Abstract

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an important coenzyme essential for metabolism, energy production, gene regulation, and cellular communication. With aging, NAD+ levels decrease, which may be partly responsible for age-related disease and impaired function. While certain lifestyle practices may help to maintain NAD+, such as intermittent fasting, exercise, and reduced alcohol consumption, these activities do not appear to support optimal NAD+ levels. For this reason, numerous dietary supplements have emerged, with the claim of increasing NAD+ levels and resulting in improved health and, possibly, increased longevity. Such agents include NAD+, as well as the NAD+ precursors niacin, nicotinamide riboside (NR), and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN). This article discusses the scientific rationale and evidence for using such supplements, with a particular emphasis on human oral ingestion and associated health outcomes. The current literature has been reviewed, and practical applications are presented.

1. Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an important coenzyme used for multiple physiological purposes. By modulating NAD+-sensing enzymes, NAD+ controls hundreds of key cellular processes, including energy metabolism and cell survival [1]. NAD+ is found in all living cells, is a necessary pyridine nucleotide cofactor, and is involved in various biological processes. It acts as an electron carrier in converting energy from one form to another and in enzymatic reactions [2]. NAD+ is also used to produce adenosine triphosphate and initiate the repair of DNA [3] and is necessary for calcium-dependent secondary messengers, gene expression, and oxidative phosphorylation. NAD+ has garnered such interest in recent years that the “NAD World” theory has been proposed, describing a systemic regulatory network that connects NAD+ as a major player in metabolism, biological rhythm, and aging. The theory has expanded to view the essential communication between the hypothalamus and peripheral tissues. There is a new version known as NAD World 3.0 [4], which presents more detailed layers of feedback loops promoted by NMN and eNAMPT for longevity.

Unfortunately, NAD+ decreases with age, with a negative correlation noted between NAD+ levels and age in both males and females [5]. The lower tissue NAD+ levels have been noted in the brain, liver, pancreas, skin, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue, with NAD+ deficiency associated with the age-related mitochondrial dysfunction [6] and a disruption of nuclear–mitochondrial communication during aging [7]. Such alterations can negatively impact longevity and age-related health through NAD+’s functions in energy metabolism and activation of sirtuin proteins in mammalian tissue. In fact, this age-related decline of NAD+ is linked to human disease [8].

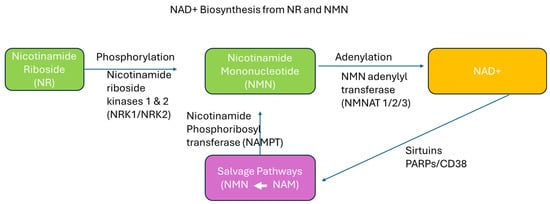

As a result of the noted problem of NAD+ being reduced with age, coupled with the fact that the reduction appears linked to untoward health effects, attempts to replenish NAD+ have been made. While NAD+ is found in certain foods, such as fish (salmon, tuna, and sardines), dairy milk, pork, beef, and turkey, the obtainable quantity in whole foods is relatively low. Therefore, individuals seeking to elevate NAD+ levels to combat age-related declines often look to dietary supplements. It has been proposed that supplementing with NAD+ precursors such as nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (β-NMN) provides a means to restore NAD+ levels and acts to therapeutically provide support to various body systems, including improved cognition [9]—a common concern for aging adults. Figure 1 illustrates the synthesis of NAD+ from the two precursors.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of NAD+ synthesis from nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN). NR and NMN serve as key precursors in the synthesis of NAD+. The enzymes NRK1/2 convert NR to NMN through phosphorylation, and NMNAT1-3 then catalyze the adenylation of NMN to form NAD+. The salvage pathway illustrated here shows how nicotinamide (NAM) is recycled back to NMN (white arrow) through the action of nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT), ensuring efficient NAD+ regeneration and maintenance of cellular NAD+ levels.

The present brief review discusses the use of precursor dietary supplements targeting increased NAD+ levels. Although actual NAD+ supplements are often touted as helpful by those marketing these products, the evidence suggests that overall absorption is relatively poor. In a similar manner, niacin is sometimes indicated as a dietary supplement to support NAD+ [10]. However, a scarcity of data exists to support the use of niacin solely for this purpose and to result in significant health improvements. Therefore, we focus exclusively on the use of NR and β-NMN in this review, as both have been reported to elevate blood concentrations of NAD+, with therapeutic potential [11] and the possible effect of aiding overall health [12].

Despite the growing popularity of NAD+ supplementation, there remain critical knowledge gaps. (1) There is limited clarity on how effectively different NAD+ precursors elevate NAD+ levels across various tissues. (2) The clinical significance of these changes—particularly whether supplementation translates to measurable improvements in health outcomes—remains poorly defined. (3) Confusion persists in the public sphere due to the aggressive marketing of NAD+ supplements without clear evidence of efficacy or optimal dosing strategies.

The objective of this brief review is to examine the cellular metabolic function of NAD+ and evaluate the current evidence regarding NR and β-NMN supplementation, focusing on their ability to raise NAD+ levels, their potential therapeutic benefits, and the limitations of current data. By doing so, we aim to provide a clearer understanding of the state of the science and identify key areas for future research.

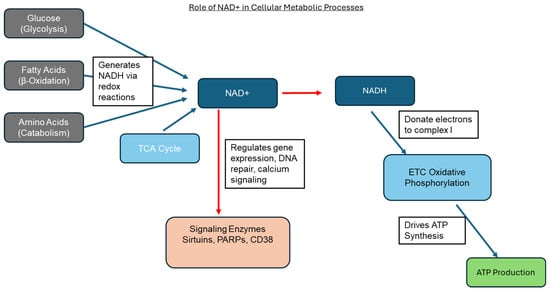

2. Role of NAD+ in Cellular Metabolic Processes

NAD+ is a vital coenzyme in all living cells and serves as a central metabolic regulator through two primary roles: (1) acting as a redox cofactor in metabolic reactions and (2) functioning as a signaling molecule involved in regulating enzymes that control gene expression, DNA repair, and stress response [13].

As a redox cofactor, NAD+ plays a critical role in the catabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins by acting as an electron carrier in oxidation–reduction reactions. It alternates between its oxidized form (NAD+) and reduced form (NADH) [14,15]. In the cytoplasm, NAD+ accepts electrons during glycolysis, particularly in the step where glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is converted to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, resulting in the production of NADH. In the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, NAD+ is required at three key steps, where it is reduced to NADH. Similarly, during the breakdown of fatty acids, NAD+ acts as an electron acceptor, especially at the beta-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase step, generating NADH for oxidative phosphorylation. Several amino acid degradation pathways also rely on NAD+ as an essential electron acceptor. The NADH generated from glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and beta oxidation donates electrons to complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This electron transfer drives the pumping of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane, generating a proton gradient that powers ATP synthase to produce ATP. Thus, NAD+ is indispensable for efficient oxidative phosphorylation and overall cellular energy production [14,15].

In addition to its role in energy metabolism, NAD+ plays a critical role in anabolic pathways through its phosphorylated form, NADP+/NADPH. NADP provides reducing equivalents required for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis, as well as for the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the glutathione reduction system.

As a signaling molecule, NAD+ plays critical roles as a substrate for enzymes that regulate essential cellular processes, including aging, stress response, and genomic stability [16]. Among these, sirtuins (SIRT1-7) are a family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases that regulate gene expression, mitochondrial biogenesis, and stress responses. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) use NAD+ to repair DNA damage through poly-ADP-ribosylation, a process vital for maintaining genomic integrity. Additionally, CD38 and CD157 consume NAD+ to generate cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR), a signaling molecule involved in calcium signaling and immune regulation [13]. In contrast, sterile alpha and TIR motif-containing protein consumes NAD+ during axon degeneration, linking NAD+ metabolism to neurodegenerative disease. During aging, NAD+ levels decline due to increased activity of NAD+-consuming enzymes such as PARPs and CD38, along with decreased expression of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme in the NAD+ salvage pathway. This age-related decline of NAD+ at the cellular level results in mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired DNA repair, and reduced sirtuin activity, ultimately increasing susceptibility to age-related disease, including metabolic syndrome, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular disorders [16] (please see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram summarizing the role of NAD+ in cellular processes. This image illustrates how NAD+ is central to glycolysis, β-oxidation, amino acid catabolism, and the TCA cycle, which feed into the electron transport chain for ATP production and also serve as substrates for signaling enzymes such as sirtuins, PARPs, and CD38 (red arrows).

3. Nicotinamide Riboside (NR)

Nicotinamide riboside (NR) has become one of the most studied NAD+ precursors [17], due to its potential health benefits and well-tolerated profile. NR is technically a member of the B vitamin family (B3), which also includes niacin and niacinamide. It has been suggested to have multiple physiological effects, possibly impacting cellular aging [18] and longevity [19], brain health and cognitive function [20], the inflammatory response [21], skeletal muscle [22], and cardiovascular health [23]. Others have reported that NR supplementation in mammalian cells and mouse tissues increases NAD+ levels and activates the sirtuin family, such as SIRT1 and SIRT3, leading to enhanced oxidative metabolism, in addition to protection against high-fat-diet-induced metabolic abnormalities [24]. Specifically, NR has been recently shown to activate one of the key sirtuins, SIRT5 [25], which may have implications in pursuing future targets to improve metabolic health. What is most well-described is the fact that NR has been reported to elevate levels of NAD+, which is important in maintaining normal metabolic function. In fact, the bioavailability of NR appears very good, with NAD+ in human blood increasing as much as 2.7-fold with a single oral dose of NR [26].

As a dietary supplement, NR is often marketed as an anti-aging product due to the proposed impact on elevating levels of NAD+. Related to this, NR is thought to improve cognitive function, modulated in part by upregulation of proliferator-activated-γ coactivator 1α-mediated β-secretase 1(BACE-1) ubiquitination and degradation, which may prevent amyloid-beta-protein (Aβ) production in the brain [20]. NR is found in small quantities within vegetables and fruits, as well as yeast, meat, and dairy milk. However, if meaningful elevations in NAD+ are to be achieved, higher quantities of NR are needed, often in the range of 500–2000 mg daily (based on human clinical trial data). The text below highlights some of the current findings specific to NR supplementation, with an initial focus on animal data, followed by a brief review of human clinical trials.

3.1. Animal Studies of NR

Oral intake of NR has been shown to elevate mouse hepatic NAD+ with superior pharmacokinetics compared to nicotinic acid and nicotinamide [26]. In animal models, NR has been investigated for its impact on a variety of health-specific outcomes, ranging from improved cardiac function to enhanced exercise performance.

Metabolic impairment in cardiac tissue is a major feature in chronic heart failure, making NAD+ a potential therapeutic target [13]. Hence, investigators have studied the role of NR to improve cardiac function. In a mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy, NR supplementation increased myocardial levels of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide, methylnicotinamide, and N1-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide, resulting in an attenuation of heart failure development [23]. In another study using rats, pretreatment with NR (200 mg/kg for 3 h) significantly reduced myocardial infarct area, decreased myocardial enzymes such as creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and improved cardiac function following ischemia–reperfusion injury [27]. Similarly, supplementation with NR was reported to improve heart function and extend the lifespan of mice lacking the cardiac nuclear receptors REV-ERBs [28], which are key regulators of Bmal1 expression for the molecular circadian clock. These findings suggest that boosting NAD+ levels through NR can improve cardiac function, particularly in a setting of heart failure linked to circadian clock disruption. Furthermore, administration of NR was shown to prevent lung and heart injury, as well as improve the survival rate in sepsis, possibly by inhibiting high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) release and oxidative stress via NAD+/SIRT1 signaling [29]. More recently, NR demonstrated cardioprotective effects in a drug-induced cardiotoxic environment [30].

While these findings are encouraging, conflicting results have been reported. For example, in one study, rats receiving a daily dose of NR at 300 mg/kg body weight/day for 21 days via gavage did not experience improved swimming performance as compared to the placebo. In fact, animals receiving NR appeared to perform worse than those animals receiving the placebo [31]. In contrast, another study reported that NR increased NAD+ levels in skeletal muscle and liver in mice, leading to enhanced exercise capacity and improved mitochondrial respiration [22]. Additional work is necessary to more fully elucidate the effects of NR on exercise performance and other outcomes linked to mitochondrial health.

3.2. Human Studies of NR

Research on NR in human subjects remains in its infancy, with the first clinical trial to test the safety and efficacy of supplementation being published within the last decade [32]. Close to 30 human studies have been conducted since, with mixed results. The variance in findings is likely linked to the eclectic subject populations tested, ranging from healthy adults to those who are obese and insulin-resistant to those with cardiac or renal disease [32]. Moreover, the daily dosage of NR provided varied widely from 250 to 2000 mg, as did the duration of treatment (from a single day to several weeks). Finally, the clinical outcomes vary across studies.

Differences across studies in the above items make it very difficult to draw comparisons and reach conclusions about the overall efficacy of NR, beyond its ability to increase blood concentrations of NAD+ [33,34], often in a dose-dependent manner [35]. Moreover, as with many dietary supplements, the claims for NR supplementation that are being purported in the marketplace are often not in line with the scientific evidence reported in clinical trials. Therefore, potential users of NR need to be vigilant in their evaluations of such claims and always seek to review the scientific evidence specific to NR supplementation.

Importantly, oral NR appears to elevate NAD+ levels and to be safe for human ingestion. In a 30-participant trial of patients with clinically stable heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, NR at a dose of 1000 mg twice daily appeared to be safe and well tolerated, and approximately doubled whole-blood NAD+ levels [36]. In support of these findings, Lapatto and colleagues noted that escalating dosages of NR (250–1000 mg/day) for 5 months improved systemic NAD+ metabolism, muscle mitochondrial number, myoblast differentiation, and gut microbiota composition in a sample of twins (mean age: ~40 years) [37].

However, a relatively high dose of NR (2000 mg/day) failed to improve the respiratory capacity of skeletal muscle mitochondria or increase the abundance of mitochondrial-associated proteins in a sample of obese and insulin-resistant men [38]. In a similar manner, NR at 1000 mg/day for one week was shown not to alter substrate metabolism at rest, during, or in recovery from endurance exercise, nor did NR alter NAD+-sensitive signaling pathways in human skeletal muscle in a sample of eight healthy men [39].

In contrast to the above, NR was shown to increase NAD+ levels in those with peripheral artery disease, while increasing the 6 min walk distance by 31 m [40]. Moreover, NR treatment was reported to improve isometric peak torque and the fatigue index in older but not younger men [41]. Findings such as this have spurred thought into the possible beneficial role of NR to support physical function in aging adults [42]. However, this may not translate into the preservation of skeletal muscle mass and function [43].

While positive effects of NR have been observed in both animal and human studies, benefits appear to be most pronounced in individuals with suboptimal baseline NAD+ levels. People with physiologically robust NAD+ levels may not require additional supplementation, and thus, NR use may offer little advantage beyond increasing blood NAD+ concentrations [44]. Reported benefits are largely limited to clinical populations with known diseases or possibly older adults. Moreover, while numerous positive findings have been documented in animal studies under various conditions, these observations may not directly translate to humans, as discussed previously.

4. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN)

β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) is a naturally occurring molecule and a nucleotide derived from ribose, nicotinamide, nicotinamide riboside, and niacin. Nucleotides are essential for DNA construction. As a dietary supplement, NMN has been sold for several years, touted as providing anti-aging benefits, based primarily on research findings supporting elevated NAD+ levels. Two anomeric forms of NMN exist: alpha and the active form, beta [45]. NMN directly participates in the synthesis of NAD+ in cells and has been used in several research studies to date. It is marketed and sold as a dietary supplement and is thought to be safe [46,47] and well-absorbed in the body, with a dose-dependent increase in NAD+ observed with NMN treatment [48].

NMN is converted by the body into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), and regular supplementation has been demonstrated to raise NAD+ levels [49] in both animals [50] and humans [49,51]. As mentioned previously, NAD+ is required for routine metabolism, converting food into cellular energy. The newer version of the NAD World 3.0 theory proposes that the significance of NMN has become more crucial as a key NAD+ intermediate [4].

As mentioned earlier, multiple studies demonstrate the decline in NAD+ with age and some with certain health conditions [52]. Moreover, low NAD+ levels have been connected to the advancement of neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders such as diabetes and liver disease. Like NR, the scientific community has a great deal of interest in NMN, as it has been shown to efficiently increase NAD+ levels in different tissues and lessen the risk of untoward metabolic conditions [52]. It is increasing in popularity and is viewed as a potential therapeutic for age-related ailments [53].

The impact of NMN may be partially explained by the observation that NAD+ activates sirtuins, which are associated with longevity and can assist in the repair of DNA. The effects of NMN are far-reaching, ranging from protection of brain tissue (oral gavage of 400 mg/kg of NMN effectively elevated NAD+ levels after 45 min in the brain of mice [50]) to reducing oxidative stress in cells and helping to avoid cognitive and cardiovascular problems [53,54]. In regard to muscle function and utilization of oxygen by muscles, NMN has been shown to improve aerobic capacity during exercise [55]. Taken together, it appears that NMN may impact multiple systems and may be a useful adjunctive therapy for improving overall health.

4.1. NMN Transport into Cells

It is now documented that NMN is transported into cells via the Slc12a8 NMN transporter [56]. When NAD+ levels fall, a signal is sent, and the expression of the Slc12a8 gene is upregulated. The Slc12a8 NMN transporter is specifically for NMN, acting to transport it into the cell, with conversion to NAD+ to follow via NMN/NaMN adenylyltransferases [17]. This helps cells to meet the critical need to manufacture NAD+. Once inside the cell and converted to NAD+, a host of benefits are possible, as briefly highlighted below in both animals and humans.

4.2. Animal Studies of NMN

There have been numerous animal studies performed with NMN, focusing on a wide range of metabolic health outcomes. For example, Mills and colleagues (2016) investigated the impact of 12 months of NMN administration in mice at doses of 100 and 300 mg/kg/day [57] to determine if NMN has a preventative effect on age-related physiological changes. It was demonstrated that NMN is quickly absorbed from the gut into the blood within 2 to 3 min and moves into tissues within 15 min. Moreover, NMN prevented age-associated gene expression changes in metabolic organs, while enhancing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mitonuclear protein imbalance in skeletal muscle. A more recent investigation [58] added NMN to the drinking water of mice and noted a marked increase in NAD+ levels, while inhibiting high-fat-diet-induced obesity and improving glucose tolerance and lipid metabolism. In another study involving NMN in the context of high-fat feeding in a mouse model [59], treatment improved the oocyte quality partially by restoring mitochondrial function and reducing DNA damage and levels of reactive oxygen species in oocytes. Perhaps more importantly, NMN restored the body weight of the offspring of mice consuming the high-fat-diet. Ru and colleagues (2022) demonstrated that NMN reduced the structural and functional decline in the intestine during aging, within a sample of mice [60]. Finally, a recent study demonstrated that NMN is protective against sepsis-induced memory dysfunction, as well as the inflammatory and oxidative injuries in the hippocampus region of septic mice [61]. Clearly, NMN has been shown to have a potential impact on a variety of areas related to overall health in animal models.

4.3. Human Studies of NMN

Several human studies to date have focused on NMN use, with a variety of encouraging findings, as presented below. Overall, it has been noted that NMN is well-absorbed, well-tolerated, and effective for specific metabolic functions. Irie and colleagues (2020) conducted an intake study in 10 men, with oral administration of NMN up to 500 mg as a single dose, which was reported to be safe and effectively metabolized, without causing any significant deleterious effects [62]. Igarashi et al. (2021) demonstrated that NMN was absorbed and significantly increased NAD+ levels [49].

In a study focused on women, NMN metabolites (NAD+, nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinic acid (NA)) and niacin metabolites (N-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carbox-amide and N-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide) were shown to be increased in plasma after 10 weeks of NMN administration, but not in the placebo group [63]. The study administered NMN to determine the effect on metabolic function. A hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp was used to evaluate insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. Skeletal muscle insulin signaling (phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR) was also analyzed. The quadriceps muscle tissue was sampled 1.5 h after the last supplementation of NMN or the placebo to determine NMN metabolites. NMN supplementation and not the placebo increased the metabolites, N-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carbox-amide, and N-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide. The authors proposed that NMN augmented muscle NAD+ turnover and that NMN intake also elevated muscle insulin signaling (increase in insulin-stimulated phosphorylated AKT and mTOR) and muscle insulin sensitivity.

Kim et al. (2022) performed a double-blind, parallel-design, placebo-controlled study with NMN provided to middle-aged and older adults. The investigators noted that by improving sleep, NMN was shown to improve both cognitive function and physical performance [64], both of which have implications for a wide variety of individuals.

Huang (2022) performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study administering NMN for 30 and 60 days [65]. The results showed that NMN increased cellular NAD+ levels, which was associated with heightened energy. Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) scores were evaluated, and it was found that values for the NMN group had no change, while the placebo group was worse. It was proposed that there was an anti-aging effect, since NMN entered the cells to increase energy levels and positively affected blood sugar levels.

Yi (2023) performed a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-dependent study to reveal the efficacy and safety of β-NMN supplementation in healthy middle-aged adults [51]. Interestingly, the blood biological age increased significantly in the placebo group but stayed unchanged with NMN supplementation, with the 6 min walk time increasing following NMN supplementation. Aside from these positive changes, the authors concluded that NMN supplementation increased blood NAD concentrations and is also safe and well-tolerated, even at dosing up to 900 mg daily.

Katayoshi and colleagues (2023) demonstrated that after 12 weeks of supplementation in a sample of healthy adults, NMN provided at 250 mg/day was well-tolerated and effectively elevated NAD+ metabolism [66]. The NMN group tended to reduce pulse wave velocity values, which shows reduced arterial stiffness, which may have implications for improved cardiovascular health.

Finally, from a physical performance perspective, NMN at dosages of 600 mg and 1200 mg increases the aerobic capacity of amateur runners during exercise training, with the authors suggesting that the improvement is likely a result of enhanced oxygen utilization within skeletal muscle [55].

5. Practical Applications and Conclusions

It is clear that NAD+ levels decline with age and may be lower in several clinical conditions—possibly also associated with aging. In such situations, use of an NAD+ booster may be appropriate, and both NR and NMN may be viable options. Both of these agents have been reported in multiple animal and human studies to elevate NAD+ and appear to do so in a dose-dependent manner. In terms of clinical efficacy, benefits appear to be specific to those with impaired health, often those with lowered levels of NAD+ and associated physical ailments. For these cases, use of either NR or NMN at a daily dosage of 500–1000 mg appears to consistently elevate NAD+. With this being said, while the data are fairly convincing that regular treatment leads to an elevation in NAD+ levels, what needs to be further evaluated is whether or not this increase translates into meaningful metabolic changes. Specifically, do humans feel and/or perform better as a result of treatment, or does the increase in NAD+ foster an improvement in overall metabolic health? These questions are what most users of NR and NMN desire answers to, not simply knowing that an increase in NAD+ levels is possible with treatment. There needs to be a functional benefit of using these supplements, and future research involving human subjects needs to focus more heavily on health-specific outcomes of treatment. Beyond this, such therapy should always be carried out in the context of a nutrient-dense diet and involvement in a regular, structured exercise program. Developing a lifestyle approach to healthy living, inclusive of physical activity, structured exercise, and adherence to a nutrient-dense diet, while possibly including the use of NR or NMN supplementation, should help to minimize the age-associated decline in physical and cognitive performance that is so prevalent in our society today—often owing to very poor self-care.

In conclusion, evidence from both animal and human studies demonstrates that supplementation with NAD+ precursors enhances energy metabolism and activates sirtuin/PARP/CD38 signaling, which may promote metabolic health and mitigate age-related cellular decline. These beneficial effects are mediated primarily through four key mitochondrial and bioenergetic mechanisms: (1) enhancement of mitochondrial bioenergetics by promoting oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and consequently increasing ATP production, (2) upregulation of SIRT3, a mitochondrial deacetylase that alleviates oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals and maintaining redox balance, (3) stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis via SIRT1-mediated activation of PGC-1α, which helps maintain mitochondrial dynamics—specifically, the balance between fission and fusion—through regulation of Drp1 expression, and (4) regulation of mitophagy, a mitochondrial quality control process that is often impaired during cellular aging.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, R.J.B. and J.Q.T.; writing—review and editing, R.J.B., J.Q.T. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended to Jackie Pence, who assisted with manuscript review and formatting.

Conflicts of Interest

R.J.B. has received research funding from dietary supplement companies and has served as a scientific advisor to dietary supplement companies, including CalerieLife. JQT is an employee of CalerieLife. CR claims no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Aβ | Amyloid-beta |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| BACE-1 | Beta-secretase 1 |

| CK-MB | Creatine kinase MB |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| eNAMPT | Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| HMGB1 | High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| HOMA | Homeostatic Model Assessment |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NaMN | Nicotinic acid mononucleotide |

| NMN | Nicotinamide mononucleotide |

| NR | Nicotinamide riboside |

| SIRT5 | Sirtuin 5 |

References

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gindri, I.D.M.; Ferrari, G.; Pinto, L.P.S.; Bicca, J.; Dos Santos, I.K.; Dallacosta, D.; Roesler, C.R.D.M. Evaluation of Safety and Effectiveness of NAD in Different Clinical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E417–E427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goody, M.F.; Henry, C.A. A Need for NAD+ in Muscle Development, Homeostasis, and Aging. Skelet. Muscle 2018, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S. NAD World 3.0: The Importance of the NMN Transporter and eNAMPT in Mammalian Aging and Longevity Control. npj Aging 2025, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massudi, H.; Grant, R.; Braidy, N.; Guest, J.; Farnsworth, B.; Guillemin, G.J. Age-Associated Changes in Oxidative Stress and NAD+ Metabolism in Human Tissue. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolla, T.A.; Denu, J.M. NAD+ Deficiency in Age-Related Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.P.; Price, N.L.; Ling, A.J.Y.; Moslehi, J.J.; Montgomery, M.K.; Rajman, L.; White, J.P.; Teodoro, J.S.; Wrann, C.D.; Hubbard, B.P.; et al. Declining NAD+ Induces a Pseudohypoxic State Disrupting Nuclear-Mitochondrial Communication during Aging. Cell 2013, 155, 1624–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata-Pérez, R.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Van Karnebeek, C.D.M.; Houtkooper, R.H. NAD+ Homeostasis in Human Health and Disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M. Supplementation with NAD+ and Its Precursors to Prevent Cognitive Decline across Disease Contexts. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, K.L.; Brenner, C. Nicotinic Acid, Nicotinamide, and Nicotinamide Riboside: A Molecular Evaluation of NAD+ Precursor Vitamins in Human Nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, J.; Baur, J.A.; Imai, S. NAD+ Intermediates: The Biology and Therapeutic Potential of NMN and NR. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, G.F.S.; Pastore, G.M. NAD+ Precursors Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotinamide Riboside (NR): Potential Dietary Contribution to Health. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.; Sedej, S.; Kroemer, G. NAD+ Metabolism in Cardiac Health, Aging, and Disease. Circulation 2021, 144, 1795–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusri, K.; Jose, S.; Vermeulen, K.S.; Tan, T.C.M.; Sorrentino, V. The Role of NAD+ Metabolism and Its Modulation of Mitochondria in Aging and Disease. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, W.; Hou, P.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, M.; Liu, S.; Feng, C.; Han, Y.; Li, P.; Shi, Y.; et al. NAD+ Metabolism-Based Immunoregulation and Therapeutic Potential. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as Regulators of Metabolism and Healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmel, M.; Jovanović, N.; Spitz, U. Nicotinamide Riboside—The Current State of Research and Therapeutic Uses. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, S.; Guarente, L. NAD+ and Sirtuins in Aging and Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biţă, A.; Scorei, I.R.; Ciocîlteu, M.V.; Nicolaescu, O.E.; Pîrvu, A.S.; Bejenaru, L.E.; Rău, G.; Bejenaru, C.; Radu, A.; Neamţu, J.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside, a Promising Vitamin B3 Derivative for Healthy Aging and Longevity: Current Research and Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidy, N.; Liu, Y. Can Nicotinamide Riboside Protect against Cognitive Impairment? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2020, 23, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Han, K.; Sack, M.N. Targeting NAD+ Metabolism to Modulate Autoimmunity and Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, P.M.; Huang, J.; Butic, A.; Perry, C.; Yardeni, T.; Tan, W.; Morrow, R.; Baur, J.A.; Wallace, D.C. Nicotinamide Riboside Alleviates Exercise Intolerance in ANT1-Deficient Mice. Mol. Metab. 2022, 64, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diguet, N.; Trammell, S.A.J.; Tannous, C.; Deloux, R.; Piquereau, J.; Mougenot, N.; Gouge, A.; Gressette, M.; Manoury, B.; Blanc, J.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Preserves Cardiac Function in a Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2018, 137, 2256–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Youn, D.Y.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Cen, Y.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Yamamoto, H.; Andreux, P.A.; Cettour-Rose, P.; et al. The NAD+ Precursor Nicotinamide Riboside Enhances Oxidative Metabolism and Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, A.M.; Rymarchyk, S.; Herrington, N.B.; Donu, D.; Kellogg, G.E.; Cen, Y. Nicotinamide Riboside Activates SIRT5 Deacetylation. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 4762–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trammell, S.A.J.; Schmidt, M.S.; Weidemann, B.J.; Redpath, P.; Jaksch, F.; Dellinger, R.W.; Li, Z.; Abel, E.D.; Migaud, M.E.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide Riboside Is Uniquely and Orally Bioavailable in Mice and Humans. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Tang, J.; Xie, H.; Liu, L.; Qin, Q.; Sun, B.; Qin, Z.; Sheng, R.; Zhu, J. Nicotinamide Riboside Attenuates Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via Regulating SIRT3/SOD2 Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierickx, P.; Carpenter, B.J.; Celwyn, I.; Kelly, D.P.; Baur, J.A.; Lazar, M.A. Nicotinamide Riboside Improves Cardiac Function and Prolongs Survival After Disruption of the Cardiomyocyte Clock. Front. Mol. Med. 2022, 2, 887733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, G.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Ni, R.; Wang, G.; Fan, G.-C.; Lu, Z.; Peng, T. Administration of Nicotinamide Riboside Prevents Oxidative Stress and Organ Injury in Sepsis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 123, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podyacheva, E.; Semenova, N.; Zinserling, V.; Mukhametdinova, D.; Goncharova, I.; Zelinskaya, I.; Sviridov, E.; Martynov, M.; Osipova, S.; Toropova, Y. Intravenous Nicotinamide Riboside Administration Has a Cardioprotective Effect in Chronic Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourtzidis, I.A.; Stoupas, A.T.; Gioris, I.S.; Veskoukis, A.S.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Tsantarliotou, M.; Taitzoglou, I.; Vrabas, I.S.; Paschalis, V.; Kyparos, A.; et al. The NAD+ Precursor Nicotinamide Riboside Decreases Exercise Performance in Rats. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2016, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, M.V.; Treebak, J.T. What Is Really Known about the Effects of Nicotinamide Riboside Supplementation in Humans. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhart, S.E.; Shireman, L.M.; Risler, L.J.; Anderson, G.D.; Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Raftery, D.; Tian, R.; Shen, D.D.; O’Brien, K.D. An Open-Label, Non-Randomized Study of the Pharmacokinetics of the Nutritional Supplement Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) and Its Effects on Blood NAD+ Levels in Healthy Volunteers. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conze, D.; Brenner, C.; Kruger, C.L. Safety and Metabolism of Long-Term Administration of NIAGEN (Nicotinamide Riboside Chloride) in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Healthy Overweight Adults. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellinger, R.W.; Santos, S.R.; Morris, M.; Evans, M.; Alminana, D.; Guarente, L.; Marcotulli, E. Repeat Dose NRPT (Nicotinamide Riboside and Pterostilbene) Increases NAD+ Levels in Humans Safely and Sustainably: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. npj Aging Mech. Dis. 2017, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Airhart, S.E.; Zhou, B.; Shireman, L.M.; Jiang, S.; Melendez Rodriguez, C.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Shen, D.D.; Tian, R.; O’Brien, K.D. Safety and Tolerability of Nicotinamide Riboside in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2022, 7, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapatto, H.A.K.; Kuusela, M.; Heikkinen, A.; Muniandy, M.; Van Der Kolk, B.W.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Pöllänen, N.; Sandvik, M.; Schmidt, M.S.; Heinonen, S.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Improves Muscle Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Satellite Cell Differentiation, and Gut Microbiota in a Twin Study. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollerup, O.L.; Chubanava, S.; Agerholm, M.; Søndergård, S.D.; Altıntaş, A.; Møller, A.B.; Høyer, K.F.; Ringgaard, S.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Lavery, G.G.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Does Not Alter Mitochondrial Respiration, Content or Morphology in Skeletal Muscle from Obese and Insulin-resistant Men. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocks, B.; Ashcroft, S.P.; Joanisse, S.; Dansereau, L.C.; Koay, Y.C.; Elhassan, Y.S.; Lavery, G.G.; Quek, L.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Philp, A.M.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Supplementation Does Not Alter Whole-body or Skeletal Muscle Metabolic Responses to a Single Bout of Endurance Exercise. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 1513–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.M.; Martens, C.R.; Domanchuk, K.J.; Zhang, D.; Peek, C.B.; Criqui, M.H.; Ferrucci, L.; Greenland, P.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ho, K.J.; et al. Publisher Correction: Nicotinamide Riboside for Peripheral Artery Disease: The NICE Randomized Clinical Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolopikou, C.F.; Kourtzidis, I.A.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Vrabas, I.S.; Koidou, I.; Kyparos, A.; Theodorou, A.A.; Paschalis, V.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Acute Nicotinamide Riboside Supplementation Improves Redox Homeostasis and Exercise Performance in Old Individuals: A Double-Blind Cross-over Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodero, C.; Saini, S.K.; Shin, M.J.; Jeon, Y.K.; Christou, D.D.; McDermott, M.M.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Anton, S.D.; Mankowski, R.T. Nicotinamide Riboside—A Missing Piece in the Puzzle of Exercise Therapy for Older Adults? Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 137, 110972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopidis, K.; Moriarty, F.; Bahat, G.; McLean, J.; Church, D.D.; Patel, H.P. The Effect of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide and Riboside on Skeletal Muscle Mass and Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2025, 16, e13799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelj, D.; Philp, A. NAD+ Therapeutics and Skeletal Muscle Adaptation to Exercise in Humans. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.S.S.; De-Souza, E.A. Of Mice and Men: Opposing Effects of Nicotinamide Riboside on Skeletal Muscle Physiology at Rest and during Exercise. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 2525–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Irie, J.; Mitsuishi, M.; Uchino, Y.; Nakaya, H.; Takemura, R.; Inagaki, E.; Kosugi, S.; Okano, H.; Yasui, M.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Long-Term Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation on Metabolism, Sleep, and Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Biosynthesis in Healthy, Middle-Aged Japanese Men. Endocr. J. 2024, 71, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhou, X.; Xu, K.; Liu, S.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J. The Safety and Antiaging Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide in Human Clinical Trials: An Update. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1416–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poddar, S.K.; Sifat, A.E.; Haque, S.; Nahid, N.A.; Chowdhury, S.; Mehedi, I. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide: Exploration of Diverse Therapeutic Applications of a Potential Molecule. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, M.; Nakagawa-Nagahama, Y.; Miura, M.; Kashiwabara, K.; Yaku, K.; Sawada, M.; Sekine, R.; Fukamizu, Y.; Sato, T.; Sakurai, T.; et al. Chronic Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation Elevates Blood Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Levels and Alters Muscle Function in Healthy Older Men. npj Aging 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, C.; Lackie, T.; Williams, D.H.; Simone, P.S.; Zhang, Y.; Bloomer, R.J. Oral Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Increases Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Level in an Animal Brain. Nutrients 2022, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Maier, A.B.; Tao, R.; Lin, Z.; Vaidya, A.; Pendse, S.; Thasma, S.; Andhalkar, N.; Avhad, G.; Kumbhar, V. The Efficacy and Safety of β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) Supplementation in Healthy Middle-Aged Adults: A Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Dose-Dependent Clinical Trial. GeroScience 2023, 45, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okabe, K.; Yaku, K.; Tobe, K.; Nakagawa, T. Implications of Altered NAD Metabolism in Metabolic Disorders. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, M.; Lalam, S.K. The Role of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) in Anti-Aging, Longevity, and Its Potential for Treating Chronic Conditions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9737–9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Ding, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, C.; Yang, G. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide: Research Process in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Hao, X.; Hu, M. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation Enhances Aerobic Capacity in Amateur Runners: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozio, A.; Mills, K.F.; Yoshino, J.; Bruzzone, S.; Sociali, G.; Tokizane, K.; Lei, H.C.; Cunningham, R.; Sasaki, Y.; Migaud, M.E.; et al. Slc12a8 Is a Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Transporter. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.F.; Yoshida, S.; Stein, L.R.; Grozio, A.; Kubota, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Redpath, P.; Migaud, M.E.; Apte, R.S.; Uchida, K.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Mitigates Age-Associated Physiological Decline in Mice. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Cai, X.; Xu, Y.; Rong, S.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Physiological Decline in Aging Mice. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wei, J.; Guo, F.; Li, L.; Han, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Improves Oocyte Quality of Obese Mice. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, M.; Wang, W.; Zhai, Z.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Kothari, D.; Niu, K.; Wu, X. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation Protects the Intestinal Function in Aging Mice and d-Galactose Induced Senescent Cells. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7507–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Sun, X.; Sun, C.; Yu, C.; Li, P.; Deng, X.; Wang, J. β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Activates NAD+/SIRT1 Pathway and Attenuates Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses in the Hippocampus Regions of Septic Mice. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irie, J.; Inagaki, E.; Fujita, M.; Nakaya, H.; Mitsuishi, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamashita, K.; Shigaki, S.; Ono, T.; Yukioka, H.; et al. Effect of Oral Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide on Clinical Parameters and Nicotinamide Metabolite Levels in Healthy Japanese Men. Endocr. J. 2020, 67, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Kayser, B.D.; Patti, G.J.; Franczyk, M.P.; Mills, K.F.; Sindelar, M.; Pietka, T.; Patterson, B.W.; Imai, S.-I.; et al. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Increases Muscle Insulin Sensitivity in Prediabetic Women. Science 2021, 372, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Seol, J.; Sato, T.; Fukamizu, Y.; Sakurai, T.; Okura, T. Effect of 12-Week Intake of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide on Sleep Quality, Fatigue, and Physical Performance in Older Japanese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. A Multicentre, Randomised, Double Blind, Parallel Design, Placebo Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Uthever (NMN Supplement), an Orally Administered Supplementation in Middle Aged and Older Adults. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 851698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayoshi, T.; Uehata, S.; Nakashima, N.; Nakajo, T.; Kitajima, N.; Kageyama, M.; Tsuji-Naito, K. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Metabolism and Arterial Stiffness after Long-Term Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).