Study on Livestreaming Shopping Behavior of the Elderly Based on SOR Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Livestreaming Shopping

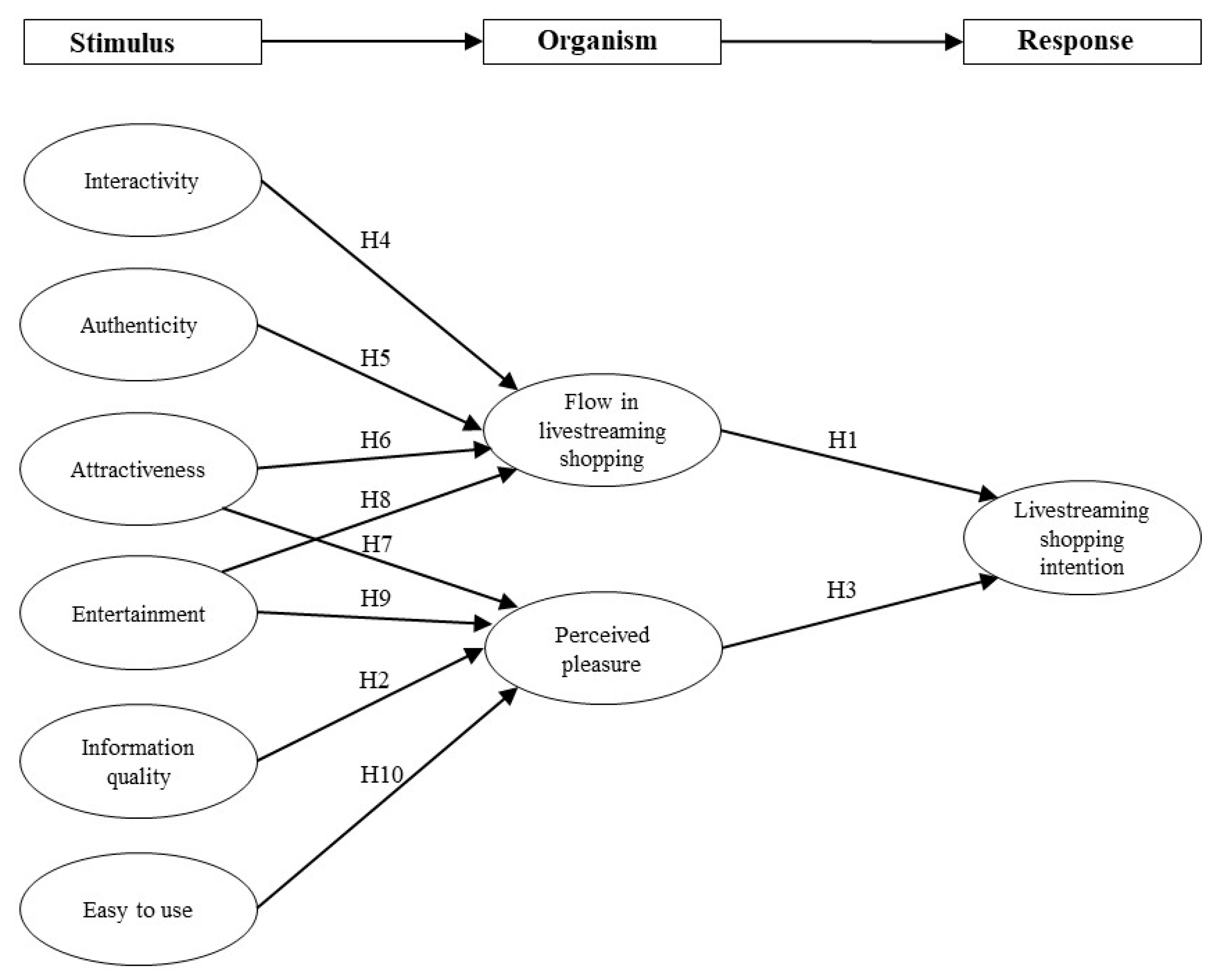

2.2. SOR Theory

2.3. Flow Theory

2.4. ISSM

2.5. Perceived Pleasure

2.6. External Stimulating Factors

2.6.1. Interactivity

2.6.2. Authenticity

2.6.3. Attractiveness

2.6.4. Entertainment

2.6.5. Easy to Use

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Samples

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Analytical Method

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Results of Hypothesis Validation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Contribution

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Contribution

6.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2.2. Practice Implications

6.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, K.; Liu, L.; Liu, C. Consumers’ impulsive purchase intention from the perspective of affection in live streaming e-commerce. China Bus. Mark. 2022, 36, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, J.; Jianqiu, Z.; Bilal, M.; Akram, U.; Fan, M. How social presence influences impulse buying behavior in live streaming commerce? The role of SOR theory. Int. J. Web Inf. Syst. 2021, 17, 300–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.; Lu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, W. The dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behavior through tie strength: Evidence from live streaming commerce platforms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. What drives live-stream usage intention? The perspectives of flow, entertainment, social interaction, and endorsement. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L. How to retain customers: Understanding the role of trust in live streaming commerce with a socio-technical perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.S.; Zhang, J. Tourism e-commerce live streaming: Identifying and testing a value-based marketing framework from the live streamer perspective. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 51th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Liu, M.T. Investigating the live streaming sales from the perspective of the ecosystem: The structures, processes and value flow. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1157–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Dhall, K.; Muthu Kumar, M.; Jain, R. Value e-Commerce: The Next Big Leap in India’s Retail Market. Available online: https://www.kearney.com/consumer-retail/article/?/a/value-ecommerce-the-next-big-leap-in-india-retail-market (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Ma, Y. To shop or not: Understanding Chinese consumers’ live-stream shopping intentions from the perspectives of uses and gratifications, perceived network size, perceptions of digital celebrities, and shopping orientations. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101562. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.-W.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Qin, J. An empirical study on impulse consumption intention of livestreaming e-commerce: The mediating effect of flow experience and the moderating effect of time pressure. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 8719. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, T.; Wei, S.; Anaza, N.A. Livestreaming vs. pre-recorded: How social viewing strategies impact consumers’ viewing experiences and behavioral intentions. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 2075–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, K. The Determinants of Purchase Intention on Agricultural Products via Public-Interest Live Streaming for Farmers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qin, F.; Wang, G.A.; Luo, C. The impact of live video streaming on online purchase intention. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 656–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, H. Influence of Perceived Value on Consumers’ Continuous Purchase Intention in Live-Streaming E-Commerce—Mediated by Consumer Trust. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Law, M.; Lam, L.; Cui, C. A study of the factors influencing the viewers’ satisfaction and cognitive assimilation with livestreaming commerce broadcast in Hong Kong. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 23, 1565–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Chandra, B. Digital immigrants versus digital natives: Decoding their e-commerce adoption behavior. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241282437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, P.; Yue, Z.; Ren, Q.; Yan, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, C.; Hao, Y. Internet-based healthcare services use patterns and barriers among middle-aged and older adults in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. Volume II: Demographic Profiles. Available online: http://esa.un.org/WPP/ (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2022 the National Economy Will Rise to a New Level Despite the Pressure. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901709.html (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Cai, F.; Wang, D. Demographic Transition: Implications for Growth. China Boom Its Discontents 2005, 34, 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Guner, H.; Acarturk, C. The use and acceptance of ICT by senior Citizens: A comparison of technology acceptance model (TAM) for elderly and young adults. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Wood, D.; Ysseldyk, R. Online social networking and mental health among older adults: A scoping review. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Vieil. 2022, 41, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnes, M.; Løe, I.-C.; Kalseth, J. Exploring the impact of information and communication technologies on loneliness and social isolation in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Jung, Y. The common sense of dependence on smartphone: A comparison between digital natives and digital immigrants. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 1236–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, J.; Yu, H. The double-edged sword of internet use in China’s aging population: Thresholds, mediation and digital health policy. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1643510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, I.; Kampf, R. Digital nativity and digital diplomacy: Exploring conceptual differences between digital natives and digital immigrants. Glob. Policy 2022, 13, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral-Peral, B.; Villarejo-Ramos, Á.F.; Arenas-Gaitán, J. Self-efficacy and anxiety as determinants of older adults’ use of Internet Banking Services. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R. Live streaming in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq Obeidat, M.; Young, W.D. An assessment of the recognition and use of online shopping by digital immigrants and natives in India and China. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Dubinsky, A.J.; Anderson, R.E. Leadership style, motivation and performance in international marketing channels: An empirical investigation of the USA, Finland and Poland. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 50–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, R.J.; Rossiter, J.R. Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology. In Retailing: Critical Concepts. 3, 2. Retail Practices and Operations; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002; Volume 2, p. 77p. [Google Scholar]

- Engeser, S.; Rheinberg, F. Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, H. User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Du, Z.; Yuan, R.; Miao, Q. Short-term or long-term cooperation between retailer and MCN? New launched products sales strategies in live streaming e-commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102996. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C. Way to success: Understanding top streamer’s popularity and influence from the perspective of source characteristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q. The effects of tourism e-commerce live streaming features on consumer purchase intention: The mediating roles of flow experience and trust. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 995129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology Cambridge; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Liu, C.; Shi, R. How Do Fresh Live Broadcast Impact Consumers’ Purchase Intention? Based on the SOR Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Parasuraman, A.; Grewal, D.; Voss, G.B. The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, F. Website attributes in urging online impulse purchase: An empirical investigation on consumer perceptions. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, K. How live streaming features impact consumers’ purchase intention in the context of cross-border E-commerce? A research based on SOR theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 767876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.; Yun, Y. Toward a more robust usability concept with perceived enjoyment in the context of mobile multimedia service. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2010, 1, 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.C.; Kang, I.; McKnight, D.H. Transfer from offline trust to key online perceptions: An empirical study. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2007, 54, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, H.; Thavisay, T.; Lee, S.H. Enhancing the role of flow experience in social media usage and its impact on shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Cui, B.-J.; Lyu, B. Influence of streamer’s social capital on purchase intention in live streaming E-commerce. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Bai, X. Online consumer behaviour and its relationship to website atmospheric induced flow: Insights into online travel agencies in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadă, D.R. Flow theory and online marketing outcomes: A critical literature review. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 6, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Khan, A. The students’ flow experience with the continuous intention of using online English platforms. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 807084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Lu, M. The empirical research on impulse buying intention of live marketing in mobile internet era. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Lee, H. Exploring user acceptance of streaming media devices: An extended perspective of flow theory. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2018, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Chiu, M.-L.; Chen, K.-W. Defining the determinants of online impulse buying through a shopping process of integrating perceived risk, expectation-confirmation model, and flow theory issues. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, S. How background visual complexity influences purchase intention in live streaming: The mediating role of emotion and the moderating role of gender. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, S. A contextual perspective on consumers’ perceived usefulness: The case of mobile online shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J. What drives consumers’ mobile shopping? 4Ps or shopping preferences? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Chen, R.J. The influence of the frequency of the internet use on the behavioral relationship model of the mobile device-based shopping. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Cai, J. How attachment affects user stickiness on live streaming platforms: A socio-technical approach perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.; Jo, H.S. What quality factors matter in enhancing the perceived benefits of online health information sites? Application of the updated DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 137, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.J.; Hsu, M.K.; Klein, G.; Lin, B. E-commerce user behavior model: An empirical study. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2000, 19, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Gull, N. The Influence of Short Video Platform Characteristics on Users’ Willingness to Share Marketing Information: Based on the SOR Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, X.Y.; Rahman, M.K.; Mamun, A.A.; A. Salameh, A.; Wan Hussain, W.M.H.; Alam, S.S. Predicting the intention and adoption of mobile shopping during the COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221095012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.R.; Steinberg, J.; Grev, R. Wanting to and having to help: Separate motivations for positive mood and guilt-induced helping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J.; Twyman, N.; Hammer, B.; Roberts, T. Taking ‘fun and games’ seriously: Proposing the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM). J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 14, 617–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, M.; Sohn, S. Understanding the consumer acceptance of mobile shopping: The role of consumer shopping orientations and mobile shopping touchpoints. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2021, 31, 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, J.Y.; Hong, S.-J.; Tam, K.Y. The effects of post-adoption beliefs on the expectation-confirmation model for information technology continuance. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaq, A.; Ahmed, E. Digital commerce in emerging economies: Factors associated with online shopping intentions in Pakistan. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2015, 10, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jin Ma, Y.; Park, J. Are US consumers ready to adopt mobile technology for fashion goods? An integrated theoretical approach. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 13, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.; Jung, C.; Kim, H.; Jung, J. Impact of viewer engagement on gift-giving in live video streaming. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M.T. Celebrity endorsement in marketing from 1960 to 2021: A bibliometric review and future agenda. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.K.; McLelland, M.A.; Wallace, L.K. Brand avatars: Impact of social interaction on consumer–brand relationships. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-L.; Hsu Liu, F. Formation of augmented-reality interactive technology’s persuasive effects from the perspective of experiential value. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z. Reversibility between ‘cocreation’and ‘codestruction’: Evidence from Chinese travel livestreaming. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souki, G.Q.; Chinelato, F.B.; Gonçalves Filho, C. Sharing is entertaining: The impact of consumer values on video sharing and brand equity. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengjun, L.; Lun, M.; Siyun, C.; Kun, D. Study on the influence and mechanism of online celebrity live streaming on consumers’ purchase intention. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Fan, W.; Zhou, M. Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, D.V.; Valacich, J.S.; Wells, J.D. The influence of website characteristics on a consumer’s urge to buy impulsively. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.P.; Baptista, P.d.P. Influencers’ intimate self-disclosure and its impact on consumers’ self-brand connections: Scale development, validation, and application. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lee, M.K.; Zhao, D. Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behavior on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Chen, W.; Lal Dey, B. The importance of enhancing, maintaining and saving face in smartphone repurchase intentions of Chinese early adopters: An exploratory study. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelaar, T.; Chang, S.; Lancendorfer, K.M.; Lee, B.; Morimoto, M. Effects of media formats on emotions and impulse buying intent. J. Inf. Technol. 2003, 18, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, J. Antecedents of viewers’ live streaming watching: A perspective of social presence theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-L. Linear Model Predictive Control for Physical Attractiveness and Risk: Application of Cosmetic Medicine Service. Mathematics 2020, 8, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.-M. What online game spectators want from their twitch streamers: Flow and well-being perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Empirical testing of a model of online store atmospherics and shopper responses. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, J.A. Flow in human-computer interactions: Test of a model. In Human Factors in Information Systems: Emerging Theoretical Bases; Ablex Publishing Corp.: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Huang, L. Consumer acceptance of mobile payment across time: Antecedents and moderating role of diffusion stages. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1761–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X. How to use live streaming to improve consumer purchase intentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzam, A.F.M.; Fattah, M. Evaluating effect of social factors affecting. consumer behavior in purchasing home furnishing products in Jordan. Br. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 2, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Monsuwé, T.P.; Dellaert, B.G.; De Ruyter, K. What drives consumers to shop online? A literature review. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, S.; Rashid, R.M. Changing Trends of Consumers’ Online Buying Behaviour During COVID-19 Pandemic with Moderating Role of Payment Mode and Gender. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of Behavioral Research; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Chen, J.; Liao, J.; Hu, H.-L. What motivates users’ viewing and purchasing behavior motivations in live streaming: A stream-streamer-viewer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J. A study on the effect of web live broadcast on consumers’ willingness to purchase. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, M.X. The influences of livestreaming on online purchase intention: Examining platform characteristics and consumer psychology. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 862–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, R.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y. Exploring how live streaming affects immediate buying behavior and continuous watching intention: A multigroup analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. Understanding Chinese consumer adoption of apparel mobile commerce: An extended TAM approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saprikis, V.; Markos, A.; Zarmpou, T.; Vlachopoulou, M. Mobile shopping consumers’ behavior: An exploratory study and review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Nie, K. How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: An IT affordance perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, T.; Balasubramanian, S.A.; Kasilingam, D.L. The moderating role of device type and age of users on the intention to use mobile shopping applications. Technol. Soc. 2018, 53, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, C.P. The influence of webcast characteristics on consumers’ purchase intention under e-commerce live broadcasting mode—The mediating role of consumer perception. China Bus. Mark. 2021, 35, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Guan, Z.; Li, B.; Chong, A.Y.L. Factors influencing people’s continuous watching intention and consumption intention in live streaming: Evidence from China. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Items | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 159 | 47.2 |

| Female | 178 | 52.8 | |

| Age | 60~69 years old | 151 | 44.8 |

| 70~79 years old | 134 | 39.8 | |

| ≥80 years old | 52 | 15.4 | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 176 | 52.2 |

| Senior high school | 135 | 40.1 | |

| Graduate and above | 26 | 7.7 | |

| Nearly three years of livestreaming shopping experience | 1~9 times | 135 | 40.1 |

| 10~19 times | 111 | 32.9 | |

| 20~29 times | 70 | 20.8 | |

| ≥30 times | 21 | 6.2 |

| Constructs | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractiveness | 0.851 | 0.780 | 0.869 | 0.690 |

| 0.748 | ||||

| 0.887 | ||||

| Authenticity | 0.777 | 0.797 | 0.879 | 0.708 |

| 0.883 | ||||

| 0.861 | ||||

| Easy to use | 0.906 | 0.891 | 0.931 | 0.817 |

| 0.875 | ||||

| 0.930 | ||||

| Entertainment | 0.893 | 0.892 | 0.933 | 0.823 |

| 0.911 | ||||

| 0.918 | ||||

| Flow in livestreaming shopping | 0.911 | 0.915 | 0.940 | 0.797 |

| 0.910 | ||||

| 0.890 | ||||

| 0.859 | ||||

| Information quality | 0.928 | 0.908 | 0.922 | 0.748 |

| 0.888 | ||||

| 0.736 | ||||

| 0.895 | ||||

| Interactivity | 0.614 | 0.809 | 0.854 | 0.598 |

| 0.834 | ||||

| 0.861 | ||||

| 0.762 | ||||

| Livestreaming shopping intention | 0.863 | 0.765 | 0.863 | 0.680 |

| 0.879 | ||||

| 0.722 | ||||

| Perceived pleasure | 0.913 | 0.899 | 0.930 | 0.771 |

| 0.932 | ||||

| 0.892 | ||||

| 0.766 |

| Constructs | Attractiveness | Authenticity | Easy to Use | Entertainment | Flow in Livestream Shopping | Information Quality | Interactivity | Livestreaming Shopping Intention | Perceived Pleasure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractiveness | 0.830 | ||||||||

| Authenticity | 0.498 | 0.842 | |||||||

| Easy to use | −0.076 | −0.093 | 0.904 | ||||||

| Entertainment | 0.377 | 0.370 | −0.045 | 0.907 | |||||

| Flow in livestream shopping | 0.345 | 0.337 | 0.015 | 0.362 | 0.893 | ||||

| Information quality | 0.015 | −0.054 | −0.004 | −0.119 | −0.079 | 0.865 | |||

| Interactivity | 0.145 | 0.367 | −0.032 | 0.309 | 0.237 | −0.054 | 0.773 | ||

| Livestreaming shopping intention | 0.325 | 0.452 | 0.011 | 0.418 | 0.423 | −0.088 | 0.308 | 0.825 | |

| Perceived pleasure | 0.387 | 0.347 | −0.094 | 0.438 | 0.397 | −0.063 | 0.265 | 0.486 | 0.878 |

| Hypothesis | Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Flow in livestreaming shopping → Livestreaming shopping intention | 0.273 | 0.055 | 4.927 | *** | Supported |

| H2: Information quality → Perceived pleasure | −0.028 | 0.075 | 0.365 | 0.715 | Not supported |

| H3: Perceived pleasure → Livestreaming shopping intention | 0.378 | 0.057 | 6.651 | *** | Supported |

| H4: Interactivity → Flow in livestreaming shopping | 0.096 | 0.047 | 2.050 | * | Supported |

| H5: Authenticity → Flow in livestreaming shopping | 0.130 | 0.065 | 1.992 | * | Supported |

| H6: Attractiveness → Flow in livestreaming shopping | 0.186 | 0.067 | 2.777 | ** | Supported |

| H7: Attractiveness → Perceived pleasure | 0.257 | 0.052 | 4.970 | *** | Supported |

| H8: Entertainment → Flow in livestreaming shopping | 0.214 | 0.068 | 3.148 | ** | Supported |

| H9: Entertainment → Perceived pleasure | 0.335 | 0.055 | 6.076 | *** | Supported |

| H10: Easy to use → Perceived pleasure | −0.060 | 0.052 | 1.156 | 0.248 | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, T.; Weng, Z.; Huang, C. Study on Livestreaming Shopping Behavior of the Elderly Based on SOR Theory. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2026, 21, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer21010009

Huang T, Weng Z, Huang C. Study on Livestreaming Shopping Behavior of the Elderly Based on SOR Theory. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2026; 21(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer21010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Tianyang, Zhen Weng, and Chiwu Huang. 2026. "Study on Livestreaming Shopping Behavior of the Elderly Based on SOR Theory" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 21, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer21010009

APA StyleHuang, T., Weng, Z., & Huang, C. (2026). Study on Livestreaming Shopping Behavior of the Elderly Based on SOR Theory. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 21(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer21010009