Abstract

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease and one of the major issues of health concern, especially for the public health system globally. Nature is a source of anticancer drugs with abundant pool of diverse chemicals and pharmacologically active compounds. In recent decade, some natural products and synthetic analogs have been investigated for the cancer treatment. This article presents the utilization of natural products as a source of antitumor drugs.

1. Introduction

An abnormal development of cells that promulgates through the splitting of unrestricted cells is referred to as cancer. Cancer has been highlighted as one of the major issues of concern most especially for the public health system globally, and the US National Cancer Institute have forecasted with up rise of 50% in cancer cases, which will drastically increase to 21 million new cases in approximately two decades to this period [1]. According to the projection, it is likely to record seven out of ten deaths as a result of cancer in Central and South America, Asia, and Africa. This is an alarm that most developing countries need to upgrade and develop more strategic planning that borders around the issues of surveillance, early detection, and operational treatment for cancer patients [2]. Normally, individuals at a different time of their ages may be affected by cancer but there is a probability that the cancer diseases increases with increase in age [3]. This might be due to the accumulated DNA damage and multi-stage carcinogenesis as one becomes older [4,5,6].

The traditional approaches for cancer treatment include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [7,8]. Conversely, irrespective of the numerous type of synthetic drugs that have been utilized for the cancer chemotherapy and the healing accomplishment of various management schedules, the prevailing therapies have not yielded the level of expected result as tumor relapse and the beginning of metastasis often take place [9,10]. In light of this, there is a need to pursue more selective active compounds that have fewer side effects, are cost-effective, have more medicinal attributes, and have a minimum level of disease resistance have been enlisted as a major significant attribute necessary for cancer treatment most especially from biological and natural sources. Nevertheless, little information exists regarding the utilization of biological natural compounds and their cellular and molecular modes of action against cancer diseases. The late diagnosis and non-responsive therapy is a major reason of higher mortality among many cancer patients. This has instigated the need to search for an alternative cancer drug. The application of natural synthetic moieties is lead molecules that are preferable to some chemodrugs due to their various uncountable side effects [11,12].

The etiological process involved in the multiplying of a cancerous cell has been observed to be facilitated by some pathways or some mechanisms of action [13,14]. It has been stated that some active compounds derived from natural sources could be used effectively as a therapeutic technique for the treatment of these cancerous cells [15]. To date, more than 60% of synthetic drugs are derived from natural sources, out of which natural active compound most especially from plant constitutes 75% of anticancer drugs [16,17]. The natural product obtained from different sources portends the capability to enhance numerous physiological pathways which are necessary for the treatment of stalwart diseases [18] including cancer [19]. Therefore, it has become imperative to apply various strategies for the management of these stubborn diseases using natural products, most especially phytochemicals from biological sources most especially from plants [20,21]. This might be linked to the involvement of some crucial phytochemicals that have the capability to inhibit many pathways and prevent some malignancies, as well as the crucial roles they play in the inhibition of these dangerous cancer cells [22].

Nature is a rich source of anticancer drugs that are obtained from natural sources [23]. This might be linked to their abundant pool of diverse chemotypes and pharmacologically active. Moreover only a small percentage from these biologically active compounds derived from natural products have been formulated into clinically active drugs but their active compounds could be a model that will be followed for the formulation of more effective analogs and prodrugs through the utilization of chemical techniques like metabolomics, total or combinatorial fabrication or alteration of their biosynthetic pathways.

Furthermore, recent advances in formulating consortium of novel biologically active compounds may lead to may result in more efficient administration of the drug to patients. This might also include the fusion of toxic natural molecules to monoclonal antibodies and polymeric carriers precisely directed towards epitopes on the targeted tumor cell, which could result in the discovery of more active antitumor drugs. This also requires the inputs of multidisciplinary collaborations among different scientists to optimize and standardized the most active biological compounds and their adequate effectiveness as antitumor drugs at the molecular level [24,25,26,27,28].

For the past 10 years, some natural products have been discovered as a major source of drugs which have been utilized for the management of cancer chemotherapy, whereas almost 70% of them have been validated in various stages of clinical trials [16,17,29,30]. Some examples of antitumor drugs derived from plant compounds are Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) [31,32,33,34] and Paclitaxel (Taxol®), which is a taxane dipertene present in the crude extract obtained from the bark of Taxus brevifolia Nutt. (Western yew) [35]. Another example is Taxol (essentially all taxanes), which hinders microtubule disassembly by joining the microtubules that have been polymerized [35,36,37,38,39]. The bioavailability of these compounds is usually discussed, i.e., in the case of curcumin low bioavailability is addressed by using higher concentrations within nontoxic limits and its combination with other compounds or as formulations [40].

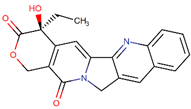

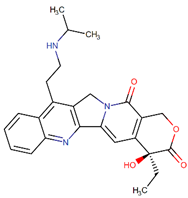

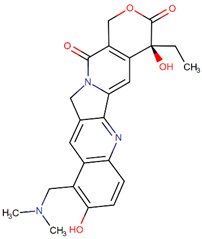

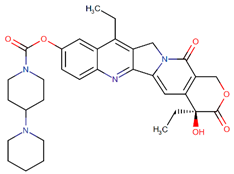

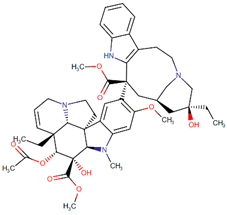

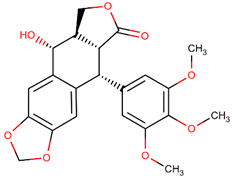

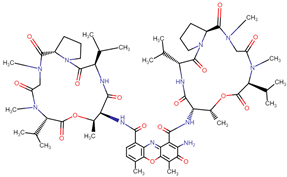

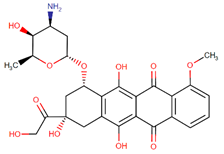

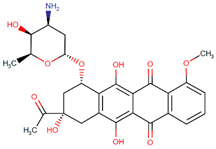

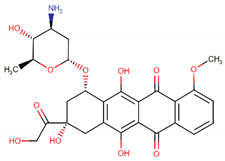

Examples of antitumor synthetic analogs derived from plant, which have been validated scientifically, include paclitaxel (Taxols) and the analogs docetaxel (Taxoteres) and cabazitaxel (Jevtanas); camptothecin and analogs belotecan (Camptobells), topotecan (Hycamtins), and irinotecan (Camptosars); vinblastine (Velbans), vincristine (Oncovins), and their analogs vindesine (Eldisines) and vinorelbine (Navelbines); and podophyllotoxin and analogs etoposide (Etopophoss) and teniposide (Vumons). Moreover, bacterial derived from the soil have also shown a lot of potential as a great source of antitumor drugs like the glycopeptide bleomycin (Blenoxanes), the nonribosomal peptide dactinomycin (Cosmegens), anthracyclines doxorubicin (Doxils; Adriamycins) and daunorubicin (Cerubidines), and epirubicin (Ellences) (Table 1) [17,24,41].

Table 1.

Natural antitumor drugs and synthetic analogs.

The compact and unusual structural configuration of some of these natural compounds plays a crucial role in their joining together to specific targets or molecular interfaces. This might result in some level of phenotypic alteration, most especially in biological systems that involve fixing of natural molecules, entails structural requirements that allow their binding to specific targets or molecular interactions [42,43]. Some of these features shared the same similar medicinal attributes in the most different diseases. It has been validated that 64% of drugs derived from natural products are effectually used in the development of these drugs [17,44].

Moreover, due to the invaluable biological diversity of natural products, there is a need to still search for more effective antineoplastic activity active compounds from microorganisms, most especially from marine sources and from unexploited plants because some of these compounds might show exceptional activities when tested against new medicinal targets [41,45]. Examples of marine-derived anticancer drugs include the conjugated antibody brentuximab vedotin (Acentriss), cytarabine (Cytosars), eribulin mesylate (Halavens), and trabectedin (Yondeliss) [46,47,48].

Therefore, this review presents a holistic view of the current trends towards the utilization of natural products and synthetic analogs as a source of new antitumor drugs that have been reported for the past decade. Moreover, recent information about antitumor drugs derived from various sources and their general bioactivity towards the management of different types of cancer is well elaborated in this review work.

2. Antitumor Drugs: A Brief Medical History, Different Origins, and General Bioactivity

Cancer has been reported as the second most common cause of death with an estimated 9.6 million deaths in 2018 by the World Health Organization [49]. It is not an emerging disease: people have been suffering from cancer throughout the world for centuries. Between 460 and 370 B.C, Hippocrates used the word cancer for the first time to describe carcinoma tumors [50]. However, this disease is not discovered by Hippocrates. The pieces of evidence showed that bone cancer was reported in ancient Egypt mummies in approximately 1600 B.C. and breast cancer in 1500 B.C.; however, there was no recorded treatment for cancer [51].

Considering the earliest reports on the nature of cancer, first findings dates back to 1761, when Giovanni Battista Morgagni, regarded as the father of modern anatomical pathology, did autopsies for the first time on dead bodies to elucidate the relation between patient’s illness and pathologic observations. Giovanni’s studies provided the basis of scientific cancer strategies [52]. Additionally, John Hunter who introduced the idea that surgery could be a strategy for the patients whose tumors have not invasive and moveable characteristics to nearby sites, he said: “there is no impropriety in removing it.” [53]. A century later, anesthesia was invented, and surgeons Bilroth, Handley, and Halsted carried out cancer operations by removing the entire tumor. Development of modern microscope accelerated the studies in the era of scientific oncology in the 19th century and Rudolf Virchow, the founder of cellular pathology, laid the foundation of the modern pathologic study of cancer [54]. Thus, damages caused by cancer on the body could be detected. Moreover, the efficiency of operations could be examined by this method whether the cancerous tissue had been completely removed from the cancer site [54].

Early in the 20th century, surgery and radiotherapy were the two most dominated modalities to cure cancer diseases [55]. The term ‘‘chemotherapy’’ was provided into literature by the famous German chemist Paul Ehrlich in the early 1900s. It means the therapeutic use of chemicals to treat diseases [56]. He was also the first scientist who evaluated the potential biological activities of a group of chemicals in animal models. He is a pioneer to overcome the major limitation in the cancer drug development process before clinical stages [56,57].

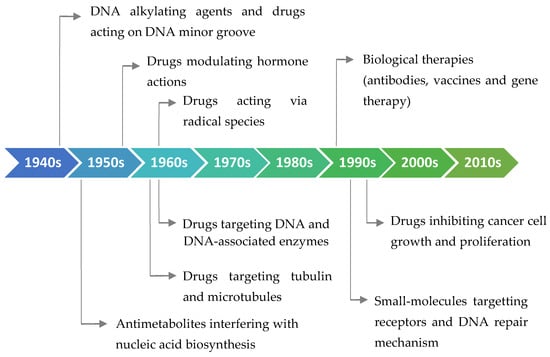

In the middle of the 20th century, during the World War II, breakthrough information emerged in the field of chemotherapy. It was reported that people exposed to mustard gas in the field of military action had toxic changes in the bone marrow cells [57,58]. As a result of these surprising findings, researchers focused on the mustard gas-related compounds to identify effective compounds to cure cancer. After much effort on their part, the first anticancer drug, called mechlorethamine (Mustargen®), was approved for the treatment of lymphoma and reached the markets in 1949 as a nitrogen mustard alkylating agent [57,59,60]. The discovery of nitrogen mustard paved the way for the synthesis of other anticancer drugs. Sidney Farber, in 1948, showed the effectiveness of aminopterin, a folic acid antagonist, against childhood leukemia and it was the predecessor of the drug methotrexate that is still utilized in clinics [58]. When the historical development of antitumor agents has been examined, it can be seen that drugs that were discovered in the second half of the 20th century have generally exerted their effects through direct binding to DNA thus creating cell toxicity (Figure 1). However, in the 21st century, with the advent of molecular biology techniques, the action mechanism of chemotherapeutic agents has become quite specific. The trend has been changing from small molecules to protein-based therapeutics as well as their small molecules conjugated forms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification of the antitumor drugs according to their action mechanism and timeline showing their history.

These findings were significant milestones in anticancer drug developments which result in an increased number of drugs reaching to the markets [60]. Between 1950 and 1980, on average, two new drugs were approved for their anticancer activities a year. Moreover, this number was doubled in the 1990s. An average of 10 novel oncologic drugs hit the markets in the years between 2011 and 2019 per year [59]. Unlike the drug development process in the past, it takes ~13–15 years for the validation of drugs in the preclinical and clinical phases. There are several stages in this workflow, including determination of molecular and phenotypic targets; design, in silico analysis, and synthesis of hit molecules; in vitro and animal studies for the elucidation of biological effects of test compounds; and optimization of a candidate compound for clinical studies. The efficacy, safety, and possible side effects of drugs are tested through clinical phases [61]. In the following sections, the latest drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) USA in the last decade are summarized according to their mechanism of action. Nearly, 80% of FDA-approved drugs during the last three decades for cancer treatment are either natural products per se or derivatives [62].

2.1. FDA-Approved Small Molecules as Antitumor Drugs in the Last 10 Years

In the last decade, more than fifty small molecules as antitumor agents have been approved by the FDA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Small molecules. Some data were drawn from DrugBank [102].

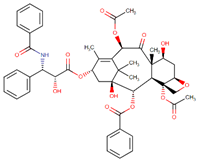

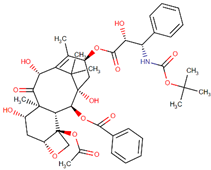

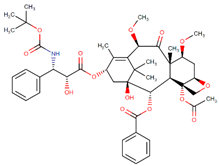

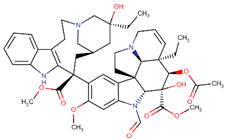

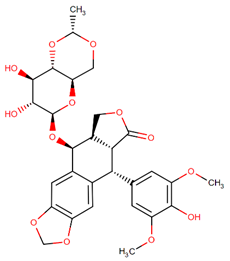

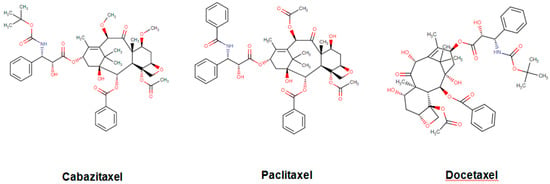

Among these drugs, cabazitaxel (Jevtana) is a second-generation semisynthetic taxane derivative approved in 2010 by the FDA, especially for the treatment of metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Taxanes are a class of diterpenes, which were originally identified from plants of the genus Taxus (yews). Paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere) are widely used progenitor of cabazitaxel (Figure 2). Their mechanism of action involves microtubule stabilization to induce cell death. In general, they bind to tubulin subunits and promote the assembly of microtubules while simultaneously inhibiting its disassembly. This leads to arrest in the cell cycle at the metaphase and triggers apoptosis in the cancerous cell. Although they have a similar mechanism of action, cabazitaxel has an advantage over paclitaxel and docetaxel, due to having extra methyl groups that mitigate constitutively and acquired antitumor drug resistance by inhibiting the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump [63,64]. Besides, cabazitaxel is more effective in central nervous system (CNS) metastases because of its ability to pass through the blood–brain barrier [64].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of cabazitaxel, paclitaxel and docetaxel.

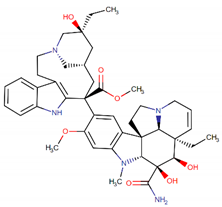

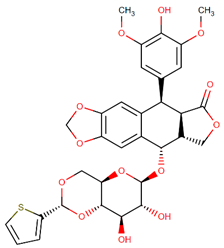

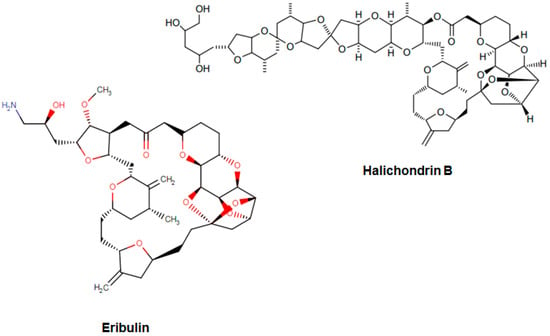

Eribulin (Havalen) was isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai. It is a non-taxane microtubule inhibitor with a novel mode of action and was approved by FDA in 2010 for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer who have previously administered with at least two chemotherapeutic protocols. Although it is a fully synthetic organic molecule, its structure was inspired by halichondrin B, which is a polyether macrolide isolated from the rare marine sponge in 1986 by Hirata and Nemura [65]. The studies with halichondrin B had reported a remarkable microtubule-associated in vivo and in vitro anticancer activity [66]. As a result of these findings, in 1992, the total synthesis of halichondrin B was achieved by Kishi and colleagues [67]. Several studies with this compound revealed that macrocyclic lactone C1–C8 moiety on the right half of the molecule retains its cytotoxic activity [67]. Although Eribulin is a structurally much simpler analog of halichondrin B, it retains a biologically active pharmacophore of the original molecule (Figure 3) [68,69,70].

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of eribulin and halichondrin B.

The cytotoxicity of eribulin is mediated through microtubules; however, its mode of action is different from other tubulin-binding agents such as taxanes and vinca alkaloids [71,72]. These agents bind along the sides of microtubules, specifically eribulin, and limitedly bind on the (+) ends of the structure, thus inhibiting polymerization but not depolymerization (shortening) of its growth. Therefore, eribulin results in the arrest of the cell cycle at the G2/M phase thus activation of the apoptotic processes and subsequently cell death [66,73,74,75].

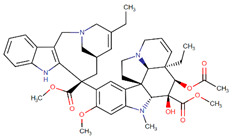

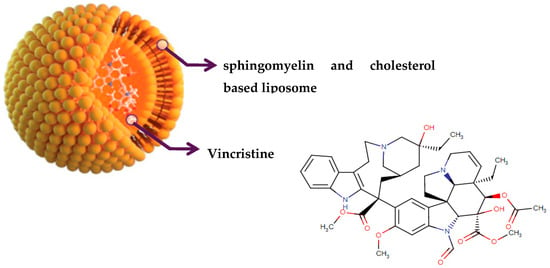

Another potent and widely used chemotherapeutic agent representing its antitumor activity through microtubule inhibition is vinciristine—a kind of plant alkaloid. It was first isolated from the extract of the periwinkle plant Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don (formerly known as Vinca rosea L.) in the scope of a screening program exploring the potential antidiabetic agents [76,77,78]. The action mode of vincristine includes microtubule depolymerization through binding to tubulin subunits resulting in metaphase arrest and finally apoptotic cell death. Although vincristine has been effectively used for more than 50 years in the treatment of hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, it has important limitations due to its suboptimal pharmacokinetic profiles and dose-related neurotoxicity [79]. VinCRIStine sulfate Liposome injection (Marqibo) is a novel and therapeutically improved formulation of vincristine encapsulated in sphingomyelin and cholesterol based nanoparticles. This liposome-remodeled form of the active compound is approved by FDA in 2013 for the treatment of relapsed Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of vincristine and formulation of VinCRIStine sulfate liposome injection (Marqibo).

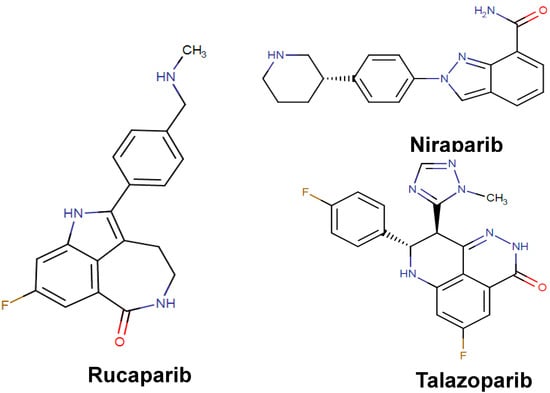

In the last decade, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), which are ubiquitous zinc finger DNA-binding enzymes, have been established as well-known targets of several oncologic drugs The cellular roles of PARP proteins include regulation of homologous recombination, transcription, and replication processes, as well as DNA repair mechanism under any stress conditions [80]. Inhibition of the PARP proteins can bring about the stimulation of apoptotic pathways through NAD+/ATP depletion, loss of mitochondrial membrane dynamics, and the production of excess amount of apoptosis-inducing factor [80]. Recently, the drug rucaparib (Rubraca, Figure 5), found in the class of piperidine type organic compounds, has been approved by FDA (2016) as a potent PARP-1, -2, and -3 inhibitor for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in women with deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutation [81]. Soon after, another piperidine compound, niraparib (Zejula, Figure 5), was approved by the FDA (2017) for its effectiveness on recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer [82]. The drug exerts its effect by specifically inhibiting PARP-1 and PARP-2 activation resulting in niraparib-induced cytotoxicity in cancerous cells. Very recently, a kind of quinoline derivative talazoparib (Talzenna, Figure 5) has been approved by FDA (2018) for use in the treatment of germline BRCA mutated, HER2-negative, locally advanced, or metastatic breast cancer due to its inhibitory effect on PARP-1 and PARP-2 proteins [83].

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of rucaparib, niraparib, and talazoparib.

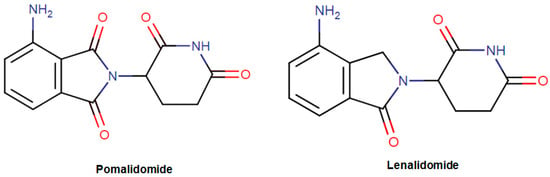

Chronic inflammation refers to the uncontrolled immune response of living organisms to initiate a defense mechanism against several endogenous and exogenous stimuli [84,85,86]. However, a prolonged inflammatory response is associated with the production of an excess amount of reactive nitrogen/oxygen species, persistent cytokine release and sustained immune response [85,87]. This might lead to various inflammation-related pathological diseases including type II diabetes, coronary-neurologic disorders, as well as cancer [88,89]. The drug pomalidomide (Pomalyst; found in the family of organic compounds called phthalimides—Figure 6) was approved in 2013 by the FDA to be used in the treatment of patients having relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma [90]. It has been demonstrated that the drug is an immunomodulatory agent with multiple actions including the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on tumor cells. As having immune modulatory effects, the drug is highly effective inhibitors of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and even transcription of COX2 [90]. It is thought the primary biological target of the drug is the protein cereblon to suppress ubiquitin ligase activity. In the same year, another drug called lenalidomide (Revlimid; found in the family of organic compounds known as isoindolones—Figure 6) was introduced into the markets for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. It has been shown that the drug inhibited the release of proinflammatory cytokines and increased the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells [91]. In addition to these effects, the drug inhibited the expression of COX-2 selectively but not COX-1. Additionally, the drug stimulated the apoptosis of tumor cells by the inhibition of bone marrow stromal cell support and immunomodulatory activity [92].

Figure 6.

The structure of pomalidomide and lenalidomide.

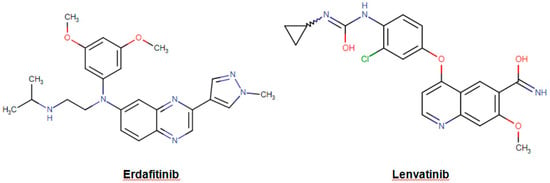

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are a group of cell surface receptors that are responsible for the regulation of cell growth, motility, differentiation, and survival [93]. The sustained activation and expression level of RTKs have been found to be correlated with the abnormalities in the downstream signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) and Janus kinase/signal transducers, and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathways, which may finally result in cancer development and uncontrolled proliferation of the cells [94,95]. Therefore, during the past decade, different domains of RTKs including extracellular, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains have been studied extensively as therapeutic targets in the development of anticancer agents [96]. The drug erdafitinib (Balversa; found in the class of organic compounds named alkyldiarylamines, Figure 7) is the latest FDA-approved (April 2019) oncologic drug as well as the first-ever fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) kinase inhibitor for the treatment of patients who are suffering from advanced urothelial carcinoma [97]. In normal tissues, FGFR proteins ubiquitously expressed for the regulation of various physiological processes such as phosphate and vitamin D homeostasis, as well as proliferation and antiapoptotic signaling of the cells [98]. However, in the case of cancer, upon binding of FGF ligands to the receptor, the downstream signal transduction is stimulated leading to permanent activation of phosphoinositide phospholipase C (PLCγ), MAPK, AKT, and STAT cascades [98]. The drug erdafitinib is said to be a selective inhibitor for the tyrosine kinase enzymatic activities of expressed FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4. The drug lenvatinib (Lenvima; an organic compound known as quinoline carboxamides, Figure 7) was approved by FDA in 2015 as a multipotent RTK inhibitor, which has been found to be effective in the treatment of patients with locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive thyroid cancer [99]. Lenvatinib inhibits the activities of several vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors VEGFR1 (FLT1), VEGFR2 (KDR), and VEGFR3 (FLT4). The production of endogenous VEGF is necessary for some physiological processes such as fetal development, menstruation, and wound healing in normal tissues [100]. However, the overproduction of VEGF is associated with abnormal tumor growth and metastasis by stimulating the formation of new blood vessels from existing vasculature [101]. Lenvatinib exerts its effect by binding to the adenosine 5′-triphosphate site of VEGFR and to a neighboring region, leading to inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity as well as downstream cascades. Lenvatinib also inhibits other RTKs including fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors FGFR1, 2, 3, and 4; the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα); KIT; and RET that have been implicated in the pathogenic angiogenesis, tumor growth, and cancer progression.

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of erdafitinib and lenvatin.

2.2. FDA-Approved Protein-Based Therapeutics in the Last 10 Years

Understanding the fundamental of proteins and novel techniques utilized in genetic engineering has made a great contribution to the field of the pharmaceutical industry. Unlike small molecule drugs, protein therapeutics cannot be produced via a sequence of chemical reactions, so natural sources, such as living cells or organisms, are essential hosts for the manufacture of a product [103,104]. Although protein-based drugs are highly target-specific and potent therapeutics, the characterization of final products is a highly challenging process because of their large molecular size, exhausting purification steps, as well as individual variations in cancer patients [105].

Similar to numerous small molecules, a group of protein-based therapeutics has been approved for their inhibitory effect on RTKs and downstream signaling pathways. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a significant prognostic and predictive biomarker commonly researched in oncological clinics. The overexpression of the HER2 is much higher in the breast and gastric/gastroesophageal cancer patients [105]. Moreover, the HER2 positivity has been found to be associated with other cancer types such as ovary, endometrium, bladder, lung, as well as the colon [105]. Binding of ligands to the receptor leads to the autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic domain after that dimerization of receptors resulting in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion-related signaling pathway activations [106]. Elucidation of the structure and other characteristics of HER2 have paved the way for a more effective personalized therapeutic strategy in HER2-positive patients. The drug trastuzumab (Herceptin; recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody) has demonstrated high affinity against the extracellular domain of HER2, resulting in inhibition of cancer cells growth and proliferation, and increased survival in the breast and gastric cancer patients [107]. Additionally, the biosimilar drugs to Herceptin, named trastuzumab-dkst (Ogivri), trastuzumab-pkrb, (Herzuma), and trastuzumab-anns (KANJINTI), have been approved for their therapeutic effects in the patients with metastatic breast and gastric cancer.

As an alternative to small molecules that are able to inhibit the function of VEGF receptor, the protein-based drugs bevacizumab (Avastin; recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody) and ramucirumab (Cyramza; human IgG1 monoclonal antibody) have been introduced for their pharmacological actions against blood vessel proliferation and metastatic tumor growth in the patients with cervical cancer and gastric cancer respectively [108,109]. Bevacizumab exerts its effect by binding to VEGF and preventing the interaction between VEGF and its receptors, named Flt-1 and KDR, found on the surface of endothelial cells. On the other hand, ramucirumab shows high affinity against VEGFR2 and prevents the ligand-induced proliferation of endothelial cells by limiting the interaction between ligands (VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D) and VEGF receptor [108].

In 2018, the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet decided to award Tasuku Honjo jointly to James P. Allison in the category of Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of brake-like regulators found in the immune system [110]. T cells are a group of white blood cells that play a significant role in the defense mechanism of a living organism by trigger the immune system [111]. James P. Allison and other research teams have worked to elucidate the biological role of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) in the treatment of several cancers and autoimmune diseases models [112,113,114]. After the activation of T cells, the expression of CTLA-4 is stimulated, which downregulates immune responses by binding to the cluster of differentiation 28 receptors. James P. Allison proposed that the CTLA-4 blockade could encourage T cells to fight cancer cells [113,114]. The animal and clinical studies gave promising results for the treatment of advanced melanoma, a type of skin cancer [115]. In line with these developments, the designed drug ipilimumab (Yervoy; humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody) has been approved by FDA to be utilized for the 12 years and older patients with metastatic melanoma [116]. Its action mechanism is based on inhibition of the activity of CTLA-4, thereby sustaining the activation of T cells to fight against tumor cells.

Additionally, Tasuku Honjo discovered the protein known as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) that is localized in the T cell surfaces. PD-1 proteins behave like a brake in immune response results in inhibition of T cell activation [117]. Interestingly, Honjo and his research group demonstrated that blockage of PD-1 could be an effective strategy for cancer treatment in the animal models. These promising results led to high attention on PD-1 as a biological target in pharmacological research [117].

The drug pembrolizumab (Keytruda; humanized IgG4-kappa monoclonal antibody) has been approved by FDA in 2014 for the treatment of patients with lung cancer, advanced renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, metastatic cervical cancer, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma [118]. It binds to PD-1 with high affinity, thus the interaction between its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and the receptor is prevented to maintain T cell proliferation and cytokine production. Moreover, another drug called nivolumab (Opdivo; human IgG4 monoclonal antibody) shows a higher affinity to immune checkpoint PD-1 to induce the natural tumor-specific T cell immune response of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [119]. On the other hand, a number of approved drugs have been designed to block directly the PD-L ligands for the sustained T cell activation. Recently, the drug durvalumab (Imfinzi; human IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody) has been designed specifically for programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) to block the receptor–ligand interaction. It exhibited a curative effect in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer [120]. With the same action mechanism, atezolizumab (Tecentriq; Fc-engineered, humanized, monoclonal antibody) has been introduced for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma [121].

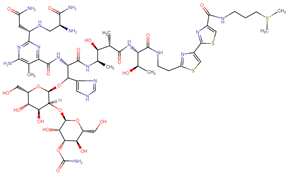

2.3. FDA-Approved Antibody–Drug Conjugates in the Last 10 Years

One of the latest improvements in chemotherapeutic strategies is combining a FDA-approved cytotoxic small molecule with an antibody directed to a specific protein found on the tumor cells. This strategy acts like a double-edged sword, allowing the specific targeting of the tumor cells while simultaneously delivering two potent cytotoxic agents [122,123]. Moreover, it provides preferable efficacy and reduced risk of systemic toxicity compared to the existing chemotherapy strategies [123]. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) is a kind of approved drug–antibody conjugate that is utilized for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer [124]. In this example, although the antibody compartment of the drug is HER2-specific humanized IgG1 (trastuzumab), which inhibits HER2 receptor signaling and leads to antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, the conjugated drug a maytansine derivative (DM-1) interferes with microtubules function, which results in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [125]. Another drug, brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), was approved by the FDA in 2011 for the treatment of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. However, one year later, it was revised with boxed warning due to post-treatment-based side effects and deaths. In March 2018, the FDA approved brentuximab vedotin to treat adult patients with previously untreated stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma. The drug combines an anti-CD30 human-murine IgG1 with the drug monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). Antibody provides the detection of cancer cells expressing CD30 whereas conjugated drug MMAE targets microtubules and distrupts their structure.

The strategy of protein-drug conjugate also provides design of therapeutic agents with improved half-life, qualified pharmocokinetics as well as stability. The drug calaspargase pegol-mknl (Asparlas) has been approved for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in pediatrics and young adults by the FDA in 2018 [126,127]. The drug contains Escherichia coli-derived enzyme L-asparaginase II and monomethoxy polyethylene glycol (pegol) linked by succinimidyl carbonate in its structure. The enzyme L-asparaginase converts the L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid, resulting in a sharp drop in the present asparagine concentration. This decrease blocks protein synthesis and tumor cell proliferation in the cancer tissue. Moreover, the conjugated pegol group decreases enzyme antigenicity and increases the half-life of the drug [127].

3. Plants and Related Bioactive Compounds as New Drug Sources for Different Cancers

3.1. Oral, Gastrointestinal, and Pancreatic Cancers

Since ancient times, in East Asia, traditional medicinal plants have been used to treat many diseases, including cancer [128,129,130]. In fact, in recent decades, despite the evolution of conventional treatments for oral cancer, morbidity and mortality rates have been steadily increasing. Indeed, the 5-year mortality rate is ~50% [131,132]. Recently, studies reported the anticancer effects of bioactive compounds from medicinal sources on oral cancer cell lines (Table 3). Nam, et al. [133] tested the anticancer activity of artemisinin and its various derivatives against oral cancer cell line (YD-10B) and they found as results an induction of apoptosis by the activation of caspase-3, which is the general mediator of apoptosis [134,135]. Several studies have evaluated the antitumor activity of eugenol in vitro against different oral cancer cells, and the results obtained showed that this compound had a good cytotoxic activity [136,137,138]. On the other hand, it has been shown that polyphenols also have anticancer properties [139]. Effectively, safrole, a polyphenolic compound of Piper betle L., has been tested in vitro on human buccal mucosal fibroblasts (BMFs) to prove its cytotoxic effect [140]. Additionally, phytochemicals reduce the risk of cancer [141]. Indeed, berberine, the main constituent of Coptis chinensis Franch., has been used in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders including oral cancer cells (KB, OC2) [142]. In addition, it proved effective against HSS3 oral cancer cells by inducing apoptosis [143]. Thus, it has been reported that carvacrol possesses antitumor properties [144]. Sertel et al. studied the antitumor activity of three medicinal plants on UMSCC1 cells and found a significant cytotoxic effect [145,146,147]. While Manosroi et al. [148] found the same effect regarding essential oils (EOs) from 17 Thai medicinal plants against KB cells, followed by Cha et al. [149,150] and Keawsa-ard et al. [151], who evaluated the anticancer effect of Artemisia gmelinii Weber ex Stechm. (synonym of Artemisia iwayomogi Kitam.) and Solanum spirale Roxb., respectively, on human mouth epidermal carcinoma (KB). EOs of aromatic and medicinal plants have many biological activities [152,153]. Moreover, EOs derived from the herbal plant Pinus densiflora Siebold & Zucc. can induce apoptotic cell death via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and activation of caspases in YD-8 human oral cancer cells. Note that the accumulation of ROS, under the conditions of oxidative stress, causes tissue toxicity by modifying cellular macromolecules such as proteins, lipids and DNA, which irreversibly alter cell viability and function [154,155]. In another study using the KB cell line, Artemisia capillaris Thunb. EOs had an anticancer effect related to the induction of apoptosis and activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [149,150]. The isolated limonoides of Azadirachta indica A.Juss. have been studied by Harish Kumar et al. [156], who showed apoptosis on the hamster buccal pouch (HBP) carcinogenesis model. Finally, other compounds used in the treatment of oral cancer such as chalcone extracted from the medicinal plant Alpinia pricei Hayata [157] and deoxyelephantopine (ESD) isolated from Elephantopus scaber L. [158] have shown the ability to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human oral carcinoma HSC-3 cells and human nasopharyngeal carcinoma (CNE) cells, respectively.

Table 3.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on oral cancer.

On the other hand, several bioactive compounds found in medicinal and aromatic plants have shown antitumor properties against gastrointestinal cancer [159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166]. The results of these works are summarized in Table 4. Liang et al, [159] tested Ganoderma against HCT116 cell line and showed that this compound induced apoptosis in HCT116 and increased caspase-8, caspase-3, and Fas. Genistein exerted an important antiproliferative effect, proapoptotic effect in vitro HT-29 cell line by increasing the expression of Bax or p21 proteins, and inhibiting NF-kB and topoisomerase II expression [162,163]. The combination of this compound with cisplatin inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis. On the other hand, the in vivo assay showed that some triterpenes are reported as antitumor drugs against HT-29 cell line via the suppression of proliferation and inhibition of tumor growth in the colon carcinoma xenograft model [160]. Ginkgo biloba has also exhibited an in vitro anticancer effect on HT-29 cell line by the inhibition of tumor progression, the increasing caspase-3 activity, the elevating p53 expression, and decreasing of bcl-2 expression. In another in vivo study, Romano et al [161] reported that cannabidiol exhibited an important anticancer activity on HCT116 mice xenograft through the reduction of the pre-neoplastic lesions and azoxymethane-induced polyps. Flavonoids compounds such as Apigenin, Isoliquiritigenin and Quercetin revealed important anticancer effects [166,167]. Their anticancer mechanisms are essentially related the inducing of apoptosis and/or arrest of cell cycle.

Table 4.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on gastrointestinal cancer.

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most fatal of all cancers [168]. It has been estimated that 458,918 new cases of PC diagnosed in 2018 [169]. Like other types of cancer, several medicinal plants and plant-based products show effects against PC; indeed, several studies (Table 5) have described antitumoral effects of medicinal plants [170]. Berkovich, et al. [171] revealed that the effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. leaf extracts on the survival of cultured human pancreatic cancer cells (Panc-1 cells) using flow cytometry analysis. They showed an inhibition of the growth of all pancreatic tested cell lines and inducing an elevation in the sub-G1 cell population of the cell cycle [171]. Moreover, Win et al. [172] reported that the chloroform extract of rhizomes of Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf exhibited important cytotoxic effects against PC cell lines. In addition, studies have identified some molecules with properties against PC [173,174,175]. Indeed, plumbagin, a quinoid isolated from the roots of Plumbago zeylanica L., showed important anticancer effect by inducing an apoptosis action and decreasing therefore cell viability of PC cells (Panc-1, BxPC3, and ASPC1). Moreover, in vivo approach has revealed that this compound inhibited the both tumor weight and volume [173]. The use of mimosine, a plant amino acid, subcutaneously growing human PC xenografts in immunosuppressed mice, resulted in significant tumor growth suppression and the sub-G1 fraction, and exerts an apoptotic activity assessed by flow cytometry [174]. Another study, shown that epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a polyphenolic compound from green tea, inhibits PC growth and induces apoptosis in human PC cells [175]. A number of studies have shown that the medicinal plant present cytotoxicity towards a number of PC cell lines. The chittagonga extract showed a significant cytotoxic effect on HTB126, Panc-1, Mia-Paca2, and Capan-1 cancer cell lines [176]. Moreover, the dichloromethane-soluble extract of Angelica pubescens Maxim. has significant effect against Panc-1 cancer cells [177]. The glycoside (a flavonoid isolated from Acacia pennata (L.) Willd.) exhibited a selective cytotoxicity on human pancreatic (Panc-1) [178]. Other volatile compounds such as Betulin and betulinic acid, which are naturally occurring pentacyclic triterpenes, revealed important anticancer effects [179]. Several studies have investigated activity apoptosis in human PC cells induced by medicinal plant and the products of these plants. Inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) decreased cellular growth and increased apoptosis [180]. Sorafenib induced an arrest of PC stem cells (CSC) [181]. On the other hand, triptolide extracted from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. significantly increased the apoptotic rates of human PC cells (SW199) [182].

Table 5.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on pancreatic cancer.

3.2. Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is a common disease that accounts for ~4.5% of human cancers, with an average rate of one million new cases each year. This prevalence is increasingly accelerated compared to other cancers. In, the different types of skin cancer cause today a significant morbidity rate, which shows the urgency to identify effective treatments; especially with side effects that are sometimes fatal, conventional treatments used. Today, the search for molecules that may have specific anticancer effects against skin cancer is a promising strategy. Indeed, a number of studies have shown that natural molecules containing in medicinal and aromatic plants have enormous capacity to inhibit tumor growth of skin cancer [183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190]. The cellular mechanisms involved in this anticancer action are numerous, including cell cycle arrest, the induction of apoptosis, and the inhibition of angiogenesis. The following table shows the anticancer properties of natural substances from medicinal and aromatic plants against skin cancer (Table 6). Studies have reported that medicinal plant extracts rich in phenolic compounds showed important anticancer activities against several skin cancer cell lines [187,191]. The polyphenols of Euphorbia lagascae Spreng. also showed an important cytotoxicity on melanoma SK-MEL-28 by an arrest of cell cycle at G2/M through downregulating cyclins A, E, and B1 expression [187]. Moreover, Tourino et al. [191] reported that the procyanidins of Pinus pinaster Aiton induced a cytotoxic effect on the same line (Melanoma SK-MEL-28). Tran et al. [192] demonstrated an antiproliferative activity of Dracaena angustifolia (Medik.) Roxb. saponins extracts. On the other hand, numerous isolated compounds from medicinal plants were reported to have antitumor effects on several skin cancer cell lines (Table 6). Certain flavonoids, such as flavone glycoside, exhibited important anticancer effects [183,185,190,193,194,195]. Indeed, Balasubramanian, Narayanan, and Kedalgovindaram and Devarakonda Rama [190] showed that flavone glycoside isolated from Indigofera aspalathoides DC. exhibited important cytotoxic effects on several melanoma cell lines (LOX IMVI, MALME-3M, SKMEL-2, SK-MEL-28, SK-MEL-5, UACC-257, and UACC-62). Anastyuk et al. [183] reported that the fucoidans identified in Fucus evanescens C. Agardh inhibited colony formation and cell proliferation of SK-MEL-28 and SK-MEL-5 cell lines. Another flavonoid (Galangin) isolated from Alpinia officinarum Hance showed cytotoxic effects on B16F10 cell line (murine melanoma cell) via the reducing of the mitochondrial membrane potential. In a remarkable study, Das et al. [195] reported that Apigenin isolated from Lycopodium clavatum L. showed an important in vitro cytotoxic effects on human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT. The anticancer activity of Apigenin involved the inhibition of the formation of ROS, and the interference with NF-kB and p38MAPK signaling pathways [195]. The volatile compounds such as terpenes and terpenoids isolated from EOs have also reported as anticancer agents against skin cancer [189,196,197,198]. Linalool (phenolic volatile compound) extracted from the EO of Satureja thymbra L. showed cytotoxicity against amelanotic melanoma C32 cell line by inhibiting tumor cells growth [196]. Fouche et al. [197] reported that the Sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell. exhibited remarkable in vitro cytotoxicity on Melanoma UACC-62 cell line. In another study, Darmanin et al. [198] showed that some terpenoids extracted from Ricinus communis L. EO, such as 1,8-cineole, camphor and pinene, and caryophyllene, showed important in vitro antiproliferative effects on SK-MEL-28 cells via the inducing of an apoptotic action. Natural alkaloids showed also anticancer properties against skin cancer. This is isoquinoline isolated from Berberis aristata DC., which inhibited the growth of human epidermoids carcinoma cell (A-431). 4-Nerolidylcatechol is another natural drug isolated from Piper umbellatum L. (synonym of Pothomorphe umbellate (L.) Miq.) and has shown important antitumor activity on SK-MEL2, SK-MEL-103, and SK-MEL-147 cell lines. This activity is mediated by the G-1 phase arrest, the inhibition the effect of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity, and the loss membrane integrity [184]. Some authors, such as Aggarwal et al. [199] and Niles et al. [200], reported the anticancer activity of Resveratrol (natural compound isolated from Vitis vinifera L.) on melanoma (A-375, A-431, and SK-MEL-28). Resveratrol exhibited several anticancer mechanisms, such as the enhanced of the phosphorylation of ERK1/2; the inducing of cell cycle arrest at G1-phase; the inducing of the downregulating of the protein expression of cyclin D1, D2, and E; and also cdk2, cdk4, and cdk6 [199,200].

Table 6.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on skin cancer.

3.3. Brain Cancer

Brain cancer develops in the brain or spinal cord and is categorized into four grades [169], with 296,851 new cases diagnosed in 2018 [201]. The fatality rate due to brain cancer is the highest [202]. Due to their chemical composition, recently, a number of studies have shown that medicinal plant products have anticancer properties against different types of brain cancers. Indeed, numerous compounds from medicinal species, such as Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Annona glabra L., Bupleurum scorzonerifolium Wild., and Bursera microphylla A. Gray, have shown promising therapeutic effects on brain cancers. Table 7 summarizes the antitumor effects of these medicinal plants on brain cancer [203] have investigated the anticancer property the EO of Croton regelianus Müll. Arg. using in vitro and in vivo approaches. The in vitro assay showed that this oil displayed an important cytotoxicity in HL-60 and SF-295 cell lines Moreover, the in vivo study, using sarcoma 180 as a tumor model, demonstrated inhibitions rate of 28.1% and 31.8% for HL-60 and SF-295, respectively [203,204], which demonstrated that both extracts (Leaf oil and berry oil) of Juniperus phoenicea L. exhibited important activities against brain cancer human cell lines [204]. However, the ethanolic extract of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi inhibited the cellular growth in recurrent and drug resistant brain tumor cell lines [205]. In another work, the treatment of GBM cells by chloroform extract of A. sinensis showed an anticancer effect by displaying the potency in suppressing growth of malignant brain tumor cells by cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Moreover, the in vitro assay showed that A. sinensis triggered both p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways for apoptosis and shrink the volumes of in situ GBM [206].

Table 7.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on brain cancer.

In addition, studies have identified some molecules with anticancer properties on brain cancer cell lines. Indeed, carvone (volatile compound extracted from several aromatic plants) exhibited remarkable anticancer effects on brain cancer. Its effects are essentially related to increasing in antioxidant level in cancer cells and a potential treatment of brain tumor in primary rat neuron and neuroblastoma (N2a) cells [207]. β-elemene, another volatile compound, extracted from Curcuma aromatica Salisb. (synonym of Curcuma wenyujin) has shown important anticancer effects on brain cancer. Using an MTT assay and semiquantitative Western blot, the authors demonstrated that this compound inhibited brain carcinomas via the inhibition of U87 cell viability through the activation of the GMFβ signaling pathway. It regulated also the cellular growth, fission, differentiation, and apoptosis [208]. Some flavonoids (fisetin, quercetin, and luteolin) extracted from medicinal plants have reported to be the anticancer agents. Indeed, they inhibited the cancer cell lines growth through the inhibition of protein kinase C (PKC) in brain cancer. This inhibition is mainly effects dose dependent manner and also depending on flavonoid structure [209]. Antioxidant flavonoid compounds, such as delphinidin, pelargonidin, and malvin, are cytotoxic natural agents [210]. Another type of flavonoid (isoflavones), and also an isomer of flavone, was reported as antitumor drugs. Indeed, they decreased the phosphorylation of Akt and eIF4E proteins and rendered U87 cells more sensitive to rapamycin treatment [211].

However, n-butylidenephthalide (BP), which is isolated from the chloroform triggered both p53-dependent and -independent pathways for apoptosis in vitro on glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells and suppressed growth of subcutaneous rat and human brain tumors and also, reduced the volume of GBM tumors in vivo [212]. In another study, the authors reported that the effects of BRM270 on glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) in vitro and GBM recurrence in vivo induced apoptotic cell death and inhibited cell growth [213]. N-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) retinamide (4-HPR) has shown activity on two human glioblastoma, T98G and U87MG, cell lines, such as induction of both differentiation and apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells [214]. Moreover, the use of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (bioactive polyphenol in green tea) on GSLCs, which is enriched in human glioblastoma cell line U87, using neurosphere culture has revealed a remarkable inhibited cell viability, neurosphere formation, and also induced apoptosis [215]. The administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) to GBM cell lines results in a significant decrease in cell viability via a mechanism that appears to elicit G1 arrest due to downregulation of E2F1, cyclin A. Δ9-THC, and cannabidiol acted synergistically to inhibit cell proliferation on the U251 and SF126 glioblastoma cell lines as an essential mediator of cannabinoid antitumoral action [216,217].

3.4. Breast Cancer

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in developing countries [49], where cancer risk is increasing due to population aging, smoking, and physical inactivity. Several studies have reported the anticancer activity of medicinal plants and their bioactive compounds (Table 8). Liao et al. [218] had reported that the evodiamine—a main constituent of fructus Evodiae—inhibited the proliferation of NCI/ADR-RES cells and caused significant apoptosis with arrest of G2/M cell cycle progression. A study on human breast cancer MDA-231 cells reported that treatment of Sanguinarine isolated from the root of Sanguinaria canadensis L. induces remarkable apoptosis [219]. Indeed, this apoptosis may be due to effects on signaling pathways or changes in intracellular proteins [220]. Li et al. [221] studied the action of matrine—a major component derived from Sophora flavescens Aiton—on primary and metastatic breast cancer (MCF-7 and 4T1 cells) and they found that it induces cell death in breast cancer cells. Piperine, an alkaloid isolated from Piper nigrum L., has been shown to inhibit the growth of 4T1 cells and induce their apoptosis [222].

Table 8.

Activity anticancer of medicinal plants phytochemical compounds on breast cancer.

The exploration of the EOs of different plants revealed that they had anticancer potency against breast cancer [223]. Indeed, Boswellia sacra Flueck. EO was effective against T47D, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells with high cell mortality [224]. Previous studies investigated EOs of several plants, such as Pulicaria jaubertii E.Gamal-Eldin [225], Annona muricata L. [226], Cedrelopsis grevei Baill. & Courchet [227], Seseli transcaucasicum Pimenov & Sdobnina (synonym of Libanotis transcaucasica Schischk.) [228], Melissa officinalis L. [229], and Salvia officinalis L. [230], have shown a cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 cells. By testing the same cell line, Chen et al. [231] found that they have a high sensitivity towards Commiphora pyracanthoides Engl. and Boswellia carterii Balf.f. EOs. Also in 2013, [232] have observed an antiproliferative activity of EOs of two species of Thymus against MCF-7 cells [232], and in the same year, Porcelia macrocarpa R.E.Fr. EO resulted in viability of SKBr cells [233]. In addition, several authors have investigated the anticancer properties of EOs components, such as carvacrol, which induces apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells [234], and citral inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells [235]. Similar inhibiting of different phases of cell cycle has also been noted in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in response to other phytochemicals [236,237]. This cell arrest is a therapeutic strategy widely used in the prevention of growth and cell division in cancer cells [238]. Moreover, EOs, and their various constituents, present effective anticancer substances by acting on the evolution and expression of the cell cycle [220]. Other studies have focused on evaluating the anticancer activity in vitro of EOs of several medicinal plants against MCF-7 cells by showing their antiproliferative activity [239,240,241].

4. Conclusions and Future Remarks

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide and it is imperative to develop novel approaches to treat such diseases. The keystone in cancer combat has been conventional chemotherapy but it is associated with normal cell toxicities. Due to a lack of specificity, conventional cancer treatments often cause severe side effects and toxicities. Generally, natural agents are considered safe while treating or prevention diseases; however, some compounds as flavonoids have shown great potential in the combat against cancer [294]. Plant-derived compounds have a high impact as cancer therapeutic agents both alone or in combination with conventional drugs [295]. Current challenge against cancer is to develop new drugs that include the site specific delivery with low systemic toxicity [296]. A tumor represents a dynamic environment with changes in cell mass, extracellular matrix composition, angiogenic status, among other factors. Promising technologies offer new opportunities to develop new drugs for cancer treatment with lower toxicity associated, but there are still challenges in cancer treatment research: One example is that the formulation of targeted therapies requires the identification of satisfactory molecular targets that have key functions in the growth and survival of cancer cells, and the design and creation of drugs that effectively hit the mark. However, some of the potential targets that have been identified apparently lack places to which an anticancer drug can bind and, therefore, are not susceptible to pharmacological effects. Unfortunately, most of the anticancer FDA-approved drugs and other regulatory agencies have no effect on the overall survival of the cancer patient. Cancer cell lines and animal models are a valuable tool for cancer research but reports indicate that these preclinical models are highly incomplete and not match with results obtained from clinical studies [297]. Finding a way to design drugs that effectively hit the mark is a major challenge. Another example of challenge in cancer treatment is the drug resistance. More research is needed to discover the mechanisms of drug resistance and identify ways to overcome it.

This article focused on natural organic compounds and synthetic derivatives, but there are also natural inorganic compounds with potent anticancer activities. One example is arsenic trioxide (As2O3) which has been labeled as a poison for years, yet recently have gained importance in the therapy of leukemia and solid cancers [298]. A role change has also been occurred in organic compounds such as artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from the Artemisia annua L. (Sweet Wormwood). This compound and its derivatives represent an efficacious antimalarial drug group with an excellent safety profile and, recently, have shown anticancer drug potential [299]. These compounds represent two of the many examples of the power hidden in natural sources and, after many years of research, may become new promising drugs for cancer treatment.

Owing to the explosive rate of new anticancer drug development, there is an urgent need for a synergistic improvement of preclinical studies, clinical trials, pharmacovigilance, and post-marketing surveillance. Several pharmacological agents derived from natural compounds have shown anticancer activity via tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) through direct activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathway or modulation of diverse nonapoptotic pathways to upregulate death receptors [300]. Unfortunately, a lack of robust clinical studies evidence exists to support the in vitro and in vivo results of the widespread use of natural products for chemoprevention and therapy of cancer. Modern technologies and research approaches will uncover the detailed mechanisms of action of the natural products and synthetic derivatives. The development of therapeutic modalities, such as chronotherapy, using natural products and synthetic analogs should be further studied to explore the new cancer treatment avenue.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript. Conceptualization, J.S.-R.; validation investigation, resources, data curation, writing—all authors; review and editing, T.B.T., J.S.-R., A.B., M.M., N.M. and W.C.C., All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CONICYT PIA/APOYO CCTE AFB170007.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/ (accessed on 31 December 2017).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer: Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en (accessed on 31 December 2017).

- Cho, W.C. Molecular connections of aging and cancer. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvard, V.; Baan, R.; Straif, K.; Grosse, Y.; Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.P.; Cortinhas, A.; Bento, T.; Leitao, J.C.; Collins, A.R.; Gaivao, I.; Mota, M.P. Aging and DNA damage in humans: a meta-analysis study. Aging 2014, 6, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, D.B.; Chua, K.F.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Franco, S.; Gostissa, M.; Alt, F.W. DNA repair, genome stability, and aging. Cell 2005, 120, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z. Anticancer drug discovery in the future: An evolutionary perspective. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, N.; Bardin, C.; Chatelut, E.; Paci, A.; Beijnen, J.; Leveque, D.; Veal, G.; Astier, A. Review of therapeutic drug monitoring of anticancer drugs part two—targeted therapies. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 2020–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, E.A.; Sargent, D.J.; Grothey, A.; Kerbel, R.S. Drug rechallenge and treatment beyond progression—implications for drug resistance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Check Hayden, E. Cancer complexity slows quest for cure. Nature 2008, 455, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Eun, J.W.; Bae, H.J.; Chang, Y.G.; Kim, M.G.; Park, W.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Histone deacetylase 6 functions as a tumor suppressor by activating c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated beclin 1-dependent autophagic cell death in liver cancer. Hepatology 2012, 56, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.; Prasad, S.; Sung, B.; Krishnan, S.; Guha, S. Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer by Natural Agents From Mother Nature. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2013, 9, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, M.C.; Spicer, D.V.; Dahmoush, L.; Press, M.F. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 1993, 15, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane, K.; Tateishi, K.; Klose, R.J.; Fang, J.; Fabrizio, L.A.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Tempst, P.; Zhang, Y. PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoeb, M. Anticancer agents from medicinal plants. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Drugs and Drug Candidates from marine sources: An assessment of the current “state of play”. Planta Med. 2016, 82, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balunas, M.J.; Kinghorn, A.D. Drug discovery from medicinal plants. Life Sci. 2005, 78, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Yokota, T.; Ashihara, H.; Lean, M.E.; Crozier, A. Plant foods and herbal sources of resveratrol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3337–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, D.R.; da Rocha, A.B.; Schwartsmann, G. Anti-cancer drug discovery and development in Brazil: Targeted plant collection as a rational strategy to acquire candidate anti-cancer compounds. Oncologist 2000, 5, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, S.; Edmund, N.A.; Moore, D.T.; Small, G.W.; Shi, Y.Y.; Orlowski, R.Z. Dietary curcumin inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in models of human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3868–3875. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragg, G.M.; Grothaus, P.G.; Newman, D.J. Impact of natural products on developing new anti-cancer agents. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3012–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothaus, P.G.; Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Plant natural products in anticancer drug discovery. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basmadjian, C.; Zhao, Q.; Bentouhami, E.; Djehal, A.; Nebigil, C.G.; Johnson, R.A.; Serova, M.; de Gramont, A.; Faivre, S.; Raymond, E.; et al. Cancer wars: Natural products strike back. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Nature: A vital source of leads for anticancer drug development. Phytochem. Rev. 2009, 8, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithranga Boopathy, N.; Kathiresan, K. Anticancer drugs from marine flora: An overview. J. Oncol. 2010, 2010, 214186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, D.G.I. Modern natural products drug discovery and its relevance to biodiversity conservation. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.J.; Murphy, L.L.; Venema, R.C.; Singletary, K.W.; Young, A.J. Curcumin binds tubulin, induces mitotic catastrophe, and impedes normal endothelial cell proliferation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangapazham, R.L.; Sharad, S.; Maheshwari, R.K. Skin regenerative potentials of curcumin. Biofactors 2013, 39, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Harikumar, K.B. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.J.; Pandey, S. Chemo-resistant melanoma sensitized by tamoxifen to low dose curcumin treatment through induction of apoptosis and autophagy. Cancer Biol. 2011, 11, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Cusidó, R.M.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Moyano, E.; Palazón, J.; Bonfill, M. Production of the anticancer drug taxol in Taxus baccata suspension cultures: A review. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prota, A.E.; Bargsten, K.; Zurwerra, D.; Field, J.J.; Diaz, J.F.; Altmann, K.H.; Steinmetz, M.O. Molecular mechanism of action of microtubule-stabilizing anticancer agents. Science 2013, 339, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, A.; Yang, H.; Cabral, F. Paclitaxel-dependent cell lines reveal a novel drug activity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 2914–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, K.; Aparajitha, U.K. Paclitaxel against cancer: A short review. Med. Chem. 2012, 2, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cano, D.; Calvino, E.; Rubio, V.; Herraez, A.; Sancho, P.; Tejedor, M.C.; Diez, J.C. Apoptosis induced by paclitaxel via Bcl-2, Bax and caspases 3 and 9 activation in NB4 human leukaemia cells is not modulated by ERK inhibition. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013, 65, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Harsha, C.; Banik, K.; Vikkurthi, R.; Sailo, B.L.; Bordoloi, D.; Gupta, S.C.; Aggarwal, B.B. Is curcumin bioavailability a problem in humans: Lessons from clinical trials. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Wilke, D.V.; Jimenez, P.C.; Epifanio, R.d.A. Organismos marinhos como fonte de novos fármacos: Histórico & perspectivas. Química Nova 2009, 32, 703–716. [Google Scholar]

- La Clair, J.J. Natural product mode of action (MOA) studies: A link between natural and synthetic worlds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 969–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E.E. Natural products as chemical probes. Acs Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valli, M.; dos Santos, R.N.; Figueira, L.D.; Nakajima, C.H.; Castro-Gamboa, I.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Bolzani, V.S. Development of a natural products database from the biodiversity of Brazil. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragg, G.M.; Grothaus, P.G.; Newman, D.J. New horizons for old drugs and drug leads. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerwick, W.H.; Moore, B.S. Lessons from the past and charting the future of marine natural products drug discovery and chemical biology. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, R.; Luesch, H. Marine natural products: A new wave of drugs? Future Med. Chem. 2011, 3, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhoff, J.F.; Labes, A.; Wiese, J. Bio-mining the microbial treasures of the ocean: New natural products. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Latest global cancer data: Cancer burden rises to 18.1 million new cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018. Int. Agency Res. Cancer 2018, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.-H. An early history of human breast cancer: West meets East. Chin. J. Cancer 2013, 32, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, A. History of cancer, ancient and modern treatment methods. J. Cancer Sci. 2009, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K. Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771): Father of pathologic anatomy and pioneer of modern medicine. Anat. Sci. Int. 2017, 92, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J. John Hunter’s views on cancer. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1959, 25, 176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walter, E.; Scott, M. The life and work of Rudolf Virchow 1821–1902: “Cell theory, thrombosis and the sausage duel”. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2017, 18, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papac, R.J. Origins of cancer therapy. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2001, 74, 391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, S.H. Paul Ehrlich: Founder of chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVita, V.T.; Chu, E. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8643–8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avendaño, C.; Menendez, J.C. Medicinal chemistry of anticancer drugs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kinch, M.S. An analysis of FDA-approved drugs for oncology. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1831–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, L.G.; Ferreira, L.L.; Andricopulo, A.D. Recent advances and perspectives in cancer drug design. Da Acad. Bras. De Ciências 2018, 90, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.T. Food and Drug Administration drug approval process: a history and overview. Nurs. Clin. 2016, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishayee, A.; Sethi, G. Bioactive natural products in cancer prevention and therapy: Progress and promise. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016, 40–41, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, G.; Ryu, J. Cabazitaxel (jevtana): A novel agent for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 440. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.K.; Twardowski, P.; Sartor, O. Critical appraisal of cabazitaxel in the management of advanced prostate cancer. Clin. Interv. Aging 2010, 5, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hirata, Y.; Uemura, D. Halichondrins-antitumor polyether macrolides from a marine sponge. Pure Appl. Chem. 1986, 58, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towle, M.J.; Salvato, K.A.; Budrow, J.; Wels, B.F.; Kuznetsov, G.; Aalfs, K.K.; Welsh, S.; Zheng, W.; Seletsky, B.M.; Palme, M.H. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of synthetic macrocyclic ketone analogues of halichondrin B. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aicher, T.D.; Buszek, K.R.; Fang, F.G.; Forsyth, C.J.; Jung, S.H.; Kishi, Y.; Matelich, M.C.; Scola, P.M.; Spero, D.M.; Yoon, S.K. Total synthesis of halichondrin B and norhalichondrin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 3162–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Habgood, G.J.; Christ, W.J.; Kishi, Y.; Littlefield, B.A.; Melvin, J.Y. Structure–activity relationships of halichondrin B analogues: modifications at C. 30–C. 38. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 1029–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Paull, K.D.; Herald, C.L.; Malspeis, L.; Pettit, G.R.; Hamel, E. Halichondrin B and homohalichondrin B, marine natural products binding in the vinca domain of tubulin. Discovery of tubulin-based mechanism of action by analysis of differential cytotoxicity data. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15882–15889. [Google Scholar]

- Stamos, D.P.; Chen, S.S.; Kishi, Y. New Synthetic Route to the C. 14− C. 38 Segment of Halichondrins. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7552–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.A.; Kamath, K.; Manna, T.; Okouneva, T.; Miller, H.P.; Davis, C.; Littlefield, B.A.; Wilson, L. The primary antimitotic mechanism of action of the synthetic halichondrin E7389 is suppression of microtubule growth. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 2005, 4, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabydeen, D.A.; Burnett, J.C.; Bai, R.; Verdier-Pinard, P.; Hickford, S.J.; Pettit, G.R.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.; Gussio, R.; Hamel, E. Comparison of the activities of the truncated halichondrin B analog NSC 707389 (E7389) with those of the parent compound and a proposed binding site on tubulin. Mol. Pharm. 2006, 70, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alday, P.H.; Correia, J.J. Macromolecular interaction of halichondrin B analogues eribulin (E7389) and ER-076349 with tubulin by analytical ultracentrifugation. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7927–7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okouneva, T.; Azarenko, O.; Wilson, L.; Littlefield, B.A.; Jordan, M.A. Inhibition of centromere dynamics by eribulin (E7389) during mitotic metaphase. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, G.; Towle, M.J.; Cheng, H.; Kawamura, T.; TenDyke, K.; Liu, D.; Kishi, Y.; Melvin, J.Y.; Littlefield, B.A. Induction of morphological and biochemical apoptosis following prolonged mitotic blockage by halichondrin B macrocyclic ketone analog E7389. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5760–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, I.S.; Armstrong, J.G.; Gorman, M.; Burnett, J.P. The vinca alkaloids: A new class of oncolytic agents. Cancer Res. 1963, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, R.L. The discovery of the vinca alkaloids—chemotherapeutic agents against cancer. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1990, 68, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.; Beer, C.; Cutts, J. Role of chance observations in chemotherapy: Vinca rosea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1958, 76, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, J.A.; Deitcher, S.R. Marqibo® (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 2013, 71, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Li, L.; Fattah, F.J.; Dong, Y.; Bey, E.A.; Patel, M.; Gao, J.; Boothman, D.A. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. TM Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2014, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, Z.B.; Sood, A.K.; Coleman, R.L. Evaluation of rucaparib and companion diagnostics in the PARP inhibitor landscape for recurrent ovarian cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 1439–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, K.E. Advances in the use of PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer: Talazoparib. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2018, 23, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapche, D.W.; Lekane, N.M.; Kulabas, S.S.; Ipek, H.; Tok, T.T.; Ngadjui, B.T.; Demirtas, I.; Tumer, T.B. Aryl benzofuran derivatives from the stem bark of Calpocalyx dinklagei attenuate inflammation. Phytochemistry 2017, 141, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumer, T.B.; Yılmaz, B.; Ozleyen, A.; Kurt, B.; Tok, T.T.; Taskin, K.M.; Kulabas, S.S. GR24, a synthetic analog of Strigolactones, alleviates inflammation and promotes Nrf2 cytoprotective response: In vitro and in silico evidences. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018, 76, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crusz, S.M.; Balkwill, F.R. Inflammation and cancer: Advances and new agents. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulabas, S.; Ipek, H.; Tufekci, A.; Arslan, S.; Demirtas, I.; Ekren, R.; Sezerman, U.; Tumer, T. Ameliorative potential of Lavandula stoechas in metabolic syndrome via multitarget interactions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 223, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, A.R.; Lacy, M.Q. Pomalidomide and its clinical potential for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: An update for the hematologist. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2013, 4, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, F.; Skafi, M.; Recchia, A.G.; Kashkeesh, A.; Hindiyeh, M.; Sabatleen, A.; Morabito, L.; Alijanazreh, H.; Hamamreh, Y.; Gentile, M. Lenalidomide for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideshima, T.; Raje, N.; Richardson, P.G.; Anderson, K.C. A review of lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butti, R.; Das, S.; Gunasekaran, V.P.; Yadav, A.S.; Kumar, D.; Kundu, G.C. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in breast cancer: Signaling, therapeutic implications and challenges. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Lovly, C.M. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahovic, G.; Crawford, J. Activation of tyrosine kinases in cancer. Oncologist 2003, 8, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]