Abstract

Background: Although facility-based cancer rehabilitation and exercise programs exist, patients are often unable to attend due to distance, cost, and other competing obligations. There is a need for scalable remote interventions that can reach and serve a larger population. Methods: We conducted a mixed methods pilot study to assess the feasibility, acceptability and impact of CaRE@Home: an 8-week online multidimensional cancer rehabilitation and exercise program. Feasibility and acceptability data were captured by attendance and adherence metrics and through qualitative interviews. Preliminary estimates of the effects of CaRE@Home on patient-reported and physically measured outcomes were calculated. Results: A total of n = 35 participated in the study. Recruitment (64%), retention (83%), and adherence (80%) rates, along with qualitative findings, support the feasibility of the CaRE@Home intervention. Acceptability was also high, and participants provided useful feedback for program improvements. Disability (WHODAS 2.0) scores significantly decreased from baseline (T1) to immediately post-intervention (T2) and three months post-intervention (T3) (p = 0.03 and p = 0.008). Physical activity (GSLTPAQ) levels significantly increased for both Total LSI (p = 0.007 and p = 0.0002) and moderate to strenuous LSI (p = 0.003 and p = 0.002) from baseline to T2 and T3. Work productivity (iPCQ) increased from T1 to T3 (p = 0.026). There was a significant increase in six minute walk distance from baseline to T2 and T3 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.010) and in grip strength from baseline to T2 and T3 (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001). Conclusions: Results indicate that the CaRE@Home program is a feasible and acceptable cancer rehabilitation program that may help cancer survivors regain functional ability and decrease disability. In order to confirm these findings, a controlled trial is required.

1. Introduction

Due to advances in early detection and biomedical treatment, over two-thirds of people who are diagnosed with invasive cancer will become long-term survivors [1,2]. Cancer survivors have unique post-treatment needs and face multiple physical, functional, and psychosocial challenges as they transition back to their lives [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Cancer rehabilitation is an essential component of survivorship care and has become increasingly relevant as the number of cancer survivors grows, coupled with the high documented rates of physical impairment and disability [9,10,11,12]. Comprehensive cancer rehabilitation focuses on prevention and treatment of immediate, persistent, or late effects of cancer and treatment, and the maintenance of health to optimize functional status and quality of life (QoL) [11,13,14]. Embedding cancer rehabilitation as a standard part of cancer care has the potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden on the healthcare system [9]. For patients with complex rehabilitation needs, a personalized, coordinated multidisciplinary approach is required to decrease disability and achieve improvements in physical functioning and overall QoL.

To date, the evidence on cancer rehabilitation is derived largely from trials utilizing face-to-face delivery in a clinical setting [9,14]. However, notwithstanding the advantages of facility-based supervised interventions [15], cancer survivors face significant barriers (e.g., time, work, remote home locations, cost, poor health) that can prevent access to cancer rehabilitation services delivered in medical facilities. Many cancer survivors prefer distanced-based interventions because of removed costs and travel to a medical facility, and the ability to accommodate competing commitments [16]. The rapid growth of eHealth technology has led to the development of new applications that can enable health care providers to monitor, treat, educate and support patients in their own homes. Telerehabilitation interventions that harness current and emerging technologies have been suggested as one mechanism that can reduce some barriers to accessing and providing rehabilitation [17,18]. This approach can allow for cost effective disease management and health promotion and is well established in other chronic disease populations such as heart disease and diabetes [19,20,21,22,23]. Specific to cancer survivors, eHealth technology presents opportunities to increase access to cancer rehabilitation in a virtual setting [24] and has shown promise in increasing physical activity [25,26] and reducing specific psychosocial and physical symptoms [27,28,29,30,31,32]. In one recent study, Cheville and colleagues [33] assessed the effect of a telerehabilitation intervention (including remote monitoring of symptoms and an individualized physical conditioning program) on function in patients with advanced cancer and found that the intervention improved function and pain, and decreased hospital length of stay and the requirement for post-acute care. However, impairment-driven multidimensional cancer telerehabilitation interventions have yet to be developed and evaluated for their feasibility, acceptability, and impact. Research on the development and impact of cancer telerehabilitation is urgently needed and should include feedback from patients to improve the quality of the rehabilitation itself [23].

We recently developed and implemented a virtual 8-week impairment-driven multidimensional Cancer Rehabilitation and Exercise program (CaRE@Home) with the aim to restore and optimize function and well being in those with identified cancer-related impairments. The aim of this mixed-methods pilot study was to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary impact of the CaRE@Home program.

2. Methods

We conducted a single-arm explanatory sequential mixed methods pre-post-assessment of the CaRE@Home program in cancer survivors with moderate-high disability at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto Canada. The research aims were to assess: (1) feasibility; (2) acceptability; and (3) to gain a preliminary estimate of the effects on disability (primary outcome), physical symptoms, social functioning, distress, physical activity, work function, and physiological factors. Outcomes were assessed at baseline (T1), immediately post-8 week intervention (T2) and 3 months post-intervention (T3). A sub-sample of participants were invited to take part in a post-intervention (T3) qualitative interview to explore participant experience of the program and gather feedback. The study was approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board, with participants providing written informed consent.

2.1. Intervention

The Cancer Rehabilitation and Survivorship (CRS) Program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre provides impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation to patients during and after acute cancer treatment with the goal to minimize disability and maximize functional independence. As part of its programming, CRS offers an innovative and effective in-person 8-week structured group multidimensional program, which is delivered at the Centre for Health Wellness and Cancer Survivorship (ELLICSR) at the Toronto General Hospital. This in-person group program, Cancer Rehabilitation, and Exercise (CaRE@ELLICSR), consists of weekly group exercise classes and self-management skills education delivered by CRS rehabilitation experts. Data collected on the in-person CaRE@ELLICSR intervention have demonstrated significant improvements in disability, social functioning, distress, and physical activity, and extremely high ratings of participant satisfaction [34]. However, ~40% of referred patients decline participation due to travel time, transportation costs, or competing obligations. In response, in collaboration with the Princess Margaret Educational Design & Knowledge Translation program and using a series of iterative steps proposed by the NCI Research-Tested Intervention Programs (NCI 2019), we adapted the CaRE@ELLICSR program so that it could be delivered through a virtual platform (CaRE@Home).

CaRE@Home is an 8-week program comprised of: (1) individualized progressive exercise prescription supported with a mobile application (Physitrack®) and wearable technology (Fitbit™) to track activity; (2) weekly e-modules providing interactive education to promote self-management skills; and (3) weekly brief telephone health coaching provided by health professionals (e.g., kinesiologists) trained in motivational interviewing. Informed by behavior change theory, the program components aim to provide patients with the knowledge and tools needed to reach and maintain their wellness and exercise goals (see Table 1 for list of embedded behavior change techniques and tools [35]). Multiple theoretical models are integrated within our intervention (i.e., motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy, theory of planned behavior), with the focus on addressing and resolving motivational ambivalence and identification and modification of the cognitive distortions that prevent adoption of appropriate health behaviors and addresses relapse and long term maintenance of behavior change [36,37,38,39,40,41]. The program is free to participants, other than out of pocket travel costs (i.e., public transport, parking) for in-hospital assessments.

Table 1.

Behavior Change elements and tools for CaRE @ Home.

- Exercise prescription, Physitrack® and Fitbit™: Prior to beginning the program, participants underwent an in-person fitness assessment conducted by a registered kinesiologist (RKin). Based on this assessment, an individualized exercise prescription was developed and progressed towards the ACSM guidelines of 150 min per week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise, 2 to 3 days of resistance training, and routine large muscle group flexibility training [42,43]. (Updated guidelines were published in 2019.) The individualized exercise prescription was then entered by the RKin into Physitrack®, an online platform that allows customizable exercise prescriptions, tracking of exercise completion, and video tutorials to support the prescribed exercises. In addition, participants were provided with a Fitbit™ device, which serves as a self-monitoring tool and provides further assistance to participants in adhering to recommended physical activity routines and tracking physical activity. Data from the device was also used as a weekly monitoring tool by the health care professionals. The participants were provided with an orientation to the Physitrack® application and Fitbit™ device during their initial in-person fitness assessment.

- E-Learning Modules: Participants were registered into an online learning platform and completed 8 comprehensive self-management e-modules. Modules were locked, meaning they had to complete the prior week before unlocking the next, and took approximately 20–45 min to complete. These modules included: Week 1: Getting Started—Set Your Goals; Week 2: Eat and Cook for Wellness; Week 3: Reduce Fatigue; Week 4: Manage your Emotions; Week 5: Be Mindful; Week 6: Improving Cancer-related Brain Fog and Boosting Your Brain Health; Week 7: Find Ways to Connect and Week 8: Plan for the Future. The topics chosen were based on patient-reported needs and commonly presenting symptoms. The content was developed by a multidisciplinary cancer rehabilitation team, including occupational therapy, physiotherapy, dietetics, neurocognitive psychology, social work, kinesiology, physiatry, and also included behavioral scientists. The modules included health literate design features such as linear navigation, intuitive buttons, and plain language and underwent two rounds of usability testing prior to the launch of the program. Attention was placed on behavior change techniques, ensuring that the interactive elements strengthened any behavior change goals.

- Telephone Health coaching: Participants received one weekly health coaching call with the same health coach in weeks 2–7 (6 total) plus one maintenance call at 1 month and one last call at 2 months post-intervention. Calls were scheduled for 20 min. Coaches were either a RKin or social worker trained in behavioral change and utilizing motivational interviewing skills. They guided participants to reflect upon their last week, plan goals for the week ahead, and identify barriers and solutions in achieving their goals and incorporated assessment and enhancement of motivation, promotion of self-efficacy, and collaborative problem solving. The objective was to enhance sustained behavior change by integrating several active ingredients outlined in the cancer-survivor behavior change literature [44,45] and motivational interviewing (MI) [36]. MI is a collaborative counseling method that elicits and strengthens motivation for change by addressing and resolving ambivalence [46] and has been shown to be effective in increasing physical activity in cancer survivors and those with other chronic conditions [47,48,49,50,51,52]. Health coaches were trained in motivational interviewing and supervised by a certified Motivational Interviewing Network Trainer who was part of the team (MO).

2.2. Participants and Procedure

Potential participants were recruited from the CRS program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and identified during their initial comprehensive rehabilitation assessment with a physiatrist and an occupational or physical therapist. Participants who met inclusion criteria were given an information pamphlet describing the program, as well as a patient agreement form that detailed both patient and health care provider responsibilities and expectations. Eligibility criteria included: age ≥ 18 years; received clearance by the CRS physiatrist to participate in exercise; expressed comfort using technology; ability to attend the in-person initial, 8 week, and 3 month follow-up assessments; fluency and/or comfort with the English language. Participants were excluded if they had acute medical needs that required a referral to another specialized service (i.e., Cancer Pain Program); had a planned surgery during the timeline of the study; presented with only mild impairments that could be managed by community partners; or had incurable cancer.

Eligible and interested patients were contacted by the CaRE intake coordinator to schedule their initial fitness assessment. At the initial fitness assessment, participants completed the questionnaire package using a tablet and then met with a team RKin for the fitness assessment. During the appointment, they were on-boarded onto the eLearning platform and Physitrack® application, provided with the FitbitTM, and weekly health coaching calls were scheduled. Consent was obtained at the baseline assessment. Participants also completed the questionnaire package and fitness assessment at the end of the 8-week program (T2) and 3 months later (T3). Qualitative interviews were conducted after T3 with a sub-sample of participants. Participants who had completed the 8-week program and had consented to be contacted for interview purposes were contacted by phone or email. Interviews were scheduled after participants had completed their 3-month follow-up assessment.

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

Basic demographic and clinical information were obtained by chart review at baseline and from the initial assessment questionnaire. Data included age, sex, marital status, employment status, time since diagnosis, and primary cancer location.

2.3.2. Feasibility and Acceptability

Feasibility of the intervention and methods were assessed by tracking the following: (1) Recruitment rates defined by the number of participants who completed an in-person baseline assessment compared to the number who were referred; (2) Retention rates took into account the patients who participated in the 8 week intervention and completed the follow-up assessments at 8 weeks and 3 months. (3) Adherence was examined by health coaching call attendance, Fitbit™ and Physitrack® usage, and e-module completion. To further assess feasibility and to evaluate acceptability and steer future program refinement, we conducted in-depth semi-structured qualitative telephone interviews with a sub-sample of participants following the T3 assessment. All interviews were conducted by the same person (BE), a trained qualitative methodologist. Interviews lasted between 20–45 min in length.

2.3.3. Exploratory Clinical Outcomes

Questionnaire and fitness assessment data were collected to measure the program’s effect on disability (primary outcome), symptom severity, physical activity, work function, and physiological factors (secondary outcomes). Data were collected at baseline (T1), immediately post-intervention (8 weeks, T2) and 3 months post-intervention (T3).

- Disability was measured using the 12-item World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO-DAS 2.0) [53,54]. Respondents rate their difficulty in engaging in particular activities on a scale from “none” (no difficulty) to “extreme or cannot do” on six domains of functioning. Scores range from 12 to 60, where higher scores indicate higher disability or loss of function. A WHODAS score of 0–4 is defined as none to mild disability and 5–48 is defined as moderate/high.

- Symptom Severity was measured with the widely used Edmonton Symptom Assessment Schedule revised (ESAS-r) [55,56]. The ESAS-r includes a simple 0–10 severity rating scale (0 being ‘symptom is absent’ and 10 being ‘worst possible severity’) for nine symptoms common in cancer patients: pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, wellbeing, and shortness of breath.

- Physical Activity was measured using the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (GSLTPAQ) [57]. The GSLTPAQ is a 3-item questionnaire that includes three questions on the number of times respondents engage in mild, moderate and strenuous leisure time physical activity (LTPA) bouts of at least 15 min duration in a typical week. Participants also report on the average minutes of each session for each intensity level. Examples of LTPA for each intensity category are provided. A Leisure Score Index (LSI) is calculated by taking the number of bouts at each intensity and multiplying by 3, 5, and 9 metabolic equivalents (METs) and then summing the score. In addition, moderate, and strenuous LTPA can be summed and used to categorize respondents as active and insufficiently active based on physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors.

- Work Function was assessed using two items from the iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iPCQ). Absenteeism was measured in numerical hours by asking participants: “During the past seven days, how many hours did you miss from work because of problems associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment?” Productivity was assessed by asking participants: “During the past seven days, how much did your cancer diagnosis and treatment affect your productivity while you were working?” with answers measured on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 = problem had no effect on my work and 10 = problem completely prevented me from working [58].

- Physiological measures were collected by the RKin during the in-person assessments and included aerobic capacity and endurance (6-min walk test) [59,60,61]; strength (grip strength) [62], and; cardiometabolic health (body mass index (BMI), resting heart rate and blood pressure).

2.4. Data Analysis

The target sample size for this pilot study (n = 30–40) was based on our primary aim to assess feasibility of the methods and acceptability of the intervention and is consistent with sample size recommendations for behavioral therapies research [63].

2.4.1. Feasibility and Acceptability

The proportion of patients who were referred to CaRE@Home and who enrolled into the program and provided consent (recruitment rate) and the attrition rates at each time point were calculated. Feasibility was assessed by calculating participant adherence to the 6 health coaching calls that took place during the 8-week intervention (weeks 2–7 inclusive), to the 8 weekly e-modules, and to Fitbit™ and Physitrack® usage.

Qualitative interviews were completed to assess feasibility and acceptability. A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on previous CaRE evaluation scripts and revised to address feasibility and acceptability issues specific to CaRE@Home (i.e., health coaching, technology, home-based exercises, online modules). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were first read multiple times in order to understand the participants’ perspectives and experiences. Our analysis began deductively, with a select number of categories pre-selected to align with the main program components—for example exercise prescription, educational modules, and health coaching calls. Acceptability categories were also pre-selected, namely program strengths, weaknesses, and areas of improvement. The transcripts were first annotated for these categories. Once this initial coding was complete, the interviews were then read once again, and codes were derived inductively, meaning that they were derived from the data and not preselected. Themes were generated by a close examination of codes and categories, and the relationships between them, and discussions with the research team. The main categories are related to the study objectives, were discussed consistently within an individual interview, as well as those that were discussed repeatedly between participant interviews. We sought to answer the questions of why the participants liked or disliked certain program components, how they engaged with the program, and in what ways the program impacted their lives [64]. Illustrative quotes were chosen based on their connection to these categories and themes, and whether they provided valuable insight for future program iterations. Recruitment for interviews was stopped once data saturation was reached and no new categories, codes, or themes were emerging.

2.4.2. Exploratory Clinical Outcomes

Demographic and clinical data were reported using descriptive statistics. Continuous data were reported as means with standard deviations and categorical data was reported as percentages. Statistical analyses were performed on data from the participants who completed baseline measures. For all exploratory clinical outcomes that are continuous in nature, estimated means at each time point were calculated and compared using linear mixed effects models. The proportion of patients with moderate to high disability (WHODAS 2.0) was examined across time points using GEE (Generalized Estimating Equations) procedures and the corresponding p-value was reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 or R version 3.5.1. Statistical significance is considered as p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of n = 35 participants enrolled in the study. Participant demographic data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics.

3.1. Feasibility

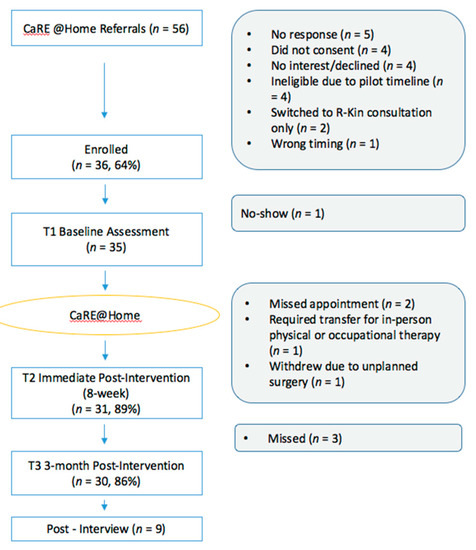

The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Recruitment took place between May 2019 and October 2019 during which time 56 patients were identified as eligible for CaRE@Home and referred for booking and 51 were successfully contacted by the CaRE coordinator. Of these, 5 patients declined participation since they were no longer interested in joining, 6 were deemed ineligible due to inability to attend the assessment appointments, and 4 did not provide consent to be part of the study. A total of 35/36 scheduled baseline assessments (T1) were completed, with one patient not showing up for the scheduled assessment. Thirty-one participants completed the 8 week T2 assessment, and 30 patients completed the T3 assessment at 3-month post-intervention. The recruitment rate was 64% (36/56) and retention rate was 83% (30/36).

Figure 1.

Program flow.

Feasibility was also measured by measuring adherence to health coaching calls, FitbitTM and Physitrack® usage, and e-module completion. Participants were pre-scheduled for 6 health coaching calls during weeks 2–7 of the 8-week intervention (inclusive). Call adherence ranged from 1–6 calls with an average of 5 calls. A total of 17/35 (49%) participants completed all six calls, with 28/35 (80%) participants completing at least 5 calls. Following the 8-week program, participants had two maintenance calls at 1 month and 2-months post-intervention. Twenty-five calls (71%) were completed at the 1-month mark and twenty-nine calls (83%) were completed at the 2-month mark. FitbitTM usage was measured as the percentage of days that the device was worn throughout the 8-week intervention (total intervention length ranged from 53 to 65 days due to scheduling variability for T2 assessment). In total, 30/35 (86%) participants received and wore the device. Some participants did not want the FitbitTM since they already had their own device (n = 3). Login details were missing or changed for 2 participants and as such FitbitTM data could not be downloaded for them. Of those who received the device and for whom login information was available, the device was worn for 23%–100% of the intervention days, with a mean of 87% of the intervention days. Thirty-one participants (89%) logged into the Physitrack® app at least once throughout the intervention. Adherence to the e-modules was measured by the completion rate of the 8 weekly e-modules. Twenty-seven of the 35 participants logged into the online learning portal (77%) at least once, while 7 participants never logged on at all. Module adherence ranged from 0–8 modules, with a mean of 4 modules completed, and a mode of 0 or 6 modules completed by 5 participants. Participants were most likely to complete the first module (22/27; 81.5%), with a weekly drop-off occurring thereafter, and only 4/27 (14.8%) completed the final eighth module.

Data from the qualitative interviews (n = 9) were analyzed for feasibility issues. A sample of 10 participants who completed their 3-month follow up assessment was selected for qualitative interviews. Nine interviews were scheduled and completed during the pilot study. The findings suggest that some aspects of the program structure were well received and reasonable for our patient population. Participants also identified areas of improvement (see Table 3). Most participants found the program to be well organized and structured to suit their needs. They appreciated the remote program nature but also valued the weekly check-ins with the health care professional. They found the program to be flexible and convenient and liked being able to complete the program from the comfort of their home. Others spoke of the benefit of not having to be a part of a group setting, where they often felt uncomfortable. Some participants shared that the program length and follow-up frequency were appropriate, whereas others shared that the program could have been longer. Lastly, a few participants talked about how they would have preferred more time to complete the e-modules or the ability to have all modules be unlocked (vs. a prescribed weekly order).

Table 3.

Qualitative Table for Feasibility.

3.2. Acceptability

Data from the qualitative interviews, were analyzed to assess acceptability. Three key categories emerged. These included overall satisfaction with program and program elements, benefits of the program, and areas for improvement. A summary of these categories is presented below. A detailed description of each of these categories, along with illustrative quotes, is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Qualitative Table for Acceptability.

3.2.1. Overall Satisfaction with CaRE@Home Program

The participants who were interviewed expressed that they felt grateful to have taken part in the program and appreciated the support it provided. Participants saw a need for such rehabilitation programs since acute oncology care was often focused on medical needs whereas this program was more holistic in nature. Feedback from the interviews highlighted that the health coaching calls were a valuable program component that encouraged accountability and provided an appreciated human touch element and support during a time when they often felt alone. The interview findings support the use of technology as an add-on monitoring and motivational tool. The FitbitTM device was viewed as a valuable self-monitoring tool that motivated participants to move and achieve their target steps and target heart rates. The Physitrack® software enabled patients to have an accessible and visual reminder of their exercise prescription.

3.2.2. Benefits of the Program

Participants spoke about the benefits of the CaRE@Home program including their ability to self-manage their emotions and exercise. Participants spoke about the positive impact of the educational content provided by the e-modules and appreciated the focus on self-care. Many talked about gaining a new appreciation for exercise. Participants also indicated they were able to gain insight and skills on mindfulness and better manage their emotions. As a result of the program, some participants felt that they were better able to accept their diagnosis and the emotions surrounding it.

3.2.3. Areas for Program Improvement

Some participants provided suggestions for improvements to the program. For example, participants had mixed feelings towards the weekly e-modules. While they enjoyed the educational curriculum and found the material to be timely and appropriate, some felt they were too long. In some cases, even though the health coaches would remind participants to complete their modules, participants said they didn’t have enough time to do so. Others expressed that they would have liked to have more time to digest the weekly learnings before moving on and would prefer to be able to pace themselves through the e-modules. A few participants appeared to be more focused on their exercise component of the intervention and less so on the e-module offering. Participants valued the in-person assessments, but some had difficulty travelling to downtown Toronto to attend these visits and suggested that there be a train-the-trainer model with more remote kinesiologists available to perform the assessments in their community. In addition, participants enjoyed connecting with the kinesiologist, and suggested that some of the phone appointments be done over video conferencing to allow for a more personal touch and also demonstration of the exercises. One participant suggested that there could be some specific programming or content created for the main caregiver at home who is supporting the patient.

3.3. Exploratory Clinical Outcomes

Preliminary estimates of the treatment effects for participants on disability (primary), symptom severity, physical activity and work status were evaluated (Table 5). WHODAS 2.0 disability scores significantly decreased from baseline to T2 and T3 (p = 0.03 and p = 0.008). Further, the proportion of participants reporting moderate/high levels of disability decreased from 75.8% at baseline to 50% at T3 (p = 0.039). There were no differences observed from baseline to T2 or T3 for any of the symptom severity (ESAS) measures. The GODIN-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire revealed a significant increase in Total LSI (p = 0.007 and p = 0.0002) and moderate to strenuous LSI (p = 0.003 and p = 0.002) from T1 to T2 and T3. Finally, there was an improvement in productivity with a significant decrease in WS6 productivity scores (During the past seven days, how much did your cancer diagnosis and treatment affect your productivity while you were working?) from T1 to T3 (p = 0.026). There seems to be a decreasing pattern in WS3 absenteeism scores (During the past seven days, how many hours did you miss from work because of problems associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment) from baseline to T2 and T3, but it did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5.

Patient-Reported outcomes (PRO’s).

In addition, preliminary estimates of the treatment effects on physiological outcomes were evaluated (Table 6) There was a significant increase in six-minute walk distance from baseline to T2 and T3 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.010) and in grip strength from baseline to T2 and T3 (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001). No differences were observed from baseline to T2 or T3 for heart rate, diastolic or systolic blood pressure, or BMI.

Table 6.

Physiological Outcomes.

4. Discussion

This pilot study generated valuable findings regarding the CaRE@Home intervention and suggests that its delivery and method of evaluation are feasible, and it is acceptable to participants. In addition, we found statistically significant improvement in disability scores at 3 months and also improvements in physical activity, work productivity, grip strength, and 6-min walk distance. The CaRE@Home intervention was innovative in that it was impairment-driven and included: (1) individualized progressive exercise prescription supported with a mobile application and wearable technology; (2) weekly e-modules providing interactive education to promote self-management skills; (3) weekly brief telephone health coaching with a member of the rehabilitation team; and (4) was informed by behavior change theory.

Overall, the CaRE@Home program was feasible with high rates of retention in the program. The 83% retention rate was extremely high given this type of intervention [65,66]. Participants enjoyed the flexibility that a remote program provided and appreciated the ability to only come into the hospital for select appointments and follow-ups. Participants particularly liked working directly with their assigned health coach and receiving custom exercise prescriptions tailored to their functional abilities. They also found the weekly health coaching calls very helpful, noting that the support and accountability motivated them to engage with the program and complete their exercise prescriptions. This finding is supported by other research, which has shown that having external accountability is an important facilitator to behavior change [67]. Telerehabilitation has been shown to strengthen the patient-health-care provider connection by enhancing the provider’s knowledge of the patient and their contextual factors, providing ongoing information exchange and facilitating education, and establishing shared goal setting and action planning [68].

The use of self-monitoring technology was a key factor that supported the participants’ adherence to the program. Use of both the Fitbit™ and Physitrack® application were extremely high. Participants appreciated the ability to have their custom exercise prescriptions updated on Physitrack® as their strength and functional abilities changed. Patients also found the Fitbit™ device to be motivating and to provide nudges to reach their daily goals. The use of self-monitoring devices such as the Fitbit™ device has been shown in multiple studies to motivate participants to take on healthy active behaviors, when paired with additional behavior change interventions [69,70,71,72]. Fitbits™ have been found to be especially beneficial when used in conjunction with other program elements [71]. Results from our pilot study also indicate that exercise-based oncology programs should consider including technological tools so as to provide effective and accessible options to a greater patient population. The use of technology may also make it easier for intervention-deliverers (exercise and rehab professionals) to prescribe exercise and monitor patients’ needs.

A Web-based educational curriculum is also an important behavior change element as it shapes knowledge through a highly accessible format [35]. Most of the pilot participants (22/27; 81.5%) engaged with the online content and completed at least the first module. However, participants completed an average of only 50% of the modules. We observed a significant drop-off occurring week to week with only 4/27 (14.8%) completing the last module in week 8 of the intervention. From the qualitative interviews we learned that many participants appreciated the value of the modules but did not prioritize their completion, and many felt they were too long and that they did not have sufficient time to invest in completing them. The modules were also prescribed weekly and locked, requiring the completion of the current module to unlock the next. Participants who fell behind did not have the option to skip ahead and may have found this prescriptive approach too difficult to manage or not meeting their needs or interest. Future iterations of the program will effectively “unlock” modules to allow for more flexibility and will include automated weekly email reminders to complete the e-modules (including the time required and the goals of the module).

Digital and remote program development is often iterative in its implementation [73]. Pilot studies, such as this one, are invaluable in generating acceptability data for future, larger scale trials. Our pilot findings support the acceptability of a remote cancer rehabilitation and exercise program, but also brought to light important areas for program improvements. Participants felt that this program should also be offered during treatment, as much of the content would have been beneficial. As mentioned above, some participants also suggested that all modules be readily available during the 8-week intervention, rather than have a prescribed weekly module. Suggestions were also made in regards to content; some participants suggested adding in content and support for the patient’s primary caregiver, something which has been known to be beneficial in other studies [74,75]. Others found the modules to be too long. Participants valued the in-person assessments and the health coaching calls so much so that they suggested having more video health coaching in order to improve the human touch element of the intervention. Lastly, some participants suggested a train-the-trainer model with remote kinesiologists who could perform the in-person assessments in the community, rather than have patients come to downtown Toronto.

Finally, while distance-based eHealth interventions have the potential to reduce disparities among cancer survivors and improve access [76,77] and the large majority of adults have access to the internet and smart phones [78,79], it is important to recognize that there are a number of cancer survivors who face barriers to accessing eHealth interventions. This may include those with cognitive difficulties, limited technological literacy, physical disabilities, and for whom English is not their first language. Given this, it is important to identify cancer survivors with particular needs when introducing health technology and to develop strategies to prevent leaving behind this substantial group of cancer survivors [80,81]. In the current study, only 64% of those who had been identified as potentially eligible for this program actually enrolled. It is important for clinicians to assess an individuals’ receptiveness to use technology within a rehabilitation context in order to tailor the interventions offered [81].

Study Limitations

Results from this pilot study need to be interpreted while acknowledging its limitations. To begin, while the sample size was appropriate for a pilot study, the impact of the program on clinical outcomes needs to be considered preliminarily. Further, as this was a one-arm study with no control condition, there may be other explanations for improved disability (e.g., elapsed time since treatment) that must be considered. Encouragingly, the qualitative results supported the quantitative findings. Secondly, follow up assessments were limited to 3 months post-intervention, which does not allow for the examination of the long-term impact of the intervention or maintenance of health behaviors. Intervention components may show greater impact after a longer duration and thus reporting of outcome measures at 6 and 12 months would make for more comprehensive results. In addition, while results from the qualitative study demonstrate a high degree of acceptability, it is important to note that the interviews were conducted with participants who completed the study; completing a mean of 4 modules (range of 0–8) and wore the FitbitTM for a mean of 84% of the intervention days. The perspectives of these individuals may not reflect the perspectives of those who did not complete the intervention, or of those who were less engaged with the e-modules and the FitbitTM device. It is also worth noting that we were unable to track specific usage of the Physitrack app (other than whether or not participants ever logged in) and so adherence to this aspect of the intervention is limited. Finally, safety incidents were not actively tracked in this pilot study, though none were noted, and should be considered in future trials.

5. Conclusions

This study provides important information on the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a virtual multicomponent cancer rehabilitation intervention for cancer survivors, thus addressing an important gap in the literature. High retention and positive outcomes at 3 months are encouraging indications of the potential success of the CaRE@Home intervention and these results support moving to a Phase III controlled trial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., L.J.B., E.C., D.M.L. and J.M.J.; Data curation, A.C., C.J.L., L.J.B., E.C., D.M.L., M.O., B.E. and J.M.J.; Formal analysis, A.M.M., C.J.L., M.M., B.E. and J.M.J.; Funding acquisition, J.M.J.; Investigation, A.M.M., A.C., C.J.L., B.E. and J.M.J.; Methodology, A.M.M., A.C., C.J.L., M.O. and B.E.; Project administration, A.C. and J.M.J.; Resources, M.O.; Supervision, A.C., E.C., P.O., J.L.B., S.M.A. and J.M.J.; Visualization, J.M.J.; Writing—original draft, A.M.M.; Writing—review & editing, A.M.M., A.C., C.J.L., L.J.B., E.C., D.M.L., B.E., P.O., J.L.B., S.M.A. and J.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from Cancer Care Ontario through funding provided by the Government of Ontario and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allemani, C.; Weir, H.K.; Carreira, H.; Harewood, R.; Spika, D.; Wang, X.-S.; Bannon, F.; Ahn, J.V.; Johnson, C.J.; Bonaventure, A.; et al. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: Analysis of individual data for 25 676 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet 2015, 385, 977–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Mph, K.D.M.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, K.E.; Forsythe, L.P.; Reeve, B.B.; Alfano, C.M.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Sabatino, S.A.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rowland, J.H. Mental and Physical Health-Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C.M.; Rowland, J.H. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: A new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J. 2006, 12, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, K.; Syrjala, K.; Andrykowski, M. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 2008, 112 (Suppl. S11), 2577–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.; Hansen, J.; Moskowitz, M.; Todd, B.; Feuerstein, M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010, 40, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.J.; McCreath, G.A.; Komeylian, Z.; Rich, J.B. Cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy depends on control group type and cognitive domains assessed: A multilevel meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Olson, K.; Catton, P.; Catton, C.N.; Fleshner, N.E.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; McCready, D.R.; Wong, R.K.S.; Jiang, H.; Howell, D. Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 10, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewes, J.C.; Steuten, L.M.G.; Ijzerman, M.; Van Harten, W.H. Effectiveness of Multidimensional Cancer Survivor Rehabilitation and Cost-Effectiveness of Cancer Rehabilitation in General: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, L.; Gjerset, G.M.; Loge, J.H.; Kiserud, C.E.; Skovlund, E.; Fløtten, T.; Fosså, S.D. Cancer patients’ needs for rehabilitation services. Acta Oncol. 2011, 50, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.K.; Baima, J.; Mayer, R.S. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: An essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheville, A. Adjunctive Rehabilitation Approaches to Oncology; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; Volume 28, pp. 1–215. [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, C.; Cheville, A.; Mustian, K. Developing High-Quality Cancer Rehabilitation Programs: A Timely Need. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. 2018, 36, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Mills, M.; Black, A.; Cantwell, M.; Campbell, A.; Cardwell, C.R.; Porter, S.; Donnelly, M. Multidimensional rehabilitation programmes for adult cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD007730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffart, L.; Kalter, J.; Sweegers, M.G.; Courneya, K.; Newton, R.U.; Aaronson, N.; Jacobsen, P.B.; May, A.M.; Galvão, D.A.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: An individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 52, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.N.; McAuley, E.; Trinh, L. Physical activity programming and counseling preferences among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, A.S.; Hefner, J.E.; Kodish-Wachs, J.E.; Iaccarino, M.A.; Paganoni, S. Telehealth in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. PMR 2017, 9, S51–S58. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Maxwell-Smith, C.; Kamarova, S.; Lamb, S.; Millar, L.; Cohen, P.A. Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalleck, L.C.; Schmidt, L.K.; Lueker, R. Cardiac rehabilitation outcomes in a conventional versus telemedicine-based programme. J. Telemed. Telecare 2011, 17, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, R. Twenty years of telemedicine in chronic disease management—An evidence synthesis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, P.; Daines, L.; Campbell, C.; McKinstry, B.; Weller, D.; Pinnock, H.; Kaufman, N.; Moy, M.; McLean, S.; Holtz, B. Telehealth Interventions to Support Self-Management of Long-Term Conditions: A Systematic Metareview of Diabetes, Heart Failure, Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeland, A.G.; Bowes, A.; Flottorp, S. Effectiveness of telemedicine: A systematic review of reviews. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 736–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretti, A.; Amenta, F.; Tayebati, S.; Nittari, G.; Mahdi, S.S. Telerehabilitation: Review of the State-of-the-Art and Areas of Application. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 4, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeh, S.; Abu Shanab, S.; Anabtawi, M. Augmented Reality Internet Labs versus its Traditional and Virtual Equivalence. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (iJET) 2015, 10, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorri, S.; Asadi, F.; Olfatbakhsh, A.; Kazemi, A. A Systematic Review of Electronic Health (eHealth) interventions to improve physical activity in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2019, 27, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, J.; Kelly, G.; Haberlin, C.; Mockler, D.; Broderick, J. The use of eHealth to promote physical activity in people with mental health conditions: A systematic review [version 3; peer review: 3 approved] Previously titled: The use of eHealth to promote physical activity in patients with mental health conditions: A systematic review. HRB Open Res. 2018, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Agboola, S.; Ju, W.; ElFiky, A.; Kvedar, J.C.; Jethwani, K.; Badger, T.; Nelson, E. The Effect of Technology-Based Interventions on Pain, Depression, and Quality of Life in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Klaas, V.; Tröster, G.; Fagundes, C.P. eHealth and mHealth interventions in the treatment of fatigued cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.J.; Buckingham, G.; Wilson, M.R.; Vine, S.J. Virtually the same? How impaired sensory information in virtual reality may disrupt vision for action. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksdottir, N.; Gunnarsdottir, S.; Zoëga, S.; Ingadottir, B.; Hafsteinsdottir, E.J.G. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: Review of randomized trials. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, K.E.; Flanagan, J. Web based survivorship interventions for women with breast cancer: An integrative review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 25, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, V.J.; Dhillon, H.M.; Bell, M.L.; Kabourakis, M.; Fiero, M.H.; Yip, D.; Boyle, F.; Price, M.A.; Vardy, J. Evaluation of a Web-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation Program in Cancer Survivors Reporting Cognitive Symptoms After Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheville, A.L.; Moynihan, T.; Herrin, J.; Loprinzi, C.; Kroenke, K. Effect of Collaborative Telerehabilitation on Functional Impairment and Pain Among Patients with Advanced-Stage Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Bernstein, L.; Chafranskaia, A.; Chang, E.; Langelier, D.; Hospod, A.-M.; Lopez, C.; Maganti, M.; Tan, V.; Mina, D.S. Cancer Rehabilitation and Exercise (CaRE): A multicomponent rehabilitation intervention for cancer survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2020, abstract in press. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.; Butler, C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. Theoretical foundations of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1996, 47, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlatt, G.A.; Gordon, J.R. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, G.A.; Anderson, B.K.; Marlatt, G.A. Relapse prevention therapy. In The Handbook of Alcohol Dependence and Problems; Heather, N., Peter, T., Stockwell, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Sussex, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, K.; Courneya, K.; Matthews, C.E.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Galvão, D.A.; Pinto, B.M.; Irwin, M.L.; Wolin, K.Y.; Segal, R.J.; Lucia, A.; et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable on Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1409–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Heal. Psychol. 2008, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Ashford, S.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Bishop, A.; French, D.P.; Williams, S.L. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: The CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Ten Things that Motivational Interviewing Is Not. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2009, 37, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, B.M.; Frierson, G.M.; Rabin, C.; Trunzo, J.J.; Marcus, B.H. Home-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Breast Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3577–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, B.W.; Kunz, C.; Brownell, C.; Tollefson, D.; Burke, B.L. A Meta-Analysis of Motivational Interviewing: Twenty-Five Years of Empirical Studies. Res. Soc. Work. Pr. 2010, 20, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöling, M.; Lundberg, K.; Englund, E.; Westman, A.; Jong, M.C. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing and physical activity on prescription on leisure exercise time in subjects suffering from mild to moderate hypertension. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.L.; Arkowitz, H.; Menchola, M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, D.A.; Inoue, A. Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Di Onofrio, V.; Miele, A.; Belfiore, P.; Liguori, G. Effects of a community-based exercise and motivational intervention on physical fitness of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 29, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, T.B.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Rehm, J.; Kennedy, C.; Epping-Jordan, J.; Saxena, S.; Von Korff, M.; Pull, C. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis, J.V.L.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Aguado, J.; Fernández, A.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Roca, M.; Haro, J.M. The 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II): A nonparametric item response analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A Simple Method for the Assessment of Palliative Care Patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, P.; Watanabe, S.; Taube, A. The Edmonton Staging System. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 1996, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard leisure-time physical activity questionnaire. Health Fit. J. Can. 2001, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmans, C.; Krol, M.; Severens, H.; Koopmanschap, M.; Brouwer, W.; Roijen, L.H.-V. The iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire. Value Health 2015, 18, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.; Solway, S.; Gibbons, W.J. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.P.; Awasthi, R.; Sweet, S.N.; Minnella, E.M.; Bergdahl, A.; Carli, F.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C.; Mina, D.S. Four-week prehabilitation program is sufficient to modify exercise behaviors and improve preoperative functional walking capacity in patients with colorectal cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 25, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.L.; Holland, A.; Gordon, I.R.; Denehy, L. Minimal important difference of the 6-minute walk distance in lung cancer. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2015, 12, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebe, D.; Ehrman, J.; Liguori, G.; Magal, M. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 10th ed.; Lippincott Williams and Wikins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, G.A.; Dodd, S.; Williamson, P.R. Design and analysis of pilot studies: Recommendations for good practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2004, 10, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, M.; Kennedy, K.; Singhal, A.; Martin, R.M.; Ness, A.R.; Hadders-Algra, M.; Koletzko, B.; Lucas, A. How much loss to follow-up is acceptable in long-term randomised trials and prospective studies? Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, L.M.; O’Hara, B.; Milat, A. Computer-tailored physical activity behavior change interventions targeting adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Galliott, M.; Lynch, B.M.; Nguyen, N.H.; Cohen, P.A.; Mohan, G.R.; Johansen, N.J.; Saunders, C. ‘If I Had Someone Looking Over My Shoulder…’: Exploration of Advice Received and Factors Influencing Physical Activity Among Non-metropolitan Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Blazer, D.; Hoenig, H. Can eHealth Technology Enhance the Patient-Provider Relationship in Rehabilitation? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gell, N.M.; Grover, K.W.; Humble, M.; Sexton, M.; Dittus, K. Efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of a novel technology-based intervention to support physical activity in cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 25, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R.; Kadokura, E.A.; Bouldin, E.D.; Miyawaki, C.E.; Higano, C.S.; Hartzler, A.L. Acceptability of Fitbit for physical activity tracking within clinical care among men with prostate cancer. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2017, 2016, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Vandelanotte, C.; Duncan, M.J.; Maher, C.; Schoeppe, S.; Rebar, A.L.; Power, D.A.; Short, C.E.; Doran, C.M.; Hayman, M.; Alley, S.J.; et al. The Effectiveness of a Web-Based Computer-Tailored Physical Activity Intervention Using Fitbit Activity Trackers: Randomized Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, N.M.; Grover, K.W.; Savard, L.; Dittus, K. Outcomes of a text message, Fitbit, and coaching intervention on physical activity maintenance among cancer survivors: A randomized control pilot trial. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 14, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummah, S.A.; Robinson, T.N.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D.; Sutton, S.; Munro, G.; Atienza, A.; Peeples, M. IDEAS (Integrate, Design, Assess, and Share): A Framework and Toolkit of Strategies for the Development of More Effective Digital Interventions to Change Health Behavior. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Cheng, T.; Jackman, M.; Walton, T.; Haines, S.; Rodin, G.M.; Catton, P. Getting back on track: Evaluation of a brief group psychoeducation intervention for women completing primary treatment for breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 22, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, R.; Bernstein, L.J.; Bilodeau, D.; Bovett, G.; Jackson, B.; Yousefi, M.; Prica, A.; Perry, J. Evaluation of an educational program for the caregivers of persons diagnosed with a malignant glioma. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2007, 17, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Lucas, G.; Marcu, A.; Piano, M.; Grosvenor, W.; Mold, F.; Maguire, R.; Ream, E.; Pensak, N.A.; Wen, K.-Y. Cancer Survivors’ Experience with Telehealth: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, B.D. Promise of Mobile Health Technology to Reduce Disparities in Patients with Cancer and Survivors. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2018, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics 2008. Available online: http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/About%20cancer/Cancer%20statistics/Canadian%20Cancer%20Statistics.aspx?sc_lang=en (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Pew Research Center. Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/06/13/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2019/ (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Nicklin, E.; Velikova, G.; Boele, F. Technology is the future, but who are we leaving behind? Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossen, S.; Kayser, L.; Vibe-Petersen, J.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Christensen, J. Technology in exercise-based cancer rehabilitation: A cross-sectional study of receptiveness and readiness for e-Health utilization in Danish cancer rehabilitation. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).