Abstract

A novel human coronavirus prompted considerable worry at the end of the year 2019. Now, it represents a significant global health and economic burden. The newly emerged coronavirus disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the primary reason for the COVID-19 global pandemic. According to recent global figures, COVID-19 has caused approximately 243.3 million illnesses and 4.9 million deaths. Several human cell receptors are involved in the virus identification of the host cells and entering them. Hence, understanding how the virus binds to host-cell receptors is crucial for developing antiviral treatments and vaccines. The current work aimed to determine the multiple host-cell receptors that bind with SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses for the purpose of cell entry. Extensive research is needed using neutralizing antibodies, natural chemicals, and therapeutic peptides to target those host-cell receptors in extremely susceptible individuals. More research is needed to map SARS-CoV-2 cell entry pathways in order to identify potential viral inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Human coronaviruses (CoVs) are a new type of virus (order Nidovirales) identified in the mid-1960s and classified taxonomically under Coronaviridae family and Coronavirinae subfamily [1,2]. Coronaviruses are given this name for the crown-like spikes on their surface and are classified, based on their genetics, into four main groups known as alpha, beta, gamma, and delta coronaviruses. The majority of gamma coronaviruses and delta coronaviruses affect birds, whereas alpha coronaviruses and beta coronaviruses infect rodents and bats [3]. There are seven known coronavirus strains that can infect humans: 229E and NL63—alpha coronaviruses; OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and the newly identified SARS-CoV-2—beta coronaviruses [4]. Sometimes coronaviruses that infect animals can also make people sick and turn into human coronaviruses, as in cases with SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and the new SARS-CoV-2 [5,6]. The infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) was the first CoV discovered, and it primarily infected the respiratory systems of chickens. On the other hand, the first two human coronaviruses identified were HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, which cause common cold symptoms in people [7,8].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which is a viral respiratory disease caused by a SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV), was first identified in 2003 during an outbreak that emerged in China and then spread to more than 30 countries, resulting in a fatality rate of nearly 10% (774 deaths out of 9098 cases), turning the world’s attention to human coronaviruses [9,10,11]. Since then, several other HCoVs were identified; nearly 30 strains were found. The first HCoV strain identified was B814 that was isolated in 1965 [12]. In the post-SARS era, several other HCoVs strains appeared, including HCoV-NL63 in 2004, HCoV-HKU1 in 2005, and 229E and OC43 between 2003 and 2005 [13], which caused mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illness in humans, resulting in approximately 15–30% of common cold cases [8]. Later in 2012, another human coronavirus with a higher fatality rate (35%) invaded the Middle East and spread to other countries, which was then named the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [14,15,16,17]. Recently, at the end of December 2019, specifically in Wuhan, China, a new coronavirus was discovered in a number of patients suffering from severe pneumonia, resulting in a new disease called coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), which turned out to be a new type of human coronaviruses and was given the name SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [18,19,20,21].

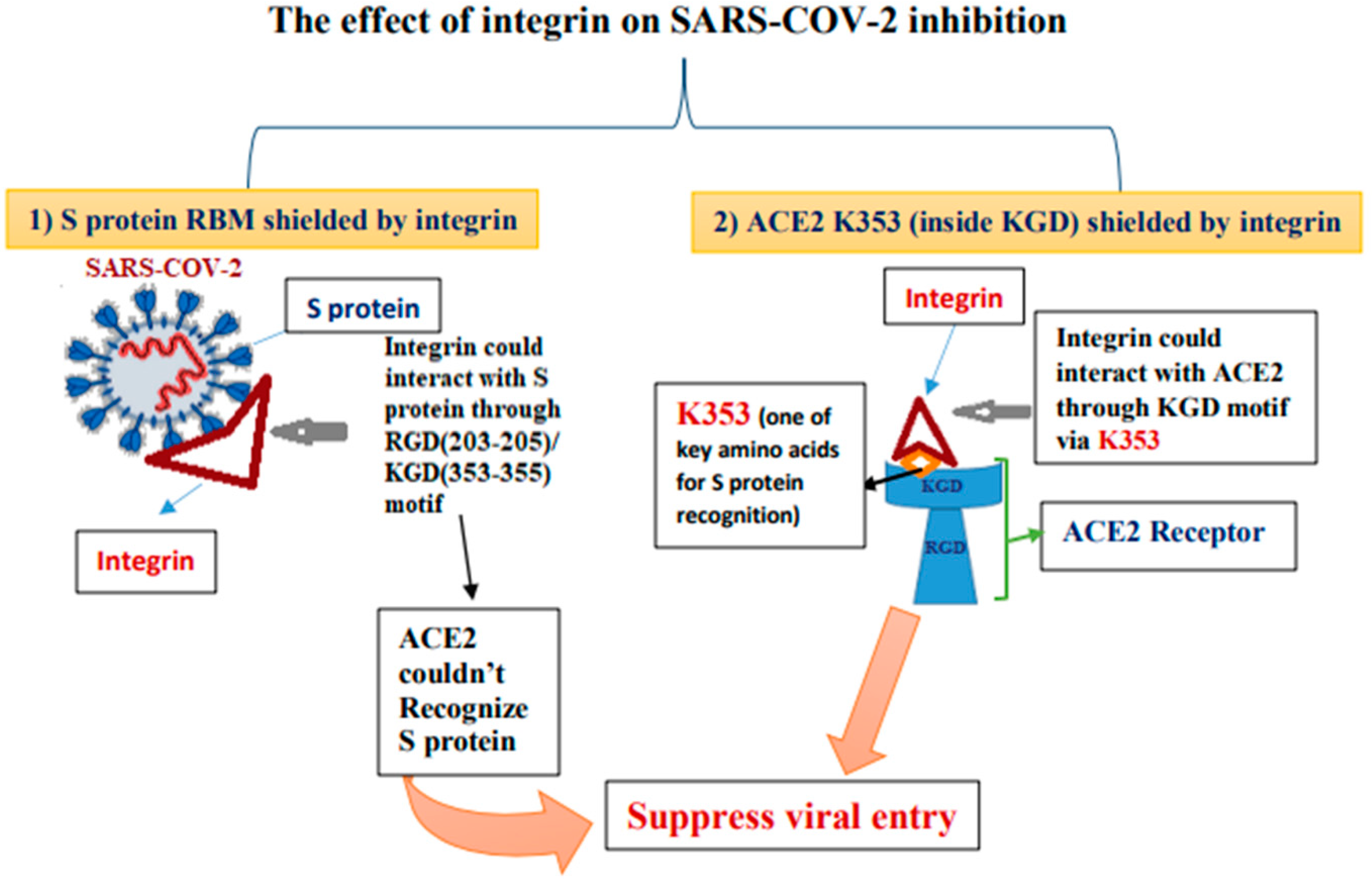

Different host-cell receptors are utilized by viral proteins to recognize host cells, such as integrins, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), sialic acid receptors, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), and glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78). The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the various human coronaviruses strains that have been identified, and to highlight the multiple human host-cell receptors used by viruses to enter cells. It is important to understand how this group of viruses can recognize and enter human cells. This may help to prevent future epidemics and pandemics caused by novel human coronaviruses.

5. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptors and Potential Therapeutic Targets

5.1. TLR1/2/6 in Proinflammatory Responses

The TLR2 receptor, which recognizes bacterial lipopeptides (LP), collaborates to form functional heterodimers with either TLR1 or TLR6 to mediate intracellular signaling [157,171,172]. TLR2 is regulated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and predominantly detects invasive Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi [173,174,175,176]. TLR2 heterodimers with either TLR1 or TLR6 enhanced proinflammatory responses during viral infection by identifying viral glycoproteins [177,178]. This implies a limited function for antiviral immunity [179]. The immunopathological functions played by TLR1 and TLR6 during SARS-CoV-2 infection remain to be clarified [178]. However, increased levels of TLR2 with either TLR1 or TLR6 DAMPs, including beta-defensin-3, named TLR1/2, and the high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1), named TLR1/2/6, were recorded in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and serum obtained from COVID-19 patients [180,181,182]. The direct binding between DAMPs and the corresponding TLRs can trigger TLR-mediated inflammatory reactions, analogous to that induced by PAMP recognition [164]. Consequently, TLR1/2/6 activation and its consequent signal transduction may play a role in explaining the immunopathological symptoms observed by COVID-19 patients in clinical settings.

5.2. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and TLR3 Role in Antiviral Immunity

TLR3 is required for antiviral immunity because it recognizes and communicates with viral PAMPs, such as double-stranded ribonucleic acid (dsRNA) generated by positive sense-strand RNA and DNA viruses during viral replication [150,183], small interference RNA [151], and inadequate stem structures in single-stranded RNA [184]. Liberated cellular debris, besides the cytoplasmic nucleotides (messenger RNA and dsRNA) and GRP78, activates TLR3 DAMPs from host cells [151,185,186]. TLR3 is unique in that it is the only TLR that interacts solely with TRIF, activating both NF-κβ and interferon-regulatory factor-3 and 7 [150]. This interaction causes pro-inflammatory molecules to be released, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, found in the immunopathological screening of COVID-19 patients [112,187]. Direct communication between TLR3 and the SARS-CoV-2 S protein has yet to be explained. TLR3 may recognize SARS-CoV-2 products released during viral replication, indicating that TLR3 may be a therapeutic target that, when activated, may increase antiviral immune responses, decrease viral loads, and promote SARS-CoV-2 blockage [188].

5.3. TLR4 Inhibition and SARS-CoV-2 Entry

TLR4 recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of bacteria and its activation generally results in the production of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines [189]. Due to the physiological characterization of LPS, the TLR4 receptor is responsible for Gram-negative bacterial immunity [188,190]. TLR4 activation and interaction with viral fusion proteins and glycoproteins, such as those seen in respiratory viruses, have been described [191,192]. TLR4 can react to a variety of DAMPs originating from the host, which have been linked to increased and uncontrolled inflammation in autoimmune illnesses and chronic inflammatory disorders [193,194]. TLR4-mediated inflammation that is unregulated has been associated with immunopathological effects in COVID-19 patients [194]. In computational studies investigating the TLR-binding efficacy of S protein have demonstrated that TRL4 has the highest affinity for the S1 domain of the S protein [195]. As TLR4’s ability to suppress pathogens could constitute a novel viral entry route for SARS-CoV-2, TLR4 inhibition as a potential treatment in COVID-19 infection should be examined.

5.4. TLR5 as a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Target

During vaccine development and to enhance the vaccine efficacy by tailoring the immune responses, a potent immunomodulatory agent called flagellin, which is a structural whip-like filament dependent on microtubules, has been used as an adjuvant component [196,197] due to its ability to influence pathogenic virulence to enable locomotion in motile Gram-negative and positive bacteria [165,198]. The interaction of flagellin with TLR5 leads to subsequent NF-kβ motivated inflammation through enrolment of MyD88 and has been shown to be an effective immunomodulatory agent [157,158,199,200,201]. The use of flagellin to target TLR5 in the creation of vaccines against viral infections has been studied. However, the interaction of TLR5 with SARS-CoV-2 needs to be investigated. In silico studies showed positive energy for TLR5 and S protein of SARS-CoV-2, indicating a possible association [195].

5.5. TLR7 and TLR8 Role in SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Toll-like receptors 7/8 (TLR7/8) are pattern recognition receptors (PRR) located on intracellular organelles that produce antiviral immunity by recognizing the viral single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and releasing cytokines, chemokines, IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-λ as pro-inflammatory mechanisms [202,203]. Studies have demonstrated TLR7/8′s role in reducing viral replication in HIV-1 [204], influenza [195], and MERS-CoV [205]. When viral ssRNA binds to TLR7/8 upon viral entry, antiviral immunity is activated. The SARS-CoV-2 genome has shown more ssRNA segments that TLR7/8 can detect than the SARS-CoV genome, suggesting SARS-CoV-2 causes innate immune hyperactivation [206]. This observation suggested a strong pro-inflammatory response via TLR7/8 recognition. On the other hand, a larger number of SARS-CoV-2 fragments that TLR7/8 identified suggested that rapid release of type I IFNs by TLR7/8 influences the severity of SARS-CoV-2 by changing dendritic Cell (DC) growth, maturation, and apoptosis, and virus-specific cytotoxic responses produced by T lymphocytes and cytotoxicity of natural killer cells [206]. As DC function has been shown to be reduced, attempts to reverse this negative effect may be effective in Covid-19 treatment [207]. COVID-19 patients showed increased blood levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which are produced by the TLR7/8 pathways [202]. This could be attributed to an increase in TLR7/8 recognizing antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) (a TLR7/8 activating DAMP) in COVID-19 patients [187,208,209]. TLR7 and TLR8 activation could be employed to improve viral immunity as a potential therapeutic therapy. Based on data analysis collected from mice models treated with imiquimod following influenza A infection, imiquimod, a dual TLR7/8 agonist, has been proposed as a viable treatment for COVID-19 patients [210]. Direct infusion of imiquimod into the lungs lowers viral multiplication, avoids pulmonary inflammation and leukocyte infiltration; protects against pulmonary dysfunction worsening; and elevates pulmonary immunoglobulins and bronchiole fluid antibodies (such as IgG1, IgG2a, IgE, and IgM) [211]. Due to its role in increasing antigen-specific antibody production and enhancing the immune response for viral clearance, imiquimod could be used both for COVID-19 therapeutic treatment and as an adjuvant in the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [212,213].

5.6. C-Lectin Type Receptors Involved with SARS-CoV-2

C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) are a large family of transmembrane-soluble pattern recognition receptors that contain one or more conserved carbohydrate-recognition domains [214,215]. Such receptors can help in the calcium-dependent recognition of glycosylation marks present on pathogens’ proteins [216]. CLRs interact with mannose, fucose, and glucan mono- and polysaccharide structures to identify infections [217]. PAMP recognition by CLRs results in pathogen uptake, breakdown, and antigen presentation [218]. CLRs can as well connect with other PRRs, such as TLRs, allowing for the strengthening or weakening of innate immunity inflammatory responses by increasing or decreasing receptor activation and signal transduction [219,220]. In vitro study models have demonstrated a direct relationship between selective CLRs and SARS-CoV-2 spike protein mannosylated and N- and O-glycans [221].

6. Conclusions

The coronavirus disease COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, spreads mainly through person-to-person contact. SARS-CoV-2 is one of seven identified human coronaviruses that can cause serious illnesses. SARS-CoV-2 can trigger a respiratory tract infection, ranging from mild to deadly, and can cause respiratory failure, septic shock, pneumonia, heart, and liver complications, and may lead to death.

We covered the history and progression of human coronaviruses in this paper and the various host-cell receptors that may be engaged in the viral entry mechanism, showing that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can use multiple receptors to enter the host-cells. Understanding the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection requires determining the pathway through which the virus components bind to host-cell receptors. The information gathered in this study can be used as a guided tool to investigate how different cell types interact with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, while supported experimental investigations are required to explain the susceptibility differences to the viral infection. Afterward, we could ultimately be able to explain why some people are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection than others. In addition, it could help researchers understand how to specifically target the SARS-CoV-2 virus with drugs and immunotherapies to treat COVID-19 symptoms and improve the vaccine development research pipeline to prevent the disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.E.; resources, I.M.I., M.M., A.M.E., F.G.A., E.B.A., F.N., K.Y., S.M.M., I.M.S., A.N., A.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.I., M.M., A.M.E., F.G.A., E.B.A.; F.N., K.Y., S.M.M., I.M.S., A.N., A.A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.N., A.A.E.; visualization, A.A.E., I.M.I., E.B.A.; supervision, A.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF), grant number 44575.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based upon work supported by The Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF), grant no. 44575, The Egyptian Scientific Society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

References

- Payne, S. Family Coronaviridae. Viruses 2017, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, P.E.; Mitra, S.; Holland, T.C. Basics of virology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 123, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.F.; To, K.K.; Tse, H.; Jin, D.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: Lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Huang, Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Yuen, K.-Y. Coronavirus Genomics and Bioinformatics Analysis. Viruses 2010, 2, 1804–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, W.B.; McIntosh, K.; Dees, J.H.; Chanock, R.M. Morphogenesis of Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus and a Related Human Virus (Strain 229E). J. Virol. 1967, 1, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, C.F.; Dillon, M.B. Multiscale Airborne Infectious Disease Transmission. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, 02314–02320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, J.; Blicharz-Domańska, K. Coronaviruses in avian species—Review with focus on epidemiology and diagnosis in wild birds. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 62, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.X.; Ng, Y.L.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus-Host Interactions. Diseases 2016, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, C.; Preiser, W.; Günther, S.; Schmitz, H.; Doerr, H.W. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Identification of the etiological agent. Trends Mol. Med. 2003, 9, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Yan, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Zhou, W.; Rao, Z. Structural characterization of the HCoV-229E fusion core. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belouzard, S.; Millet, J.K.; Licitra, B.N.; Whittaker, G.R. Mechanisms of Coronavirus Cell Entry Mediated by the Viral Spike Protein. Viruses 2012, 4, 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapikian, Z. The coronaviruses. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1975, 28, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gerna, G.; Campanini, G.; Rovida, F.; Percivalle, E.; Sarasini, A.; Marchi, A.; Baldanti, F. Genetic variability of human coronavirus OC43-, 229E-, and NL63-like strains and their association with lower respiratory tract infections of hospitalized infants and immunocompromised patients. J. Med. Virol. 2006, 78, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas, S.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Alghnam, S.A.; Alhabib, K.F.; Almadi, M.A.H.; Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Bedi, N.; El Tantawi, M.; Krish, V.S.; Memish, Z.A.; et al. The burden of disease in Saudi Arabia 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e195–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dorzi, H.M.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Peiris, J.M.; Arabi, Y.M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. SARS MERS Other Viral Lung Infect. 2016, 2016, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, H.M.; Elkhatib, W.F.; Rahman, M.; Elshabrawy, H.A. Insights into the Recent 2019 Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Light of Past Human Coronavirus Outbreaks. Pathogens 2020, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J. SARS-CoV-2: An Emerging Coronavirus that Causes a Global Threat. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, D.; Giovannetti, M.; Ciccozzi, A.; Spoto, S.; Angeletti, S.; Ciccozzi, M. The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, N.N.C.; Palissery, S.; Sebastian, H. Corona Viruses: A Review on SARS, MERS and COVID-19. Microbiol. Insights 2021, 14, 11786361211002480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, D.A.; Baric, R.S. Coronavirus Genome Structure and Replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 287, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, A.A.T.; Fatima, K.; Mohammad, T.; Fatima, U.; Singh, I.K.; Singh, A.; Atif, S.M.; Hariprasad, G.; Hasan, G.M.; Hassan, I. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bárcena, M.; Oostergetel, G.T.; Bartelink, W.; Faas, F.G.A.; Verkleij, A.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Koster, A.J.; Bosch, B.J. Cryo-electron tomography of mouse hepatitis virus: Insights into the structure of the coronavirion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, B.W.; Adair, B.D.; Yoshioka, C.; Quispe, J.D.; Orca, G.; Kuhn, P.; Milligan, R.A.; Yeager, M.; Buchmeier, M.J. Supramolecular Architecture of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Revealed by Electron Cryomicroscopy. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7918–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjuanes, L.; Almazán, F.; Sola, I.; Zuñiga, S. Biochemical Aspects of Coronavirus Replication and Virus-Host Interaction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, S.; Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 7, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Z.; Oton, J.; Qu, K.; Cortese, M.; Zila, V.; McKeane, L.; Nakane, T.; Zivanov, J.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cerikan, B.; et al. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 2020, 588, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y.; et al. Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulswit, R.J.; De Haan, C.A.; Bosch, B.J. Coronavirus Spike Protein and Tropism Changes. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, X.; et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Physiological and molecular triggers for SARS-CoV membrane fusion and entry into host cells. Virology 2018, 517, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.-F.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.-W. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, P.; Pringle, C.R.; Easton, A.J. Heptad Repeat Sequences are Located Adjacent to Hydrophobic Regions in Several Types of Virus Fusion Glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.J.; van der Zee, R.; de Haan, C.A.; Rottier, P.J.M. The Coronavirus Spike Protein Is a Class I Virus Fusion Protein: Structural and Functional Characterization of the Fusion Core Complex. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 8801–8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; et al. Fusion mechanism of 2019-nCoV and fusion inhibitors targeting HR1 domain in spike protein. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalathiya, U.; Padariya, M.; Mayordomo, M.; Lisowska, M.; Nicholson, J.; Singh, A.; Baginski, M.; Fahraeus, R.; Carragher, N.; Ball, K.; et al. Highly Conserved Homotrimer Cavity Formed by the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein: A Novel Binding Site. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.M.; Elfiky, A.A. SARS-CoV-2 spike behavior in situ: A Cryo-EM images for a better understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Y.; Allen, J.D.; Wrapp, D.; McLellan, J.S.; Crispin, M. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science 2020, 369, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, C.; Jha, A.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, A. Chitosan derivatives: A suggestive evaluation for novel inhibitor discovery against wild type and variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Bidon, M.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Meng, B.; Xiang, J.; Wilson, I.A.; Yang, B. Crystal structure of the post-fusion core of the Human coronavirus 229E spike protein at 1.86 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2018, 74, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Lee, M.; Liao, S.-Y.; Hong, M. Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Investigation of the Structural Topology and Lipid Interactions of a Viral Fusion Protein Chimera Containing the Fusion Peptide and Transmembrane Domain. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6787–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, D.; Procknow, J.J. A New Virus Isolated from the Human Respiratory Tract. Exp. Biol. Med. 1966, 121, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburne, A.F.; Bynoe, M.L.; Tyrrell, D.A. Effects of a “new” human respiratory virus in volunteers. BMJ 1967, 3, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pene, F.; Merlat, A.; Vabret, A.; Rozenberg, F.; Buzyn, A.; Dreyfus, F.; Cariou, A.; Freymuth, F.; Lebon, P. Coronavirus 229E-Related Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, C.L.; Ashmun, R.A.; Williams, R.K.; Cardellichio, C.B.; Shapiro, L.H.; Look, A.T.; Holmes, K.V. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature 1992, 357, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mina-Osorio, P. The moonlighting enzyme CD13: Old and new functions to target. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J.; Aminopeptidase, N. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) as a Target for Anti-Cancer Agent Design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 2850–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickström, M.; Larsson, R.; Nygren, P.; Gullbo, J. Aminopeptidase N (CD13) as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Lin, Y.-L.; Peng, G.; Li, F. Structural basis for multifunctional roles of mammalian aminopeptidase N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17966–17971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Tomlinson, A.C.; Wong, A.H.; Zhou, D.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J.; Benlekbir, S.; Rubinstein, J.L.; Rini, J.M. The human coronavirus HCoV-229E S-protein structure and receptor binding. Elife 2019, 8, 51230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Domains and Functions of Spike Protein in Sars-Cov-2 in the Context of Vaccine Design. Viruses 2021, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; van der Hoek, L.; Ben Berkhout, A.; Lu, M. Core Structure of S2 from the Human Coronavirus NL63 Spike Glycoprotein. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15205–15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Lou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pang, H.; Tien, P.; Gao, G.F.; Rao, Z. Crystal Structure of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein Fusion Core. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49414–49419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wu, T.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: What we know. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groneberg, D.A.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Zabel, P. Molecular mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Respir. Res. 2005, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.J.; Zheng, B.J.; He, Y.Q.; Liu, X.L.; Zhuang, Z.X.; Cheung, C.L.; Luo, S.W.; Li, P.H.; Zhang, L.J.; Butt, K.M.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Viruses Related to the SARS Coronavirus from Animals in Southern China. Science 2003, 302, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groneberg, D.; Zhang, L.; Welte, T.; Zabel, P.; Chung, K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Global initiatives for disease diagnosis. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2003, 96, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Peiris, J. Coronaviruses. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, A.A.; Perlman, S. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: Implications for SARS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Squeglia, F.; Maga, G.; Berisio, R. A Structural View of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Replication Machinery: RNA Synthesis, Proofreading and Final Capping. Cells 2020, 9, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of SARS Coronavirus Spike Receptor-Binding Domain Complexed with Receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.K.; Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. A 193-Amino Acid Fragment of the SARS Coronavirus S Protein Efficiently Binds Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 3197–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, A.-W.; Axmann, M.; Pfefferle, S.; Drosten, C.; Meyer, B. A hexapeptide of the receptor-binding domain of SARS corona virus spike protein blocks viral entry into host cells via the human receptor ACE2. Antivir. Res. 2012, 94, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffers, S.A.; Tusell, S.M.; Gillim-Ross, L.; Hemmila, E.M.; Achenbach, J.E.; Babcock, G.J.; Thomas, W.D.; Thackray, L.B.; Young, M.D.; Mason, R.J.; et al. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15748–15753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “MERS Spotlight,” Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal (ISSN 1080-6059). 2021. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/spotlight/mers (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Al-Osail, A.M.; Al-Wazzah, M.J. The history and epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2017, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timen, A.; Isken, L.D.; Willemse, P.; Berkmortel, F.V.D.; Koopmans, M.P.; Van Oudheusden, D.E.; Bleeker-Rovers, C.P.; Brouwer, A.E.; Grol, R.P.; Hulscher, M.E.; et al. Retrospective Evaluation of Control Measures for Contacts of Patient with Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailles, A.; Blanckaert, K.; Chaud, P.; Van der Werf, S.; Lina, B.; Caro, V.; Campese, C.; Guéry, B.; Prouvost, H.; Lemaire, X.; et al. First cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infections in France, investigations and implications for the prevention of human-to-human transmission, France, May 2013. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. MERS Situation Update, January 2020, World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/mers-cov/mers-outbreaks.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Buchholz, U.; Müller, M.A.; Nitsche, A.; Sanewski, A.; Wevering, N.; Bauer-Balci, T.; Bonin, F.; Drosten, C.; Schweiger, B.; Wolff, T.; et al. Contact investigation of a case of human novel coronavirus infection treated in a German hospital, October-November 2012. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-J.; Choi, W.S.; Jung, Y.; Kiem, S.; Seol, H.; Woo, H.; Choi, Y.; Son, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, Y.-S.; et al. Surveillance of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (CoV) infection in healthcare workers after contact with confirmed MERS patients: Incidence and risk factors of MERS-CoV seropositivity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, H.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assiri, A.; McGeer, A.; Perl, T.M.; Price, C.S.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Cummings, D.A.; Alabdullatif, Z.N.; Assad, M.; Almulhim, A.; Makhdoom, H.; et al. Hospital Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Yang, Y.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.-L.; Baric, R.S.; Li, F. Crystal Structure of the Receptor-Binding Domain from Newly Emerged Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10777–10783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, S.; Balkhy, H.; Gabere, M.N. Current treatment options and the role of peptides as potential therapeutic components for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS): A review. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindler, E.; Thiel, V.; Weber, F. Interaction of SARS and MERS Coronaviruses with the Antiviral Interferon Response. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubarak, A.; Alturaiki, W.; Hemida, M.G. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Infection, Immunological Response, and Vaccine Development. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 6491738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, V.S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S.L.; Dekkers, D.H.W.; Müller, M.A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J.A.A.; Zaki, A.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 2013, 495, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Bao, J.; et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 500, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lu, G.; Qi, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Geng, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, H.; et al. Structure of the Fusion Core and Inhibition of Fusion by a Heptad Repeat Peptide Derived from the S Protein of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13134–13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-M.; Chu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wong, B.H.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, D.; Leung, S.P.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Yeung, M.L.; et al. Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 5 Is an Important Surface Attachment Factor That Facilitates Entry of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9114–9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnest, J.T.; Hantak, M.P.; Li, K.; Jr, P.B.M.; Perlman, S.; Gallagher, T. The tetraspanin CD9 facilitates MERS-coronavirus entry by scaffolding host cell receptors and proteases. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Chan, C.M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, J.; Au-Yeung, R.K.H.; Sze, K.H.; Yang, D.; Shuai, H.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and bat coronavirus HKU9 both can utilize GRP78 for attachment onto host cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 11709–11726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E.; Li, K.; Barlan, A.; Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S.; McCray, P.B.; Gallagher, T. Proteolytic processing of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spikes expands virus tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12262–12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, E.; Hantak, M.P.; Galpalli, G.G.; Gallagher, T. Evaluating MERS-CoV Entry Pathways. PCR Detect. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 2099, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirato, K.; Kanou, K.; Kawase, M.; Matsuyama, S. Clinical Isolates of Human Coronavirus 229E Bypass the Endosome for Cell Entry. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01387-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, L.; Li, F.; Jiang, S. MERS-CoV spike protein: A key target for antivirals. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, B.J.; Martina, B.E.E.; van der Zee, R.; Lepault, J.; Haijema, B.J.; Versluis, C.; Heck, A.; de Groot, R.; Osterhaus, A.; Rottier, P.J.M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection inhibition using spike protein heptad repeat-derived peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8455–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer. “COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC”, Worldometer Data. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Ibrahim, I.M.; Abdelmalek, D.H.; Elshahat, M.E.; Elfiky, A.A. COVID-19 spike-host cell receptor GRP78 binding site prediction. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; Macary, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-U.; Kim, M.-J.; Ra, S.; Lee, J.; Bae, S.; Jung, J.; Kim, S.-H. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with mild COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 948.e1–948.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 395, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.S.S.; Biswal, S.; Singha, D.; Rana, M.K. Binding insight of clinically oriented drug famotidine with the identified potential target of SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 5327–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, P.; Liu, K.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.-W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, G.-Q. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: Interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ye, D.; Mullick, A.E.; Li, Z.; Danser, A.J.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Effects of Renin-Angiotensin Inhibition on ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2) and TMPRSS2 (Transmembrane Protease Serine 2) Expression: Insights Into COVID-19. Hypertension 2020, 76, e29–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Wang, A.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Y. Coexistence effect of hypertension and angiotensin II on the risk of coronary heart disease: A population-based prospective cohort study among Inner Mongolians in China. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019, 35, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, A.H. The Role of Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists in the Management of Diabetes. Blood Press. 2001, 10, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Macedo, A.; Silva, P.G.M.D.B.E.; Moll-Bernardes, R.J.; Feldman, A.; Arruda, G.D.S.; De Souza, A.S.; De Albuquerque, D.C.; Mazza, L.; Santos, M.F.; et al. Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Impact on adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—The BRACE CORONA Trial. Am. Heart J. 2020, 226, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, J.H. Hypothesis: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of severe COVID-19. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerstein, R.; Kochen, M.M.; Messerli, F.H.; Gräni, C. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Do Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Have a Biphasic Effect? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, S.; MacIsaac, A.I.; Jennings, G.L.; Schlaich, M.P.; Inglis, S.C.; Arnold, R.; Kumar, S.; Thomas, L.; Wahi, S.; Lo, S.; et al. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19: Australian and New Zealand consensus statement. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Q.; Yang, K.; Wang, W.; Jiang, L.; Song, J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 46, 846–848, Erratum in 2020, 46, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inciardi, R.M.; Adamo, M.; Lupi, L.; Cani, D.S.; Di Pasquale, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Italia, L.; Zaccone, G.; Tedino, C.; Fabbricatore, D.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.S.; Dufort, E.M.; Udo, T.; Wilberschied, L.A.; Kumar, J.; Tesoriero, J.; Weinberg, P.; Kirkwood, J.; Muse, A.; DeHovitz, J.; et al. Association of Treatment with Hydroxychloroquine or Azithromycin with In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA 2020, 323, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, J.A.S.; Uribarri, A.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; Aparisi, Á.; Catalá, P.; González-Juanatey, J.R. The presence of heart disease worsens prognosis in patients with COVID-19 TT—La presencia de cardiopatía agrava el pronóstico de los pacientes con COVID-19. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Zangrillo, A.; Zanella, A. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Hayek, S.S.; Wang, W.; Chan, L.; Mathews, K.S.; Melamed, M.L.; Brenner, S.K.; Leonberg-Yoo, A.; Schenck, E.J.; Radbel, J.; et al. Factors Associated with Death in Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.; Dubey, P.; Benitez, J.; Torres, J.P.; Reddy, S.; Shokar, N.; Aung, K.; Mukherjee, D.; Dwivedi, A.K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of geographic differences in comorbidities and associated severity and mortality among individuals with COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamichi, K.; Shen, J.Z.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, A.; Roberts, E.A.; Simonson, P.D.; Roychoudhury, P.; Andriesen, J.; Randhawa, A.K.; Mathias, P.C.; et al. Hospitalization and mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 viral clades in COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gallagher, K.; Shek, A.; Bean, D.M.; Bendayan, R.; Papachristidis, A.; Teo, J.T.H.; Dobson, R.J.B.; Shah, A.M.; Zakeri, R. Pre-existing cardiovascular disease rather than cardiovascular risk factors drives mortality in COVID-19. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaux, C.A.; Rolain, J.-M.; Raoult, D. ACE2 receptor polymorphism: Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, hypertension, multi-organ failure, and COVID-19 disease outcome. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, D.N. Brief Review on COVID-19: The 2020 Pandemic Caused by SARS-CoV-2. Cureus 2020, 12, e7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, L.; Cai, J.; Lei, F.; Qin, J.-J.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.-M.; Zhao, Y.-C.; Huang, X.; Lin, L.; et al. Association of Inpatient Use of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers with Mortality Among Patients with Hypertension Hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Velkoska, E.; Burrell, L.M. Emerging markers in cardiovascular disease: Where does angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 fit in? Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013, 40, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wada, J.; Hida, K.; Tsuchiyama, Y.; Hiragushi, K.; Shikata, K.; Wang, H.; Lin, S.; Kanwar, Y.S.; Makino, H. Collectrin, a Collecting Duct-specific Transmembrane Glycoprotein, Is a Novel Homolog of ACE2 and Is Developmentally Regulated in Embryonic Kidneys. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 17132–17139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, C.; Deng, T.; Yuan, Q.; Xiao, X. The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Lu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, L. A potential inhibitory role for integrin in the receptor targeting of SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Sun, H.; Bu, X.; Wan, G. New Strategy for COVID-19: An Evolutionary Role for RGD Motif in SARS-CoV-2 and Potential Inhibitors for Virus Infection. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelman, R.; Bayatra, A.; Kessler, A.; Schwartz, A.; Ilan, Y. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 receptors as a means for reducing infectivity and improving antiviral and immune response: An algorithm-based method for overcoming resistance to antiviral agents. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElFiky, A.A. Natural products may interfere with SARS-CoV-2 attachment to the host cell. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 3194–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wey, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, R.; Lee, A.S. Role of the Unfolded Protein Response Regulator GRP78/BiP in Development, Cancer, and Neurological Disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiky, A.A.; Baghdady, A.M.; Ali, S.A.; Ahmed, M.I. GRP78 targeting: Hitting two birds with a stone. Life Sci. 2020, 260, 118317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.M.; Abdelmalek, D.H.; Elfiky, A.A. GRP78: A cell’s response to stress. Life Sci. 2019, 226, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köseler, A.; Sabirli, R.; Gören, T.; Türkçüer, I.; Kurt, Ö. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Markers in SARS-COV-2 Infection and Pneumonia: Case-Control Study. In Vivo 2020, 34, 1645–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmeira, A.; Sousa, M.E.; Köseler, A.; Sabirli, R.; Gören, T.; Türkçüer, I.; Kurt, Ö.; Pinto, M.M.; Vasconcelos, M.H. Preliminary Virtual Screening Studies to Identify GRP78 Inhibitors Which May Interfere with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, T.; Liu, M.; Luo, G.; Bruno, V.; Phan, Q.T.; Waring, A.J.; Edwards, J.E.; Filler, S.G.; Yeaman, M.R.; Ibrahim, A.S. CotH3 mediates fungal invasion of host cells during mucormycosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgohary, A.M.; Elfiky, A.A.; Barakat, K. GRP78: A possible relationship of COVID-19 and the mucormycosis; in silico perspective. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 139, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElFiky, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.M. Zika virus envelope—Heat shock protein A5 (GRP78) binding site prediction. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 5248–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElFiky, A.A. Ebola virus glycoprotein GP1—Host cell-surface HSPA5 binding site prediction. Cell Stress Chaperones 2020, 25, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElFiky, A.A. Human papillomavirus E6: Host cell receptor, GRP78, binding site prediction. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 3759–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lillo, A.M.; Steiniger, S.C.J.; Liu, Y.; Ballatore, C.; Anichini, A.; Mortarini, R.; Kaufmann, G.F.; Zhou, B.; Felding-Habermann, B.; et al. Targeting Heat Shock Proteins on Cancer Cells: Selection, Characterization, and Cell-Penetrating Properties of a Peptidic GRP78 Ligand. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 9434–9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, J.A.; Tremblay, B.J.-M.; Mansfield, M.J.; Woody, O.; Lobb, B.; Banerjee, A.; Chandiramohan, A.; Tiessen, N.; Cao, Q.; Dvorkin-Gheva, A.; et al. Gene expression and in situ protein profiling of candidate SARS-CoV-2 receptors in human airway epithelial cells and lung tissue. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulou, L.; Holt, A.C.; Medzhitov, R.; Flavell, R.A. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 413, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karikó, K.; Bhuyan, P.; Capodici, J.; Weissman, D. Small Interfering RNAs Mediate Sequence-Independent Gene Suppression and Induce Immune Activation by Signaling through Toll-Like Receptor 3. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 6545–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfiky, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Ismail, A.M.; Elshemey, W.M. A possible role for GRP78 in cross vaccination against COVID-19. J. Infect. 2021, 82, 282–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElFiky, A.A. SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Heat Shock Protein A5 (GRP78) Recognition may be Related to the Immersed Human Coronaviruses. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 577467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfiky, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.M. Host-cell recognition through GRP78 is enhanced in the new UK variant of SARS-CoV-2, in silico. J. Infect. 2021, 82, 186–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, I.M.; Elfiky, A.A.; Elgohary, A.M. Recognition through GRP78 is enhanced in the UK, South African, and Brazilian variants of SARS-CoV-2; An in silico perspective. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 562, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarember, K.A.; Godowski, P.J. Tissue Expression of Human Toll-Like Receptors and Differential Regulation of Toll-Like Receptor mRNAs in Leukocytes in Response to Microbes, Their Products, and Cytokines. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, K. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 2004, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.K.; Mullen, G.E.; Leifer, C.A.; Mazzoni, A.; Davies, D.R.; Segal, D.M. Leucine-rich repeats and pathogen recognition in Toll-like receptors. Trends Immunol. 2003, 24, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botos, I.; Segal, D.M.; Davies, D.R. The Structural Biology of Toll-like Receptors. Structure 2011, 19, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs): The Derivatives and Triggers of Inflammation. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, T.; Kawai, T. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, T.H. Pathogen Recognition and Inflammatory Signaling in Innate Immune Defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komai, K.; Shichita, T.; Ito, M.; Kanamori, M.; Chikuma, S.; Yoshimura, A. Role of scavenger receptors as damage-associated molecular pattern receptors in Toll-like receptor activation. Int. Immunol. 2017, 29, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.G.; Orr, M.; Fox, C. Key roles of adjuvants in modern vaccines. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, A.; Herrup, E.A.; Warren, H.S.; Trigilio, J.; Shin, H.-S.; Valentine, C.; Hellman, J. MyD88-Dependent and MyD88-Independent Pathways in Synergy, Priming, and Tolerance between TLR Agonists. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Wang, H.; Hajishengallis, G.N.; Martin, M. TLR-signaling Networks: An integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Sato, S.; Hemmi, H.; Hoshino, K.; Kaisho, T.; Sanjo, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Sugiyama, M.; Okabe, M.; Takeda, K.; et al. Role of Adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-Independent Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway. Science 2003, 301, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Pathogen recognition in the innate immune response. Biochem. J. 2009, 420, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozinsky, A.; Underhill, D.; Fontenot, J.D.; Hajjar, A.; Smith, K.D.; Wilson, C.B.; Schroeder, L.; Aderem, A. The repertoire for pattern recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system is defined by cooperation between Toll-like receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13766–13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoi, Y.; Shibata, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kanno, A.; Murakami, Y.; Li, X.; Kasahara, T.; Miyake, K. Lipopeptides are signaled by Toll-like receptor 1, 2 and 6 in endolysosomes. Int. Immunol. 2014, 26, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Misch, E.A.; Macdonald, M.; Ranjit, C.; Sapkota, B.R.; Wells, R.D.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Kaplan, G.; Hawn, T.R. Human TLR1 Deficiency Is Associated with Impaired Mycobacterial Signaling and Protection from Leprosy Reversal Reaction. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008, 2, e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buwitt-Beckmann, U.; Heine, H.; Wiesmüller, K.-H.; Jung, G.; Brock, R.; Akira, S.; Ulmer, A.J. TLR1- and TLR6-independent Recognition of Bacterial Lipopeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9049–9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, K.; Gloria, Y.C.; Wolz, O.; Herster, F.; Sharma, L.; Dillen, C.A.; Täumer, C.; Dickhöfer, S.; Bittner, Z.; Dang, T.; et al. The fungal ligand chitin directly binds TLR 2 and triggers inflammation dependent on oligomer size. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e201846065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, A.; Otero, K.; Czerkowicz, J.M.; Kerns, H.M.; Shapiro, R.I.; Ranger, A.M.; Otipoby, K.L.; Taylor, F.R.; Cameron, T.O.; Viney, J.L.; et al. Anti- BDCA 2 monoclonal antibody inhibits plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation through Fc-dependent and Fc-independent mechanisms. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehme, K.W.; Guerrero, M.; Compton, T. Human Cytomegalovirus Envelope Glycoproteins B and H Are Necessary for TLR2 Activation in Permissive Cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7094–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, C.D.; Ross, S.R. Toll-Like Receptor 2-Mediated Innate Immune Responses against Junín Virus in Mice Lead to Antiviral Adaptive Immune Responses during Systemic Infection and Do Not Affect Viral Replication in the Brain. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7703–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, K.; Riekenberg, S.; Heine, H.; Debarry, J.; Lang, R.; Mages, J.; Buwitt-Beckmann, U.; Röschmann, K.; Jung, G.; Wiesmüller, K.-H.; et al. Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 expands the ligand spectrum but does not lead to differential signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 83, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumiya, M.; Stylianou, E.; Griffiths, K.; Lang, Z.; Meyer, J.; Harris, S.A.; Rowland, R.; Minassian, A.; Pathan, A.A.; Fletcher, H.; et al. Roles for Treg Expansion and HMGB1 Signaling through the TLR1-2-6 Axis in Determining the Magnitude of the Antigen-Specific Immune Response to MVA85A. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodo, F.; Bruijns, S.C.; Rodriguez, E.; Li, R.E.; Molinaro, A.; Silipo, A.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Garcia-Rivera, D.; Valdes-Balbin, Y.; Verez-Bencomo, V.; et al. Novel ACE2-Independent Carbohydrate-Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Host Lectins and Lung Microbiota. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, H.; Jégouzo, S.A.F.; Rex, M.J.; Drickamer, K.; Weis, W.I.; Taylor, M.E. Mechanism of pathogen recognition by human dectin-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13402–13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Wagner, V.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. Double-Stranded RNA Is Produced by Positive-Strand RNA Viruses and DNA Viruses but Not in Detectable Amounts by Negative-Strand RNA Viruses. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5059–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatematsu, M.; Nishikawa, F.; Seya, T.; Matsumoto, M. Toll-like receptor 3 recognizes incomplete stem structures in single-stranded viral RNA. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Ni, H.; Capodici, J.; Lamphier, M.; Weissman, D. mRNA Is an Endogenous Ligand for Toll-like Receptor 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 12542–12550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, M.V.; Thomas, B.; Machado-Aranda, D.; Dolgachev, V.A.; Ramakrishnan, S.K.; Talarico, N.; Cavassani, K.; Sherman, M.A.; Hemmila, M.R.; Kunkel, S.L.; et al. Double-Stranded RNA Interacts with Toll-Like Receptor 3 in Driving the Acute Inflammatory Response Following Lung Contusion. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, e1054–e1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, J.; Prinz, N.; Lorenz, M.; Bauer, S.; Chapman, J.; Lackner, K.J.; von Landenberg, P. TLR7 and TLR8 ligands and antiphospholipid antibodies show synergistic effects on the induction of IL-1β and caspase-1 in monocytes and dendritic cells. Immunobiology 2009, 214, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadanec, L.; McSweeney, K.; Qaradakhi, T.; Ali, B.; Zulli, A.; Apostolopoulos, V. Can SARS-CoV-2 Virus Use Multiple Receptors to Enter Host Cells? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaure, C.; Liu, Y. A Comparative Review of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Expression and Functionality in Different Animal Species. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Lee, J.-O. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2013, 45, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, N.; Turvey, S.E. Role of human TLR4 in respiratory syncytial virus-induced NF-κB activation, viral entry and replication. Innate Immun. 2012, 18, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Popova, L.; Kwinn, L.A.; Haynes, L.M.; Jones, L.P.; Tripp, R.; Walsh, E.E.; Freeman, M.W.; Golenbock, D.T.; Anderson, L.J.; et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, H. Inhibition of Toll-Like Receptor Signaling as a Promising Therapy for Inflammatory Diseases: A Journey from Molecular to Nano Therapeutics. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Mukherjee, S. In silico studies on the comparative characterization of the interactions of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with ACE-2 receptor homologs and human TLRs. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.C.; Rumbo, M.; Sirard, J.-C. Bacterial flagellins: Mediators of pathogenicity and host immune responses in mucosa. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.S.; Jeon, Y.J.; Namgung, B.; Hong, M.; Yoon, S.-I. A conserved TLR5 binding and activation hot spot on flagellin. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, M.; Windish, H.P.; Fox, C.; Reed, S.G. Use of defined TLR ligands as adjuvants within human vaccines. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 239, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, I.A.; Dar, P.; Shahnawaz, I.; Jaume, J.C.; Lee, J.H. Bacterial flagellin—A potent immunomodulatory agent. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felgner, S.; Spöring, I.; Pawar, V.; Kocijancic, D.; Preusse, M.; Falk, C.; Rohde, M.; Häussler, S.; Weiss, S.; Erhardt, M. The immunogenic potential of bacterial flagella for Salmonella -mediated tumor therapy. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 147, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgel, A.-F.; Cayet, D.; Pizzorno, M.A.; Rosa-Calatrava, M.; Paget, C.; Sencio, V.; Dubuisson, J.; Trottein, F.; Sirard, J.-C.; Carnoy, C. Toll-like receptor 5 agonist flagellin reduces influenza A virus replication independently of type I interferon and interleukin 22 and improves antiviral efficacy of oseltamivir. Antivir. Res. 2019, 168, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassin-Delyle, S.; Abrial, C.; Salvator, H.; Brollo, M.; Naline, E.; DeVillier, P. The Role of Toll-Like Receptors in the Production of Cytokines by Human Lung Macrophages. J. Innate Immun. 2020, 12, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Puel, A.; Zhang, S.; Eidenschenk, C.; Ku, C.-L.; Casrouge, A.; Picard, C.; von Bernuth, H.; Senechal, B.; Plancoulaine, S.; et al. Human TLR-7-, -8-, and -9-Mediated Induction of IFN-α/β and -λ Is IRAK-4 Dependent and Redundant for Protective Immunity to Viruses. Immunity 2005, 23, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hjorth, C.K.; Dommer, A.C.; Harbison, A.M.; Fogarty, C.A.; Barros, E.P.; Taylor, B.C.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Central Sci. 2020, 6, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Fehr, A.R.; Zheng, J.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Abrahante, J.E.; Mack, M.; Sompallae, R.; McCray, P.B.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. IFN-I response timing relative to virus replication determines MERS coronavirus infection outcomes. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Eutimio, M.A.; López-Macías, C.; Pastelin-Palacios, R. Bioinformatic analysis and identification of single-stranded RNA sequences recognized by TLR7/8 in the SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV genomes. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campana, P.; Parisi, V.; Leosco, D.; Bencivenga, D.; Della Ragione, F.; Borriello, A. Dendritic Cells and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Still an Unclarified Connection. Cells 2020, 9, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, N.; Clemens, N.; Strand, D.; Pütz, I.; Lorenz, M.; Daiber, A.; Stein, P.; Degreif, A.; Radsak, M.; Schild, H.; et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies induce translocation of TLR7 and TLR8 to the endosome in human monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood 2011, 118, 2322–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döring, Y.; Hurst, J.; Lorenz, M.; Prinz, N.; Clemens, N.; Drechsler, M.D.; Bauer, S.; Chapman, J.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Blank, M. Human antiphospholipid antibodies induce TNFα in monocytes via Toll-like receptor 8. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Alexandris, N.; Konstantinou, E.; Mesiakaris, K.; Zanidis, C.; Farsalinos, K.; Poulas, K. Imiquimod—A toll like receptor 7 agonist—Is an ideal option for management of COVID 19. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, E.E.; Erlich, J.; Liong, F.; Luong, R.; Liong, S.; Bozinovski, S.; Seow, H.; O’Leary, J.J.; Brooks, D.A.; Vlahos, R.; et al. Intranasal and epicutaneous administration of Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) agonists provides protection against influenza A virus-induced morbidity in mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; To, K.; Zhang, J.; Lee, A.C.Y.; Zhu, H.; Mak, W.W.N.; Hung, I.F.N.; Yuen, K.-Y. Co-stimulation with TLR7 Agonist Imiquimod and Inactivated Influenza Virus Particles Promotes Mouse B Cell Activation, Differentiation, and Accelerated Antigen Specific Antibody Production. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; To, K.; Zhu, H.-S.; Lee, A.C.Y.; Li, C.-G.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Hung, I.F.N.; Yuen, K.-Y. Toll-Like Receptor 7 Agonist Imiquimod in Combination with Influenza Vaccine Expedites and Augments Humoral Immune Responses against Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Virus Infection in BALB/c Mice. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, S.C.; Dickerson, I.M. Direct Interactions between Calcitonin-Like Receptor (CLR) and CGRP-Receptor Component Protein (RCP) Regulate CGRP Receptor Signaling. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 1850–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Gringhuis, S.I. C-type lectin receptors in the control of T helper cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zeng, J.; Jia, N.; Stavenhagen, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Hume, A.J.; Mühlberger, E.; van Die, I.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Interacts with Multiple Innate Immune Receptors. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Hsu, T.-L.; Huang, S.K.; Hsieh, S.-L.; Wong, C.-H.; Lee, Y.C. Survey of immune-related, mannose/fucose-binding C-type lectin receptors reveals widely divergent sugar-binding specificities. Glycobiology 2010, 21, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreibelt, G.; Klinkenberg, L.J.J.; Cruz, L.J.; Tacken, P.J.; Tel, J.; Kreutz, M.; Adema, G.J.; Brown, G.D.; Figdor, C.G.; de Vries, I.J.M. The C-type lectin receptor CLEC9A mediates antigen uptake and (cross-)presentation by human blood BDCA3+ myeloid dendritic cells. Blood 2012, 119, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjestani, S.; Darnay, B.G.; Lin, X. Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-associated Factor 6 (TRAF6) and TGFβ-activated Kinase 1 (TAK1) Play Essential Roles in the C-type Lectin Receptor Signaling in Response to Candida albicans Infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44143–44150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantner, B.N.; Simmons, R.M.; Canavera, S.J.; Akira, S.; Underhill, D.M. Collaborative Induction of Inflammatory Responses by Dectin-1 and Toll-like Receptor 2. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amraie, R.; Napoleon, M.A.; Yin, W.; Berrigan, J.; Suder, E.; Zhao, G.; Olejnik, J.; Gummuluru, S.; Muhlberger, E.; Chitalia, V.; et al. CD209L/L-SIGN and CD209/DC-SIGN act as receptors for SARS-CoV-2 and are differentially expressed in lung and kidney epithelial and endothelial cells. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).