Sustainable Magnetic Nanorobots for Microplastics Remediation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microplastics and Nanoplastics

3. Magnetic Nanoparticles

3.1. Magnetic Properties of Nanoparticles

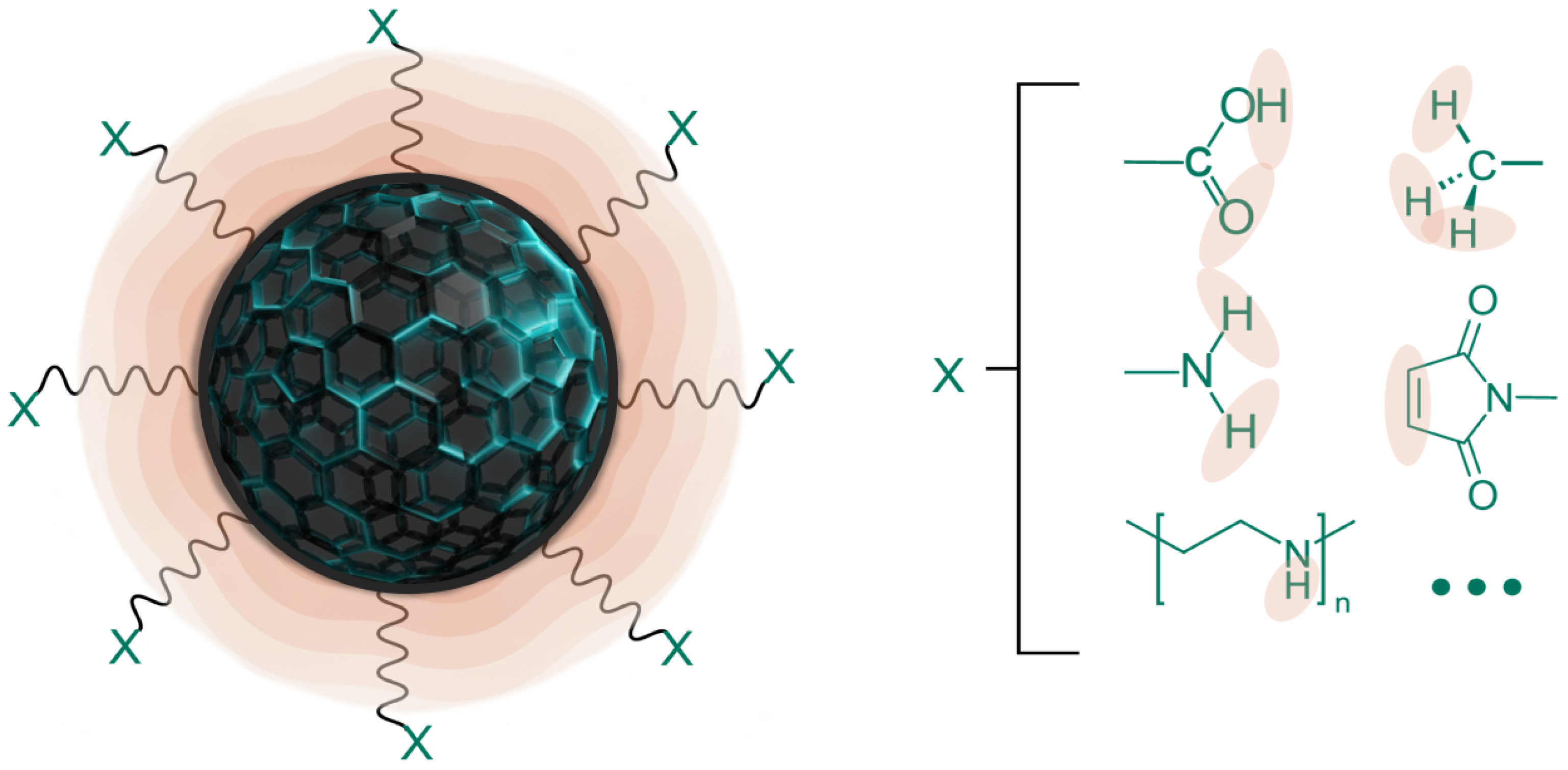

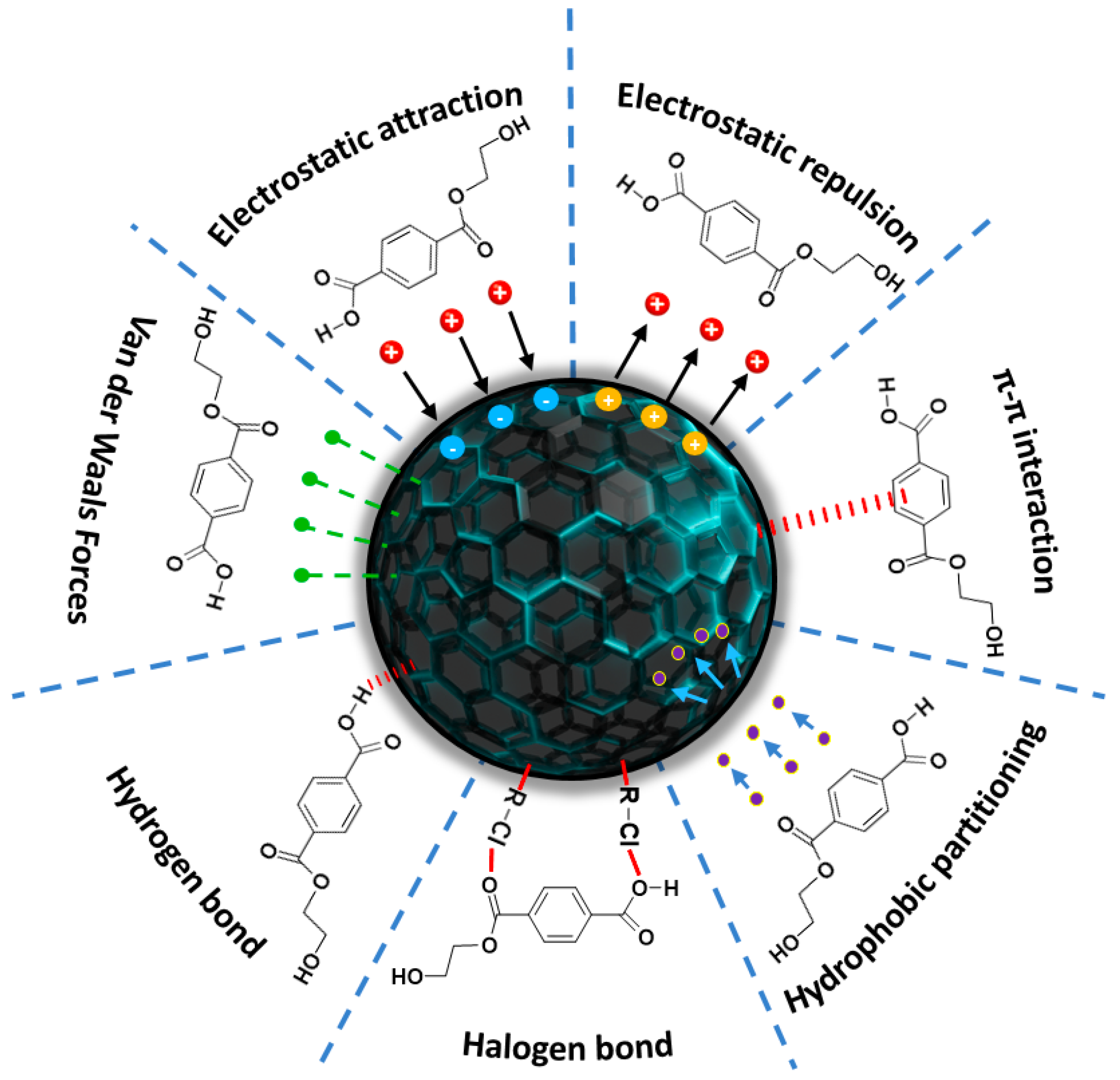

3.2. Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles

4. Hybrid Magnetic Nanomaterials

| Material Type | Removal Efficiency | Significant Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Fe nanoparticles [92] | Recovered 92% of 10–20 µm polyethylene and polystyrene beads and 93% of polyethylene, polyethylene terephthalate, polystyrene, polyurethane, polyvinyl chloride, and polypropylene from seawater. | Magnetic extraction of microplastics from environmental samples. |

| Magnetic Nano-Fe3O4 [54] | PE 86.9%; PP 85.1%; PS 86.1%; PET 62.8%. | Surface adsorption + magnet capture; validated in river/sewage/seawater. |

| Fe3O4 nanoparticles (FNPs) [93] | Removal 83.1–92.9%. | Charge neutralization; hetero-aggregation; pH < 6.7 best; salinity helps at alkaline. |

| Fe3O4 (Bare MNPs) [86] | HDPE, PP, PVC, PS, PET → ≈100% removal (order: PET > PS > HDPE > PVC > PP). | Fast removal in 5 min. The peroxidase-like activity of the exposed surface aids catalytic degradation. |

| Fe3O4 nanoparticles with fluorescent dyes [83] | 90% removal of nanoplastics within 120 min. | Fluorescent dyes combined with photoluminescence spectroscopy as an alternative approach for detecting and quantifying nanoplastics in water. |

| PEG-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles [85] | Maximum adsorption of 2203 mg/g for polyethylene microspheres. | These systems operate primarily through intermolecular hydrogen bonding mechanisms. |

| Ultra-thin Fe3O4 Nanodiscs [94] | Adsorption capacity of 188.4 mg/g. | The removal mechanism involves both electrostatic and magnetic forces originating from the vortex domain of the nanodiscs. |

| Fe3O4@PDA [95] | Removal efficiencies up to 98.5%. | The PDA coating enhances adhesion through hydrogen bonding, stacking, and hydrophobic interactions. |

| Imine-functionalized mesoporous magnetic silica nanoparticles [96] | 96% removal efficiency for microplastics loaded with organic pollutants. | Design of experiments and machine learning were used for multi-objective optimization in magnetic separation. |

| Magnetic sepiolite [54] | One cycle removal time is 600 s, and removal efficiency is 98.4%. | Magnetic carrier medium can be effectively recycled with the magnetic tube. |

| Fe3O4@Citric Acid [81] | HDPE, LDPE, PP → 80% removal at pH 6; reusable up to 5 cycles (>50% efficiency). | Removal is governed by hydrogen bonding, pore filling, and van der Waals forces. Reusability confirmed. |

| TA-Fe3O4 [72] | PS (83%), PET (98%) at pH 6–7, 300 min. | High efficiency due to electrostatic, hydrophobic, –, and H-bonding interactions. Maintained efficiency after 5 cycles. |

| Cobalt ferrite@Lauric Acid [1] | >99.6% microplastics removed; >98% after 10 cycles. | Synergistic effect of hydrophobicity and van der Waals forces. Excellent stability and recyclability. |

| HDTMS−FeNPs [84] | Polystyrene nanoplastics → 84.9%. | Hydrophobic functionalization enhanced PS adsorption. |

| Fe3O4@Ag@L-Cysteine [80] | PS → 100% removal (50 mg/L microplastics in 15 min, neutral pH) | Most efficient among the compared MNPs. Physisorption mechanism. Lower concentrations and shorter times are required. |

| Fe@ZIF−8@n-butylamine [87] | PS microspheres → 98% (25 mg/L microplastics), 88.7% (50 mg/L microplastics). | Hydrophobic functionalization enhanced adsorption. Effective at neutral pH in only 5 min under stirring. |

| CoFe2O4@SDS ferrofluid [88] | PVC → 69.3% (functionalized), 53.35% (bare MNPs). | Performance improved with SDS functionalization. Efficiency is affected by wastewater contaminants. Oil addition reduced performance. |

| Fe3O4@Sodium alginate (SA)/Fe3O4@Amino (TMPED) [89] | PE microspheres: SA-MNPs → 82.4%, Amino-MNPs → 75.5%. | Removal favored at slightly acidic pH (5.2). Hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions between surface functional groups and microplastics enhanced adsorption. |

| Magnetic Coal gangue [97] | Adsorption capacity for polystyrene microplastics of 35.9 mg/g. | Coal gangue is a solid waste byproduct from coal mining and washing |

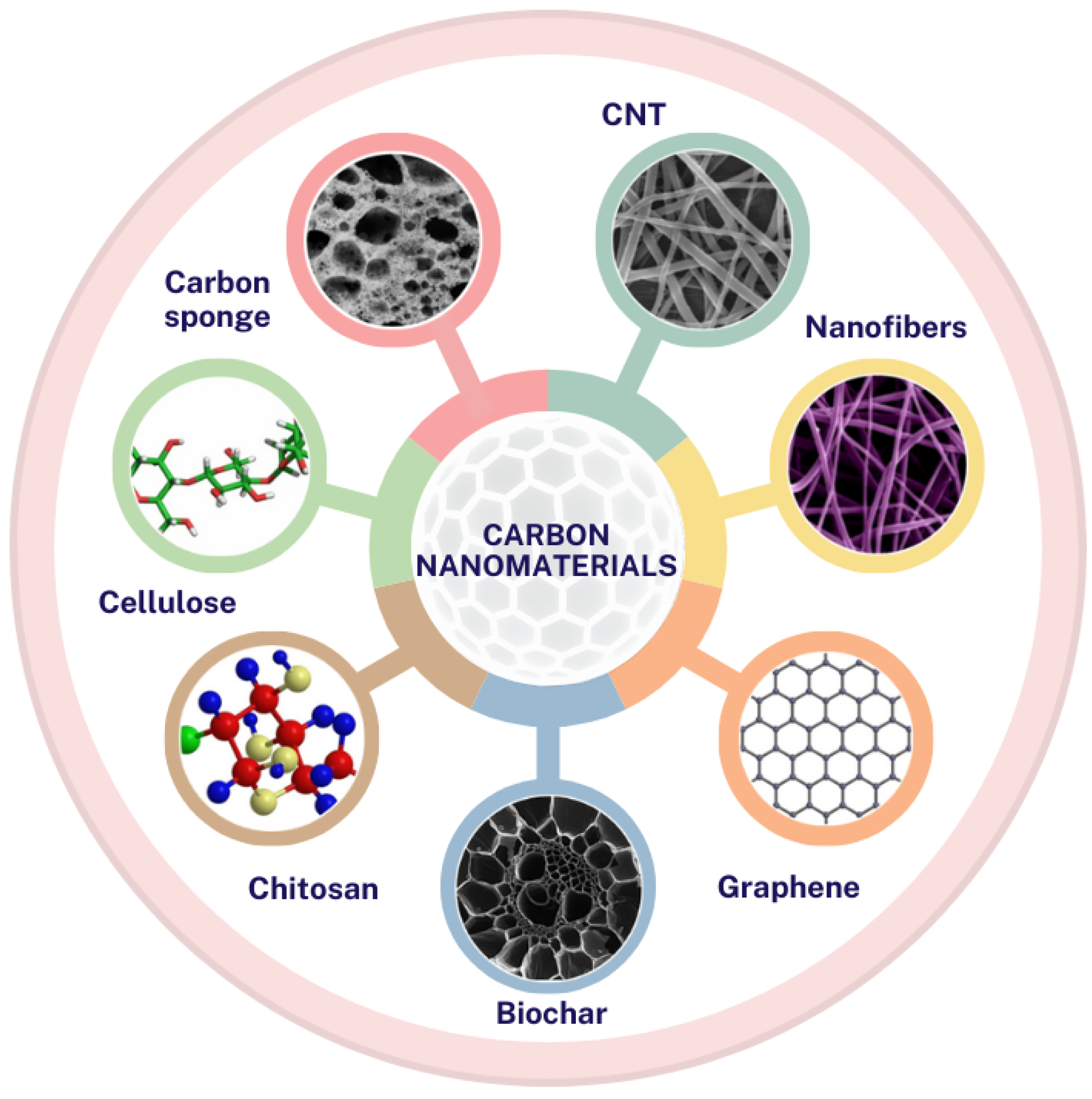

5. Magnetic Carbon Nanomaterials

| Material Type | Removal Efficiency | Significant Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic/CNTs [26] | 100% in 300 min for polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyamide (PA) microplastics. | Strong affinity to the surfaces of all typical microplastics in testing solution and wastewater. |

| Graphene-like Magnetic Biochar [112] | The adsorption capacity of GLMB at 288 K (98.73 mg/g). | GLMB exhibited green, economical, high-efficiency, and reusable performance. |

| Black tea extract-based Magnetic Nanoparticles (BTMNPs) [120] | 90% microplastics removal efficiency. | Utilize polyphenol components as alternatives to toxic chemicals in the synthesis process. |

| Fe-doped porous carbon sponge [121] | mg g−1 | Fe–C chemisorption (DFT) + –; effects; rapid adsorption; scalable synthesis. |

| –OH/–COOH/–NH2-Fe3O4 [46] | (PE) ∼1611 mg g−1; 13–18; 24–30 | Ion exchange; H-bonding; electrostatics. |

| Mg/Zn Modified Magnetic Biochar [98] | 94.8–99.5% removal; –375 mg g−1 | Multipollutant removal; favorable LCA. |

| Chitosan-modified magnetic durian shell Biochar [15] | 97.22%; mg g−1; 76.41% after 5× | Electrostatic + metal–O–PS; 5 cycles; real water tolerant. |

| PEG/PEI-coated Magnetic Biochar-Zeolite [122] | 736–769 mg g−1 | Electrostatic, H-bonding, – stacking; green synthesis; low-cost reuse. |

| Magnetic Biochar (MBC) [123] | –248 mg g−1 | Electrostatic (), heterogeneous sites; ultra-high adsorption; regenerable composite. |

| g-C3N4@Fe3O4 & BNNS@Fe3O4 [124] | >92–96% (Milli-Q); ∼92% (effluent); ∼80% after 3 cycles | Electrostatic + hydrophobic; Fe–O bands; rapid chemisorption; reusable. |

| Nanobiochar (OA-modified) [122] | 93.4% (OA@NBA); 87.4% (OA@NBP) | Electrostatic, –, H-bonding, vdW; high efficiency; magnetic recovery. |

| Fe3O4-PWA/nOct [125] | 99% (PS & PET); 83% (polysulphone) | –; multilayer adsorption; acidic water removal; regenerable. |

| POM-IL@SiO2@Fe3O4 [126] | PVC removed; metals 79.5–99.3%/92–99% | Hydrophobic adsorption; magnetic separation; scalable, robust. |

| Cellulose-Benzoate/MCNT [109] | >97%; mg mg−1 | Co-removal platform; hydrophobic interaction; electrostatic. |

| Magnetic Seeded Filtration (MSF) [113] | Up to 95% (lab scale). | –/hydrophobic + magnetic; robust; 4× thermo-regen. |

| Scaled-up iron oxide Nanoflowers (NFs) [110] | Up to 1000 mg_MP g_NF−1; 20–78% mineralization. | Hetero-agglomeration + magnetic separation; scalable; reusable; dual harvesting. |

| Fe3O4@C12 Superhydrophobic [15] | mg g−1 | Hydrophobic + electrostatic + vdW; works in beverages; QA/QC. |

| Fe3O4@TiO2-CAN [127] | 97.3% (PE); 96% (TC); 77.07% recyclability. | Photocatalytic degradation (S-scheme charge transfer; ROS generation); best-in-class TiO2 performance. |

| CTAB-Modified Magnetic Biochar [123] | The maximum microplastics removed were 98%. | The reusability results revealed that the developed RH-MBC-CTAB could maintain good stability for up to three reusability cycles. |

| Magnetic Biochar prepared by Red Mud [25] | The maximum adsorption capacities of original and modified biochar for PS were 227, 292, and 306 mg/g at pH 3–7, respectively. | The metal active sites provided by red mud noticeably contributed to the removal of microplastics. |

| Fe-modified lignin-based Magnetic Biochar [128] | The removal efficiency of polystyrene microplastics was 99%, with an adsorption capacity of 68.57 mg/g, which was 25 times higher than that of unmodified lignin biochar. | The effects of lignin/Fe salt mass ratios, adsorbent amount, adsorption time, adsorption temperature, solution pH, and presence of coexisting anions on adsorption efficiency were investigated. |

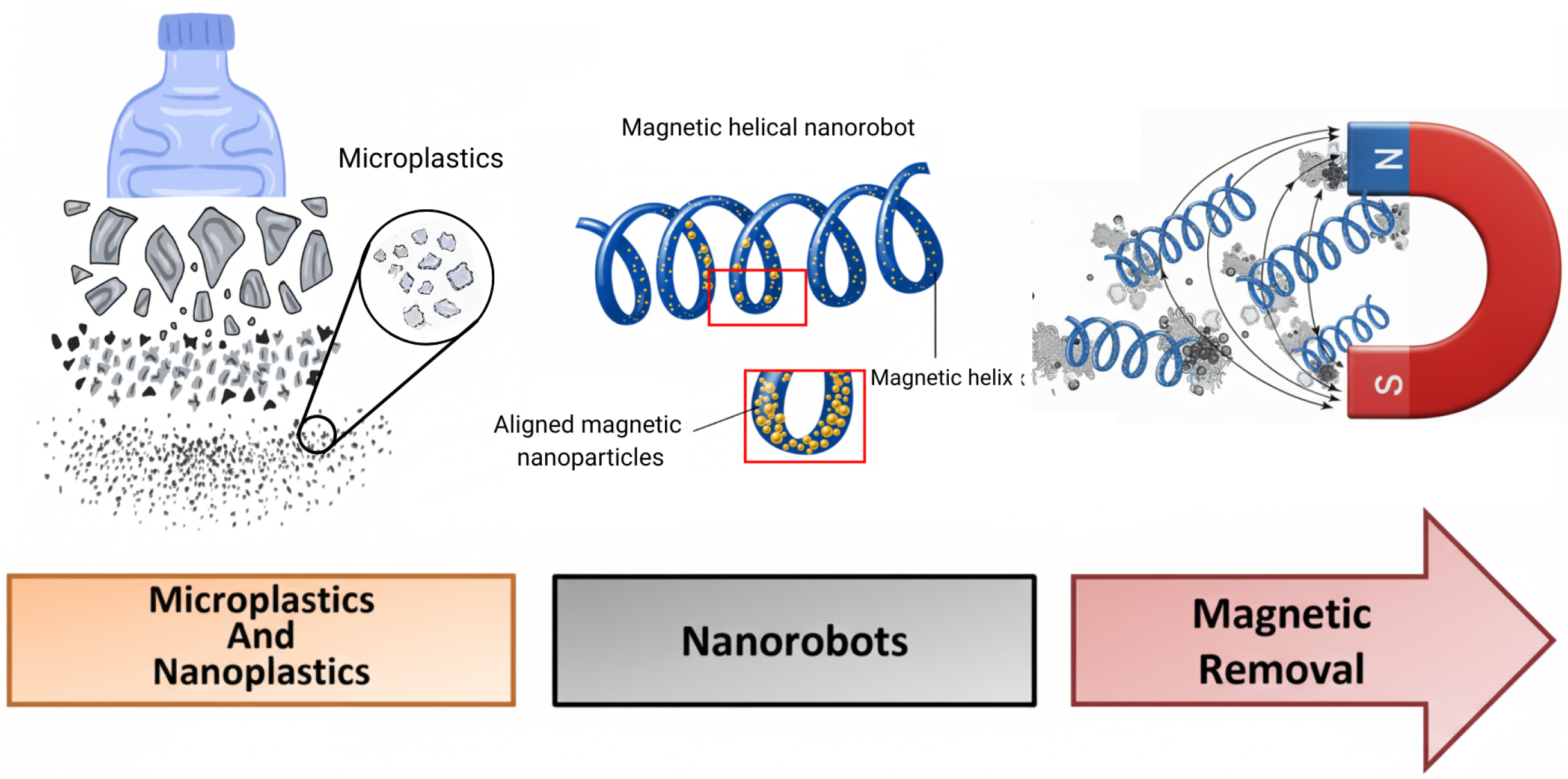

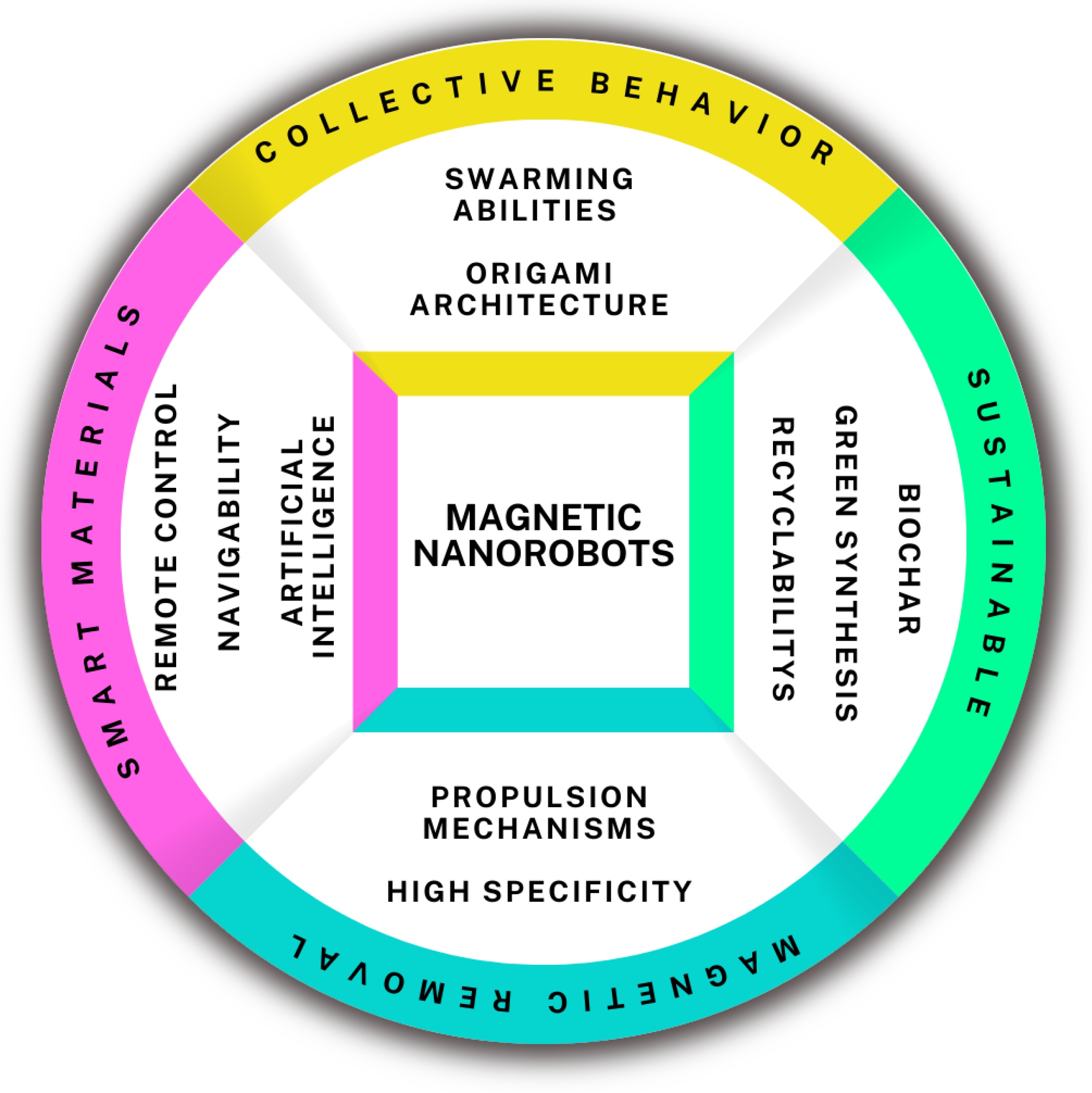

6. Advanced Sustainable Nanorobots for Microplastics Removal

| Material Type | Removal Efficiency | Significant Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Living Bacterial Nanorobots [136] | 83–89% for PS nanoplastics and 60–96% for microplastics derived from PET. | Nature-inspired three-dimensional (3D) swarming motion. |

| Nanorobots based on Magnetic beads [11] | Captured 80% of the bacteria within 30 min. | Magnetic beads with polymeric “hands” to capture microplastics and bacteria. |

| Biohybrid Nanorobots [27] | 92% for nanoplastics and 70% for microplastics. | Algae platforms with magnetic nanoparticles. |

| PDA/PEI@Fe3O4 MagRobots [143] | 99% removal of polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles. | Sea-urchin-like structure, with a large surface area and an adsorption capacity up to 594.3 mg/g. |

| LiquidBots [137] | 80% of micro/nanoplastics. | A reconfigurable and regenerable gallium-based liquid metal. |

| Keratin-based biohybrid nanorobots [46] | Removal efficiency for micro/nanoplastics with 95% and 82%. | Fe3O4 microspheres on waste human hairs as structural fiber supports. |

| Magnetic hydrogel Nanorobots (MHMs) [144] | 95% removal efficiency within 3 min. | Removal efficiency through dynamic spinning that generates hydrodynamic flows. |

| Magnetic microsubmarine based on a sunflower pollen grain [138] | 70% removal efficiency. | The fluid induced by the cooperative microsubmarines can remove the microplastics controllably in a non-contact method. |

| Ag@Bi2WO6/Fe3O4 [145] | 98% cleaning efficiency in 93 s. | Low-energy photoresponsive magnetic-assisted cleaning microrobot (LMCM) composed of photocatalytic material (Ag@Bi2WO6) and magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4). |

| Silane-modified superhydrophobic geopolymer foam [141] | 99% removal efficiency for polyethylene microspheres in wastewater. | Geopolymers’ transformative potential in addressing microplastic contamination. |

| Maifanite with a rotating magnetic field [146,147] | The removal efficiency ultimately achieves 100% when the concentration ratio with microplastics is set at 50%. | The influence of the flow field is remarkable in the magnetic removal process. |

| Iron–nitrogen co-doped layered biocarbon materials [148] | 96.5% removal efficiency for PS microplastics. | Molecular dynamics simulations explain interactions between doped carbon and microplastics. |

| Polydopamine Enhanced Magnetic Chitosan (PDA-MCS) [148] | Removal efficiency of up to 91.6%. | Coral bio-inspired aerogels based on polydopamine and chitosan. |

| Magnetically steerable iron oxides-manganese dioxide core–shell micromotors [149] | Separated more than 10% of the suspended microplastics from the polluted water in 2 h. | Low-cost and scalable fabrication of bubble-propelled iron oxides-MnO2 core–shell micromotors (Fe3O4-MnO:2 and Fe2O3-MnO2) for pollutant removal. |

| Magnetic N-doped nanocarbon springs [150] | The Mn@NCNTs/PMS system can realize 50 wt % of microplastics removal by assisting with hydrolysis. | The magnetic nanohybrids were applied for peroxymonosulfate activation to generate highly oxidizing radicals to decompose microplastics under hydrothermal conditions. |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, A.; Rius-Ayra, O.; Kang, M.; Llorca-Isern, N. Durably Superhydrophobic Magnetic Cobalt Ferrites for Highly Efficient Oil–Water Separation and Fast Microplastic Removal. Langmuir 2024, 40, 21533–21546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, M.; Mithun, N.; Xavier, K.A.M.; Nayak, G.; Kalthur, G.; Chidangil, S.; Kumar, S.; Lukose, J. Exploring the detrimental effects of nanoplastics on ecosystems and human health. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.F.; Li, K.; Liu, S.P.; Dai, N.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.X.; Li, H. A review of nanomaterials with excellent purification potential for the removal of micro- and nanoplastics from liquid. DeCarbon 2024, 5, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Devriese, L.; Galgani, F.; Robbens, J.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in sediments: A review of techniques, occurrence and effects. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Tan, X.; Mustafa, G.; Gao, J.; Peng, C.; Naz, I.; Duan, Z.; Zhu, R.; Ruan, Y. Removal of micro- and nanoplastics by filtration technology: Performance and obstructions to market penetrations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henze, M.; Comeau, Y. Wastewater characterization. In Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles Modelling and Design; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2008; Volume 27, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Chander, T.; Bajpai Tripathy, D.; Pradhan, S. Removal of microplastic and plasticizer from waterbodies; A review. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein, F.; Nirschl, H.; Kaegi, R. Separation of Microplastic Particles from Sewage Sludge Extracts Using Magnetic Seeded Filtration. Water Res. X 2022, 17, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, K.; Hasan, A.; Hussain Naqvi, S.K.; Parveen, S.; Hussain, A.; Ko, K.C.; Park, S.H. Recent advances and factors affecting the adsorption of nano/microplastics by magnetic biochar. Chemosphere 2025, 370, 143936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, L.; Yadav, K.; Dey, U.; Das, K.; Kumari, P.; Raj, D.; Mandal, R.R. Recent advancement in microplastic removal process from wastewater—A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussia, M.; Urso, M.; Oral, C.M.; Peng, X.; Pumera, M. Magnetic Microrobot Swarms with Polymeric Hands Catching Bacteria and Microplastics in Water. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 13171–13183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, M.; Ussia, M.; Peng, X.; Oral, C.M.; Pumera, M. Reconfigurable self-assembly of photocatalytic magnetic microrobots for water purification. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Mayorga-Martinez, C.C.; Pané, S.; Zhang, L.; Pumera, M. Magnetically Driven Micro and Nanorobots. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4999–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Go, G.; Zhen, J.; Hoang, M.C.; Kang, B.; Choi, E.; Park, J.O.; Kim, C.S. Locomotion and disaggregation control of paramagnetic nanoclusters using wireless electromagnetic fields for enhanced targeted drug delivery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pal, D.; Pilechi, A.; Ariya, P.A. Nanoplastics in Water: Artificial Intelligence-Assisted 4D Physicochemical Characterization and Rapid In Situ Detection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 8919–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rollán, M.; Sanz-Santos, E.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Key adsorbents and influencing factors in the adsorption of micro- and nanoplastics: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 383, 125394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, L.; Gong, Y.; Liu, P. Adsorption behavior and interaction mechanism of microplastics with typical hydrophilic pharmaceuticals and personal care products. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Luo, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Fe(III) Adsorption onto Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: Interaction Mechanism, Influencing Factors, and Adsorption Capacity Prediction. Water 2025, 17, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Kong, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Jia, J.; Zhou, H.; Yan, B. Electrostatic attraction of cationic pollutants by microplastics reduces their joint cytotoxicity. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Ye, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. Hydrogen bonding-mediated interaction underlies the enhanced membrane toxicity of chemically transformed polystyrene microplastics by cadmium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuwa-Amarh, N.A.; Dizbay-Onat, M.; Venkiteshwaran, K.; Wu, S. Carbon-Based Adsorbents for Microplastic Removal from Wastewater. Materials 2024, 17, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Maldonado, E.A.; Khan, N.A.; Singh, S.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Kabak, B.; Vega Baudrit, J.R.; Alkahtani, M.Q.; Álvarez Torrellas, S.; Varshney, R.; Serra-Pérez, E.; et al. Magnetic polymeric composites: Potential for separating and degrading micro/nano plastics. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.G.; Mihaiescu, B.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Hadibarata, T.; Grumezescu, A.M. An Updated Overview of Magnetic Composites for Water Decontamination. Polymers 2024, 16, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, A.E.; Dickson-Anderson, S.E.; Guo, Y. Utilizing nature-based adsorbents for removal of microplastics and nanoplastics in controlled polluted aqueous systems: A systematic review of sources, properties, adsorption characteristics, and performance. Next Sustain. 2025, 5, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Gong, R.; Zheng, J. The combined effect of pyrolysis temperature and surfactant on adsorption of microplastics by spontaneous magnetism biochar from sludge and red mud. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 192, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, B. Removal of microplastics from aqueous solutions by magnetic carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Urso, M.; Kolackova, M.; Huska, D.; Pumera, M. Biohybrid Magnetically Driven Microrobots for Sustainable Removal of Micro/Nanoplastics from the Aquatic Environment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2307477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, J.; Wei, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Ni, B.J. Emerging adsorbents for micro/nanoplastics removal from contaminated water: Advances and perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Lamichhane, G.; Khadka, D.; Devkota, H.P. Microplastics contamination in food products: Occurrence, analytical techniques and potential impacts on human health. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 7, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Ahmed, U.; Ahmad, M.A. Impact of Microplastics on Human Health: Risks, Diseases, and Affected Body Systems. Microplastics 2025, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadique, S.A.; Konarova, M.; Niu, X.; Szilagyi, I.; Nirmal, N.; Li, L. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human Health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.L.; Lamarre, A. The impact of micro- and nanoplastics on immune system development and functions: Current knowledge and future directions. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025, 135, 108951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsworthy, A.; O’Callaghan, L.A.; Blum, C.; Horobin, J.; Tajouri, L.; Olsen, M.; Van Der Bruggen, N.; McKirdy, S.; Alghafri, R.; Tronstad, O.; et al. Micro-nanoplastic induced cardiovascular disease and dysfunction: A scoping review. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 746–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Sui, J.; Ma, H.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, R.; Wang, S.; Dai, Y. Emerging absorption-based techniques for removing microplastics and nanoplastics from actual water bodies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 285, 117058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyc, H.J.; Kłodnicka, K.; Teresińska, B.; Karpiński, R.; Flieger, J.; Baj, J. Micro- and Nanoplastics as Disruptors of the Endocrine System—A Review of the Threats and Consequences Associated with Plastic Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, J.; Hong, T.; Song, G. Impact and mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics on the reproductive system. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2025, 21, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.M.; Nair, J.B.; Joseph, A.M. Microscopic menace: Exploring the link between microplastics and cancer pathogenesis. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2025, 27, 1768–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Nag, R.; Cummins, E. Ranking of potential hazards from microplastics polymers in the marine environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Z.; Agyei Boakye, A.A.; Yao, Y. Environmental impacts of biodegradable microplastics. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Yu, H.; Xi, B.; Tan, W. A review on the occurrence and influence of biodegradable microplastics in soil ecosystems: Are biodegradable plastics substitute or threat? Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajedi, S.; An, C.; Chen, Z. Unveiling the hidden chronic health risks of nano- and microplastics in single-use plastic water bottles: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, A.; Jiang, J.; Liang, Y.; Cao, X.; He, D. Removal of microplastics in water: Technology progress and green strategies. Green Anal. Chem. 2022, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Tanaka, S.; Koyuncu, C.Z.; Nakada, N. Removal of microplastics in wastewater by ceramic microfiltration. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 54, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, H.; Fei, L.; Wei, B.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, H. The removal of microplastics from water by coagulation: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 851, 158224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Khujaniyoz, S.; Oh, H.; Kim, H.; Hong, T. The removal of microplastics from reverse osmosis wastewater by coagulation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, S.; Zhong, W.; Wang, H.; Uthappa, U.; Wang, B. Upscaling waste human hairs into micro/nanorobots for adsorptive removal of micro/nanoplastics. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sathish, C.I.; Guan, X.; Wang, S.; Palanisami, T.; Vinu, A.; Yi, J. Advances in magnetic materials for microplastic separation and degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Degradation of microplastic in water by advanced oxidation processes. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 141939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, G.; Fenti, A.; Galoppo, S.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D.; Cocca, M.; Mallardo, S.; Iovino, P. Promoting removal of polystyrene microplastics from wastewater by electrochemical treatment. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 68, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Almatrafi, E.; Hu, T.; Zhou, C.; Song, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, G. Efficient removal of microplastics from wastewater by an electrocoagulation process. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembo, R.O.; Phiri, Z.; Madikizela, L.M.; Kamika, I.; de Kock, L.A.; Msagati, T.A.M. Global Research Trends in Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics: A Bibliometric Perspective. Microplastics 2025, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Gong, H.; Yan, M. Biological Degradation of Plastics and Microplastics: A Recent Perspective on Associated Mechanisms and Influencing Factors. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohl, S.; Kristl, M.; Stergar, J. Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Ma, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, H.; Cheng, S. Experimental study on removal of microplastics from aqueous solution by magnetic force effect on the magnetic sepiolite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, K.; Lenz, R.; Stedmon, C.A.; Nielsen, T.G. Abundance, size and polymer composition of marine microplastics ≥ 10 µm in the Atlantic Ocean and their modelled vertical distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Luan, Y.; Dai, W. Adsorption behavior of organic pollutants on microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, F.; Ma, J. Sorption behavior and mechanism of hydrophilic organic chemicals to virgin and aged microplastics in freshwater and seawater. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majetich, S.A.; Wen, T.; Mefford, O.T. Magnetic Nanoparticles. MRS Bull. 2013, 38, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, S.; Suarez, J.; Gonzalez, G. Solvothermal synthesis of cobalt ferrite hollow spheres with chitosan. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 78, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briceño, S.; Brämer-Escamilla, W.; Silva, P.; Delgado, G.E.; Plaza, E.; Palacios, J.; Cañizales, E. Effects of synthesis variables on the magnetic properties of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 2926–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, O.; Briceño, S.; Brämer-Escamilla, W.; Silva, P. Toroidal cores of MnxCo1-xFe2O4/PAA nanocomposites with potential applications in antennas. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 192, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daboin, V.; Briceño, S.; Suárez, J.; Gonzalez, G. Effect of the dispersing agent on the structural and magnetic properties of CoFe2O4/SiO2 nanocomposites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 451, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, R. Metodologías para la síntesis de nanopartículas: Controlando forma y tamaño. Mundo Nano Rev. Interdiscip. Nanociencias Nanotecnología 2012, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomutov, G.B.; Koksharov, Y.A. Organized Ensembles of Magnetic Nanoparticles: Preparation, Structure, and Properties. In Magnetic Nanoparticles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; pp. 117–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Walle, A.; Perez, J.E.; Abou-Hassan, A.; Hémadi, M.; Luciani, N.; Wilhelm, C. Magnetic nanoparticles in regenerative medicine: What of their fate and impact in stem cells? Mater. Today Bio. 2020, 7, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kartikowati, C.W.; Horie, S.; Ogi, T.; Iwaki, T.; Okuyama, K. Correlation between particle size/domain structure and magnetic properties of highly crystalline Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coey, J.M.D. Magnetism and Magnetic Materials; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 628. [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov, V.; Raikher, Y. Magnetorelaxometry in the Presence of a DC Bias Field of Ferromagnetic Nanoparticles Bearing a Viscoelastic Corona. Sensors 2018, 18, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, B.; Obaidat, I.M.; Albiss, B.A.; Haik, Y. Magnetic nanoparticles: Surface effects and properties related to biomedicine applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21266–21305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppe, P.; Wintzheimer, S.; Eigen, A.; Gaß, H.; Halik, M.; Mandel, K. Real-time monitoring of magnetic nanoparticle-assisted nanoplastic agglomeration and separation from water. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlyandskaya, G.V.; Novoselova, I.P.; Schupletsova, V.V.; Andrade, R.; Dunec, N.A.; Litvinova, L.S.; Safronov, A.P.; Yurova, K.A.; Kulesh, N.A.; Dzyuman, A.N.; et al. Nanoparticles for magnetic biosensing systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 431, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacko, A.; Nure, J.F.; Nyoni, H.; Mamba, B.; Nkambule, T.; Msagati, T.A. The Application of Tannic Acid-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for Recovery of Microplastics from the Water System. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2024, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyakhman, F.; Byzov, I.; Kramarenko, E.; Zubarev, A.; Mekhonoshin, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Safronov, A.; Orue, I.; Barandiarán, J.M.; Kurlyandskaya, G.V. Polyacrylamide ferrogels with embedded maghemite nanoparticles for biomedical engineering. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 3624–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagya, L.; Upeksha, S.; Kirthika, V.; Galpaya, C.; Koswattage, K.; Wijesekara, H.; Perera, V.; Ireshika, W.A.; Chamanee, G.; Rajapaksha, A.U. Nanomaterials for microplastics remediation in wastewater: A viable step towards cleaner water. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puteri, M.N.; Gew, L.T.; Ong, H.C.; Ming, L.C. Technologies to eliminate microplastic from water: Current approaches and future prospects. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.; Devi, A.; Maduka, T.; Tyagi, L.; Rana, S.; Akuwudike, I.; Wang, Q. A Review of Materials for the Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics from Different Environments. Micro 2025, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, M.; Juárez Onofre, J.; Ibarra Hurtado, J.; Valdez-Grijalva, M. Interaction of charged magnetic nanoparticles with surfaces. Rev. Mex. Física 2024, 70, 051004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefalt, G.; Borkovec, M. Overview of DLVO Theory. In Archive Ouverte UNIGE; Institutional Repository; University of Geneva: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Divya, V.; Deivayanai, V.; Anbarasu, K.; Saravanan, A.; Vickram, A. A review on advances in hybrid magnetic nanoparticles for microplastics removal: Mechanistic insights and emerging prospects. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Martínez, Y.; Soler-García, I.; Hernández-Córdoba, M.; López-García, I.; Penalver, R. Development of a Fast and Efficient Strategy Based on Nanomagnetic Materials to Remove Polystyrene Spheres from the Aquatic Environment. Molecules 2024, 29, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, I.d.S.d.; Freire, E.d.A.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Vercillo, O.E.; Silva, M.F.P.d.; Rocha, M.F.S.d.; Amaral, M.C.S.; Amorim, A.K.B. Sustainable Strategy for Microplastic Mitigation: Fe3O4 Acid-Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles for Microplastics Removal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y. Micro/Nanorobotics in Environmental Water Governance: Nanoengineering Strategies for Pollution Control. Small Struct. 2025, 6, 2500058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikov, D.I.; Jancik-Prochazkova, A.; Pumera, M. On-the-Fly Monitoring of the Capture and Removal of Nanoplastics with Nanorobots. ACS Nanosci. Au 2024, 4, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surette, M.C.; Mitrano, D.M.; Rogers, K.R. Extraction and Concentration of Nanoplastic Particles from Aqueous Suspensions Using Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles and a Magnetic Flow Cell. Microplastics Nanoplastics 2023, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Liu, R.; Petropoulos, E.; Feng, Y.; Xue, L.; Yang, L.; He, S. Efficient magnetic capture of PE microplastic from water by PEG modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles: Performance, kinetics, isotherms and influence factors. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, M.; Liu, J. Removal and Degradation of Microplastics Using the Magnetic and Nanozyme Activities of Bare Iron Oxide Nanoaggregates. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202212013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, F.; Fuller, R.O.; Maya, F. Fast and Simultaneous Removal of Microplastics and Plastic-Derived Endocrine Disruptors Using a Magnetic ZIF-8 Nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.T.; Tran, T.D. Microplastic Removal Using CoFe2O4/SDS Ferrofluid: Efficiency, Reusability, and Environmental Impact. Manuscript, not formally published.

- Aragón, D.; García-Merino, B.; Barquín, C.; Bringas, E.; Rivero, M.J.; Ortiz, I. Advanced green capture of microplastics from different water matrices by surface-modified magnetic nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Devnani, G.L.; Gupta, P. Magnetic separation and degradation approaches for effective microplastic removal from aquatic and terrestrial environments. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 3043–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Vaidya, A.N.; Kumar, A. Microplastic properties and their interaction with hydrophobic organic contaminants: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 49490–49512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grbic, J.; Nguyen, B.; Guo, E.; You, J.B.; Sinton, D.; Rochman, C.M. Magnetic Extraction of Microplastics from Environmental Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Lin, S.; Jiang, W.; Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Sui, Q. Effect of Aggregation Behavior on Microplastic Removal by Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 898, 165431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-chun, Y.; Sathish, C.I.; Li, Z.; Ahmed, M.I.; Perumalsamy, V.; Cao, C.; Yu, C.; Wijerathne, B.; Fleming, A.J.; Qiao, L.; et al. Plastics adsorption and removal by 2D ultrathin iron oxide nanodiscs: From micro to nano. Chem. Eng. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, S.; Feng, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H. Corals-inspired magnetic absorbents for fast and efficient removal of microplastics in various water sources. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 11908–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushdi, I.W.; Hardian, R.; Rusidi, R.S.; Khairul, W.M.; Hamzah, S.; Wan Mohd Khalik, W.M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Yahaya, N.K.E.; Szekely, G.; Azmi, A.A. Microplastic and organic pollutant removal using imine-functionalized mesoporous magnetic silica nanoparticles enhanced by machine learning. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Cui, W.; Yang, S.; Zheng, K.; Song, F.; Liu, Z.; Ji, P. Potential of a novel magnetic gangue material for remediating wastewater and field co-polluted by microplastics and heavy metals. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 133030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Huang, Q.X.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J.H. Adsorption and Thermal Degradation of Microplastics from Aqueous Solutions by Mg/Zn Modified Magnetic Biochars. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Xiang, M.; Wang, W.; Su, Z.; Liu, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, P. Engineering 3D graphene-like carbon-assembled layered double oxide for efficient microplastic removal in a wide pH range. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 433, 128672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Li, B.; Wan, H.; Lin, X.; Cai, Y. Coral-inspired environmental durability aerogels for micron-size plastic particles removal in the aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeeyo, A.O.; Alabi, M.A.; Oyetade, J.A.; Nkambule, T.T.I.; Mamba, B.B.; Oladipo, A.O.; Makungo, R.; Msagati, T.A.M. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Advances in Synthesis, Sensing, and Theragnostic Applications. Magnetochemistry 2025, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyah, Y.; El Messaoudi, N.; Benjelloun, M.; El-Habacha, M.; Georgin, J.; Huerta Angeles, G.; Knani, S. Comprehensive review on advanced coordination chemistry and nanocomposite strategies for wastewater microplastic remediation via adsorption and photocatalysis. Surfaces Interfaces 2025, 72, 106955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, N.; Kumar, K.; Umar, A.; Almas, T.; Baskoutas, S. Sustainable synthesis and multifunctional applications of biowaste-derived carbon nanomaterials and metal oxide composites: A review. Chemosphere 2025, 385, 144540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soffian, M.S.; Abdul Halim, F.Z.; Aziz, F.; Rahman, M.A.; Mohamed Amin, M.A.; Awang Chee, D.N. Carbon-based material derived from biomass waste for wastewater treatment. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahshoori, I.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Namayandeh Jorabchi, M.; Zare Kazemabadi, F.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Mohammadi, A.H. Recent advances and applications of stimuli-responsive nanomaterials for water treatment: A comprehensive review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 333, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.P.; Huang, X.H.; Chen, J.N.; Dong, M.; Nie, C.Z.; Qin, L. Modified Superhydrophobic Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Removal of Microplastics in Liquid Foods. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Ni, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Lu, Y. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Multimode Microrobot Swarm Behaviors. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 12883–12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Khandelwal, N.; Ganie, Z.A.; Tiwari, E.; Darbha, G.K. Eco-friendly magnetic biochar: An effective trap for nanoplastics of varying surface functionality and size in the aqueous environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J. Exploring the Potential of Cellulose Benzoate Adsorbents Modified with Carbon Nanotubes and Magnetic Carbon Nanotubes for Microplastic Removal from Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Cordova, A.; Corrales-Pérez, B.; Cabrero, P.; Force, C.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; Ovejero, J.G.; Morales, M.d.P. Magnetic Harvesting and Degradation of Microplastics Using Iron Oxide Nanoflowers Prepared by a Scaled-Up Procedure. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Alomar, T.S.; Tariq, M.; AlMasoud, N.; Bhatti, M.H.; Ajmal, M.; Nazar, Z.; Nadeem, M.; Asif, H.M.; Sohail, M. Nanoarchitectonics of Molybdenum Rich Crown Shaped Polyoxometalates Based Ionic Liquids Reinforced on Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Removal of Microplastics and Heavy Metals from Water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, P.; Dai, M.; Xu, W.; Wen, J. Synthesis a graphene-like magnetic biochar by potassium ferrate for 17β-estradiol removal: Effects of Al2O3 nanoparticles and microplastics. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 715, 136723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, F.; Scholl, F.; Nirschl, H. Magnetic Seeded Filtration for the Separation of Fine Polymer Particles from Dilute Suspensions: Microplastics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 207, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Gao, S.H.; Ge, C.; Gao, Q.; Huang, S.; Kang, Y.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Removing microplastics from aquatic environments: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2023, 13, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Ducoli, S.; Depero, L.E.; Prica, M.; Tubić, A.; Ademovic, Z.; Morrison, L.; Federici, S. A Complete Guide to Extraction Methods of Microplastics from Complex Environmental Matrices. Molecules 2023, 28, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togun, H.; Basem, A.; Abdulrazzaq, T.; Biswas, N.; Abed, A.M.; Dhabab, J.M.; Mohammed, H.I.; Sharma, B.K.; Paul, D.; Barmavatu, P. Current developments in the use of nanotechnology to enhance the generation of sustainable bioenergy. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachhach, M.; Bayou, S.; El Kasmi, A.; Saidi, M.Z.; Akram, H.; Hanafi, M.; Achak, O.; El Moujahid, C.; Chafik, T. Towards Sustainable Scaling-Up of Nanomaterials Fabrication: Current Situation, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Eng 2025, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zeng, W.; Huang, J. Effects of exposure to carbon nanomaterials on soil microbial communities: A global meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 35, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, U.T.; Velidandi, A. An Overview on the Role of Government Initiatives in Nanotechnology Innovation for Sustainable Economic Development and Research Progress. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.A.; Aurangzeb, J.; Ri, P.D.; Soomro, A.F.; Tae, Y.I. Green Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles Using Black Tea Extract (BTE) to Remove Polyethylene (PE) Microplastics from Water. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, K.; Qin, S.; Liang, B.; Wang, J. Preparation of magnetic Janus microparticles for the rapid removal of microplastics from water. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babalar, M.; Siddiqua, S.; Sakr, M.A. A Novel Polymer Coated Magnetic Activated Biochar-Zeolite Composite for Adsorption of Polystyrene Microplastics: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Regeneration Performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, N.; Hait, S. Enhanced microplastics removal from sewage effluents via CTAB-modified magnetic biochar: Efficacy and environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhur, R.; Kumar, A.; Bux, F.; Kumari, S. Efficient microplastic removal from wastewater using Fe3O4 functionalized g-C3N4 and BNNS: A comprehensive study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhore, R.K.; Kamble, S.B. Nano adsorptive extraction of diverse microplastics from the potable and seawater using organo-polyoxometalate magnetic nanotricomposites. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Alomar, T.S.; Hussain, S.; Shehzad, F.K.; Munawar, K.S.; AlMasoud, N.; Ammar, M.; Asif, H.M.; Sohail, M.; Ajmal, M. Polyoxometalate Based Ionic Liquids Reinforced on Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Sustainable Solution for Microplastics and Heavy Metal Ions Elimination from Water. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 110941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lin, X.; You, X.; Xue, N.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Y. Ultrahigh-Efficiency and Synchronous Removal of Microplastics-Tetracycline Composite Pollutants via S-Scheme Core-Shell Magnetic Nanosphere. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, B.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, X.; Li, Z. Adsorption efficiency and in-situ catalytic thermal degradation behaviour of microplastics from water over Fe-modified lignin-based magnetic biochar. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Subramani, K. Chapter 21—Nanodiagnostics in Microbiology and Dentistry. In Emerging Nanotechnologies in Dentistry; Subramani, K., Ahmed, W., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies, William Andrew Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhu, F.; Gan, A.S.; Mohan, B.; Dey, K.K.; Xu, K.; Huang, G.; Cui, J.; Solovev, A.A.; Mei, Y. Towards the next generation nanorobots. Next Nanotechnol. 2023, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Li, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, W.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, H. Are micro/nanorobots an effective solution to eliminate micro/nanoplastics in water/wastewater treatment plants? Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 949, 175153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Chen, C.; Oral, C.M.; Sevim, S.; Golestanian, R.; Sun, M.; Bouzari, N.; Lin, X.; Urso, M.; Nam, J.S.; et al. Roadmap on Micro/Nanomotors. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 24174–24334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancik-Prochazkova, A.; Ariga, K. Nano-/Microrobots for Environmental Remediation in the Eyes of Nanoarchitectonics: Toward Engineering on a Single-Atomic Scale. Research 2025, 8, 0624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patiño Padial, T.; Chen, S.; Hortelão, A.C.; Sen, A.; Sánchez, S. Swarming intelligence in self-propelled micromotors and nanomotors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xie, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J. Swarm Autonomy: From Agent Functionalization to Machine Intelligence. Advanced Materials 2025, 37, e2312956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song, S.J.; Kim, J.; Gabor, R.; Zboril, R.; Pumera, M. Magnetically Driven Living Microrobot Swarms for Aquatic Micro- and Nanoplastic Cleanup. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 27259–27269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, X.; Ren, L.; Guan, J.; Pumera, M. Reconfigurable Magnetic Liquid Metal Microrobots: A Regenerable Solution for the Capture and Removal of Micro/Nanoplastics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, W.; Fan, X.; Tian, C.; Sun, L.; Xie, H. Cooperative recyclable magnetic microsubmarines for oil and microplastics removal from water. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.; Occhicone, A.; De Gregorio, E.; Ricciotti, L.; Cioffi, R.; Ferone, C.; Tarallo, O. Geopolymer-based composite and hybrid materials: The synergistic interaction between components. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 44, e01404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G.K.M.; Kinuthia, J.M.; Oti, J.; Adeleke, B.O. Geopolymer Chemistry and Composition: A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis, Reaction Mechanisms, and Material Properties—Oriented with Sustainable Construction. Materials 2025, 18, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madirisha, M.M.; Ikotun, B.D.; Onyari, E.K. Turning the tide on microplastic pollution: Leveraging the potential of geopolymers for mitigation. Environ. Res. 2025, 272, 121182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, M.; Ussia, M.; Pumera, M. Breaking Polymer Chains with Self-Propelled Light-Controlled Navigable Hematite Microrobots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zheng, B.; Lin, X.; You, X.; Jia, Q.; Xue, N. Efficient and stable extraction of nano-sized plastic particles enabled by bio-inspired magnetic “robots” in water. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 368, 125501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.; Goh, Z.; Mogan, T.R.; Ng, L.S.; Das, S.; Li, H.; Lee, H.K. Magnetic Hydrogel Microbots for Efficient Pollutant Decontamination and Self-Catalyzed Regeneration in Continuous Flow Systems. Small 2024, 31, 2101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Cai, X.; Yu, T. Low-Energy Photoresponsive Magnetic-Assisted Cleaning Microrobots for Removal of Microplastics in Water Environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 61899–61909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Niu, F.; Geng, J. Microplastic removal from water using modified maifanite with rotating magnetic field affected. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Geng, J.; Qu, X.; Niu, F.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Experimental study on enhanced magnetic removal of microplastics in water using modified maifanite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Gu, X.; Xuan, G.; Wu, H.; Li, S. Efficient microplastic removal in aquatic environments using iron–nitrogen co-doped layered biocarbon materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, D.; Yuan, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, X. Magnetically steerable iron oxides–manganese dioxide core–shell micromotors for organic and microplastic removals. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 588, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhou, L.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Ao, Z.; Wang, S. Degradation of Cosmetic Microplastics via Functionalized Carbon Nanosprings. Matter 2019, 1, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, R.A.; Hadibarata, T.; Niculescu, A.G.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Grumezescu, A.M. Nanomaterials for Persistent Organic Pollutants Decontamination in Water: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowiec, B. Nanowaste in the aquatic environment – threats and risk countermeasures. Desalin. Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremia, E.; Muscari Tomajoli, M.T.; Murano, C.; Petito, A.; Fasciolo, G. The Impact of Micro- and Nanoplastics on Aquatic Organisms: Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress and Implications for Human Health—A Review. Environments 2023, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeszhan, Y.; Bexeitova, K.; Yermekbayev, S.; Toktarbay, Z.; Lee, J.; Berndtsson, R.; Azat, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: Materials, Mechanisms, Practical Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Water 2025, 17, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengul, A.B.; Asmatulu, E. Toxicity of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1659–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, N.; Jeevanandham, S.; Ramasundaram, S.; Oh, T.H.; Selvan, S.T. Recent Advancements in Multimodal Chemically Powered Micro/Nanorobots for Environmental Sensing and Remediation. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, L.; Pan, Y.; Lu, H.; Haleem, A.; Pan, J. Magnetic-driven metal–organic framework nanorobots for the coupling engineering of electronic waste treatment and environmental remediation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, I.; Awang, N.A.; Halim, H.B.; Ikechukwu, O.S.; Jusoh, A.F. Extraction and analytical methods of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Isolation patterns, quantification, and size characterization techniques. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alegre, R.; Durán-Videra, S.; Carmona-Fernández, D.; Pérez Megías, L.; Andecochea Saiz, C.; You, X. Comparative Assessment of Protocols for Microplastic Quantification in Wastewater. Microplastics 2025, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Su, G.; Zhang, M.; Wen, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Propulsion Mechanisms in Magnetic Microrobotics: From Single Microrobots to Swarms. Micromachines 2025, 16, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallek, M.; Barcelo, D. Assessment of removal technologies for microplastics in surface waters and wastewaters. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 49, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Cai, S.; Wang, Z.; Ge, Z.; Yang, W. Magnetically driven microrobots: Recent progress and future development. Mater. Des. 2023, 227, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farale, H.; Sreevidhya, K.B.; Bathinapatla, A.; Kanchi, S. Impact of plastic contaminants on marine ecosystems and advancement in the detection of micro/nano plastics: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetam, S. Nano revolution: Pioneering the future of water reclamation with micro-/nano-robots. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kong, F.; Li, X.; Shen, J. Artificial intelligence in microplastic detection and pollution control. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Duan, N.; Song, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Geng, Y.; Wang, X. Efficient Removal of Micro-Sized Degradable PHBV Microplastics from Wastewater by a Functionalized Magnetic Nano Iron Oxides-Biochar Composite: Performance, Mechanisms, and Material Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, M.M.; Uddin, M.K.; Kazi, J.U. Advances in machine learning for the detection and characterization of microplastics in the environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalatzis, D.; Katsafadou, A.I.; Katsarou, E.I.; Chatzopoulos, D.C.; Kiouvrekis, Y. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for the Rapid Identification and Characterization of Ocean Microplastics. Microplastics 2025, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, H.; Gaur, A.; Singh, N.; Selvaraj, M.; Karnwal, A.; Pant, G.; Malik, T. Artificial intelligence-driven detection of microplastics in food: A comprehensive review of sources, health risks, detection techniques, and emerging artificial intelligence solutions. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, S.R.; Manchu, M.; Felsy, C.; Joselin, K.M. Microplastic predictive modelling with the integration of Artificial Neural Networks and Hidden Markov Models (ANN-HMM). J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, J. AI-assisted Microplastics Removal. J. Neuromorphic Intell. 2025, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Rani, A.; Khan, J.; Pandey, S.; Nand, B.; Singh, P.; Pandey, G. A comprehensive overview of AI–nanotech convergence for a resilient future. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matavos-Aramyan, S. Addressing the microplastic crisis: A multifaceted approach to removal and regulation. Environ. Adv. 2024, 17, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Briceño, S.; Arevalo-Fester, J.E.; Fierro-Sanchez, I.A. Sustainable Magnetic Nanorobots for Microplastics Remediation. Microplastics 2025, 4, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040097

Briceño S, Arevalo-Fester JE, Fierro-Sanchez IA. Sustainable Magnetic Nanorobots for Microplastics Remediation. Microplastics. 2025; 4(4):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040097

Chicago/Turabian StyleBriceño, Sarah, José Eduardo Arevalo-Fester, and Ivan Andres Fierro-Sanchez. 2025. "Sustainable Magnetic Nanorobots for Microplastics Remediation" Microplastics 4, no. 4: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040097

APA StyleBriceño, S., Arevalo-Fester, J. E., & Fierro-Sanchez, I. A. (2025). Sustainable Magnetic Nanorobots for Microplastics Remediation. Microplastics, 4(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040097