Abstract

Consumer digital hoarding is becoming increasingly common in agricultural live social e-commerce, where the abundance of product information, seasonal promotions, and origin-based narratives make consumers more inclined to accumulate digital content such as product links, coupons, and live-stream screenshots. This phenomenon not only affects consumers’ digital mental health, consumption behavior, and decision-making ability, but also poses challenges to agricultural merchants and platforms in terms of customer conversion, precision marketing, and supply chain management. Drawing on the SOR model and integrating construal level theory, this paper constructs a research framework to analyze the key factors influencing consumers’ willingness to digitally hoard in the context of agricultural live social e-commerce. Based on a questionnaire survey of 322 consumers, and using the Ordered Probit (O-Probit) model, the empirical results show that emotional interaction significantly influences digital hoarding intention through the chain mediating effects of emotional attachment and fear of missing out (FOMO). Furthermore, social distance and immersion serve as boundary conditions in this mechanism. Our findings not only deepen the understanding of consumer digital hoarding behavior in agricultural live e-commerce, but also provide new insights for agricultural merchants and platforms to better design interaction strategies, balance consumers’ digital accumulation with actual purchasing conversion, and enhance the efficiency of agricultural product marketing.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of agricultural live social e-commerce in China, especially in the sales of tea, fruits, and other regional agricultural products, the digital content associated with goods such as origin stories, quality certifications, seasonal promotions, and ecological farming demonstrations is becoming increasingly diverse. Consumers are frequently exposed to such rich information in live streams, and their tendency to accumulate digital content—such as saving product links, coupons, or screenshots of agricultural product demonstrations—has become more prevalent, gradually forming the phenomenon of consumer digital hoarding in agricultural live social e-commerce. Digital hoarding as a new type of hoarding first appeared in the case report of Martine J van Bennekom et al. (2015) [] and George Sweeten et al. (2018) [], were the first to qualitatively analyze and theorize the potential causes of digital hoarding from a behavioral perspective, defining it as the phenomenon in which an individual accumulates a large number of digital files or data that are difficult to delete. The potential consequences of digital hoarding include cluttering the digital space and difficulties in managing resources []. One study revealed a strong link between digital hoarding behaviors and feelings of anxiety and stress [], with many participants reporting that they felt anxiety from the inability to delete or organize their digital files, which will be even worse as the number of files continues to increase [,,,]. Digital hoarding behavior not only affects personal life, but may also have an adverse effect on work efficiency and organizational management [,].

Digital hoarding refers to the persistent accumulation and difficulty in discarding a large number of digital files or data (Van Bennekom et al., 2015; Sweeten et al., 2018) [,]. Unlike normal information collection or bookmarking behavior, digital hoarding involves a strong sense of possession over digital items, anxiety about information loss, and difficulties in management. In this study, we define consumer digital hoarding as the tendency to repeatedly save or store digital resources—such as live-stream product links, screenshots, or coupons—in live social e-commerce contexts. This behavior extends beyond information storage to reflect a psychological pattern characterized by emotional attachment and fear of missing out (FOMO). In traditional purchasing decision-making, consumers usually take the initiative to collect information in order to design a purchasing decision plan. In agricultural live social e-commerce, storytelling of product origin, ecological cultivation methods, and farmers’ efforts has become an important means of increasing consumer engagement. Combined with algorithmic recommendations, consumers are often passively exposed to massive agricultural product information. Since the cost of storing data for consumers in this context is almost negligible, they tend to hoard data for fear of missing important shopping opportunities and product information. This behavior leads to the infinite accumulation of digital content. Consequently, digital hoarding has become a unique link and an important phenomenon in the process of consumer purchase decision-making in agricultural live social e-commerce, particularly when consumers fear missing seasonal harvests or exclusive origin-based offers. Consumer digital hoarding in live social e-commerce may bring at least two results. On the one hand, the digital content of consumers’ collections may eventually be transformed into real purchasing behavior; on the other hand, consumers obtain a sense of psychological satisfaction through digital hoarding, which replaces the actual need to purchase. As shown in a study under the framework of the psychological ownership theory, the authors suggest that even if consumers do not physically own a certain item, they can still “perceive ownership” of the item through a kind of psychological state of perceived ownership []. In fact, customer conversion in live social e-commerce is a key factor and the most challenging aspect of this business model. According to the report provided by Avery Consulting, in 2023, the number of viewers of live e-commerce on the two social content platforms, Douyin and Kuaishou, will reach 563.53 billion, while the conversion rate of purchases will be only 4.8%. The digital hoarding accompanied by information overload has exacerbated the psychological burden and ‘choice barrier’ of social e-commerce consumers []. This not only prolongs the decision-making process of consumers, but also affects the efficiency of their purchase decisions. Moreover, the anxiety and uncertainty generated by consumers during the shopping process further affects their subjective well-being and shopping satisfaction, and under the interactive effects of cognitive load and emotional fluctuations, consumers show complex psychological processes in their participation in live social e-commerce []. In a live video, a social e-commerce anchor said bitterly that his fans had ‘not dropped an episode, not a single order’ for three years. Consumers digital hoarding has an important impact on social e-commerce consumer behavior and consumers product purchase conversion, as well as merchants and platforms marketing strategies, and thus has become an important topic worthy of study.

In the digital era, information communication and interactivity have changed significantly and are shaping people’s behaviors in multiple areas of society []. Live social e-commerce has become an important shopping channel and leisure platform for Chinese consumers because of its communication interactivity, content entertainment and information richness. According to the 53rd Statistical Report on the Development Status of the Internet in China released by the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC), as of June 2024, the scale of China’s live webcasting users has reached 777 million, of which the scale of live e-commerce users is as high as 597 million []. Unlike social self-media, live social e-commerce fundamentally aims at profit-making and is thus designed with rich immediacy and high-frequency emotional interaction to enhance marketing stimulation and consumer feedback. Emotional interaction not only enhances consumer engagement and strengthens consumers’ emotional investment in digital content containing commodity information [,], but also intensifies consumers’ anxiety about the loss of potential benefits or information. Therefore, interactivity, as an essential feature of live social e-commerce, is crucial to understand consumers’ digital hoarding willingness in live social e-commerce in terms of emotional interaction. Against this backdrop, research on live-streaming e-commerce and emotional interaction has also shown a rapid upward trend. Zhang and Xu (2024) [], drawing on the theory of value co-creation, revealed the dynamic formation process of consumer engagement mechanisms in live-streaming commerce. Liu et al. (2025) [], from the perspective of emotional contagion, empirically examined how emotional interaction on social media drives the diffusion of cross-border e-commerce impulse buying behavior. Zhang et al. (2025) further found that situational presence and interaction in tourism live streaming exert a double-edged effect, simultaneously generating positive engagement and psychological burden [].

In recent years, digital hoarding has attracted increasing attention in the academic field. For example, Sillence et al. (2023) found that digital hoarding involves not only difficulties in information management but also a strong association with individuals’ sense of data control and psychological need for security []. Khan et al. (2023) further pointed out that digital hoarding significantly predicts mental health risks among university students, indicating its potential behavioral pathological characteristics []. Studies have revealed the complexity of digital hoarding from various fields such as psychology and information management [,]; however, most of the studies mainly focus on the college students’ group or the social media field [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], and little attention has been paid to the consumer’s digital hoarding behaviors in the agricultural live social e-commerce. Moreover, the psychological mechanism of digital hoarding in the live social e-commerce based on the comprehensive perspective of online interaction is not yet not deep enough.

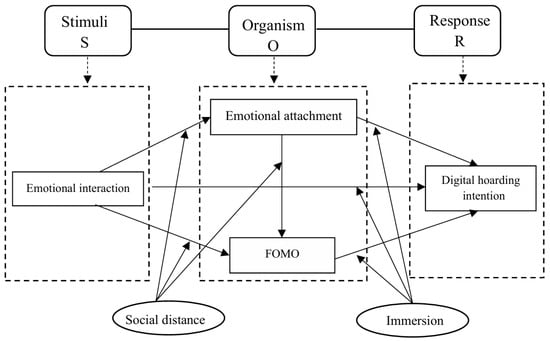

Using the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theoretical model as a basic framework, our study integrates Construal Level Theory (CLT) and Immersion Experience Theory to construct a comprehensive framework addressing two key research objectives: (1) exploring the complex psychological mechanisms by which emotional interaction affect consumers’ willingness to hoard digitally; and (2) exploring the boundary roles of social distance and immersion in live social e-commerce.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

The SOR model is a classic model of modern cognitive psychology. Stimulus represents the triggering factors of the external environment, Organism represents the individual’s internal psychological response, and Response denotes the behavioral performance of the individual. The SOR model is often used to analyze how external stimuli influence consumers’ decision-making behaviors by affecting their internal psychological processes []. In live social e-commerce, anchors quickly capture consumers’ attention and create a stimulating environment characterized by diverse emotional interaction. This triggers psychological responses, leading consumers to save and accumulate digital hoards of commodity information to satisfy emotional needs. Consequently, the SOR model is highly applicable to understanding these behaviors. Therefore, our study adopts the SOR framework to analyze how emotional interaction influence consumers’ digital hoarding intention by triggering psychological responses.

2.1. Live Social E-Commerce Emotional Interaction and Consumer Digital Hoarding

Live social e-commerce emotional interaction refers to the real-time or non-real-time exchanges and communications between consumers []. According to the theory of emotional affordance, emotional availability that mobilizes or triggers the audience’s emotions through multiple sensory modalities, such as visual, auditory, and verbal, can motivate them to produce emotional responses, such as excitement or empathy, and thus influence their behavioral decisions. In order to enhance the authenticity of consumers’ online purchasing experience, live social e-commerce companies usually design rich interaction strategies; on the one hand, emotional interaction can allow consumers to obtain product information in a timely manner and observe consumers’ timely feedback to promote their purchases. Moreover, emotional interaction can influence their purchasing decisions and behaviors by enhancing the audience’s emotional connectivity []. Simultaneously, live social e-commerce in the emotional interaction can also stimulate the audience’s engagement and social identification by triggering their emotional resonance, thus increasing their intention to hoard digital content.

Accordingly, our study hypothesizes the following:

H1:

Emotional interaction in live social e-commerce positively influences consumers’ digital hoarding intention.

2.2. Chain Mediation of Emotional Attachment and FOMO

Emotional Attachment (EA) is a strong emotional connection that an individual forms with an item, brand, or service. Emotional attachment usually includes emotional experiences such as pleasure, fondness, and a sense of belonging, and can significantly influence an individual’s behavioral intention and occurrence. Thorpe et al. (2019) investigated the link between emotional attachment, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and digital hoarding [], and found that emotional attachment not only deepens an individual’s dependence on digital content, but also promotes digital hoarding behavior. Emotional interaction in live social e-commerce enhanced consumers’ emotional connection with live social e-commerce, and when individuals became emotionally attached to these digital contents containing commodity information, they were more inclined to retain them and were unwilling to delete them even when this commodity information had been lost for purchase.

FOMO refers to the feelings of anxiety and uneasiness that individuals experience due to the fear of missing important opportunities, events, information, or social activities. It has been found that FOMO is usually accompanied by strong social comparisons and feelings of dissatisfaction with one’s own situation, especially when seeing others enjoying certain activities or obtaining certain benefits, and individuals become worried that they are missing out on similar experiences or opportunities [,].

Sedera et al. found that college students’ emotional attachment to digital possessions and fear of losing important information had a significant impact on digital hoarding through their study of digital hoarding behavior among college students []. They also found that in a live social e-commerce environment, consumers’ emotional attachment and FOMO may jointly influence digital hoarding intention through a chain mediation effect. Specifically, affective interactions enhance consumers’ attention and emotional attachment to certain items, and this emotional attachment may trigger FOMO, i.e., consumers’ fear of missing out on important items or promotional opportunities. Thus, in affective interactions, emotional attachment further drives consumers’ digital hoarding behavior through FOMO. Accordingly, this paper hypothesizes the following:

H2:

Live social e-commerce emotional interaction influence consumers’ digital hoarding intention through the chain mediation of emotional attachment and FOMO.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Social Distance

Levels of Interpretation Theory (CLT) postulates that individuals create mental representations of objects or perceived events based on their varying degrees of psychological distance [] Psychological distance (Sense of Belongingness) is the distance between something and the self or the subjective experience of distance, which generally consists of four dimensions: temporal distance (present vs. future), social distance (self/similarity vs. others/difference), spatial distance (near vs. far), and hypothetical distance (going to happen vs. could happen) []. These distances is often used to explain how consumers make different levels of cognitive and behavioral decisions about goods and information based on the proximity of their psychological distance. One study used the level of explanation theory to investigate the effect of ‘creative description’ on customers’ purchase intention in an e-commerce context [], which concluded that when the psychological distance is far, consumers tend to adopt an abstract mode of thinking, focusing on the overall value of the goods and the long-term goals, whereas when the psychological distance is closer, consumers adopt a concrete mode of thinking, focusing more on the overall value of the goods and the long-term goals. Social distance refers to the subjective perception of an individual’s relationship with other social members (e.g., friends, family, strangers, etc.). It covers not only the sense of closeness in interaction with others, but also the individual’s position in the social network and the sense of psychological distance when interacting with others. As an important constituent dimension of psychological distance, social distance is more suitable for explaining the motivation and depth of consumer participation in live social e-commerce activities in live social e-commerce. When consumers feel closer social distance with the anchor, they consider the goods recommended by the anchor more credible, willing to invest in real-time interaction with the anchor, and hence are more inclined to agree with the anchor’s recommendations and product information, which in turn strengthens the tendency to retain digital resources. Meanwhile, social distance plays a reinforcing role in live social e-commerce. The closer the social distance, the stronger the consumer’s sense of engagement in the interaction, and the anchor triggers the consumer’s emotional arousal through personal emotional interaction through emotional availability. When consumers feel they are more closely interacting with the anchors, they think they may miss important offers or exclusive recommendations, which results in stronger FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), in which case consumers are more inclined to stock up on digital content to avoid missing out on important information or not being able to access similar offer opportunities in the future.

Accordingly, this paper hypothesizes the following:

H3:

Social distance plays a moderating role in the effect of emotional interaction on emotional attachment in live social e-commerce anchors.

H4:

Social distance plays a moderating role in the effect of live social e-commerce anchors’ affective interactions on FOMO.

H5:

Social distance plays a moderating role in the effect of emotional arousal on FOMO.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Immersion

Immersion refers to a consumer’s sense of deep engagement and focus on the virtual environment in a live social telecast [,]. In the context of live social e-commerce, immersion is not merely a perceptual state but a multidimensional psychological experience that reflects consumers’ focused attention, emotional involvement, and perceived presence within the live-stream environment. It captures how interactive features, real-time communication, and vivid product displays jointly stimulate consumers’ sense of “being there” with the anchor and products. Within the SOR framework, immersion functions as an organism-level psychological response that bridges external emotional stimuli and behavioral outcomes. Therefore, the concept of immersion is theoretically adequate and contextually relevant for explaining the depth of consumer engagement in agricultural live social e-commerce. Previous researchers have studied the role of consumer immersion in engagement using AR devices, and studies have shown that immersion can enhance consumer engagement [,,]. Compared with traditional e-commerce, live social e-commerce not only shows consumers the goods, but also allows them to enter the interpersonal interactive environment through rich social interactions, which provides the participants’ sensory ‘the degree to which it provides an inclusive, extensive, surrounding, and vivid illusion of reality’ creating a sense of immersion []. When consumers gain a high level of immersion in live interactions, they are more likely to fully engage themselves in the interaction and ignore external distractions, resulting in a stronger sense of identification and emotional connection with the live content, as well as a stronger digital hoarding intention, On the contrary, low immersion may make it difficult for consumers to sustain their attention to the content of live social e-commerce companies, reducing their intention to accumulate digital content.

Research suggests that arousal can play a role in the impact of emotions in perception and information. In particular, attachment and anxiety, which are positively aroused emotions, produce stronger effects in more immersive contexts []. Thus, immersion can amplify the effects of emotional attachment and FOMO. When consumers have a high sense of immersion in live social e-commerce, they become more immersed in the emotional connection with the anchor or the product, further exacerbating the anxiety of missing important information, and thus are more inclined to hoard digital content related to live social e-commerce in case they miss important information or potential opportunities, Hence, customers are more inclined to save digital content related to live broadcasts, such as product recommendations, interaction records, and so on. This high level of immersion further enhances the effects of emotional attachment and FOMO on digital hoarding intention. Conversely, low levels of immersion may make the effects of emotional attachment and FOMO on consumers’ digital hoarding intention weaker. This hypothesis is as follows:

H6:

Immersion plays a moderating role in the emotional interaction of live social e-commerce on consumers’ digital hoarding intention.

H7:

Immersion moderates the effect of emotional attachment on consumers’ willingness to hoard digitally.

H8:

Immersion moderates the effect of missing out anxiety on consumers’ willingness to hoard digitally.

Based on the above theoretical analyses and research hypotheses, the logical framework of our study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

The sample for our study consists of consumers who use live social e-commerce platforms like WeChat and Xiaohongshu. WeChat has become one of the most popular social media platforms globally, with active users reaching 1.343 billion in 2023. Xiaohongshu has around 300 million monthly active users, 72% of whom are Generation Y individuals. Users from these two platforms provide strong representation for this study. Our study collects questionnaires through the Internet by snowball sampling. To ensure the relevance of the sample, participants were required to have watched or purchased agricultural products via live social e-commerce within the past three months. The questionnaires were distributed through the “Questionnaire Star” platform, and each respondent who actually completed the questionnaire was paid RMB 2. The survey covered consumers in 12 provinces in China. A total of 356 questionnaires were distributed, and the research team eliminated duplicate and invalid questionnaires by comprehensively judging the time taken to complete the questionnaires, the IP address range and other information, 322 valid questionnaires are obtained. Invalid responses were excluded based on completion time (less than two minutes), duplicate IP addresses, and incomplete answers, resulting in a valid response rate of 90.4%.

3.2. Selection of Variables

The measurement scales used in this study were adapted from classic instruments in the fields of e-commerce, social interaction, and digital behavior, all of which have been validated in previous studies (Table 1). Specifically, six latent variables were measured: emotional interaction, emotional attachment, fear of missing out (FOMO), immersion, social distance, and digital hoarding intention.

Table 1.

Measurement variable question item sources and reliability and validity tests.

To ensure cultural and contextual equivalence, all items were translated into Chinese and back-translated into English following the procedure recommended by Brislin (1986) []. The wording of each item was slightly adjusted to fit the agricultural live social e-commerce context. Before the formal survey, a pilot test with 50 respondents was conducted to verify clarity and reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all constructs exceeded 0.83, indicating good internal consistency and contextual validity.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

According to the sample statistics (Table 2), of the 322 valid questionnaires, 124 (38.5%) were filled in by males and 198 (61.5%) by female. The age distribution of the sample is mainly concentrated in the two age groups 18–25 and 26–30, which represent 48.1% and 18.3% of the total sample, respectively. In the sample, the proportion of respondents with a bachelor’s degree is the highest at 66.1%, followed by those with a postgraduate degree and above at 13.4%, and in general, the sample has a relatively high level of education. Among the respondents, the highest frequency of using live social e-commerce is ‘once every few days’ with 40.4%, followed by ‘once a day’ with 31.7%, and most of the respondents used live social e-commerce more frequently. The sample is diverse in terms of gender, age, education level, frequency of use, etc., and the data can better reflect the characteristics of the target audience.

Table 2.

Results of descriptive statistics.

4.2. Data Reliability Analysis

The results of the reliability and validity tests (Table 3) showed that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all the constructs were greater than 0.80, the factor loadings of all the question items were greater than 0.50, the internal consistency of each scale was high with good reliability, and there was a strong correlation between the questions and their belonging to the constructs, which had good validity.

Table 3.

Results of reliability and validity tests.

Before running the cascade regression analysis, to ensure the reliability and interpretability of the results, we tested for multicollinearity by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results are shown in Table 4. The VIF values of all the variables are less than 10, indicating that the model does not suffer from serious multicollinearity problems and is suitable for regression analysis.

Table 4.

Multicollinearity test results.

We conducted a validated factor analysis of the latent variables to assess their discriminant validity. As shown in Table 5, the fit indices of the six-factor model (χ2/df = 2.65, RMSEA = 0.072, SRMR = 0.049, CFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.942) meet the model fit criteria and are optimal compared to other factor models. It can be concluded that the six variables selected for our study have strong discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

4.3. Regression Analysis

Before reporting the mediation and moderation analyses, we first verified the key assumptions and estimation checks of the ordered probit (O-Probit) model. The dependent variable—digital hoarding intention—was measured on a 5-point Likert scale and modeled as an ordered outcome. We verified the key assumptions for O-Probit: (i) independence of observations (each respondent appeared only once, and duplicate IPs were removed during data screening); (ii) absence of severe multicollinearity (all VIFs < 10, see Table 4); and (iii) the parallel-lines/proportional-odds restriction. For (iii), we conducted likelihood-ratio tests comparing the constrained O-Probit with a less-restricted generalized model, and the results did not indicate a significant violation (p > 0.05). These diagnostic results confirm that the O-Probit specification is appropriate for modeling the ordinal dependent variable in this study.

4.3.1. Mediating Effects Test

In this study, the previous hypotheses were tested using the O-probit model, using Stata16. To ensure the robustness of the results, the bootstrap method with 1000 resamples was applied to each test. The standard errors were recalculated using non-parametric bootstrapping, and the significance levels of all coefficients remained stable. Therefore, the results can be considered robust to resampling.

The results of the mediation effect test are shown in Table 6, model (1) is the regression result without adding control variables. In model (2), after adding control variables, the estimation results show that emotional interaction has a significant positive effect on the digital hoarding intention of live social e-commerce consumers, and hypothesis 1 is confirmed. Models (3) and (4) show the positive influence of emotional attachment and FOMO on digital hoarding of live social e-commerce consumers, respectively, and the regression results of model (5) show that live social e-commerce emotional interaction has a significant positive influence on digital hoarding intention through emotional attachment and FOMO, indicating the existence of a chain transmission of ‘emotional interaction → emotional attachment → FOMO → digital hoarding intention’. This indicates that there is a chain transmission mechanism of ‘emotional interaction → emotional attachment → misunderstanding anxiety → digital hoarding intention’, and hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Table 6.

Results of the mediation effect test.

4.3.2. Moderating Effects Test

To examine the moderating effects of social distance (SD) and immersion (IMM), both variables were measured using multi-item Likert scales and operationalized as the mean scores of their respective items. Prior to constructing the interaction terms, all continuous independent and moderating variables were mean-centered to reduce potential multicollinearity [].

The interaction terms were then created and entered into the regression models sequentially. The moderating effects were tested using the O-Probit regression model, controlling for demographic variables (gender, age, education). The significance of the moderating effects was assessed through the coefficients of the interaction terms, and robustness was verified using bootstrapped confidence intervals (1000 resamples).

The results of the moderating effect test are shown in Table 7. Models (6)–(8) show that social distance is positive in the effect of emotional interaction on emotional attachment and in the effect of FOMO, and positive in the effect of emotional attachment on FOMO, and the moderating effect is significant; thus, hypotheses H3–H5 are verified.

Table 7.

Results of the moderating effects of social distance.

Models (9)–(11) showed that immersion was positive in the effect of FOMO on intention to hoard numbers (Table 8), positive in the effect of FOMO on emotional attachment on intention to hoard numbers, and positive in the effect of emotional interaction on intention to hoard numbers, and the moderating effect was significant; thus, hypotheses H6–H8 were tested.

Table 8.

Results of the moderating effects of immersion.

4.3.3. Robustness Checks

To further ensure the robustness of the empirical results, we conducted three classes of sensitivity analyses.

- (a)

- Using an alternative link function, the ordered logit model produced substantively identical coefficient signs and significance levels.

- (b)

- Relaxing the proportional-odds restriction, a generalized O-Probit (partial proportional odds) yielded consistent focal effects.

- (c)

- Regarding measurement treatment, treating the composite digital-hoarding-intention score as approximately continuous in an OLS model with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors led to the same substantive conclusions.

These findings collectively confirm that the results are robust across alternative model specifications.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Based on the SOR model and the theory of planned behavior, combined with the technology acceptance model and the psychological ownership theory, our study explored the influencing factors of consumers’ digital hoarding behaviors in the context of agricultural live social e-commerce. Our study also verified the influence of factors such as affective interactions, emotional attachment and FOMO on the willingness of digital hoarding through empirical analysis.

The results indicate that emotional interaction significantly promotes digital hoarding behavior through emotional attachment and FOMO. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting that social interaction can enhance consumers’ psychological attachment and information-retention tendencies [,]. It also confirms that, in the live social e-commerce context, the emotional connection between anchors and consumers serves as an important psychological driver of information accumulation [,]. However, unlike traditional e-commerce, emotional interactions in agricultural live-streaming scenarios are more instantaneous and immersive. Such high-intensity emotional engagement not only amplifies consumers’ sense of identification and trust but may also trigger short-term “preventive storage” behaviors. It is worth noting that this mechanism may be moderated by individual consumer characteristics, such as self-control, digital literacy, and information-processing capability. For consumers with stronger self-regulation, the positive emotions stimulated by emotional interaction may not necessarily translate into hoarding behavior; instead, they tend to engage in selective saving or timely deletion to reduce information load. These findings suggest that the relationship between emotional interaction and digital hoarding is subject to contextual dependence and individual differences.

In addition, this study also highlights the potential negative consequences of digital hoarding. While moderate digital hoarding helps consumers gain a sense of security in an uncertain informational environment, excessive hoarding may lead to information redundancy and psychological strain. When consumers continuously accumulate a large number of unused product links, screenshots, or coupons, both information management costs and psychological anxiety increase, which may eventually cause decision fatigue and digital burnout. This indicates that although digital hoarding temporarily satisfies consumers’ emotional needs, it may, in the long term, result in dual cognitive and emotional depletion.

From a theoretical perspective, the findings of this study also offer several implications. First, the results demonstrate that emotional interaction stimuli exert a significant influence on consumers’ digital hoarding behavior. Although prior research has acknowledged the importance of online interactions in e-commerce, most studies have focused on outcomes such as purchase intention and engagement rather than information retention or psychological possession. By incorporating emotional attachment and FOMO as mediating mechanisms, this study extends the application of the SOR framework to the field of emotion–behavior transformation in agricultural live social e-commerce. Second, the study further uncovers the emotional and psychological mechanisms underlying digital hoarding. Unlike the existing literature that primarily explains digital hoarding from the perspectives of information management or technology acceptance, this study identifies and empirically validates a chain mediating path involving emotional attachment and FOMO, providing new insights into how emotions transform into behavioral intentions. Finally, by integrating two critical dimensions from CLT—social distance and immersion—this research further reveals the boundary conditions that shape the relationship between emotional drivers and digital hoarding. These findings enrich the theoretical explanation of digital hoarding behavior and provide a novel empirical foundation for understanding consumer psychology in agricultural live social e-commerce.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study suggests that agricultural live social e-commerce merchants should strengthen emotional interaction to enhance the emotional connection between consumers, anchors, and agricultural products, thereby prompting consumers to retain more relevant digital content (e.g., product links, promotional information) for future purchases.

In addition, merchants should adopt a well-designed emotional interaction mechanism. By enhancing consumers’ emotional attachment and triggering FOMO, consumers will be more likely to hoard agricultural product information. At the same time, strengthening immersion can help consumers stay more focused and engaged in the interaction, which will further promote digital hoarding behavior.

It is worth noting that digital hoarding may have a dual effect on consumer behavior in agricultural live social e-commerce. On the one hand, it can be an opportunity for merchants to potentially convert into real customers, and on the other hand, it may also cause decision fatigue due to over-accumulation of digital, or ‘think you have it, but instead of having it’. Merchants should balance the actual effect of such digital hoarding with reasonable promotional strategies to instantly guide consumers from digital hoarding to actual purchasing behaviors, so as to improve the conversion rate and overall sales performance of live social e-commerce.

Overall, the findings of this study provide practical guidance for multiple stakeholders in the agricultural live social e-commerce ecosystem. Agricultural merchants and live-streaming anchors can apply these insights to design more emotionally engaging yet responsible interaction strategies, improving consumer trust and conversion efficiency. E-commerce platforms may also benefit by developing algorithms and user interfaces that promote healthy digital engagement and reduce information overload. At the same time, policymakers and scholars can use these findings to better understand consumers’ digital well-being and formulate strategies to foster sustainable digital consumption behaviors.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the influencing factors of consumers’ digital hoarding behavior in the context of agricultural live social e-commerce, integrating the SOR framework with the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Technology Acceptance Model, and Psychological Ownership Theory. The empirical findings indicate that emotional interaction significantly promotes digital hoarding intention through the mediating effects of emotional attachment and FOMO. Moreover, social distance and immersion moderate these relationships, serving as important boundary conditions in the process. These results provide empirical support for extending the SOR model to explain emotionally driven digital behaviors in live social e-commerce. The findings suggest that emotional and immersive experiences may shape consumers’ digital information management behaviors by activating affective and cognitive responses. Practically, the study highlights the need for live-streaming practitioners and agricultural brands to design emotional interactions responsibly—stimulating engagement while avoiding excessive emotional arousal that may lead to digital fatigue or psychological strain. Taken together, the results correspond well with the research aims articulated in the introduction, providing empirical support for the proposed theoretical framework. Specifically, the study verified the internal psychological mechanism through which emotional interaction influences consumers’ digital hoarding intention, confirming the mediating roles of emotional attachment and FOMO. It also empirically demonstrated the moderating effects of social distance and immersion, revealing how contextual and experiential factors shape the emotional–behavioral pathway. These findings collectively offer a coherent explanation of emotionally driven digital hoarding in agricultural live social e-commerce.

Despite its valuable insights, this study is not without limitations. First, the data were collected through a cross-sectional survey, which restricts the ability to infer causal relationships between emotional interaction, emotional attachment, FOMO, and digital hoarding. Future studies could employ longitudinal or experimental designs to validate the dynamic and causal nature of these relationships. Second, the sample was limited to consumers from a single region in China, which may constrain the generalizability of the results. Future research could conduct cross-regional or cross-cultural comparisons to examine whether the observed mechanisms hold across different cultural and market contexts. Third, as the data were based on self-reported measures, potential common method bias and social desirability effects cannot be completely ruled out. Future studies are encouraged to adopt multi-source data (e.g., behavioral tracking or platform data) to improve measurement validity. Finally, while this study focused on agricultural live social e-commerce, future research could explore other product categories or digital platforms to test the boundary conditions of the proposed model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y. and X.Z.; methodology, X.Z.; software, Z.Y. and L.Z.; validation, L.Z. and W.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Y., L.Z. and W.Z.; investigation, Z.Y.; resources, L.Z.; data curation L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., L.Z. and W.Z.; visualization, Z.Y. and L.Z.; supervision, X.Z. and L.Z.; project administration, X.Z. and W.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Humanities and Social Sciences Project, grant number 24SKGH257. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with the Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans (China, 2023) and the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China (2021), this study involved only anonymous online questionnaires of adult consumers and did not collect any identifiable personal data or sensitive information. Therefore, it is deemed exempt from Ethics Committee approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the respondents and reviewers for their invaluable contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van Bennekom, M.J.; Blom, R.M.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. A case of digital hoarding. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015210814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeten, G.; Sillence, E.; Neave, N. Digital hoarding behaviours: Underlying motivations and potential negative consequences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, S.; Bolster, A.; Neave, N. Exploring aspects of the cognitive behavioural model of physical hoarding in relation to digital hoarding behaviours. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 2055207619882172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutley, S.K.; Read, M.; Martinez, S.; Eichenbaum, J.; Nosheny, R.L.; Weiner, M.; Mackin, R.S.; Mathews, C.A. Hoarding symptoms are associated with higher rates of disability than other medical and psychiatric disorders across multiple domains of functioning. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertusa, A.; Frost, R.O.; Mataix-Cols, D. ‘When hoarding is a symptom of OCD: A case series and implications for DSM-V’. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.D.; Watson, D. Hoarding and its relation to obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKellar, K.; Sillence, E.; Neave, N.; Briggs, P. Digital accumulation behaviours and information management in the workplace: Exploring the tensions between digital data hoarding, organisational culture and policy. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, W. Influencing Path of Consumer Digital Hoarding Behavior on E-Commerce Platforms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritze, M.P.; Marchand, A.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Benkenstein, M. Access-based services as substitutes for material possessions: The role of psychological ownership. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dölarslan, E.Ş.; Koçak, A.; Walsh, P. Perceived barriers to entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of self-efficacy. J. Dev. Entrep. 2020, 25, 2050016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Li, Q. The investigation of hedonic consumption, impulsive consumption and social sharing in e-commerce live-streaming videos. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Xi’an, China, 8–12 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, I.; Mamlok, D. Culture and society in the digital age. Information 2021, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; Leung, W.K.; Sharipudin, M.-N.S. The role of consumer-consumer interaction and consumer-brand interaction in driving consumer-brand engagement and behavioral intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Arcas, L.; Hernandez-Ortega, B.I.; Jimenez-Martinez, J. Engagement platforms: The role of emotions in fostering customer engagement and brand image in interactive media. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 559–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxon, A.M.; Hamilton, C.E.; Bates, S.; Chasson, G.S. Pinning our possessions: Associations between digital hoarding and symptoms of hoarding disorder. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2019, 21, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Consumer engagement in live streaming commerce: Value co-creation and incentive mechanisms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Khatibi, A.; Tham, J. The impact of social media emotional contagion on the diffusion of cross-border e-commerce impulse buying behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Xue, J.; Zhao, Y. Beneficial or troublesome? Revealing the double-edged effects of tourism live streaming affordances on viewers’ engagement. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2025, 42, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillence, E.; Dawson, J.A.; Brown, R.D.; McKellar, K.; Neave, N. Digital hoarding and personal use digital data. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Nadeem, A.; Saleem, M. Digital hoarding as predictor of mental health problems among undergraduate students. Online Media Soc. 2023, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oravec, J.A. Digital (or virtual) hoarding: Emerging implications of digital hoarding for computing, psychology, and organization science. Int. J. Comput. Clin. Pract. (IJCCP) 2018, 3, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Song, T.; Li, L.; Jiang, W.; Gao, X.; Shu, L.; Liu, Y. Research on personal digital hoarding behaviors of college students based on personality traits theory: The mediating role of emotional attachment. Libr. Hi Tech 2024, 43, 1210–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Abdullah, H.; Ahrari, S.; Abdullah, R.; Nor, S.M.M. Exploration of vulnerability factors of digital hoarding behavior among university students and the moderating role of maladaptive perfectionism. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241226962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.Q.; Wu, W.-Y.; Liao, Y.-K.; Phung, T.T.T. The extended SOR model investigating consumer impulse buying behavior in online shopping: A meta-analysis. J. Distrib. Sci. 2022, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ding, J.; Akram, U.; Yue, X.; Chen, Y. An empirical study on the impact of e-commerce live features on consumers’ purchase intention: From the perspective of flow experience and social presence. Information 2021, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, B.H.; Rahman, S.J.; Al-Mofraje, S.A. The Effect of Emotional Interaction on Purchasing Intention. World Bull. Soc. Sci. 2023, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Riordan, B.C.; Cody, L.; Flett, J.A.M.; Conner, T.S.; Hunter, J.; Scarf, D. The development of a single item FoMO (fear of missing out) scale. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alutaybi, A.; Al-Thani, D.; McAlaney, J.; Ali, R. Combating fear of missing out (FoMO) on social media: The FoMO-R method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Liberman Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.-S.; Shao, J.-B.; Zhang, H. Is creative description always effective in purchase intention? The construal level theory as a moderating effect. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, N.C.; Nordahl, R.; Serafin, S. Immersion revisited: A review of existing definitions of immersion and their relation to different theories of presence. Hum. Technol. Interdiscip. J. Humans ICT Environ. 2016, 12, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peukert, C.; Pfeiffer, J.; Meißner, M.; Pfeiffer, T.; Weinhardt, C. Shopping in virtual reality stores: The influence of immersion on system adoption. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2019, 36, 755–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; Smith, A.N. Augmented reality: Designing immersive experiences that maximize consumer engagement. Bus. Horizons 2016, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Chylinski, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I. Let Me Imagine That for You: Transforming the Retail Frontline through Augmenting Customer Mental Imagery Ability. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Wilbur, S. A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 1997, 6, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, M.C.; Pérez, D. Comparison of the levels of presence and anxiety in an acrophobic environment viewed via HMD or CAVE. Presence Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 2009, 18, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, F.R.; Voss, K.E. An alternative approach to the measurement of emotional attachment. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jennett, C.; Cox, A.L.; Cairns, P.; Dhoparee, S.; Epps, A.; Tijs, T.; Walton, A. Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, J.M.; Brumby, D.P.; Gould, S.J.; Cox, A.L. Development of a questionnaire to measure immersion in video media: The Film IEQ. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, Manchester, UK, 5–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, P.; Cox, A.; Berthouze, N.; Dhoparee, S.; Jennett, C. Quantifying the experience of immersion in games. In Proceedings of the Cognitive Science of Games and Gameplay workshop at Cognitive Science, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–29 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Safin, V.; Rachlin, H. A ratio scale for social distance. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2020, 114, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J.P.; MacLachlan, D.L. MacLachlan. Social distance and shopping behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1990, 18, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, N.; Briggs, P.; McKellar, K.; Sillence, E. Digital hoarding behaviours: Measurement and evaluation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedera, D.; Lokuge, S. Is digital hoarding a mental disorder? Development of a construct for digital hoarding for future IS re-search. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2018), University of Southern Queensland, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett, R.L.; Benedek, J. Measuring emotional valence to understand the user’s experience of software. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P. Measuring emotion: Development and application of an instrument to measure emotional responses to products. In Funology 2: From Usability to Enjoyment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lee, M.K.; Zhao, D. Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behavior on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Choi, S.M.; Sohn, D. Building customer relationships in an electronic age: The role of interactivity of E-commerce Web sites. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liang, X.; Xie, T.; Wang, H. See now, act now: How to interact with customers to enhance social commerce engagement? Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).