Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of studies investigating the impact of occupational exoskeletons on work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WMSD) risk factors. The primary objective is to examine the methodologies used to assess the effectiveness of these devices across various occupational tasks. A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines, covering studies published between 2014 and 2024. A total of 49 studies were included, identified through searches conducted in Scopus and Web of Science databases, with the search string launched in August 2024. The review identifies a growing body of research on passive and active exoskeletons, with a notable focus on laboratory-based evaluations. The results indicate that direct measurement and self-report methods are the preferred approaches in these domains. Ergonomic limitations and user discomfort remain concerns in some cases. The findings of this review may influence stakeholders by providing insights into the potential benefits of adopting exoskeletons and improving workplace ergonomics to reduce WMSD risks. Additionally, the identification of WMSD assessment methods will be valuable for validating the use of these technologies in the workplace. The review concludes with recommendations for future research, emphasizing the need for more real-world assessments and improved exoskeleton designs to enhance user comfort and efficacy.

1. Introduction

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) have long been recognized as a leading cause of occupational injuries [1], accounting for a significant proportion of absenteeism, reduced work productivity, and long-term disabilities worldwide [2]. The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) [3] reports that approximately 60% of workers across Europe are affected by musculoskeletal discomfort, underscoring the widespread impact of these conditions.

Scientific literature systematically indicates that WMSD prevalence is higher among specific working populations and occupational sectors compared to the general population [4]. This suggests a causal relationship between various occupational risk factors and the development of these conditions. Risk factors such as awkward body postures, repetitive movements, manual handling of heavy loads, mechanical vibrations, and work-related stress play a significant role in the development of WMSD [5]. Consequently, industries where these risk factors are prevalent, such as manufacturing, construction, and logistics, tend to report higher rates of WMSD [6]. These physical demands place substantial biomechanical stress on body areas such as the back, shoulders, and upper and lower limbs [7].

In recent years, the development and implementation of occupational exoskeletons have emerged as a potential solution to mitigate the risks associated with these physically demanding tasks [8]. The evidence supporting these claims is presented in this review’s Section 3, providing detailed insights into their effectiveness.

These exoskeletons are wearable devices designed to provide mechanical support to the body, helping to reduce the biomechanical strain on muscles and joints [9,10,11]. Specifically, exoskeletons are designed to limit muscle movement, reduce the effort required by the body to perform tasks, and/or help maintain non-neutral postures [12]. Typically made from materials like carbon fiber, aluminum, or plastic, these devices feature a lightweight frame or structure that can be worn on the torso, arms, or legs [13].

In addition to their general design, exoskeletons can be classified based on the body part they support [14]. Upper body exoskeletons assist the arms, shoulders, and torso, reducing fatigue and improving precision during tasks involving repetitive overhead motions or heavy lifting [15]. Lower body exoskeletons support the hips, legs, and knees, improving mobility and stability while reducing strain in activities involving standing or sitting postures [10]. Lower back exoskeletons are specifically designed to support the lumbar region, helping to prevent injuries and reduce strain during lifting, bending, or prolonged standing [16], making them particularly useful in industries where lower back pain is common. There are also exoskeletons developed to provide support to specific parts of the body. Their usefulness depends on the particular body part they are designed to support. For example, some exoskeletons are specifically designed to offer support to the elbow [17] or neck [18]. Furthermore, exoskeletons can also be classified based on their actuation as either active or passive [10]. Passive exoskeletons typically rely on spring-based mechanisms to redistribute the user’s body weight and reduce strain [19,20]. In contrast, active exoskeletons use motors or actuators to provide powered assistance [21], making tasks like lifting or overhead work easier by directly enhancing the user’s strength and endurance.

Studies have shown that exoskeletons can significantly reduce WMSD and perceived discomfort [22,23,24,25]. However, assessing their effectiveness in lowering WMSD risk is a complex and non-standardized process due to the wide range of ergonomic evaluation methods. These methods are typically divided into three categories: self-report and checklists, observational methods, and direct measurement techniques [26,27,28]. Self-reports and checklists are commonly used tools in occupational ergonomics [29], with validated questionnaires like the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) [30] used to gather workers’ perceptions and checklists such as the “OSHA checklist” from the Occupational and Health Administration (OSHA) [31] applied to identify risk factors. Observational methods, including tools like the Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) [32] and the Key Indicator Method for Manual Handling Operations (KIM-MHO) [33], rely on direct observation of work tasks, assessing factors like task frequency, duration, and load handling to evaluate the external physical workload [27]. Direct measurement methods involve the use of sensors to assess the effect of risk factors on physiological and biomechanical parameters [26], with examples including surface electromyography (EMG) [34,35] to measure muscular activity and motion capture devices [36] to record joint motion.

The methodologies used to assess WMSD risk factors in exoskeleton studies vary considerably. This diversity in approaches makes it challenging to compare findings across different studies.

The methodologies used to assess WMSD risk factors in exoskeleton studies vary considerably. This diversity in approaches makes it challenging to compare findings across different studies. Within this scope, other review studies have primarily focused on specific aspects of exoskeleton use or their general impact on occupational health and safety, but often leave methodological considerations underexplored. For instance, Kranenborg et al. (2023) [37] focused on the side effects and usability of shoulder and back-support exoskeletons, primarily in laboratory settings, noting the lack of long-term and real-world assessments. Similarly, Flor-Unda et al. (2023) [12] reviewed the role of exoskeletons in reducing physical strain across various industries but lacked a detailed analysis of the methodologies used to assess their effectiveness in specific tasks. Kermavnar et al. (2021) [38] reviewed industrial back-support exoskeletons and emphasized the need for more field studies, as most of the research was conducted in controlled environments with healthy young men. These limitations underscore the need for a review that bridges these gaps by providing an examination of the methodologies used in the evaluation of both active and passive exoskeletons. This review uniquely addresses these gaps by exploring trends in the ergonomic evaluation methods applied. The major contribution of this paper is, to sum up studies that have focused on the evaluation of occupational exoskeleton, providing detailed information on their methodological approach and highlighting the current state of the art in this research field.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was guided by the methodology of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [39]. Since its inception in 2009, the PRISMA methodology has provided a transformative framework for developing literature reviews, ensuring they are comprehensive, transparent, and unbiased [40]. The PRISMA-ScR checklist (Table A1 in Appendix A) was used in this review.

2.1. Information Source, Screening, and Eligibility Criteria

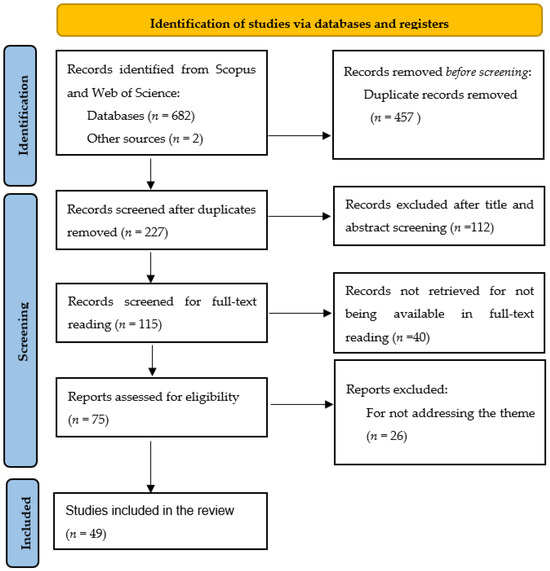

First, a detailed search was performed using the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The selection of these databases was justified by their prominence and relevance to publications in the engineering and manufacturing domains [41]. Additionally, the decision to limit our search to only two databases align with practices in other systematic reviews that have adopted the PRISMA methodology [37,38], particularly in fields where these databases provide comprehensive coverage of the relevant literature. The search strategy included the keywords “Exoskeleton” and “WMSD” and focused on articles published between 2014 and 2024. This timeframe was chosen to reflect recent developments in occupational exoskeleton research, which has gained significant attention in the last decade. The initial search retrieved 682 articles, and an additional two articles from a personal database were included, resulting in a total of 684 records. The steps undertaken to conduct the systematic review are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Steps of the PRISMA protocol for the literature review on WMSD risk assessment methods in assistive working (adapted from Moher et al. (2009) [39]).

The screening phase aimed to filter the articles based on predefined inclusion criteria. Only papers written in English, available as open-access publications, and provided as full-text journal articles or conference papers were considered. To manage the dataset, Microsoft Excel Version 16.03 was used to organize and sort the records by title, facilitating the removal of duplicates. This step reduced the dataset to 227 studies for further evaluation. Then, titles and abstracts were screened to identify the studies specifically related to occupational exoskeletons. To be included, articles had to meet several criteria. They needed to involve healthy adults within the working age range and focus on exoskeletons designed to reduce physical load. Studies were required to take place in a workplace environment or a laboratory setting explicitly described as simulating or imitating workplace conditions. Furthermore, the application of WMSD risk assessment methods was mandatory, and only studies with full-text availability were considered.

Studies included in the review either had a control group, including a control group without exoskeleton use, or compared different exoskeleton types. Articles were excluded if they did not assess WMSD risk using ergonomic assessment methods, focused on non-occupational exoskeleton applications such as rehabilitation or military purposes, or involved participants outside the working-age population. By narrowing the scope to only include occupational applications, we aim to ensure that the review provides a targeted and in-depth analysis of the methodologies and effectiveness of exoskeletons in the specific context of workplace use. No restrictions were applied regarding study design, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the existing literature.

Finally, full-text analysis was conducted on 115 eligible studies to ensure they aligned with the objectives of the review. Of these, 40 were not available for full-text reading, leaving 75 studies available for analysis. From these, 26 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in 49 articles included for review. This systematic approach provided a robust foundation for examining the impact of occupational exoskeletons on WMSD risk factors and their broader implications for workplace ergonomics.

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

After the selection and full-text reading of the articles to be included, a table was constructed in Microsoft Excel Version 16.03 to systematically extract and organize the relevant information from each study. The primary aim was to gather key details to better understand the methods employed and inform future research. The extracted information included the following: authorship details, publication year, number of participants, type of exoskeleton tested (passive or active), body part supported by the exoskeleton, study context (whether the study was conducted in a laboratory, simulated on-site, or on-site), types of tasks studied, WMSD risk assessment methods applied, and the main conclusions drawn from each study.

Subsequently, additional tables and graphs were created to more effectively visualize the extracted data, enabling a clearer interpretation and comparison of findings. This structured and graphical approach facilitated a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies and outcomes in the field of occupational exoskeletons and WMSD risk assessment.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the findings of the systematic review, organized into four key areas. First, an overview of the reviewed studies is provided, including the publication years, participant demographics, and study contexts (Section 3.1). Next, the focus shifts to the exoskeletons examined, detailing their design features, actuation types, and supported body parts (Section 3.2). The methodological approaches employed in the studies are then discussed, highlighting the diversity of WMSD risk assessment methods and their applications (Section 3.3). Finally, the main conclusions of the reviewed studies are summarized, offering insights into the effectiveness, challenges, and future potential of occupational exoskeletons (Section 3.4).

3.1. Overview of the Year, Participants, and Study Context

To provide a broader perspective on the included studies, an overview of the publication year, number of participants, and study context is first presented (Table 1). It should be noted that the number of participants is also segmented by gender, with the average age, height, and weight being presented, when available.

Related to the years of publication distribution, the studies on the evaluation of occupational exoskeletons show a clear upward trend over the years. Beginning with a minimal number of publications in 2018 [42] and 2019 [43], each with just one study, there is a gradual increase in research output. In 2020 [9,24,44], and 2021 [22,23,45,46] the number of studies rose to four, followed by a jump to seven published in 2022 [11,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

A substantial surge in research activity was observed in 2023 [16,17,18,21,25,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], with 20 studies being published, reflecting a peak in scholarly interest in the field. While there was a slight decline in 2024 [10,14,15,20,69,70,71,72,73,74,75], with 11 studies, the overall trend demonstrates a sustained and growing interest in the evaluation of occupational exoskeletons over this period. Notably, no study was found between the period of 2014 to 2017.

Table 1.

Articles distribution according to the number of participants and study context.

Table 1.

Articles distribution according to the number of participants and study context.

| Authors (Year) | Number of Participants | Study Context |

|---|---|---|

| Moyon et al. (2018) [42] | n = 9 (♂5; ♀4); Age: 20–40, Height N.A., Weight: N.A. | On-site |

| Schmalz et al. (2019) [43] | n = 12 (♂6; ♀6); Age: 24.0, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 73.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Perez Luque et al. (2020) [9] | n = 17 (♂11; ♀6); Age: 25, Height 174.0, Weight: N.A. | Simulated On-site |

| Alabdulkarim et al. (2020) [44] | n = 16 (♂16; ♀0); Age: 34.3 Height 164.4 cm, Weight: 70.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Cardoso et al. (2020) [76] | n = 5 (♂2; ♀3); Age: 29.0, Height 165.0 cm, Weight: 76.0 kg | On-site |

| Lazzaroni et al. (2020) [24] | n = 9 (♂9; ♀0); Age: 27.3, Height 182.0 cm, Weight: 73.8 kg | Laboratory |

| Kong et al. (2021) [23] | n = 20 (♂13 Age: 22.5, Height 176.4 cm, Weight: 72.0 kg; ♀7); Age: 20.7, Height 165.5 cm, Weight: 57.2 kg) | Laboratory |

| Schwartz et al. (2021) [45] | n = 29 (♂15 Age: 23.0, Height 179.0 cm, Weight: 77.0 Kg; ♀14 Age: 22.0, Height 167.0 cm, Weight: 58.0 kg) | Laboratory |

| Lazzaroni et al. (2021) [46] | n = 10 (♂10; ♀0); Age: 29.8, Height 177.8 cm, Weight: 74.4 kg | Laboratory |

| Yin et al. (2021) [22] | n = 10 (♂10; ♀0); Age: 24.7, Height 174.8 cm, Weight: 68.3 kg | Laboratory |

| Weston et al. (2022) [47] | n = 6 (♂10 Age: 21.2, Height 179.5 cm, Weight: 79.8 kg; ♀6 Age: 22.5, Height 165.5 cm, Weight: 57.6.4 kg) | Laboratory |

| vam der Have et al. (2022) [48] | n = 16 (♂8; ♀8); Age: 21.9, Height N.A., Weight: N.A. | Laboratory |

| Kong et al. (2022) [49] | n = 20 (♂20; ♀0); Age: 24.8, Height 176.4 cm, Weight: 78.8 kg | Laboratory |

| Iranzo et al. (2022) [50] | n = 8 (♂4; ♀4); Age: 35.0, Height 175.6 cm, Weight: 67.9 kg | Laboratory |

| Latella et al. (2022) [11] | n = 12 (♂12; ♀0); Age: 23.2, Height 179.3 cm, Weight: 72.7 kg | Laboratory |

| De Bock et al. (2022) [51] | n = 22 (♂22; ♀0); Age: 23.7, Height 181.6 cm, Weight: 75.9 kg | Laboratory |

| Goršič et al. (2022) [52] | n = 10 (♂5; ♀5); Age: 28.4, Height 170.0 cm, Weight: 71.2 kg | Laboratory |

| Sierotowicz et al. (2022) [53] | n = 12 (♂9; ♀3); Age: 27.6, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 71.9 kg | Laboratory |

| Mitterlehner et al. (2023) [54] | n = 30 (♂22; ♀8); Age: 29.0, Height 180.2 cm, Weight: 74.8 kg | Laboratory |

| R. M. Van Sluijs et al. (2023) [55] | n = 14 (♂5; ♀9); Age: 25.3, Height 170.0 cm, Weight: 70.7 kg | Laboratory |

| Garosi et al. (2023) [18] | n = 14 (♂14; ♀0); Age: 28, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 71.6 kg | Laboratory |

| Walter et al. (2023) [56] | n = 14 (♂11; ♀3); Age: 22.3, Height 177.7 cm, Weight: 71.9 kg | Laboratory |

| Kong et al. (2023) [57] | n = 20 (♂20; ♀0); Age: 24.4, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 78.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Shim et al. (2023) [58] | n = 20 (♂20; ♀0); Age: 24.4, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 78.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Brunner et al. (2023) [59] | n = 32 (♂17; ♀15); Age: 26.7, Height 174.0 cm, Weight: 72.1 kg | Laboratory |

| Öçal et al. (2023) [21] | n = 3 (♂2; ♀1); Age: 33.3, Height 179.0 cm, Weight: 71.6 kg | Laboratory |

| Schrøder Jakobsen et al. (2023) [61] | Control: n = 10 (♂N.A.; ♀N.A.); Age: 32.2, Height 180.3 cm, Weight: 82.4 kg; Intervention n = 10 (♂N.A.; ♀N.A.); Age: 33.3, Height 181.9 cm, Weight: 87.4 kg | On-site |

| Govaerts et al. (2023) [60] | n = 16 (♂10; ♀6); Age: 35.0, Height 173.9 cm, Weight: 72.4 kg | Laboratory |

| Verdel et al. (2023) [62] | n = 19 (♂12; ♀7); Age: 24.0, Height 173.0 cm, Weight: 66.7 kg | Laboratory |

| Reimeir et al. (2023) [63] | n = 12 (♂9; ♀3); Age: 27.2, Height 179.4 cm, Weight: 75.3 kg | Laboratory |

| R.M. van Sluijs et al. (2023) [16] | n = 30 (♂22; ♀8); Age: 27.0, Height 178.0 cm, Weight: 72.9 kg | Laboratory |

| Park et al. (2023) [17] | n = 5 (♂3; ♀2); Age: 28.8, Height 175.0 cm, Weight: 65.4 kg | Laboratory |

| Ding et al. (2023) [25] | n = 9 (♂9; ♀0); Age: 24.6, Height 176.3 cm, Weight: 72.2 kg | Laboratory |

| Cuttilan et al. (2023) [64] | n = 10 (♂N.A.; ♀N.A.); Age: N.A., Height 170.0 cm, Weight: N.A. | Laboratory |

| De Bock et al. (2023) [65] | n = 16 (♂16; ♀0); Age: 29.3, Height 181.0 cm, Weight: 81.4.5 kg | Laboratory |

| Bhardwaj et al. (2023) [66] | n = 10 (♂16; ♀0); Age: 21–28, Height 171.1 cm, Weight: 71.2 kg | Laboratory |

| Thang (2023) [67] | n = 10 (♂10; ♀0); Age: 18–22, Height 170.0 cm, Weight: 70 kg | Laboratory |

| Schwartz et al. (2023) [68] | n = 29 (♂15 Age: 25.0, Height 180.0 cm, Weight: 74.9.kg; ♀0); Age: 24.0, Height 166.0 cm, Weight: 63.6.5 kg | Laboratory |

| Musso et al. (2024) [14] | n = 18 (♂18; ♀0); Age: 27.11, Height 179.5 cm, Weight: 78.67 kg | Laboratory |

| Schrøder Jakobsen et al. (2024) [69] | Control: n = 10 (♂7; ♀3); Age: 30.3, Height 177.9 cm, Weight: 81.1 kg; Intervention n = 9 (♂7; ♀2); Age: 29.8, Height 181.0 cm, Weight: 81.8 kg | On-site |

| Rafique et al. (2024) [10] | n = 9 (♂7; ♀2); Age: 30.0, Height 160.0–185.0 cm, Weight: 160.0–180.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Davoudi Kakhki et al. (2024) [70] | n = 22 (♂10; ♀12); Age: 20.5, Height N.A., Weight: 66.3 kg | Laboratory |

| van Sluijs et al. (2024) [71] | n = 31 (♂16; ♀15); Age: 28.0, Height 176.3 cm, Weight: 76.4 kg | Laboratory |

| Favennec et al. (2024) [72] | n = 18 (♂18; ♀0); Age: 21.5, Height 178.3 cm, Weight: 69.6 kg | Laboratory |

| Lee et al. (2024) [73] | n = 5 (♂5; ♀0); Age: 27.0, Height 174.8 cm, Weight: 70.0 kg | Laboratory |

| Gräf et al. (2024) [15] | n = 10 (♂5; ♀5); Age: 25.3, Height 174.6 cm, Weight: N.A. | Laboratory |

| Govaerts et al. (2024) [74] | n = 18 (♂10; ♀8); Age: 33.0, Height 173.5 cm, Weight: 70.6 kg | Laboratory |

| Bär et al. (2024) [75] | n = 36 (♂36; ♀0); Age: 25.9, Height 178.7 cm, Weight: 73.5 kg | Laboratory |

| Cardoso et al. (2024) [20] | n = 2 (♂1; ♀1); Age: 25.5, Height 176.0 cm, Weight: 77.5 kg | Simulated On-site |

This progression suggests an expanding recognition of the importance and relevance of exoskeletons in occupational settings, as well as a corresponding increase in academic and practical investigation into their applications and impacts.

The distribution of the number of participants per study in the evaluation of occupational exoskeletons reveals a varied approach to sample sizes across the reviewed literature. The data indicates a preference for certain participant group sizes, with the most common being studies involving 10 participants [15,22,46,52,61,64,66,67,69], as reflected by the fact that nine studies employed this number. This is followed by studies with 9 [10,25,42,46], 12 [11,43,53,63], 16 [44,48,60,65], and 20 participants [23,49,57,58], each represented in four studies.

Smaller sample sizes, such as 5 participants, were utilized in three studies [17,73,76], while studies with more participants, namely 14 [16,18,56], and 18 [14,72,74] also appeared three times. Several other studies employed sample sizes ranging from 2 to 36 participants, but these were less common and typically involved only one or two studies per group size. Notably, the studies with the highest number of participants, 31 [71], 32 [59], and 36 [75], were each represented by a single study.

This distribution suggests that while there is no standardized sample size for evaluating occupational exoskeletons, there is a slight tendency towards moderate-sized groups, with 10 participants being particularly favored. The variance in participant numbers could reflect the diversity of research designs, objectives, and resource availability within the field.

The distribution of study contexts in the evaluation of occupational exoskeletons reveals a strong preference for laboratory-based research. According to the data, 43 studies were conducted in a laboratory setting [10,11,14,15,16,17,18,21,22,23,24,25,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75], indicating that controlled environments are the predominant choice for examining the efficacy and safety of exoskeletons.

In contrast, only a small number of studies—four in total—were carried out on-site [42,61,69,76], directly within the work environment. Even fewer studies—just two—employed a simulated on-site context [9,20], where real-world conditions were mimicked but not conducted at the actual worksite.

This distribution suggests that while laboratory settings offer the advantages of control and repeatability, there is a growing, albeit limited, interest in evaluating exoskeletons under more realistic conditions, either through on-site testing or simulations. However, the relatively low number of studies in real-world settings highlights a potential area for further research to better understand how these devices perform in practical, everyday use.

3.2. Overview of the Exoskeletons Studied

This subchapter provides a comprehensive overview of the exoskeletons examined in the reviewed studies, highlighting their mode of actuation (active or passive) and the specific body regions they are intended to support. This information is crucial for understanding the diverse applications and technological approaches of exoskeletons in occupational settings. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the exoskeletons featured in these studies, offering a concise yet comprehensive view of the current state of research in this domain.

Table 2.

Key characteristics of the exoskeletons presented in the reviewed studies.

The data indicates that most of the reviewed studies focused on evaluating a single exoskeleton, with 38 studies [11,14,15,16,17,18,21,22,23,24,25,42,43,44,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,59,61,62,64,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,73,75,76] adopting this approach. In contrast, 11 studies [9,10,20,45,47,57,58,60,63,68,74] examined more than one exoskeleton, suggesting a comparative analysis of different devices within those studies. This distribution reflects a prevalent research trend where a singular exoskeleton is typically selected for in-depth evaluation, possibly due to resource constraints or a desire to thoroughly investigate the specific features and performance of individual devices. However, the presence of studies that assess multiple exoskeletons highlights an emerging interest in comparing the effectiveness, usability, and suitability of various exoskeleton models within occupational settings. This comparative approach could provide valuable insights into the relative advantages and limitations of different technologies, guiding future design and application in the field.

The data on the exoskeletons studied in the reviewed literature reveals a diverse range of devices, with some exoskeletons being more frequently evaluated than others. Among the exoskeletons, the Paexo [9,11,43,53,54,60,74] is the most frequently studied, appearing in seven different studies. This is followed by Cray X [56,60,63,68,74], which is featured in five studies. Several exoskeletons, including BackX [68,69,70] Auxivo lift suit V2 [16,20,55], Cex [23,49,58], and Laevo V2 [50,75,76], were each assessed in three studies, indicating a moderate level of research interest.

Some exoskeletons, such as Airframe [47,57], BionicBack hTRIUS [20,63], Corfor [45,72], EksoVest [10,47], Shoulder X [47,61], Shoulder exoskeleton prototype (Exo4Work) [51,65], Skelex X [14,15], and XoTrunk [24,46], were each studied in two different investigations, reflecting ongoing but less concentrated research attention.

Most of the exoskeletons listed were studied in only one investigation, underscoring the broad exploration of different exoskeleton designs within the field. These single-study devices include prototypes and specialized models, such as the OmniSuit [71], Pad [42], Elbow-sideWINDER [17], and Head/neck supporting exoskeleton [18].

This distribution highlights the focus on certain exoskeletons that are either more commercially available or have shown promise in early studies, while also reflecting the experimental nature of many of the devices being evaluated. The variation in the frequency of studies on specific exoskeletons may be influenced by factors such as availability, intended use cases, and the specific ergonomic or functional challenges they address.

The studies of the type of actuation in the exoskeletons reveal a preference for passive exoskeletons. Of the exoskeletons reviewed, 56 are passive [9,10,11,14,15,16,18,20,21,22,23,25,42,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], while only 11 [17,24,46,56,60,62,63,68,74] are active. This disparity suggests that most research in occupational exoskeletons has focused on passive systems, which do not require external power sources and typically rely on mechanical structures to support or redistribute the user’s physical load [77].

The preference for passive exoskeletons may be driven by several factors, including their simpler design, lower cost, and potentially easier integration into various work environments. Passive systems are often more practical in settings where minimal maintenance and operational simplicity are crucial.

In contrast, active exoskeletons, powered by motors or actuators, potentially providing more dynamic assistance [77], appear less frequently in the studies. This may reflect the higher complexity, cost, and potential technical challenges associated with active systems, although they can offer greater versatility and support in certain applications.

Overall, the data indicates a predominant focus on passive exoskeletons in the current literature, with active systems representing a smaller, yet significant, area of interest. This trend may evolve as technology advances and the potential benefits of active exoskeletons become more accessible.

The body parts supported by the exoskeletons in the reviewed studies show a clear focus on devices designed to assist the back and upper arms. Specifically, 32 exoskeletons are intended to support the back [16,20,24,25,45,46,50,52,54,56,59,60,63,64,66,69,70,72,74,75,76], making it the most targeted area. This emphasis likely reflects the high incidence of back-related injuries in occupational settings [78], where lifting and repetitive movements are common [79].

Following closely, 26 exoskeletons provide support for the upper arm [9,10,11,14,15,21,22,42,43,47,48,51,53,57,59,61,62,65,67,73], which is also a critical area in many manual labor tasks that involve overhead work or heavy lifting [80]. A smaller subset of devices, two exoskeletons [44,71], supports both the upper arm and back, suggesting an integrated approach to reducing strain on both areas simultaneously.

Other body parts are less frequently addressed. Five exoskeletons are designed to support the legs [10,23,49,58], likely for tasks that involve prolonged standing or heavy leg movement. The head and neck [18] and the elbow [17] are the least supported areas, with only one exoskeleton dedicated to each. This indicates that while these regions may also be vulnerable to strain, they are not the primary focus of current exoskeleton technology in occupational settings.

The distribution reflects the prioritization of support for the back and upper arms, which are the most susceptible to injury in many physically demanding workplaces. This trend aligns with the broader goals of occupational exoskeletons to prevent musculoskeletal disorders and enhance worker safety and efficiency.

3.3. Overview of the Methodological Approach

In this section, a comprehensive summary of the methodological strategies employed in the reviewed studies is provided, as presented in Table 3. This table outlines the types of occupational tasks that were analyzed, reflecting the diversity of scenarios in which exoskeletons have been evaluated. Furthermore, the table details the WMSD risk assessment methods utilized across the studies. These methods are categorized into three primary groups: direct measurement, which is further divided into biomechanical and physiological measurements; observational methods; and self-reports and checklists. This segmentation offers a structured view of the approaches taken to assess the effectiveness and ergonomic impact of exoskeletons in mitigating the WMSD risk.

Table 3.

Methodological approach in the reviewed studies.

The data regarding the types of tasks evaluated in studies on occupational exoskeletons highlights a varied focus on different physical activities. The most frequently assessed tasks involve a combination of different tasks, with 17 studies adopting this approach. This suggests a comprehensive evaluation strategy where exoskeletons are tested across multiple task types to determine their overall effectiveness and versatility in various work scenarios.

Lifting tasks are the next most studied, featured in 12 studies. This focus reflects the significant role that lifting plays in many occupational settings and the associated risk of musculoskeletal disorders, particularly in the back and upper limbs. Similarly, overhead tasks are a central focus, with 11 studies examining exoskeletons’ ability to support activities that involve reaching or working above shoulder level—a common cause of strain in industrial and construction work.

Other tasks such as forward leaning and reaching tasks are each addressed in three studies, indicating a moderate interest in evaluating exoskeletons’ effectiveness in supporting these specific movements. Tasks performed at lower heights are also covered by three studies, which may include activities like squatting or kneeling, where exoskeletons could alleviate stress on the lower back and legs.

Finally, pushing/pulling tasks are the least frequently studied, with only two studies focusing on these activities. This suggests that while important, pushing and pulling may be considered less critical or more challenging to address with current exoskeleton designs compared to lifting or overhead tasks.

The data demonstrate a strong emphasis on evaluating exoskeletons in scenarios that pose significant ergonomic challenges, particularly those involving lifting and overhead work, while also recognizing the importance of multi-task assessments to gauge the devices’ practical applicability in diverse work environments. It is important to note that the distribution of the types of tasks extensively studied may be closely related to the specific type of exoskeleton being examined, particularly in terms of the body part it is designed to support.

Related to the WMSD risk assessment methods, the results reveal that only nine studies [10,15,18,21,22,25,46,53,73] adopted a single-method approach. While less common, this approach might have been chosen for its simplicity, focus, or resource constraints. In contrast, most of the studies applied a multi-method approach in their methodological design. This approach likely reflects the complexity and multifaceted nature of evaluating exoskeletons, as it allows for a more comprehensive assessment by combining various methods to capture different dimensions of their impact on WMSD. By utilizing multiple methods, researchers can triangulate their findings, increasing the robustness and reliability of the results [81].

We will now delve into each level of the WMSD risk assessment methods applied in the reviewed studies. Starting with direct measurement methods, focusing initially on those related to biomechanics, followed by an examination of physiological measurements.

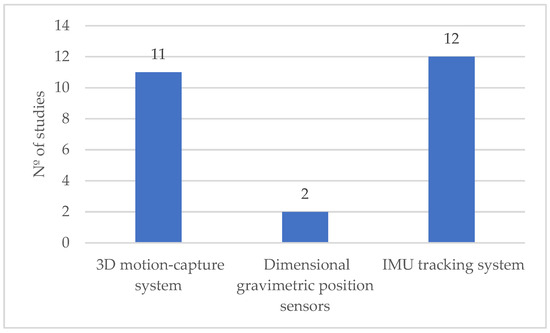

The findings indicate that kinematic measurements were the predominant biomechanical method used in the reviewed studies (Figure 2), with 24 studies employing this approach [9,11,16,17,24,43,45,47,48,49,50,52,55,60,61,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,72,75]. In contrast, force measurements were much less commonly applied, being used in only two studies [11,49]. This suggests a preference for analyzing movement patterns and body mechanics (kinematics) over direct force exertion measurements in the context of WMSD risk assessment related to occupational exoskeletons. Given the previous observation that kinematics was the predominant biomechanical method used, the data further reveals that IMU tracking systems were the most employed kinematic measurement tools, utilized in 12 studies [9,11,17,45,49,50,55,61,63,67,68,69]. Close behind, 3D motion capture systems were also frequently used, appearing in 11 studies [16,24,43,47,48,52,60,62,64,65,72]. In contrast, dimensional gravimetric position sensors were employed in only one study [75]. This trend highlights a strong reliance on IMU tracking systems and 3D motion capture for capturing detailed movement data in studies assessing WMSD risks associated with occupational exoskeletons.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the biomechanical direct measurement approaches by the number of studies.

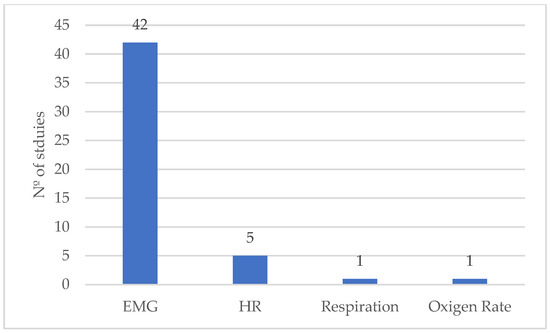

Related to physiological direct measurement methods (Figure 3), EMG was the most used technique, appearing in four studies [10,14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,75,76], indicating its critical role in assessing muscle activity during the use of occupational exoskeletons. In contrast, other physiological measures were far less prevalent, with heart rate (HR) being utilized in only five studies [42,51,54,59,75], and respiration [51] and the oxygen rate [43] each appearing in just one study. This disparity underscores the emphasis on EMG as the primary method for physiological assessment, while other metrics were used sparingly.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the physiological direct measurement approaches by the number of studies.

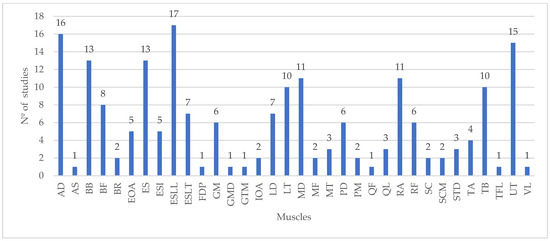

The analysis of the muscles studied through EMG in the reviewed literature is vital, as it not only informs future research on muscle selection for occupational exoskeleton studies but also enables the comparison of results across different studies. Therefore, Figure 4 presents the distribution of the muscles studied by the number of studies reviewed.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the muscles studied by the number of studies. Anterior deltoid (AD); anterior serratus (AS); biceps brachii (BB); biceps femoris (BF); brachioradialis (BR); external obliquus abdominis (EOA); erector spinae (ES); erector spinae iliocostalis (ESI); erector spinae longissimus lumborum (ESLL); erector spinae longissimus thoracis (ESLT); flexor digitorum profundus (FDP); gluteus maximus (GM); gluteus medius (GMD); gastrocnemius medialis (GTM); internal obliquus abdominis (IOA); latissimus dorsi (LD); lower trapezius (LT); middle deltoid (MD); multifidus (MF); middle trapezius (MT); posterior deltoid (PD); pectoralis major (PM); quadriceps femoris (QF); quadratus lumborum (QL); rectus abdominis (RA); rectus femoris (RF); splenius capitis (SC); sternocleidomastoid (SCM); semitendinosus (STD); tibialis anterior (TA); tensor fascia latae (TFL); triceps brachii (TB); upper trapezius (UT); vastus lateralis (VL).

Among the muscles, the Erector Spinae Longissimus lumborum (ESLL), a key muscle for maintaining posture and supporting the lower back, was the most frequently studied, appeared in 16 studies [15,16,20,24,25,46,47,49,51,59,61,65,66,67,71,76]. This trend highlights the importance of monitoring back muscles, particularly in tasks that place significant strain on the lower back, a common area of concern in occupational settings.

The anterior deltoid (AD), found in 15 studies [14,15,18,21,22,44,48,51,53,55,59,61,62,71,73], and the Erector Spinae (ES), present in 13 studies [22,23,44,45,50,52,57,58,59,63,72,73,75], were also frequently analyzed. The anterior deltoid plays a crucial role in shoulder flexion [35], especially in overhead tasks, which are common in industrial environments. The consistent focus on these muscles suggests a priority in understanding how exoskeletons can alleviate stress in these areas. It is important to highlight that the attribution of ES in the aforementioned studies is quite broad, with no specification as to which particular muscle of the erector spinae group is being referred to. However, these data reinforce the previously demonstrated trend of focusing on back muscles in studies evaluating occupational exoskeletons.

Other superficial muscles, such as the biceps brachii (BB) [17,21,22,23,43,44,48,49,51,57,58,59,62], triceps brachii (TB) [17,21,22,23,49,51,57,58,59,62], and upper trapezius (UT) [14,18,21,23,43,49,51,57,58,61,67,69,73,76], were also frequently studied, each appearing in 10 to 14 studies. These muscles are involved in a variety of arm movements [82], including lifting and carrying tasks, emphasizing their significance in studies focused on upper limb support.

Notably, some muscles, such as the anterior serratus (AS) [43], gluteus medius (GMD), and quadriceps femoris (QF) [50] were studied in only a single study each. These muscles, despite their importance in stabilizing the shoulder, pelvis, and knee, respectively, have been underrepresented. Future research could expand on these muscles to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how exoskeletons interact with the entire musculoskeletal system.

The overall trend in muscle selection reflects a focus on superficial muscles, which are more accessible for EMG measurement and are directly involved in common occupational tasks. However, the underrepresentation of certain muscles suggests opportunities for future studies to explore these less-studied areas, enhancing our understanding of exoskeleton performance and its effects on a broader range of muscle groups.

This analysis is crucial for guiding future research, providing a foundation for selecting muscles to study in upcoming investigations and facilitating the comparison of results across studies. By expanding the focus to include a wider variety of muscles, researchers can develop a more holistic understanding of exoskeletons’ impacts on workers’ musculoskeletal health.

Regarding the observational methods, only one study applied the Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) [20]. This reveals a significant gap in the use of observational tools within the reviewed literature. The limited application of REBA suggests that researchers may be prioritizing other assessment methods, such as direct measurements or self-reports, over observational techniques. This underutilization of observational methods highlights a potential area for future research, as these tools can provide valuable insights into the WMSD risks associated with exoskeleton use, particularly in complex or dynamic work environments.

The analysis of self-reports and checklist methods distribution (Figure 5) reveals distinct trends in their application across the studies. These methods are critical for capturing subjective perceptions related to discomfort, pain, and overall workload, providing insights that complement objective measurements [26].

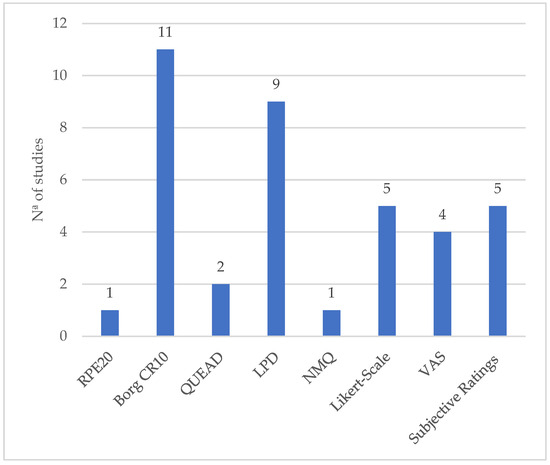

Figure 5.

Distribution of the self-report/checklist methods by number of studies.

The Borg Category Ratio-10 Scale (Borg CR10) emerges as the most frequently utilized tool, with 11 studies employing it [20,23,42,44,57,59,61,67,69,70,76]. This scale is designed to assess perceived exertion, especially during physically demanding tasks [83]. Its frequent use demonstrates its effectiveness in assessing how participants perceive the effort involved in using exoskeletons compared to not wearing them or when comparing different exoskeleton devices. The Local Perceived Discomfort (LPD) scale was utilized in nine studies [10,16,17,21,51,52,60,61,76], indicating a strong focus on evaluating the specific discomforts experienced by participants in localized body regions, which is particularly relevant in studies involving exoskeletons where targeted muscle groups or joints may be affected.

Subjective ratings were employed in five studies, as well as the Likert scale. These tools are flexible and widely applicable, allowing researchers to measure various subjective experiences. In the case of the reviewed studies that employed these two metrics, the focus was on evaluating the following parameters: comfort/discomfort [9,47,62,67,69,71], range of motion [9,62], acceptance [67,69], ease of use [64,70], lift assistance [9], accuracy [62], usability [16,70], task difficulty, design [64], exertion, and perceived pressure [72].

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used in four studies [54,66,74,76], indicating its utility in quantifying pain levels on a continuum, offering a simple yet effective way to capture variations in pain perception.

The Questionnaire for the Evaluation of Physical Assistive Devices (QUEAD) and the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) appeared in two [61,69] and one [54] studies, respectively. These tools are more specialized, with QUEAD focusing on examining usability, ease of use, comfort, and acceptance [84], abs NMQ on musculoskeletal symptoms [30], indicating their targeted use in particular study contexts.

Finally, the Ratio Perceived Exertion 20 (RPE20) scale was utilized in only one study [56], suggesting that it might be less commonly preferred for assessing perceived exertion in exoskeleton research, where other scales like Borg CR10 are more prominent.

This distribution highlights the varied approaches researchers take when assessing subjective outcomes in exoskeleton studies, with a clear preference for established methods like the Borg CR10 and LPD. These data provide a useful foundation for future studies, offering guidance on the selection of appropriate subjective assessment tools and facilitating the comparison of results across studies.

Globally, it is important to note that no study evaluating occupational exoskeletons relied solely on self-report or checklist methods, although some studies exclusively applied direct measurement methods. In most cases, a multimethod approach was used, combining direct measurements and self-report methods. Direct methods provide objective data that accurately reflect the exoskeleton’s performance in occupational settings. However, they can be resource intensive and may not capture the subjective experience of the wearer. On the other hand, self-report and checklist methods offer valuable insights into user perceptions, comfort, and usability, but they are inherently subjective and may be influenced by biases or inaccuracies.

The combination of both methods addresses the limitations of each approach. By integrating direct measurements with subjective assessments, a more comprehensive evaluation may be achieved, providing both objective data and a deeper understanding of user experience. The multimethod approach is essential in assessing WMSD risk factors [85] and therefore in evaluating the effectiveness of occupational exoskeletons in a holistic manner.

3.4. Overview of the Main Conclusions of the Reviewed Studies

The synthesis of various studies focused on the effectiveness of passive and active exoskeletons in reducing physical strain and preventing WMSD across different industrial tasks is presented in Table 4. The objective and main conclusions are presented. The studies collectively assess the impact of exoskeletons on muscle activity, discomfort, physical workload, and task performance in occupations that involve repetitive or physically demanding activities, such as overhead work, lifting, and walking.

Table 4.

Synthesis of the reviewed studies focused on the objective and main conclusions.

Regarding the ergonomic benefits, the reviewed studies can be divided into three categories. The first category includes those in which the use of exoskeletons resulted in ergonomic improvements. The second category encompasses studies where no significant ergonomic improvements were observed. Lastly, the third category comprises studies that reported improvements but also highlighted certain constraints associated with the use of this type of assistive technology.

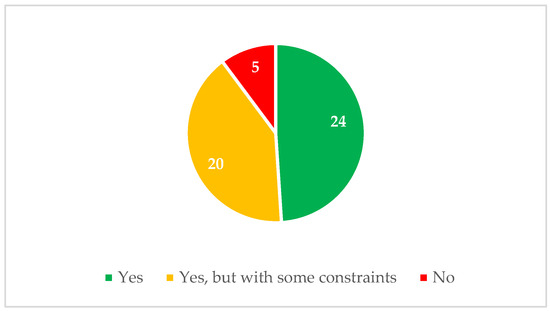

The results presented in Figure 6 show the distribution of the studies within the above categories presented. Specifically, 24 studies [11,15,16,17,20,21,22,24,25,43,46,49,53,55,56,59,62,64,66,67,69,71,72,73] reported clear ergonomic improvements following the use of exoskeletons. However, 20 studies [9,10,14,18,23,42,44,48,51,52,57,58,61,63,65,68,70,75,76,86] indicated that while there were improvements, they were accompanied by certain constraints, likely reflecting limitations in the technology or specific challenges in its application. A smaller number, of five studies [45,47,54,60,74], did not observe any ergonomic benefits at all.

Figure 6.

Distribution of the reviewed studies on ergonomic benefits.

This distribution highlights that while most studies (44 out of 49) identified some level of ergonomic improvement, a significant proportion of these studies raised concerns or limitations that warrant further investigation. The small percentage of studies reporting no improvements suggests that while the potential for ergonomic benefits exists, it may not be universally applicable across all scenarios or populations.

The overall conclusions of the reviewed studies will be outlined below:

- Effectiveness in reducing muscle activity and physical strain: The majority of the studies demonstrate that exoskeletons—whether for the upper body, back, or lower limbs—significantly reduce muscle activity and physical strain during specific tasks. For example, studies such as those by Yin et al. (2021) [22] and Kong et al. (2021) [23] show reductions in upper-limb muscle activity, while Lazzaroni et al. (2020) [24] and Ding et al. (2023) [25] highlight the reduction in lumbar load during manual lifting tasks;

- Constraints and trade-offs: Although exoskeletons often reduce muscle fatigue and improve ergonomics, many studies report trade-offs in comfort, range of motion, and usability. For instance, Perez Luque et al. (2020) [9] and Cardoso et al. (2020) [76] indicate that while exoskeletons help to reduce strain, they also impose constraints on the range of motion and increase discomfort during prolonged use. This suggests that while beneficial for specific tasks, the long-term comfort and adaptability of these devices remain a challenge;

- Task-specific benefits: Several studies underscore the importance of selecting exoskeletons based on the specific demands of the task. For example, Kong et al. (2021) [23] and Schwartz et al. (2021) [45] show that passive exoskeletons provide significant benefits for overhead tasks but can increase strain during tasks performed at higher or lower heights. Shim et al. (2023) [58] and Schrøder Jakobsen et al. (2024) [69] highlight how the efficacy of these devices depends on task-specific requirements such as task height and lifting technique;

- Active vs. passive exoskeletons: Some studies compare active and passive exoskeletons, revealing that active systems often provide more substantial reductions in muscle activity but may hinder mobility or task performance, particularly during dynamic tasks. For instance, Schwartz et al. (2023) [68] report that active exoskeletons provide greater reductions in trunk muscle activity but may alter trunk kinematics and affect performance in dynamic environments;

- User experience and ergonomics: Several studies emphasize the need for improvements in the design and user experience of exoskeletons. Govaerts et al. (2024) [74] and Rafique et al. (2024) [10] suggest that while exoskeletons can reduce physical strain, there is a need for better design to enhance comfort, usability, and biomechanical compatibility for long-term use. This includes optimizing factors like device-to-body forces and ensuring that the exoskeleton does not interfere with the natural movement patterns of workers.

Globally, exoskeletons are a promising solution for reducing WMSD risks and improving ergonomics in physically demanding tasks. However, their effectiveness depends on task-specific factors, and improvements in comfort, adaptability, and long-term usability are needed to maximize their potential benefits across a broader range of applications.

4. Conclusions

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies and findings related to the evaluation of occupational exoskeletons, with a particular focus on WMSD risk assessment methods. Several key findings emerged from the analysis, offering valuable insights for future research, practical application, and design optimization.

4.1. Key Findings

The majority of studies reviewed were published between 2022 and 2024, with 10 participants being the most common sample size of the reviewed studies. Laboratory-based studies dominated the research landscape, with passive exoskeletons being the most frequently tested. Notably, the Paexo and Cray X exoskeletons were the most studied models. Regarding the supported body part, the back and upper arms were the most commonly targeted segments by the exoskeletons examined in the studies. These findings may correlate with the types of tasks tested since overhead and lifting tasks were the most commonly examined.

The review of the studies highlights the diverse methodologies and tools employed in evaluating occupational exoskeletons. Direct measurement techniques such as EMG and kinematic assessments were the most frequently used, while observational methods were underrepresented. Self-report methods and checklists, notably the Borg CR-10 Scale and the LPD, were commonly employed. Overall, the majority of studies reported benefits in reducing WMSD risk factors, although some highlighted limitations such as incompatibility between the exoskeleton and the task, discomfort due to contact points, restricted range of motion, and usability concerns.

The findings provide a foundational understanding that can guide future research, ensuring that exoskeletons are evaluated comprehensively, with considerations for both objective and subjective outcomes. Additionally, the main findings of each study are also presented. This review sets the stage for further exploration into optimizing the design and implementation of exoskeletons in occupational settings.

4.2. Implications for Practice

The findings suggest that exoskeletons have the potential to significantly reduce the WMSD risk factors. However, the effectiveness of these devices is influenced by several factors, including the specific occupational task, exoskeleton design, and user comfort. The high prevalence of passive exoskeletons in the studies indicates that they are simpler to implement but may not always be sufficient for dynamic, high-demand tasks. In contrast, active exoskeletons, while more complex, could offer greater support for these tasks. These insights are critical for designing exoskeletons that are better suited to the diverse demands of various industries.

Globally, this review highlights the need for more real-world evaluations of exoskeleton performance to better understand their practical benefits and limitations, with the ultimate goal of guiding future research and informing the development of more effective ergonomic interventions.

4.3. Limitations

This study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, a pre-registered protocol detailing the main methodological features of this systematic review was not submitted to platforms such as PROSPERO. The absence of such prior registration may have introduced potential biases in the review process and highlights an area for improvement in future research to enhance methodological rigor. Second, the search strategy was based solely on the terms “Exoskeleton” and “WMSD”, chosen for being the most widely recognized in the literature. While the number of articles retrieved appears sufficiently representative to meet the study’s objectives, we recognize that a more extensive and detailed search strategy could improve the comprehensiveness of the results. This limitation offers a valuable opportunity for refinement in future research. Finally, a limitation of this study is the absence of a formal risk of bias assessment for the included articles. While the studies were qualitatively evaluated, a systematic and standardized approach to assessing the risk of bias was not employed. Future systematic reviews should incorporate a formal risk of bias assessment to enhance the transparency and robustness of their methodology.

4.4. Future Work

Future research should prioritize expanding real-world assessments to better understand the practical benefits and limitations of exoskeletons in diverse occupational settings. Particular attention should be given to active exoskeletons, as their application in occupational contexts remains in an early developmental stage, and there is a notable lack of studies exploring their potential in these environments. Additionally, addressing the ergonomic challenges and discomfort reported in some studies will be crucial in improving user acceptance and long-term efficacy. Building on these insights, a key direction for future work is the development of a comprehensive framework for evaluating occupational exoskeletons using the ergonomic assessment methodologies identified in this review. This framework would consolidate the most effective approaches, including direct measurement and self-report methods, to provide a standardized and practical tool for assessing exoskeletons in various occupational settings. By integrating findings from both laboratory-based evaluations and real-world applications, the framework aims to enhance the reliability and applicability of assessment results. Collaboration with industry stakeholders will also be essential to ensure the framework’s adaptability to diverse workplace contexts and to support the design of more effective and user-friendly exoskeletons.

The development of more effective exoskeletons has the potential to revolutionize occupational health and safety policies, particularly in industries where musculoskeletal disorders are prevalent. Improved exoskeleton designs could lead to safer working conditions, reducing injury rates and enhancing workforce productivity. As the evidence grows, these devices may become integral to workplace ergonomics strategies, driving the future of workplace safety standards and policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. (André Cardoso) and A.C. (Ana Colim); methodology, A.C. (André Cardoso).; validation, A.C. (André Cardoso), A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim); formal analysis, A.C. (André Cardoso); investigation, A.C. (André Cardoso); resources, A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim); writing—original draft preparation, A.C. (André Cardoso); writing—review and editing, A.C. (André Cardoso), A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim); visualization, A.C. (André Cardoso); supervision, A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim); project administration, A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim) funding acquisition, A.R., P.C. and A.C. (Ana Colim). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by national funds, through the Operational Competitiveness and Internationalization Programme (COMPETE 2020) [Project n° 179826; Funding Reference: SIFN-01-9999-FN-179826]. It was also supported under the base funding project of the DTx CoLAB-Collaborative Laboratory, under the Missão Interface of the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR), integrated in the notice 01/C05-i02/2022, which aims to deepen the effort to expand and consolidate the network of interface institutions between the academic, scientific, and technological system and the Portuguese business fabric. In addition, this research was supported by R&D Unit Project Scope UIDB/00319/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) Checklist.

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) Checklist.

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 3 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 3–5 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 3–5 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3–5 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3–5 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 4 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 4 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 28 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | 3–5 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 3–5 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 3–5 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 3–5 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 3–5 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | - | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | - | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | 28 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | - |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 3–5 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | - | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 5–7 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 28 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 5–7 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | 28 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | - | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | - | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | - | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | 28 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | - |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 27 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 28 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 28 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 27 | |

| Other Information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 28 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 28 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | 28 | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 29 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 29 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | - |

References

- Russo, F.; Di Tecco, C.; Fontana, L.; Adamo, G.; Papale, A.; Denaro, V.; Iavicoli, S. Prevalence of Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Italian Workers: Is There an Underestimation of the Related Occupational Risk Factors? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.; Kamper, S.J.; Wiggers, J.H.; O’Brien, K.M.; Lee, H.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.L.; Robson, E.; McAuley, J.H.; Hartvigsen, J.; et al. Musculoskeletal Conditions May Increase the Risk of Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; de Kok, J.; Vroonhof, P.; Snijders, J.; Roullis, G.; Clarke, M.; Peereboom, K.; van Dorst, P.; Isusi, I. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: Prevalence, Costs and Demographics in the EU; European Health: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg, M.; Violante, F.S.; Bonfiglioli, R.; Descatha, A.; Gold, J.; Evanoff, B.; Sluiter, J.K. Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Workers: Classification and Health Surveillance—Statements of the Scientific Committee on Musculoskeletal Disorders of the International Commission on Occupational Health. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colim, A.; Faria, C.; Braga, A.C.; Sousa, N.; Carneiro, P.; Costa, N.; Arezes, P. Towards an Ergonomic Assessment Framework for Industrial Assembly Workstations—A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogbla, L.; Gouvenelle, C.; Thorin, F.; Lesage, F.X.; Zak, M.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Charbotel, B.; Baker, J.S.; Pereira, B.; Dutheil, F. Occupational Risk Factors by Sectors: An Observational Study of 20,000 Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Di, N.; Guo, W.-W.; Ding, W.-B.; Jia, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Wang, D.; Wang, R.; Zhang, D.; et al. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Electronics Manufacturing Workers: A Cross-Sectional Analytical Study in China. BMC Public. Health 2023, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerha, D.J.; McNamara, N.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Kim, S. Adoption Potential of Occupational Exoskeletons in Diverse Enterprises Engaged in Manufacturing Tasks. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 82, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Luque, E.; Hogberg, D.; Iriondo Pascual, A.; Lamkull, D.; Garcia Rivera, F. Motion Behavior and Range of Motion When Using Exoskeletons in Manual Assembly Tasks. In Advances in Transdisciplinary Engineering; IOS Press BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 13, pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, S.; Rana, S.M.; Bjorsell, N.; Isaksson, M. Evaluating the Advantages of Passive Exoskeletons and Recommendations for Design Improvements. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2024, 11, 20556683241239875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latella, C.; Tirupachuri, Y.; Tagliapietra, L.; Rapetti, L.; Schirrmeister, B.; Bornmann, J.; Gorjan, D.; Camernik, J.; Maurice, P.; Fritzsche, L.; et al. Analysis of Human Whole-Body Joint Torques During Overhead Work with a Passive Exoskeleton. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2022, 52, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor-Unda, O.; Casa, B.; Fuentes, M.; Solorzano, S.; Narvaez-Espinoza, F.; Acosta-Vargas, P. Exoskeletons: Contribution to Occupational Health and Safety. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, L.; Melloni, R. Occupational Exoskeletons: Understanding the Impact on Workers and Suggesting Guidelines for Practitioners and Future Research Needs. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, M.; Oliveira, A.S.; Bai, S. Influence of an Upper Limb Exoskeleton on Muscle Activity during Various Construction and Manufacturing Tasks. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 114, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräf, J.; Grospretre, S.; Argubi-Wollesen, A.; Wollesen, B. Impact of a Passive Upper-Body Exoskeleton on Muscular Activity and Precision in Overhead Single and Dual Tasks: An Explorative Randomized Crossover Study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1405473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Sluijs, R.M.; Wehrli, M.; Brunner, A.; Lambercy, O. Evaluation of the Physiological Benefits of a Passive Back-Support Exoskeleton during Lifting and Working in Forward Leaning Postures. J. Biomech. 2023, 149, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Di Natali, C.; Sposito, M.; Caldwell, D.G.; Ortiz, J. Elbow-SideWINDER (Elbow-Side Wearable INDustrial Ergonomic Robot): Design, Control, and Validation of a Novel Elbow Exoskeleton. Front. Neurorobot 2023, 17, 1168213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garosi, E.; Kazemi, Z.; Mazloumi, A.; Keihani, A. Changes in Neck and Shoulder Muscles Fatigue Threshold When Using a Passive Head/Neck Supporting Exoskeleton During Repetitive Overhead Tasks. Hum. Factors 2023, 66, 2269–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Looze, M.P.; Bosch, T.; Krause, F.; Stadler, K.S.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Exoskeletons for Industrial Application and Their Potential Effects on Physical Work Load. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Colim, A.; Carneiro, P.; Costa, N.; Gomes, S.; Pires, A.; Arezes, P. Assessing the Short-Term Effects of Dual Back-Support Exoskeleton within Logistics Operations. Safety 2024, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öçal, A.E.; Lekesiz, H.; Çetin, S.T. The Development of an Innovative Occupational Passive Upper Extremity Exoskeleton and an Investigation of Its Effects on Muscles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Yang, L.; Qu, S. Development of an Ergonomic Wearable Robotic Device for Assisting Manual Workers. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 172988142110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.K.; Park, C.W.; Cho, M.U.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Hyun, D.J.; Bae, K.; Choi, J.K.; Ko, S.M.; Choi, K.H. Guidelines for Working Heights of the Lower-Limb Exoskeleton (Cex) Based on Ergonomic Evaluations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroni, M.; Tabasi, A.; Toxiri, S.; Caldwell, D.G.; De Momi, E.; Van Dijk, W.; De Looze, M.P.; Kingma, I.; Van Dieën, J.H.; Ortiz, J. Evaluation of an Acceleration-Based Assistive Strategy to Control a Back-Support Exoskeleton for Manual Material Handling. Wearable Technol. 2020, 1, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Reyes, F.A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Seyram, O.; Yu, H. A Novel Passive Back-Support Exoskeleton with a Spring-Cable-Differential for Lifting Assistance. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 3781–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G.C. Ergonomic Methods for Assessing Exposure to Risk Factors for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. Occup. Med. 2005, 55, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takala, E.P.; Pehkonen, I.; Forsman, M.; Hansson, G.Å.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Neumann, W.P.; Sjøgaard, G.; Veiersted, K.B.; Westgaard, R.H.; Winkel, J. Systematic Evaluation of Observational Methods Assessing Biomechanical Exposures at Work. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2010, 36, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anacleto Filho, P.C.; Colim, A.; Jesus, C.; Lopes, S.I.; Carneiro, P. Digital and Virtual Technologies for Work-Related Biomechanical Risk Assessment: A Scoping Review. Safety 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Colim, A.; Bicho, E.; Braga, A.; Pereira, D.; Monteiro, S.; Carneiro, P.; Costa, N.; Arezes, P. Enhancing Worker Well-Being: A Study on Assistive Assembly to Mitigate Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Modulate Cobot Assistive Behavior. In Proceedings of the Human Systems Engineering and Design (IHSED2024) Future Trends and Applications, Split, Croatia, 24–26 September 2024; AHFE International: Split, Croatia, 2024; Volume 158. [Google Scholar]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-S6rensen, F.; Andersson, G.; J6rgensen, K. Standardised Nordic Questionnaires for the Analysis of Musculoskeletal Symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 1987, 18, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Ergonomic Assessment Checklist. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/fy14_sh-26336-sh4_Ergonomic-Assessment-Checklist.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA). Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BauA. Key Indicator Method for Assessing and Designing Physical Workloads during Manual Handling Operations. BAuA 2019, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Colim, A.; Arezes, P.; Flores, P.; Monteiro, P.R.R.; Mesquita, I.; Braga, A.C. Obesity Effects on Muscular Activity during Lifting and Lowering Tasks. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 27, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colim, A.; Pereira, D.; Lima, P.; Cardoso, A.; Almeida, R.; Fernandes, D.; Mould, S.; Arezes, P. Designing a User-Centered Inspection Device’s Handle for the Aircraft Manufacturing Industry. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colim, A.; Cardoso, A.; Arezes, P.; Braga, A.C.; Peixoto, A.C.; Peixoto, V.; Wolbert, F.; Carneiro, P.; Costa, N.; Sousa, N. Digitalization of Musculoskeletal Risk Assessment in a Robotic-Assisted Assembly Workstation. Safety 2021, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenborg, S.E.; Greve, C.; Reneman, M.F.; Roossien, C.C. Side-Effects and Adverse Events of a Shoulder- and Back-Support Exoskeleton in Workers: A Systematic Review. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 111, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermavnar, T.; de Vries, A.W.; de Looze, M.P.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Effects of Industrial Back-Support Exoskeletons on Body Loading and User Experience: An Updated Systematic Review. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 685–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.T.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.; Torres Marques, A.; Santos Baptista, J. Occupational Accidents Related to Heavy Machinery: A Systematic Review. Safety 2021, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, L.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R. Emerging Research Fields in Safety and Ergonomics in Industrial Collaborative Robotics: A Systematic Literature Review. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyon, A.; Poirson, E.; Petiot, J.F. Experimental Study of the Physical Impact of a Passive Exoskeleton on Manual Sanding Operations. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 70, pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Schmalz, T.; Schändlinger, J.; Schuler, M.; Bornmann, J.; Schirrmeister, B.; Kannenberg, A.; Ernst, M. Biomechanical and Metabolic Effectiveness of an Industrial Exoskeleton for Overhead Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulkarim, S.A.; Farhan, A.M.; Ramadan, M.Z. Development and Investigation of a Wearable Aid for a Load Carriage Task. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.; Theurel, J.; Desbrosses, K. Effectiveness of Soft versus Rigid Back-Support Exoskeletons during a Lifting Task. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]