Abstract

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health conditions in middle and late adulthood, contributing substantially to morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life. However, limited research has examined the mechanisms linking genetic predisposition and early protective environments to long-term mental health trajectories. Guided by a life course health development perspective, this study investigated how depression polygenic scores (G) and protective childhood family environments (E) interplay to shape depressive symptom trajectories from mid- to late adulthood. We analyzed longitudinal data of 14 waves from the Health and Retirement Study (1994–2020; N = 4817), estimating linear mixed-effects models of depressive symptoms using the validated CES-D scale. Early protective environments were measured by indicators of family structure stability, non-abusive and substance-free parenting, positive parent–child relationships, and parental support. Results showed that genetic predisposition and protective family environments jointly influence depression trajectories across the life course. Specifically, individuals with both low genetic risk and high environmental protection had the lowest depressive symptoms over time. Importantly, when only one favorable factor was present, protective family environments offered a stronger lifelong benefit than low genetic risk. These findings extend prior research by demonstrating that supportive childhood environments can mitigate genetic vulnerability, shaping healthier long-term mental health trajectories. This work underscores the need for early family-based interventions to reduce depression risk, enhance resilience, and promote longevity.

1. Introduction

Depression is a prevalent condition worldwide, affecting approximately 5% of adults [1,2]. It is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality and is projected to be the highest global burden of disease by 2030 [3,4,5]. In midlife, depression peaks in prevalence and contributes to premature mortality from suicide, alcohol, and drug use [6,7]. Among adults aged 60 and older, rates remain substantial (~5.7%). It is a common cause of emotional suffering and worsening quality of life in older adulthood [8,9,10,11]. Elevated depressive symptoms are associated with functional decline, cognitive impairment [8,9,12,13], and increased risk of dementia in older adults [14]. In the context of rapid global population aging, addressing depression takes on new urgency, as late-life depression contributes to increased healthcare utilization and higher mortality rates [8,9,12,13]. Given the lifelong impact of this global prevalence, investigating the antecedents of depression to foster healthy mental development has become more urgent than ever.

Despite this urgency, significant gaps remain in understanding how depression evolves into a chronic condition well into old age. There is a critical need to understand both risk and early protective factors that influence long-term depression trajectories. Emerging evidence suggests that depression reflects the interplay between genetic predispositions—such as polygenic risk—and early psychosocial environments, particularly the quality of early family life [15,16]. Yet few studies have considered these compound forces across midlife and late adulthood. This study addresses this gap by integrating polygenic risk for depression with protective family environments to examine how these factors jointly shape depressive symptoms from midlife into later life.

1.1. Nature (Genetics) and Depression

Depression has both genetic and environmental origins [17,18,19]. Research suggests a genetic susceptibility to the development of depression [20,21]. Twins and family studies first estimated heritability was 37–38% [22,23] or 29–49% [24,25]. With advances in molecular genetic studies of depression and other complex psychiatric phenotypes [26], the last two decades have witnessed burgeoning research in examining “specific alleles (i.e., alternative forms of DNA sequence at a specific locus) or genotypes (i.e., the combination of alleles at a given locus)” and candidate genes and their association with depression [26]. Recent GWASs (genome-wide association studies) provided new opportunities to investigate the genetics of depression. Hyde et al. [27] identified 15 genome-wide significant loci, while a second large GWAS meta-analysis illustrated 44 associated genetic loci [18], followed by another study yielding 102 genome-wide significant variants [28]. These GWAS findings collectively demonstrated that depression is highly polygenic. Polygenic scores (PGSs), “reflecting the aggregate effect of many genes,” are “summary measures of the additive effect of hundreds of thousands or millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the entire genome and provide a comprehensive index of an individual’s generic propensity for a trait” [29,30]. PGS thus enables researchers to quantify genetic risk on a continuous scale and examine its influence on mental health outcomes across the life course [28,31,32,33].

1.2. Nurture and Mental Health

Family is meant to be the first protective environment for young people. It provides love, care, compassion, warmth, and respect, which help children develop self-esteem, a sense of worth, positive emotions, and coping skills for lifelong health benefits and happiness [34,35]. The family environment offers an emotional atmosphere that may persist into late adulthood. Individuals often internalize their parents’ attitudes, emotions, and behaviors to “parent” themselves psychologically over the life course [36,37].

A protective family environment is an enriched, multifaceted social setting for children’s upbringing. It encompasses a wide range of essential characteristics, such as a stable family structure with the presence of married parents, functional caregivers restrained from risky behaviors like substance use and excessive drinking and drug abuse, and responsible and self-controlled shunning of harmful and abusive actions towards the child. Such caregivers purposefully bestow love, care, attention, devoted time, emotional and instrumental support, and constructive communications. These favorable features are normally chained together, co-existing to create a risk-free and protective environment.

When one or more protective factors are absent or weakened, a young person’s psychological well-being may be affected to varying degrees. According to the attachment theory, protective homes can foster a child’s sense of security through affectionate bonds with caregivers. Such bonds may prevent the development of negative feelings, such as anxiety, sadness, depression, and anger [38,39,40]. Protective family environments also provide emotional guidance and instrumental coping assistance, which may help mitigate emotional distress and enhance well-being. Resilience scholars further posit that these environments may foster children’s sense of control and promote problem- and emotion-focused coping skills to buffer against stress [41,42].

Protective family factors can individually or collectively operate throughout a person’s life. They help them enhance resilience at a young age, which is essential for stress- and adversity-coping and maintaining mental health across the life course [42,43,44,45,46]. Recent studies have shown that promotive familial factors have a lasting protective impact on mental health trajectories. They can mitigate depression development, especially during adolescence, midlife, and old adulthood, by buffering against the mounting stresses and vulnerability of these stages [15,47]. For example, exposure to a highly family-cohesive environment during childhood may reduce depressive CES-D scale (range: 0–9) by an average of 0.80 points from adolescence to middle adulthood [15]. Individuals with positive relationships with their parents in childhood appeared to have, on average, 4–7% fewer depressive symptoms on the CES-D-8 scale, compared to their counterparts who experienced poor parent–child relationships, from middle to late adulthood [47].

1.3. Nature–Nurture Coupling Forces and Depression Development

Early family environment is crucial in the manifestation of genetic susceptibility to depression [48]. Prior literature primarily employed twin and family data, genotypes, and candidate genes to examine gene (G)–environment (E) associations with depressive outcomes [26,49,50]. With few exceptions [51,52,53,54], primary attention was given to negative family factors [55], such as unstable family [56], childhood maltreatment [57,58,59], and early stressful [48,60] or adverse events [61,62,63], to investigate their connections with genetics in the development of life-stage-specific depression (e.g., in adolescence or early adulthood). These studies have provided important insights but left critical gaps: they rarely account for protective family influences, nor do they trace their joint effects with genetic factors across the adult life course.

Advancements in GWAS have enabled the use of polygenic scores (PGSs) to study the joint effects of genes and environmental factors on depression. For example, the British Avon project employed GWAS data and PGS and risky factors (e.g., maltreatment) to examine mental health outcomes in adolescence and early adulthood [64,65,66]. Yet, despite these advances, the literature still lacks longitudinal analyses that integrate polygenic factors with positive early family conditions to evaluate how such interplay contributes to depression trajectories well into mid- and late adulthood.

Evidence implies that depression development may have a complex etiology comprising genetic and environmental influences. From a life course health development perspective, social environments and experiences can “get under the skin early in life” [67,68]. Concurrently, genetic predisposition may “get out of skin” to interplay with family environment to affect the course of health development [17]. Moreover, protective family factors are not static; their buffering effects against depression vary with varying social circumstances, experiences, and stresses at different life stages [15,47].

However, we rarely know how early protective family factors intertwine with genetic factors to shape mental health trajectories across the life span from midlife to old age. Which combinations of family and genetic conditions (e.g., low G–low E risk versus high G–high E risk) are more beneficial to mitigate depression over time? Which life stages are more responsive to protective conditions? Although family and twin studies have suggested that environmental processes can outweigh familial heritability [17] for depression outcomes, little research has applied GWAS-based genetic factors to examine how the presence of one conducive condition (either gene or environment) mitigates differently the depression trajectory over time [26,69].

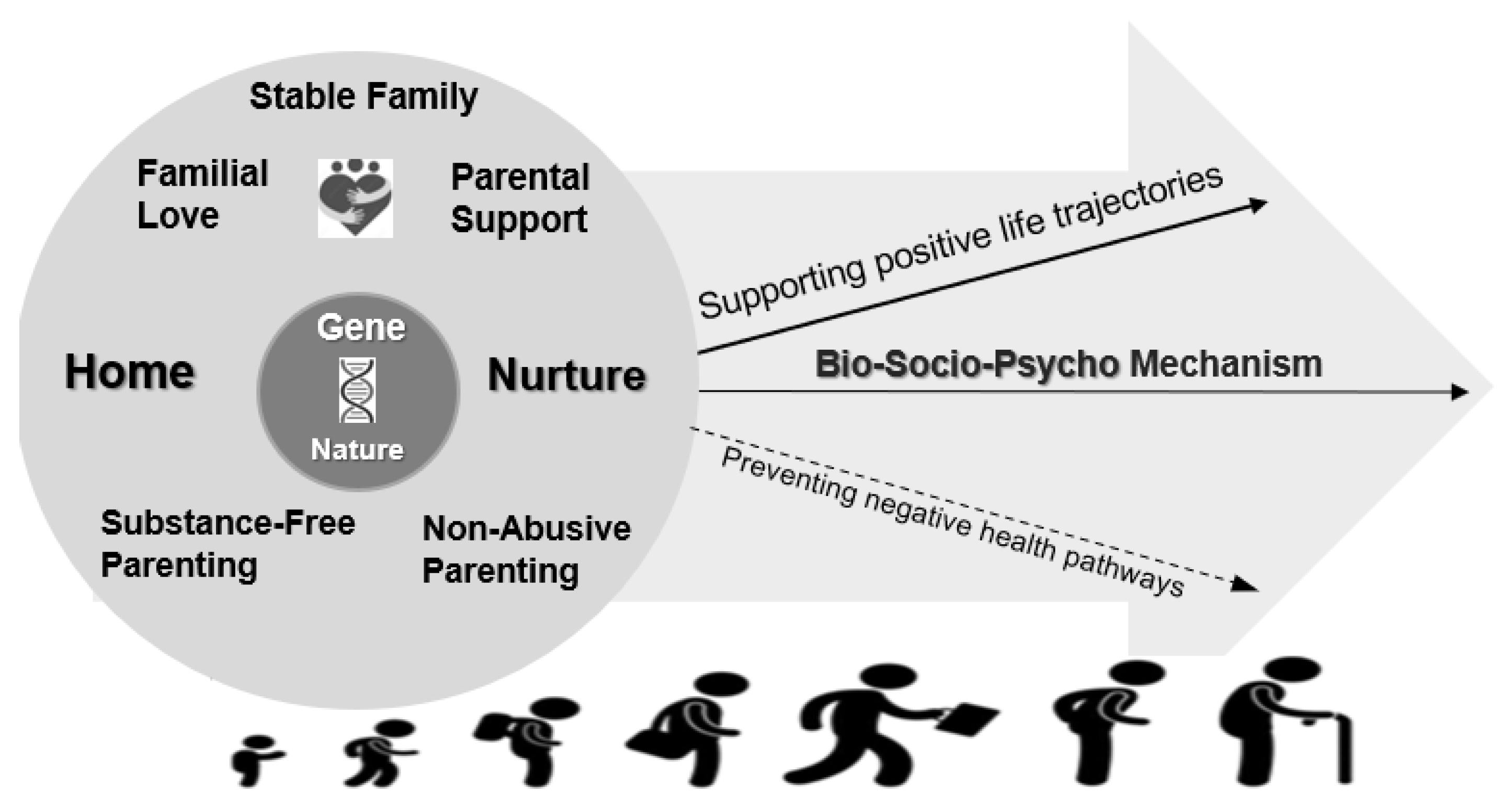

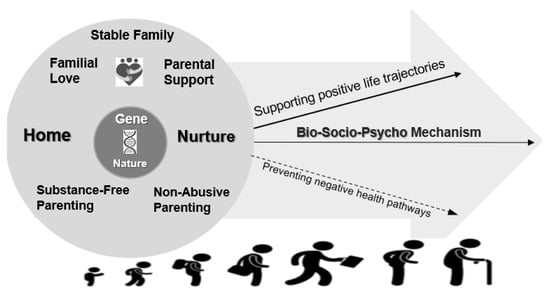

Figure 1 presents a general conceptual framework illustrating how the interplay between gene and family environments is associated with the biological, social, and psychological processes that shape mental health trajectories across the life course. Particularly, this study aimed to fill the critical voids in the literature by analyzing data from a national cohort study, the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Specifically, we apply a life course health development perspective to:

Figure 1.

Gene-early family protection and life course mental health development framework.

- Assess the association between polygenic scores and trajectories of depressive symptoms across ages 51–90 years;

- Decompose the complex early protective family environment, capturing a wide spectrum of characteristics from absence of risk and family stability to positive parenting (e.g., stable family structure, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive parent–child relationships, and parental support);

- Evaluate the impacts of these individual family factors, as well as the composite summary index of the overall family environment, on depression development;

- Investigate the gene–environment coupling roles in lifelong trajectories;

- Construct novel GxE compound measures to capture varying levels of genetic and family exposure;

- Compare whether only one favorable condition (G or E) shapes trajectories differently from middle to late adulthood.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

HRS is a continuing U.S. national study launched in 1992, including 15 waves of data until 2020, including around 26,000 individuals ages 51 to 90 years from middle to oldest old age [70,71,72,73]. The HRS began to collect salivary DNA in 2006. In HRS, genotyping was conducted using the Illumina HumanOmni2.5-4v1 array. These data were extracted from the dbGaP database (HRS 2012). Over 12,000 genotyped individuals had their genotype data pass CIDR’s quality control processing [74]. After quality control procedures, 9974 respondents were retained [75].

As there are well-documented problems associated with applying PGSs in diverse ancestry groups, participants of non-European ancestry were excluded to increase the ancestral homogeneity of the analytical samples [76,77,78]. This approach is consistent with other PGS studies that restrict analyses to samples of the European Ancestry Group (e.g., [79]). Because current genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of depression are based primarily on samples of European ancestry, polygenic scores derived from these GWAS have reduced predictive accuracy in other populations. Excluding non-European ancestry participants reduces potential bias and improves the validity of genetic prediction in this study. At the same time, this decision limits the generalizability of our findings, as results may not extend to individuals from other ancestral backgrounds.

As a result, the analysis sample consisted of individuals of European origins with quality GWAS data and no missing data on outcomes, exposure measures, and covariates (HRS N = 4817; see Supplementary Methods Section for details on sample derivation). In terms of sample statistics (Table 1), this U.S. HRS cohort consisted of 59% females and 51% males. The average age at baseline (Wave II) was 58.5 years. The enriched social, biological, genetic, and longitudinal data offered by HRS [70,80] provided an ideal basis for constructing the key measures employed by this study to explicate the mechanisms through which protective childhood family environment and genetic propensity jointly shape life course depression.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and study characteristics.

2.2. Depressive Symptoms

A summed CES-D score (range, 0–8) in HRS comprised of yes/no responses to eight CES-D items: (1) feeling depressed over the past week; (2) feeling like everything was an effort; (3) having restless sleep; (4) feeling unhappy; (5) feeling lonely; (6) not enjoying life; (7) feeling sad; and (8) could not get going [81,82]. The HRS CES-D scale was standardized. The CES-D was used longitudinally across 14 waves for growth curve linear mixed modeling. Participants in the analytical sample could have multiple depression measures over a 26-year period (1994–2020 biennial surveys), with Wave I (1992) excluded due to differences in item wording.

2.3. Depression Polygenic Score (PGS)

The PGS was constructed with PRSice-2 software [83]. To reduce redundancy, we first removed highly correlated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Specifically, SNPs with r2 > 0.1 within 250k base pairs of the index SNP were excluded. The PGS was based on findings from large genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of major depression [18,28,84]. This GWAS of about 500,000 individuals identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with depression. Each SNP had an estimated effect size, or weight (β), from the GWAS results. For each individual, a PGS was calculated as the weighted sum of the risk alleles of all included SNPs, weighted by their GWAS effect sizes:

where i denotes individual, j denotes SNP, β is the coefficient for SNP j estimated by GWAS, and Gij is the number of risk alleles j for individual i.

The PGS was then standardized with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. A higher PGS indicated a greater genetic propensity for depression. Principal components (PCs) of genetic ancestry were then constructed. To adjust for population differences, we also included the first 10 principal components (PCs) in all models [84].

2.4. Protective Childhood Family Environment

Five protective family factors captured enriched positive childhood and adolescent experiences: (1) stable family structure, (2) non-abusive parenting, (3) substance-free parenting, (4) positive family relationships, and (5) high paternal support (see details about the measurement in Supplementary Table S8) [15,47,51,85]. These five domains comprised measures of (1) living in a stable family characterized by married parents in childhood; (2) freedom from parental physical and sexual abuse; (3) living with parents free of drinking or smoking problems; (4) overall respondent satisfaction with or high evaluation of their parental relationships; and (5) parent–child relationships characterized by participants’ report of their parent/s’ cared for their upbringing, receipt of extensive parental attention, and life-coaching guidance. Each construct was binary, with 1 indicating high-quality family protection.

Additionally, a summated index (ranging from 0 to 5) (FMIDX) and its standardized version (Z-FMIDX) were constructed from these five binary family factors to capture the multidimensionality of the childhood family environment. A 3-level categorical version of FMIDX was also created, with 1 indicating low levels of family protection (i.e., FMIDX = 1–2), 2 meaning medium levels of family protection (i.e., FMIDX = 3–4), and 3 indicating high levels of protection (i.e., FMIDX = 5–6).

2.5. Gene–Environment Compound Measures

Five gene–environment (G&E) compound measures were constructed by combining the binary version of each family environmental factor and binary PGS. For the PGS, we standardized scores and then coded individuals into two groups. A value of 1 indicated low polygenic depression risk (i.e., a potential plasticity factor) if the PGS fell within the lowest 40th percentile of the distribution. We chose this cut-off to match those used for family relationship and parental support measures, which made the genetic and environmental indicators more comparable. To test robustness, we also conducted sensitivity analyses using an alternative cut-off at the 50th percentile for the binary PGS measure. Results were similar.

Each G&E compound measure had four categories:

- High G Risk–High E Risk (Lowest-Level Protection): high genetic risk combined with low family protection (e.g., unstable family structure, abusive parenting, parental substance use, poor family relationships, or low parental support).

- High G Risk–Low E Risk (Medium-Level I Protection): high genetic risk combined with high family protection (e.g., stable family structure, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive family relationships, or high parental support).

- Low G Risk–High E Risk (Medium-Level II Protection): low genetic risk combined with low family protection.

- Low G Risk–Low E Risk (Highest-Level Protection): low genetic risk combined with high family protection.

2.6. Covariates

The covariates (details in Supplementary Table S9) in the multivariate analysis included socioeconomic factors of the family and schooling, such as parental education, childhood family financial stability, repeating a grade, and adult educational level, along with childhood general health status, and birth cohort variables [15,47,86,87,88].

2.7. Statistical Analyses

We estimated mixed-effects models on age-based standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) longitudinal trajectories, correcting standard errors for correlations within the respondent across time points [89,90]. Age was centered at 0, indicating the starting point of the Z-CESD growth curves in HRS at age 51 years. To capture nonlinear changes in growth curves of depression Z-CESD scores of 14 waves, quadratic age was included in the models [16]. Age and its quadratic form were continuous variables. To increase robustness, small age groups were combined: ages 51–52, 84–85, and 87–90 were collapsed into single groups to enlarge cell sizes. After centering and collapsing, age ranged from 0 to 33.

The longitudinal mixed models additionally estimated random intercepts and slope for linear age, since both intercepts and growth rates varied across individuals. Using centered age in both linear and quadratic forms to assess depression trajectories has the advantage of leveraging an accelerated longitudinal design. This provides a cost-effective way to approximate depression development in cohort studies [91,92,93].

Sequential steps were executed to estimate the mixed models. First, unconditional Z-CESD models by age, gender, and their interaction terms were estimated, applying a similar model specification in our recent studies [16]. Second, we added standardized polygenic scores for depression (Z-PGS), along with family environment measures: the family environment index (FMIDX), its standardized version (Z-FMIDX), and categorical familial measured (low, medium, and high with cut-offs derived from FMIMX). These were paired to test their additive associations with depression (Z-CESD). Third, we introduced each of the compound four-category gene–environment (G&E) measures, constructed from PGS and family environment indicators, as the main predictors. Wald tests were conducted to examine differences in estimated Z-CESD across the four G&E categories. We then added interaction terms between age variables and each G&E measure, as well as the three family environment index measures.

Model fit was evaluated using Wald tests and fit statistics (AIC and BIC). Non-significant interaction terms were excluded from the final models. We also tested gender interactions with the compound G&E measures, but dropped them because they were not statistically significant. Multivariate models controlled for covariates [15,47,86,87,88].

To aid interpretation, we estimated predicted age-specific Z-CESD depression trajectories by (1) compound 4-category gene–environment (G&E) measures, (2) the 3-category nominal variable recoded from the family environment index (FMIDX), and (3) combinations of standardized PGS (Z-PGS) and standardized family environment index (Z-FMIDX). Only selected results are shown in the main text due to design complexity; additional tables, figures, and results are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

For sensitivity analyses, we evaluated the potential impact of mortality selection on the HRS genetic database. Following an approach used by Liu and Guo (2015) [94], we compared the distribution of PGS across birth cohorts and, furthermore, the distribution of PGS between males and females. No significant differences were found across the groups. This suggests that mortality selection did not pose a serious threat to the study results, consistent with previous findings that mortality selection did not change the main results concerning BMI [94] and other outcomes such as height, education, or smoke [95].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

HRS participants experienced high levels of early family protection (Table 1). Specifically, 90.6% were raised in stable families with married parents, 93.2% were not exposed to non-abusive parenting, 83.2% grew up in substance-free parenting, 37.5% experienced positive parent–child relationships, and 41.3% received high parental support. While these findings highlight the overall protective nature of the early family environment in HRS, the relatively high prevalence of protective conditions also means that fewer participants were exposed to high-risk environments. This asymmetric distribution may limit the variability in the environmental measures of the HRS study. Thus, the effects of high-risk family conditions should be interpreted with caution.

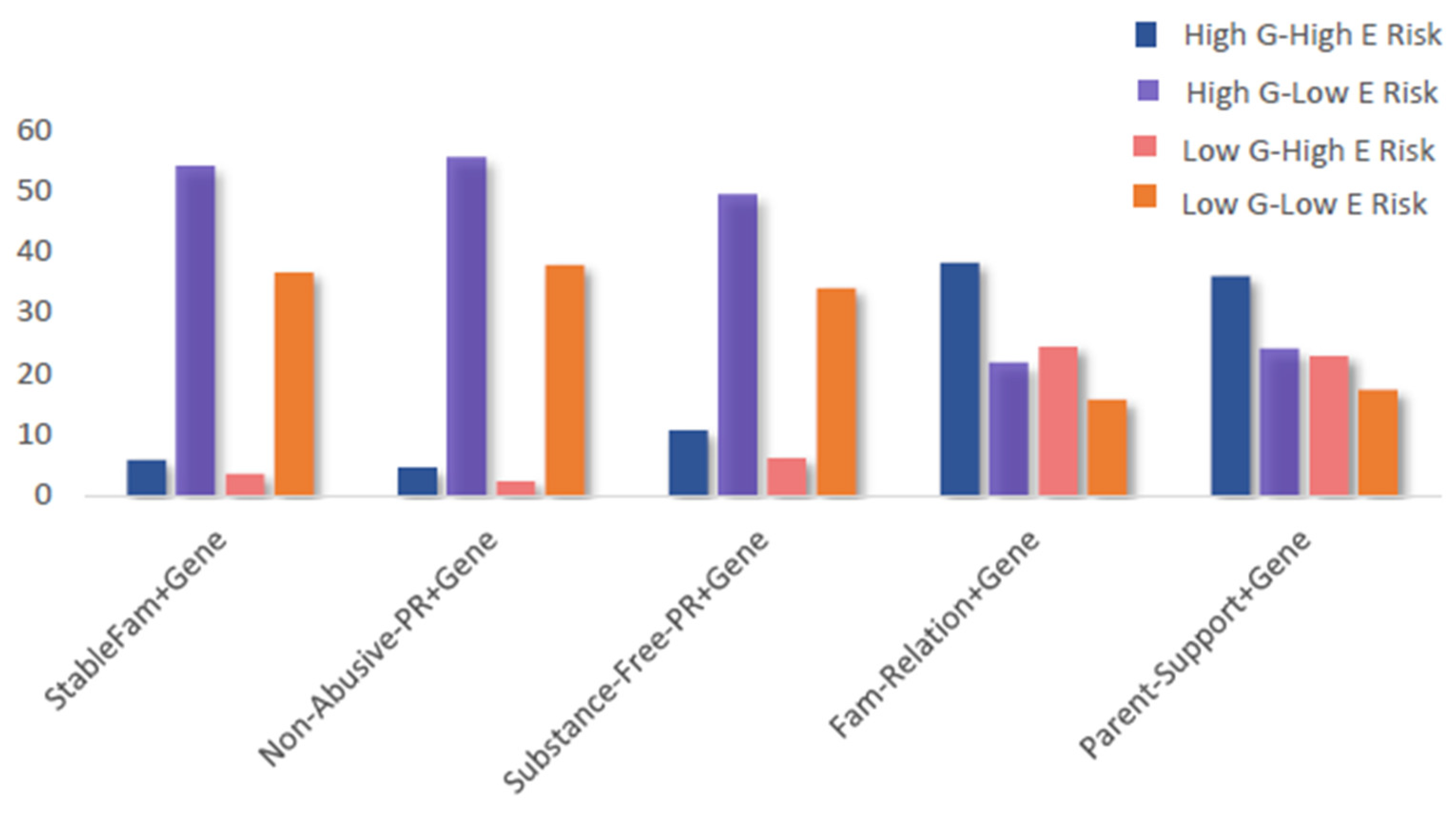

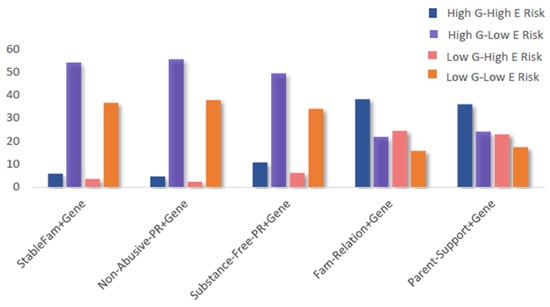

Patterns of exposure to combined gene–environment risks are shown in Figure 2, with full category distributions provided in Supplementary Table S1. For the stable-family–gene, non-abusive-parenting–gene, and substance-free-parenting–gene composites, most individuals fell into the high G–low E category. In contrast, for the family-relationships–gene and parental-support–gene composites, the largest proportion of individuals were in the high G–high E category, while the low G–low E category represented the smallest share. These distributions highlight that patterns of risk exposure varied by family environment domain, with some composites showing greater clustering in high-risk categories than others.

Figure 2.

Percentage distributions by 4 categories of the five composite gene–environment measures. Report of the statistical results is shown in Table 1. Abbreviations: G: genetic; E: environmental.

Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Table S1, the coefficients for age (β = −0.021) and squared age (β = 0.00075) are significant at the 0.001 level (Model 1). This indicates that the growth curves of depressive symptoms (measured by the standardized CES-D scale) followed a curvilinear trajectory with age. Specifically, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1, levels of depressive symptoms were relatively high at age 51, declined around age 65, and then steadily increased from age 66 to 90, peaking between ages 80 and 90.

3.2. Additive G&E Exposure and CES-D Trajectories

Each pairing of a family factor and polygenic score (PGS) showed a significant association with the Z-CESD depression score in the additive model, indicating a robust association with depression trajectories. Specifically, higher standardized PGS values were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, with each one-standard-deviation increase in PGS corresponding to an approximate 0.07-unit increase in Z-CESD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mixed growth curve models of standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) on each paired PGS and childhood family-factor measure across ages 51–90 years (N = 4817).

All protective family factors were significantly associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, even after adjusting for covariates (Table 2). Individuals who experienced stable family structures, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive family relationships, or high parental support during childhood reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those who experienced adverse conditions such as caregiver abuse, parental substance use, or poor relationships and support.

Among these, non-abusive parenting (−0.26 [95% CI, −0.34 to −0.18] in Model 2.1), positive family relationships (−0.12 [95% CI, −0.16 to −0.083] in Model 4.1), and high parental support (−0.14 [95% CI, −0.18 to −0.10] in Model 5.1) appeared to have stronger protective association with depressive symptoms compared to stable family structure (−0.045 [95% CI, −0.11 to 0.023] in Model 1.1) and substance-free parenting (−0.098 [95% CI, −0.15 to −0.045] in Model 3.1).

3.3. Compound G&E Exposure and CES-D Trajectories

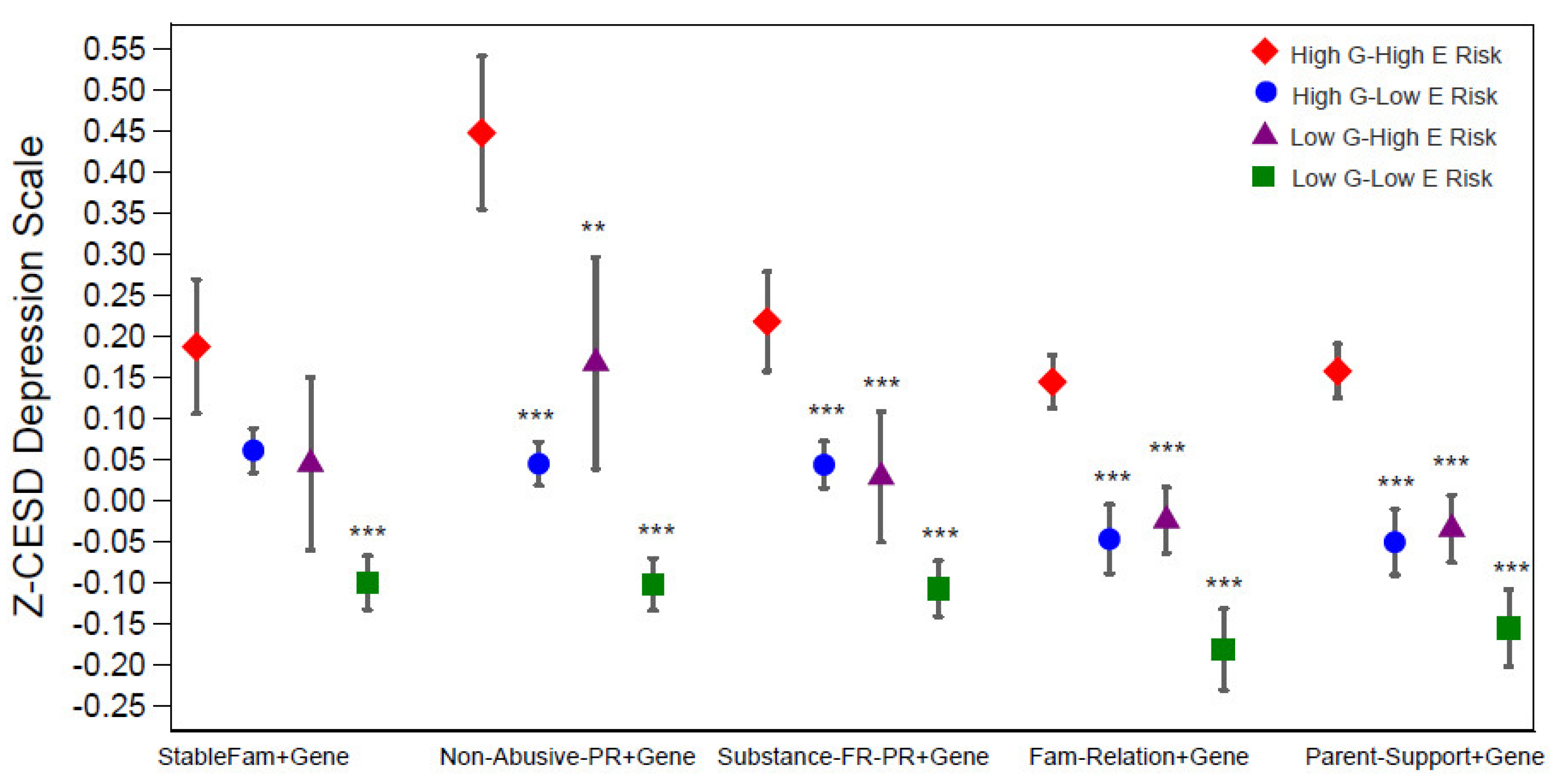

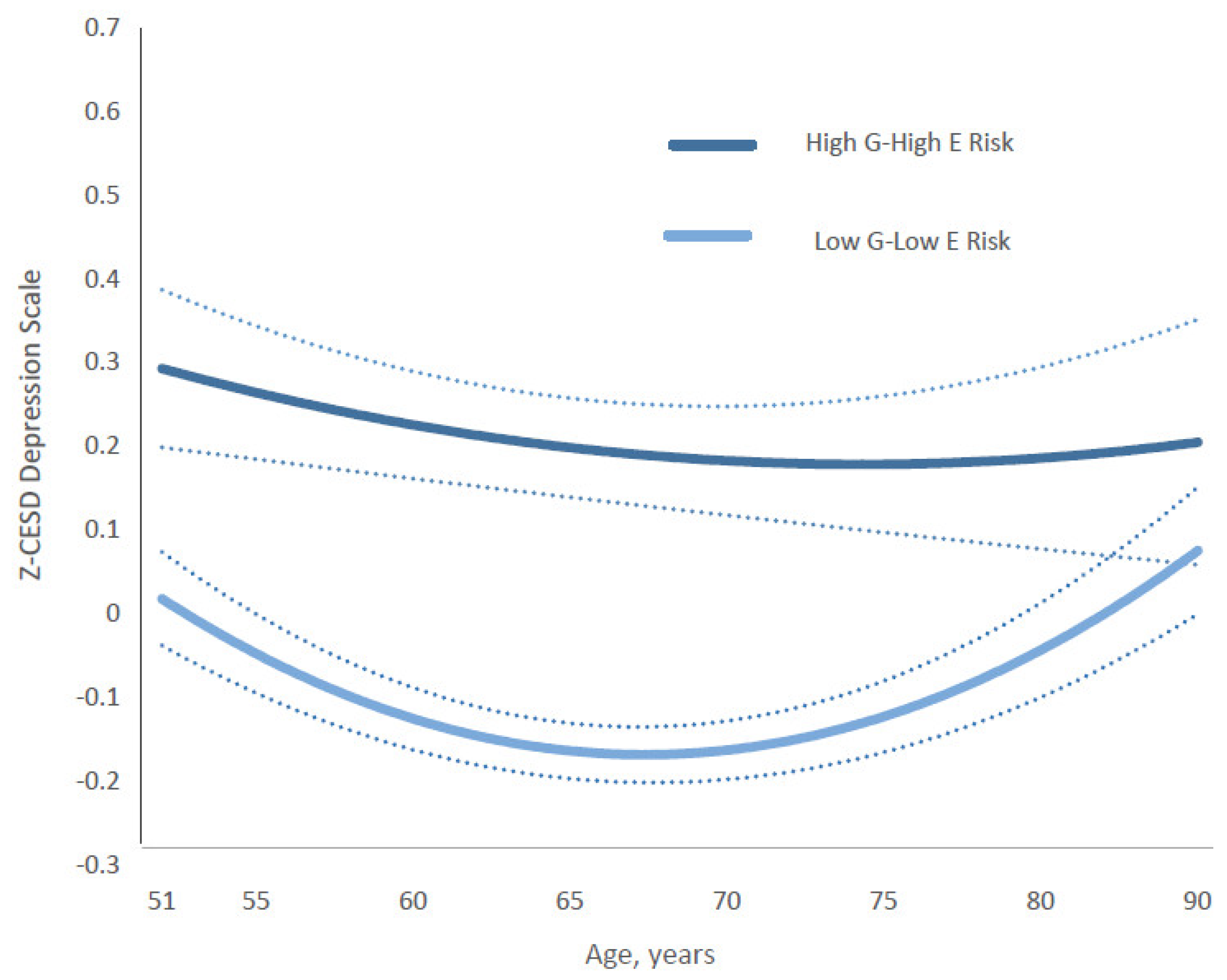

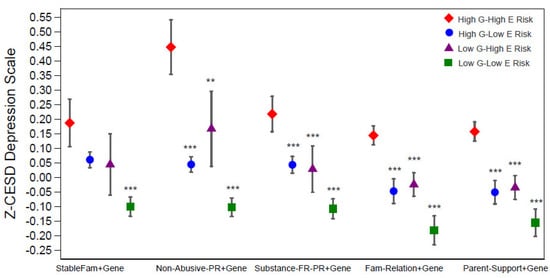

Changes in Z-CESD depression scores were significantly associated with the combined effects of genetic risk and family environment, as captured by binary PGS and each family factor—specifically, stable family with married parents, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive family relationships, and high parental support (Table 2). As shown by the coefficients for the composite gene–environment measures in Figure 3 and Models 1.2, 2.2, 3.2, 4.2, and 5.2 of Table 2, the largest differences in depressive symptoms were consistently observed between individuals in the most protective category (low G–low E) and those in the highest-risk category (high G–high E).

Figure 3.

Predicated standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) depression scores by four levels of each gene-family-factor composite measure. They were estimated from results in Supplementary Table S2 for each level of the composite measures. Significance levels are shown for the coefficients of the 3 categories (i.e., high G–low E risk, low G–high E risk, low G–low E risk) compared to the reference category of high G–high E risk (Table 1). *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Abbreviations: G = genetic; E = environmental; StableFm = stable family; Non-Abuse-PR = non-abuse parenting; Substance-FR-PR = substance-free parenting.

Effect sizes varied across composites. The strongest buffering effect was observed for non-abusive parenting, where low G–low E individuals had depression scores about 0.43 points lower than their high-risk counterparts (Model 2.2). Protective effects were also evident for stable family structure (–0.17, Model 1.2), substance-free parenting (–0.24, Model 4.2), positive family relationships (–0.24, Model 4.2), and high parental support (–0.26, Model 5.2), with full coefficients and confidence intervals reported in Table 2.

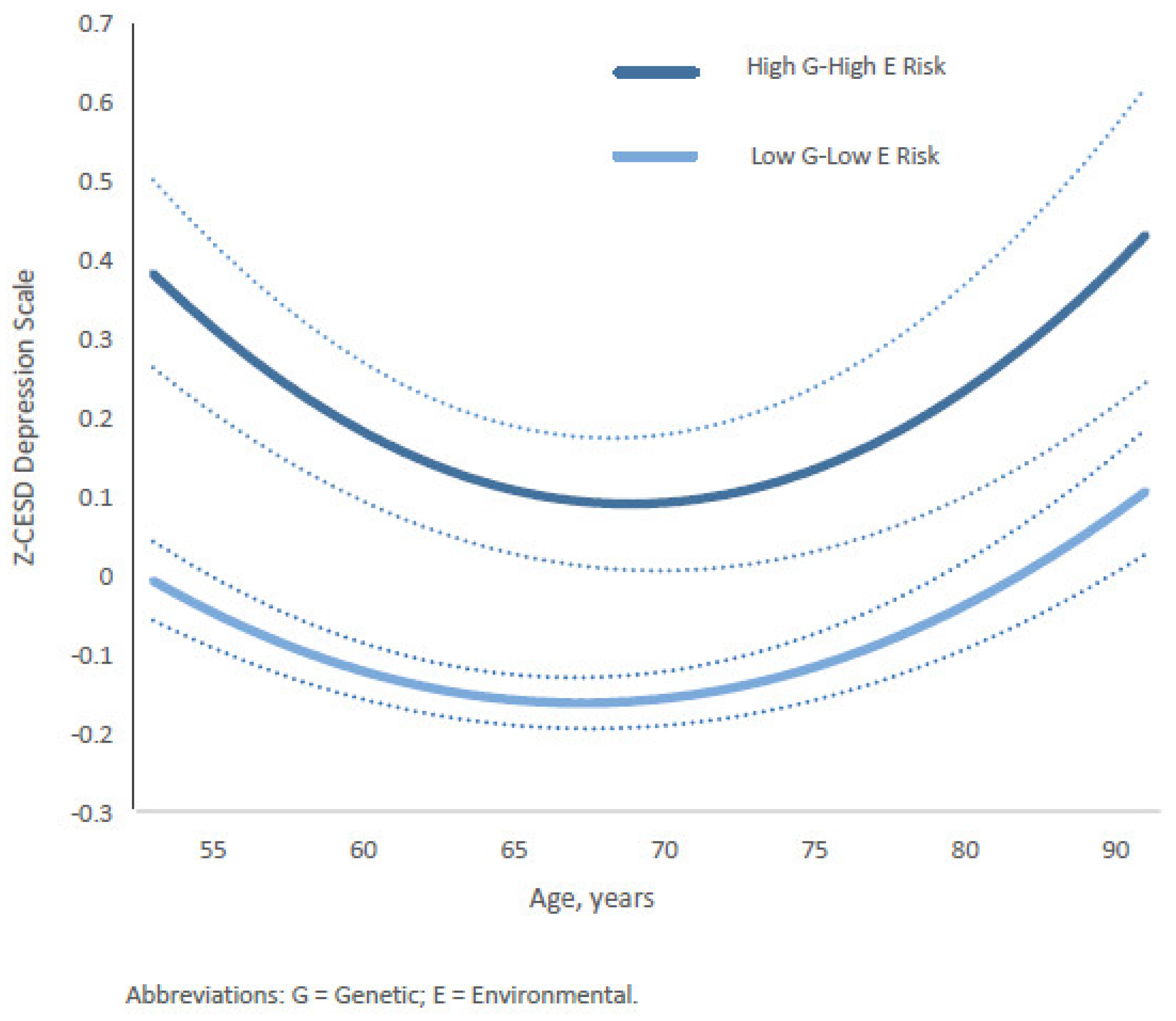

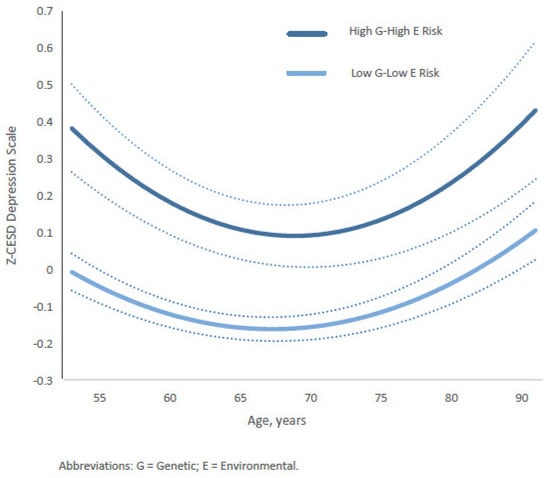

Furthermore, the relationship between depression trajectories (Z-CESD scores) and two 4-category composite gene–environment (G&E) measures—gene–stable family and gene–substance-free parenting—varied by age from middle to late adulthood. For the gene–stable family composite, the differences between the most protective group (low genetic risk and stable family) and the highest-risk group (high genetic risk and unstable family) followed a U-shaped pattern across age (Figure 4). The widest gap occurred between ages 51 and 55, gradually narrowing to its smallest point between ages 64 and 75. Subsequently, the estimated gap gradually widened again after age 75, returning to levels similar to those observed in the early fifties and continuing until age 90. Full coefficients and estimates for all categories are presented in Supplementary Table S3 (Model 1) and Table S4.

Figure 4.

Age-specific growth curves of the predicted standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) depressive symptom scores by two conditions in high G–high E risk versus low G–low E risk of the Gene-Stable-Family composite measure. Confidence intervals are shown in dotted lines. The full statistical results are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

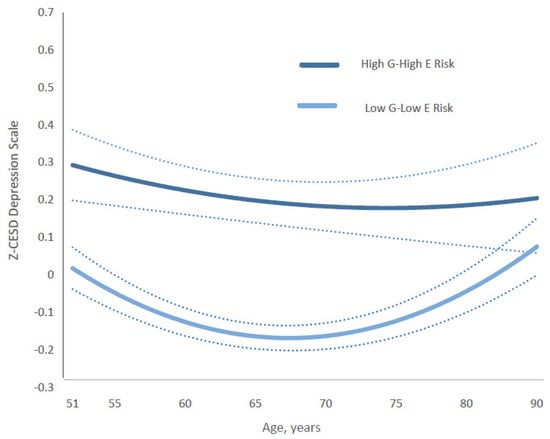

In contrast, the trajectory for the gene–substance-free parenting composite showed a different pattern (Figure 5). The gap in depression scores between the most protective group (low genetic risk and substance-free parenting) and the highest-risk group (high genetic risk and substance-use parenting) was already substantial in early midlife (ages 51–55). It widened further, peaking around ages 64–70, before gradually narrowing in later adulthood. By age 82, the gap had returned to levels (absolute value of 0.17, s.d., 0.0671) similar to those observed in the early fifties, and further decreased to approximately 0.14 in absolute value (s.d., 0.078) by ages 84–90. Full coefficients and estimates for all categories are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 (Model 2) and S4.

Figure 5.

Age-specific growth curves of the predicted standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) depressive symptom scores by two conditions in high G–high E risk versus low G–low E risk of the Gene-Substance-Free-Parenting composite measure. Confidence intervals are shown in dotted lines The full statistical results are shown in the Supplementary Table S4. Abbreviations: G = genetic; E = environmental.

In comparison, the protective effects of low genetic risk combined with supportive environments—such as non-abusive parenting, positive family relationships, and high parental support—remained relatively stable across ages 51 to 90 (Supplementary Table S4). Across all composites, these low-risk conditions were consistently associated with fewer depressive symptoms than their high-risk counterparts (high genetic risk combined with adverse family environments) (Models 1.2, 2.2, 3.2, 4.2, and 5.2 in Table 2). Among them, the combination of low genetic risk and non-abusive parenting showed the strongest buffering effect (coefficient = 0.43, [95% CI: −0.53, −0.33] in Model 2.2, Table 2) throughout middle and late adulthood.

3.4. Genetics, Multidimensional Protective Family Environment, and CES-D Trajectories

Individuals who reported positive experiences in one domain had higher percentages of positive family experiences in other domains (Supplementary Table S5). For example, compared to those who received low parental support during childhood, a significantly higher percentage of individuals who received high parental support also experienced positive parent–child relationships, free of parental abuse and substance use, and resided with married parents.

The result for the family environment index (FMIDX), reflecting the intercorrelation and multidimensionality of early environmental exposure, demonstrated the collective role of family factors in mitigating the standardized CES-D (Z-CESD) depression trajectories (Table 3). Exposure to increasing numbers of childhood protective factors was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms. Individuals experienced a decrease of roughly 0.40 (when 5 multiplied the absolute value of β = −0.078 [95% CI: −0.096, −0.060] in Model 1, Table 3) in the depressive symptom Z-CESD score when FMIDX increased from 0 to 5.

Table 3.

Mixed growth curve models of standardized CES-D on PGS and childhood family environment index (FMIDX) across ages 51–90 years (N = 4817).

We used both raw and standardized versions of the family environment index (FMIDX). The raw FMIDX reflects a simple count of protective family factors (range: 0–5), which facilitates interpretation in terms of the number of protective conditions experienced. In contrast, the standardized FMIDX (Z-FMIDX) rescales this index to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1, allowing direct comparison of effect sizes with standardized polygenic scores (Z-PGS) in regression models. While raw scores are useful for conveying the practical magnitude of family protection (e.g., moving from 0 to 5 protective factors), standardized scores enable effect sizes to be interpreted on a comparable scale across predictors. We indicate in all tables and figures whether raw or standardized values are used to minimize confusion.

When the coefficients of standardized FMIDX (Z-FMIDX: −0.089 [95% CI, −0.11 to −0.069]) and PGS (0.072 [95% CI, 0.052 to 0.091] in Model 2, Table 3) were compared, the absolute effect of Z-FMIDX was 0.017 larger than that of Z-PGS for a one-standard-deviation increase in both measures simultaneously. Although these coefficients appear modest in magnitude, even small shifts in standardized depression scores can provide practical implications when accumulated across multiple standard deviation changes. For example, an individual three standard deviations above the mean on Z-FMIDX may experience 0.27 lower standardized depressive symptom scores, whereas an individual three standard deviations below the mean on Z-PGS may experience 0.054 lower scores. In this case, protective family environments may exert slightly greater effects than polygenic risk—underscoring their potential clinical and public health relevance as modifiable targets for early-life intervention.

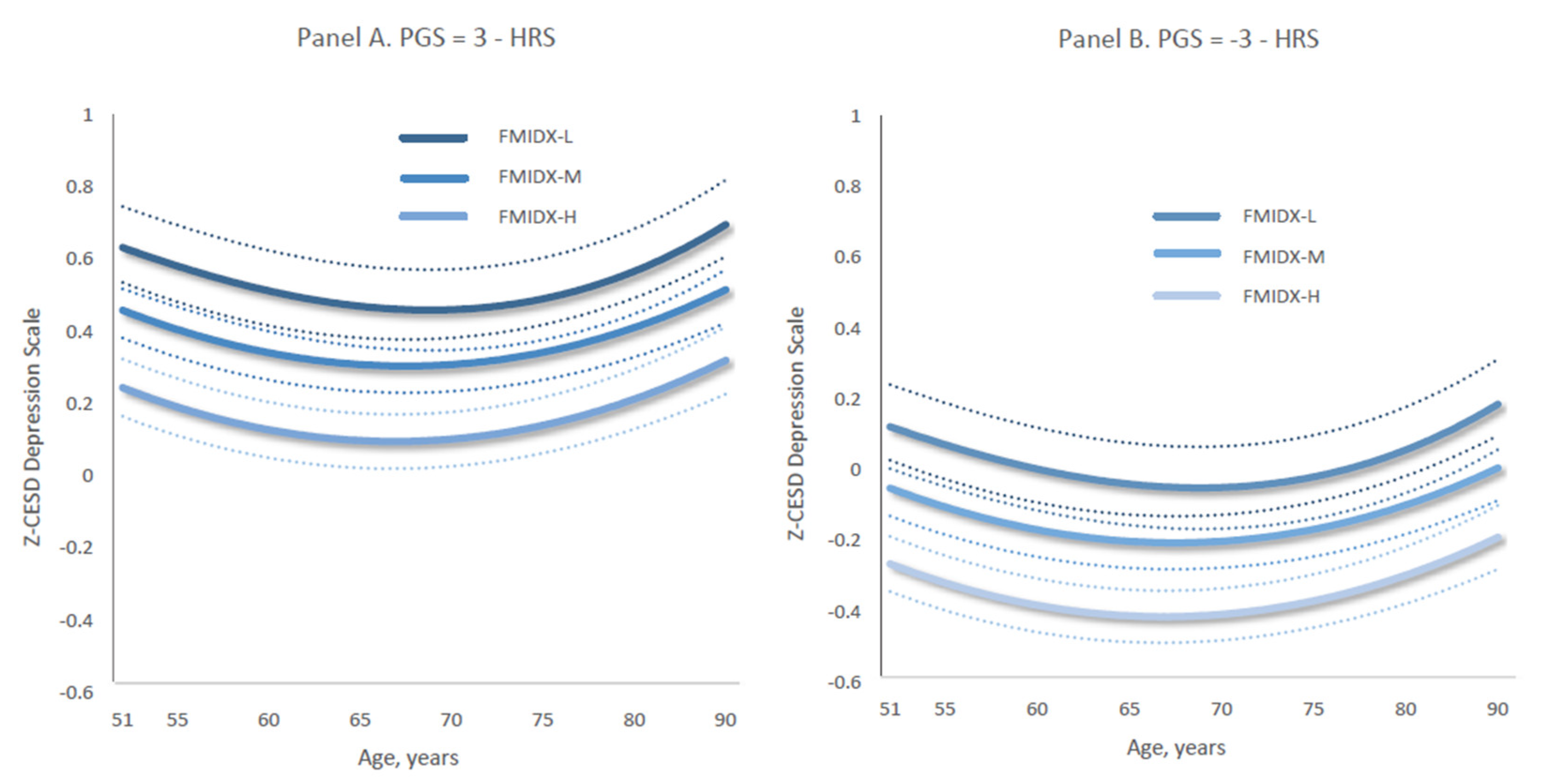

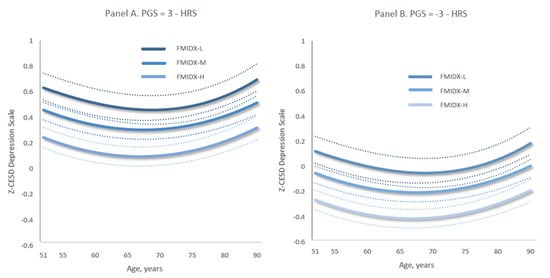

Furthermore, individuals who were exposed to low levels of family protection had persistently higher levels of depressive symptoms into late adulthood (e.g., Figure 6a,b). The Z-CESD depression trajectories by three levels of the protective family environment index (FMIDX) shifted downward in parallel, equally decreasing when the values of Z-PGS decreased from 3 to −3. Specifically, Figure 6a,b together indicate that the age-specific growth curves of depression scores across three levels of FMIDX—from FMIDX-Low to FMIDX-High—decreased by 0.43 as polygenic scores declined from 3 to −3. This estimate is based on multiplying 6 by the Z-PGS coefficient of 0.073 in Model 3 (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Age-specific growth curves of predicted standardized CES-D scores of depressive symptoms (Z-CESD) by the three-category family protection measure when PGS = 3 (Panel A) versus PGS = −3 (Panel B). Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Each panel shows results for a different level of the categorical three-level family environment measure (derived from the raw family index—FMIDX): FMIDX-L = low family protection, FMIDX-M = medium family protection, and FMIDX-H = high family protection. (A) presents trajectories for individuals with a polygenic score (PGS) of 3, while (B) presents trajectories for those with a PGS of −3. Predicted trajectories were estimated using Model 3, as reported in Supplementary Table S6.

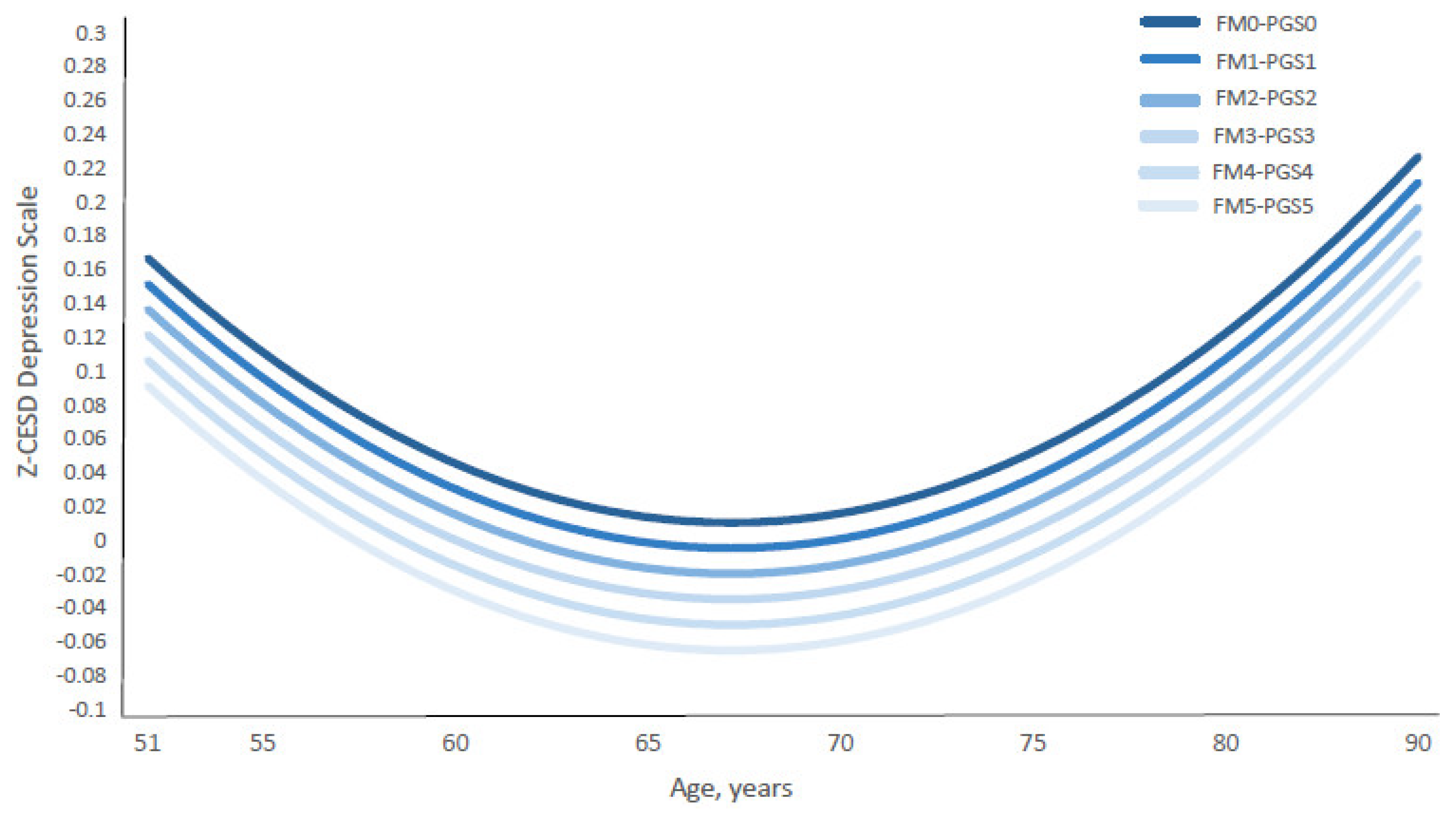

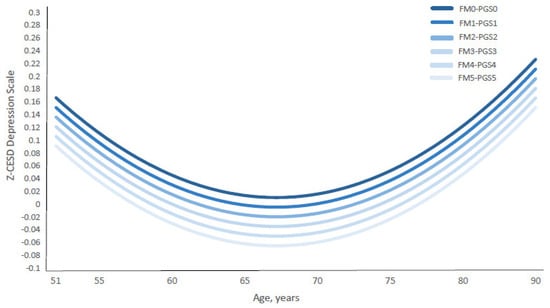

Notably, the depression curve shifted downward in parallel with the combined increase in the standardized family environment index (Z-FMIDX) and polygenic scores (Z-PGS) (Figure 7 and Supplementary Table S7). The figure illustrates that the gaps between depression score trajectories—comparing conditions of high family protection and high genetic risk (i.e., the FM5-PGS5 curve, where Z-FMIDX and Z-PGS = 1.3531) versus low family protection and low genetic risk (i.e., the FM0-PGS0 curve, where Z-FMIDX and Z-PGS = −3.0354)—remained consistent across ages 51 to 90.

Figure 7.

Age-Specific Standardized CES-D Depression Scores by Coupled Standardized Family Factor Index and PGS. Abbreviations: FM = Standardized Family Index; PGS = standardized polygenic score. Notes: Figure 7 presents the growth curves of predicted age-specific standardized CES-D scores of depressive symptoms (Z-CESD) by paired equivalent values of standardized family environment index (Z-FMIDX) and standardized PGS (Z-PGS). The predicted Z-CESD curves were estimated from Model 2, shown in Supplementary Table S6. The age-specific predicted Z-CESD scores by each pair of Z-FMIDX and Z-PGS are shown in Supplementary Table S7. FM0–PGS0 to FM5–PGS5 represent matched standardized values of FMIDX and PGS (Z-scores). The corresponding standardized values are: −3.0354 (FMIDX = 0), −2.1577 (FMIDX = 1), −1.2800 (FMIDX = 2), −0.4023 (FMIDX = 3), 0.4754 (FMIDX = 4), and 1.3531 (FMIDX = 5). Corresponding Z–FMIDX versus FMIDX values are shown in Table 1.

Importantly, the FM5-PGS5 curve shows the lowest depression scores, while the FM0-PGS0 curve presents the highest depression scores. In other words, individuals with high early family protection (FM5) and high genetic risk (PGS5) experienced substantially lower levels of depressive symptoms than those with low genetic risk (PGS0) but who were exposed to adverse family environments (FM0). This pattern suggests that high early family protection (FM5) provides a stronger buffer against depressive symptoms than low genetic risk alone. In practical terms, this means that even among individuals with elevated genetic liability, protective family environments during childhood may confer meaningful reductions in depressive symptoms decades later.

4. Discussion

Wide gaps remain in prior research applying the life course perspective to elucidate how gene–environment mechanisms influence lifetime health development. This study, to our knowledge, was the first to investigate how polygenic predisposition and early protective family environment jointly shape mental health trajectories from mid- to late life in a national European ancestry cohort.

Our findings advance understanding of the complex mechanism in which nature and nurture jointly shape depression risk over time. Specifically, they provide new evidence on the additive and compound associations between genetics and environment in shaping depression across the life course. Different combinations of genetic vulnerability and early family environments may set individuals on divergent health pathways, which become increasingly difficult to alter in later life, with consequences for morbidity, mortality, and overall well-being throughout the aging process.

4.1. Key Findings: Gene–Environment Mechanisms

First, this study provides new evidence that both genetic and environmental factors are essential and act together to shape depression trajectories across the life course. Based on genome-wide information, the continuum of PGS reflects divergent pathways, with the lower end potentially indicating genetic plasticity as a buffering factor [96].

Moreover, prior research has often relied on a restricted spectrum of familial risk factors [97]. In contrast, our study broadened the scope by incorporating a rich plethora of protective family characteristics, offering an extensive depiction of early promotive environments. Future work should continue to expand protective measures using frameworks of resilience, plasticity, and malleability [97]. Such approaches can capture home conditions that range from general family stability and absence of risk to enriched nourishment. Highly correlated measures of risk-free and promotive factors can collectively describe the multidimensional nature of family environments. For example, a stable family structure may support healthy parenting behaviors, while protective caregivers can purposefully avoid harmful behaviors toward their children.

Particularly, coupled with low genetic susceptibility, multiple protective environmental factors—such as stability of the family structure, risk-free non-abusive and substance-free parenting, nourishing family relationships, and high parental support reflected by high-quality care, warmth, and satisfactory parent–child communications—can improve lifelong mental health. These conditions may work independently but also collectively to mitigate depression trajectories from mid- to late adulthood. Collectively, they may reduce the standardized CES-D depression trajectory up to 0.40 points in this HRS study. While genetic predisposition may exert a constant influence across the lifespan, its combined force with family factors likely alters the shapes of the trajectories over time. For example, our findings suggest that a stable family structure, positive family relationships, high parental support, substance-free parenting, and non-abusive parenting—coupled with low genetic susceptibility—together may play a significant role in buffering against excessive stress, thereby reducing the HRS cohort’s standardized depression scores by up to 0.43 points in middle to late adulthood. Additionally, the conditions of low-gene–non-abusive parenting persistently play a robust, bigger role in mitigating depressive conditions than other combined positive G-E conditions during the middle-to-late adulthood period.

Second, family environment might play a more significant role than genetic factors in influencing mental health development. Comparison of the magnitude of G versus E effects indicates that multifaceted family factors likely exert larger impacts on mental well-being than polygenic predisposition. Importantly, children raised in protective family environments (low E risk) often fare better psychologically over time—even when they carry a high genetic risk for depression (high G risk). In contrast, children growing up in dysfunctional environments (high E risk) may experience worse outcomes, even if their genetic vulnerability is relatively low (low G risk). For example, individuals who have experienced a high level of family protection despite high genetic depression risk tend to have a lower standardized depression score by roughly 0.07 points, compared to those with low-level family protection despite low genetic risk (Supplementary Table S7).

Third, the childhood period may be particularly responsive to a positive environment, which can prevent or buffer against depression risk across time [48]. This effect is evident among people with high genetic vulnerability. Children need appropriate parental and familial support to develop coping strategies, self-esteem, attachment, and appraisal skills, as well as instrumental support for lifelong healthy development [40,41,98,99]. Supportive family environments may promote brain structuring and physiological and neuroendocrine system regulation, helping youth to develop lifetime stress-coping abilities [45,46,100,101,102,103,104,105].

Protective early-life exposure may impact DNA methylation and histone modifications, which, in turn, may alter gene expression and behavior [106,107,108]. Resilience capabilities cultivated at a young age may continue to foster better mental health into adulthood, helping individuals combat midlife crisis and excessive stresses of aging from cognitive, physical, and psychosocial decline [42]. Overall, resilience cultivated early through protective family environments appears to yield lifelong benefits for mental well-being, overall health, and longevity [15,47]. Greater lifelong psychological resilience is likely linked to lower rates of chronic illness, reduced risk of premature death from despair, and decreased all-cause and cause-specific mortality in aging populations [109,110].

Findings highlight the importance of incorporating multiple approaches in gene–environment research on longitudinal mental health. Prior studies often placed disproportionate emphasis on gene–environment interactions, even though evidence has been mixed and often non-significant [111]. Alternatively, more scientific endeavors can instead focus more on how genes and environments work together through additive or compound mechanisms to shape long-term health outcomes. Environments are complex, comprised of multifaceted interrelated factors. These factors may act through different mechanisms, especially when combined with genetic predisposition.

4.2. Implications for Research and Policy

This study provides significant implications for public health and social policies. Mental health professionals may utilize the knowledge to design personalized plans for early prevention and intervention [97]. Health initiatives can shift the focal attention from reducing familial risk alone to also fostering parenting skills that build protective family environments. It is important to assess family functioning not only among genetically vulnerable youth but also among those with low genetic risk. Even children with low genetic vulnerability may face lifelong risks of depression if they grow up in negative family dynamics. Supportive programs should therefore encourage and educate parents to build positive relationships with their children and to provide both emotional and instrumental support. Special attention is needed for families with genetically at-risk children, where unfavorable gene–environment combinations may compound vulnerability. Early cultivation of positive family environments can have long-lasting benefits. Such interventions may reduce depressive symptoms well into middle and late adulthood, even among those with high genetic risk. This is particularly critical because depression risk tends to rise sharply in midlife, driven by mounting pressures from work, family, and social life, and again in old age, when physical and cognitive challenges accumulate [7,112].

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study contributes comprehensive novel evidence about gene–environment coupling mechanisms and life course depression trajectories, some limitations and future research directions are discussed. First, depressive symptoms were measured using the widely adopted CES-D scales. These epidemiological measures may best reflect the “healthy” national population of European origin, rather than individuals diagnosed in clinical settings. Future research can incorporate validated psychiatric assessments across different cohorts to test whether findings hold for both general populations and clinical patients.

Second, current GWAS of depression sampled participants of European ancestry. Future research can direct attention to conducting large-scale GWAS in populations of other ancestries to investigate gene–environment associations in more diverse contexts. Continued efforts to expand GWAS in more diverse populations will be essential for improving the broader applicability of polygenic-related studies.

Third, child familial data were based on retrospective reports. As such, the measurement could be subject to recall bias. However, previous evidence suggests that retrospective reports can be reliable, as older adults often remember salient childhood events and experiences [113,114].

Fourth, as descriptive results show relatively high levels of some family protection factors (e.g., >90% in stable family structure), this distribution asymmetry may limit the variability in interpreting effects under high-risk environmental conditions, such as unstable family, abusive parenting, and substance-use parenting. Future studies could extend this work by using other national cohorts to verify our findings. Fifth, future research can build on this groundwork to examine the complex processes of how genetics, early familial exposure, and stress occurring in adulthood periods interplay to shape mental health development. One direction is to investigate how current adulthood stress and its interactions with genetic and childhood environmental factors contribute to long-term patterns of depression outcomes.

Lastly, conceptually, depression has been widely studied in life course research and is strongly linked to genetic predisposition, family environments, and long-term health outcomes, making it a suitable starting point for examining gene–environment processes across the life course. Methodologically, the CES-D has been consistently assessed across 14 waves in the HRS, providing a reliable longitudinal measure of depressive symptoms that is not available for other mental health disorders (like anxiety) in the dataset. Our findings lay a strong foundation for future research to extend this framework to other conditions, such as anxiety. Anxiety disorders may have higher base rates and overlapping etiological pathways with depression. Future work could further investigate the pathways through which comorbid anxiety and depression are shaped by genetics and early protective environments with other available national longitudinal data.

5. Conclusions

Findings reveal that the link between genetics, early family environment, and mental health trajectories from middle to late adulthood is complex. Genetic predisposition and childhood family environments are interconnected to work together as combined antecedents that shape diverging mental health pathways across the life course. Individuals with low genetic plasticity and strong environmental protection benefit most psychologically during middle and late adulthood. When only one favorable factor is present, high environmental protection tends to improve mental health more than low genetic risk alone.

Early interventions that protect young children may strengthen lifelong mental health pathways and development. Those with high genetic risk are especially likely to benefit. Such interventions can also promote better overall health across the lifespan, help prevent or delay chronic diseases, and reduce mortality rates in aging populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/populations1040022/s1, Figure S1: Unconditional Z–CESD Curves-HRS, Tables S1: Growth–Curve Mixed Models on Continuous PGS and Family Factors, Table S2: Growth–Curve Mixed Models on 4–Category Gene–Family–Factor Measures, Table S3: Growth–Curve Mixed Models on 4–Category Gene–Family–Factor Measures and Age Variables, Table S4: Predicted Z–CESD with Standard Error in Paratheses by High–vs.–Low Gene–Family–Risk Conditions and Z–CESD Difference, Table S5: Row Percentages of Crosstabulations between Each Paired Childhood Family Protective Factor. Table S6: Growth–Curve Mixed Models on Z–PGS and Family Environment Index Measures, Table S7: Predicted Z–CESD Depression Scores by standardized Family Environment Index (Z–FMIDX) and PGS, Table S8: Description of Five Childhood Family Protective Factors, Table S9: Covariates Measurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.; Methodology, P.C. and Y.L.; Formal analysis, P.C. and Y.L.; Investigation, P.C.; Data curation, P.C. and Y.L.; Writing—original draft, P.C. and Y.L.; Visualization, P.C.; Supervision, P.C.; Project administration, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this work uses secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required because this work uses secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data.

Data Availability Statement

The original data used in the study come from the Health Retirement Study (HRS) and are publicly available. Details about data access and user agreements are provided on the HRS website: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Depression. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Bromet, E.; Andrade, L.H.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Alonso, J.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Hu, C.; Iwata, N.; et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustün, T.B.; Rehm, J.; Chatterji, S.; Saxena, S.; Trotter, R.; Room, R.; Bickenbach, J. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group. Lancet 1999, 354, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, W.E.; Blazer, D.G.; George, L.K.; Tse, C.K. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990, 264, 2524–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; Gennuso, K.P.; Ugboaja, D.C.; Remington, P.L. The epidemic of despair among white Americans: Trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999-2015. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, R.K.; Tilstra, A.M.; Simon, D.H. Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.; Wetherell, J.L.; Gatz, M. Depression in older adults. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Goodwin, R.D.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, H.; Bjørkløf, G.H.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Helvik, A.-S. Depression and quality of life in older persons: A review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 40, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evid. Based Nurs. 2014, 17, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.A.; Reynolds-Iii, C.F. Late-life depression in the primary care setting: Challenges, collaborative care, and prevention. Maturitas 2014, 79, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaup, A.R.; Byers, A.L.; Falvey, C.; Simonsick, E.M.; Satterfield, S.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Smagula, S.F.; Rubin, S.M.; Yaffe, K. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in older adults and risk of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Harris, K.M. Association of positive family relationships with mental health trajectories from adolescence to midlife. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Zadrozny, S.; Seifer, R.; Belger, A. Polygenic risk, childhood abuse and gene x environment interactions with depression development from middle to late adulthood: A U.S. National Life-Course Study. Prev. Med. 2024, 185, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, F. The genetics of depression in childhood and adolescence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.R.; Ripke, S.; Mattheisen, M.; Trzaskowski, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Abdellaoui, A.; Adams, M.J.; Agerbo, E.; Air, T.M.; Andlauer, T.M.F.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, S.R.; Price, T.S. The implications of genotype-environment correlation for establishing causal processes in psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, F. Genetics of childhood and adolescent depression: Insights into etiological heterogeneity and challenges for future genomic research. Genome Med. 2010, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussier, A.A.; Hawrilenko, M.; Wang, M.-J.; Choi, K.W.; Cerutti, J.; Zhu, Y.; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Dunn, E.C. Genetic susceptibility for major depressive disorder associates with trajectories of depressive symptoms across childhood and adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Gatz, M.; Gardner, C.O.; Pedersen, N.L. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Ohlsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. The genetic epidemiology of treated major depression in sweden. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T.J.C.; Benyamin, B.; de Leeuw, C.A.; Sullivan, P.F.; van Bochoven, A.; Visscher, P.M.; Posthuma, D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.C.; Brown, R.C.; Dai, Y.; Rosand, J.; Nugent, N.R.; Amstadter, A.B.; Smoller, J.W. Genetic determinants of depression: Recent findings and future directions. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, C.L.; Nagle, M.W.; Tian, C.; Chen, X.; Paciga, S.A.; Wendland, J.R.; Tung, J.Y.; Hinds, D.A.; Perlis, R.H.; Winslow, A.R. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Clarke, T.-K.; Hafferty, J.D.; Gibson, J.; Shirali, M.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Ward, J.; Wigmore, E.M.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. Genes, depressive symptoms, and chronic stressors: A nationally representative longitudinal study in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 242, 112586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.R.; Logue, M.W.; Wolf, E.J.; Maniates, H.; Robinson, M.E.; Hayes, J.P.; Stone, A.; Schichman, S.; McGlinchey, R.E.; Milberg, W.P.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity is associated with reduced default mode network connectivity in individuals with elevated genetic risk for psychopathology. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.R.; Lee, S.H.; Mehta, D.; Vinkhuyzen, A.A.E.; Dudbridge, F.; Middeldorp, C.M. Research review: Polygenic methods and their application to psychiatric traits. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.M.; Sullivan, P.F.; Lewis, C.M. Uncovering the genetic architecture of major depression. Neuron 2019, 102, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, K.M.; Van Assche, E.; Andlauer, T.F.M.; Choi, K.W.; Luykx, J.J.; Schulte, E.C.; Lu, Y. The genetic basis of major depression. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2217–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, D.P.; Blustein, D.L. Contributions of family relationship factors to the identity formation process. J. Couns. Dev. 1994, 73, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J.E.; Johnson, M.K. Adolescent family context and adult identity formation. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missildine, W.H. Your Inner Child of the Past; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1963; ISBN 0671747037. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Parents and Caregivers are Essential to Children’s Healthy Development. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/parents-caregivers (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment: Attachment and Loss Volume One Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds: Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. An expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 130, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Stanton, A.L. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Stoddard, S.A.; Eisman, A.B.; Caldwell, C.H.; Aiyer, S.M.; Miller, A. Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostinar, C.E.; Gunnar, M.R. Social Support Can Buffer against Stress and Shape Brain Activity. AJOB Neurosci. 2015, 6, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Inner child of the past: Long-term protective role of childhood relationships with mothers and fathers and maternal support for mental health in middle and late adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Binder, E.B. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: Review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaves, L.J. Genotype x Environment interaction in psychopathology: Fact or artifact? Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2006, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.E.; Keller, M.C. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Berk, M.S.; Lee, S.S. Differential susceptibility in longitudinal models of gene-environment interaction for adolescent depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrot, W.J.; Milaneschi, Y.; Abdellaoui, A.; Sullivan, P.F.; Hottenga, J.J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Effect of polygenic risk scores on depression in childhood trauma. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musliner, K.L.; Seifuddin, F.; Judy, J.A.; Pirooznia, M.; Goes, F.S.; Zandi, P.P. Polygenic risk, stressful life events and depressive symptoms in older adults: A polygenic score analysis. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, N.; Power, R.A.; Fisher, H.L.; Hanscombe, K.B.; Euesden, J.; Iniesta, R.; Levinson, D.F.; Weissman, M.M.; Potash, J.B.; Shi, J.; et al. Polygenic interactions with environmental adversity in the aetiology of major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klengel, T.; Binder, E.B. Epigenetics of Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders and Gene × Environment Interactions. Neuron 2015, 86, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; McLanahan, S.; Hobcraft, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Garfinkel, I.; Notterman, D. Family Structure Instability, Genetic Sensitivity, and Child Well-Being. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 120, 1195–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, H.J.; Schwahn, C.; Appel, K.; Mahler, J.; Schulz, A.; Spitzer, C.; Fenske, K.; Barnow, S.; Lucht, M.; Freyberger, H.J.; et al. Childhood maltreatment, the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene and adult depression in the general population. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.G.; Binder, E.B.; Epstein, M.P.; Tang, Y.; Nair, H.P.; Liu, W.; Gillespie, C.F.; Berg, T.; Evces, M.; Newport, D.J.; et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: Moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G.; Caspi, A.; Williams, B.; Price, T.S.; Danese, A.; Sugden, K.; Uher, R.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Protective effect of CRHR1 gene variants on the development of adult depression following childhood maltreatment: Replication and extension. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, J.M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Paul, R.H.; Bryant, R.A.; Schofield, P.R.; Gordon, E.; Kemp, A.H.; Williams, L.M. Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Brückl, T.; Pfister, H.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H.U.; Holsboer, F.; Ising, M.; Binder, E.B.; Uhr, M.; Nocon, A. The interplay of variations in the FKBP5 gene and adverse life events in predicting the first onset of depression during a ten-year follow-up. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009, 42, A189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bet, P.M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Bochdanovits, Z.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Schoor, N.M.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G. Glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms and childhood adversity are associated with depression: New evidence for a gene-environment interaction. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009, 150B, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Brückl, T.; Nocon, A.; Pfister, H.; Binder, E.B.; Uhr, M.; Lieb, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; Holsboer, F.; et al. Interaction of FKBP5 gene variants and adverse life events in predicting depression onset: Results from a 10-year prospective community study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; López-López, J.A.; Hammerton, G.; Manley, D.; Timpson, N.J.; Leckie, G.; Pearson, R.M. Genetic and environmental risk factors associated with trajectories of depression symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrier, V.; Kwong, A.S.F.; Luo, M.; Dalvie, S.; Croft, J.; Sallis, H.M.; Baldwin, J.; Munafò, M.R.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Grant, A.J.; et al. Gene-environment correlations and causal effects of childhood maltreatment on physical and mental health: A genetically informed approach. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; Morris, T.T.; Pearson, R.M.; Timpson, N.J.; Rice, F.; Stergiakouli, E.; Tilling, K. Polygenic risk for depression, anxiety and neuroticism are associated with the severity and rate of change in depressive symptoms across adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.H. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Forrest, C.B.; Lerner, R.M.; Faustman, E.M. (Eds.) Handbook of life Course Health Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319471419. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, D.; McKeigue, P.M. Epidemiological methods for studying genes and environmental factors in complex diseases. Lancet 2001, 358, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnega, A.; Faul, J.D.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Langa, K.M.; Phillips, J.W.R.; Weir, D.R. Cohort profile: The health and retirement study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster, F.T.; Suzman, R. An overview of the health and retirement study. J. Hum. Resour. 1995, 30, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.G.; Ryan, L.H. Overview of the health and retirement study and introduction to the special issue. Work, Aging and Retire. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HRS 2020 HRS COVID-19 Project|Health and Retirement Study. Available online: https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/2020-hrs-covid-19-project (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- HRS. CIDR Health Retirement Study Imputation Report—1000 Genomes Project Reference Panel: Summary and Recommendations for dbGaP Users; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Highland, H.M.; Avery, C.L.; Duan, Q.; Li, Y.; Harris, K.M. Quality Control Analysis of Add Health GWAS Data; Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.R.; Gignoux, C.R.; Walters, R.K.; Wojcik, G.L.; Neale, B.M.; Gravel, S.; Daly, M.J.; Bustamante, C.D.; Kenny, E.E. Human Demographic History Impacts Genetic Risk Prediction across Diverse Populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Wedow, R.; Okbay, A.; Kong, E.; Maghzian, O.; Zacher, M.; Nguyen-Viet, T.A.; Bowers, P.; Sidorenko, J.; Karlsson Linnér, R.; et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson Linnér, R.; Biroli, P.; Kong, E.; Meddens, S.F.W.; Wedow, R.; Fontana, M.A.; Lebreton, M.; Tino, S.P.; Abdellaoui, A.; Hammerschlag, A.R.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, P.; Freese, J.; Sicinski, K.; Domingue, B.W.; Mullan Harris, K.; Wei, C.; Hauser, R.M. Genes, gender inequality, and educational attainment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Halpern, C.T.; Whitsel, E.A.; Hussey, J.M.; Killeya-Jones, L.A.; Tabor, J.; Dean, S.C. Cohort profile: The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health (add health). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1415-1415k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, J.; Weisz, R.; Bibi, Z.; Rehman, S. Validation of the Eight-Item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Among Older Adults. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffick, D.E. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Euesden, J.; Lewis, C.M.; O’Reilly, P.F. PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1466–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, T.; Piechaczek, C.; Soares de Matos, A.P.; Czamara, D.; Pehl, V.; Wagenbuechler, P.; Feldmann, L.; Quickenstedt-Reinhardt, P.; Allgaier, A.-K.; Freisleder, F.J.; et al. Polygenic risk: Predicting depression outcomes in clinical and epidemiological cohorts of youths. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Chen, P. The acculturation gap of parent–child relationships in immigrant families: A national study. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 1748–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H. Neighborhood safety and major depressive disorder in a national sample of black youth; gender by ethnic differences. Children 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.; Kinderman, P. The impact of financial hardship in childhood on depression and anxiety in adult life: Testing the accumulation, critical period and social mobility hypotheses. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, F.; Kang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; et al. Perceived academic stress and depression: The mediation role of mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 760387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; p. 512. ISBN 9780761919049. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-59718-103-7. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S.C.; Duncan, T.E.; Hops, H. Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, J.J.; Hamagami, F. Modeling incomplete longitudinal and cross-sectional data using latent growth structural models. Exp. Aging Res. 1992, 18, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Guo, G. Lifetime socioeconomic status, historical context, and genetic inheritance in shaping body mass in middle and late adulthood. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingue, B.W.; Belsky, D.W.; Harrati, A.; Conley, D.; Weir, D.R.; Boardman, J.D. Mortality selection in a genetic sample and implications for association studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Jonassaint, C.; Pluess, M.; Stanton, M.; Brummett, B.; Williams, R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Azhari, A.; Borelli, J.L. Gene × environment interaction in developmental disorders: Where do we stand and what’s next? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, R.A. Attachment: Some Conceptual and Biological Issues. In The Place of Attachment in Human Behavior; Parkes, C.M., Stevenson-Hinde, J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, R.; Glier, S.; Bizzell, J.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Campbell, A.; Killian-Farrell, C.; Belger, A. Stress-related hippocampus activation mediates the association between polyvictimization and trait anxiety in adolescents. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, R.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Glier, S.; Bizzell, J.; Campbell, A.; Belger, A. Neural mechanisms of acute stress and trait anxiety in adolescents. Neuroimage Clin. 2021, 29, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, P.A. Social support as coping assistance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 54, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, R.; Sexton, H.; Søgaard, A.J. The Finnmark Study. A prospective population study of the social support buffer hypothesis, specific stressors and mental distress. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2001, 36, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallers, M.H.; Charles, S.T.; Neupert, S.D.; Almeida, D.M. Perceptions of childhood relationships with mother and father: Daily emotional and stressor experiences in adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.S. Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Szyf, M. The epigenetics of perinatal stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, I.C.G.; Cervoni, N.; Champagne, F.A.; D’Alessio, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Dymov, S.; Szyf, M.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimi, K.; Bürgin, D.; O’Donovan, A. Psychological resilience to lifetime trauma and risk for cardiometabolic disease and mortality in older adults: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 175, 111539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jie, W.; Huang, X.; Yang, F.; Qian, Y.; Yang, T.; Dai, M. Association of psychological resilience with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in older adults: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.C. Gene × environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: The problem and the (simple) solution. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]