Abstract

Biodegradable waste is commonly treated as a problem to be managed, but it can be a valuable resource when considered within a circular bioeconomy perspective. This article develops a practical and systems-based frame work for integrating biodegradable waste, ranging from municipal food scraps to wastewater biosolids, into valuable resources. It explores real-world strategies for transforming waste into value-added products, including composting, anaerobic digestion, biochemical conversion, and the creation of bio-based materials. The review also highlights key drivers and barriers, including technical, regulatory, and social factors, which shape the feasibility and impact of circular solutions. A visual model illustrates the full cycle, from identifying waste streams to reintegrating recovered resources. The paper also highlights case studies from Toronto, Milan and Brazil as examples of successful implementation. Overall, this paper emphasizes a pragmatic yet regenerative shift toward organic resource recovery aligned with sustainability and decarbonization goals.

1. Introduction

Biodegradable waste streams are increasing at a significant rate across the globe. This growth is largely driven by rising populations, changing dietary and consumption patterns, and expanding industrial and agricultural activity. These organic waste streams include food scraps, agricultural residues, food processing by-products, and biosolids from wastewater treatment. Although often overlooked or discarded, they hold significant value, containing nutrients, organic carbon, and bioenergy potential that can be recovered. When mismanaged, biodegradable waste contributes to methane emissions, soil and water pollution, and increased pressure on landfills. In contrast, when properly managed, it can be transformed into a sustainable resource for producing compost, biogas, bio-based materials, and soil amendments [1,2].

Unlocking this potential requires a shift in mindset, where organic waste is seen not as a disposal problem, but as a resource. The circular bioeconomy offers such a framework, reframing waste as a feedstock for regeneration and local resilience. It emphasizes the use of renewable biomass, the cascading valorization of organic matter, and the reintegration of outputs into local systems [3,4]. This paper explores how biodegradable waste can act as a catalyst for building circular, sustainable solutions at the community and regional levels. It presents a systems-based framework and outlines key valorization pathways, while also discussing enabling conditions, barriers to adoption, and real-world case examples that illustrate feasibility and impact.

Scope and Approach

This article presents a narrative review that synthesizes recent peer-reviewed publications and case studies focused on the recovery and reuse of biodegradable waste within the framework of the circular bioeconomy. The aim is to explore practical strategies and emerging models that support the transition from linear to circular organic waste management systems.

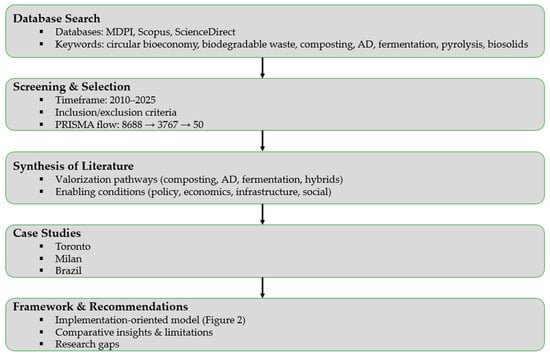

Relevant sources were identified through comprehensive searches of academic databases including MDPI, Scopus, and ScienceDirect (Figure 1). While these databases provided a strong foundation for the review, it is acknowledged that relevant literature from other sources (e.g., Web of Science, SpringerLink, or gray literature) may have been excluded. This limitation may influence the comprehensiveness of the evidence base and should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Figure 1.

Study framework showing the flow from database search and screening, through synthesis of technologies and enabling conditions, to case study analysis and framework recommendations.

Search terms included “circular bioeconomy,” “biodegradable waste,” “anaerobic digestion,” “biosolids,” and “bio-based materials.” Studies were selected based on their relevance to real-world applications, policy implications, and system integration, particularly those addressing municipal solid waste, agricultural residues, food processing by-products, and biosolids from wastewater treatment. Inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2025 that examined biodegradable waste valorization within a circular bioeconomy framework. Searches were last updated in August 2025. Exclusion criteria included studies outside this timeframe, those limited to purely theoretical or laboratory-scale investigations without policy or system context, and publications not directly related to organic waste valorization pathways.

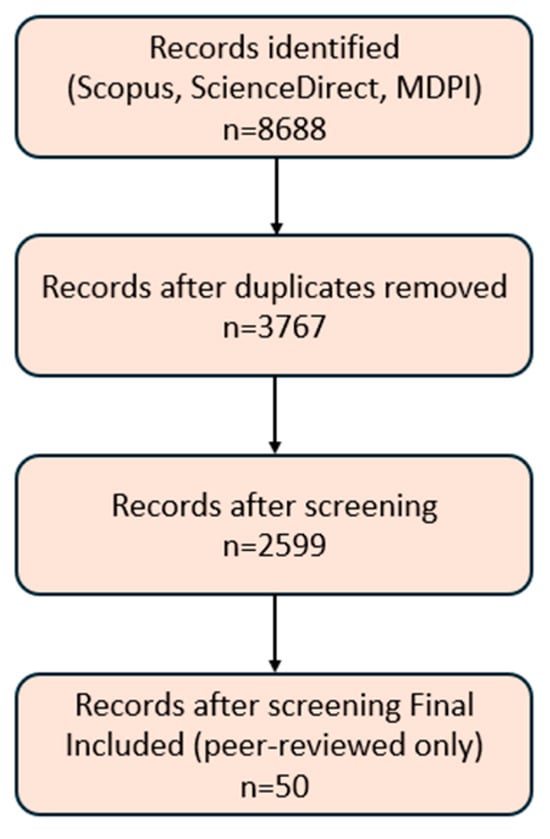

In total, 8688 records were retrieved across Scopus, ScienceDirect, and MDPI databases. After removing duplicates, 3767 records remained for screening. Following title/abstract and full-text review, 50 peer-reviewed articles were included in the final synthesis. Gray literature (policy documents, municipal reports, and industry case studies) was used to provide policy and implementation context but was not included in the PRISMA counts. The article selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2), and the database results are detailed in Table 1. This review followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The study was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO or any other systematic review registry, as registration is not mandatory for narrative or scoping reviews in this field.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, screening, and inclusion of studies.

Table 1.

Summary of database search results and article inclusion process for the scoping review.

To provide additional transparency, the 50 included peer-reviewed studies were categorized by their primary focus area based on keywords and research objectives. The distribution is presented in Table 2, which highlights composting, anaerobic digestion, fermentation/biochemical conversion, hybrid/emerging technologies, and policy/market integration.

Table 2.

Keyword/Topic distribution of included studies.

In this context, the article aims to explore current progress, identify practical barriers and opportunities, and contribute to the broader conversation on sustainable waste valorization and circular system design.

In this article, “processes” refers specifically to valorization pathways (composting, anaerobic digestion, fermentation, and hybrid systems) together with enabling system conditions (policy, economics, infrastructure, and social acceptance) that support their implementation within a circular bioeconomy.

2. Framing the Circular Bioeconomy

This is an emerging economic model that integrates renewable biological resources and circularity principles to create regenerative, closed-loop systems. Unlike traditional linear systems that rely on fossil inputs and lead to waste accumulation, the circular bioeconomy emphasizes biological cycles, such as composting, anaerobic digestion, and fermentation, to reduce environmental impact and restore ecosystem health. It reframes biodegradable waste not as a disposal issue, but as a resource for producing energy, nutrients, and bio-based materials, thereby unlocking new opportunities for innovation, local resilience, and sustainable development [5,6].

The circular bioeconomy framework aligns with the principles of regenerative systems, emphasizing soil health, biodiversity, and local economic resilience. In this context, biodegradable waste is intentionally redirected into processes that produce renewable energy, soil amendments, feedstocks, or bio-based materials. Unlike linear systems that result in resource depletion and environmental degradation, circular bioeconomy encourages innovation across sectors by reconnecting biological resources with new forms of value creation.

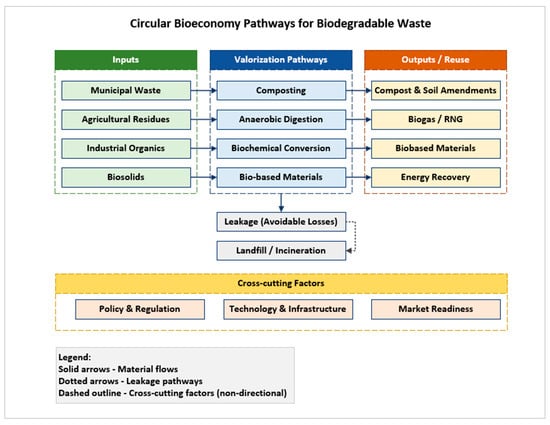

To deepen understanding of how this model functions in practice, Figure 3 presents a visual representation of the circular bioeconomy model, highlighting its key phases and material flows. The following features characterize the approach:

Figure 3.

Circular bioeconomy framework linking organic waste inputs (food waste, agricultural residues, biosolids) to enabling conditions (policy and regulation, social acceptance and participation, infrastructure and technology, finance and markets), core valorization pathways (composting, anaerobic digestion, fermentation, and hybrid systems), and key outputs (biogas/RNG, bio-based materials, compost and soil products). Solid arrows represent material and energy flows; dashed arrows indicate enabling influences and feedback loops that shape pathway selection and market adoption. Case studies from Toronto, Milan, and Brazil illustrate different pathway, enabling environment combinations, as discussed in Section 5.

- Using renewable biomass sustainably and efficiently

- Extending the lifespan and value of organic materials through cascading use

- Prioritizing biological conversions like composting, anaerobic digestion, and fermentation

- Reconnecting outputs with local sectors (e.g., agriculture, energy, manufacturing)

- Supporting uptake through regulation, incentives, and community engagement

This systems-based perspective also enables more flexible, decentralized approaches to resource management, where local actors, including municipalities, farms, and small industries, can adapt circular bioeconomy models to suit their own material flows, infrastructure, and community priorities. To further clarify the distinctiveness of this model, we expand on its defining features:

While similar process-flow diagrams appear in the literature, the framework presented here synthesizes technologies, enabling conditions, and case study evidence into an implementation-oriented model. Its contribution lies not in proposing a new theoretical structure, but in integrating technical, policy, economic, and social dimensions into a single operational framework that can guide planning, evaluation, and policy design.

Figure 3 illustrates how biodegradable materials move through a circular bioeconomy system, beginning with input mapping and source segregation and continuing through various valorization pathways such as composting, anaerobic digestion, fermentation, and bio-based material production. These processes generate outputs including renewable energy, soil amendments, and reusable materials, which are reintegrated into local systems through feedback loops that support a regenerative, closed-loop approach. In practice, input mapping involves identifying, quantifying, and characterizing waste streams such as municipal organics, agricultural residues, and industrial by-products, based on their volume, composition, and seasonal patterns. Source segregation then focuses on removing contaminants like plastics and metals to maintain feedstock quality and ensure suitability for downstream processing. The choice of valorization pathway depends on the nature of the input material, processing conditions, and desired end use, while feedback mechanisms enable continuous improvement and adaptive system design. Together, these interconnected steps form the operational foundation of a circular bioeconomy model [7,8].

Valorization pathways encompass the biological and biochemical processes used to transform these segregated organic inputs into valuable products. Common techniques include composting, anaerobic digestion, and fermentation, all of which convert organic waste into renewable energy, nutrient-rich soil amendments, or bio-based materials. The selection of a specific pathway depends on factors such as the type and consistency of the input material, processing conditions, and intended end use [5,9].

System integration and feedback complete the cycle by reinserting recovered outputs into local systems, such as applying compost to farmland, feeding biogas into municipal energy grids, or incorporating bio-based materials into manufacturing. This phase also involves feedback mechanisms that inform stakeholders and enable continuous improvement, supporting the adaptive, regenerative goals of circularity and local resilience [2,7].

Together, these three interconnected phases form the operational foundation of the circular bioeconomy model. However, for these phases to be truly effective and sustainable, their implementation must be guided by a set of core principles that shape planning, decision-making, and policy at every level [2].

As circular models gain global momentum, it becomes increasingly important to ground them in shared values. The following principles serve as the backbone of successful circular bioeconomy strategies:

- Sustainable biomass use: The model emphasizes the use of renewable, non-competing biomass sources such as agricultural residues, food scraps, and biosolids. This approach helps prevent the diversion of valuable resources away from food systems or natural ecosystems [5,10,11].

- Cascading valorization: Organic materials are managed in a sequence that captures value as much as possible before final disposal. For instance, food waste may first undergo protein extraction, followed by anaerobic digestion of the remaining material, and ultimately, the digestate may be used as compost [5,10].

- Biological processing: Preference is given to biological and nature-based processes like composting, fermentation, and anaerobic digestion. These methods align with ecological systems and minimize the risk of producing harmful byproducts [6,12,13].

- Cross-sector reintegration: Outputs such as compost, biogas, or bio-based plastics are returned to agriculture, energy networks, or manufacturing, reinforcing local circular economies and reducing dependency on external inputs [5].

- Policy and community alignment: Success hinges on policies that support innovation and uptake, such as landfill bans, tax incentives, or green public procurement. Equally, public engagement in waste sorting and acceptance of circular products is vital for closing the loop [14].

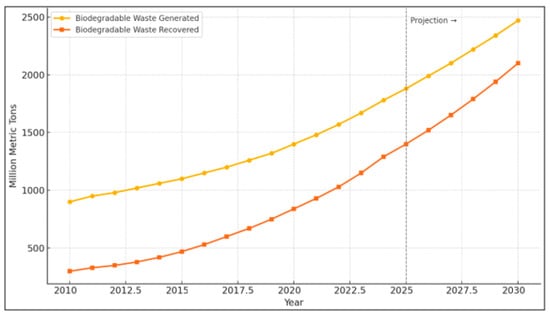

To illustrate the growth and relevance of this model, Figure 4 presents a global trend in biodegradable waste generation and recovery between 2010 and 2030. In Figure 4, solid lines represent reported or estimated historical data up to 2024, while dotted lines indicate projected trends from 2025 to 2030. The figure is based on synthesized data from publicly available international reports, including the World Bank’s ‘What a Waste’ series and the FAO’s statistical yearbooks. While actual values vary by region, the upward trend reflects the increasing volume of waste and the parallel, though slower, development of recovery infrastructure. In high-income regions such as the European Union, strict landfill diversion policies and financial incentives have driven higher recovery rates, whereas North America shows moderate but steady progress through municipal organics programs and renewable energy initiatives. By contrast, many low- and middle-income countries continue to face systemic barriers, including limited collection infrastructure, financing gaps, and reliance on informal waste sectors, which constrain recovery levels despite rising waste generation. These regional disparities also highlight uncertainties in future projections, as outcomes will depend on evolving policy frameworks, infrastructure investment, and household participation in source separation. Recognizing these differences is important for tailoring circular bioeconomy strategies to local conditions rather than adopting one-size-fits-all approaches [15].

Figure 4.

Global trends in biodegradable waste generation and recovery (2010–2030). Solid lines represent reported or estimated historical data through 2024. Dotted lines indicate projections from 2025 to 2030, extrapolated from growth trends published by the World Bank (2018) and FAO (2023). Values are regionally variable and presented as illustrative trends; actual recovery rates differ by context [15,16].

3. Valorization Pathways for Biodegradable Waste

This section synthesizes findings from the literature, comparable to a literature review in structure. The success of any valorization strategy depends on both the technology applied and the characteristics of the feedstock, including volume, composition, moisture content, and contamination levels. Matching these parameters with the most suitable conversion pathway is essential for optimizing recovery and ensuring marketable outputs [17]. Once feedstocks are properly identified and preprocessed, they can be directed to various biological and biochemical pathways, each offering unique outputs and advantages. The most common and practical approaches include:

3.1. Composting

Composting is one of the most accessible and widely adopted methods for valorizing biodegradable waste, particularly food scraps, yard trimmings, agricultural residues, and certain biosolids. It involves the aerobic decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms, producing a stable, nutrient-rich material known as compost. When managed properly, composting not only diverts waste from landfills but also enhances soil health, supports local food systems, and contributes to carbon sequestration [13].

The composting process typically occurs in three phases: an initial thermophilic phase, where temperatures rise and pathogens are destroyed, a mesophilic phase, where microbial activity breaks down complex organic materials, and a final maturation phase, where the compost stabilizes and humifies. The process can be managed at various scales, from household bins and community compost sites to industrial windrow, aerated static pile, and in-vessel systems [13,18].

Composting is particularly effective for materials with a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, low moisture content, and minimal contamination. Pre-sorting and decontamination are essential to prevent plastics, metals, and other non-biodegradable items from compromising compost quality. When biosolids are used, regulations typically require additional monitoring to verify that heavy metal and pathogen levels remain within safe limits.

The resulting compost can be used as a soil amendment in agriculture, landscaping, urban greening, and erosion control. It improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient content, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. Composting is also recognized as a climate mitigation strategy, as it reduces methane emissions from landfills and can contribute to long-term soil carbon storage.

Despite its benefits, composting faces several challenges. These include odor and leachate management, space and infrastructure requirements, and the need for public compliance with source separation rules. In some regions, inconsistent compost quality and contamination have limited market uptake. Nonetheless, municipal composting programs have expanded in cities such as Toronto [18], and Milan [19], demonstrating that composting can be effectively integrated into broader circular systems.

For example, Toronto’s Green Bin program diverts approximately 122,000 tonnes of residential organic waste annually, contributing to a household diversion rate of 51.7% as of 2024 The collected material is processed at large-scale composting and anaerobic digestion facilities, including the Disco Road and Dufferin Organics Processing Facilities [20,21]. The resulting compost is used in public parks, community gardens, and agricultural applications, helping reduce methane emissions from landfills and closing nutrient loops within the urban ecosystem.

3.2. Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a well-established biological process for valorizing biodegradable waste, particularly high-moisture feedstocks such as food waste, agricultural slurries, wastewater biosolids, and the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. In the absence of oxygen, microorganisms decompose organic matter to produce biogas, primarily methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), along with a nutrient-rich byproduct called digestate [22].

The digestion process typically progresses through four stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis. Systems can be configured as single-stage or two-stage units and operated under mesophilic (around 35 °C) or thermophilic (around 55 °C) conditions. Co-digestion, which combines different organic wastes such as food residues and manure, can improve methane yields, balance nutrients, and enhance process stability [23]. Since feedstock characteristics such as solids concentration, viscosity, and chemical composition directly affect pumping, mixing, and heating requirements, selecting equipment tailored to these conditions is critical for stable AD performance and energy efficiency [23,24]. Improper segregation, however, can introduce plastics, grit, and other contaminants into digesters, which not only lowers process stability but also increases pump wear and energy use, ultimately reducing overall system efficiency.

Beyond its technical operation, AD has already been adopted in several municipalities worldwide, including Canada. In Canada, several municipalities have adopted anaerobic digestion as part of their organic waste management strategies. For example, Toronto’s Disco Road and Dufferin Organics Processing Facilities treat residential green bin waste through anaerobic digestion. The resulting biogas is cleaned and either used to fuel city vehicles or injected into the natural gas grid [25]. Other Canadian cities, including Surrey in British Columbia and Montreal in Quebec, operate similar systems that contribute to local renewable energy generation and nutrient recycling [26,27].

Anaerobic digestion delivers multiple benefits. It reduces dependence on landfilling, recovers energy in the form of biogas, mitigates greenhouse gas emissions, and generates digestate that can be used as a soil amendment or fertilizer substitute. Accordingly, AD represents a key technology within circular bioeconomy strategies aimed at closing material and energy loops [12].

Beyond waste valorization, AD has significant potential to improve energy performance in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Electricity demand in conventional facilities is high, with pumping systems alone accounting for nearly 50% of consumption, typically between 0.4 and 0.6 kWh per cubic meter of treated water. Biogas energy recovery can offset these loads, particularly when paired with modern, high-efficiency equipment. Beyond feedstock characteristics, the energy performance of anaerobic digestion systems depends heavily on the design and efficiency of supporting equipment. Modern submersible and dry-installed centrifugal pumps, optimized for handling high-solids wastewater streams, have shown measurable improvements in hydraulic performance and reductions in lifecycle energy consumption. Similarly, advanced mixing, aeration, and heating systems, when combined with intelligent control technologies, can further reduce operational demand and enhance process stability [28,29]. Integrating biogas recovery with energy-efficient equipment and digital optimization tools strengthens the sustainability of wastewater treatment plants and supports circular economy and climate targets [24,30,31].

Nevertheless, AD technology faces barriers. High upfront capital costs, the need for effective waste segregation to avoid contamination, and regulatory uncertainty regarding digestate use remain significant challenges. Operational complexity and sensitivity to feedstock variability also require robust monitoring and management. Public acceptance, particularly related to odor and siting concerns, can further influence deployment. Despite these barriers, AD continues to expand across Canada and internationally, supported by policy incentives, renewable energy targets, and climate commitments [9].

3.3. Fermentation and Biochemical Conversion

While AD is among the most mature pathways, fermentation offers distinct opportunities for producing higher-value outputs, fermentation and related biochemical conversion processes offer an advanced pathway for transforming biodegradable waste into high-value bio-based products. These methods rely on microbial or enzymatic activity to break down organic substrates into useful compounds such as bioethanol, organic acids, bioplastics (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoates or PHAs), and platform chemicals like lactic acid and succinic acid [32].

Unlike composting or anaerobic digestion, which primarily produce bulk outputs like soil amendments or energy, fermentation targets specific biochemical transformations. These processes are typically applied to homogeneous and carbohydrate-rich feedstocks, including food processing residues, fruit and vegetable waste, and pretreated lignocellulosic biomass. In some cases, fermentation can be integrated with pretreatment steps such as hydrolysis to improve substrate availability and reaction efficiency [33].

The advantages of biochemical conversion include product diversification, higher economic value, and the potential to displace petrochemical-derived materials. However, these systems are generally more sensitive to contamination and require tighter control over pH, temperature, and substrate composition. Additionally, scaling up remains a barrier due to high purification costs and feedstock variability [34].

Despite these challenges, fermentation technologies are an essential part of the circular bioeconomy, especially when integrated into larger waste management frameworks. Their ability to convert organic residues into marketable chemicals and materials supports innovation in green manufacturing and resource recovery.

3.4. Emerging or Hybrid Approaches

Beyond conventional methods like composting, anaerobic digestion, and fermentation, a growing set of emerging and hybrid technologies is expanding the potential for biodegradable waste valorization. These approaches often aim to address the limitations of traditional systems by improving energy efficiency, enabling resource recovery from more complex feedstocks, or integrating multiple processes into a single platform.

One example is pyrolysis, a thermochemical process that decomposes organic materials at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. Pyrolysis can convert agricultural waste, food scraps, and biosolids into bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Biochar is gaining attention for its carbon sequestration potential and soil-enhancing properties. While pyrolysis systems require higher energy input and careful emission controls, they offer a promising route for hard-to-digest or contaminated organic fractions [9,35].

Another technique is hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), which uses high temperature and pressure in a water-rich environment to convert wet biomass into a crude bio-oil. HTL is especially suited to high-moisture feedstocks like algae, sewage sludge, or food processing waste. Compared to pyrolysis, HTL is less sensitive to moisture content and may be more efficient for treating slurries or liquids. However, technology is still in the early stages of commercialization and requires further optimization for scale-up [36].

Hybrid systems are also emerging that combine biological and thermochemical processes. For example, anaerobic digestion followed by thermal treatment of digestate can increase energy recovery and reduce final waste volume. Some pilot projects have explored coupling anaerobic digestion with algae cultivation, using the carbon dioxide and nutrients from biogas systems to grow algae that can be harvested for biofuel, feed, or bio-based chemicals.

In Canada, several research groups are investigating such integrated approaches. The National Research Council and academic institutions have tested hybrid models for converting municipal sludge and food waste into multiple outputs, including fuels, fertilizers, and carbon-rich materials. These innovations support circular bioeconomy principles by maximizing value extraction while minimizing residuals [23].

Despite their promise, emerging and hybrid technologies face economic, regulatory, and technical challenges. Many systems are still at the pilot or demonstration stage, and require stable feedstock supplies, skilled operation, and clear end-use markets to become viable. Nevertheless, their potential to unlock new forms of value from organic waste makes them an important area for continued investment and research.

3.5. Comparative Summary of Valorization Pathways

Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics of the four main biodegradable waste valorization approaches discussed in this review. Each pathway presents unique advantages and constraints depending on local conditions, policy support, feedstock availability, and desired outcomes [37,38].

Table 3.

Comparative trade-offs and contextual considerations for main valorization pathways.

Life cycle assessments (LCAs) comparing composting and anaerobic digestion frequently yield divergent results. Studies that credit avoided landfill methane emissions and displaced grid energy often favor anaerobic digestion, while those emphasizing soil carbon benefits, compost quality, and nutrient recycling may find composting more advantageous. These discrepancies highlight that performance rankings are highly context-specific and depend on methodological boundaries and assumptions rather than the inherent superiority of one pathway.

In addition to technical parameters, selecting an appropriate valorization strategy also depends on environmental performance and operational feasibility. Table 4 and Table 5 provide a comparative overview of the greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation potential, resource efficiency, and economic considerations of each pathway [39,40].

Table 4.

Indicative economic considerations of valorization pathways (relative ranges).

Table 5.

Economic and operational considerations for valorization methods.

While the technical and economic profiles of each valorization pathway are important, their real-world adoption depends on a broader set of enabling conditions. These include supportive policy frameworks, infrastructure readiness, stakeholder engagement, and public participation. The following section explores these factors in more detail, highlighting both barriers and opportunities for scaling circular bioeconomy solutions [37,38].

4. Enabling Conditions and Barriers

The successful implementation of circular bioeconomy strategies for biodegradable waste relies on more than technical feasibility alone. Translating valorization pathways into practice requires enabling conditions across policy, economic, technological, and social dimensions. Even the most efficient systems can fail without supportive regulation, reliable infrastructure, market incentives, or community engagement. This section outlines the key external factors that influence the deployment and scaling of circular solutions, drawing on examples from Canada and beyond.

4.1. Policy and Regulatory Environment

Policy frameworks play a critical role in shaping how biodegradable waste is managed and valorized. Regulations determine what materials can be collected, how they must be treated, and what end uses are permitted or incentivized. Well-designed policies can accelerate the adoption of composting, anaerobic digestion, or biochemical conversion by creating legal certainty, encouraging investment, and setting performance targets.

In Canada, policies vary by province and municipality. Some regions, such as British Columbia and Ontario, have implemented landfill bans or restrictions on organic waste, which encourage source separation and diversion. National strategies, such as Canada’s Zero Plastic Waste Agenda and clean fuel standards, indirectly support the use of organic residues for bioplastics and bioenergy production. However, regulatory gaps still exist, particularly around the classification and application of digestate or compost derived from biosolids, which can hinder product uptake in agriculture [26,41].

Permitting and zoning processes also influence project timelines and feasibility. In some cases, overly complex or fragmented approval systems can delay or deter the development of new processing facilities. On the other hand, streamlined permitting, performance-based standards, and integrated waste-resource policies can support innovation while maintaining environmental safeguards.

Ultimately, regulatory clarity, consistency, and alignment with circular economy goals are essential for unlocking the full potential of biodegradable waste valorization [41].

4.2. Economic Incentives and Market Demand

Economic drivers play a pivotal role in determining whether circular bioeconomy solutions are viable at scale. While many valorization technologies are technically proven, their implementation often hinges on financial feasibility, return on investment, and the availability of stable end markets for recovered products [42].

Incentive mechanisms such as carbon pricing, tipping fees, green procurement policies, and renewable energy credits can make composting, anaerobic digestion, and biochemical conversion more attractive to both public and private stakeholders. For example, landfill tipping fees in Canadian provinces like Ontario can exceed CAD 100 per tonne, creating a cost-saving incentive to divert organic waste to processing facilities [43]. Feed-in tariffs or renewable natural gas (RNG) incentives further improve the financial case for anaerobic digestion by providing revenue for biogas injection or vehicle fuel applications [44].

Market demand for outputs like compost, digestate, biogas, and bio-based products is equally important. While compost has long been used in landscaping and agriculture, price and quality inconsistencies can limit its commercial uptake. Similarly, digestate faces barriers in terms of regulation, public perception, and transportation costs. High-value products such as bioplastics or organic acids from fermentation processes have growing markets but require consistent quality and competitive pricing to replace fossil-derived alternatives [42,45].

Emerging voluntary carbon markets and ESG (environmental, social, and governance) frameworks may create new revenue streams for circular bioeconomy projects, especially those that contribute to methane reduction or soil carbon storage. Public and private procurement policies that favor circular or low-carbon materials can also help build stable demand for recovered products [45].

To scale these solutions, economic tools must go beyond one-time grants or pilot funding. Long-term market development, price stabilization mechanisms, and ecosystem-based business models are essential to ensure that circular valorization pathways are financially sustainable over time.

4.3. Infrastructure and Technology Access

The availability and suitability of infrastructure is a critical factor influencing the success of biodegradable waste valorization. While the technologies for composting, anaerobic digestion, and fermentation are well established, their deployment depends on the presence of supporting systems such as collection networks, preprocessing facilities, utilities, transportation logistics, and end-product distribution channels [3,7]

In many Canadian municipalities, especially in urban centers like Toronto and Vancouver, organic waste collection programs are already in place and supported by centralized processing infrastructure. However, in smaller or rural communities, gaps in collection services, processing capacity, or transportation options can limit access to valorization technologies. For example, the viability of anaerobic digestion may be constrained by the absence of co-digestion partners, grid injection points for biogas, or adequate feedstock volumes [46].

Technology access is also shaped by knowledge, financing, and workforce capacity. Advanced systems, such as high-rate anaerobic digesters or biochemical reactors, require specialized expertise for design, operation, and maintenance. Small and medium-sized enterprises or municipalities may face challenges in accessing these technologies due to limited technical support, capital funding, or economies of scale [5].

Modular and decentralized systems offer one potential solution. For instance, small-scale digesters or community composting units can serve localized needs with lower capital investment. Similarly, containerized or mobile fermentation units are being developed to process food waste on-site in commercial or institutional settings. In addition, supporting technologies such as submersible or variable-speed pumps, when properly selected and hydraulically optimized, can significantly improve the efficiency and scalability of decentralized systems [24]. These innovations can extend technology access in regions where centralized infrastructure is not practical [13].

To bridge the infrastructure gap, partnerships between municipalities, utilities, technology providers, and private investors are essential. Pilot projects, shared processing hubs, and regional planning can also help optimize resource flows and make valorization technologies more accessible and cost-effective.

4.4. Social Acceptance and Behavioral Factors

Public perception, community engagement, and behavioral practices significantly influence the success of biodegradable waste valorization strategies. Even with strong policies and advanced technologies, circular solutions often depend on consistent public participation in source separation, acceptance of recovered products, and support for local facilities.

One of the key barriers to effective valorization is contamination at the source. When households or businesses place non-organic or improperly sorted materials in green bins, it reduces the quality and usability of the feedstock for composting or anaerobic digestion. Addressing this challenge requires sustained public education, clear labeling, and feedback systems that help users understand the environmental impact of their choices [47].

Odor concerns, traffic, and perceived health risks can also generate opposition to the siting of composting or digestion facilities, particularly in urban or peri-urban areas. Transparent planning processes, odor control measures, and communication with residents can reduce resistance and build trust. Community-based or cooperative composting programs can further enhance acceptance by creating local ownership and visibility [48].

In some cases, there may also be skepticism about the use of recovered products, especially when biosolids or digestate are applied to agricultural land. Promoting product standards, third-party certification, and evidence-based communication about safety and benefits is essential for overcoming these concerns.

Importantly, circular bioeconomy strategies can benefit from aligning with broader sustainability narratives that resonate with the public, such as climate action, food security, and local economic development. When citizens see tangible value in their participation, whether through lower waste fees, cleaner communities, or access to compost for gardening, they are more likely to support and sustain circular practices [49].

5. Case Studies from Practice

This section highlights real-world examples of how circular bioeconomy principles are being applied to manage biodegradable waste. Each case illustrates a different valorization strategy adapted to local conditions, policies, and community needs. These cases function as illustrative “results,” demonstrating how circular bioeconomy processes operate in practice.

5.1. Toronto’s Circular Organics Program

One of the most comprehensive municipal examples of the circular bioeconomy is Toronto. Launched in 2002 and expanded city-wide by 2006, the Green Bin program currently serves about 460,000 households and most multi-residential buildings [20]. With expansions anticipated to raise total capacity to 140,000 t/year by 2026, Toronto’s facilities currently divert 130,000 tonnes annually (55,000 t at Dufferin and 75,000 t at Disco Road) [50,51]. More than 20,000 tonnes of Class AA compost are produced annually from anaerobic digestion (AD) residuals for municipal parks, community gardens, and agriculture [50]. Since 2021, the Dufferin facility has avoided 5068 tonnes CO2e and produced 1.87 million m3 of renewable natural gas (RNG) annually [50]. By 2025, combined output from Dufferin and Disco Road is projected at 6.24 million m3 RNG/year (232,000 GJ, 13,500 t CO2e avoided), with expansions at Green Lane and Keele Valley bringing the pipeline to 36.37 million m3 RNG annually by 2028, enough to fulfill 91.9% of the city’s TransformTO 2030 target of 1.5 million GJ/year [20].

Toronto has invested heavily, with more than CAD 849 million in capital expenditures (CAPEX, long-term infrastructure investments) planned between 2022 and 2031, including CAD 130 million for a new AD facility and CAD 275 million for landfill and transfer station upgrades [52]. Annual operating expenditures (OPEX, ongoing facility and program costs) exceed CAD 400 million. While avoided landfill costs, methane reductions, RNG revenue, and compost benefits help offset expenses, challenges remain. Diversion rates are still 50–55%, constrained by public participation and seasonal variability [20]. Reviews also note research gaps in LCA comparisons, biogas upgrading performance, and sensitivity analyses [53]. Despite these issues, Toronto demonstrates a functioning closed-loop system, converting organics into clean energy and soil amendment through integrated infrastructure and public participation.

5.2. Milan, Italy—Food Waste Sorting and Composting at Scale

Milan is regarded as a European leader in urban organic waste management [54]. Since 2014, the city has implemented a mandatory food waste separation program for all homes, schools, and businesses, supported by door-to-door collection and intensive public education [54,55,56]. Within three years, Milan achieved a food waste capture rate of over 90%, diverting about 100 kg per person per year (~600,000 t/year) [54].

Small kitchen bins and biodegradable liners are provided to residents, with collection occurring two to three times weekly to reduce odor and contamination. Life-cycle assessments (LCAs) show composting raw food waste creates a climate burden of ~155 kg CO2e/ton, while composting digestate from AD results in a net savings of −37 kg CO2e/ton and 70% lower energy use [57]. Depending on contamination control, net GHG savings range from 50 to 120 kg CO2e/ton [57]. Digestate compost also shows lower heavy metal content, enhancing agricultural value Plastic contamination, averaging 3–5% by weight (reduced to 0.4–0.6% after sieving), remains a challenge, adding 12–15 €/ton to operating expenditures (OPEX) [54,58].

Trade-offs are evident: composting is inexpensive but energy-poor, while AD requires higher capital expenditures (CAPEX) and complex operations but yields renewable energy and reduces methane emissions. Milan balances OPEX and CAPEX through public–private partnerships (AMSA/A2A). Social and environmental impacts are significant, with reduced GHG emissions, improved soils, and strong household participation. Gaps remain in comparing LCA results across systems, digestate management, and scaling advanced options like pyrolysis. Pilot integration of biochar, produced from 40,000 t/year of pruning waste, sequesters over 12,000 t CO2e/year and prevents ~29,300 t CO2e/year of emissions [35]. Production costs are ~EUR 216/t, partly offset by sales and municipal savings. Milan demonstrates how strategic planning, education, and integrated valorization can achieve high diversion and measurable climate gains.

5.3. Brazil—Opportunities and Barriers in a Developing Economy

Brazil produces about 81.8 million tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) annually, 45.3% of which is organic [59]. Approximately 23.6 million tonnes of food are discarded each year [60]. While collection coverage is high (92–93%), only 61% of waste reaches sanitary landfills, the rest is disposed at controlled or illegal sites [59]. Policies like the National Solid Waste Policy (2010) and PLANARES (2020) aim to phase out dumps, expand recycling and composting, and promote energy recovery, but implementation remains limited [61].

Pilot AD plants show promise. A high-solid AD facility treating 0.55 t/day outperformed a wet AD system (15.6 t/day) by using 83 L/t water versus 916 L/t, and producing more solid biofertilizer (100.9 vs. 60.6 kg/t) [59]. A Rio de Janeiro case study estimated landfilling food waste emitted 50,560 t CO2e annually, while AD reduced emissions by ~90%, producing 181.6 t biosolids and 38,549 m3 biogas annually [62].

Barriers include inadequate source separation, limited transfer logistics, low AD and composting capacity, informal sector dependence, and financial constraints, with both capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating expenditures (OPEX) not secured by tariffs or power purchase agreements (PPAs) [63,64]. Market demand for compost, digestate, and RNG remains thin. Policy and regulatory inconsistencies hinder progress. Feasible solutions include decentralized composting, affordable plug-flow digesters for campuses and communities, and PPP models with performance-based tipping fees [64]. Research gaps include regional LCAs, digestate reuse optimization, and detailed economic modeling [59,62].

Despite challenges, Brazil’s scale of organic waste and policy momentum suggest strong potential if infrastructure, financing, and governance barriers can be overcome.

5.4. Comparative Insights

These three cases illustrate contrasting but complementary models:

Toronto: Infrastructure-heavy, centralized, capital-intensive system leveraging AD and RNG upgrading.

Milan: Policy-driven, citizen-engaged, distributed model emphasizing composting, AD, and biochar integration.

Brazil: Early-stage adoption in a developing economy, with systemic barriers but clear opportunities through decentralized and hybrid solutions.

Together, they highlight how local context, policy, infrastructure, social engagement, and financing determines which circular bioeconomy pathways succeed.

5.5. Limitations and Research Gaps

While this framework offers a holistic view of biodegradable waste valorization, several gaps remain. Variability in feedstock composition, limited scalability of some technologies (e.g., fermentation and hybrid systems), and the inconsistent performance of digestate and biochar products in different soil types pose ongoing challenges. Life cycle assessments also produce mixed results depending on system boundaries and local factors, which complicates cross-context comparisons. Conflicting LCA results for composting versus anaerobic digestion remain a key research gap, as outcomes are highly sensitive to assumptions about system boundaries, avoided burdens, and feedstock purity. Further research is needed on decentralized models, real-time monitoring, and policy mechanisms that better integrate social equity and behavioral change in circular strategies.

6. Discussion and Recommendations

The findings of this review highlight the technical diversity and practical adaptability of circular bioeconomy approaches for biodegradable waste. From low-tech composting to high-efficiency anaerobic digestion and emerging hybrid systems, each pathway presents unique opportunities and constraints. However, the effectiveness of these systems depends less on a single “best” technology and more on how well they are aligned with local conditions, infrastructure, policy environments, and public participation.

Case studies from Toronto and Milan demonstrate two successful yet contrasting models. Toronto’s integration of anaerobic digestion, biogas upgrading, and centralized processing reflects a high-investment, infrastructure-led approach. In contrast, Milan’s success has been achieved through behavior-driven policy, frequent collection, and distributed treatment capacity. Both examples underline the importance of aligning technological solutions with institutional capacity and community engagement.

Several cross-cutting insights emerge from this analysis:

- System integration is essential: Technologies should not be evaluated in isolation but as part of broader loops that include collection, preprocessing, valorization, and product reintegration [65].

- Feedstock quality determines system performance: Effective input mapping and source separation are critical for optimizing recovery, reducing contamination, and ensuring marketable outputs [66].

- Policy and economics shape adoption: Stable regulations, landfill diversion mandates, and incentives such as tipping fees or carbon credits can significantly accelerate deployment [14]

- Social acceptance and participation remain key: Public compliance with sorting rules, willingness to use compost or digestate, and trust in local governance all influence outcomes [65].

Looking forward, there is a need for:

- More regionalized solutions, particularly in smaller municipalities or rural areas, where centralized infrastructure may not be feasible [67].

- Integration with climate and soil strategies, linking composting and biochar use with carbon sequestration and regenerative agriculture [68].

- Support for innovation and hybrid systems, including pilot projects that test new combinations of biological and thermochemical approaches [13,68].

- Investment in education and outreach to build a culture of participation and reduce contamination at the source [13].

Ultimately, transitioning to a circular bioeconomy for biodegradable waste requires more than the deployment of technology. It involves redesigning systems to prioritize regeneration, local value creation, and long-term resilience [69].

7. Conclusions

Biodegradable waste, long treated as a disposal challenge, holds untapped potential as a catalyst for circular and regenerative systems. This review has presented a practical framework for integrating composting, anaerobic digestion, fermentation, and emerging hybrid technologies into circular bioeconomy models. It has also explored the enabling conditions and contextual factors that influence the success of these pathways.

The analysis shows that no single solution fits all contexts. Instead, effective systems are those that match technological options with feedstock characteristics, infrastructure capacity, local policies, and public engagement. Case studies from Toronto and Milan illustrate how both centralized, technology-intensive models and distributed, behavior-driven strategies can deliver high rates of waste diversion and resource recovery.

To fully realize the promise of a circular bioeconomy, future efforts must go beyond technology deployment. They must include supportive regulatory frameworks, long-term market development, infrastructure investment, and community participation. By closing material and energy loops, circular strategies for biodegradable waste not only reduce environmental burdens but also contribute to broader goals in climate action, soil health, and sustainable development. This review is limited to studies published between 2010 and 2025 and selected gray literature; future work should expand the scope to additional databases, emerging pilot projects, and long-term monitoring of case studies.

Author Contributions

There are no sources in the current document. Contributions: Conceptualization, S.C. and M.M.; methodology and visualization, S.C.; formal analysis, S.C., M.M. and A.R.M.S.; resources and data curation, S.C. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C., A.R.M.S., M.M., H.E., E.M. and H.J.; student support, H.J.; supervision and project administration, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Salomeh Chegini and Mehran Masoudi were employed by KSB Canada, and Elham Mojaver was employed by CE3 Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Raclavská, H.; Růžičková, J.; Švédová, B.; Kucbel, M.; Šafář, M.; Raclavský, K.; Abel, E.L.D.S. Biodegradable Waste Streams. In Biodegradable Waste Management in the Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 69–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mhaddolkar, N.; Astrup, T.F.; Tischberger-Aldrian, A.; Pomberger, R.; Vollprecht, D. Challenges and opportunities in managing biodegradable plastic waste: A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 43, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleke, S.; Cole, S.M.; Sekabira, H.; Djouaka, R.; Manyong, V. Circular bioeconomy research for development in sub-Saharan Africa: Innovations, gaps, and actions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.R.; Gupta, V.K.; Alam, P.; Perriman, A.W.; Scarpa, F.; Thakur, V.K. From trash to treasure: Sourcing high-value, sustainable cellulosic materials from living bioreactor waste streams. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, J.A.; Sierra-Fontalvo, L.; Ortegon, K.; Gonzalez-Quiroga, A. Advancing circular bioeconomy: A critical review and assessment of indicators. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Wei, W.; Cheng, D.; Bui, X.T.; Hoang, N.B.; Zhang, H. Biofuel production for circular bioeconomy: Present scenario and future scope. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 172863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipfer, F.; Burli, P.; Fritsche, U.; Hennig, C.; Stricker, F.; Wirth, M.; Proskurina, S.; Serna-Loaiza, S. The circular bioeconomy: A driver for system integration. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Wever, M.; Espig, M. A framework for assessing the potential of artificial intelligence in the circular bioeconomy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Paritosh, K.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Integrated system of anaerobic digestion and pyrolysis for valorization of agricultural and food waste towards circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casau, M.; Dias, M.F.; Matias, J.C.; Nunes, L.J. Residual biomass: A comprehensive review on the importance, uses and potential in a circular bioeconomy approach. Resources 2022, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, L.; Cordiner, S.; De Maina, E.; Kumar, G.; Mele, P.; Mulone, V.; Igliński, B.; Piechota, G. Sustainable valorization of bioplastic waste: A review on effective recycling routes for the most widely used biopolymers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, S. Unlocking the Power of Methanogens: Revolutionary Applications in Sustainable Energy and Biotechnology. In Methanogens-Unique Prokaryotes: Unique Prokaryotes; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ansar, A.; Du, J.; Javed, Q.; Adnan, M.; Javaid, I. Biodegradable Waste in Compost Production: A Review of Its Economic Potential. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Michie, R. Circular Economy Policies in Europe: Assessing Regional Policy Integration; European Policies Research Centre: Glasgow, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2023; FAOSTAT: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Varjani, S.; Shah, A.V.; Vyas, S.; Srivastava, V.K. Processes and prospects on valorizing solid waste for the production of valuable products employing bio-routes: A systematic review. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 130954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Circular Innovation Coucil. Becoming Ontario’s First Circular City: Toronto’s Community Composting Program Toronto; Circular Innovation Coucil: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- C40 Cities. Cities100: Milan—Collecting Food Waste City-Wide; C40 Cities: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toronto Co., Ltd. Solid Waste Reports & Diversion Rates—2024 Residential Diversion Rates; Toronto Co., Ltd.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Toronto Co., Ltd. Solid Waste Management Facilities—Dufferin and Disco Road Organics Processing Facilities Toronto; Toronto Co., Ltd.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickrama, K.; Ruparathna, R.; Seth, R.; Biswas, N.; Hafez, H.; Tam, E. Challenges and Issues of Life Cycle Assessment of Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Waste. Environments 2024, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, S.; Elbeshbishy, E. Enhancing Single-and Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion of Thickened Waste-Activated Sludge through FNA-Heat Pretreatment. Processes 2024, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakibuzzaman, M.; Suh, S.-H.; Roh, H.-W.; Song, K.H.; Song, K.C.; Zhou, L. Hydraulic performance optimization of a submersible drainage pump. Computation 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, A. A Community Compost Exchange Manual: Reconnecting Municipal Organic Waste and Soil Management; York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, O.; Dutta, A. The current status and future potential of biogas production from Canada’s organic fraction municipal solid waste. Energies 2022, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z. Integrating Urban Forestry into Compact, Climate Resilient Cities: Policies and Pathways; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, B.; Pauly, C.P. New impeller combines reliability and efficiency. World Pumps 2016, 2016, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivchenko, O.; Andrusiak, V.; Kondus, V.; Pavlenko, I.; Petrenko, S.; Krupińska, A.; Włodarczak, S.; Matuszak, M.; Ochowiak, M. Energy efficiency indicator of pumping equipment usage. Energies 2023, 16, 5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, S. Energetic Optimisation of Wastewater Treatment Plant and Evaluation of Green House Gases; Politecnico di Torino: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Uffelman, V.; Svetushkov, V.; Savin, O. Modernization of Feedwater Pumps at the Kostroma Power Plant. Power Technol. Eng. 2021, 55, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.N.; Sarkar, O.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Raj, T.; Narisetty, V.; Mohan, S.V.; Pandey, A.; Varjani, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P.; et al. Upgrading the value of anaerobic fermentation via renewable chemicals production: A sustainable integration for circular bioeconomy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Flora, G.; Venkatkarthick, R.; SenthilKannan, K.; Kuppam, C.; Stephy, G.M.; Kamyab, H.; Chen, W.-H.; Thomas, J.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Advanced technologies on the sustainable approaches for conversion of organic waste to valuable bioproducts: Emerging circular bioeconomy perspective. Fuel 2022, 324, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenebault, C.M.R.; Trably, E.; Escudié, R.; Percheron, B. Lactic acid production from food waste using a microbial consortium: Focus on key parameters for process upscaling and fermentation residues valorization. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavesi, R.; Orsi, L.; Zanderighi, L. Enhancing Circularity in Urban Waste Management: A Case Study on Biochar from Urban Pruning. Environments 2025, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkilima, T. Hydrothermal liquefaction of wastewater as part of tailoring biocrude composition for a circular bioeconomy: A review. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining, 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawo, O.E.; Mbamalu, M.I. Advancing waste valorization techniques for sustainable industrial operations and improved environmental safety. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueboudji, Z. Waste Valorization Techniques. Generation of Energy from Municipal Solid Waste: Circular Economy and Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Maina, P.; Gyenge, B.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Parádi-Dolgos, A. Analyzing trends in green financial instrument issuance for climate finance in capital markets. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, S. Integrated life cycle analysis of cost and CO2 emissions from vehicles and construction work activities in highway pavement service life. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Esparza, F.E.; González-López, M.E.; Ibarra-Esparza, J.; Lara-Topete, G.O.; Senés-Guerrero, C.; Cansdale, A.; Forrester, S.; Chong, J.P.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Implementation of anaerobic digestion for valorizing the organic fraction of municipal solid waste in developing countries: Technical insights from a systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 118993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, A.; de Olde, E.M.; Ripoll-Bosch, R.; Van Zanten, H.H.; Metze, T.A.; Termeer, C.J.; van Ittersum, M.K.; de Boer, I.J. Principles, drivers and opportunities of a circular bioeconomy. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Non-Hazardous Waste Reduction and Diversion in the Industrial, Commercial & Institutional Sector; Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Bioenergy. Implementation of Bioenergy in Canada—2024 Update; IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kardung, M.; Cingiz, K.; Costenoble, O.; Delahaye, R.; Heijman, W.; Lovrić, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; M’barek, R.; van Meijl, H.; Piotrowski, S.; et al. Development of the circular bioeconomy: Drivers and indicators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.; Osorio-Gonzalez, C.S.; Brar, S.K.; Kwong, R. A critical insight into the development, regulation and future prospects of biofuels in Canada. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9847–9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, M.N.V. Bioremediation and Bioeconomy: A Circular Economy Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen, T.; Sydd, O.; Kajanus, M.; Fernández Gutiérrez, D.; Mitsou, M.; Soriano Disla, J.M.; Sevilla, M.V.; Ib Hansen, J. Fortifying social acceptance when designing circular economy business models on biowaste related products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.; Eraky, M.; Osman, A.I.; Wang, J.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Yacoub, I.H.; Hanelt, D.; Abomohra, A. Sustainable valorization of waste glycerol into bioethanol and biodiesel through biocircular approaches: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. Turning Waste into Renewable Natural Gas; City of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- City of Toronto. Organics Processing Facilities (Dufferin and Disco Road); City of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- City of Toronto. 2022 Program Summary—Solid Waste Management Services (Budget Note); City of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Demichelis, F.; Tommasi, T.; Deorsola, F.A.; Marchisio, D.; Mancini, G.; Fino, D. Life cycle assessment and life cycle costing of advanced anaerobic digestion of organic fraction municipal solid waste. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Waste, E. The Story of Milan: Successfully Collecting Food Waste for over 1.4 Million Inhabitants; Zero Waste Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ACR+. Good Practice Milan: Door to Door Food Waste Collection for Households; ACR+: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Novamont. The Case Study of Milan. Internet; Novamont: Novara, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Bencivenni, E. Composting food waste or digestate? Characteristics, statistical and life cycle assessment study based on an Italian composting plant. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 350, 131552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottausci, S.; Magrini, C.; Tuci, G.A.; Bonoli, A. Plastic impurities in biowaste treatment: Environmental and economic life cycle assessment of a composting plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 9964–9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, F.A.M.; Ismail, K.A.R.; Castañeda-Ayarza, J. Municipal solid waste treatment in Brazil: A comprehensive review. Energy Nexus 2023, 11, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.R.; Guarnieri, P.; Ouro-Salim, O. Reducing food waste from a circular economy perspective: The case of restaurants in Brazil. World Food Policy 2022, 8, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidência da República. Lei Nº 12.305, de 2 de Agosto de 2010: Institui a Política Nacional de Resíduos Sólidos (PNRS); Presidência da República: Brasília, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- França, L.; Ferreira, B.O.; Corrêa, G.M.d.C.; Ribeiro, G.M.; Bassin, J.P. Carbon Footprint of Food Waste Management: A Case Study in Rio de Janeiro. Carbon Footprint Case Studies; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, F.T.F.; Gonçalves, A.T.T.; Lima, J.P.; da Silva Lima, R. Transitioning towards a sustainable circular city: How to evaluate and improve urban solid waste management in Brazil. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.A.; Lafratta, J.M.; Moura, P.S.D. Context and prospects for decentralized composting of Municipal Solid Waste in Brazil. Rev. Nac. Gerenciamento Cid. 2023, 11, 2318–8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, G. Circular bio-economy—Paradigm for the future: Systematic review of scientific journal publications from 2015 to 2021. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 231–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, T.; Beintema, N.; Alho, C.F.B.V.; van der Poel, M. Experiences in Assessing the Impact of Circular Economy Interventions in Agrifood Systems—A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tian, G.; Liu, B.; Bian, B.; He, C. A new scheme for low-carbon recycling of urban and rural organic waste based on carbon footprint assessment: A case study in China. NPJ Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Parthasarathy, P.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T.; McKay, G. Food waste biochar: A sustainable solution for agriculture application and soil–water remediation. Carbon Res. 2024, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.F.; Gogoi, B.; Saikia, R.; Yousaf, B.; Narayan, M.; Sarma, H. Encouraging circular economy and sustainable environmental practices by addressing waste management and biomass energy production. Reg. Sustain. 2024, 5, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.