Abstract

Regular participation in physical activity is essential for children’s physical, mental, and cognitive health. Neighborhood environments may be especially important for children who are more likely to spend time in the environment proximal to home. This article provides an update of evidence for associations between children’s physical activity behaviors and objectively assessed environmental characteristics derived using geographical information system (GIS)-based approaches. A systematic scoping review yielded 36 relevant articles of varying study quality. Most studies were conducted in the USA. Findings highlight the need for neighborhoods that are well connected, have higher population densities, and have a variety of destinations in the proximal neighborhood to support children’s physical activity behaviors. A shorter distance to school and safe traffic environments were significant factors in supporting children’s active travel behaviors. Areas for improvement in the field include the consideration of neighborhood self-selection bias, including more diverse population groups, ground-truthing GIS databases, utilising data-driven approaches to derive environmental indices, and improving the temporal alignment of GIS datasets with behavioral outcomes.

1. Introduction

Regular participation in physical activity is essential for children’s physical, mental, and cognitive health [1,2]. Strong evidence exists for the link between accumulating an average of 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily with improved health [1]. Children can accumulate MVPA in a variety of ways, including through organized sports, unstructured play, and walking or wheeling to and from places (active travel) [3]. Conversely, an increased time spent sedentary (e.g., recreational screen time, television viewing, car travel) is negatively associated with child health [1]. While some exceptions exist, physical activity, play, and active travel in children are generally low internationally [4,5].

In the last two decades, considerable work has been undertaken to understand factors associated with physical activity using a socio-ecological lens. The early work of Sallis and colleagues [6,7] was especially useful to contextualize how varying social and environmental features might impact physical activity and to highlight areas for improvement. In particular, the role of neighborhood design and “walkability” (e.g., higher levels of street connectivity, mixed land use, retail floor area ratio, and population density in a given area) received increasing focus [8,9]. A now well-established body of research clearly demonstrates associations [10,11,12] and causal relationships [13] between neighborhood features and residents’ physical activity, including for children.

Neighborhood environments may be especially important for children who are more likely than adults to spend time in the environment proximal to home [14,15]. Despite a heterogeneous evidence base, consistent findings have been observed with regard to the importance of walkability (especially street connectivity, population density, and diversity in land use) [16,17], infrastructure for walking and wheeling [18], and the availability and accessibility of destinations to be active (e.g., parks, playgrounds, natural spaces, schools) [16,19] for supporting physical activity. Numerous co-benefits exist when environments are designed to enable children’s physical activity, including supporting planetary health (e.g., through reducing air pollution via shifting from motorized to active travel modes [20,21,22]). Indeed, encouraging active travel has been suggested as a “planetary health intervention” recognizing the multiple pathways through which human travel behaviors and planetary health are linked [23]. Children’s physical activity tracks over the lifespan [24,25], so establishing healthy physical activity habits, including active travel, early in life can have a long-standing impact on both human and planetary health.

Alongside this growing evidence base, an increased sophistication and complexity in the measurement of neighborhood environments has occurred. There is a recognition that the approach used to characterize environments can impact the knowledge generated. For example resident perceptions of environmental features may differ considerably from objective assessments of those features [26]. Consequently, there exists a risk of “masking” relationships, where the body of evidence does not take differing measurement approaches into account. Care must be taken to consider how evidence might differ across research using different environmental measurement approaches.

Geographic information system (GIS) approaches to quantifying and evaluating features within neighborhood and health research have burgeoned. A key strength of GIS in this context is the ability to generate consistent measures, enabling comparability across geographies and population groups. Our recent review explored how GIS had been used to define and describe neighborhood environments in research exploring children’s physical activity and related outcomes [27]. A considerable diversity in both measurement approaches and the reporting of methods was identified; recommendations from the review included the need for greater geographic diversity in the evidence, and an improved consistency and transparency in the reporting, aligning with earlier calls for improving the evidence base [28]. As this previous review was focused on measurement, there was not the opportunity to discuss or reflect on the findings of the studies included. The aim of this short communication is to describe the associations observed in the literature sourced. In doing so, we provide an update to the extant evidence base [10,12,16,29] with a specific focus on the GIS measurement of children’s environments.

2. Methods

The full review protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework on 28 October 2019 (https://osf.io/7wgur/ (accessed on 7 January 2022)) and is also detailed elsewhere [27]. A brief overview is presented here following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist criteria [30].

2.1. Information Sources, Search Terms, and Search Strategy

GEOBASE, Scopus, PubMed (includes MEDLINE), and Social Sciences Citation Index were searched using terms under three categories: Method (e.g., GIS), Population (e.g., child), and Outcome (e.g., built environment). The following is an example of the full electronic search strategy for PubMed: (GIS OR “geographic information system*” OR model*ing OR geospatial OR spatial) AND (child OR child’s OR children OR children’s OR “elementary school*” OR “primary school*” OR “intermediate school*” OR “junior school*” OR “middle school*” OR youth OR “young people”) AND (“activity space*” OR neigh * AND hood OR “built environment” OR “natural environment” OR “home range” OR “home zone” OR territory OR “living environment” OR “residential environment” OR “action space” OR “geographical context” OR “exposure area” OR “urban environment”) AND ((“2006/01/01”[PDat]: “2019/10/29”[PDat]) AND Humans[Mesh] AND English[lang]).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible at the searching stage if they were: (1) peer reviewed articles published in academic journals, (2) published in the English language, (3) conducted with human populations, and (4) published between 1 January 2006 (to align with the emergence of literature using GIS for delineating neighborhoods) and 15 November 2019.

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

After removing duplicate articles, titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved were screened for inclusion. Studies were eligible for inclusion at the screening stage if they used GIS to measure neighborhood environments and included children (defined as aged 5–13 years). Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not include a GIS-based measure of the neighborhood environment, (2) did not include children, or (3) used area-level measures greater than the neighborhood scale (e.g., towns, cities, regions). Duplicate screening was conducted for a random 10% selection of all articles identified at the search stage. Full text articles were then sourced for all “eligible” articles and for those where it was not clear whether they met the inclusion criteria. At the full-text stage, articles were included if they met the criteria above, and additionally: (1) described the methods used to generate the GIS-based measure of neighborhood environments, (2) included a physical activity outcome measure, or focused on the PA-environment relationship, and (3) provided descriptive information about the GIS-based neighborhood environment outcome (in graphical, narrative, or tabular format). Of note, only articles that included a physical activity outcome were included, and those with related measures only (e.g., body mass index) were excluded.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [31,32,33] was used to assess study quality due to its flexibility in assessing varying research designs (e.g., quantitative non-randomized, quantitative descriptive, mixed methods). Evaluation criteria and summary scores were calculated following the MMAT protocol. Quality assessment was duplicated for a random 10% subset of articles.

2.5. Data Charting and Synthesis

Descriptive data of studies included were extracted in duplicate. For the purpose of this examination, key study characteristics, physical activity measurement, and study findings relative to GIS-measured environmental variables were extracted and a narrative description of findings was generated. This study focused on built environments, and thus data on characteristics of the social environment were not extracted unless they were directly related to the GIS findings.

3. Results

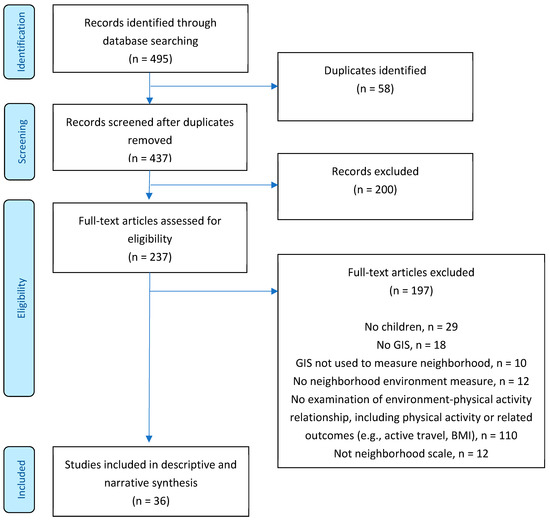

Figure 1 shows the flow chart for the studies included and excluded at each stage of the review process. Table 1 shows the descriptive information for all studies included, key findings, and MMAT scores. The study quality varied, with MMAT scores ranging from 2 to 5 (possible range 1–5). Article quality scores were most commonly reduced due to a lack of clarity or information on study methods and population representativeness.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for articles identified, screened, and included in the review. Note: BMI = body mass index, GIS = geographic information systems.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, key findings, and quality assessment scores.

Overall, findings showed evidence to support relationships between activity behaviors and street connectivity [36,41,42,47,51,56,58,66], with differential relationships observed by age and sex [38,44], and one study showing a negative relationship in females only [34]. Similarly, generally consistent positive relationships between activity and residential density were found [15,41,42,47,50,52,61,66], with the exception of two studies [15,37], one of which examined the proportion of child population in relation to active school travel [15]. Diversity in land use was positively related to physical activity [34,66], and both the density of entertainment facilities [41] and public transit (school-aged girls only) [38] were all positively related with activity behaviors. Walkability was positively associated with activity behaviors in five studies [41,48,55,64,68] (one found a significant positive relationship in low SES areas only [48]), and physical inactivity was associated with walkability in one study [56].

Inconsistent findings were observed for physical activity facilities (including parks, playgrounds, and outdoor spaces). Positive results were found between activity behaviors and physical activity facilities [36,61,65,68], including pay facilities (males only) [35], public open spaces (school-aged females and preschool children only) [38], parks [52,61,66,68], green space [57], and sports fields [59]. However, a number of negative relationships were observed, including for physical activity facilities/sites [45,66] and a higher proportion/area of parks or green space [15,50,56]. Similarly, food outlet density was both positively [50] and negatively [57] associated with activity behaviors.

The density of main streets (exemplifying less safe traffic environments) was negatively related to activity behaviors in one study [37], and another showed positive relationships for traffic safety infrastructure, with differential findings observed for the time of day and population group (i.e., traffic/pedestrian lights were significant in younger girls only, slow points significant for younger boys before school, and speed humps significant in adolescent boys after school [44]).

Walking or cycling track length (including multi-use path space) was associated with activity behaviors (particularly walking or cycling) in four studies [44,45,51,59], while a fifth found a negative association between cycling infrastructure and children’s license for independent mobility [69]. Distance to school was negatively related to active school travel [42,53,62,66].

4. Discussion

The aim of this short communication was to describe the associations observed between GIS-derived environmental features and children’s activity behaviors, drawing from a systematic scope of the literature. In doing so, we have provided an updated review of the extant evidence [10,12,16,29], with a targeted focus on the GIS measurement of children’s environments. Findings align with previous systematic reviews examining environmental associates of children’s physical activity behaviors [10,12,16,29]. While some inconsistencies exist, together this body of literature supports the need for neighborhoods that are well connected, have higher population densities, and have a variety of destinations in the proximal neighborhood to support a range of physical activity behaviors in children. In line with previous reviews [11,70,71], a shorter distance to school and safe traffic environments were significant factors in supporting children’s active travel behaviors. These features are interconnected and speak to the importance of comprehensive urban design approaches that embrace concepts such as walkable neighborhoods [72], livable neighborhoods [73], 15 min cities [74], and 20 min neighborhoods [75]. Across these concepts, having a range of destinations of importance within walkable distances from residential homes is fundamental. Having a sufficient population density to warrant the required transport infrastructure and destination diversity, and to support social cohesion and connection, is also intrinsic to these concepts, meaning that inequities may exist by urbanicity. Increasing attention is also focusing on the importance of low-traffic neighborhoods for increasing physical activity (especially active travel) through increasing safety from traffic and by improving social connection and cohesion [76,77,78]. While this review did not focus on social aspects of supporting children’s PA, social cohesion and connection have been previously identified as important for facilitating children’s physical activity [11,79], so are important co-benefits of these approaches. Ultimately, findings from the current review add evidence to the growing evidence base, demonstrating that connected and comprehensive approaches to urban design are needed to encourage and support children’s physical activity.

Considerable potential also exists for improving planetary health through these environmental approaches [21,22,23]. The transport sector plays a significant role in greenhouse gas emissions [22], and urban design that prioritizes motorized transport can contribute to the urban heat island effect [80]. Shifting the prioritisation of land use away from roads towards connecting communities and providing infrastructure that facilitates active travel is likely to make a meaningful contribution to improving planetary health and achieving the sustainable development goals [81]. Supporting a generation of young children to develop physical activity habits (including active travel) early in life is likely to have a sustained impact on their health and that of their planet [24,25].

A considerable heterogeneity in GIS methods was observed across the studies in this review, and substantial variability in the reporting of GIS methods was found. The GIS database availability and quality limited the body of evidence, with studies purchasing commercial (and potentially incomplete) databases, triangulating a range of data sources to generate measures, and using temporally mismatched datasets to the outcome being measured. Only one study noted “ground truthing” through phone calls and physical visits to food outlet locations [82]. Such ground truthing is particularly important for retail and food outlets, where a higher turnover may occur than changes to the physical activity infrastructure. It is unclear whether ground truthing is as important for physical activity facilities and destinations as it is for food and retail settings. On-the-ground checks for a full GIS dataset are not realistic or feasible (and would negate the need for estimated measures). A more feasible approach is to generate a random subset of the full GIS dataset for ground truthing. However, no recommendations for an optimal proportion for resampling exist. Precedents in child health and environment literature include Huang, Brien [83] physically confirming a random 10% selection of bus stops in a study using Google Street View to measure outdoor advertising around schools, and Vandevijvere, Sushil [84] randomly selecting 1% of 8403 geocoded food outlets and confirming details via telephone; however, the authors are unaware of this occurring with specific regard to physical activity destinations.

Walkability (determined from street connectivity, residential density, land use mix, and sometimes the retail floor area ratio) [85] was the most common index in the literature identified. Other indices were used with varying degrees of rationale for determining and calculating the index. For example, DeWeese et al. [50] used latent class profiling to generate clusters of environmental features associated with BMI, and Ikeda et al. [53] developed a latent variable “active mobility environment”, based on correlations of environmental features in structural equation modeling. Future research in this area is warranted, particularly for different physical activity outcomes, and in different socio-demographic groups.

The reporting of physical activity measurement methods was considerably better than the reporting of GIS measurement in the literature sourced. This may reflect the established state of the field of physical activity research, compared with the relatively recent emergence of research using GIS-derived measures to understand associations between environments and physical activity. Even so, considerable differences in physical activity measurements were observed across studies, further limiting a clear understanding of associations between children’s physical activity and their environments. An increased conceptual matching of the physical activity behavior (e.g., active travel) and environmental features assessed (e.g., active travel infrastructure) is needed to increase the specificity and sensitivity in understanding PA–environment links [86].

A number of other study design strengths and limitations were identified. Numerous studies had representation from ethnically and socio-economically diverse population groups [34,35,36,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,50,53,56,57,60,62,63,64,66,67,68], and some had large and/or representative samples [34,35,36,37,43,47,55,56,58,61,63]; however, evidence was predominantly from the USA [34,35,36,39,40,41,42,43,46,47,50,63,64,68] and there was no literature related to disabled children. Heterogeneity in study environments was encouraged through stratified neighborhood/area sampling in a number of studies. Two studies reported excluding child participants who had recently moved to the neighborhood [54,87], improving the sensitivity and reducing the impact of reactivity on the shifting of physical activity behaviors. Neighborhood self-selection was rarely noted, albeit this may be less important for children than adults, who have more control over where they live. The consideration of children living in more than one home was not noted. A lack of consideration of clustering (e.g., at school level) was a limitation of the body of literature.

5. Conclusions

Despite a heterogeneous evidence base, consistent findings were observed that add weight to existing evidence for the essential role of neighborhood environments in promoting children’s physical activity behaviors. Findings highlight the need for neighborhoods that are well connected, have higher population densities, and have a variety of destinations in the proximal neighborhood to support children’s physical activity behaviors. A shorter distance to school and safe traffic environments were significant factors in supporting children’s active travel behaviors. Areas for improvement in the field include the consideration of neighborhood self-selection bias, including more diverse population groups, ground-truthing GIS databases, utilising data-driven approaches to derive environmental indices, and improving temporal and conceptual alignment of GIS datasets with behavioral outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., S.M., K.H. and M.K.; methodology, M.S., S.M., K.H., E.I., J.Z., N.D., J.C., T.E.R. and M.K.; formal analysis, M.S.; data curation, M.S., E.I. and J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., S.M., K.H., E.I., J.Z., N.D., J.C., T.E.R. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MS is supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Sir Charles Hercus Research Fellowship (grant number 17/013). EI is supported by the Medical Research Council [MC_UU_00006/5]. SM is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (#1121035). KH is supported by Academy of Finland as part of PLANhealth project (13297753). TL is supported by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture as part of FREERIDE project (grant number OKM/30/626/2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tessa Pocock for her contribution to the article quality assessment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, W.B.; Malina, R.M.; Blimkie, C.J.; Daniels, S.R.; Dishman, R.K.; Gutin, B.; Hergenroeder, A.C.; Must, A.; Nixon, P.A.; Pivarnik, J.M.; et al. Evidence Based Physical Activity for School-age Youth. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusseau, T.; Fairclough, S.J.; Lubans, D.R. The Routledge Handbook of Youth Physical Activity, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Cardon, G.; Chang, C.-K.; Nyström, C.D.; Demetriou, Y.; Edwards, L.; Emeljanovas, A.; Gába, A.; et al. Report Card Grades on the Physical Activity of Children and Youth Comparing 30 Very High Human Development Index Countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S298–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Abdeta, C.; Nader, P.A.; Adeniyi, A.F.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Tenesaca, D.S.A.; Bhawra, J.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; Cardon, G.; et al. Global Matrix 3.0 Physical Activity Report Card Grades for Children and Youth: Results and Analysis from 49 Countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S251–S273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F.; Kraft, K.; Linton, L.S. How the environment shapes physical activity: A transdisciplinary research agenda. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Saelens, B.E.; Bachman, W. Many pathways from land use to health—Associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2006, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.; Powell, K.E.; Chapman, J.E. Stepping towards causation: Do built environments or neighborhood and travel preferences explain physical activity, driving, and obesity? Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1898–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.F.; Moreira, C.; Abreu, S.; Mota, J.; Santos, R. Environmental determinants of physical activity in children: A systematic review. Arch. Exerc. Health Dis. 2014, 4, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, E.; Hinckson, E.; Witten, K.; Smith, M. Associations of children’s active school travel with perceptions of the physical environment and characteristics of the social environment: A systematic review. Health Place 2018, 54, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Sallis, J.F.; Kerr, J.; Lee, S.; Rosenberg, D.E. Neighborhood Environment and Physical Activity Among Youth: A Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; Macmillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport—An update and new findings on health equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, J.R.; Mitchell, R.; McCrorie, P.; Ellaway, A. Children’s mobility and environmental exposures in urban landscapes: A cross-sectional study of 10–11 year old Scottish children. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 224, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, A.M.; Broberg, A.K.; Kahila, M.H. Urban Environment and Children’s Active Lifestyle: SoftGIS Revealing Children’s Behavioral Patterns and Meaningful Places. Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, e137–e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.K.; Lawson, C.T. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, P.; Zou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wu, T.; Smith, M.; Xiao, Q. Street connectivity, physical activity, and childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pan, X.; Zhao, L.; Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, T.; Smith, M.; Dai, S.; Jia, P. Access to bike lanes and childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P.; Page, A.S.; Wheeler, B.W.; Cooper, A.R. What can global positioning systems tell us about the contribution of different types of urban greenspace to children’s physical activity? Health Place 2012, 18, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chertok, M.; Voukelatos, A.; Sheppeard, V.; Rissel, C. Comparison of air pollution exposure for five commuting modes in Sydney—Car, train, bus, bicycle and walking. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2004, 15, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reis, R.; Hunter, R.F.; Garcia, L.; Salvo, D. What the physical activity community can do for climate action and planetary health? J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 19, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; Siri, J.G. Toward Urban Planetary Health Solutions to Climate Change and Other Modern Crises. J. Hered. 2021, 98, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toner, A.; Lewis, J.S.; Stanhope, J.; Maric, F. Prescribing active transport as a planetary health intervention—benefits, challenges and recommendations. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2021, 26, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telama, R.; Yang, X.; Viikari, J.; Välimäki, I.; Wanne, O.; Raitakari, O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A 21-year tracking study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, F.; Laurencelle, L.; Shephard, R.J. Tracking of Physical Activity from Childhood to Adulthood. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orstad, S.L.; McDonough, M.H.; Stapleton, S.; Altincekic, C.; Troped, P.J. A Systematic Review of Agreement Between Perceived and Objective Neighborhood Environment Measures and Associations With Physical Activity Outcomes. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 904–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Cui, J.; Ikeda, E.; Mavoa, S.; Hasanzadeh, K.; Zhao, J.; Rinne, T.E.; Donnellan, N.; Kyttä, M. Objective measurement of children’s physical activity geographies: A systematic search and scoping review. Health Place 2020, 67, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Yu, C.; Remais, J.V.; Stein, A.; Liu, Y.; Brownson, R.C.; Lakerveld, J.; Wu, T.; Yang, L.; Smith, M.; et al. Spatial Lifecourse Epidemiology Reporting Standards (ISLE-ReSt) statement. Health Place 2019, 61, 102243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.P.; Harris, K.J.; Paine-Andrews, A.; Fawcett, S.B.; Schmid, T.L.; Lankenau, B.H.; Johnston, J. Measuring the Health Environment for Physical Activity and Nutrition among Youth: A Review of the Literature and Applications for Community Initiatives. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S98–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018; Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, R.Q.; Khanassov, V.; Hong, Q.N.; Bush, P.L.; Vedel, I.; Pluye, P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: Updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone-Heinonen, J.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Life stage and sex specificity in relationships between the built and socioeconomic environments and physical activity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2010, 65, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone-Heinonen, J.; Guilkey, D.K.; Evenson, K.R.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Residential self-selection bias in the estimation of built environment effects on physical activity between adolescence and young adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boone-Heinonen, J.; Popkin, B.M.; Song, Y.; Gordon-Larsen, P. What neighborhood area captures built environment features related to adolescent physical activity? Health Place 2010, 16, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bringolf-Isler, B.; Grize, L.; Mäder, U.; Ruch, N.; Sennhauser, F.H.; Braun-Fahrländer, C. Built environment, parents’ perception, and children’s vigorous outdoor play. Prev. Med. 2010, 50, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Kneib, T.; Tkaczick, T.; Konstabel, K.; Pigeot, I. Assessing opportunities for physical activity in the built environment of children: Interrelation between kernel density and neighborhood scale. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cain, K.L.; Millstein, R.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Gavand, K.A.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Geremia, C.M.; Chapman, J.; Adams, M.A.; et al. Contribution of streetscape audits to explanation of physical activity in four age groups based on the Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS). Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 116, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.A.; Mitchell, T.B.; Saelens, B.E.; Staggs, V.S.; Kerr, J.; Frank, L.D.; Schipperijn, J.; Conway, T.L.; Glanz, K.; Chapman, J.E.; et al. Within-person associations of young adolescents’ physical activity across five primary locations: Is there evidence of cross-location compensation? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, J.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Kerr, J.; Schipperijn, J.; Conway, T.L.; Frank, L.D.; Chapman, J.E.; Glanz, K.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F. Association between neighborhood walkability and GPS-measured walking, bicycling and vehicle time in adolescents. Health Place 2015, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, J.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Kerr, J.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E. Built environment characteristics and parent active transportation are associated with active travel to school in youth age 12–15. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll-Scott, A.; Gilstad-Hayden, K.; Rosenthal, L.; Peters, S.M.; McCaslin, C.; Joyce, R.; Ickovics, J.R. Disentangling neighborhood contextual associations with child body mass index, diet, and physical activity: The role of built, socioeconomic, and social environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carver, A.; Timperio, A.; Hesketh, K.; Crawford, D. Are safety-related features of the road environment associated with smaller declines in physical activity among youth? J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carver, A.; Timperio, A.F.; Crawford, D.A. Bicycles gathering dust rather than raising dust—Prevalence and predictors of cycling among Australian schoolchildren. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughenour, C.; Burns, M.S. Community design impacts on health habits in low-income southern Nevadans. Am. J. Health Behav. 2016, 40, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, M.A.; Longacre, M.R.; Drake, K.M.; Gibson, L.; Adachi-Mejia, A.M.; Swain, K.; Xie, H.; Owens, P.M. Built Environment Predictors of Active Travel to School Among Rural Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Meester, F.; Van Dyck, D.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Cardon, G. Active living neighborhoods: Is neighborhood walkability a key element for Belgian adolescents? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dessing, D.; De Vries, S.I.; Hegeman, G.; Verhagen, E.; Van Mechelen, W.; Pierik, F.H. Children’s route choice during active transportation to school: Difference between shortest and actual route. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeWeese, R.S.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Adams, M.A.; Kurka, J.; Han, S.Y.; Todd, M.; Yedidia, M.J. Patterns of food and physical activity environments related to children’s food and activity behaviors: A latent class analysis. Health Place 2017, 49, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbich, M.; van Emmichoven, M.J.Z.; Dijst, M.J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Pierik, F.H.; de Vries, S.I. Natural and built environmental exposures on children’s active school travel: A Dutch global positioning system-based cross-sectional study. Health Place 2016, 39, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinckson, E.; Cerin, E.; Mavoa, S.; Smith, M.; Badland, H.; Stewart, T.; Duncan, S.; Schofield, G. Associations of the perceived and objective neighborhood environment with physical activity and sedentary time in New Zealand adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikeda, E.; Hinckson, E.; Witten, K.; Smith, M. Assessment of direct and indirect associations between children active school travel and environmental, household and child factors using structural equation modelling. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.Z.; Moore, R.; Cosco, N. Child-friendly, active, healthy neighborhoods: Physical characteristics and children’s time outdoors. Environ. Behav. 2014, 48, 711–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáuregui, A.; Soltero, E.; Santos-Luna, R.; Barrera, L.H.; Barquera, S.; Jauregui, E.; Lévesque, L.; Lopez-Taylor, J.; Ortiz-Hernández, L.; Lee, R. A Multisite Study of Environmental Correlates of Active Commuting to School in Mexican Children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Laxer, R.; Janssen, I. The proportion of youths’ physical inactivity attributable to neighbourhood built environment features. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGrath, L.J.; Hinckson, E.A.; Hopkins, W.G.; Mavoa, S.; Witten, K.; Schofield, G. Associations Between the Neighborhood Environment and Moderate-to-Vigorous Walking in New Zealand Children: Findings from the URBAN Study. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mecredy, G.; Pickett, W.; Janssen, I. Street Connectivity is Negatively Associated with Physical Activity in Canadian Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3333–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Clark, A.F.; Gilliland, J.A. Built Environment Influences of Children’s Physical Activity: Examining Differences by Neighbourhood Size and Sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölenberg, F.J.; Noordzij, J.; Burdorf, A.; van Lenthe, F.J. New physical activity spaces in deprived neighborhoods: Does it change outdoor play and sedentary behavior? A natural experiment. Health Place 2019, 58, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, E.C.A.; Raanaas, R.K.; Nordh, H.; Aamodt, G. Neighborhood green spaces, facilities and population density as predictors of activity participation among 8-year-olds: A cross-sectional GIS study based on the Norwegian mother and child cohort study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliver, M.; Badland, H.; Mavoa, S.; Witten, K.; Kearns, R.; Ellaway, A.; Hinckson, E.; Mackay, L.; Schluter, P.J. Environmental and socio-demographic associates of children’s active transport to school: A cross-sectional investigation from the URBAN Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Gavand, K.A.; Millstein, R.A.; Geremia, C.M.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.; Glanz, K.; King, A.C. Is Your Neighborhood Designed to Support Physical Activity? A Brief Streetscape Audit Tool. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; Carlson, J.A.; Frank, L.D.; Kerr, J.; Glanz, K.; Chapman, J.E.; Saelens, B.E. Neighborhood built environment and socioeconomic status in relation to physical activity, sedentary behavior, and weight status of adolescents. Prev. Med. 2018, 110, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P.; Irwin, J.D.; Gilliland, J.; He, M.; Larsen, K.; Hess, P. Environmental influences on physical activity levels in youth. Health Place 2009, 15, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loon, J.; Frank, L.D.; Nettlefold, L.; Naylor, P.J. Youth physical activity and the neighbourhood environment: Examining correlates and the role of neighbourhood definition. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 104, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.; McCormack, G.R.; Timperio, A.; Middleton, N.; Beesley, B.; Trapp, G. How far do children travel from their homes? Exploring children’s activity spaces in their neighborhood. Health Place 2012, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.; Geremia, C.; Kerr, J.; Glanz, K.; Carlson, J.A.; Sallis, J.F. Interactions of psychosocial factors with built environments in explaining adolescents’ active transportation. Prev. Med. 2017, 100, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Amann, R.; Cavadino, A.; Raphael, D.; Kearns, R.; Mackett, R.; Mackay, L.; Carroll, P.; Forsyth, E.; Mavoa, S.; et al. Children’s Transport Built Environments: A Mixed Methods Study of Associations between Perceived and Objective Measures and Relationships with Parent Licence for Independent Mobility in Auckland, New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikeda, E.; Stewart, T.; Garrett, N.; Egli, V.; Mandic, S.; Hosking, J.; Witten, K.; Hawley, G.; Tautolo, E.-S.; Rodda, J.; et al. Built environment associates of active school travel in New Zealand children and youth: A systematic meta-analysis using individual participant data. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.Y.-M.; Faulkner, G.; Buliung, R. GIS measured environmental correlates of active school transport: A systematic review of 14 studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunn, L.D.; Mavoa, S.; Boulange, C.; Hooper, P.; Kavanagh, A.; Giles-Corti, B. Designing healthy communities: Creating evidence on metrics for built environment features associated with walkable neighbourhood activity centres. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hooper, P.; Foster, S.; Bull, F.; Knuiman, M.; Christian, H.; Timperio, A.; Wood, L.; Trapp, G.; Boruff, B.; Francis, J.; et al. Living liveable? RESIDE’s evaluation of the “Liveable Neighborhoods” planning policy on the health supportive behaviors and wellbeing of residents in Perth, Western Australia. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, R.; Calafiore, A.; Nurse, A. 20-Minute Neighbourhood or 15-Minute City? Town and Country Planning, 16 June 2021. Available online: https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3127722/1/15MN_20MC.doc (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Aldred, R.; Goodman, A. The Impact of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods on Active Travel, Car Use, and Perceptions of Local Environment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Findings 2021, 21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H. The Shared Path; The Helen Clark Foundation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Children’s perceptions of their neighbourhoods during COVID-19 lockdown in Aotearoa New Zealand. Child. Geogr. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.-Y.; Witten, K.; Oliver, M.; Carroll, P.; Asiasiga, L.; Badland, H.; Parker, K. Social and built-environment factors related to children’s independent mobility: The importance of neighbourhood cohesion and connectedness. Health Place 2017, 46, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Climate Change and Cities: Challenges Ahead. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoine, T.; Jones, A.P.; Namenek Brouwer, R.J.; Benjamin Neelon, S.E. Associations between BMI and home, school and route environmental exposures estimated using GPS and GIS: Do we see evidence of selective daily mobility bias in children? Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, D.; Brien, A.; Omari, L.; Culpin, A.; Smith, M.; Egli, V. Bus Stops Near Schools Advertising Junk Food and Sugary Drinks. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Sushil, Z.; Exeter, D.J.; Swinburn, B. Obesogenic Retail Food Environments Around New Zealand Schools: A National Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, e57–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Leary, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Hess, P.M. The development of a walkability index: Application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, G.; Pikora, T.; Learnihan, V.; Bulsara, M.; Van Niel, K.; Timperio, A.; McCormack, G.; Villanueva, K. School site and the potential to walk to school: The impact of street connectivity and traffic exposure in school neighbourhoods. Health Place 2011, 17, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M.R.; Eizenberg, E.; Plaut, P. Getting to Know a Place: Built Environment Walkability and Children’s Spatial Representation of Their Home-School (h–s) Route. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).