Abstract

With the rapid growth of e-commerce and rising demand for faster, reliable last mile delivery, optimizing the spatial layout of terminal logistics facilities is critical. This paper proposes a two-stage location framework for mini-depots and lockers considering spatiotemporal customer demand. In the first stage, Affinity Propagation (AP) clustering identifies candidate mini-depot locations and locker layouts based on temporal and spatial demand characteristics. In the second stage, an Adaptive Heuristic Electric Eel Foraging Optimization (AHEEFO) determines the optimal mini-depot location strategy to minimize total cost. A dataset of 1157 Beijing customer points, including latitude, longitude and demand information, is used for model validation. Results show that Scenario 2, with dispersed demand, outperforms Scenario 1 and traditional strategies in both total cost and customer satisfaction; dispersed demand can be effectively supported via crowdsourced delivery and locker layout, whereas concentrated demand requires more professional courier resources. Comparative experiments reveal AP clustering is more stable, reducing clustering-stage cost by 13.57% compared with K-means, and AHEEFO outperforms other algorithms in cost optimization, computational efficiency, and significance tests under random demand surges. Finally, the sensitivity analysis highlights the effects of different algorithmic and operational parameters, offering valuable insights for both managerial practice and academic research.

1. Introduction

Modern supply chains are placing increasingly higher demands on logistics facilities, which now require significantly larger areas compared to traditional warehouses [1]. However, the growing scarcity of available urban land has forced many logistics facilities to relocate to suburban or even more remote areas. At the same time, the number of small and aging logistics facilities in densely populated urban regions continues to decline [2]. This spatial shift in logistics facility distribution toward the urban periphery is known as logistics sprawl, a phenomenon that has been observed and validated in cities around the world [3,4]. Concurrently, e-commerce is experiencing rapid development, and the widespread adoption of digital technologies has further accelerated the shift in consumer shopping behavior toward online channels [5]. Data indicate that by 2026, global e-commerce revenue is expected to exceed 8.2 trillion USD, accounting for 24% of total global retail sales. As the world’s largest e-commerce market, China recorded online sales of 1.57 trillion USD in 2021. The e-commerce ecosystem has become an integral part of modern life in China, profoundly reshaping traditional industrial structures and business models while offering significant convenience to consumers [6]. However, compared to business-to-business (B2B) logistics, business-to-consumer (B2C) last mile delivery is more decentralized and has more pronounced negative externalities, such as urban traffic congestion and increased carbon emissions [7]. In addition, the design of e-commerce logistics systems differs fundamentally from that of traditional brick-and-mortar retail, with a core focus on rapid response and flexible delivery. As a result, it is essential to establish highly mobile and adaptable logistics facilities in close proximity to customers. The operation of these facilities must also contend with real-world challenges such as urban traffic restrictions and limited parking availability. Therefore, resolving the conflict between logistics facility layout and customer delivery demands, as well as the contradiction between limited urban land supply and the rapid growth in logistics land demand, has become a critical challenge for last mile delivery.

Although existing research has pointed out that logistics sprawl does not necessarily lead to decreased system efficiency or increased negative externalities [8], for e-commerce logistics systems that rely on high timeliness and wide coverage, the concentration of facilities on the urban fringe still poses significant challenges. Against this backdrop, proximity logistics, a strategy that embeds logistics facilities within high-density, mixed-use urban areas, has gradually emerged as a key topic in urban logistics policy research [9]. To address urban delivery difficulties, both academia and industry have recently promoted the development of crowdsourced delivery models. These models aim to improve system flexibility and resource utilization by mobilizing social resources and integrating multiple stakeholders [10,11].

Against this research background, this paper innovatively applies the two-stage decision-making approach to the joint location problem of mini-depots and lockers, and considers the dynamic demand of customer points from a spatiotemporal perspective. In the first stage, the clustering stage, existing studies have widely adopted the K-means algorithm to generate candidate locations [12]. However, due to its tendency to converge to local optima, K-means is limited in achieving globally optimal solutions. Recent research has shown that the Affinity Propagation (AP) clustering algorithm is more suitable for global optimization in logistics facility location problems [13,14]. Therefore, this paper adopts the AP clustering algorithm, first identifying candidate locations for mini-depots based on spatiotemporal distance, and then performing a second round of clustering on customer points within each cluster to determine the locations of lockers. In the second-stage optimization process, Nasr et al. [15] highlighted that considering delivery routes during the location selection stage helps reduce overall operational costs. This paper adopts a macro-level perspective to incorporate the crowdsourced delivery model, determining which mini-depot should serve a customer point requesting home delivery and which locker customers should use for parcel pickup. While most existing research focuses on minimizing costs [16,17,18,19], customer time satisfaction is equally critical for consumer-facing mini-depots and lockers [20,21]. Therefore, the two-stage location model proposed in this paper aims to jointly optimize location costs and customer satisfaction, thereby identifying facility layout plans with greater practical value.

Finally, to solve the proposed large-scale location model, this paper improves the Electric Eel Foraging Optimization (EEFO) algorithm [22] and introduces a Heuristic Adaptive Electric Eel Foraging Optimization (AHEEFO) algorithm. By incorporating spatial constraints that reflect actual urban distribution characteristics and improving the initial solution generation strategy, the algorithm enhances convergence speed and stability while increasing adaptability to large-scale, multi-constraint logistics location problems. Experimental results demonstrate that AHEEFO outperforms current mainstream methods across multiple performance indicators, showcasing strong practicality and robustness.

The innovations of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- The main contribution of this paper lies in extending the two-stage location model from the literature, from a spatiotemporal perspective, to the location problem of mini-depots and lockers.

- (2)

- This paper optimizes the locations of lockers and mini-depots through a two-stage location model, balancing location costs and customer satisfaction, and innovatively addresses the multi-facility, multi-attribute location problem in logistics.

- (3)

- Unlike existing studies that focus on micro-level delivery efficiency, this paper adopts a macro-level perspective to introduce the crowdsourced delivery model and systematically explores its application in last mile delivery location selection in the context of e-commerce.

- (4)

- This paper proposes an improved AHEEFO, which optimizes the initial solution generation process through a spatial constraint mechanism, thereby accelerating the convergence speed and enhancing the stability of the algorithm.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows: First, the relevant literature is reviewed to introduce the research background. Then, the research methodology is presented. This is followed by experiments and an analysis of the results, including case analysis, algorithm comparison, and sensitivity analysis, along with managerial recommendations. Finally, the study is concluded by highlighting its theoretical contributions, research limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crowdsourced Last Mile Delivery in E-Commerce

With the rapid development of e-commerce, customers are demanding faster and more punctual deliveries [23]. Therefore, last mile delivery (LMD), as the most critical stage, must achieve fast, low-cost, and highly reliable performance [24]. Traditionally, LMD involves home delivery of parcels to individual addresses. Although new approaches such as urban consolidation centers and carrier-based point-to-point platforms have emerged [25], issues related to delivery flexibility, timeliness, and cost remain unresolved. One emerging LMD model has attracted growing attention: a shift from professional freight (PF) to crowdsourced delivery involving ordinary individuals [10]. Numerous studies have highlighted the advantages of crowd-shipping, such as high flexibility [26] and efficient resource utilization [18], which can significantly reduce delivery costs for retailers [27,28,29] and help alleviate urban traffic congestion [30]. However, most of these studies focus only on the operational level of crowd-shipping and do not consider the location of supporting logistics infrastructure [18]. Moreover, as e-commerce continues to grow, customer expectations for faster and cheaper delivery services are also rising [27], making it increasingly important to examine how crowd-shipping can enhance customer satisfaction in e-commerce LMD. Despite these advantages, recent critical perspectives argue that crowd-shipping research has overlooked key behavioral and economic dimensions. For instance, Nascimento et al. [31] highlight that business models for green crowd-shipping are often based on unrealistic assumptions, underestimating challenges such as user participation, cost sharing, and economic viability. Similarly, Oliveira et al. [32] stress that successful crowd-shipping systems require integrated mobility-as-a-service strategies and micro-hub networks, which are not adequately addressed in purely operational models. These insights underline that user willingness-to-participate, platform-side incentives, and policy frameworks are crucial determinants of feasibility—factors largely absent from current optimization-oriented studies.

2.2. Mini-Depots and Lockers

On one hand, the traditional LMD model based on home delivery may result in diseconomies of scale, leading to higher delivery costs [33] and failed deliveries (e.g., when customers are not at home, [34]). Therefore, better alternatives are urgently needed for e-commerce LMD. One such alternative is lockers, where packages are deposited for customers to retrieve at their convenience. This method has shown potential for improving customer experience [20]. A substantial body of research has demonstrated the functional [33,35,36] and economic [33,37] advantages of lockers, confirming their role as critical logistics infrastructure in e-commerce LMD. On the other hand, the increasing delivery frequency driven by e-commerce has pushed logistics facilities closer to city centers, exacerbating urban issues such as traffic congestion, pollution, and road safety concerns [10]. To address these challenges, Rai et al. [9] proposed the proximity logistics strategy, which involves placing logistics facilities in locations closer to end consumers for more efficient and faster delivery. In the e-commerce era, almost every household can become a delivery endpoint [38]. A considerable number of logistics facilities have been specially designed to meet online retailers’ needs for timeliness and diversified services [39]. Achieving these goals depends not only on higher levels of warehouse automation [39] but also on the rational spatial layout and siting of warehouses and terminal facilities such as lockers [40]. Hence, the scientific planning of terminal logistics facilities is essential to relieve delivery pressure in urban cores and improve the overall efficiency and sustainability of the delivery system. However, due to their high fixed costs and large land requirements, traditional warehouses lack siting flexibility and cannot effectively support the goals of proximity logistics [16]. In response, small-scale logistics facilities, such as micro-consolidation centers (MCCs) and mini-depots, have emerged as promising alternatives in LMD to reduce costs and improve efficiency (see Table 1 for relevant studies). Compared to MCCs, mini-depots have lower construction costs, greater geographic proximity to customer points, and are more suitable for implementing crowd-shipping models [18]. Moreover, prior studies have confirmed the feasibility and rationality of their coordinated layout [16]. However, most of these studies only consider the location problem of spatial dimension, ignoring the time dimension. Considering that mini-depot to achieve ‘proximity logistics’ is a time-sensitive problem, this paper introduces a spatio-temporal clustering model into the location problem. Nevertheless, the planning and acceptance of mini-depots and lockers are not purely technical issues. Lozzi et al. [41] demonstrate that participatory policy planning and stakeholder engagement play a central role in the success of urban logistics facilities. Without the involvement of local communities, businesses, and policymakers, even technically sound facility siting strategies may fail to gain legitimacy or widespread adoption. This indicates that spatial models must be embedded in broader governance and co-creation frameworks, a dimension often overlooked in the existing LMD literature.

Table 1.

Summary of literature on mini logistics facility location.

2.3. Two-Stage Location Framework

The identification of candidate locations is a critical step in the facility location problem. However, most existing studies assume that candidate locations are predefined [21]. In reality, candidate locations are often unknown [46]. Thus, rather than relying on predefined sites, this paper uses clustering algorithms in the first stage to generate candidate locations for mini-depots and final locations for lockers. Clustering algorithms (e.g., Affinity Propagation and K-means) are commonly used in data mining and have been widely applied in facility location [21,46,47,48,49], logistics task assignment [28], and route optimization [14]. These algorithms are compatible with intelligent optimization methods and are suitable for constructing two-stage location models [12,13,21]. Compared with K-means, Affinity Propagation does not require predefining the number of clusters, offers more globally optimal results, and has lower computational complexity [50]. After determining the candidate locations, the second-stage location problem can be formulated as a multi-facility optimization problem. This type of problem has been widely studied in various contexts, such as selecting optimal locations for forward distribution centers (FDCs) from a set of candidates [21], green logistics center location [47], and electric vehicle charging station placement [19,51,52]. Based on this, the clustering stage is designed to identify representative candidate locations from large-scale and heterogeneous customer points, thereby capturing the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of demand. Building on this, the optimization stage integrates service capacity and operational costs, which enhances the practicality and robustness of the model in e-commerce settings. Although such frameworks improve methodological rigor, the absence of behavioral, economic, and participatory perspectives may constrain their applicability. As suggested by Nascimento et al. [53] and Oliveira et al. [32], without incorporating incentive design, willingness-to-participate, and governance mechanisms, optimization models risk overlooking the very drivers that determine system adoption. Therefore, this study not only contributes to the methodological advancement of clustering-based two-stage siting but also explicitly recognizes the need for embedding such models into broader socio-economic and policy contexts.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Description

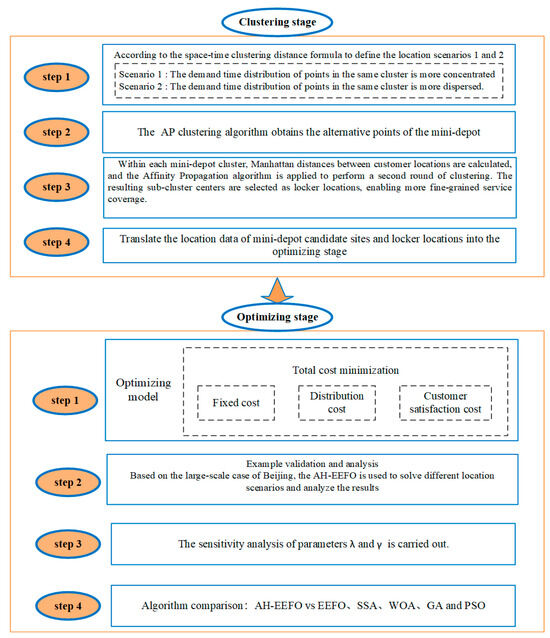

This paper proposes a two-stage location framework, as shown in Figure 1, aiming to optimize the crowdsourced delivery strategy from a system-level perspective. By rationally deploying mini-depots and lockers, the framework seeks to reduce delivery costs and enhance customer satisfaction, thereby providing valuable insights for the optimization of e-commerce last mile delivery (LMD) systems. Two location scenarios are defined based on a spatiotemporal distance formula among customer points. Scenario 1 (burst demand) refers to clusters where customer requests are temporally concentrated within narrow time-windows. Scenario 2 (dispersed demand) refers to clusters where customer requests are distributed across wider time-windows. These two scenarios characterize different temporal patterns of demand and serve as the basis for subsequent clustering and facility location decisions. In the clustering stage, based on the spatiotemporal distance formula, the AP clustering algorithm is first applied to identify candidate locations for mini-depots from all customer points. Then, a second round of clustering is performed on the customer points within each cluster to determine the locker locations.

Figure 1.

Two-stage location model framework.

3.2. Assumptions

In large-scale data scenarios, ignoring package transshipment between mini-depots reduces model constraints, improves solution efficiency, and facilitates algorithm convergence. Nevertheless, this simplification may result in idle capacity in some depots and overload in others, thereby lowering overall efficiency. Furthermore, if a depot fails or its capacity becomes insufficient, the associated customers may not receive timely service. To mitigate these limitations, this study adopts a candidate location approach, following Chen et al. [21], which enhances system flexibility and robustness. The main assumptions are as follows:

- (1)

- The supply capacity of each mini-depot is sufficient to meet the delivery demands of its assigned customer points.

- (2)

- Each customer demand point and locker package is served exclusively by a single mini-depot, and inter-depot package transfer is not allowed.

- (3)

- Within each mini-depot’s service area, the demand time distribution of customer points is assumed to be known and predictable.

3.3. Model Establishment

3.3.1. Model Notation Definition

The parameter definition of the two-stage location model is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of the mathematical model.

3.3.2. Clustering Stage

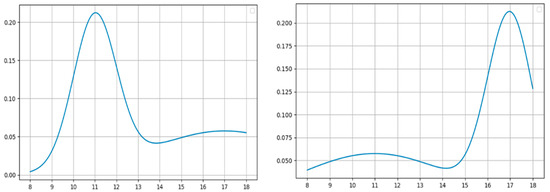

Firstly, the spatiotemporal distance formula between customer points is introduced. In this paper, the temporal demand characteristics of customer points are generated using a bimodal normal distribution function, as shown in Figure 2 and Equation (1). According to the research by Guidotti et al. [54], based on the actual parcel delivery schedules in the express delivery industry, the time interval is set from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. The parameters are set as μ1 = 11, μ2 = 17, δ = 12, and σ = 1. By randomly generating the corresponding parameter α of the bimodal distribution, different temporal demand characteristics of customer points are simulated. Equation (2) defines the time lag order between two points, which is a lag variable in time series analysis. It represents the relationship between the current time point and data from a past time point. Equation (3) calculates the Manhattan distance between two spatial points, which more realistically reflects the actual delivery paths in grid-like urban road networks compared to Euclidean distance [55,56]. Equation (4) represents the spatiotemporal distance between two points in Scenario 1. In this scenario, the time lag between customer points is minimized to reflect situations where customer demands occur close together in time. In contrast, Equation (5) corresponds to Scenario 2, where the time lag between customer points is maximized, indicating that customer demands are more dispersed over time.

Figure 2.

Bimodal orthonormal distribution function diagram.

3.3.3. Optimizing Stage

Equation (6) represents the fixed cost, which includes the monthly rental fee of mini-depots and the rental cost of lockers. The number of lockers is determined based on the number of parcels within the service coverage area of each locker, thereby calculating the corresponding monthly rental cost. As shown in Equations (7) and (8), a stochastic demand surge mechanism is introduced [57], is the demand surge probability, is the demand surge multiple, and the uncertain facility location environment is added to the model. At the same time, when crowdsourced delivery is within the delivery distance threshold, it is considered normal delivery; if it exceeds the threshold, a delivery compensation fee is added, which is determined by the parameter .

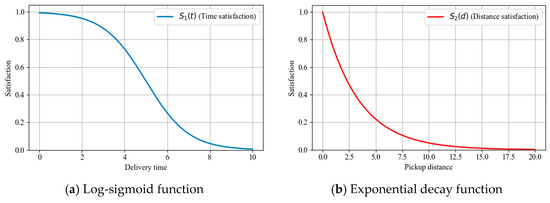

Customer satisfaction consists of two parts: the satisfaction with home delivery service and the satisfaction with self-pickup service. First, the customer time satisfaction function is constructed. Log-sigmoid function is used to model the customer time satisfaction [58], as shown in Equation (9) and Figure 3a. This function provides a utility-like measure of service timeliness, with satisfaction values ranging from 0 to 1. The parameter γ controls the decay rate of the log-sigmoid curve, reflecting customers’ sensitivity to delivery delays. Specifically, represents the maximum waiting time that customer demand point j is willing to accept, v denotes the average delivery speed of crowdsourcing distributors, and is the actual delivery time from mini-depot i to customer demand point j. By integrating these parameters, the function realistically models how varying delivery times relative to customer tolerance affect perceived service satisfaction. Equation (10) further defines the home delivery satisfaction based on this time-related utility. Similarly, Equation (11) and Figure 3b model customer self-pickup satisfaction using a distance-based utility function, where the satisfaction value also lies within (0,1]. θ represents the decay constant, capturing how quickly satisfaction decreases as the distance increases, and D2 denotes the preferred self-pickup distance for customers. This allows the model to realistically reflect customer preferences for convenience in parcel collection. Equation (12) then specifies the self-pickup satisfaction according to this distance utility. The objective function of this model is to minimize the total cost, as presented in Equation (13), the Cost–Satisfaction Trade-off Coefficient α is introduced to balance the relative importance between cost and customer satisfaction in the objective function.

Figure 3.

Customer satisfaction functions.

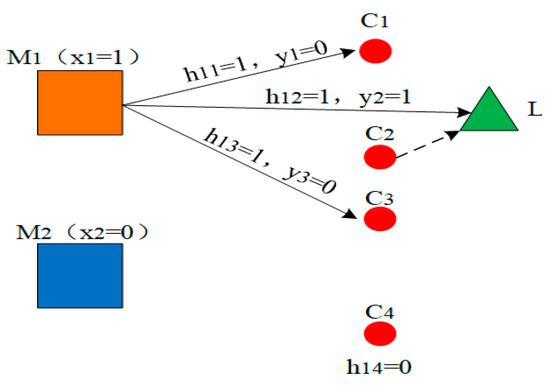

Finally, the detailed objective function and constraint conditions are presented in Formulas (14) to (18). Equation (14): At least one and at most all candidate mini-depots can be selected. Equation (15): Each customer must be served by exactly one mini-depot. Equation (16): A customer can only be assigned to a mini-depot if that depot is selected. Equation (17): If a mini-depot is not selected, it cannot serve any customers. Equation (18): The distance between an assigned customer and its mini-depot must not exceed the maximum allowed distance D. And Equation (19) involves three decision variables: , and . As shown in Figure 4, variable determines whether a mini-warehouse candidate is selected. For example, if x2 = 0, M2 is not chosen and thus cannot perform any delivery tasks. If M1 is selected (x1 = 1), the delivery endpoint depends on the customer’s choice: if a customer chooses self-pickup (e.g., y2 = 1), the package is delivered to a locker (e.g., L1) that serves the customer; if home delivery is chosen (e.g., y1 = 0, y3 = 0), the package is delivered directly to the customer’s address. Additionally, delivery feasibility is constrained by service distance: customers within range (e.g., C1, C2, C3 with h11 = h12 = h13 = 1) can be served, while those outside the range (e.g., C4 with h14 = 0) cannot.

Figure 4.

The schematic diagram of binary decision variable , , .

4. Two-Stage Heuristic Algorithm

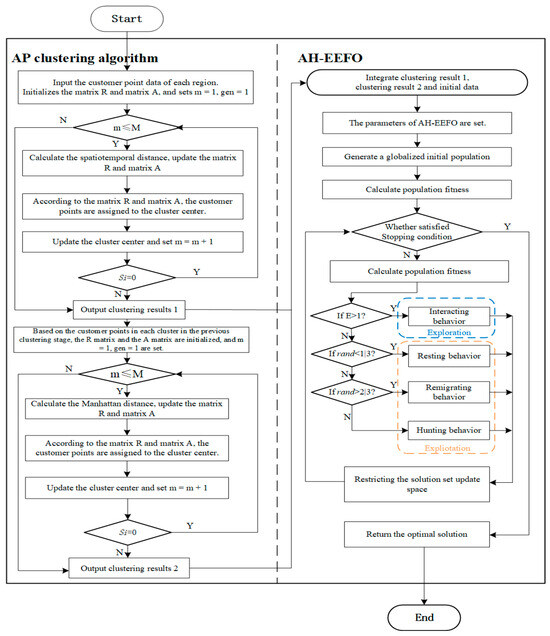

4.1. Clustering Stage: AP Clustering Algorithm

AP clustering is an algorithm that partitions a dataset into different clusters based on specific criteria. Its core objective is to maximize the similarity between data points within the same cluster while maximizing the dissimilarity between points in different clusters [13]. In Table 3, Compared to other mainstream clustering algorithms, AP clustering has significant advantages in handling large-scale data: it offers high computational efficiency and does not require manual pre-specification of the number of cluster centers. This feature is particularly critical in large-scale location selection problems. Owing to these strengths, AP clustering can reliably and effectively determine candidate locations for mini-depots in the first stage of the site selection process.

Table 3.

The advantages and disadvantages of AP, K-Means and DBSCAN clustering algorithm.

Step 1: Enter the customer set and initialize the similarity matrix S (similarity), the attraction matrix R (responsibility) and the attribution matrix A (availability).

Step 2: Calculate the R matrix. a (i, k′) represents the attribution degree value of other customer points to i customer points other than k point customers. s (i, k′) indicates the attractiveness of other customer points except k customer points to i customer points. r (i, k) indicates the cumulative proof that customer point k becomes the clustering center of customer point i.

Step 3: Calculate the A matrix. R (j, k) represents the similarity value of customer point k as the clustering center of other customer points except customer point i.

Step 4: Update the R matrix and A matrix. To avoid oscillation, the AP algorithm introduces the damping factor λ when updating the information. The damping factor λ is a real number between 0 and 1.

Step 5: Calculate the value of E = R + A, if the maximum value of the i-th customer row is located at the k customer point, it means that the clustering center of customer i is at the sample k. If the value of E does not change for a long time, exit the loop, otherwise jump to step 2.

Step 6: End of the algorithm. Output the clustering result of the customer set and the coordinate result of the cluster center k.

4.2. Optimizing Stage: Adaptive Heuristic Electric Eel Foraging Optimization

4.2.1. Algorithm Introduction

Adaptive Heuristic Electric Eel Foraging Optimization (EEFO) was proposed by Zhao et al. [22] in 2024, inspired by the predatory behavior of electric eels in nature. The EEFO algorithm has demonstrated good performance in solving complex optimization problems. However, it exhibits high randomness during the initial solution generation phase, which may lead to instability and abnormal solutions during multiple iterations. In addition, the algorithm struggles to converge quickly to the optimal solution in the later stages of optimization. To address these issues, this paper proposes improvements to EEFO.

4.2.2. Fitness Function and Initial Solution

The objective function of the two-stage location model aims to minimize the total cost. Accordingly, the fitness function used in AHEEFO is also designed to minimize the objective function, ensuring that the minimum value of the fitness function corresponds to the minimum value of the objective function. During the initial solution generation process of the algorithm, a solution vector containing multiple variables is created. This solution vector consists of three parts: a zero matrix representing the number of customer points, a binary matrix indicating whether the candidate mini-depot locations are selected, and a binary matrix indicating whether customer points choose to receive home delivery service. These three parts are combined to form a complete solution vector, ensuring dimensional consistency. The randomly generated initial solution is then used to evaluate the current optimal value of the objective function.

4.2.3. Algorithm Principle

The development and exploration phase of EEFO is inspired by the foraging behavior of electric eels, including their interactions, resting, migration, and hunting behaviors.

- (1)

- Interacting behavior

When electric eels encounter a school of fish, they form an “electric ring” through swimming and stirring to encircle the prey. In the algorithm, each eel represents a candidate solution, with the best-performing one regarded as the target prey. Electric eels conduct global exploration by sharing position information and update their positions by comparing the difference between a randomly selected eel and the population center. At the same time, they also interact based on positional differences with other eels. According to Equations (24)–(26), this mechanism significantly enhances EEFO’s exploration across the search space. Among them, and are random numbers in the interval (0, 1); is the fitness value of the i-th electric eel candidate solution; is the position of a randomly selected eel from the current population (j ≠ i); n is the population size; is another random number in the interval (0, 1); r is a random vector within the interval (0, 1); Low and Up represent the lower and upper bounds of the interaction region for the electric eels, respectively.

- (2)

- Resting behavior

Before performing resting behavior, electric eels define a resting region. To improve search efficiency, this region is set by projecting one randomly selected dimension of the eel’s position onto the main diagonal of the normalized search space. Both the search space and eel positions are scaled to the [0, 1] range. This projected position is regarded as the center of the eel’s resting region, as shown in Equations (27)–(30). Once the resting region is determined, the eel moves to that area to rest, as described in Equations (31) and (32). The resting behavior of the electric eel is represented by Equations (33) and (34).

- (3)

- Hunting behavior

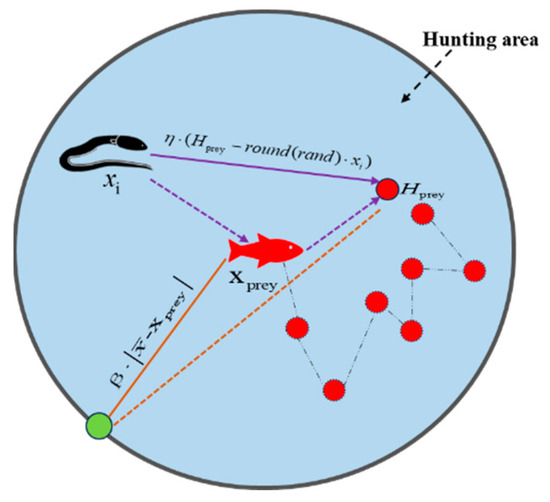

When electric eels detect prey, they cooperate to form an electric circle and communicate through low-voltage discharges. As interaction increases, the circle shrinks, driving the prey into shallow waters and making them easier to catch. This causes the prey to move rapidly within the hunting region, which is defined by Equations (35) and (36). Therefore, a new position for the electric eel can be generated within the hunting region based on its previous position, as shown in Equations (37) and (38). represents the scale of the hunting region, and is a random number in the interval (0, 1). The scale decreases over time, causing the hunting region to gradually shrink. The hunting behavior is characterized by a spiral motion, where the eel’s position is updated to the prey’s new location. Figure 5 illustrates the hunting behavior of electric eels. When the prey is surrounded, certain positions marked by red dots represent movement traces generated as the prey dives. At this point, the eels attack the prey through a spiral motion and use these position traces to update their locations in the next iteration.

Figure 5.

Hunting behavior of electric eels diagram.

- (4)

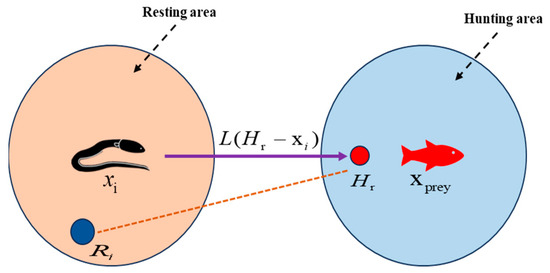

- Migrating behavior

As shown in Equations (39) and (40), when prey is detected, electric eels tend to migrate from the resting region to the hunting region. Figure 6 illustrates this migration behavior. Eels sense prey location via low-voltage discharges and adjust their positions in real time. If prey is perceived nearby, they move to a candidate position; otherwise, they remain stationary. The position update is defined by Equation (41).

Figure 6.

Migration behavior electric eels diagram.

4.2.4. The Improvement Strategy of Limiting the Solution Space

EEFO exhibits high randomness during the initial solution generation phase, which may lead to unstable and abnormal solutions across multiple iterations. This limits the quality of solutions and makes it difficult to adapt to large-scale, multi-constraint logistics location scenarios. To address this issue, a constraint is imposed on the solution space after the electric eel completes the interaction, resting, hunting, and migration behaviors. Specifically, upper and lower boundary constraints ( and ) are defined to ensure that all solutions remain within a valid range, thereby avoiding the generation of invalid solutions, as shown in Equation (42). AHEEFO can converge more quickly to better solutions and reduce unnecessary exploration in invalid regions. This forms a spatial constraint mechanism tailored to actual regional distributions.

4.3. Two-Stage Heuristic Algorithm Procedure

Two-stage heuristic algorithm procedure is shown in Figure 7. The two-stage heuristic algorithm can systematically solve the two-stage location model of mini-depots and lockers. The pseudocode of AHEEFO is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 AHEEFO (Adaptive Heuristic Electric Eel Foraging Optimization) | |

| Input: Set parameters n and T. Randomly initialize the eel population Xi (i = 1,…,n), The population contains continuous variable part and discontinuous variable part (decision variable). And then evaluate their fitness Fiti, and Xprey is the best solution found so far. | |

| Output: The best solution Xprey | |

| 1 | while the stopping condition is not satisfied do |

| 2 | for each eel Xi do |

| 3 | Calculate E. |

| 4 | if E >1 |

| 5 | Perform the interacting behavior. |

| 6 | Evaluate the fitness Fiti. |

| 7 | Limit the update space of the current solution. |

| 8 | else |

| 9 | if rand > 1/3 |

| 10 | Determining the resting region. |

| 11 | Perform the resting behavior. |

| 12 | Evaluate the fitness Fiti. |

| 13 | Limit the update space of the current solution. |

| 14 | else If rand > 2/3 |

| 15 | Perform the migrating behavior. |

| 16 | Limit the update space of the current solution. |

| 17 | else |

| 18 | Determining the hunting region. |

| 19 | Perform the hunting behavior. |

| 20 | Limit the update space of the current solution. |

| 21 | end If |

| 22 | Update each eel’s position. |

| 23 | end For |

| 24 | Update the best solution found so far X |

| 25 | end While |

| 26 | return Xprey. |

Figure 7.

The algorithm flow chart of two-stage heuristic algorithm.

5. Example Validation and Analysis

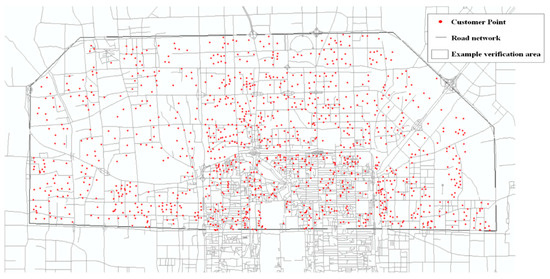

5.1. Generation of Problem Instances and Parameter Settings

This case study was conducted in a selected region of Beijing, as illustrated in Figure 8. Residential complexes, apartment communities, commercial buildings, and university dormitories within this area were identified as customer points, resulting in the selection of 1157 customer locations. Subsequently, using ArcMap 10.8 software and the CGCS2000_3_Degree_GK_CM_117E coordinate system, these geographic coordinates were converted into projected coordinates. Additionally, each customer point was assigned randomly generated attributes, including preferred parcel receipt time, daily demand volume, maximum acceptable waiting time, and preferred self-pickup distance. Randomly generated customer preferences are used to capture heterogeneity in service expectations. Specifically, the acceptable maximum waiting time Lj is set within the range of 1200–1800 s, while the preferred self-pickup distance D2 is randomly drawn from 500 to 800 m. These uncertain parameters reflect typical customer tolerance and convenience considerations in parcel collection, and are consistent with the approach in existing studies that simulate variations in customers’ willingness to wait or travel for services [21,37,59,60]. Table 4 presents sample information for 30 representative customer points from this dataset. Table 5 clarifies the units, meanings and values of all parameters, and notes the data sources at the end of the table. The algorithm parameters are set as follows: in the AP clustering algorithm, the damping factor λ is set to 0.7; in AHEEFO, the population size is set to 40, and the number of iterations is set to 200. These data are only for simulation and do not represent the actual values. The algorithms were implemented using PyCharm Community Edition 2024.3.1.1 on a Windows 11 operating system. The computer used has 16 GB of RAM and a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-13700HX CPU with a base frequency of 2.10 GHz.

Figure 8.

The research area of case analysis in this paper.

Table 4.

Information of some customer points.

Table 5.

Experimental parameter settings.

Data sources: Parameters such as , F1, F2, r and v are derived from the survey data of Dongcheng District, Beijing. The value of α is reasonably verified by sensitivity analysis. All other parameters are sourced from relevant literature [21,61].

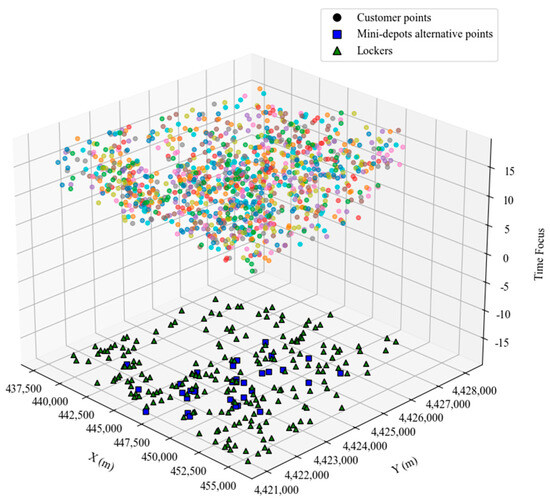

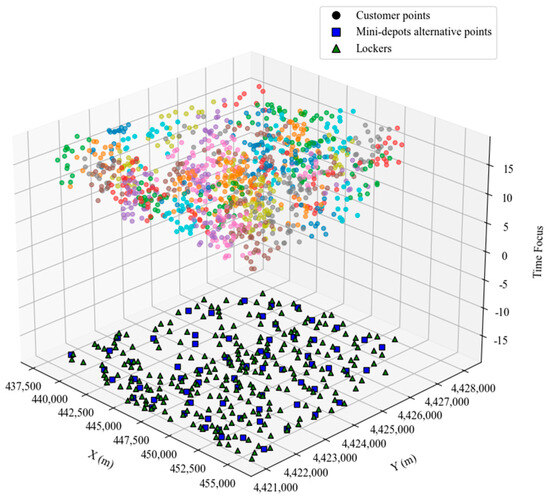

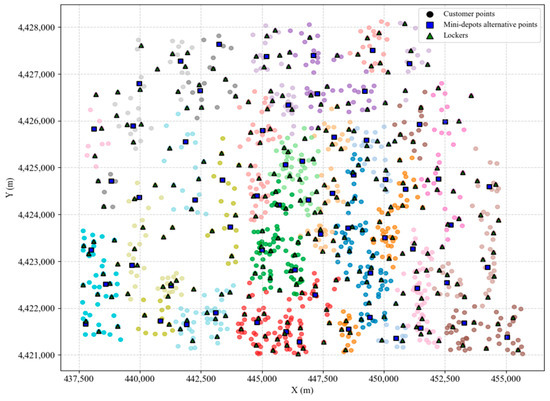

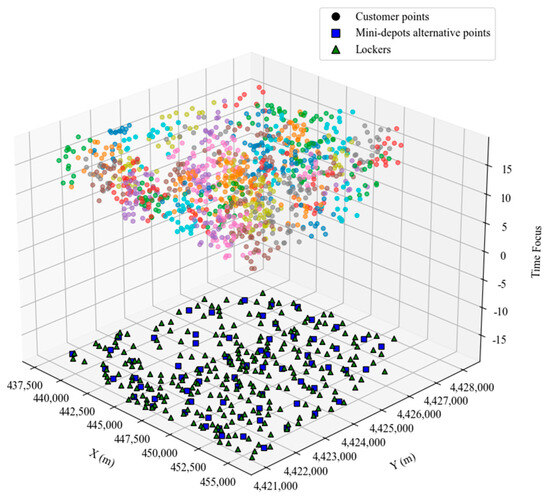

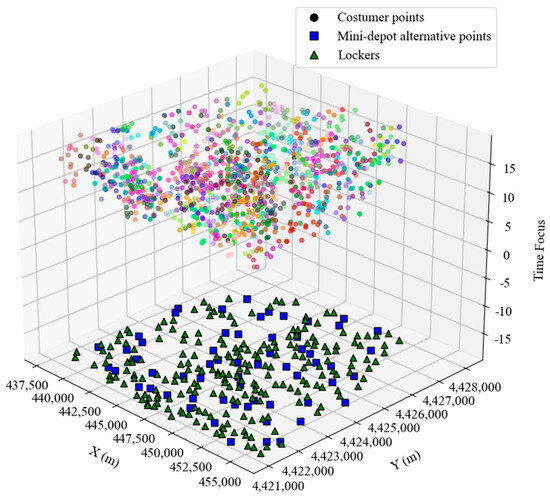

5.2. AP Clustering Selects the Location of Storage Lockers and Alternative Points

In this section, the AP clustering algorithm is used to obtain the alternative points of the mini warehouse and the location of the locker, and the damping factor λ is set to 0.7. Based on the clustering results of Scenario 1, as shown in Figure 9, 32 alternative mini-depot locations and 214 storage lockers are obtained. Based on the clustering results of Scenario 2, as shown in Figure 10, 68 alternative mini-depot locations and 279 storage lockers are obtained. Based on the clustering results of traditional site selection, as shown in Figure 11, 64 alternative mini-depot locations and 267 lockers are obtained.

Figure 9.

AP clustering results of scenario 1.

Figure 10.

AP clustering results of scenario 2.

Figure 11.

AP clustering results of traditional location selection.

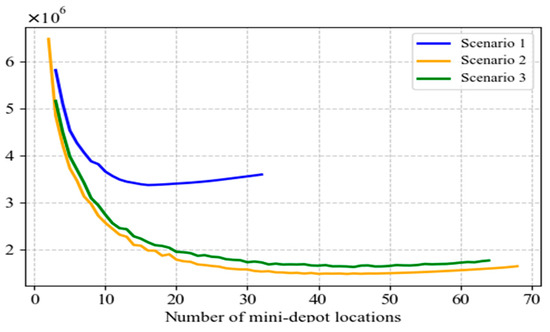

5.3. AHEEFO Solving Experimental Case

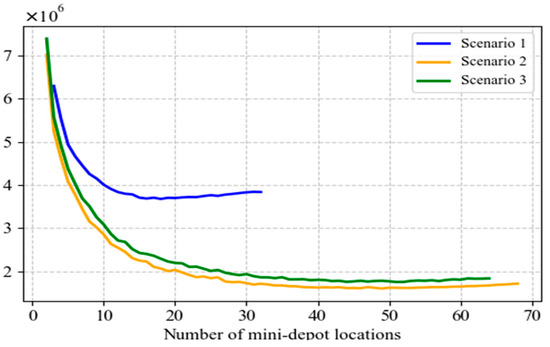

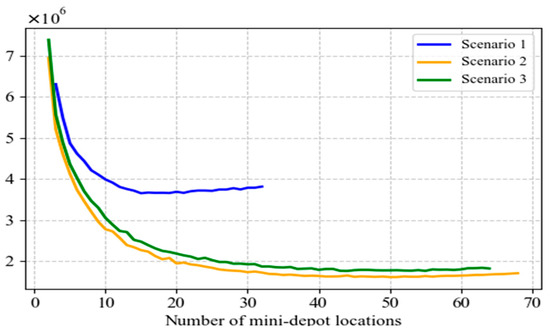

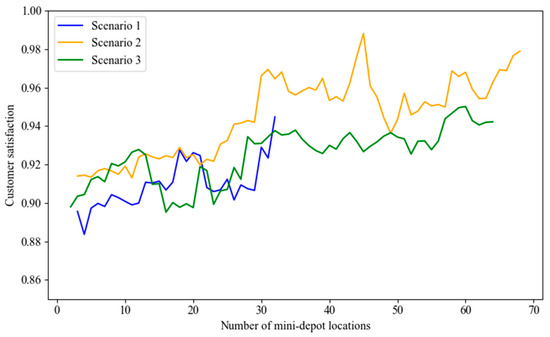

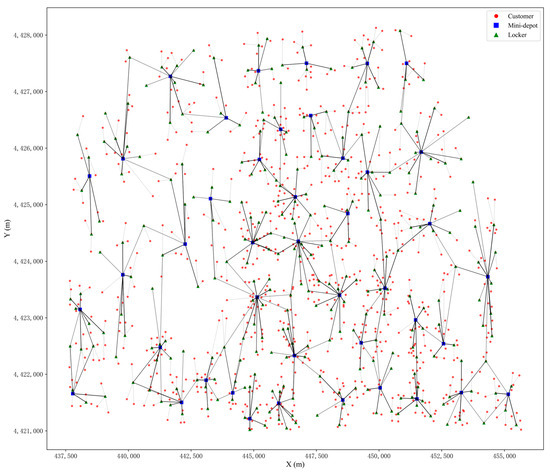

In this section, AHEEFO was applied to determine potential mini-depot locations under three different scenarios, thereby obtaining total cost and customer satisfaction results for varying numbers of mini-depots. As shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 regardless of random surges in demand, the location strategy in Scenario 2 outperformed both Scenario 1 and the traditional location strategy, achieving the lowest total cost and the highest customer satisfaction. The total cost under Scenario 1 was significantly higher than that of Scenario 2 and the traditional strategy. This was because Scenario 1 relied excessively on traditional delivery methods during peak order periods, leading to concentrated human and vehicle scheduling, increased operational pressure, and consequently higher operating costs. In contrast, Scenario 2 flexibly allocated tasks to crowd-sourced delivery resources, enabling elastic scheduling during peak periods and significantly reduced total costs. The traditional location strategy, on the other hand, made decisions solely based on geographic distribution, neglected the temporal characteristics of order demand, and consequently resulted in total costs that fell between those of Scenario 1 and Scenario 2. Figure 15 further illustrated that, within the service area of each mini-depot, a well-planned locker layout effectively addressed the efficiency shortcomings of traditional delivery in certain home delivery services, thereby improving the timeliness of order fulfillment and enhancing customer satisfaction. In the highly competitive “last mile” delivery segment of e-commerce, low cost and high service quality were key to gaining a competitive edge. Scenario 2, through its more efficient resource allocation mechanism, not only achieved a clear competitive advantage in both total cost and customer satisfaction but also provided e-commerce platforms with a sustainable delivery solution—maintaining controllable operating costs while meeting the need for rapid order fulfillment and offering customers a high-quality delivery experience. Table 6 presents the optimal location schemes under the three scenarios. After comprehensive comparison, Scenario 2 is identified as the global optimal location decision, and its corresponding global optimal result is illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 12.

The total cost comparison diagram under (, ) = (0.0, 1.0).

Figure 13.

The total cost comparison diagram under (, ) = (0.2, 1.5).

Figure 14.

The total cost comparison diagram under (, ) = (0.1, 2.0).

Figure 15.

Comparison chart of customer satisfaction under different site selection scenarios.

Table 6.

The optimal location results under different scenarios without random surge demand.

Figure 16.

The global optimal location result.

5.4. Algorithm Stability Experiment and Analysis

5.4.1. Stability Experiment and Analysis of AP Clustering

AP Clustering Validity and Stability Analysis

AP clustering under Scenario 2 outperformed Scenario 1 in all validity metrics: as shown in Table 7, it achieved a positive Silhouette coefficient, a low Davies–Bouldin index, and a high Calinski-Harabasz index, indicating compact and well-separated clusters. As shown in Table 8, stability analysis showed consistent cluster numbers and an ARI of 1 in both scenarios, demonstrating perfect reproducibility. Overall, Scenario 2 provided a more reliable clustering structure, making it a preferable input for Stage-2 optimization and enabling more accurate mini-depot and locker location decisions.

Table 7.

AP clustering validity index.

Table 8.

AP clustering stability Analysis.

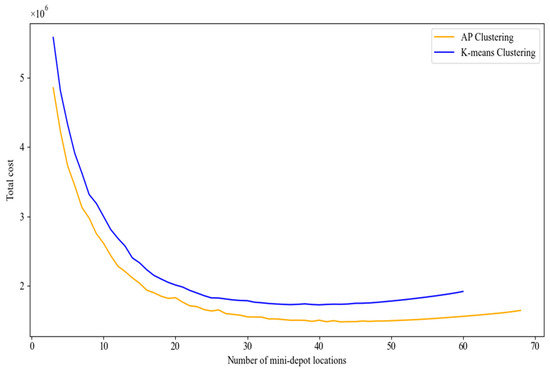

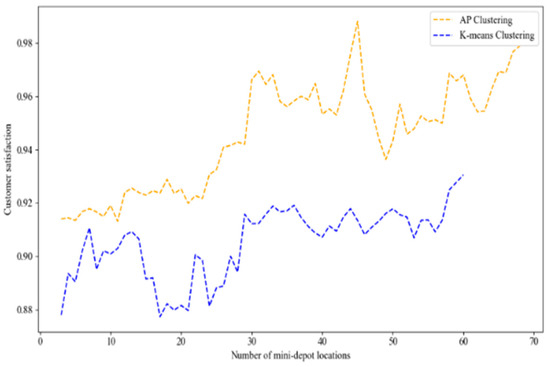

Comparison of the Effects of AP Clustering and K-Means Clustering on the Optimization Results Under Scenario 2

In this section, the number of candidate mini-depot locations was set to k1 = 60, and K-means clustering was used to determine the positions of the mini-depots and lockers (see Figure 17 and Figure 18). During the optimization stage, the initial points obtained from both K-means clustering and AP clustering were solved using AHEEFO, allowing for a comparison of the effects of the two clustering methods on the two-stage model. The results showed that, compared with K-means clustering, AP clustering not only reduced the final total cost by 13.57% but also achieved higher customer satisfaction, as shown in Figure 19 and Figure 20, demonstrating its overall superior performance.

Figure 17.

AP clustering results schematic diagram.

Figure 18.

K-means clustering results schematic diagram.

Figure 19.

Total cost comparison chart.

Figure 20.

Customer satisfaction comparison chart.

5.4.2. Stability Experiment and Analysis of AHEEFO

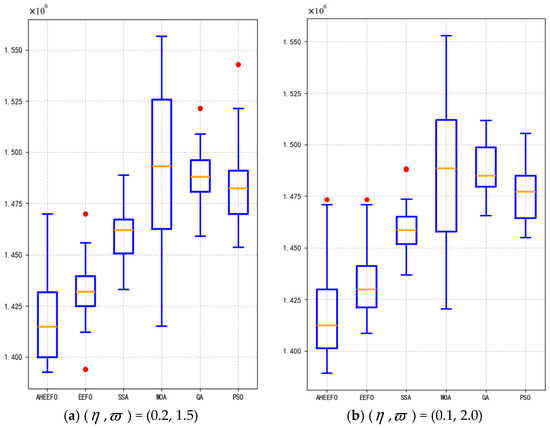

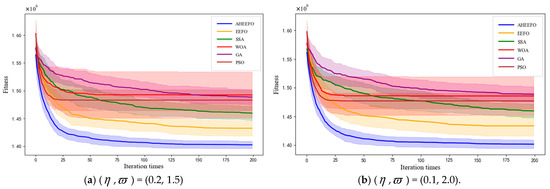

This section evaluates the stability of the model and algorithms by introducing random demand surges at customer points. To ensure a fair comparison, all algorithms were tested using their optimal hyperparameter configurations (obtained through hyperparameter optimization), as shown in Table 9. Each experiment was repeated 30 times independently, with results reported as mean ± standard deviation and statistical significance tests conducted. As shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22 and Table 10, under various random demand surge scenarios, AHEEFO consistently outperforms comparison algorithms, including EEFO, Sparrow Swarm Algorithm (SSA), Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), across multiple key performance metrics, demonstrating clear overall superiority. Specifically, it achieves the fastest convergence speed, rapidly stabilizing during the iteration process; it delivers the highest solution accuracy, with a strong ability to obtain optimal or near-optimal solutions; and it exhibits robust performance in repeated experiments, effectively adapting to demand surge uncertainties while maintaining stability. Meanwhile, paired-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted to analyze the significance between each pair of algorithms, with a significance level of = 0.05. In the test results, “★” indicates a significant difference between the compared algorithms, while “△” indicates no significant difference. As shown in Table 11, under both random demand surge scenarios, AHEEFO is significantly superior to all other algorithms, demonstrating a clear advantage. Additionally, in comparisons among the other algorithms, SSA outperforms PSO and EEFO in some cases, whereas no significant difference is observed between WOA and GA.

Table 9.

Hyperparameter Optimization Results of Algorithms.

Figure 21.

The comparison of the stability of 30 operations between AHEEFO and other algorithms.

Figure 22.

The convergence band of the algorithm under 30 runs is obtained.

Table 10.

The stability comparison results of the algorithm.

Table 11.

Statistical significance test results of different algorithms.

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis often provided comprehensive and effective decision-making suggestions for enterprise managers when they faced problems, which was a necessary step [62,63]. First, a global sensitivity analysis of α was conducted under Scenarios 1, 2, and 3 to validate the optimal value. The sensitivity analysis in Table 12 shows that when α = 20, feasible solutions are obtained across all scenarios, with the total cost remaining within a reasonable positive range and a balanced trade-off achieved between delivery cost and satisfaction-related cost. At this value, the total cost is relatively low (below 2.6 million in Scenarios 2 and 3), while the satisfaction cost remains around 1.2 million, indicating high service quality. In contrast, when α ≥ 50, the objective function becomes unbalanced: although the total cost increases, the satisfaction cost escalates sharply, leading to infeasible or impractical solutions. Therefore, α = 20 is the optimal value, ensuring a reasonable balance between cost control and customer satisfaction.

Table 12.

Sensitivity analysis results of Cost-satisfaction trade-off coefficient α.

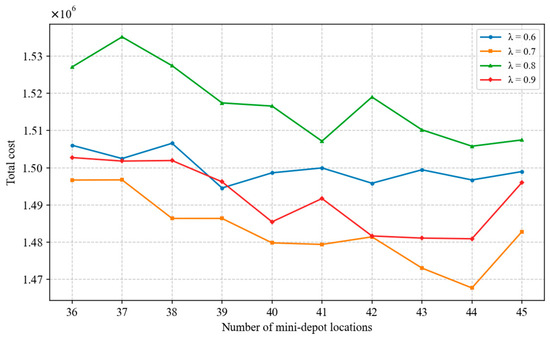

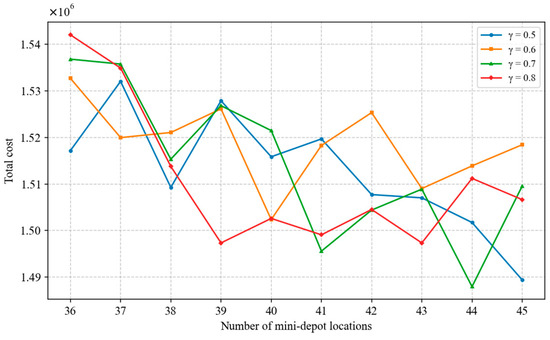

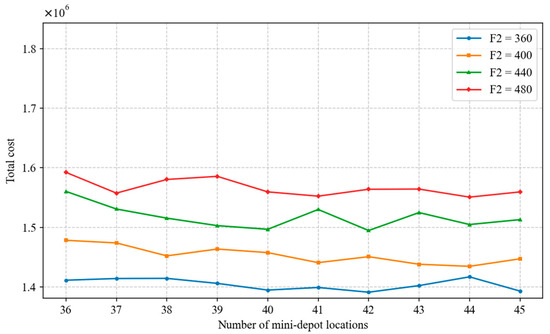

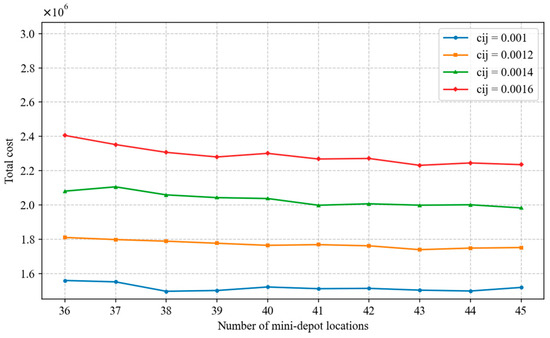

Subsequently, based on the optimal location decision identified in this study (Scenario 2 with 43 mini-depots), further sensitivity analysis was carried out on λ, γ, F2 and . The algorithm parameter λ and the operational parameter γ exhibit high sensitivity. As shown in Figure 23, the total cost varies nonlinearly with λ and reaches its lowest value when λ = 0.7, indicating that this setting is optimal under the studied scenario. Therefore, in AP clustering optimization, it is recommended to select λ = 0.7 and control the number of mini-depots within the range of 42–44 to achieve better siting performance. Meanwhile, Figure 24 shows that γ and the total cost follow an inverted U-shaped relationship, with the highest cost occurring at γ = 0.6 and the lowest at γ = 0.8. At γ = 0.8, the number of mini-depots is concentrated between 43 and 45, suggesting that variations in γ significantly affect siting performance and thus require particular attention. In contrast, the operational parameters F2 and the transportation cost coefficient are relatively stable. As indicated in Figure 25, although increases in F2 cause some fluctuations in the optimal number of mini-depots, F2 = 400 represents a reasonable investment level. Furthermore, Figure 26 shows that changes in have limited impact on the final siting decisions, implying that decision-makers can flexibly adjust to actual logistics and delivery prices in the e-commerce context without concern for substantial disruption of the overall siting scheme.

Figure 23.

Parameter λ sensitivity analysis line chart.

Figure 24.

Parameter γ sensitivity analysis line chart.

Figure 25.

Parameter F2 sensitivity analysis line chart.

Figure 26.

Parameter sensitivity analysis line chart.

6. Conclusions

With the rapid development of e-commerce, customer expectations for delivery timeliness have been continuously increasing [23]. As a critical component of e-commerce logistics, “last mile” delivery needs to achieve an effective balance among speed, low cost [24], and high customer satisfaction [20]. This paper proposes a two-stage location model for mini-depots and lockers, considering spatiotemporal customer demand. In the first stage, AP clustering is used to identify candidate mini-depot locations and locker layouts based on temporal and spatial demand characteristics. In the second stage, AHEEFO determines the optimal mini-depot location strategy to minimize total cost.

The study is conducted using the latitude and longitude coordinates of 1157 customer points in several districts of Beijing, China, along with a dataset of parcel demand over a single day. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Regardless of random surges in demand, the location strategy under Scenario 2 outperforms Scenario 1 and traditional location methods, achieving the lowest total cost and the highest customer satisfaction. This is because the dispersed temporal demand distribution allows crowd-sourced delivery to fully leverage its flexibility and cost advantages. By implementing elastic scheduling during peak periods and reasonably configuring lockers within service areas to share peak demand and shorten delivery distances, operational pressure is effectively alleviated while enhancing the customer experience. In contrast, Scenario 1’s concentrated demand pattern requires more professional courier resources during peak hours, leading to higher costs and limited efficiency.

- (2)

- The two-stage location model helps identify under which demand distribution scenarios crowd-sourced delivery is more appropriate than fixed-route delivery and provides decision support for the optimal configuration of lockers to relieve peak-period pressure. Policymakers can also draw on these findings to design more flexible incentive mechanisms for crowd-sourced riders or provide urban infrastructure support to optimize locker networks. Overall, the model integrates crowd-sourced delivery with locker deployment, providing e-commerce platforms with a sustainable “last mile” solution that balances cost control and high-quality service.

- (3)

- The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm is verified through experimental cases. The results show that the model exhibits strong robustness under different random demand surges, with stable total cost and customer satisfaction. AP clustering demonstrates high compactness and separation, and maintains consistent clustering numbers and ARI values, indicating high reproducibility and providing more reliable input for subsequent location optimization. Compared with K-means, AP clustering reduces costs by 13.57% at the clustering stage. AHEEFO outperforms EEFO, SSA, WOA, GA, and PSO in terms of solution quality, computational efficiency, and stability.

- (4)

- The sensitivity analysis in this study indicates that when α = 20, the model achieves a good balance among facility location costs, delivery costs, and customer satisfaction. The algorithm parameter λ and operational parameter γ are the most sensitive factors affecting the location outcomes, whereas F2 and remain relatively stable. During the clustering stage for selecting candidate mini-depot sites and locker locations, setting λ to 0.7 helps achieve optimal location decisions, resulting in lower total costs. γ reflects customers’ sensitivity to delivery timeliness; therefore, firms should prioritize improving delivery performance through intelligent scheduling systems, rider route optimization, and instant delivery modes to reduce timeliness costs and enhance customer satisfaction. The analysis of F2 suggests that a moderate investment level (e.g., 400 yuan per month) is preferable, and firms should configure lockers considering both market rents and demand density. The stability of indicates that the overall layout remains robust even under fluctuations in fuel prices, electric vehicle electricity costs, or crowdsourcing commissions, providing firms with considerable flexibility in pricing changes. Overall, decision-makers should focus on the proper setting of λ and γ, while maintaining flexibility in investment and transportation cost management to address the dynamic demands of the e-commerce logistics industry.

However, there are still several aspects that require improvement in this study, such as the reliance of mini-depot delivery tasks on sufficient depot capacity, the potential inaccuracy of customer temporal demand distributions, and the fact that the current delivery route optimization focuses on macroscopic planning rather than precisely solving the Location-Routing Problem (LRP). These issues will be addressed in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B. and F.L.; methodology, H.Y.; software, H.Y.; validation, H.B. and F.L.; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, H.Y.; re-sources, H.Y.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.Y.; visualization, H.Y.; supervision, H.B. and F.L.; project administration, F.L.; funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China under grant number 2020YFB1712802, the Science and Technology Research and Development Plan Project of Qinhuangdao under grant no. 202401A143.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to data protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the editor and the reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sakai, T.; Santo, K.; Tanaka, S.; Hyodo, T. Locations of logistics facilities for e-commerce: A case of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 56, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz, A. The logistics dualization in question: Evidence from the Paris metropolitan area. Cities 2021, 119, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, K.; Thompson, R.G. Impacts of logistics sprawl on the urban environment and logistics: Taxonomy and review of literature. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 57, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Shen, J.; Wu, X.; Luo, J. Logistics Space: A Literature Review from the Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Xie, K.; Xiao, W.; Bai, C. Toward a low carbon path: Do E-commerce reduce CO2 emissions? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Does e-commerce development drive regional entrepreneurial activity? Spatial spillover effect and mechanism analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 284, 109611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Cardenas, I.; Sanchez-Diaz, I. Managing household freight: The impact of online shopping on residential freight trips. Transp. Policy 2022, 125, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. Relative logistics sprawl: Measuring changes in the relative distribution from warehouses to logistics businesses and the general population. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 83, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, J.K. Creating the Discourse of Marginalized Limbu Community: A Foucauldian Analysis of Manglak’s Limbuni Gaaun [The Village of Limbu Woman]. JODEM J. Lang. Lit. 2022, 13, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaller, M.; Otero-Palencia, C.; Pahwa, A. Automation, electrification, and shared mobility in urban freight: Opportunities and challenges. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 46, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steins, J.J.; Ruck, M.; Volk, R.; Schultmann, F. Optimal design of a post-demolition autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) recycling network using a capacitated, multi-period, and multi-stage warehouse location problem. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahparvari, S.; Nasirian, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Noori, S.; Chhetri, P. A GIS-LP integrated approach for the logistics hub location problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Jiang, R.; Bi, H.; Gao, Z. Order Distribution and Routing Optimization for Takeout Delivery under Drone–Rider Joint Delivery Mode. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 774–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gou, M.; Luo, S.; Fan, J.; Wang, H. The multi-depot pickup and delivery vehicle routing problem with time windows and dynamic demands. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, N.; Niaki, S.T.A.; Hussenzadek Kashan, A.; Seifbarghy, M. An efficient solution method for an agri-fresh food supply chain: Hybridization of Lagrangian relaxation and genetic algorithm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalimoghadam, M.; Thompson, R.G.; Rajabifard, A. Determining the number and location of micro-consolidation centres as a solution to growing e-commerce demand. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 117, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, L.; Grygorak, M.; Polishchuk, V.; Vovk, Y.; Lyashuk, O.; Vovk, I.; Khudobei, R. Complex Evaluation of the Efficiency of Urban Consolidation Centers at the Micro Level. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2022, 115, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Isaza, S.; Fontaine, P.; Minner, S. The value of stochastic crowd resources and strategic location of mini-depots for last-mile delivery: A Benders decomposition approach. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2022, 157, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Gu, Y.; Lu, F.; Mahreen, S. Site selection of electric vehicle charging station expansion based on GIS-FAHP-MABAC. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 507, 145557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, T.; Goh, M.; Choi, T. Home delivery vs. out-of-home delivery: Syncretic value-based strategies for urban last-mile e-commerce logistics. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 193, 104309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, S.; Ye, Z.; Xia, S. The optimisation of the location of front distribution centre: A spatio-temporal joint perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 263, 108950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, H.; Zhang, J.; Mirjalili, S.; Khodadadi, N.; Cao, Q. Electric eel foraging optimization: A new bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, L.; Max Shen, Z. On-time last-mile delivery: Order assignment with travel-time predictors. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 4095–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gdowska, K.; Viana, A.; Pedroso, J.P. Stochastic last-mile delivery with crowdshipping. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 30, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Fang, X.; Lim, Y.F. Urban Consolidation Center or Peer-to-Peer Platform? The Solution to Urban Last-Mile Delivery. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, K.; Bodur, M.; Roorda, M.J. Stochastic last-mile delivery with crowd-shipping and mobile depots. Transp. Sci. 2022, 56, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrahmani, E.; Jaller, M. Crowdshipping in last mile deliveries: Operational challenges and research opportunities. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 78, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Du, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Towards enhancing the crowdsourcing door-to-door delivery: An effective model in Beijing. J. Ind. Manag. Optim 2025, 21, 2371–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhuo, H.; Lai, X. The pickup and delivery problem with multiple depots and dynamic occasional drivers in crowdshipping delivery. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, R.J.; Kourounioti, I.; Thoen, S.; de Bok, M.; Tavasszy, L. A disaggregate model of passenger-freight matching in crowdshipping services. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 169, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamzinshuti, A.; Cardoso, F.; Janjevic, M.; Ndiaye, A.B. Pharmaceutical distribution in urban area: An integrated analysis and perspective of the case of Brussels-Capital Region (BRC). Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.K.; Oliveira, I.K.; Nascimento, C.D.O.L.; Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V. Mobility as a service for freight and passenger transport: Identifying a microhubs network to promote crowdshipping service. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 19, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; He, D.; Lee, L.H. Last-mile delivery: Optimal locker location under multinomial logit choice model. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 142, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, Y.; Golany, B. A parcel locker network as a solution to the logistics last mile problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faugère, L.; Montreuil, B. Smart locker bank design optimization for urban omnichannel logistics: Assessing monolithic vs. modular configurations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, H.; Zhang, L.; Tsai, P.; Woo, J. Crowdsourced last-mile delivery with parcel lockers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 251, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, T. The service points’ location and capacity problem. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 176, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Qin, H. Joint optimization of parcel allocation and crowd routing for crowdsourced last-mile delivery. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2023, 171, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysen, N.; de Koster, R.; Weidinger, F. Warehousing in the e-commerce era: A survey. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 277, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, Y.; Sun, X. New paradigm of logistics space reorganization: E-commerce, land use, and supply chain management. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozzi, R.; Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V. Urban logistics facilities and storytelling. Stakeholder engagement, participatory policy-planning and co-creation. Transp. Plan. Technol 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, M.; Tadić, S.; Krstić, M.; Bouraima, M.B. Novel Spherical Fuzzy MARCOS Method for Assessment of Drone-Based City Logistics Concepts. Complexity 2021, 2021, 2374955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.; Nsamzinshuti, A.; Bonsu, S.; Ndiaye, A.B.; Rigo, N. Localization of relevant urban micro-consolidation centers for last-mile cargo bike delivery based on real demand data and city characteristics. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta Prieto, M.; Ismael, A.; Rivera Gonzalez, C.; Mitchell, J.E. Location of urban micro-consolidation centers to reduce the social cost of last-mile deliveries of cargo: A heuristic approach. Networks 2022, 79, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, S.; Krstić, M.; Kovač, M.; Brnjac, N. Evaluation of smart city logistics solutions. Promet-TrafficTransportation 2022, 34, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdekhasti, A.; Ma, J. A two-echelon two-indenture warranty distribution network development and optimization under batch-ordering inventory policy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 249, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, Y. A three-stage geospatial network optimal location decision model for urban green logistics centers from a sustainable perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 128, 106481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Zack, J. Insights on strategic air taxi network infrastructure locations using an iterative constrained clustering approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 128, 470–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Baina, H.; Jingru, Z.; Chenxu, L.; Zuyuan, L.; Weihan, D.; Ye, L.; Moqian, W. Location and sizing of distributed energy storage in distribution substations under multiple scenarios based on improved affinity propagation clustering. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, P.; Lv, Y.; Fan, H. Time-dependent multi-depot green vehicle routing problem with time windows considering temporal-spatial distance. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 129, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilnejad, S.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Optimal charging station locations and durations for a transit route with battery-electric buses: A two-stage stochastic programming approach with consideration of weather conditions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 156, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghalari, A.; Salamah, D.; Kabli, M.; Marufuzzaman, M. A two-stage stochastic location–routing problem for electric vehicles fast charging. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 158, 106286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.D.O.L.; Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E. Green Crowdshipping: Critical factors from a business perspective. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 51, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R.; Gabrielli, L.; Monreale, A.; Pedreschi, D.; Giannotti, F. Discovering temporal regularities in retail customers’ shopping behavior. EPJ Data Sci. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Geunes, J.; Nie, X. Revisiting Continuous p-Hub Location Problems with the L1 Metric. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.08439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimberg, J.; Hansen, P.; Mladenović, N.; Taillard, E.D. Improvements and comparison of heuristics for solving the uncapacitated multisource Weber problem. Oper. Res. 2000, 48, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, R.Z.; SteadieSeifi, M.; Asgari, N. Multiple criteria facility location problems: A survey. Appl. Math. Model. 2010, 34, 1689–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, M.; Hao, C. Time-satisfaction-based maximal covering location problem. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2006, 14, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, R.; Bi, H. Routing Optimization of Takeout Delivery Routes Under Joint Delivery Model of Drones, Occasional Drivers, and Riders. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lee, L.H.; Chew, E.P. Profit-maximizing parcel locker location problem under threshold Luce model. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 157, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Escribano-Macias, J.; Feng, Y.; Candela, E.; Angeloudis, P. Route planning for last-mile deliveries using mobile parcel lockers: A hybrid q-learning network approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 177, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Meng, F.; Bi, H. Scenario deduction of explosion accident based on fuzzy dynamic Bayesian network. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 96, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Gao, Z.; Bi, H. Bi-objective green vehicle routing problem with heterogeneous regular vehicles and occasional drivers joint delivery. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2025, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).