Abstract

Short-form video platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have become influential social commerce and interactive marketing tools, shaping consumer attitudes and behaviors beyond the digital environment. This study examines how short-form video content affects consumers’ intention to visit destination retail stores by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) with the constructs of perceived usefulness, curiosity, and envy. Data from 423 Gen Z and Millennial consumers were collected through an online survey and analyzed using structural equation modeling. The findings indicate that perceived usefulness, curiosity, and envy significantly influence attitudes toward short-form video content, which subsequently drive intentions to visit destination retailers. Social influence also emerged as a stronger predictor of behavioral intention than practical barriers such as cost or accessibility, underscoring the importance of peer validation in motivating digital-to-physical consumer behavior. This study advances electronic commerce research by extending TPB to short-form video marketing and identifying key emotional and cognitive triggers that facilitate consumer engagement. Practically, the results highlight strategies for retailers to develop video campaigns that spark curiosity, evoke aspirational emotions, and leverage social endorsement. More broadly, the study demonstrates how short-form video platforms operate as interactive ecosystems that merge emotional engagement, social validation, and technological affordances to shape hybrid consumer journeys from digital exposure to in-store action.

1. Introduction

Short-form video platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have rapidly evolved from peripheral entertainment tools into central drivers of consumer perception and retail engagement. These platforms facilitate product discovery while embedding users within algorithmically curated networks of peer influence, aesthetic cues, and brand storytelling that blur traditional boundaries between digital interaction and physical shopping. More than entertainment, short-form video operates as a powerful engine of social commerce, delivering immersive and visually rich content that elicits cognitive and emotional responses capable of shaping destination choices in retailing []. Unlike traditional promotional formats, video posts integrate narrative, dynamic imagery, and interactive features that foster deeper engagement and more enduring brand impressions []. As electronic commerce increasingly spans digital and physical domains, understanding how short-form video shapes consumer decision-making has become essential for scholars and practitioners alike.

Destination retailers, or stores that motivate consumers to make special trips due to unique offerings, immersive atmospheres, or exclusive events, represent a particularly relevant context for examining this phenomenon []. These retailers rely heavily on curated experiences and brand storytelling to attract visitors, a dynamic intensified in the post-pandemic retail landscape. Periods of restricted in-person shopping heightened consumer desire for elevated, leisure-oriented retail experiences, especially among Gen Z and Millennial consumers who are also intensive users of video-based social media []. Brands such as Dior, Lululemon, and IKEA now use short-form video to showcase concept stores, experiential spaces, and pop-up events, reaching audiences far beyond their physical locations. As a result, short-form video has become a potent mechanism for bridging the digital-to-physical gap by converting online impressions into offline store traffic. Despite growing scholarly interest in social media’s role in shaping consumer behavior, research specifically examining short-form video as a driver of destination retail engagement remains limited within the electronic commerce literature.

Although prior studies have examined the influence of social media on consumer decisions, relatively little attention has been paid to the persuasive mechanisms embedded within short-form video content, particularly how such content motivates consumers to visit destination retailers. This study addresses that gap by extending the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [] to account for key affective and cognitive triggers prevalent in short-form video environments. Traditional TPB models often overlook variables such as perceived usefulness, curiosity, and envy, despite their centrality to how consumers evaluate and respond to digital media. These constructs may offer deeper insights into the psychological mechanisms that shape visit intentions in video-based social media contexts []. Integrating them into TPB provides an opportunity to extend theoretical understanding and address an important research gap.

This study contributes to the literature by examining how short-form video content influences consumer intention to visit destination retail stores through an expanded TPB framework. Using survey data from digital-native Gen Z and Millennial consumers, we empirically test how perceived usefulness, curiosity, and envy shape attitudes and behavioral intentions, while also assessing the relative roles of social influence and perceived behavioral barriers. “Digital natives” are individuals who have grown up in technology-saturated environments and demonstrate intuitive proficiency with digital media, particularly in areas involving communication, identity formation, and consumption [,,]. These cohorts are not passive observers but active participants within algorithmic media spaces that shape their preferences and experiences. By situating short-form video as an emerging e-commerce mechanism characterized by technological affordances, participatory content features, and peer-driven storytelling, this study aligns with contemporary research on interactive marketing. The findings highlight both theoretical and practical implications, demonstrating how short-form video functions not only as a communication medium but also as a participatory interface through which consumers engage, react, and co-create meaning in real time—ultimately influencing their intentions to visit physical retail destinations [].

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Short-Form Video as a Digital Persuasion Mechanism

Short-form video platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have become dominant spaces for digital persuasion, characterized by algorithmic amplification, low cognitive load, and emotionally resonant content delivery [,]. Unlike static images or text-based posts, short-form videos provide sensory-rich stimuli that trigger both immediate cognitive appraisal and heightened affective responses []. Their brevity, visual dynamism, and capacity for seamless social sharing make these formats highly engaging []. These elements enhance memorability and emotional impact compared to many traditional advertising formats, although persuasive effectiveness may vary depending on platform, content type, and audience. This persuasive potential is further intensified by peer-, influencer-, and brand-generated content that embeds product cues within lifestyle narratives, effectively bridging digital impressions with physical brand engagement [].

Research also shows that video-centered social media supports socially facilitated discovery, where users’ exploratory behaviors are shaped by platform mechanisms as well as by social validation from views, comments, and shares []. Consequently, short-form video content functions as an effective consumer socialization tool, strengthening brand awareness, preference formation, and behavioral intentions across both retail and tourism contexts [,].

2.2. From Digital Exposure to Retail Destination Visitation

Prior research in tourism and retail marketing demonstrates that digital media influences not only what consumers purchase but also where they choose to go, particularly in visually driven destination contexts []. Retail environments that operate as destination spaces, such as flagship stores, concept locations, and pop-up events, increasingly rely on digital platforms to create “anticipatory experiences” that cultivate emotional connection and spatial desire before the physical visit occurs []. Short-form video enhances this dynamic by offering a more immersive form of digital place-making than most traditional advertising formats. This effect is particularly pronounced among Gen Z and Millennial consumers, who view shopping not merely as a transactional act but as a leisure activity embedded within lifestyle exploration and self-presentation [].

2.3. Theoretical Framework

This study adopts the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [] as the core theoretical foundation for examining consumers’ visit intentions in the context of short-form video marketing. According to TPB, behavioral intention is shaped by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC). While TPB has been widely applied to digital decision-making contexts, its traditional formulation may not fully capture the emotionally charged and technologically interactive aspects of social video environments.

To address these limitations, this study integrates the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [] and its extensions TAM2 [] and TAM3 []. TAM explains how perceptions of usefulness and ease of use influence attitudes and behavioral intentions toward technology. Within the expanded TPB–TAM framework, perceived usefulness reflects the extent to which users view short-form video as helpful for discovering and evaluating destination retail locations. This construct acts not only as a rational belief but also as a mediator shaped by the persuasive affordances of video-based content, such as experiential previews or product demonstrations. Integrating TAM concepts strengthens conceptual clarity by combining cognitive appraisals with the affective and social drivers highlighted in TPB, especially in digital-to-physical consumer journeys.

Building on this foundation, the framework incorporates curiosity and envy to capture emotional and motivational processes central to short-form video engagement. Curiosity, rooted in Loewenstein’s information-gap theory [] and the exploration–exploitation framework [], reflects an intrinsic motivational state triggered by novel or aesthetically stimulating stimuli, key characteristics of short-form video platforms. In retail settings, short videos often serve as sensory “teasers” that prompt viewers to complete the experiential narrative through physical visitation.

Envy, particularly benign and aspirational forms [,], reflects affective responses linked to upward social comparison (Social Comparison Theory). Exposure to peer- or influencer-generated retail content may evoke aspirational desire, motivate identity alignment, and inspire offline behavioral expression.

Recent interactive marketing scholarship further supports integrating these mechanisms. Wei [] shows that dynamic social features, such as real-time comments or “barrage” overlays, heighten emotional contagion and amplify engagement. Tong and Chan [] similarly demonstrate that platform-native interactive elements, such as swiping, live polls, and guided walkthroughs, transform passive viewers into active participants, validating the inclusion of curiosity and perceived usefulness as key motivational constructs. Vo et al. [] additionally underscore the importance of authenticity across digital touchpoints, highlighting how relatable and unscripted video content can enhance trust and strengthen engagement. These perspectives position short-form video as a hybrid communication form that merges technological affordances with affective persuasion.

While traditional digital marketing research has emphasized rational drivers such as information quality and ease of use, emerging evidence highlights the significance of emotional and social triggers, especially in experiential consumption contexts []. In this study, perceived usefulness, curiosity, and envy are integrated into an extended TPB framework to reflect how digital stimuli shape multidimensional cognitive and emotional responses. Perceived usefulness captures cognitive evaluations that short-form video provides practical guidance for store visitation []. Curiosity reflects a desire to resolve information gaps or experience novelty [,]. Envy captures affective motivation shaped by social comparison and aspirational consumption []. Together, these constructs offer a more comprehensive explanation of behavioral intention formation in destination retail contexts than TPB alone.

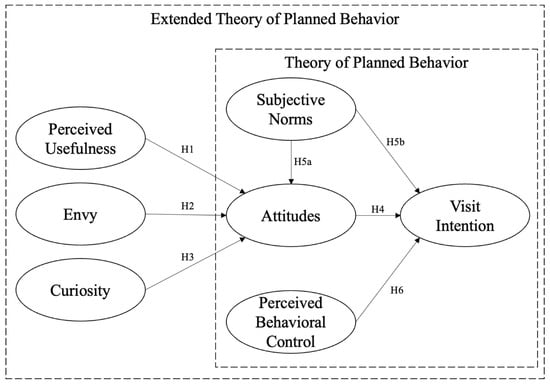

By synthesizing insights from TPB, TAM, Social Comparison Theory (SCT), and the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) paradigm, this study advances theory in two ways. First, it extends TPB’s explanatory power into visually rich, algorithmically curated digital ecosystems where behavioral intentions are shaped by emotional, social, and technological stimuli. Second, it responds to calls for multi-theoretical integration in digital consumption research, especially in hybrid retail contexts where online persuasion translates into offline behavior. By conceptualizing short-form video as an interactive marketing medium, this framework clarifies how interactivity, emotional contagion, and authenticity jointly shape consumer intentions within environments that merge social participation and digital communication. Figure 1 presents the proposed conceptual model.

Figure 1.

Extended TPB–TAM Framework for Short-Form Video Marketing.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.4.1. Perceived Usefulness

Perceived usefulness reflects the extent to which a product or system enhances task performance. Individuals are more likely to adopt behaviors when they believe a tool supports goal attainment []. In this study, perceived usefulness refers to whether consumers view short-form videos as a helpful resource for evaluating or selecting destination retailers. Accordingly:

H1.

Perceived usefulness positively influences attitudes.

2.4.2. Envy

Envy in consumer contexts can be dispositional, a general tendency to feel envious, or situational, arising within specific comparison scenarios []. Short-form video increases exposure to aspirational retail content, expanding the audience who can discover and engage with destination retailers [,,]. Benign envy motivates self-improvement and is nonhostile in nature [,,]. In social media settings, benign envy often manifests as a desire to experience what others display, making it a potent motivator in consumption contexts. Thus:

H2.

Envy positively influences attitudes.

2.4.3. Curiosity

Curiosity is a motivational drive to explore and acquire information, often triggered by novelty or information gaps [,]. In digital contexts, curiosity increases engagement with new or challenging stimuli and positively influences perceived enjoyment and ease of use [,]. Short-form videos often serve as experiential teasers that spark curiosity about retail locations. Therefore:

H3.

Curiosity positively influences attitudes.

2.4.4. TPB Variables

A substantial body of research demonstrates that affect influences consumer behavior []. Positive emotions generated through favorable destination imagery, for example, elevate intention to visit []. Prior studies suggest that positive attitudes enhance the probability of undertaking specific actions through psychological processes that strengthen motivation and readiness to act [,,]. Travel intention reflects consumers’ perceived likelihood of engaging with a destination and captures both attitudinal evaluations and motivational drive [,]. Within TPB, attitude is a central predictor of behavioral intention. Favorable attitudes increase the likelihood of performing a behavior by strengthening motivation and readiness to act [,,]. Thus:

H4.

Attitudes positively influence visit intention.

Subjective norms reflect perceived social expectations and pressures that influence behavioral decisions []. Family, peers, and other referent groups can significantly shape consumer intentions [,]. In the context of destination retail, social motivation and peer validation may encourage store visitation. Therefore:

H5a.

Subjective norms positively influence attitudes.

H5b.

Subjective norms positively influence visit intention.

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to individuals’ perceptions of difficulty or ease of performing a behavior, based on resource availability and anticipated obstacles []. Prior research demonstrates that increased resources enhance perceived control, which in turn shapes purchase and visitation intentions [,,]. Visiting destination retailers requires time, planning, and financial resources; thus, PBC is expected to influence visit intention:

H6.

Perceived behavioral control positively influences visit intention.

3. Materials and Methods

A quantitative research design was employed to systematically examine the relationships between short-form video features and consumers’ intentions to visit destination retailers. This approach is appropriate for theory testing using latent constructs and mediation pathways and aligns with prior behavioral studies employing the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and related technology-adoption models. Data were collected through an online questionnaire administered via the Qualtrics platform, which enabled efficient access to digitally active respondents and supported the measurement of attitudinal and behavioral constructs. The study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), ensuring compliance with ethical standards before data collection commenced.

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedures

A purposive sampling strategy targeted “young consumers,” specifically individuals from Generation Z (born approximately 1997–2012) and younger Millennials (born approximately 1981–1996). These cohorts were selected because of their well-documented digital nativity, frequent engagement with short-form video platforms, and outsized influence on contemporary retail and social commerce trends []. Respondents were screened for high activity on video-based social media, operationalized as spending at least one hour per day on TikTok, Instagram Reels, or YouTube Shorts. This ensured the sample reflected habitual users whose perceptions and behaviors are meaningfully shaped by such platforms [,].

Data were collected exclusively from U.S. consumers. This geographic focus is theoretically justified because the United States has a mature retail ecosystem, widespread adoption of omnichannel strategies, and one of the highest short-form video penetration rates globally (81% social media usage among adults) []. These characteristics make the U.S. an appropriate and relevant context for investigating digital-to-physical influence mechanisms in retail settings. We acknowledge that this focus limits cross-cultural generalizability, which is addressed in Section 7.

Participants were recruited through Qualtrics Research Panels, enabling targeted screening based on age, platform usage, and prior exposure to retail video content. Two attention checks were embedded in the survey, and only participants who passed both checks were retained. Data collection occurred across six months (June–November), reducing temporal bias and accounting for seasonal differences in retail exposure.

Responses exhibiting straight-lining behavior, incorrect attention checks, or unrealistically short completion times (<2 min) were removed. After cleaning, a final sample of 311 valid responses was obtained (effective retention rate: 74%). All procedures were approved under IRB Protocol #23-208.

3.2. Instruments

To capture the constructs outlined in the conceptual framework, the survey instrument incorporated screening items, attention checks, demographic measures, and multi-item scales that demonstrated reliability above the conventional threshold [,]. Perceived usefulness was measured with four items adapted from Guo et al. [], while envy was assessed using four items derived from Fournier and Alvarez [] and Ivens et al. []. Curiosity was measured with three items from Agarwal and Karahanna []. Attitudes were evaluated with four items adapted from Park et al. [] and Wakefield and Baker []. Subjective norms were examined with four items developed by Singh et al. [], and perceived behavioral control was assessed using three items taken from Taylor and Todd []. Finally, visit intention was measured with a three-item scale adapted from Fu et al. []. Items for each construct were initially drawn from established scales in prior research. During the pilot test and subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), items with factor loadings below 0.60 or showing high cross-loadings were removed to improve construct reliability and model fit []. Final item selection was therefore based on both theoretical alignment and empirical validation. Employing these well-established scales ensured measurement validity and supported comparability with prior consumer behavior studies.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using both SPSS 27 and Mplus 9 software packages. The analysis began with descriptive statistics and frequency distributions to summarize the demographic characteristics of respondents and to provide practical insights into audience targeting. Next, reliability and preliminary validity were examined through Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis [,].

In addition to procedural safeguards, such as ensuring anonymity, clarifying that there were no right or wrong answers, and separating dependent and independent variables, this study statistically tested for common method bias (CMB) using two contemporary approaches: (1) the marker variable technique, and (2) full collinearity assessment via variance inflation factor (VIF). To reduce common method bias (CMB), multiple procedural remedies were employed, ensuring anonymity, emphasizing that there were no right or wrong answers, separating independent and dependent variable sections, and embedding attention checks. In addition, statistical controls were employed using two contemporary techniques (1) marker variable technique, a theoretically unrelated marker variable was included; it showed negligible correlations with the main constructs, and (2) full collinearity assessment (VIF), where all constructs exhibited VIF values below 3.3, following Kock’s [] recommendation that this threshold indicates the absence of problematic CMB. These methods are widely recognized as superior to the traditionally used but now-criticized Harman’s single-factor test [,].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted within the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework to validate the dimensionality of the constructs. Following an initial CFA, items with standardized loadings below 0.60 were removed to enhance construct reliability. After conducting initial CFA, low-loading (loading < 0.60) and redundant items were removed to strengthen construct reliability. The revised model demonstrated a substantially improved fit (χ2/df = 2.55, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.067, SRMR = 0.045), meeting recommended thresholds []. Discriminant validity was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) [], where all construct pairs fell below the 0.85 cut-off.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized relationships. SEM is appropriate for studies examining mediating pathways and latent constructs, and its use in cross-sectional research is well established for early-stage theory development. Although cross-sectional data cannot determine causality, SEM provides rigorous tests of association strength, theoretical coherence, and model plausibility, key goals of this study. Future research directions (e.g., experiments, longitudinal designs) are outlined in the Limitations. Collectively, these analytical techniques yield theoretical insights into the psychological mechanisms linking short-form video content with destination retail visitation, while providing robust empirical support for the proposed conceptual model.

4. Results

After data collection, the researchers implemented listwise deletion to manage missing data and removed surveys in which participants failed the screener or attention check items. Of the 358 surveys obtained, 311 were usable, resulting in an effective response rate of 86.9%. The demographic profile of the sample revealed that 24% of participants identified as male and 73% as female, with the majority (79%) aged between 18 and 24. More than half of the respondents were Caucasian (54%), most had completed a high school diploma or associate’s degree (77%), and the majority reported annual incomes of $50,000 or less (81%). Comprehensive demographic data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

Reliability and validity were evaluated using SPSS. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) employing principal component extraction with varimax rotation identified seven distinct constructs which together accounted for 62% of the total variance. Cronbach’s Alpha values for all constructs ranged between 0.71 and 0.90, with an average Alpha of 0.83, indicating strong internal consistency [,]. Table 2 presents the specific Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for each construct. To evaluate the presence of common method bias, a Harman’s one-factor test was performed. The analysis indicated that the leading factor explained 46% of the variance, which is under the 50% criterion [,].

Table 2.

Standardized factor loading, construct reliability (CR), variance (AVE), and heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) for variables in the measurement model.

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model’s suitability was tested through CFA in MPlus, applying maximum-likelihood estimation with a covariance matrix. The model consisted of seven latent variables represented by 22 items (Table 2). The results demonstrated an acceptable level of fit (χ2 = 2.55, df = 188, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.067, SRMR = 0.045). Reliability was demonstrated with composite reliability (CR) scores higher than 0.70, and convergent validity was verified since average variance extracted (AVE) values were greater than 0.50 []. Furthermore, discriminant validity was confirmed because each construct’s AVE exceeded the squared inter-construct correlations. To further substantiate these outcomes, the factor structure was cross-checked with a correlation matrix derived in SPSS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations among the variables derived from the measurement model.

4.3. Structural Model: Hypotheses Testing Results

The proposed relationships were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) in MPlus. The model demonstrated acceptable overall fit (χ2 = 52.53; df = 5; p = 0.0; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.10; SRMR = 0.06). The dependent variables showed moderate to strong explanatory power: attitudes (R2 = 0.57) and visit intention (R2 = 0.63), indicating that the proposed antecedents sufficiently explain variations in both constructs.

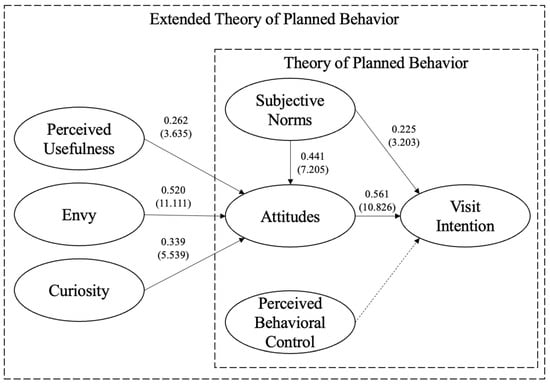

Following Byrne’s [] guideline of a t-value threshold of 2.00 for significance, the analysis revealed that perceived usefulness exerted a positive influence on attitudes (H1; β = 0.24, t = 3.635, p < 0.001). Envy emerged as a strong positive predictor of attitudes (H2; β = 0.29 t = 11.111, p < 0.001), while curiosity also demonstrated a significant positive effect (H3; β = 0.36 t = 5.539, p < 0.001). Attitudes were found to significantly drive visit intention (H4; β = 0.41, t = 10.826, p < 0.001). In addition, subjective norms had positive effects on both attitudes (H5a; β = 0.40, t = 7.205, p < 0.001) and visit intention (H5b; β = 0.29, t = 3.203, p < 0.01). By contrast, perceived behavioral control did not significantly predict visit intention (H6; β = −0.06, t = −0.611, p = 0.541), indicating that resource availability did not play a decisive role in consumers’ intention to visit destination retailers. Thus, the feasibility perceptions such as time, cost, or personal agency were not central to the decision to visit destination retailers as influenced by short-form video content. Effect size (f2) calculations indicate that attitudes (0.35) exerted a substantial influence on visit intention, while subjective norms (0.18) and PBC (<0.01) exerted medium and negligible effects, respectively. The final model can be viewed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Latent model showing structural path coefficients. Standardized estimates shown (t-values in parentheses); p < 0.0 for solid lines; Dash arrow designates nonsignificant relationship.

5. Discussion

This study examined how short-form video content influences consumers’ intentions to visit destination retail stores through an extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) framework. The findings demonstrate that cognitive, affective, and social mechanisms each play a meaningful role in shaping consumer attitudes toward video content, which subsequently drive visit intentions. This reinforces the core premise of the expanded TPB model: digital persuasion in short-form media environments is multi-layered, combining rational evaluations (usefulness), motivational triggers (curiosity), and emotional processes (benign envy) with social validation signals to influence behavioral intention.

5.1. Cognitive, Emotional, and Motivational Drivers of Attitudes

Perceived usefulness emerged as a significant predictor of attitudes, consistent with TAM research and supporting the integration of technology-adoption logic into TPB. This suggests that consumers value short-form video content not only for its entertainment qualities but also as a practical tool for evaluating retail destinations. In the context of visually rich, algorithmically curated social media environments, cognitive assessments remain an important component of consumer judgment.

Curiosity also significantly influenced attitudes, affirming its role as a motivational driver in video-based media. Short-form videos often present fragmented, teaser-like store imagery that generates an information gap, prompting users to explore further. This supports the inclusion of curiosity within the S–O–R–inspired extension of TPB, as video affordances stimulate exploratory responses that elevate consumer interest and shape positive attitudes.

Envy exerted the strongest influence on attitudes, highlighting the importance of aspirational and comparative emotional processes in digital consumption. This aligns with Social Comparison Theory and reflects the persuasive impact of influencer- or peer-generated content that portrays desirable retail experiences. The prominence of envy underscores the need for TPB-based models to better incorporate affective responses that extend beyond traditional rational evaluations.

5.2. Social Influence as a Dominant Predictor of Visit Intention

Subjective norms significantly predicted both attitudes and visit intentions, reflecting the heightened relevance of social validation in short-form video environments. Engagement metrics, creator credibility, and peer responses contribute to a normative climate in which store visitation becomes socially reinforced. This suggests that social influence may carry more persuasive weight than logistical feasibility in motivating destination-visitation behavior among younger consumers. The centrality of social norms in this study supports prior literature emphasizing peer-driven pathways in digital commerce. It also validates the theoretical integration of TPB with social video affordances that render consumption and engagement highly visible to one’s network.

5.3. The Unexpected Role of Perceived Behavioral Control

Contrary to classical TPB predictions, perceived behavioral control did not significantly influence visit intention. This finding suggests that when emotional and social drivers are strong, such as envy, curiosity, and peer approval, practical constraints (e.g., time, money, distance) may become less salient. For Gen Z and Millennial consumers accustomed to spontaneous and experience-oriented shopping behaviors, emotional and social triggers may overshadow logistical considerations.

This represents a novel theoretical insight: in hedonic or experiential retail contexts stimulated by short-form video, affective and normative influences can outweigh traditional determinants such as perceived control. This offers a promising direction for future TPB-based research in high-engagement digital domains.

5.4. Advancing Theory in Digital and Omnichannel Retailing

The findings contribute to digital marketing and retailing literature by demonstrating how video-based media operate as experiential activation cues that bridge digital engagement with offline action. Unlike linear decision models, the pathways stimulated by short-form video are immersive, emotional, and socially reinforced. This advances theory in three key ways: (1) It extends TPB into algorithmic, visually rich media environments where emotional resonance and social visibility interact with cognitive appraisal. (2) It demonstrates the relevance of integrating TAM, SCT, and curiosity theory to capture the multi-dimensional nature of video-induced intention formation. (3) It challenges long-standing assumptions about perceived behavioral control, suggesting new boundary conditions for TPB in hedonic and experiential contexts. Overall, the revised model illustrates how short-form video platforms reshape consumer journeys by intertwining affect, cognition, and social influence in a hybrid digital-to-physical persuasion process.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study offers several theoretical contributions that advance the application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and multi-theoretical modeling in digital and omnichannel retail contexts. First, the integration of perceived usefulness (TAM), curiosity (information-gap and exploration theories), and benign envy (Social Comparison Theory) with TPB demonstrates the need to expand behavioral intention models to account for the emotional and motivational dynamics of algorithmically curated video platforms. While TPB has traditionally emphasized rational evaluation and perceived behavioral control, our findings show that short-form video environments evoke affective triggers and exploratory motivations that meaningfully shape consumer attitudes. This hybrid approach, connecting cognitive, affective, and motivational pathways, provides an enriched theoretical foundation for understanding digital-to-physical persuasion.

Second, the study contributes to emerging literature on the digital–physical flow of consumer behavior, which emphasizes how digital media exposure translates into offline experiences. Unlike prior research focusing on online purchase intentions, this work shows that short-form videos act as experiential activation cues that encourage consumers to engage with physical retail environments. This advances theory by positioning video-based media not only as informational sources but as immersive, socially validated stimuli that initiate real-world retail engagement.

Third, the non-significant effect of perceived behavioral control introduces a boundary condition for TPB: in highly hedonic, experience-driven contexts, emotional and social influences may overshadow practical constraints. This suggests that intention formation in algorithmic media environments may follow different psychological dynamics than those predicted by classical TPB. This finding encourages further examination of how affective and normative pressures moderate or supersede perceived control in experiential consumption settings. Collectively, these contributions extend TPB to better account for the interactive, affect-laden, and socially networked nature of contemporary media ecosystems, offering a theoretically cohesive model for understanding video-induced consumer behavior in omnichannel retail.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings yield actionable insights for destination retailers seeking to convert digital impressions into physical foot traffic. First, leverage aspirational storytelling to activate benign envy. Envy emerged as the strongest attitudinal driver, suggesting that retailers should collaborate with influencers and customers who naturally convey desirable yet attainable experiences []. Short-form videos that highlight store aesthetics, exclusive merchandise, or “day-in-the-life” narratives can prompt consumers to want to replicate the experience.

Second, design teaser-based content to stimulate curiosity. Curiosity is triggered when videos present partial or incomplete information, such as glimpses of new collections, store features, or interactive experiences. Retailers should employ micro-narrative sequencing (e.g., multi-part storylines) to invite viewers to “fill in the gaps” through in-store visits. This approach aligns with how short-form platforms amplify exploratory behavior. Third, activate social norms through user-generated content (UGC). Subjective norms significantly influenced both attitudes and intentions, indicating the importance of social proof. Encouraging customers to post in-store videos, duet popular content, or participate in branded hashtag challenges can create a “social momentum effect” in which visiting the store becomes a socially validated action.

Fourth, prioritize emotional and social resonance over purely functional messaging. While informational content matters, emotionally charged and socially contagious videos were found to be more influential in shaping visitation intentions. Retailers should emphasize sensory-rich visuals, authentic human interactions, and narrative-driven clips rather than relying solely on product or price-based messaging. In alignment with the goals of interactive marketing, these strategies enable destination retailers to build hybrid customer journeys that seamlessly transition consumers from digital inspiration to physical experience. As short-form video platforms grow increasingly central to discovery and decision-making, retailers who design content around emotional engagement, social validation, and experiential intrigue will be best positioned to drive foot traffic and enhance brand relevance.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study is subject to several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, the elimination of low-loading or cross-loading items during scale purification may have affected the representativeness of certain constructs. Future studies could replicate the model using full scales or alternative item formulations to assess the robustness of these constructs across different contexts.

Second, data were collected exclusively in the United States, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to markets with different media habits, retail structures, or cultural norms surrounding social influence and experiential consumption. As the U.S. is a highly digitized and visually oriented consumer market, behaviors observed here may differ in countries with lower social media adoption, distinct age profiles, or alternative persuasion norms. Future research could replicate this study in diverse national contexts, such as emerging Asian markets or European economies, to examine how cultural, infrastructural, or socioeconomic factors moderate the relationship between short-form video engagement and offline retail intentions.

Third, the study relied on single-source, cross-sectional survey data, which may be susceptible to common method variance and mono-method bias. Although procedural and statistical steps were taken to minimize such bias, future research should seek to enhance external validity by employing multi-method approaches. For example, integrating survey-based perceptions with behavioral data (e.g., store visit logs, location-based tracking, or platform engagement metrics) or using longitudinal and experimental designs would allow for stronger causal inferences and greater generalizability across consumer segments and contexts.

Another limitation concerns the gender composition of the sample, which included a higher proportion of women than men. This imbalance may influence the generalizability of the findings, as prior research suggests that emotional and social responses to media stimuli can vary by gender, especially in relation to envy, self-presentation, and peer influence []. Future work could employ gender-balanced or gender-specific samples or conduct multigroup structural analyses to examine whether key relationships, such as the effects of curiosity or envy on visit intention, differ across gender groups. These insights would not only enhance theoretical nuance but also inform gender-sensitive retail and content marketing strategies.

In addition, future longitudinal research could assess whether the influence of emotional and cognitive triggers persists over time or diminishes as consumers’ exposure to short-form video content evolves. Finally, subsequent studies could explore privacy, security, and trust concerns in social commerce environments, responding to growing societal attention to responsible and ethical digital engagement.

8. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that cognitive appraisals (perceived usefulness), motivational triggers (curiosity), and affective drivers (benign envy) operate simultaneously to shape consumers’ attitudes toward short-form video content, which subsequently influences their intentions to visit destination retail stores. This multi-layered response underscores the persuasive power of visually dynamic, socially amplified media formats that blend information, emotion, and social validation.

Three key triggers, usefulness, curiosity, and aspirational envy, emerged as robust predictors of favorable attitudes, with envy exerting the strongest effect. Social influence further amplified these pathways, revealing that peer approval, influencer credibility, and user-generated content play pivotal roles in motivating consumers to translate digital exposure into physical action. Notably, perceived behavioral control did not significantly predict visit intention, suggesting that emotional and social forces may overshadow logistical considerations in hedonic or experiential retail contexts.

This research contributes to understanding how short-form video platforms shape hybrid consumer journeys, demonstrating that digital persuasion extends beyond product awareness to influence real-world behavior. The study bridges theoretical and managerial relevance by illustrating how new media formats reshape not only communication strategies but the broader architecture of consumer engagement in omnichannel retail. As video-based platforms continue to evolve, their role in driving digital-to-physical commerce will remain a critical area for both scholars and practitioners. By situating short-form video within the framework of interactive marketing, this study offers a refined perspective on the mechanisms through which consumers are inspired, motivated, and socially encouraged to engage with destination retailers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S. and H.L.; methodology, K.S. and H.L.; investigation, K.S. and H.L.; resources, K.S. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and H.L.; visualization, K.S.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Texas (protocol code: 23-208; approval date: 22 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (Version 5.1) in order to improve language and readability, as well as checking the correctness of references. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y. A social media engagement framework for destination marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design 4 Retail. New Format Retail: New and Increasingly Popular Retail Formats We Should Expect in 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.design4retail.co.uk (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Kernjak, A. Experience and Tech: The Rise of the Destination Store. Brand Experts, 8 July 2021. Available online: https://www.brand-experts.com (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, L.; Hu, M. Social media, consumer behavior, and brand loyalty: A study of influencers and followers. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.; Eynon, R. Digital Natives: Where Is the Evidence? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergroach, S. Innovation and the digital-native model. In OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Kim, T.; Won, D. Exploring the influence of social media on consumer decision-making in the tourism context. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Anadol, E.; Farnsworth, T.; Hugo, H.; Hunichen, J.; Welte, D. Navigating the new era of influencer marketing: How to be successful on Instagram, TikTok & Co. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 63, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Like, Comment, and Share on TikTok: Exploring the Effect of Sentiment and Second-Person View on User Engagement with TikTok News Videos. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2024, 42, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manic, M. Short-Form Video Content and Consumer Engagement in Digital Landscapes. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov Ser. V Econ. Sci. 2024, 17, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. How social media influencers affect behavioral intentions towards recommended brands: The role of emotional attachment and information value. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 1123–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Phongsatha, T. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention through TikTok of Changsha, China residents. AUE J. Interdiscip. Res. 2022, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, L.B.; Septiarini, E.; Satriawan, D.A.A.; Aas, R.E. Consumer attitude toward purchase intention of culinary products through video-based social media: A deductive exploratory study in Bandung City. Asian J. Technol. Manag. 2023, 16, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Inspiration and Persuasion in Online Travel Media: A Model of Destination Choice. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 477–492. [Google Scholar]

- Bargoni, A.; Conti, E.; Aiello, G. Digital Place-Making and the Role of Emotional Anticipation in Retail Destination Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y. Shopping as Leisure: The Role of Social Media and Self-Presentation in Retail Tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100732. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G. The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, J.A. Relationships between measures of I- and D-type curiosity, ambiguity tolerance, and need for closure: An initial test of the wanting-liking model of information-seeking. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. Silver lining of envy on social media? The relationships between post content, envy type, and purchase intentions. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 1142–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, L.; Li, X. Social media envy: How experience sharing on social networking sites drives millennials’ aspirational tourism consumption. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.S. The Impact of Barrage System Fluctuation on User Interaction in Digital Video Platforms: A Perspective from Signaling Theory and Social Impact Theory. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.C.; Chan, F.F.Y. Strategies to Drive Interactivity and Digital Engagement: A Practitioners’ Perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 901–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.-T.; Mai, N.Q.; Nguyen, L.T.; Thuan, N.H.; Dang-Pham, D.; Hoang, A.-P. Examining Authenticity on Digital Touchpoint: A Thematic and Bibliometric Review of 15 Years’ Literature. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; De Backer, C.J.S. Social Media Influencers and the Shaping of Consumer Emotions: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.Y.; Lu, H.P. Integrating the Technology Acceptance Model to Explore the Influence of Short-Form Video Content on Online Purchase Intention. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 51, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, J.A. Interest and Deprivation Factors of Epistemic Curiosity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrath, M.H.E.; Biraglia, A. The Role of Curiosity in Experiential Consumption: Evidence from Digital Media and Retail Contexts. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, C. Envy on Social Media: How Benign and Malicious Envy Influence Travel Intention and Consumption Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasetti, A.; Singer, P.; Troisi, O.; Maione, G. Extended theory of planned behavior (ETPB): Investigating customers’ perception of restaurants’ sustainability by testing a structural equation model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, T.; Shi, G.; Jiang, L. I want to go there too! Tourism destination envy in social media marketing. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajli, N.; Wang, Y.; Tajvidi, M. Travel envy on social networking sites. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. “I’ll buy what she’s #wearing”: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovic, A. If You Have It, I Want It… Now! The Effect of Envy and Construal Level on Increased Purchase Intentions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rose, P.; Fincham, F.D. Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. J. Pers. Assess. 2004, 82, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manis, K.T.; Choi, D. The virtual reality hardware acceptance model (VR-HAM): Extending and individuating the technology acceptance model (TAM) for virtual reality hardware. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülbül, C.; Menon, G. The power of emotional appeals in advertising: The influence of concrete versus abstract affect on time-dependent decisions. J. Advert. Res. 2010, 50, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Sarkar, A. “To feel a place of heaven”: Examining the role of sensory reference cues and capacity for imagination in destination marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33 (Suppl. S1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hu, C.; Wu, C.M.E. Affect, travel motivation, and travel intention: A senior market. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A. The effects of personal values on travel motivation and behavioral intention. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, S.M.; Yun, D.; MacDonald, R.; MacEachern, M. The effects of advertising awareness and media form on travel intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rico, M.; Molina-Collado, A.; Santos-Vijande, M.L.; Molina-Collado, M.V.; Imhoff, B. The role of novel instruments of brand communication and brand image in building consumers’ brand preference and intention to visit wineries. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12711–12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ali, F.; Waheed, A.; Nawaz, S. You plant a virtual tree, we’ll plant a real tree: Understanding users’ adoption of the Ant Forest mobile gaming application from a behavioral reasoning theory perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Rasool, S.F.; Yang, J.; Asghar, M.Z. Exploring the relationship between despotic leadership and job satisfaction: The role of self-efficacy and leader–member exchange. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.; Seok, H.; Nam, Y. The moderating effect of social media use on sustainable rural tourism: A theory of planned behavior model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. Service co-creation in social media: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwalda, A.; Lü, K.; Ali, M. Perceived derived attributes of online customer reviews. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L. Challenging the myth of the digital native: A narrative review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajli, N.; Wang, Y. Social Media Use and Consumer Behavior: The Role of Digital Influence. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Social Media Video Habits of Gen Z and Millennials; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Pew Research Center. Social Media Use in 2023; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. In Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Barnes, S.; Le-Nguyen, K. Consumer acceptance IT products: An integrative expectation-confirmation model. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First Americas Conference on Information Systems, Fajardo, Puerto Rico, 13–15 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, S.; Alvarez, C. Brands as relationship partners: Warmth, competence, and in-between. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivens, B.S.; Leischnig, A.; Muller, B.; Valta, K. On the role of brand stereotypes in shaping consumer response toward brands: An empirical examination of direct and mediating effects of warmth and competence. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Karahanna, E. Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Hyun, S.Y.; MacInnis, J.D. Choosing what I want versus rejecting what I don’t want: An application of decision framing to product option choice decision. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Baker, J. Excitement at the mall: Determinants and effects on shopping response. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; De Grave, W.; Ganjiwale, J.; Muijtjens, A.; van der Vleuten, C. Paying attention to intention to transfer faculty development using the theory of planned behavior. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Xiang, J. Reality TV, audience travel intentions, and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial: Demonstrating Contributions through Storytelling. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; Fisher, T. Gender Differences in Emotional Responses to Social Media Content. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).