Abstract

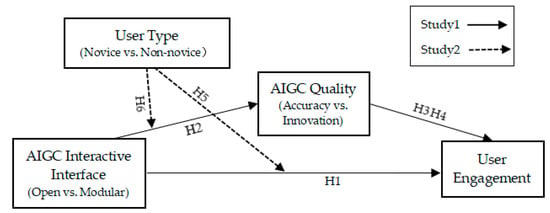

How human–AI interactive interfaces affect user engagement with AIGC platforms is a critical underexplored issue. Grounded in signaling theory, this paper constructs a theoretical model to examine the differential effects of two interactive interfaces—modular versus open—on user platform engagement, the mediating role of AIGC quality, and the moderating role of user type. Through two scenario experiments, our findings reveal that both AI interactive interfaces (open and modular) significantly enhance user platform engagement, with the open interface exhibiting a stronger effect. Specifically, AIGC accuracy serves as a mediator in the relationship between modular interfaces and user engagement, and innovativeness plays a mediating role in the relationship between the open interface and users’ engagement. Furthermore, novice users strengthen the effect of open AIGC interfaces on AIGC innovation and subsequent engagement, Non-novice users amplify the positive impact of modular AIGC interfaces on both AIGC accuracy; however, there is no significant difference for user engagement. These findings theoretically enrich the customer response model in the literature on human–computer interactions and provide actionable insights for AIGC platform enterprises. By designing tailored interactive interfaces, platforms can generate high-quality, user-perceived AIGC for diverse customer segments. This study offers both theoretical contributions and practical implications for the development of AI-driven user engagement strategies.

1. Introduction

The development of generative AI empowers thousands of industries. A variety of AI-generated content (AIGC) platforms have emerged, such as GPT-4 and Claude for content generation, DALL-E3 and Midjourney for image generation, and Sora for video generation []. These content generation platforms enable customized services through the use of deep mining and can meet user needs []. The core idea is to use AI to realize high-quality interactions with users, obtain accurate information about user needs, and thus improve the efficiency of content customization [,]. The AI–user interactive interface plays an important role in improving the quality of this interaction. It should offer natural interaction with users by understanding users’ behavior, voice, and even mood. For example, AIGC platforms provide different interface modes (such as prompt words and module click options) to achieve a personalized experience []. However, few academic studies focus on the relationship between the AI interactive interface and subsequent customer behavioral response.

Although some studies have begun examining AIGC interactive interfaces, exploring attributes and design principles [], the literature remains dominated by discussions of interface strategies grounded in traditional web platforms and technologies. Such approaches fail to capture the unique characteristics of AIGC contexts, rendering existing interface strategies inadequate for meeting users’ personalized needs or fostering customer engagement [,,]. Consequently, critical research gaps persist regarding the conceptualization of AIGC interactive interfaces, their strategic classification, and their underlying mechanisms for driving customer engagement. Unlike conventional technology-centric perspectives, AIGC interfaces primarily rely on design to convey quality signals to users, mitigating information asymmetry and thereby enhancing engagement [].

Customer engagement refers to a customer’s behavioral manifestations toward AI platforms beyond purchase, driven by underlying motivational factors []. Previous studies have examined many factors influencing users’ platform engagement, such as ease of use, usability, brand, and technology. The quality of content generated by platforms is undoubtedly the most important and critical factor, as it can meet the core needs of users: identifying moral hazards and reducing the cost of selection []. Therefore, a more in-depth discussion of these two aspects of the content quality is crucial for understanding how to influencing the platform–user interface to improve user engagement. Furthermore, the moderating effect of individual characteristics (e.g., proficiency level) on the difference in users’ acceptance of interface types cannot be ignored. Previous studies have found that the level of user knowledge has a profound impact on users’ cognition and judgment of various strategic behaviors on the platform and the behavior of technological adoption [,,], but few studies focus on the boundary mechanism of user type in AI interactive interfaces. To fill this research gap, this study addresses two fundamental research questions:

- How do AIGC interactive interfaces foster user–platform engagement?

- What mediating role does AIGC quality play, and how do user types moderate these relationships?

In summary, the innovative points of this study are threefold: (1) It conceptualizes and classifies the interface of AI-generated content (AIGC) within the context of generative AI, and studies its impact on user engagement, enriching the literature on user interfaces. (2) It conceptualizes different interface types as quality signals to alleviate the information asymmetry problem in the user quality assessment, expanding the application of signal theory in AIGC research. (3) Based on the perspective of AIGC quality, it reveals the mechanism of interactive interfaces and examines the constructs and dimensional structure of AIGC quality, deepening the understanding of the model mechanism.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Signaling Theory

Signaling theory suggests that, during information transmission, individuals will utilize information differently due to differences in information processing methods and comprehension abilities, resulting in information asymmetry. The theory aims to fundamentally reduce information asymmetry between the two parties []. Signaling theory consists of three key elements—the signal sender, the signal receiver, and the signal itself []. The signal sender has access to information about individuals, products (or services), and organizations that is not available to receivers []. In order to transmit effective signals, the signal sender should know some behavioral intentions and personal characteristics of the receiver. In marketing research, users are treated as signal receivers [] and firms act as signal senders, releasing information (e.g., price, brand, promotions, ratings) to reduce users’ uncertainty about product/service quality. Users rely on these signals to assess quality and make informed decisions [].

Information asymmetry between users and the AIGC platform makes content quality difficult to assess, hindering user engagement [,]. Signaling theory holds that the AIGC interface serves as a quality signal, and its content and style convey the quality information of the product (or content) to the users. Only when users fully understand this information and successfully reduce the effort of generating user-generated content, can this information be regarded as an effective signal. Based on the above analysis, the human–AI interface with effective signals has become an urgent theoretical problem to be studied and solved to explore how to drive user engagement through AIGC quality. Moreover, the validity and fit of this model are greatly affected by user characteristics (such as proficiency level). Signaling theory has been widely applied in various fields, including economic management. This article introduces signaling theory into the context of AIGC interfaces and successfully aligns the research object with the key elements of the theory.

2.2. AIGC Interactive Interface and User Engagement

The artificial intelligence interface is defined as a graphical system that regulates the interaction between humans and the platform. It is characterized by adopting a user-centered design model and being able to dynamically adapt to users’ inquiries and requests [,]. The current research on AI interfaces is mainly conducted from a technical perspective based on different scenarios, e.g., interfaces in autonomous vehicles and intelligent learning communities [,]. In addition, relevant research summarizes common forms of AI interactive interfaces based on AI user experience practice [,,], and recent advances in large AI models have spurred growing scholarly interest in AIGC interfaces [,,,,]. This research differs from the traditional technology adoption model. Instead, it constructs a theoretical model based on the signal theory. Firstly, the theoretical core of the technology acceptance model is the acceptance and adoption of the AIGC platform by users (focusing on usability and availability) [], while the theoretical core of the signal theory is how the platform transmits information and how users interpret the unobservable quality signals [], by which our research explains the relationship between interactive interfaces and user engagement. Secondly, the technology acceptance model pays more attention to whether the platform interface is user-friendly, while the signal theory pays more attention to how to evaluate the quality of AIGC content [], which is the mediating content of our conceptual model. Based on the comparative analysis (See Table 1), we believe that the signal theory is more suitable for this research model, and it outperforms the technology acceptance model in predicting the quality of AIGC and user engagement.

Table 1.

Comparison of Signaling Theory and Technology Acceptance Model.

However, studies on interface classification remain limited. Nath and McKechnie (2016) [] classified the level of an interactive interface as high and low. They believed that a high-level interactive interface supports barrier-free communication between users and AI, while a low-level interface allows users to customize the interface content by providing options. However, this simple classification does not effectively reflect the interaction characteristics in the AIGC scenario. Ghosh, Dutta, and Stremersch (2006) [] used “custom control” to indicate the degree of vendor control over the components of a custom product, where a high level of custom control means that venders design modular products according to customer requirements, which means low-level customer control. Conversely, a low level of custom control for vendors means that the customer mainly analyzes their own needs (open) in detail and translates them into a specific solution, which means a high level of customer control. This study states that AIGC is essentially customer-customized content, so the AIGC interactive interface is creatively divided into a modular interface and an open interface by integrating the ideas of Nath and McKechnie (2016) [] and Ghosh et al. (2006) []. Based on Sanchez (1999) [] and Gremyr, Valtakoski, and Witell (2019) [], this paper considers a modular interactive interface to mean that the AIGC interactive interface generates different standardized modules according to user requirements, and users can select and combine these standardized modules to put forward their own content customization requirements. Because it focuses on the realization of preset functions, although it reduces the complexity of user operation to a certain extent, it also limits the user’s willingness to take the initiative in participation. To a certain extent, a modular AIGC interface increases the “signal cost” paid by users as signal receivers. Regarding “openness”, the open AI interactive interface can be freely extended and customized and has very low restrictions on the user, allowing the user to provide unstructured data and prompts. Han, Yin, and Zhang (2022) [] believe the openness of AI can help the platform better identify human emotions and deeply understand the implicit needs hidden in user expression. The higher the degree of AI openness, the higher the proportion of user participation []. The study of Bagozzi et al. (2022) [] found that when providing more private and sensitive information, compared with standardized information collection methods, users were more inclined to confide their feelings to open AI [].

As mentioned above, the AIGC platform needs to send “signals” to help users eliminate information asymmetry. On the one hand, from the perspective of users, the AIGC interactive interface can simplify the content generation process, provide accurate services and promote user participation. On the other hand, an effective AI interactive interface becomes an important basis for the platform’s ability to accurately judge user needs []. Therefore, the AIGC interactive interface can promote user platform engagement. However, the modular interactive interface has a higher cost in terms of signals, and its experience is not as superior as that of the open interface [,]. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The positive impact of an open AIGC interface on user engagement is higher than that of a modular AIGC interface.

2.3. The Mediating Role of AIGC Quality

User-generated content on social media is an important source of information for enterprises to customize services for their users [,]. In the AI context, based on Huang and Rust (2018) et al. [,,], this study defines AIGC quality as the quality of content generated by AI based on enterprise user databases or user requirements. When evaluating the quality of artificial intelligence-generated images, researchers have determined a general framework for AIGC quality assessment consisting of four key dimensions []. Lee et al. (2018) [] found that users prioritize “informational” content for its authenticity and accuracy, and value “persuasive” content for its creative expression. Therefore, this study focuses specifically on two core dimensions of AIGC quality: accuracy and innovation. Accuracy refers to the fact that AI robots can accept daily service requests and complete a series of functional behaviors based on historical data, catering to the cognitive processes of users and providing an accurate service experience [,]; innovation refers to the degree to which the results generated by AI are flexible and innovative [], the above definitions indicate that accuracy provides the need to obtain basic user information, while innovation can provide content that exceeds customer expectations. The two are distinct yet complementary to each other.

AI interfaces suggest that AI relies on structured data provided by users to obtain user preferences and needs through machine learning technology, which can effectively improve the accuracy of content generation services [,,]. The modular interactive interface contains a library of common modules that users can use to speed up the development process, ensuring that manufacturers can easily communicate with users, as well as transfer and copy custom designed content without additional conversion costs, improving the accuracy of generated content. Thus, it becomes a signal of the “accuracy” of the platform. Kim and Slotegraaf (2016) [] found that open information interaction is conducive to user creativity and user participation. Creating a “dialog” between businesses and users can greatly improve customization innovation []. The open AI interface allows users to provide unstructured requests. Han et al. (2022) [] showed that AI can analyze user semantics, better identify user emotions from words, and deeply understand the needs hidden in user emotions and expressions. These AI analysis results come from the user’s own ideas, which will provide new ideas for AIGC, thus increasing the possibility of product innovation, so that the open interactive interface of the platform becomes a signal of “innovation”. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

A modular AI interactive interface is conducive to AIGC accuracy, and an open AI interactive interface is conducive to AIGC innovation.

In the era of AI, major platforms attach great importance to the accuracy of content delivered by AI to gain the support of users [,]. Chang (2022) [] believes that when AI robots on social media platforms answer user questions, if the answer accuracy is low, user satisfaction will decline. Shen’s (2014) [] research shows that AI agents can “learn” user preferences and make personalized recommendations for products and services based on big data, and the precision of this has a positive effect on user loyalty. Lim, Donkers, van Dijl, and Dellaert (2021) [] found that when an AI advisory system provides investment advice to users, whether or not the AI-generated investment plan fits accurately with users’ risk preferences will affect users’ trust. Kim et al. (2022) [] pointed out that AI customization can effectively improve the user experience, and customized products can accurately meet user expectations, thus enhancing user stickiness and loyalty. In short, AIGC presentation quality, as a “signal” that can be observed by users, is crucial to user evaluation, such as user loyalty and satisfaction. Therefore, AIGC accuracy can help generate users’ psychological and behavioral engagement. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

The accuracy of AIGC has a positive effect on user engagement.

Based on the theory of emotional arousal, Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012) [] argued that innovative content can trigger higher emotional arousal in users, making it more likely to be forwarded and shared, and making users more willing to support it. Pallant, Sands, and Karpen (2020) [] argue that the essence of customization is product innovation, and AIGC is a new form of customization based on artificial intelligence technology. Hung, Chou, and Dong (2011) [] emphasize that online innovation includes new practices that enhance users’ online effectiveness, importance, interactivity, novelty, personalization, and esthetics. Moreover, research has found that more innovative digital content is more attractive to users. Studies have found that AI-based innovation can better attract and retain users and enhance user satisfaction and loyalty [,]. Studies have shown that, in some innovative industries, AI-based design works tend to generate greater attention and response and form a greater impression on users [,]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

The innovation of AIGC has a positive effect on user engagement.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of User Type

Schreier and Prugl (2008) [] and Wang, He, and Zhu (2010) [] argued that user experience and knowledge influence the consumption and innovation behaviors of enterprises and users. They classified users into ordinary users and expert users based on their knowledge. This study classified AIGC users into two types: novice and non-novice. Novices are users who have relatively little experience, knowledge of related operations, and understanding of AIGC. Non-novices, on the other hand, are users who have more experience and operational knowledge.

Signaling theory states that the signal sender should know some of the behavioral intentions and personal characteristics of the receiver in order to transmit effective signals []. Because non-novice users have a higher usage rate and product knowledge is more abundant, they can better understand the relationship between product structures [,,]. Therefore, non-novice users are more sensitive to the selection and combination effects of product attributes provided in the modular AIGC interface and prefer the reorganization of existing information and knowledge, and make more efficient use of modular design methods for content or product design due to their rich experience. Moreover, due to the higher understanding and usage ability of non-expert users, the perception cost of the two interface signals will be negligible due to the stronger preference. In summary, compared to the open interface, choosing a modular AIGC interface with more prominent properties may be more in line with the preferences of non-novice users.

For novice users, they tend to propose unstructured content customization needs. Moreover, AI-initiated content generation tasks will meet more resistance from users than work led by users themselves []. This is because the average user’s level of knowledge related to content or products is relatively low [], and when faced with a modular AIGC interface, they do not fully understand the modular options provided by the interface, which leads to a high signal perception cost. The open AIGC interactive interface provides users with a free creation window, and novice users can boldly propose their own content generation ideas based on the guided prompts given by the interface. Therefore, the open AIGC interface reduces the complexity and cost of the perceived signals for novice users and simplifies the content generation process, which is conducive to the psychological attachment of novice users to the open AIGC interface and the willingness to reuse it []. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

Non-novice users enhance the effect of a modular AIGC interface on engagement; novice users enhance the effect of an open AIGC interface on engagement.

Dewan, Jing, and Seidmann’s (2000) [] shows that product-by-attribute customization can encourage users to think more carefully about product details. Similarly, when generating content using a modular AIGC interface, users select key product attributes according to their own needs within each module, which is a process of user self-reference and mental simulation []. The modular approach makes it easier to manage and control the quality and performance of a product by breaking it down into multiple independent modules []. Non-novice users can choose the right modules according to their own experience, make preliminary settings for the content to be generated in advance, and ensure their quality and performance, thereby improving the quality accuracy of the content. Open AIGC interfaces transfer more creative power to users, allowing them to fully express themselves, which is exactly what the novice user needs. Alba and Hutchinson (1987) [] show that novice users tend to be more receptive to new product information, and they are also highly active in broader information processing and innovative behaviors. Previous studies have shown that open access to information is more likely to stimulate user participation and facilitate the generation of new products. The information provided by novice users in the open AI customization interface is unstructured and does not adhere to traditional product attributes, increasing the possibility of diversity in AIGC. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Non-novice users enhance the effect of modular AIGC interfaces on the accuracy of AIGC; novice users enhance the effect of open AIGC interfaces on innovative for AIGC.

In conclusion, this paper proposes a conceptual model for the influence of AIGC interactive interfaces on user engagement, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Study 1: The Main Effect of the AIGC Interface on User Engagement

Study 1 aims to verify the main effect of the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) on user engagement (H1) and the mediating effect of AIGC quality (H2, H3, and H4).

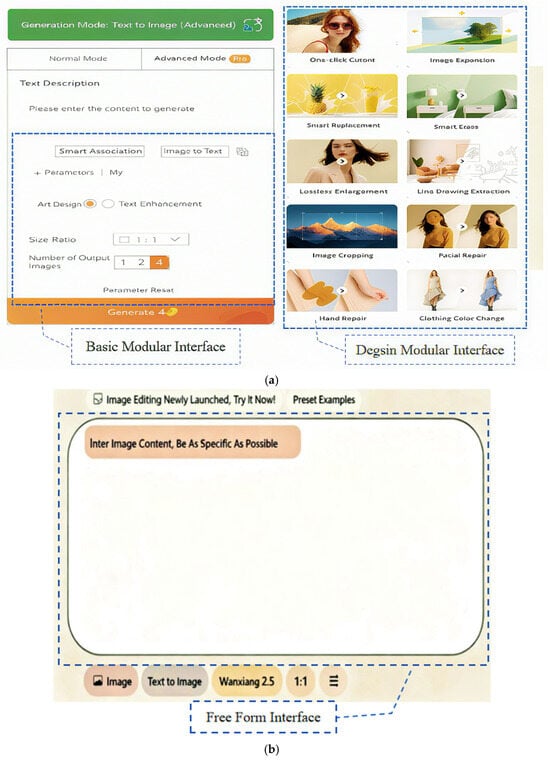

3.1. Stimuli

We need to ensure the differentiation of open and modular AIGC interactive interfaces. Because AI painting can deliver the AIGC directly to the subject in a short time, the experiments in this study were all designed on an AIGC painting platform. In the pre-experiment stage, we invited subjects to enter the AIGC interface and collected their feedback on the interface using questionnaires.

We chose the Chinese mainstream AIGC painting platforms Tongyi Wanxiang and Lingtu. They are easy to log in to and register for and free to use. These two platforms possess the typical characteristics of modularity and openness, and thus have a relatively high degree of representativeness. Tongyi Wanxiang has an open interface, providing input boxes in which the user can customize the content elements and style requirements of the work by describing them in text. Lingtu has a modular interface, which supports the following functional characteristics: select, paint, generate image operations, process and repair images, add pictures and text, and modify the attributes of pictures and text. (Figure 2a,b).

Figure 2.

(a) A modular interface (Lingtu). Note: From Lingtu by China Xiamen Lingtu Technology Co., Ltd. https://www.lingvisions.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2025). Copyright by Lingtu Technology Co., Ltd. (b) An open interface (Tongyi Wanxiang). Note: From China Hangzhou Tongyi Wanxiang by Aliyun. https://tongyi.aliyun.com/wan/generate/image/text-to-image?model=wan2.5 (accessed on 10 October 2025). Copyright by Aliyun.

A total of 48 subjects were recruited in the pretest and divided into two groups randomly. We sent platform links to the two groups; they clicked the link to access the AIGC interface and were randomly assigned to one of two interfaces (modular interface vs. open interface).

When the participants logged on to the website for the first time, they were required to enter their mobile phone number and to obtain a verification code for registration (about 15 s). After registration, they were able to access the AIGC interface. After that, the participants completed the questionnaires based on their own opinions of the AIGC interface. The questions asked the participants to what extent they distinguished different AI interactive interfaces and to measure their satisfaction with the interface. The specific questions were as follows: (1) Does the interface meet the previous description of the modular interface? (2) Does the interface meet the previous description of an open interface? Using the Likert 7-level scale, 1 = very inconsistent, 7 = very consistent. (3) what is your satisfaction with the interface? Using the Likert 7-level scale, 1 = very dissatisfied, 7 = very satisfied. A variance homogeneity test was then carried out to check whether the experimental operations met the manipulation requirements.

One-way ANOVA was used to test the manipulation validation of the AIGC interactive interface. The homogeneity test of variance showed that p = 0.209 > 0.05, and ANOVA could be performed. The results of the manipulation test showed that there were significant differences between the two experimental groups of users of the modular and open interfaces (F (1,47) = 7.538, p < 0.001; Mmodular = 5.62, SD = 1.135; Mopen = 4.58, SD = 1.472), indicating AIGC interface (modular vs. open) manipulation success. There was no significant difference between the two groups (Mmodular = 4.79, Mopen = 5.21, p = 0.302 > 0.1) in their satisfaction ratings for the two interfaces. These tests confirmed the experimental design.

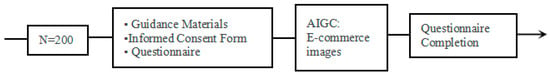

3.2. Experimental Design and Process

A single-factor 2-level (AIGC interface: modular vs. open) intergroup design was adopted. To ensure that the participants could complete the content generation process independently, the formal experiment was conducted through the Credamo online platform. Each participant who passed the screening stage was paid CNY 14 after completing the formal experiment and submitting the generated work. A total of 200 subjects were recruited, comprising 99 males (49.5%) and 10 females (50.5%) with an average age of 32 years. The majority had a bachelor’s degree or higher (86.57%), and they were mostly employees of enterprises (74.63%). In line with the characteristics of the AIGC user group, the internal and external validity of the experimental results and the universality of the research conclusions were ensured.

The detailed process is illustrated in Figure 3. The participants were restricted to completing the experiment on the PC, independently reading the text materials, designing the AI content, and completing the questionnaire survey. After reading and signing an informed consent form, the subjects were randomly assigned to two condition groups. At the beginning of the experiment, the participants first read the following “Welcome…” instructions on a PC-independent interface (displayed using PowerPoint): “Later you will see an introduction of a pastry company, please imagine yourself as a designer for the e-commerce promotion images of the company”. Image design was selected as the experimental task because the image name, color, font, and design can be presented on both modular and open interfaces []. After the introduction, the participants were asked to read a paragraph containing information about a company, including its business area, representative products/services, and company culture (shown in Appendix A). The company was fictitious to avoid brand associations.

Figure 3.

Procedure of Experiment 1.

The two groups then read an introduction to the function of the relevant interface and instructions for its operation. The modular AIGC interactive interface introduction read, “There are options in the AIGC interface, such as selection, painting mode, style and size, etc. After completing the selection of options, click ‘generate content’, and wait about 10–15 s to complete the generated work.” The open AIGC interactive interface introduction read, “You can enter your own ideas in the input box of the AI customized interface, enter the requirements, click ‘generate content’, and wait about 10–15 s to complete the generated work.” The task instructions were formulated as follows: “Please use the AI painting platform to design, and the time is limited to 30 min.” After understanding the task, the subjects began to use the AIGC interface. After 30 min, the task was finished, and the subjects were asked to complete the user engagement and AIGC quality scales and provide their demographic information.

The variables measured in Study 1 included AIGC accuracy (α = 0.839), innovation (α = 0.879), and user engagement (α = 0.957), the reliability values (CR) and AVE values of the variables are both satisfactory. The measurements of two variables were referenced from previous studies [,,]. A 7-level Likert scale was used, where 1 means completely disagree and 7 means completely agree. The measurement items were revised according to the AIGC scenario, and the above results are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A.

3.3. Experimental Results

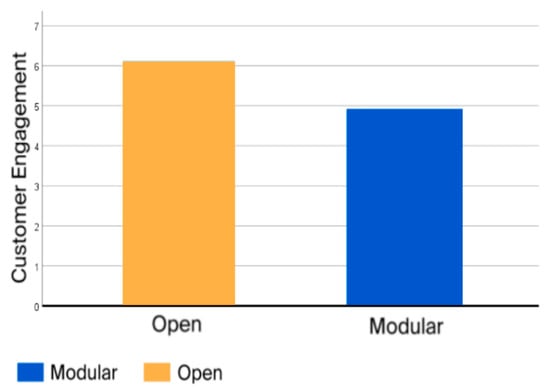

The effects of the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) on user engagement were examined. An independent sample t-test was conducted, with the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) as the factor and user engagement as the dependent variable. The analysis results show that there are significant differences in user engagement between the two AIGC interactive interface modes (Mmodular = 4.903, Dmodular = 0.933; Mopen = 6.117, Dopen = 0.730, F = 104.824, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.346), indicating that the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) has a significant impact on user engagement, and user engagement under the open AIGC interactive interface is higher than that under the modular AIGC interactive interface (Figure 4). Therefore, hypothesis H1 is true.

Figure 4.

The impact of AIGC interface on user engagement.

The effects of the AIGC interactive interface on AIGC quality were tested. An independent sample T-test was conducted, with the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) as the factor and AIGC quality as the dependent variable. The results showed the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) has a significant impact on the accuracy of AIGC (Mmodular = 6.623, Dmodular = 0.602; Mopen = 3.76, Dopen = 1.17, F(1198) = 334.905, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.4628), and the accuracy of AIGC in the modular AIGC interactive interface is higher than that in the open AIGC interactive interface. Similarly, the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) has a significant impact on the innovation of AIGC (M modular = 3.348, Dmodular = 0.971; Mopen = 5.213, Dopen = 0.985, F(1198) = 181.8, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.479), and the innovation of AIGC in the open AIGC interactive interface is higher than that in the modular AIGC interactive interface. Thus, H2 is true.

The impact of AIGC quality on user engagement was examined. User engagement was taken as the dependent variable and AIGC quality as the independent variable, which was included in the regression equation, and decentralized processing was carried out for each variable before testing. With AIGC accuracy as a factor and user engagement as a dependent variable, univariate analysis of the general linear model shows that AIGC accuracy has a significant impact on user engagement (F = 6.541, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypothesis H3 is valid. Taking AIGC innovation as a factor and user engagement as a dependent variable, univariate analysis of the general linear model shows that AIGC innovation had no significant effect on user engagement (F = 9.342, p < 0.01). Thus, hypothesis H4 is valid.

To further verify the mediating effect of AIGC quality, a mediation mechanism analysis was conducted using Model 4 in the Process plugin. The sample size was 5000, with a 95% confidence interval. The independent variables were the AIGC interface type (open = 1, modular = 2), the mediating variables were AIGC innovativeness and accuracy, and the dependent variable was customer engagement. The research results showed that AIGC innovativeness mediated the influence of the open interface on customer engagement (indirect effect: b = 0.7521, SE = 0.1539, 95% CI = [0.4608, 1.0521]; direct effect: b = 0.4613, SE = 0.1452, 95% CI = [0.175, 0.7476]). AIGC accuracy mediated the influence of the modular design on customer engagement (indirect effect: b = 1.2903, SE = 0.1851, 95% CI = [0.8908, 1.6175]; direct effect: b = −2.5036, SE = 0.1567, 95% CI = [−2.8126, −2.1947]). This once again verified the mediating effect of AIGC quality.

4. Study 2: The Moderating Effect of User Type

There were two main objectives of Experiment 2: The first was to examine the impact of the interaction between the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) and user type (novice vs. non-novice) on user engagement and the impact of interaction between the AIGC interactive interface and user type on AIGC quality. The second was to manipulate user types (novice and non-novice) in a way that trains users, so as to verify H5 and H6.

4.1. Experimental Design and Process

Study 2 adopted a 2 (AIGC interface: modular vs. open) ×2 (user type: novice vs. non-novice) intergroup design. Participant recruitment was similar to that in Study 1 and conducted online via Credamo. A total of 182 subjects were recruited in Study 2, and the average age of the participants was 29 years. The majority had a bachelor’s degree or higher (87.95%), and they were mostly employed (79.77%). The cohort included a total of 20 students (10.9%).

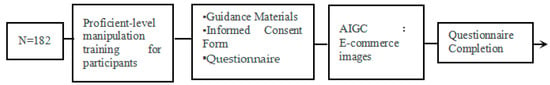

The detailed process is illustrated in Figure 5. Before the experiment began, the experiment order and precautions were explained to the subjects. The subjects read and signed an informed consent form before starting the formal experiment. At the beginning of experiment 2, each user’s level of AIGC proficiency was controlled by training them using an AIGC platform knowledge introduction and operation guide. Both the non-novice and novice groups were asked to read a text of about 1700 words. The non-novice group read about the AIGC user guide (both theoretical and operational information), while the novice group read material unrelated to the AIGC platform, including a travel guide for a certain city. The users’ AIGC proficiency level was improved by training them in AIGC theory and practical operation, while reading the travel guide could not improve the users’ AIGC knowledge level. To verify the effectiveness of the control method, 40 subjects (20 each) were invited for training before the formal experiment, and they answered 10 AIGC-related questions after reading the material. The results showed that the number of questions answered correctly by the AIGC user training group (M = 8.85) was significantly higher than that of subjects who read the travel guide materials (M = 5.05; p < 0.001). Therefore, the experimental material can effectively manipulate users’ proficiency level. Then, similar to the procedure of Study 1, the subjects were told “Please unleash your imagination and create an eye-catching new Chinese-style pastry design for this vibrant and innovative company! We look forward to your work! Please click the link to start creating”. The AI-generated images of new Chinese-style pastries, being closer to the subjects’ everyday dietary perceptions and aesthetic experiences, enabled the subjects to establish stronger cognitive associations with them, providing clear references for them to perceive image quality.

Figure 5.

Procedure of experiment 2.

The subjects clicked the link on the PC interface to enter the AIGC interface and were randomly assigned to four groups: modular–novice group, modular–non-novice group, open–novice group, and open–non-novice group. To introduce the interface functions to the subjects in the modular AIGC interface group, the following text was used: “In the AIGC interface You can choose to generate images by selecting the model, painting mode, style, size, and other options, as well as use features like image expansion, image upscaling, smudge removal and editing, intelligent cutout, and image overlay. Once the selection is complete, click ‘Generate Content’ and wait about 10–15 s for the generated game to appear.” For the open AIGC interface group, the text read, “The AIGC interface provides an input box in which you can write a text description of the content elements and style requirements of the work, or you can upload a photo of your real image. Then click ‘Generate Content’ and wait about 10–15 s for the generated game to appear.”

After the creation process, the subjects were also asked to fill out questionnaires addressing user engagement, AIGC quality, user type, and demographic information, according to the generated works. The measurement of user type (α = 0.933) refers to the research of Lee (2016) []. The variables measured in Study 1 included AIGC accuracy (α = 0.963), innovation (α = 0.905), user engagement (α = 0.967), and the measurement model showed acceptable reliability (CR) and convergent validity (AVE), and the overall model fit was good. Furthermore, the correlation and discriminant validity results were satisfactory. In Study 2, the English scale was translated back to obtain the Chinese scale, which was revised according to the AIGC scenario. The results of this study are shown in Appendix A Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3.

4.2. Experimental Results

The effects of gender, education, and age on AIGC quality and user engagement were first excluded (p > 0.05), and the main effect and intermediate effect were examined again before examining the moderating effect. First, the impact of the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) on user engagement was examined. An independent sample t-test was conducted with the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) as the factor and user engagement as the dependent variable. The results of the analysis show that the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) has a significant impact on user engagement, and the user engagement generated by the open AIGC interactive interface is higher than that generated by the modular AIGC interactive interface (Mmodular = 4.454, Mopen = 4.896, F(1180) = 6.685, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.036). Once again, this confirms the relationship between AIGC interactive interface and user engagement, proving Hypothesis H1.

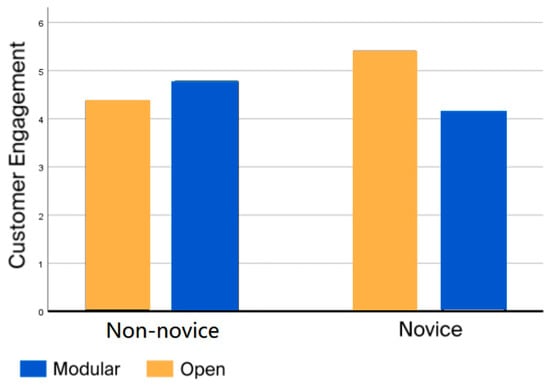

One-way ANOVA showed that among novice users, the user engagement of the open AIGC interactive interface group was significantly higher than that of the modular AIGC interactive interface group (Mmodular = 4.14, Mopen = 5.41; F (1,92) = 32.032, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.262). Among non-novice users group, there was no significant difference in user engagement between the modular AIGC interface group and the open interface group. (Mmodular = 4.77, Mopen = 4.37; F (1,90) = 3.017, p = 0.086, η2 = 0.033). Thus, we conclude that H5 has received support for novice users. For non-novice users, although the experimental results were not significant (p = 0.086), the mean value of the modular interface (4.77) is higher than that of the open interface (4.37), which means the trend is consistent with the original hypothesis. The above conclusions are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The impact of moderation on user engagement.

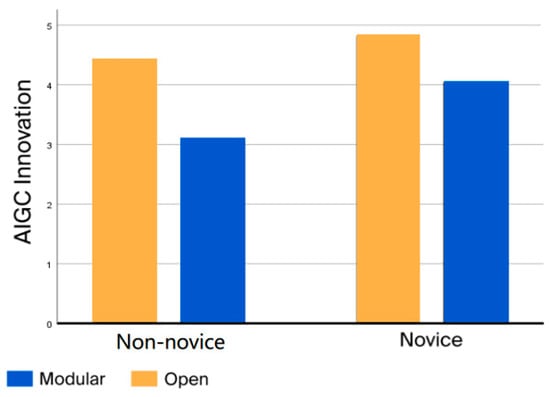

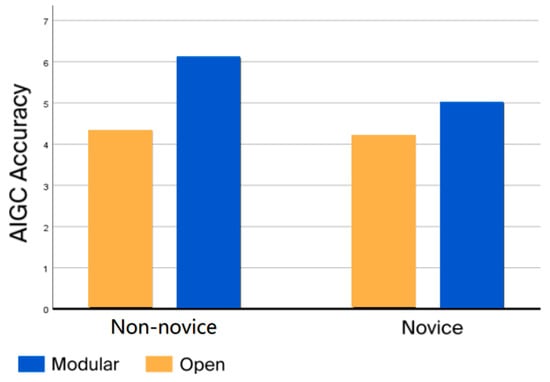

AIGC quality was set as the dependent variable in one-way ANOVA. The results showed, among the novice users, the AIGC innovation of the open AIGC interface group was significantly higher than that of the modular AIGC interface group (M modular = 4.04, M open = 4.82; F (1,92) = 20.995, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.189). These results are depicted in Figure 7. In the non-novice user group, the AIGC accuracy of the modular AIGC interface group was significantly higher than that of the open AIGC interface group (M modular = 6.09, M open = 4.33; F (1,90) = 75.686, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.462). The above results can be visually seen in Figure 8; we conclude that H6 is true.

Figure 7.

The moderating effect of user type on the relationship between AI interactive interface and AIGC innovation.

Figure 8.

The moderating effect of user type on the relationship between AI interactive interface and AIGC.

5. Overall Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

This study examines how AIGC interface types influence user engagement and their underlying mechanisms. Through two experimental studies, we derive three key conclusions:

First of all, the research investigated how different AIGC interactive interfaces (modular versus open) affect user engagement, and empirical evidence showed that open interfaces generated higher user engagement than modular interfaces.

Secondly, examining the mediating role of AIGC quality, we concluded that AIGC innovation significantly mediated the impact of the open interface on user engagement, and AIGC accuracy significantly mediated the impact of the modular interface on user engagement.

Finally, the research suggests that the moderating effect of user type in the AIGC interface (modular vs. open) on AIGC quality was significant. The modular AI interactive interface enhances non-novice users’ mental simulation of the generated content by providing pre-selection items, which facilitates non-novice users’ perception of AIGC accuracy. The open AI interface does not require users to have experience or knowledge, and users can fully express their needs in the customization process, increasing the possibility of generating diversified content, which is conducive to the innovation of AIGC. But surprisingly, the influence of user types on the user engagement in the AIGC interface has a significant moderating effect only for novice users. For non-novice users, the results were not significant, the possible reason may due to the non-natural experiment, where users’ behavioral intentions and actual behaviors may differ.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Grounded in signaling theory, this research investigates how AI interfaces drive platform engagement in AIGC contexts, making three theoretical contributions:

First, this study defines the AIGC interaction interface based on signaling theory and innovatively classifies it into two types, open and modular, expanding our understanding of the interaction interface. Previous studies based on the technology acceptance model held that users evaluate and decide whether to adopt AI according to the relevant functions and attributes of the technology’s interface [,]. This study, however, argues that because AI concepts are opaque for users and difficult to explain, leading to information asymmetry on both sides, the platform needs to eliminate information asymmetry by transmitting signals that influence users. The AI interface is a “tangible” signal that helps users judge the quality of AIGC. An open interface conveys qualities of “freedom, equality, nature and smoothness” to users, inspiring them to view AI as a creative “partner”. The modular interface, on the other hand, provides users with opportunities to “select, combine and customize”, making them more likely to view AI as a professional and reliable “tool”.

Second, we conceptualize AIGC quality in two dimensions—accuracy and innovativeness—unpacking the “black box” of how interfaces foster engagement. Existing frameworks for evaluating AIGC quality emphasize technical or esthetic aspects []. By focusing on content-centric quality, this study posits that an “open” interface enables users to anticipate innovative content, making them willing to engage, while a “modular” interface conveys accuracy, thereby promoting user engagement. Through this study, we enhance theoretical clarity and highlight the value of credible, creativity-driven content in an era of abundant AI-generated material.

Third, we identify user type as a critical boundary condition bolstering the model’s generalizability. This research suggests that novice AIGC users, due to their relative inexperience in using AI, encounter more obstacles when interacting with the modular interface. They prefer the natural and smooth interaction of the open interface and are more likely to ask various questions, which is conducive to the generation of innovative content and makes them more willing to engage. On the other hand, non-novice users are proficient at using the various functions of the AI module and can operate it smoothly. This module ensures the accuracy and reliability of the generated content and enables the user to avoid risks, making them more willing to engage. In alignment with prior research [], open interfaces are better suited to novices because they elevate perceived innovativeness, whereas modular interfaces resonate with non-novices. This user–interface fit deepens our understanding of drivers of engagement in AI-mediated environments.

5.3. Managerial Implications

AI, as a new productivity tool, offers an increasingly important competitive advantage in the development of platforms by co-creating with humans and providing mixed services. However, determining how to attract users to participate in and engage in new cooperative relationships is an important challenge. Based on the model construction and analysis from the perspective of human–computer interaction, this study concludes that different interactive interface designs can improve user engagement. Compared to modular interactive interfaces, open interactive interfaces are more effective in promoting user engagement. Therefore, platforms should adopt more open interactive interfaces to optimize user engagement.

Second, this study defines the concept of content generation quality based on the AIGC, which is classified and evaluated based on two core characteristics: accuracy and innovation. It deeply and systematically investigates the mediating role of AIGC quality on the relationship between AIGC and user engagement. The conclusion is that AIGC quality is crucial for users to engage in AI customization, and the platform should prioritize content generation quality. When users are concerned about content innovation, the interactive interface should attach importance to open interface optimization, and when users are concerned about content accuracy, the platform should strengthen the modular interface strategy.

Finally, the platform should fully understand the needs and characteristics of different types of users. Novice users prefer self-expression when engaging in production tasks, while non-novice users are more inclined to refer to existing knowledge. In view of these differences, enterprises can design more personalized AIGC interfaces to meet the needs of different users. This can be accomplished by, for example, providing more space for novice users to play independently, allowing users more customization power, reducing constraints, and providing non-novice users with more references and tools to help them innovate better. Therefore, when designing AI interfaces, enterprises should fully consider the differences in user types and optimize interface design and interaction methods. This conclusion can be extended to a wider range of digital platform interfaces. Importantly, user types are not limited to novice and non-novice. Digital platforms can also consider the differentiated needs of users with varying demographic characteristics, behavioral habits, and motivations for using the platform. Interfaces can be designed to match these needs and convey appealing signals to users, obtaining their support and engagement.

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

Based on signaling theory, this study discusses the mechanism of the AIGC interactive interface (modular vs. open) driving user platform engagement, enriches the literature related to AIGC and human–computer interaction, and expands the theory of user engagement in the AIGC context. However, this research still has some limitations.

(1) To eliminate the influence of users’ inherent experiences and evaluations of commonly available e-commerce products’ AIGC on the experimental results, we created a virtual e-commerce product brand. For ease of operation, only a language description was provided to inform the users about the enterprise and the product, but in real circumstances, the design would include more product and scenario factors. Additionally, this study was not a field study. Although we used a real AIGC platform in the experiment and took measures to ensure that the users actually used the platform for creation, the quality of AIGC and the results of the user engagement were only evaluated using user self-assessment scales, which inevitably leads to differences from real behavior and thus affects the external validity of the research results.

(2) In this study, variables were measured using a maturity scale developed by foreign scholars. Although it has good reliability and validity and has been widely adopted, this scale cannot fully reflect the uniqueness of the AIGC context. Therefore, in the future, new scales designed specifically for the field of AI services need to be developed.

(3) Using the painting AIGC scenario, this research studied the differentiated impact of AIGC interface on user engagement, revealing the mechanism of influence from the perspective of content quality. Future studies can further explore other AIGC platforms (such as ChatGPT-4 and DeepSeek-V3), and the influencing relationship from different perspectives, such as user psychology and behavior, to enrich relevant theories, like user interaction value co-creation and user engagement in the AIGC context. This study also explored the boundary conditions of the model from the perspective of both novice and non-novice users. However, the types of users can be very diverse, especially regarding variables such as user motivation and other related factors. However, in the non-novice group, there was no significant difference in the impact of the AIGC interface type on user engagement, which may due to the complex interaction (e.g., usage motivations and preferences) between user usage motivation and user type. Future research can further investigate the applicability of the model for different types of users based on motivations, preferences and demographic variables.

Author Contributions

Z.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis; M.Q. and L.S.: data curation, validation, writing—original draft preparation. Z.Y.: writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant no.21AGL016); Project of Zhejiang Gongshang University Intelligent Management Institute of China, Zhejiang Provincial Key Research Base of Philosophy and Social Sciences; National Social Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22FGLB090); Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. 24GLB007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Company Introduction

In the experiment, the text began as follows: “Welcome to learn about us—“Taste World Inheritance”! We are an innovative enterprise dedicated to integrating traditional Chinese food culture with modern design concepts. Our mission is to offer young people a brand-new taste and visual experience through elaborately designed new Chinese-style pastries. Our products are not merely pastries; they are also carriers of cultural inheritance and innovation. The upcoming new Chinese-style pastry series aims to capture traditional flavors while incorporating modern aesthetics and health concepts. Each pastry design integrates Chinese elements with modern minimalist style, aiming to become a favorite among food lovers. Our core values are “Inheritance, Innovation, Deliciousness, and Aesthetics”. We encourage our designers to deeply explore traditional culture while boldly innovating and pursuing outstanding design expressions. After reading this introduction, we believe you have gained a preliminary understanding of our enterprise. Now, please let your imagination run wild and create an eye-catching new Chinese-style pastry appearance design for this dynamic and innovative enterprise! We look forward to your works!”

Table A1.

Measurement items and reliability tests.

Table A1.

Measurement items and reliability tests.

| Variable Code | Measurement Item | Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extraction | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIGC Accuracy (QA) | QA1 | The generated content is designed according to my requirements | 0.809 | 0.894 | 0.859 | 0.894 |

| QA2 | The generated content truly expresses my thoughts | 0.890 | ||||

| QA3 | The generated content fits my needs | 0.875 | ||||

| AIGC Innovation(QI) | QI1 | The form of the design is completely new compared to what it was before | 0.702 | 0.852 | 0.770 | 0.881 |

| QI2 | Elements that have never been used before appear in the generated content | 0.796 | ||||

| QI3 | The generated content is a significant change from the general digital image | 0.797 | ||||

| QI4 | The generated content exceeded my expectations | 0.776 | ||||

| User Engagement (CE) | UE1 | I really like this form of AIGC interface | 0.857 | 0.942 | 0.855 | 0.837 |

| UE2 | I’m passionate about this AIGC interface | 0.838 | ||||

| UE3 | I will take the initiative to pay attention to the application of AIGC interface | 0.860 | ||||

| UE4 | I want to know more about the features of the AIGC interface | 0.877 | ||||

| UE5 | I like to use this AGCI interface for customization | 0.870 | ||||

| UE6 | I would introduce this form of AIGC interface to others | 0.870 | ||||

| Overall Fit Indices | χ2 = 1.25 RMSEA = 0.04 CFI = 0.99 TLI = 0.99 GFI = 0.93 SRMR = 0.05 | |||||

Table A2.

Measurement items and reliability tests.

Table A2.

Measurement items and reliability tests.

| Variable Code | Measurement Item | Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extraction | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIGC Accuracy (QA) | QA1 | The generated content is designed according to my requirements | 0.929 | 0.955 | 0.875 | 0.963 |

| QA2 | The generated content truly expresses my thoughts | 0.937 | ||||

| QA3 | The generated content fits my needs | 0.940 | ||||

| AIGC Innovation (QI) | QI1 | The form of the design is completely new compared to what it was before | 0.970 | 0.985 | 0.944 | 0.905 |

| QI2 | Elements that have never been used before appear in the generated content | 0.971 | ||||

| QI3 | The generated content is a significant change from the general digital image | 0.973 | ||||

| QI4 | The generated content exceeded my expectations | 0.971 | ||||

| User Engagement (CE) | CE1 | I really like this form of AIGC interface | 0.953 | 0.983 | 0.910 | 0.967 |

| CE2 | I’m passionate about this AIGC interface | 0.955 | ||||

| CE3 | I will take the initiative to pay attention to the application of AIGC interface | 0.949 | ||||

| CE4 | I want to know more about the features of the AIGC interface | 0.948 | ||||

| CE5 | I like to use this AGCI interface for customization | 0.961 | ||||

| CE6 | I would introduce this form of AIGC interface to others | 0.954 | ||||

| User Type (UT) | UT1 | I have knowledge of painting design | 0.974 | 0.989 | 0.950 | 0.933 |

| UT2 | I think I know a lot about composition design | 0.978 | ||||

| UT3 | I compose and design more often than the people around me | 0.976 | ||||

| UT4 | I have a lot of ideas for character design | 0.974 | ||||

| UT5 | I am confident in my ability of composition and design | 0.971 | ||||

| Overall Fit Indices | χ2 = 1.67 RMSEA = 0.06 CFI = 0.92 TLI = 0.91 GFI = 0.93 SRMR = 0.06 | |||||

Table A3.

Variable Correlations and discriminant validity.

Table A3.

Variable Correlations and discriminant validity.

| QA | QI | CE | UT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QA | 0.972 | |||

| QI | −0.2605 | 0.936 | ||

| CE | 0.0488 | 0.2749 | 0.954 | |

| UT | 0.0488 | −0.1039 | 0.0329 | 0.975 |

Note: The square roots of the AVE are shown on the diagonal.

References

- McKinsey. The Top Trends in Tech. 2024. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/nl/our-insights/the-top-trends-in-tech (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Bock, D.E.; Wolter, J.S.; Ferrell, O.C. Artificial intelligence: Disrupting what we know about services. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.S.; Kim, Y.K. The role of the human-robot interaction in consumers’ acceptance of humanoid retail service robots. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J. Enhancing user experience with conversational agent for movie recommendation: Effects of self-disclosure and reciprocity. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2017, 103, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, S. Mobile marketing interface layout attributes that affect user aesthetic preference: An eye-tracking study. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Basu, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kaur, S. Interactive voice assistants—Does brand credibility assuage privacy risks? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, A.; Tucker, C. When does retargeting work? Information specificity in online advertising. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Qiu, D. A review of cooperation models between human and artificial intelligence. Chin. J. Inf. 2020, 39, 137–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Suh, H.; Heo, J.; Choi, Y. AI-driven interface design for intelligent tutoring system improves student engagement. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.08976. [Google Scholar]

- Żyminkowska, K.; Zachurzok-Srebrny, E. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Customer Engagement and Social Media Marketing—Implications from a Systematic Review for the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, D.; de Ruyter, K.; Huang, M.-H.; Meuter, M.; Challagalla, G. Getting smart: Learning from technology-empowered frontline interactions. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegger, A.; Klein, J.F.; Merfeld, K.; Henkel, S. Technology-enabled personalization in retail stores: Understanding drivers and barriers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.J.; Reinhard, D.; Schwarz, N. To judge a book by its weight you need to know its content: Knowledge moderates the use of embodied cues. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangrath, A.W.; Peck, J.; Hedgcock, W.; Xu, Y. Observing product touch: The vicarious haptic effect in digital marketing and virtual reality. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Ko, E.; Joung, H.; Kim, S.J. Chatbot e-service and customer satisfaction regarding luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1978, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C.; Prat, J. Job market signaling and employer learning. J. Econ. Theory 2012, 147, 1787–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuroy, S.; Desai, K.; Talukdar, D. An empirical investigation of signaling in the motion picture industry. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. The contributions of the economics of information to twentieth century economics. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 1441–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elitzur, R.; Gavious, A. Contracting, signaling, and moral hazard: A model of entrepreneurs, ‘angels,’ and venture capitalists. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lin, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.E. How do users adopt AI-generated content (AIGC)? An exploration of content cues and interactive cues. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekadakis, M.; Katrakazas, C.; Clement, P.; Prueggler, A.; Yannis, G. Safety and impact assessment for seamless interactions through human-machine interfaces: Indicators and practical considerations. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, L.M.; Santoso, H.B.; Junus, K. Designing asynchronous online discussion forum interface and interaction based on the community of inquiry framework. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2022, 23, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, A.S.; Hildebrand, C.; Häubl, G. Machine talk: How verbal embodiment in conversational AI shapes consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Res. 2023, 50, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wien, A.H.; Peluso, A.M. Influence of human versus AI recommenders: The roles of product type and cognitive processes. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, M.; Janiszewski, C.; Neumann, M.M. The influence of avatars on online consumer shopping behavior. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, M.; Krishen, A.S.; Gironda, J.T.; Fergurson, J.R. Exploring AI technology and consumer behavior in retail interactions. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 3132–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, C.; Zhao, W. Unlocking the impact of user experience on AI-powered mobile advertising engagement. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 4818–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, J.; Sun, D. What drives AIGC product users to keep coming back? Unveiling the key factors behind continuance intention. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 13059–13073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Shen, L. Research on the effects of AIGC advertisement on prosumer behavior. Econ. Manag. Innov. 2024, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Che, C. How AI overview of customer reviews influences consumer perceptions in e-commerce? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, B.T. The triple helix of digital engagement: Unifying technology acceptance, trust signaling, and social contagion in generation Z’s social commerce repurchase decisions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, X. Do dynamic signals affect high-quality solvers’ participation behavior? evidence from the crowdsourcing platform. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; McKechnie, S. Task facilitative tools, choice goals, and risk averseness: A process-view study of e-stores. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1572–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Dutta, S.; Stremersch, S. Customizing complex products: When should the vendor take control? J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Modular architectures in the marketing process. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremyr, I.; Valtakoski, A.; Witell, L. Two routes of service modularization: Advancing standardization and customization. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Yin, D.; Zhang, H. Bots with feelings: Should AI agents express positive emotion in customer service? Inf. Syst. Res. 2022, 34, 1296–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, S.; Mitra, D.; Wang, Q. Ask or infer? Strategic implications of alternative learning approaches in customization. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Brady, M.K.; Huang, M.-H.; Kim, T.W.; Jiang, L.; Duhachek, A.; Lee, H.; Garvey, A. Do you mind if I ask you a personal question? How AI service agents alter consumer self-disclosure. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Pardo, C. Artificial intelligence and SMEs: How can B2B SMEs leverage AI platforms to integrate AI technologies? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 107, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Bonezzi, A.; Morewedge, C.K. Resistance to medical artificial intelligence. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E. Anthropomorphized artificial intelligence, attachment, and consumer behavior. Mark. Lett. 2022, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechel, E.C.; Janiszewski, C. A lot of work or a work of art: How the structure of a customized assembly task determines the utility derived from assembly effort. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cong, Z. The daily me versus the daily others: How do recommendation algorithms change user interests? Evidence from a knowledge-sharing platform. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 60, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.H.; Rust, R.T. Artificial intelligence in service. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I.; Yu, T. Service-sales ambidexterity: Evidence, practice, and opportunities for future research. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Sun, W.; Liu, X.; Min, X.; Zhai, G. A perceptual quality assessment exploration for AIGC images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Brisbane, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; pp. 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Hosanagar, K.; Nair, H.S. Advertising content and consumer engagement on social media: Evidence from Facebook. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 5105–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Gao, W.; Han, B. Are AI chatbots a cure-all? The relative effectiveness of chatbot ambidexterity in crafting hedonic and cognitive smart experiences. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Dass, M. Applications of artificial intelligence in B2B marketing: Challenges and future directions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 107, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Jun, M.B.G. Immersive and interactive cyber-physical system (I2CPS) and virtual reality interface for human involved robotic manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Slotegraaf, R.J. Brand-embedded interaction: A dynamic and personalized interaction for co-creation. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.D.; Pracejus, J.W. Customized advertising: Allowing consumers to directly tailor messages leads to better outcomes for the brand. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.J.; Ryoo, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, J.A. Chatbot advertising as a double-edged sword: The roles of regulatory focus and privacy concerns. J. Advert. 2022, 52, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.H.; Rust, R.T. A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. The effectiveness of AI salesperson vs. human salesperson across the buyer-seller relationship stages. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, A. Recommendations as personalized marketing: Insights from customer experiences. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Donkers, B.; van Dijl, P.; Dellaert, B.G.C. Digital customization of consumer investments in multiple funds: Virtual integration improves risk-return decisions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K.L. What makes online content viral? J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J.; Sands, S.; Karpen, I. Product customization: A profile of consumer demand. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.L.; Chou, J.C.L.; Dong, T.P. Innovations and communication through innovative users: An exploratory mechanism of social networking website. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Zhang, J. How does customer recognition affect service provision? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 900–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Ewing, M.T.; Cooper, H.B. Artificial intelligence focus and firm performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Li, Y. Who made the paintings: Artists or artificial intelligence? The effects of identity on liking and purchase intention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, R.; Mullin, C.; Scheerlinck, B.; Wagemans, J. Putting the art in artificial: Aesthetic responses to computer-generated art. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018, 12, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M.; Prügl, R. Extending lead-user theory: Antecedents and consequences of consumers’ lead userness. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; He, H.; Zhu, F. Consumer creativity in new product development: The influence of product innovation task and consumer knowledge on consumer product creativity. Manag. World 2010, 02, 80–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J. How perceived cognitive needs fulfillment affect consumer attitudes toward the customized product: The moderating role of consumer knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeds, R. Cognitive and attitudinal effects of technical advertising copy: The roles of gender, self-assessed and objective consumer knowledge. Int. J. Advert. 2004, 23, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klesse, A.-K.; Cornil, Y.; Dahl, D.W.; Gros, N. The secret ingredient is me: Customization prompts self-image-consistent product perceptions. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D.; Pantano, E. Artificial intelligence and the new forms of interaction: Who has the control when interacting with a chatbot? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Troutman, T.; Kuss, A.; Mazursky, D. Experience and expertise in complex decision making. Adv. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- von Walter, B.; Kremmel, D.; Jäger, B. The impact of lay beliefs about AI on adoption of algorithmic advice. Mark. Lett. 2022, 33, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, R.; Jing, B.; Seidmann, A. Adoption of Internet-based product customization and pricing strategies. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2000, 17, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Seo, Y.; Septianto, F.; Ko, E. Luxury customization and self-authenticity: Implications for consumer wellbeing. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, C.; Häubl, G.; Herrmann, A. Product customization via starting solutions. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of consumer expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Nazarian, A.; Ziyadin, S.; Kitchen, P.; Hafeez, K.; Priporas, C.; Pantano, E. Co-creating brand image and reputation through stakeholder’s social network. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, W.J. Psychological reactance to online recommendation services. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleye, K.; Gemmel, P.; Rangarajan, D. Managing Engagement Behaviors in a Network of Customers and Stakeholders:Evidence from the Nursing Home Sector. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Choi, J.; Qualls, W.; Han, K. It takes a marketplace community to raise brand commitment: The role of online communities. J. Mark. Manag. 2008, 24, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).