Abstract

Nonunions and fracture-related infections represent a significant complication in orthopedic and trauma care, with their incidence rising due to an aging, more comorbid global population and the escalating threat of multi-resistant pathogens. This narrative review highlights pivotal advancements in diagnostics and therapeutic approaches, while also providing an outlook on future directions. Diagnostic methodologies have significantly evolved from traditional cultures to sophisticated molecular techniques like metagenomic next-generation sequencing and advanced imaging. Simultaneously, therapeutic strategies have undergone substantial refinement, encompassing orthoplastic management for infected open fractures and the innovative application of antibiotic-loaded bone substitutes for local drug delivery. The effective integration of these possibilities into daily patient care critically depends on specialized centers. These institutions play an indispensable role in managing complex cases and fostering innovation. Despite considerable progress over the past 25 years, ongoing research, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to evidence-based practice remain crucial to transforming management for the future.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, healthcare has shifted from empiric to evidence-based medicine, fundamentally transforming clinical decision-making and patient care []. While clinical practice guidelines evolved in many areas, this transition has been particularly challenging in managing nonunions and fracture-related infections (FRI), a field characterized by complex and heterogeneous patient populations, varying pathogen spectra, and diverse treatment approaches [,,]. While significant scientific advancements have been made in understanding and treating these infections, some critical questions remain unanswered, leaving clinicians to navigate a landscape that still demands experience-driven intuition and rigorous scientific evaluation []. Musculoskeletal infections encompass a range of conditions, including fracture-related infections, osteomyelitis, and nonunions. Despite the distinct pathophysiology of fracture-related infections, osteomyelitis, and nonunions, these entities share several features: prolonged treatment courses, high rates of recurrence, and a substantial socioeconomic burden [,]. Over the past 25 years, significant strides have been made in refining diagnostic criteria, optimizing surgical and antimicrobial strategies, and developing novel biomaterials to improve patient outcomes.

Recent data suggest nonunions occur in 2–5% of fractures, while FRIs complicate 1–2% of closed cases but can exceed 30% in severe open injuries [,,]. These rates vary globally, and a significant data shortage exists for low- and middle-income countries, which carry a disproportionately high trauma burden and risk of complications. Furthermore, individual risk factors such as smoking and diabetes significantly increase a patient’s susceptibility to poor healing outcomes. One of the most challenging aspects is the early and accurate diagnosis of infection. Laboratory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell count have long been used as indicators. Still, their sensitivity and specificity remain limited, particularly in patients with chronic infections or underlying inflammatory conditions []. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics, imaging, and biomarker research have provided promising new tools for the more precise and earlier detection of nonunions and FRIs; however, their routine clinical application is still evolving. These developments will be discussed in detail in Section 2 of this review.

Another primary research focus has been refining surgical techniques and implant-related infection prevention. Radical debridement remains the cornerstone of surgical management, as necrotic bone serves as a persistent nidus for infection, impairing the effectiveness of systemic antibiotic therapy [,]. The increasing implementation of orthoplastic approaches, particularly in treating infected open fractures, has significantly improved functional outcomes by integrating soft tissue and bone reconstruction in a single-stage or multi-stage concept. The principles and current best practices of this approach will be explored in Section 3.

Despite advances in surgical methods, targeted antimicrobial therapy is pivotal in infection control. Historically, antibiotic-loaded cement spacers and microbiologically tailored systemic antibiotics have formed the cornerstone of treatment. However, antibiotic-loaded bone substitutes have emerged as a promising adjunct to systemic therapy. These biomaterials provide structural support and osteoconductive benefits while achieving high local antibiotic concentrations, thereby reducing the risk of reinfection and limiting systemic toxicity [,]. Section 4 will analyze the latest developments in biomaterial-based antimicrobial strategies for treating FRIs or nonunions.

In addition to these advancements, the role of highly specialized centers in managing complex musculoskeletal infections has become increasingly relevant. In Germany, BG Kliniken (the Group of Hospitals of the Federal Social Accident Insurance, DGUV) play a crucial role in handling these challenging cases, serving as national referral and international collaborating centers. Their expertise and impact on patient outcomes are discussed in the final Section 5.

While the past 25 years have brought remarkable progress in understanding nonunions and fracture-related infections, the topic remains dynamic, with ongoing research continuously shaping clinical practice. This review provides an evidence-informed synthesis of these developments, prioritizing consensus definitions and guidelines, high-quality reviews, and landmark clinical studies from the last quarter-century. It summarizes key advancements, highlights persistent challenges, and explores the emerging concepts that will define the next era of managing nonunions and fracture-related infections.

2. Diagnostic Challenges and Advances in Nonunions and Fracture-Related Infections

Musculoskeletal infections encompass a broad spectrum of diseases, including fracture-related infections, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis as well as periprosthetic joint infections. All conditions significantly impact patient morbidity, length of hospitalization, and healthcare costs. The insidious nature of many of these infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals (e.g., patients with diabetes mellitus) or those with indwelling metallic or composite orthopedic implants, makes early detection both critical and challenging. Inadequate or delayed diagnosis can result in persistent infection, mechanical failure of prostheses or osteosynthesis hardware, bone and soft tissue defects, and, in severe cases, limb loss or mortality.

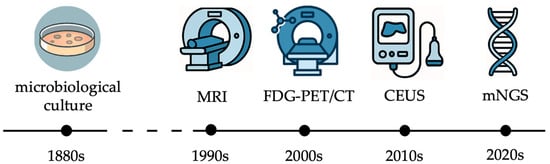

Over the last decades, clinicians and researchers have made substantial progress in understanding the pathogenesis of nonunions and FRI, the role of biofilms, and immune evasion mechanisms. Concurrently, diagnostic technologies have evolved, shifting from culture-based methods to molecular assays, immunodiagnostic biomarkers, and advanced imaging (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Milestones in the diagnosis of nonunions and fracture-related infections during the last half century (MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FDG-PET/CT: fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography; CEUS: contrast-enhanced ultrasound; mNGS: metagenomic next-generation sequencing).

2.1. Classical Microbiological Methods

Beginning with the work of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch in the 1860s, microbiological culture has been the gold standard for diagnosing musculoskeletal infections []. While culture techniques have been integral to microbiology for over a century, their application in musculoskeletal infections faces several limitations. Many fastidious or slow-growing organisms require specific conditions and prolonged incubation periods. In the early 2000s, detection rates from synovial fluid or periprosthetic tissue cultures were highly variable, with reported sensitivity estimates ranging from 60% to 80%. Prior antibiotic exposure and suboptimal sampling techniques contributed to false-negative results [].

The introduction of enriched blood culture bottles (e.g., BACTEC™ and BacT/ALERT™) around the mid-2000s marked a milestone. These systems enable direct inoculation of aspirated synovial fluid, thereby enhancing the yield, particularly for slow-growing organisms such as Cutibacterium acnes. Furthermore, Schäfer et al. emphasized the need for obtaining multiple intraoperative tissue samples—ideally five or more—to increase diagnostic accuracy and account for potential contaminants []. Hackl et al. have consistently argued for the importance of long-term culturing, showing that this method more than doubles the pathogen detection rate in apparently aseptic tibial shaft nonunions, from 19.3% to 42.0% []. The clinical significance of identifying these late-appearing pathogens was confirmed in a follow-up study on femoral and tibial nonunions. It found that negative long-term outcomes were just as prevalent in patients with late-detected pathogens as in those with positive short-term cultures, affirming that a delayed diagnosis does not imply a less severe prognosis [].

Meanwhile, sonication of explanted prostheses, proposed since the early 2000s, has substantially enhanced the detection of biofilm-associated sessile bacteria. This technology releases adherent organisms into the surrounding fluid, which can then be cultured with higher sensitivity, particularly in patients who have received pre-operative antibiotics []. In 2020, the sonication method was expanded from joint arthroplasties to fracture fixation hardware, such as plates, screws, and nails, and newer methods of sonication, such as membrane-filtrated sonication, were introduced. Trenkwalder et al. showed a considerably higher polymicrobial detection rate with membrane filtration of the sonication fluid compared to tissue and sonication fluid broth culture [,]. However, in the context of chronic fracture-related infections, such as septic nonunion, it remains essential to establish a precise cut-off value to differentiate between bacterial contamination and infection. In a multicentric study, Trenkwalder et al. defined a cut-off value for differentiating between septic and aseptic nonunion as ≥ 13.6 CFU/10 mL sonication fluid [].

2.2. Biomarker-Based Diagnostics

Inflammatory biomarkers in peripheral blood and synovial fluid play a key role in infection workup. They may assist in the selective harvesting of tissue samples and in interpreting inconclusive culture results. Conventional tests, such as C-reactive protein (CRP)—introduced in daily clinical practice around 1980—and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), remain diagnostic workhorses due to their widespread availability and cost-effectiveness. Unfortunately, these assays have only modest diagnostic accuracy, particularly in chronic or low-grade infections [,]. For instance, in patients with presumed aseptic nonunion of long bones and normal CRP levels, the risk of missing low-grade infections may reach 26% []. In 2014, the introduction of point-of-care (POC) analysis for alpha-defensin, an antimicrobial peptide released by neutrophils, marked a milestone in the laboratory verification of periprosthetic joint infections. Results are available within ten minutes, show excellent sensitivity and specificity, and maintain performance even in patients receiving antibiotics []. In 2020, calprotectin, another neutrophil-derived protein, gained attention as an accurate biomarker in synovial fluid, thereby enhancing diagnostic precision when combined with synovial CRP []. Other promising candidates include interleukin-6 (IL-6), presepsin, and lipocalin-2. All these markers reflect systemic and localized immune responses, providing complementary data to identify infections.

Still, no single blood-based biomarker, or even a set of markers, can confirm or exclude infection of an arthroplasty or fracture fixation device (Table 1). Novel laboratory tests, ideally POC tests, are urgently required to rule infections in or out [].

Table 1.

Overview of biomarkers in the diagnosis of nonunions and fracture-related infections.

2.3. Molecular Diagnostics

Molecular techniques have revolutionized infection diagnostics by allowing for the rapid and precise identification of pathogens, even when conventional cultures fail. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), initially employed for single or multiplex pathogen detection, was expanded to include broad-range 16S rRNA amplification. This approach facilitates the detection of virtually all bacterial species. Nevertheless, vigilance is required to distinguish contaminants from true pathogens [].

The 2010s witnessed the emergence of real-time PCR (qPCR) and multiplex panels, which successfully detected pathogens in periprosthetic joint infection and spinal osteomyelitis. However, these assays are constrained by their reliance on pre-defined targets, which limits their utility when rare or unexpected pathogens are involved [].

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) addressed this gap. In contrast to PCR, mNGS can directly identify bacteria, viruses, fungi, and even antimicrobial resistance genes in clinical specimens, thereby offering a hypothesis-free diagnostic approach []. Numerous studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of mNGS. For instance, Zhao et al. observed higher sensitivity with mNGS than culture in diagnosing osteoarticular infections, particularly among patients with prior antimicrobial exposure []. Ivy et al. reported mixed infections and rare anaerobes in culture-negative periprosthetic joint infection cases using mNGS [].

Challenges associated with this technology include high costs, the need for rigorous contamination control, and the difficulty of interpreting polymicrobial results. Despite these challenges, mNGS is gaining interest and importance, particularly in cases that are complex or refractory. Yet, more and larger studies are needed to better define the diagnostic value of molecular techniques, especially in fracture-related infection [,].

2.4. Imaging Modalities

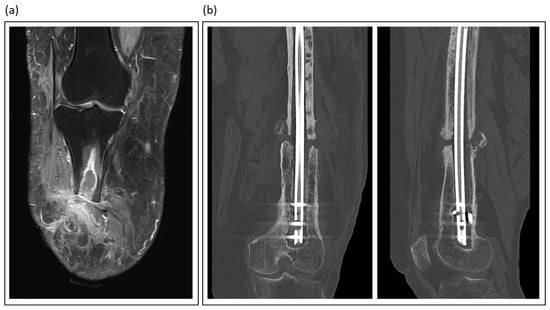

Imaging is key in diagnosing nonunions and fracture-related infections (Table 2). It confirms the presence and extent of disease, guides surgical planning, and monitors treatment response. Despite their wide availability, plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) are of limited accuracy and value in this scenario, particularly in early stages of chronic infection []. However, CT is invaluable in the diagnostic process and therapeutic planning of nonunion management (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of imaging modalities for nonunions and fracture-related infections.

Figure 2.

Illustrative imaging of nonunions and fracture-related infections: (a) T2-weighted MRI of a patient with traumatic lower leg amputation, showing an intraosseous abscess and soft tissue changes indicative of chronic infection; (b) Coronal and sagittal CT views of an atrophic femoral nonunion, a condition often linked to low-grade infection.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) emerged as the gold standard for evaluating osteomyelitis and intraousseus abscess formations (Figure 2). Its excellent soft tissue contrast allows for the visualization of marrow edema, abscess formation, and sinus tracts. Advanced sequences, such as contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted imaging, further enhance MRI sensitivity []. Love et al. emphasized the unparalleled value of MRI for the early detection of septic bone lesions, particularly in challenging situations such as diabetic foot infections []. However, metal artifacts make it difficult to diagnose infections associated with fracture fixation devices (plates, screws, and nails).

While many nuclear medicine methods for various diseases have lost their relevance in clinical practice, there are still niche indications in which alternative methods cannot replace them. 18FDG-PET/CT combines metabolic and anatomical imaging and has proved sensitive in diagnosing chronic osteomyelitis and distinguishing septic from aseptic prosthetic loosening [,].

Until recently, ultrasonography was mainly used to guide joint aspiration and detect periarticular fluid collections and abscess formations. However, between 2005 and 2010, the use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) emerged as a valuable diagnostic modality in the evaluation of FRI. Intravenous administration of gas-filled microbubbles enables high-resolution, real-time tissue perfusion and vascularization assessment without exposure to ionizing radiation or nephrotoxic agents. The efficacy of CEUS has been demonstrated by significant perfusion disparities between aseptic and septic nonunions [].

2.5. Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

Modern healthcare is typically characterized by step innovations rather than by leap or disruptive technologies. It is more likely that an informed and targeted combination of molecular, immunological, and computational methods will change our understanding of nonunions and FRI and improve care and outcomes.

In relation to the emerging field of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning models are trained on extensive datasets, including imaging, laboratory, and clinical parameters. This training aims to predict infection risk, optimize diagnosis, and suggest diagnostic and therapeutic pathways []. Consalvo et al. developed an AI algorithm to identify imaging features in standard radiographs, distinguishing between osteomyelitis and Ewing sarcoma []. In addition, it is essential to recognize that artificial intelligence will also have a substantial impact on therapy optimization. Specifically, AI-powered decision support systems can optimize antibiotic use by recommending the most effective treatments based on patient data and local patterns of antibiotic resistance [].

Alongside the development of artificial intelligence, the next generation of diagnostic tools is emerging. As mentioned above, a challenging diagnosis can be a low-grade infection that shows no clinical or radiological signs of infection. Therefore, the availability of a preoperative blood test to differentiate between aseptic conditions and low-grade infections would be of significant value. However, it is essential to remember that standard blood markers, such as white blood cell count or C-reactive protein, do not provide a definitive diagnosis. However, proteomics has the potential to provide valuable diagnostic biomarkers for differentiating septic from aseptic nonunion. In a preliminary analysis of plasma samples, Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) were found to be significantly higher in infected patients than in patients with healed and aseptic nonunion [].

It is crucial to recognize that similar challenges in diagnosing nonunions and FRI are likely to persist for the next quarter century, even with the introduction of new technologies and methods, including standardization, regulatory approval, cost-effectiveness, and integration into clinical workflows.

3. Orthoplastic Management of Open Fractures and Fracture-Related Infections

The orthoplastic approach to open fractures and fracture-related infections combines principles from orthopedic and trauma as well as plastic and reconstructive surgery to control infection and achieve both skeletal stabilization and cutaneous reconstruction. This section summarizes current strategies, emphasizing that early, vascularized soft tissue coverage plays a pivotal role in facilitating healing and preventing persistent deep infection.

3.1. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

The annual incidence of open fractures in industrialized countries is estimated at 11.5 per 100,000 people, with higher rates observed in cases of high-energy trauma []. The risk of infection depends on the severity of the soft tissue injury, neurovascular involvement, and both the timing and the adequacy of debridement. Consequently, reported infection rates range from 5% to over 30% for severe Gustilo-Anderson type IIIB and IIIC injuries [,].

The underlying pathophysiology involves direct bacterial contamination of the wound at the time of injury. This is aggravated by tissue ischemia, devitalization, periosteal stripping, and the presence of foreign material, which serves as a nidus for bacterial colonization. Therefore, managing these complex injuries requires meticulous debridement, stable bone fixation, reconstruction of neurovascular structures, and vascularized soft tissue coverage to establish a biological environment conducive to healing and less susceptible to (persistent) infection.

3.2. Principles of Orthoplastic Management

The core principles of orthoplastic management are adequate and repeated surgical debridement, stable skeletal fixation, early repair of neurovascular structures, and timely coverage with vascularized soft tissue, conjointly delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

In the context of orthoplastic reconstruction, meticulous surgical debridement is paramount and requires the excision of all non-viable tissue until resection margins of healthy, bleeding bone, muscle, and soft tissues are achieved. Techniques such as fluorescence-guided imaging and pulsatile lavage can aid in this process [,]. However, the role of high-pressure irrigation was questioned by the FLOW investigators, who favored low-pressure lavage []. Additionally, Hyperbaric oxygen therapy also seems to have a beneficial effect on wound healing in severe lower limb soft tissue injuries when implemented as an addition to standard trauma care []. A planned second-look operation is often mandatory to ensure the complete removal of any residual fibrin, contamination, or necrotic tissue. Once the wound is deemed macroscopically clean, the surgeon must select the optimal method for long-term mechanical stabilization, adapting the fixation strategy to the defect size and the condition of the soft-tissue envelope. External fixators provide versatile alignment with minimal additional trauma, whereas locked plates or intramedullary nails may be inserted immediately if adequate soft tissue coverage is achieved during the same operation. Robust evidence indicates that when performed after thorough debridement and under antibiotic coverage, immediate internal fixation (within 24–48 h) does not increase the risk of infection [].

This approach has been termed the “fix and flap” concept, coined by Godina, which underscores the importance of early flap coverage, ideally within 72 h []. This principle is supported by data from various nationwide registries [,,,]. For proximal tibial defects, local muscle flaps like the gastrocnemius can be alternative solutions in low energy trauma scenarios. However, a significant proportion of open fractures result from higher-energy traumas and are accompanied by extensive soft-tissue injury [,]. In this so-called “zone of injury”, disruption of the subdermal plexus, impairment of angiosome-crossing connective vessels, and compromise of muscular microvasculature can render both local skin as well as muscle flaps considerably less reliable [,]. Therefore, free tissue transfer should be regarded as the preferred treatment choice in cases of complex extremity trauma in specialized centers with appropriate expertise and strong interdisciplinary collaboration []. As an alternative, synthetic dermal substitutes are an emerging trend for temporizing coverage before definitive reconstruction. However, recent studies have shown high failure rates in the presence of pre-existing infection, limiting their use to a reserve option when vascularized flaps are not feasible []. Therefore, in cases of established infections, a nuanced approach that carefully balances infection control with the timing of reconstruction is warranted.

3.3. Orthoplastic Surgical Strategies

Although it is beyond question that timely definitive reconstruction is associated with better outcomes, the optimal time window until definitive orthoplastic reconstruction in open extremity fractures cannot be precisely quantified at present due to insufficient data []. Likewise, evidence suggests that both the intervals from the initial injury and from the onset of infection are of limited relevance in the treatment of fracture-related infections [,]. Rather, a well-executed debridement should be of utmost priority in both scenarios.

Following adequate debridement, single-stage reconstruction combines definitive skeletal fixation and soft-tissue coverage within a single surgical session. The rationale for this approach is to minimize bacterial colonization by immediately covering exposed bone and hardware and thus to reduce the risk of infection. In addition, this approach can help reduce the need for repeated anesthesia, shorten hospital stay, and accelerate rehabilitation. Several studies have reported promising results, particularly lower deep infection rates, for single-stage reconstructions in carefully selected patients with open fractures, particularly those with a well-demarcated infection, good physiological reserve, and a suitable soft-tissue donor site [,,]. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that rather than striving for the earliest possible definitive reconstruction, promptly achieving an adequate initial debridement is the most important predictor of success in the treatment of open fractures []. Particularly considering the advent of negative-pressure-wound-therapy, the ideal window until definitive reconstruction in open fractures may be extended up until about a week [,,]. Rather, the necessity of multiple serial radical debridements until vital bone and soft tissue are achieved should determine the time interval until definitive reconstruction [,]. The same rule holds true for fracture-related infections, where the same rationale in favor of timely soft tissue coverage after debridement applies as a matter of principle [,]. Yet, just as the quality of initial debridement is crucial for open fractures, infection control is of paramount importance when reconstructing chronic osteomyelitis, and should thus dictate both the timing and staging of the respective treatment protocol.

In line with this, staged reconstruction divides the treatment process into distinct phases, according to the underlying therapeutic goals. Following radical debridement, it involves temporary skeletal stabilization and dead-space management, often using local antibiotic carriers (e.g., beads or spacers) to clear infection. Once the infection is controlled, definitive reconstruction is achieved, including final skeletal fixation combined with or without bone defect reconstruction. This approach allows for serial debridements and close monitoring to confirm infection clearance before committing to definitive skeletal reconstruction [,]. In this context, soft-tissue reconstruction with microsurgical free flaps is usually performed within the first phase, given the importance of well-vascularized tissue coverage for infection control, usually in the form of short interval staged approaches [].

3.4. Types of Soft-Tissue Flaps for Coverage in Open Fractures and Fracture-Related Infections:

Despite their historical importance, local flaps now play a subordinate role, with exceptions for pedicled hand and finger flaps, and, in select cases of lower-energy injuries, robustly vascularized lower extremity muscle flaps like the gastrocnemius for the proximal and the soleus for the middle lower leg as well as the peroneus brevis for the lateral malleolus []. In cases of higher-energy trauma or chronic loco-regional infection, however, extensive inflammation and chronic ischemia in combination with advanced scarring and fibrosis, render local options less reliable [,]. Therefore, free flaps are the standard choice for soft tissue reconstruction in open fractures, particularly after high-energy trauma, and chronic osteomyelitis, as they tend to be safe and more reliable than local procedures in experienced hands.

When choosing a type of free flap, a distinction must be made between muscle or myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous or adipocutaneous flaps. While some studies showed higher partial necrosis rates for muscle free flaps in trauma-related reconstructions, presumably due to significantly larger flap sizes and higher metabolic demand, this does not seem to impact long-term outcomes, particularly regarding infection control in osteomyelitis cases [,]. However, cutaneous flaps offer other advantages, which is why they are increasingly used today. For one, they can achieve valuable protective sensibility as neurotized flaps through direct sensory coaptation, which is particularly advantageous for weight-bearing plantar defects. Furthermore, muscle flaps tend to form adhesions, whereas cutaneous flaps remain more pliable and are easier to elevate again for secondary osteosynthesis, which is of particular importance in staged reconstructions [].

In summary, the selection of the appropriate flap for traumatic or infectious defects represents a multifactorial decision that must account for defect size and location, infection burden, patient comorbidities, quality of local tissues and the associated donor-site morbidity. While successful free-tissue transfer is dependent on significant microsurgical expertise, it should be regarded as the preferred standard of care interdisciplinary orthoplastic management of open fractures and fracture-related infections.

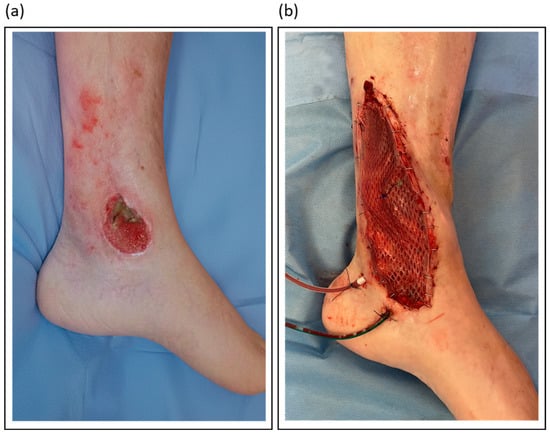

Table 3 outlines the author’s preferred flap types for various lower limb defect locations. Figure 3 illustrates a case of soft tissue reconstruction with a free flap.

Table 3.

Flap types for various lower limb defect locations.

Figure 3.

Illustrative orthoplastic management of a soft tissue defect following a distal lower leg fracture: (a) Clinical appearance of the chronic defect after initial debridement; (b) Intraoperative view of the same site after reconstruction with a gracilis free flap.

3.5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the orthoplastic management of open fractures and fracture-related infections requires a dedicated multidisciplinary effort, considerable expertise, and ample resources. It is based upon the core principles of radical debridement and infection control, stable skeletal fixation, and robust coverage with well-vascularized soft tissue. While single-stage reconstruction can offer benefits in select cases, the staged approach remains the mainstay for complex infections, guaranteeing the inherent flexibility needed for effective surgical infection control.

Tailoring the surgical strategy to the individual patient, the specific wound environment, and the available institutional resources is critical to achieve the best possible outcome. Current evidence suggests that a dedicated, interdisciplinary orthoplastic approach can halve the rate of infectious nonunion and osteomyelitis in open fractures and double the rate of long-term infection control and limb salvage in fracture-related infections [,,].

4. Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Substitutes in FRI and Nonunions

Radical debridement, essential for infection control and removal of necrotic tissue, frequently results in bone defects that require subsequent reconstruction to achieve successful healing []. Traditional treatment methods, such as autologous bone grafting combined with systemic antibiotics, remain the pillars of care. However, donor-site morbidity and limited graft availability have led to the development of various allogeneic and synthetic (alloplastic) bone graft alternatives over recent decades [,]. These “alloplasts” combine void filling with local antimicrobial efficacy [], providing promising solutions to the persistent challenges posed by infected nonunions and FRI. An ideal bone graft should exhibit osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and antiinfective properties. Osteoinduction refers to the capacity to stimulate bone formation, whereas osteoconductivity enables bone ingrowth into the graft.

Synthetic bone graft substitutes, comprising ceramics, polymers, or composites, are engineered to mimic the structural and chemical properties of native bone. They offer advantages such as unlimited availability and reduced risk of disease transmission. Certain synthetic graft materials can be directly impregnated with antibiotics, delivering therapeutic benefits over traditional systemic antibiotic therapy or non-antibiotic-loaded bone grafts by providing higher local antibiotic concentrations and minimal systemic side effects []. Table 4 summarizes commercially available bone graft substitutes capable of antibiotic loading.

Table 4.

Commercially available antibiotic-loaded bone graft substitutes. Herafil G (Heraeus) was excluded due to its discontinuation in recent years. Biopex®-R (HOYA) was excluded due to the absence of significant studies, aside from small case reports at the time of publication.

High local antibiotic concentrations established through antibiotic-loaded bone grafts can directly target pathogens in devitalized bone and biofilms, areas often unreachable by systemic antibiotics [,,,]. Local concentrations up to 100 times higher than systemic levels have been reported, which may explain their antimicrobial activity despite in vitro resistance findings, a crucial advantage when confronting the growing threat posed by multi-drug resistant pathogens []. Therefore, a synergistic strategy is employed where systemic antibiotics control widespread infection while local delivery eradicates pathogens in the poorly vascularized surgical site. While the duration of systemic therapy typically ranges from 6 to 12 weeks, the optimal length remains a subject of ongoing debate [,]. Furthermore, unlike polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) beads, which require a second removal procedure [], modern calcium sulphate-based or composite bone grafts are fully resorbable. This feature eliminates the need for additional surgery [,,]. Regarding antibiotic release kinetics, PMMA is also suboptimal, typically releasing <10% of the loaded antibiotic [,]. In contrast, calcium sulphate-based substitutes release virtually all of the loaded antibiotic during dissolution [].

4.1. Ceramic Bone Grafts

Among synthetic grafts, ceramic-based materials, particularly those combining calcium sulphate with hydroxyapatite, such as PerOssal® or Cerament®, have demonstrated promising outcomes. The inclusion of hydroxyapatite mitigates the early resorption of calcium sulfate, enhances biocompatibility, and reduces inflammatory responses, all while serving as a durable scaffold for bone regeneration [,]. Figure 4 presents an example of the use of absorbable PerOssal® beads.

Figure 4.

PerOssal® as part of the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis in a distal femur: (a) Postoperative X-Ray image; (b) Follow-up X-Ray 2 years later. The PerOssal®-Beads are largely resorbed. No recurrence of infection was detected clinically.

Comparisons among the various bone grafts are restricted by variations in study populations, defect sizes, and follow-up durations in the published literature. Few studies have evaluated multiple bone grafts within the same trial [,,,,], and only a subset directly compares reinfection and revision rates of the respective bone grafts. To date, no randomized controlled trials exist, leaving surgeons reliant on cohort studies, some of which are conducted in close collaboration with manufacturers, raising concerns about potential conflicts of interest.

Cerament® has one of the strongest evidence bases in the literature. It has demonstrated superb infection control and low complication rates in long bone nonunions and osteomyelitis [,,,] and has been extensively investigated in the context of diabetic foot infections [,,,,,,,,,,,]. Other bone grafts, like PerOssal® [,,] and Osteoset T® [,,,] have also shown favorable reinfection rates and in some cases offer a broader antibiotic-loading capacity. Multiple systematic reviews have attempted to compare the divergent published cohort studies; however, each is constrained by the heterogeneity and limitations of the available data [,,,,,,,].

4.2. Potential Side Effects

Calcium sulfate-based beads offer effective antibiotic delivery but may resorb too quickly, sometimes leading to increased wound drainage and void-related complications. In contrast, composite grafts maintain structural support for a longer duration, thereby enhancing bone healing and reducing recurrence, as evidenced by lower infection and complication rates in comparative studies [,]. Their biphasic nature enables both short- and long-term resorption, promoting bone ingrowth while serving as a local antibiotic carrier.

One frequently reported complication is increased postoperative wound drainage (ranging from 5% to over 30% in tibial cases), though it is thought to be related to the hygroscopic nature of calcium sulfate. Notably, composite materials are associated with fewer drainage complications compared to pure calcium sulfate grafts [,,]. However, most wound drainage episodes are described to be sterile and self-limiting, and rarely require surgical intervention []. Cerament®, an intraoperatively prepared antibiotic-loaded bone graft, is known to increase postoperative wound drainage []. Pre-hardened grafts like PerOssal® may reduce such issues but no direct comparison of two composite materials in larger cohort studies is yet available.

Although only low systemic concentrations of antibiotics are generally observed when using antibiotic-loaded grafts, clinicians should still monitor and account for renal function. Both vancomycin and tobramycin are nephrotoxic agents primarily eliminated by the kidneys. In patients with pre-existing renal impairment, reduced clearance can lead to systemic accumulation and toxic trough levels, even when the antibiotics are delivered from local carriers. Therefore, a patient’s renal function should be carefully considered to avoid systemic toxicity when using these therapies [,,].

4.3. Existing Gaps and Research Directions

Current concepts of alloplastic bone grafting have reached their limits in larger bone defects. The biological capacity appears constrained to minor bone defects of roughly 1–3 cm []. To overcome this challenge, current research focuses on incorporating osteoinductive proteins (e.g., bone morphogenetic protein 2 and parathyroid hormone) or bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid) into existing ceramic grafts [,]. While these adjuncts have shown promising effects in animal bone defect models, their efficacy in nonunion models [] and in human patients remains to be determined.

Furthermore, research directions aim to manage complex orthopedic infections through multi-drug-loaded 3D-printed scaffolds that can be enhanced with 4D “shape-memory” properties for a superior anatomical fit []. In parallel, new long-acting antibiotics like oritavancin show significant promise for treating infections caused by challenging, multi-drug resistant pathogens [].

4.4. Outlook

Over the last quarter century, antibiotic-loaded bone graft substitutes have revolutionized the management of FRI and nonunions. Their capacity to deliver high local antibiotic concentrations, potentially eliminate second-look surgeries, and confer osteoconductivity has made them invaluable in complex infection scenarios. Yet, clinical care and research stand at a pivotal juncture. Rigorous, large-scale head-to-head comparisons of the available grafts on the market are urgently needed to guide clinical decision-making and ensure patient safety.

Over the next 25 years, bone grafts will likely be integrated with biologically active adjuvants. Basic research will be crucial in identifying optimal combinations, paving the way for improved patient outcomes in the future.

5. Conclusions and Future Implications

The past quarter-century has witnessed profound transformations in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of nonunions and FRI. Diagnostic capabilities evolved from the foundational reliance on traditional microbiological cultures to the cutting-edge promise of metagenomic next-generation sequencing and artificial intelligence. Concurrently, therapeutic strategies have undergone substantial refinement, encompassing advancements such as orthoplastic management of infected open fractures and the local delivery of antibiotics via antibiotic-loaded bone substitutes.

The integration of these advancements necessitates highly specialized centers, which play an indispensable role in the most challenging cases, significantly impacting patient outcomes. This central role is increasingly vital given the global demographic shift towards an older population, which brings a higher burden of chronic diseases, immunosuppression, and prosthetic implants.

In conclusion, while significant progress has been made over the past 25 years, the journey is far from complete. The ongoing challenges, intensified by demographic shifts and antimicrobial resistance, underscore the necessity of an intelligent integration of advanced diagnostics, refined surgical techniques, innovative biomaterials such as multi-drug-loaded scaffolds. The field remains dynamic, demanding ongoing research, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to evidence-based practice to further enhance patient outcomes and continue to transform the management of nonunions and FRI for the next quarter-century and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and D.S.; investigation, J.A., B.T., N.S. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A., B.T., N.S. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, J.A., B.T., D.S., N.S., P.A.G. and S.H.; visualization, J.A., B.T., N.S. and S.H.; supervision, D.S., P.A.G. and S.H.; project administration, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The use of LLMs, specifically Gemini 2.5 pro (Alphabet Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) in this study was limited to enhancing the readability and refining the language by improving the vocabulary and structure of pre-generated text by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Djulbegovic, B.; Guyatt, G.H. Progress in Evidence-Based Medicine: A Quarter Century on. Lancet 2017, 390, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, J.; Bussmann, F.; Freischmidt, H.; Reiter, G.; Gruetzner, P.A.; El Barbari, J.S. Treatment of High-Grade Chronic Osteomyelitis and Nonunions with PerOssal®: A Retrospective Analysis of Clinical Efficacy and Patient Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejowski, P.; Giannoudis, P.V. The ‘Diamond Concept’ for Long Bone Non-Union Management. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2019, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Zheng, F.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, L. Prevalence and Influencing Factors of Nonunion in Patients with Tibial Fracture: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, J.; Steinhausen, E.; Hackl, S.; Reumann, M.K.; Stengel, D.; Niemeyer, F.; Reiter, G.; Gruetzner, P.A.; Freischmidt, H. The Power of Heuristics in Predicting Fracture Nonunion. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Hierl, K.; Brochhausen, C.; Alt, V.; Rupp, M. The Epidemiology and Direct Healthcare Costs of Aseptic Nonunions in Germany—A Descriptive Report. Bone Jt. Res. 2022, 11, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, M.R.; Hanus, B.D.; Sen, M.; O’Connor, D.P. The Devastating Effects of Tibial Nonunion on Health-Related Quality of Life. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2013, 95, 2170–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsemakers, W.-J.; Moriarty, T.F.; Morgenstern, M.; Marais, L.; Onsea, J.; O’Toole, R.V.; Depypere, M.; Obremskey, W.T.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; McNally, M.; et al. The Global Burden of Fracture-Related Infection: Can We Do Better? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e386–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zura, R.; Watson, J.T.; Einhorn, T.; Mehta, S.; Rocca, G.J.D.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jones, J.; Steen, R.G. An Inception Cohort Analysis to Predict Nonunion in Tibia and 17 Other Fracture Locations. Injury 2017, 48, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zura, R.; Xiong, Z.; Einhorn, T.; Watson, J.T.; Ostrum, R.F.; Prayson, M.J.; Della Rocca, G.J.; Mehta, S.; McKinley, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Epidemiology of Fracture Nonunion in 18 Human Bones. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, e162775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, S.; Keppler, L.; von Rüden, C.; Friederichs, J.; Perl, M.; Hierholzer, C. The Role of Low-Grade Infection in the Pathogenesis of Apparently Aseptic Tibial Shaft Nonunion. Injury 2021, 52, 3498–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Colangeli, M.; Colangeli, S.; Di Bella, C.; Gozzi, E.; Donati, D. Adult Osteomyelitis: Debridement versus Debridement plus Osteoset T Pellets. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2007, 73, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McNally, M.A.; Ferguson, J.Y.; Lau, A.C.K.; Diefenbeck, M.; Scarborough, M.; Ramsden, A.J.; Atkins, B.L. Single-Stage Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis with a New Absorbable, Gentamicin-Loaded, Calcium Sulphate/Hydroxyapatite Biocomposite: A Prospective Series of 100 Cases. Bone Jt. J. 2016, 98-B, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, S.M.; Bronze, M.S. Robert Koch and the “golden Age” of Bacteriology. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e744–e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, T.N.; Spelman, T.; Dylla, B.L.; Husghes, J.G.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Cheng, A.C.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Patel, R. Optimal Periprosthetic Tissue Specimen Number for Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, P.; Fink, B.; Sandow, D.; Margull, A.; Berger, I.; Frommelt, L. Prolonged Bacterial Culture to Identify Late Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Promising Strategy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, S.; von Rüden, C.; Trenkwalder, K.; Keppler, L.; Hierholzer, C.; Perl, M. Long-Term Outcomes Following Single-Stage Reamed Intramedullary Exchange Nailing in Apparently Aseptic Femoral Shaft Nonunion with Unsuspected Proof of Bacteria. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampuz, A.; Piper, K.E.; Jacobson, M.J.; Hanssen, A.D.; Unni, K.K.; Osmon, D.R.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Cockerill, F.R.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Greenleaf, J.F.; et al. Sonication of Removed Hip and Knee Prostheses for Diagnosis of Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkwalder, K.; Erichsen, S.; Weisemann, F.; Augat, P.; Sand, R.G.; Hackl, S. Membrane Filtration of Sonication Fluid—A Promising Adjunctive Method for the Diagnosis of Low-Grade Infection in Presumed Aseptic Nonunion. J. Orthop. Res. 2025, 43, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkwalder, K.; Erichsen, S.; Weisemann, F.; Augat, P.; Militz, M.; von Rüden, C.; Hentschel, T.; Hackl, S. The Value of Sonication in the Differential Diagnosis of Septic and Aseptic Femoral and Tibial Shaft Nonunion in Comparison to Conventional Tissue Culture and Histopathology: A Prospective Multicenter Clinical Study. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2023, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkwalder, K.; Hackl, S.; Weisemann, F.; Augat, P. The Value of Current Diagnostic Techniques in the Diagnosis of Fracture-Related Infections: Serum Markers, Histology, and Cultures. Injury 2024, 55 (Suppl. S6), 111862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosounidis, T.H.; Holton, C.; Giannoudis, V.P.; Kanakaris, N.K.; West, R.M.; Giannoudis, P.V. Can CRP Levels Predict Infection in Presumptive Aseptic Long Bone Non-Unions? A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deirmengian, C.; Kardos, K.; Kilmartin, P.; Cameron, A.; Schiller, K.; Booth, R.E.; Parvizi, J. The Alpha-Defensin Test for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Outperforms the Leukocyte Esterase Test Strip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Ploegmakers, J.J.W.; Ottink, K.; Kampinga, G.A.; Wagenmakers-Huizenga, L.; Jutte, P.C.; Kobold, A.C.M. Synovial Calprotectin: An Inexpensive Biomarker to Exclude a Chronic Prosthetic Joint Infection. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natoli, R.M.; Malek, S. Fracture-Related Infection Blood-Based Biomarkers: Diagnostic Strategies. Injury 2024, 55 (Suppl. S6), 111823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Tan, T.L.; Goswami, K.; Higuera, C.; Della Valle, C.; Chen, A.F.; Shohat, N. The 2018 Definition of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infection: An Evidence-Based and Validated Criteria. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1309–1314.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, R.; Kutz, A.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Procalcitonin-Guided Diagnosis and Antibiotic Stewardship Revisited. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmund, I.K.; Puchner, S.E.; Windhager, R. Serum Inflammatory Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Fernández-Pittol, M.J.; Muñoz-Mahamud, E.; Morata, L.; Bosch, J.; Vila, J.; Soriano, A.; Casals-Pascual, C. Evaluation of Lipocalin-2 as a Biomarker of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, M.; Garcia-Lechuz, J.M.; Alonso, P.; Villanueva, M.; Alcalá, L.; Gimeno, M.; Cercenado, E.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Radice, C.; Bouza, E. Role of Universal 16S rRNA Gene PCR and Sequencing in Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auñón, Á.; Coifman, I.; Blanco, A.; García Cañete, J.; Parrón-Cambero, R.; Esteban, J. Usefulness of a Multiplex PCR Assay for the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infections in the Routine Setting. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Miller, S.; Chiu, C.Y. Clinical Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Detection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Tang, K.; Liu, F.; Zhou, W.; Fan, J.; Yan, G.; Qin, S.; Pang, Y. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Improves Diagnosis of Osteoarticular Infections From Abscess Specimens: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivy, M.I.; Thoendel, M.J.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Hanssen, A.D.; Abdel, M.P.; Chia, N.; Yao, J.Z.; Tande, A.J.; Mandrekar, J.N.; et al. Direct Detection and Identification of Prosthetic Joint Infection Pathogens in Synovial Fluid by Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00402-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaert, G.A.M.; Kuehl, R.; Atkins, B.L.; Trampuz, A.; Morgenstern, M.; Obremskey, W.T.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; McNally, M.A.; Metsemakers, W.-J. Fracture-Related Infection (FRI) Consensus Group Diagnosing Fracture-Related Infection: Current Concepts and Recommendations. J. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 34, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.-T.J.; Eyre, D.W.; Atkins, B.L.; Simpson, A.H.R.W. Should Modern Molecular Testing Be Routinely Available for the Diagnosis of Musculoskeletal Infection? Bone Jt. J. 2020, 102-B, 1274–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, D.P.; Waldvogel, F.A. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 2004, 364, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, C.; Palestro, C.J. Nuclear Medicine Imaging of Bone Infections. Clin. Radiol. 2016, 71, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenter, V.; Müller, J.-P.; Albert, N.L.; Lehner, S.; Fendler, W.P.; Bartenstein, P.; Cyran, C.C.; Friederichs, J.; Militz, M.; Hacker, M.; et al. The Diagnostic Value of [(18)F]FDG PET for the Detection of Chronic Osteomyelitis and Implant-Associated Infection. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, T.C.; Kwee, R.M.; Alavi, A. FDG-PET for Diagnosing Prosthetic Joint Infection: Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, J.; Streblow, J.; Weber, M.-A.; Schmidmaier, G.; Fischer, C. The AMANDUS Project PART II—Advanced Microperfusion Assessed Non-Union Diagnostics with Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): A Reliable Diagnostic Tool for the Management and Pre-Operative Detection of Infected Upper-Limb Non-Unions. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, M.A.; Abdelrahman, A.; Zumla, A.; Ahmed, R.; Satta, G.; Zumla, A. Intersection of Artificial Intelligence, Microbes, and Bone and Joint Infections: A New Frontier for Improving Management Outcomes. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consalvo, S.; Hinterwimmer, F.; Neumann, J.; Steinborn, M.; Salzmann, M.; Seidl, F.; Lenze, U.; Knebel, C.; Rueckert, D.; Burgkart, R.H.H. Two-Phase Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection and Differentiation of Ewing Sarcoma and Acute Osteomyelitis in Paediatric Radiographs. Anticancer. Res. 2022, 42, 4371–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branda, F.; Scarpa, F. Implications of Artificial Intelligence in Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance: Innovations, Global Challenges, and Healthcare’s Future. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisemann, F.; Siverino, C.; Trenkwalder, K.; Heider, A.; Moriarty, F.; Hackl, S. Towards Preoperative Diagnosis of Infected Nonunion of Femur or Tibia with Targeted Proteomics in Blood Plasma. Orthop. Proc. 2023, 105-B, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court-Brown, C.M.; Rimmer, S.; Prakash, U.; McQueen, M.M. The Epidemiology of Open Long Bone Fractures. Injury 1998, 29, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustilo, R.B.; Mendoza, R.M.; Williams, D.N. Problems in the Management of Type III (Severe) Open Fractures: A New Classification of Type III Open Fractures. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1984, 24, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzakis, M.J.; Wilkins, J. Factors Influencing Infection Rate in Open Fracture Wounds. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, 243, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.T.; Jiang, S.; Henderson, E.R.; Slobogean, G.P.; O’Hara, N.N.; Xu, C.; Xin, J.; Han, X.; Christian, M.L.; Gitajn, I.L. Intraoperative Assessment of Bone Viability through Improved Analysis and Visualization of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Fluorescence Imaging: Technique Report. OTA Int. Open Access J. Orthop. Trauma 2022, 5, e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbeck, M.; Haustedt, N.; Schmidt, H.G. Surgical Debridement to Optimise Wound Conditions and Healing. Int. Wound J. 2013, 10, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FLOW Investigators; Bhandari, M.; Jeray, K.J.; Petrisor, B.A.; Devereaux, P.J.; Heels-Ansdell, D.; Schemitsch, E.H.; Anglen, J.; Della Rocca, G.J.; Jones, C.; et al. A Trial of Wound Irrigation in the Initial Management of Open Fracture Wounds. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2629–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, E.; Borgdorff, M.; Schepers, T.; Halm, J.A.; Winters, H.A.H.; Weenink, R.P.; Ridderikhof, M.L.; Giannakópoulos, G.F. Adjunctive Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in the Management of Severe Lower Limb Soft Tissue Injuries: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2024, 50, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, S.; Majumder, S.; Batchelor, A.G.; Knight, S.L.; De Boer, P.; Smith, R.M. Fix and Flap: The Radical Orthopaedic and Plastic Treatment of Severe Open Fractures of the Tibia. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. 2000, 82, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godina, M. Early Microsurgical Reconstruction of Complex Trauma of the Extremities. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1986, 78, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.A.; Ward, J.; Chapman, T.W.; Khan, U.M.; Kelly, M.B. Single-Stage Orthoplastic Reconstruction of Gustilo-Anderson Grade III Open Tibial Fractures Greatly Reduces Infection Rates. Injury 2015, 46, 2263–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuripla, C.; Tornetta, P.; Foote, C.J.; Koh, J.; Sems, A.; Shamaa, T.; Vallier, H.; Sorg, D.; Mir, H.R.; Streufert, B.; et al. Timing of Flap Coverage with Respect to Definitive Fixation in Open Tibia Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 35, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court-Brown, C.M.; Bugler, K.E.; Clement, N.D.; Duckworth, A.D.; McQueen, M.M. The Epidemiology of Open Fractures in Adults. A 15-Year Review. Injury 2012, 43, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, B.W.; Wade, S.M.; Harrington, C.J.; Potter, B.K.; Tintle, S.M.; Souza, J.M. Institutional Experience and Orthoplastic Collaboration Associated with Improved Flap-Based Limb Salvage Outcomes. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021, 479, 2388–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, A.N.; McCarthy, M.L.; Burgess, A.R. Short-Term Wound Complications after Application of Flaps for Coverage of Traumatic Soft-Tissue Defects about the Tibia. The Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) Study Group. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2000, 82, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapking, C.; Thomas, B.F.; Hundeshagen, G.; Haug, V.F.M.; Gazyakan, E.; Bliesener, B.; Bigdeli, A.K.; Kneser, U.; Vollbach, F.H. NovoSorb® Biodegradable Temporising Matrix (BTM): What We Learned from the First 300 Consecutive Cases. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 92, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.-K.; Aquilina, A.L.; Lewis, S.R.; Rodrigues, J.N.; Griffin, X.L.; Nanchahal, J. Timing of Antibiotic Administration, Wound Debridement, and the Stages of Reconstructive Surgery for Open Long Bone Fractures of the Upper and Lower Limbs. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 4, CD013555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytaç, S.; Schnetzke, M.; Swartman, B.; Herrmann, P.; Woelfl, C.; Heppert, V.; Gruetzner, P.A.; Guehring, T. Posttraumatic and Postoperative Osteomyelitis: Surgical Revision Strategy with Persisting Fistula. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2014, 134, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, M.; Corrigan, R.; Sliepen, J.; Dudareva, M.; Rentenaar, R.; IJpma, F.; Atkins, B.L.; Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Govaert, G. What Factors Affect Outcome in the Treatment of Fracture-Related Infection? Antibiotics 2022, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, R.J.; Kiss, A.; Johnson, S.; Stephen, D.J.G.; Kreder, H.J. Delayed Wound Closure Increases Deep-Infection Rate Associated with Lower-Grade Open Fractures: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2014, 96, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.A.H.; Fenton, P.; Bose, D. Single Stage versus Two-Stage Orthoplastic Management of Bone Infection. Injury 2022, 53, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Bowns, M.F.; Keating, J.F. Timing of Debridement: When to Do It, and Who Should Perform It? Injury 2024, 55 (Suppl. S6), 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.-H.; Stranix, J.T.; Rifkin, W.J.; Daar, D.A.; Anzai, L.; Ceradini, D.J.; Thanik, V.; Saadeh, P.B.; Levine, J.P. Timing of Microsurgical Reconstruction in Lower Extremity Trauma: An Update of the Godina Paradigm. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, E.L.H.; McNamara, C.T.; Constantine, R.S.; Greyson, M.A.; Iorio, M.L. The Continued Impact of Godina’s Principles: Outcomes of Flap Coverage as a Function of Time After Definitive Fixation of Open Lower Extremity Fractures. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2024, 40, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarth-Morales, T.E.; Davis, H.D.; Rios-Diaz, A.J.; Broach, R.B.; Serletti, J.M.; Azoury, S.C.; Levin, L.S.; Kovach, S.J.; Rhemtulla, I.A. The Godina Principle in the 21st Century: Free Flap Timing after Isolated Lower Extremity Trauma in a Retrospective National Cohort. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2025, 41, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholok, D.; Saberski, E.; Lowenberg, D.W. Approach to Complex Lower Extremity Reconstruction. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2022, 36, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.-H.; Daar, D.A.; Yu, J.W.; Kaoutzanis, C.; Saadeh, P.B.; Thanik, V.; Levine, J.P. Updates in Traumatic Lower Extremity Free Flap Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 152, 913e–918e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marais, L.C.; Hungerer, S.; Eckardt, H.; Zalavras, C.; Obremskey, W.T.; Ramsden, A.; McNally, M.A.; Morgenstern, M.; Metsemakers, W.-J. FRI Consensus Group Key Aspects of Soft Tissue Management in Fracture-Related Infection: Recommendations from an International Expert Group. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 144, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lari, A.; Esmaeil, A.; Marples, M.; Watts, A.; Pincher, B.; Sharma, H. Single versus Two-Stage Management of Long-Bone Chronic Osteomyelitis in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, A.; Machhada, A.; Tilston, T.; Colavitti, G.; Katsanos, D.; Chapman, T.; Wright, T.; Khan, U. Free Tissue versus Local Tissue: A Comparison of Outcomes When Managing Open Tibial Diaphyseal Fractures. Injury 2021, 52, 1625–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windhofer, C.; Schwabegger, A.; Ninkovic, M. Comparative Evaluation in the Treatment of Chronic Post-Traumatic Osteomyelitis of the Lower Leg: Free Flaps Compared with Local Flaps. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2001, 24, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranix, J.T.; Lee, Z.-H.; Jacoby, A.; Anzai, L.; Mirrer, J.; Avraham, T.; Thanik, V.; Levine, J.P.; Saadeh, P.B. Forty Years of Lower Extremity Take-Backs: Flap Type Influences Salvage Outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 141, 1282–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovar, A.; Colakoglu, S.; Iorio, M.L. Choosing between Muscle and Fasciocutaneous Free Flap Reconstruction in the Treatment of Lower Extremity Osteomyelitis: Available Evidence for a Function-Specific Approach. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2020, 36, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Hackenberg, R.K.; Krasniqi, D.; Eisa, A.; Böcker, A.; Gazyakan, E.; Bigdeli, A.K.; Kneser, U.; Harhaus-Wähner, L. Moderne Konzepte der interdisziplinären Extremitätenrekonstruktion bei offenen Frakturen. Die Unfallchirurgie 2024, 127, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klifto, K.M.; Azoury, S.C.; Othman, S.; Klifto, C.S.; Levin, L.S.; Kovach, S.J. The Value of an Orthoplastic Approach to Management of Lower Extremity Trauma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylitalo, A.A.J.; Hurskainen, H.; Repo, J.P.; Kiiski, J.; Suomalainen, P.; Kaartinen, I. Implementing an Orthoplastic Treatment Protocol for Open Tibia Fractures Reduces Complication Rates in Tertiary Trauma Unit. Injury 2023, 54, 110890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Alexander, M.; Bruce, S.; O’Connell, M.; Beecroft, S.; McNally, M. A Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing Clinical Outcomes and Healthcare Resource Utilisation in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Osteomyelitis in England: A Case for Reorganising Orthopaedic Infection Services. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2021, 6, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczak, J.W.; Palusińska, M.; Matak, D.; Pietrzak, D.; Nakielski, P.; Lewicki, S.; Grodzik, M.; Szymański, Ł. The Future of Bone Repair: Emerging Technologies and Biomaterials in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, M.P. Bone Grafts in Dental Medicine: An Overview of Autografts, Allografts and Synthetic Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haubruck, P.; Ober, J.; Heller, R.; Miska, M.; Schmidmaier, G.; Tanner, M.C. Complications and Risk Management in the Use of the Reaming-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA) System: RIA Is a Safe and Reliable Method in Harvesting Autologous Bone Graft. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliepen, J.; Corrigan, R.A.; Dudareva, M.; Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Rentenaar, R.J.; Atkins, B.L.; Govaert, G.A.M.; McNally, M.A.; IJpma, F.F.A. Does the Use of Local Antibiotics Affect Clinical Outcome of Patients with Fracture-Related Infection? Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, F.; Bahrinie, K.; Placht, A.M.; Gelinsky, M. Beladung und kontrollierte Freisetzung von Antibiotika aus Biomaterialien für die Knochenregeneration. In Orthopädische und Unfallchirurgische Praxis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J.; Diefenbeck, M.; McNally, M. Ceramic Biocomposites as Biodegradable Antibiotic Carriers in the Treatment of Bone Infections. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2017, 2, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambri, A.; Cevolani, L.; Passarino, V.; Bortoli, M.; Parisi, S.C.; Fiore, M.; Campanacci, L.; Staals, E.; Donati, D.M.; De Paolis, M. Mid-Term Results of Single-Stage Surgery for Patients with Chronic Osteomyelitis Using Antibiotic-Loaded Resorbable PerOssal® Beads. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, M.; Taccari, F.; Giovannenze, F. Systemic Antibiotic Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis in Adults. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, M.; Kümin, M.; Vach, W.; Kaier, K.; Ferguson, J.; McNally, M.; Scarborough, M. Short or Long Antibiotic Regimes in Orthopaedics (SOLARIO): A Randomised Controlled Open-Label Non-Inferiority Trial of Duration of Systemic Antibiotics in Adults with Orthopaedic Infection Treated Operatively with Local Antibiotic Therapy. Trials 2019, 20, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, A.I.; Nicolaou, D.; Hake, M.; McBride-Gagyi, S. Masquelet’s Induced Membrane Technique: Review of Current Concepts and Future Directions. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, M.A.; Ferguson, J.Y.; Scarborough, M.; Ramsden, A.; Stubbs, D.A.; Atkins, B.L. Mid- to Long-Term Results of Single-Stage Surgery for Patients with Chronic Osteomyelitis Using a Bioabsorbable Gentamicin-Loaded Ceramic Carrier. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-B, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palo, N.; Ray, B.; Lakhanpal, M.; Jeyaraman, M.; Choudhary, G.N.; Singh, A. Role of STIMULAN in Chronic Osteomyelitis-A Randomised Blinded Study on 95 Patients Comparing 3 Antibiotic Compositions, Bead Quality, Forming & Absorption Time. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2024, 52, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stravinskas, M.; Horstmann, P.; Ferguson, J.; Hettwer, W.; Nilsson, M.; Tarasevicius, S.; Petersen, M.M.; McNally, M.A.; Lidgren, L. Pharmacokinetics of Gentamicin Eluted from a Regenerating Bone Graft Substitute: In Vitro and Clinical Release Studies. Bone Jt. Res. 2016, 5, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, P.; Guidi, M.; Benninger, E.; Rönn, K.; Gautier, E.; Buclin, T.; Magnin, J.-L.; Livio, F. The Levels of Vancomycin in the Blood and the Wound after the Local Treatment of Bone and Soft-Tissue Infection with Antibiotic-Loaded Calcium Sulphate as Carrier Material. Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99-B, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vugt, T.A.G.; Geurts, J.; Arts, J.J. Clinical Application of Antimicrobial Bone Graft Substitute in Osteomyelitis Treatment: A Systematic Review of Different Bone Graft Substitutes Available in Clinical Treatment of Osteomyelitis. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6984656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Bourget-Murray, J.; Stubbs, D.; McNally, M.; Hotchen, A.J. A Comparison of Clinical and Radiological Outcomes between Two Different Biodegradable Local Antibiotic Carriers Used in the Single-Stage Surgical Management of Long Bone Osteomyelitis. Bone Jt. Res. 2023, 12, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanò, C.L.; Logoluso, N.; Meani, E.; Romanò, D.; Vecchi, E.D.; Vassena, C.; Drago, L. A Comparative Study of the Use of Bioactive Glass S53P4 and Antibiotic-Loaded Calcium-Based Bone Substitutes in the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis: A Retrospective Comparative Study. Bone Jt. J. 2014, 96-B, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Effect of Calcium Sulfate/Calcium Phosphate Composite for the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis Compared with Calcium Sulfate. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 1821833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, Y.; Walter, G.; Klug, A.; Harbering, J.; Kemmerer, M.; Hoffmann, R. Procedure for Single-Stage Implant Retention for Chronic Periprosthetic Infection Using Topical Degradable Calcium-Based Antibiotics. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, Y.; Johnson, T.; Kemmerer, M.; Walter, G.; Hoffmann, R.; Klug, A. Salvage Procedure for Chronic Periprosthetic Knee Infection: The Application of DAIR Results in Better Remission Rates and Infection-Free Survivorship When Used with Topical Degradable Calcium-Based Antibiotics. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020, 28, 2823–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Athanasou, N.; Diefenbeck, M.; McNally, M. Radiographic and Histological Analysis of a Synthetic Bone Graft Substitute Eluting Gentamicin in the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2019, 4, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutting, K.H.; aan de Stegge, W.B.; van Netten, J.J.; ten Cate, W.A.; Smeets, L.; Welten, G.M.J.M.; Scharn, D.M.; de Vries, J.-P.P.M.; van Baal, J.G. Surgical Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers Complicated by Osteomyelitis with Gentamicin-Loaded Calcium Sulphate-Hydroxyapatite Biocomposite. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavarthapu, V.; Giddie, J.; Kommalapati, V.; Casey, J.; Bates, M.; Vas, P. Evaluation of Adjuvant Antibiotic Loaded Injectable Bio-Composite Material in Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis and Charcot Foot Reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, V.; Tiruveedhula, M.; Edwards, J.; Dindyal, S.; Mulcahy, M.; Thapar, A. Antibiotic Eluting Bone Void Filler Versus Systemic Antibiotics For Pedal Osteomyelitis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2025, 64, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, J.; Stephenson, J.; Yates, B.J.; Cichero, M. Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis Treated with Surgical Adjuvant Antibiotic Loaded Bio-Composite Materials—A Comparative Retrospective Cohort Study. Foot Ankle Surg. Tech. Rep. Cases 2025, 5, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.; Imani, S.; Kavisinghe, I.; Mittal, R.; Martin, B. Definitive Single-Stage Surgery for Treating Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis: A Protocolized Pathway Including Antibiotic Bone Graft Substitute Use. ANZ J. Surg. 2024, 94, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendal, A.; Loizou, C.; Down, B.; McNally, M. Long-Term Follow-up of Complex Calcaneal Osteomyelitis Treated with Modified Gaenslen Approach. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2022, 7, 24730114221133391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaoy, S.; Rusu, I.; Pillai, A. Adjuvant Local Antibiotic Therapy in the Management of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis. Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, N.S.; Drampalos, E.; Morrissey, N.; Jahangir, N.; Wee, A.; Pillai, A. Adjuvant Antibiotic Loaded Bio Composite in the Management of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis—A Multicentre Study. Foot 2019, 39, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whisstock, C.; Volpe, A.; Ninkovic, S.; Marin, M.; Meloni, M.; Bruseghin, M.; Boschetti, G.; Brocco, E. Multidisciplinary Approach for the Management and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections with a Resorbable, Gentamicin-Loaded Bone Graft Substitute. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, J.C. Lower-Extremity Osteomyelitis Treatment Using Calcium Sulfate/Hydroxyapatite Bone Void Filler with Antibiotics Seven-Year Retrospective Study. J. Am. Podiatr. Med Assoc. 2018, 108, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasukutty, N.L.; Mordecai, S.; Subramaniam, M.; Tarik, A.; Srinivasan, B. Antibiotic Loaded Calcium Sulphate/Hydroxy Apatite Bio Composite in Diabetic Foot Surgery. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2020, 5, 2473011420S00479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down, B.; Ferguson, J.; Loizou, C.; McNally, M.; Ramsden, A.; Stubbs, D.; Kendal, A. Single-Stage Orthoplastic Treatment of Complex Calcaneal Osteomyelitis with Large Soft-Tissue Defects: Long-Term Follow-Up. Bone Jt. J. 2024, 106-B, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visani, J.; Staals, E.L.; Donati, D. Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis with Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Void Filler Systems: An Experience with Hydroxyapatites Calcium-Sulfate Biomaterials. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2018, 84, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, J.; Yue, S.; Li, Y.; Lu, W. Short-Term and Long-Term Efficacy Evaluation of Drug-Loaded Osteoset Artificial Bone Grafting Fusion in the Treatment of Sacroiliac Joint Tuberculosis. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2024, 30, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, D.; Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Zhao, F. Treating Sacroiliac Joint Tuberculosis with Rifampicin-Loaded OsteoSet. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2015, 29, 406–411. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; He, J. Effect evaluation of medical calcium sulfate--OsteoSet in repairing jaw bone defect. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2012, 26, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rodham, P.; Giannoudis, P.V. Innovations in Orthopaedic Trauma: Top Advancements of the Past Two Decades and Predictions for the next Two. Injury 2022, 53, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thahir, A.; Lim, J.A.; West, C.; Krkovic, M. The Use of Calcium Sulphate Beads in the Management of Osteomyelitis of Femur and Tibia: A Systematic Review. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022, 10, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Z.; Lau, E.J.-S.; Aslam, A.; Thahir, A.; Krkovic, M. Management of Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Femur and Tibia: A Scoping Review. EFORT Open Rev. 2021, 14, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, Y.; Schnetz, M.; Hoffmann, R. Lokale Antibiotikatherapie in der Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie. Z. Orthopädie Unfallchirurgie 2023, 161, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, C.C.; Daw, J.H.; Santiago-Torres, J. The Efficacy of Antibiotic-Impregnated Calcium Sulfate (AICS) in the Treatment of Infected Non-Union and Fracture-Related Infection: A Systematic Review. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2023, 8, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humm, G.; Noor, S.; Bridgeman, P.; David, M.; Bose, D. Adjuvant Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Tibia Following Exogenous Trauma Using OSTEOSET®-T: A Review of 21 Patients in a Regional Trauma Centre. Strat. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2014, 9, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, P.; Livio, F.; Jacobi, M.; Gautier, E.; Buclin, T. Systemic Exposure to Tobramycin after Local Antibiotic Treatment with Calcium Sulphate as Carrier Material. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2011, 131, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livio, F.; Wahl, P.; Csajka, C.; Gautier, E.; Buclin, T. Tobramycin Exposure from Active Calcium Sulfate Bone Graft Substitute. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freischmidt, H.; Guehring, T.; Thomé, P.; Armbruster, J.; Reiter, G.; Grützner, P.A.; Nolte, P.-C. Treatment of Large Femoral and Tibial Bone Defects with Plate-Assisted Bone Segment Transport. J. Orthop. Trauma 2024, 38, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, D.B.; Matuszewski, L.-M.; Vater, C.; Bolte, J.; Isaksson, H.; Lidgren, L.; Tägil, M.; Zwingenberger, S. A Facile One-Stage Treatment of Critical Bone Defects Using a Calcium Sulfate/Hydroxyapatite Biomaterial Providing Spatiotemporal Delivery of Bone Morphogenic Protein-2 and Zoledronic Acid. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freischmidt, H.; Armbruster, J.; Bonner, E.; Guehring, T.; Nurjadi, D.; Bechberger, M.; Sonntag, R.; Schmidmaier, G.; Grützner, P.A.; Helbig, L. Systemic Administration of PTH Supports Vascularization in Segmental Bone Defects Filled with Ceramic-Based Bone Graft Substitute. Cells 2021, 10, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, L.; Guehring, T.; Titze, N.; Nurjadi, D.; Sonntag, R.; Armbruster, J.; Wildemann, B.; Schmidmaier, G.; Gruetzner, A.P.; Freischmidt, H. A New Sequential Animal Model for Infection-Related Non-Unions with Segmental Bone Defect. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Vahabi, H.; Kumaravel, V. Antimicrobial and Biodegradable 3D Printed Scaffolds for Orthopedic Infections. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4020–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastain, D.B.; Davis, A. Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis with Multidose Oritavancin: A Case Series and Literature Review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).