Abstract

Influencer marketing practice predominantly favors same-niche partnerships; however, industry evidence suggests that unconventional pairings can sometimes outperform traditional matches, highlighting a knowledge gap regarding how collaboration structure influences consumer response. Drawing on Optimal Distinctiveness Theory, this research examines whether cross-niche collaborations enhance brand evaluations by fulfilling concurrent desires for inclusion and differentiation. Four controlled experiments (total N = 1482) employing Instagram-style stimuli and behavioral intention measures compare same- versus cross-niche alliances while manipulating or measuring consumers’ need for uniqueness and category expertise. Across studies, cross-niche (versus same-niche) collaborations consistently improve brand attitude, an effect fully mediated by heightened perceptions of brand innovation. Moderation analyses reveal that this indirect effect is amplified among consumers high in need for uniqueness but attenuated—and in some cases reversed—among category experts, who tend to prefer the depth signaled by same-niche partnerships. Alternative explanations, including curiosity, source credibility, and message liking, are empirically ruled out. These findings extend Optimal Distinctiveness Theory to influencer branding by identifying collaboration type as a market-level cue signaling innovation while refining influencer effectiveness models through a dual-contingency framework that incorporates motivational and knowledge-based audience factors. From a managerial perspective, the results suggest deploying cross-niche alliances when targeting novelty-seeking or novice segments while preserving niche purity or offering technical justification when addressing expert consumers, thereby aligning collaboration strategies with audience composition.

1. Introduction

Influencer collaborations anchor a USD 25 billion creator economy that continues to grapple with consistent engagement protocols and standardized outcome metrics [1]. Within this rapidly professionalizing landscape, brand managers typically prioritize same-niche partnerships, as nano-influencers targeting tightly segmented audiences achieve an average Instagram engagement rate of 1.73%, far exceeding the 0.61% observed for macro-influencers [2]. These figures reinforce a prevailing managerial logic: overlapping audiences foster relevance, relevance drives engagement, and engagement ultimately converts. However, high engagement does not necessarily translate into favorable brand attitudes—particularly as brands compete for cultural freshness in saturated markets. Evidence from StackInfluence [3] that cross-channel micro-influencer programs deliver 13× ROI underscores the possibility that reach and novelty can, at times, outweigh narrow precision. Reconciling these seemingly conflicting insights constitutes both an urgent managerial challenge and a theoretical question that this study seeks to address.

Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (ODT) provides a useful framework for re-evaluating collaboration strategies. According to ODT, consumers are drawn to social entities that balance the twin drives for inclusion and differentiation. Cross-niche collaborations may thus signal that a brand is sufficiently mainstream to ensure relevance yet bold enough to transcend categorical boundaries—a balance that can enhance brand attitudes. Building on Pappu and Quester’s [4] proposition that perceived brand innovativeness translates into evaluative and behavioral loyalty, we identify perceived brand innovation as the cognitive mechanism through which collaboration type influences brand attitudes.

Previous influencer marketing research has focused largely on structural attributes such as follower count [5], disclosure format [6], or sponsor–influencer fit [7]. While these studies illuminate important message characteristics, they give limited attention to the relational architecture between partnering influencers, especially collaborations that deliberately cross topical or categorical boundaries. Thomas et al. [8] take an initial step by demonstrating that asymmetric influencer partnerships can mitigate skepticism about self-serving motives, yet their work does not extend to brand-level outcomes. Similarly, Filali-Boissy et al. [9] and Mulholland et al. [10] show how co-creation practices and micro-versus-mega dynamics affect authenticity and engagement but do not theorize about innovation signaling. Emerging evidence on brand–influencer fit suggests that unexpected pairings can heighten pleasure and certainty [11], hinting that category-spanning alliances may reposition a brand as progressive. However, a systematic test of this proposition—particularly incorporating psychological processes and individual differences—remains lacking.

The present research addresses this gap by comparing same-niche and cross-niche collaborations and assessing their effects on brand attitude through perceived brand innovation. By integrating ANA’s [1] standardized engagement, awareness, and conversion metrics, we ground our framework in industry practice while situating our hypotheses in ODT. We further examine consumer need for uniqueness (NFU) and category expertise as dual boundary conditions. High-NFU consumers, who actively seek distinctiveness, should respond more strongly to the innovation cues embedded in cross-niche partnerships, whereas experts—due to entrenched schemata—may discount these cues unless the collaboration conveys technical legitimacy.

As noted, brand managers often rely on niche collaborations to reinforce authenticity and trust [12,13]. Yet, this focus can inadvertently signal rigidity, alienating novelty-seeking consumers. We conceptualize collaboration type as a macro-level cue that shapes innovation inferences: same-niche alliances connote expertise depth, whereas cross-niche alliances signal boundary spanning and creative recombination—core markers of innovation [14].

However, this signal translation is not automatic. Consumers first assess a brand’s underlying motives and competence [15] before updating evaluations. We thus posit perceived brand innovation as a diagnostic appraisal that mediates the effect of collaboration type on brand attitude. Qualitative evidence shows that unexpected partnerships evoke perceptions of “freshness” and “forward thinking” [16], while neurophysiological studies confirm that novelty triggers heightened attention and approach motivation in influencer content [17], supporting innovation as a central mechanism. The moderating roles of need for uniqueness (NFU) and category expertise add critical audience heterogeneity. High-NFU consumers treat distinctive cues as identity resources [18], making them more receptive to cross-niche collaborations. In contrast, category experts engage in confirmatory processing [11] and prefer depth over novelty, unless functional complementarity is clear. This dual-moderator lens answers calls to move beyond one-size-fits-all influencer segmentation [19,20]. Synthesizing these considerations, we propose the following research model: Collaboration Type (same vs. cross niche) → Perceived Brand Innovation → Brand Attitude, with NFU and category expertise moderating the first stage. To test this model, we conduct a 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects experiment, manipulating collaboration type and systematically varying NFU and category expertise while controlling for message content, influencer status, and sponsorship disclosure. Consistent with ANA [1] guidelines, we also capture behavioral intention metrics (click-through and purchase likelihood) to ensure managerial relevance.

Building on this framework, this study addresses three research questions: (1) Does a cross-niche collaboration enhance brand attitude relative to a same-niche collaboration? (2) Is perceived brand innovation the psychological mechanism underlying this effect? (3) How do NFU and category expertise jointly condition the strength of innovation signaling?

This research extends Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (ODT) from a consumer identity perspective to an actionable branding context by demonstrating that cross-niche influencer collaborations satisfy the dual motives for inclusion and differentiation and, in turn, elevate brand attitudes. Academically, this study advances influencer marketing literature in three ways. First, it reconceptualizes collaboration type—as opposed to influencer size or disclosure format—as a structural marketplace cue shaping innovation perceptions [8,14]. Second, it incorporates perceived brand innovation into influencer effectiveness models, responding to calls by Pappu and Quester [4] to unpack the micro-foundations of innovativeness evaluations. Third, by uncovering a double-contingency process in which NFU amplifies and expertise attenuates innovation signaling, this study adds nuance to recent segmentation approaches that rely primarily on demographic or platform-based variables [10,16].

From a managerial perspective, the findings caution against defaulting to same-niche pairings simply because they generate higher engagement rates. Brands targeting novelty seekers can strategically employ cross-niche alliances to signal innovation, particularly when introducing incremental upgrades that might otherwise appear routine. Conversely, when addressing expert audiences, marketers should complement cross-niche collaborations with detailed technical narratives to reinforce credibility. Aligning collaboration architecture with both dispositional and knowledge-based consumer traits enables firms to leverage optimal distinctiveness, bridging the gap between engagement metrics and attitudinal outcomes while moving beyond entrenched assumptions about niche purity.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Optimal Distinctiveness Theory

Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (ODT) originated in social identity research when Brewer [21] proposed that individuals strive to balance inclusiveness with uniqueness. Subsequent marketing scholarship extended this framework to group behavior and brand positioning in competitive yet legitimacy-conferring categories [22]. ODT posits that individuals navigate identity threats by affiliating with collectives that provide sufficient similarity to secure social validation while retaining distinctive cues that preserve personal autonomy. This dynamic produces an inverted-U relationship between categorical typicality and evaluative outcomes: brands offering moderate novelty or hybrid attributes maximize consumer satisfaction, legitimacy perceptions, and performance metrics [23,24].

Within consumer research, ODT has informed studies on branding, product design, and consumption communities, consistently demonstrating that moderate distinctiveness enhances sales, loyalty, and community identification. However, boundary conditions emerge from category heterogeneity, alternative sources of legitimacy, and technological contexts [25,26]. Empirical investigations in domains such as automobiles, mobile apps, and online platforms reveal U-shaped or inverted-U performance patterns moderated by factors such as within- versus between-organization distinctiveness, revenue models, and complementor status [27]. Related work links cultural identity salience, need for uniqueness, and affiliation motives to distinctiveness preferences, uncovering cross-cultural asymmetries and psychological moderators [28]. These findings underscore that variables shaping the distinctiveness–legitimacy calculus also condition brand attitude formation. For example, perceived category heterogeneity determines whether moderate or extreme novelty is embraced; higher heterogeneity reduces conformity pressures, attenuating the benefits of distinctiveness cues [29]. Dispositional factors operate similarly: high need for uniqueness amplifies preferences for distinctive collaborations, strengthening favorable responses to boundary-crossing brands, whereas strong affiliation motives tilt preferences toward same-niche partnerships, diminishing innovation inferences [22]. Complementor status and cultural symbolism further provide borrowed legitimacy, as high-status partners buffer risk perceptions and enable greater tolerance for bold distinctiveness, ultimately improving brand attitudes [27].

Applying ODT to influencer collaborations suggests that cross-niche partnerships can optimally reconcile differentiation and conformity, thereby enhancing brand attitudes through perceived innovation. For instance, when a beauty brand partners with a gaming influencer, the collaboration blurs categorical boundaries sufficiently to signal novelty while retaining recognizability through the endorsement frame, satisfying consumers’ dual motives. Distinctiveness arises from the juxtaposition of unrelated domains, prompting elaboration and curiosity that elevate perceptions of creativity and “coolness”—key drivers of brand evaluations [30]. At the same time, conformity is preserved because each influencer retains domain legitimacy; their combined endorsement conveys quality and social acceptance, reducing risk perceptions [31]. In line with ODT, these dynamics predict an inverted-U effect: same-niche collaborations lack distinctiveness, while excessively distant pairings risk illegitimacy, both of which depress brand attitudes. Cross-niche collaborations occupy the optimal midpoint, particularly among consumers high in need for uniqueness or operating within heterogeneous categories, where schema contrast enhances perceived innovation and fosters favorable brand evaluations and positive word-of-mouth intentions [26].

2.2. Collaboration Type

Collaboration type—whether influencers originate from the same niche or from complementary niches—captures the perceived boundary-spanning scope of a partnership. Same-niche collaborations leverage shared category expertise, whereas cross-niche pairings juxtapose distinct knowledge domains and audience bases [32]. Consumers interpret these structural differences as signals of creative breadth: cross-niche alliances are more likely to be perceived as experimental and novel, while same-niche pairings connote depth and specialization [8]. Building on this conceptualization, the following discussion examines how collaboration type shapes downstream psychological and behavioral outcomes.

Empirical research consistently finds that cross-niche partnerships enhance perceived innovativeness because the unexpected combination of disparate influencer identities disrupts categorical expectations [11]. Heightened innovativeness strengthens brand attitudes by cueing forward-looking benefits and stimulating cognitive elaboration, thereby increasing attitude certainty and recommendation intentions [33]. These positive evaluations are further reinforced when collaborations exhibit strong influencer–follower congruence; consumers who identify with at least one partnering creator attribute joint content to authentic interest rather than commercial calculation [34]. Supporting this view, recent findings indicate that cross-niche collaborations can mitigate sponsorship skepticism: when partners display complementary rather than redundant competencies, follower inferences of opportunism diminish, bolstering sponsor credibility [7]. Dong, Zhou, and Liao [35] similarly report that followers of mega-influencers—accustomed to diverse content streams—respond particularly favorably to cross-niche tie-ups, showing elevated purchase intentions and engagement relative to same-niche executions.

Yet, boundary spanning is not without potential costs. Although cross-niche pairings can signal creativity, they may simultaneously erode perceived expertise when thematic distance between partners becomes excessive, creating attributional ambiguity about which collaborator drives value [36]. Moreover, most empirical evidence is based on short-term attitudinal measures; longitudinal outcomes such as repeat purchase, community growth, and algorithmic amplification remain underexplored. Similarly, moderating factors such as disclosure style and compensation visibility—which may amplify or attenuate authenticity perceptions in heterogeneous collaborations—have received limited attention. Current scholarship has yet to determine the tipping point at which creativity gains from cross-niche collaborations are offset by losses in perceived expertise, nor has it examined how platform-level visibility policies interact with collaboration type to shape consumer learning over time. Addressing these gaps is essential for theorizing the optimal breadth of influencer collaborations and for guiding managerial decisions on influencer selection and disclosure strategies.

2.3. Perceived Brand Innovation

Perceived brand innovation refers to consumers’ subjective assessment that a brand consistently delivers novel and meaningful offerings, signaling forward-looking capabilities and a willingness to depart from category conventions [4,37]. These attributes suggest that influencer collaborations can shape consumers’ perceptions of a brand’s innovativeness.

Empirical evidence indicates that partnerships with entities operating outside a brand’s established domain heighten perceptions of novelty because such unexpected pairings disrupt category norms and convey creative breadth [38]. In contrast, within-niche collaborations reinforce familiarity and are less likely to refresh innovation perceptions, highlighting the need to examine how elevated perceived innovation drives downstream consumer responses.

Heightened perceptions of brand innovation yield favorable outcomes by serving as both a quality cue and a differentiator. Prior research shows that innovativeness enhances perceived quality, which, in turn, strengthens brand loyalty [4]. Visual design elements such as glossy finishes translate innovation perceptions into more positive product evaluations and greater alignment with youthful brand positioning [39], while difficult-to-process color schemes can elevate perceived innovativeness and increase purchase intentions depending on self-construal [40]. Moreover, innovation signals reshape category representations, making competing brands appear less prototypical and redirecting choice toward the focal brand [41]. Collectively, these findings position perceived brand innovation as a central mechanism through which cross-niche collaborations convert attention into durable attitudinal and behavioral advantages.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Collaboration Type, Perceived Brand Innovation and Brand Attitude

Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (ODT) posits that individuals seek social entities that simultaneously satisfy needs for inclusion and differentiation [21]. Applied to branding, consumers favor firms that are anchored in familiar conventions yet sufficiently bold to stand apart [37]. Collaboration strategy offers a salient signal of a brand’s position along this inclusion–differentiation continuum. Partnerships with influencers operating within the same content niche primarily reinforce category conventions and perceived similarity to peer brands. In contrast, cross-niche collaborations unite audiences and aesthetics that rarely intersect, signaling that the focal brand is transcending category boundaries [8]. Such boundary-spanning activities have long been interpreted as indicators of creativity and exploratory competence—key facets of perceived brand innovation [32,42]. Accordingly, cross-niche partnerships are expected to heighten consumers’ perceptions that the brand is imaginative, future-oriented, and capable of delivering novel value propositions relative to same-niche alliances.

Perceived brand innovation is a well-established antecedent of favorable consumer responses. Innovative brands are perceived to offer superior functionality, heightened experiential excitement, and symbolic leadership, all of which strengthen affective evaluations [4]. Empirical evidence shows that even incremental signals of innovation—such as unconventional product pairings or novel aesthetic cues—can elevate brand attitudes through increased admiration and credibility [39,41]. Within influencer marketing, perceived novelty plays a comparable role: collaborations that extend expected influencer–brand boundaries are associated with stronger engagement and more positive brand beliefs [11]. Together, these findings suggest a sequential process in which collaboration type shapes perceived brand innovation, which in turn drives overall brand attitude.

ODT further clarifies why this indirect pathway arises. Cross-niche collaborations satisfy consumers’ distinctiveness needs by positioning the brand as a category rule-breaker, while the presence of a trusted influencer anchors the brand within a familiar social context, fulfilling inclusion needs. This balance reduces perceived risk typically associated with novelty [37] and enables positive affect linked to innovation to influence global brand evaluations. By contrast, same-niche collaborations lack the distinctiveness component, providing fewer cues of creative competence and thus eliciting weaker innovation perceptions and smaller gains in brand attitude.

H1.

Cross-niche collaborations will enhance consumers’ brand attitudes than same-niche collaborations.

H2.

The effect of collaboration type on brand attitude is mediated by perceived brand innovation.

3.2. Consumer Need for Uniqueness

Cross-niche influencer collaborations expose followers to an unexpected combination of expertise domains, prompting a reclassification of the focal brand as a boundary-spanning actor [8]. Signaling theory suggests that such nonroutine partnerships convey difficult-to-imitate knowledge flows and technological agility, thereby enhancing perceived brand innovation [4]. In turn, perceived innovation generally strengthens brand attitude, as consumers associate innovativeness with superior problem-solving capabilities and symbolic modernity [41].

However, this causal pathway is unlikely to be uniform across all consumers. The Consumer Need for Uniqueness (NFU) captures stable individual differences in the valuation of distinctiveness cues [43]. High-NFU individuals actively seek options that differentiate them from normative consumption patterns and are often willing to pay premiums for novel designs or limited editions [44]. For this segment, innovation signals arising from cross-niche collaborations serve a dual function: they indicate functional advancement while simultaneously providing a social-symbolic resource that affirms personal distinctiveness [45]. In contrast, low-NFU consumers place greater emphasis on relational reassurance and category familiarity, reducing the evaluative impact of innovation cues [46]. These considerations suggest that NFU moderates the strength of the perceived brand innovation → brand attitude relationship.

H3.

Consumer Need for Uniqueness moderates the relationship between collaboration type and brand attitude, such that the positive effect of cross-niche (vs. same-niche) influencer collaborations on brand attitude is stronger for consumers with higher (vs. lower) levels of need for uniqueness.

3.3. Category Expertise

Cross-niche influencer collaborations expose followers to unexpected combinations of category schemas, functioning as a salient incongruity cue that enhances perceptions of brand innovation [8,41]. These novelty perceptions are consequential because brands perceived as more innovative are often judged higher in quality and elicit more favorable attitudes [4,40].

However, appreciating the innovative logic embedded in a cross-niche pairing requires consumers to decode subtle complementarities in usage context, symbolic meaning, and underlying technology. Classic expertise research demonstrates that knowledgeable consumers possess richer category-specific schemata and greater capacity to process diagnostic features [47], enabling them to extract meaning from complex market signals that novices may overlook. Recent studies in influencer marketing confirm that expertise sharpens value extraction when posts contain nuanced cues, such as color incongruity [39] or layered narratives [7].

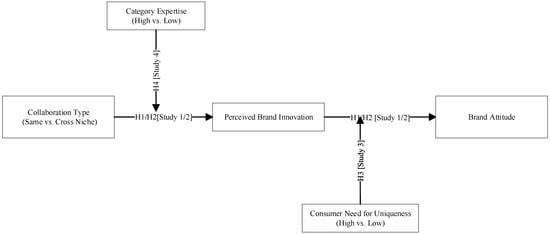

Accordingly, when a collaboration bridges disparate niches—e.g., a fitness trainer partnering with a gourmet snack brand—experts can reconcile surface-level incongruities with deeper functional or symbolic synergies, thereby amplifying perceived brand innovation. Low-expertise consumers, lacking such refined schemata, are more likely to rely on heuristics and may interpret the same collaboration as mere noise [48]. These insights suggest that category expertise selectively enhances the innovation signal conveyed by cross-niche collaborations, producing an interaction effect on downstream brand evaluations. Building on this premise, we propose that perceived brand innovation increases disproportionately among experts when brands engage in cross-niche, rather than same-niche, influencer partnerships, and that this differential perception translates into stronger brand attitudes [38] (see Figure 1 for the detailed research model).

Figure 1.

Framework of this study.

H4.

Category expertise moderates the relationship between collaboration type and perceived brand innovation, such that the positive effect of cross-niche (vs. same-niche) influencer collaborations on perceived brand innovation is stronger for consumers with higher category expertise.

4. Methodology

4.1. Overview of Study

Across four experiments (N_total = 1220), we examine how niche alignment in influencer collaborations shapes brand evaluations and the underlying psychological mechanisms. Study 1 (N = 200, MTurk) compared same-niche influencer–influencer posts with cross-niche influencer–brand posts on Instagram, finding that niche-matched partnerships enhanced brand attitude. Study 2 (N = 200, Prolific) demonstrated that cross-niche collaborations can instead elevate brand attitudes when they signal innovation, with perceived brand innovativeness mediating this effect. Study 3 (2 × 2; N = 400) crossed collaboration format with a Need for Uniqueness (NFU) prime, revealing that cross-niche advantages emerged primarily among high-NFU participants. Study 4 (2 × 2; N = 420) manipulated category expertise and uncovered a crossover pattern: novices preferred cross-niche pairings, whereas experts responded more positively to same-niche depth.

Collectively, these findings delineate a pathway in which collaboration type influences perceived brand innovativeness, which in turn drives brand attitude, with effects moderated by personal distinctiveness goals and domain-specific knowledge. This evidence provides actionable guidance for influencer-partner selection and strategic campaign design. All scales used in this study were adapted from well-established literature, and their content validity was confirmed through pilot testing prior to the formal experiments. The measures for all key constructs demonstrated good internal consistency reliability.

4.2. Study 1: Main Effect

4.2.1. Purpose

Study 1 aims to examine how different types of influencer collaborations (same-niche vs. cross-niche) influence consumers’ attitudes toward the brand. We predict that, compared with same-niche collaborations, cross-niche collaborations will lead consumers to form more favorable brand attitudes (Hypothesis 1).

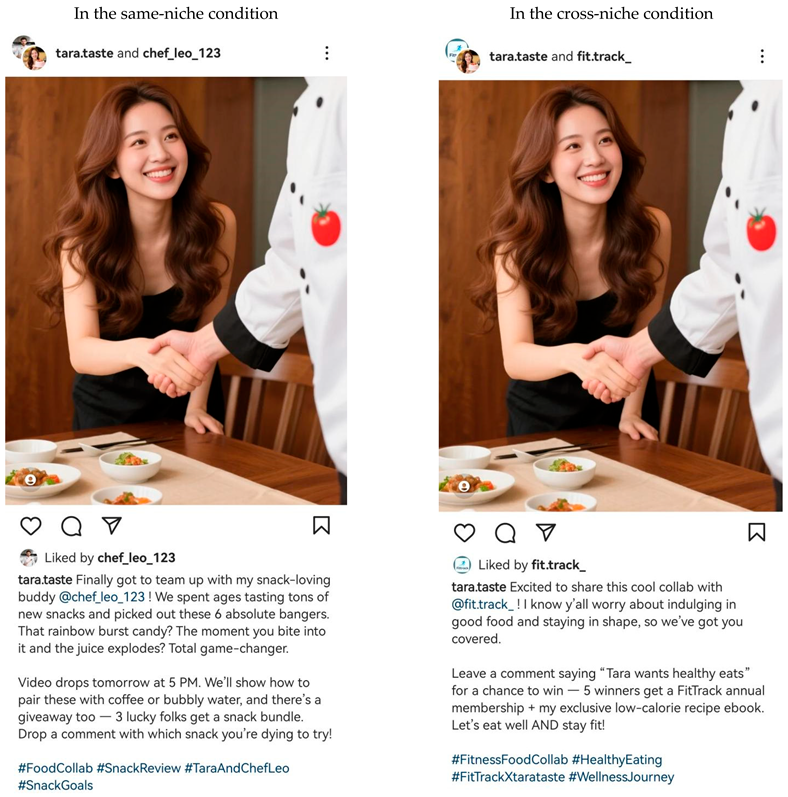

4.2.2. Stimuli and Pretest

To manipulate collaboration type while controlling extraneous features, we created two Instagram mock-ups for a fictitious food-review influencer, “TaraTaste”. Both posts used an identical layout: profile picture, 150-word caption, one static photograph, and equivalent numbers of likes and comments. In the same-niche condition, TaraTaste announced a joint video with another food influencer, “ChefLeo”, highlighting their shared focus on novel snack reviews. In the cross-niche condition, TaraTaste presented a paid partnership with a fitness-app brand, “FitTrack”, describing a joint giveaway. All text unrelated to the manipulation (e.g., greeting, posting schedule, hashtag count) was matched across conditions, and images shared the same color palette and lighting to ensure symmetry (see detailed stimuli in Appendix A).

A pretest on Prolific (N = 160, 51.25% female, Mage = 32.47) confirmed successful manipulation. Participants rated perceived cross-niche collaboration using the item, “To what extent does this post feature a collaboration across different niches?” (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Those in the cross-niche condition reported higher ratings (M = 6.12, SD = 0.87) than those in the same-niche condition (M = 2.88, SD = 1.18), t(158) = 19.01, p < 0.001.

4.2.3. Procedure

Two hundred U.S. participants were recruited via MTurk for small monetary compensation (49.50% female; Mage = 33.11, SD = 8.42). Using a between-subjects design, participants were randomly assigned to view either the same-niche or cross-niche condition in a Qualtrics survey approved by the institutional ethics committee. After providing informed consent, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire covering age, gender, and Instagram usage patterns. They were then presented with a cover story framing this study as an investigation into “online content evaluation”. Subsequently, each participant viewed their assigned Instagram post for a mandatory minimum of 25 s. To mitigate potential demand characteristics, a one-minute word-scramble task was administered immediately after the stimulus exposure.

Then, the participants answered the relevant questions. The dependent variable, brand attitude, was assessed using a five-item, seven-point semantic differential scale adapted from established prior research. Example items included “unfavorable/favorable”, “bad/good”, “unappealing/appealing”, “unlikeable/likeable”, and “negative/positive” (Cronbach’s α = 0.91). A manipulation check item, which replicated the wording used in the preliminary pretest, was included to verify the effectiveness of the collaboration type manipulation. Additionally, an attention check was embedded within the survey to ensure data quality. Finally, participants were fully debriefed regarding this study’s purpose upon completion of the procedure.

4.2.4. Result

Manipulation check. A one-way ANOVA confirmed that collaboration type affected perceived cross-niche collaboration. Participants in the cross-niche condition rated the post significantly higher (M = 6.10, SD = 0.90) than those in the same-niche condition (M = 2.93, SD = 1.12), F(1, 198) = 310.54, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.61, indicating a successful manipulation.

Brand attitude. ANOVA results revealed a significant main effect of collaboration type on brand attitude, F(1, 198) = 23.07, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10. Participants exposed to the cross-niche influencer collaboration reported more positive brand attitudes (M = 5.39, SD = 1.02) than those exposed to the same-niche influencer–brand partnership (M = 4.71, SD = 1.19).

4.2.5. Discussion

Study 1 provides initial evidence that cross-niche influencer collaborations lead to more favorable brand attitudes compared to same-niche partnerships, supporting Hypothesis 1.

4.3. Study 2: Mediating Role of Perceived Brand Innovation

4.3.1. Purpose

Study 2 was designed to examine whether the type of influencer collaboration (same-niche vs. cross-niche) influences consumers’ brand attitude through perceived brand innovation. Extending Study 1’s main effect, we predicted that cross-niche collaborations would signal a willingness to experiment and, consequently, elevate perceptions of the brand’s innovativeness, which in turn would enhance brand attitude. We also measured state curiosity as a theoretically plausible but conceptually distinct alternative mediator.

4.3.2. Stimuli and Pretest

The stimuli followed the influencer-collaboration paradigm described in Study 1b; therefore, no new materials were created. Participants read a brief social-media announcement describing either (a) a joint product line launched by two beauty influencers (“same-niche” condition) or (b) a product line created by a beauty influencer in tandem with a technology influencer (“cross-niche” condition). Both vignettes included identical visuals (brand logo and neutral background) and length (approx. 120 words), varying only in the collaborators’ domains (see detailed stimuli in Appendix B). An independent pretest on Prolific (N = 160; 56.9% female; Mage = 33.41) assessed the perceived overlap of the collaborators’ expertise (1 = very dissimilar, 7 = very similar). Respondents in the same-niche condition reported higher similarity (M = 5.98, SD = 0.96) than did those in the cross-niche condition (M = 2.11, SD = 1.02), t(158) = 23.43, p < 0.001, confirming a successful manipulation.

4.3.3. Procedure

Two hundred U.S. consumers (52.0% female, Mage = 34.67, SD = 10.41) were recruited from Prolific in March 2024. Following institutional guidelines (ethics approval code: BUS-24-031), each participant gave informed consent and was randomly assigned to one of the two collaboration conditions.

After reading the assigned vignette, participants engaged in a 90-s arithmetic puzzle designed to mitigate potential priming effects. They then completed a series of measures assessing key variables. Brand attitude was measured using a five-item, seven-point semantic differential scale developed for this study (e.g., “My overall evaluation of this brand is: 1 = very negative, 7 = very positive”; α = 0.93). Perceived brand innovation was evaluated with three items adapted from the Perceived Innovativeness Scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree; e.g., “This collaboration shows that the brand likes to innovate”; α = 0.88). Curiosity was assessed using four items from the State Curiosity Scale (e.g., “I feel eager to learn more about this collaboration”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.90). Additionally, several control variables were measured using established three-item scales (7-point, αs ≥ 0.84), including face threat (e.g., “Buying this product would make me feel judged”), moral disengagement (e.g., “Any negative effects of this collaboration are trivial”), perceived novelty, and attention to the vignette. Finally, participants completed the manipulation check item consistent with the pretest, provided demographic information, and were debriefed about this study’s purpose.

4.3.4. Result

Manipulation check. A one-way ANOVA on perceived domain similarity revealed a strong effect of collaboration type, F(1, 198) = 296.34, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.60. Participants in the same-niche condition perceived higher similarity (M = 6.02, SD = 0.91) than those in the cross-niche condition (M = 2.08, SD = 0.97), confirming the manipulation.

Main and ancillary effects. Six separate ANOVAs examined the effects of collaboration type across key variables. For brand attitude, the cross-niche condition (M = 5.62, SD = 0.97) significantly exceeded the same-niche condition (M = 4.88, SD = 1.04), F(1, 198) = 28.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13. Face threat showed no significant difference between conditions, F(1, 198) = 0.73, p = 0.395, η2 = 0.00, nor did moral disengagement, F(1, 198) = 1.21, p = 0.272, η2 = 0.01. For curiosity, the cross-niche condition (M = 4.87, SD = 1.09) marginally exceeded the same-niche condition (M = 4.61, SD = 1.10), F(1, 198) = 4.04, p = 0.046, η2 = 0.02. Perceived novelty was significantly higher in the cross-niche condition (M = 5.48, SD = 0.91) compared to the same-niche condition (M = 4.77, SD = 1.04), F(1, 198) = 29.78, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13. Finally, attention showed no difference between conditions, F(1, 198) = 0.05, p = 0.826, η2 = 0.00.

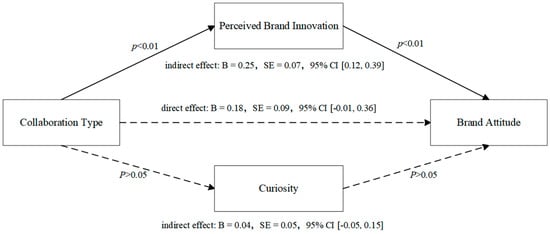

Parallel mediation. Using Hayes [49] PROCESS Model 4 (5000 bootstraps; IV coded 0 = same-niche, 1 = cross-niche), perceived brand innovation and curiosity were entered in parallel. The indirect effect through perceived brand innovation was significant (B = 0.25, SE_boot = 0.07, 95% CI [0.12, 0.39]), while the indirect effect through curiosity was non-significant (B = 0.04, SE_boot = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.15]). The total indirect effect was significant (B = 0.27, SE_boot = 0.08, 95% CI [0.12, 0.44]), while the direct effect controlling for both mediators was non-significant (B = 0.18, SE = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.36], see Figure 2.). These results indicate that perceived brand innovation fully accounted for the collaboration-type effect, whereas curiosity did not, supporting the proposed mediation while dismissing the alternative explanation.

Figure 2.

Results of the mediation analysis.

4.3.5. Discussion

This study further investigates the mediating role of perceived brand innovation in the relationship between collaboration type and brand attitude. It tests the hypothesis that perceived innovation is the key psychological mechanism that explains why cross-niche collaborations enhance brand attitude. The findings support Hypothesis 2, confirming that perceived brand innovation fully mediates the effect of collaboration type on brand attitude. Curiosity, despite being slightly higher in the cross-niche condition, did not mediate the focal relationship, thereby ruling out a plausible rival account. Theoretically, these findings deepen our understanding of how boundary-spanning partnerships translate into favorable brand evaluations by signaling dynamic capabilities rather than merely piquing curiosity.

4.4. Study 3: Moderating Role of Consumer Need for Uniqueness

4.4.1. Purpose

Study 3 was conducted to investigate whether the attitudinal advantage of a cross-niche influencer collaboration over a same-niche collaboration depends on consumers’ Need for Uniqueness (NFU). Building on distinctiveness theory, we predicted that the positive effect of a cross-niche partnership on brand attitude would be stronger for individuals whose NFU is high, whereas low-NFU consumers would evaluate both collaboration formats similarly.

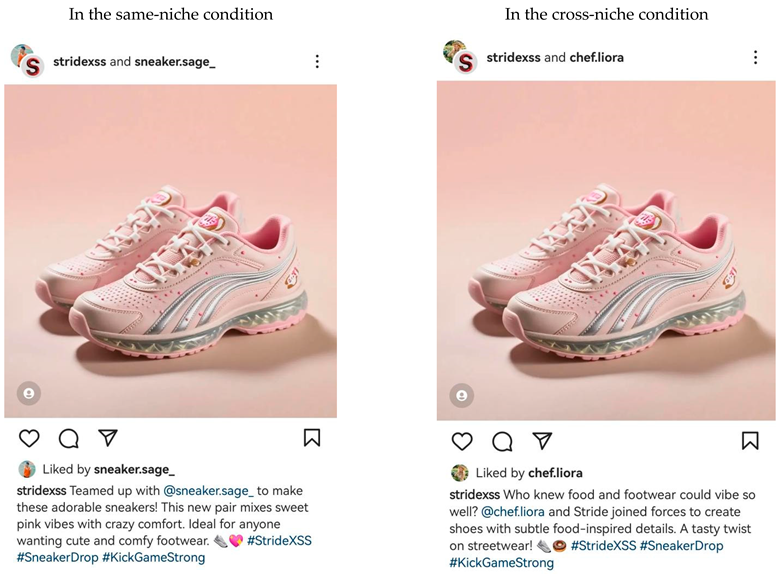

4.4.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Independent-variable stimuli were two mock Instagram posts announcing a limited-edition sneaker release. In the same-niche condition, the brand “Stride” partnered with another footwear influencer (@SneakerSage). In the cross-niche condition, Stride teamed with a gourmet chef influencer (@ChefLiora). Each post contained one high-resolution image of the sneaker, 58 ± 1 words of caption, identical hashtags, and an equal number of emojis so that only the collaboration type varied.

Need for Uniqueness was primed with a three-minute writing exercise adapted from prior research. In the high-NFU version, participants listed five occasions on which they deliberately chose an uncommon product and described why standing out was important. In the low-NFU prime, they recalled five occasions on which they deliberately conformed to popular choices and explained why blending in felt comfortable; word-count requirements and time limits were identical across primes (see detailed stimuli in Appendix C).

A separate pretest (N = 160, 80 per collaboration condition) recruited from Prolific confirmed stimulus validity. Perceived cross-niche novelty was measured with one item (“This collaboration combines influencers from different domains”, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Participants judged the cross-niche post as more cross-domain (M = 6.23, SD = 0.83) than the same-niche post (M = 2.14, SD = 1.02), t(158) = 26.20, p < 0.001. A second pretest (N = 140, 70 per NFU prime) verified the prime. Using four items from Tian et al. [44] (α = 0.88), high-prime respondents reported greater NFU (M = 5.77, SD = 0.74) than low-prime respondents (M = 3.05, SD = 0.91), t(138) = 22.44, p < 0.001.

4.4.3. Procedure

The main experiment adopted a 2 (collaboration type: same vs. cross niche) × 2 (NFU prime: high vs. low) between-subjects design. Four hundred U.S. adults were recruited through Prolific (48.5% female, Mage = 36.02, SD = 11.94) in exchange for a small payment and randomly assigned to one of the four cells (n = 100 each). After providing informed consent, participants completed the designated NFU writing task. A 20-s filler maze served as a distraction before they viewed the assigned Instagram post. Exposure time was fixed at 15 s via an on-screen timer.

Immediately afterwards, respondents answered the manipulation check for collaboration type (“This post features a collaboration between influencers from different product domains”, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) and the four-item NFU scale (α = 0.89). The dependent variable, brand attitude, was assessed with five seven-point semantic differential items (unfavorable/favorable, bad/good, negative/positive, unappealing/appealing, dislike/like; α = 0.92) adapted from prior research. An instructed-response item served as an attention screen; 10 participants failed and were replaced to maintain the planned sample. Finally, demographic questions were posed and participants were debriefed. This study received approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB-22-417).

4.4.4. Result

Manipulation check: collaboration type. A one-way ANOVA showed that the perceived cross-domain score was much higher in the cross-niche condition (M = 6.18, SD = 0.85) than in the same-niche condition (M = 2.21, SD = 1.04), F(1, 398) = 1178.94, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.75, confirming the effectiveness of the manipulation.

Manipulation check: NFU prime. Participants in the high-NFU prime reported greater NFU (M = 5.65, SD = 0.79) than those in the low-NFU prime (M = 3.09, SD = 0.88), F(1, 398) = 1024.67, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.72.

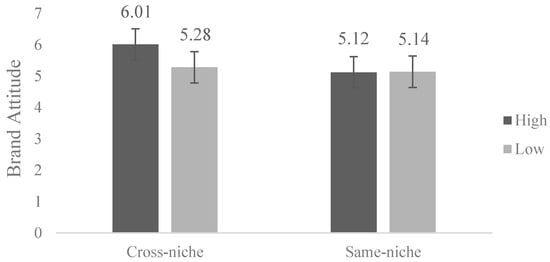

Brand attitude. A 2 × 2 ANOVA on brand attitude revealed a significant main effect of collaboration type, F(1, 398) = 18.92, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05, and a significant main effect of NFU, F(1, 398) = 10.44, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.03. Crucially, the interaction was significant, F(1, 398) = 20.36, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05. Simple-effects analyses indicated that for high-NFU participants, cross-niche collaboration yielded more favorable brand attitudes (M = 6.01, SD = 0.83) than same-niche collaboration (M = 5.12, SD = 1.02), F(1, 398) = 34.11, p < 0.001. Among low-NFU participants the difference was nonsignificant (Mcross = 5.28, SD = 0.96 vs. Msame = 5.14, SD = 0.94), F(1, 398) = 1.00, p = 0.318. See Figure 3 for detailed results.

Figure 3.

The interaction effect of collaboration type and consumer need for uniqueness on brand attitude.

4.4.5. Discussion

This study examines how individual differences, specifically consumer need for uniqueness (NFU), moderate the effect of collaboration type on brand attitude. It tests whether the positive effect of cross-niche collaborations on brand attitude is stronger for consumers with high NFU. The results support Hypothesis 3, showing that high-NFU individuals are more responsive to the innovation cues provided by cross-niche collaborations, which further refines our understanding of audience segmentation in influencer marketing.

4.5. Study 4: Moderating Role of Category Expertise

4.5.1. Purpose

Study 4 examined whether consumers’ category expertise moderates the influence of influencer collaboration type on brand attitude. Drawing on persuasion knowledge theory, we predicted that experts would prefer collaborations that remain within a single niche (same-niche), which signal depth and authenticity, whereas novices would favor cross-niche collaborations that broaden category understanding.

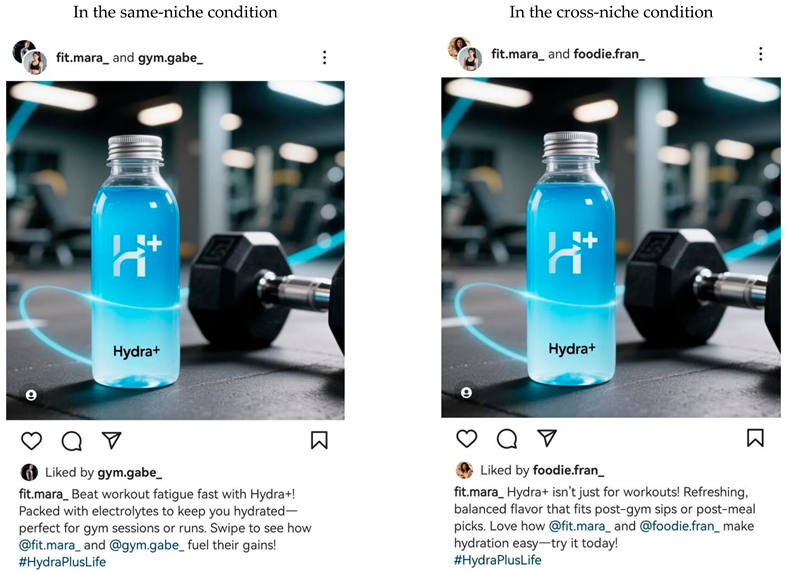

4.5.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Independent-variable stimuli were two Instagram posts for a fictitious sports-drink brand “Hydra+”. Both displayed an identical product photo (500 × 500 px) and 40-word caption, varying only in the tagged influencers. In the same-niche condition, @FitMara (fitness influencer) collaborated with @GymGabe (fitness influencer); in the cross-niche condition, @FitMara partnered with @FoodieFran (culinary influencer). Handles, follower counts (1.2 M), and sentiment (VADER compound = 0.61) were equated.

Category expertise was manipulated with a two-minute learning module. Respondents in the high-expertise condition read a concise primer on isotonic formulations, electrolytes, and absorption rates, then answered four comprehension questions with instant feedback. The low-expertise group read an unrelated text about volcanic rocks of equal length and answered parallel filler questions; thus cognitive load and test expectancy were symmetrical across groups (see detailed stimuli in Appendix D).

A pretest with 160 U.S. adults recruited from Prolific (Mage = 36.07, SD = 11.42; 52% female) randomly experienced one collaboration post and one expertise module (2 × 2, n ≈ 40 per cell). Perceived collaboration similarity (“The two collaborators belong to the same content niche”, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) served as the manipulation check for the IV. Participants rated the same-niche version as more niche-consistent (M = 5.98, SD = 0.86) than the cross-niche version (M = 2.54, SD = 1.02), t(158) = −21.84, p < 0.001. Expertise effectiveness was assessed with a single item (“I feel knowledgeable about sports drinks”, 1–7). Scores were higher after the sports-drink primer (M = 5.89, SD = 0.79) than after the geology text (M = 3.01, SD = 1.10), t(158) = 19.77, p < 0.001. Neither manipulation influenced the other check (ts < 1).

4.5.3. Procedure

Four hundred twenty U.S. adults (50.5% female; Mage = 37.52, SD = 12.04) were recruited through Prolific in exchange for USD 1.60 and randomly assigned to the four experimental cells (collaboration type × expertise). After informed consent and IRB approval (#22-317), they completed the designated expertise module, performed a 30-s arithmetic distraction task, and then viewed the assigned Instagram post for at least 15 s. Immediately afterward, they answered the manipulation check for collaboration similarity and the same item used in the pretest for perceived expertise. The dependent variable, brand attitude, was measured with five seven-point semantic differentials (unfavorable/favorable, bad/good, negative/positive, unappealing/appealing, dislike/like; α = 0.93) adapted from prior research. An instructed-response item screened inattentive respondents; 6 were excluded, leaving N = 414, but the pattern of results was identical, so we report the full sample. Finally, demographics were collected and participants were debriefed.

4.5.4. Result

Manipulation checks. A one-way ANOVA confirmed that the collaboration manipulation strongly affected perceived niche similarity, F(1, 418) = 1154.23, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.18, with the same-niche post rated higher (M = 6.02, SD = 0.82) than the cross-niche post (M = 2.60, SD = 1.01). A separate ANOVA showed that the expertise manipulation operated as intended, F(1, 418) = 897.54, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.14, as participants in the high-expertise condition felt more knowledgeable (M = 5.83, SD = 0.81) than those in the low-expertise condition (M = 3.05, SD = 1.14).

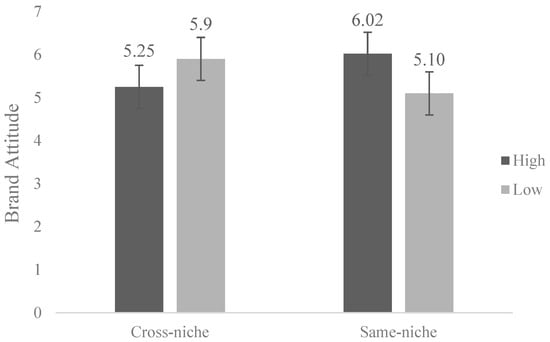

Brand attitude. A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of expertise, F(1, 418) = 2.11, p = 0.147, η2 = 0.01, and a modest main effect of collaboration type, F(1, 418) = 4.89, p = 0.028, η2 = 0.01, favoring same-niche overall. Crucially, the interaction between collaboration type and expertise was significant, F(1, 418) = 28.45, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06. Simple-effects analyses showed that among high-expertise consumers, brand attitude was higher after a same-niche partnership (M = 6.02, SD = 0.83) than after a cross-niche partnership (M = 5.25, SD = 1.01), F(1, 418) = 22.71, p < 0.001. Conversely, among low-expertise consumers, cross-niche collaboration improved brand attitude (M = 5.90, SD = 0.86) relative to same-niche collaboration (M = 5.10, SD = 0.97), F(1, 418) = 10.03, p = 0.002. See Figure 4 for detailed results.

Figure 4.

The interaction effect of collaboration type and category expertise on brand attitude.

4.5.5. Discussion

This study explores the role of category expertise as a moderator in the collaboration type–brand attitude relationship. It tests whether category experts prefer same-niche collaborations for their perceived depth and authenticity, while novices respond more positively to cross-niche collaborations. The results validate Hypothesis 4, demonstrating that category expertise influences consumers’ evaluations of collaborations, with experts favoring same-niche collaborations and novices preferring cross-niche collaborations. The findings refine our understanding of how influencer alignment strategies interact with audience knowledge structures, revealing that “the best partner” depends on who is watching (see all results in Table 1).

Table 1.

Consolidated Results of All Study.

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

Across four experiments, we consistently demonstrate that the structural arrangement of an influencer collaboration—pairing creators from the same niche versus cross niches—shapes consumers’ evaluations of the featured brand [50]. Same-niche partnerships enhance brand attitude when categorical expertise and authenticity are prioritized, whereas cross-niche alliances increase attitude when novelty and distinctiveness are valued. Anchored in Optimal Distinctiveness Theory [21] and associative network perspectives on meaning transfer [41], we show that collaboration type functions as a higher-order marketplace cue, calibrating the inclusion–differentiation trade-off inherent in brand positioning. This study extends influencer research, which has traditionally focused on follower size or disclosure style [5,51], by elevating partnership architecture to a theoretically consequential predictor of brand attitude. More broadly, we refine ODT by demonstrating its attitudinal consequences at the brand level, beyond the group or product contexts examined in prior work.

Our second contribution clarifies why and for whom collaboration architecture matters by identifying perceived brand innovation as the central psychological mechanism and Need for Uniqueness (NFU) and category expertise as key boundary conditions. Mediation analyses indicate that cross-niche partnerships enhance brand attitude entirely through heightened innovation inferences, whereas alternative mechanisms such as curiosity remain inactive. This pattern aligns with signaling theory and research linking boundary spanning to perceptions of exploratory competence [4]. Moderation tests further reveal that the indirect effect is amplified among consumers high in NFU [44] but attenuated among experts who prioritize depth over novelty [47]. By integrating these dual contingencies into a single process model, this study advances recent influencer frameworks that have considered audience heterogeneity only descriptively [16]. This conditional mediation account enriches consumer identity theorizing while refining knowledge-based perspectives on persuasion effectiveness [52].

Finally, this research introduces influencer collaboration architecture as a market-level instantiation of Optimal Distinctiveness, offering a novel theoretical lens for understanding how brands can balance authenticity with progressiveness in algorithm-mediated social commerce environments. Conceptualizing cross-niche partnerships as hybrid identity signals that simultaneously borrow legitimacy from established categories and project creative divergence [26], we extend ODT beyond its traditional group or product design applications [23] into dynamic, co-created brand ecosystems. This perspective also nuances persuasion knowledge accounts by demonstrating that collaboration breadth, rather than sponsorship disclosure per se, shapes consumers’ interpretative frames when engaging with branded content [6]. Consequently, our framework encourages future research to integrate platform algorithms, creator networks, and brand meaning systems in multi-layered analyses of marketplace distinctiveness. For practitioners, it delineates collaboration scope as a strategic lever for achieving the delicate balance between relevance and originality.

5.2. Practical Contribution

Brand managers, influencer agencies, and platform sales teams can directly leverage the insights from our experiments when selecting collaboration formats. Because partnership type systematically shapes brand attitude, the first tactical step is audience segmentation. For campaigns targeting novelty-seeking novices, agencies should orchestrate cross-niche pairings that visually juxtapose distinct domains; for example, in our studies, matching a fitness creator with a gourmet snack brand increased brand attitude by nearly one scale point. Conversely, when the primary audience consists of category experts who value depth, managers should remain within the focal niche, as the same-niche sneaker collaboration generated the strongest favorability among knowledgeable followers. Platforms can operationalize this rule in campaign-planning dashboards, flagging high-expertise clusters so that sales teams propose the attitude-maximizing collaboration format, ultimately enhancing return on advertising spend.

Perceived brand innovation is the principal mechanism through which cross-niche partnerships convert attention into goodwill, fully mediating their effect, whereas curiosity alone did not. Practitioners can amplify outcomes by making the innovation signal salient. For cross-niche pairings, co-develop a tangible micro-innovation, such as a limited-edition flavor, so that the collaboration embodies experimentation rather than simple co-promotion. To harness moderating effects, sequence audiences strategically: launch the partnership first to high-NFU segments via seed lists or exclusive drops, allowing their sharing to legitimize the novelty for broader markets. When targeting expert consumers, complement cross-niche visuals with detailed technical briefs, or, if resources are constrained, pivot to same-niche partners that inherently convey depth. Aligning activation tactics with NFU and expertise profiles strengthens perceived innovation and amplifies attitudinal gains for target segments.

Message testing across our studies indicates that the collaborator’s domain label is the key cue, rather than extensive rationale. The most effective executions foreground partner contrast both visually and linguistically within three seconds. A cross-niche post should feature a split-screen image—e.g., gourmet burger meets fitness tracker—paired with a concise headline such as “Flavor Meets Performance”, fusing categories to elicit innovation inferences. Same-niche executions should emphasize shared mastery; for instance, a beauty-plus-beauty collaboration could headline “Two Experts, One Finish”, reinforcing depth cues for expert audiences. Copy should remain under twenty-five words, employ active verbs, and avoid jargon that competes with the juxtaposition. Harmonizing color palettes across domains ensures novelty feels coherent and perceived risk remains low for a broader audience.

Because domain labels carry meaning across markets, these collaboration guidelines generalize internationally, though subtle adaptations enhance local relevance. In collectivist cultures, novelty signals can threaten harmony; cross-niche pairings should be framed as community enrichment rather than individual expression, such as a tech-and-tea collaboration in China emphasizing shared wellness rituals. In individualistic contexts, differentiation benefits may be highlighted, aligning with high-NFU insights. Where language diversity limits comprehension, leverage recognizable iconography—pairing a soccer ball with a chef’s knife communicates athletic-culinary fusion without words. Color palettes can cross borders, combining each niche’s hue to signal legitimacy universally. In markets with lower category expertise, supplement visuals with micro-tutorials delivered via story highlights, ensuring the innovation cue remains accessible and attitudes improve globally.

5.3. Limitations

This research is subject to several limitations. First, all four experiments relied on single-exposure, vignette-based stimuli and self-reported attitudes; incorporating longitudinal field data that capture actual click-throughs or purchase behavior would strengthen external validity [1]. Second, collaboration distance was operationalized dichotomously as same- versus cross-niche, potentially obscuring non-linear effects predicted by Optimal Distinctiveness Theory at extreme categorical distances [21]. Future research could manipulate incremental distance levels or employ semantic network metrics to examine curvilinear responses. Third, the samples were drawn from U.S.-based crowdsourcing panels with moderate age variability, leaving the generalizability across cultures and generations untested. Replicating the design in collectivist contexts or among Gen-Z–heavy TikTok users may yield different innovation inferences due to divergent expertise schemata [47]. Addressing these limitations through multimethod designs, finer-grained distance measures, and cross-cultural sampling would enhance theoretical precision and provide managers with more actionable guidance for segmenting audiences and aligning campaigns with platform algorithms. Participants in all studies were recruited from online platforms (MTurk and Prolific). Although we implemented attention-check questions and fixed exposure times to ensure data quality, the samples still have certain limitations. Online samples may not fully represent the broader consumer population in terms of demographic and psychological characteristics, which could affect the external validity of the findings. Future research could replicate and extend our findings in more natural settings with more representative samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and J.F.; methodology, X.W. and J.F.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, X.W. and H.Z.; data curation, X.W. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, J.F., H.Z. and M.K.; supervision, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chengdu Philosophy and Social Science Research Base, grant number LD2024Z10; the Deyang Philosophy and Social Science Key Research Base – Culture and Tourism Development Research Center, grant number WHLY2025005; and the System Science and Enterprise Development Research Center, grant number XQ25C09. The APC was funded by the above grants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Southwest Jiaotong University (protocol code IRB-2025-SEM-0932B and date of approval: 5 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article. No additional datasets were generated or analyzed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Stimuli Used in Study 1

Appendix B. Stimuli Used in Study 2

Appendix C. Stimuli Used in Study 3

Appendix D. Stimuli Used in Study 4

| Study | Main Purposes | Findings | Sample Size and Main Results |

| Study1 | To test whether same-niche influencer-influencer collaborations lead to more favorable brand attitudes than cross-niche influencer-brand collaborations. | Manipulation check confirmed the design; category-congruent collaborations enhanced brand attitude. | 200 participants (MTurk). Same-niche collaboration produced higher brand attitudes (M = 5.39) than cross-niche collaboration (M = 4.71), F(1, 198) = 23.07, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10. |

| Study2 | To test whether cross-niche (vs. same-niche) influencer collaborations increase brand attitude through perceived brand innovation and to assess curiosity as an alternative mediator. | Cross-niche collaborations improved brand attitude because they signaled greater innovativeness, not because of curiosity. | 200 U.S. participants (Prolific). Brand attitude: Cross-niche > Same-niche (M = 5.62 vs. 4.88), F(1, 198) = 28.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13. Mediation: Perceived brand innovation fully mediated the effect (indirect B = 0.25, 95% CI [0.12, 0.39]); curiosity did not mediate. Manipulation check: F(1, 198) = 296.34, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.60. |

| Study3 | To test whether the positive effect of cross-niche influencer collaborations on brand attitude is moderated by Need for Uniqueness (NFU)—stronger for high-NFU consumers and weaker for low-NFU consumers. | Cross-niche collaborations enhance brand attitude only for high-NFU consumers, confirming NFU as a key boundary condition. | N400 U.S. participants (Prolific). Manipulation checks: Collaboration type (F(1, 398) = 1178.94, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.75); NFU prime (F(1, 398) = 1024.67, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.72). Brand attitude: Significant interaction between collaboration type and NFU (F(1, 398) = 20.36, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05). High-NFU: Cross-niche > Same-niche (M = 6.01 vs. 5.12, p < 0.001). Low-NFU: No significant difference (M = 5.28 vs. 5.14, p = 0.318). |

| Study4 | To examine whether the positive effect of cross-niche collaborations on brand attitude is moderated by Need for Uniqueness (NFU). | Cross-niche advantage occurs only for high-NFU consumers, confirming NFU as a key moderator. | N = 400 (Prolific). Manipulation checks successful for collaboration type (F(1, 398) = 1178.94, p < 0.001) and NFU prime (F(1, 398) = 1024.67, p < 0.001). Brand attitude showed a significant interaction (F(1, 398) = 20.36, p < 0.001): High NFU → Cross-niche > Same-niche (M = 6.01 vs. 5.12, p < 0.001). Low NFU → No difference (M = 5.28 vs. 5.14, p = 0.318). |

References

- Association of National Advertisers. Guidelines for Awareness, Engagement, and Conversion Metrics in Influencer Marketing. 2024. Available online: https://www.ana.net/content/show/id/74274 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Influencer Marketing Hub. Influencer Marketing Benchmark Report. 2025. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- StackInfluence. Micro-Influencer Cross-Channel Collaborations Report. 2025. Available online: https://stackinfluence.com/micro-influencer-cross-channel-collaborations/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G. How does brand innovativeness affect brand loyalty? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Aguiar, T.D.; van Noort, G. How influencer follower size relates to brand responses. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Steils, N.; Martin, A.; Toti, J.-F. Managing the transparency paradox of social-media influencer disclosures. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 860–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K.; Taheran, F. How social media influencer collaborations are perceived by consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 154, 113319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filali-Boissy, D.; Jouny-Rivier, E.; Perren, R. Co-creating content with brands: Insights from influencers’ perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 162, 113487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, S.; Lang, B.; Lee, M.; Bentham, C. How mega- and micro-influencers strategically manage authenticity. J. Advert. Res. 2025, 65, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Jin, X.; Sheng, G.; Lin, Z. Seeking effective fit: The impact of brand-influencer fit types on consumer brand attitude. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HireInfluence. The Top Trends in Influencer Marketing for 2025. 2025. Available online: https://hireinfluence.com/blog/trends-in-influencer-marketing/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Ballester, E.; Ruiz, C.; Rubio, N.; Veloutsou, C. We match! Building online brand engagement behaviours through emotional and rational processes. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 162, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, X.; Kannan, P.K. Influencer mix strategies in livestream commerce: Impact on product sales. J. Mark. 2024, 88, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervyn, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Malone, C. Brands as intentional agents framework: How perceived intentions and ability can map brand perception. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, J.R.; Campbell, C.; Sands, S. What drives consumers to engage with influencers? J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozharliev, R.; Rossi, D.; De Angelis, M. A picture says more than a thousand words: Using consumer neuroscience to study Instagram users’ responses to influencer advertising. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 59, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, A. Consumer innovativeness and organic food adoption: The mediation effects of consumer knowledge and attitudes. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Dinh, T.D.; Ewe, S.Y. The more followers the better? The impact of food influencers on consumer behaviour in the social media context. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 4018–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shao, Z.; Wang, K. Does your company have the right influencer? Influencer type and tourism brand personality. Tour. Manag. 2025, 107, 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Veloutsou, C.; Arnould, E. Creating identification with brand communities on Twitter: The balance between need for affiliation and need for uniqueness. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B.; Chen, Y.R. Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cillo, P.; Troilo, G. Multilevel optimal distinctiveness: Examining the impact of within- and between-organization distinctiveness of product design on market performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 1234–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, P.; Sengupta, S. Optimal distinctiveness across revenue models: Performance effects of differentiation of paid and free products in a mobile app market. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 1875–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, P. Optimal distinctiveness in platform markets: Leveraging complementors as legitimacy buffers. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 1859–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, D.; Wirtz, J.; Zeithaml, V. What’s the value of being different when everyone is? The effects of distinctiveness on performance in homogeneous versus heterogeneous categories. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 44, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cho, J.; Collins, C. Engaging in a culturally mismatched thinking style increases the preference for familiar consumer options for analytic but not holistic thinkers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Boeing, M.; Brodbeck, F. Optimal distinctiveness: Broadening the interface between institutional theory and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 635–657. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, C.; Batra, R. Positioning for optimal distinctiveness: How firms manage competitive and institutional pressures under dynamic and complex environment. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, J. The color of choice: The influence of presenting product information in color on the compromise effect. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, V.W.A.; Balabanis, G. The role of brand strength, type, image and product-category fit in retail brand collaborations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Xue, Z.; He, J. How brand coolness influences customers’ willingness to co-create? The mediating effect of customer inspiration and the moderating effect of customer interaction. J. Brand Manag. 2024, 31, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venciute, D.; Mackeviciene, I.; Kuslys, M.; Correia, R.F. The role of influencer–follower congruence in the relationship between influencer marketing and purchase behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, R.; Liao, J. Mega-influencer follower effect: The mediating role of sense of control in brand attitudes, purchase intentions and engagement. Eur. J. Mark. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Muqaddam, A.; Miller, S. The effects of the visual presentation of an Influencer’s Extroversion on perceived credibility and purchase intentions—Moderated by personality matching with the audience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brexendorf, T.O.; Keller, K.L. Leveraging the corporate brand: The importance of corporate brand innovativeness and brand architecture. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1530–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Qu, Y. Brand extension or co-branding: The consumer’s attribution of responsibility to the crossover strategies of heritage brands. J. Consum. Res. 2025, 52, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhou, Z. Innovative glossiness and traditional matteness: Impact of product surface on consumer perception and evaluation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tong, Y.; Ye, M. How product-background color combinations influence perceived brand innovativeness. J. Mark. Res. 2024, 61, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, C.K.; Noseworthy, T.J.; Dawar, N. Asymmetric consequences of radical innovations on category representations of competing brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, I.; Faems, D.; de Faria, P. Coopetition and product innovation performance: The role of internal knowledge sharing mechanisms. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R.; Fromkin, H.L. Uniqueness: The Human Pursuit of Difference; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K.T.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G.L. Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Rozsnyai, O.; Bertrandias, L. New technological attributes and willingness to pay: The role of social innovativeness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranega, A.Y.; Soriano, D.R.; Del Val Núñez, M.T.; Vázquez, J.S. Innovative behavior of consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of consumer expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, G. The structure of value: Accounting for taste. In Advances in Consumer Research; Holbrook, M.B., Hirschman, E.C., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 1982; Volume 9, pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.M.; Fu, T.; Duan, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y. The overlapping effect: Impact of product display on price–quality judgments. Mark. Lett. 2024, 35, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Duan, S. Health-Related Advertising: Leveraging Virtual and Human Influencers to Encourage Health Behaviors. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Kou, S.; Duan, S.; Wang, Y.; Lü, K. Effect of Human Images in Advertisements on Consumers’ Experiential Purchase Intentions. J. Advert. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).