Abstract

Informal caregivers have a leading role when implementing health care services for people with cognitive disorders living at home. This study aims to examine the current evidence for interventions with dual satisfaction with health care services for people with cognitive disorders and their caregivers. Original papers with quantitative and mixed method designs were extracted from two databases, covering years 2009–2018. Thirty-five original papers reported on satisfaction with health care services. The International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) was used to classify the interventions. Most interventions had a home-based approach (80%). Reduction in caregiver depression was the outcome measure with the highest level of satisfaction. Interventions to reduce depression or increase cognitive performance in persons with cognitive disorders gave the least satisfaction. Satisfaction of both caregivers and persons with cognitive disorders increased their use of services. In the ICHI, nearly 50% of the interventions were classified as activities and participation. A limited number of interventions have a positive effect on satisfaction of both the persons with cognitive disorders and the caregiver. It is important to focus on interventions that will benefit both simultaneously. More research is needed with a clear definition of satisfaction and the use of the ICHI guidelines.

1. Introduction

Mild cognitive disorders or impairments are characterized by a modest cognitive decline not fully interfering with independence in everyday life. However, additional effort and compensatory strategies on the part of the individual is required to perform activities of daily living (ADL’s) []. Major cognitive disorders, such as dementia, are characterized by a significant cognitive decline interfering with independence in ADL’s. Thus, over time, people with cognitive disorders (e.g., mild and major) increasingly need support and care in order to lead a good daily life at home. Informal caregivers are significantly important in this context and thus formal support is essential to reduce unmet needs and enhance satisfaction in this group of people [].

Dissatisfaction with health care intervention may range from a desire to be listened to, to a desire for better communication in order to make the follow up processes more effective [], while satisfaction with such an intervention may prevent early institutionalization and reduce health care costs for society []. Previous studies [,,,] have focused on expectations and experiences of people living with cognitive disorders and their caregivers at outpatient medical consultations, specifically reasons for expressed or unvoiced satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the interaction with the physician. A randomized controlled trial, involving 26 informal caregivers aimed at investigating the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on psychological and physiological responses to stressful situations in caregiving. The results suggested a positive effect of the intervention on the general health of the caregivers, also resulting in better care []. A qualitative study involving data from the National Caregiver survey of 1269 United States (US) veterans with a dementia disease and their primary caregivers suggests that low caregiver satisfaction may indicate an impending breakdown in care recipients’ access to healthcare []. Another study on expectations, experiences, and tensions in a memory clinic involving in-depth post encounter interviews among 11 patients and 17 informal caregivers, found that patient expectations were opposing those of the caregivers []. Similarly, a qualitative study showed that people with mild cognitive impairments and their informal caregivers indicated differences in experiences of health care services, with the caregivers generally reporting more negative impressions of contact than the care recipients themselves [].

To the best of our knowledge on current upgraded systematic reviews, none has so far focused on the satisfaction as an outcome of health care interventions among community living people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers. Since community-based health care interventions are based on local resources within municipalities, they tend to vary, both in form and service delivery. A common variant is support with ADL’s, prescription and implementation of assistive devices, blood pressure monitoring, offers to attend day care centers and other psychosocial intervention. More knowledge on the existing variance of interventions and user satisfaction can support health care professionals in identifying interventions that may enhance satisfaction among people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers. Furthermore, the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) [] may also support the identification and categorization of such interventions. ICHI is a derivative of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, ICF [] and is being developed to provide a common tool for reporting and analyzing health interventions, mostly for research purposes but it can also be useful for guiding interventions in practice. ICHI covers all parts of the health system and contains a wide range of new material not found in national classifications. It defines intervention as an act performed for, with or on behalf of a person or a population with the purpose to assess, improve, maintain, promote or modify health, functioning or health conditions within four sections []:

- Interventions on Body Systems and Functions;

- Interventions on Activities and Participation Domains;

- Interventions on the Environment;

- Interventions on Health-Related Behaviors.

Providing interventions that result in dual satisfaction among people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers is a challenge. Thus, there is an increasing need for practical ways to improve satisfaction with health care interventions provided to community living people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers. Most of all, it is not known which interventions are perceived satisfactory and which are not.

Consequently, the aim of this study was to examine current research evidence on satisfaction with health care interventions among community living people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers. The following research questions guided this review:

- What is the current evidence on satisfaction as an outcome of different health care interventions among community living people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers?

- Which health care interventions are related to satisfaction among community living people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers?

2. Materials and Methods

A detailed search in collaboration with an expert librarian was conducted using two databases, PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), covering the years January 2009 to November 2018. The PICO [] (P = participants, I = intervention, C = comparison, and O = outcome) format was used to develop and limit the search strategy as follows: P = community living people with cognitive disorders living at home and their informal caregivers (spouse, friends, family, close friend, siblings, partner or proxy); I = studies which evaluated satisfaction with health care interventions (psychosocial and physiological) among people with cognitive disorders and their informal caregivers; and C = not applicable; and O = outcomes in terms of satisfaction of the person with cognitive impairment or cognitive disease and the informal caregiver (e.g., acceptance, anxiety, attitudes, behavior, behavioral problems, burden, care and social support, caregiving role, confidence, cognitive performance, depression, experiences, feelings of belonging, frustration, functioning and dependency, memory, mood, perceived usefulness, quality of life or stress). Inclusion criteria were quantitative and mixed method studies written in the English language. Exclusion criteria were peer-reviewed primary studies that focused on the physical and medical effects of interventions without an outcome related to satisfaction and interventions among people living in nursing homes. Furthermore, study protocols, cross-sectional studies or studies that did not focus on intervention but rather on comparison of variables were excluded, as were commentaries, reviews, editorials, case studies, and papers with a qualitative design. In November 2018, a last search was made, this time limiting one of the search blocks to “Dementia” [MeSH] OR “Cognition Disorders [MeSH].

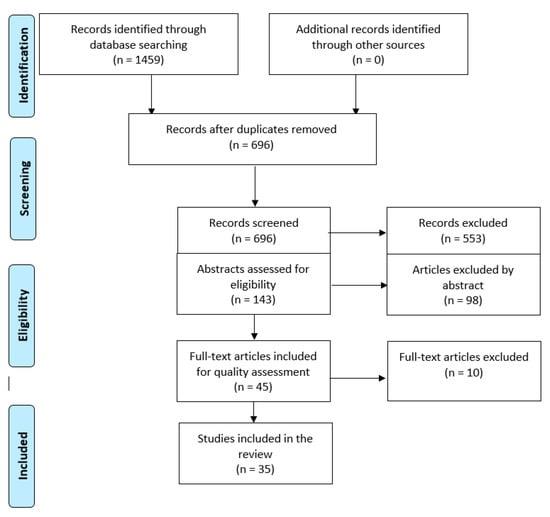

The search resulted in 224 articles from Pub Med and 492 articles in CINAHL (Figure 1). A total of 716 articles were transferred to EndNote manager and 21 were duplicates. Initially, AMF and MA independently screened the remaining 695 papers. Potentially eligible abstracts, (144) were retained and reviewed. Out of them, 98 did not reflect the aim of this review or the inclusion criteria and were thus excluded, resulting in 45 potential full-text papers. The full texts of the retained articles were then analyzed by all authors, who read them whilst strictly keeping the research questions in mind. In turn, the results were crossed checked by MA, CL and AMF until agreement was reached. In total, 35 papers were included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the article selection process using the PRISMA flow diagram [].

Data Synthesis and Quality Assessment

The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), revised version [], was used to rate the quality of the included papers. MMAT applies to different quality criteria for different study designs, taking the unique characteristics of each design into consideration. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize data on the study design, context, participants, type of intervention, methods of data collection, and outcomes of interest in terms of satisfaction and quality of the included papers. Papers meeting 100% of the criteria were rated as top quality (5 stars *****); meeting 80% of the expected criteria were rated with four stars (****); meeting 60% of the criteria were rated with three stars (***); papers meeting 40 % of the criteria were rated with two stars (**); and finally papers meeting 20% of the criteria were rated with one star (*). AMF, CL and MA evaluated each paper separately and then compared the results. Disagreements between the authors (n = 9 papers) were discussed until consensus was reached. Lastly, interventions were categorized according to the ICHI [].

Table 1.

Description of study details, design and quality assessment.

Table 2.

Satisfaction with the interventions provided.

3. Results

The 35 papers included a total of 3501 participants (Table 1), both caregivers and care recipients with a cognitive disorder. The papers described studies carried out in Asia [,,], Europe [,,,,,,,,], North America [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] and Australia [,,]. In 28 studies, data were collected in the homes of the participants using a face-to-face or in-person approach, telephone sessions or both. Data were also collected in counselling rooms, online in one study or by a group approach. The group approach was used when activities such as aerobic exercise, meditation and meetings involved the use of machines and thus needed more space. In 17 studies, a randomized controlled design was applied, eleven studies used a quantitative non-randomized design, six a quantitative descriptive design and one paper described a mixed methods design study. For quality assessment, three papers were rated with one star (*); eight papers with two stars (**); twelve papers with three stars (***); nine papers with four stars (****); and three papers were of top quality (*****). See Table 1 for details.

Fifteen of the interventions in the included papers addressed only the caregiver. Nine interventions addressed persons with a cognitive disorder living alone, while 11 included caregiver and care recipient dyads. In over two thirds of the studies (24/35) the caregivers rated their satisfaction higher than before the interventions. In 10 of the 35 studies the caregivers experienced less depression [,,,,,,,,,], and seven studies reported that the caregivers were more satisfied with caregiver burden [,,,,,,] than before the intervention. Six studies found reduction in caregiver anxiety or stress [,,,,,]. A reduction in caregiver burden was associated with lower levels of anxiety or depression in four studies [,,,].

Social support and use of formal services [,,,,,], better self-rated health [,], quality of life [,,], satisfaction with caregiver role [,], regular meetings [], satisfaction with the intervention [] and increased confidence in managing difficult behavior of the care recipient [] also resulted in increased satisfaction among caregivers.

The care recipients were satisfied with cognitive training [], reduced behavioral problems [], were less depressed and thus satisfied after home delivered psychosocial interventions [,,,] and counselling on communication []. Caregiver and care recipient satisfaction with and after the intervention were sometimes inconclusive. More caregivers than care recipients (2/3 vs. 1/3) were for example satisfied with the use of electronic tracking devices []. There were also different levels of satisfaction when the care recipient perceived that more attention was given to the caregiver []. Another study showed that while the intervention was reported beneficial for care recipient’s memory and ADL and reduced caregiver burden, the caregivers’ and care recipients’ mood did, however, not improve []. A reduction in caregiver depression was only related to less behavioral problems of care recipient []. Only one study found corresponding levels of satisfaction for both care recipient and caregiver, i.e., that caregiver’s experienced more independence and felt overall supported at the end of the intervention [], which prompted continued use of services. Another two studies found that the interventions had positive effects for both the caregiver and the care recipient but to different extent [,]. In more than half of the studies, the presence of the caregivers during the interventions was necessary [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]. See Table 2 for details.

All interventions were classified according to ICHI (Table 2). Four interventions targeted body systems functions [,,,], 16 interventions targeted activities and participation [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], and 11 studies targeted interventions in the environment [,,,,,,,,,]. Four studies included interventions in more than one ICHI section [,,,]. In 16 of the studies [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], the interventions focused on learning new skills, applying knowledge, and self-care. These areas correspond to the domain of activities and participation according to the ICF []. Interventions contributing most towards satisfaction were those that were home-based [,,,,,,,,,], targeting activities and participation.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that interventions aimed at the population under study vary in terms of design, origin and outcomes targeted. Most of the interventions resulted in an enhanced satisfaction among both caregivers and care recipients. However, the results of the interventions in terms of satisfaction differed extensively between caregivers and care recipients, revealing the sometimes-complicated relationships that exist between them.

From a general perspective, key issues related to research in dementia are related to the difficulty to recruit people with dementia into studies. The tendency is thus to ignore the perspectives of people with dementia [], instead the biomedical aspects of neuropathology and aspects of social interactions and contexts are put into focus [,,,]. In our study, most of the results focused the psychosocial aspect of care for people with dementia and their informal caregivers. One of our main findings is that the perspectives, worries and concerns of caregivers may affect the benefits and outcomes of interventions in the home, given that they are of capital importance in the care plan, even when they were not the target of intervention. It is, therefore, important to clearly distinguish between satisfaction of the caregiver and that of the care recipient when planning interventions, and to focus on interventions that will benefit both simultaneously. Since interventions in the home are becoming more common, also for people with cognitive disorders, the design of future studies can benefit from our findings. According to the study by Giese and Cote [], consumer satisfaction is either an emotional or cognitive response to the product or experience of services. Satisfaction is a phenomenon coexisting with other consumption emotions and caregivers are of capital influence in the use of services offered to care recipients. For example, caregivers that are skeptical to support and services may hinder care recipients from fully using the services []. It is, therefore, relevant to gain caregiver confidence and participation []. Our findings are in line with Lopez et al. [], which in their research on the effect of caregiver support interventions found that caregivers were important resources for community-dwelling frail elderly and need to be well supported.

Interestingly, home-based psychoeducational interventions that naturally targeted activities and participation as categorized by the ICHI [] appeared to give greatest satisfaction to both caregiver and care recipient. Therefore, group support interventions should address both caregivers and care recipients while at the same time take into consideration the fact that their needs differ. An earlier study [] showed for example that although caregivers found day care beneficial for their care recipients’ activity and participation, as well as for themselves, care recipients with behavioral problems and those who needed assistance with dressing and toileting are prone to discontinue day care, sometimes after only a few months’ attendance. More recently, Saks et al. [] concluded that suitable community services may divert nursing home entry for certain individuals. Lethin et al. [] also addressed the different context of care in exploring home care vs. nursing home care in rural vs urban settings. The study found that care recipients in home care have more behavioral problems than those in a nursing home. It also revealed that caregivers in urban areas report higher burden compared to those living in rural areas. The positive findings regarding the benefits of interventions focusing on caregivers are in line with the study by Lethin et al. [] showing that caregivers that were satisfied with social services also experienced increased well-being over time. It is further supported that diminished caregiver well-being as well as their negative perception of quality of care predict increased burden []. These findings stress the need for an explicit focus on home-based interventions that benefit caregivers and care recipients.

Strengths and Limitations

Although satisfaction is an important outcome of health care interventions, it is not so common in medical research []. This may be due to the complexity of the concept [] and its measurability. In this context, it was not surprising that most studies included in our review applied no clear definition of satisfaction. Most importantly, in order to enhance outcome evaluation as well as comparison across studies satisfaction as a concept needs to be clearly defined by researchers before and after interventions are made.

This paper attempted to extract satisfaction with health care interventions as the main outcome measure. In an attempt to classify the interventions, the ICHI (9) was used. This classification is still under development but highly recommended by the WHO [] as it may support global initiatives, such as the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage to provide information for patient safety and health system performance []. In this respect, this systematic review adds to current research by providing an example of how the ICHI can be applied.

A weakness of our study is the fact that our search strategy did not capture papers including studies conducted in Africa and South America; generalization of the results beyond the regions included is therefore difficult to make. Lepore et al. [], in their systematic review also mentioned this limitation, highlighting the fact that people of African origin and other ethnic minority groups are under-represented in this kind of research. Moreover, the health care systems in different regions differ considerably in many aspects. Thus, our findings should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, since our study excluded people living in nursing homes, future studies should include the experiences of those people and their informal caregivers.

5. Conclusions

In summary, health care and social service interventions may have an adequate effect on the satisfaction of the caregiver and care recipient living at home. Most importantly, interventions that bring satisfaction to both parties may be beneficial in that it leads to continued use of health care and social services provided. Home-based psychoeducational interventions, targeting activities and participation, appears to result in the greatest satisfaction for both care recipient and caregiver. We thus can conclude that group support interventions should address both caregivers and care recipients, and to consider the fact that their needs differ. It is, therefore, important to distinguish between satisfaction of the care recipient and the caregiver when planning interventions, and to focus on interventions that will benefit both simultaneously. For research and practice purposes, the ICHI would harmonize the coding of interventions around the globe, in turn of added advantage to future intervention, planning and evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.F., B.T., M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; methodology, M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; validation, A.M.F., M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; formal analysis, M.A.Y.-N.; writing—original draft, A.F.M., M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, A.M.F., B.T., M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; visualization, M.A.Y.-N. and C.L.; supervision, A.M.F. and C.L.; project administration, A.M.F., B.T. and C.L.; funding acquisition, B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden; and the Faculty of Health Sciences, OsloMet–Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted within the context of the Centre for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE) at Lund University. The authors would like to acknowledge Linda Grandsjö at the Library & ICT Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, for support in the development of search strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5VR); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.; Go, Y.; Lee, D.Y. The roles of unmet needs and formal support in the caregiving satisfaction and caregiving burden of family caregivers for persons with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli-Miller, O.; Werner, P.; Neufeld-Kroszynski, G.; Eidelman, S. Are you talking to me?! An exploration of the triadic physician–patient-companion communication within memory clinic encounters. Patient Educ. Counc. 2012, 88, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, B.P. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical and Economic Benefits. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulafia-Brakha, T.; Suchecki, D.; Gouveia-Paulino, F.; Nitrini, R.; Ptak, R. Cognitive-behavioural group therapy improves psychophysiological marker of stress in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.M.; van Houtven, C.H.; Sleath, B.L. Barriers to outpatient care in community-dwellling elderly with dementia: The role of caregiver life satisfaction. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2009, 28, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli-Miller, O.; Werner, P.; Aharon-Peretz, J.; Sinoff, G.; Eidelman, S. Expectations, experiences and tensions in the memory clinic: The process of diagnosis disclosure of dementia within a triad. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1756–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.; Jenkinson, C.; Wilcock, G.; Walker, Z. Exploring the experiences of people with mild cognitive impairment and their caregivers with particular reference to healthcare—A qualitative study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICHI The New Interventions Classification for Every Health System. In International Classification of Health Interventions; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://mitel.dimi.uniud.it/ichi/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Boudin, F.; Nie, J.Y.; Bartlett, J.C.; Grad, R.; Pluye, P.; Dawes, M. Combining classifiers for robust PICO element detection. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2010, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inform. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Webb, S.; Bartsch, L.; Rebok, G.; Cherbuin, N.; Anstey, K.J. Tailored and adaptive computerized cognitive training in older adults at risk for dementia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 60, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, F.; Grocke, D.; Pachana, N. Connecting through music: A study of a spousal caregiver—Directed music intervention designed to prolong fulfilling relationships in couples where one person has dementia. AJMT 2012, 23, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Braddock, B.; Phipps, E. The effects of student home visits on activity engagement in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Am. J. Recreat. Ther. 2011, 10, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Lau, B.H.; Wong, P.W.; Leung, A.Y.; Lou, V.W.; Chan, G.M.; Schulz, R. Multicomponent intervention on enhancing dementia caregiver well-being and reducing behavioral problems among Hong Kong Chinese: A translational study based on REACH II. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiatti, C.; Rimland, J.M.; Bonfranceschi, F.; Masera, F.; Bustacchini, S.; Cassetta, L.; Lattanzio, F.; UP-TECH research group. The UP-TECH project, an intervention to support caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients in Italy: Preliminary findings on recruitment and caregiving burden in the baseline population. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Lee, C.C.; Perdomo, D.; Loewenstein, D.; Bravo, M.; Moxley, J.H.; Schulz, R. Community REACH: An implementation of an evidence-based caregiver program. Gerontologist 2018, 58, e130–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Loewenstein, D.; Schulz, R.; Nair, S.N.; Perdomo, D. A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easom, L.R.; Alston, G.; Coleman, R. A rural community translation of a dementia caregiving intervention. Online J. Rural. Nurs. Health Care 2013, 13, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortinsky, R.H.; Kulldorff, M.; Kleppinger, A.; Kenyon-Pesce, L. Dementia care consultation for family caregivers: Collaborative model linking an Alzheimer’s association chapter with primary care physicians. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, K.S.; Sobol, N.; Beyer, N.; Hasselbalch, S.; Waldemar, G. Moderate-to-high intensity aerobic exercise in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Gallagher-Winker, K.; Kehrberg, K.; Lunde, A.M.; Marsolek, C.M.; Ringham, K.; Thompson, G.; Barclay, M. The Memory Club: Providing support to persons with early-stage dementia and their care partners. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2011, 26, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, F.A.; Nazarian, N.; Lavretsky, H. Feasibility of central meditation and imagery therapy for dementia caregivers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, A.P.; van Hout, H.P.; Nijpels, G.; Rijmen, F.; Dröes, R.M.; Pot, A.M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Stalman, W.A.; van Marwijk, H.W. Effectiveness of case management among older adults with early symptoms of dementia and their primary informal caregivers: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.K.; Niedens, M.; Wilson, J.R.; Swartzendruber, L.; Yeager, A.; Jones, K. Treatment outcomes of a crisis intervention program for dementia with severe psychiatric complications: The Kansas Bridge Project. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joling, K.J.; van Marwijk, H.W.; Smit, F.; van der Horst, H.E.; Scheltens, P.; van de Ven, P.M.; Mittelman, M.S.; van Hout, H.P. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? A randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiosses, D.N.; Arean, P.A.; Teri, L.; Alexopoulos, G.S. Home-delivered problem adaptation therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: A preliminary study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiosses, D.N.; Gross, J.J.; Banerjee, S.; Duberstein, P.R.; Putrino, D.; Alexopoulos, G.S. Negative emotions and suicidal ideation during psychosocial treatments in older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunik, M.E.; Snow, A.L.; Wilson, N.; Amspoker, A.B.; Sansgiry, S.; Morgan, R.O.; Ying, J.; Hersch, G.; Stanley, M.A. Teaching Caregivers of Persons with Dementia to Address Pain. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.M.; Huang, H.L.; Huang, H.L.; Liang, J.; Chiu, Y.C.; Chen, S.T.; Kwok, Y.T.; Hsu, W.C.; Shyu, Y.I. A home-based training program improves Taiwanese family caregivers’ quality of life and decreases their risk for depression: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.J.; Francis, A.; Ziaian, T. Transcendental Meditation for the improvement of health and wellbeing in community-dwelling dementia caregivers [TRANSCENDENT]: A randomised wait-list controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Sung, K.; Kim, Y.-E. Effects of home-based stress management training on primary caregivers of elderly people with dementia in South Korea. Dementia 2012, 11, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingler, J.H.; Butters, M.A.; Gentry, A.L.; Hu, L.; Hunsaker, A.E.; Klunk, W.E.; Mattos, M.K.; Parker, L.S.; Roberts, J.S.; Schulz, R. Development of a standardized approach to disclosing amyloid imaging research results in mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 52, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanque, S.M.; Enriquez, M.; Cheng, A.L.; Doty, L.; Brotto, M.A.; Kelly, P.J.; Niedens, M.; Caserta, M.S.; Savage, L.M. The family series workshop: A community-based psychoeducational intervention. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2015, 30, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, L.; Sandman, L.; Rosén, K.G.; Hanson, E. Extended safety and support systems for people with dementia living at home. J. Assist. Technol. 2014, 8, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, V.; Barker, C.; Stott, J. The effectiveness of an Internet support forum for carers of people with dementia: A pre-post cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paukert, A.L.; Calleo, J.; Kraus-Schuman, C.; Snow, L.; Wilson, N.; Petersen, N.J.; Kunik, M.E.; Stanley, M.A. Peaceful Mind: An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in persons with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prick, A.E.; de Lange, J.; Twisk, J.; Pot, A.M. The effects of a multi-component dyadic intervention on the psychological distress of family caregivers providing care to people with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 2031–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, B.; Buntinx, F.; Delepeleire, J. Supporting family carers of community-dwelling elder with cognitive decline: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Fam. Med. 2010, 2010, 184152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simpson, C.; Carter, P.A. Pilot study of a brief behavioral sleep intervention for caregivers of individuals with dementia. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2010, 3, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stanley, M.A.; Calleo, J.; Bush, A.L.; Wilson, N.; Snow, A.L.; Kraus-Schuman, C.; Paukert, A.L.; Petersen, N.J.; Brenes, G.A.; Schulz, P.E.; et al. The peaceful mind program: A pilot test of a cognitive-behavioral therapy-based intervention for anxious patients with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.; Leoutsakos, J.M.; Podewils, L.J.; Lyketsos, C.G. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: The Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steis, M.R.; Prabhu, V.V.; Kolanowski, A.; Kang, Y.; Bowles, K.H.; Fick, D.; Evans, L. Detection of delirium in community-dwelling persons with dementia. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2012, 16, 1274. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, T.; Regehr, C. The influence of community-based services on the burden of spouses caring for their partners with dementia. Health Soc. Work 2009, 34, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappen, R.M.; Hain, D. The effect of in-home cognitive training on functional performance of individuals with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 7, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, L.D.; Meiland, F.J.; Dröes, R.M. Dementelcoach: Effect of telephone coaching on carers of community-dwelling people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, M.; Shuman, S.B.; Wiener, J.M.; Gould, E. Challenges in Involving People with Dementia as Study Participants in Research on Care and Services; Research Summit on Dementia Care; US Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Lloyd, V.; Gatherer, A.; Kalsy, S. Conducting qualitative interview research with people with expressive language difficulties. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 1386–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Phinney, A.; Smith, A.; Small, J.; Purves, B.; Perry, J.; Drance, E.; Donnelly, M.; Chaudhury, H.; Beattie, L. Personhood in dementia care. Developing a research agenda for broadening the vision. Dementia 2007, 6, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smebye, K.L.; Kirkevold, M.; Engedal, K. How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? A multi-case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H. Including people with dementia in research: Methods and motivations. In The Perspectives of People with Dementia: Research Methods and Motivations; Wilkinson, H., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2002; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, J.L.; Cote, J.A. Defining consumer satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2000, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goeman, D.; Renehan, E.; Koch, S. What is the effectiveness of the support worker role for people with dementia and their carers? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Hartmann, M.; Wens, J.; Verhoeven, V.; Remmen, R. The effect of caregiver support interventions for informal caregivers of community-dwelling frail elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Måvall, L.; Malmberg, B. Day care for persons with dementia: An alterantive for whom? Dementia 2007, 6, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, K.; Tiit, E.-M.; Verbeek, H.; Raamat, K.; Armolik, A.; Leibur, J.; Meyer, G.; Zabalegui, A.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Karlsson, S.; et al. RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Most appropriate placement for people with dementia: Individual experts’ vs. expert groups’ decisions in eight European countries. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lethin, C.; Hallberg, I.R.; Vingare, E.-L.; Giertz, L. Persons with Dementia Living at Home or in Nursing Homes in Nine Swedish Urban or Rural Municipalities. Healthcare 2019, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lethin, C.; Renom-Guiteras, A.; Zwakhalen, S.; Soto-Martin, M.; Saks, K.; Zabalegui, A.; Challis, D.J.; Nilsson, C.; Karlsson, S. Psychological well-being over time among informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lethin, C.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Bleijlevens, M.; Stephan, A.; Martin, M.S.; Nilsson, K.; Nilsson, C.; Zabalegui, A.; Karlsson, S. Predicting caregiver burden in informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home—A follow-up cohort study. Dementia 2020, 19, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Aranaz, J. Patient satisfaction as an outcome measure in health care. Med. Clin. 2000, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).