Abstract

Background: Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) affects nearly 9% of the global population with a rising incidence over recent decades. Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease pose significant global burden, and emerging evidence suggests pathophysiological links through shared bioenergetic dysfunction, peripheral-to-central inflammatory signaling, and altered nasal microbiota. This review evaluates the evidence for CRS as a potentially modifiable peripheral contributor to neurodegenerative disease progression. Methods: A systematic review was conducted using PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, Embase, and CENTRAL from January 2000 to July 2025. Search terms included “Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” “Neurodegeneration,” “Mild Cognitive Impairment,” “Alzheimer’s Disease,” “Parkinson’s Disease,” “Bioenergetics,” and “Microbiome.” Clinical and experimental studies exploring epidemiological links, mechanistic pathways, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets were included. Results: Twenty-one studies involving over 100,000 participants met the inclusion criteria. Existing meta-analytic evidence demonstrated significant associations between CRS and cognitive impairment, with patients scoring approximately 9% lower on global cognitive measures than controls. However, other large-scale cohort studies did not pinpoint an increased dementia incidence, suggesting CRS may contribute to early, potentially reversible cognitive decline without directly driving dementia onset. Neuroimaging studies revealed altered frontoparietal connectivity and orbitofrontal hyperactivity in CRS patients. Mechanistic studies support peripheral inflammatory cytokines disrupting the blood–brain barrier, autonomic dysfunction impairing mucociliary clearance, microbiome-driven amyloid cross-seeding, and compromised cerebrospinal fluid clearance via olfactory–cribriform pathways. Discussion: Evidence supports complex, bidirectional relationships between CRS and neurodegeneration characterized by convergent inflammatory, autonomic, and bioenergetic pathways. Therapeutic strategies targeting sinonasal inflammation, microbiome dysbiosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction represent promising intervention avenues. Recognizing CRS as a treatable factor in neurodegenerative risk stratification may enable earlier diagnosis and prevention strategies.

1. Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and neurodegenerative disorders represent converging epidemiological challenges that warrant urgent scientific investigation. Globally, CRS affects 8.71% of the population. Its prevalence has notably risen dramatically, increasing from 4.72% between 1980 and 2000 to 19.40% between 2014 and 2020 [1]. Concurrently, neurodegenerative disorders have high epidemiological burdens, with over 60 million people worldwide living with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [2,3] and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [4,5] in 2021, representing one of the leading causes of ill health and disability globally.

These two conditions intersect through intertwined pathophysiological loops in which disrupted mitochondrial bioenergetics results from and perpetuates chronic neuroinflammation. We propose that mitochondrial dysfunction within inflamed sinonasal epithelium, marked by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, may propagate systemic pro-oxidant signals that reach the brain, impair neuronal ATP generation, and trigger microglial activation. Reciprocally, neurodegeneration-associated mitochondrial failure and ROS surges in central neurons can impair autonomic regulation and mucociliary clearance, aggravating sinonasal inflammation and microbiome dysbiosis [6,7]. Mitochondrial energy deficiency is considered a key element of different clinical pathologies, particularly affecting energy-demanding tissues such as the brain. This mechanistic overlap suggests CRS may function as an upstream modifier of neurodegenerative risk through shared bioenergetic pathways.

This clinical significance manifests through the olfactory system, with 90% of early-stage PD patients and 85% of early-stage AD patients experiencing olfactory dysfunction [8]. These deficits typically appear 10 to 15 years before other symptoms like tremors or cognitive impairment, further establishing the olfactory pathway as a critical early biomarker. The “nasal–neuron axis” represents a unique anatomical interface where nasal inflammation can potentially bypass the blood–brain barrier [9]; this enables the direct access of inflammatory mediators to vulnerable brain regions through established neuroanatomical pathways.

This review explores how impaired bioenergetics drives neurodegenerative pathology, highlighting chronic rhinosinusitis as a modifiable peripheral inflammatory condition that may accelerate these processes. It also identifies novel therapeutic targets for early intervention to disrupt neurodegenerative cascades.

2. Methods

To review the link between CRS and neurodegeneration, a literature search was performed on PubMed, Cochrane library, Web of Science, Embase, and CENTRAL (the Cochrane Central register of controlled trials) from January 2000 to July 2025 using the following keywords: “Chronic Rhinosinusitis”, “Rhinosinusitis”, “Sinonasal dysfunction”, “Neurodegeneration”, “Mild Cognitive Impairment”, “Alzheimer’s Disease”, “Parkinson’s Disease”, “Dementia”, “Bidirectional pathway”, “Biomarkers”, “Inflammatory markers”, “Bioenergetics”, “Therapeutic targets”, “Management pathways”, “Mitochondrial dysfunction”, “Autonomic dysfunction”, “Microbiome”, “Dysbiosis”, and “Research gaps”. Data from relevant articles investigating CRS and its interactions with neurodegeneration, associated mechanistic/molecular pathways, possible therapeutics, and future research targets were extracted with the aim of synthesizing the existing literature on CRS and its potential link to neurodegeneration as well as its potential as a therapeutic pathway. Clinical and scientific (experimental) studies were both included to further examine the relationship between CRS and neurodegeneration. The search strategy is included in Appendix A (Table A1).

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The search and selection of relevant articles for discussion were conducted by Nevin Chua Yi Meng (N.C.Y.M.) and Ang Lee Fang (A.L.F.). These were later verified by Wang Jia Dong James (W.J.D.J.).

3. Results

This review identified 21 studies examining bidirectional pathophysiological relationships between chronic rhinosinusitis and neurodegenerative diseases, encompassing 102,441 participants across diverse study designs from 2010 to 2025, as outlined in Table 1 and Table 2. There were a total of 16 clinical studies and 5 pathophysiological studies exploring the link between CRS and neurodegeneration.

Table 1.

Clinical studies depicting the link between CRS and neurodegeneration.

Table 2.

Relevant pathophysiology studies linking CRS to neurodegeneration.

3.1. Association Between CRS and Neurodegeneration

Meta-analytic evidence demonstrated a significant association between CRS and cognitive impairment [11]. A pooled analysis of 10 studies comprising 1149 participants revealed that individuals with CRS scored an average of 9% lower on global cognitive assessments compared to healthy controls (odds ratio (OR) = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.88–0.94). These findings indicate a significant relationship between chronic sinonasal inflammation and reduced neurocognitive performance. By contrast, a large population-based case-control analysis [17] (n = 88,170) detected no excess dementia risk in individuals with CRS (adjusted OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.82–1.13, p = 0.653), a result echoed by a longitudinal cohort [12] of 10,630 older adults with CRS in which dementia incidence remained unchanged (0.125 per 1000 person-years; adjusted HR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.8–1.3). Taken together, these findings suggest that while CRS is reliably associated with subtler, potentially reversible cognitive deficits, its progression to dementia may depend on additional modifiers such as endotype-specific inflammation, autonomic dysfunction, or microbiome-driven neuroinflammatory pathways, highlighting the need for mechanistic studies that can further elucidate the complex nature of the relationship between the two conditions. Further robust evidence have also emerged from neuroimaging studies showing decreased frontoparietal network connectivity [15] and increased orbitofrontal cortex activity [13] in patients with CRS and neurodegeneration, while mitochondrial dysfunction studies identified five consistently downregulated hub genes (Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1), Branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase E1 subunit beta (BCKDHB), Carbonyl reductase 3 (CBR3), 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2), and Oxidation resistance protein 1 (OXR1)) with elevated mitochondrial ROS in CRSwNP patients [6,28], thus suggesting a possible downstream mechanical pathway between CRS and neurodegeneration.

3.2. Inflammatory Mechanism Between CRS and Neurodegeneration

CRS and neurodegeneration appear to interact via three convergent mechanisms. First, peripheral inflammation in CRS, characterized by elevated sinonasal IL-6, TNF-α, and Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), can breach a compromised blood–brain barrier to activate microglia through NF-κB and STAT3 signaling. It subsequently drives reactive oxygen species production in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, thereby promoting neuronal bioenergetic failure and synaptic loss in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [31]. Second, molecular pathways such as interconnected kinase pathways and non-coding RNA sequences between CRS and neurodegeneration have been found to possibly contribute to bidirectional neuro-sinonasal dysfunction and warrants discussion. Another notable mechanism is how the autonomic–oxidative dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease impairs nasal autonomic regulation by blunting the nasal cycle, elevating mucosal pH, and prolonging mucociliary clearance. Central mitochondrial defects, as a result, then amplify systemic ROS and have been found to compromise nasal epithelial integrity and predispose patients to chronic sinonasal inflammation. Finally, a potential shared pathway linking the two conditions is a “viral bridge.” Evidence suggests that herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) can penetrate inflamed nasal mucosa, foster co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus, and ascend along olfactory neurons to establish latency within the central nervous system. In hippocampal neurons, HSV-1 has been shown to impair DNA repair, promote amyloid-β accumulation, and enhance tau phosphorylation. Consistent with a viral contribution to neurodegeneration, epidemiological studies report an ~20% reduction in dementia risk following zoster vaccination, supporting viral involvement as a plausible mechanistic bridge between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS)-associated inflammation and neurodegeneration.

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Significance

The establishment of bidirectional pathophysiological relationships between CRS and neurodegeneration carries clinical significance with potential implications for both otolaryngological and neurological practice. This emerging link suggests opportunities for integrated assessment approaches, where CRS evaluation might contribute to neurodegenerative risk assessment in conjunction with other clinical indicators; additionally, neurodegeneration-associated findings could inform CRS management strategies to potentially optimize therapeutic outcomes [14]. Early recognition of CRS patients with concurrent olfactory dysfunction represents a clinically relevant observation point as olfactory impairment has demonstrated a positive predictive value for neurodegenerative disease development, such as severe hyposmia, which is associated with an 18.7-fold increased risk of dementia progression in Parkinson’s disease patients [32]. Similarly, the identification of neurodegeneration-associated rhinorrhea [14] (affecting 45% of Parkinson’s patients versus 14.7% of controls) and autonomic dysfunction suggests potential therapeutic avenues for targeted anticholinergic interventions that may address sinonasal symptoms while potentially supporting residual autonomic function and influencing disease trajectory [33].

The bidirectional relationship enables personalized risk stratification through nasal microbiome profiling, where specific bacterial communities such as Moraxella catarrhalis correlate significantly with more severe motor scores in Parkinson’s disease patients (r = 0.45, p < 0.05), suggesting that dysbiotic nasal communities may serve as biomarkers for neurodegeneration severity [27]. Emerging evidence demonstrates that microorganisms can exhibit direct pro-inflammatory properties, directly enhancing granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF+) and interferon-gamma positive (IFN-γ+) T-cell populations in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models, supporting its role in neuroinflammatory cascades [34]. Conversely, the early detection of neurodegenerative biomarkers through nasal sampling methods such as α-synuclein detection via real-time quaking-induced conversion assays [35] in nasal swabs (84% sensitivity from agger nasi sampling vs. 45% from middle turbinate) provides accessible diagnostic opportunities that complement traditional CSF-based approaches. Early detection of such biomarkers in nasal specimens has the potential to serve as predictors of CRS severity and progression. For instance, seed amplification assays (SAA) detecting misfolded α-synuclein in nasal brushings have identified positive SAA reactions in control subjects who were anosmic due to underlying CRS. Positive SAA scores were further found to correlate with both olfactory dysfunction and higher Sinonasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22) symptom scores [36]. Similarly, interdigitated microelectrode biosensor measurements of amyloid-β oligomers in nasal secretions demonstrated that higher capacitance change index (CCI) values were significantly associated with worse sinonasal symptom severity and elevated mucosal inflammation markers in CRS patients [37,38]. These findings suggest that nasal detection of α-synuclein and amyloid-β (aβ) aggregates may provide non-invasive indicators of CRS disease activity and could be incorporated into clinical algorithms to predict and monitor worsening sinonasal inflammation.

4.2. Current Evidence Base and Its Limitations

However, significant limitations in the current evidence base emphasize the critical importance of the present systematic investigation. First, methodological heterogeneity across studies includes inconsistent diagnostic criteria for CRS and its variants (CRSwNP and CRSsNP), variable neuropsychological assessment tools, and diverse population demographics that limit generalizability. Second, the predominance of cross-sectional designs prevents the establishment of temporal relationships and causal inference, while the few longitudinal studies available have insufficient follow-up periods to capture the slowly progressive nature of neurodegenerative processes. None of the existing neurocognitive or imaging studies have stratified patients by CRS endotype [39] (Type 1, 2, or 3 endotypes), leaving it unclear whether eosinophilic or neutrophilic inflammation differentially affects blood–brain barrier permeability or cognitive trajectories. There is also a lack of studies that simultaneously characterize sinonasal microbial communities alongside measures of neuroinflammation or neurodegenerative biomarkers, rendering the role of dysbiosis in perpetuating peripheral–central inflammatory loops unquantified.

Finally, despite evidence implicating Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (HSV-1) and Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) in sinonasal epithelial damage and Alzheimer’s pathology, respectively [40], herpesvirus reactivation dynamics have yet to be examined in CRS cohorts in tandem with neurodegenerative assays, limiting further insight into whether chronic viral persistence potentiates central proteinopathy.

4.3. Inflammatory Cascade: Cytokine-Mediated Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption

4.3.1. CRS-Driven Neuroinflammation

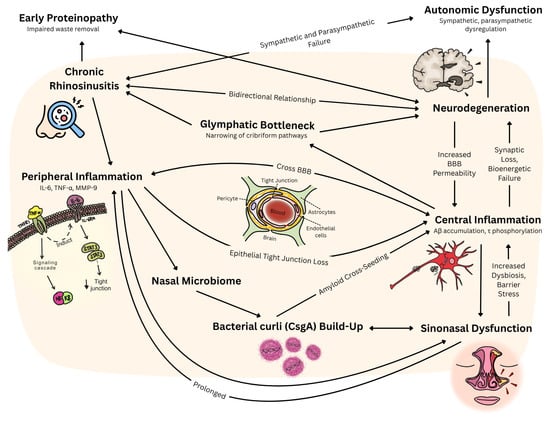

Chronic rhinosinusitis generates robust local inflammation characterized by significantly elevated concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and MMP-9 within sinonasal tissues compared to healthy controls. Human cell experiments show that these pro-inflammatory mediators establish a pathophysiological cascade whereby peripheral cytokines compromise blood–brain barrier integrity through TNF-α-mediated induction of endothelial IL-6 production and subsequent STAT3 signaling activation [41]. This cytokine-driven process systematically downregulates critical tight junction proteins, including claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1, while simultaneously generating ROS that compromise microvascular integrity. When these peripheral inflammatory mediators breach the compromised blood–brain barrier, they activate resident microglial cells and astrocytes through nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathways, establishing a neuroinflammatory environment that amplifies oxidative stress and promotes neuronal dysfunction characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed link between CRS and neurodegeneration, and the possible interactions between physiological pathways. Legend. IL-6: interleukin-6; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase-9; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; BBB: blood–brain barrier; Aβ: amyloid-beta; τ: tau; CsgA: Curli subunit A.

4.3.2. Neurodegeneration-Induced Sinonasal Dysfunction

Conversely, neurodegenerative processes compromise sinonasal function through autonomic nervous system failure that directly impacts nasal physiological homeostasis. Parkinson’s disease patients exhibit alterations in nasal autonomic regulation, including absent or significantly blunted nasal cycles, elevated nasal mucosal pH, and prolonged mucociliary clearance times compared to healthy controls [42]. This association between rhinorrhea and other autonomic symptoms, particularly lightheadedness (52% versus 9% in PD patients without rhinorrhea, p = 0.02), supports sympathetic denervation as the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms [24] in human studies. Autonomic failure in neurodegeneration is proposed to disrupt nasal vascular tone and mucociliary clearance via this process of denervation and parasympathetic hyperactivity [42], thus compromising epithelial barriers and perpetuating sinonasal inflammation [43]. The olfactory pathway itself provides direct CNS access: inflammatory mediators and pathogens bypass the BBB via olfactory neurons, while impaired glymphatic outflow through the cribriform plate reduces the clearance of toxic proteins [44]. Together, these mechanisms establish self-reinforcing inflammatory loops linking peripheral CRS pathology with central neurodegenerative processes.

4.4. Molecular Mechanisms: Kinase Signaling and Post-Translational Modifications

4.4.1. Bidirectional Molecular Pathways and Neuroinflammation

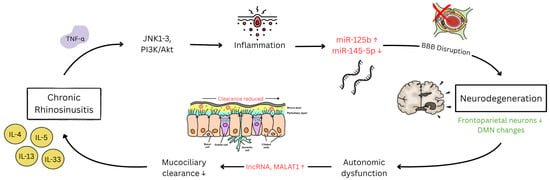

Chronic rhinosinusitis initiates neurodegeneration through type 2 inflammation [45] characterized by elevated IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-33. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway [46] emerges as a critical mediator of olfactory neurodegeneration in human tissue study samples, with phosphorylated c-Jun significantly elevated in the olfactory epithelium of CRS patients compared to controls (p = 0.001), indicating ongoing neuronal apoptosis. TNF-α/JNK signaling through TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) leads to activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor formation and progressive olfactory sensory neuron loss [47].

This inflammatory cascade propagates through interconnected kinase signaling networks that amplify and sustain neurodegeneration. Cellular studies show that key kinases [48] mediating CRS neurodegeneration include JNK1–3 isoforms (particularly JNK3 in neuronal apoptosis), mechanistic targets of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), and NF-κB pathway kinases (Figure 2). Mixed-lineage kinases (MLKs) serve as primary upstream activators of JNK in CRS-related inflammation, with genetic ablation of TNFR1 significantly inhibiting JNK activation (p = 0.0012). Concurrently, the mTOR pathway [49] creates feed-forward inflammatory loops through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling [50], promoting protein synthesis while impairing autophagy mechanisms essential for neuronal maintenance [51]. Casein kinase 1 family members further dysregulate Wnt signaling and circadian rhythms in CRS patients, contributing to systemic metabolic disruption that exacerbates neurodegeneration.

Figure 2.

Current established molecular and post-translational pathways between CRS and neurodegeneration. ↑ indicates upregulation while ↓ indicates downregulation. Legend. TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; PI3K/Akt: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B; miR-125b: microRNA-125b; miR-145-5p: microRNA-145-5p; BBB: blood–brain barrier; DMN: default mode network; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; MALAT1: metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; IL-4: interleukin-4; IL-5: interleukin-5; IL-13: interleukin-13; IL-33: interleukin-33.

The sustained activation of these kinase pathways culminates in widespread post-translational modifications that fundamentally alter protein function and cellular homeostasis [52]. Cell studies of phosphorylation-mediated mechanisms [53] involve tau hyperphosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), promoting neurofibrillary tangle formation characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases. Simultaneously, α-synuclein phosphorylation at serine 129 by casein kinase 2 (CK2) and polo-like kinase 2 (PLK2) facilitates protein aggregation and Lewy body formation. Additionally, hypusine formation [54,55] in eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (eIF5A) through deoxyhypusine synthase (DHPS) represents a critical post-translational modification affecting neuronal development and function [56], with neuron-specific ablation leading to severe neurodevelopmental defects. The culminating dysfunction [57] of the ubiquitin–proteasome system leads to misfolded protein accumulation characteristic of neurodegeneration, completing the molecular cascade from chronic sinonasal inflammation to neuronal dysfunction.

Beyond conventional kinase pathways, several other kinases establish mechanistic bridges linking CRS to neurodegeneration and warrant discussion. Oxidized Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (ox-CaMKII) functions as an amplifier of eosinophilic CRSwNP pathology [58], with nasal polyps demonstrating significantly elevated ox-CaMKII expression in activated mast cells compared to controls [59]. The kynurenine/aryl hydrocarbon receptor axis triggers CaMKII oxidation at methionine residues 281/282 [60], activating pro-inflammatory NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors while enhancing NADPH oxidase expression to establish self-perpetuating inflammatory loops [61]. Centrally, ethanol-activated CaMKII induces neuronal apoptosis via Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and JNK1-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation [62], while CaMKII inhibition paradoxically triggers neurotoxicity through dysregulated glutamate/calcium [63] signaling [64]. Death-associated Protein Kinase 1 (DAPK1) was also found to be abnormally elevated in AD and PD brains, demonstrating dual pathological cascades by directly phosphorylating α-synuclein at Ser129 to induce insoluble aggregates [65] and potentiate rotenone-induced dopaminergic cell death [66], while simultaneously phosphorylating prolyl isomerase Pin1 at Ser71 to trigger tau hyperphosphorylation at multiple AD-related sites [66]. Both DAPK1 genetic knockout and pharmacological inhibition has been shown to protect primary neurons against Aβ aggregate-induced pathology [67]. In contrast, Polo-like Kinase 2 (PLK2) represents a protective mechanism that uniquely couples α-synuclein phosphorylation at Ser129 with enhanced autophagic degradation [68] through selective lysosome-autophagy pathways. In rat PD models, PLK2 overexpression reduces intraneuronal α-synuclein accumulation, suppresses dopaminergic neurodegeneration, and possibly reverses hemiparkinsonian motor impairments [69], effects that were abolished when non-phosphorylatable S129A α-synuclein is expressed [70]. The convergence of these kinase pathways suggests that CRS disrupts the physiological balance maintained by protective kinases like PLK2 through sustained ox-CaMKII and DAPK1 activation, creating a pathological milieu conducive to neurodegeneration.

4.4.2. The Role of Non-Coding RNA in CRS and Neurodegeneration

Studies [71] investigating non-coding RNAs have also found these molecules to orchestrate bidirectional regulatory loops between CRS and neurodegeneration through coordinated microRNA and long non-coding RNA networks. MicroRNAs function as systemic inflammatory messengers with microRNA-125b (miR-125b) upregulation in eosinophilic CRS found to be targeting 4E-BP1/interferon-β pathways to promote blood–brain barrier disruption. Simultaneously, microRNA-145-5p (miR-145-5p) downregulation promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition through SMAD3 (Small Mother Against Decapentaplegic 3)/TGF-β signaling [72], further extending tissue remodeling to the olfactory neuroepithelium and contributing to progressive sensory neuron loss [73].

The reverse pathway operates through autonomic dysfunction as mentioned above [74], where compromised autonomic control centers impair parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation of nasal mucosa, leading to peripheral inflammation [75,76]. Long non-coding RNAs amplify these connections through competing endogenous RNA mechanisms and chromatin regulation. Other long non-coding RNAs, such as metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), interact with serine/arginine-rich splicing factors [77] to orchestrate alternative splicing decisions affecting both inflammatory gene expression in sinonasal tissues and neuroinflammatory responses in brain regions. Recognition of these bidirectional molecular connections provides mechanistic foundations for understanding how CRS and neuroprotective interventions might provide mutual benefits for both conditions.

4.4.3. Bidirectional Neuro-Sinonasal Network Dysfunction

CRS and neurodegeneration also exhibit reciprocal pathophysiology through interconnected neural network disruptions [15]. Functional MRI demonstrates dose-dependent relationships between sinonasal inflammation and decreased frontoparietal network connectivity, which correlates directly with executive dysfunction severity [75]. These network alterations impair central autonomic control, creating feedback loops where cognitive dysfunction exacerbates sinonasal pathology through compromised parasympathetic regulation. JNK-mediated olfactory sensory neuron apoptosis [78] affects 30% of olfactory marker protein-positive neurons [46], creating a bidirectional pathology where chronic inflammation causes deafferentation while olfactory dysfunction impairs cerebrospinal fluid clearance through cribriform plate pathways, worsening concurrent CRS [79].

Neuroinflammation subsequently creates epileptogenic vulnerability through IL-1β-, TNF-α-, and IL-6-mediated seizure threshold reduction [80], with children demonstrating a 76% increase in epilepsy risk following chronic sinonasal inflammation [81]. Sleep disruption compounds these effects through altered neurotransmitter balance and increased oxidative stress [82]. These suggest a possibility where treatments targeted towards CRS inflammation could have the potential to be modified to even address neurological sequelae such as seizures.

4.5. Microbiome-Mediated Cross-Seeding: Bacterial Amyloid as Pathological Bridge

4.5.1. Bacterial Amyloid Cross-Seeding Mechanisms

The nasal microbiome also serves as a mechanistic bridge linking CRS to neurodegeneration through bacterial curli amyloid cross-seeding with host protein aggregates. Genome-wide Caenorhabditis elegans screening identified bacterial Curli subunit A (CsgA) as a potent facilitator of α-synuclein aggregation through direct cross-seeding mechanisms, with CsgA colocalizing at the center of α-synuclein aggregates and serving as a nucleation seed [83]. This bidirectional process involves CsgA promoting α-synuclein accumulation, while α-synuclein facilitates CsgA retention within neurons, creating self-reinforcing pathological cycles. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of CsgA using epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) was found to significantly reduce α-synuclein-induced neuronal death, restore mitochondrial gene expression (including Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family member involved in fatty acid β-oxidation (acdh-1), Branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (bcat-1), Enoyl-CoA hydratase 6 (ech-6), and Hydroxyproline dehydrogenase 1 (hpdh-1)), and normalize cellular respiration [84]. The cross-seeding mechanism extends across multiple proteinopathies, with CsgA-deficient bacterial diets improving neuronal survival in the C. elegans models of Alzheimer’s disease and decreasing huntingtin aggregation in the Huntington’s disease model. Parallel human studies using neuroblastoma cell validation confirms that CsgA-derived amyloidogenic peptides enhance α-synuclein aggregation and exacerbate neuronal death, while non-amyloidogenic controls show no effect. These findings establish bacterial curli as a universal pathogenic trigger, possibly linking peripheral microbial dysbiosis to central neurodegeneration through shared amyloid cross-seeding mechanisms.

4.5.2. Pathogenic Microbiome Alterations in Neurodegeneration

Deep nasal sinus cavity microbiome analyses have also revealed a pronounced dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease that correlates with clinical severity. An existing study investigating PD patients exhibited a significant enrichment of the opportunistic pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis [27]. This correlated with more severe Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) motor scores (r = 0.42, p < 0.05). This pro-inflammatory shift occurred alongside depletion of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing, anti-inflammatory taxa, Blautia wexlerae, Lachnospira pectinoschiza, and Propionibacterium humerusii, species known to support mitochondrial and synaptic health. Machine learning approaches applied to olfactory fissure samples from 30 PD and 28 control subjects identified eight discriminatory taxa, including Staphylococcus aureus, Ralstonia insidiosa, and Acinetobacter guillouiae with classification accuracies exceeding 85% (AUC > 0.85) [85]. The anatomical proximity of these dysbiotic communities to the olfactory bulb, coupled with existing rodent data showing that intranasal M. catarrhalis inoculation triggers rapid microglial activation and elevated IL-1β/TNF-α expression within 48 h, supports a model in which pathogenic nasal bacteria initiate olfactory-bulb-mediated neuroinflammatory cascades that may contribute to dopaminergic neuronal vulnerability [8].

4.6. Olfactory–Limbic Axis: Proteinopathy Initiation and Clearance Dysfunction

4.6.1. Early Proteinopathy in Olfactory Structures

The olfactory system has a unique anatomical connectivity between the nasal cavity and limbic structures, bypassing blood–brain barrier protections and creating a preferential conduit for proteinopathy that precedes widespread central nervous system involvement [86]. Systematic neuropathological analysis of 331 autopsy cases reveals that olfactory bulb’s amyloid-β pathology follows a predictable hierarchical progression, increasing from <5% in lower Thal (beta-amyloid staging [87]) phases 0–1 to >80% in phases 4–5, with olfactory bulb Aβ pathology significantly predicting advanced Thal phases (OR = 12.8, 95% CI: 6.8–24.1) and cognitive impairment (OR = 6.2, 95% CI: 3.7–10.4). Longitudinal flortaucipir PET studies in 89 cognitively normal adults demonstrate that tau pathology spreads from medial temporal structures toward olfactory regions rather than originating peripherally, challenging earlier hypotheses about olfactory-initiated neurodegeneration [88]. The olfactory pathway represents the principal cerebrospinal fluid clearance route, with experimental evidence showing that chemical ablation of olfactory sensory nerves reduces CSF outflow through the cribriform plate, while surgical obstruction increases outflow resistance by 2.7-fold [89,90]. Dynamic PET studies reveal 66% lower cerebrospinal fluid clearance in Alzheimer’s patients compared to controls, with CRS potentially compromising this pathway through inflammatory disruption of olfactory epithelial integrity and altered CSF dynamics [44]. This clearance dysfunction establishes a mechanistic link whereby peripheral sinonasal inflammation indirectly promotes central neurodegeneration through impaired waste removal, creating conditions conducive to protein aggregation and downstream propagation to limbic structures.

4.6.2. Compromised Cerebrospinal Fluid Clearance Mechanisms

Anatomical, experimental, and clinical evidence establishes the cribriform-plate–olfactory–lymphatic pathway as a major extracranial cerebrospinal fluid egress route whose dysfunction mechanistically couples CRS to neurodegenerative disease progression [91,92]. Murine and human micro-CT studies demonstrate direct anatomical continuity from the subarachnoid space to lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1)-positive lymphatic vessels surrounding the olfactory nerves as they traverse the cribriform plate, enabling bulk CSF flow to nasal submucosa, with in vivo fluorescence tracing confirming the rapid (≤15 min) movement of CSF tracers from cisterna magna to cervical lymph nodes via these channels [89]. Chemical ablation of olfactory sensory neurons with intranasal ZnSO4 was found to reduce cribriform outflow of 3 kDa CSF tracers by approximately 60% without raising intracranial pressure, while surgical sealing of the cribriform plate in sheep elevates resting intracranial pressure by >90%, confirming this route’s quantitative importance under normal physiological conditions [93]. Dynamic PET studies employing the Tohoku University-developed arylquinoline-based tau tracer, 18F-THK5117 (a 2-arylquinoline derivative distinct from the pyridoindole tracer flortaucipir [18F-AV1451]), in 15 participants demonstrated a 23% reduction in ventricular-to-nasal CSF clearance and 66% fewer nasal egress voxels in Alzheimer’s disease versus age-matched controls, with independent 15O-H2O PET studies reporting 45–50% reductions in CSF water influx to basal cisterns and nasal turbinates [94]. CRS compromises this critical clearance pathway through epithelial tight-junction disruption and elevated MMP-9, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels in the olfactory cleft, which degrades barrier integrity and physically narrows perineural channels [95,96]. This inflammatory narrowing of cribriform pathways slows glymphatic-to-lymphatic clearance, allowing interstitial amyloid-β and tau to accumulate locally, with reduced outflow correlating with higher cortical amyloid burden and establishing a feed-forward loop wherein sinonasal inflammation impedes CSF egress while retained neurotoxic proteins amplify central neuroinflammation and further compromise nasal epithelial repair.

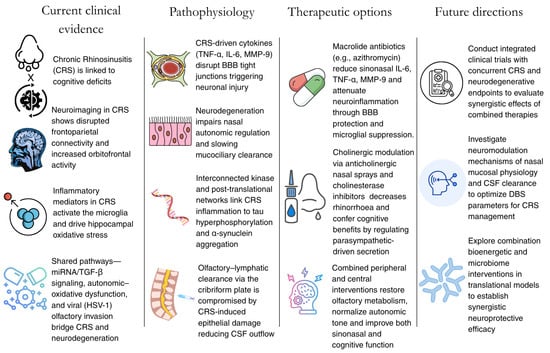

4.7. Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Future therapeutic implications along the “nasal–neuron” axis are bidirectional, with specialized management strategies for each condition having potential synergistic effects on the other. Emerging evidence suggests that conventional pharmacological therapies for each condition may exert reciprocal therapeutic benefits through shared inflammatory, autonomic, and bioenergetic pathways. Macrolide antibiotics, particularly azithromycin [97], demonstrate dual therapeutic potential by suppressing sinonasal pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and MMP-9) that would otherwise breach the blood–brain barrier and activate microglial cells, thereby potentially attenuating neuroinflammatory cascades associated with neurodegenerative disease progression, while simultaneously reducing endoscopic inflammation [98,99]. Of note, ipratropium bromide, an anticholinergic nasal spray traditionally employed for neurodegeneration-associated rhinorrhea, functions through localized M3 muscarinic receptor blockade to decrease parasympathetic-mediated glandular secretion, offering therapeutic benefits for both Parkinson’s disease patients experiencing rhinorrhoea and chronic rhinosinusitis patients [100]. Donepezil also has promising applications, with retrospective data showing that Parkinson’s patients had a decrease in patient-reported rhinorrhoea on a 4-point scale (p = 0.04) and a 15% reduction in topical steroid use among CRS-comorbid subjects [101]. A possible mechanism is the diminished parasympathetic glandular secretion in the nasal mucosa as systemic acetylcholinesterase inhibition is attenuated. These findings underscore the role of cholinergic pathways in sinonasal secretion and suggest that careful dose adjustment of cholinesterase inhibitors may offer symptomatic relief for CRS-related rhinorrhoea without compromising cognitive benefits. These pharmacological strategies highlight the potential for integrated therapeutic approaches that exploit the mechanistic overlap while addressing the fundamental pathophysiological processes linking these conditions.

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) has emerged as a possible therapeutic option that mitigates sinonasal inflammation and restores olfactory-bulb glucose metabolism, translating into quantifiable gains in attention, executive function, and processing speed in CRS cohorts [19,22]. On the other hand, neuromodulation therapies developed for neurodegenerative disease, such as deep-brain stimulation (DBS), offer a plausible route to reverse peripheral disease activity in CRS. Sub-thalamic or hypothalamic DBS engages the central autonomic network, rapidly tuning sympathetic–parasympathetic output to cardiovascular, respiratory, and mucosal targets. Documented effects include normalization of baroreflex sensitivity and correction of sudomotor hyperactivity in Parkinson’s disease and cluster-headache populations [102,103]. As nasal venous capacitance and glandular secretion are governed predominantly by sympathetic tone, DBS-induced upregulation of adrenergic drive could theoretically decompress congested mucosa, accelerate mucociliary clearance, and dampen neurogenic inflammation, an inference supported by case reports of stimulation-evoked sneezing and by small trials showing improved olfaction after DBS implantation [104,105,106]. Taken together, these observations posit a balanced therapeutic model where peripheral interventions such as ESS can attenuate central bioenergetic stress, while neuromodulation may reciprocally recalibrate autonomic pathways that perpetuate CRS, underscoring the need for integrated trials that measure cognitive and sinonasal endpoints in tandem.

Further investigations into interventions should also focus on key mechanistic pathways, with bioenergetic modulation representing the most promising therapeutic frontier. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, particularly MitoQ (mitoquinone) and SS-31 (Szeto-Schiller peptide 31), demonstrate remarkable efficacy in mitigating oxidative stress in hippocampal neurons while simultaneously addressing sinonasal mitochondrial dysfunction [107,108]. MitoQ achieves therapeutic precision through its triphenylphosphonium-mediated mitochondrial targeting, accumulating 100–1000 fold within mitochondria and undergoing continuous recycling by Complex II to maintain sustained antioxidant activity. Existing clinical trials have demonstrated a 42% improvement in endothelial function and significant reductions in oxidative stress markers [109,110]. Complementarily, SS-31 operates through cardiolipin stabilization, concentrating 1000–5000 fold in the inner mitochondrial membrane to restore cristae architecture and optimize respiratory chain function with demonstrated efficacy in reducing inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and MMP-9) by 40–60% in respiratory inflammation models [111,112]. This dual-target approach addresses both the excessive ROS production driving sinonasal inflammation and the neuroinflammatory cascades propagating to vulnerable brain regions, thereby offering comprehensive mitochondrial protection that simultaneously targets peripheral CRS pathology and central neurodegeneration through shared bioenergetic mechanisms.

Other therapeutic approaches such as microbiome engineering, including nasal microbiota transplantation (NMT), present as a possible treatment modality with clinical trials demonstrating remarkable efficacy in reversing dysbiosis and reducing neurodegenerative biomarkers. A controlled study of 22 patients with CRS showed that NMT following antibiotic preconditioning produced significant and lasting reductions in SNOT-22 scores (median reduction of 22 points, p = 0.000035) at 3-month follow-up [113]. Critically, NMT increased nasal bacterial diversity and abundance, with microbiome analysis revealing restoration of beneficial bacterial communities associated with reduced inflammatory signaling. The therapeutic mechanism involves healthy donor microbiota outcompeting pathogenic organisms, restoring epithelial barrier function, and reducing amyloid-β seeding in olfactory pathways [114].

In summary (Figure 3), effective treatment of CRS-associated neurodegeneration demands integrated strategies that directly address its complex, interacting pathophysiological mechanisms. Combination therapies targeting bioenergetic dysfunction, microbiome dysbiosis, and inflammatory cascades are essential for advancing clinical outcomes. Evidence increasingly supports the use of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants in tandem with microbiome engineering to achieve synergistic neuroprotective effects. Preclinical studies have demonstrated markedly enhanced neuroprotection when bioenergetic and microbiological interventions are applied concurrently, making such combination approaches a clear priority for translational research and therapeutic development [115].

Figure 3.

Summary of the current findings and future directions to take to further explore the link between CRS and neurodegeneration.

5. Conclusions

Although definitive causal links between CRS and neurodegeneration remain to be established, current evidence suggests CRS may exacerbate neuronal pathophysiology through peripheral inflammation, while neurodegenerative processes can disrupt sinonasal homeostasis via autonomic dysregulation. It should be noted that olfactory dysfunction or rhinorrhea alone does not necessarily equate to CRS, and most acute CRS exacerbations are effectively managed with antibiotics, limiting central sequelae. Nonetheless, in vulnerable patients, bidirectional interventions hold promise: controlling sinus inflammation could reduce neuroinflammatory burden, and neuroprotective therapies may restore autonomic balance to improve mucociliary clearance. Recognizing CRS as a potential, treatable contributor to neurodegenerative risk warrants further mechanistic studies and clinical trials to refine integrated treatment strategies that address both peripheral sinonasal and central neurological health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Y.M.C. and J.D.J.W.; methodology, N.Y.M.C. and J.D.J.W.; data analysis, N.Y.M.C., L.F.A. and J.D.J.W.; data curation, N.Y.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Y.M.C., L.F.A., B.J.S.L. and J.D.J.W.; writing—review and editing, N.Y.M.C., L.F.A. and J.D.J.W.; Creation of visual materials, L.F.A.; supervision, J.D.J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were collected in the course of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Depicting the literature search conducted and relevant search criteria.

Table A1.

Depicting the literature search conducted and relevant search criteria.

| Search Parameters | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Date of search | 8 July 2025 |

| Databases searched | PubMed, Cochrane library, Web of Science, Embase, CENTRAL (Cochrane Central register of controlled trials) |

| Search terms utilized | “Chronic Rhinosinusitis”, “Rhinosinusitis”, “Sinonasal dysfunction”, “Neurodegeneration”, “Mild Cognitive Impairment”, “Alzheimer’s Disease”, “Parkinson’s Disease”, “Dementia”, “Bidirectional pathway”, “Biomarkers”, “Inflammatory markers”, “Bioenergetics”, “Therapeutic targets”, “Management pathways”, “Mitochondrial dysfunction”, “Autonomic dysfunction”, “Microbiome”, “Dysbiosis”, “Research gaps” |

| Timeframe | January 2000 to July 2025 |

| Inclusion criteria | English studies investigating the CRS–neurodegeneration pathway |

| Exclusion criteria | Editorials, opinion pieces, conference abstracts |

References

- Min, H.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Smith, L.; Rahmati, M.; et al. Global Incidence and Prevalence of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2024, 55, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.D.J.; Leow, Y.J.; Vipin, A.; Sandhu, G.K.; Kandiah, N. Associations Between GFAP, Aβ42/40 Ratio, and Perivascular Spaces and Cognitive Domains in Vascular Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.D.J.; Leow, Y.J.; Vipin, A.; Kumar, D.; Kandiah, N. Impact of White Matter Hyperintensities on domain-specific cognition in Southeast Asians. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e082267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.D.J.; Chan, C.K.M.; Chua, W.Y.; Chao, Y.; Chan, L.; Tan, E.K. A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Risk of Venous Thromboembolic Events in Parkinson’s Patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.Y.; Wang, J.D.J.; Chan, C.K.M.; Chan, L.; Tan, E.K. Risk of aspiration pneumonia and hospital mortality in Parkinson disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Gu, M.; Hong, C.; Zou, X.-Y.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Yuan, Y.; Qiu, C.-Y.; Lu, M.-P.; Cheng, L. Integrated machine learning and bioinformatic analysis of mitochondrial-related signature in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiresan, D.S.; Balasubramani, R.; Marudhachalam, K.; Jaiswal, P.; Ramesh, N.; Sureshbabu, S.G.; Puthamohan, V.M.; Vijayan, M. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Advances in Mitochondrial Biology. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 6827–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, X.; Wechter, N.; Gray, S.; Mohanty, J.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Olfactory dysfunction in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, V.; Chua, A.J.; Bleier, B.S.; Amiji, M.M. Effective Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Blood-Brain Barrier Impermeant Anti-IL-1β Antibody via the Minimally Invasive Nasal Depot (MIND) Technique. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 69103–69113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zou, J.; Sun, Z.; Pu, Y.; Qi, W.; Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Yuan, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; et al. Nasal microbiome in relation to olfactory dysfunction and cognitive decline in older adults. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, E.Y.; Tan, B.K.J.; Chan, K.L.; Chia, C.X.Y.; Tan, J.-W.; Yeo, B.S.Y. Chronic rhinosinusitis and cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rhinol. J. 2025, 63, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.-S.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, D.-K. A Longitudinal Study Investigating Whether Chronic Rhinosinusitis Influences the Subsequent Risk of Developing Dementia. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Nie, M.; Wang, B.; Duan, S.; Huang, Q.; Wu, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Han, Y. Intrinsic brain abnormalities in chronic rhinosinusitis associated with mood and cognitive function. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1131114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Edwards, T.S.; Hinson, V.K.; Soler, Z.M. Prevalence of Rhinorrhea in Parkinson Disease. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, e75–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, A.; Xavier, L.d.L.; Bernstein, J.D.; Simonyan, K.; Bleier, B.S. Association of Sinonasal Inflammation with Functional Brain Connectivity. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.-S.; Choi, H.-G.; Wee, J.-H. Chronic rhinosinusitis and progression of cognitive impairment in dementia. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2021, 138, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, J.H.; Yoo, D.M.; Byun, S.H.; Hong, S.J.; Park, M.W.; Choi, H.G. Association between neurodegenerative dementia and chronic rhinosinusitis: A nested case-control study using a national health screening cohort. Medicine 2020, 99, e22141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, N.R.; Schlosser, R.J.; Storck, K.A.; Ganjaei, K.G.; Soler, Z.M. The impact of medical therapy on cognitive dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, F.; Schlosser, R.J.; Storck, K.A.; Ganjaei, K.G.; Rowan, N.R.; Soler, Z.M. Effects of endoscopic sinus surgery on objective and subjective measures of cognitive dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domellöf, M.E.; Lundin, K.-F.; Edström, M.; Forsgren, L. Olfactory dysfunction and dementia in newly diagnosed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 38, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, L.J.; Chandra, R.K.; Li, P.; Turner, J.H. Role of tissue eosinophils in chronic rhinosinusitis–associated olfactory loss. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, J.A.; Mace, J.C.; Smith, T.L.; Soler, Z.M. Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Improves Cognitive Dysfunction in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, T.; Kikuchi, A.; Hirayama, K.; Nishio, Y.; Hosokai, Y.; Kanno, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Sugeno, N.; Konno, M.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Severe olfactory dysfunction is a prodromal symptom of dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease: A 3 year longitudinal study. Brain J. Neurol. 2012, 135, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, K.L.; Koeppe, R.A.; Bohnen, N.I. Rhinorrhea: A common nondopaminergic feature of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2011, 26, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Vojvodić, D.; Radulović, V.; Vukomanović-Đurđević, B.; Miljanović, O. Correlation between cytokine levels in nasal fluid and eosinophil counts in nasal polyp tissue in asthmatic and non-asthmatic patients. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2011, 39, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H.; Hung, Y.-W.; Hung, W.; Lan, M.-Y.; Yeh, C.-F. Murine model of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis inducing neuroinflammation and olfactory dysfunction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 325–339.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, G.; Ramirez, V.; Engen, P.A.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Green, S.J.; Mahdavinia, M.; Batra, P.S.; Tajudeen, B.A.; Keshavarzian, A. Deep nasal sinus cavity microbiota dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.H.; Yeon, S.H.; Choi, M.R.; Jang, Y.S.; Kim, J.A.; Oh, H.W.; Jun, X.; Park, S.K.; Heo, J.Y.; Rha, K.-S.; et al. Altered Mitochondrial Functions and Morphologies in Epithelial Cells Are Associated with Pathogenesis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, J.A.; Sautter, N.B.; Mace, J.C.; Detwiller, K.Y.; Smith, T.L. Antisomnogenic cytokines, quality of life, and chronic rhinosinusitis: A pilot study. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, E107–E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.P.; Turner, J.; May, L.; Reed, R. A genetic model of chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory inflammation reveals reversible functional impairment and dramatic neuroepithelial reorganization. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 2324–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.D.J.; Chua, N.Y.M.; Chan, L.-L.; Tan, E.-K. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Parkinson’s Disease: Bidirectional Clinical and Pathophysiologic Links. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’aNdrea, F.; Tischler, V.; Dening, T.; Churchill, A. Olfactory stimulation for people with dementia: A rapid review. Dementia 2022, 21, 1800–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, R.; Khan, T.; Reyes, D. A Prospective Study: Clinical Significance of Anticholinergic Nasal Sprays in Patients with Parkinson Disease Afflicted by Rhinorrhea (P04.149). Neurology 2013, 80, P04.149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, J.M.; Segal, B.M.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Lalor, S.J. Respiratory tract Moraxella catarrhalis and Klebsiella pneumoniae can promote pathogenicity of myelin-reactive Th17 cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2023, 16, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongianni, M.; Catalan, M.; Perra, D.; Fontana, E.; Janes, F.; Bertolotti, C.; Sacchetto, L.; Capaldi, S.; Tagliapietra, M.; Polverino, P.; et al. Olfactory swab sampling optimization for α-synuclein aggregate detection in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzkina, A.; Rößle, J.; Seger, A.; Panzer, C.; Kohl, A.; Maltese, V.; Musacchio, T.; Blaschke, S.J.; Tamgüney, G.; Kaulitz, S.; et al. Combining skin and olfactory α-synuclein seed amplification assays (SAA)—Towards biomarker-driven phenotyping in synucleinopathies. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, S.; Kang, J.-H.; Minn, Y.-K.; Park, H.; Choi, S.H. Amyloid beta in nasal secretions may be a potential biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-J.; Son, G.; Bae, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, Y.K.; Park, D.; Baek, S.Y.; Chang, K.-A.; Suh, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-B.; et al. Longitudinal profiling of oligomeric Aβ in human nasal discharge reflecting cognitive decline in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Peters, A.T.; Stevens, W.W.; Schleimer, R.P.; Tan, B.K.; Kern, R.C. Endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: Relationships to disease phenotypes, pathogenesis, clinical findings, and treatment approaches. Allergy 2022, 77, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readhead, B.; Haure-Mirande, J.-V.; Funk, C.C.; Richards, M.A.; Shannon, P.; Haroutunian, V.; Sano, M.; Liang, W.S.; Beckmann, N.D.; Price, N.D.; et al. Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron 2018, 99, 64–82.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochfort, K.D.; Collins, L.E.; McLoughlin, A.; Cummins, P.M. Tumour necrosis factor-α-mediated disruption of cerebrovascular endothelial barrier integrity in vitro involves the production of proinflammatory interleukin-6. J. Neurochem. 2016, 136, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotan, D.; Tatar, A.; Aygul, R.; Ulvi, H. Assessment of nasal parameters in determination of olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 2013, 41, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ran, M.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, K.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, S. New insight into neurological degeneration: Inflammatory cytokines and blood–brain barrier. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1013933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leon, M.J.; Li, Y.; Okamura, N.; Tsui, W.H.; Saint-Louis, L.A.; Glodzik, L.; Osorio, R.S.; Fortea, J.; Butler, T.; Pirraglia, E.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Clearance in Alzheimer Disease Measured with Dynamic PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1471–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C.; Hicks, A.; Gane, S.; Peters, A.T.; Gevaert, P.; Nash, S.; Horowitz, J.E.; Sacks, H.; Jacob-Nara, J.A. The interleukin-4/interleukin-13 pathway in type 2 inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Front. Immunol. 2024, 1356298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victores, A.J.; Chen, M.; Smith, A.; Lane, A.P. Olfactory loss in chronic rhinosinusitis is associated with neuronal activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 8, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.; Troscianko, E.T.; Woo, C.C. Inflammation and olfactory loss are associated with at least 139 medical conditions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1455418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, C.M.; Singh, A.K.; Ali, A.; Tseng, S.C.; Syal, K.; Ringelberg, K.J.; Ho, Y.-H.; Hintermair, C.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kar, R.K.; et al. Noncanonical CTD kinases regulate RNA polymerase II in a gene-class-specific manner. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F.; Butterfield, D.A. mTOR signaling in aging and neurodegeneration: At the crossroad between metabolism dysfunction and impairment of autophagy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 84, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Bai, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential in depression. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; So, K.-F.; Zhang, L. Physical exercise mediates a cortical FMRP–mTOR pathway to improve resilience against chronic stress in adolescent mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qiu, C.-Y.; Tao, Y.-J.; Cheng, L. Epigenetic modifications in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1089647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Sahu, M.; Srivastava, D.; Tiwari, S.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Post-translational modifications: Regulators of neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, R.K.; Hanner, A.S.; Starost, M.F.; Springer, D.; Mastracci, T.L.; Mirmira, R.G.; Park, M.H. Neuron-specific ablation of eIF5A or deoxyhypusine synthase leads to impairments in growth, viability, neurodevelopment, and cognitive functions in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Kar, R.K.; Banka, S.; Ziegler, A.; Chung, W.K. Post-translational formation of hypusine in eIF5A: Implications in human neurodevelopment. Amino Acids 2022, 54, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qiu, T.; Wei, G.; Que, Y.; Wang, W.; Kong, Y.; Xie, T.; Chen, X. Role of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 852272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, T.S. Post-translational regulation of inflammasomes. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 14, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Do, D.C.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Qu, J.; Ke, X.; Luo, X.; Tang, H.M.; Tang, H.L.; Hu, C.; et al. Functional role of kynurenine and aryl hydrocarbon receptor axis in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 586–600.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Mei, Q.; Niu, R. Oxidative CaMKII as a potential target for inflammatory disease (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.H.; Sadredini, M.; Hasic, A.; Anderson, M.E.; Sjaastad, I.; Stokke, M.K. CaMKII and reactive oxygen species contribute to early reperfusion arrhythmias, but oxidation of CaMKIIδ at methionines 281/282 is not a determining factor. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2023, 175, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Thota, S.; Abdulkadir, A.; Kaur, G.; Bagam, P.; Batra, S. NADPH oxidase family proteins: Signaling dynamics to disease management. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 660–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.R.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.H.; Kim, J.S.; Chae, C.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, H.J. Ethanol-activated CaMKII signaling induces neuronal apoptosis through Drp1-mediated excessive mitochondrial fission and JNK1-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashpole, N.M.; Song, W.; Brustovetsky, T.; Engleman, E.A.; Brustovetsky, N.; Cummins, T.R.; Hudmon, A. Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II (CaMKII) Inhibition Induces Neurotoxicity via Dysregulation of Glutamate/Calcium Signaling and Hyperexcitability. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 8495–8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sałaciak, K.; Koszałka, A.; Żmudzka, E.; Pytka, K. The Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinases II and IV as Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.H.; Chung, K.C. Death-associated Protein Kinase 1 Phosphorylates α-Synuclein at Ser129 and Exacerbates Rotenone-induced Toxic Aggregation of α-Synuclein in Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells. Exp. Neurobiol. 2020, 29, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M.S. Role of DAPK1 in neuronal cell death, survival and diseases in the nervous system. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 74, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xia, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, D.; Gan, C.-L.; Wang, L.; Mei, Y.; Lan, G.; Shui, X.; Tian, Y.; et al. Death-associated protein kinase 1 mediates Aβ42 aggregation-induced neuronal apoptosis and tau dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, A.; Schneider, B.L.; Aebischer, P.; Lashuel, H.A. Polo-like kinase 2 regulates selective autophagic alpha-synuclein clearance and suppresses its toxicity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3945–E3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, B.; Liou, L.-C.; Ren, Q.; Huang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Witt, S.N. α-Synuclein disrupts stress signaling by inhibiting polo-like kinase Cdc5/Plk2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16119–16124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.C.; Lam, W.Y.; Chung, K.K.K. The role of polo-like kinases 2 in the proteasomal and lysosomal degradation of alpha-synuclein in neurons. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gata, A.; Neagoe, I.B.; Leucuta, D.-C.; Budisan, L.; Raduly, L.; Trombitas, V.E.; Albu, S. MicroRNAs: Potential Biomarkers of Disease Severity in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Medicina 2023, 59, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Peng, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, F.; Lu, X.; Geng, D.; Li, M. MicroRNA-145-5p Regulates the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Nasal Polyps by Targeting Smad3. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 17, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Kang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, Q.; Dai, D.; Ye, J. Gene Expression Profiles of Circular RNAs and MicroRNAs in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 643504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zheng, X.; Xing, X.; Bi, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.; Wei, L.; Jin, Y.; Xu, S. Advances in autonomic dysfunction research in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1468895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, H.; Biaggioni, I. Autonomic failure in neurodegenerative disorders. Semin. Neurol. 2003, 23, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, E.; Laks, J. Alzheimer disease neuropathology:understanding autonomic dysfunction. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2008, 2, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, P.; Shukla, S.; Mondal, M.; Kar, R.K.; Siddiqui, J.A. The nexus of long noncoding RNAs, splicing factors, alternative splicing and their modulations. RNA Biol. 2024, 21, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Lu, J. Apoptosis and turnover disruption of olfactory sensory neurons in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1371587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, S.; Cha, X.; Li, F.; Xu, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Ren, W. Aging and chronic inflammation: Impacts on olfactory dysfunction-a comprehensive review. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Fujinami, R.S.; White, H.S.; Preux, P.-M.; Blümcke, I.; Sander, J.W.; Löscher, W. Infections, inflammation and epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.-H.; Hung, T.-W.; Tsai, J.-D.; Chen, H.-J.; Liao, P.-F.; Sheu, J.-N. Children with allergic rhinitis and a risk of epilepsy: A nationwide cohort study. Seizure 2020, 76, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, R.K. Recent Insights of Molecular Approaches to Study Brain Tumor Associated Seizure and Epilepsy. In Iterative International Publishers (IIP), 1st ed.; Selfypage Developers Pvt Ltd.: Chikkamagaluru, India, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lau, C.Y.; Ma, F.; Zheng, C. Genome-wide screen identifies curli amyloid fibril as a bacterial component promoting host neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2106504118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, D.O.; Mika, F.; Richter, A.M.; Hengge, R. The green tea polyphenol EGCG inhibits E. coli biofilm formation by impairing amyloid curli fibre assembly and downregulating the biofilm regulator CsgD via the σE-dependent sRNA RybB. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 101, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consonni, A.; Miglietti, M.; De Luca, C.M.G.; Cazzaniga, F.A.; Ciullini, A.; Dellarole, I.L.; Bufano, G.; Di Fonzo, A.; Giaccone, G.; Baggi, F.; et al. Approaching the Gut and Nasal Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease in the Era of the Seed Amplification Assays. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, C.; Serrano, G.E.; Intorcia, A.J.; Mariner, M.R.; Sue, L.I.; Arce, R.A.; Atri, A.; Adler, C.H.; Belden, C.M.; Shill, H.A.; et al. Olfactory Bulb Amyloid-β Correlates with Brain Thal Amyloid Phase and Severity of Cognitive Impairment. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Qian, J.; Muzikansky, A.; Monsell, S.E.; Montine, T.J.; Frosch, M.P.; Betensky, R.A.; Hyman, B.T. Thal Amyloid Stages Do Not Significantly Impact the Correlation Between Neuropathological Change and Cognition in the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 75, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, I.; Ortiz-Terán, L.; Ng, T.S.C.; Albers, M.W.; Marshall, G.; Orwig, W.; Kim, C.-M.; Bueichekú, E.; Montal, V.; Olofsson, J.; et al. Tau propagation in the brain olfactory circuits is associated with smell perception changes in aging. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwood, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Card, D.; Craine, A.; Ryan, T.M.; Drew, P.J. Anatomical basis and physiological role of cerebrospinal fluid transport through the murine cribriform plate. eLife 2019, 8, e44278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, I.; Kim, C.; Mollanji, R.; Johnston, M. Cerebrospinal fluid outflow resistance in sheep: Impact of blocking cerebrospinal fluid transport through the cribriform plate. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2002, 28, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spera, I.; Cousin, N.; Ries, M.; Kedracka, A.; Castillo, A.; Aleandri, S.; Vladymyrov, M.; Mapunda, J.A.; Engelhardt, B.; Luciani, P.; et al. Open pathways for cerebrospinal fluid outflow at the cribriform plate along the olfactory nerves. eBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.; Zakharov, A.; Papaiconomou, C.; Salmasi, G.; Armstrong, D. Evidence of connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatic vessels in humans, non-human primates and other mammalian species. Cerebrospinal. Fluid Res. 2004, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollanji, R.; Bozanovic-Sosic, R.; Zakharov, A.; Makarian, L.; Johnston, M.G. Blocking cerebrospinal fluid absorption through the cribriform plate increases resting intracranial pressure. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 282, R1593–R1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Yamada, K.; Igarashi, H.; Kasuga, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Ikeuchi, T.; Nishizawa, M.; Kwee, I.L.; Nakada, T. Reduced CSF Water Influx in Alzheimer’s Disease Supporting the β-Amyloid Clearance Hypothesis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyka, M.B.; Wawrzyniak, P.; Eiwegger, T.; Holzmann, D.; Treis, A.; Wanke, K.; Kast, J.I.; Akdis, C.A. Defective epithelial barrier in chronic rhinosinusitis: The regulation of tight junctions by IFN-γ and IL-4. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 1087–1096.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Chandra, R.K.; Li, P.; Hull, B.P.; Turner, J.H. Olfactory and middle meatal cytokine levels correlate with olfactory function in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, E304–E310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amantea, D.; Petrelli, F.; Greco, R.; Tassorelli, C.; Corasaniti, M.T.; Tonin, P.; Bagetta, G. Azithromycin Affords Neuroprotection in Rat Undergone Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynnonen, M.A.; Venkatraman, G.; Davis, G.E. Macrolide Therapy for Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2013, 148, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Santamaria, G.; La Vitola, P.; Brandi, E.; Grandi, F.; Viscomi, A.R.; Beeg, M.; Gobbi, M.; Salmona, M.; Ottonello, S.; et al. Doxycycline counteracts neuroinflammation restoring memory in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 70, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, T.R.; Galpern, W.R.; Asante, A.; Arenovich, T.; Fox, S.H. Ipratropium bromide spray as treatment for sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 2268–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouri, S.M.; Chung, J.M.; Binder, E.F. Successful intervention to mitigate an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor-induced rhinorrhea prescribing cascade: A case report. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiago, A.; Binder, D.K. Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation on Autonomic Function. Brain Sci. 2016, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovick, T. Deep brain stimulation and autonomic control. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniyar, F.H.; Starr, P.; Goadsby, P.J. Paroxysmal sneezing after hypothalamic deep brain stimulation for cluster headache. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.-X.; Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.-G. Impact of Subthalamic Deep Brain Stimulation on Hyposmia in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease Is Influenced by Constipation and Dysbiosis of Microbiota. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 653833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, M.A. The Role of the Autonomic Nerves in the Control of Nasal Circulation. Neurosignals 1995, 4, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kanthasamy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Anantharam, V.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Preclinical and clinical outcomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Fang, J.; Dai, W.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, M. SS-31 Provides Neuroprotection by Reversing Mitochondrial Dysfunction after Traumatic Brain Injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4783602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.M.; Sharpley, M.S.; Manas, A.-R.B.; Frerman, F.E.; Hirst, J.; Smith, R.A.J.; Murphy, M.P. Interaction of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ with phospholipid bilayers and ubiquinone oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14708–14718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, J.R.; Jessica, R.S.-P.; Chelsea, A.C.S.; Nina, Z.B.; Lauren, M.C.; Hannah, L.R.; Kayla, A.; Chonchol, M.W.; Rachel, A.G.-R.; Michael, P.M.; et al. Chronic Supplementation with a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Func-tion in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertens. Dallas Tex 1979 2018, 71, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, A.V.; Liu, S.; Soong, Y.; Mills, W.; Singh, P.; Warren, J.D.; Seshan, S.V.; Pardee, J.D.; Szeto, H.H. The mitochondrial-targeted compound SS-31 Re-energizes ischemic mitochondria by interacting with cardiolipin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-Q.; Zuo, Q.-N.; Wang, T.; Xu, D.; Lian, L.; Gao, L.-J.; Wan, C.; Chen, L.; Wen, F.-Q.; Shen, Y.-C. Mitochondrial-Targeting Antioxidant SS-31 Suppresses Airway Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Induced by Cigarette Smoke. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6644238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, A.; Cervin-Hoberg, C.; Huygens, F.; Lindstedt, M.; Sakellariou, C.; Greiff, L.; Cervin, A. Upper airway microbiome transplantation for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023, 13, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junca, H.; Pieper, D.H.; Medina, E. The emerging potential of microbiome transplantation on human health interventions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, S. The Mitochondria-Targeted Micelle Inhibits Alzheimer’s Disease Progression by Alleviating Neuronal Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neuroinflammation. Small 2025, 21, e2408581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).