amorphous Matrix of Maltodextrin. Food. Bioproc. Tech. 2011, 6, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichai, K.; Muangrat, R. Effect of different coating materials on freeze-drying encapsulation of bioactive compounds from fermented tea leaf wastewater. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangrat, R.; Ravichai, K.; Jirarattanarangsri, W. Encapsulation of polyphenols from fermented wastewater of Miang processing by freeze drying using a maltodextrin/gum Arabic mixture as coating material. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, P.; Kylli, P.; Heinonen, M.; Jouppila, K. Storage Stability of Microencapsulated Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) Phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11251–11261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsebaie, E.M.; Essa, R.Y. Microencapsulation of red onion peel polyphenols fractions by freeze drying technicality and its application in cake. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milea, Ș.A.; Aprodu, I.; Vasile, A.M.; Barbu, V.; Râpeanu, G.; Bahrim, G.E.; Stănciuc, N. Widen the functionality of flavonoids from yellow onion skins through extraction and microencapsulation in whey proteins hydrolysates and different polymers. J. Food Eng. 2019, 251, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Sassi, C.; Marcet, I.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M.; Fattouch, S. Egg yolk protein as a novel wall material used together with gum Arabic to encapsulate polyphenols extracted from Phoenix dactylifera L pits. LWT 2020, 131, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudziuvelyte, L.; Marksa, M.; Sosnowska, K.; Winnicka, K.; Morkuniene, R.; Bernatoniene, J. Freeze-Drying Technique for Microencapsulation of Elsholtziaciliata Ethanolic Extract Using Different Coating Materials. Molecules 2020, 25, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Nosić, M.; Pichler, A.; Ivić, I.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Apple Fibers as Carriers of Blackberry Juice Polyphenols: Development of Natural Functional Food Additives. Molecules 2022, 27, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Citrus Fiber/Blackberry Juice Complexes. Molecules 2021, 26, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukoja, J.; Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Formulation and Stability of Cellulose-Based Delivery Systems of Raspberry Phenolics. Processes 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuck, L.S.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Microencapsulation of grape (Vitis labrusca var. Bordo) skin phenolic extract using gum Arabic, polydextrose, and partially hydrolyzed guar gum as encapsulating agents. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rezende, Y.R.R.S.; Nogueira, J.P.; Narain, N. Microencapsulation of extracts of bioactive compounds obtained from acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) pulp and residue by spray and freeze drying: Chemical, morphological and chemometric characterization. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadi, D.W.; Emire, S.A.; Hagos, A.D.; Eun, J.B. Physical and Functional Properties, Digestibility, and Storage Stability of Spray- and Freeze-Dried Microencapsulated Bioactive Products from Moringa stenopetala Leaves Extract. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2020, 156, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Wojdyło, A.; Honke, J.; Ciska, E.; Andlauer, W. Drying-induced physico-chemical changes in cranberry products. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Messery, T.M.; El-Said, M.M.; Demircan, E.; Ozçelik, B. Microencapsulation of natural polyphenolic compounds extracted from apple peel and its application in yoghurt. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2019, 18, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfanian, M.; Ali Sahari, M. Improving functionality, bioavailability, nutraceutical and sensory attributes of fortified foods using phenolics-loaded nanocarriers as natural ingredients. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, C.R.L.; Heleno, S.A.; Fernandes, I.P.M.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Barreiro, M.F. Functionalization of yogurts with Agaricusbisporus extracts encapsulated in spray-dried maltodextrin crosslinked with citric acid. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, D.; Bhattacharjee, P. Comparative evaluation of the antioxidant efficacy of encapsulated and un-encapsulated eugenol-rich clove extracts in soybean oil: Shelf-life and frying stability of soybean oil. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhilarasi, P.N.; Indrani, D.; Jena, B.S.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Microencapsulation of Garciniafruit extract by spray drying and its effect on bread quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 94, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasrija, D.; Ezhilarasi, P.N.; Indrani, D.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Microencapsulation of green tea polyphenols and its effect on incorporated bread quality. LWT 2015, 64, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, F.; Condurache, N.N.; Horincar, G.; Constantin, O.E.; Turturicặ, M.; Stặnciuc, N.; Aprodu, I.; Croitoru, C.; Râpeanu, G. Value-Added Crackers Enriched with Red Onion Skin Anthocyanins Entrapped in Different Combinations of Wall Materials. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papillo, V.A.; Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Garino, C.; Arlorio, M.; Coïsson, J.D. Spray-dried polyphenolic extract from Italian black rice (Oryza sativa L., var. Artemide) as new ingredient for bakery products. Food Chem. 2018, 269, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papillo, V.A.; Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Garino, C.; Coïsson, J.D.; Arlorio, M. Cocoa hulls polyphenols stabilized by microencapsulation as functional ingredient for bakery applications. Food Res. Int. 2018, 115, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, A.; Cilek, B.; Hasirci, V.; Sahin, S.; Sumnu, G. Storage and Baking Stability of Encapsulated Sour Cherry Phenolic Compounds Prepared from Micro- and Nano-Suspensions. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, L.L.; Klevorn, C.M.; Hess, B.J. Minimizing the Negative Flavor Attributes and Evaluating Consumer Acceptance of Chocolate Fortified with Peanut Skin Extracts. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, S2824–S2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, S.A.; Jafari, S.M.; Assadpour, E.; Ghorbani, M. Storage stability of encapsulated barberry’s anthocyanin and its application in jelly formulation. J. Food Eng. 2016, 181, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).