Abstract

The aim of this review was to explore the acceptability, opportunities, and challenges associated with wearable activity-monitoring technology to increase physical activity (PA) behavior in cancer survivors. A search of Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and SportDiscus was conducted from 1 January 2011 through 3 October 2022. The search was limited to English language, and peer-reviewed original research. Studies were included if they reported the use of an activity monitor in adults (+18 years) with a history of cancer with the intent to motivate PA behavior. Our search identified 1832 published articles, of which 28 met inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eighteen of these studies included post-treatment cancer survivors, eight were on active cancer treatment, and two were long-term cancer survivor studies. ActiGraph accelerometers were the primary technology used to monitor PA behaviors, with Fitbit as the most commonly utilized self-monitoring wearable technology. Overall, wearable activity monitors were found to be an acceptable and useful tool in improving self-awareness, motivating behavioral change, and increasing PA levels. Self-monitoring wearable activity devices have a positive impact on short-term PA behaviors in cancer survivors, but the increase in PA gradually attenuated through the maintenance phase. Further study is needed to evaluate and increase the sustainability of the use of wearable technologies to support PA in cancer survivors.

1. Introduction

While cancer remains one of the leading causes of disease burden worldwide, with advancements in early detection and treatment we are seeing more people living longer following a cancer diagnosis [1,2]. As the number of cancer survivors (defined as individuals with cancer from diagnosis to the end of life) continues to grow, additional health concerns are becoming increasingly evident. These include the acute/late effects from the cancer and associated treatment(s), cancer recurrence, second cancers, co-morbid disease, and a multitude of psychosocial issues [1,3,4]. Accordingly, the current challenge for cancer survivorship is to identify novel approaches to help improve overall health and quality of life for survivors.

A growing body of evidence shows that participating in regular physical activity (PA) can lead to physical and emotional improvements for cancer survivors, including but not limited to, improvements in aerobic endurance, muscular strength, self-esteem, functional ability, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and overall quality of life [5,6,7,8,9]. Evidence also indicates that PA confers a survival benefit [10,11]. Despite the positive impact of PA on quality of life and its impact on survival, the majority of cancer survivors do not attain the recommended amount of daily PA (i.e., 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA/week or 90 min of vigorous PA/week) [5,12] required to reap these health benefits [13,14,15,16,17].

Learning about preferences and motivations for engaging in PA among cancer survivors is important when developing interventions to change behavior and increase PA. In the past, behavior change interventions have successfully used face-to-face and telephone counselling, email, and print-based methods to increase PA levels among cancer survivors [14,18,19,20,21,22]. However, these methods are often resource intensive, time consuming, and require participants to live near counselling centers; therefore, methods capable of broad reach with low cost are required. With the rapid growth of the internet, access to information has substantially improved and web-based interventions have emerged as the most predominant technology to promote PA behavior change. While several meta-analyses and reviews have summarized the potential utility of web-based technologies for delivering PA interventions amongst both the general population and various chronic disease populations [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], these approaches are not without limitations. A recurring theme in eHealth and mHealth research is poor user engagement and retention [26]. In a recent review of eHealth literature, while it was found that participants engaged with the intervention platform, this engagement decreased over time [30]. Though there are many possible explanations for the difficulties with engagement, one possible explanation may be the inconvenience of using self-monitoring to track activity levels that must be manually entered onto a website. This barrier could be addressed through the use of wearable activity-monitoring technologies. A recent Australian survey indicated that one of the most important characteristics of wearable activity monitors is the ability to automatically sync data, thereby reducing the self-monitoring burden associated with web-based interventions [31].

With increased accessibility, user convenience, continuous monitoring and behavioral feedback, technologies such as wearable activity monitors (i.e., pedometer and accelerometer-based activity trackers) are a promising area in facilitating the delivery of behavioral change interventions designed to promote PA [32]. Wearable technologies (e.g., Apple watch [33], Fitbit [34], Garmin [35]) present data beyond step counts offered by basic pedometers, combined with automated and visual feedback that is lacking with traditional accelerometers. Moreover, these technologies offer several key elements that have been identified as being instrumental for supporting PA behavioral change (e.g., self-monitoring, goal-setting, prompting, social support, social comparison, and rewards) [36,37]. Although wearable PA monitoring technologies are commonly used in research to objectively track PA behavior, fewer studies have explored their potential to motivate and help sustain behavioral change. The overall aim of this scoping review was to explore the acceptability, opportunities, and challenges associated with wearable activity monitors to increase PA behavior in cancer survivors. While there are previous reviews, see Singh et al. 2022, the novelty of our study is that we include two additional years of more recent studies and an analysis of acceptability, opportunities and challenges [38].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The use of wearable activity-monitoring technologies in promoting active lifestyles (versus simply monitoring PA) is a rapidly growing field of study, thus a scoping review of the available evidence was conducted to synthesize and map the current state of knowledge and to identify innovative practices, implementation challenges, and gaps in the literature to inform future research and practice [39]. The five-stage framework as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [39] and Levac et al. [40] was applied. The review stages included: (1) identification of the research questions; (2) identification of relevant articles; (3) selection of relevant articles for review; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the findings.

2.2. Identification of the Research Question

This scoping review aimed to address the following questions:

- What is the scope and acceptability of the use of wearable activity monitors for individuals with cancer?

- Does the use of a wearable activity monitor motivate gains in PA behaviors in cancer survivors?

2.3. Identification of Relevant Articles

A search strategy was developed and implemented to identify literature relevant to the use of wearable activity-monitoring technologies targeting cancer survivors for promoting active lifestyles. Using an iterative process, keywords were identified and combined around the three components of the research objective: (1) population; (2) wearable technology; and (3) behavior. A description of the keywords used can be found in Table 1. Keywords were searched using Boolean operators to maximize search results. The following databases were used to search the literature: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and SportDiscus. Databases were searched for English language articles using the identified keywords between 1 January 2011 and 3 October 2022. The search was limited to original research published in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Table 1.

Scoping review search strategy.

2.4. Selection of Relevant Articles for Review

Article titles and abstracts were independently screened by three authors (MSM, CF, XY) for inclusion in the review. Any discrepancy was settled by consensus. Research articles were required to focus on adults (18+ years) with a history of cancer and include the use of a wearable device that objectively monitored PA behavior with the intent to motivate behavior change through the provision of relevant feedback to the user (e.g., number of steps taken, sitting time, movement prompts). Research protocols and studies that focused on monitoring behavior but did not include individual feedback, including features to motivate behavior change, were excluded from the review.

2.5. Charting the Data

Using an iterative process, data from the search results were extracted onto a data abstraction form. A descriptive analytical approach [39] was used to extract, synthesize, and share the data for team review. Extracted data included: (1) authors and year of publication; (2) objectives; (3) study design/overview of methods; (4) type and duration of intervention; (5) key outcome measures; and (6) key findings. Study quality assessment was conducted using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment [41]. The elements used for the assessment included: (1) sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel for all outcomes, (4) blinding of outcome assessors for all outcomes, (5) incomplete outcome data for all outcomes, (6) selective outcome reporting, and (7) other sources of bias [38,42,43]. With the maximum risk score of 7, a score of 0–2 indicated low risk, 3–5 indicated moderate risk, and 6–7 indicated high risk. The quality assessment was conducted by a co-author (XY).

The key outcomes of interest were changes in PA, retention rate, and perceived acceptability. Findings were also summarized in the context of study quality to gauge the risk of bias and understand the strength of the evidence provided. Some of the challenges in appraising this broad evidence base include the predominance of pre-post studies, and lack of blinding in RCT studies.

3. Results

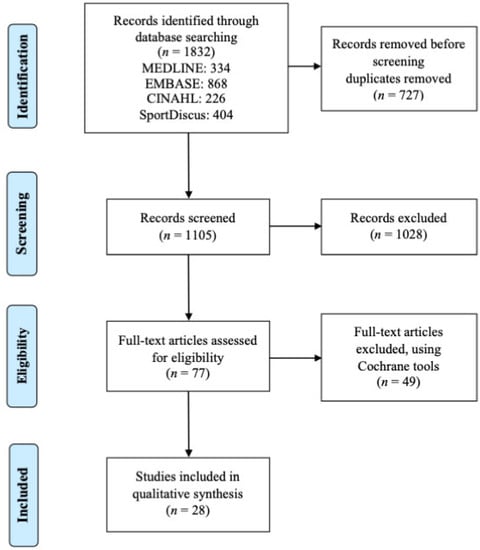

The search resulted in a total of 1832 published articles with 1804 excluded based on review of the articles and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria at progressively more detailed levels (i.e., review of article title, abstract, full manuscript), see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

A total of 28 original research articles met the inclusion criteria and were deemed eligible for the scoping review. A summary of original research is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of articles included in the review.

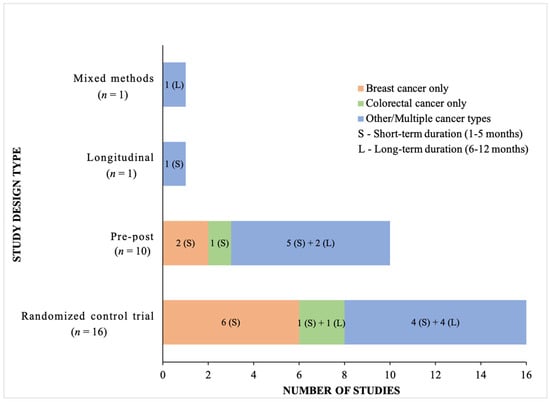

Of the 28 original articles included in the review, over half were randomized control trials and one third were pre-post designs (see Figure 2). The most common cancer type was breast cancer (eight studies) followed by colorectal cancer (three studies), with the remaining studies including a handful of other individual cancers (peritoneal cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer) or multiple cancer types. The duration of interventions included short term interventions (defined as those lasting one to five months) and longer-term interventions (defined as those lasting six to 12 months), Figure 2. Eighteen studies included post-treatment cancer survivors, eight included those on active cancer treatment (five were pre-surgery), two included all phases of cancer treatment.

Figure 2.

Study designs tabulated by cancer type and duration of intervention.

To measure PA as an outcome, accelerometers were the primary device used in 46% of the original studies. Of the remaining studies, 4% used pedometers and 41% used a combination of self-monitoring devices to assess changes in PA, including Fitbit [45,46,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,63,65,66,68,71], Neofit [58], Garmin Vivofit [60,61], Xiaomi wristband [70], treadmill and heart rate monitors [44,47,49,50,58,69].

Of the original studies reviewed, 25 reported some type of PA outcome (i.e., number of steps, overall PA, walking time, activity intensity, etc.). All but three studies reported that the use of wearable activity-monitoring devices increased participant levels of PA. It should be noted that although the three studies did not find an increase in participant PA levels, they did observe a slower rate of PA decline in the participants using the pedometers. Similarly, the studies that did not find an increase in PA in participants using activity monitors, reported that the monitors may have played a role in maintaining study adherence [52,57].

Adherence (or retention) rate was used to assess the acceptability in almost all studies (96%). With one exception, these studies all reported high adherence rates and therefore indicate good acceptability of the technology. Questionnaires were used to measure satisfaction in 50% of the studies, with 14% requesting further feedback and 36% performing additional semi-structured interviews.

Using the Cochrane risk score, see Table 2, 15 of the studies (54%) were rated as low quality, 10 (36%) were rated as moderate quality, and three (11%) were rated as high quality. Sequence generation was the quality component most frequently rated as high risk. In most pre-post studies this was a consequence of the lack of comparison groups. In general, most studies lacked blinding due to the nature of the intervention (i.e., a wearable monitoring device).

4. Discussion

As the majority of cancer survivors are not sufficiently active to attain the associated health benefits, motivating survivors to adopt and maintain a physically active lifestyle remains a considerable challenge [72]. Accordingly, novel approaches to foster and maintain PA are urgently needed. This review highlights that wearable devices are important tools to help promote and increase PA in cancer survivors, while also emerging as valuable tools to raise awareness in individuals of their own activity levels. Hence, wearable devices present valuable opportunities for improving the health of cancer survivors, through overall increases in PA. While interventions to change PA behavior have employed several strategies with variable success, active self-management approaches (i.e., engaging the individual in their own behavioral change) were found to be effective [73]. Specifically, the most successful interventions are those that have employed techniques to elicit behavioral change. Although the self-monitoring device-derived PA increases were typically robust and steady at initiation, generally activity rates decreased throughout the maintenance phase. For instance, several studies reported independent effects of self-monitoring wearable devices increasing regular exercise [64,66,68], reducing sitting time [60] and increasing adherence to PA guidelines [48,55] in the first three months. Despite this, there were very few studies examining the maintenance of these effects long-term. Lynch et al. [61] reported an abbreviated increase in PA during the following 3-month maintenance period. Similarly, studies found the adherence rate for wearing self-monitoring devices declined after three months [46] and 12 months [70]. Future studies are required to assess the maintenance of device-driven increases in PA.

While as many as 93 distinct behavior change techniques have been recognized, several systematic reviews have identified a smaller number of techniques that are associated with effective PA interventions [74]. For instance, Michie et al. [73] found that of the self-regulatory techniques reviewed, self-monitoring was the most important. They also found that combining self-monitoring with at least one additional self-regulatory technique (e.g., goal setting, feedback on performance) was associated with improved intervention effectiveness. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Bravata et al. [75] found that while the use of pedometers improved walking behaviors, the benefits were limited to those studies that used pedometers in conjunction with additional supportive behavioral change techniques. For example, the addition of a daily activity record has been found to improve intervention effectiveness as it provides a record of success, additional feedback on an individual’s behavior patterns, identifies areas for improvement, and assists with personalized goal setting [51,55]. Marthick et al. [62] also reported a higher retention rate as a result of additional individual input on the PA. The results of this current scoping review are consistent with these findings, noting that while activity monitors proved effective to foster positive change in walking behaviors, they were not used in isolation. Few of the reviewed studies [46,50,60,61,66] explicitly emphasized the use of behavior change techniques; however, when used in conjunction with these techniques (i.e., self-regulation, self-efficacy, modelling, social support, etc.), the studies reviewed herein provide additional evidence that pedometers, and other activity monitors, offer an accessible, user friendly (i.e., low-tech/low-literacy), real-time performance feedback tool that fosters PA behavior change.

The perceived acceptability was manifested by positive results in satisfaction [46,65] and compliance [57,58] rates. The majority of participants were willing to spend time installing the relevant software [49] and to continue using the wearable devices after the intervention ended [58]. Accordingly, several studies reported that feedback was particularly beneficial for increasing PA, with the majority of research participants reporting that text messages and self-monitoring data had a motivating effect [51,68,71]. Further, Groarke et al. [53] reported a very positive user experience during post-surgery, which was associated with general psychological well-being. Likewise, qualitative interviews from Marthick et al. [62] noted that most participants found the activity monitors (Misfit Shine) stimulating regardless of accuracy problems, and they enjoyed the sense of achievement that comes from receiving personalized messages. Although the qualitative analysis had limited generalizability and significant potential for selective result reporting, they revealed analogous trends to the quantitative findings. It is clear that the acceptability of the wearable devices was high, which highlights the valuable opportunity these devices present for supporting interventions aimed at increasing PA.

Activity monitors have been shown to be a valuable tool in improving awareness of activity levels and providing additional motivation to improve PA behaviors; however, they are not without limitations. For example, while providing a reasonably accurate estimation of PA level through a measure of step count, activity monitors such as pedometers are not able to detect non-ambulatory activities such as cycling, weight training, or swimming. Likewise, basic activity monitors are not able to give a measure of overall activity intensity [76]. Importantly, while generally increasing the amount of daily movement (i.e., steps per day) is an effective way to reduce the effects of sedentary behavior, activity intensity must be at least moderate to achieve optimal health and fitness benefits and should thus be monitored [77]. Although activity monitors, such as accelerometers, are able to measure activity intensity, their use is often limited to research settings where the data can be downloaded and appropriately interpreted [76]. It is also worth noting that blinding was nearly impossible during the interventions owing to the obvious presence of technology. Hence, there was a strong possibility that individuals in the intervention groups maintained higher levels of PA because they were aware that they were being observed. However, being observed, or gaining feedback, was found to increase PA, which is a positive outcome.

Newer generation wearable activity monitors have improved upon traditional pedometers and accelerometers through the addition of an interactive, user-friendly, mobile interface that provides a visual representation of real-time data [78]. Importantly, recorded data can be wirelessly synced to a mobile device (e.g., smartphone) or computer for long-term data storage, detailed behavior tracking, and personalized feedback; foregoing the need for manual tracking and data input required by traditional pedometers. Moreover, many of the newer activity monitors capture data beyond PA (e.g., heart rate, sleep, sedentary time) and can be synced with companion web-based or mobile apps that offer additional tools to track and offer supplementary feedback on related lifestyle behaviors (e.g., diet, sleep, stress), provide health education, and model/demonstrate target behaviors [37,79,80]. Likewise, sophisticated algorithms continue to advance the overall utility of the captured data by further personalizing activity and related health goals. For example, “Personal Activity Intelligence” uses heart rate data collected by an activity monitor and personal information (age, sex, heart rate reserve) to develop a personalized activity score that is used to guide the individual on the amount of exercise needed to decrease the risk of death from cardiovascular disease [81]. Importantly, activity monitors and their associated apps include several evidence-based behavioral change techniques known to be associated with successful behavioral change (e.g., self-monitoring, goal-setting, behavioral feedback and prompts, social support, social comparison, rewards, provision of health information and instruction) [37,79]. As outlined in this and similar reviews, there is a growing body of literature that demonstrates the feasibility and potential utility of both traditional and newer generation activity monitors in fostering PA behavior change in individuals with a chronic illness [37,79,82,83,84,85].

Despite their documented promise to help facilitate PA behavior change, the implementation of wearable technologies is not without challenges. While a major strength of such devices is the wealth of individual level data that is captured (e.g., behavioral and physiological), issues of data management have emerged. For example, the personal and health data associated with wearable activity monitors are often collected and stored by the manufacturer raising concerns about privacy, the security of the data itself, and data ownership; with the possibility of data being shared with third parties [85]. As many technologies involve automatic uploading of personal data to a central server for processing to provide the necessary feedback to users, ensuring that personal data remains private and not available for sale to third party companies without explicit consent is crucial. Thus, ethical, legal and social issues related to data ownership and data access need to be further explored.

These technologies ultimately need to be widely adopted to realize the full potential of wearable activity monitors. However, the fear of use of new technology may inhibit some individuals from embracing wearable activity monitors, and challenges related to internet access, mobile device use or cost may be issues for some people. Consequently, a move towards the use of high-tech wearable devices in cancer control activities may disenfranchise those individuals who are wary of, or dislike technological devices, or face other barriers to access. Interestingly, while older adults are often slower in adopting new technologies, studies have shown that younger adults appear to use activity monitors to improve fitness, whereas older adults have adopted their use to help improve overall health [85]. Likewise, while individual preferences for the use of technology may vary, data shows that user expectations and overall usability (e.g., user-friendly, visual display, automated feedback, overall comfort, data syncing, data accuracy, etc.) are also key to promote overall acceptability and feasibility of use [85,86]. Furthermore, the impacts of several challenges in cancer survivorship care, such as financial cost, internet access, and reading skills, have yet to be explored in the studies we reviewed, whereas these underlying inequalities are paramount in public health.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

The increasing availability and relative low cost of activity monitors is leading to a rapidly growing consumer base [87]. Studies included in this review yielded generally positive results in self-efficacy, coherence, and perceived utility, and both quantitative and qualitative findings show that self-monitoring wearable technologies increase PA. While these effects were typically robust and steady at initial use, they gradually reduced throughout the maintenance phase. Further study is needed to evaluate the sustainability of wearable activity monitor interventions to support PA increases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J.B.D., M.R.K., S.A.G., E.S. and C.C.F.; formal analysis, C.C.F., X.Y. and M.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.K., C.C.F. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Trevor Dummer is the Canadian Cancer Society Chair in Cancer Primary Prevention. Cynthia Forbes is a Career Development Research Fellow supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Report 2014; Stewart, B.W., Wild, C., International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, Eds.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2014; ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, J.H.; Bellizzi, K.M. Cancer Survivorship Issues: Life After Treatment and Implications for an Aging Population. JCO 2014, 32, 2662–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.E.; Forsythe, L.P.; Reeve, B.B.; Alfano, C.M.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Sabatino, S.A.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rowland, J.H. Mental and Physical Health–Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guideline for Cancer Survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, M.; Zauli, G.; Martelli, A.M.; Vitale, M.; McCubrey, J.A.; Ultimo, S.; Capitani, S.; Neri, L.M. Impact of Physical Exercise in Cancer Survivors during and after Antineoplastic Treatments. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 14005–14034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Yin, Y.; Feng, L. Cancer Survivors Could Get Survival Benefits from Postdiagnosis Physical Activity: A Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1940903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Newton, R.U.; Spence, R.R.; Galvão, D.A. The Exercise and Sports Science Australia Position Statement: Exercise Medicine in Cancer Management. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 1175–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormie, P.; Atkinson, M.; Bucci, L.; Cust, A.; Eakin, E.; Hayes, S.; McCarthy, A.L.; Murnane, A.; Patchell, S.; Adams, D. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia Position Statement on Exercise in Cancer Care. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, K.T.; Lam, K.; Kong, J.C. Exercise and Colorectal Cancer Survival: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, K.A.; Warner, A.B.; Jones, L.W.; Dewhirst, M.W. Exercise as Adjunct Therapy in Cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 29, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courneya, K.S.; Friedenreich, C.M. Physical Activity and Cancer: An Introduction. In Physical Activity and Cancer; Courneya, K.S., Friedenreich, C.M., Eds.; Recent Results in Cancer Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 186, pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-3-642-04230-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, B.M.; Ciccolo, J.T. Physical Activity Motivation and Cancer Survivorship. In Physical Activity and Cancer; Courneya, K.S., Friedenreich, C.M., Eds.; Recent Results in Cancer Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 186, pp. 367–387. ISBN 978-3-642-04230-0. [Google Scholar]

- LeMasters, T.J.; Madhavan, S.S.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Kurian, S. Health Behaviors among Breast, Prostate, and Colorectal Cancer Survivors: A US Population-Based Case-Control Study, with Comparisons by Cancer Type and Gender. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowls, D.S.; Brame, L.S.; Martinez, S.A.; Beebe, L.A. Lifestyle Behaviors among US Cancer Survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil, S.E.; Gotay, C.C.; Campbell, K.L. Physical Activity Levels of Cancer Survivors in Canada: Findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebø, A.M.L.; Dyrstad, S.M.; Søreide, J.A.; Bru, E. Predicting Exercise Adherence in Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Motivational and Behavioural Factors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courneya, K.S.; Stevinson, C.; Mcneely, M.L.; Sellar, C.M.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Peddle-Mcintyre, C.J.; Chua, N.; Reiman, T. Effects of Supervised Exercise on Motivational Outcomes and Longer-Term Behavior. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2012, 44, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, L.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Rhodes, R.E.; North, S.; Courneya, K.S. Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of Adding Behavioral Counseling to Supervised Physical Activity in Kidney Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E8–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluethmann, S.M.; Vernon, S.W.; Gabriel, K.P.; Murphy, C.C.; Bartholomew, L.K. Taking the next Step: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Physical Activity and Behavior Change Interventions in Recent Post-Treatment Breast Cancer Survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, F.G.; James, E.L.; Chapman, K.; Courneya, K.S.; Lubans, D.R. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Social Cognitive Theory-Based Physical Activity and/or Nutrition Behavior Change Interventions for Cancer Survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 305–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, J.; Kirk, A.; Masthoff, J.; MacRury, S. The Use of Technology to Promote Physical Activity in Type 2 Diabetes Management: A Systematic Review. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 1420–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.A.; Spence, J.C.; Vandelanotte, C.; Caperchione, C.M.; Mummery, W. Meta-Analysis of Internet-Delivered Interventions to Increase Physical Activity Levels. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, W.; Groen, W.G.; Aaronson, N.K.; van Harten, W.H. A Systematic Review of Web-Based Interventions for Patient Empowerment and Physical Activity in Chronic Diseases: Relevance for Cancer Survivors. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandelanotte, C.; Kirwan, M.; Rebar, A.; Alley, S.; Short, C.; Fallon, L.; Buzza, G.; Schoeppe, S.; Maher, C.; Duncan, M.J. Examining the Use of Evidence-Based and Social Media Supported Tools in Freely Accessible Physical Activity Intervention Websites. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandelanotte, C.; Spathonis, K.M.; Eakin, E.G.; Owen, N. Website-Delivered Physical Activity Interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, C.A.; Vandelanotte, C.; Caperchione, C.M.; Mummery, W.K. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes—A Randomised Controlled Trial. Prev. Med. 2014, 60, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, L.F.; Crutzen, R.; de Vries, N.K. Online Prevention Aimed at Lifestyle Behaviors: A Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.C.; Raeside, R.; Hyun, K.K.; Partridge, S.R.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Hafiz, N.; Tu, Q.; Tat-Ko, J.; Sum, S.C.M.; Sherman, K.A.; et al. Electronic Health Interventions for Patients with Breast Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. JCO 2022, 40, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, S.; Schoeppe, S.; Guertler, D.; Jennings, C.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. Interest and Preferences for Using Advanced Physical Activity Tracking Devices: Results of a National Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, Z.H.; Lyons, E.J.; Jarvis, J.M.; Baillargeon, J. Using an Electronic Activity Monitor System as an Intervention Modality: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare—Apple Watch. Available online: https://www.apple.com/ca/healthcare/apple-watch/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Fitbit Official Site for Activity Trackers & More. Available online: https://www.fitbit.com/global/en-ca/home (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Garmin|Canada. Available online: https://www.garmin.com/en-CA/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Mercer, K.; Li, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Burns, C.; Grindrod, K. Behavior Change Techniques Present in Wearable Activity Trackers: A Critical Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, E.J.; Lewis, Z.H.; Mayrsohn, B.G.; Rowland, J.L. Behavior Change Techniques Implemented in Electronic Lifestyle Activity Monitors: A Systematic Content Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Zopf, E.M.; Howden, E.J. Effect and Feasibility of Wearable Physical Activity Trackers and Pedometers for Increasing Physical Activity and Improving Health Outcomes in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, D.S.; McDonough, D.J.; Gao, Z. Effect of Wearable Technology-Based Physical Activity Interventions on Breast Cancer Survivors’ Physiological, Cognitive, and Emotional Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.S.S.; Moore, K.; McGavigan, A.; Clark, R.A.; Ganesan, A.N. Effectiveness of Wearable Trackers on Physical Activity in Healthy Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e15576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Rhim, A.D.; Manning, S.L.; Brennan, L.; Mansour, A.I.; Rustgi, A.K.; Damjanov, N.; Troxel, A.B.; Rickels, M.R.; Ky, B.; et al. Effects of Exercise on Circulating Tumor Cells among Patients with Resected Stage I-III Colon Cancer. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadmus-Bertram, L.; Tevaarwerk, A.J.; Sesto, M.E.; Gangnon, R.; Van Remortel, B.; Date, P. Building a Physical Activity Intervention into Clinical Care for Breast and Colorectal Cancer Survivors in Wisconsin: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.M.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Langlais, C.S.; Zhao, S.; Ramsdill, J.W.; Daniel, K.; Macaire, G.; Wang, E.; Paich, K.; Kessler, E.R.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Remotely Delivered, Web-Based Behavioral Intervention for Men with Prostate Cancer: Four-Arm Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, I.Y.; An, S.Y.; Cha, W.C.; Rha, M.Y.; Kim, S.T.; Chang, D.K.; Hwang, J.H. Efficacy of Mobile Health Care Application and Wearable Device in Improvement of Physical Performance in Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Clin. Color. Cancer 2018, 17, e353–e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, J.M.; Lulla, A.; Williamson, J.D.; Devine, K.A.; Ohman-Strickland, P.; Bandera, E.V. Patterns of Fitbit Use and Activity Levels Among African American Breast Cancer Survivors During an EHealth Weight Loss Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, D.J.; Fay, K.A.; Batsis, J.A.; Stevens, C.J.; Sacks, O.A.; Darabos, C.; Cook, S.B.; Lyons, K.D. A Feasibility Study of an Unsupervised, Pre-operative Exercise Program for Adults with Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, K.; Kloek, C.J.; Aaronson, N.K.; Janssen, K.W.; Jones, L.W.; Sitskoorn, M.M.; Stuiver, M.M. Feasibility of a Home-Based Exercise Intervention with Remote Guidance for Patients with Stable Grade II and III Gliomas: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gell, N.M.; Grover, K.W.; Humble, M.; Sexton, M.; Dittus, K. Efficacy, Feasibility, and Acceptability of a Novel Technology-Based Intervention to Support Physical Activity in Cancer Survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, C.L.; Irving, L.; Antippa, P.; Edbrooke, L.; Parry, S.M.; Krishnasamy, M.; Denehy, L. CAPACITY: A Physical Activity Self-Management Program for Patients Undergoing Surgery for Lung Cancer, a Phase I Feasibility Study. Lung Cancer 2018, 124, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.M.; Richmond, J.; Mc Sharry, J.; Groarke, A.; Harney, O.M.; Kelly, M.G.; Walsh, J.C. Acceptability of a Mobile Health Behavior Change Intervention for Cancer Survivors with Obesity or Overweight: Nested Mixed Methods Study within a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Jiménez-Castuera, R.; Maxwell-Smith, C.; Bulsara, M.K.; Hince, D. Fitbit Wear-Time and Patterns of Activity in Cancer Survivors throughout a Physical Activity Intervention and Follow-up: Exploratory Analysis from a Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.J.; Nelson, S.H.; Weiner, L.S. Patterns of Fitbit Use and Activity Levels Throughout a Physical Activity Intervention: Exploratory Analysis from a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanzawa-Lee, G.A.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.J.; Larson, J.L.; Krauss, J.C.; Resnicow, K.; Lavoie Smith, E.M. Efficacy of the Motivational Interviewing-Walk Intervention for Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy and Quality of Life During Oxaliplatin Treatment: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2022, 45, E531–E544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenfield, S.A.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Ameli, N.; Lavaki, E.; Cedars, B.; Paciorek, A.T.; Monroy, C.; Tantum, L.K.; Newton, R.U.; Signorell, C.; et al. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Behavioral Outcomes from a Technology-Enhanced Behavioral Change Intervention (Prostate 8): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial in Men with Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Seo, J.; An, S.-Y.; Sinn, D.H.; Hwang, J.H. Efficacy and Safety of an MHealth App and Wearable Device in Physical Performance for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Usability Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.A.; Danko, M.; Durica, K.C.; Kunta, A.R.; Mulukutla, R.; Ren, Y.; Bartlett, D.L.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Dey, A.K.; Jakicic, J.M. A Real-Time Mobile Intervention to Reduce Sedentary Behavior Before and After Cancer Surgery: Usability and Feasibility Study. JMIR Perioper Med. 2020, 3, e17292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, B.M.; Nguyen, N.H.; Moore, M.M.; Reeves, M.M.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Boyle, T.; Vallance, J.K.; Milton, S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; English, D.R. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Wearable Technology-based Intervention for Increasing Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity and Reducing Sedentary Behavior in Breast Cancer Survivors: The ACTIVATE Trial. Cancer 2019, 125, 2846–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, B.M.; Nguyen, N.H.; Moore, M.M.; Reeves, M.M.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Boyle, T.; Milton, S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Vallance, J.K.; English, D.R. Maintenance of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Change, and Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Change after an Abridged Intervention: Secondary Outcomes from the ACTIVATE Trial. Cancer 2019, 125, 2856–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthick, M.; Dhillon, H.M.; Alison, J.A.; Cheema, B.S.; Shaw, T. An Interactive Web Portal for Tracking Oncology Patient Physical Activity and Symptoms: Prospective Cohort Study. JMIR Cancer 2018, 4, e11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell-Smith, C.; Hince, D.; Cohen, P.A.; Bulsara, M.K.; Boyle, T.; Platell, C.; Tan, P.; Levitt, M.; Salama, P.; Tan, J.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of WATAAP to Promote Physical Activity in Colorectal and Endometrial Cancer Survivors. Psycho Oncol. 2019, 28, 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Tevaarwerk, A.J.; Sesto, M.; Van Remortel, B.; Date, P.; Gangnon, R.; Thraen-Borowski, K.; Cadmus-Bertram, L. Effect of a Technology-supported Physical Activity Intervention on Health-related Quality of Life, Sleep, and Processes of Behavior Change in Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psycho Oncol. 2020, 29, 1917–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, E.; Xiong, N.; Thompson, E.; Poort, H.; Schumer, S.; Liu, J.F.; Krasner, C.; Campos, S.M.; Horowitz, N.S.; Feltmate, C.; et al. Stepping into Survivorship Pilot Study: Harnessing Mobile Health and Principles of Behavioral Economics to Increase Physical Activity in Ovarian Cancer Survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Spence, R.R.; Sandler, C.X.; Tanner, J.; Hayes, S.C. Feasibility and Effect of a Physical Activity Counselling Session with or without Provision of an Activity Tracker on Maintenance of Physical Activity in Women with Breast Cancer—A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, K.E.; Yoo, J.S.; Chung, S.H.; Lee, J.D.; Lee, I.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, S.K.; Nam, S.J.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Effects of Exercise Intervention in Breast Cancer Patients: Is Mobile Health (MHealth) with Pedometer More Effective than Conventional Program Using Brochure? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Blarigan, E.L.; Chan, H.; Van Loon, K.; Kenfield, S.A.; Chan, J.M.; Mitchell, E.; Zhang, L.; Paciorek, A.; Joseph, G.; Laffan, A.; et al. Self-Monitoring and Reminder Text Messages to Increase Physical Activity in Colorectal Cancer Survivors (Smart Pace): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Boehmke, M.; Wu, Y.-W.B.; Dickerson, S.S.; Fisher, N. Effects of a 6-Week Walking Program on Taiwanese Women Newly Diagnosed with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, E1–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Liao, N.; Han, C.; Liu, W.; Gao, Z. Leveraging Fitness Tracker and Personalized Exercise Prescription to Promote Breast Cancer Survivors’ Health Outcomes: A Feasibility Study. JCM 2020, 9, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; McClean, D.; Ko, E.; Morgan, M.; Schmitz, K. Exercise Among Women with Ovarian Cancer: A Feasibility and Pre-/Post-Test Exploratory Pilot Study. ONF 2017, 44, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.; Spark, L.; Eakin, E. Exercise Behavior, Motivation, and Maintenance Among Cancer Survivors. In Exercise, Energy Balance, and Cancer; Ulrich, C.M., Steindorf, K., Berger, N.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 215–231. ISBN 978-1-4614-4492-3. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Abraham, C.; Whittington, C.; McAteer, J.; Gupta, S. Effective Techniques in Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Interventions: A Meta-Regression. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravata, D.M.; Smith-Spangler, C.; Sundaram, V.; Gienger, A.L.; Lin, N.; Lewis, R.; Stave, C.D.; Olkin, I.; Sirard, J.R. Using Pedometers to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2007, 298, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Lutes, L. Why Do Pedometers Work? A Reflection upon the Factors Related to Successfully Increasing Physical Activity. Sport. Med. 2009, 39, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffart, L.M.; Galvão, D.A.; Brug, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Newton, R.U. Evidence-Based Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Current Guidelines, Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Årsand, E.; Muzny, M.; Bradway, M.; Muzik, J.; Hartvigsen, G. Performance of the First Combined Smartwatch and Smartphone Diabetes Diary Application Study. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, K.; Giangregorio, L.; Schneider, E.; Chilana, P.; Li, M.; Grindrod, K. Acceptance of Commercially Available Wearable Activity Trackers Among Adults Aged Over 50 and with Chronic Illness: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.P.; Loveday, A.; Pearson, N.; Edwardson, C.; Yates, T.; Biddle, S.J.; Esliger, D.W. Devices for Self-Monitoring Sedentary Time or Physical Activity: A Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2016, 18, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauman, J.; Nes, B.M.; Gutvik, C.; Wisløff, U. Personal Activity Intelligence (PAI) for Promotion of Physical Activity and Prevention of CVD. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 815. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, M.; Taylor, E. Pedometer-Based Walking Interventions for Free-Living Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. CDR 2013, 9, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, K.A.; Kirk, A.; Hewitt, A.; MacRury, S. A Systematic and Integrated Review of Mobile-Based Technology to Promote Active Lifestyles in People with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Sun, Z. Step Counter Use in Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiauzzi, E.; Rodarte, C.; DasMahapatra, P. Patient-Centered Activity Monitoring in the Self-Management of Chronic Health Conditions. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Årsand, E.; Frøisland, D.H.; Skrøvseth, S.O.; Chomutare, T.; Tatara, N.; Hartvigsen, G.; Tufano, J.T. Mobile Health Applications to Assist Patients with Diabetes: Lessons Learned and Design Implications. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobelo, F.; Kelli, H.M.; Tejedor, S.C.; Pratt, M.; McConnell, M.V.; Martin, S.S.; Welk, G.J. The Wild Wild West: A Framework to Integrate MHealth Software Applications and Wearables to Support Physical Activity Assessment, Counseling and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 58, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).