Abstract

Industrial workplaces expose workers to a high risk of injuries such as Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs). Exoskeletons are wearable robotic technologies that can be used to reduce the loads exerted on the body’s joints and reduce the occurrence of WMSDs. However, current studies show that the deployment of industrial exoskeletons is still limited, and widespread adoption depends on different factors, including efficacy evaluation metrics, target tasks, and supported body postures. Given that exoskeletons are not yet adopted to their full potential, we propose a review based on these three evaluation dimensions that guides researchers and practitioners in properly evaluating and selecting exoskeletons and using them effectively in workplaces. Specifically, evaluating an exoskeleton needs to incorporate: (1) efficacy evaluation metrics based on both subjective (e.g., user perception) and objective (e.g., physiological measurements from sensors) measures, (2) target tasks (e.g., manual material handling and the use of tools), and (3) the body postures adopted (e.g., squatting and stooping). This framework is meant to guide the implementation and assessment of exoskeletons and provide recommendations addressing potential challenges in the adoption of industrial exoskeletons. The ultimate goal is to use the framework to enhance the acceptance and adoption of exoskeletons and to minimize future WMSDs in industrial workplaces.

1. Introduction

Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs) represent the leading type of occupational injuries in many countries. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that WMSDs contributed to 26.1% of workplace incidents, which represented 266,530 days away from work for cases in 2019 [1]. Similarly, the economic burden of WMSDs in Canada is estimated to be 22 billion dollars annually [2]. With the introduction of exoskeletons to industrial workplaces, there has been a rising interest in the adoption of exoskeletons to reduce exposure to WMSDs and increase productivity [3,4].

The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) defines an exoskeleton as “a wearable device that augments, enables, assists, and/or enhances physical activity through mechanical interaction with the body [5]”. The applications of exoskeletons are diverse; as body-worn devices, they can support a worker’s body and prevent injuries and improve performance by reducing physical demands. Although exoskeletons are being developed and used increasingly for industrial applications, the technology was previously adopted mostly for military and rehabilitation purposes [6]. It is expected that the total value of the exoskeleton market will reach $1.8 billion in 2025, an increase from $68 million in 2014 [7], which implies a high growth in the adoption of exoskeletons throughout different industries.

Although different industries have started exploring the adoption of exoskeletons as part of their operations, and some have already integrated exoskeletons into their workplace [8], the wide-scale adoption of industrial exoskeletons is still limited due to the unique challenges involved, especially related to evaluating their effectiveness for different applications. Although different studies have investigated the suitability of industrial exoskeletons using a variety of experiments and measurements, there is still limited information available regarding the impact of exoskeletons on different factors such as safety, productivity, and comfort, especially in the long term.

While several systematic reviews have been conducted in regard to the impacts of industrial exoskeletons, most studies have mainly focused on evaluation metrics (e.g., EMG, user satisfaction, and discomfort) to assess the effectiveness of a specific exoskeleton. However, it is important to also incorporate other parameters that can significantly impact the findings. In particular, the body postures adopted and the target tasks should be incorporated into the analysis in addition to the efficacy evaluation metrics. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to provide a systematic review of previous studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of industrial exoskeletons from the perspective of evaluation metrics, supported body postures, and target tasks.

2. Methods

The systematic review is implemented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) [9].

2.1. Literature Search

Search criteria were set up to identify published literature that evaluated passive exoskeletons for industrial applications. Different keywords used synonymously with exoskeletons (i.e., exosuits and wearable robots) were included in the search, and the search included exoskeletons developed to support different body parts and was not limited to a specific body part. Furthermore, keywords such as “occupational”, “work”, and “industrial” were used to highlight studies that have focused on exoskeletons that are developed for occupational applications. The defined keywords were used to search the databases using Boolean “AND” and “OR” operators. Filters were also applied to restrict the findings to those that were published between 1990 and 2021 and in English. The search criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search criteria for the systematic review.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

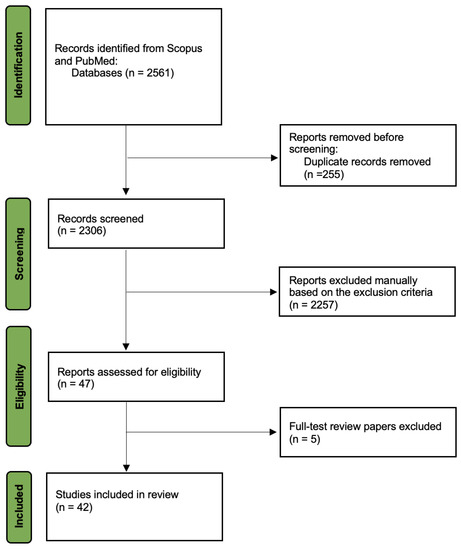

In July 2021, the Scopus and PubMed online databases were searched to implement the systematic review. The search method described above resulted in 2561 initial studies. The studies were first filtered to remove duplicates based on their unique Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs). There were 255 duplicates found in the two databases. The remaining 2306 studies were then screened and filtered by applying the exclusion criteria to limit the studies to passive and industrial exoskeletons. Table 2 shows the exclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Exclusion criteria for literature review.

The 2306 studies were manually screened based on their titles, abstracts, and keywords using the exclusion criteria. This process resulted in 47 studies. Among the 47 identified studies, 5 studies were systematic review papers and hence were removed. Therefore, 42 studies were identified for the systematic review. The PRISMA flowchart shown in Figure 1 demonstrates the systematic review process adopted. These 42 identified studies focused on the evaluation of industrial exoskeletons through experimentation and the use of evaluation metrics. The 42 studies were reviewed and analyzed to highlight and compare their evaluation metrics.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review (adopted from [9]).

2.3. Data Analysis

The identified studies were thoroughly reviewed to identify the experiment setup, the evaluation features, and the experimental findings. The experiment setup includes the type of exoskeleton, the variables of the study, the demographics of the participants, and the experiment design. Evaluation features include the evaluation metrics (objective and subjective), the supported body postures, and the target tasks. Experimental findings include the findings of the studies and the benefits and/or drawbacks of the proposed methods.

3. Results

All studies in the review adopted at least one of the three evaluation features (i.e., evaluation metrics, body postures, and target tasks) to assess exoskeletons. The reviewed studies, along with their study method, evaluation approach, and the findings are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Findings of reviewed studies on evaluation of exoskeletons.

3.1. Exoskeleton Types

From the 42 studies identified, 40 assessed commercial exoskeletons. The brand, name, purpose, and number of papers that evaluated each exoskeleton are shown in Table 4. SuitX and Laveo were the most evaluated brands, with 12 studies evaluating Laveo exoskeletons and 10 evaluating SuitX. In addition, the exoskeleton that was evaluated the most was Laveo’s back support (12 studies). Out of the 42 studies, four studies either designed their own exoskeleton or did not mention the name of the exoskeleton evaluated.

Table 4.

Exoskeletons evaluated in the identified studies.

3.2. Efficacy Evaluation Metrics

Evaluation metrics are categorized as objective and subjective metrics. Objective metrics are measured using experimental equipment (e.g., surface electrodes and motion sensors). Subjective metrics reflect a user’s perception and feedback in regard to the exoskeleton. Table 5 summarizes the evaluation metrics typically adopted to evaluate exoskeletons.

Table 5.

Most common evaluation metrics adopted in evaluating exoskeletons.

Out of the 42 studies in the systematic review, 26 used some form of subjective response, mainly including RPE and discomfort surveys. In terms of objective metrics, 33 studies used EMGS, 18 used motion capture, 8 used force plates, 8 evaluated heart rates, 7 evaluated the oxygen consumption and metabolic cost, 3 evaluated performance, 1 evaluated the range of motion, 1 evaluated hand grip to measure fatigue, and 1 evaluated the vibration of the shoulders.

It is important to note that focusing only on efficacy evaluation metrics might not result in an inclusive analysis; as a result, similar studies can result in different findings in terms of the outcomes of the experiments. For example, Baltrusch et al. [48] used a variety of evaluation metrics such as EMG, motion capture, subjective responses, and oxygen consumption, and reported that the Laevo exoskeleton has a generally positive usability rating. In addition, Madinei et al. [30] used a similar methodology to Baltrusch et al. [48] and reported that using the Laveo exoskeleton made lifting and bending tasks easier and more efficient. However, Luger et al. [21] reported low wearability for the Laevo exoskeleton and Bosch et al. [51], using similar metrics, reported that Laveo led to discomfort in the chest region for static tasks. When evaluating the ShoulderX, a shoulder-supported exoskeleton, Van Engelhoven et al. [35] used EMG measurements and reported that the participants’ shoulder flexor muscle activity was reduced by up to 80%. However, De Bock et al. [42] reported that participants provided high discomfort scores in the shoulder region, and the usability was moderate. Thus, focusing only on efficacy evaluation metrics and not considering other evaluation features cannot provide a comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of an exoskeleton.

3.3. Body Posture

The body posture feature reflects the required body position of the participants when performing the experiment tasks. The body posture adopted during the experiments is an important feature because it has a direct relationship with the impact of the exoskeleton on different body parts [52]. The most common body postures in the reviewed studies include pushing, pulling, twisting, sitting, standing, kneeling, bending, and squatting. Similar to efficacy evaluation metrics, the impact of different postures has to be investigated in conjunction with other evaluation features. Otherwise, the outcomes of the analysis might not properly reflect the suitability of the exoskeleton for different activities; studies that do not consider posture or that focus only on one posture can provide only limited information about the effectiveness of an exoskeleton.

For example, Wei et al. [50] studied lifting using the stoop posture and reported 35–61% lower muscle activity and a 22% lower metabolic cost when using the Mebot-EXO. Bosch et al. [51] also studied lifting using the stoop posture and indicated 35–38% lower back muscle activity and lower discomfort in the low back when using the Leavo exoskeleton. Although the findings of such studies provide valuable information about the impact of an exoskeleton on a specific posture, they lack further information about the comparison of different lifting postures and ignore the impact of the task on the selected posture and the effectiveness of the exoskeleton. Furthermore, Simon et al. [13] and Frost et al. [14] compared stoop, squat, and freestyle postures using EMG and motion capture data with VT-Lowe’s Exosuit and the PLAD exoskeleton, respectively. Simon et al. [13] reported that the results obtained from EMG and motion capture measurements for freestyle posture style were not significantly different from those for the squat posture style. Frost et al. [14] compared the same postures with the PLAD exoskeleton and showed that there was a significant reduction in erector spinae and L4/L5 flexion. While these studies provide more information on the role of different postures on the effectiveness of exoskeletons, incorporating further evaluation metrics as well as target tasks into the analysis can improve the applicability and generalizability of the findings.

3.4. Target Tasks

The target task evaluation feature represents the activity that the exoskeleton is used for. This feature is considered an important variable because defining the task enables evaluating the different postures and techniques that can be adopted to complete the task. All 42 studies evaluated at least one independent task. Out of the reviewed studies, 18 adopted manual handling tasks, 8 evaluated static tasks, and 17 selected tasks that required using tools (e.g., screwing, clip fitting, and drilling). Furthermore, 5 studies included tasks that required the participant to walk, 2 studies required the participant to climb, and 2 studies asked participants to perform experiments that involve balance (e.g., unipedal vs. bipedal stance). However, even when the same tasks are evaluated, the findings can vary due to other features such as the posture used to complete the task. Furthermore, the results of the analysis might differ when evaluating the same posture but for different tasks. For example, when evaluating a stoop posture, it is critical whether the task consists of dynamic stooping or squat lifting, as it impacts the results of the analysis.

3.5. Integration of Evaluation Features

Table 6 summarizes the evaluation metrics, postures, and tasks that each of the 42 reviewed studies adopted. Although most studies did not design experiments specifically to evaluate various tasks and postures using evaluation metrics, any experiment intending to assess the impact of exoskeletons requires, at a minimum, defining the task to be carried, either using a freestyle posture or a predetermined posture.

Table 6.

Exoskeletons evaluated in the identified studies.

To properly evaluate exoskeletons, it is critical to incorporate all three dimensions into the analysis: efficacy evaluation metrics, supported body postures, and target tasks. If all dimensions are not properly incorporated, the impact of one feature (e.g., posture) on another (e.g., muscle activity) cannot be established thoroughly. For example, Baltrusch et al. [47] considered all three dimensions: evaluation metrics (muscle activity and metabolic consumption), supported body postures (upright postures), and target tasks (lifting a box) in their experiments, and reported that the metabolic consumption was higher in squatting compared to stooping. Furthermore, the authors reported that the participants felt more discomfort when carrying out the task in a squat posture versus a stooping posture. On the other hand, another study [48] used only two dimensions: evaluation metrics (subjective response and metabolic consumption) and target tasks (lifting a box). While this study specified a bending angle (between 0–20 degrees or greater than 20 degrees) in the lifting task, it did not specify the participants’ lifting postures. As a result, the findings only implied a decrease in metabolic costs when using the exoskeleton.

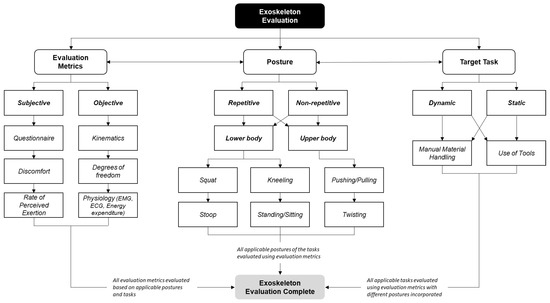

The review of previous studies indicates the importance of incorporating all three evaluation dimensions, including evaluation metrics, body posture, and target task when assessing exoskeletons to enable a practical and accurate analysis. The framework shown in Figure 2 is proposed to guide the proper evaluation of exoskeletons based on the three dimensions discussed. The proposed framework outlines the three evaluation dimensions that need to be investigated simultaneously. Efficacy evaluation metrics include both subjective and objective measurements, which are commonly considered in most of the previous studies. Subjective evaluations reflect participant responses (e.g., RPE, discomfort, and effectiveness) while carrying out a task with and without the exoskeleton. Objective evaluations include physiology (e.g., EMG) and kinematics (e.g., motion capture systems) and use measurements typically obtained through sensors to provide objective data. In addition to efficacy evaluation metrics, the different postures that can be adopted must be considered as part of experiment design, including repetitive and non-repetitive motions. In addition, the target task, reflecting the specific task and its dynamic or static nature (e.g., stationary standing vs. walking) needs to be incorporated into the experiment design, data collection, and analysis.

Figure 2.

Framework for exoskeleton evaluation.

The three-dimensional iterative approach provides a thorough analysis of the physical, physiological, and postural impacts of using an exoskeleton. While this approach is more desirable for the evaluation of exoskeletons because it covers multiple aspects, it can also be more time-consuming and costly as compared to evaluation based on one or two dimensions. The intended outcome of the study is an important factor when deciding on which features to evaluate. For example, many of the reviewed studies incorporated two dimensions (e.g., EMG and a manual handling task) and were mostly interested in assessing a specific result (e.g., muscle activity). While these studies provide valuable insight on a specific outcome, they lack the comprehensiveness to provide findings that can guide the long-term implementation of the exoskeletons, especially for industrial adoption. As a result, a practical approach is to start the evaluation with one or two dimensions and add more features throughout the experiments to reflect on all three dimensions as more data are collected.

4. Conclusions

This study presented a systematic review of previous studies evaluating industrial exoskeletons. The reviewed studies adopted various evaluation features and reported findings dependent on different factors such as the exoskeleton features, the evaluation metrics, the posture used, and the task evaluated. The findings of the review highlighted that the state-of-the-art exoskeleton evaluation methods often consider one or two evaluation dimensions independently without further cross-validation. As the assessment of exoskeletons requires the integration of various factors, an evaluation framework is proposed that suggests a three-dimensional iterative evaluation approach to evaluate and adopt exoskeletons for industrial use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and M.T.; methodology, A.G., A.C. and M.T.; formal analysis, A.G., A.C. and M.T.; investigation, A.G., A.C. and M.T.; resources, A.G. and M.T.; writing, A.G., A.C. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) grant number LOF 28241 and JELF 35916, the Government of Alberta grant number IAE RCP-12-021 and EDT RCP-17-019-SEG, and the Government of Alberta’s grant to Centre for Autonomous Systems in Strengthening Future Communities (RCP-19-001-MIF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Data. 2021. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/soii-data.htm#archive (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Workers Health and Safety Center (WHSC). The Economics of Ergonomics. 2016. Available online: https://www.whsc.on.ca/Files/Resources/Ergonomic-Resources/RSI-Day-2016_MSD-Case-Study_The-economics-of-ergon.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Bogue, R. Exoskeletons—A Review of Industrial Applications. Ind. Robot Int. J. 2018, 45, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N.; Prokop, G.; Weidner, R. Methodologies for evaluating exoskeletons with industrial applications. Ergonomics 2021, 65, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM F3323-20; Standard Terminology for Exoskeletons and Exosuits. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Pesenti, M.; Antonietti, A.; Gandolla, M.; Pedrocchi, A. Towards a functional performance validation standard for industrial low-back exoskeletons: State of the art review. Sensors 2021, 21, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ABI Research. Exoskeleton Market to Reach $1.8B in 2025. 2015. Available online: https://www.abiresearch.com/press/abi-research-predicts-robotic-exoskeleton-market-e/ (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Marinov, B. Toyota’s Woodstock Plant Makes the Levitate AIRFRAME Exoskeleton Mandatory Personal Protective Equipment. 2019. Available online: https://exoskeletonreport.com/2019/02/toyotas-woodstock-plant-makes-the-levitate-airframe-exoskeleton-mandatory-personal-protective-equipment/ (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdoli, M.-E.; Agnew, M.J.; Stevenson, J.M. An on-body personal lift augmentation device (PLAD) reduces EMG amplitude of erector spinae during lifting tasks. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemi, M.M.; Geissinger, J.; Simon, A.A.; Chang, S.E.; Asbeck, A.T. A passive exoskeleton reduces peak and mean EMG during symmetric and asymmetric lifting. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2019, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, A.S.; Näf, M.; Baltrusch, S.J.; Kingma, I.; Rodriguez-Guerrero, C.; Babič, J.; de Looze, M.P.; van Dieën, J.H. Biomechanical evaluation of a new passive back support exoskeleton. J. Biomech. 2020, 105, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.A.; Alemi, M.M.; Asbeck, A.T. Kinematic effects of a passive lift assistive exoskeleton. J. Biomech. 2021, 120, 110317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Abdoli, M.-E.; Stevenson, J.M. PLAD (personal lift assistive device) stiffness affects the lumbar flexion/extension moment and the posterior chain EMG during symmetrical lifting tasks. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, e403–e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, T.; Bär, M.; Seibt, R.; Rieger, M.A.; Steinhilber, B. Using a back exoskeleton during industrial and functional tasks—Effects on muscle activity, posture, performance, usability, and wearer discomfort in a laboratory trial. Hum. Fact. 2021, 00187208211007267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Li, H.; Anwer, S.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Mi, H.Y.; Wuni, I.Y. Assessment of a passive exoskeleton system on spinal biomechanics and subjective responses during manual repetitive handling tasks among construction workers. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Srinivasan, D. Effects of two passive back-support exoskeletons on postural balance during quiet stance and functional limits of stability. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2021, 57, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picchiotti, M.T.; Weston, E.B.; Knapik, G.G.; Dufour, J.S.; Marras, W.S. Impact of two postural assist exoskeletons on biomechanical loading of the lumbar spine. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinc, Ž.; Baltrusch, S.; Houdijk, H.; Šarabon, N. Short-term effects of a passive spinal exoskeleton on functional performance, discomfort and user satisfaction in patients with low back pain. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2021, 31, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, A.W.; Krause, F.; de Looze, M.P. The effectivity of a passive arm support exoskeleton in reducing muscle activation and perceived exertion during plastering activities. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luger, T.; Bär, M.; Seibt, R.; Rimmele, P.; Rieger, M.A.; Steinhilber, B. A passive back exoskeleton supporting symmetric and asymmetric lifting in stoop and squat posture reduces trunk and hip extensor muscle activity and adjusts body posture—A laboratory study. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 97, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, J.P.; Taira, C.; Parik-Americano, P.; Suplino, L.O.; Bartholomeu, V.P.; Hartmann, V.N.; Umemura, G.S.; Forner-Cordero, A. A comparison between three commercially available exoskeletons in the automotive industry: An electromyographic pilot study. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), New York, NY, USA, 29 November–1 December 2020; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, X. A Quantifiable Muscle Fatigue Method Based on sEMG during Dynamic Contractions for Lower Limb Exoskeleton. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Real-Time Computing and Robotics (RCAR), Online, 28–29 September 2020; pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Esfahani, M.I.M.; Alemi, M.M.; Alabdulkarim, S.; Rashedi, E. Assessing the influence of a passive, upper extremity exoskeletal vest for tasks requiring arm elevation: Part I—Expected effects on discomfort, shoulder muscle activity, and work task performance. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 70, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Esfahani, M.I.M.; Alemi, M.M.; Jia, B.; Rashedi, E. Assessing the influence of a passive, upper extremity exoskeletal vest for tasks requiring arm elevation: Part II—Unexpected effects on shoulder motion, balance, and spine loading. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 70, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goršič, M.; Song, Y.; Dai, B.; Novak, D. Evaluation of the HeroWear Apex back-assist exosuit during multiple brief tasks. J. Biomech. 2021, 126, 110620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Madinei, S.; Alemi, M.M.; Srinivasan, D.; Nussbaum, M.A. Assessing the potential for “undesired” effects of passive back-support exoskeleton use during a simulated manual assembly task: Muscle activity, posture, balance, discomfort, and usability. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 89, 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, T.; Schändlinger, J.; Schuler, M.; Bornmann, J.; Schirrmeister, B.; Kannenberg, A.; Ernst, M. Biomechanical and metabolic effectiveness of an industrial exoskeleton for overhead work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madinei, S.; Alemi, M.M.; Kim, S.; Srinivasan, D.; Nussbaum, M.A. Biomechanical assessment of two back-support exoskeletons in symmetric and asymmetric repetitive lifting with moderate postural demands. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 88, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madinei, S.; Alemi, M.M.; Kim, S.; Srinivasan, D.; Nussbaum, M.A. Biomechanical evaluation of passive back-support exoskeletons in a precision manual assembly task: Expected effects on trunk muscle activity, perceived exertion, and task performance. Hum. Fact. 2020, 62, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.; Yang, L.; Qu, S.; Wang, C. Effects of a passive upper extremity exoskeleton for overhead tasks. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2020, 55, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdulkarim, S.; Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A. Effects of exoskeleton design and precision requirements on physical demands and quality in a simulated overhead drilling task. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 80, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemi, M.M.; Madinei, S.; Kim, S.; Srinivasan, D.; Nussbaum, M.A. Effects of two passive back-support exoskeletons on muscle activity, energy expenditure, and subjective assessments during repetitive lifting. Hum. Fact. 2020, 62, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, S.; Piedrabuena, A.; Iordanov, D.; Martinez-Iranzo, U.; Belda-Lois, J.M. Ergonomics assessment of passive upper-limb exoskeletons in an automotive assembly plant. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 87, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engelhoven, L.; Poon, N.; Kazerooni, H.; Barr, A.; Rempel, D.; Harris-Adamson, C. Evaluation of an adjustable support shoulder exoskeleton on static and dynamic overhead tasks. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1–5 October; SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moyon, A.; Poirson, E.; Petiot, J.F. Experimental study of the physical impact of a passive exoskeleton on manual sanding operations. Proced. CIRP 2018, 70, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, T.; Seibt, R.; Cobb, T.J.; Rieger, M.A.; Steinhilber, B. Influence of a passive lower-limb exoskeleton during simulated industrial work tasks on physical load, upper body posture, postural control and discomfort. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 80, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefferle, M.; Snell, M.; Kluth, K. Influence of two industrial overhead exoskeletons on perceived strain—A field study in the automotive industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–20 July 2020; pp. 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Luque, E.P.; Högberg, D.; Pascual, A.I.; Lämkull, D.; Rivera, F.G. Motion behavior and range of motion when using exoskeletons in manual assembly tasks. In Proceedings of the SPS2020: Swedish Production Symposium, Jonkoping, Sweden, 7–8 October 2020; Volume 13, p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice, P.; Čamernik, J.; Gorjan, D.; Schirrmeister, B.; Bornmann, J.; Tagliapietra, L.; Latella, C.; Pucci, D.; Fritzsche, L.; Ivaldi, S.; et al. Objective and subjective effects of a passive exoskeleton on overhead work. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehab. Eng. 2019, 28, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spada, S.; Ghibaudo, L.; Carnazzo, C.; Gastaldi, L.; Cavatorta, M.P. Passive upper limb exoskeletons: An experimental campaign with workers. In Proceedings of the Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, Florence, Italy, 26–30 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Bock, S.; Ghillebert, J.; Govaerts, R.; Elprama, S.A.; Marusic, U.; Serrien, B.; Jacobs, A.; Geeroms, J.; Meeusen, R.; De Pauw, K. Passive shoulder exoskeletons: More effective in the lab than in the field? IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehab. Eng. 2020, 29, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.; Gaspar, J.; Fujão, C.; Nunes, I.L. Piloting the use of an upper limb passive exoskeleton in automotive industry: Assessing user acceptance and intention of use. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–20 July 2020; pp. 342–349. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilber, B.; Seibt, R.; Rieger, M.A.; Luger, T. Postural control when using an industrial lower limb exoskeleton: Impact of reaching for a working tool and external perturbation. Hum. Fact. 2020, 0018720820957466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daratany, C.; Taveira, A. Quasi-experimental study of exertion, recovery, and worker perceptions related to passive upper-body exoskeleton use during overhead, low force work. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Interaction and Emerging Technologies, France, Paris, 27–29 August 2020; pp. 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrusch, S.J.; Van Dieën, J.H.; Koopman, A.S.; Näf, M.B.; Rodriguez-Guerrero, C.; Babič, J.; Houdijk, H. SPEXOR passive spinal exoskeleton decreases metabolic cost during symmetric repetitive lifting. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baltrusch, S.J.; van Dieën, J.H.; Bruijn, S.M.; Koopman, A.S.; van Bennekom, C.A.M.; Houdijk, H. The effect of a passive trunk exoskeleton on functional performance and metabolic costs. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Wearable Robotics, Pisa, Italy, 16–20 October 2018; pp. 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrusch, S.J.; Van Dieën, J.H.; Bruijn, S.M.; Koopman, A.S.; Van Bennekom, C.A.M.; Houdijk, H. The effect of a passive trunk exoskeleton on metabolic costs during lifting and walking. Ergonomics 2019, 62, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, A.; Colim, A.; Sousa, N. The Effects of a Passive Exoskeleton on Muscle Activity and Discomfort in Industrial Tasks. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Wang, W.; Qu, Z.; Gu, J.; Lin, X.; Yue, C. The effects of a passive exoskeleton on muscle activity and metabolic cost of energy. Adv. Robot. 2020, 34, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, T.; van Eck, J.; Knitel, K.; de Looze, M. The effects of a passive exoskeleton on muscle activity, discomfort and endurance time in forward bending work. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 54, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A. Stuttgart Exo-Jacket: An exoskeleton for industrial upper body applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI), Ulsan, Korea, 17–19 July 2017; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).