Abstract

Dynamic interactions between gut microbiota and a host’s innate and adaptive immune systems are essential in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and inhibiting inflammation. Gut microbiota metabolizes proteins and complex carbohydrates, synthesizes vitamins, and produces an enormous number of metabolic products that can mediate cross-talk between gut epithelium and immune cells. As a defense mechanism, gut epithelial cells produce a mucosal barrier to segregate microbiota from host immune cells and reduce intestinal permeability. An impaired interaction between gut bacteria and the mucosal immune system can lead to an increased abundance of potentially pathogenic gram-negative bacteria and their associated metabolic changes, disrupting the epithelial barrier and increasing susceptibility to infections. Gut dysbiosis, or negative alterations in gut microbial composition, can also dysregulate immune responses, causing inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. Over time, chronic dysbiosis and the leakage of microbiota and their metabolic products across the mucosal barrier may increase prevalence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and a variety of cancers. In this paper, we highlight the pivotal role gut bacteria and their metabolic products (short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)) which play in mucosal immunity.

1. Gut Microbiota Metabolites (SCFAs)

Understanding the interactions between a host immune system and microbiota that live in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is an active area of research [1]. Under normal circumstances, gut microbiota produces metabolites to communicate with the immune system and modulate immune responses [2]. These metabolites play key roles in inflammatory signaling, interacting both directly and indirectly with host immune cells [1]. Some bacteria, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia intestinalis, and Anaerostipes butyraticus [3], digest complex carbohydrates via fermentation, creating short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [4,5,6] that regulate host immune cells and provide a carbon source for colonocytes [7,8]. SCFAs, consisting mainly of butyrate, propionate, and acetate [1,9], are microbiota-derived metabolites enriched in the gut lumen. By binding G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and altering gene expression via reducing the activity of histone deacetylases (HDACs), SCFAs are essential for reducing local inflammation, protecting against pathogen infiltration, and maintaining intestinal barrier integrity.

Colonocytes absorb SCFAs, especially butyrate, via sodium-dependent monocarboxylate transporter-1 (SLC5A8). Epigenetic alteration of gene expression via inhibition of HDACs is regulated through SLC5A8, which controls butyrate ingress into colonic epithelial cells. SCFAs also stimulated G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs), such as GPR41, GPR43 (also known as free fatty acid receptors (FFAR)-3 and -2), GPR109a (also known as HCA2, niacin/butyrate receptor), and olfactory receptor-78 (Olfr-78) [10,11,12]. SCFAs have multiple functions that are tissue or cell type dependent. For example, in addition to regulating cellular turnover and barrier functions that maintain intestinal epithelium physiology, SCFAs also exhibit anti-inflammatory properties on host immune cells, regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Interleukin-12 (IL-12), Interleukin-6 (IL-6) through activation of macrophages and DCs [13].

Several studies have shown, both in vitro and in vivo, that the differentiation of T-regulatory (Treg) cells is stimulated by butyrate treatment, limiting the onset of colitis that co-occurs with the adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhi T-cells in Rag1−/− mice [14]. Butyrate also modulates the expression of anti-inflammatory forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3), a critical step to reducing inflammatory responses [14,15]. Moreover, the cytokine production profile of T-helper (Th) cells promoted by butyrate limited aberrant inflammatory effects by reducing interactions between luminal microbiota and the mucosal immune system [16]. By binding GPR109a on DCs and macrophages, the presence of butyrate lead to increased levels of IL-10 and decreased production of IL-6, resulting in increased Treg cell development while inhibiting the expansion of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells. Therefore, GPR109a induces apoptosis, strengthens anti-inflammatory pathway, and provides a defense against inflammation-associated colon cancer [11]. However, GPR109a stimulation of pro-inflammatory Cox-2-dependent signaling, commonly seen in human epidermoid cancers, induces GPR109A-mediated flushing in keratinocytes [17]. GPR109a activation can act to either suppress or promote tumor growth, contingent on the tissue type and local cellular context.

Acetate, a SCFA highly produced by Bifidobacteria, also regulates intestinal inflammation by stimulation of GPR43 [18], helping to maintain gut epithelial barrier function [19]. Maslowski et al. [18] found that SCFAs-mediated GPR43 activation was essential for some inflammatory responses to clear, with GPR43-deficient (Gpr43−/−) mice showing chronic inflammation in models of asthma, arthritis, and colitis. In addition to demonstrating higher levels of inflammatory moderators and elevated intake by Gpr43−/− immune cells, Maslowski et al. demonstrated a similar dysregulation of inflammatory responses in germ-free mice, suggesting GPR43 interactions with SCFAs as a molecular link connecting gut bacterial metabolites and host immune and inflammatory responses. Moreover, SCFA-mediated GPR43 signaling attenuates NOD-like receptors (NLRs), such as pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) and leucine-rich repeat (LRR), reducing both inflammasome activity and subsequent secretion of IL-18, [20,21], a pro-inflammatory cytokine with essential roles in colonic inflammation and inflammation-associated cancers [11,22]. Acetate also exhibits anti-inflammatory properties in neutrophils, reducing NF-kB activation by inhibiting the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α, though to a lesser degree than propionate or butyrate [23,24].

SCFAs have multiple mechanisms of inhibiting inflammation in the gut [25], and are well-known HDAC inhibitors, stimulating histone acetyltransferase activity and stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). HDACs are enzymes that cleave acetyl groups from acetyl-lysine amino acid in histones and various non-histone proteins to change the conformation of the nucleosome, thereby regulating gene expression. SCFA-driven inhibition of HDACs tends to produce immunological tolerance, managing immune homeostasis by producing an anti-inflammatory cellular phenotype. HDAC inhibitors directly inhibited tumor cell growth by stimulating apoptosis and cell cycle arrest using epigenetic mechanisms and by disrupting T-cell chemotaxis in the local environment [26]. Many studies have observed that HDACs are inhibited by SCFAs, mainly propionate and butyrate, leading to suppressed inflammatory responses in immune cells and tumors [13,24,26,27,28], and suppression of HDACs is considered the probable mechanism by which butyrate and propionate hinder DC development [11]. SCFA exposure to peripheral blood mononuclear cells and neutrophils downregulated production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and inactivated NF-κB, similar effects to global HDAC inhibition [29]. Butyrate inhibits HDACs via induced Zn2+ binding in their active site [30], enhancing histone H3 acetylation at conserved Foxp3 promoter and enhancers sequences, inducing vigorous gene expression and functional maturation [31,32].

2. Interactions between Gut Microbiota and Immune Cells

2.1. Immune Regulation of Gut Microbiota

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) regulate immune response and alter the local environment through the identification and uptake of SCFAs, using both passive and active mechanisms. Only acetate achieves high concentrations in systemic circulation and the liver processes a large portion of propionate, but IECs metabolize the majority of absorbed butyrate. Butyrate derived from commensal bacteria, via transcription factor binding and HDAC inhibition, stimulated the manufacture of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in IECs, and the consequent confluence of Treg cells in the gut environment [33,34].

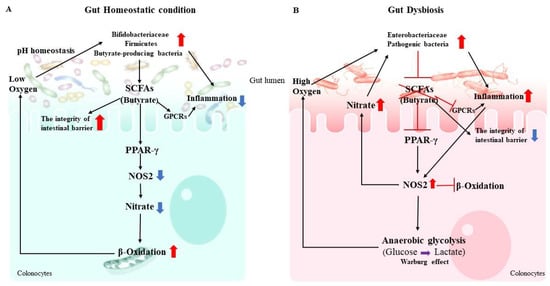

The maintenance of immunologic homeostasis in the mucosal layer is a demanding task requiring the discrimination between billions of beneficial commensals and pathogenic invaders. Gut homeostasis is mediated by the preponderance of obligate anaerobic members of Firmicutes and Bifidobacteriaceae, whereas increase in facultative anaerobic Enterobacteriaceae is a common marker of gut dysbiosis [35]. Under gut homeostatic conditions, the IEC synthesized peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) is stimulated by butyrate. PPAR-γ helped maintain a local hypoxic environment by encouraging oxidative phosphorylation in colonocytes and β-oxidation of SCFAs by the mitochondria [35]. The obligate anaerobic SCFA-producing bacteria grow vigorously in such an environment, while the facultative anaerobic enteric pathogens’ growth is suppressed [35,36]. Concurrently, PPAR-γ activation decreases NOS2 levels in IECs, hindering the manufacture of both inducible NO synthase and nitrate, critical sources of energy for facultative anaerobic pathogens [35]. Moreover, propionate provides resistance to the expansion of pathogenic bacteria in a PPAR-γ-independent manner, proposing some similarity in SCFA effects. Indeed, SCFAs mediate the intracellular acidification of pathogens, which is protective against pathogen infection. For example, one important function of propionate is to limit pathogen expansion by facilitating the cytoplasmic acidification of Salmonella or Shigella, disrupting the balance of intracellular pH for the pathogens. Accumulation of SCFAs and the decreasing pH hinder O2 and NO3 respiration, removing a competitive advantage to the growth of facultative anaerobes such as Enterobacteriaceae. Conversely, inhibiting the PPAR-γ signaling pathway stimulates metabolic reprogramming, gut dysbiosis, and SCFA exhaustion. This reprogramming encouraged colonocyte metabolism to adopt anaerobic glycolysis, called the Warburg effect, and limited the use of oxidative metabolism, increasing the concentration of oxygen, nitrate, and lactate in the gut lumen [35]. Additionally, virulence factors common to Enterobacteriaceae, such as Salmonella or Shigella, stimulates the migration of neutrophils through the epithelium, reducing the abundance of SCFAs. This acts as a negative feedback loop, encouraging pathogen growth, and demonstrating a causal interaction connecting microbiota-derived metabolism and gut epithelial health [37]. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, promote an oxygen free environment by stimulating PPAR-γ, disrupting the pH balance and inhibiting the colonization of pathogens (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The interaction between microbiota-derived metabolism in the gut epithelium. (A) In the gut homeostatic condition, gut microbiota, especially butyrate-producing bacteria, metabolizes fiber into fermentation products such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These SCFAs stimulate a PPAR-γ–dependent stimulation of mitochondrial-oxidation, consequently decreasing epithelial oxygenation. SCFAs also directly bind to epithelial and immune cell G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that reduce gut inflammation, such as GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109A. (B) During gut dysbiosis, Enterobacteriaceae use virulence factors to stimulate neutrophil migration through the epithelium, reducing SCFA-producing bacteria, decreasing the abundance of short-chain fatty acids in the lumen. The subsequent metabolic shifts of the epithelial layer increases available oxygen (O2) and lactate in the lumen. Arrows represent increases (red) and decreases (blue) in bacterial abundances, metabolites, and downstream effects observed in the homeostatic and dysbiotic guts.

Host-body defense systems use multiple mechanisms to discourage colonization by pathogens. Recognition of gut microbiota initiates with two pattern recognition receptor systems (PRRs): nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptors (NODs) and toll-like receptors (TLRs) [38,39]. PRRs are highly expressed in IECs, macrophages, and intestinal DCs. PRRs identify microbe- or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs or PAMPs) on pathogens and commensals alike [40]. After a microbe has been identified or has overrun the epithelium, an immunologic response targeted to the microbe is mounted [38]. Upon PAMP recognition, PRRs activate a variety of intracellular signaling pathways, using chains of ligands, transcription factors, and kinases to signal the presence of infection in the host and trigger changes in gene expression that alter levels of a range of pro-inflammatory and anti-microbial cytokines, chemokines, and immunoreceptors. Decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-23, IL-12, and IL-8, mediated protective effects, including increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as Treg cell manufactured IL-10s [41,42,43]. The DCs transported the antigen to naive T-cells, and the subsequent production of anti-inflammatory cytokines initiated systemic and local tolerance [44].

Gut microbiota communities change in composition as we traverse the GI tract, and within the distinct lamina of intestinal mucus. The proximal small intestine is much less active immunologically than the ileum and colon, and the colonization of enteric microorganisms in the gut promoted an increase in permeability that allowed macromolecules and antigens to pass from the intestine to the bloodstream, which may cause immune-mediated pathologic conditions [45]. Gut permeability has been closely linked to both commensal microbiota and elements of the mucosal immune system, and is influenced by many factors including alterations to mucus layers, epithelial damage, and changes to the composition of gut bacteria [46,47]. Gut microbial fermentation products and cellular components play pivotal roles in host immune responses that maintain epithelial integrity. For example, flagellin, the principal component of bacterial flagellum, and the flagellar filament’s structural protein subunit are recognized by TLR-5. The activation of TLR-5, strongly expressed in B-cells and CD4+ T-cells, by this bacterial agonist induced the differentiation of B lymphocytes into IgA-producing cells, which then bound to microbial antigens, neutralizing their pathogenic activity and preventing infection [48,49].

Commensal bacteria decrease phagocyte migration, which transfers bacterial antigens to nearby lymphoid tissues, inducing activation of T-cells and B-cells. Goblet cell differentiation and manufacture of the epithelial mucosa are accelerated by commensal bacteria, while pathogens induce DCs to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines [50]. As a result, pro-inflammatory immune responses are activated through naive T cell differentiation [51]. The activation of different TLRs members occurred dependent on the gram-negative bacteria present and their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) modifications [52,53]. LPS is an archetypal pathogen-associated molecular pattern present in Gram-negative bacteria, that mammalian cells use as a marker of bacterial invasion and to initiate innate immune responses. The polysaccharide portion of LPS acts as a defense mechanism for bacteria, helping to prevent complement attacks and hide among carbohydrate residues common in the host. Host innate immunity is initiated via signal transduction pathways triggered by the TLR4/MD-2 complex, which recognizes the LPS lipid moiety. Modifications are believed to ameliorate bacterial circumvention of host immunity, increasing pathogenicity. However, the enrichment of SCFA-producing bacteria significantly limited the abundance of Gram-negative bacteria, subsequently decreasing the levels of LPS [54,55].

It has been clearly shown that gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) promote the production of IgA following microbiota colonization. IgA performed a fundamental task in mucosal homeostasis in the gut, functioning as the dominant antibody [56]. GALT is a tissue consisting of Peyer’s patches (PPs), plasma cells, and lymphocytes from the mesenteric lymph nodes and lamina propria. GALT maintained the immune response via up-take of gut luminal antigens through M-cells, activating antigen-specific immune responses [57]. Studies of germ-free mice have shown several immunodeficiencies, including fewer splenic CD4+ T-cells, structural splenic disorganization, fewer intraepithelial lymphocytes, decreased conversion of follicular-associated epithelium to M-cells, decreased secretory IgA (SIgA), and decreased ability to induce oral tolerance. SIgA functions to neutralize and reduce the abundance of pathogen associated toxins in the gut lumen. For example, during transcytosis (also known as cytopempsis), rotavirus was neutralized through the epithelial barrier, inhibiting the migration and subsequent inflammation associated with Shigella LPS leakage. In addition M-cells are commonly found in the epithelium and known as antigen delivery cells, which bind to IgA [58,59]. SIgA selectively interacted with M-cells in the mouse ilium, whereas other immunoglobulins, including IgG and IgM, did not [60]. Groups have shown that the interactions between gut bacteria and mucosal antibodies are taken up by CD11+ DCs in the PPs (PP-DCs), providing an immune system based on intestinal IgA [61,62]. Thus, PPs act as secondary gut mucosa based immune organs, containing B lymphocyte filled follicles and intrafollicular areas of T lymphocytes. Recombination of IgM to IgA and B-cell activity was promoted by PPs and isolated lymphoid follicles [60]. Studies further showed that luminal microbiota bound to SIgA increased their presence in PPs [62,63]. The depletion of IgA regulation results in dysregulation of gut microbiota, which in turn causes immune system dysfunction.

2.2. Gut Dysbiosis and Immune Dysregulation

One’s gut microbiota ecology is dynamic, changing in response to age, diet, geographical location, medication use, and ingress and egress of microbiota [64]. Most bacteria are introduced through environmental exposure, but some are transient and lacked the capacity to permanently colonize the intestinal environment or are outcompeted by commensal microbes [64]. The health of the microbial community at a site can be ascertained in terms of stability, diversity, resistance and resilience [65]. Briefly, it characterizes the richness of the ecosystem, its vulnerability to compositional and functional change, and its capability of reestablishing itself to its original state. Thus, the ecological balance of the microbial community can be disturbed by loss of diversity, thriving of pathobionts, or withering of commensals [66].

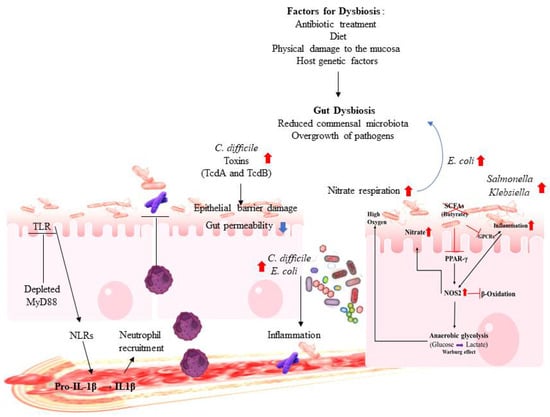

Gut dysbiosis refers to changes in the gut bacterial composition and functional abilities which leads to adverse effects on the host health [67]. Some commensal bacteria inhibited the growth of opportunistic pathogens via SCFA production, which alters intestinal pH [19]. For example, Bifidobacterium reduced the intestinal pH during fermentation of lactose, thereby preventing colonization by pathogenic Escherichia coli [19,68]. Commensal bacteria do not only restrict pathogen virulence by changing environmental conditions, but bacterial metabolites also directly suppress the virulence genes of pathogens. For instance, Shigella flexneri required oxygen for the competent secretion of virulence factors, but commensal facultative anaerobes, such as constituents of the Enterobacteriaceae family, consumed the residual oxygen, leading to low levels of Shigella virulence factors in the gut lumen [69]. However, many factors can be a cause of dysbiosis, including invasive intestinal pathogens, antibiotic treatment, physical damage to the mucosa, diet, and host genetic factors [70]. While dysbiosis differs among pathologic conditions and individuals, some patterns have emerged. The relative abundance of obligate anaerobes commonly decreases in human and mice gut dysbiosis, whereas the abundance of potentially pathogenic facultative anaerobes, including Shigella, Salmonella, E. coli, Proteus, and Klebsiella, have been noted to increase [71]. One consequence of dysbiosis is greater susceptibility to enteric infection, and perturbation of the commensal microbiota composition with antibiotics induced inflammation. Commensal bacteria normally inhibit the growth of pathogens such as E. coli, but antibiotic treatment increased the abundance of E. coli in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mice, encouraging systemic circulation of the pathogen and promoting activation of the inflammasome [72]. Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is the primary culprit behind hospital-associated infections, which normally presents at low abundance in the healthy adult gut [73]. Perturbation of commensal gut bacteria by broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment in hospitalized patients produced a significant increase in C. difficile abundance and severe gut inflammation [73]. Similar effects have been observed across species, with antibiotic treatment increasing the incidence of C. difficile infection in murine models, as well [72]. C. difficile produces toxins such as TcdA and TcdB that can destroy the epithelial barrier and increase gut permeability. Epithelial damage caused by these toxins can encourage systemic circulation of both bacteria and bacterial metabolites, increasing systemic inflammation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gut dysbiosis. Multiple factors including diet, antibiotic treatment, and host genetic caninterrupt the community of commensal microbial, resulting in increased colonization by pathogens and the outgrowth of indigenous pathobionts, such as Clostridium difficile. C. difficile can produce toxins, such as TcdA and TcdB, that destroy the epithelial barrier and increase gut permeability. Increased systemic inflammation occurs with a systemic circulation of bacteria related to toxin-mediated epithelial damage. Pathogen-induced gut inflammation grants growth benefits to pathogenic bacteria through the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which is later metabolized by the host innate immune cells resulting in the release of nitrate (NO3−), which can be consumed by Escherichia coli and processed through nitrate respiration to generate energy. The infection of pathogenic bacteria causes the changing of proIL-1β into the enzymatically active form of IL-1β, activating neutrophil recruitment and pathogen removal. NLRP3 inflammasome is stimulated via bacterial toxins, subsequently inducing caspase-1 proteolytic activation, which results in released biologically active IL-1β and IL-18. Arrows represent increases (red) and decreases (blue) in bacterial abundances, metabolites and downstream effects observed in the antibiotic treated dysbiotic gut.

Dysbiosis does not always involve increases in the abundance of pathogens, as the lack of important commensal bacteria alone can be adverse. In contrast to the outgrowth of potentially pathological bacteria, dysbiosis frequently occurred with diminished bacterial proliferation. Depleted commensals have important functions, and recovery of missing microbes or their metabolites had the capacity to alter phenotypes associated with the perturbed gut [66]. The immune system–gut microbiota crosstalk is of upmost as commensal bacteria enhance the mucosal barrier and promote innate immune responses against invading pathogens. For instance, germ-free and toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling adaptor myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88) knock-out mice exhibited specific intestinal microbiota and diminished production of antimicrobial peptides [74]. Moreover, increased mucosa-associated bacterial abundance, migration of microbiota to the mesenteric lymph nodes, and changing bacterial composition, were associated with loss of MyD88 signaling in epithelial cells [75,76]. After infection with pathogenic Salmonella or Pseudomonas, cytokines such as interleukin 1β (IL-1β) were essential for recruitment of neutrophils and elimination of the pathogenic intruders via NLRs [77], such as NLRP1, NLRP3, and NLRC4 [78]. Bacterial toxins stimulated the NLRP3 inflammasome, driving the activation of caspase-1, causing the release of biologically active IL-18 and IL-1β (Figure 2) [79].

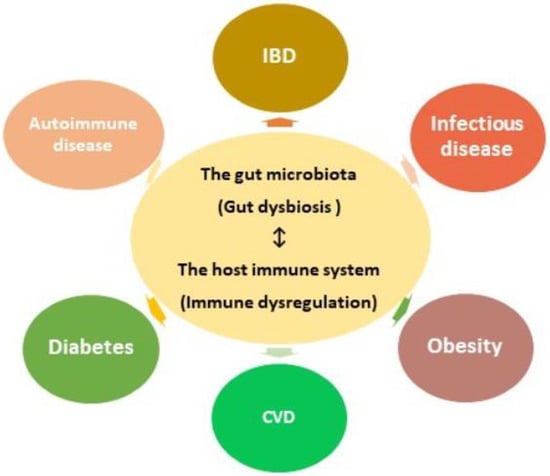

Although members of the microbial community are often considered to be commensals, the relationship can be commensal, mutualistic, or even parasitic. In fact, the relations linking gut microbes and the host immune system can be extremely contextual, defined by the environmental landscape, diet, and coinfections in the host [2]. Gut bacteria stimulated maturing of the immune cells and system [80], while gut dysbiosis has been associated with immune dysregulation, subsequently raising the risk of developing diseases, including diabetes, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Figure 3) [81,82].

Figure 3.

Human gut microbial dysbiosis has a close relationship with diseases. The immune system–gut microbiota crosstalk is of sublime significance in understanding the role of dysbiosis-driven diseases in humans. Gut dysbiosis induces immune dysregulation and subsequently increase the risk of developing diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), infectious disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and autoimmune disease.

Diversity and abundance of gut microbiota were established as vital determinants of host health, and changes in diversity have been identified with a variety of diseases in humans. Whether the microbiota contributes directly to the etiology of all associated diseases remains unknown. However, many studies have shown that gut bacteria are directly involved in the onset and progression of specific diseases through a complex network linking metabolism and host immune systems [83,84,85]. The association between gut dysbiosis and mucosal inflammation might be a cause of dysbiosis, its consequence, or perhaps both acting in tandem. Gut bacteria were strongly related to the onset and progression of inflammation in the mucosal layers of germ-free mice [86]. One common cause of gut dysbiosis, observed in both clinical and animal models, is infection. Infectious diseases and their treatments influence the human gut microbiota, creating feedback loops which alter the local environment and ultimately determine the effect of the infection on the host microbes. Many studies have verified the close connections linking infection and gut dysbiosis and have demonstrated relationships with both gut bacteria and resident viruses [87]. For example, Clostridium difficile infection patients had gut microbiota that were significantly altered in a manner that promoted the progression of the hepatitis B virus (HBV), the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other infectious diseases [35,88].

3. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota and Related Diseases

The mucosal barrier secreted by gut epithelial cells acts as a defense mechanism, segregating microbes from host immune cells and reducing intestinal permeability. Disrupting the epithelial barrier increases susceptibility to infection and the displacement of microbial metabolites into the host. Gut dysbiosis, or negative alterations in the gut microbial composition, not only reduces the integrity of the mucosal barrier, but also dysregulates immune responses, causing inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. Over time, chronic gut dysbiosis and the passage of bacteria and their metabolic products through the mucosal barrier can increase the prevalence of a variety of diseases. Below, we highlight conditions with strong experimental and clinical models linking the subversion of the mucosal immune system and associated environmental responses, such as inflammation, with disease onset and severity.

3.1. Gut Microbiota and Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation on Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) and CVD

A number of studies provide evidence supporting associations between gut dysbiosis, T2DM (non-insulin-dependent), and CVD [80,81,82,83]. One cause of T2DM is reduced insulin function in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue [84]. Insulin is a hormone that acts as a key mediator regulating glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism. Insulin has varied functions, including regulating gene expression, stimulating metabolite uptake into cells, altering enzymatic activity, and maintaining energy homeostasis. Insulin also enhanced glucose uptake by promoting relocation of the principal glucose transporter (GLUT4) to the cell membrane in skeletal muscle and other tissues [85]. In skeletal muscle, GLUT4 functions in insulin-dependent glucose disposal [86,87]. As a result, poor insulin signaling leads to impaired glucose disposal in skeletal muscle, markedly seen in T2DM patients. Although the precise cause of resistance to insulin in skeletal muscle remains elusive, increased intramyocellular lipid content and free fatty acid (FFA) metabolites play an essential role [88,89]. Increased circulating FFAs decreased the sensitivity of skeletal muscle to insulin via increased levels of fatty acyl-CoA, ceramide, and other intracellular lipid products [90,91]. These lipid metabolites activated the serine/threonine kinase protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ), inhibiting downstream insulin signaling. The inhibition of insulin signaling in the liver induced the activity of important gluconeogenic enzymes, resulting in insulin resistance and increased hepatic glucose production [92]. Reduced activity in hormone sensitive lipase and the anti-lipolytic effect inhibited FFA efflux from adipocytes by adipose tissue insulin signaling. Disruption of these processes occurred in both insulin resistance and deficiency, and elevating fasting and postprandial glucose and lipid levels, major causes of T2DM and CVD [93].

A well-known gut microbiota related pathway is trimethylamine–N-oxide (TMAO) metabolism. Dietary phospholipids (lecithin, choline, and carnitine) are anaerobically metabolized by bacteria, yielding the products ethanolamine and trimethyl amine (TMA). Gut microbial TMA lyases cleave the C-N bond of dietary phospholipids, producing TMA as a waste product. These nutrients are all substrates of gut bacteria and are metabolized to form the products TMA/TMAO. Conversion of TMA to TMAO proceeds through an oxidation pathway moderated by host hepatic enzymes, including flavin monooxygenases (FMOs), to which TMA is exposed via portal circulation, forming TMAO. Elevated TMAO has been correlated with incidence of CVD and increased danger of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, revascularization, and oxidation, and has also been used to predict major negative cardiac outcomes over a three-year period [94]. While increased circulating levels of betaine, choline, and carnitine have been correlated with future risk of negative cardiac outcome, their prognostic value was limited without a similar elevation in TMAO levels. Wang et al. (2011) [95] demonstrated an increased risk of atherosclerosis associated with plasma choline, TMAO, and betaine levels in mice and humans. Further studies show TMAO levels are associated with abundances of the genera Prevotella and Bacteroides, and applied dietary TMAO supplementation promoted decreased total cholesterol absorption in mouse models [96].

Numerous studies support the association between chronic low-grade inflammation, T2DM, and CVD [97]. Insulin resistance often results in compensatory hyperinsulinemia, one cause of metabolic disruptions commonly seen in metabolic syndrome, a precursor to CVD [87]. Moreover, low-grade inflammation is related to the presence of excessive visceral fat, and can lead to insulin resistance, greater macrophage infiltration, and the subsequent manufacture of pro-inflammatory adipokines. This chronic low-grade inflammation via the suppression of the insulin-signaling pathway in peripheral tissues was associated with T2DM and the development of CVD [98]. The excess of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 are associated with reduced insulin action, and help modulate interactions linking the immune system and insulin signaling.

The gut dysbiosis associated with T2DM has been well-documented, including decreased populations of butyrate-producing bacteria and increased resistance to oxidative stresses characteristic of opportunistic pathogens [99,100]. SCFAs increased anti-inflammatory responses in the host body, however, T2DM patients have shown significantly fewer SCFA-producing bacteria and significantly increased LPS levels [97,101]. LPS leakage into the body from gram-negative microbes is a contributing factor for low-grade inflammation, inducing the release of proinflammatory molecules. Systemic inflammation was strongly correlated with high levels of triglycerides and decreased serum HDL, increased blood pressure, and increased fasting glucose [101,102], molecules that increased intestinal epithelial inflammation and translocation through the gut barrier. LPS receptors were found to be critical mediators that potentially activate underlying insulin resistance. In pancreatic islets, TLR4 increased proinflammatory cytokine levels, limiting macrophage and beta-cell viability and reducing their functionality [103]. Moreover, the activation of TLR4 was directly related to lower mRNA levels of pancreas-duodenum homeobox-1 (PDX-1), lower insulin mRNA and protein levels, and reduced insulin-induced glucose secretion. Also, LPS upregulated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) levels and initiated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-mediated signaling in lipocytes. The anti-inflammatory effects of SCFAs likely arise from a balance, reducing the levels of proinflammatory mediators and promoting anti-inflammatory cytokine production. Butyrate and propionate not only reduced the levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in human adipose tissue, but also stimulated the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 by monocytes interactions with bacteria. SCFAs decreased low-grade inflammation through their ability to modulate both leukocytes and adipocytes, decreasing inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels [104]. Other studies have demonstrated that SCFAs ameliorated the LPS-induced neutrophil release of TNF-α. Accordingly, SCFAs significantly reduce expression of several inflammation associated cytokines and chemokines in adipocytes, decreasing the risk of T2DM and CVD.

Another important function of SCFAs in T2DM is binding GPCRs, triggering various downstream effects. SCFAs stimulate healthy glucose tolerance through the release of gut-derived incretin hormones such as Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This hormone is primarily synthesized by intestinal L-cells and released into circulation during meal ingestion. GLP-1 stimulates weight loss by reducing glucagon secretion and hepatic gluconeogenesis, while increasing insulin response, improving satiety. The utility of GLP-1 for treatment purposes has been noted, as several therapeutic agents enhancing GLP-1 are available and successfully used to monitor blood glucose levels in patients with T2D, as well as providing improved body weight management in obese patients. Intravenous GLP-1 is efficient in promoting insulin release and decreasing hyperglycemia in T2DM patients. Furthermore, GLP-1 mimetics and a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor are commonly used therapeutic approaches in clinics [105]. In particular, injectable GLP-1 mimetics are associated with decreased concentrations of fasting and postprandial glucose, decreased hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and significant weight loss.

Among SCFAs, propionate and acetate strongly stimulated GLP-1 release, while butyrate provided a weaker stimulation [106]. However, improved GLP-1 synthesis and secretion has been noted in the human L-cell line treated with butyrate. Further, the improvements noted after administration of the prebiotic showed the association with increased secretion of GLP-1, reduced insulin resistance, and decreased body weight gain [107]. Mechanisms by which GLP-1 secretion is improved after SCFA treatment are still a matter of debate. The limited response of GLP-1 to SCFA treatment in the GLUTag cell line coincides with low levels of GPR43 [106]. Extended exposure to a high-fat diet generated lower levels of insulin in GPR43 knockout mice, as opposed to wild-type controls [108]. Conversely, GPR41 may mediate the molecular interactions between butyrate and human L-cells, as increases in butyrate induced GLP-1 expression were correlated with high levels of GPR41. Additionally, the increased GLP-1 secretion stimulated by butyrate was weakened in GPR41 knockout mice [108]. SCFAs are associated with regulation of insulin levels via GLP-1 expression, and result in improvement of metabolic functions in T2DM. The regulation of blood glucose concentrations exerted by SCFAs occur through multiple mechanisms, including reduced insulin resistance from decreased inflammation, the secretion of GLP-1 and subsequent insulin release, and increased beta-cell activity promoting glucose homeostasis.

3.2. Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are chronic conditions of the GI tract characterized by increased levels of inflammation resulting from impaired interactions between microbiota in the gut and the intestinal immune cells. These complex inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) result from a combination of negative environmental stimuli, gut dysbiosis, and host genetics. Major shifts in gut microbial composition, including increases in facultative anaerobic pathogens and decreases in obligate anaerobic producers of SCFAs commonly occur in IBD patients [109]. IBD is characterized by a breakdown in interactions between the resident microbial population and host immune responses. While no single pathogenic species has been etiologically linked to IBD, changes to microbial abundances in the dysbiotic gut play critical roles in the persistent inflammation found observed [97,110,111].

The association of gut microbiota in IBD onset and progression has been demonstrated in both murine models and IBD patients. Initial studies performed by Rutgeerts (1991) [112] and D’Haens (1998) [113] demonstrated the influence of gut microbes in IBD using clinical experiments that showed fecal stream diversion ameliorated the symptoms of CD, and that inflammation resulted when luminal microbiota were subsequently transferred to the terminal ileum. In CD patients, increased gut permeability promotes bacterial translocation through the intestinal mucosa. In healthy individuals, the gut barrier consists of a layer of tightly connected epithelial cells surrounded by a system of tight junction strands from the claudin protein family. In mild to moderate CD, gut barrier dysfunctions resulted mostly from the increased levels of claudin 2, while the expression and redistribution of claudins 5 and 8 was decreased, leading to discontinuous tight junctions [114,115]. In IBD patients, gut dysbiosis occurs due to a combination of colonization by enteric pathogens and host inflammatory responses. Pathogens can use inflammation to translocate across the intestinal mucosal barrier, subverting host inflammatory responses. Salmonella typhimurium, for example, induced inflammation responses that altered the composition of the gut microbiota and promoted its own growth in mouse models [116,117]. Another pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni, is a common bacterial pathogen in humans. In dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mouse models, non-inflammatory infection with Campylobacter jejuni decreased the total number of colonic bacteria, but DSS-induced inflammation encouraged overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae, with both conditions required for maximal gut dysbiosis [118,119]. Harnessing microbiota to influence host immunity is a meaningful treatment strategy for patients with IBD.

Notably, numerous studies have identified changes in bacteria associated with CD, particularly reduced abundances of the phylum Firmicutes and increases in Proteobacteria [114,120]. Specifically, Clostridium clusters IV and XIV have been observed in decreased amounts in IBD patients in contrast to non-IBD controls, revealing that their absence may diminish the gut of anti-inflammatory immunomodulatory ligands and metabolites. Both UC and CD gut microbiota show reduced taxonomic diversity in comparison to healthy controls, along with increased abundance in the phyla Proteobacteria, and decreased abundance of the phyla Firmicutes. The quantity of bacteria from the Clostridia family are also commonly altered, with decreases in Roseburia and Faecalibacterium and increases in Ruminococcus and the Enterobacteriaceae family observed in IBD patients [120,121]. Together, these findings suggest that IBD is ultimately linked to inflammation that may be largely associated with microbially derived or modified metabolites.

Mutations of the NOD2 gene increase susceptibility to CD. PRRs, including TLRs, NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and others, recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns found in microbial pathogens, a critical step in the innate immune response. IBD genetic association studies have discovered functionally relevant polymorphisms in several innate immune genes. Of those identified, mutations in the receptor NOD2 conferred the most risk. NOD2 is an intracellular sensor, detecting microbial pathogens and helping maintain epithelial defense, detecting peptidoglycans through the recognition of muramyl dipeptide [121]. NOD2 activates nuclear factor NF-kB, an inhibitory protein and intracellular receptor that binds portions of microbial pathogens. After binding with intracellular muramyl dipeptide (MDP), NOD2 recruits the adaptor protein RIP2, activating NF-κB and initiating a pro-inflammatory response. One of the first genes associated with susceptibility to CD was NOD2, and NOD2 loss of function mutations frequently occur in IBD patients. In one study, NOD2−/− mice exhibited a large decrease in the number of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), and the remaining IELs showed increased apoptosis and little proliferation. NOD2 signaling recognized gut bacteria and stimulated IL-15 production, maintaining IEL abundances and providing a clue linking NOD2 variation to increased incidence of CD and reduced innate immunity [121].

3.3. Gut Microbiota and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic autoimmune disease that exhibits increased levels of autoantibodies and reduced tolerance to self-antigens, mirroring dysregulation in both the innate and adaptive immune systems. While the pathogenesis is not fully understood, a combination of gut microbiota, host genetics, and environmental factors contribute to SLE [122]. The associated loss of immune tolerance can be stimulated by altered gut microbial composition, with both experimental and clinical models providing evidence of the strong relationship between gut dysbiosis and SLE [123,124,125].

Gut microbiota can stimulate an immune response targeting the host for any of several reasons. In normal cell apoptotic conditions, the host immune system does not involve the release of nuclear antigens. In SLE, however, external stimuli such as bacterial infection, toxins, or ultraviolet (UV) light induce DNA damage and keratinocyte apoptosis. The resulting prolonged autoantigen exposure increased stimulation of host immune cell responses, inducing T-cell activation via suppression of Treg cells in a type I interferon (IFN)-dependent manner [126]. The type I IFN pathway is stimulated by nucleic acid containing cell fragments through recognition by nucleic acid recognition receptors TLR7 or TLR9 [127,128]. Type I IFNs and other cytokines encourage the development and survival of B-cells, inducing the B-cell hyperactivity characteristic of SLE. B-cells create autoantibodies that target self-antigens with high-affinity, causing inflammation and tissue damage. Autoantibodies and immune complexes (ICs) mitigate the inflammatory damage by stimulating complement cascades and interacting with Fc receptors on inflammatory cells. Fc receptors are a heterogeneous collection of hematopoietic cell surface glycoproteins used by immune system effector cells to increase antibody–antigen interactions. These receptors are involved in a host of immune outcomes including phagocytosis, cytotoxicity, inflammatory chemokine and cytokine levels, B-cell activity, and IC clearance. The expression and function of the Fc region in IgG (FcγR) are altered in SLE. FcγR stimulates the manufacture of autoantibodies, resulting in inflammation and IC handling, contributing to the onset and progression of SLE. Altered or delayed removal of ICs containing autoantibodies lead to their accumulation in various tissues, causing inflammation and cellular damage by engaging FcγRs and complement cascades [129,130].

An increased abundance of follicular Th cells and deficiencies in Treg cells have also been associated with SLE pathogenesis. Scalapino et al. (2006) [131] demonstrated with adoptive transfer experiments that Treg cells hindered disease advancement and increased the life span of lupus-prone mice. CD4+ Treg cells preserve auto-tolerance by inhibiting autoreactive immune cells, leading to the hypothesis that Treg cell defects contribute to the onset and severity of SLE. Proinflammatory cytokines were secreted by activated T-cells, which induced B-cell secretion of autoantibodies, pushing both innate and adaptive immune responses closer to autoimmunity [36,132]. In germ-free murine models, T-cell compositions in the gut were affected, displaying reduced responses of Th17 and Treg in the small intestine and colonic lamina propria, respectively [133,134]. Gut microbiota has been associated with the altered composition of Th17 and Treg cells in SLE patients [125]. In patients with SLE, gut microbial composition was significantly enriched in several genera, including Klebsiella, Rhodococcus, Eggerthella, Eubacterium, Prevotella, and Flavonifractor. In contrast, the abundances of Dialister and Pseudobutyrivibrio and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio have been suppressed in SLE patients [123]. It remains unclear whether the observed changes in commensal bacteria are a consequence of the disease process or if gut dysbiosis contributes to SLE onset. However, manipulation of gut microbiota in murine models with antibiotic treatment provided further evidence of gut microbiota influences on systemic immune homeostasis [135,136].

Furthermore, studies showed significant reductions of Lactobacillaceae and increased abundances of Lachnospiraceae in female lupus-prone mice [137]. Lactobacillus, a genus in the Lactobacillaceae family, is a common resident microbiota in human GI tracts. Some Lactobacillus species are marketed as probiotics due to their anti-inflammatory properties, and the decreased abundance of Lactobacillus spp. was most pronounced prior to disease onset. Lactobacillus treatment decreases IL-6 and increases IL-10 production, creating an anti-inflammatory environment in the epithelium. In circulation, Lactobacillus supplementation promoted IL-10 and reduced levels of IgG2a, a significant immune repository in MRL/lpr mice. Thus, Lactobacillus may have a preventive influence in lupus pathogenesis [138]. However, Lactobacillus played a divergent part in alternative lupus murine studies, where the abundance of Lactobacillus spp. correlated strongly with systemic autoimmunity and negatively with renal function in NZB/W F1 mice [124,139]. Consideration of the gut microbiota in murine models and human clinical cases of lupus have offered novel insights on the role of bacteria in SLE onset and progression.

Opposing correlations were reported between pro- and anti-inflammatory free fatty acids (FFAs) and endothelial markers in lupus patients, supporting the connection linking gut microbiota and host metabolism in the etiology of SLE [140]. The altered production of SCFAs stemming from intestinal dysbiosis highlights the role of the gut in maintaining serum FFA levels, further pointing to SCFAs as one potential mechanism for cross talk linking the host metabolism and gut microbiota [140]. Additionally, five perturbed metabolic pathways were identified in feces of SLE patients, including the metabolism of tryptophan, nitrogen, thiamine, and cyanoamino acids, as well as aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis [141]. The aforementioned metabolites can potentially be used as biomarkers for SLE, as long as the effects of potential cofounders, such as smoking, diet, medication, and co-morbidities are considered [142]. Given the role of metabolites in autoimmune diseases, one proposed therapeutic strategy is to promote the differentiation of CD4+ T-cells into Treg cells while avoiding differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells by inducing the fermentation of SCFAs by gut bacteria. The active proliferation SCFA-producing gut microbes has been stimulated using appropriate types of dietary fiber [143], prebiotics such as fructo-oligosaccharides [144,145], or probiotics [146], though direct oral supplementation with SCFAs may be problematic as they are metabolized early in the intestinal tract [147].

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Data from both human patients and mouse models suggest direct links, largely through immunological mechanisms, between gut microbiota and a number of common human illnesses. Many of these links are statistical associations without an understanding of causality, susceptibilities to genetic allelic components, and/or environmental factors that may act in tandem. Dependence upon murine models has both advanced and hindered the field, as many variables affecting mice are not adequately controlled. Further, mice are genetically inbred (lacking the complex genetic variability of humans), have an average life span of two years, and display different receptor sensitivities in comparison with humans. While human and mouse immune systems have many similarities, there are areas that are widely disparate. The murine and human gut microbiota share two major phyla, but 85% of their bacterial genera are not found in humans, and their microbiota is largely driven by a coprophagic diet different from common human diets. Differences in the immune system must also be considered, and the development of humanized immune systems in mouse models will advance our understandings. Therapeutics for altering the gut microbiota in animals is in its infancy, and more basic research is required. In total, these findings indicate that modifications on gut microbiota and their metabolism may be a viable therapeutic and diagnostic target of autoimmune diseases.

Despite our nascent understanding of the part gut microbiota play in the onset and progression of human disease, several mechanisms have been elucidated by which gut microbiota and their metabolic products interact with and regulate both innate and adaptive immune systems. Central to these interactions, and a common theme among seemingly disparate disease states, is subversion of the mucosal layer produced by intestinal epithelial cells and leakage of bacteria and metabolic products through the intestinal barrier. Translocation from the leakage activates a variety of signaling pathways in a manner dependent upon the location sink within the host and the invading species or metabolites. These pathways then stimulate inflammatory immune responses, primarily through the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and alterations to B- and T-cell populations. At each interaction, host genetics likely play a role through receptor activation rates and signaling intensity. The microbial production of SCFAs in the gut, particularly butyrate, reduces intestinal inflammation and increases the integrity of the intestinal barrier, minimizing leakage and bacterial translocation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.Y., M.G., S.V.O.D., A.S., and D.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Samia V. Dutra acknowledges support from the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) for graduate education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kau, A.L.; Ahern, P.P.; Griffin, N.W.; Goodman, A.L.; Gordon, J.I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 2011, 474, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas, D.P.; Marjorie, K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 43, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.; Gibson, G. Microbiological aspects of the production of short-chain fatty acids in the large bowel. In Physiological and Clinical Aspects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Macfarlane, S. Human colonic microbiota: Ecology, physiology and metabolic potential of intestinal bacteria. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1997, 222, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Forano, E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Pomare, E.W.; Branch, W.J.; Naylor, C.P.; Macfarlane, G.T. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 1987, 28, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisar, M.M.; Pelgrom, L.R.; van der Ham, A.J.; Yazdanbakhsh, M.; Everts, B. Butyrate conditions human dendritic cells to prime type 1 regulatory T cells via both histone deacetylase inhibition and G protein-coupled receptor 109A signaling. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, F.; Ding, X.; Wu, G.; Lam, Y.Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, H.; Xue, X.; Lu, C.; Ma, J.; et al. Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science 2018, 359, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluznick, J. A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gurav, A.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Brady, E.; Padia, R.; Shi, H.; Thangaraju, M.; Prasad, P.D.; Manicassamy, S.; Munn, D.H.; et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 2014, 40, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraju, M.; Cresci, G.A.; Liu, K.; Ananth, S.; Gnanaprakasam, J.P.; Browning, D.D.; Mellinger, J.D.; Smith, S.B.; Digby, G.J.; Lambert, N.A. GPR109A is a G-protein–coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinolo, M.A.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Nachbar, R.T.; Curi, R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2011, 3, 858–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; van der Veeken, J.; deRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nabhani, Z.; Dulauroy, S.; Marques, R.; Cousu, C.; Al Bounny, S.; Déjardin, F.; Sparwasser, T.; Bérard, M.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Eberl, G. A weaning reaction to microbiota is required for resistance to immunopathologies in the adult. Immunity 2019, 50, 1276–1288.e1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; He, Z.; Chen, W.; Holzman, I.R.; Lin, J. Effects of butyrate on intestinal barrier function in a Caco-2 cell monolayer model of intestinal barrier. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 61, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasova, M.; Malaval, C.; Gille, A.; Kero, J.; Offermanns, S. Nicotinic acid inhibits progression of atherosclerosis in mice through its receptor GPR109A expressed by immune cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, K.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Ng, A.; Kranich, J.; Sierro, F.; Yu, D.; Schilter, H.C.; Rolph, M.S.; Mackay, F.; Artis, D.; et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009, 461, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, S.; Toh, H.; Hase, K.; Oshima, K.; Nakanishi, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Tobe, T.; Clarke, J.M.; Topping, D.L.; Suzuki, T. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 2011, 469, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowarski, R.; Jackson, R.; Gagliani, N.; de Zoete, M.R.; Palm, N.W.; Bailis, W.; Low, J.S.; Harman, C.C.; Graham, M.; Elinav, E.; et al. Epithelial IL-18 Equilibrium Controls Barrier Function in Colitis. Cell 2015, 163, 1444–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, F.; Bertin, J.; Nunez, G. A functional role for Nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 7187–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedelind, S.; Westberg, F.; Kjerrulf, M.; Vidal, A. Anti-inflammatory properties of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and propionate: A study with relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinolo, M.A.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Hatanaka, E.; Sato, F.T.; Sampaio, S.C.; Curi, R. Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, H.; Chen, P.; Xie, H.; Tao, Y. Demystifying the manipulation of host immunity, metabolism, and extraintestinal tumors by the gut microbiome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, P.V.; Ververis, K.; Karagiannis, T.C. Histone deacetylase inhibition and dietary short-chain Fatty acids. ISRN Allergy 2011, 2011, 869647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.V.; Hao, L.; Offermanns, S.; Medzhitov, R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Du, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, M.-J. Butyrate suppresses murine mast cell proliferation and cytokine production through inhibiting histone deacetylase. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usami, M.; Kishimoto, K.; Ohata, A.; Miyoshi, M.; Aoyama, M.; Fueda, Y.; Kotani, J. Butyrate and trichostatin A attenuate nuclear factor kappaB activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion and increase prostaglandin E2 secretion in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmer, A.; Stangl, H.; Beyer, M.; Grunstein, E.; Leonhardt, M.; Pongratz, H.; Eichhorn, E.; Elz, S.; Striegl, B.; Jenei-Lanzl, Z.; et al. Marbostat-100 Defines a New Class of Potent and Selective Antiinflammatory and Antirheumatic Histone Deacetylase 6 Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3454–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, O.P.; Ranganna, K.; Yatsu, F.M. Butyrate, an HDAC inhibitor, stimulates interplay between different posttranslational modifications of histone H3 and differently alters G1-specific cell cycle proteins in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2010, 64, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhak, Y.; Liddie, S.; Anderson, K.L. Sodium butyrate-induced histone acetylation strengthens the expression of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2013, 102, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, E.L.; Leonel, A.J.; Sad, A.P.; Beltrao, N.R.; Costa, T.F.; Ferreira, T.M.; Gomes-Santos, A.C.; Faria, A.M.; Peluzio, M.C.; Cara, D.C.; et al. Oral administration of sodium butyrate attenuates inflammation and mucosal lesion in experimental acute ulcerative colitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Béguet-Crespel, F.; Marinelli, L.; Jamet, A.; Ledue, F.; Blottière, H.M.; Lapaque, N. Butyrate produced by gut commensal bacteria activates TGF-beta1 expression through the transcription factor SP1 in human intestinal epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byndloss, M.X.; Olsan, E.E.; Rivera-Chavez, F.; Tiffany, C.R.; Cevallos, S.A.; Lokken, K.L.; Torres, T.P.; Byndloss, A.J.; Faber, F.; Gao, Y.; et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science 2017, 357, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichane, S.; Dahal Lamichane, B.; Kwon, S.-M. Pivotal roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and their signal cascade for cellular and whole-body energy homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; Gerding, A.; van Dijk, T.H.; Ciapaite, J.; Bleeker, A.; van Eunen, K.; Havinga, R.; Groen, A.K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. Protection against the Metabolic Syndrome by Guar Gum-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Depends on Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athman, R.; Philpott, D. Innate immunity via Toll-like receptors and Nod proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Boyso, J.; Bravo-Patiño, A.; Baizabal-Aguirre, V.M. Collaborative action of Toll-like and NOD-like receptors as modulators of the inflammatory response to pathogenic bacteria. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Mazmanian, S.K. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosis. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultani, M.; Stringer, A.M.; Bowen, J.M.; Gibson, R.J. Anti-inflammatory cytokines: Important immunoregulatory factors contributing to chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal mucositis. Chemother. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 490804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraporda, C.; Errea, A.; Romanin, D.E.; Cayet, D.; Pereyra, E.; Pignataro, O.; Sirard, J.C.; Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G.; Rumbo, M. Lactate and short chain fatty acids produced by microbial fermentation downregulate proinflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells and myeloid cells. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Hong, N.; Yu, C. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii upregulates regulatory T cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines in treating TNBS-induced colitis. J. Crohns. Colitis 2013, 7, e558–e568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, A.W.; Knolle, P.A. Antigen-presenting cell function in the tolerogenic liver environment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowat, A.M.; Agace, W.W. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Asmar, R.; Panigrahi, P.; Bamford, P.; Berti, I.; Not, T.; Coppa, G.V.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reikvam, D.H.; Erofeev, A.; Sandvik, A.; Grcic, V.; Jahnsen, F.L.; Gaustad, P.; McCoy, K.D.; Macpherson, A.J.; Meza-Zepeda, L.A.; Johansen, F.E. Depletion of murine intestinal microbiota: Effects on gut mucosa and epithelial gene expression. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullender, T.C.; Chassaing, B.; Janzon, A.; Kumar, K.; Muller, C.E.; Werner, J.J.; Angenent, L.T.; Bell, M.E.; Hay, A.G.; Peterson, D.A.; et al. Innate and adaptive immunity interact to quench microbiome flagellar motility in the gut. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, S.M.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; McSorley, S.J. CD103-CD11b+ dendritic cells regulate the sensitivity of CD4 T-cell responses to bacterial flagellin. Mucosal. Immunol. 2014, 7, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.D.; Leaphart, C.; Levy, R.; Prince, J.; Billiar, T.R.; Watkins, S.; Li, J.; Cetin, S.; Ford, H.; Schreiber, A.; et al. Enterocyte TLR4 mediates phagocytosis and translocation of bacteria across the intestinal barrier. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 3070–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, M.; Tsujibe, S.; Kiyoshima-Shibata, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Kato-Nagaoka, N.; Shida, K.; Matsumoto, S. Microbiota of the small intestine is selectively engulfed by phagocytes of the lamina propria and Peyer’s patches. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerren, J.R.; He, H.; Genovese, K.; Kogut, M.H. Expression of the avian-specific toll-like receptor 15 in chicken heterophils is mediated by gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, but not TLR agonists. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2010, 136, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garate, I.; Garcia-Bueno, B.; Madrigal, J.L.; Bravo, L.; Berrocoso, E.; Caso, J.R.; Mico, J.A.; Leza, J.C. Origin and consequences of brain Toll-like receptor 4 pathway stimulation in an experimental model of depression. J. Neuroinflamm. 2011, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, M. Structural modifications of bacterial lipopolysaccharide that facilitate gram-negative bacteria evasion of host innate immunity. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cress, B.F.; Englaender, J.A.; He, W.; Kasper, D.; Linhardt, R.J.; Koffas, M.A. Masquerading microbial pathogens: Capsular polysaccharides mimic host-tissue molecules. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 660–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostov, K.E. Transepithelial transport of immunoglobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.C.; Hoffmann, C.; Mota, J.F. The human gut microbiota: Metabolism and perspective in obesity. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.I.; Sansonetti, P.J. Shigella interaction with intestinal epithelial cells determines the innate immune response in shigellosis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 293, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corthésy, B.; Benureau, Y.; Perrier, C.; Fourgeux, C.; Parez, N.; Greenberg, H.; Schwartz-Cornil, I. Rotavirus anti-VP6 secretory immunoglobulin A contributes to protection via intracellular neutralization but not via immune exclusion. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 10692–10699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantis, N.J.; Cheung, M.C.; Chintalacharuvu, K.R.; Rey, J.; Corthesy, B.; Neutra, M.R. Selective adherence of IgA to murine Peyer’s patch M cells: Evidence for a novel IgA receptor. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macpherson, A.J.; Uhr, T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1662–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaoui, K.A.; Corthesy, B. Secretory IgA mediates bacterial translocation to dendritic cells in mouse Peyer’s patches with restriction to mucosal compartment. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 7751–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boullier, S.; Tanguy, M.; Kadaoui, K.A.; Caubet, C.; Sansonetti, P.; Corthesy, B.; Phalipon, A. Secretory IgA-mediated neutralization of Shigella flexneri prevents intestinal tissue destruction by down-regulating inflammatory circuits. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 5879–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.I.; Honda, K. Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.P.; Hawrelak, J. The causes of intestinal dysbiosis: A review. Altern. Med. Rev. 2004, 9, 180–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Yao, M.; Lv, L.; Ling, Z.; Li, L. The human microbiota in health and disease. Engineering 2017, 3, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.C.; Hughes, E.R.; Spiga, L.; Winter, M.G.; Zhu, W.; de Carvalho, T.F.; Chanin, R.B.; Behrendt, C.L.; Hooper, L.V.; Santos, R.L. Dysbiosis-associated change in host metabolism generates lactate to support Salmonella growth. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 54–64.e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiewicz, M.M.; Zirnheld, A.L.; Alard, P. Gut microbiota, immunity, and disease: A complex relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.L.; Hong, B.Y. Dysbiosis and Immune Dysregulation in Outer Space. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 35, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.A.; Ivey, K.L.; Papanicolas, L.E.; Best, K.P.; Muhlhausler, B.S.; Rogers, G.B. DNA extraction approaches substantially influence the assessment of the human breast milk microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, J.R.; Sartor, R.B. The role of diet on intestinal microbiota metabolism: Downstream impacts on host immune function and health, and therapeutic implications. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Decreased Diversity of the Oral Microbiota of Patients with Hepatitis B Virus-Induced Chronic Liver Disease: A Pilot Project. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; Lv, T.; Shen, P.; Lv, L.; Zheng, B.; Jiang, X.; Li, L. Identification of key taxa that favor intestinal colonization of Clostridium difficile in an adult Chinese population. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Cani, P.D. Diabetes, obesity and gut microbiota. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, L.; Giorgio, V.; Alberelli, M.A.; De Candia, E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Grieco, A. Impact of Gut Microbiota on Obesity, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2015, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, Y.; Santacruz, A.; Gauffin, P. Gut microbiota in obesity and metabolic disorders. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhong, S.L.; Feng, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, S.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Graham, T.E.; Mody, N.; Preitner, F.; Peroni, O.D.; Zabolotny, J.M.; Kotani, K.; Quadro, L.; Kahn, B.B. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2005, 436, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Czech, M.P. The GLUT4 glucose transporter. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Maianu, L.; Zhu, J.-H.; Brechtel-Hook, G.; Wallace, P.; Baron, A.D. Evidence for defects in the trafficking and translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters in skeletal muscle as a cause of human insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luca, C.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krssak, M.; Roden, M. The role of lipid accumulation in liver and muscle for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2004, 5, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snel, M.; Jonker, J.T.; Schoones, J.; Lamb, H.; de Roos, A.; Pijl, H.; Smit, J.W.; Meinders, A.E.; Jazet, I.M. Ectopic fat and insulin resistance: Pathophysiology and effect of diet and lifestyle interventions. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 2012, 983814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, J.; Arai, S.; Nakashima, K.; Nagano, H.; Nishijima, A.; Miyata, K.; Ose, R.; Mori, M.; Kubota, N.; Kadowaki, T. Macrophage-derived AIM is endocytosed into adipocytes and decreases lipid droplets via inhibition of fatty acid synthase activity. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampidonis, A.D.; Rogdakis, E.; Voutsinas, G.E.; Stravopodis, D.J. The resurgence of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL) in mammalian lipolysis. Gene 2011, 477, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 2001, 414, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassing, A.; Dowd, S.E.; Galandiuk, S.; Davis, B.; Chiodini, R.J. Inherent bacterial DNA contamination of extraction and sequencing reagents may affect interpretation of microbiota in low bacterial biomass samples. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Koeth, R.A.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, S.S. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Present Status and Future Perspectives on Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2016, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Derrien, M.; Rocher, E.; van-Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.; Strissel, K.; Zhao, L.; Obin, M.; et al. Modulation of gut microbiota during probiotic-mediated attenuation of metabolic syndrome in high fat diet-fed mice. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.; Vogensen, F.K.; van den Berg, F.W.; Nielsen, D.S.; Andreasen, A.S.; Pedersen, B.K.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Sorensen, S.J.; Hansen, L.H.; Jakobsen, M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, J.; Burcelin, R.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Cani, P.D.; Fauvel, J.; Alessi, M.C.; Chamontin, B.; Ferriéres, J. Energy intake is associated with endotoxemia in apparently healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.C.; Yeh, W.C.; Ohashi, P.S. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine 2008, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, K.; de Vos, P.; Priebe, M.G. Butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids as modulators of immunity: What relevance for health? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2010, 13, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, D.J.; Nauck, M.A. The incretin system: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2006, 368, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, H.; Lee, J.H.; Lloyd, J.; Walter, P.; Rane, S.G. Beneficial metabolic effects of a probiotic via butyrate-induced GLP-1 hormone secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25088–25097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjursell, M.; Admyre, T.; Goransson, M.; Marley, A.E.; Smith, D.M.; Oscarsson, J.; Bohlooly, Y.M. Improved glucose control and reduced body fat mass in free fatty acid receptor 2-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 300, E211–E220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]