Abstract

Oxime derivatives are easily made, are non-hazardous and have long shelf lives. They contain weak N–O bonds that undergo homolytic scission, on appropriate thermal or photochemical stimulus, to initially release a pair of N- and O-centred radicals. This article reviews the use of these precursors for studying the structures, reactions and kinetics of the released radicals. Two classes have been exploited for radical generation; one comprises carbonyl oximes, principally oxime esters and amides, and the second comprises oxime ethers. Both classes release an iminyl radical together with an equal amount of a second oxygen-centred radical. The O-centred radicals derived from carbonyl oximes decarboxylate giving access to a variety of carbon-centred and nitrogen-centred species. Methods developed for homolytically dissociating the oxime derivatives include UV irradiation, conventional thermal and microwave heating. Photoredox catalytic methods succeed well with specially functionalised oximes and this aspect is also reviewed. Attention is also drawn to the key contributions made by EPR spectroscopy, aided by DFT computations, in elucidating the structures and dynamics of the transient intermediates.

1. Introduction

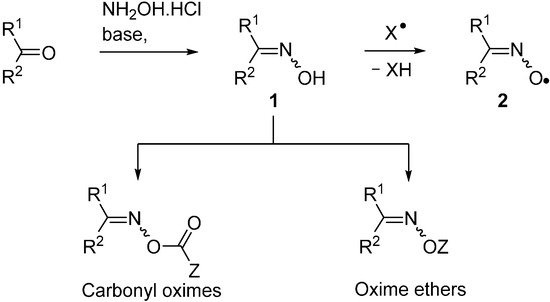

A huge variety of compounds containing the carbonyl functional group is available from natural and commercial sources. Of these, aldehydes and ketones can readily and efficiently be converted to oximes R1R2C=NOH (1) by treatment with hydroxylamine hydrochloride and a base. Alternatively, oximes can be prepared from reaction of organic and inorganic nitrites with various compounds containing acidic C–H atoms. Consequently, oximes are accessible in great diversity for further functional group transformations. A few instances of oximes themselves being used directly for radical generation are known. However, their O–H bonds are comparatively weak, usually in the range of 76–85 kcal·mol−1 [1] and, therefore, any radicals X• generated in their presence abstract these H-atoms with production of iminoxyl radicals 2 (see Scheme 1). Many iminoxyls have been generated and studied [2,3,4] and they resemble nitroxide (aminoxyl) radicals in a number of ways; especially in that most are persistent. Frequently, therefore, the presence of an oxime serves to impede further radical reactions.

Oximes are easily derivatised so that oxime esters (O-alkanoyl and O-aroyl oximes) and oxime ethers (O-alkyl and O-aryl oximes) are straightforward to make. The N–O bonds in these compounds are usually comparatively weak; ~50 kcal·mol−1 in oximes [5] and only 33–37 kcal·mol−1 in O-phenyl oxime ethers [6]. Homolytic scission of these N–O bonds can be accomplished either by photochemical or by thermal means thus yielding for each type an N-centred radical accompanied by one equivalent of its O-centred counterpart. For this reason, oxime derivatives, especially carbonyl-oximes containing the >C=N–OC(=O)– unit, are finding increasing use as selective sources for free radicals. They offer tangible advantages over traditional initiators, such as diacyl peroxides, azo-compounds or organotin hydrides; all of which have well-known troublesome features. Most oxime derivatives are easily handled; are non-toxic, non-pyrophoric and have long shelf lives. The field has expanded to encompass a huge range of structural elements resulting in diverse and varied possibilities for subsequent transformations of the radicals. These compound types are being subsumed into more environmentally friendly preparative methods and for new means of access to ranges of aza-heterocycles. This article reviews modern methods of releasing radicals from both these precursor types. It highlights how their use has enabled the structures, reactions and kinetics of sets of C-, N- and O-centred radicals to be elucidated in greater detail than heretofore.

Scheme 1.

Oximes, carbonyl oximes and oxime ethers; production of iminoxyl radicals.

Scheme 1.

Oximes, carbonyl oximes and oxime ethers; production of iminoxyl radicals.

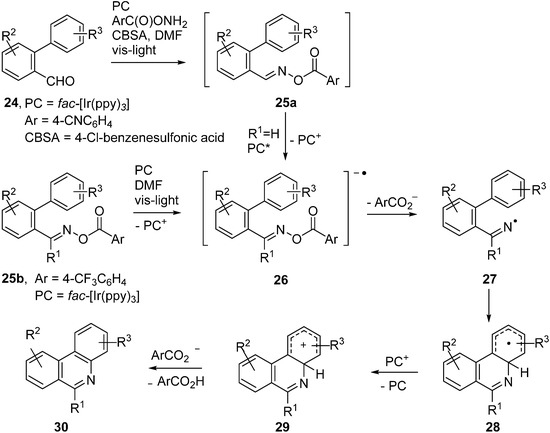

In earlier synthesis-orientated research, Forrester and co-workers employed oximeacetic acids MeCR(CH2)2CR1=NOCH2CO2H and their t-butyl peresters [7,8]. Hasebe’s group developed photochemical alkylations and arylations with oxime esters Ph2C=NOC(O)R [9,10] and Zard established ingenious preparative methodology from oxime benzoates PhRC=NOC(O)Ph [11], from O-benzoyl hydroxamic acid derivatives and from sulfenylimines R2C=NSAr [12,13,14]. Since the turn of the century, research has zeroed in on two particular sets of oxime-derived compounds: (a) carbonyl oxime derivatives and (b) O-aryl oxime ethers R1R2C=NOAr. Recent advances, important insights and details of some surprising outcomes are described with particular emphasis on mechanistic and computational aspects.

2. Oxime Esters and Related Carbonyl Oximes

2.1. General Features of Carbonyl Oxime Reactions

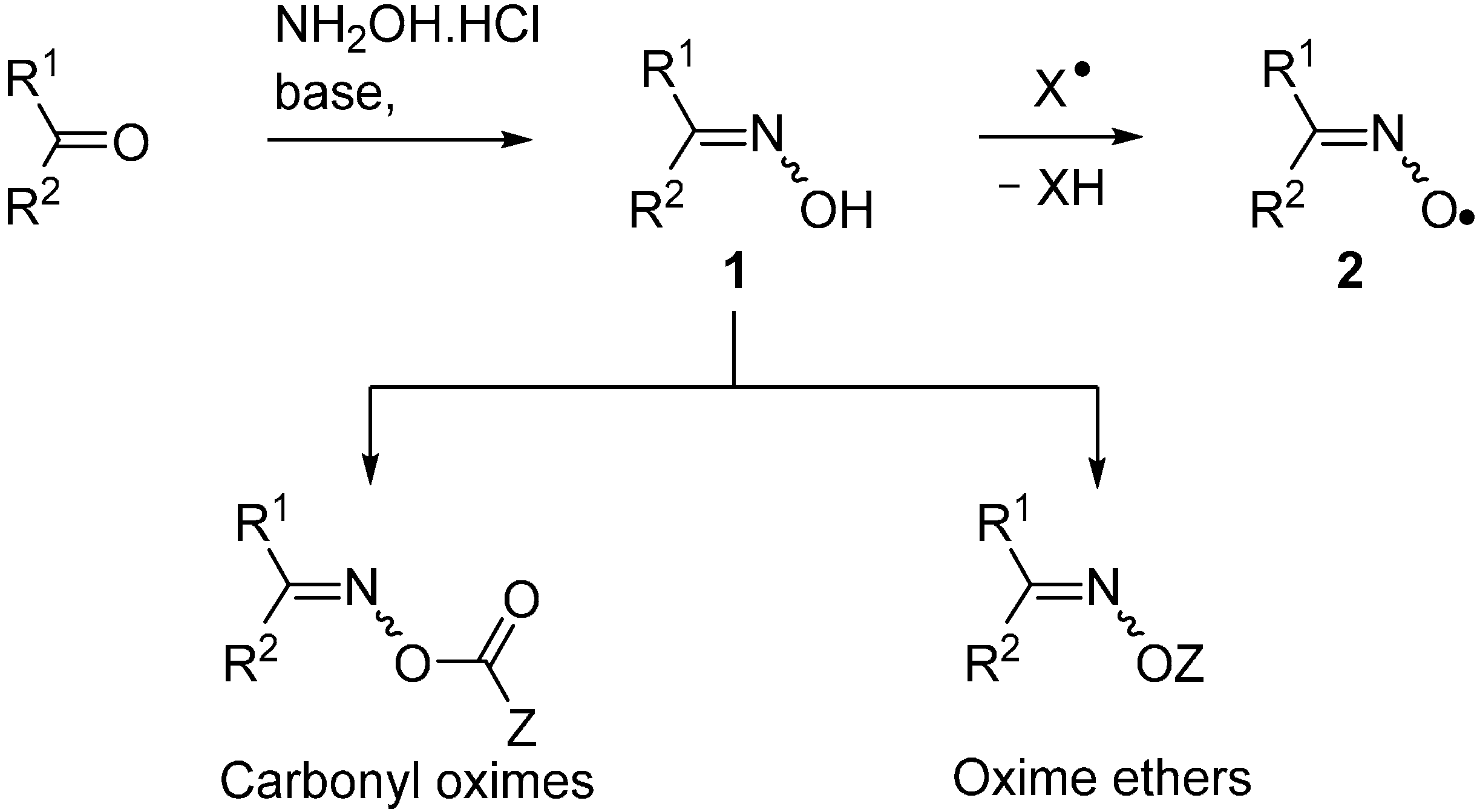

Generalised structures of the principal types of carbonyl oximes so far investigated are displayed in Chart 1. These carbonyl oxime types all have strong absorption bands in the 250–350 nm range and readily dissociate on UV irradiation in solution by cleavage of their N–O bonds. Cleavage of the O–C(O) bonds does not compete in solution under the normal conditions for organic reactions. Occasional observations of iminoxyl radicals (R1R2C=NO•), and products therefrom can most probably be attributed to residual trace impurities of the oximes from which the carbonyl oximes were prepared. Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations [B3LYP/6-31+G(d)] with model oxime esters 3 also indicated N–O cleavage was thermodynamically favoured over O–C(O) cleavage. It is apparent from Chart 1 that, by appropriate choice amongst these carbonyl oxime precursors, selective generation of radicals centred on either C-, N-, or O-atoms, with differing substitution patterns, can be achieved. The associated chemistry has been investigated spectroscopically and, of course, by end product analyses. The most successful and helpful method for mechanistic and dynamic information about the intermediates has been EPR spectroscopy coupled with QM computations. The synergy achievable by their mutual deployment has been demonstrated many times.

Chart 1.

Types of carbonyl oximes investigated for radical release.

Chart 1.

Types of carbonyl oximes investigated for radical release.

The efficiency of photochemical N–O bond homolysis depends strongly on the type of imine unit. Best radical yields were obtained when R1 and/or R2 were aromatic/heteroaromatic groups. Furthermore, incorporation of methoxy substituents in the aryl rings was usually also beneficial. In most photolyses, use of a photosensitizer such as 4-methoxyacetophenone (MAP) also proved advantageous. Energy transfer between the MAP excited state and the iminyl portion of the oxime derivative was probably promoted by π–π-stacking of their aryl units.

For all six types of carbonyl oxime (3–8), UV irradiation in hydrocarbon solutions, either straight or MAP sensitised, initially generated an iminyl radical (R1R2C=N•; designated Im) accompanied by an equivalent of a second species. All were therefore effective iminyl radical sources. Symmetrical dioxime oxalates 4 (R1 = R3 and R2 = R4) gave only one radical type and were particularly convenient for the study of iminyls. The discovery of these precursors permitted detailed EPR spectroscopic study of diverse iminyls’ structures and reactions. The second O-centred radicals released by carbonyl oximes (other than 4) included acyls and carbamoyls as well as novel and exotic species such as alkoxycarbonyloxyl (alkyl carbonate radicals) R3OC(O)O• and carbamoyloxyl R3R4NC(O)O• radicals. Subsequent transformations enabled C-centred alkyl, acyl and carbamoyl radicals, as well as N-centred aminyl radicals, to be benignly generated. Much inaccessible information about the behaviour of these species therefore became reachable.

None of the carbonyl oxime precursors dissociate cleanly by thermolyses in the usual temperature range of organic preparations (T < ~120 °C). Flash Vacuum Pyrolysis (ca. 650 °C) led to electrocyclic rather than radical reactions though these also had useful preparative connotations [15].

2.2. Iminyl Radical Structures and Transformations

In the past, for spectroscopic purposes, specialised methods of generating iminyl radicals were employed. For example, iminyls were obtained from organic nitriles by electron bombardment and subsequent protonation and/or by H-atom addition [16]. Thermal dissociations of thionocarbamates [17], H-atom abstractions from imines [18] and treatments of organic azides with t-BuO• radicals [19,20] were also put to use in obtaining iminyl EPR and other spectra. The range of accessible iminyl types has been considerably broadened as oxime derivatives 3–8 have come into use.

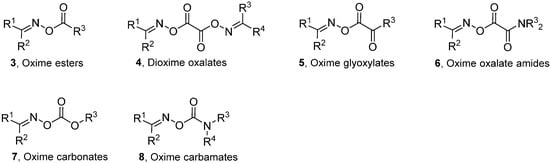

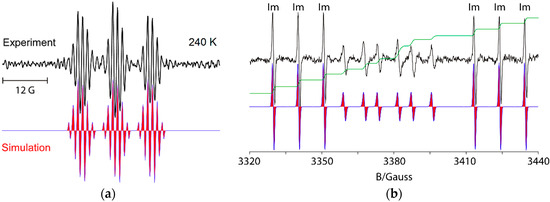

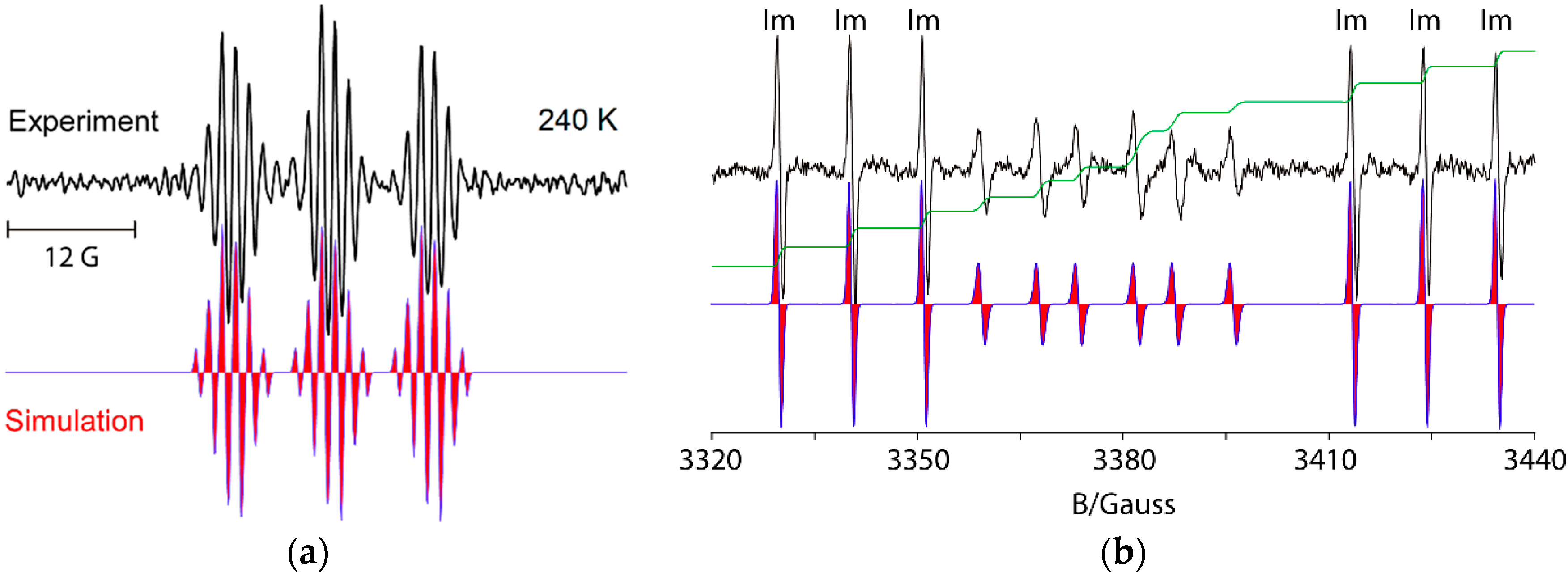

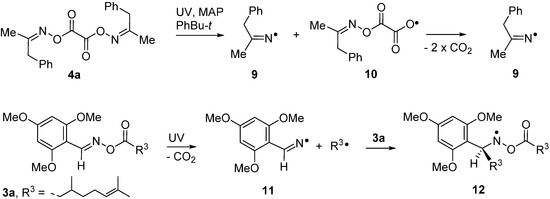

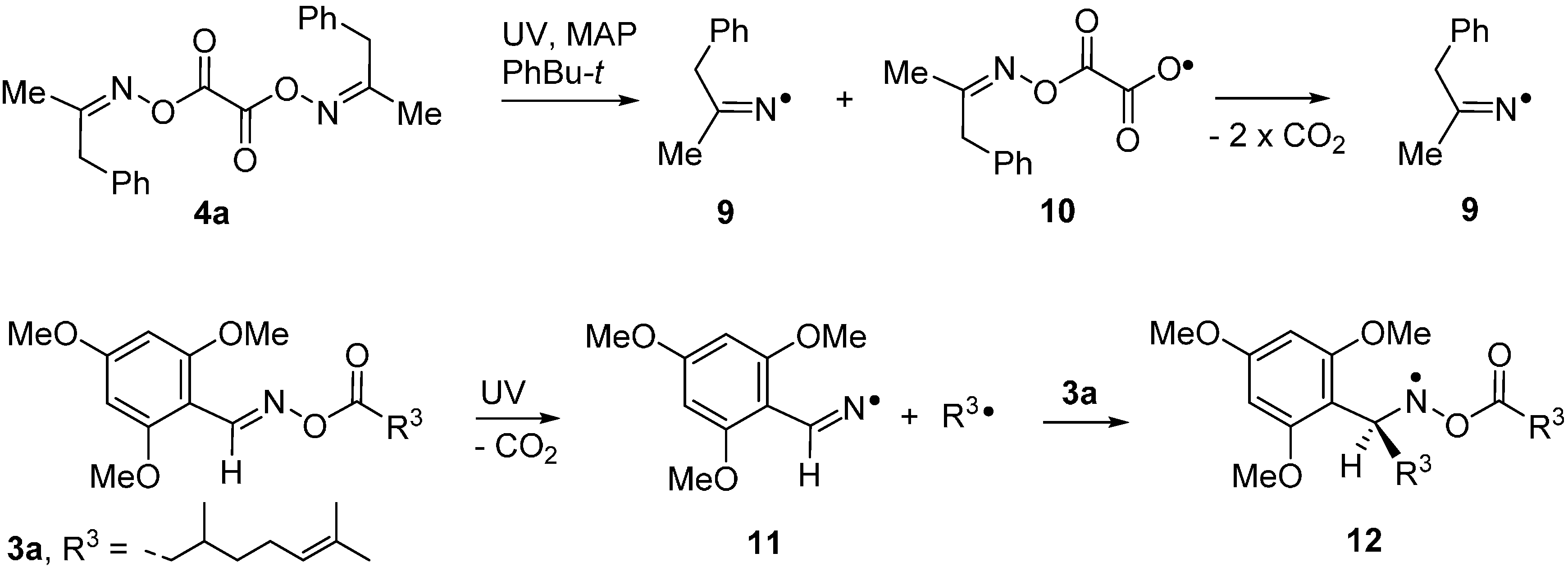

For example, UV irradiation of dioxime oxalate 4a in t-butylbenzene solvent with MAP as photosensitizer, at 240 K, in the resonant cavity of a 9 GHz EPR spectrometer enabled the spectrum shown in Figure 1a to be obtained. Absorption of radiation led to scission of one of the N–O bonds and production of iminyl radical 9 plus O-centred radical 10. The latter was probably extremely short-lived and dissociated with release of a second copy of 9 (Scheme 2). Thus, the EPR spectrum consisted of only iminyl 9 in the accessible temperature range. The 1:1:1 triplet hyperfine splitting (hfs) from the 14N-atom was slightly asymmetrical due to incomplete averaging of the radical tumbling at 240 K. Small hfs from the benzyl CH2 and the Me group were also resolved (Table 1).

Figure 1.

9 GHz isotropic EPR spectra of selected iminyl radicals in t-butylbenzene solution. Left top (a) Experimental spectrum of 1-phenylpropan-2-yliminyl radical 9, with simulation below (red), during UV photolysis of dioxime oxalate 4a; Right top (b) Experimental spectrum during UV photolysis of oxime ester 3a at 320 K showing iminyl radical 11 (marked Im) in black with simulation in red (below) and double integral in green. The spectrum of adduct oxyaminyl radical 12 appears in the central region.

Figure 1.

9 GHz isotropic EPR spectra of selected iminyl radicals in t-butylbenzene solution. Left top (a) Experimental spectrum of 1-phenylpropan-2-yliminyl radical 9, with simulation below (red), during UV photolysis of dioxime oxalate 4a; Right top (b) Experimental spectrum during UV photolysis of oxime ester 3a at 320 K showing iminyl radical 11 (marked Im) in black with simulation in red (below) and double integral in green. The spectrum of adduct oxyaminyl radical 12 appears in the central region.

Scheme 2.

Photolytic generation of iminyl radicals from carbonyl oximes.

Scheme 2.

Photolytic generation of iminyl radicals from carbonyl oximes.

The spectrum in Figure 1b illustrates the advantages of precursors prepared from aldoximes such as 3a. The released ald-iminyls have structures R1CH=N• with β-H-atoms. Because of the large hfs from its β-H-atom, the spectrum of the 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyliminyl radical 11 appears as sharp 1:1:1 triplets in either wing (Im) leaving an extensive central “window” in the field where spectra of other radicals can appear well resolved. Ald-iminyl radical spectra act as valuable references for determination of the g-factors of other species. However, more importantly, photo-dissociation of 3a, (and other carbonyl oximes) releases equimolar quantities of the iminyl and its partner radical. As Figure 1 shows, double integrations of such ald-iminyl spectra are usually easy and, hence, these iminyls also act as key references for the absolute and/or relative concentrations of other radicals generated. In the case of dissociation of oxime ester 3a, the O-centred partner radical rapidly lost CO2 with production of primary C-centred radical R3• (Scheme 1). At lower temperatures (~240 K), the spectrum of R3• was observed, whereas at higher temperatures R3• added to the precursor oxime ester and generated the N-centred radical 12. The spectrum of oxyaminyl 12 was well resolved in the central window (Figure 1b) [21,22].

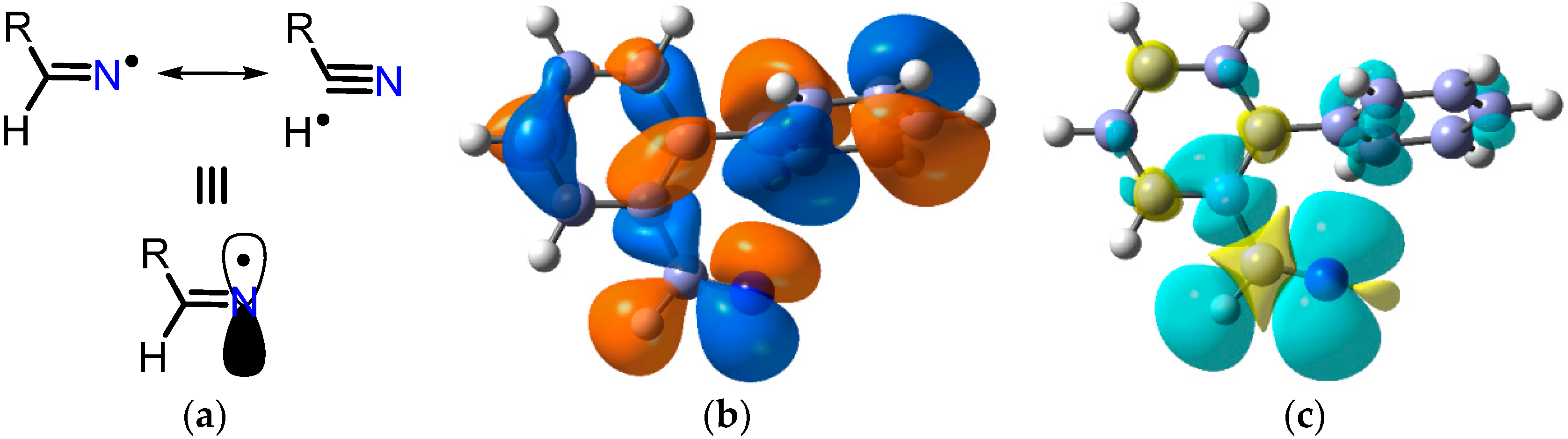

The EPR parameters of a representative set of iminyl radicals are collected in Table 1. They all have characteristic g-factors close to 2.0030 and isotropic a(14N) hfs of about 10 G. The magnitude of the latter is similar to that of π-type N-centred radicals indicating that the unpaired electron (upe) is mainly located in a nitrogen 2p orbital [18]. In addition, the large values obtained for a(Hβ) point to a substantial hyperconjugative interaction such that the semi-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) lies in the nodal plane of the C=N π-bond (Figure 2a).

Table 1.

EPR Characteristics of iminyl radicals in solution a.

| Radical | Solvent | T/K | g-Factor | a(14N) | a(Hβ) | a(Other) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2C=N• | c-C3H6 | 223 | 2.0028 | 9.7 | 85.2(2H) | - | [19] |

| MeHC=N• | H2O | 300 | 2.0028 | 10.2 | 82.0 | 2.5(3H) | [16] |

| EtHC=N• | c-C3H6 | 220 | 2.0028 | 9.6 | 79.5 | 2.8(2H), 0.5(3H) | [20] |

| PhHC=N• | CCl4 | 270 | 2.0031 | 10.0 | 80.1 | 0.4(2H), 0.3(1H) | [17] |

| ArHC=N• (11) | PhBu-t | 300 | 2.0034 | 10.7 | 84.0 | - | [21] |

| Me2C=N• | c-C3H6 | 223 | 2.0029 | 9.6 | - | 1.4(6H) | [19] |

| PhMeC=N | PhBu-t | 308 | 2.0030 | 10.0 | - | 0.8(3H) | [23] |

| BnMeC=N• (9) | PhBu-t | 240 | 2.0033 | 9.8 | - | 1.5(3H), 1.1(2H) | [tw] |

| Ph2C=N• | CCl4 | 308 | 2.0033 | 10.0 | - | 0.4(8H) | [24] |

a Isotropic g-factors; isotropic hfs in Gauss; tw = this work.

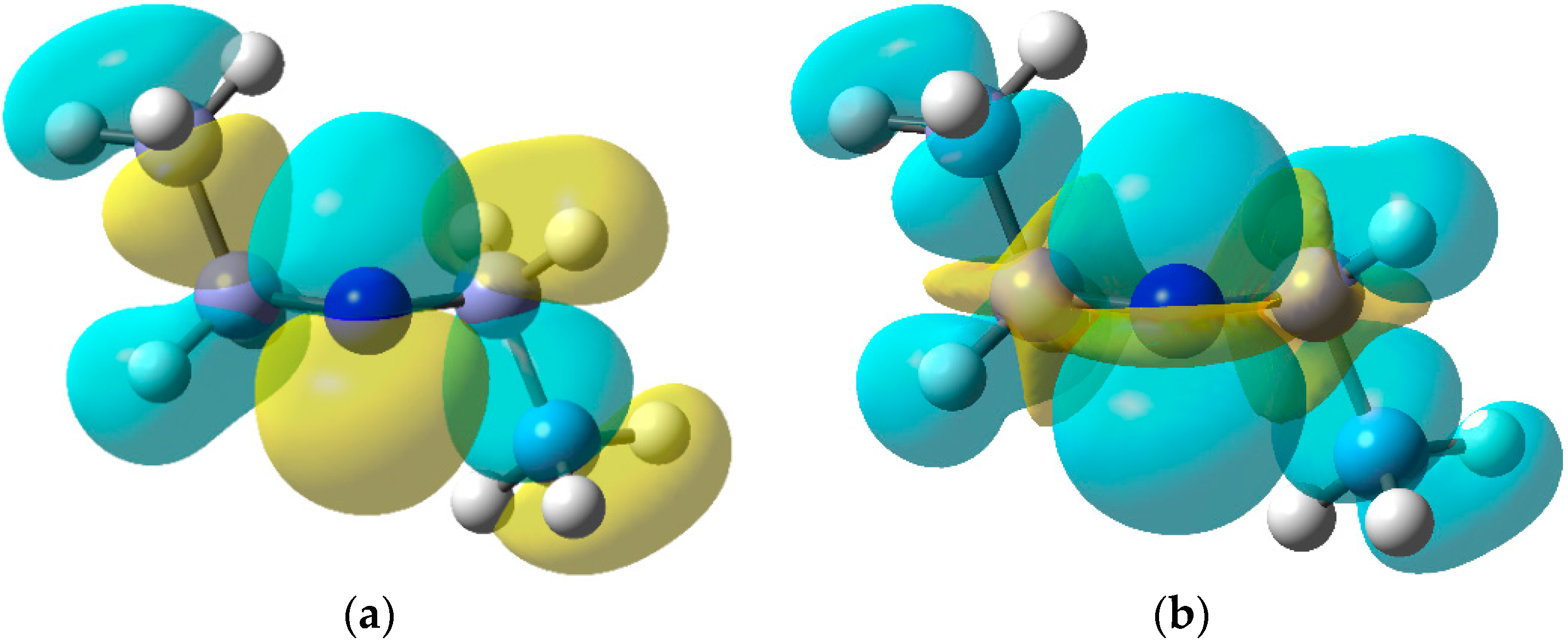

The SOMO and isotropic spin density distribution computed for the biphen-2-yliminyl radical at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level are illustrated in Figure 2b,c, respectively. These show rather clearly the orientation in the nodal plane of the C=N π-bond of lobes containing the upe and fully support the conclusions from the EPR data.

Figure 2.

Electronic configuration of alkyl- and aryl-iminyl radicals. (a) hyperconjugative interaction; (b) DFT computed alpha SOMO; (c) DFT computed spin density distribution.

Figure 2.

Electronic configuration of alkyl- and aryl-iminyl radicals. (a) hyperconjugative interaction; (b) DFT computed alpha SOMO; (c) DFT computed spin density distribution.

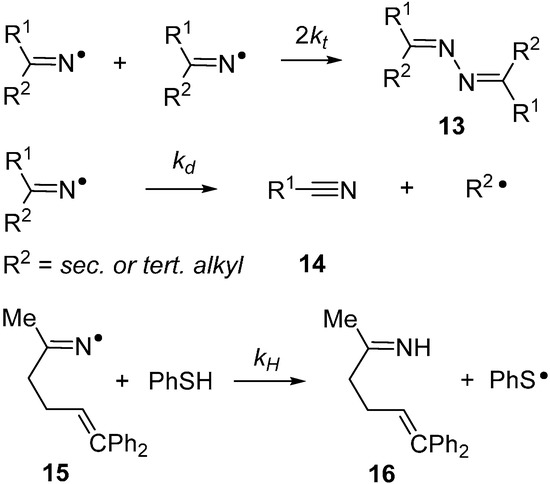

End product characterizations and EPR observations with iminyls [16,25] demonstrated that they terminate by bimolecular combination with production of bismethylenehydrazines 13 (Scheme 3) or by combination with alkyl radicals to yield imines. Ingold and co-workers established that these termination reactions are fast and diffusion controlled for small iminyls (2kt = 4 × 107, 2 × 108, and 4 × 109 M−1·s−1 at 238 K for R1 and R2 i-Pr, Ph, and CF3, respectively) [18].

Scheme 3.

Combination, dissociation and H-atom abstraction reactions of iminyl radicals.

Scheme 3.

Combination, dissociation and H-atom abstraction reactions of iminyl radicals.

As expected, sterically shielded iminyls like t-Bu2C=N• terminated much more slowly (2kt = 4 × 102 M−1·s−1 at 238 K). Iminyl radical termination reactions and rates are, therefore, quite similar to those of C-centred analogues.

Iminyls also undergo dissociation by β-scission with production of nitriles 14 and release of C-centred radicals (Scheme 3). When R1 and R2 are aryl or primary-alkyl groups, this dissociation is slow at room temperature and does not compete with, for example, ring closure. However, at higher temperatures, and for R1 or R2 = sec- or tert-alkyl, β-scission is rapid. For example, if R1 = R2 = t-Bu then kd = 42 s−1 at 300 K [18]. Occasionally, iminyl radical dissociations have been put to use in preparations of organic nitriles [14,26]. Iminyl radicals are also known to abstract H-atoms from suitable substrates producing imines (16) and C-centred radicals. Kinetic studies are scarce but the diphenylhex-5-en-2-iminyl radical 15 abstracts H-atoms from thiophenol with a rate constant of 6 × 106 M−1·s−1 at 298 K [27]. Comparing with C-centred analogues suggests that iminyls abstract H-atoms 10–20 times more slowly.

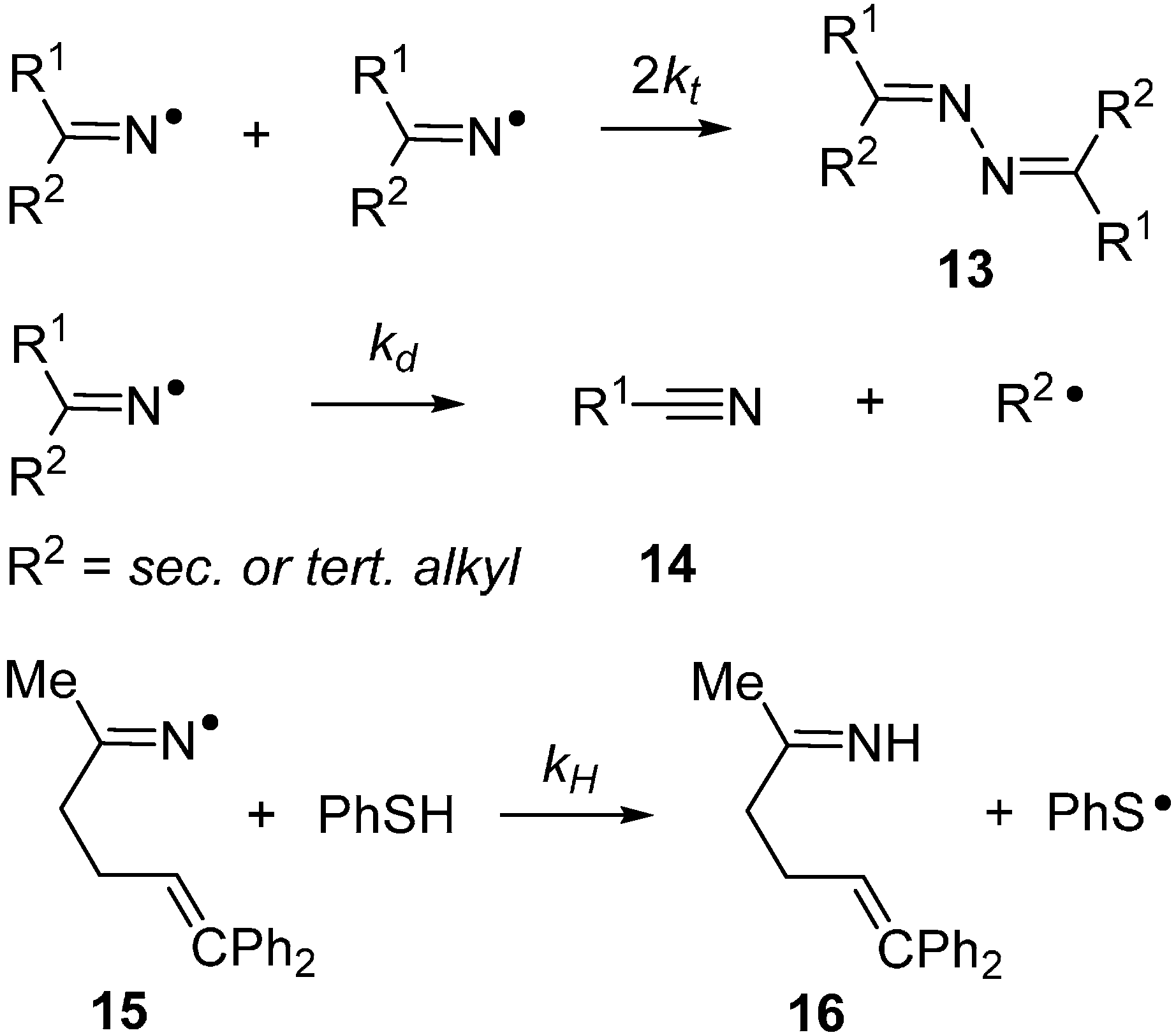

Iminyl radicals with alkenyl side chains ring close selectively in the 5-exo mode with formation of pyrrolomethyl type radicals. This cyclisation forms the basis of several preparative procedures of pyrrole and dihydropyrrole containing heterocycles [26,28,29,30]. Some rate data has been determined by LFP [27] and steady state kinetic EPR methods [31], and key data is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rate parameters for cyclisations of unsaturated iminyl radicals in solution a.

| |||

| Radical; R1, R2, R3 | mode | kc/s−1 (300 K) | Ec/kcal·mol−1 |

| 17 b | 5-exo | 10 × 103 | 9.2 |

| 18; H, H, H | 5-exo | 8.8 × 103 | 8.3 |

| 18; H, Me, H | 5-exo | 0.15 × 103 | 10.7 |

| 18; H, H, Et | 5-exo | 60 × 103 | 7.2 |

| 18; Me, H, H | 5-exo | 0.31 × 103 | 10.3 |

| 19 | 5-exo | 22 × 103 | 7.8 |

| 20 c | 6-endo | <5 × 103 | >9 |

a Data from reference [31] except as indicated otherwise; all in hydrocarbon solution. Arrhenius A-factors assumed to be log(Ac/s−1) = 10.0; b Data from references [31,32]; c Data from reference [33].

The rate constants for 5-exo-cyclisations of the iminyls 17 and 18 (R2 = R2 = R3 = H) are smaller than that of the archetype C-centred hex-5-enyl radical by a factor of about 25. A Me substituent at the attacked end of the double bond reduced kc but an Et substituent at the terminus of the C=C double bond increased kc (Table 2). These trends are the same as observed with C-centred radical cyclisations. Surprisingly, the bismethyl substituted iminyl 18 (R1 = Me, R2 = R3 = H) displayed an inverse gem-dimethyl effect (Table 2). However kc for iminyl 19, lacking the Ph substituent, but with a single Me in its pentenyl chain, showed the expected increase in kc. Thus, the inverse gem-dimethyl effect is specially related to the presence of the Ph substituent on the imine centre. DFT computations implied it was due to steric interaction between this Ph and the bis-Me groups in the alkenyl chain [31]. DFT computations of ring closure reactions of C-, N- and O-centred radicals with the high-quality quantum composite method Gaussian-4 [34] suggested that the stiffness and lack of flexibility associated with the C=N bond was responsible for the comparatively slow ring closure of iminyl radicals, rather than any effect from their higher electronegativity. In general, iminyls with aromatic acceptors such as 20 cyclised in 6-endo mode with production of 6-member rings (see, however, Section 2.7). Kinetic data is sparse but implies that the rate constants for iminyl ring closures onto aromatics are also about an order of magnitude less than those of C-centred analogues [33].

2.3. Radical Based Transformations of Oxime Esters and Dioxime Oxalates

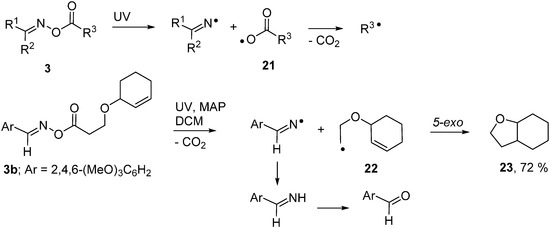

Oxime esters were the first oxime derivatives to be used for radical generation and they remain the most popular. They have been put to use in two ways; either as sources of C-centred radicals or for generating iminyl radicals. On homolysis of their weak N–O bonds, an iminyl radical is accompanied by an acyloxyl type radical 21 (Scheme 4). Most acyloxyls decarboxylate and release C-centred radicals very rapidly [35] making these precursors very effective sources of the latter. UV photolyses of appropriate 3, with and without sensitisers, have proved effective for generating a broad range of primary, secondary and tertiary C-centred radicals as well as allylic types and even σ-radicals such as cyclopropyl and trifluoromethyl [21,22].

Scheme 4.

Photo-induced oxime ester transformations [22].

Scheme 4.

Photo-induced oxime ester transformations [22].

The good quality EPR spectra obtainable enabled the configurations and conformations of these radical types to be elucidated. The reactions they underwent with their parent oxime esters, or with other partners or co-reactants (see Figure 1b for an example), were also monitored. A recent time-resolved EPR spectroscopic investigation of the photo-cleavage of several oxime esters enabled effective spin-spin relaxation times T2* to be determined [36]. From the T2* dependences on monomer concentrations, rate data was deduced for addition reactions with acrylate monomers.

Oxime esters 3 proved to be clean and convenient sources of C-centred radicals that could be used in syntheses of various alicyclic and heterocyclic compounds [22]. Scheme 4 depicts one example in which photolysis of precursor 3a released cyclohexenyloxyethyl radical 22 which underwent 5-exo-ring closure and yielded octahydrobenzofuran 23 after H-atom transfer. The accompanying iminyl radical simply abstracted H-atoms with production of an imine that was hydrolysed to the easily separable aldehyde during work-up.

O-Acetyl oxime esters R1R2C=NOC(O)Me were established as highly effective sources of iminyl radicals for synthetic purposes because the partner MeC(O)O• radicals were simply converted to volatile CO2 and CH4 [37,38,39]. Because symmetrical dioxime oxalates also cleanly yield only one iminyl radical, they too proved to be very successful in UV promoted preparative procedures [40,41]. Convenient photochemical routes, starting from these precursors, were described for pyrroles, dihydropyrroles, quinolines, phenanthridines and other aza-arenes with a range of functionality.

2.4. Oxime Esters and Photoredox Catalysis

Recently, in the interests of environmental protection and energy efficiency, research has expanded dramatically into finding procedures that require only visible light, plus catalytic quantities of some special promoter. For generating radicals, photoredox catalysts (PCs) of several types that require only visible light (sometimes UVA) have been developed. Heterogeneous PCs are mainly inorganic semiconductors, particularly titania (TiO2), which has found numerous applications in conjunction with allylic alkenes, alkyl amines, carboxylic acids and other compounds [42,43,44,45]. Development of the alternative homogeneous type PCs has flourished exceptionally well. The most widely used members of this class are complexes of Ru or Ir, particularly Ru(bpy)32+ and fac-[Ir(ppy)3], that usually operate in conjunction with bromocarbonyl compounds and other organic halides [46,47,48,49,50]. Most PCs adsorb a photon from the incident light and are thereby raised to a long lived triplet state PC* that can act both as a reductant and/or an oxidant. In the presence of an acceptor molecule A, with a suitable redox potential, electron transfer from the PC* generates the radical anion A−•. These radical anions then convert to neutral radicals A• by loss of an anion such as halide X− or carboxylate. Alternatively, PC* may accept an electron from a suitable donor molecule D, thus creating the radical cation D+• that then converts to a neutral radical by loss of a cation, usually H+.

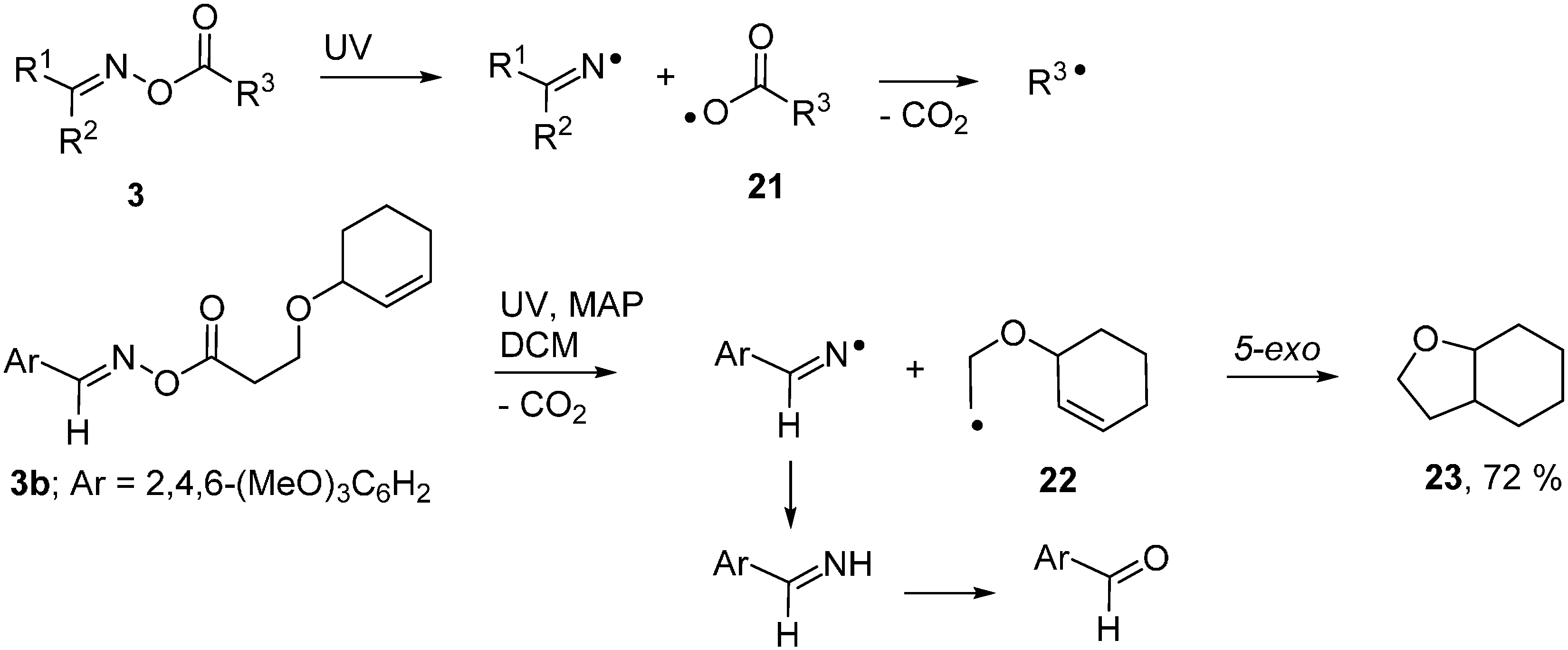

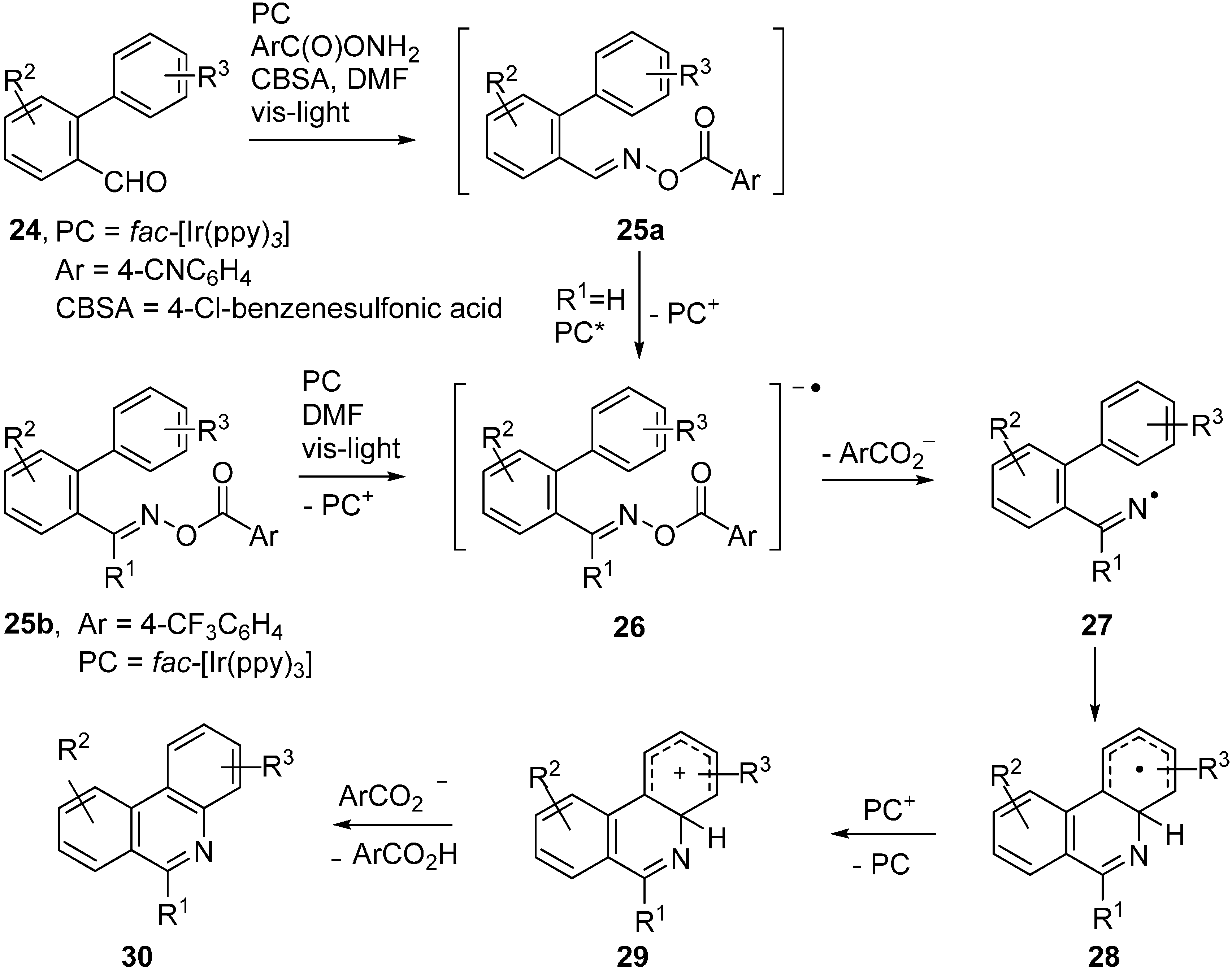

Expressly designed oxime ester types were trialled recently to function as acceptors with fac-Ir(ppy)3 as PC [51,52]. Oxime esters 25a,b, containing O-benzoyl moieties substituted with strong electron withdrawing groups such as 4-CN and 4-CF3, were shown to be effective in this role (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Reactions of designer oxime esters catalysed by fac-[Ir(ppy)3] [51,52].

Scheme 5.

Reactions of designer oxime esters catalysed by fac-[Ir(ppy)3] [51,52].

Electrons were transferred to these oxime esters from the [fac-Ir(ppy)3]* triplet states so generating transient radical anions 26. Loss of the substituted benzoate anions from 26 generated iminyl radicals 27. Cyclisation onto the adjacent aryl rings afforded cyclohexadienyl type radicals 28b. Oxidation to the corresponding cyclohexadienyl type cations 29 took place via SET to the previously produced PC+ ions. Proton loss then led to the product phenanthridines 30. A wide range of the latter was obtainable in this way and, for 24 with Ar = 4-CNC6H4, the procedure could be carried out in one pot from the aldehydes without isolation of 25a (Scheme 5). Analogous PC mediated routes to quinoline and pyridine derivatives were also demonstrated.

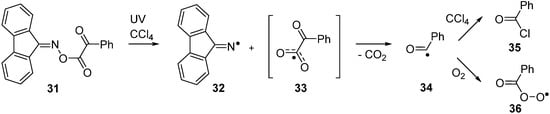

2.5. Photodissociation of Ketoxime Glyoxalates

Bucher and co-workers investigated the LFP induced dissociation of 9-fluorenone oxime phenylglyoxylate 31 in CCl4 solution by a variety of spectroscopic methods [53]. They used time resolved FTIR and time-resolved EPR to identify intermediate radicals. By these means, dissociation was shown to produce the expected iminyl radical 32 together with very short-lived benzoylcarbonyloxyl radical 33. Rapid loss of CO2 from 33 yielded benzoyl radicals 34 and their subsequent chemistry dominated the system (Scheme 6).

Benzoyl radicals abstracted chlorine atoms from solvent to yield benzoyl chloride 35b (or a bromine atom from CCl3Br to yield benzoyl bromide). In the presence of oxygen, coupling occurred with generation of peroxyls 36. Preparative sequences based around oxime glyoxalates have not so far been established, but it seems clear they could be exploited as new clean sources of acyl or aroyl radicals as well as for iminyl radicals.

Scheme 6.

Photodissociation and subsequent reactions of an oxime glyoxalate [53].

Scheme 6.

Photodissociation and subsequent reactions of an oxime glyoxalate [53].

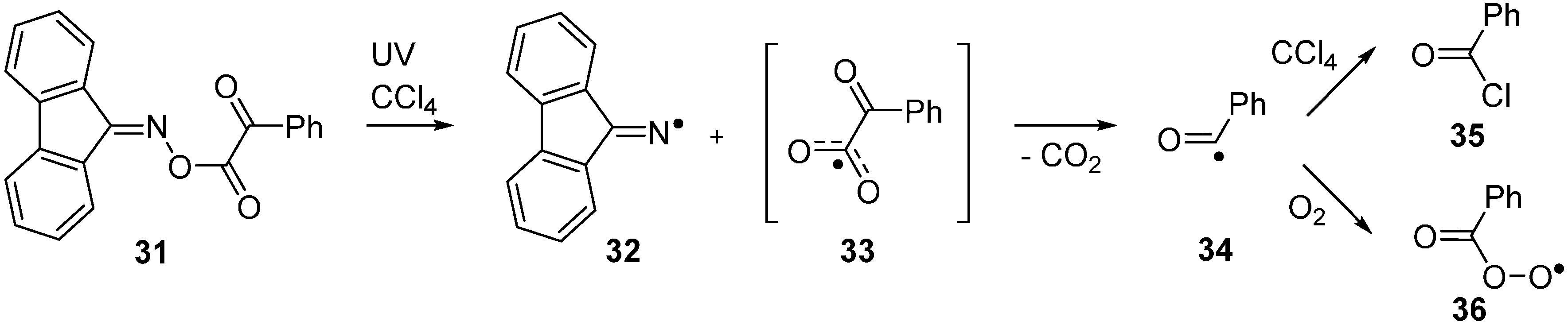

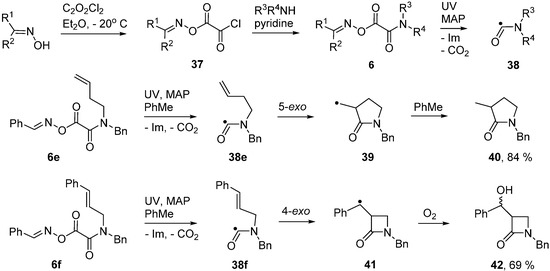

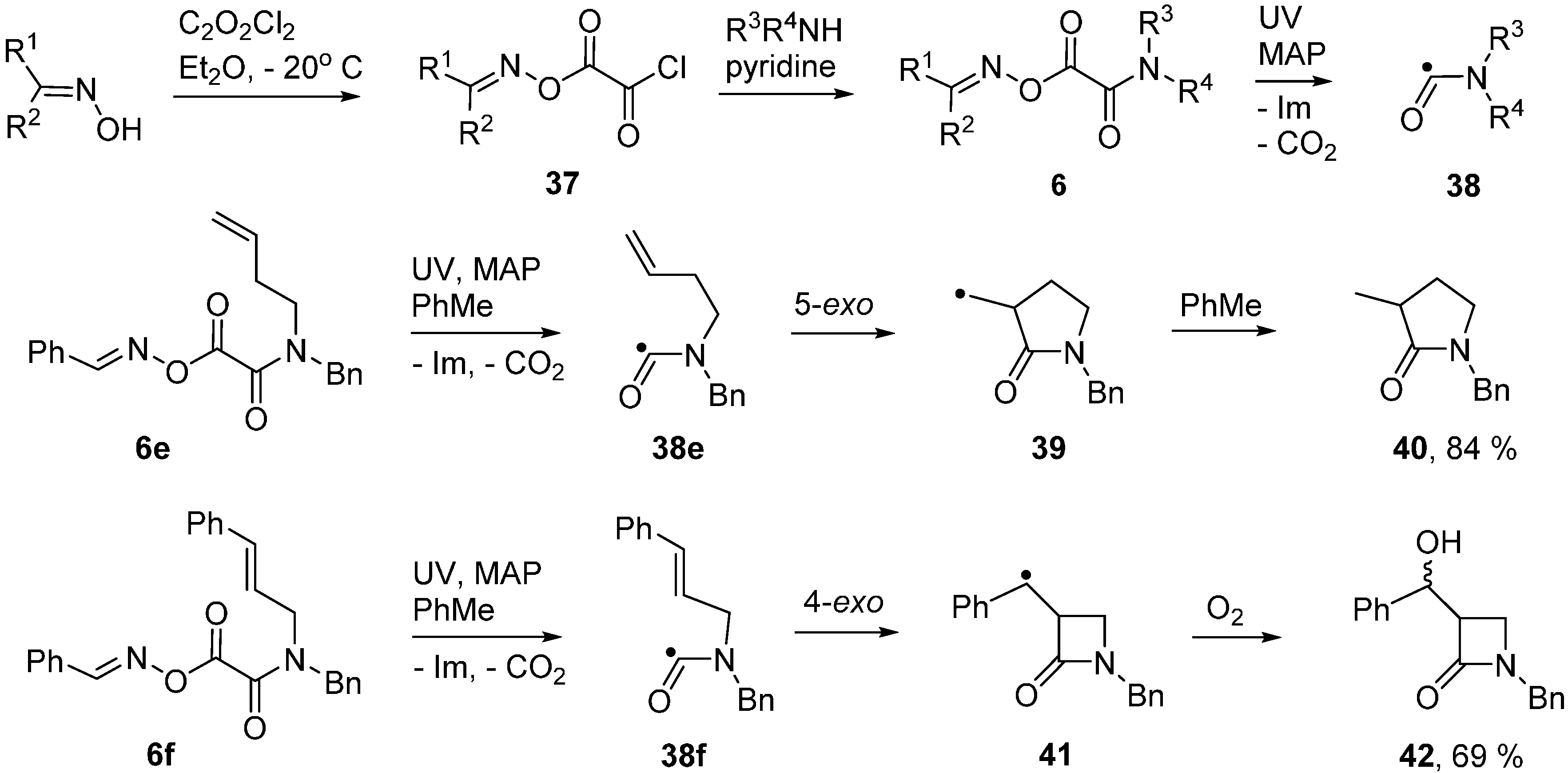

2.6. Carbamoyl Radicals from Oxime Oxalate Amides: Ring Closures to β- and γ-Lactams

Oxime oxalate amides 6 may be obtained in good yields from O-chlorooxalyl oximes 37 and amines (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Oxime oxalate amides and ring closures of carbamoyl radicals [54,55].

Scheme 7.

Oxime oxalate amides and ring closures of carbamoyl radicals [54,55].

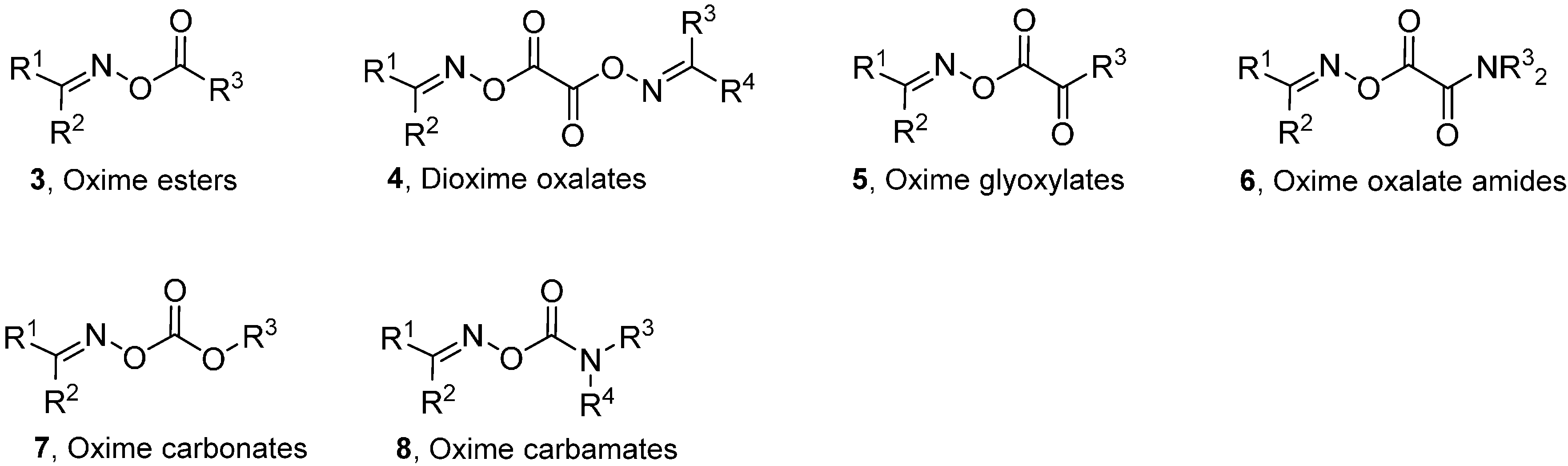

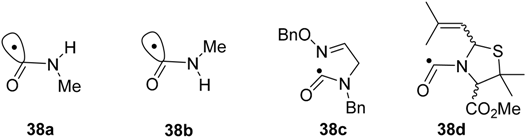

UV photolyses of solutions in PhBu-t delivered exclusive scissions of their weak N–O bonds. A number of iminyl and, after CO2 extrusion, carbamoyl (aminoacyl) radicals 38, were observed by EPR spectroscopy [54,55]. Some representative EPR data for carbamoyls, including literature values, is collected in Table 3. The N–C bonds of amides have partial double bond character and, hence, high internal rotation barriers (20 ± 5 kcal·mol−1). High barriers are therefore expected in carbamoyl radicals. Experimental data is lacking, but a DFT computation [B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)] on radicals 38a and 38b provided an internal rotation barrier (about the N–C(O) bond) of 19.8 kcal·mol−1. It follows that carbamoyls will be capable of existing as E and Z isomers. Not surprisingly, only one isomer, presumably the E-isomer, was detected in each case. Carbamoyls such as 38b, with cis-structures in which the NH hydrogen is trans to the orbital containing the upe, have been generated by H-abstraction from N-alkyl formamides [56]. The hfs from the NH hydrogens of these conformers are of much larger magnitude (see Table 3).

Table 3.

EPR parameters of carbamoyl (aminoacyl) radicals in solution.

| ||||||

| Radical | Solvent | T/K | g-Factor | a(N) | a(Other) | Reference |

| Me(H)NC•(O) (38a, trans) | PhMe | 208 | 2.0015 | 24.0 | 0.9(NH), 0.9(3H) | [56] |

| Me(H)NC•(O) (38b, cis) | PhMe | 208 | 2.0015 | 21.2 | 25.1(NH) | [56] |

| but-4-enyl(Bn)NC•(O) (38e) | PhBu-t | 230 | 2.0017 | 21.7 | 0.8(1H) | [55] |

| but-2-enyl(Bn)NC•(O) | DTBP | 360 | 2.0019 | 22.1 | [57] | |

| n-Bu(Bn)NC•(O) | DTBP | 360 | 2.0019 | 21.9 | 0.9(4H) | [57] |

| 38c | PhBu-t | 220 | 2.0018 | 23.3 | [58] | |

| 38d | PhBu-t | 220 | 2.0018 | 21.0 | 1.6(1H) | [55] |

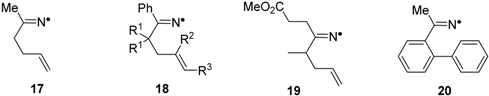

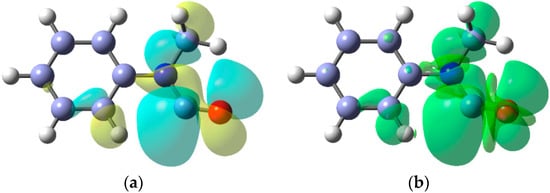

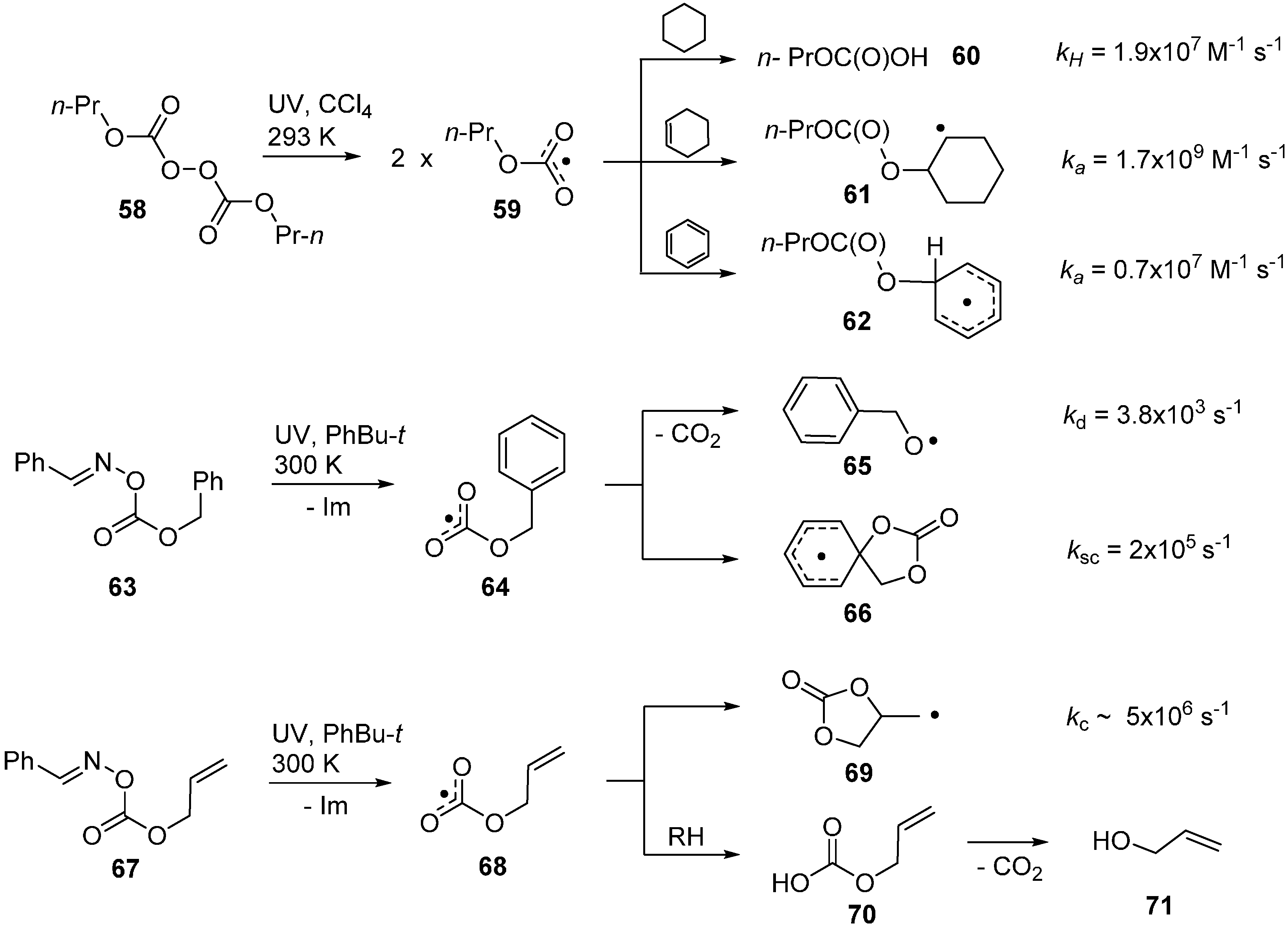

A noteworthy feature of carbamoyl radicals’ EPR spectra is that their g-factors are comparatively small and actually less than that of the free electron (g = 2.0023). Only a few other radicals share this characteristic so the g-factor is an aid in identification [59]. The comparatively large a(N) hfs indicate carbamoyls have σ-electronic structures and this was supported by DFT computations. Figure 3 shows the σ-lobe of the SOMO of the Ph(Me)NC•(O) radical, computed at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level, in the nodal plane of the CO π-system. The spin density distribution (Figure 3b) mirrors this feature.

Figure 3.

(a) DFT computed alpha SOMO of Ph(Me)NC•(O) radical; (b) DFT computed spin density distribution of Ph(Me)NC•(O) radical.

Figure 3.

(a) DFT computed alpha SOMO of Ph(Me)NC•(O) radical; (b) DFT computed spin density distribution of Ph(Me)NC•(O) radical.

Carbamoyl radicals containing suitably situated acceptor groups readily underwent ring closure. For example, the N-but-4-enyl oxime oxalate amide 6e furnished the carbamoyl radical 38e and this cyclised efficiently in the normal 5-exo-mode to afford pyrrolidin-2-one derivative 40 in good yield [55] (Scheme 7). Interestingly, carbamoyl radicals functionalised with allylic side chains also underwent ring closure in the rare 4-exo-mode with eventual production of 4-member ring azetidin-2-ones. For example, precursor 6f produced carbamoyl 38f that, after 4-exo-cyclisation to azetidinylalkyl radical 41, yielded β-lactam 42.

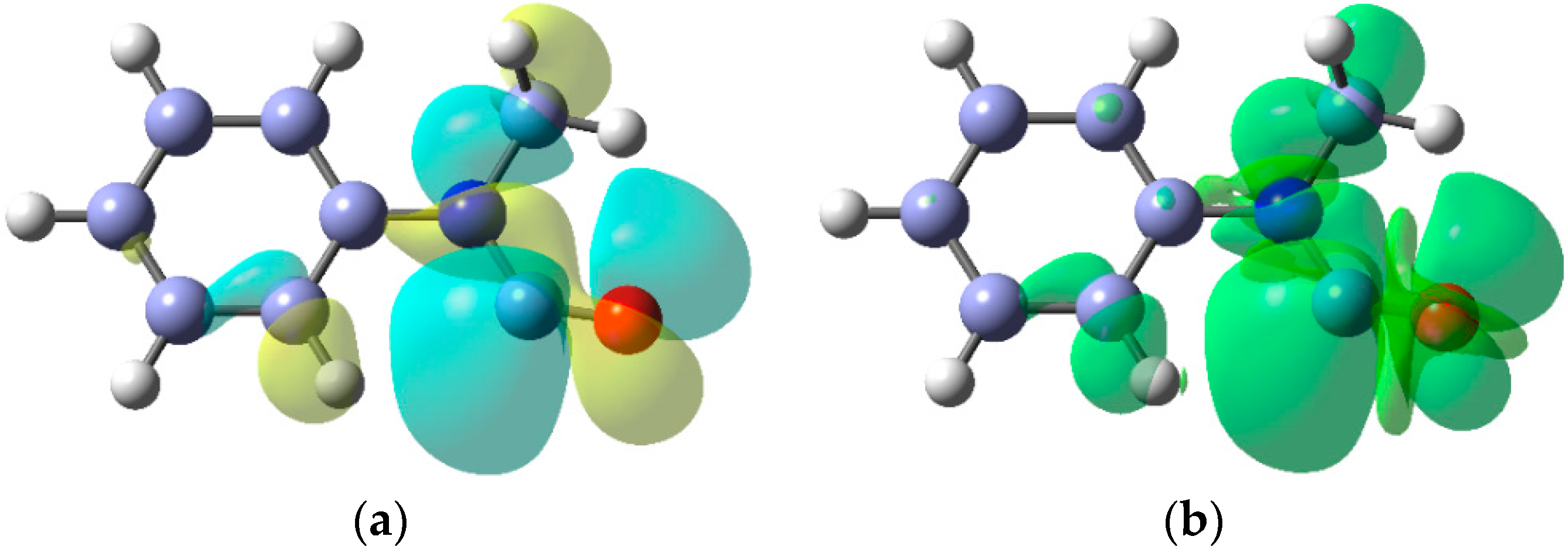

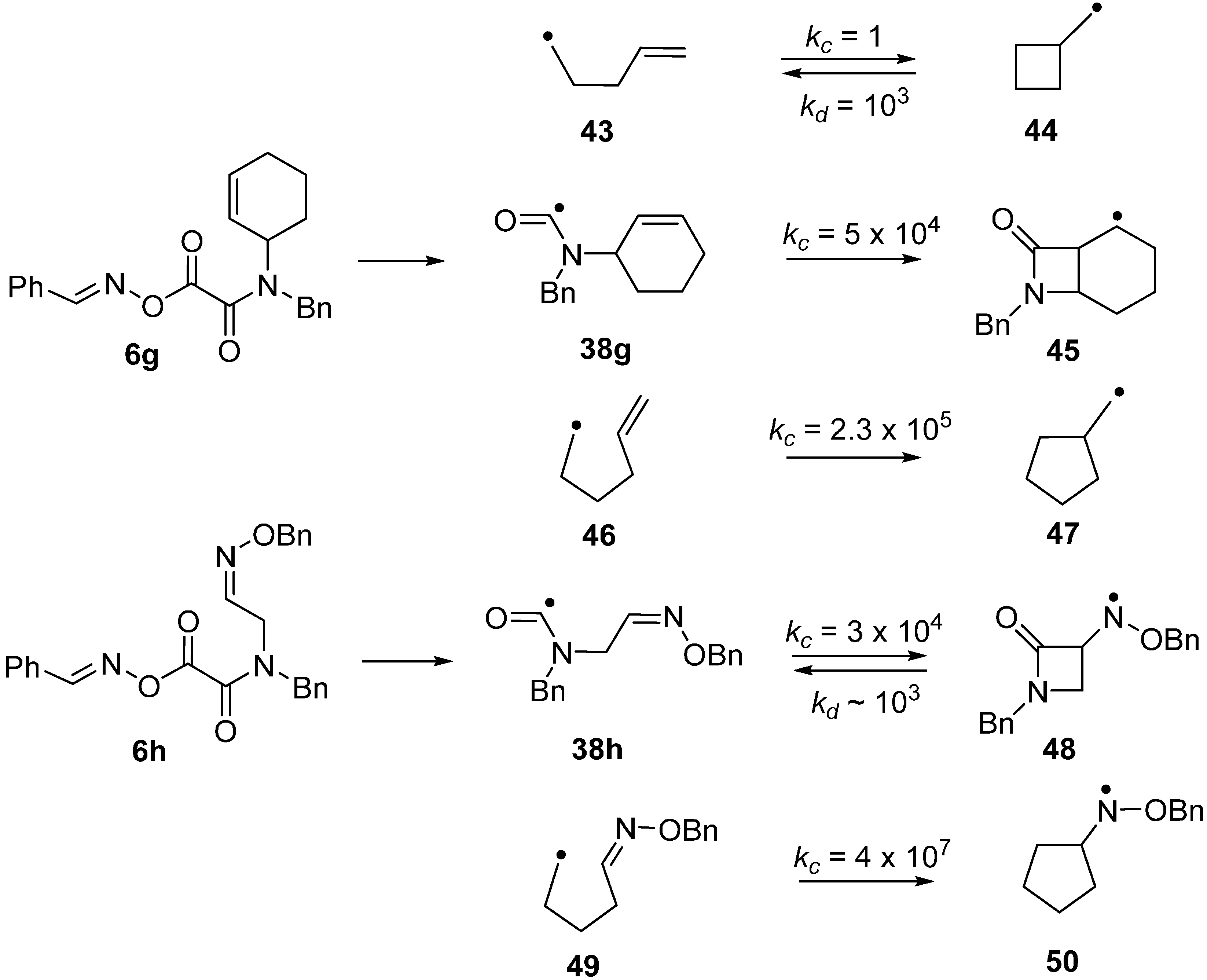

The azetidinone ring system occurs as a key feature in the β-lactam family of antibiotics so preparative methods are of special interest. Radical closures to 4-member rings are normally slow in comparison to the reverse ring opening which is fast because of the strain in the 4-member rings [60,61,62]. Note the rate constants (kc) for 4-exo-closure of the but-3-enyl 43 and ring opening (kd) of the cyclobutylmethyl radical 44 in Scheme 8. The 4-member azetidinone ring system has proved to be exceptional because β-lactams have been prepared by cyclisations of carbamoyl radicals [63,64,65], of amidoalkyl radicals [66,67,68,69,70] and of amidyl radicals [71]. This topic has been reviewed in the context of homolytic ring closures in general [72]. EPR spectra obtained from UV irradiations of oxime oxalate amides made possible kinetic studies of several carbamoyl radical cyclisations [58,73]. Carbamoyl 38g was obtained from photodissociation of precursor 6g and the rate constant for its 4-exo-cyclisation onto a C=C bond to yield bicyclic radical 45 was determined to be four orders of magnitude greater than that of archetype pent-4-enyl radical 43 (Scheme 8). The rate constant for 4-exo-cyclisation of carbamoyl 38h on to a C=N bond to produce aminyl radical 48 was of the same order of magnitude. Note that the rate constant for opening of the azetidinone ring of 48 was not much different from that of model 44 but was sufficiently smaller than kc (for 38b) so that ring closed products could be isolated. As expected, all the 4-exo rate constants were smaller than the archetype kc for 5-exo cyclisation of hex-5-enyl 46 [74,75] and analogue 49 [76] (Scheme 8). It is worth mentioning that 4-exo-ring closures of cyclic carbamoyl radicals containing thiazolidine rings 38d, to directly give bicyclic penicillanic structures, were not achieved [73].

Scheme 8.

Kinetic data for ring closures of carbamoyl and model radicals at 300 K in solution. Rate constants k/s−1 [54,73,74,75,76].

Scheme 8.

Kinetic data for ring closures of carbamoyl and model radicals at 300 K in solution. Rate constants k/s−1 [54,73,74,75,76].

2.7. Dissociation of Oxime Carbonates and Generation of Alkoxycarbonyloxyl Radicals

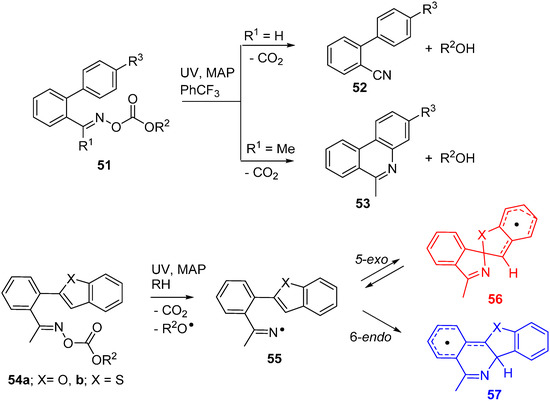

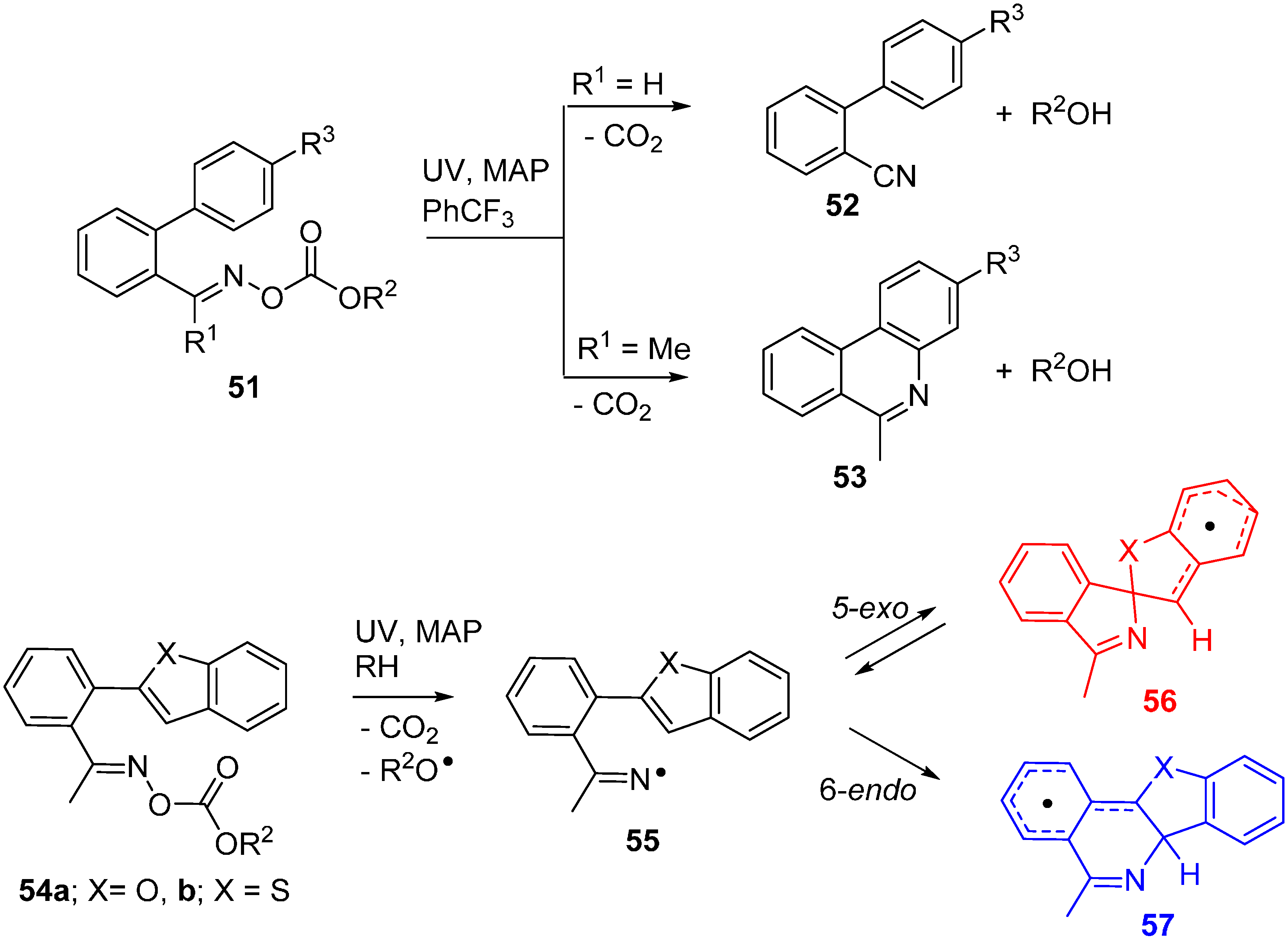

Oxime carbonates 51, like most of the fore-going oxime esters, have a bi-modal character and can operate either as sources of iminyl radicals or for production of the little known alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals, depending on the pattern of functionality [77]. For generation of iminyls, oxime carbonates with O-ethoxycarbonyl 51 (R2 = Et) or O-phenoxycarbonyl 51 (R2 = Ph) substitution were easily prepared by condensation of oximes with the corresponding chloroformates. Photolyses of the aldoxime derived precursors 51 (R1 = H) in benzotrichloride solvent afforded nitrile products 52. However, good yields of phenanthridines 53 with a range of functionality were obtained from 51 (R1 = Me) (Scheme 9). The by-products, ethanol or phenol (R2OH), were easily separated [23,78].

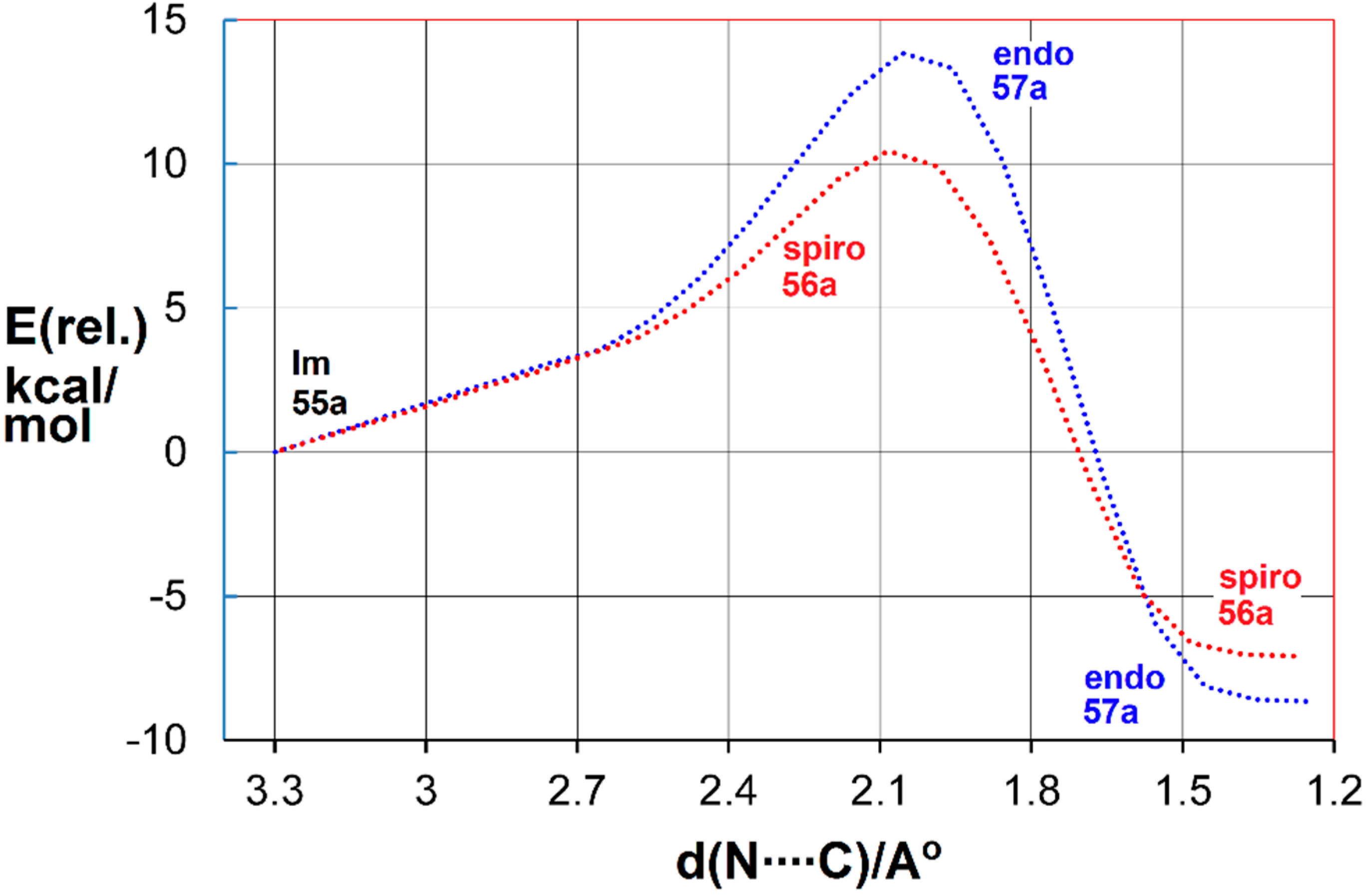

An intriguing dichotomy of behaviour was observed during transformations of oxime carbonates functionalised with benzofuran 54a and benzothiophene 54b groups. In biphen-2-yliminyl radicals (e.g., 20), the SOMO on the N-atom is well placed for orbital overlap at either the ipso-C-atom (5-exo-ring closure) or the ortho-C-atom (6-endo-ring closure); see Figure 2b,c (Section 2.2). In analogous fashion, iminyls 55a and b were capable of undergoing either 5-exo-ring closure to spiro-radical 56a,b or 6-endo-ring closure to 57a,b. In preparative photolyses with 54a and 54b at ambient temperature (~330 K) exclusively, the benzofuro[3,2-c]isoquinoline and benzo[4,5]thieno[3,2-c]isoquinoline products derived from the endo-radicals 57a and 57b were isolated in good yields [78]. Curiously, EPR spectra taken during photolyses of 54a and 54b in solution at 230 K showed solely the spiro-radicals 56a and 56b [33]. The structures and energies of the iminyl and cyclised radicals were computed by DFT at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level of theory with the Gaussian 09 package [79].

Scheme 9.

Reactions of iminyl radicals derived from oxime carbonates [33,78].

Scheme 9.

Reactions of iminyl radicals derived from oxime carbonates [33,78].

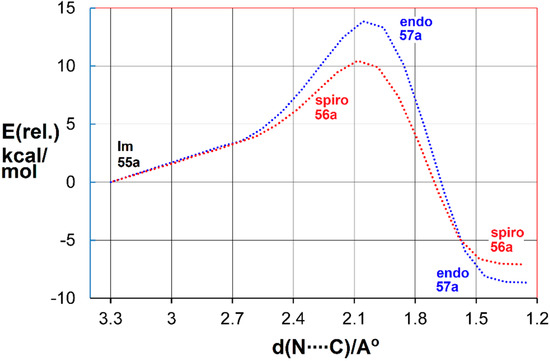

The transition states for spiro and endo ring closure were also located. The intrinsic reaction coordinate scans are illustrated in Figure 4 for the benzofuro system 55a.

Figure 4.

DFT computed reaction coordinates for spiro (red) and endo (blue) ring closure of benzofuro-iminyl radical 55a.

Figure 4.

DFT computed reaction coordinates for spiro (red) and endo (blue) ring closure of benzofuro-iminyl radical 55a.

The DFT computations showed spiro ring closure to be exoenthalpic (∆H298 = −6.9 kcal·mol−1) but the endo mode was thermodynamically more favourable (∆H298 = −8.1 kcal·mol−1). However, the computed enthalpy of activation for spiro-closure (∆E‡298 = 9.3 kcal·mol−1) was significantly lower than that for endo-closure (∆E‡298 = 13.1 kcal·mol−1) (see Figure 4). Similar trends were computed for the benzothieno system from radical 55b. These DFT energies supported the conclusion that, at the low temperature of the EPR experiments, kinetic control led to spiro radicals 56a,b. However, at the temperature of the preparative experiments (~100 K higher), the spiro-cyclisations were reversible but the endo were not. Consequently, thermodynamic control steered the processes towards accrual of the endo products. The alternative possibility that the spiro-radicals 56a,b rearranged to the endo radicals 57a,b by 1,2-shifts via tetracyclic structures could be discounted because DFT computations indicated much higher energy requirements.

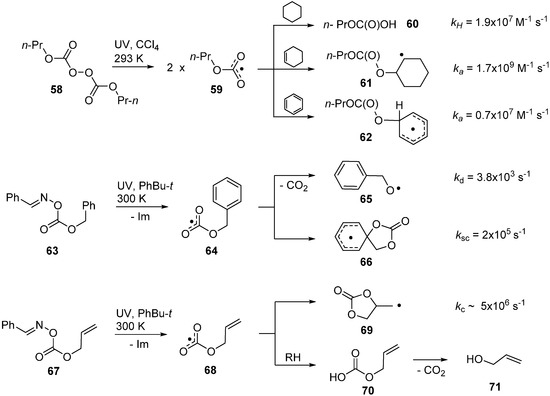

In the past, a few alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals [ROC(O)O•] had been generated from hazardous dialkyl peroxydicarbonate precursors (58) and studied by EPR spectroscopy [80] and LFP [81]. By means of suitably functionalised oxime carbonates, a much wider range of these radicals became accessible and their chemistry could be explored in greater detail.

Remarkably, alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals dissociate to release CO2 much more slowly than acyloxyl radicals (RCO2•). Thus, they have sufficient lifetimes to participate in a range of abstraction, addition and cyclisation processes. They are not directly detectable by EPR spectroscopy [80] due to fast relaxation times but their broad absorptions centred at around 640 nm in the UV-visible spectrum have been observed in the LFP studies [81]. They are very reactive and, for example, propyloxycarbonyloxyls 59 abstract H-atoms from secondary CH2 sites to produce esters of carbonic acid 60 with a rate constant of 1.9 × 107 M−1·s−1. They add to unactivated alkenes nearly a factor of 100 faster and also add to aromatics to produce cyclohexadienyl type radicals 62 with ease (see Scheme 10). In accord with this, the methoxycarbonyloxyl radical MeOC(O)O• was also observed to add to the alkenic sites of lipid components more rapidly than it abstracted allylic type H-atoms [82]. Furthermore, EPR spectroscopic data showed it dissociated to CO2 and MeO• radicals with a rate constant of about 2 × 103 s−1 at 300 K. Oxime carbonate 63 released benzyloxycarbonyloxyl radical 64 and surprisingly this (and derivatives) underwent exclusively spiro-cyclisation to produce spiro-cyclohexadienyl radical 66 [23,83]. From steady state kinetic EPR concentration measurements, the rate constant for CO2 loss from 64 was determined to be 3.4 × 103 s−1 at 300 K. The similarity in the kd values for MeOC(O)O• and BnOC(O)O• verified that alkoxycarbonyloxyls lose CO2 about seven orders of magnitude more slowly than acyloxyl radicals.

The rate constant for spiro-cyclisation was measured to be 2 × 105 s−1 and this is about an order of magnitude greater than for spiro-cyclisation of C-centred analogues [84,85,86]. Similarly, oxime carbonates with allylic side-chains, e.g., 67 released the corresponding allyloxycarbonyloxyl radicals 68 on photolysis. The latter ring closed in the 5-exo-mode to produce 1,3-dioxolan-2-on-4-ylmethyl radicals 69 very rapidly. The cyclisation rate constant (kc = 5 × 106 s−1 at 300 K) was obtained from kinetic EPR measurements. Scheme 10 illustrates that the cyclisation rates of alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals onto aromatic and alkenic acceptors are significantly faster than analogous rates of C-centred radicals. In this respect, they resemble alkoxyl radicals, such as pent-4-enyloxyl, that are also known to ring close much more rapidly than C-centred analogues [87,88]. Factors influencing the rapidity of 5-exo-cyclisations of C-, N- and O-centred radicals have been reviewed [34].

Products containing the 1,3-dioxolan-2-one unit (cyclic carbonates) were isolated from cyclisations of species such as 69; though in meagre yields. H-atom abstractions from solvents or substrates by alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals were also rapid so that alkylcarbonate esters such as 70 formed very easily. These were mono-esters of carbonic acid and as such were known to be unstable and extrude CO2 [89,90]. The resulting alcohols e.g., 71 were usually the major products isolated from alkoxycarbonyloxyl reactions. A synthetic protocol to trap and isolate products containing the cyclic carbonate structural unit has yet to be devised.

Scheme 10.

Reaction channels and rate constants for alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals [23,81,83].

Scheme 10.

Reaction channels and rate constants for alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals [23,81,83].

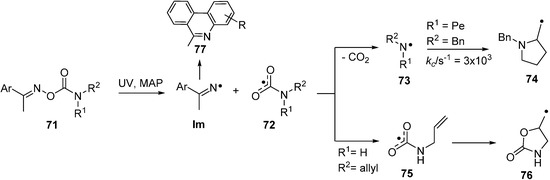

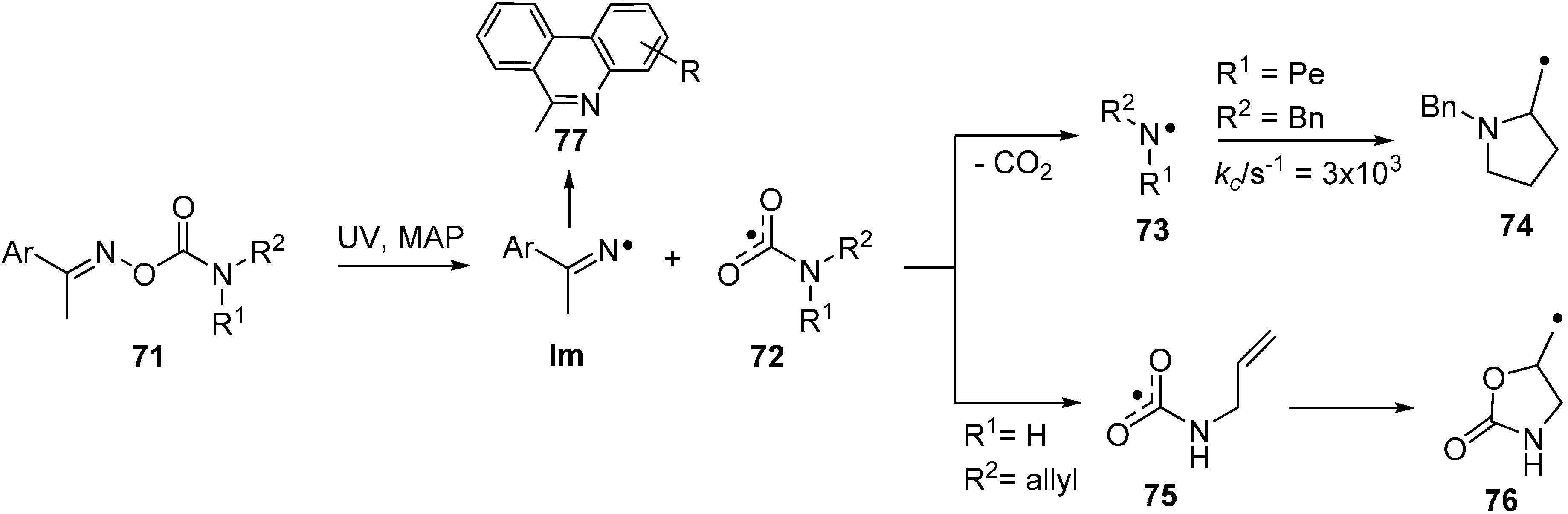

2.8. Oxime Carbamates: Precursors for Iminyl and Aminyl Radicals

Previous interest in oxime carbamates 71 (O-carbamoyl oximes) centred on their biological activities [91,92] and their known inhibition of several enzymes [93,94]. Designer compounds of this class have recently been adapted for release of specific radicals [95]. UV irradiation leads again to selective scission of their N–O bonds with formation of iminyls together with the rare and exotic carbamoyloxyl radicals 72. DFT computations predicted that N,N-di-substituted carbamoyloxyls would dissociate very rapidly to CO2 and di-substituted aminyl radicals 73. However, the computations implied that N-mono-substituted carbamoyloxyls (72, R1 or R2 = H) might have sufficient lifetime to be trapped at low temperatures. Study of UV photolyses of a set of oxime carbamates in solution by EPR spectroscopy revealed that for N,N-di-substitution only Im and aminyl radicals 73 were produced in the accessible temperature range. However, with the mono-substituted N-allyl-precursor 71 (R1 = H, R2 = allyl), the EPR spectrum of the oxazolidinylmethyl radical 76, from ring closure of the corresponding carbamoyloxyl radical 75, was discerned at about 150 K. So, this N-mono-substituted example did have sufficient structural integrity to undergo 5-exo-cyclisation; in confirmation of the theoretical prediction.

At room temperature and above, decarboxylation is rapid so both N-mono- and N,N-di-substituted oxime carbamates provide much needed benign and serviceable alternatives for aminyl radical generation. The EPR parameters of a representative set of aminyl radicals obtained mainly in this way are listed in Table 4. It should be noted that only a very few N-monoalkylaminyl radicals have been detected in solution; though monoarylaminyls do provide good isotropic spectra in which the upe is delocalised into the ring [96].

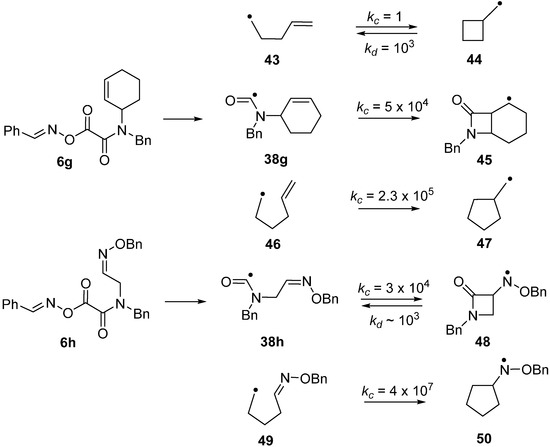

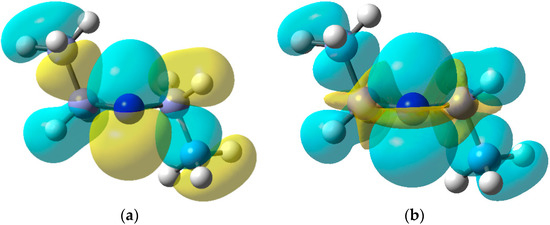

The EPR data indicate that dialkylaminyl radicals are bent; the magnitudes of the a(N) values are consistent with π-type electronic configurations. The DFT computed SOMO and spin density [B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)] for the Et2N• radical in Figure 5 clearly show the π-type orbital associated with the N-atom and the considerable spin density distributed to the Et groups. In this respect, aminyl radicals resemble the familiar C-centred alkyl radicals although, as the cyclisation rate constant in Scheme 11 illustrates, they generally react more slowly.

Table 4.

Isotropic EPR parameters for selected dialkylaminyl radicals R2N• a.

| Radical | T/K | g-Factor | a(N)/G | a(Hβ)/G | a(Hβ)/G | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me2N• | 183 b | 2.0044 | 14.8 | 27.4 (6H) | [97,98] | |

| Et2N• | 210 | 2.0047 | 14.4 | 35.7 (2H) | 35.7(2H) | [95] |

| Bn2N• | 220 | 2.0046 | 14.3 | 37.1 (2H) | 37.1 (2H) | [95] |

| allyl2N• | 210 | 2.0048 | 14.6 | 36.0 (2H) | 36.0 (2H) | [95] |

| BnN•Pe | 230 | 2.0048 | 14.2 | 36.9 (2H) | 35.4 (2H) | [95] |

a In PhBu-t solution unless otherwise specified; b In cyclopropane solution.

Figure 5.

(a) DFT computed SOMO for diethylaminyl radicals; (b) Spin density distribution.

Figure 5.

(a) DFT computed SOMO for diethylaminyl radicals; (b) Spin density distribution.

Scheme 11.

Photochemical reactions of oxime carbamates [95].

Scheme 11.

Photochemical reactions of oxime carbamates [95].

The viability of the alternative mode of oxime carbamate usage, as precursors of iminyl radicals (Im), was effectively demonstrated with diethyl substituted precursors 71 (R1 = R2 = Et). Good yields of phenanthridines were obtained when the Ar group was a biphenyl moiety. Photolysis of precursor 71 with a pent-4-enyl (Pe) chain released aminyl radical 73 (R2 = Bn, R1 = Pe) that was characterised by EPR spectroscopy (Table 4). Cyclisation took place above about 250 K and ring closure kinetic parameters were derived for this N-centred species (Scheme 11).

3. Oxime Ethers in Radical-Mediated Reactions

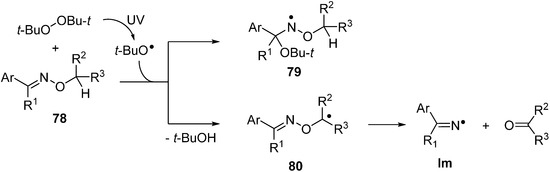

3.1. Homolytic Reactions of O-alkyl and O-aryl Oxime Ethers

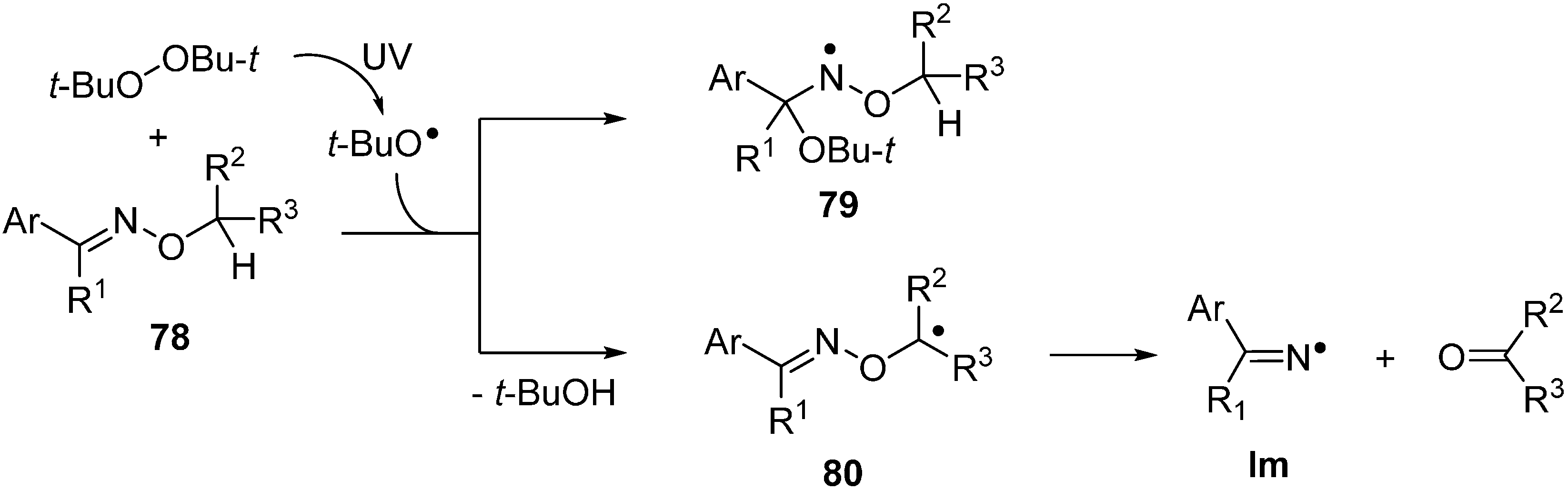

The N–O bonds of most oxime ethers 78 do not readily undergo homolysis on irradiation with UVA or UVB and only low conversions to ketones and/or nitriles could be achieved even after prolonged photolyses [99]. Radicals of many types add to the C=N bonds of oxime ethers particularly rapidly [100]. Not surprisingly, therefore, when t-BuO• radicals are generated in the presence of an O-alkyl, oxime ether 78 addition takes place with production of oxyaminyl radicals 79 (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12.

Radical addition to oxime ethers and radical induced dissociations [99].

Scheme 12.

Radical addition to oxime ethers and radical induced dissociations [99].

However, if the oxime ether contains an O–CH or O–CH2 group, then H-atom abstraction competes with addition such that C-centred radicals 80 are also formed. The latter readily undergo β-scission to release an iminyl radical together with an aldehyde or ketone (Scheme 12) [99]. The importance of abstraction relative to addition depends on the substitution pattern and temperature and consequently this is seldom a clean, selective mode of radical generation from oxime ethers. Photoredox catalytic systems for putting oxime ethers to work have now been developed (see below) but recent attention has focused mainly on thermolytic methods.

3.2. Conventional and Microwave Mediated Thermolyses of Oxime Ethers

Conventional thermal dissociations of oxime ethers R1R2C=NOBn can be brought about by heating them in hydrocarbon solvents at T > ~150 °C. However, products from scission of the N–O bond (BnOH and R1R2C=NH) together with products from O–C bond breaking (R1R2C=NOH and PhCH3) were obtained; so, these substrate types are not suitable as clean radical sources [101]. It was found, however, that O-phenyl ketoxime ethers R1R2C=N–OPh (R1, R2 = alkyl or aryl) undergo selective N–O homolysis upon heating in hydrocarbon solvents at moderate temperatures (T ~ 90 °C) to yield iminyl and phenoxyl radicals [6]. The substantial resonance stabilisation of the phenoxyl radical predisposes the homolysis in favour of N–O scission. In principle, this constituted a new and promising route to iminyl radicals because the phenoxyl radicals usually ended up as the acidic, and therefore easily separable, PhOH.

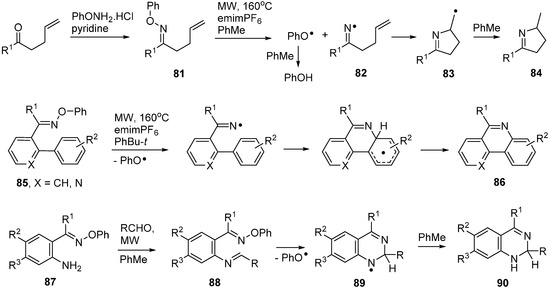

Thermal methods are generally advantageous for preparative work because of their simplicity and ease of scale-up. In practice, however, conventional thermolyses of O-phenyl oxime ethers required long reaction times with consequent poor selectivity and yields. Fortunately, it was discovered that microwave heating (MW) was very advantageous for cleanly generating iminyl radicals from a large range of O-phenyl oxime ethers [29,30]. The optimum conditions for oxime ethers with alkene acceptors 81 involved MW irradiation at 160 °C for 15–30 min in an H-donor solvent such as toluene. The ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate (emimPF6) was added to improve the microwave absorbance level of the medium. Intermediate iminyl radicals such as 82 underwent 5-exo cyclisation to radicals 83 and these abstracted H-atoms from the solvent to afford good yields of 3,4-dihydropyrroles 84 (Scheme 13).

O-Phenyl oxime ethers containing appropriately placed aromatic acceptors 85 also dissociated cleanly under MW radiation. The final step required an oxidation in this case so PhBu-t proved to be a better solvent enabling aza-arenes of type 86 and others to be isolated in good yields. As a further elaboration of the process, 2-aminoarylalkanone O-phenyl oxime precursors 87 were prepared. Mixtures of these, with an equivalent of an aldehyde, on MW irradiation in toluene with emimPF6 as additive, initially yielded imines 88. These were not isolated but dissociated, released iminyl radicals that cyclised exclusively in 6-endo mode to produce aminyl radicals 89. The latter were reduced to dihydroquinazolines 90 under the reaction conditions (Scheme 13) [102,103]. With ZnCl2 as additive to promote condensation the MW reaction proceeded in one pot to afford directly the oxidised quinazolines.

Scheme 13.

MW assisted preparations of dihydropyrroles, aza-arenes and quinazolines from O-phenyl oxime ethers [30,103].

Scheme 13.

MW assisted preparations of dihydropyrroles, aza-arenes and quinazolines from O-phenyl oxime ethers [30,103].

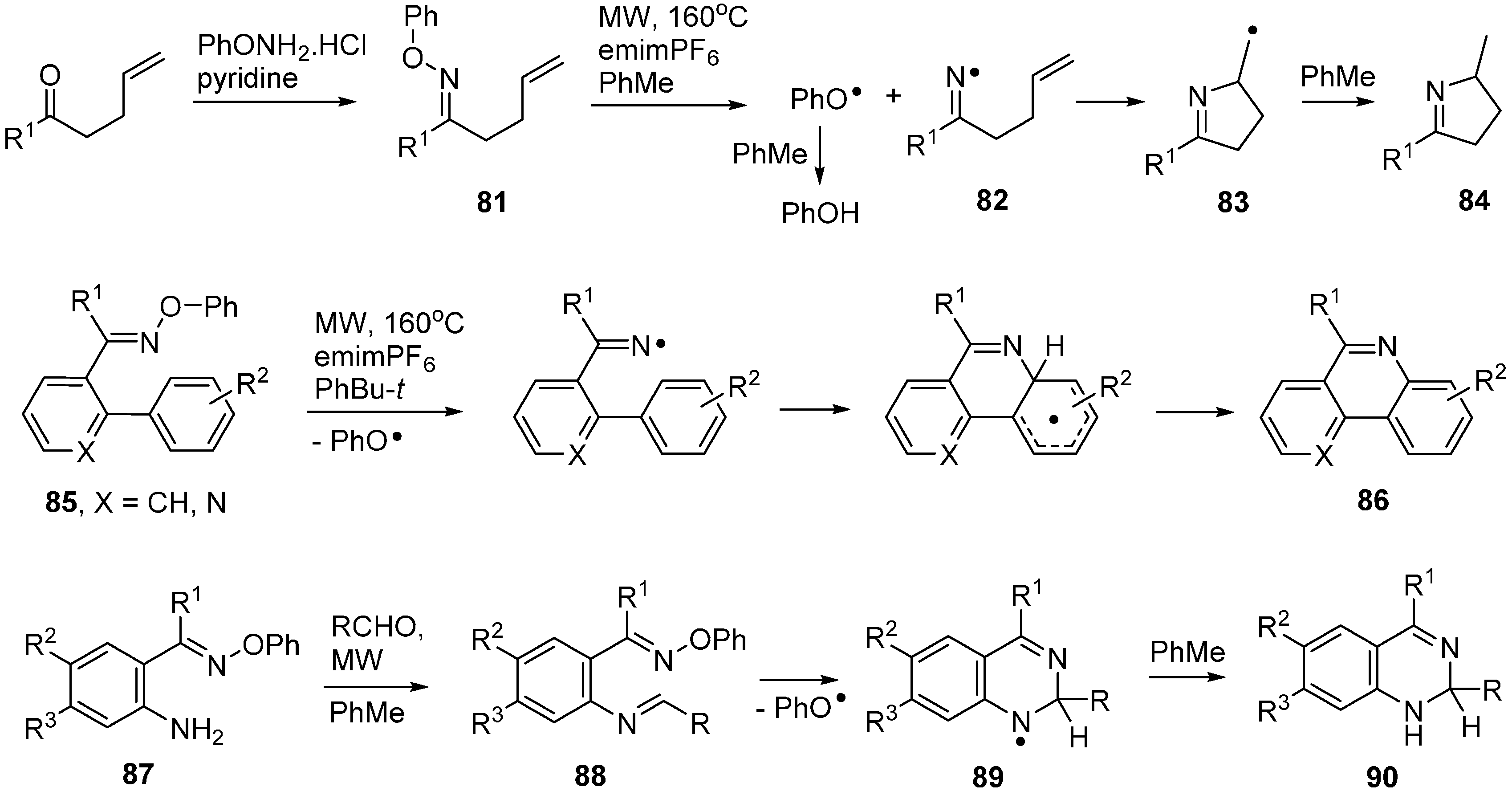

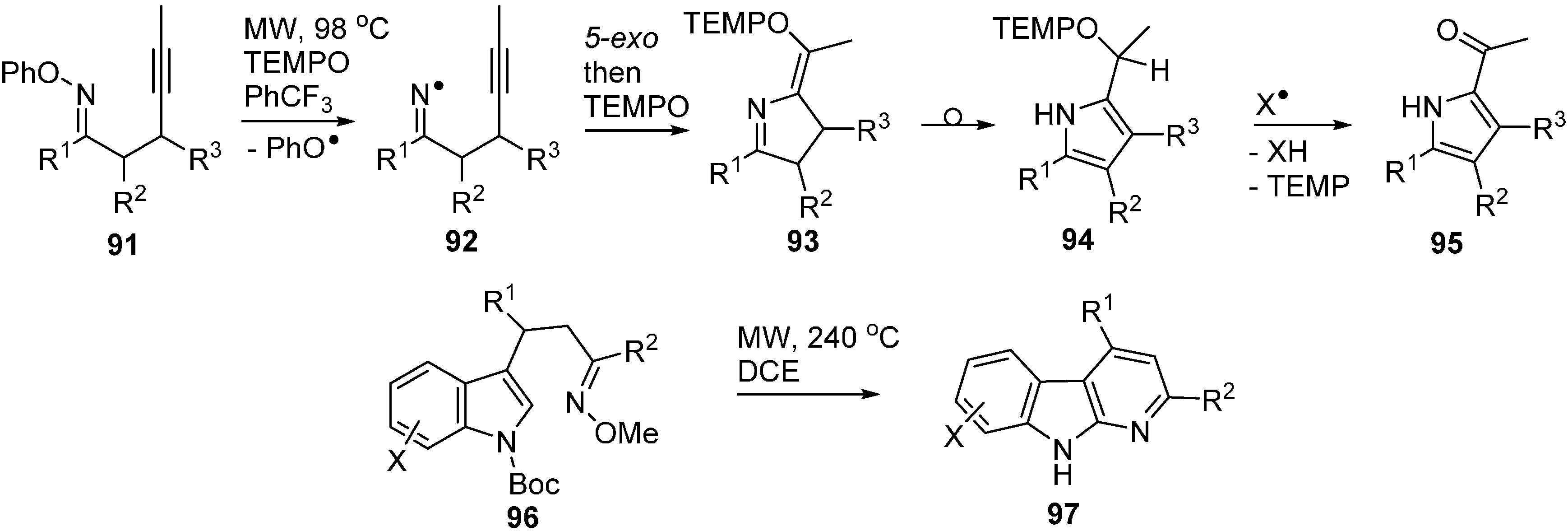

A recent article described microwave promoted reactions of O-phenyl oxime ethers 91 with alkynyl side chains that afforded iminyls 92 as intermediates [104]. In the presence of excess TEMPO, these iminyls ring closed and then coupled with the TEMPO with production of dihydropyrrole intermediates 93 (Scheme 14). These rearranged to pyrrole structures 94 that spontaneously underwent H-atom transfer and fragmentation with production of 2-acylpyrroles 95. The O-phenyl oximes 91 were easily obtained from ketones so the whole process provided ready access to a good range of functionalised pyrroles.

It is worth mentioning the report that indolyl-alkenyl O-methyl oxime ethers 96 were converted to pyridoindoles 97 (α-carbolines) on MW heating to 240 °C (Scheme 14) [105]. Superficially, the reaction resembles that of the O-phenyl oxime ethers but in this case the mechanism was believed to involve electrocyclisation.

Scheme 14.

Cyclisations of O-phenyl and O-methyl oxime ethers [104,105].

Scheme 14.

Cyclisations of O-phenyl and O-methyl oxime ethers [104,105].

3.3. Oxime Ethers and Photoredox Catalysis

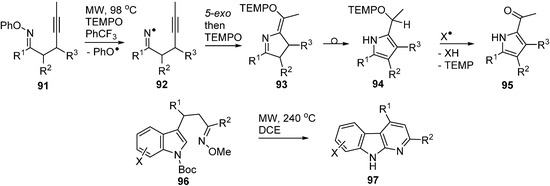

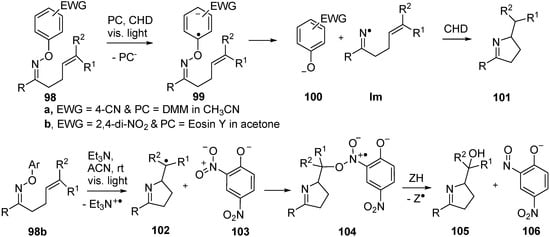

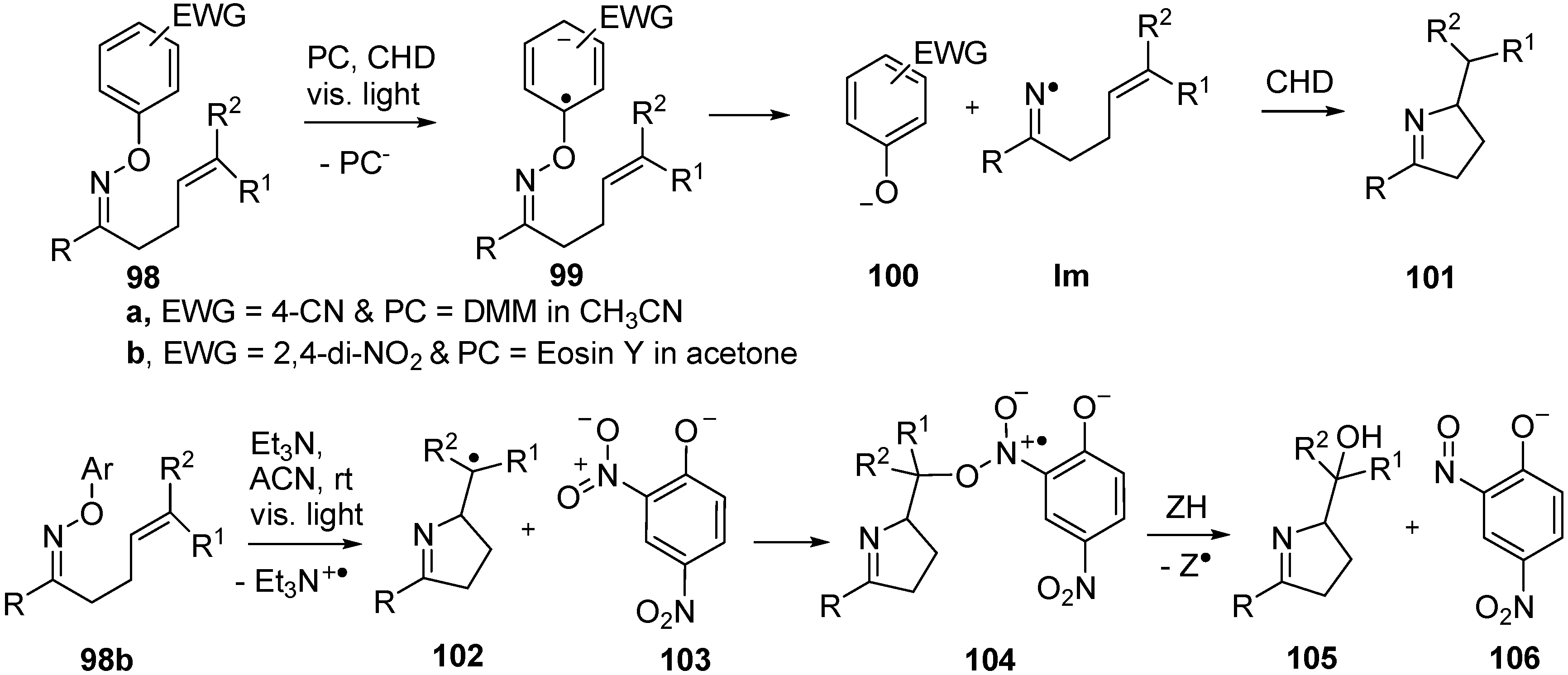

O-Aryl oxime ethers containing electron withdrawing groups (EWG) in their aryl rings released iminyl radicals on irradiation with UVA or visible light when photoredox catalysts (PC) were employed. For example, oxime ether 98a containing 4-CN (or 2,4-di-NO2 or 4-CF3) aryl substitution with a catalytic amount of 1,5-dimethoxynaphthalene (DMN) on irradiation with UV light (λ > 320 nm) in 1,4-cyclohexadiene (CHD) afforded good yields of dihydropyrroles 101 (Scheme 15) [28]. Electron transfer from the excited state of the PC generated the oxime ether radical anion 99 and this dissociated to give the arene-oxide 100a together with the iminyl radical. The latter ring closed and the product 101 was formed by H-atom abstraction from the CHD H-donor present in excess.

More recently, it was shown that the reduction potentials of oxime ethers with O-2,4-dinitroaryl substitution 98b were sufficiently low for the dye eosin Y to be used as the PC and then light of visible wavelength only was needed [106]. An additional interesting finding was that with 98b Et3N could be employed, in place of eosin Y. Irradiation with visible light in CH3CN then led to isolation of imino-alcohols 105. The proposed mechanism involved fast formation of an electron donor–acceptor complex between Et3N and the electron-poor ring of 98b. Excitation with visible light then generated the radical anion analogous to 98 that fragmented to give stable phenoxide 103 and, after 5-exo-cyclisation, pyrrolidinylmethyl radical 102. Oxygenation took place by attack of radical 102 onto the NO2 group of 103 leading to intermediate 104. Homolysis of the N–O bond of 104 gave nitroso-phenoxide 106 and an O-centred radical that rapidly abstracted hydrogen to furnish the product imino-alcohol 105 (Scheme 15) [107]. The scope of the process was found to be wide affording iminoalcohols in good to high yields from alkenes with a range of substituents and including bicyclic products.

In another interesting investigation, the O-methyl oxime ethers derived from 1,1′-biphenyl-2-carbaldehydes were shown to yield phenanthridine derivatives on treatment with visible light and catalytic 9,10-dicyanoanthracene [107]. However, the mechanism of this system was believed to involve photo-electron transfer to the PC with formation and cyclisation of radical cation intermediates.

Scheme 15.

Photoredox catalyzed reactions of O-aryl oxime ethers [107,108].

Scheme 15.

Photoredox catalyzed reactions of O-aryl oxime ethers [107,108].

4. Conclusions

It is clear that an appropriate oxime derivative can be found to provide a benign route, free of toxic metals, unstable peroxides or hazardous azo-compounds, to almost any radical centred on a first row element. These precursors have been exploited for uncomplicated production of known and exotic transient species, enabling the structures and reaction selectivity to be examined; particularly by EPR spectroscopy supported by DFT computations. In addition, they offer platforms for study of the kinetics of ring closures of C-, N- and O-centred radicals and for kinetic study of decarboxylations of several short-lived O-centred species. These compound types also deliver novel and convenient preparative procedures for aza-heterocycles containing both 5-member ring pyrrole type and 6-member ring pyridine structural units. Oxime ethers with O-aryl functionality proved particularly suitable for use with the convenient and innocuous MW technology [108]. There remains ample scope for development of synthetic protocols employing the acyl radicals from ketoxime glyoxalates and the aminyl radicals generated from oxime carbamates. Comparatively few O-containing heterocycles have been made from carbonyl oxime precursors so there is opportunity for developments in that area. Photoredox catalytic methods have been developed for specific oxime ester and oxime ether types. It seems certain that additional photoredox catalysts suitable for this purpose will be developed and applied to a wider range of oxime derivatives.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks EaStCHEM for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pratt, D.A.; Blake, J.A.; Mulder, P.; Walton, J.C.; Korth, H.-G.; Ingold, K.U. OH Bond dissociation enthalpies in oximes: Order restored. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10667–10675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brokenshire, J.L.; Roberts, J.R.; Ingold, K.U. Kinetic applications of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. VII. Self-reactions of iminoxy radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 7040–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, K.U. The only stable organic sigma radicals: Di-tert-alkyliminoxyls. In Stable Radicals; Hicks, R.G., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, B.M.; Wang, M.; Brown, R.E.; Labaziewicz, H.; Ngo, M.; Kettinger, K.W.; Mendenhall, G.D. Spectral and kinetic measurements on a series of persistent iminoxyl radicals. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1997, 10, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-R. Handbook of Bond Dissociation Energies in Organic Compounds; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J.A.; Pratt, D.A.; Lin, S.; Walton, J.C.; Mulder, P.; Ingold, K.U. Thermolyses of O-phenyl oxime ethers. A new source of iminyl radicals and a new source of aryloxyl radicals. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 3112–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, A.R.; Gill, M.; Sadd, J.S.; Thomson, R.H. Iminyls. Part 2. Intramolecular aromatic substitution by iminyls. A new route to phenanthridines and quinolines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1979, 1, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, A.R.; Napier, R.J.; Thomson, R.H. Iminyls. Part 7. Intramolecular hydrogen abstraction: Synthesis of heterocyclic analogs of α-tetralone. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1981, 1, 984–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasebe, M.; Kogawa, K.; Tsuchiya, T. Photochemical arylation by oxime esters in benzene and pyridine: Simple synthesis of biaryl compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 3887–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasebe, M.; Tsuchiya, T. Photodecarboxylative chlorination of carboxylic acids via their benzophenone oxime esters. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 6287–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J.; Callier-Dublanchet, A.-C.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Schiano, A.-M.; Zard, S.Z. Iminyl, amidyl, and carbamyl radicals from O-benzoyl oximes and O-benzoyl hydroxamic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 6517–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J.; Fouquet, E.; Zard, S.Z. Iminyl radicals: Part I. Generation and intramolecular capture by an olefin. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 1745–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J.; Fouquet, E.; Zard, S.Z. Iminyl radicals: Part II. Ring opening of cyclobutyl- and cyclopentyliminyl radicals. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zard, S.Z. Iminyl radicals. A fresh look at a forgotten species (and some of its relatives). Synlett 1996, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Surgenor, B.A.; Aitken, R.A.; Walton, J.C. Thermal rearrangement of indolyl oxime esters to pyridoindoles. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8124–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neta, P.; Fessenden, R.W. Reaction of nitriles with hydrated electrons and hydrogen atoms in aqueous solution as studied by electron spin resonance. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 3362–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.F.; Lawson, A.J.; Record, K.A.F. Conformation and stability of 1,1-diphenylmethyleneiminyl. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1974, 12, 488–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griller, D.; Mendenhall, G.D.; van Hoof, W.; Ingold, K.U. Kinetic applications of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. XV. Iminyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 6068–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.W.; Roberts, B.P.; Winter, J.N. Electron spin resonance study of iminyl and triazenyl radicals derived from organic azides. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1977, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.P.; Winter, J.N. Electron spin resonance studies of radicals derived from organic azides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1979, 2, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, A.J.; Walton, J.C. Enhanced radical delivery from aldoxime esters for EPR and ring closure applications. Chem. Commun. 2000, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, A.J.; Walton, J.C. Exploitation of aldoxime esters as radical precursors in preparative and EPR spectroscopic roles. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2000, 2, 2399–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurney, R.T.; Harper, A.D.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Walton, J.C. An all-purpose preparation of oxime carbonates and resultant insights into the chemistry of alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3436–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Hudson, R.F.; Record, K.A.F. The reaction between oximes and sulfinyl chlorides: A ready, low-temperature radical rearrangement process. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1978, 2, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.F.; Lawson, A.J.; Lucken, E.A.C. A free-radical intermediate in the thermal rearrangement of oxime thionocarbamates. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1971, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, W.R.; Bridge, C.F.; Brookes, P. Radical cyclization onto nitriles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 8989–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tadic-Biadatti, M.-H.; Callier-Dublanchet, A.-C.; Horner, J.H.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S.Z.; Newcomb, M. Absolute rate constants for iminyl radical reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikami, T.; Narasaka, K. Photochemical transformation of γ,δ-unsaturated ketone O-(p-cyanophenyl)oximes to 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrrole derivatives. Chem. Lett. 2000, 29, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. Microwave-assisted preparations of dihydropyrroles from alkenone O-phenyl oximes. Chem. Commun. 2007, 4041–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. Microwave-assisted syntheses of N-heterocycles using alkenone-, alkynone- and aryl-carbonyl O-phenyl oximes: Formal synthesis of neocryptolepine. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5558–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Alonso-Ruiz, R.; Sampedro, D.; Walton, J.C. 5-Exo-cyclizations of pentenyliminyl radicals: Inversion of the gem-dimethyl effect. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 10005–10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomb, M. Synthetic Strategies & Applications. In Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials; Chatgilialoglu, C., Studer, A., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- McBurney, R.T.; Walton, J.C. Interplay of ortho- with spiro-cyclisation during iminyl radical closures onto arenes and heteroarenes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, J.C. The importance of chain conformational mobility during 5-exo-cyclizations of C-, N- and O-centred radicals. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 7983–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skakovskii, E.D.; Stankevich, A.I.; Lamotkin, S.A.; Tychinskaya, L.Y.; Rykov, S.V. Thermolysis of methanolic solutions of acetyl propionyl peroxide. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2001, 71, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Akai, N.; Shibuya, K.; Kawai, A. Structure and reactivity of radicals produced by photocleavage of oxime ester compounds studied by time-resolved electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R.; Campos, P.J.; Garcıa, B.; Rodrıguez, M.A. New light-induced iminyl radical cyclization reactions of acyloximes to isoquinolines. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3521–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Campos, P.J.; Rodrıguez, M.A.; Sampedro, D. Photocyclization of iminyl radicals: Theoretical study and photochemical aspects. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Caballero, A.; Campos, P.J.; Rodriguez, M.A. Photochemistry of acyloximes: Synthesis of heterocycles and natural products. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 8828–8831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Scanlan, E.M.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. From dioxime oxalates to dihydropyrroles and phenanthridines via iminyl radicals. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4189–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Lymer, J.; Scanlan, E.M.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. Dioxime oxalates; new iminyl radical precursors for syntheses of N-heterocycles. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11908–11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, N. Photocatalysis with TiO2 applied to organic synthesis. Aust. J. Chem. 2015, 68, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, D.W.; Walton, J.C. Preparative semiconductor photoredox catalysis: An emerging theme in organic synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 1570–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, D.W.; McBurney, R.T.; Miller, P.; Howe, R.F.; Rhydderch, S.; Walton, J.C. Unconventional titania photocatalysis: Direct deployment of carboxylic acids in alkylations and annulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13580–13583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, D.W.; McBurney, R.T.; Miller, P.; Walton, J.C.; Mills, A.; O’Rourke, C. Titania-promoted carboxylic acid alkylations of alkenes and cascade addition-cyclizations. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1386–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, T.P.; Ischay, M.A.; Du, J. Visible light photocatalysis as a greener approach to photochemical synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanam, J.M.R.; Stephenson, C.R.J. Visible light photoredox catalysis: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, J.; Xiao, W.-J. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6828–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.-Q.; Chen, J.-R.; Xiao, W.-J. Homogeneous visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11701–11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prier, C.K.; Rankic, D.A.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.-D.; Yu, S. Visible-light-promoted and one-pot synthesis of phenanthridines and quinolines from aldehydes and O-acyl hydroxylamine. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2692–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; An, X.; Tong, K.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S. Visible-light-promoted iminyl-radical formation from acyl oximes: A unified approach to pyridines, quinolines, and phenanthridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 4055–4059. [Google Scholar]

- Kolano, C.; Bucher, G.; Wenk, H.H.; Jaeger, M.; Schade, O.; Sander, W. Photochemistry of 9-fluorenone oxime phenylglyoxylate: A combined TRIR, TREPR and ab initio study. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2004, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, E.M.; Walton, J.C. Preparation of oxime oxalate amides and their use in free-radical mediated syntheses of lactams. Chem. Commun. 2002, 2086–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, E.M.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Walton, J.C. Preparation of β- and γ-lactams from carbamoyl radicals derived from oxime oxalate amides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, R.; Ingold, K.U. Cis-Alkylcarbamoyl radicals. The overlooked conformer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 7687–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, A.F.; Jackson, L.V.; Walton, J.C. A kinetic EPR study of the dissociation of 1-carbamoyl-1-methylcyclohexa-2,5-dienyl radicals: Release of aminoacyl radicals and their cyclisation. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2002, 2, 1839–1843. [Google Scholar]

- DiLabio, G.A.; Scanlan, E.M.; Walton, J.C. Kinetic and theoretical study of 4-exo ring closures of carbamoyl radicals onto C=C and C=N bonds. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Other acyl radicals [RC•(O)], diazenyls [RN=N•] and a few P-centred radicals share this characteristic

- Park, S.-U.; Varick, T.R.; Newcomb, M. Acceleration of the 4-exo radical cyclization to a synthetically useful rate. Cyclization of the 2,2-dimethyl-5-cyano-4-pentenyl radical. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 2975–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; Moad, G. The kinetics and mechanism of ring opening of radicals containing the cyclobutylcarbinyl system. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1980, 2, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, K.U.; Maillard, B.; Walton, J.C. The ring-opening reactions of cyclobutylmethyl and cyclobutenylmethyl radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1981, 2, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, G.B.; Pattenden, G.; Reynolds, S.J. Cobalt-mediated reactions: Inter- and intramolecular additions of carbamoyl radical to alkenes in the synthesis of amides and lactams. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1994, 1, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, A.F.; Jackson, L.V.; Walton, J.C. Preparation of β-and γ-lactams via ring closures of unsaturated carbamoyl radicals derived from 1-carbamoyl-1-methylcyclohexa-2,5-dienes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, I.; Miyazato, H.; Kuriyama, H.; Tanaka, M.; Komatsu, M.; Sonoda, N. Broad-spectrum radical cyclizations boosted by polarity matching. carbonylative access to α-stannylmethylene lactams from azaenynes and CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 5632–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fremont, S.L.; Belletire, J.L.; Ho, D.M. Free radical cyclizations leading to four-membered rings. I. Beta-lactam production using tributyltin hydride. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 2335–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, H.; Kameoka, C.; Kodama, K.; Ikeda, M. Asymmetric radical cyclization leading to β-lactams: stereoselective synthesis of chiral key intermediates for carbapenem antibiotics PS-5 and thienamycin. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassayre, J.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Saunier, J.-B.; Zard, S.Z. β- and γ-lactams by nickel powder mediated 4-exo or 5-endo radical cyclizations. A concise construction of the mesembrine skeleton. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Annibale, A.; Pesce, A.; Resta, S.; Trogolo, C. Manganese(III)-promoted free radical cyclizations of enamides leading to β-lactams. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 13129–13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryans, J.S.; Chessum, N.E.A.; Parsons, A.F.; Ghelfi, F. The synthesis of functionalized β- and γ-lactams by cyclization of enamides using copper(I) or ruthenium(II). Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 2901–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Peacock, J.L. An amidyl radical cyclization approach towards the synthesis of β-lactams. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C. Unusual radical cyclisations. Top. Curr. Chem. 2006, 264, 163–200. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, E.M.; Walton, J.C. Radical 4-exo cyclizations onto O-alkyloxime acceptors: Towards the synthesis of penicillin-containing antibiotics. Helv. Chim. Acta 2006, 89, 2133–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; Easton, C.J.; Lawrence, T.; Serelis, A.K. Reactions of methyl-substituted 5-hexenyl and 4-pentenyl radicals. Aust. J. Chem. 1983, 36, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; Schiesser, C.H. A force-field study of alkenyl radical ring closure. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Joe, G.H.; Do, J.Y. Highly efficient intramolecular addition of aminyl radicals to carbonyl groups: A new ring expansion reaction leading to lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3328–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C. The oxime portmanteau motif: Released heteroradicals undergo incisive EPR interrogation and deliver diverse heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBurney, R.T.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Smart, L.A.; Yu, Y.; Walton, J.C. UV promoted phenanthridine syntheses from oxime carbonate derived iminyl radicals. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7974–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, D.J.; Kochi, J.K. Electron spin resonance studies of carboxy radicals. Adducts to alkenes J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 2635–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateauneuf, J.; Lusztyk, J.; Maillard, B.; Ingold, K.U. First spectroscopic and absolute kinetic studies on (alkoxycarbonyl)oxyl radicals and an unsuccessful attempt to observe carbamoyloxyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 6727–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühl, M.; DaBell, P.; Manley, D.W.; McCaughan, R.P.; Walton, J.C. Bicarbonate and alkyl carbonate radicals: Their structural integrity and reactions with lipid components. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBurney, R.T.; Eisenschmidt, A.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Walton, J.C. Rapid and selective spiro-cyclisations of O-centred radicals onto aromatic acceptors. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochi, J.K.; Gilliom, R.D. Decompositions of peroxides by metal salts. VII. Competition between intramolecular rearrangement of free radicals and oxidation by metal salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 5251–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, M. Free radical cyclizations. XVII. Mechanistic studies. Pure Appl. Chem. 1974, 40, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; Ingold, K.U. Free-radical Rearrangements. In Rearrangements in Ground and Excited States; De Mayo, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 161–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, J.; Gallou, F. Ring closure reactions of substituted 4-pentenyl-1-oxy radicals. The stereoselective synthesis of functionalized disubstituted tetrahydrofurans. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6706–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J.; Daniel, K.; Rummey, C.; Bringmann, G. On the stereoselectivity of 4-penten-1-oxyl radical 5-exo-trig cyclizations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 4089–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocker, Y.; Davison, B.L.; Deits, T.L. Decarboxylation of monosubstituted derivatives of carbonic acid. Comparative studies of water- and acid-catalyzed decarboxylation of sodium alkyl carbonates in water and water-d2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 3564–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenauer, H.P.; Wagner, J.P.; Schreiner, P.R. Gas-phase preparation of carbonic acid and its monomethyl ester. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11766–11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, A.P.; Durden, J.A., Jr.; Sousa, A.A.; Weiden, M.H.J. Novel insecticidal oxathiolane and oxathiane oxime carbamates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Jadhav, S.D.; Deshmukh, M.B. Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of new oxime carbamates of 3-aryl-2-thioquinazolin-4(3H)-one. J. Chem. Sci. 2012, 124, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, S.; de Simone, C.; Dallavalle, S.; Fezza, F.; Nannei, R.; Battista, N.; Minetti, P.; Quattrociocchi, G.; Caprioli, A.; Borsini, F.; et al. A new group of oxime carbamates as reversible inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4406–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sit, S.Y.; Conway, C.M.; Xie, K.; Bertekap, R.; Bourin, C.; Burris, K.D. Oxime carbamate-discovery of a series of novel FAAH inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBurney, R.T.; Walton, J.C. Dissociation or cyclization: Options for a triad of radicals released from oxime carbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7349–7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelsen, S.F.; Landis, R.T. Diazenium cation-hydrazyl equilibrium. Three-electron-two-center π systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danen, W.C.; Rickard, R.C. Nitrogen-centered free radicals, IV. Electron spin resonance study of transient dialkylaminium radical cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 3254–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danen, W.C.; Kensler, T.T. Electron spin resonance study of dialkylamino free radicals in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 5235–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, A.J.; Walton, J.C. Photolytic and radical induced decompositions of O-alkyl aldoxime ethers. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2000, 2, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauh, P.; Fallis, A.G. Rate constants for 5-exo secondary alkyl radical cyclizations onto hydrazones and oxime ethers via intramolecular competition experiments. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 6960–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.A.; Ingold, K.U.; Lin, S.; Mulder, P.; Pratt, D.A.; Sheeller, B.; Walton, J.C. Thermal decomposition of O-benzyl ketoximes; role of reverse radical disproportionation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. 2-(Aminoaryl)alkanone O-phenyl oximes: Versatile reagents for syntheses of quinazolines. Chem. Commun. 2008, 2935–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Cubillo, F.; Scott, J.S.; Walton, J.C. Microwave-promoted syntheses of quinazolines and dihydroquinazolines from 2-aminoarylalkanone O-phenyl oximes. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4934–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Jalan, A.; Kubosumi, A.R.; Castle, S.L. Microwave-promoted tin-free iminyl radical cyclization with TEMPO trapping: A practical synthesis of 2-acylpyrroles. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markey, S.J.; Lewis, W.; Moody, C.J. A new route to α-carbolines based on 6π-electrocyclization of indole-3-alkenyl oximes. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 6306–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.; Booth, S.G.; Essafi, S.; Dryfe, R.A.W.; Leonori, D. Visible-light-mediated generation of nitrogen-centered radicals: Metal-free hydroimination and iminohydroxylation cyclization reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14017–14021. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, J.L.; Grassbaugh, B.R.; Tran, Q.M.; Armada, N.R.; de Lijser, H.J.P. Catalytic oxidative cyclization of 2′-arylbenzaldehyde oxime ethers under photoinduced electron transfer conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBurney, R.T.; Portela-Cubillo, F.; Walton, J.C. Microwave assisted radical organic syntheses. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).