Abstract

Microplastics harbor chemical additives and absorb pollutants from the environment. Microplastics pose a human health threat and have been found in nearly all human tissues. The toxicological pathways and physiological effects of microplastic-mediated chemical exposure following ingestion remain unknown. Here we use Caenorhabditis elegans to investigate the effects of di-butyl phthalate and polystyrene microplastic mixtures on fertility and lifespan. Our studies demonstrate that 1 µm microplastics at 1 mg/L exposure levels result in decreased brood size, whereas 1000 times fewer microplastics (1 µg/L) did not affect the number of eggs laid. While there was no change in brood size at 1 µg/L microplastic exposure levels, there was an increase in embryonic lethality. Microplastics-mediated delivery of di-butyl phthalate to C. elegans significantly reduced brood size and increased embryonic lethality compared to exposure to microplastics alone. This reproductive toxicity is potentially due to a stress response via DAF-16, as observed with microplastics and di-butyl phthalate co-exposure. Furthermore, chronic exposure (from hatching onward) to microplastics shortened the lifespan of C. elegans, which was further reduced with di-butyl phthalate co-exposure. The exacerbated defects observed with co-exposure to phthalate-containing microplastics underscore the risks associated with microplastics releasing the additives and/or chemicals that they have absorbed from the environment.

1. Introduction

Plastic and chemical pollutants are ubiquitous in the environment, posing an emerging human health concern. Microplastic (MP) particles have been identified in nearly all human tissues, from blood [1] to the brain [2], and most recently in human reproductive organs [3,4]. MP exposure includes plastics from various environmental sources and exists in a wide range of chemical types, mixtures, and conditions. Primary MP particles are manufactured and used as ingredients in biomedical products and various health and beauty items (i.e., scrubs, make-up, cleansers, and toothpaste) [5], whereas secondary MPs result from the breakdown of larger plastic items. Human exposure to MPs occurs through direct use of MP-containing products, exposure to secondary MPs released into food, or environmental pollutants.

Both primary and secondary MPs undergo chemical and physical changes in their structure due to environmental exposure. Factors such as UV light, physical breakdown, and exposure to environmental pollutants can lead to alterations in the size, surface structure, and chemical composition of MPs. Despite efforts to reduce plastic use, it remains prevalent, with much already having entered the ecosystem [6]. Dating back to the 1950s, approximately 400 million tons of plastic waste accumulate each year [7]. MPs (MPs, plastic particles < 5 mm [8]) and nanoplastics (NPs, plastic particles ≤ 1 µm [8]) are detected in the air, water, and our food sources [9,10,11,12,13]. Meanwhile, MPs have been found in tissue exhibiting the ability to enter mammalian cells [14]. The smallest particles, NPs, invade endosomes, lysosomes, lymph and circulatory systems, and the lungs [15,16,17], leading to deleterious effects on the cellular level [16,17]. The direct health risks of human ingestion of MPs have not been quantified. Moreover, these risks amplify as plastics already contain additives, and they can absorb, accumulate, and transfer chemicals from the surrounding environment into organisms.

Plastic and resulting MP particles can be composed of homogenous or heterogeneous polymer mixtures, contain additives from the manufacturing process (plasticizers, by-products, and monomers), and may absorb chemical pollutants [18,19,20]. These additives and pollutants can later leach into the environment [21]. Persistent organic pollutants have been shown to be transferred from plastic particles to fish with adverse effects in environmentally relevant concentrations [22] and led to a transfer of chemicals from MPs into the guts of lung worms (Arenicola marina), and a reduction in biological functions [23]. In mice, it was demonstrated that phthalate esters were released from MPs leading to intestinal permeability and inflammation [24]. A study using Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) showed that 19 chemicals (including phthalates and agrochemicals) increased DNA damage and physiological dysregulation when compared to Bisphenol-A (BPA) [25]. BPA has been widely recognized as a threat to human health, and its use has been highly restricted, with a total ban on its use in infant-related products [26,27]. Due to these concerns, most manufacturers have voluntarily removed BPA from consumer products. With these regulations and demands from consumers, manufacturers must rely on other plasticizers to aid in the performance and functionality of plastic products.

Di-butyl phthalate (DBP), a widely used plasticizer, can compose 20–80% of some plastic products [20] and its use is regulated by both the United States and European agencies [28]. DBP is classified as a phthalate ester, which as a group, are considered endocrine-disrupting chemicals and pose cytotoxic and estrogenic effects [27,29,30,31]. DBP is most commonly used as a plasticizer, primarily in polyvinyl acetate emulsion adhesives, as a solvent for oil-based dyes, and insecticides [32]. It can be found in consumer products including nail polish, paints, adhesives, and perfume oils. Prior to 2008, many products for children contained high levels of DBP, butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP), and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP). The United States and European federal restrictions now limit the use of some phthalates, including DBP, in children’s products. Despite bans on some products, DBP and other phthalate esters are widely used in everyday household items or manufacturing processes. Many household products contain these chemical additives, which, when disposed of, will likely end up in municipal landfills [32]. Thus, DBP could leach into the environment due to improper disposal or the breakdown of products containing it. Once in the environment, DBP absorbs onto suspended particles and is less likely to degrade than dissolved DBP [32]. DBP has a high likelihood of being absorbed into MPs in the environment, as it is readily absorbed by plastic particles, possesses properties that make it highly adsorptive, and is chemically related to compounds that are readily absorbed into plastics [33].

Despite the risks of MP exposure to humans and the danger of plastic particles carrying chemical pollutants, MP and chemical co-exposure remain under-investigated. It is crucial to determine how MP–chemical mixtures alter the development and health of humans and other land animals. We use the C. elegans model system to examine the cellular and physiological effects of MP mixtures on whole-organism health and development. In this study, we investigate whether 1 µm polystyrene (PS) MPs can transport absorbed chemicals into an animal after ingestion and lead to physiological responses. We chose to work with two different MP doses (1 µg/L and 1 mg/L). These levels of exposure are within the range of other studies and mimic concentrations determined from human samples such as blood [1,34,35,36,37]. Polystyrene MP was chosen due to its common use in packing foams, food containers, and disposable cutlery, making it highly relevant to human oral MP exposure risks [20]. The additive DBP was chosen as a representative chemical due to its widespread use as an industrial additive. Studies of additives commonly found in plastics show that many plasticizers with relatively low molecular weight can transfer from plastic materials into foods [20]. We hypothesized that MPs can contain a chemical pollutant and mediate physiological defects that are greater than either pollutant alone. We find that MP exposure reduces brood size and leads to embryonic lethality in a concentration-dependent manner. The MP-mediated delivery further decreased reproduction compared to MPs or DBP alone. Reproductive defects due to MP-DBP co-exposure appear to cause stress via DAF-16 and reduce C. elegans lifespan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Microplastics

Polystyrene microplastics (Poly Sciences, 19518-500, Warrington, PA, USA) are purchased in a monodisperse form and contain a slight anionic charge from sulfate ester. PS MP size and surface were characterized by Scanning Electron Microscopy (JEOL JSM-6010 PLUS/LA, Peabody, MA, USA). Samples were sputter-coated with 2 nm gold particles prior to imaging (Quorum Technologies EMS150T ES, Lewes, UK). MP diameter was measured using the measuring tool in the JOEL InTouchScope software (Version 3.01).

2.2. Preparation of Microplastic and Chemical Mixtures

MPs were suspended in Escherichia coli (strain OP50, grown in LB broth), seeded on Nematode Growth Media (NGM) plates (Teknova, N1105, Hollister, CA, USA) and allowed to dry overnight before adding nematodes to the plates for exposure. To prepare MP E. coli suspensions, MPs were suspended in a 1% solution with M9 buffer, then diluted into E. coli OP50. At each dilution step, the solution was sonicated for 15 min (Emerson Branson 3800, Danbury, CT, USA). Wide-boar tips were used to transfer liquid. Dry 1 µM PS microspheres (Poly Sciences, 19518-500, Warrington, PA, USA) were used for all experiments unless otherwise noted. Di-butyl phthalate (DBP, Sigma, 524980, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was diluted into 100% DMSO (Sigma, D8418, Saint Louis, MO, USA) at 0.1 M concentration. Additional dilutions were made from the 0.1 M stock into water. DBP PS MP mixtures were prepared by adding DBP (either 0.1 M, 3.7 mM, or 100 µM concentration) to dry PS MPs, to create a 1% solution, which was incubated overnight, on a rotating rack, in the dark, at room temperature (19–22 °C). DMSO PS MP controls were prepared by adding 100% DMSO, 3.7% DMSO, or 0.0001% DMSO to dry PS MPs at 1%. PS MPs were diluted into E. coli OP50 to a final concentration of either 1 µg/L or 1 mg/L.

2.3. Maintenance of C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) strains, N2 (wild type) and TJ356 (zIs356 [daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]) that were used in this study were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genome Center. Worms were grown on Nematode Growth Media Agarose (NGM) plates seeded with E. coli OP50 at 20 °C.

2.4. Exposure Design

Bleach-synchronized L1 larvae were exposed to E. coli OP50 containing PS MPs at either 1 µg/L or 1 mg/L, or PS MPs soaked in DBP (100 µM, 3.7 mM or 0.1 M) or DMSO (0.1%, 3.7%, or 100%) for 24 h, or DBP or DMSO added directly to the OP50 E. coli alone on NGM plates made within 48 h. DBP and DMSO-only control concentrations were determined by the amount of solution carried into the final E. coli OP50 culture after dilution from the prepared 1% PS MPs. From a 1% PS MP in 0.1 M DBP solution that was diluted 1:10,000 into E. coli OP50 for a final concentration of 1 µg/L MP, would have an associated 10 µM DBP control in E. coli OP50. For short-term exposure, L1s were removed from PS MPs plates after 48 h, then maintained on prepared E. coli OP50 plates until the end points for experimental conditions. At least 2 biological replicates were performed for each assay.

2.5. Visualizing Microplastics in C. elegans

To visualize MP distribution and location, L1 bleach-synchronized worms were exposed to 1 µm internally dyed Dragon Green PS microspheres (Bangs Laboratories Inc., FS03F, Fishers, IN, USA). L1 synchronized larvae were exposed to E. coli OP50 with 1 µg/L or 1 mg/L Dragon Green MPs suspended in E. coli OP50, then seeded on NGM plates. Worms were paralyzed in levamisole on an agarose pad before imaging at each life stage.

2.6. Visualizing Nile Red in C. elegans

To assess if chemical compounds absorbed by MP beads could transfer into the worm’s body after ingesting the chemically soaked beads, we fed L1 synchronized C. elegans PS MP beads soaked in 1 mg/L Nile Red in methanol (Sigma Aldrich, 19123, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The beads were rocked for 1 h and left to dry overnight, before being suspended in a 1% solution in M9 buffer. The 1% M9 solutions were diluted to 1 µg/L or 1 mg/L in OP50 E. coli before seeding on NGM plates and leaving them to dry overnight.

2.7. Lifespan Assay

Lifespan assays were performed at 20 °C. Approximately 50 synchronized L1 larvae were placed on the corresponding treatment conditions for 48 h and then transferred to new plates containing the same treatment with 100 µM 5′-fluorodeoxyuridine. Worms were counted as dead or alive every day until the number of live worms reached zero.

2.8. Evaluation of Reproductive Toxicity

To assay the total number of eggs laid per worm and the percentage hatched, bleach-synchronized L1 larvae were seeded onto each condition. Then, 48 h after seeding, L4 larval worms were then singled out onto respective plates. The following day, L4 singling is repeated from the previous day’s plate, and both plates are kept. After 24 h, L1s and embryos are counted from the first day of singling, then repeated every day, counting the L4-free plate, until the worm stops laying (around 6–7 days).

2.9. Imaging and Microscopy

Fluorescent and bright-field images were all captured using an EVOS M5000 (Invitrogen, Bothell, WA, USA). For live imaging (Dragon-Green PS MP localization, Nile Red-soaked PS MPs transfer, and DAF-16::GFP localization), worms were transferred to an agarose pad on a slide and immobilized with levamisole. All image processing and analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.54).

2.10. Activation of Stress Response

To determine if MP and chemical exposure lead to stress activation, the strain TJ356, expressing DAF-16 fused to GFP was exposed to PS MPs alone, and with DBP or DMSO, and DBP and DMSO alone. L1 synchronized larvae were placed onto each condition and live imaged 72 h later. Live imaging was completed within 5 min of paralysis for each strain. Each nematode was classified by the localization of DAF-16::GFP expression (cytoplasmic, intermediate or nuclear) [38,39].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and figure design were performed with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software version 10, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were checked for normality between treatments and statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (MP diameter, brood size, PS MP exposure). A t-test (two-tailed) was performed to analyze control vs. Nile Red data. Experiments were all carried out with a minimum of 2–3 biological replicates (N) and the number of total worms (n) examined that are used in statistical analysis as described.

3. Results and Discussion

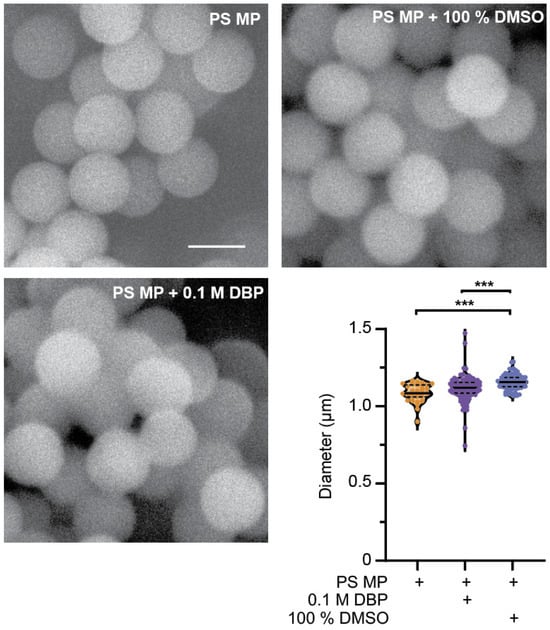

3.1. Polystyrene Microplastic Surface Structure Is Unchanged After Exposure to Di-butyl Phthalate

To verify the diameter and surface structure characteristics of PS microplastics (PS MP, hereon referred to as microplastics), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to image MPs with and without exposure for 24 h to 0.1 M di-butyl phthalate (DBP) or the solvent (DMSO). SEM analysis revealed no change to the surface morphology of MPs exposed to DBP for 24 h. A small but significant increase in the average size of MP particles occurred when soaked in DMSO, but not 0.1 M DBP (Figure 1, p ≤ 0.0001). It was anticipated that exposure to the plasticizer DBP may change the size or surface structure of MPs. Environmental exposure of MPs to heat, UV and mechanical stress can change their characteristics [19,40], and this was not observed after 24 h exposure of MPs to DBP or DMSO (Figure 1). DBP has high rates of sorption into MPs, with the highest rates seen in PS MP when compared to polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyethylene (PE) [33]. Sorption of compounds on or into MPs is size dependent, with smaller particles containing more readily available chemicals, due to the increase in surface to size ratio that occurs with the reduced particle size [19,41,42]. MP and DBP mixtures were prepared by soaking MPs in DBP for 24 h, followed by dilution into C. elegans food, E. coli OP50 (in LB). At each dilution step, MPs were sonicated to facilitate resuspension. The sonication process and the addition of MPs, DBP, and DMSO alone or in combination with MPs did not affect the viability of E. coli (Figure S1). Additionally, sonication would disrupt any adsorbed DBP on the MP surface, and thus any DBP present in the MP is assumed to be absorbed within the MP particles. The slightly larger, but non-significant, increase in the mean size of the 0.1 M DBP-soaked MPs, and the significantly larger diameter of MPs after DMSO exposure, may be due to swelling of the MP particles after absorption.

Figure 1.

Characterization of polystyrene (PS) microplastics (MP) before and after 24 h exposure to di-butyl phthalate (DBP) and DMSO. Representative SEM images of 1 µm PS MPs to verify their size and surface structure before and after exposure to 0.1 M DBP and 100% DMSO. Scale bar is 1 µm. Quantification of PS MP size before and after 24 h exposure to 0.1 M DBP and 100% DMSO. n = 31, 104, 81, *** p ≤ 0.0001.

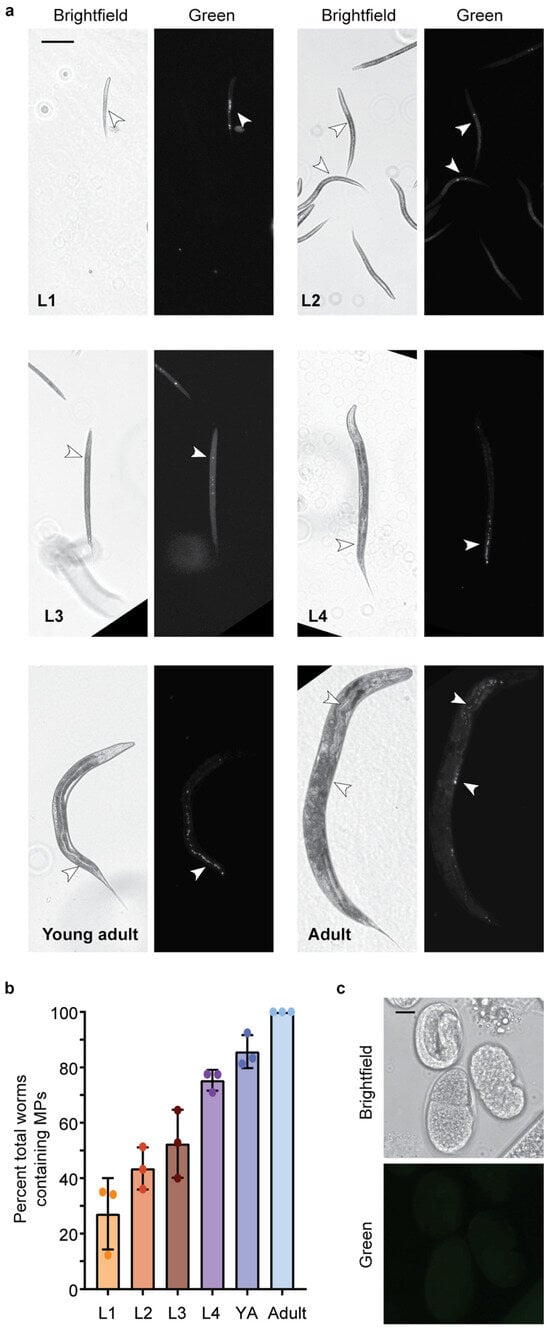

3.2. Polystyrene Microplastics Are Ingested by C. elegans and Act as a Vehicle for Chemical Exposure

C. elegans exposed to 1 µg/L and 1 mg/L MP show the presence of MPs in their gut tube (Figure 2a and Figure S2). Nematodes were initially exposed to two doses (1 µg/L and 1 mg/L), within the range of other studies and mimicking concentrations determined in human samples, such as blood [1,34,35,36,37]. MPs were present at all larval life stages, and the percentage of total worms containing MPs increased with life stage and exposure time. By adulthood, nearly all worms contained MPs (Figure 2b). These results are consistent with other studies demonstrating that MPs (>1 µm) accumulate in the gut, while smaller NP (<1 µm) particles can cross cell membranes [14,36,43,44,45]. Smaller MPs, less than 1 µm in size, in the nanometer range, have been observed to cross into the body cavity in C. elegans [43]. However, when examining the eggs of adult nematodes exposed to Dragon-Green MP, no MPs were observed (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

1 µm Dragon Green Polystyrene (PS) Microplastics (MPs) are ingested by C. elegans. MPs are ingested by C. elegans at all larval stages. (a) Representative images of C. elegans at life stages, L1–Adult after continuous exposure to 1 µg/L Dragon Green 1 µm PS MP particles. Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Quantification of the number of worms containing MPs at each larval stage (L1–Adult). YA, young adult. N = 3, n = 173, 247, 199, 111, 111, 105. (c) Representative image of C. elegans eggs from an adult worm that was continuously exposed to Dragon Green PS MPs. Scale bar = 10 µm.

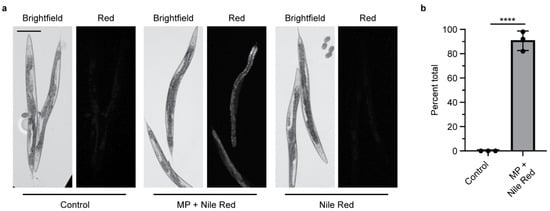

MPs contain chemical additives or may absorb pollutants in the environment that can then be transferred into living organisms, leading to physiological effects [20,33]. Phthalates, including DBP, are classified as endocrine disruptors that can be long-lived in the environment [20,41]. DBP is most commonly used as a plasticizer in PVC, followed by polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [20]. While DBP is not commonly used in PS products, we chose to study it as a potential environmental chemical that could be absorbed in MPs and transferred into an organism after ingestion. To visualize this, we soaked PS MPs in the lipophilic dye Nile Red to determine whether MPs could mediate the delivery of a chemical into an organism. Nematodes exposed to Nile Red-soaked MPs do not show puncta, which indicate the location of each MP, but rather show diffuse staining in the worm (Figure 3a and Figure S3). This indicates that the Nile Red dye absorbed by the PS MP, transfers into the worm’s body after ingestion. This transfer is present in more than 90% of the worms examined (Figure 3b). When nematodes are exposed to an equivalent amount of Nile Red without MPs, the Nile Red is not present in the worm’s body. Thus, the MPs mediate the delivery of Nile Red, which is then absorbed. This mimics what one would expect if MPs can act as a vector to deliver chemicals into an organism after ingestion.

Figure 3.

Microplastics soaked in Nile Red act as a carrier to deliver Nile Red into C. elegans after ingestion. (a) Representative images of adult C. elegans fed E. coli OP50 with and without Nile Red-stained microplastics (MPs). Control = E. coli OP50 only. Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Quantification of the presence of Nile Red inside C. elegans after ingestion of Nile Red-stained MPs, N = 3, n = 50, 50, 30. **** p < 0.00001.

3.3. Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics and Polystyrene Microplastic DBP Mixtures Results in Reproductive Toxicity

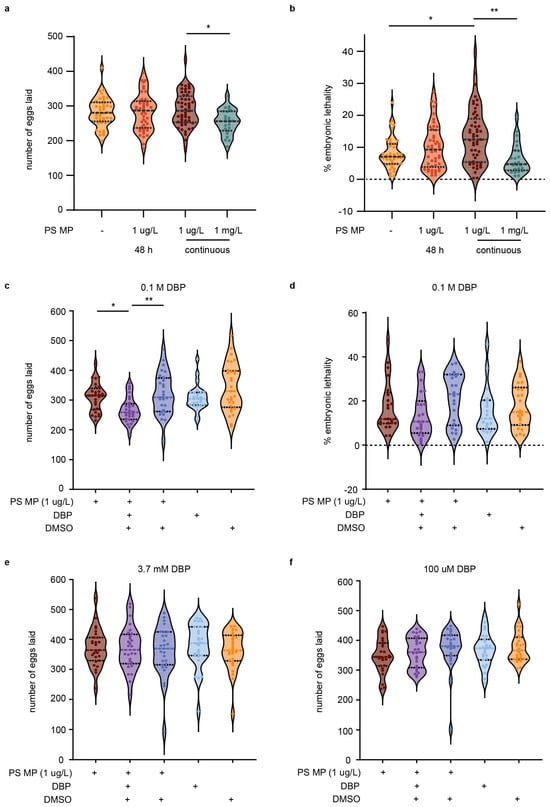

To determine if MPs and chemical pollutants cause reproductive toxicity, C. elegans were exposed to different concentrations of MPs and DBP for varying times. When L1 life stage, nematodes were exposed to 1 µm MP (at 1 µg/L concentration) for 48 h, until the young adult stage, or continuously, there was no observed significance in decreased total eggs laid or hatched (Figure 4a and Figure S4a). Despite no change to the number of eggs laid, chronic MP exposure to nematodes significantly increased embryonic lethality (p = 0.04) and the total number of eggs unhatched per nematode (p = 0.007) (Figure 4b and Figure S4b). Embryonic lethality is determined by taking the total number of eggs that are unhatched and dividing by the total number of eggs laid per worm. These results are within the range of other studies that observed continuous MPs of the same or smaller size, leading to minimal or no change in brood size and no embryonic lethality [45]. While some studies reported a decrease in brood size with exposure to MPs, this difference may be due to differences in MP size or composition or to varying exposure conditions [46]. When we exposed C. elegans to a 1000-fold higher concentration of MPs (1 mg/L), we observed a significant reduction in the total number of eggs laid (p = 0.016); however, this did not lead to an increase in embryonic lethality (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

Total eggs laid, number of fertilized and unfertilized eggs, and embryonic lethality of C. elegans exposed to polystyrene (PS) microplastics (MP) and/or containing DBP. (a) Number of eggs laid per nematode with E. coli OP50 only, 48 h exposure to PS MP or continuous PS MP exposure. N = 8, n = 43, 46, 52. (b) Percent embryonic lethality. (c) Total number of eggs with exposure to continuous PS MP with and without 0.1 M DBP. N = 4, n = 28, 28, 28, 25, 29. (d) Percent embryonic lethality. (e) Total number of eggs with exposure to continuous PS MP with and without 3.7 mM DBP. N = 4, n = 27, 28, 27, 28, 28. (f) Total number of eggs with exposure to continuous PS MP with and without 100 µM DBP. N = 3, n = 27, 27, 25, 27, 26. Violin plots show the mean with the standard deviation. Kruskal–Wallis was used for statistical analysis, using Dunn’s as a post hoc test (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01).

C. elegans exposure to MPs (1 µg/L) harboring 0.1 M DBP further reduced the number of eggs laid per worm compared to exposure to MPs alone (p = 0.017, Figure 4c). This combined exposure did not increase embryonic lethality (Figure 4d). Examination of MPs loaded with either 100 µM or 3.7 mM DBP did not affect brood size, egg hatching, or embryonic lethality (Figure 4e,f and Figure S5a–f). Typical concentrations of DBP used as a plasticizer can range from 10–35%, or higher in some products [20]. Our study employed 0.1 M DBP, a concentration equivalent to less than 10% w/w, which is in the range of DBP found in everyday products [20]. While 0.1 M DBP caused defects in fertility, these were not observed at lower concentrations (100 µM and 3.7 mM). Comparable levels of chemical pollutants could reach organisms through the ingestion of MPs that have absorbed chemicals from the environment or by the leaching of additives from MPs that initially contained higher chemical amounts. In particular, it is worth noting that recycled plastics can contain additives from recycled feedstocks [47].

Impaired reproduction with exposure to MPs alone or in combination with DBP could be caused by various factors. DBP is an endocrine-disrupting chemical and leads to cryptogenic effects [31]. Exposure to DBP leads to defects in reproduction and development [28]. Specifically, DBP exposure reduced human sperm function and in rodent studies defects occur in both development and reproduction [48,49,50,51]. In C. elegans, exposure to 100 µM DBP, in the absence of MP, led to increased embryonic lethality and DNA damage [25]. C. elegans exposure to DBP alone, at a lower dose (500 µM) than used in this study, leads to a reduction in the number of eggs laid and increased embryonic lethality [25].

These defects were attributed to defects in early embryogenesis, with elevated levels of DNA double-strand breaks, activation of a DNA damage checkpoint, and impaired embryogenesis [25]. Errors in cell division could reduce the ability of eggs to hatch and could be caused by a multitude of sources [52]. In humans and other organisms, these errors may lead to aneuploidy, spontaneous abortions, and birth defects [25,52,53]. Additionally, a reduction in the total number of eggs laid could be attributed to a nutrient deficiency of the parent caused by intestinal damage from PS MP exposure [46,54,55,56,57]. Another study suggested that the associated defects with PS MP exposure could be due to a reduction in ATP levels and a reduced energy budget toward reproduction [58].

The exacerbated defects we observed with co-exposure to MPs containing 0.1 M DBP demonstrate that MPs can mediate the delivery of a chemical into an organism after ingestion. This MP-mediated delivery of DBP underscores the risks of co-exposure when MPs can release the additives they already contain and/or chemicals that they have absorbed from the environment.

3.4. Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics and Polystyrene Microplastic DBP Mixtures Elicits a Stress Response

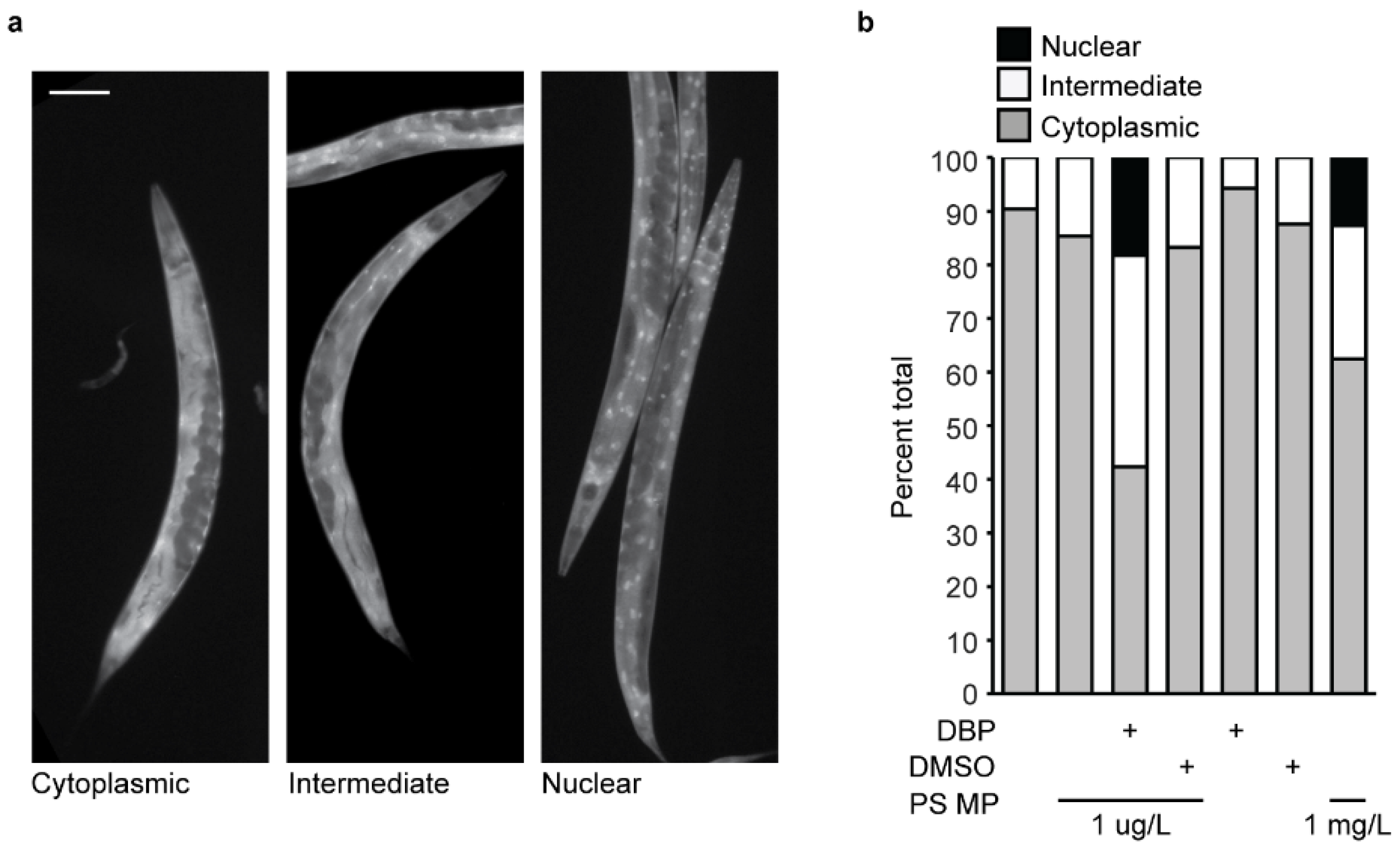

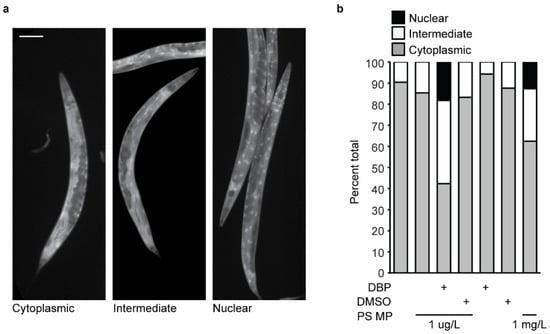

A possible mechanism of PS MP toxicity resulting in a reduction in fertility is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). PS MP exposure leads to higher levels of reactive oxygen species [15,35,54] and increased expression of GST-4 (glutathione S-transferase 4, an enzyme that is involved in clearing ROS) in nematodes [45,56]. Additionally, DBP and other phthalate esters cause DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities [25,53] that can be caused by ROS generation [51]. In response to stress, C. elegans activate a DAF-16 stress response that leads to the activation of genes encoding proteins involved in response to oxidative stress [59]. Therefore, to investigate if stress may be an underlying mechanism of reduced fertility, we asked if MP-mediated DBP exposure in C. elegans would initiate a DAF-16 stress response. The C. elegans strain TJ356 contains a reporter GFP fused to DAF-16 that is driven by the daf-16 promoter [60]. This GFP reporter is cytoplasmic under normal conditions and relocates to the nucleus to activate genes involved in an anti-oxidative response, under stress. Therefore, the localization of this DAF-16 GFP reporter can be used as a readout of a DAF-16-mediated stress response [35,38,45].

Under control conditions, when C. elegans were not exposed to MPs, majority of the worms examined had cytoplasmic DAF-16 localization (Figure 5a,b). Some worms showed an intermediate localization where less than 30% of the nuclei showed nuclear expression. This same expression pattern is present with C. elegans exposure to 1 µg/L MPs (Figure 5b). These results are consistent with what others see with similar PS MP exposure [45]. In contrast, MP-mediated DBP exposure led to a significant activation of the DAF-16 stress response, with 40% of the total worms showing an intermediate expression pattern and nearly 20% nuclear localization (Figure 5b). This indicates that the DAF-16 transcription factor is located in the nucleus, where it will activate genes in response to oxidative stress. Importantly, exposure to MPs containing DMSO, the solvent for DBP, or an equivalent amount of DBP or DMSO alone did not affect DAF-16 localization (Figure 5b). Expression of DAF-16 in these controls showed no significant change compared with the negative control (E. coli OP50 only) or MP exposure alone (Figure 5b). In our initial reproductive toxicity studies, we observed that higher concentrations of MPs (1 mg/L) induced a reduction in total eggs laid with no effect on embryonic lethality (Figure 4a,b). Therefore, we asked if MPs alone, at a higher concentration, would elicit a stress response via DAF-16. Continuous exposure of C. elegans to 1 mg/L MPs increased the percentage of worms with intermediate and nuclear expression of DAF-16 (Figure 5b). This indicates that the concentration of MP exposure can mitigate the effect. In contrast to our results, Leon et al. observed a stress response with C. elegans exposure to 100 nm PS MPs at a concentration of 10 mg/L [45]. This may be due to differences in the size of the tested plastic particles. The stress response observed in Leon et al. was with MPs of the same composition, PS, but with a smaller diameter (100 nm) and at 10,000-fold greater concentration than in this study. Indeed, we observed that 1 μm MPs at our higher, 1 mg/L, concentration elicited a DAF-16 stress response. This indicates that a stress response via DAF-16 may be concentration-dependent. While we did not see a DAF-16-mediated stress response with our primary level of MP exposure (1 µM/L) alone, a significant response was elicited when DBP delivery was mediated with this same concentration of MPs. Interestingly, Leon et al. observed that with the removal of worms from MP exposure, the MPs left the worm’s body, and the DAF-16 stress response reduced [45]. We did not test for the effect of DAF-16 localization with the removal of MP exposure from C. elegans, but it would be interesting to ask if the MP-mediated DBP stress response via DAF-16 would be maintained, as the MPs might clear the worm body, while the DBP is absorbed.

Figure 5.

Stress response via DAF-16 in C. elegans after exposure to polystyrene (PS) microplastic (MPs) and DBP. (a) Representative images of DAF-16-GFP expression in adult C. elegans, showing cytoplasmic (left), intermediary (center), and nuclear localization (right). Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Quantification of DAF-16-GFP localization in C. elegans with exposure to their regular E. coli diet only, with 1 µg/L PS MP, 1 µg/L PS MP and DBP, 1 µg/L PS MP and DMSO (vehicle control), DBP alone, and DMSO alone. N = 2, n = 53, 65, 170, 149, 140, 129, 43.

3.5. Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics and Microplastic DBP Mixtures Reduces Lifespan

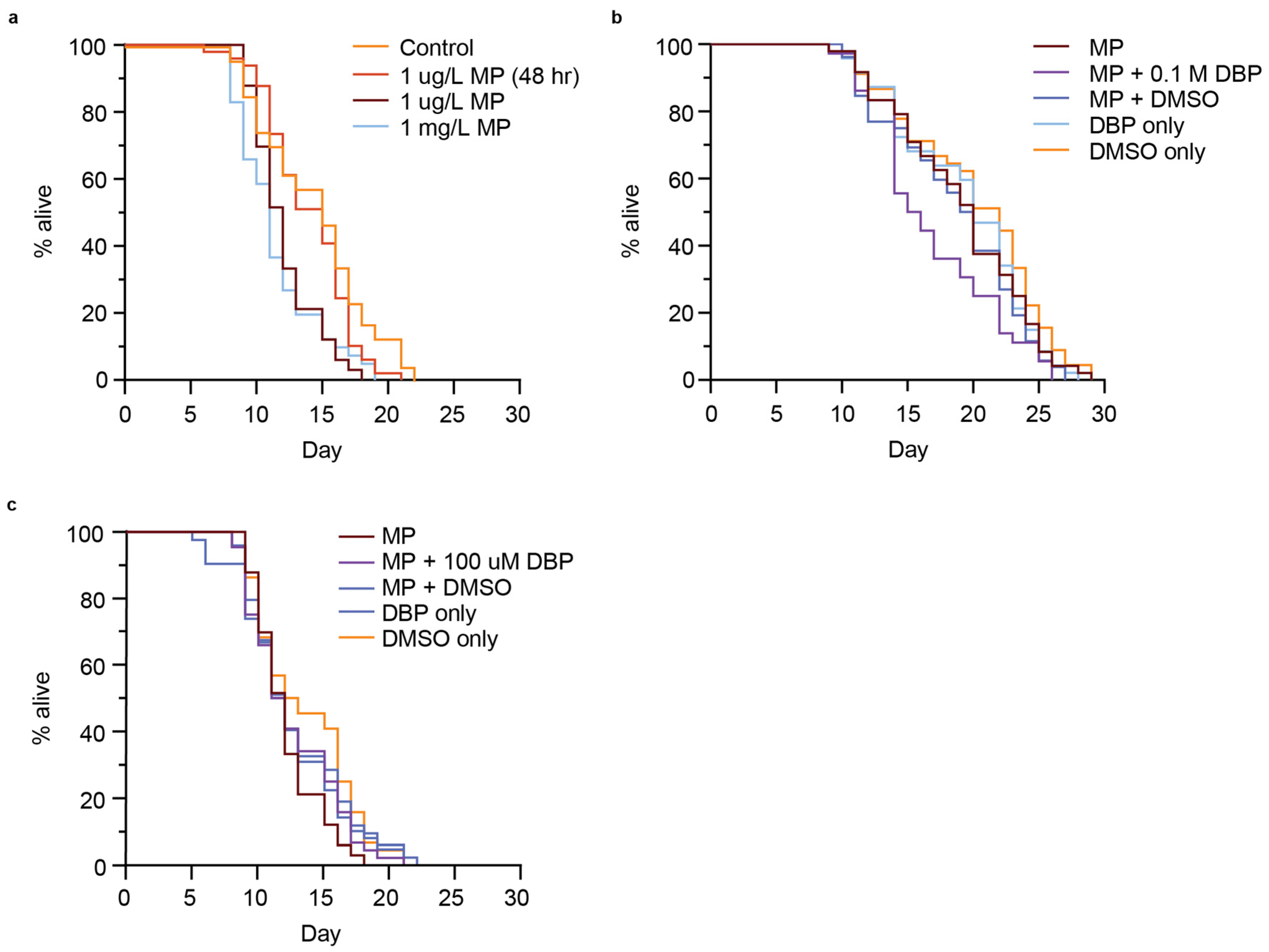

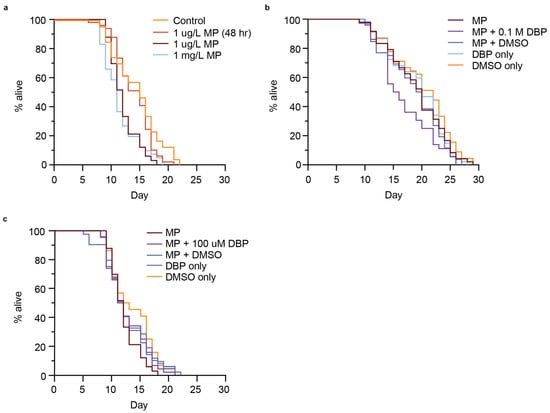

In some cases, the activation of a DAF-16 stress response is associated with an extended lifespan [39,59,61,62], and this response can be tissue-specific, with greater extension of lifespan associated with intestinal-specific DAF-16 activation [63]. Increased longevity induced by stress events is associated with the insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) receptor signaling pathway, or diet, amongst other pathways [62]. In particular, due to the presence of MP accumulation in the gut of the worm (Figure 2a), and studies indicating intestine-specific stress due to MP exposure [57], we wondered if the presence of MPs may reduce nutrient intake and increase lifespan. We next addressed whether MPs or MP-mediated DBP exposure would alter C. elegans lifespan. Short-term exposure (48 h) of C. elegans to 1 µm MP (1 µg/L) did not change the lifespan of animals compared to the control (Figure 6a). Interestingly, when nematodes were exposed to the same conditions, but without removal after 48 h, there was a significant reduction in lifespan (p < 0.0001) (Figure 6a and Figure S6a,b). This reduction in lifespan was equal to what was observed with continuous exposure to 1000-fold higher concentrated MPs (1 mg/L) (Figure 6a). The lifespan of animals was further reduced when exposed to MPs that mediated the delivery of 0.1 M DBP (p = 0.00357) (Figure 6b and Figure S6c). This reduction in lifespan was not observed under the control conditions of MPs containing DMSO, or with exposure to DBP or DMSO alone (Figure 6b and Figure S6c). Additionally, the reduction in lifespan with MP-mediated DBP exposure appears to be dependent on the concentration of DBP, at the lowest concentration used in this study (100 µM), did not further reduce lifespan compared to MP exposure alone (Figure 6c and Figure S6c). There are conflicting studies on the effect of MP exposure on C. elegans lifespan. In one study, PS MPs initiated a DAF-16 stress response that was not associated with a change in lifespan in C. elegans, and this was speculated to be due to a counteracting mechanism [45]. Other reports were consistent with our results, showing reduced lifespan with exposure to PS MPs [35]. Furthermore, our work shows that MP-mediated delivery of DBP further reduced lifespan. Additional reports examined the effects of leachates from plastic [64], phthalates [65,66], and other types of MP exposure on lifespan, all leading to reduced longevity.

Figure 6.

Lifespan of C. elegans exposed to polystyrene (PS) microplastic (MPs) containing different concentrations of MPs or MPs that had been soaked in different concentrations of DBP (0.1 M or 100 µM). (a) Survival assay for nematodes exposed to control (no MPs), 1 µg/L PS-MPs for 48 h, 1 µg/L or 1 mg/L PS-MPs continuously. n = 47, 49, 33, 41. p < 0.0001. (b) Survival assay for N2 nematodes continuously exposed to 1 µg/L PS MPs, with and without being soaked in 0.1 M DBP or vehicle alone (100% DMSO) for 24 h. n = 48, 36, 52, 47, 45. p = 0.00357. (c) Survival assay for N2 nematodes continuously exposed to 1 µg/L PS-MPs, with and without being soaked in 100 µM DBP or vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) for 24 h. n = 33, 44, 42, 49, 44. Not significant, p = 0.4. Log-rank (Mantel–Cox).

This work demonstrates that MP-mediated delivery of plastic-containing compounds, such as DBP, enhances the physiological defects observed with MP exposure alone. The exposure level of MPs, the time of exposure, and the concentration of the absorbed chemicals influence the defects observed. This provides evidence that C. elegans, like other model organisms, can serve to assess the risk associated with microplastic-facilitated exposure to chemical compounds [67,68]. There is a need for whole-animal model organism systems to systematically interrogate the synergistic effects of co-exposure to microplastics and other chemical compounds (e.g., chemical additives, environmental toxins, metals, antibiotics, etc.). Systematic, rigorous whole-animal model studies will make it possible to understand long-term and multigenerational effects of these pollutants.

Overall, our results show that chronic MP exposure has detrimental effects on reproduction and reduces lifespan. Specifically, we demonstrate that co-exposure of MPs and DBP exacerbates the defects observed. MPs mediate DBP delivery in C. elegans, further decreasing fertility and lifespan and triggering a stress response via DAF-16 activation. Further studies are needed to identify other mechanisms underlying the toxicity associated with MP-mediated exposure to DBP. The worsened physiological defects seen with co-exposure to phthalate-containing MPs shows that MPs can leach contents into an organism after ingestion. This highlights the risks of MPs releasing the additives they already contain and/or chemicals that they have absorbed from the environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microplastics4040096/s1. Figure S1: Viability of E. coli OP50 when sonicated, or with the addition of MPs, DBP, DMSO alone, or in combination; Figure S2: Schematic of the experiments to visualize microplastics (MPs) in C. elegans; Figure S3: Schematic of reproductive and physiological stress assays using various C. elegans strains; Figure S4: Number of eggs hatched and unhatched in C. elegans exposed to 48 h or continuous polystyrene (PS) microplastics (MPs) with and without DBP; Figure S5: Number of eggs hatched, unhatched eggs, and embryonic lethality of C. elegans exposed to polystyrene (PS) microplastic (MP) that had been soaked in different concentrations of DBP; Figure S6: Lifespan of C. elegans exposed to polystyrene (PS) microplastic (MP) and 0.1 M DBP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.H.; methodology, J.C.H., C.A.O.M., P.C.G., M.R.F., A.D.F. and R.L.P.; validation, J.C.H. and R.L.P.; formal analysis, J.C.H., C.A.O.M., P.C.G., A.D.F. and R.L.P.; investigation, J.C.H., C.A.O.M., D.M.M., P.C.G., M.F.G., M.R.F., A.D.F. and R.L.P.; resources, J.C.H.; data curation, J.C.H., C.A.O.M. and D.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.H. and C.A.O.M.; writing—review and editing, J.C.H.; visualization, J.C.H. and C.A.O.M.; supervision, J.C.H.; project administration, J.C.H.; funding acquisition, J.C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS (R16GM150406). C. Maldonado, P. Garcia, and M. Flores were funded by NIH grants (T34GM008073 and T34GM149455). A. Friudenberg was funded by an NIH grant (R25GM102783).

Institutional Review Board Statement

C. elegans are not vertebrates and thus, by the National Institute of Health (NIH) guidelines, the vertebrate animal guidelines do not apply.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Culotta for valuable discussions and advice on the development and design of experiments. Many undergraduate student researchers have played a part in moving this project forward, and we thank them for their time and valuable input. We also thank St. Mary’s University for its continued support, including funds from the Department of Biological Sciences, the Benjamin F. Biaggini Endowment, and San Antonio Area Foundation. C. elegans strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MP | Microplastic |

| NP | Nanoplastic |

| C. elegans | Caenorhabditis elegans |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| DBP | Dibutyl phthalate |

| BBP | Butyl benzyl phthalate |

| DEHP | Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| NGM | Nematode Growth Media Agarose |

| L1 | Larval stage 1 |

| L2 | Larval stage 2 |

| L3 | Larval stage 3 |

| L4 | Larval stage 4 |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| YA | Young adult |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| GST-4 | Glutathione S-transferase 4 |

| DAF-16 | Forkhead box O (FOXO) protein |

| IGF-1 | Insulin/insulin-like growth factor |

References

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihart, A.J.; Garcia, M.A.; El Hayek, E.; Liu, R.; Olewine, M.; Kingston, J.D.; Castillo, E.F.; Gullapalli, R.R.; Howard, T.; Bleske, B.; et al. Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.J.; Garcia, M.A.; Nihart, A.; Liu, R.; Yin, L.; Adolphi, N.; Gallego, D.F.; Kang, H.; Campen, M.J.; Yu, X. Microplastic presence in dog and human testis and its potential association with sperm count and weights of testis and epididymis. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 200, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, L.; Raimondo, S.; Piscopo, M.; Ricciardi, M.; Guglielmino, A.; Chamayou, S.; Gentile, R.; Gentile, M.; Rapisarda, P.; Oliveri Conti, G.; et al. First evidence of microplastics in human ovarian follicular fluid: An emerging threat to female fertility. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 291, 117868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GESAMP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Part 2 of a Global Assessment; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2016; Volume 93, p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, J.; Deeney, M.; Muncke, J.; Carney Almroth, B.; Dignac, M.F.; Castillo, A.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Kadiyala, S.; Kumar, E.; Stoett, P.; et al. Plastics matter in the food system. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danopoulos, E.; Twiddy, M.; Rotchell, J.M. Microplastic contamination of drinking water: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Torre, G.E. Microplastics: An emerging threat to food security and human health. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 57, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N.; Gao, X.; Lang, X.; Deng, H.; Bratu, T.M.; Chen, Q.; Stapleton, P.; Yan, B.; Min, W. Rapid single-particle chemical imaging of nanoplastics by SRS microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2300582121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.; Deeney, M.; Rolker, H.B.; White, H.; Kalamatianou, S.; Kadiyala, S. A systematic scoping review of environmental, food security and health impacts of food system plastics. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shi, G.; Revell, L.E.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, C.; Wang, D.; Le Ru, E.C.; Wu, G.; Mitrano, D.M. Long-range atmospheric transport of microplastics across the southern hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of Nanoplastic in the Environment and Possible Impact on Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Jaitley, V.; Florence, A.T. Recent advances in the understanding of uptake of microparticulates across the gastrointestinal lymphatics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 50, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, P.; Park, C.Y.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Tsuda, A.; Sager, T.M.; Molina, R.M.; Donaghey, T.C.; Alencar, A.M.; Kasahara, D.I.; Ericsson, T.; et al. Biomechanical effects of environmental and engineered particles on human airway smooth muscle cells. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, S331–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E.; Samberger, C.; Kueznik, T.; Absenger, M.; Roblegg, E.; Zimmer, A.; Pieber, T.R. Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles independent from oxidative stress. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 34, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teuten, E.L.; Saquing, J.M.; Knappe, D.R.; Barlaz, M.A.; Jonsson, S.; Bjorn, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Yamashita, R.; et al. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2027–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijagic, A.; Suljevic, D.; Focak, M.; Sulejmanovic, J.; Sehovic, E.; Särndahl, E.; Engwall, M. The triple exposure nexus of microplastic particles, plastic-associated chemicals, and environmental pollutants from a human health perspective. Environ. Int. 2024, 188, 108736. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Kumar, M.; Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Bolan, N.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Hou, D.; Li, Y. Various additive release from microplastics and their toxicity in aquatic environments. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochman, C.M.; Hoh, E.; Kurobe, T.; Teh, S.J. Ingested plastic transfers hazardous chemicals to fish and induces hepatic stress. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Niven, S.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastic moves pollutants and additives to worms, reducing functions linked to health and biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2388–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yan, Z.; Shen, R.; Wang, M.; Huang, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lemos, B. Microplastics release phthalate esters and cause aggravated adverse effects in the mouse gut. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.; Cuenca, L.; Karthikraj, R.; Kannan, K.; Colaiacovo, M.P. Assessing effects of germline exposure to environmental toxicants by high-throughput screening in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Bisphenol A (BPA). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-packaging-other-substances-come-contact-food-information-consumers/bisphenol-bpa (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Rochester, J.R. Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the literature. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, M.; Fasano, M.; Palandri, L.; Righi, E. A review of European and international phthalates regulation: Focus on daily use products. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, ckac131.226. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, J.S.; Yin, L.; Measel, E.; Liang, S.; Yu, X. Effects of bisphenol A and its analogs on reproductive health: A mini review. Reprod. Toxicol. 2018, 79, 96–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicinska, P.; Mokra, K.; Wozniak, K.; Michalowicz, J.; Bukowska, B. Genotoxic risk assessment and mechanism of DNA damage induced by phthalates and their metabolites in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankidy, R.; Wiseman, S.; Ma, H.; Giesy, J.P. Biological impact of phthalates. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 217, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toxicological Profile for Di-N-butyl Phthalate; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2001; p. 225.

- Liu, F.-f.; Liu, G.-z.; Zhu, Z.-l.; Wang, S.-c.; Zhao, F.-f. Interactions between microplastics and phthalate esters as affected by microplastics characteristics and solution chemistry. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, R.; Enders, K.; Nielsen, T.G. Microplastic exposure studies should be environmentally realistic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4121–E4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, D. Effect of chronic exposure to nanopolystyrene on nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Felix, R.C.; Canario, A.V.M.; Power, D.M. The physiological effect of polystyrene nanoplastic particles on fish and human fibroblasts. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, P.; Cai, M.; Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Chen, M.; Zhao, Y. Effects of microplastics on the innate immunity and intestinal microflora of juvenile Eriocheir sinensis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, T.; Antunes Soares, F.A.; Santamaria, A.; Bowman, A.B.; Skalny, A.V.; Aschner, M. N,N′ bis-(2-mercaptoethyl) isophthalamide induces developmental delay in Caenorhabditis elegans by promoting DAF-16 nuclear localization. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, N.R.; de Araujo, L.C.A.; Dos Santos da Rocha, P.; Agarrayua, D.A.; Avila, D.S.; Carollo, C.A.; Silva, D.B.; Estevinho, L.M.; de Picoli Souza, K.; Dos Santos, E.L. Baru Pulp (Dipteryx alata Vogel): Fruit from the Brazilian Savanna Protects against Oxidative Stress and Increases the Life Expectancy of Caenorhabditis elegans via SOD-3 and DAF-16. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Barnes, P.W.; Bornman, J.F.; Gouin, T.; Madronich, S.; White, C.C.; Zepp, R.G.; Jansen, M.A.K. Oxidation and fragmentation of plastics in a changing environment; from UV-radiation to biological degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Gu, C. Dibutyl phthalate release from polyvinyl chloride microplastics: Influence of plastic properties and environmental factors. Water Res. 2021, 204, 117597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, S.; He, C. Effect of particle size and environmental conditions on the release of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from microplastics. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, A.; Park, S.J.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, K.W. Nanoplastics exacerbate Parkinson’s disease symptoms in C. elegans and human cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, M.T.; Fueser, H.; Trac, L.N.; Mayer, P.; Traunspurger, W.; Hoss, S. Surface-Related Toxicity of Polystyrene Beads to Nematodes and the Role of Food Availability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1790–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errazuriz Leon, R.; Araya Salcedo, V.A.; Novoa San Miguel, F.J.; Llanquinao Tardio, C.R.A.; Tobar Briceno, A.A.; Cherubini Fouilloux, S.F.; de Matos Barbosa, M.; Saldias Barros, C.A.; Waldman, W.R.; Espinosa-Bustos, C.; et al. Photoaged polystyrene nanoplastics exposure results in reproductive toxicity due to oxidative damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wu, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Fu, Z.; Shi, H.; Raley-Susman, K.M.; He, D. Microplastic particles cause intestinal damage and other adverse effects in zebrafish Danio rerio and nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivnenko, K.; Eriksen, M.K.; Martin-Fernandez, J.A.; Eriksson, E.; Astrup, T.F. Recycling of plastic waste: Presence of phthalates in plastics from households and industry. Waste Manag. 2016, 54, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.E., Jr.; Laskey, J.; Ostby, J. Chronic di-n-butyl phthalate exposure in rats reduces fertility and alters ovarian function during pregnancy in female Long Evans hooded rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 93, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.; Liu, X.; Craig, Z.R. Short term exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) disrupts ovarian function in young CD-1 mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 53, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Ohsako, S.; Matsuwaki, T.; Zhu, X.B.; Tsunekawa, N.; Kanai, Y.; Sone, H.; Tohyama, C.; Kurohmaru, M. Induction of spermatogenic cell apoptosis in prepubertal rat testes irrespective of testicular steroidogenesis: A possible estrogenic effect of di(n-butyl) phthalate. Reproduction 2010, 139, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okayama, Y.; Wakui, S.; Wempe, M.F.; Sugiyama, M.; Motohashi, M.; Mutou, T.; Takahashi, H.; Kume, E.; Ikegami, H. In Utero Exposure to Di(n-butyl)phthalate Induces Morphological and Biochemical Changes in Rats Postpuberty. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 45, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.; Ellenberg, J. Mysteries in embryonic development: How can errors arise so frequently at the beginning of mammalian life? PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornos Carneiro, M.F.; Shin, N.; Karthikraj, R.; Barbosa, F., Jr.; Kannan, K.; Colaiacovo, M.P. Antioxidant CoQ10 Restores Fertility by Rescuing Bisphenol A-Induced Oxidative DNA Damage in the Caenorhabditis elegans Germline. Genetics 2020, 214, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Hu, M.; Jiang, J.; Dai, M.; Wang, B.; et al. Underestimated health risks: Polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics jointly induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by ROS-mediated epithelial cell apoptosis. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Nida, A.; Kong, Y.; Du, H.; Xiao, G.; Wang, D. Nanopolystyrene at predicted environmental concentration enhances microcystin-LR toxicity by inducing intestinal damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 183, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tan, X.; Shi, X.; Han, P.; Liu, H. Combined Effects of Micro- and Nanoplastics at the Predicted Environmental Concentration on Functional State of Intestinal Barrier in Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxics 2023, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Hua, X.; Dang, Y.; Han, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X.; Ding, P.; Li, H. Polystyrene microplastics (PS-MPs) toxicity induced oxidative stress and intestinal injury in nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.W.; Yen, P.L.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chang, C.H.; Liao, V.H. Nanoplastic exposure in soil compromises the energy budget of the soil nematode C. elegans and decreases reproductive fitness. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 120071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senchuk, M.M.; Dues, D.J.; Schaar, C.E.; Johnson, B.K.; Madaj, Z.B.; Bowman, M.J.; Winn, M.E.; Van Raamsdonk, J.M. Activation of DAF-16/FOXO by reactive oxygen species contributes to longevity in long-lived mitochondrial mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.Y.; Hench, J.; Ruvkun, G. Regulation of C. elegans DAF-16 and its human ortholog FKHRL1 by the daf-2 insulin-like signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Hsin, H.; Libina, N.; Kenyon, C. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.I.; Pincus, Z.; Slack, F.J. Longevity and stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging 2011, 3, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libina, N.; Berman, J.R.; Kenyon, C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell 2003, 115, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.S.S.; Medina, P.M.B. Leachates from plastics and bioplastics reduce lifespan, decrease locomotion, and induce neurotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 357, 124428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zongur, A. Evaluation of the Effects of Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) on Caenorhabditis elegans Survival and Fertility. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 8998–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Olsson, P.E.; Jass, J. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diethyl phthalate disrupt lipid metabolism, reduce fecundity and shortens lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2018, 190, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, M.; Fan, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, L.; Gao, P. Antibiotic and microplastic co-exposure: Effects on Daphnia magna and implications for ecological risk assessment. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 55, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiros, L.; Pereira, J.L.; Goncalves, F.J.M.; Pacheco, M.; Aschner, M.; Pereira, P. Caenorhabditis elegans as a tool for environmental risk assessment: Emerging and promising applications for a “nobelized worm”. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).