Abstract

Although the beneficial effects of nuts on cardiometabolic diseases have been well established, little is known about the effects of nuts on age-related diseases. Given that age-related diseases share many biological pathways with cardiometabolic diseases, it is plausible that diets rich in nuts might be beneficial in ameliorating age-related conditions. The objective of this review was to summarise the findings from studies that have examined the associations or effects of nut consumption, either alone or as part of the dietary pattern, on three major age-related factors—telomere length, sarcopenia, and cognitive function—in older adults. Overall, the currently available evidence suggests that nut consumption, particularly when consumed as part of a healthy diet or over a prolonged period, is associated with positive outcomes such as longer telomere length, reduced risk of sarcopenia, and better cognition in older adults. Future studies that are interventional, long-term, and adequately powered are required to draw definitive conclusions on the effects of nut consumption on age-related diseases, in order to inform dietary recommendations to incorporate nuts into the habitual diet of older adults.

Keywords:

nuts; older adults; ageing; quality of life; telomere; sarcopenia; cognition; diet quality 1. Introduction

Human life expectancy has increased globally, and the increment rate has been more rapid in industrialised countries [1]. Greater life expectancy can be largely attributed to medical advancements, which significantly reduces mortality rates [2]. Due to increased longevity, healthy ageing and better quality of life are becoming more important among older adults [3]. The quality of life of older adults is multidimensional and depends on: (a) individual factors, e.g., satisfaction with one own’s physical/mental health, functional capacity (autonomy), emotional comfort, spirituality, and financial security; and (b) environmental factors, e.g., social interaction, network, and support [4].

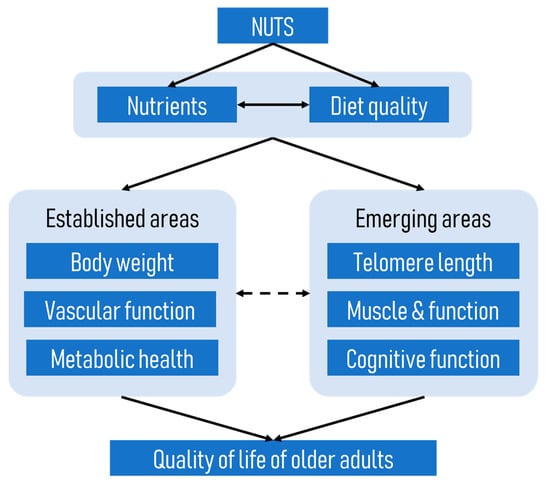

The focus of this review is on how nut intake either consumed alone or as part of the dietary pattern can improve the quality of life of older adults. We propose that nuts may improve the quality of life of older adults through the promotion of better health, cognitive function, and functional capacity in this population, as depicted in a conceptual framework below (Figure 1). This framework is based on the premise that nuts, which are high in essential nutrients, improve diet quality and the overall nutritional status of older adults (see previous review [5]). As outlined in this framework, better nutrition and diet quality will, in turn, improve the health, wellbeing, and the quality of life of older adults.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of how nuts improve the quality of life of older adults.

A number of previous reviews have highlighted the benefits of nuts on body weight regulation [6,7], improved vascular function, and prevention of cancer [8] and metabolic diseases such as cardiovascular disease [9,10] and type 2 diabetes mellitus [10,11], which are prevalent among older individuals; therefore, these aspects will not be addressed again in this review. Instead, we will explore other emerging areas such as the potential effects of nuts on telomere length, muscle and function, and cognitive function of older adults. These aspects are of importance because telomere length has been shown to be an important indicator of ageing [12], while optimal physical and cognitive function will allow older adults to live independently as long as possible. It is also important to note that the emerging areas discussed in this review are not independent of the well-established areas shown in Figure 1. For example, telomere length has been linked to the onset of several age-related diseases [13], and vascular function has been shown to influence cognitive function [14].

In this narrative review, we summarise the findings from studies that have investigated the associations or effects of nut consumption on telomere length, muscle and function, and cognitive function of older adults. These are emerging areas in nut research; therefore, we have included studies that have examined the influence of nuts alone, or nuts as part of an overall dietary pattern such as the Mediterranean diet. In the latter, it is often difficult to attribute the observations to nuts or the nuts/seeds/legumes food group within the dietary patterns specifically, unless these studies conducted separate analysis on each of the components within the dietary patterns. Hence, the results from studies that focused primarily on dietary patterns only should not be over-interpreted. Furthermore, although different nuts are high in certain nutrients, all nuts share very similar overall nutritional profiles, i.e., high in unsaturated fats, fibre, and nutrients that are essential for good health [5]. For this reason, all nut types are considered comparable nutritionally, and dietary recommendations focus on all nuts instead of specific nut types. Therefore, this review will not compare different nut types, but rather consider them collectively. Finally, studies cited in this review were not limited to those that included older adults (>60 years) only, but they were included nonetheless because optimal nutrition in younger adults is arguably very important in the prevention of health conditions that occur in old age.

2. Nut Consumption and Telomere Length

Regular nut consumption is associated with a reduced risk of chronic diseases [15,16], including biomarkers of these age-related diseases [10,17,18]. The effects of nut consumption on telomere length have gained attention as one possible mechanism whereby nuts may reduce age-related diseases [19]. Telomeres are caps which protect the ends of chromosomes, and their lengths are an indicator of biological age. They protect DNA from oxidative damage, allowing the cell to divide normally. The length of telomeres is carefully controlled by a variety of proteins, including the enzyme telomerase, which promotes telomere length and stability [20]. Telomere length is shortened with each cell division, with a loss of around 50–200 bases [21]. Eventually, the telomere will reach a length that is associated with cell apoptosis [22]. Shortening of telomeres is negatively associated with cell longevity, and has been associated with disorders such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes [23,24].

Although increasing age is strongly correlated with shorter telomere length, the variability in the rate of telomere shortening—independent of chronological age—suggests that other factors are important. Several modifiable lifestyle factors have been implicated in the rate of telomere shortening. For example, telomere length has been positively associated with greater fruit and vegetable intakes, and higher levels of physical activity; and negatively associated with higher saturated fat and meat consumption intakes, adiposity, and smoking [25,26,27,28,29,30]. The following sections review the evidence for the association of nut consumption and telomere length to determine whether this may partly explain the reduction in age-related diseases observed with regular nut intake.

There are several potential mechanisms whereby nuts may exert a positive effect on telomere length and cellular senescence. A number of nutrients have been implicated as having an important role in DNA methylation and integrity due to their antioxidant properties [31]. These nutrients include isoflavanoids, folate, vitamin E, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Although nuts differ in a number of individual nutrients, they are all rich sources of antioxidant nutrients and unsaturated fatty acids. For example, peanuts and hazelnuts are particularly good sources of folate, whereas walnuts, Brazil nuts, and pine nuts are good sources of PUFA. It has been suggested that telomere length is a marker of oxidative stress [32]. Previous studies have shown that regular nut consumption is associated with reductions in some, but not all, markers of oxidative stress and inflammation [33,34]. In addition, Cannudas et al. [35] showed reduced oxidative damage of DNA with the consumption of pistachio nuts over four months.

To examine the association between nut consumption and telomere length, we reviewed one prospective study and two intervention studies that specifically examined the independent effect of nut consumption on telomere length. We also reviewed fifteen cross-sectional analyses, two prospective analyses, and two intervention studies that included or emphasised nuts as part of a dietary pattern.

2.1. Evidence from Observational Studies

2.1.1. Nut-Specific Studies

One study from a large nationally representative sample examined the association between nut consumption and telomere length [19]. Tucker et al., using 24 h recall data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002 (n = 5582), found a positive association between the consumption of nuts and seeds and telomere length. The association was linear (after adjustment), with each 1% of total energy derived from nuts and seeds associated with a length which was 4.5 base pairs longer. To give some perspective to these results, the authors calculated that using an estimated age-related rate of shortening of telomeres of 15.4 base pairs per year, adults of the same age who consumed 5% of total energy from nuts and seeds had around one- to two-thirds less cell ageing compared to non-consumers.

2.1.2. Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts

Observational studies that have examined the association between telomere length and diet quality or dietary patterns that include or emphasise nut consumption have been performed in a range of different ethnic groups and countries, including Korea [27], China [36,37], Spain [38,39], Hong Kong [40], Italy [41], the United States [25,42,43,44], Iran [45], Australia [46], and Finland [47]. Of the fifteen observational studies, thirteen used a cross-sectional design [25,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], one study [27] used a prospective design, and one study included both a cross-sectional and prospective analysis [47]. Details of these studies can be found in Table 1. Although the dietary indices used in these studies do not allow us to identify the independent effects of nuts, nuts were a food group which comprised the healthy component of these indices.

Table 1.

Nut consumption and telomeres.

Nine studies examined adherence to pre-determined diet quality indices which emphasised nut intake. These included the Mediterranean diet score, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) score, Health Eating Index 2010 score (HEI-2010), Alternative Health Eating Index 2010 score (AHEI-2010), and the Prime Diet Quality Score (PDQS).

Studies Using a Mediterranean Diet Quality Score

The dietary pattern which has received the most attention in this area is the Mediterranean diet, which has been correlated with healthy ageing and longevity [48]. One of the key components of the Mediterranean dietary pattern is nut consumption. In addition, this pattern is characterised as being largely plant-based with high amounts of olive oil, fruits and vegetables, legumes, and wholegrains [49]. When study populations were analysed as a whole, three studies showed a positive association between the Mediterranean diet and telomere length [25,39,41], while two showed no association [44,46]. Two studies showed positive associations in women only [38,43], and one U.S. study showed a positive association among white, but not African American or Hispanic participants [42]. Meinilä et al. found no association in a cross-sectional analysis of their Finnish population, but found slight, although statistically significantly, higher rates of telomere shortening among women adhering to a Mediterranean dietary pattern in the 10-year follow-up prospective analysis. Interestingly, this was largely driven by the fruit and nut food group; however, this difference was small and not considered clinically important [47].

Two studies that showed a positive association with the Mediterranean dietary pattern also analysed nuts as a food group, but found no association between nuts and telomere length [25,38]. Trichopoulou et al. have previously suggested that components of the Mediterranean eating pattern may be additive; hence, the lack of association based on a single nut food group. Additionally, looking at individual foods may be more susceptible to residual confounding [50]. Therefore, the potential benefit of nuts on telomere length is likely to be mediated through better overall diet quality. Of note is the finding that studies on the Mediterranean eating pattern carried out in southern European countries tended to show positive associations with telomere length compared to those carried out in countries such as Australia [46], Finland [47], and the United States [44]. This may indicate higher overall adherence to such an eating pattern in southern Europe, which may be more likely to show positive associations.

A meta-analysis including eight of the aforementioned cross-sectional studies collectively assessed the association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and telomere length maintenance [51]. In the fully adjusted model for all participants, there was a positive association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and telomere length maintenance, but this association disappeared when males and females were separated. This may be due to reduced power, but of note, no significant associations were seen in any of the models for men.

Studies Using Other Diet Quality Scores

Two of the aforementioned studies that investigated the Mediterranean diet also examined other nut-containing dietary patterns [39,43]. Ojeda-Rodriquez showed that, similar to their findings of the Mediterranean diet, greater adherence to the Prime Diet Quality Score (PDQS), the Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score (AHEI-2010), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) scores was associated with longer telomere length among the Seguimiento Univeridad de Navarra (SUN) cohort [39]. In contrast, Leung et al., using data from the 1999–2002 cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examinations Survey (NHANES), showed significant trends for longer telomere lengths from the lowest to the highest quintiles for each diet score (the Healthy Eating Index 2010 score (HEI-2010), the Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score (AHEI-2010), or the DASH diet score) among women, but not men. This reflects their findings in terms of adherence to the Mediterranean diet [43].

Posteriori Dietary Patterns

Three studies (two cross-sectional and one prospective) analysed FFQ data and derived dietary patterns using principal component analysis (PCA) or factor analysis [27,36,52]. One study conducted in South China found that a dietary pattern containing nuts was associated with longer telomeres among women, but not men [36]. In a prospective study conducted in South Korea, a prudent diet was positively associated with telomere length [27]. When analysing individual food items which contributed to the prudent dietary pattern, nuts were positively associated with telomere length.

One U.S. study, including data from 840 Black, White, and Hispanic adults taking part in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), used PCA and reported no association between consuming a nut-containing food pattern and telomere length [52]. They also failed to show an association when nut or seeds were considered alone.

Studies on Food Group Including Nuts

A further three studies used FFQs to examine the association of nuts and seeds consumed as a food group and telomere length. One study conducted in China showed that intakes of nuts or seeds were highest among those in the upper tertile for telomere length, and intakes were positively associated with telomere length [37]. In contrast, Chan et al., reported no associations between nut consumption and telomere length in a cross-sectional study of 2006 Chinese males and females living in Hong Kong [40]. Here, nuts were combined with the food group of legumes, seeds and nuts. A further study among males in Iran showed that nuts and seed were negatively, albeit not statistically significantly, associated with telomere length [45]. It should be noted that participants in this study were younger (25–40 years) compared to most other studies in this area.

2.1.3. Summary of Studies on Dietary Quality and Patterns

Collectively, these observational studies on dietary patterns containing nuts have produced mixed results, making it difficult to form conclusions. Of the fifteen studies, nine showed a positive association between the consumption of a nut-containing dietary pattern and telomere length in the population as a whole or in a sub-group, five showed no association, and one showed a negative association, albeit not clinically important. Some factors which make interpretation of these observational studies difficult include the inability to examine the independent effects of nuts, variation in the age of participants, and the use of different dietary assessment tools. There also appears to be some sex differences, with three studies showing positive associations with consumption of nut-containing dietary patterns and telomere length in females only [36,38,43]. The reason for these sex-specific associations cannot be speculated based on the observational nature of these studies, and future clinical trials are therefore needed to understand the potential underlying biological explanations. A further factor to consider when interpreting the results of observational studies is survivor bias. This is where people who live longer tend to be more resilient to chronic disease. Although these studies cannot infer causality, they do provide useful information on which to base hypotheses that can be explored in intervention studies.

2.2. Evidence from Interventional Studies

2.2.1. Nut-Specific Studies

To the best of our knowledge, only two intervention studies have specifically assessed the effects of nut consumption on telomere length [35,53]. Freiras-Simoes et al. examined the inclusion of 15% of dietary energy from walnuts (n = 80), compared to a control group (n = 69), who continued to consume their usual diet while abstaining from walnuts, on the maintenance of telomere length in a group aged 63–79 years [53]. This parallel study was conducted over two years. There was a significant increase in red blood cell alpha-linolenic acid in the walnut group compared to the control, indicating compliance to the interventions. There was a tendency (p = 0.079) for the control group to have greater reduction in telomere length over the two years compared to the walnut group. In addition, the change in the percentage of telomeres with lengths less than 3 kb at the end of two years was marginally statistically significantly lower in the walnut group. Taken together, these results suggest that consuming walnuts may reduce telomere attrition.

Canudas et al. investigated the effect of pistachio consumption on telomere length and gene expression related to telomere maintenance in 49 participants aged 25–65 years with pre-diabetes using a crossover design [35]. Participants consumed a diet supplemented with 57 g/d pistachios compared with an isocaloric control diet for four months each. Telomere length did not differ between the two treatments; however, genes associated with telomere length were significantly upregulated in the pistachio treatment compared with the control.

While the findings of these intervention studies are promising, they need to be confirmed in long-term, adequately powered, randomised intervention studies using different types and doses of nuts.

2.2.2. Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts

There are only two intervention studies which have assessed telomere length in response to interventions with dietary patterns that emphasise nut consumption.

Garcia-Calzón et al. performed several analyses on the association between telomere length and diet using a subgroup from the PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial involving 520 participants aged 55–80 years who were at high risk of CVD [38]. In this trial, participants were randomly assigned to one of two Mediterranean diets supplemented with either extra virgin olive oil or mixed nuts, or to a low-fat control diet. Intervention with the Mediterranean diets with nuts was associated with a higher risk of telomere shortening compared to the control, whereas, there were no differences between the Mediterranean diet with extra virgin olive oil and the control group [38]. When analysing the individual components of the Mediterranean diet including nuts and extra virgin olive oil, there was no association between these components and telomere length. This is in agreement with other observational studies [25,42]. The sample size may not have had sufficient power to identify small changes in telomere length by individual dietary components. The finding that the intervention with the Mediterranean diet with nuts had a detrimental effect on telomere length was unexpected; although, it should also be noted that the control group increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet over the intervention, which made the results difficult to interpret. The authors also suggest that lifetime exposure to a Mediterranean diet may be more meaningful in determining telomere length than exposure during a five-year intervention. Further analysis of this group showed that among those with the Pro12Ala polymorphism—a gene variant associated with lower CVD risk—greater adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern was associated with greater prevention of telomere shortening [54].

In a small crossover study, 20 participants aged over 65 years consumed three diets for four weeks each: a Mediterranean diet enriched in olive oil; a saturated fat-rich diet; and a low fat, high carbohydrate diet enriched in n-3 PUFA from walnuts [28]. The Mediterranean diet was associated with a lower percentage of telomere shortening compared to the other two interventions. It was proposed that the Mediterranean diet protected against oxidative stress, and thus prevented telomere shortening. A Mediterranean diet usually contains nuts; however, it is unclear to what extent nuts were included in the Mediterranean arm of this study.

2.3. Summary

Overall, research on the effects of nut consumption and telomere length is inconsistent. Some observational studies show greater telomere length among those consuming dietary patterns including nuts, while others do not. Many of these studies failed to show an association with nuts consumption per se. Several systematic reviews have shown that intensive lifestyle interventions delay telomere shortening [29]. Therefore, more comprehensive changes may be more effective than changing only one component of the diet, such as increasing nut consumption. This suggests that the synergistic effect of nutrients may be important. It is possible that nuts, as part of a healthy diet and lifestyle, may be one contributing factor telomere health, and may be one of the underlying mechanisms whereby regular nut consumption reduces the risk of age-related diseases. However, it is important to note that much evidence derives from observational studies, and hence the relationship between nut intake and telomere length is largely associative rather than causal. How telomere length translates into lifespan is not straightforward, so it is also not possible to propose that nut intake contributes to longevity in older adults.

3. Nut Consumption and Sarcopenia and Related Factors

According to the revised European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), sarcopenia is characterised by low levels of muscle strength and muscle quantity or quality, and severe sarcopenia is characterised by sarcopenia and low physical performance [55].

Ageing is associated with the loss of muscle mass and strength, although the rate of decline differs between individuals, suggesting that lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity may be important determinants of muscle health [56,57]. Current evidence suggests that nutrients such as protein, beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, vitamin D, antioxidant nutrients, and long-chain PUFAs, as well as physical activity, may ameliorate the risk of sarcopenia [57,58,59], through muscle protein synthesis or preventing muscle breakdown, which helps to preserve muscle mass and function. Nuts are rich sources of plant protein, unsaturated fatty acids, phytochemicals, vitamins and minerals; therefore, these nutrients may act synergistically for the prevention and management of sarcopenia in older adults.

This section will review observational studies that examined the association between nut consumption, either alone (Section 3.1.1) or as part of a dietary pattern (Section 3.1.2), and sarcopenia and related factors in older adults. A total of seven observational studies have been identified (Table 2) [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. To the best of our knowledge, no intervention studies have been specifically designed to determine the effect of nut consumption on sarcopenia.

Table 2.

Studies on nuts and sarcopenia related factors.

3.1. Evidence from Observational Studies

Seven observational studies have been identified in the nuts and sarcopenia area (Table 2) [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. One prospective study examined the association between nut consumption and physical function [60], three observational studies (one prospective study and two cross-sectional studies) reported nuts as a food group [62,63,65], and another three studies (one prospective study and two cross-sectional studies) examined the adherence to diet quality indices in which nuts was a key component [61,64,66]. Two studies were conducted in Spain, and one each in the United States, China, Korea, Denmark, and Iran (Table 2).

3.1.1. Nut-Specific Studies

To date, only one prospective study has examined the association between nut consumption and physical function [60]. The Seniors-ENRICA cohort study was conducted in Spain in 3289 community-dwelling older adults aged ≥60 years [60]. A validated diet history was used to assess consumption of 20 types of nuts in this study. Physical function was ascertained by five domains, namely agility, mobility, overall physical function, grip strength, and gait speed, with the first three domains being self-reported and the last two domains being objective measures.

Participants were classified into three categories based on their nut consumption: non-consumers, <median (<11.5 g/d), and ≥median (≥11.5 g/d). In men, there was a dose-response relationship between nut consumption and impaired agility (p for trend = 0.01) and mobility (p for trend = 0.02), in which higher nut consumption was associated with lower risk of these two impairments. Compared with non-consumers, nut intake of ≥11.5 g/d was associated with a lower risk of impaired agility (HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.39, 0.90) and impaired mobility (HR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.90) in the fully adjusted models. In women, there was a dose-response relationship between nut consumption and impaired overall physical function (p for trend = 0.004). Compared with non-consumers, nut intake ≥11.5 g/d was associated with lower risk of impaired overall physical function (HR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.87). However, nut consumption was not associated with grip strength and gait speed. The authors reported that this could be due to the low sensitivity of method used to detect the differences.

Overall, this study revealed that nut consumption was associated with a lower risk of self-reported impaired agility and mobility in men, and lower risk of impaired overall physical function in women [60]. However, such associations were not observed in objective measures of grip strength and gait speed. Further investigation is warranted to confirm this finding.

3.1.2. Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts

Six observational studies have examined the association between dietary patterns that include nuts and sarcopenia. Three studies reported nuts as a food group [62,63,65], while the other three studies reported the adherence to diet quality indices in which nuts was a key component [61,64,66].

Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts (as a Food Group)

Three studies, consisting of one prospective study and two cross-sectional studies, examined nuts as part of a dietary pattern and their relationship with muscle mass and function [62] and sarcopenia [63,65]. The Framingham Offspring study was the first prospective study to investigate the association between a diet rich in protein-source foods (including nuts) and skeletal muscle mass and functional status among community-dwelling adults [62]. Results showed that compared to consumption <0.25 servings/day of “legumes, soy, nuts, seeds”, those who consumed ≥1.25 servings/day had a higher mean percent skeletal muscle mass in men (difference of 0.7%, p = 0.0197) and women (difference of 0.8%, p = 0.0156), although the difference in percent skeletal muscle mass was small.

Two cross-sectional studies in China and Korea examined the association between food groups (in which nuts was one of the food groups) and sarcopenia in older adults [63,65]. Hai et al. [63] reported that female participants with sarcopenia had a significantly lower frequency of nut consumption compared to those without sarcopenia (0.05 times per week vs. 0.81 times per week, p = 0.022). In addition, there was a 28% reduction in the prevalence of sarcopenia and frequency of nut consumption (OR = 0.724, 95% CI: 0.532, 0.985). In line with these findings, a cross-sectional study showed that male participants with sarcopenia had a significantly lower intake of nuts and seeds compared to those without sarcopenia (3.1 g per day vs. 5.2 g per day, p = 0.002) [65].

Overall, the evidence from observational studies where nuts were included as a food group showed an inverse association between nut consumption and sarcopenia [63,65]. In addition, a prospective study reported higher skeletal muscle mass among people who consumed more servings/day of “legumes, soy, nuts, seeds” [62]. The current, albeit limited, epidemiologic evidence suggests a protective effect of nut consumption on sarcopenia in older adults.

Studies Using Diet Quality Indices

Three studies, including one prospective study and two cross-sectional studies, examined adherence to diet quality indices, such as the Mediterranean diet and Mobility diet, and the risk of sarcopenia and related factors [61,64,66]. The Seniors-ENRICA prospective study reported a dose-response relationship between the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) score and risk of falling (p for trend = 0.04) [61]. Participants in the highest tertile of the MEDAS score had a 28% reduction in the risk of falling, in comparison with those in the lowest tertile of the MEDAS score. Similarly, Hashemi et al. [64] reported an inverse dose-response relationship between the Mediterranean pattern and sarcopenia (p for trend = 0.04). Participants in the highest tertile of the Mediterranean pattern had a 60% reduction in the odds of having sarcopenia, compared to those in the lowest tertile of the Mediterranean pattern. There was a significant association between a Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence of low gait speed (p = 0.02). The percentage of participants with low gait speed (<0.8 m/s) was lowest in the top tertile of the Mediterranean dietary pattern. In line with these findings, another cross-sectional study reported that dietary index characterised by higher intakes of whole grains, dairy products, fish, legumes, nuts, fruit, and vegetables was associated with faster 400 m walking speed (p for trend = 0.021) [66].

Overall, the evidence showed an association between dietary patterns with nuts and a lower risk of falling, sarcopenia, and low gait speed. Nuts were one of the many components in these diet quality indices, which makes it difficult to estimate the independent effect of nuts. It is likely that the combined effect of several food components within a diet will exert greater protective benefits than the individual effect of a single food. Nevertheless, these results are promising and warrant further investigation.

3.2. Summary

There is limited published research investigating the association between nut consumption and sarcopenia and its components. Results from the prospective studies and cross-sectional studies reported positive associations between nut consumption and physical function. It is important to note that no study to date has reported a detrimental effect on muscle function after nut consumption. Further research is required to draw definitive conclusions of the association between nut consumption and sarcopenia.

4. Nut Consumption and Cognitive Function

The potential benefits of nuts on cognitive function have been proposed in a previous review, which included three observational studies and one interventional trial [14]. The authors summarised that nut consumption appears to be associated with better cognition, hypothesising that this relationship may be explained by improved endothelial function, which subsequently improves cerebral blood flow and the delivery of nutrients with anti-inflammatory properties to the brain. The studies included in the review by Barbour and colleagues did not focus on older adults specifically [67,68], but also included young [69] and middle-aged adults [70]. Therefore, for the purpose of this paper, we conducted a literature review of studies that were published since the previous review, which explicitly focused on older adults. In total, we identified 18 studies (12 observational and 6 interventional studies) that reported on nut consumption and cognitive function of older adults (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Observational studies examining the association between nut consumption and cognition.

Table 4.

Interventional studies examining the effects of nut consumption on cognition.

4.1. Evidence from Observational Studies

4.1.1. Nut-Specific Studies

Six studies (three cross-sectional and three prospective) investigated the relationship between cognitive function of older adults with nut intake specifically (Table 3). Only one study did not find significant differences in the cognitive battery test scores between older adults who have low vs. high nut intake after adjusting for multiple covariates [67]. The remaining five studies reported significant and positive associations between various measures of cognitive function and nut consumption of older adults [68,71,72,73,74]. Specifically, higher nut consumption was related to better overall cognition [72,73], working memory [68,73], and immediate recall [73]. In prospective observational studies, nut consumption was also associated with a lower probability (OR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.61–0.99) of cognitive decline over three years [74], and participants were 40% less likely to have poor cognitive function [72]. However, the association between nut consumption and slower cognitive decline was not observed in another study that only included women aged 70 years and over [73].

4.1.2. Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts

Six studies (three cross-sectional and three prospective) also investigated the associations between dietary patterns that included nuts and cognitive function of older adults. In these studies, nuts were either a stand-alone component of a dietary pattern [75,76,77,78], or as part of a bigger food group such as the “nuts and legumes” [79] or “pulses, nuts and seeds” food groups [80]. Therefore, it is important to note that it was not always possible to attribute the findings of these studies to the intake of nuts specifically. Again, only one study (with approximately a nine-year follow-up period) did not find significant associations between nut consumption and global cognition or verbal memory of over 6000 older women [77]. In the remaining five studies, three cross-sectional studies reported a lower risk of cognitive impairment with a higher intake of nuts [75,76,80], and two prospective studies in over 4000 older adults reported better overall cognition [78,79] and verbal memory [78].

To summarise evidence from observational studies, there was a consistent association between nut consumption and better cognitive function test scores, regardless of whether nut intake was investigated specifically, or when considered as part of an overall dietary pattern. For example, the adherence to healthy dietary patterns that included nuts (e.g., the Mediterranean or DASH diet) was associated with better cognitive function [75,79,80]. However, observational studies showed association, not causation. Participants’ health condition and long-term dietary habits prior to these studies may influence the study findings, and should also be considered.

4.2. Evidence from Interventional Studies

4.2.1. Nut-Specific Studies

Three interventional studies that investigated the effects of nut supplementation on the cognitive function of older adults were identified (Table 4). Two more recent studies that had larger study sample sizes supplemented the intervention diets with almonds [81] or walnuts [82] as 15% of participants’ daily energy intake. Despite the larger dose and sample sizes, these studies did not identify significant differences in cognitive performance or mood after the intervention periods [81,82]. On the other hand, a pilot study that supplemented the diet with one Brazil nut (~5 g) per day for 6 months reported improvements in two (verbal fluency and constructional praxis) of the six subsets of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) neuropsychological tests battery [83]. The reason for the contradicting findings from these interventional studies is unclear; the authors of the Brazil nut study attributed the findings to the antioxidative activities of selenium and glutathione peroxidase enzyme in the Brazil nut. It is also possible that the pilot study included participants with mild cognitive impairment, while the other two studies included healthy older adults; hence, they were more likely to detect a difference between the intervention and control groups.

4.2.2. Studies on Dietary Patterns That Include Nuts

Besides the nut-specific studies, three studies also incorporated nuts as part of an overall Mediterranean diet intervention [84,85,86]. These studies included large sample sizes and were conducted over a longer period of time, ranging from 6 months to 6.5 years. Consuming 30 g/day of mixed nuts as part of a Mediterranean diet was shown to improve memory composite scores (p = 0.04) but not frontal and global cognition when compared to a low-fat control diet [86]. Two other studies that also used a similar Mediterranean dietary pattern intervention approach also reported better cognitive function test scores after the interventions [84,85]. However, the differences between the intervention and the control group disappeared after the findings were adjusted for multiple factors including incident depression.

4.3. Summary

Most epidemiological studies (of both cross-sectional and prospective study designs) appear to show positive associations between nut consumption and the cognitive function of older adults. These epidemiological studies were conducted in countries from different regions (Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America). Not surprisingly, almost all observational studies had larger study populations than the interventional studies.

Although one study reported a sex-specific association between nut intake and cognitive function (better in men) [80], other observational studies included in this review that recruited both sexes did not support this observation. In fact, two out of three observational studies that included only females in their studies [73,78] reported positive associations between nut intake and better cognitive scores. Therefore, based on the overall observations, the relationship between nuts and better cognitive performance is likely to be generalisable to all older men and women globally. However, more future studies are still needed to either confirm or rule out the sex-specific associations between nuts and cognition of older adults.

It should be noted that while positive associations between nut consumption and cognitive function in older adults were found in cross-sectional and prospective (with long follow-up) observational studies, almost all interventional studies failed to demonstrate the benefits of nut supplementation (alone or as part of an overall dietary pattern intervention) on cognitive function measurements. The inconsistent findings between studies of different designs suggest that the benefits of nuts on cognition may potentially require very long-term habitual nut consumption. Hence, the effects of nuts were not detected in interventional studies that were generally shorter in study intervention periods. Relatively smaller sample populations in the interventional studies may be another reason why statistically significant effects of nuts on cognitive function of older adults were not detected. The relatively small associations reported by observational studies with large sample sizes suggest that large interventional studies may be required in the future. Regardless, it is important to consider the clinically meaningful effect size too, so that emphasis is not placed on statistical power alone.

In the interventional studies that used an overall dietary pattern approach, nut consumption was only one component of the overall interventions, making it difficult to assess the independent effects of nuts, especially if the study sample populations were small due to the high burden of an interventional study design. In addition, almost all interventional studies included healthy community-dwelling older adults, which may have reduced the likelihood to detect further improvements in cognitive function within a short period of intervention. This speculation is supported by a pilot study that included older adults who had mild cognitive impairment, where significant improvement in cognitive function was found after a very low dose of nut supplementation for six months [83].

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Overall, there are some preliminary data suggesting that nut consumption may be associated with longer telomere length, lower risk of sarcopenia, and better cognition in older adults. The associations appear to be more consistent when nuts were considered as part of the overall diets of older adults, suggesting a synergistic effect between nuts and other food groups. However, the evidence to-date is largely based on observational studies, and the findings were not always consistent. Future research is warranted to confirm these associations. This includes observational studies that are longer-term and adequately powered, because changes to function and cognition occur over time. Well-designed, long-term clinical studies are also needed to confirm the causal relationships between nuts and these health aspects of older adults, and whether the effects from nuts are clinically meaningful. Future research will be needed to form and guide the development of specific nut recommendation for older adults’ health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B.; methodology, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B.; validation, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B.; investigation, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B.; writing—review and editing, S.-Y.T., S.L.T. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roser, M.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Ritchie, H. Life Expectancy. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Cassel, C.K. Successful aging. How increased life expectancy and medical advances are changing geriatric care. Geriatrics 2001, 56, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson, M.; Johansson, P.-O. Quality of life and the WTP for an increased life expectancy at an advanced age. J. Public Econ. 1997, 65, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.M.R.; Navarrro, J.M.R. The Impact of Quality of Life on the Health of Older People from a Multidimensional Perspective. J. Aging Res. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.-Y.; Tey, S.L.; Brown, R. Can Nuts Mitigate Malnutrition in Older Adults? A Conceptual Framework. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhlaghi, M.; Ghobadi, S.; Zare, M.; Foshati, S. Effect of nuts on energy intake, hunger, and fullness, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Dhillon, J.; Mattes, R.D. A review of the effects of nuts on appetite, food intake, metabolism, and body weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 412S–422S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshi, S.; Sadeghian, M.; Nasiri, M.; Mobarak, S.; Asadi, M.; Sadeghi, O. Association of Total Nut, Tree Nut, Peanut, and Peanut Butter Consumption with Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.M.; Hill, A.M.; Tan, S.Y. Nuts and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2018, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Does Nut Consumption Reduce Mortality and/or Risk of Cardiometabolic Disease? An Updated Review Based on Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindall, A.M.; Johnston, E.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Petersen, K.S. The effect of nuts on markers of glycemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.L.; Newman, A.B. Telomere Length in Epidemiology: A Biomarker of Aging, Age-Related Disease, Both, or Neither? Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco, M.A. Telomeres and human disease: Ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J.A.; Howe, P.R.C.; Buckley, J.D.; Bryan, J.; Coates, A.M. Nut consumption for vascular health and cognitive function. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2014, 27, 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Yang, J.; Marventano, S.; Micek, A.; Galvano, F.; Kales, S.N. Nut consumption on all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, A.J.; De Souza, R.J.; Meyre, D.; Anand, S.S.; Mente, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nut consumption and incident risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Falk, M.C.; Feldman, R.; Lewis, K.; Mozaffarian, D. Effects of tree nuts on blood lipids, apolipoproteins, and blood pressure: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and dose-response of 61 controlled intervention trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaté, J.; Oda, K.; Ros, E. Nut Consumption and Blood Lipid Levels. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.A. Consumption of nuts and seeds and telomere length in 5,582 men and women of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Paolisso, G.; Mecocci, P. Nutrition and lifestyle in healthy aging: The telomerase challenge. Aging 2016, 8, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J.; Kim, S.-H.; Lim, C.-S.; Rubio, M. Cellular senescence, cancer and aging: The telomere connection. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomeres and telomerase in normal and cancer stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 3819–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, M.J.; Ross, S.A.; Briel, M.; Anand, S.S.; Gerstein, H.; Paré, G. Association Between Shortened Leukocyte Telomere Length and Cardiometabolic Outcomes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2015, 8, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzensen, I.M.; Mirabello, L.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Savage, S.A. The Association of Telomere Length and Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous-Bou, M.; Fung, T.T.; Prescott, J.; Julin, B.; Du, M.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.M.; Hu, F.B.; De Vivo, I. Mediterranean diet and telomere length in Nurses’ Health Study: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2014, 349, g6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, S.; Canudas, S.; Muralidharan, J.; García-Gavilán, J.; Bulló, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Impact of Nutrition on Telomere Health: Systematic Review of Observational Cohort Studies and Randomized Clinical Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 11, 576–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Jun, N.-R.; Yoon, D.; Shin, C.; Baik, I. Association between dietary patterns in the remote past and telomere length. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Ramirez, R.; Carracedo, J.; Caballero, J.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Garcia-Rios, A.; Delgado-Casado, N.; Cruz-Teno, C.; et al. Mediterranean diet reduces senescence-associated stress in endothelial cells. AGE 2011, 34, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X. The Impact of Health Promotion Interventions on Telomere Length: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Andrew, T.; Gardner, J.P.; Kimura, M.; Oelsner, E.; Cherkas, L.F.; Aviv, A.; Spector, T.D. Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet 2005, 366, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Simedrea, R.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Mocan, A.; Vlase, L.; Popa, D.-S.; Ferreira, I.C. Benefits of tree nut consumption on aging and age-related diseases: Mechanisms of actions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, J.M.; Moonen, H.J.; Van Schooten, F.J.; Hageman, G.J. Telomere length assessment: Biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Uriarte, P.; Bulló, M.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Babio, N.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Nuts and oxidation: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, E.P.; Tapsell, L.C.; Guan, V.; Batterham, M.J. The effect of nut consumption on markers of inflammation and endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canudas, S.; Hernández-Alonso, P.; Galié, S.; Muralidharan, J.; Morell-Azanza, L.; Zalba, G.; García-Gavilán, J.; Martí, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M. Pistachio consumption modulates DNA oxidation and genes related to telomere maintenance: A crossover randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Tian, G.; Xue, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, G. Higher adherence to the ‘vegetable-rich’ dietary pattern is related to longer telomere length in women. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Zhu, L.; Cui, X.; Feng, L.; Zhao, X.; He, S.; Ping, F.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Influence of diet on leukocyte telomere length, markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in individuals with varied glucose tolerance: A Chinese population study. Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Calzón, S.; Zalba, G.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Martínez, J.A.; Fitó, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; A Martínez-González, M.; Marti, A. Dietary inflammatory index and telomere length in subjects with a high cardiovascular disease risk from the PREDIMED-NAVARRA study: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses over 5 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Rodríguez, A.; Zazpe, I.; Alonso-Pedrero, L.; Zalba, G.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Marti, A. Association between diet quality indexes and the risk of short telomeres in an elderly population of the SUN project. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Woo, J.; Suen, E.; Leung, J.; Tang, N. Chinese tea consumption is associated with longer telomere length in elderly Chinese men. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 103, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Esposito, A.; Rizzo, M.R.; Marfella, R.; Barbieri, M.; Paolisso, G. Mediterranean Diet, Telomere Maintenance and Health Status among Elderly. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Honig, L.S.; Schupf, N.; Lee, J.H.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Stern, Y.; Scarmeas, N. Mediterranean diet and leukocyte telomere length in a multi-ethnic elderly population. AGE 2015, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Fung, T.T.; McEvoy, C.T.; Lin, J.; Epel, E.S. Diet Quality Indices and Leukocyte Telomere Length Among Healthy US Adults: Data From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 2192–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, M.V.; Drazba, M.A.; Holásková, I.; Belden, W.J. Nutrition Risk is Associated with Leukocyte Telomere Length in Middle-Aged Men and Women with at Least One Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Nabizadeh, R.; Yunesian, M.; Mehdipour, P.; Rastkari, N.; Aghaie, A. Foods, Dietary Patterns and Occupational Class and Leukocyte Telomere Length in the Male Population. Am. J. Men’s Health 2017, 12, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, C.M.; Russell, A.P.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Salmon, J.; McNaughton, S.A. Diet quality and telomere length in older Australian men and women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 57, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinilä, J.; Perälä, M.-M.; Kautiainen, H.; Männistö, S.; Kanerva, N.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Iozzo, P.; Guzzardi, M.A.; Eriksson, J.G. Healthy diets and telomere length and attrition during a 10-year follow-up. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haveman-Nies, A.; De Groot, L.C.; Van Staveren, W.A. Dietary quality, lifestyle factors and healthy ageing in Europe: The SENECA study. Age Ageing 2003, 32, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Anatomy of health effects of Mediterranean diet: Greek EPIC prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009, 338, b2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canudas, S.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Hernández-Alonso, P.; Galié, S.; Leung, C.; Crous-Bou, M.; De Vivo, I.; Gao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Meinilä, J.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Telomere Length: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettleton, J.A.; Schulze, M.B.; Jiang, R.; Jenny, N.S.; Burke, G.L.; Jacobs, D.R. A priori–defined dietary patterns and markers of cardiovascular disease risk in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas-Simoes, T.-M.; Cofán, M.; Blasco, M.A.; Soberón, N.; Foronda, M.; Serra-Mir, M.; Roth, I.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Doménech, M.; Ponferrada-Ariza, E.; et al. Walnut Consumption for Two Years and Leukocyte Telomere Attrition in Mediterranean Elders: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Calzón, S.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Razquin, C.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Zalba, G.; Marti, A. Pro12Ala Polymorphism of the PPARγ2 Gene Interacts with a Mediterranean Diet to Prevent Telomere Shortening in the PREDIMED-NAVARRA Randomized Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2015, 8, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019, 393, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Reginster, J.; Rizzoli, R.; Shaw, S.; Kanis, J.; Bautmans, I.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Bruyère, O.; Cesari, M.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; et al. Does nutrition play a role in the prevention and management of sarcopenia? Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Tung, H.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Chen, L.-K. Physical Activity and Sarcopenia in the Geriatric Population: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J. Nutritional interventions in sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Fernández, L.; Machado-Fragua, M.D.; Graciani, A.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Lana, A.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Prospective Association Between Nut Consumption and Physical Function in Older Men and Women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 74, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, J.-M.; Struijk, E.A.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Mediterranean diet and risk of falling in community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradlee, M.L.; Mustafa, J.; Singer, M.R.; Moore, L.L. High-Protein Foods and Physical Activity Protect Against Age-Related Muscle Loss and Functional Decline. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, L.; Liu, P.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Dong, B. Association between sarcopenia with lifestyle and family function among community-dwelling Chinese aged 60 years and older. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, R.; Motlagh, A.D.; Heshmat, R.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Payab, M.; Yousefinia, M.; Siassi, F.; Pasalar, P.; Baygi, F. Diet and its relationship to sarcopenia in community dwelling Iranian elderly: A cross sectional study. Nutrients 2015, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-S. Association of Dietary Variety Status and Sarcopenia in Korean Elderly. J. Bone Metab. 2020, 27, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, S.R.; Lind, M.V.; Mertz, K.H.; Bülow, J.; Bechshøft, R.; Højfeldt, G.; Schucany, A.; Hjulmand, M.; Sidoli, C.; Andersen, S.B.; et al. Development of a Mobility Diet Score (MDS) and Associations with Bone Mineral Density and Muscle Function in Older Adults. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, E.; Refsum, H.; Drevon, C.A.; Tell, G.S.; Nygaard, H.A.; Engedal, K.; Smith, A.D. Cognitive performance among the elderly in relation to the intake of plant foods. The Hordaland Health Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1190–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Pedret, C.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Medina-Remón, A.; Quintana, M.; Corella, D.; Pintó, X.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E. Polyphenol-Rich Foods in the Mediterranean Diet are Associated with Better Cognitive Function in Elderly Subjects at High Cardiovascular Risk. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 29, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribis, P.; Bailey, R.N.; Russell, A.A.; Kilsby, M.A.; Hernandez, M.; Craig, W.J.; Grajales, T.; Shavlik, D.J.; Sabaté, J. Effects of walnut consumption on cognitive performance in young adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 107, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooyens, A.C.J.; Bueno-De-Mesquita, H.B.; Van Boxtel, M.P.J.; Van Gelder, B.M.; Verhagen, H.; Verschuren, W.M.M. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive decline in middle-aged men and women: The Doetinchem Cohort Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, L.; Ang, A. A cross sectional study of the association between walnut consumption and cognitive function among adult us populations represented in NHANES. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 19, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, Z. A Prospective Association of Nut Consumption with Cognitive Function in Chinese Adults Aged 55+ _ China Health and Nutrition Survey. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Okereke, O.; Devore, E.; Rosner, B.; Breteler, M.; Grodstein, F. Long-term intake of nuts in relation to cognitive function in older women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabassa, M.; Zamora-Ros, R.; Palau-Rodriguez, M.; Tulipani, S.; Miñarro, A.; Bandinelli, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Cherubini, A.; Andres-Lacueva, C. Habitual Nut Exposure, Assessed by Dietary and Multiple Urinary Metabolomic Markers, and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: The InCHIANTI Study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, e1900532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Amicis, R.; Leone, A.; Foppiani, A.; Osio, D.; Lewandowski, L.; Giustizieri, V.; Cornelio, P.; Cornelio, F.; Imperatori, S.F.; Cappa, S.F.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Cognitive Status in Free-Living Elderly: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Xiao, R.; Cai, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Pan, L.; Yuan, L. Diet, lifestyle and cognitive function in old Chinese adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 63, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samieri, C.; Grodstein, F.; Rosner, B.A.; Kang, J.H.; Cook, N.R.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Okereke, O.I. Mediterranean Diet and Cognitive Function in Older Age. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samieri, C.; Okereke, O.I.; Devore, E.E.; Grodstein, F. Long-Term Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Overall Cognitive Status, but Not Cognitive Decline, in Women. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengreen, H.; Munger, R.G.; Cutler, A.; Quach, A.; Bowles, A.; Corcoran, C.; Tschanz, J.T.; Norton, M.C.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.A. Prospective study of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension– and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: The Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiardanis, K.; Diamantaras, A.-A.; Dessypris, N.; Michelakos, T.; Anastasiou, A.; Katsiardani, K.-P.; Kanavidis, P.; Papadopoulos, F.C.; Stefanadis, C.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; et al. Cognitive Impairment and Dietary Habits Among Elders: The Velestino Study. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, A.M.; Morgillo, S.; Yandell, C.; Scholey, A.; Buckley, J.D.; Dyer, K.A.; Hill, A.M. Effect of a 12-Week Almond-Enriched Diet on Biomarkers of Cognitive Performance, Mood, and Cardiometabolic Health in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala-Vila, A.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Rajaram, S.; Coll-Padrós, N.; Cofán, M.; Serra-Mir, M.; Pérez-Heras, A.M.; Roth, I.; Freitas-Simoes, T.M.; Doménech, M.; et al. Effect of a 2-year diet intervention with walnuts on cognitive decline. The Walnuts And Healthy Aging (WAHA) study: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.R.; Apolinário, D.; Bandeira, V.D.S.; Busse, A.L.; Magaldi, R.M.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Cozzolino, S.M.F. Effects of Brazil nut consumption on selenium status and cognitive performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 55, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Bryan, J.; Wilson, C.; Hodgson, J.M.; Davis, C.R.; Murphy, K.J. The Mediterranean Diet and Cognitive Function among Healthy Older Adults in a 6-Month Randomised Controlled Trial: The MedLey Study. Nutrients 2016, 8, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Clavero, P.; Toledo, E.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Julián, B.S.; Sanchez-Tainta, A.; Ros, E.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M. Á Mediterranean diet improves cognition: The PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomised trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013, 84, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Pedret, C.; Sala-Vila, A.; Serra-Mir, M.; Corella, D.; De La Torre, R.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Fitó, M.; Pérez-Heras, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Age-Related Cognitive Decline. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).