Abstract

Current trends in Analytical Chemistry are focused on the development of more sustainable and environmentally friendly procedures. However, and despite technological advances at the instrumental level having played a very important role in the greenness of the new methods, there is still work to be done regarding the sample preparation stage. In this sense, the implementation of new materials and solvents has been a great step towards the development of “greener” analytical methodologies. In particular, the application of deep eutectic solvents (DESs) has aroused great interest in recent years in this regard, as a consequence of their excellent physicochemical properties, general low toxicity, and high biodegradability if they are compared with classical organic solvents. Furthermore, the inclusion of DESs based on natural products (natural DESs, NADESs) has led to a notable increase in the popularity of this new generation of solvents in extraction techniques. This review article focuses on providing an overview of the applications and limitations of DESs in solvent-based extraction techniques for food analysis, paying especial attention to their hydrophobic or hydrophilic nature, which is one of the main factors affecting the extraction procedure, becoming even more important when such complex matrices are studied.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, humans are living in a globalized world, where it is necessary to guarantee the supply of food to a population of around 7900 million people, as well as to ensure its safe consumption, which becomes a difficult and essential task. The fact that each country has its own food regulations clearly complicates this scenario. In this sense, the development of new analytical methodologies that allow the effective and reliable analysis of foods, including the determination of pathogenic microorganisms and contaminants that can cause food poisoning or trigger food-related illnesses, are essential to guarantee the safety and quality of the food consumed around the world.

Current trends at both industrial and academia levels, are focused on the development and application of sustainable processes from an economical and environmental point of view. In this context, the development of new analytical processes is marked by the principles of the Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which emerged from the Green Chemistry principles in the 1990s, looking for a balance between an improvement in the quality of the results and the creation of more sustainable analytical procedures [1,2]. There is no doubt that the rapid development of analytical instrumentation, both in the miniaturization of the systems and in the improvement of sensitivity and selectivity, has contributed enormously in this regard. However, sample preparation still plays a very important role in any analytical process, especially in the determination of compounds at trace levels and/or very complex samples analysis, where the numerous interferences and the poor distribution of the analytes in the sample matrix make an enrichment of the target analytes and a clean-up of the sample necessary [1,3].

Different strategies have been followed in order to contribute to the development of new analytical procedures from a sustainable perspective. In this regard, many efforts have been made in the miniaturization of conventional sample preparation and separation techniques, as well as in the search for new materials and solvents that, after being used, have a low impact in the environment. In particular, since green chemistry was introduced, the search for alternatives to volatile toxic organic solvents has been one of the main challenges in sample preparation [4]. In this sense, several solvents of lower toxicity and improved properties (high thermal and chemical stability, adjustable viscosity, and good extraction capacity) have been introduced in this field, among which ionic liquids (ILs), switchable polarity solvents, supramolecular solvents and deep eutectic solvents (DESs) [4,5] can be found. Although all these new classes of solvents are playing a very important role in the development of new analytical processes, in recent years, DESs have aroused great interest due to their excellent physical–chemical properties and their eco-friendliness, which has led them to monopolize a large part of the latest publications related to solvent-based analytical techniques [6].

DESs, firstly introduced in 2003 by Abbot et al. [7], result from the combination of a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) and a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) at a specific molar ratio and temperature. This new generation of solvents is characterized by a lower melting point with respect to the HBA and HBD separately as a consequence of a charge delocalization produced by hydrogen bonds formation. Despite DESs have several features in common with ILs (easy synthetic procedures and variable viscosity, density and polarity), their synthesis is even cheaper and simpler, and they generally present lower toxicity, which have contributed to their popularity as extraction solvents [4,5].

The use of DESs in sample preparation have brought several benefits not only from an operational point of view, but also for the nontoxic and biodegradable nature of their constituents in many cases, such as quaternary ammonium and phosphonium salts, amines, alcohols, or carboxylic acids. However, the use of some non-environmentally friendly reagents during their synthesis is also quite common. As a result, many DESs still pose an environmental challenge because of their toxicity for living organisms [8]. In this sense, the latest trends have been focused on the preparation of natural DESs (NADESs), based on the use of natural products, such as amino acids, terpenes, sugars and natural organic acids, giving place to less toxic DESs with higher biodegradability and/or without toxicity, which undoubtedly contribute to the development of even more sustainable analytical procedures [4,5].

Since the unusual solvent properties of DESs at room temperature were shown, these have been classified into four categories attending to their components as a result of the wide variety of anionic and/or cationic species with which they could be formed [9]. Type I DESs are composed of non-hydrated metal halides and quaternary ammonium or imidazolium salts, while type II use hydrated metal halides as HBA. Type III DESs have shown particular versatility and have attracted the most attention, with applications in a wide variety of fields. This group includes DESs formed by mixing a quaternary ammonium salt (i.e., choline chloride, ChCl) with a wide range of HBDs that contain functional groups such as amides, carboxylic acids and alcohols. Considering that, the first DES designed by Abbott et al. [7], composed of ChCl and urea in a 1:2 molar ratio, and which was hydrophilic, could be classified as type III, as well as the DESs synthesized in the vast majority of the works collected in this review work. Finally, type IV is composed of a non-hydrated metal halide and a HBD.

As mentioned above, due to the great success of DESs, the number of publications related to their application in sample preparation techniques has grown rapidly, leading in some cases to the publication of incomplete and/or unreliable information. One of the issues that is often controversial is the definition of a DES, as the term “deep” should be clearly defined, since it is usual to find eutectic mixtures with the same starting components, but at different molar ratios. As an example, for the hydrophilic mixture between ChCl and oxalic acid, eutectic point properties have been described at molar ratios of 1:1 [10], 1:2 [11] and 1:3 [12]. However, it is not clear if all these combinations may be named as DESs, which highlights the great debate that exists on whether these mixtures could really be classified as DESs or, on the contrary, should be simply designated as “eutectic mixtures” or “eutectic melts”. There is also some debate associated with the hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of a DES. Generally, it is stated that a water insoluble non-polar component as HBD and a water-soluble quaternary ammonium salt as HBA are necessary to obtain a hydrophobic DES (HDES). However, there is great controversy in this regard, since these types of solvents partially dissolve in water, leading to the loss of the DES. Thus, some authors have suggested that a DES should be defined as hydrophobic when all its components are insoluble in water, in such a way that they present sufficient stability in this type of solvent. Otherwise, they should be defined as “quasi-hydrophobic” DESs. In this sense, it is also worth mentioning the importance of carrying out characterization studies of the DES before and after the extraction procedure, since in many cases, especially when aqueous samples are analysed, the DES nature is finally lost, since water can act as HBA or HBD, resulting in a structure and/or polarity change [6].

Apart from the previously described, and despite the broad spectrum of DESs that can be synthesised, few information about the methodology to follow for the choice of the components of a DES to be used for specific applications can be found in the literature. Generally, hydrophilic DESs are suitable for the extraction of analytes from low-polar food samples, such as edible oils [13], fish [14] or rice flour [15], while HDESs are adequate for the extraction of inorganic and organic compounds from aqueous food samples, such as fruit juices [16], coffee [17] or tea beverages [18]. However, in certain cases, they can also be used in other matrices if a suitable dispersing or emulsifying agent is added to facilitate the analytes extraction, so this rule is not always fulfilled. Besides, there are many aspects affecting the extraction efficiency of the DES that make a prediction of the most suitable DES components, such as the polarity or acidity of the target analytes, as well as the viscosity of the resulting DES, which can be also affected by the addition of certain amounts of water.

This review article aims at providing a general overview on the application of DESs and NADESs as solvents in different solvent-based sample preparation approaches in food analysis. Considering the existing debate regarding the hydrophobicity of a DES, special attention has been paid to the hydrophilic or hydrophobic nature of the DESs applied in this field, due to the key role it plays during the extraction procedure, describing and discussing some specific and relevant applications.

2. Application of Hydrophilic Deep Eutectic Solvents

Since the first DES was synthesized in 2003 by Abbott et al. [7] and until 2015, most of the DESs reported in the literature were generally made up of hydrophilic compounds and, as a consequence, were soluble in water. Despite that fact clearly limits their application in certain sample preparation approaches, this type of DESs is still very useful for the extraction of different compounds of interest through simple, green and efficient procedures.

Among the main properties of hydrophilic DESs, their density values greater than that of water stand out [19]. Furthermore, and as mentioned before, these kinds of DESs are also characterized by their miscibility with polar solvents, such as water or methanol (MeOH), which is due to the hydrophilic nature of their components that contain highly electronegative groups and can form hydrogen bonds through special cases of dipole–dipole interactions [20]. Table 1 shows works in which hydrophilic DESs have been used for the extraction and determination of a great variety of analytes in different food samples. Most of the DESs shown in the table were prepared by simple mixing of their components with constant stirring and heating at temperatures below 100 °C until a transparent and homogeneous mixture was obtained, and in neither case a purification process was needed.

Table 1.

Application of hydrophilic DESs in sample preparation procedures for food analysis.

As can be seen in the table, hydrophilic DESs have been used with very good performances for the preconcentration and extraction of an extensive diversity of analytes, including both organic compounds (i.e., antioxidants [25], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [65], pesticides [53,54,55,56], amino acids [24], phenolic compounds and caffeine [10,35,38,52,60], flavonoids [29,32], anthocyanins [31,34,58], mycotoxins [33,37], aflatoxins [39], sex hormones [36], antibiotics [41], preservatives [67], organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) [44,57], curcumin [22,25,40,45], polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) [43], and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) [43,72]) and metals (Cd, Zn, As, Sb, Fe, Cu, Se, Mn, Pb, Cr, Co, Hg and Al [11,12,13,14,15,23,26,27,28,42,46,47,48,49,50,51,61,62,63,64,68,71]) from matrices of different natures and low polarity, such as edible oils [13,23,35,39,43,66,70,73], non-alcoholic beverages and fruit juices [38,44,53,54,56,57,62,67,71], vegetables [21,26,28,29,34,46,50,51,53,55,56,61,68], fruits [29,31,55,58], teas [22,40,42,49,50,65], spices [22,29,40], milk [24,41,48,62,63], water [12,46,62,63], fish tissues [11,14,27,42,46,47], eggs [62], flours [15,32,33,37,69], rice [64] and meat [42,46,51].

Taking into consideration the GAC principles, the downscaling of sample treatment has shown some advantages, such as low consumption of samples (10 μL–25 mL), low amounts/volumes of reagents and organic solvents (10–400 μL), a reduction and simplification of procedures, and high enrichment factors. For this reason, although some applications in which larger volumes of DES (even reaching 20 mL) can be found [21,24,29,32,35,37,41,58,69], most hydrophilic DESs have been applied in miniaturized liquid-based extraction techniques (see Table 1). In this sense, DESs have been applied in the three main modes of liquid-phase microextraction (LPME): dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME), hollow-fibre liquid-phase microextraction (HF-LPME) and single drop microextraction (SDME). Among them, the speed, simplicity and low-cost of DLLME has made it the most widely used, allowing the preconcentration of different analytes in a wide variety of food matrices. It is important to highlight that in most cases, the hydrophilic DESs have been dispersed through various physical processes (manual agitation [53], ultrasound [14,30,38,39,44,46,47,50,51,61,62,63,70,73] or vortex stirring [12,13,22,33,40,43,45,48,49,52,59,63,69], temperature change [57], or air bubbled when pulling–pushing a syringe [42,55,64,71]), using few microliters of the extraction solvent and without the need for organic solvents. Additionally, some applications in which the drop obtained after the extraction stage has been solidified can be found [48,68], which allows the recovery of the complete drop and makes the procedure simpler, safer and faster [73].

However, and as it has been previously mentioned, the miscibility of hydrophilic DESs with water generally limits their direct application to aqueous samples. For this reason, in these cases, a dispersing or emulsifying agent (generally tetrahydrofuran, THF, or acetonitrile, ACN) is usually added to obtain a cloudy solution, achieving the separation of the two liquid phases after a shaking and centrifugation step in DES-based DLLME procedures [12,40,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,56]. Nonetheless, the addition of this solvent has negative consequences since it may reduce the environmental friendliness and increases the laboratory hazards. On the other hand, its properties, such as viscosity or density, are those that will allow better or worse retention of the analytes [1,6]. In general, hydrophilic DESs tend to have a relatively high viscosity, which makes an effective mass transfer in the extraction processes difficult, so a common practice to reduce their viscosity to suitable values consists in the addition of a known amount of water to hydrophilic DESs using the heating method [15,21,24,25,29,31,33,35,37], in which known concentrations of the three components (HBD, HBA and water) are mixed under constant stirring in a water bath (generally at 50 °C) until a homogeneous and transparent liquid is obtained. In certain cases, water has even been replaced by an organic solvent, such as ethanol (EtOH) or MeOH [43].

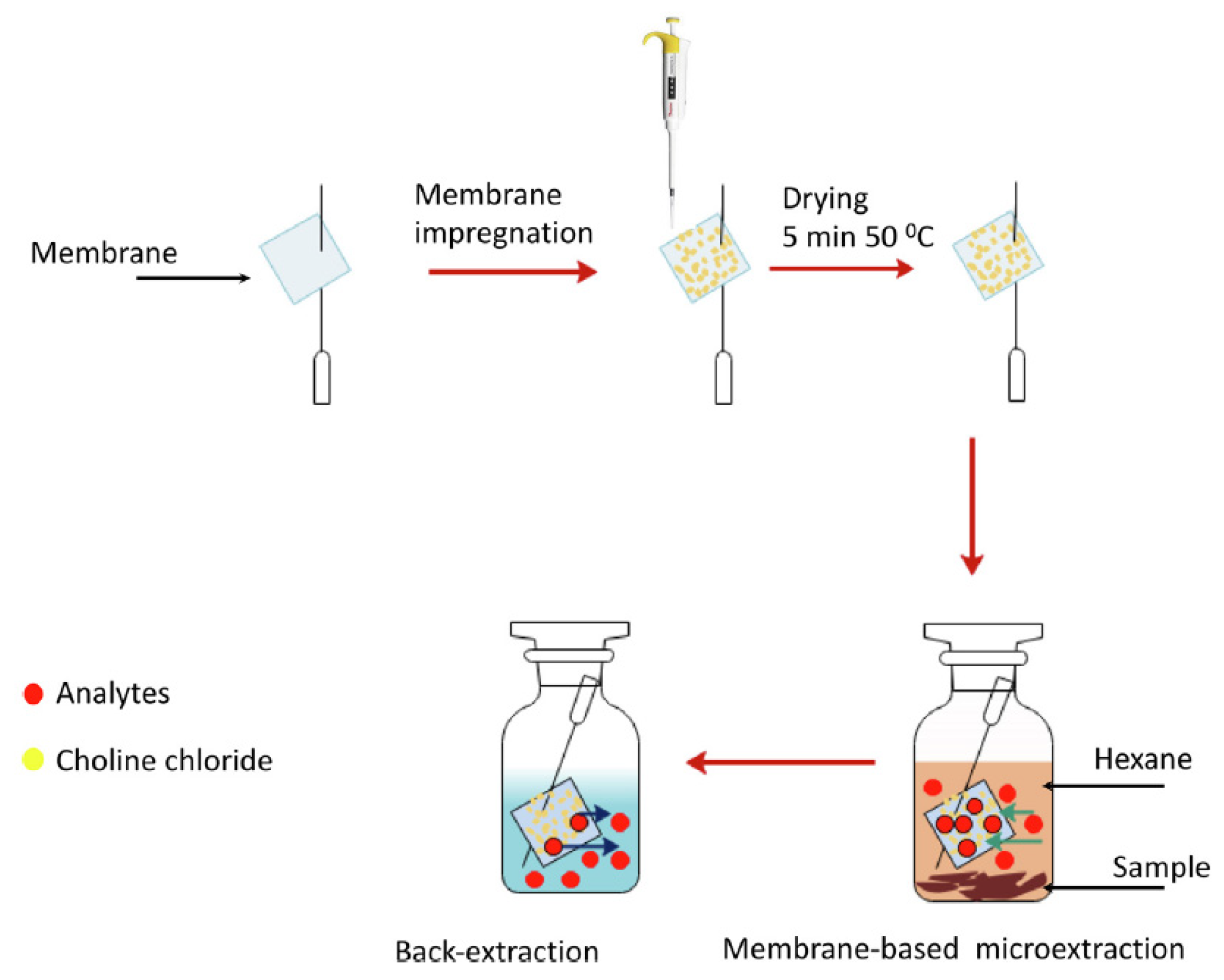

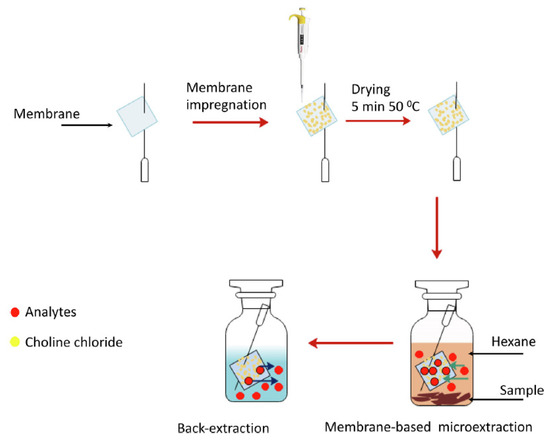

Both viscosity and density values vary depending on the components of DES. For example, in the case of viscosity, DESs containing ChCl as HBA are more viscous when HBD is an acid (values up to 14,480 cP in ChCl:citric acid, 1:1 [74]) than when it is an alcohol (values lower than 400 cP [75]) due to the greater presence of hydrogen bonds between HBA and HBD. In addition, within the acids, citric acid contributes to a higher viscosity DESs, with values up to 437,768 cP (glucose:citric acid 1:1 [76]). Furthermore, the effect of the addition of water can be clearly observed in ChCl:citric acid (1:1) DES, whose viscosity decreases to 4080.8 cP [76] when amounts less than 50% of water are added, otherwise the eutectic properties would be lost, and dissolution of the individual DES components in water would occur. On the other hand, the change in the molar ratio also affects the viscosity of DES. In this way, in some cases if the proportion of ChCl is decreased, the viscosity is increased, such as ChCl:glycerol, which increases from 234 cP (1:1) to 301 cP (1:2), or ChCl:fructose, where it increases from 28.31 cP (1:1) to 72.42 cP (1:2) [75]. In the case of density, it can be ranged between 1.0 and 1.5 g/mL. The different values will depend on the molecular weight of the components, so for example, ChCl:maltose (1:2) will have a higher density (1.431 g/mL [77]) than ChCl:1,2-propanediol (1:2, 1.04 g/mL [78]), as if changing the HBA by one of higher molecular weight such as citric acid (citric acid:glucose, 1:1, 1.442 g/mL [76] compared to ChCl:glucose (1:1, 1.27 g/mL [79]). Furthermore, the addition of water decreases the density of DESs, for example, when adding 40% water to citric acid:glucose DES, the density decreases to a value of 1.246 g/mL [76]. From a procedural point of view, it is worth mentioning the work of Shishov and co-workers [60], in which the authors synthesized in situ different deep eutectic mixtures (DEMs) based on the combination of the analytes (phenols, HBDs) and ChCl (HBA) supported in a hydrophilic porous membrane. For this, square membranes (10 × 10 mm) were picked by syringe needle, as can be seen in Figure 1, and impregnated with a ChCl solution. After drying in an incubator, it was placed in a vial containing the sample mixed with hexane and shaken. After that, the syringe needle with the membrane was withdrawn, the hexane was evaporated and was introduced into a vial containing ultra-pure water. Then, it was shaken to promote analytes desorption, since this membrane type allows microextraction from organic sample phase and back-extraction of the analytes into aqueous phase. Finally, the aqueous phenol solution obtained was injected in the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system coupled to a fluorescence detector (FD). Several types of membrane were studied, being the poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-tetrafluoroethylene) the one that provided maximum extraction recovery. This membrane-based microextraction was used for the separation of six phenols from smoked sausages and smoked fish samples, showing good selectivity due to the formation of DEMs between ChCl and analytes. Good sensitivity with limits of detection (LODs) between 0.3 and 1.0 μg/kg and high extraction capacity with extraction recovery values ranging from 70 to 80% were obtained.

Figure 1.

Deep eutectic mixture membrane-based microextraction process diagram. Reprinted from Shishov et al. [60] with permission of Elsevier.

Hydrophilic DESs have also been combined with other materials and used in the extraction of the compounds of interest. For example, a magnetic nanofluid (MNF) consisting of a DES (ChCl:thiacetamide, 1:2 molar ratio) based magnetic multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) was successfully applied by Shirani et al. [71], combining the excellent properties of DESs with the magnetic features of magnetic nanomaterials. In this work, the authors sonicated the mixture of magnetic MWCNTs and the previously synthesized DES to obtain a homogenous black gel called DES-MNF. Then, the sample and the DES-MNF were mixed by rapidly suctioning and dispensing repeatedly for six times with a syringe, after which a turbid solution was obtained. The upper phase was eliminated by retaining the DES-MNF with an external magnet and a 1 M nitric acid solution was added to desorb the analytes. Finally, 10 μL of the supernatant solution were injected in an electrothermal atomic absorption spectroscopy (ETAAS) system. The proposed method showed high extraction capacity and good sensitivity for the determination of Cd, Pb, Cu and As from walnut, rice, tomato paste, spinach, orange juice, black tea and water samples.

In addition to the previously mentioned combinations, similar to what is made with ILs, DESs-based polymeric sorbents can also be synthesized and have been applied in food analysis. These poly(DES)s have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional sorbents used in solid-phase extraction (SPE) techniques, as they combine the properties of DESs and those of porous materials. As an example, Abdolhosseini et al. [68] prepared a DES of tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBABr) and acrylic acid (1:2 molar ratio) and polymerized it under solventless condition, through a cost-efficient and energy-saving photopolymerization process. DES polymerization consisted of mixing under a nitrogen atmosphere and at room temperature for 60 min the previously prepared DES, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (used as crosslinker) and 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (used as photoinitiator) in a 100:10:1 weight ratio. The resulting homogeneous mixture was exposed to UV light and washed to remove any unreacted monomers. The synthesized polymeric DES was used for preconcentration of lead from vegetables such as onion, celery, carrot and tomato, as well as from mineral water samples through a dispersive SPE procedure, to later proceed to its quantification by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy. The results showed that the polymeric DES allowed obtaining acceptable selectively, low LOD (2 μg/L) and high stability since it can be reused 16 times without a significant reduction in the recovery.

As it can be seen, Table 1 also compiles several works in which hydrophilic NADESs have been used for the extraction of a wide variety of analytes. In order to demonstrate that their application constitutes a greener and more environmentally friendly alternative extraction procedure, in some of these works, its greenness has been evaluated according to the penalty points of an analytical eco-scale [80] calculated by considering hazards, amount of reagents, energy and waste, just like López et al. [24] did, who only obtained two penalty points in their developed method for the extraction of three free seleno-amino acids in lyophilized samples of seleno-biofortified sheep milk and cow milk powder and determination by liquid chromatography (LC)-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Another method used to evaluate the toxicity of hydrophilic NADESs has been bacterial growth inhibition. In this way, Huang et al. [30] performed a culture with two Gram-positive (S. aureus and L. monocytogenes) and two Gram-negative (E. coli and S. enteritidis) bacteria, which were incubated in a nutrient agar medium with a filter paper soaked with each of the thirteen NADESs they tested to extract rutin from tartary buckwheat hull. It was shown that none of the NADESs led to a decrease in the growth of bacteria with the exception of glycerol:L-arginine NADES, because, despite the fact that the individual components are nontoxic and were approved by the European Food Safety Authority [81,82], there occurs a charge delocalization as a result of a hydrogen bond, which makes the eutectic mixture toxic [83].

After the application of the DESs as extraction solvents in the above-mentioned procedures, analytes have generally been determined by HPLC or ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) using different detection systems, such as UV [21,29,30,31,32,44,52,57,70,73], diode array detector (DAD) [10,25,35,36,59,67], FD [37,39,60,65], tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [33], as a result of their appropriate solubility in the mobile phase, or ICP-MS, this last for free seleno-amino acids determination [24]. However, they have also been separated and detected by UV-Vis spectrophotometry [14,22,38,40,45], atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) [11,23,47,68], slotted quartz tube-flame AAS [48,49], hydride generation AAS [12], graphite furnace AAS [15,26,42], ETAAS [13,27,46,50,51,71] and ICP-optical emission spectroscopy (OES) [28]. Gas chromatography (GC) coupled to electron capture detection (ECD) [54,72] or flame ionization detection (FID) [53,55,56] have also been used, although in a very reduced number of applications. Furthermore, in some cases, after performing the developed method, samples were injected into a GC-MS for better identification of the analytes. However, in other cases, as previously commented, because the DESs used are highly viscous, they had to be mixed before performing the extraction technique with a solvent, such as MeOH or EtOH, to decrease their viscosity and, in this way, avoid irreproducibility problems during injection into the chromatographic system. As an example, the work of Solaesa and co-workers can be highlighted [43], who synthesized a DES based on ChCl and phenol with a 1:2 molar ratio, which they mixed in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with EtOH to be used in the extraction of five PBDEs and three OCPs from fish oils using vortex-assisted liquid–liquid microextraction (VA-LLME)-GC-MS/MS with 5′-fluoro-3,3′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether and triphenylphosphate as internal standards.

The great extraction capacity shown by the hydrophilic DESs together with the sophisticated detection techniques used, have allowed to obtain low LODs, in the order of μg/L or μg/kg in most cases as can be seen in Table 1, or even ng/L or ng/kg [12,13,39,42,46,65,71].

3. Applications of Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents

Despite the previously mentioned limitations of hydrophilic DESs, it was not until 2015 that van Osch et al. [84] presented some DESs with hydrophobic properties for the first time. These DESs were characterized by the immiscibility of their two components with water, resulting in a low water content after being mixed with this solvent (approx. 1.8 wt%) and a low leaching of the quaternary ammonium salts (approx. 1.9 wt%). These hydrophobic solvents consisted of a long chain alkyl quaternary ammonium salt (e.g., tetrabutylammonium chloride (N4444Cl), methyltrioctylammonium chloride (N8881Cl), tetraheptylammonium chloride (N7777Cl), tetraoctylammonium chloride (N8888Cl), methyltrioctylammonium bromide (N8881Br) and tetraoctylammonium bromide (N8888Br)) and poorly soluble carboxylic acids (e.g., decanoic acid), and their extraction capacity was evaluated by extracting volatile fatty acids from diluted aqueous solutions. Since then, multiple HDESs based on neutral compounds have also been proposed, including combinations of monoterpenes with fatty acids [85], tetraalkylammonium halides with fatty acids and alcohols [86,87], fatty acids with fatty acids [88], and monoterpenes with monoterpenes [17]. Many of the HDESs have also been designed and classified following the same classification that had been previously proposed and that was already used for hydrophilic DESs (type I, II, III and IV), but due to their need to be stable in the aquatic environment, they are mainly grouped into type III (a combination of a quaternary salt (HBA) with a HBD) and type IV (a combination of metal chloride with HBD) [89].

The main difference between hydrophilic and hydrophobic DESs lies in the presence of long alkyl chains or cycloalkyl groups, which reduces the effect of hydrophilic zones (e.g., charges of the salts) and hydrophilic groups (e.g., carboxylate and hydroxyl groups) [1,90]. These eutectic mixtures have unique properties of density, acidity, polarity, viscosity and volatility, which provide a good extraction capability through a careful selection of their components [89]. As a consequence, it has been found that the extraction efficiency of HDESs depends to a great extent on their immiscibility with water as a function of the difference in density. Thus, in contrast to hydrophilic DESs, HDESs generally have lower density values than water [19], since the increase in the length of the alkyl chain of the salt components results in a decrease in density (within 0.80–1.10 g/mL) [91], although, for example, DESs containing fluorinated alcohol (e.g., hexafluoroisopropanol, HFIP) are generally denser than water (around 1.5 g/mL) [59]. In addition, it is necessary to take into account that the greater the difference in density between DES and water, the more easily the separation between the two phases will occur [91].

On the other hand, most HDESs have a melting temperature below 25 °C, which allows them to be used as solvents or reaction media in different applications at room temperature [90,92]. However, it should be noted that increasing the alkyl chain of the component acting as HBD, like carboxylic acids, increases the melting point of HDESs, while increasing the alkyl chain of the ammonium salt results in a lower melting point [90]. It is also important to highlight that the hydrophobicity of DESs is also affected by the structure of their individual components in such a way that the longer the alkyl chain of the components (both in HBA and HBD), the lower the solubility in the aqueous phase of each of them as well as of the DES [89]. Regarding the viscosity of HDESs, it is usually high because the hydrogen bonds that are established between its components, decrease the movement of the HDES molecules. However, these eutectic mixtures, like the hydrophilic ones, show a wide range of viscosity (between 2.6 and 5985.0 cP), since it depends on the components that make up the HDES, especially the one that acts as HBA, which allows us to design solvents for specific tasks depending on their handling capacity [90]. Among them, it is possible to differentiate between neutral HDESs (such as menthol:decanoic acid 1:2, 27.7 cP) that are less viscous than ionic HDESs (such as N4444Cl:decanoic acid 1:2, 265.3 cP), and within the latter, the HDESs that contain the bromide anion (such as N8881Br:decanoic acid 1:2, 576.5 cP) are more viscous than those that contain the chlorine anion (such as N8881Cl:decanoic acid 1:2, 472.6 cP) [91]. Likewise, as in hydrophilic DESs, an increase in temperature leads to a decrease in viscosity [93,94].

As mentioned above, HDESs are mainly characterized by their immiscibility in the aqueous phase. For this reason, it is necessary to study the stability of HDESs in contact with water, so that there is no leaching or loss of its components towards the aqueous phase, as well as that their water content is practically zero [84]. Many of the HDESs formed through the combination of a hydrophobic and a hydrophilic component have been found to be unstable in water. This is because the hydrophilic component tends to leach into the aqueous phase. For example, Florindo et al. [95] showed that the DES formed by DL-menthol:dodecanoic acid (2:1, molar ratio) was stable in contact with water compared to DL-menthol:acetic acid (1:1, molar ratio) and N4444Cl:octanoic acid (1:2, molar ratio) when comparing the 1H NMR spectra of each one of them. As a consequence, Shishov et al. [6] proposed a new term for these unstable HDESs in aqueous phase: “quasi-hydrophobic DES”, since it would not be appropriate to consider them as HDESs. In most of the works collected in this review, a study has not been carried out to verify if the extraction is due to a HDES or to one of its components as consequence of the leaching of the other one, as it was verified, for example, in the study carried out by Ortega-Zamora et al. [96]. That is why in this section both the HDESs and the quasi-hydrophobic DESs that have been used for the analysis of food samples, have been grouped and are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Application of hydrophobic or quasi-hydrophobic DESs in sample preparation procedures for food analysis.

In general, all the DESs included in the table have been synthesized following the same guidelines as for hydrophilic DESs: mixing the components while heating with constant stirring until a homogeneous mixture is obtained. In addition, although most HDESs used in food analysis are made up of two components, some ternary DESs have been designed, which show numerous advantages over traditional DESs, such as a lower viscosity and melting point, and even a better extraction efficiency in some cases [17,114]. It is the case of the work of Shishov and co-workers [103], in which different quaternary ammonium salts, carboxylic acids and medium chain fatty acids were studied as components of a DES. The best results were obtained with the DES formed by TBABr:malonic acid:hexanoic acid (1:1:1 molar ratio) and it was used in the sequential extraction of sulfonamides from chicken samples through a DLLME followed by HPLC-UV. First, an attempt was made to carry out the extraction using a DES formed by TBABr and hexanoic acid but, due to its high viscosity and lack of acidic media, a high mass-transfer from the solid phase did not occur. However, with the introduction of a third component, in this case a carboxylic acid, an increment in the extraction efficiency was observed due to the formation of hydrogen bonds between hexanoic acid and the analytes. The introduction of hexanoic acid not only has benefits during the extraction process, but also produces a decrease of DES viscosity, enabling its direct injection in the chromatographic system. Some HDESs have even been mixed with other materials, such as Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (m-NPs) to form a nanoferrofluid, which speeds up the sample preparation procedure and makes it more sustainable to perform the preconcentration of various analytes in complex food samples before their injection in different chromatographic systems [17,120]. For its preparation, the Fe3O4 m-NPs and the DES are separately synthesized and then mixed under constant stirring until a homogeneous fluid is obtained: the DES-based nanofluid [17,120]. As an example, Fan et al. [17] synthesized one of these nanofluids based on a ternary HDES composed of menthol, borneol and camphor in a 5:1:4 molar ratio. They used it for the extraction of 14 PAHs in 12 kinds of coffee samples after four different roasting conditions, which were separated and determined by HPLC-FD. LODs in the order of ng/L for all analytes and recovery values between 91.3 and 121%, showed the excellent performance of the methodology, which allowed verifying that the content of PAHs in the samples of coffee was modified depending on the temperature and time conditions of the roasting of its beans.

Currently, studies on the synthesis and application of HDESs for the extraction of a great variety of analytes from food matrices have expanded rapidly, which has led to an increase in the number of articles published in recent years. As can be seen in Table 2, several HDESs have been used for the extraction of both organic (phthalic acid esters [18,96,99], dyes [97,104,110,117], PAHs [17,85], sterols [98], pesticides [100,105,112,122,124,126,127], herbicides [102], insecticides [125], preservatives [101], pigments [86], antibiotics [87,103,108,114], fluorescent whitening agents [106], vitamins [107], mycotoxins [16], bisphenols [115], perfluoroalkyl substances [120] and terpenes [121]) and inorganic compounds (Co, Cd, Ni, As, V and Pb [109,111,113,116,118,119,123]) from aqueous phases (water [96,113,118,124], soft drinks [18,85,86,96,110], infusions [18,86,102,124], coffee [17], dairy products [86,99,108,111,114,126], fruit juices [16,86,87] and wine [116]). However, sauces [97,104], oils [97,100,120], egg yolk [97,125], jelly [110,117], honey [105] and solid food (meat [103], fish [106], flours [107], spices [121], dried fruits [112,119], vegetables [98,113,118,122,123] and fruits [101,115,118]) samples have also been analysed using HDESs. It is important to mention that, due to the complexity of some of the studied matrixes, different previous treatments have been needed in most cases. In this way, water [96,113,118,124], infusions [18,86,124], and soft drinks [18,85,86,96,110] were analysed without additional treatment or after degasification or filtration, while others such as honey [105] or fruit juices [16,86] were analysed after dilution with water and, in some cases, filtration. Likewise, procedures such as lyophilization or a previous extraction with an organic solvent (e.g., n-hexane, ACN, MeOH or acetone) were very useful in the treatment of egg yolk, olive oil, chili sauce, honey and some fruit juices, although it may be contradictory with the development of green sample preparation procedures using DESs. As a specific example, a hydrophilic DES has even been used in the treatment of oil samples to reduce the matrix effect [100]. In those cases, in which the matrix is more complex, more laborious procedures previous to the extraction of the compounds of interest are needed. For example, in the case of milk or yogurt, a deproteinization is usually carried out with ACN [114], although (NH4)2SO4 [108] has also been employed. When it comes to solid samples such as dried fruits, cereals, onion, parsley or even dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese, etc.), they are usually digested with H2O2:HNO3 (1:3, v/v) [109], although in some cases only HNO3 is used [119,123], before the application of microextraction techniques. However, if a previous step such as QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged and safe) [112], is carried out before the extraction technique in dried fruits for example, it would only be necessary to grind and homogenize them.

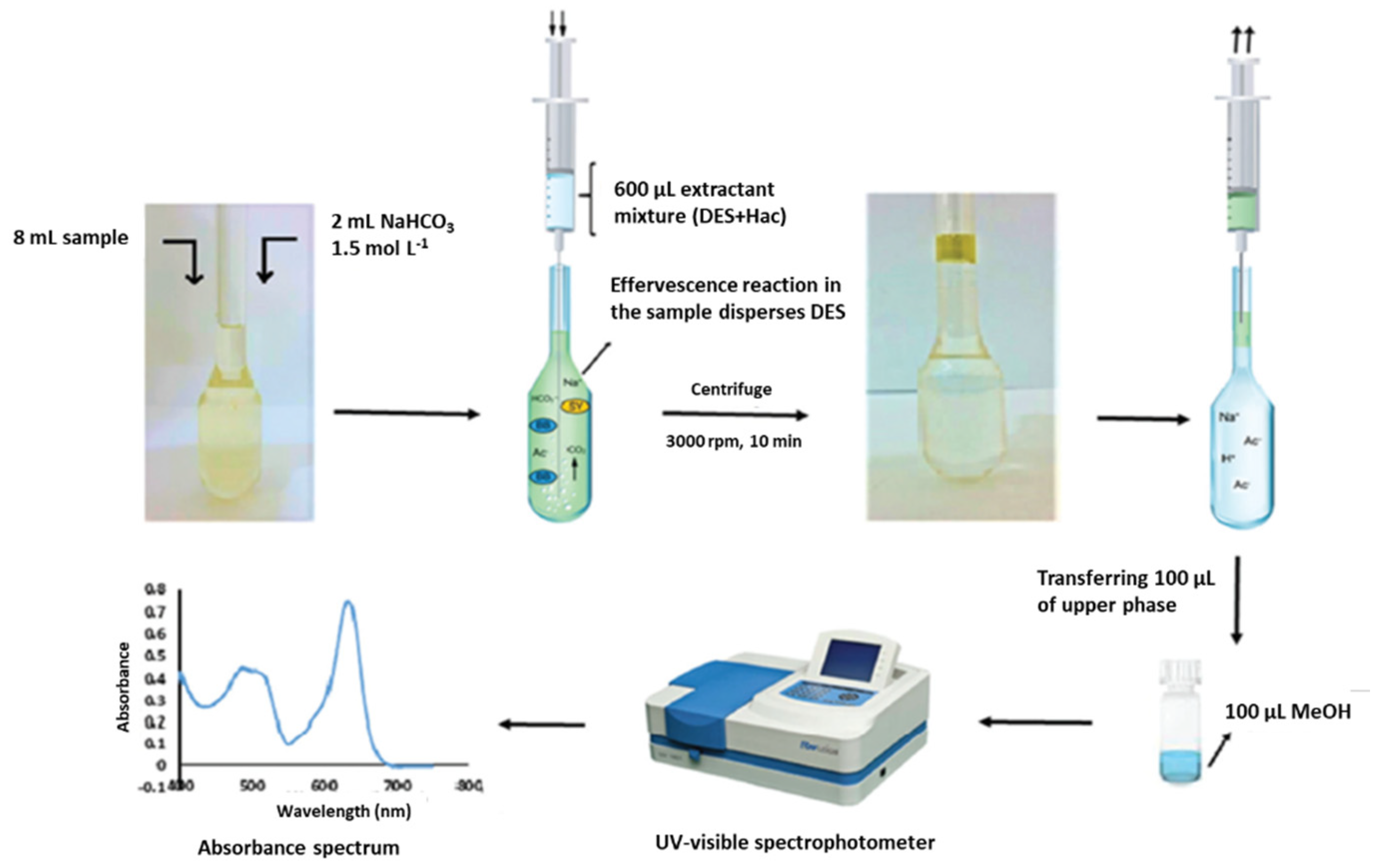

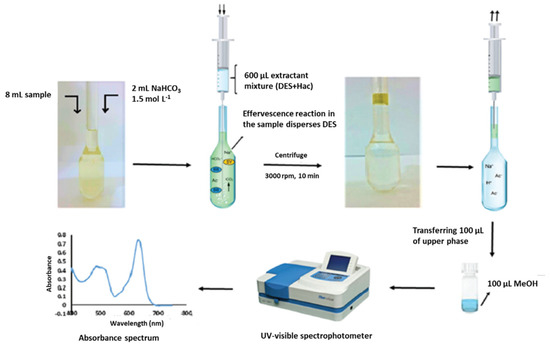

Nowadays, the above-mentioned low solubility of HDESs in aqueous samples has allowed their large application as extraction solvents in microextraction methods, complying with the principles of GAC. Among the different variants of the LPME, DLLME constitutes once more one of the preferred options for the application of HDES for the analysis of samples of diverse nature, including water [96], soft drinks [85,110], infusions [124], honey [105], dried fruits [119], flour [107], fruit juices [124] and egg yolk [125]. In this sense, it is important to highlight that in certain cases, no additional solvents have been necessary to obtain a good dispersion of the HDES into the sample [18,86,96,97,98,110]. Instead, the DLLME procedure has been assisted in different ways, including the vortex-assisted DLLME [86,97,99,100,104,106], ultrasound-assisted DLLME [16,85,87,101,113,116,123,124], air-assisted [109] and microwave-assisted DLLME [128]. However, other versions have also been used, such as DLLME based on the solidification of the floating organic drop (SFO) [18,115,122,126]; salting out-DLLME-back extraction or salt induced-homogenous liquid-liquid extraction-DLLME, in which a salt is added (e.g., NaCl, (NH4)2SO4, Na2SO4 or NH4Cl) to reduce the solubility of the analytes in water and to increase their distribution coefficients in the organic phase [108,114]; effervescence-assisted DLLME in which an effervescent reaction between a proton donor solvent (acetic acid, which has been previously mixed with HDES in a 3:1 (v/v) ratio) and an effervescent agent (sodium bicarbonate) is produced generating carbon dioxide that facilitates the dispersion of the extraction solvent (HDES, see Figure 2) [117]; or even the combination of DLLME with a previous extraction and clean-up stage, such as the QuEChERS method, in which the extracted supernatant was used as a dispersant in the following DLLME for further purification and preconcentration [112]. Another interesting modification of the LPME technique is the use of the above-mentioned ferrofluid as an extraction solvent [17,120].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of effervescence assisted dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction. Reprinted from Ravandi and Fat’hi [117] with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry.

On the other hand, in order to improve the sensitivity towards volatile compounds, headspace microextraction techniques have been used, such as headspace SDME, which is faster and cheaper than other extraction methods, and allows extracting a wide range of components with diverse physicochemical properties in matrices where no pre-treatment is necessary. As an example, Triaux et al. [121] used a HDES (tetrabutylammonium bromide (N4444Br):dodecanol, 1:2 molar ratio) as extracting solvent for the extraction of 67 terpenes from six spices (cumin, cinnamon, clove, fennel, nutmeg and thyme) used as bought without additional grinding. The DES was introduced into the needle of a GC microsyringe, which was inserted into the headspace of the vial where the sample was located. The DES was pushed to form a drop at the tip of the needle and was left for 90 min at 80 °C for the absorption of the volatile analytes on the DES drop. The extracts were analysed by GC-MS obtaining limits of quantification (LOQs) between 0.47 and 86.40 μg/g.

Regarding the final determination of the analytes, different separation and detection techniques have been applied, being LC, both HPLC [17,18,86,87,96,97,98,99,101,103,104,107,110,112,114,124,125] and UHPLC [115,120], the most extensively used, although some applications of micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography [108] and GC [85,100,102,105,121,122,126,127] can also be found mainly for non-ionic HDESs, which are characterized by a higher volatility. These separation techniques have been coupled to different detection systems, including UV [18,87,96,97,99,103,107,110,112,124,125], DAD [86,104,114], variable wavelength detectors [98], FD [17,101], MS [102,120,121,122], MS/MS [85,115], FID [105,126,127] and ECD [100]. Other techniques have also been directly applied without a previous separation of the analytes, such as UV-Vis spectroscopy [16,117], fluorescence spectrometry [106] and AAS [109,111,113,116,118,119,123]. The combination of these techniques with the outstanding extraction performances shown by the synthesized HDESs has provided excellent sensitivity in all cases, with LODs in the low ppb level.

As with hydrophilic DESs, hydrophobic NADESs can also be synthesized from natural compounds immiscible with water. As mentioned above, apart from all the inherent advantages of HDESs, they fully represent the GAC principles, since they are easily prepared, cost-effective and are not harmful to the environment [129]. In addition, as a result of their diverse compositions (among the components most used as HBA, menthol, thymol and camphor stand out, while carboxylic acids are usually used as HBDs), they have a wide range of polarity and physical properties [8]. Hydrophobic NADESs have also been used in food analysis, although they are still not very abundant compared to the use of “non-natural HDESs”, as shown in Table 2. It is worth highlighting the work of Soltani and co-workers [100], who synthesized a hydrophobic NADES composed of thymol and vanillin (1:1, molar ratio in which a transparent yellow liquid remained). They calculated its solubility in water (0.005%, w/v) and its octanol/water distribution constant (log KOW = 4.30) to verify its hydrophobicity. Furthermore, they found that the thymol:vanillin (1:1) DES was stable for at least one week at ambient conditions. The authors used it as an extraction solvent in VA-LLME coupled with GC-μECD for the determination of 16 pesticides in olive oil samples (extra virgin, virgin and refined olive oils), complex food samples that showed a high matrix effect. Therefore, the authors developed a DES-based liquid–liquid solvent system (n-hexane/ACN/DES) to achieve cleaning the sample as much as possible and, thus, improve sensitivity and reduce the matrix effect. To do this, they mixed the sample with n-hexane, and then with ACN (used as extraction solvent) and a hydrophilic NADES composed of ChCl and urea. After shaking and centrifuging, a triphasic system was observed in which the medium layer was the ACN that contained the pesticide residues and was used for performing the preconcentration procedure worked up. The develop method provided high recovery percentages for the analytes (between 63.1–119.4%) with high precision (relative standard deviation values in the range 2–7%), and it was also simple and sensitive with LODs in the range 0.01–0.08 μg/kg.

4. Conclusions

Considering the current trends in the Analytical Chemistry field, DESs constitute a very interesting alternative to conventional solvents, not only because of their interesting physicochemical properties, but because they have made it possible to develop more sustainable analytical procedures, from an environmental point of view due to their low toxicity, and also from an economic point of view due to their general low cost and the simplicity of their synthesis. As with other solvents widely used in sample preparation techniques, the wide variety of HBD and HBA available make it possible to configure a large number of DESs, which has allowed their application for the extraction of a large number of organic and inorganic analytes from diverse food matrices. In this sense, the hydrophilic or hydrophobic nature of DES plays a fundamental role since it has a great influence on the extractive process. However, few studies have evaluated this aspect, as well as their toxicity. In fact, the greenness of many DESs currently used as green solvents has not been fully even evaluated, and many of them actually continue to present significant toxicity or pose a risk to the environment, in many cases due to synthesis procedures that use conventional solvents. In this context, the introduction of NADESs opens a window of hope for reducing the impact of this type of solvent on the environment.

It is also important to mention that, even with their previously mentioned great properties, there are still some aspects that limit the application of DESs to the analysis of food samples from an operational point of view, such as the miscibility of the hydrophilic ones with aqueous samples or the need of including organic solvents to provide a good dispersion of the DESs or to decrease their viscosity, which goes against the principles of developing sustainable analytical methodologies. Besides, the limited number of cheap, readily available and biodegradable components (especially in the case of hydrophobic NADESs) for the synthesis of HDESs also pose a limitation for their use in food analysis.

Despite the aforementioned problems that the use of DESs still poses today, this type of new solvents still has a wide margin for improvement and are proposed as an alternative for the future to be taken into account, not only at an analytical level, but also in a wide range of applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; methodology, C.O.-Z. and J.G.-S.; formal analysis, C.O.-Z., J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; investigation, C.O.-Z., J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; resources, J.H.-B.; data curation; writing—original draft preparation, C.O.-Z., J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; writing—review and editing, C.O.-Z., J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; visualization, J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; supervision, J.G.-S. and J.H.-B.; project administration J.H.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Spanish Ministry of Science (project AGL2017-89257-P).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

C.O.-Z. thanks the Canary Agency of Economy, Industry, Trade and Knowledge (ACIISI, Spain) of the Government of the Canary Islands for the FPI fellowship (85% co-financed from European Social Fund). J.G.-S. would like to thank the Canary Agency of Economy, Industry, Trade and Knowledge (ACIISI, Spain) of the Government of the Canary Islands for the contract of the “Catalina Ruiz” Program (85% co-financed from European Social Fund). This article is based upon work from the Sample Preparation Task Force and Network, supported by the Division of Analytical Chemistry of the European Chemical Society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tang, W.; An, Y.; Row, K.H. Emerging applications of (micro) extraction phase from hydrophilic to hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents: Opportunities and trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 136, 116187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, Z.; Namieśnik, J. The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 50, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Loussala, H.M.; Han, S.; Ji, X.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Recent advances of ionic liquids in sample preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 125, 115833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Pino, V. Green solvents in analytical chemistry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 18, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasek, E.; Bernardi, G.; Morelli, D.; Merib, J. Sustainable green solvents for microextraction techniques: Recent developments and applications. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1640, 461944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishov, A.; Pochivalov, A.; Nugbienyo, L.; Andruch, V.; Bulatov, A. Deep eutectic solvents are not only effective extractants. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 129, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 1, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández, M.d.l.Á.; Boiteux, J.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Silva, M.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents-mediated extractions: The way forward for sustainable analytical developments. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1038, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saha, S.K.; Dey, S.; Chakraborty, R. Effect of choline chloride-oxalic acid based deep eutectic solvent on the ultrasonic assisted extraction of polyphenols from Aegle marmelos. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 287, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, E.; Ghanemi, K.; Fallah-Mehrjardi, M.; Dadolahi-Sohrab, A. A novel digestion method based on a choline chloride–oxalic acid deep eutectic solvent for determining Cu, Fe, and Zn in fish samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 762, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunay, N.; Elik, A.; Gürkan, R. Innovative and practical deep eutectic solvent based vortex assisted microextraction procedure for separation and preconcentration of low levels of arsenic and antimony from sample matrix prior to analysis by hydride generation-atomic absorption spectrometry. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Dadfarnia, S.; Shabani, A.M.H.; Tamaddon, F.; Azadi, D. Deep eutectic liquid organic salt as a new solvent for liquid-phase microextraction and its application in ligandless extraction and preconcentration of lead and cadmium in edible oils. Talanta 2015, 144, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunay, N.; Elik, A.; Gürkan, R. Natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted-microextraction for extraction, pre-concentration and analysis of methylmercury and total mercury in fish and environmental waters by spectrophotometry. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2019, 36, 1079–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Feng, F.; Chen, Z.-G.; Wu, T.; Wang, Z.-H. Green and efficient removal of cadmium from rice flour using natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunay, N.; Elik, A.; Gürkan, R. A novel, green and safe ultrasound-assisted emulsification liquid phase microextraction based on alcohol-based deep eutectic solvent for determination of patulin in fruit juices by spectrophotometry. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 82, 103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Cao, X.; Han, T.; Pei, H.; Hu, G.; Wang, W.; Qian, C. Selective microextraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using a hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent composed with an iron oxide-based nanoferrofluid. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Zamora, C.; Jiménez-Skrzypek, G.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Borges, J. Extraction of phthalic acid esters from soft drinks and infusions by dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction based on the solidification of the floating organic drop using a menthol-based natural deep eutectic solvent. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1646, 462132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jung, D.; Park, K. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of organic and inorganic analytes from aqueous environments. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; McAlpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.-N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents: Properties, applications, and perspectives. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajkacz, S.; Rusin, K.; Wolny, A.; Adamek, J.; Erfurt, K.; Chrobok, A. Highly efficient extraction procedures based on natural deep eutectic solvents or ionic liquids for determination of 20-hydroxyecdysone in spinach. Molecules 2020, 25, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunay, N.; Elik, A.; Gürkan, R. Preparation and application of alcohol based deep eutectic solvents for extraction of curcumin in food samples prior to its spectrophotometric determination. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorouraddin, S.M.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Okhravi, T. Application of deep eutectic solvent as a disperser in reversed-phase dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction for the extraction of Cd(II) and Zn(II) ions from oil samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 93, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; D’Amato, R.; Trabalza-Marinucci, M.; Regni, L.; Proetti, P.; Maratta, A.; Cerutti, S.; Pacheco, P. Green and simple extraction of free seleno-amino acids from powdered and lyophilized milk samples with natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2020, 326, 126965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doldolova, K.; Bener, M.; Lalikoğlu, M.; Aşçı, Y.S.; Arat, R.; Apak, R. Optimization and modeling of microwave-assisted extraction of curcumin and antioxidant compounds from turmeric by using natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2021, 353, 129337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounr, R.A.; Tuzen, M.; Khuhawar, M.Y. Determination of selenium and arsenic ions in edible mushroom samples by novel chloride–oxalic acid deep eutectic solvent extraction using graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectrometry. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panhwar, A.H.; Tuzen, M.; Kazi, T.G. Choline chloride-oxalic acid as a deep eutectic solvent-based innovative digestion method for the determination of selenium and arsenic in fish samples. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağda, E.; Altundağ, H.; Soylak, M. Highly simple deep eutectic solvent extraction of manganese in vegetable samples prior to its ICP-OES analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 179, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajkacz, S.; Adamek, J. Development of a method based on natural deep eutectic solvents for extraction of flavonoids from food samples. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Feng, F.; Jiang, J.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, T.; Voglmeir, J.; Chen, Z.-G. Green and efficient extraction of rutin from tartary buckwheat hull by using natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Ping-Kou; Jiang, Y.-W.; Wang, L.-T.; Niu, L.-J.; Liu, Z.-M.; Fu, Y.-J. Natural deep eutectic solvents couple with integrative extraction technique as an effective approach for mulberry anthocyanin extraction. Food Chem. 2019, 296, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajkacz, S.; Adamek, J. Evaluation of new natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of isoflavones from soy products. Talanta 2017, 168, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradanas-González, F.; Álvarez-Rivera, G.; Benito-Peña, E.; Navarro-Villoslada, F.; Cifuentes, A.; Herrero, M.; Moreno-Bondi, M.C. Mycotoxin extraction from edible insects with natural deep eutectic solvents: A green alternative to conventional methods. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1648, 462180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan Türker, D.; Doğan, M. Application of deep eutectic solvents as a green and biodegradable media for extraction of anthocyanin from black carrots. LWT 2021, 138, 110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradiso, V.M.; Squeo, G.; Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C. An easy and green tool for olive oils labelling according to the contents of hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol derivatives: Extraction with a natural deep eutectic solvent and direct spectrophotometric analysis. Food Chem. 2019, 291, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Lian, J.; Liang, N.; Zhao, L. Development of extraction separation technology based on deep eutectic solvent and magnetic nanoparticles for determination of three sex hormones in milk. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1166, 122558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piemontese, L.; Perna, F.M.; Logrieco, A.; Capriati, V.; Solfrizzo, M. Deep eutectic solvents as novel and effective extraction media for quantitative determination of ochratoxin A in wheat and derived products. Molecules 2017, 22, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elik, A.; Unal, Y.; Altunay, N. Development of a chemometric-assisted deep eutectic solvent-based microextraction procedure for extraction of caffeine in foods and beverages. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2019, 36, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhou, T.; Wan, H.; Han, Q.; Ma, Y.; Tan, T.; Wan, Y. One-step deep eutectic solvent strategy for efficient analysis of aflatoxins in edible oils. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4840–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunay, N.; Unal, Y.; Elik, A. Towards green analysis of curcumin from tea, honey and spices: Extraction by deep eutectic solvent assisted emulsification liquid-liquid microextraction method based on response surface design. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2020, 37, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhu, T.; Row, K.H. Deep eutectic solvents for the purification of chloromycetin and thiamphenicol from milk. J. Sep. Sci. 2017, 40, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zounr, R.A.; Tuzen, M.; Khuhawar, M.Y. A simple and green deep eutectic solvent based air assisted liquid phase microextraction for separation, preconcentration and determination of lead in water and food samples by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 259, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaesa, A.G.; Fernandes, J.O.; Sanz, M.T.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Cunha, S.C. Green determination of brominated flame retardants and organochloride pollutants in fish oils by vortex assisted liquid-liquid microextraction and gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2019, 195, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, H.; Ghanbari-Rad, S.; Habibi, E. Optimization deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted liquid-liquid microextraction by using the desirability function approach for extraction and preconcentration of organophosphorus pesticides from fruit juice samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 87, 103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, F.; Yilmaz, E.; Soylak, M. Vortex assisted deep eutectic solvent (DES)-emulsification liquid-liquid microextraction of trace curcumin in food and herbal tea samples. Food Chem. 2018, 243, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounr, R.A.; Tuzen, M.; Deligonul, N.; Khuhawar, M.Y. A highly selective and sensitive ultrasonic assisted dispersive liquid phase microextraction based on deep eutectic solvent for determination of cadmium in food and water samples prior to electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, H.U.; Balal, M.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Hussain, Z.; Safi, F.; Ullah, S.; Boczkaj, G. Deep eutectic solvents based assay for extraction and determination of zinc in fish and eel samples using FAAS. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 333, 115930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borahan, T.; Unutkan, T.; Turan, N.B.; Turak, F.; Bakırdere, S. Determination of lead in milk samples using vortex assisted deep eutectic solvent based liquid phase microextraction-slotted quartz tube-flame atomic absorption spectrometry system. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, Z.; Unutkan, T.; Erulaş, F.; Bakırdere, E.G.; Bakırdere, S. A green, accurate and sensitive analytical method based on vortex assisted deep eutectic solvent-liquid phase microextraction for the determination of cobalt by slotted quartz tube flame atomic absorption spectrometry. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounr, R.A.; Tuzen, M.; Khuhawar, M.Y. Ultrasound assisted deep eutectic solvent based on dispersive liquid liquid microextraction of arsenic speciation in water and environmental samples by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 242, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhwar, A.H.; Tuzen, M.; Kazi, T.G. Deep eutectic solvent based advance microextraction method for determination of aluminum in water and food samples: Multivariate study. Talanta 2018, 178, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivrikaya, S. A deep eutectic solvent based liquid phase microextraction for the determination of caffeine in Turkish coffee samples by HPLC-UV. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2020, 37, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Shahedi Hojghan, A.; Afshar Mogaddam, M.R. Development of a new temperature-controlled liquid phase microextraction using deep eutectic solvent for extraction and preconcentration of diazinon, metalaxyl, bromopropylate, oxadiazon, and fenazaquin pesticides from fruit juice and vegetable samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 66, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereshti, H.; Jamshidi, F.; Nouri, N.; Nodeh, H.R. Hyphenated dispersive solid- and liquid-phase microextraction technique based on a hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent: Application for trace analysis of pesticides in fruit juices. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Sattari Dabbagh, M.; Yadeghari, A. Deep eutectic solvent based gas-assisted dispersive liquid-phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography and flame ionization detection for the determination of some pesticide residues in fruit and vegetable samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2017, 40, 2253–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Afshar Mogaddam, M.R.; Aghanassab, M. Deep eutectic solvent-based dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 2576–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazmandegan-Shamili, A.; Dadfarnia, S.; Shabani, A.M.H.; Moghadam, M.R.; Saeidi, M. Temperature-controlled liquid–liquid microextraction combined with high-performance liquid chromatography for the simultaneous determination of diazinon and fenitrothion in water and fruit juice samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, J.; Li, B.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Liu, K.; Li, C. Deep eutectic solvent-based extraction coupled with green two-dimensional HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS for the determination of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. fruit. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Deng, Z.; Xiao, Y. Hexafluoroisopropanol-based hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction of pyrethroids in tea beverages and fruit juices. Food Chem. 2019, 274, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishov, A.; Gagarionova, S.; Bulatov, A. Deep eutectic mixture membrane-based microextraction: HPLC-FLD determination of phenols in smoked food samples. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Rajabi, M.; Barfi, B.; Sajjadi, S.M. Deep eutectic-based vortex-assisted/ultrasound-assisted liquid-phase microextractions of chromium species. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2020, 17, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhwar, A.H.; Tuzen, M.; Kazi, T.G. Ultrasonic assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction method based on deep eutectic solvent for speciation, preconcentration and determination of selenium species (IV) and (VI) in water and food samples. Talanta 2017, 175, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, R.; Kazi, T.G.; Afridi, H.I.; Talpur, F.N.; Akhtar, A.; Baig, J.A. Deep-eutectic-solvent-based dispersive and emulsification liquid–liquid microextraction methods for the speciation of selenium in water and determining its total content levels in milk formula and cereals. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 5186–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Rajabi, M.; Barfi, B.; Sajjadi, S.M. Efficacious and environmentally friendly deep eutectic solvent-based liquid-phase microextraction for speciation of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) ions in food and water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Huang, A.; Zheng, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Hu, H.; Xiao, Y. A density-tunable liquid-phase microextraction system based on deep eutectic solvents for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tea, medicinal herbs and liquid foods. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiri, E.; Khandaghi, J.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Afshar Mogaddam, M.R. Combination of dispersive solid phase extraction with solidification organic drop–dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction based on deep eutectic solvent for extraction of organophosphorous pesticides from edible oil samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1627, 461390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zheng, S.; Qin, F.; Zhao, L. Analysis of six preservatives in beverages using hydrophilic deep eutectic solvent as disperser in dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction based on the solidification of floating organic droplet. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 195, 113889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolhosseini, M.; Shemirani, F.; Yousefi, S.M. Poly (deep eutectic solvents) as a new class of sustainable sorbents for solid phase extraction: Application for preconcentration of Pb (II) from food and water samples. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svigelj, R.; Bortolomeazzi, R.; Dossi, N.; Giacomino, A.; Bontempelli, G.; Toniolo, R. An effective gluten extraction method exploiting pure choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents (ChCl-DESs). Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 4079–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezeli, T.; Daneshfar, A.; Sahraei, R. A green ultrasonic-assisted liquid–liquid microextraction based on deep eutectic solvent for the HPLC-UV determination of ferulic, caffeic and cinnamic acid from olive, almond, sesame and cinnamon oil. Talanta 2016, 150, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, M.; Habibollahi, S.; Akbari, A. Centrifuge-less deep eutectic solvent based magnetic nanofluid-linked air-agitated liquid–liquid microextraction coupled with electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry for simultaneous determination of cadmium, lead, copper, and arsenic in food sample. Food Chem. 2019, 281, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani, A.; Afshar Mogaddam, M.R.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Mohebbi, A.; Nemati, M.; Torbati, M. A three-phase solvent extraction system combined with deep eutectic solvent-based dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction for extraction of some organochlorine pesticides in cocoa samples prior to gas chromatography with electron capture detection. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 3674–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Li, Z.; Mao, X.; Wan, Y.; Qiu, H. Deep eutectic solvent-based liquid-phase microextraction for detection of plant growth regulators in edible vegetable oils. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 3511–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenutti, L.; del Pilar Sanchez-Camargo, A.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Ferreira, S.R.S. NADES as potential solvents for anthocyanin and pectin extraction from Myrciaria cauliflora fruit by-product: In silico and experimental approaches for solvent selection. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 315, 113761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Fuad, F.; Mohd Nadzir, M.; Harun@Kamaruddin, A. Hydrophilic natural deep eutectic solvent: A review on physicochemical properties and extractability of bioactive compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 339, 116923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.V.; Tadini, C.C.; Biswas, A.; Buttrum, M.; Kim, S.; Boddu, V.M.; Cheng, H.N. Microwave-assisted extraction of soluble sugars from banana puree with natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES). LWT 2019, 107, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanioti, S.; Tzia, C. Extraction of phenolic compounds from olive pomace by using natural deep eutectic solvents and innovative extraction techniques. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 48, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, H.S.; Khoshsima, A.; Pazuki, G. Choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents as green extractant for the efficient extraction of 1-butanol or 2-butanol from azeotropic n-heptane + butanol mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 313, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Flammia, V.; Carvalho, T.; Viciosa, M.T.; Dionísio, M.; Barreiros, S.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A. Properties and thermal behavior of natural deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 215, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, Z.M.; Konieczka, P.; Namieśnik, J. Analytical Eco-Scale for assessing the greenness of analytical procedures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; Gropp, J.; et al. Safety and efficacy of L-arginine produced by fermentation with Escherichia coli NITE BP-02186 for all animal species. EFSA J. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Dusemund, B.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Leblanc, J.; et al. Re-evaluation of glycerol (E 422) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, B.-Y.; Xu, P.; Yang, F.-X.; Wu, H.; Zong, M.-H.; Lou, W.-Y. Biocompatible deep eutectic solvents based on choline chloride: Characterization and application to the extraction of rutin from sophora japonica. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 2746–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Osch, D.J.G.P.; Zubeir, L.F.; van den Bruinhorst, A.; Rocha, M.A.A.; Kroon, M.C. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents as water-immiscible extractants. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4518–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caldeirão, L.; Fernandes, J.O.; Gonzalez, M.H.; Godoy, H.T.; Cunha, S.C. A novel dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction using a low density deep eutectic solvent-gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soft drinks. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1635, 461736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Jia, H.; Zhang, H. Liquid–liquid microextraction of synthetic pigments in beverages using a hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent. Food Chem. 2018, 243, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L. Eco-friendly ultrasonic assisted liquid–liquid microextraction method based on hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent for the determination of sulfonamides in fruit juices. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1609, 460520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcon, D.P.; Franco, F.C. All-fatty acid hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents towards a simple and efficient microextraction method of toxic industrial dyes. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 318, 114220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoś, P.; Słupek, E.; Gębicki, J. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents in microextraction techniques–A review. Microchem. J. 2020, 152, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal-Abidin, M.H.; Hayyan, M.; Wong, W.F. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents: Current progress and future directions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 97, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Su, E. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents: The new generation of green solvents for diversified and colorful applications in green chemistry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Branco, L.C.; Marrucho, I.M. Quest for green-solvent design: From hydrophilic to hydrophobic (deep) eutectic solvents. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, M.; McCourt, É.N.; Connolly, F.; Nockemann, P.; Swadźba-Kwaśny, M.; Holbrey, J.D. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents incorporating trioctylphosphine oxide: Advanced liquid extractants. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 17323–17332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, R.J.; Saramago, B.; Marrucho, I.M. Surface tension of DL-menthol:octanoic acid eutectic mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 4915–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Branco, L.C.; Marrucho, I.M. Development of hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for extraction of pesticides from aqueous environments. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2017, 448, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Zamora, C.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; Hernández-Borges, J. Menthol-based deep eutectic solvent dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction: A simple, quick and green approach for the analysis of phthalic acid esters from water and beverage samples. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8783–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zong, B.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Yu, J. A highly efficient vortex-assisted liquid–liquid microextraction based on natural deep eutectic solvent for the determination of Sudan I in food samples. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 17432–17439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khare, L.; Karve, T.; Jain, R.; Dandekar, P. Menthol based hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent for extraction and purification of ergosterol using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Shi, L.; Yang, D.; Yang, Y. Novel low viscous hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents liquid-liquid microextraction combined with acid base induction for the determination of phthalate esters in the packed milk samples. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Sereshti, H.; Nouri, N. Deep eutectic solvent-based clean-up/vortex-assisted emulsification liquid-liquid microextraction: Application for multi-residue analysis of 16 pesticides in olive oils. Talanta 2021, 225, 121983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Jin, X.; Wei, H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasonic-assisted liquid-liquid micro-extraction combined with HPLC-FLD for diphenylamine determination in fruit. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2021, 38, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torbati, M.; Farajzadeh, M.A.; Mogaddam, M.R.A.; Torbati, M. Deep eutectic solvent based homogeneous liquid–liquid extraction coupled with in-syringe dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction performed in narrow tube; application in extraction and preconcentration of some herbicides from tea. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 42, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishov, A.; Gorbunov, A.; Baranovskii, E.; Bulatov, A. Microextraction of sulfonamides from chicken meat samples in three-component deep eutectic solvent. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Shan, Z.; Pang, T.; Lu, X.; Wang, B. Preparation of new hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents and their application in dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction of Sudan dyes from food samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 3873–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Abbaspour, M.; Kazemian, R. Synthesis of a green high density deep eutectic solvent and its application in microextraction of seven widely used pesticides from honey. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1603, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Shang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, K.; Fan, J. Effective extraction of fluorescent brightener 52 from foods by in situ formation of hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M.; Mahmoodi-Maymand, M.; Dastmalchi, F. Green, fast and simple dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction method by using hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent for analysis of folic acid in fortified flour samples before liquid chromatography determination. Food Chem. 2020, 320, 126486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Yue, M.-E.; Xu, J.; Jiang, T.-F. Determination of fluoroquinolones in milk, honey and water samples by salting out-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction based on deep eutectic solvent combined with MECC. Food Chem. 2020, 332, 127371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elik, A.; Bingöl, D.; Altunay, N. Ionic hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents in developing air-assisted liquid-phase microextraction based on experimental design: Application to flame atomic absorption spectrometry determination of cobalt in liquid and solid samples. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M. Determination of some red dyes in food samples using a hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent-based vortex assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1591, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıtak, D.; Sabancı, D. Response surface methodology and hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent based liquid phase microextraction combination for determination of cadmium in food and water samples. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]