Abstract

This study explains repeat purchase intentions on e-commerce platforms as a problem of fit between what the interface signals (Customer Service Orientation, CSO) and what the system delivers (Internal Service Quality, ISQ). Using survey data from Chinese platform users (N = 605), second-order polynomial models with response-surface analysis (RSA) show that repurchase intention rises when CSO and ISQ increase together, exhibits diminishing returns at high joint levels, and declines as the two diverge. A structural equation model (SEM) provides cross-sectional evidence consistent with mediation via pride in membership; when CSO and ISQ are modeled jointly with pride, CSO shows the larger direct association with repurchase. We also find that trust and security awareness initiatives act as a structural assurance that flattens the CSO–ISQ surface, attenuating both slopes and curvatures. Taken together, the results advance a fit-based account of digital service in which outcomes depend on the alignment of interface signals with executional capability and operate through identity-based pride, with platform-level assurances bounding marginal returns. Managerially, the findings imply prioritizing the closure of CSO–ISQ gaps and reducing execution variance before pursuing further single-dimension upgrades.

1. Introduction

Digital marketplaces now mediate a large share of consumer exchange, with platform design shaping how customers experience value beyond prices and assortments [1]. On multi-sided platforms, customers form intentions to return not only from prices and assortments but also from how they are treated before, during, and after a transaction [2]. Two facets of the service system are especially critical. Customer Service Orientation (CSO) reflects the platform’s outward, customer-facing stance, how promptly and accurately it responds to needs and how enjoyable and respectful the interaction feels [3,4,5]. Internal Service Quality (ISQ) represents the backstage capability to deliver reliably through clear communication, efficient and transparent procedures, fair rewards, and trustworthy policies for payment, privacy, and returns.

While these two facets capture the frontstage and backstage of service provision, they are embedded within a broader process of value creation rather than existing as isolated components [6,7]. From a process perspective, digital service delivery unfolds through continuous interactions among multiple actors such as platform operators, sellers, and consumers [8,9]. These interactions involve resource integration, actor engagement, and agency, through which participants jointly create value [10]. Incorporating this process perspective clarifies that the effectiveness of service delivery depends not only on the quality of frontstage and backstage elements but also on how they are dynamically coordinated throughout the service process [11]. A useful approach that has been proposed for analyzing and visualizing such coordination is service blueprinting, a method of service design that maps customer actions, frontstage activities, and backstage processes to identify points of alignment or potential breakdown. This process view thus complements the structural distinction between CSO and ISQ and highlights how value emerges through their ongoing integration within the platform ecosystem [12,13].

In fast, remote, and information-asymmetric digital contexts, these two facets shape perceptions of safety and value in repurchase: when CSO and ISQ align, customers perceive coherence and reliability; when they diverge, uncertainty and risk increase [14,15].This study focuses on transaction-oriented e-commerce platforms, where value is created primarily through the facilitation of buyer–seller exchanges rather than the co-development of innovations or complementary products. This focus allows a clear examination of how frontstage service orientation and backstage operational quality jointly shape customer experience and repurchase intention.

In practice, these two facets are often misaligned. Platforms may promise warmth and responsiveness via chat or social media yet expose customers to opaque refunds, slow claim handling, or confusing policies. Conversely, well-engineered processes can be under-signaled by brusque or inattentive frontline contact, leaving value unrecognized at the moment of choice [16,17,18]. Such mismatches are common in online retailing, where different teams own the interface and the execution layer, and rapid feature releases can outpace process redesign [19]. For customers, misalignment creates expectancy violations and cue conflict: what the platform promises and what it can deliver do not cohere. The result is heightened uncertainty about payment, privacy, and redress, erosion of trust, and ultimately weaker repurchase intentions. Although service quality research has long emphasized customer satisfaction and trust, it has tended to examine individual cues in isolation. The alignment between frontstage promises and backstage delivery has been noted conceptually but rarely tested empirically. These recurring mismatches suggest that effective service management requires not only improving each facet independently but also ensuring their alignment [20,21,22].

Existing research has established that customer-facing cues (CSO) and Internal Service Quality (ISQ) each matter for satisfaction, trust, and loyalty, yet level alone is an incomplete lens [23]. Most prior studies have examined these constructs independently, providing limited insight into how their interaction shapes customer responses [24]. Building on fit theory in strategy and services, outcomes depend on how complementary elements align [25,26]. Conceptually, CSO is the expectation-setting signal at the interface, whereas ISQ is the performance-delivering system behind the interface; customers compare the two [23]. When they move together, expectations are confirmed and risk is reduced; when they diverge, disconfirmation and attributional blame follow [27]. Although several studies acknowledge the importance of alignment, few have tested it directly or captured its nonlinear nature. This study extends prior work by treating CSO–ISQ alignment as a continuous surface rather than as a simple additive index, allowing the effects of fit and misfit to be estimated more precisely. Polynomial regression with response-surface analysis provides an effective means to separate these effects while avoiding the limitations of traditional difference-score methods [28,29,30].

Beyond their joint level and alignment, two psychological mechanisms clarify how CSO and ISQ shape repeat patronage [31]. The first is pride in membership, a sense of identification and self-enhancement that arises when customers associate themselves with a platform perceived as competent, fair, and caring [32]. CSO conveys socioemotional signals of respect and responsiveness, while ISQ provides structural assurances of competence and procedural justice. When these signals are coherent, they elevate pride, which strengthens commitment and increases the likelihood of continued purchasing beyond direct utility effects [31,33]. The second mechanism is awareness of trust-and-security initiatives such as buyer protection, secure payment, and transparent privacy controls. These safeguards provide visible assurances of safety and reliability; when salient, they reduce the diagnostic weight customers place on other service cues, thereby weakening the incremental impact of further CSO or ISQ improvements [22,34]. Although prior studies have examined pride and trust as separate drivers of loyalty, their joint role in the CSO–ISQ alignment process remains underexplored. This study integrates both mechanisms to capture how emotional identification and perceived assurance jointly shape repurchase intentions [35].

Against this backdrop, we examine how CSO and ISQ jointly shape repurchase intention on large e-commerce platforms, focusing on the mechanism of pride in membership and the boundary condition of trust-and-security awareness [20]. This study fills the gap in prior research by empirically testing how alignment between frontstage orientation and backstage quality affects customer loyalty. We conceptualize congruence as the central structural condition for favorable outcomes and explicitly test both fit and misfit using response-surface logic [36]. We further assess pride in membership as the mediating pathway and trust-and-security awareness as a substitutional moderator that flattens slopes and curvatures of the CSO–ISQ surface [37,38].

While the study builds primarily on fit theory, it also aligns with the service-dominant logic view that value in digital platforms is co-created through coordinated actions among multiple actors [39]. In this sense, the alignment between customer-facing orientation and internal service quality reflects a structural condition for effective value co-creation. Beyond this structural view, digital service should be understood as a dynamic process in which value continuously emerges from ongoing exchanges of resources and competencies among participants [40]. From a resource-based perspective, platforms operate as resource integrators that enhance resource density, the accessibility and diversity of valuable resources, and achieve resource orchestration by coordinating technological, human, and organizational assets to support adaptive service delivery [41]. This dynamic configuration enables platforms to realign frontstage signals and backstage capabilities as conditions evolve, ensuring sustained value creation. Integrating this dynamic, resource-based view strengthens the theoretical foundation of the study and situates CSO–ISQ alignment within broader mechanisms of platform evolution and value co-creation [42]. This study makes three contributions. Theoretically, it proposes a fit-based theory of digital service that links customer-facing orientation (CSO) with backstage execution (ISQ) and explains how their alignment, rather than level alone, drives customer loyalty. This perspective also identifies the benefits of alignment, the diminishing returns at high joint levels, and the penalties of misalignment [43]. Empirically, it demonstrates the usefulness of modeling the joint effects of CSO and ISQ on repurchase intention, separating overall level from discrepancy, and testing the mediating role of pride in membership and the moderating effect of trust and security awareness [44]. Managerially, it clarifies when investments in frontline orientation, process quality, or security assurance yield the greatest return, emphasizing that closing CSO–ISQ gaps and improving operational consistency should come before further enhancements, since alignment between promise and delivery is the key constraint on repeat business [45,46].

In this study, fit theory serves as the primary theoretical foundation because our core prediction concerns the alignment between CSO and ISQ and its geometric effects on repurchase intention. Expectation–confirmation theory provides the psychological micro-foundation explaining how aligned signals produce confirmation and behavioral intention. Service-dominant logic, value co-creation, and resource orchestration are incorporated as complementary, system-level perspectives that contextualize CSO–ISQ alignment within broader platform-based value creation processes. This hierarchy clarifies the study’s theoretical grounding and how each framework contributes to the overall model.

To preview the remainder of the paper, Section 2 reviews the literature on fit theory and expectation-confirmation and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research design and analytic approach, emphasizing second-order polynomial models with response-surface analysis (RSA) for fit and misfit, mediation tests in SEM, and moderation analyses. Section 4 presents the empirical findings and robustness checks. Section 5 discusses theoretical and managerial implications, acknowledges limitations, and concludes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fit Theory and Response-Surface Logic

Fit theory posits that organizational outcomes depend not only on the absolute levels of focal attributes but also on the degree to which complementary elements are aligned [25,47]. Early contingency research formalized this idea by distinguishing selection and interaction views of fit, where environments select appropriately configured organizations or performance reflects the interaction between internal design and contextual demands, and by articulating a systems perspective that treats alignment among multiple subsystems as the foundation of effectiveness [48]. Strategy and design research subsequently elaborated different forms of fit, differentiating matching, profile deviation, and configurational (Gestalt) logics, while emphasizing that theoretical claims about congruence require empirical tests that capture alignment directly. Across these streams, the common intuition is that congruence fosters coherent expectations, reduces coordination losses, and enhances efficiency, whereas incongruence introduces frictions, ambiguity, and hidden costs that undermine performance [49].

A core implication of fit theory is that alignment is not captured by a single index but by a response surface defined over the joint space of two or more attributes [25,50]. Early studies often relied on difference scores (e.g., |X − Y|) to represent fit [51]. However, such measures confound mean levels with discrepancies, assume symmetry between over- and under-shooting, and prevent separate tests of linear and curvilinear effects [52]. Methodological advances therefore recommend polynomial regression combined with response-surface analysis (RSA) as the appropriate way to operationalize fit [28,29,53]. RSA models outcomes as a second-order function of the attributes and evaluates theoretically meaningful surface features. These include the line of congruence (LOC, X = Y), which reveals the slope and curvature of fit effects; the line of incongruence (LOIC, X = −Y, after centering and commensurate scaling), which captures misfit penalties; and the stationary point and principal axes, which indicate the surface’s optimum and orientation [54,55,56]. This framework enables rigorous tests of core theoretical propositions—whether higher joint levels are beneficial (positive LOC slope), whether returns diminish at high alignment (negative LOC curvature), and whether discrepancies are harmful (negative LOIC curvature) [57].

In service and exchange settings, fit theory has been applied to pairs of constructs that set expectations at the interface and enable their fulfillment behind the interface [25,58]. Congruence between outward-facing orientation and backstage execution capability is expected to enhance evaluations because aligned signals reduce attributional conflict and uncertainty, whereas misalignment creates expectancy violations that invite negative attributions [59]. The logic also anticipates nonlinearity: as aligned performance approaches an upper zone of tolerance, additional improvements yield smaller incremental gains, producing concavity along the LOC. Conversely, as discrepancies grow, penalties accelerate due to the salience of inconsistency and the asymmetry of negative information, reflected in curvature along the LOIC [60,61].

Our study builds on this tradition by conceptualizing Customer Service Orientation (CSO) as the interface-level signal and Internal Service Quality (ISQ) as the backstage execution capability [62]. Fit theory provides the structural lens for our focal predictions: (i) when CSO and ISQ are aligned, repurchase intention is expected to increase with their joint level [25,63]; (ii) the incremental gains from alignment should diminish at high joint levels [64]; and (iii) growing incongruence, one high and the other low, should reduce repurchase intention [65]. Response-surface analysis (RSA) offers the appropriate empirical framework to test these propositions, avoiding the conflation of level and discrepancy and enabling recovery of the geometric features of the CSO–ISQ surface implied by fit theory [25,28,66].

2.2. Expectation–Confirmation in Electronic Commerce

Expectation–Confirmation (EC) theory holds that post-purchase evaluations arise from comparing pre-consumption expectations with perceived performance, yielding confirmation (performance meets or exceeds expectations) or disconfirmation (performance falls short). Confirmation increases satisfaction and, in turn, approach tendencies such as repurchase and continuance, whereas disconfirmation depresses them [67,68,69]. EC research clarifies that expectations may be predictive or normative; that evaluation operates over both attribute-level and overall judgments; and that adaptation and assimilation processes shift reference points over time, generating diminishing sensitivity at high performance levels and a zone of tolerance within which small deviations are weakly diagnostic [70,71].

Information systems and electronic commerce studies adapt EC to repeated online transactions, often under the label IS continuance [72]. Initial beliefs (e.g., usefulness, ease, service quality) shape expectations; subsequent interaction with the website or platform informs perceived performance; confirmation or disconfirmation drives satisfaction; and satisfaction—augmented by perceived value and habit, predicts continuance or repurchase intention [73,74,75]. Relative to offline settings, online exchange foregrounds process quality (speed, responsiveness), assurance (privacy, security), and fulfillment (accuracy, delivery, returns). Empirical studies show that website and e-service quality dimensions (e.g., responsiveness, reliability/fulfillment, privacy/security, policy clarity) raise perceived performance and confirmation, thereby increasing satisfaction and repurchase or continuance; conversely, gaps on these dimensions produce disconfirmation and weaken intentions [76,77,78].

EC theory in electronic commerce also incorporates the risk–trust architecture of online exchange. Because transactions are impersonal, information-asymmetric, and invoke payment and privacy risk, structural assurances (buyer protection, secure payment, refund guarantees, transparent privacy controls) operate as highly diagnostic signals that compress perceived variance in performance [79,80]. When such assurances are salient, consumers require less inferential work from other service cues to form confirmation judgments; when assurances are weak or opaque, they rely more heavily on observed service quality to infer reliability [81,82]. This logic implies potential substitution between structural assurances and other cues in shaping confirmation and predicts attenuated marginal returns to additional service-quality improvements under strong assurance [83].

Taken together, EC provides a microfoundation for the fit logic in our study. We conceptualize CSO as the expectation-setting signal at the interface (e.g., promptness, accuracy, friendliness) and ISQ as the performance-delivering system behind the interface (communication, problem-solving procedures, rewards and benefits, policy clarity) [84]. Congruence between CSO and ISQ yields systematic confirmation; what is promised is delivered—which raises satisfaction and, consequently, repurchase intention; incongruence yields disconfirmation (over-promising and under-delivery or under-signaling and under-recognition), depressing repurchase. EC’s adaptation-level and zone-of-tolerance ideas further anticipate diminishing returns when CSO and ISQ are jointly high, consistent with concave curvature along the LOC [57]. Finally, trust and security awareness functions as a structural assurance that can flatten the response surface by reducing the diagnostic weight consumers place on CSO and ISQ when forming confirmation judgments [85].

2.3. Service and Service Quality in Platform Contexts

Service in digital platforms extends beyond individual transactions to a systemic and ongoing process of value realization among multiple interacting actors. Drawing on service-dominant logic, service is defined as the application of competencies for the benefit of others and as the fundamental basis of exchange [86]. Under this view, value is co-created rather than delivered, emerging through coordinated interactions among users, providers, and technological artifacts rather than through one-directional provision by the firm [87].

Service-dominant logic further conceptualizes service as an inherently dynamic system in which value continually emerges through adaptive interactions among resource-integrating actors. Its foundational premises emphasize that all social and economic actors are resource integrators, that value is co-created through reciprocal service provision, and that value is always determined by the beneficiary in context [88]. These axioms position service ecosystems as self-adjusting and evolving structures driven by ongoing exchange, feedback, and learning rather than static transactions [89]. Within digital platforms, this dynamic nature implies that frontstage orientations and backstage capabilities must continuously realign as actors, technologies, and expectations change over time. Consequently, understanding service quality and CSO–ISQ alignment requires acknowledging the adaptive and evolutionary characteristics of platform-based value creation [90].

In this systemic perspective, the locus of value creation shifts from discrete encounters to the configuration of the entire service system, the interdependent structure of human and technical resources that enables value-in-use [91]. Service interactions thus involve customers as active participants who contribute external resources such as information, effort, and time to the co-creation process. Their participation directly influences perceived service quality and the realization of value-in-use [92].

Building on service quality theory, perceived quality arises from both the technical outcome of what is delivered and the functional quality of how it is delivered, with the overall perception also shaped by the organization’s image [93]. In digital platforms, these dimensions correspond to the reliability and efficiency of backstage operations and the responsiveness and empathy of frontstage encounters. The integration of these aspects through coherent processes determines whether customers perceive the platform as competent, fair, and trustworthy [94].

Within e-commerce platforms, service quality reflects the joint functioning of customer-facing and backstage capabilities [95]. Building on service systems theory, platforms can be viewed as socio-technical ecosystems in which frontstage cues of responsiveness and care must be supported by reliable, fair, and timely execution behind the interface [96]. Alignment between these layers, namely Customer Service Orientation (CSO) and Internal Service Quality (ISQ), creates coherence and predictability that foster trust and value-in-use. When the promises signaled at the interface match the platform’s delivery capacity, customers experience confirmation and smooth coordination; when they diverge, disconfirmation and uncertainty arise, weakening confidence and repeat patronage. This structural harmony thus represents the mechanism by which digital platforms convert technical performance into relational and behavioral outcomes such as repurchase intention [97].

2.4. Customer Service Orientation and Internal Service Quality

In the services and general management literature, Customer Service Orientation (CSO) denotes an organization’s outward, customer-facing stance: sensitivity to needs, responsiveness, accuracy, empathy, and a prosocial, friendly demeanor in service encounters [98]. Research on customer orientation and service climate links such cues to satisfaction, trust, and behavioral intentions by shaping expectations and relational value at the interface [99]. Studies distinguish instrumental facets (e.g., prompt, accurate responses that reduce customer effort) and socioemotional facets (e.g., warmth, enjoyment in interaction) and show that both motivate approach behaviors and loyalty, directly and via affective mechanisms such as identification or pride [100]. In digital settings, the same logic carries over to interface cues—latency in replies, clarity and tone in messages, conversational quality of chatbots or agents, and frictionless handoffs—whose visibility and temporal proximity make CSO especially diagnostic at the moment of choice [101].

By contrast, Internal Service Quality (ISQ) refers to the backstage capability to deliver service reliably once promises are made [102]. In general management and service operations, it encompasses communication clarity, well-specified procedures, transparent and fair policies, timely and accurate fulfillment, ease of claims and returns, and embedded safeguards such as security and privacy. This stream emphasizes that outcomes depend on the integrity of the service system—how processes, rules, and support infrastructure coordinate to reduce variance and ensure procedural justice—rather than on frontline behavior alone [103,104]. In platform and e-retailing contexts, validated e-service frameworks similarly highlight the execution layer: responsiveness and accuracy of information; problem-solving effectiveness; fulfillment and returns; policy clarity; system availability and privacy/security. These backstage qualities reduce perceived risk and increase predictability, thereby supporting satisfaction, trust, and repeat purchase [105].

Although many studies examine CSO and ISQ (or close analogs) separately, their combination is theoretically complementary: CSO sets expectations at the interface, and ISQ fulfills them behind the interface [106]. Evidence across service settings indicates that aligned signals—what the organization promises and what its system can deliver—are associated with higher satisfaction, trust, and loyalty than either dimension in isolation, whereas misalignment (over-promising and under-delivering, or under-signaling and over-delivering) invites negative attributions or leaves value under-recognized [107]. Methodologically, earlier work often relied on additive models or difference scores; more recent research argues for polynomial regression with response-surface analysis (RSA) to separate level from discrepancy, test diminishing returns at high aligned levels, and quantify penalties to incongruence [28,108]. Within electronic commerce, this joint view is particularly salient because interface cues and process assurances are encountered within a compressed, digitally mediated decision window; customers weigh both immediate treatment (CSO) and execution safeguards (ISQ) when forming repurchase intentions [109].

2.5. Repurchase Intention

Repurchase intention denotes a customer’s self-reported propensity to buy again from the same provider and is widely treated as the proximal predictor of behavioral loyalty in services and digital commerce [110]. In marketing and information systems models, perceived quality and value shape satisfaction, which in turn informs intentions to remain, recommend, or repurchase [111,112]. In online contexts, continuance (repeat use or purchase) has been theorized through Expectation–Confirmation logic: confirmation of prior expectations increases satisfaction, and satisfied users intend to continue using the service or vendor [113]. Beyond satisfaction, trust and perceived risk are central antecedents because transactions are mediated and information-asymmetric; structural assurances (e.g., buyer protection, secure payments, privacy safeguards) and vendor-level trust beliefs lower perceived risk and increase intentions to transact again [114]. Complementary work operationalizes electronic service quality as a multidimensional driver of repurchase and related intentions (e.g., efficiency, fulfillment, system availability, privacy; website design, reliability/fulfillment, privacy/security, customer service) [115]. Taken together, prior research positions repurchase intention as a function of (i) experienced or anticipated performance encoded in service quality and value, (ii) confirmation that translates performance into satisfaction and continuance, and (iii) risk-mitigating institutional cues that render repeat transactions attractive.

2.6. Pride in Membership

Pride in membership is an identity-based, self-conscious emotion that arises when affiliation with a collective is appraised as self-relevant and positive. It differs from episodic satisfaction because it reflects self-enhancement tied to the perceived competence, prestige, and moral worth of the focal organization and therefore has more durable motivational consequences for approach and persistence [116]. Social identity and customer–company identification research shows that individuals partly define the self through organizational memberships; when an organization is perceived as attractive, value-congruent, and prestigious, identification strengthens and translates into loyalty intentions and relationship maintenance [117,118]. The group-engagement model further specifies that appraisals of respect, standing, and procedural justice elevate pride and identification, which in turn promote cooperative, relationship-sustaining behavior [119,120]. Service and branding studies identify customer-facing signals of benevolence and respect (responsiveness, accuracy, warmth) and reliable backstage execution (clarity, transparency, fairness, privacy/security) as cues that jointly elicit identification-based pride, which robustly predicts loyalty-type outcomes, including repeat purchase and advocacy [121,122]. Positioned within this literature, pride in membership is theoretically suited to mediate the effects of CSO and ISQ on repeat patronage.

2.7. Trust and Security Awareness

Trust and security awareness refers to customers’ recognition of institutional mechanisms that ensure safe and fair exchange on digital platforms. These mechanisms include buyer protection, secure payment systems, privacy safeguards, and transparent dispute-resolution policies that signal structural assurance and reduce perceived vulnerability in online transactions [81]. In e-commerce, such assurances substitute for interpersonal familiarity by providing impersonal trust cues embedded in the platform architecture. When these cues are salient, customers perceive lower transactional risk and rely less on other diagnostic signals such as interface responsiveness or service reliability [123,124].

Prior studies grounded in structural assurance and perceived risk frameworks show that visible security and privacy controls mitigate uncertainty and increase transaction intentions even when direct service experiences are limited. Structural assurance thus operates as an institutional substitute for relational trust, attenuating the marginal impact of perceived service quality on behavioral intentions [34]. From a fit perspective, strong awareness of trust and security initiatives flattens the behavioral response surface, as customers anchor their confidence in institutional safeguards rather than in incremental improvements of CSO or ISQ. Accordingly, awareness of trust and security initiatives is expected to moderate the CSO–ISQ–repurchase linkage by reducing the sensitivity of repurchase intention to further service enhancements [125].

3. Hypothesis Development

CSO represents the platform’s outward, customer-facing stance that shapes what customers expect at the interface, including prompt and accurate responses and enjoyable, friendly interactions [126]. ISQ reflects backstage capability to deliver reliably through clear communication, efficient and transparent problem solving, fair and timely rewards and benefits, and trustworthy policies for payment, privacy, and returns [127]. In this study, CSO is measured with NEED and ENJOY items, ISQ with communication, support and procedures, rewards and benefits, and policies, and the focal outcome is repurchase intention. Building on fit theory and Expectation–Confirmation logic, we view CSO as the signal that sets expectations and ISQ as the system that fulfills them. When these facets are aligned at the same level, customers receive coherent cues that what is promised will be delivered, uncertainty and attributional conflict are reduced, and approach tendencies toward the next purchase strengthen [25]. Accordingly, we predict a positive slope along the line of congruence where CSO and ISQ rise together.

H1a (fit; line of congruence).

When CSO and ISQ are aligned at the same level, repurchase intention increases as their joint level increases.

Even under alignment, marginal gains should not be constant. Adaptation-level processes shift reference points upward as experience accumulates, multi-attribute utility exhibits saturation as attributes approach high performance, and quality above the zone of tolerance becomes less noticeable [128]. Early improvements in aligned CSO and ISQ remove salient frictions, sharply reducing perceived risk, whereas later improvements address residual irritants with smaller incremental impact on choice. This implies concavity along the congruence path [129].

H1b (diminishing returns under alignment).

When CSO and ISQ are kept equal and are increased together from low through moderate to high levels, repurchase intention rises but at a decreasing rate.

When CSO and ISQ diverge, customers encounter inconsistent cues about value and reliability, which expectancy-violation and fairness–trust perspectives link to negative inferences and erosion of trust. If CSO is high while ISQ is low, the platform appears to over-promise and under-deliver; if CSO is low while ISQ is high, capability is under-signaled and quality gains go under-noticed, so perceived value remains muted. In both cases, cue conflict heightens uncertainty about payment, privacy, logistics, and redress, suppressing willingness to buy again [130,131]. Because inconsistencies are salient and subject to negativity bias, the penalty from misalignment grows more than proportionally as the discrepancy widens. Operationally, this corresponds to the LOIC, where the average level of CSO and ISQ is held constant while their difference increases, and where repurchase should decline [132].

H1c (misfit penalty; line of incongruence).

As the absolute discrepancy between CSO and ISQ increases, with one high while the other is low, repurchase intention decreases.

Pride in membership provides the principal psychological channel linking service cues to behavior [133]. CSO supplies socioemotional cues of respect, warmth, responsiveness, and accurate need recognition that make customers feel valued, while ISQ supplies structural cues of predictability, transparency, and fairness that signal capability [106]. Consistent signals across the interface and the system elevate pride, and pride fosters commitment, motivates self-consistent choice, reduces the attractiveness of alternatives, and ultimately increases the likelihood of buying again beyond any direct utility effects [134].

H2 (mediation via pride).

Pride in membership mediates the effect of CSO and ISQ on repurchase intention, such that higher CSO and ISQ increase pride, and higher pride in turn increases repurchase intention.

Customers also rely on structural assurances that reduce uncertainty at a platform level, including buyer protection and refund guarantees, trusted payment, privacy controls, and visible anti-fraud enforcement [135]. Awareness of these trust and security initiatives is highly diagnostic of transaction safety, and cue-diagnosticity logic holds that a more diagnostic cue reduces the weight placed on partially redundant cues [136]. Because trust and security awareness communicates safety and procedural justice that overlap with what CSO and ISQ also convey, increases in awareness should attenuate the marginal returns to additional improvements in either CSO or ISQ [137]. Geometrically, the response surface linking CSO and ISQ to repurchase becomes flatter as trust and security awareness rises, with smaller slopes and less pronounced curvature [138].

H3 (substitutional moderation by trust and security awareness).

Awareness of the platform’s trust and security initiatives attenuates the marginal, linear and higher-order, effects of CSO and ISQ on repurchase intention, flattening the response surface.

Finally, judgments at the point of choice place greater weight on vivid, temporally proximal cues. CSO directly shapes expectations and affect at the interface, whereas ISQ, although necessary, is partly backstage and becomes most visible when problems occur; once adequacy is met, further ISQ improvements tend to influence intentions indirectly (e.g., through identity) rather than through a large residual direct pull [139]. Consequently, when modeled jointly and accounting for the mediating role of pride, the direct path from CSO to repurchase should exceed the direct path from ISQ.

H4 (relative weight of customer-facing cues).

The direct effect of Customer Service Orientation on repurchase intention is greater than the direct effect of Internal Service Quality.

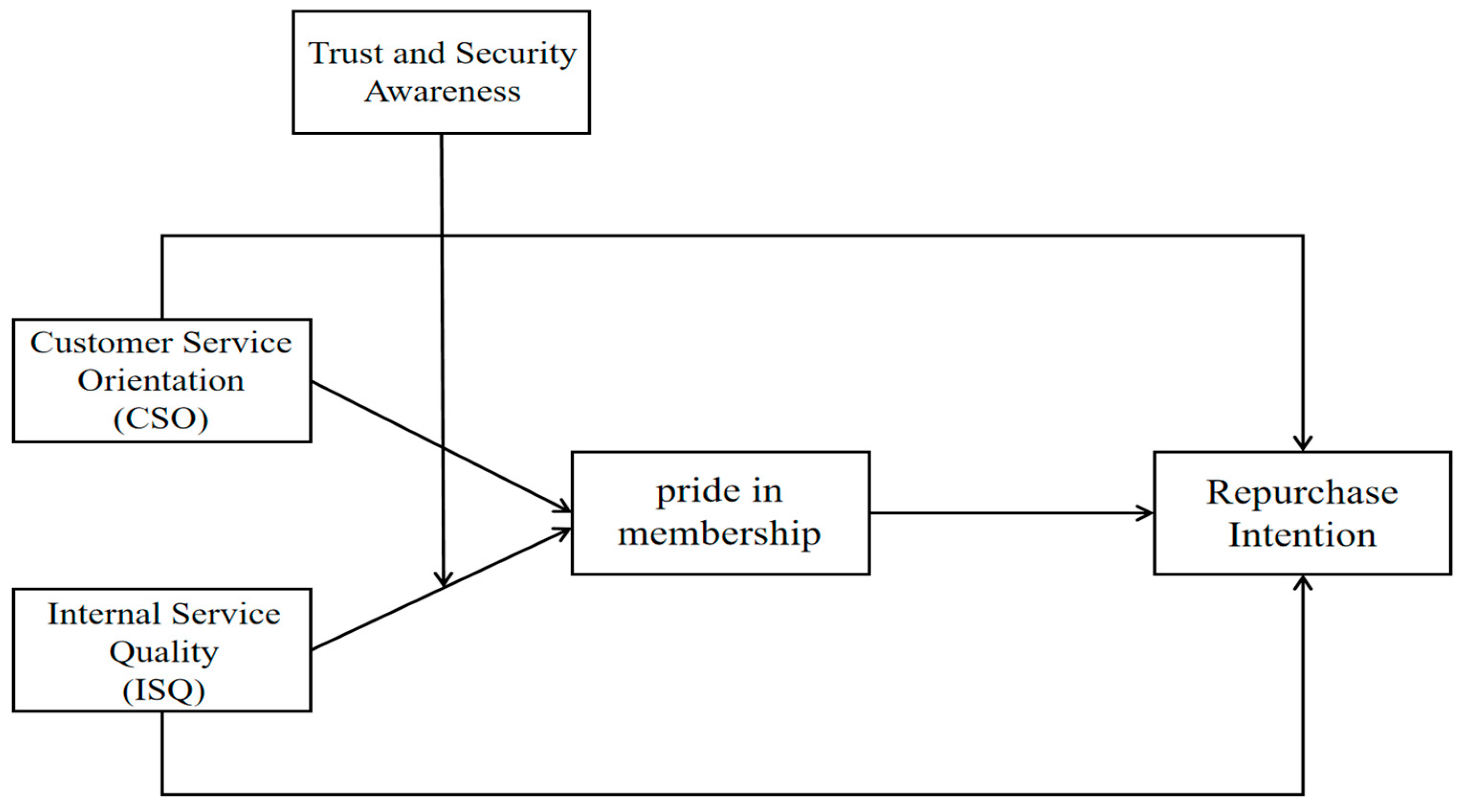

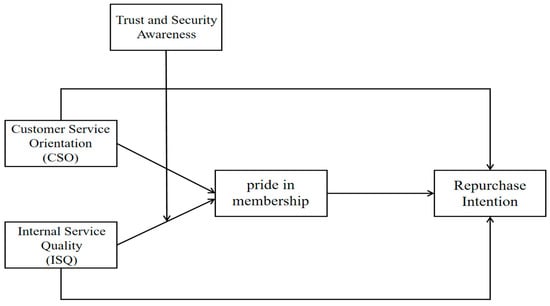

Figure 1 illustrates the structural model depicting the relationships among the variables. In the following section, we describe the measurement model, data, and estimation strategy used to test H1–H4.

Figure 1.

Structural Model of the Relationships among Key Variables.

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Questionnaire Survey

We fielded a cross-sectional online survey to obtain respondent perceptions of customer-facing orientation, internal service quality, pride in membership, trust/security awareness, and repurchase intention on large e-commerce platforms. An online mode was chosen for its reach to active platform users and its fit with device-mediated shopping contexts. To ensure data quality, we implemented standard safeguards: one-response-per-IP filtering and pattern checks for straight-lining/invariant responding. Eligibility was screened with a qualifier (Q1) presented bilingually (English/Chinese): “In the past 6 months, how many of the following platforms have you used for online shopping? (Taobao, Tmall, JD.com, Pinduoduo, Xiaohongshu)” with response options 0/1/2. Respondents selecting “0” were automatically exited and shown: “Thank you for your interest. This survey is limited to users who have used one of the listed platforms in the past 6 months.”

Respondents then indicated the platform they use most often (Q2; five platforms), usage frequency (Q10; four ordered categories), and primary purchase type (Q11; three ordered categories). After exclusions via the Q1 screener and quality checks, the analytic sample comprised N = 605 platform users.

The questionnaire opened with a brief study description and consent statement emphasizing anonymity, confidentiality, and voluntary participation. Eligibility was implicitly established by asking respondents to identify their most-used e-commerce platform and usage frequency; only those reporting current use proceeded to the focal measures. To facilitate comprehension, items were presented in simplified Chinese with English back-translation and reconciliation; final wording was pilot-checked for clarity.

Focal constructs were measured with multi-item Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Customer Service Orientation (CSO) captured customer-facing cues using eight items reflecting Need (prompt, accurate, effective, convenient responses; Q12–Q15) and Enjoy (enjoyable, friendly, pleasant interactions; Q16–Q19). Internal Service Quality (ISQ) assessed backstage execution via four subdimensions—communication/interaction (Q20–Q23), support/problem solving (Q24–Q27), rewards/benefits (Q28–Q30), and policies/procedures (Q32–Q35)—which were combined as a higher-order ISQ construct in structural tests. Pride in membership (Q36–Q39) and trust and security awareness (Q40–Q43) were each measured with four items capturing identification-based affect and awareness of platform-level assurances (e.g., buyer protection, secure payment, privacy controls). Repurchase intention (Q44–Q47) was measured with four items indicating likelihood of buying again from the same platform.

To limit respondent burden, the core instrument was held to roughly 40 substantive items. Scale reliability and validity were assessed prior to hypothesis testing; results are reported in Table 1 and Table 2 (reliability and convergent validity) and summarized discriminant-validity checks are described alongside the structural results. Control variables (Q2 platform dummies, Q10 usage frequency, Q11 purchase type) were included in all regression and RSA models [27].

Table 1.

Reliability of Measures (Cronbach’s α).

Table 2.

Convergent validity summary (all constructs: CR, AVE).

4.2. Credibility and Validity Test

Table 1 indicates that most multi-item measures exhibit satisfactory to excellent internal consistency in our sample. The NEED facet of Customer Service Orientation (CSO) and three Internal Service Quality (ISQ) subscales—communication and interaction, support and problem solving, and rewards and benefits—show alphas in the 0.80–0.90 range, which is generally considered good. The single-factor constructs used downstream as mediator/moderator—pride in membership and trust and security awareness—and the dependent variable, repurchase intention, all exceed 0.90, indicating very high reliability. Two subscales are worth a brief clarification. First, the ENJOY facet of CSO yields α = 0.689, slightly below the conventional 0.70 threshold; given the short length (four items) and its affective breadth, this value is plausible and aligns with the moderate standardized loadings in the CSO CFA. Second, the ISQ policies and procedures subscale has α = 0.588. Because it aggregates heterogeneous content (policy clarity, payment security, privacy, and procedural simplicity), Cronbach’s alpha assumes tau-equivalence and strict unidimensionality, can understate reliability. In our analyses we address this by (i) using ISQ as a higher-order composite formed from multiple subdimensions and (ii) relying on latent-variable estimation (SEM), which relaxes alpha’s assumptions. Overall, the reliability evidence supports the use of these scales in subsequent tests, with caveats for CSO-ENJOY and ISQ-policy handled through the composite ISQ index and latent modeling.

As summarized in Table 2, most multi-item constructs meet conventional benchmarks for convergent validity (CR ≥ 0.70; AVE ≥ 0.50). Specifically, CSO–Need (CR = 0.900, AVE = 0.692) and three ISQ subscales; Communication and Interaction (0.877, 0.641), Support and Problem Solving (0.842, 0.572), and Rewards and Benefits (0.812, 0.591) show satisfactory convergence. The single-factor constructs used as mediator/moderator and the dependent variable, Pride in membership (0.926, 0.759), Trust and security awareness (0.947, 0.817), and Repurchase intention (0.944, 0.808), all exhibit excellent convergent validity.

Two scales fall below the AVE benchmark. The CSO–Enjoy facet has CR = 0.689 and AVE = 0.356, which is consistent with a short, affectively broad subscale that tends to depress internal consistency and shared variance. The ISQ Policies and Procedures subscale (CR = 0.594, AVE = 0.273) aggregates heterogeneous content (policy clarity, payment security, privacy protection), for which AVE—assuming unidimensional, tau-equivalent indicators—can be conservative. At the higher order, the CSO composite performs strongly (CR = 0.922, AVE = 0.856), whereas the ISQ composite shows acceptable reliability with a marginal AVE (CR = 0.755, AVE = 0.473), reflecting the intentional breadth across ISQ subdimensions.

To address these nuances, our main analyses (i) treat CSO and ISQ at the higher-order level so that multiple subdimensions jointly inform each construct, and (ii) rely on latent-variable estimation (SEM) that freely estimates loadings and measurement error rather than relying solely on coefficient thresholds. Robustness checks indicate that the substantive results are unchanged when CSO and ISQ are modeled as higher-order factors versus composites. Overall, the evidence supports the adequacy of the measures for subsequent hypothesis testing (We evaluated discriminant validity with multiple recommended diagnostics for latent-variable models—heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios, Fornell–Larcker checks (√AVE compared to interconstruct correlations), and χ2 difference tests in which latent correlations were constrained to unity (φ = 1). Across these tests, the higher-order constructs used in our structural analyses exhibited adequate discriminant validity. In light of space constraints, detailed matrices and test statistics are not tabulated.).

The sample (N = 605) is overwhelmingly drawn from users who most often shop on Taobao (97.0%), with very small shares for Tmall (0.8%), JD.com (1.2%), Pinduoduo (0.7%), and Xiaohongshu (0.3%). Gender is effectively balanced (51.1% female, 48.9% male). Birth cohorts are well represented across generations—1939–1979 (36.0%), 1980–1996 (31.9%), and 1997–2010 (32.1%)—providing variability in age-related experience with platforms. Educational attainment is relatively high: 74.8% report at least an associate/vocational credential (36.0% associate/vocational, 38.8% bachelor’s, 6.6% master’s or above), with 18.5% high school or below. Personal income spans the distribution, with the largest group in 3000–5999 RMB (42.0%), followed by 6000–8999 RMB (26.3%), ≥9000 RMB (20.7%), and <3000 RMB (11.1%). Respondents are geographically diversified but concentrated in higher-development areas: Tier-2 cities (43.5%), Tier-1 (22.3%), Tier-3 (25.8%), and rural/lower-tier regions (8.4%).

Overall, the data reflect a broad cross-section of active online shoppers, skewed toward the dominant platform (Taobao) and toward urban, higher-education segments of the market. This composition supports external validity for mainstream platform users while also justifying the inclusion of platform, usage, and purchase-type controls in the models to absorb residual heterogeneity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic Summary.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Polynomial Regression Results: Effects of CSO–ISQ Alignment on Repurchase Intention

Table 4 reports the polynomial regression linking Customer Service Orientation (CSO) and Internal Service Quality (ISQ) to repurchase intention, with platform, usage frequency, and purchase type included as controls. The linear terms are positive and significant (CSO = 1.037, p < 0.001; ISQ = 0.368, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of both customer-facing orientation and backstage execution are associated with higher repurchase intentions. The quadratic terms are negative and significant (CSO2 = −0.125, p = 0.037; ISQ2 = −0.237, p = 0.013), implying diminishing returns: as CSO and ISQ become very high, further increases yield smaller incremental gains in repurchase. The CSO × ISQ interaction is not significant (p = 0.532), suggesting that the rising-but-concave shape of the surface is driven by the main and curvature components rather than by a multiplicative synergy near the mean. Together, these coefficients imply a positive slope and concave curvature along the line of congruence (CSO = ISQ), consistent with H1a (alignment raises repurchase) and H1b (diminishing returns under alignment).

Table 4.

Polynomial regression predicting repurchase.

In addition, the combination of curvature terms indicates a penalty as the two attributes diverge (negative curvature along the line of incongruence), aligning with H1c; this pattern is corroborated by the response-surface tests reported in Table 5. Comparing direct effects, the CSO coefficient is larger than the ISQ coefficient (1.037 vs. 0.368), supporting H4 that customer-facing cues exert a stronger direct pull on repurchase than execution cues when both are modeled together. Among controls, the platform indicator shows a small negative effect (p = 0.091), while usage frequency and purchase type are not significant at the 10% level. The model explains a substantial share of variance (R2 = 0.688; Adj. R2 = 0.684), indicating strong overall explanatory power. Consistent with H4, the direct effect of CSO (controlling for pride) exceeded that of ISQ (Wald χ2(1) = 14.81, p < 0.001; c1 = 0.469 vs. c2 = 0.055).

Table 5.

Response-surface tests for repurchase intention (CSO × ISQ).

5.2. Response-Surface Results: Fit, Curvature, and Asymmetry in Repurchase

Table 5 indicates a clear fit pattern in the CSO–ISQ surface for repurchase. First, the slope along the line of congruence is strongly positive (a1 = 1.417, p < 0.001), showing that when CSO and ISQ move together to higher joint levels, repurchase rises—supporting H1a. Second, the curvature on the line of congruence is negative (a2 = −0.260, p < 0.001), implying diminishing returns as aligned performance becomes very high—supporting H1b. Third, the curvature on the line of incongruence is negative (a4 = −0.467, p = 0.057), consistent with a misfit penalty: as the absolute discrepancy between CSO and ISQ grows (one high, the other low), repurchase declines—supporting H1c under the pre-specified 10% criterion.

Beyond these fit/misfit effects, the significant positive value for a3 (0.659, p < 0.001) indicates asymmetry along the incongruence line: for the same absolute gap between CSO and ISQ near their means, outcomes are higher when CSO exceeds ISQ than when ISQ exceeds CSO. This tilt is consistent with the theorized greater direct weight of customer-facing cues—i.e., CSO carries more immediate pull on repurchase than backstage execution when considered at comparable levels—aligning with H4. Finally, the auxiliary surface test (a5 = 0.123, p = 0.051) confirms that the surface departs from a purely additive plane, reflecting the curvature features captured by H1b–H1c.

Table 6 shows that the estimated stationary point of the CSO–ISQ surface lies at CSO = 5.12 and ISQ = 1.87, with a predicted repurchase of 7.81 at that location. Because a2 < 0 (Table 4) and a4 < 0, this stationary point represents a local maximum on a concave surface. Its coordinates lie off the line of congruence (CSO = ISQ) toward the CSO-dominant side (high CSO, low ISQ), which is consistent with the asymmetric tilt reported by a3 > 0 and with H4 (customer-facing cues carry greater direct weight). The absolute predicted level slightly exceeds the observed scale ceiling, a known feature of unconstrained polynomial surfaces; interpretation should therefore focus on location and curvature rather than the raw peak value.

Table 6.

Stationary point, principal axes, and model fit (RSA for repurchase).

The stationary point reported in Table 6 reflects the mathematical optimum of an unconstrained quadratic surface and may therefore fall outside the theoretically plausible range for CSO and ISQ. In polynomial RSA, such stationary points arise from the algebraic form of the quadratic model and are not interpreted substantively. Consistent with RSA methodology, theoretical interpretation should instead focus on the slopes and curvature of the surface, particularly along the congruence and incongruence lines, because these geometric features capture the theorized patterns of fit, diminishing returns, and misfit, whereas the absolute coordinates of the stationary point do not.

The principal-axis estimates indicate the orientation of the ridge. The first axis (p10 ≈ 0, p11 ≈ 0.37, n.s.) suggests that, in the neighborhood of the grand means, the ridge passes near the origin (no meaningful intercept shift) and is shallower than the 45° LOC, implying a modest tilt toward the CSO dimension as one moves along the direction of increasing fit. The second axis (p20 and p21, both n.s.) is roughly orthogonal, indicating no strong evidence of a saddle or rotation that would contradict the concave-fit story. The lateral-shift indices reinforce this picture: C1 ≈ 0 implies negligible local displacement of the ridge away from congruence at the mean levels, whereas C2 ≈ 9.15 reflects displacement along the line of incongruence as one moves away from the mean—again echoing the CSO-tilt captured by a3.

Finally, the full second-order model explains 68.4% of the variance in repurchase (R2 = 0.684, p < 0.001), mirroring the strong fit reported in the polynomial regression (Table 4). Taken together with Table 4, these geometry results substantiate H1a (positive slope under alignment), H1b (concave returns at high alignment), H1c (penalties to misfit), and provide surface-level corroboration for H4 (greater direct pull of CSO).

Table 7 shows that the mediation test supports H2. In an SEM with 5000 bootstrap draws and BCa 95% confidence intervals, CSO and ISQ each positively predicted pride in membership (both p < 0.001), and pride in turn predicted repurchase intention (p < 0.001). The bootstrapped indirect effects from CSO to repurchase and from ISQ to repurchase were both significant and their BCa intervals excluded zero (both p < 0.001), indicating mediation. With pride included, the direct CSO → repurchase path remained significant (partial mediation), whereas the direct ISQ → repurchase path was not significant (p = 0.397), consistent with a primarily mediated effect. Taken together, these results corroborate the theorized identity-based mechanism: coherent service signals elevate pride, which translates into stronger repurchase intentions.

Table 7.

SEM Mediation Results for H2: Paths and Indirect Effects with BCa 95% CIs.

Table 8 provides convergent evidence that awareness of platform level trust and security attenuates the CSO–ISQ effects on repurchase, which matches the flattening predicted in H3. The joint Wald test rejects the null that all moderation terms equal zero (F(5, 587) = 35.131, p < 0.001), indicating that Trust and Security awareness systematically alters the second order CSO–ISQ surface. Directional contrasts show significant attenuation of the LOC slope, since the sum of linear interactions with TRUSTSEC is negative and different from zero (estimate = −0.259, SE = 0.033, z = −7.87, one sided p < 0.001), and significant attenuation of the LOC curvature (sum of second order interaction terms = −0.150, SE = 0.030, z = −4.90, one sided p < 0.001). Taken together, these results imply that when structural assurances are salient, the marginal returns to additional CSO and ISQ improvements diminish and the CSO–ISQ surface becomes less steep and less curved. Therefore H3, the substitutional moderation by trust and security awareness that flattens both the linear and higher order effects, is supported.

Table 8.

Moderation by Trust and Security Awareness (H3): Joint and Contrast Tests.

Table 9 indicates that all hypothesized relationships are supported by the data and hold in the presence of controls. First, the fit logic is confirmed. Along the line of congruence, repurchase rises with the joint level of CSO and ISQ (H1a), and the relationship is concave, consistent with diminishing returns at high aligned levels (H1b). Along the line of incongruence, curvature is negative, indicating a penalty when one facet is high and the other is low (H1c). Second, the mechanism and boundary condition behave as theorized. Pride in membership mediates the effects of CSO and ISQ on repurchase (H2), and trust and security awareness acts as a substitutional moderator that flattens both the slope and the curvature of the CSO–ISQ surface (H3). Third, when CSO and ISQ are modeled jointly, the direct effect of CSO on repurchase exceeds that of ISQ (H4), consistent with the stronger immediate influence of customer-facing cues at the point of choice. Taken together, these results validate a fit-based account in which aligned interface signals and execution systems most strongly promote repeat patronage, with identity-based pride carrying much of the effect and platform-level assurances reducing the incremental value of further service enhancements.

Table 9.

Summary of Hypothesis Testing.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

This study examined how customer-facing orientation (CSO) and backstage execution (ISQ) jointly shape repurchase intention on large e-commerce platforms. Results from polynomial and response-surface analyses support a fit-based explanation rather than a simple additive one. Repurchase increases when CSO and ISQ rise together, but the gain tapers at high joint levels, and repurchase declines when they diverge. These geometric patterns, including the positive slope and concave curvature along the line of congruence and the negative curvature along the line of incongruence, are consistent with the idea that expectations formed at the interface are confirmed or disconfirmed by the system behind it. Taken together, results reinforce the fit-based theory of digital service, illustrating that customer outcomes in e-commerce platforms emerge not from the absolute level of service quality or orientation, but from their systemic alignment that creates coherence and reduces uncertainty in value realization.

The findings also suggest how service cues translate into behavior. Pride in membership mediates the pathway from CSO and ISQ to repurchase, consistent with an identification mechanism in which coherent signals of respect, responsiveness, competence, and fairness enhance pride and in turn encourage repeat purchasing. At the same time, awareness of trust and security initiatives acts as a structural assurance that reduces the diagnostic weight consumers place on other service cues. When such assurance is salient, the slopes and curvatures on the CSO–ISQ surface become flatter. Therefore, trust and security awareness do not replace service quality but moderate how strongly marginal improvements in CSO or ISQ influence repurchase intention.

Another pattern concerns the relative salience of interface and system cues. In the joint model, CSO has a stronger direct effect on repurchase than ISQ, which is consistent with the temporal proximity and vividness of customer-facing signals at the point of choice. However, this advantage coexists with penalties to misfit and diminishing returns when alignment is already high. Execution quality remains essential for interface promises to translate into sustained behavioral effects.

Methodologically, estimating the full second-order response surface proved crucial. This approach separates level from discrepancy, captures asymmetry when CSO exceeds ISQ versus the reverse, and provides concise tests of fit, misfit, and attenuation under structural assurance.

Taken together, the findings present a coherent picture. Repeat patronage peaks when what the platform signals and what it can deliver are aligned. The benefits of alignment level off at high joint levels, while incoherence is costly. Identity-based pride carries much of the effect, and visible assurances of safety temper the incremental payoff from further service enhancements. While this study does not employ service blueprinting empirically, the concept provides a useful visualization tool for future research and managerial practice to map CSO–ISQ coordination in platform ecosystems.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to developing a fit-based theoretical account of digital service by linking what a platform signals at the interface (CSO) to what its system can reliably deliver behind the interface (ISQ). Empirically, this linkage was confirmed through polynomial regression and response-surface analysis (Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6), which jointly revealed a positive slope and concave curvature along the line of congruence, providing direct evidence of fit-based performance predicted by theory. Rather than treating service elements as additive drivers, we find that outcomes depend on their alignment. The positive slope and concave curvature along the line of congruence help explain how confirmation may operate when signals and systems rise together: expectations are met, risk falls, and gains taper at high levels as a zone of tolerance is reached. The negative curvature along the line of incongruence helps describe how mismatches between promise and system performance create cue conflict and depress intentions. This geometric account clarifies why “more of one” cannot fully compensate for “less of the other,” which extends classic fit theory to digitally mediated exchange.

Second, the results integrate Expectation–Confirmation logic with a configurational view of service quality. Mapping the response surface to EC mechanisms, the locus of confirmation corresponds to the congruence path, while disconfirmation corresponds to the incongruence path. The evidence that benefits taper at high joint levels provides a structural explanation for diminishing sensitivity, while the penalty to misfit captures the salience and asymmetry of negative information. In doing so, the findings knit together service quality, EC theory, and fit theory within a single empirical geometry.

Third, we identify pride in membership as a central psychological channel from service design to behavior. Prior work often emphasizes satisfaction or trust as the dominant mediators. By showing that coherent interface and system cues elevate identification-based pride, which then increases repurchase, we add an identity lens to the service quality literature. Pride captures self-relevant benefits of affiliating with a competent, fair, and caring platform and explains why aligned signals have effects that persist beyond immediate utilitarian gains.

Fourth, we propose and test a substitutional boundary condition: awareness of trust and security initiatives flattens both the slope and the curvature of the CSO–ISQ surface. This extends structural-assurance and cue-diagnosticity arguments by specifying how a highly diagnostic platform-level cue changes the marginal value of other cues. In other words, visible buyer protection, secure payment, and privacy controls reduce the inferential load placed on CSO and ISQ, so additional improvements in those dimensions yield smaller returns. This substitution logic helps reconcile mixed findings in prior work about the size of service-quality effects in high-assurance settings.

Fifth, the asymmetry we recover, with outcomes higher when CSO exceeds ISQ than when ISQ exceeds CSO at comparable gaps, sharpens theory about cue salience at the point of choice. CSO is temporally proximal and vivid in the purchase episode, while ISQ is partly backstage and becomes salient when problems arise. The larger direct effect of CSO in joint models is therefore theoretically consistent with attentional and accessibility accounts, without diminishing the necessity of strong execution to sustain repeat behavior.

Finally, the study contributes methodologically. Estimating the full second-order surface and testing slopes and curvatures along theoretically meaningful lines separate level from discrepancy, avoid the biases of difference scores, and helps reveal geometric features that additive models obscure. Extending this approach with a moderator that systematically flattens the surface shows how fit logics can incorporate boundary conditions in a principled way. Together, these contributions suggest a general template for theorizing digital service: specify complementary interface and system cues, test their alignment and misalignment on a surface, identify the psychological carrier of effects, and model structural assurances that modulate the surface itself.

6.3. Practical Implications

The findings indicate that service improvement should be managed as a problem of alignment between customer-facing signals and executional capability rather than as a pursuit of maximal scores on isolated dimensions. As summarized in Table 9, all four hypotheses (H1a–H4) converge on the same managerial principle: optimizing the CSO–ISQ fit yields higher repurchase intention than maximizing either dimension independently. Repurchase is highest when Customer Service Orientation (CSO) and Internal Service Quality (ISQ) rise together, which implies cross-functional governance that links product, customer experience, operations, risk, and policy so that promises at the interface are matched by deliverable processes. In practice, organizations can institutionalize joint objectives for customer service and operations, blueprint end-to-end journeys, and use release gates that withhold new CSO features or copy until refund logic, claim handling, and policy text have been updated and verified.

The response surface exhibits concavity along the line of congruence, so marginal returns diminish at higher joint levels. Budgeting should therefore prioritize closing gaps and lifting both CSO and ISQ from low to moderate levels before attempting costly refinements at the top end. Once both are strong, investments that reduce variance typically yield greater impact than additional interface embellishment. Clearer policy language, tighter service-level agreements, faster refund settlement, and fewer handoffs are examples of variance-reduction levers. The documented penalty for incongruence cautions against over-promising: acceleration of reply speed or a warmer tone without resolving backstage lags is likely to depress intentions. Governance rules that prohibit promises exceeding operational capability are warranted for macros, chatbot scripts, and marketing copy.

The estimated asymmetry and the larger direct coefficient on CSO indicate that interface cues have greater immediate influence at the point of choice. This suggests a practical rule: raise the ISQ floor to the CSO ceiling. Communication clarity, problem-resolution pathways, rewards and benefits logic, and policy and returns should be at least as robust as customer-facing claims. In marketplace settings this extends to merchant management through the enforcement of seller service standards, standardized return windows, and the elevation of trustworthy sellers based on verifiable performance.

The implications of CSO–ISQ alignment may differ across types of e-commerce platforms. For service-oriented platforms, customer experience is shaped by real-time interactions and immediate service recovery. Here, ensuring that internal service processes match frontline promises is critical, as any CSO–ISQ gap becomes instantly apparent to customers. In contrast, product-oriented platforms rely more on logistics reliability, return handling, and policy transparency. For these platforms, consistent back-end operations and structural assurances (e.g., delivery guarantees, refund efficiency) are more crucial for sustaining trust. Managers should therefore align internal and external service standards according to the dominant value logic of their platform.

Pride in membership emerges as a central psychological carrier of repeat purchase. Platforms can cultivate pride by making competence, fairness, and care visible, for example, through transparent case timelines, proactive status updates, recognition of tenure, and equitable benefit rules that are easy to understand. These cues should signal respect and procedural justice as well as utility.

Awareness of trust and security initiatives attenuates both the slope and curvature of the CSO–ISQ surface. This supports investment in clear and low-friction assurances such as buyer protection, secure payment badges, and transparent privacy controls. Assurances should be visible at key decision points and written in plain language, with defaults set to secure options, while avoiding communications that prime risk. Where assurance is already salient, marginal resources can be reallocated from polishing high CSO or ISQ scores toward reliability improvements or identity-building features that strengthen pride.

Finally, managers should measure and manage alignment directly. A fit index that pairs external CSO indicators (for example, response latency, accuracy, first-contact resolution, and tone) with internal ISQ indicators (for example, refund cycle time, claim touchpoints, policy readability, and chargeback rate) can be tracked over time. Applying response-surface diagnostics to operational data helps prioritize interventions where diminishing returns are binding or where gaps between CSO and ISQ are widest.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study relies on cross-sectional, self-report data, which limits causal inference and raises the possibility of common-method variance. Future research can pair our survey measures with behavioral traces from platforms such as actual repurchase, refund events, and ticket logs and can use longitudinal or experimental designs that manipulate CSO–ISQ alignment to identify dynamic and causal effects.

Measurement quality is uneven across a few subscales, particularly the CSO-Enjoy and ISQ-Policy facets that showed lower AVE. Because the AVE values for these two facets fall below recommended thresholds, they may introduce measurement noise, underscoring the need to further refine these scales to improve their reliability. Subsequent work can refine these instruments by expanding item pools, using item-response or bifactor modeling to separate general and facet variance, and triangulating survey responses with unobtrusive indicators, for example, NLP-based ratings of conversational tone for CSO and operational metrics for policy clarity and refund handling for ISQ.

External validity is constrained by the single-country context and the heavy concentration of respondents on one platform. In addition, because the sample is heavily dominated by Taobao users, the estimated RSA surface and moderation effects may partly reflect platform-specific design characteristics. Future research should validate the model across multiple platforms or cross-country contexts to assess the generalizability of the CSO–ISQ alignment effects. Replication across markets, platform types, and product categories can test whether the geometry of the CSO–ISQ surface is stable or shifts with institutional environments, competitive intensity, and category risk, and can examine whether platform design choices or governance regimes alter fit effects. Although the sample is dominated by users of a single platform, this pattern reflects the structure of China’s e-commerce market, where one leading platform accounts for a substantial share of national online transactions. As the study focuses on large, general-purpose e-commerce ecosystems, the findings capture mechanisms that are typical of such platforms. Nevertheless, future research should validate the robustness of the CSO–ISQ alignment effects across other major platforms and in service-oriented contexts to strengthen external validity.

Although purchase type was included as a control variable in all models (see Table 4) and showed no significant effect, our sample primarily reflects product-oriented contexts. Future research could replicate these analyses in service-heavy platforms to assess whether similar alignment effects hold.

The response surface is modeled as a second-order polynomial, which is a disciplined but parametric approximation. Future studies can probe for thresholds, kinks, or regime changes using spline-based RSA, Gaussian-process surfaces, or machine-learning approximations, and can compare these to the polynomial benchmark to assess whether diminishing returns and misfit penalties remain after relaxing functional-form assumptions.

Unobserved confounding and endogeneity remain possible if factors that influence both service design and repurchase are omitted. Designs that exploit exogenous shocks (for example, policy rollouts, payment-security upgrades, or operational outages), instrumental-variables strategies, or difference-in-differences around staged process changes can strengthen identification of CSO, ISQ, and assurance effects.

The boundary conditions examined focus on trust and security awareness, and the mediator emphasizes pride in membership. Future research can broaden the mechanism and moderation space by testing sequential or competing mediators such as satisfaction, perceived value, habit, and risk, and by assessing moderators like price promotions, membership tier, relationship length, or marketplace heterogeneity using multilevel models that nest customers within sellers and platforms.

Finally, the outcome is repurchase intention, which is theoretically proximal yet not equivalent to realized behavior. Linking the modeled surface to revealed retention, repeat purchase frequency, basket value, and churn, ideally in field experiments that vary CSO signals and ISQ processes in coordinated releases, would establish whether the documented alignment logic translates into durable behavioral lift.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.S. and J.M.K.; methodology, S.P.S. and J.M.K.; software, S.P.S. and J.M.K.; validation, S.P.S. and J.M.K.; formal analysis, J.M.K.; investigation, S.P.S.; resources, S.P.S.; data curation, R.K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.S. and J.M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.P.S., R.K.M. and J.M.K.; visualization, S.P.S.; supervision, J.M.K.; project administration, J.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wenzhou-Kean University (protocol code WKUIRB2025-85 and date of approval 3 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSO | Customer Service Orientation |

| ISQ | Internal Service Quality |

| RSA | response-surface analysis |

| LOC | Line of Congruence |

| LOIC | Line of Incongruence |

| EC | Expectation–Confirmation |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| BCa | Bias-Corrected and Accelerated |

| CIs | Confidence Intervals |

| TRUSTSEC | Trust and Security Awareness |

References

- Teo, S.C.; Cheng, K.M.; Chow, M.M. Unlocking repurchase intentions in e-commerce platforms: The impact of e-service quality and gender. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2471535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighomereho, S.O.; Ojo, A.A.; Omoyele, S.O.; Olabode, S.O. From service quality to e-service quality: Measurement, dimensions and model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Kowalkowski, C. Customer-focused and service-focused orientation in organizational structures. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Customer orientation: A literature review based on bibliometric analysis. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Kassemeier, R.; Alavi, S.; Haaf, P.; Schmitz, C.; Wieseke, J. When do customers perceive customer centricity? The role of a firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2020, 40, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushko, R.J.; Tabas, L. Designing service systems by bridging the “front stage” and “back stage”. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2009, 7, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donavan, D.T.; Hocutt, M.A. Customer evaluation of service employee’s customer orientation: Extension and application. J. Qual. Manag. 2001, 6, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-Dominant Logic 2025. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanefo, C.; Grobbelaar, S. Evolutionary Dynamics of Digital Platform Ecosystems in Healthcare: A Case Study of the Discovery Ecosystem in South Africa. Electron. Mark. 2025, 35, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulfert, T.; Woroch, R.; Strobel, G. Follow the Flow: An Exploratory Multi-Case Study of Value Creation in E-Commerce Ecosystems. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, A.; Raziq, M.M.; Malik, O.F.; Malik, S.A.; Khurshid, N. Value Co-Creation through Actor Embeddedness and Actor Engagement. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Wamba, S.F.; D’Ambra, J. Enabling a transformative service system by modeling quality dynamics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 207, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Morgan, F.N. Service Blueprinting: A Practical Technique for Service Innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.-H.; Lim, C.; Kim, K.-J. Development of a Service Blueprint for the Online-to-Offline Integration in Service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phamthi, V.A.; Nagy, Á.; Ngo, T.M. The influence of perceived risk on purchase intention in e-commerce—Systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, R.T. Exploring the Effects of E-Service Quality and E-Trust on Consumers’ E-Satisfaction and Tokopedia’s E-Loyalty: Insights from Gen Z Online Shoppers. Int. J. Digit. Mark. Sci. 2025, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, P.; Li, Z.; Mensah, I.A.; Omari-Sasu, A.Y. Consumer Response to E-Commerce Service Failure: Leveraging Repurchase Intentions through Strategic Recovery Policies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, A.; Luchs, R.; Min, X. The Role of Refund Policy and Complaint Response Time in Determining Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intent. J. Appl. Mark. Theory 2010, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M. Misalignment and Its Influence on Integration Quality in Multichannel Services. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Sun, H.; McCole, P.; Ramsey, E.; Lim, K.H. Trust, Satisfaction and Online Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Perceived Effectiveness of E-commerce Institutional Mechanisms. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]