Abstract

Mortality studies comparing married men to never-married or formerly married men have consistently found that married men have a noticeable mortality advantage. This paper takes a novel perspective—examining mortality outcomes from the perspective of married men only and comparing those who coreside with any parents, in-laws, or their spouse only. The analyses use CenSoc data set, consisting of the 1940 Full Count United States Census linked to the Social Security Administration Death Master Files and includes 1.7 million married men between the ages of 21 and 45 years old residing with their spouse, and who died between 1975 and 2005. The results show that married men who live with only a spouse but no parental generations have an older age at death, and being a household head has an additional advantage. Living with either or both of their parents is associated with a reduction in life of 4 months, or 2 months for those who live with their in-laws. The conclusion reached is that longevity is associated with the possible burden of living with one’s parents, coupled with the reasons that may have led to the particular living arrangement. The effect of coresidence is, in turn, filtered through expectations about intergenerational relationships and norms regarding coresidence. The coresidence experience can become part of a trajectory, leading to declines in longevity.

1. Introduction

The importance of family ties has long been established in understanding the risk and timing of mortality [1,2]. Of these, one of the most important risk factors is whether one is married, such that married persons, particularly men, enjoy longer life expectancies than those who are not [3,4,5]. Studies examining mortality patterns for men compare married men to never-married or formerly married men, but few examine different forms of family structure for married men. Yet family structure is salient for mortality patterns, something that has been clearly documented for children’s mortality [6], as well as for adult mortality in later life [7]. Despite these patterns, connecting early-life family structure to later-life mortality for adults is much less explored. Moreover, the majority of studies connecting family structure to mortality are cross-sectional, and even those with longitudinal approaches [4,8,9] rarely incorporate early life familial contexts in addressing later life mortality. The present study fills in this gap with a comparison of age at death in later years for married men who coresided in multigenerational households during early- to mid-adulthood. It achieves this by utilizing the recently released CenSoc data, consisting of data from the 1940 Full Count Census linked to the Social Security Administration Death Master Files (DMF), in order to examine married men’s coresidence and the presence of parental generations, that is, the parents or in-laws. Research regarding mortality associations from other forms of intergenerational coresidence was used to build a framework for understanding this pattern. The results show that married men living with either or both of their own parents are associated with about 4 fewer months of life, and living with in-laws is associated with around 2 months fewer. The difference of a few months may not seem meaningful, even if statistically significant, but at a population level, mortality researchers herald gains in life expectancy at birth of months, and even the slightest decline is a cause for concern (e.g., [10]). Note that the studies comparing mortality for married versus non-married men that find differences of about one to three years [11] use life expectancy starting at a later age. Life expectancy at, say, age 65 is not comparable to average age at death, as it includes selectivity as well as cumulative effects of health behaviors. As a sensitivity test, a model comparing marital statuses by birth cohorts was run. It resulted in differences of several months in the expected directions, something which makes the distinctions among these married men even more noteworthy.

The various pathways explaining married men’s longevity relative to other men frequently, although not exclusively nor directly, point to the family-based support systems, which are an important factor in well-being [12,13]. Spouses—wives, in particular—are instrumental in providing encouragement for health-related behaviors, such as making doctor appointments [5], and wives tend to be the spouse that develops and maintains social relationships with family and friends [14]. Marriages are also a form of structured stability, another factor in health [15,16,17]. Married men are less likely than unmarried men to take on risky behaviors [2,18]. In addition to benefitting from these protected and supportive resources in marriage, selectivity in marriage has long been a consideration, such that men who marry have more social capital and better health compared to those who never marry or divorce [3,19]. Further, healthier and more responsible men are not just attractive marriage partners; they are also sought after by employers for job opportunities and promotions, leading to more solid economic well-being, which is also a predictor of health [20].

While the spousal relationship has long been the focus of married men’s well-being, the social network/health nexus of intergenerational coresident households has been much less explored. The proximity afforded by intergenerational coresidence serves as a form of social exchange and intergenerational transfer [21]. Exchanges could be positive, e.g., through financial [22], instrumental or emotional support [11]; they could also be negative, e.g., through financial or physical burden, conflict, or emotional stress [23]. Additionally, social and instrumental support between any generation in the household depends on factors such as the family member’s health, labor force participation, the overall context of short-term business cycles, societal-level events, and secular socioeconomic trends. Accordingly, it is appropriate to consider both the need for and availability of supportive and/or stressful adult family members within the household as a factor underlying mortality differentials.

1.1. Intergenerational Households

Until 1940, most elderly adults lived with an adult child at some point in their lives [24,25], such that in 1940, 40% of elderly adults lived with an adult child [26]. Coresidence in an adult child’s home, rather than in the parents’ home increased with age [27]. The prevalence of intergenerational living arrangements with two or more adult generations, as in a married couple living with one or more of their parents or in-laws, has varied since the late 19th century as a result of two macro-societal changes. The first transition was from a largely agrarian society to an industrial economy, followed by a post-industrial service or “knowledge-based” economy. The second transition was the change in proportion of Americans who are foreign-born, who are more likely to coreside, assuming both generations are in the country [28]. The percentage of foreign-born persons in the United States ranged from a high of about 19% in the early part of the 20th century, to a low of nearly 5% in the middle 20th century, and was close to 18% in 2020 [29,30].

The form and prevalence of intergenerational coresidence reflected the need for financial and instrumental support. Intergenerational coresidence served both as a form of old-age security for older adults (e.g., [31]) and as a stage before financial independence for adult children. Later, rising real wages and increased opportunities for workers resulted in a trend towards more independent living [26,32]. While it is logical that frail elderly parents would be the recipients of support, other research indicates that this support flows in both directions and evidence points to the adult children as the generation receiving the balance of this largesse [27,33]. Others have found that the flow’s direction is qualified by whether the parent or the child is the householder [34].

Until the middle of the 20th century, a noticeable proportion of adult children lived in their parents’ home even after they married, prior to establishing independence. Since that time, however, when adult children were living in their parents’ home, they were typically unmarried and dependent [35,36]. From the late 19th century, independence became increasingly obtainable with rising wages, especially in the post-World War II economy. Both generations sought independence when possible [37]. The shift in demographic outcomes regarding declining family size and longer life expectancy altered expectations and patterns for coresidence. Intergenerational independence was further enhanced by the parents’ desire not to be a burden [38], and children’s desire to be independent. Only in recent years, due to the combined effects of the Great Recession [39], a steep increase in housing prices, and the more recent pandemic effects, has the percentage of unmarried children living at home increased significantly. Further, while the adult child may have received financial benefits of the living arrangement because of financial dependence [39], research has found that either or both generations may benefit from coresidence [40].

1.2. Effects of Intergenerational Coresidence

In one of the few articles examining mortality and parental coresidence that consider the younger generation’s experience through possible pathways of selectivity, stress, burden, and resource benefits, Rogers [4] did not find that living with parents or in-laws increased mortality risk compared to living with just the spouse, but he did not examine differences by sex of parent, nor did he distinguish between parents and in-laws. Hughes and Waite [41] found a weak effect for poorer health among single men living with at least one parent, but the negative effect for married men was erased by adding economic controls. This result points to a resource deprivation hypothesis, suggesting that various selectivity factors, such as health and financial hardship, are the source of stress, not the coresidence itself. In more recent work, Chiu [8] used longitudinal HRS data and found that both married men and women living with just a spouse lived longer and reported fewer years of disability. Therefore, there are likely more strains than benefits for men living with a parental generation, but the mechanism is not well understood.

The rationale that married men’s longevity would be affected by coresidence with parents—either increasing it through support and positive selectivity or decreasing it through burdens and negative selectivity—derives from the much larger body of research about the effects of intergenerational coresidence for the older generation in the household. This research has found that living with adult children may increase depression and stress [42,43] and reduce marital relationship quality [44], or overall quality of life [45]. In contrast with the older generation, the focus on early-life effects on coresidence and health outcomes has been explored more thoroughly for children’s well-being, finding substantial evidence that connected early life conditions in terms of exposure to disease to later health outcomes [46,47,48,49], disease exposure to socioeconomic outcomes [50], and early life socioeconomic conditions to later life family structure [51].

One can also derive theoretical support for the hypothesis that married men’s longevity would be affected by coresidence with parents from the research about the effects of intergenerational coresidence for the grandparent and grandchild generations. The results have been mixed, depending on the familial and economic context [52], and research efforts have not always distinguished between the nuances of family structure [53]. One example of this literature is a recent study that examined long-term consequences for children living with a grandparent, finding coresidence to be an advantage for cognitive health much later in life [54], but not for mental health [55]. As for the older generation, adults who reside with grandchildren are often negatively selected for physical or financial well-being, so outcomes tend to be poor and the direction of effect is unclear [34]. Alternatively, or at the same time, the grandparent generation can benefit from positive exchanges with their adult children and grandchildren, resulting in, for example, reduced depression [56].

All told, the literature points to benefits and costs for the different coresiding generations, depending on the context and the direction of flow in intergenerational exchanges [57]. It is well-documented that there can be emotional fall-out from intergenerational coresidence for the older generation: it is logical to assume that if one generation receives psychosocial benefits or detriments of coresidence, the other half of the relationship might as well.

1.3. Model and Hypotheses

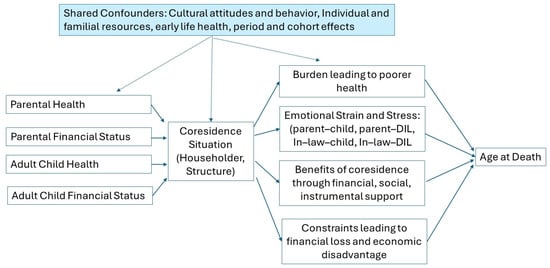

Based on the discussion above, the overarching hypothesis is that married men will live longer if they do not live with parental generations during at least a portion of their marriage, as captured in the 1940 US Census. There are also likely to be differences between one’s own parents and in-laws, and whether one is the household head. The limitations of the CenSoc data do not allow us to test specific pathways, yet one can view the model as bringing to light several possible mechanisms, the result of selectivity as well as downstream consequences. Figure 1 presents several possible pathways connecting coresidence at one stage in the life course with later life mortality consequences, and the Discussion will refer back to them.

Figure 1.

Pathways between coresidence and mortality. Note: Solid arrows indicate the causal pathways, and dotted arrows indicate the potential confounding pathways.

The factors that led to coresidence and the results from the experience can accumulate and set the stage for a life course trajectory. Health and financial resources of both generations are generally considered to be the primary factors in intergenerational coresidence. A poor financial status for the adult children, either through lack of success or due to simply being early on their career path, is one important factor in moving in with parents. Children of farmers may also be more connected to the land, and therefore to the home, compared to non-farmers [27,58]. Similarly, parents who move in may have financial or physical needs, but they could also provide many forms of valuable support. Each of these conditions is likely associated with mortality as well, such that it is not the coresidence itself but what led to it.

Pulling these strands together, there are three possibilities to consider for pathways from coresidence to mortality. First, the experience of living with other people in the household and addressing their needs may come at the expense of the younger generation’s health, either through the burden of care or through the neglect of one’s own self. Second, having additional people outside the ‘nuclear’ family unit adds stress, for example, through lack of privacy, few boundaries for relationships, and dealing with other people’s needs and preferences, ultimately leading to strained health. Third, the presence of this additional generation has opportunity costs, leading to reduced financial well-being, and that in turn affects longevity. There are, of course, possible positive benefits as well [59], such as providing additional financial support, social support, raising children, or supporting the household production.

One also needs to distinguish between which set of parents with which one coresides. Living with one’s own parents may be associated with fewer years lived, compared to coresidence with in-laws because of stress in the parent–adult child relationship, and because it is normative for adult daughters, not sons, to take care of parents [60]. Alternatively, living with the in-laws may be more problematic for the husband and have a negative effect on longevity, as widely perceived in anecdotal stories and popular media. If the married man is the householder, he should have a benefit in terms of number of months lived as it indicates a position of strength and resources, whereas if the older generation is the householder, it could reflect a weaker position for the younger generation and therefore a reduction in months lived, such that being a householder could operate independently or moderate the coresidence experience.

As for the confounding factors, there are several possible pathways. There are cultural norms of immigrant populations versus the native-born, for example, Italian-American families often live in multigenerational households [61]. For these families, coresidence may have been considered desirable and therefore not expected to have the negative effects expected with the native-born population. Within the United States, the southern states also had different norms regarding intergenerational households, particularly Black families, because of the institution of slavery and the larger role of agriculture in the economy compared to other states [62,63], and again, the effects of coresidence might be attenuated by the desirability of the living arrangement. There are also possible period effects and cohort effects. Societal-level conditions, such as World War I, may have also affected the health of veterans, but veterans who received payments through the Bonus Act had a mortality advantage for their children [64]. The 1918 Pandemic similarly may have had an impact on health, particularly for the cohort born in 1919 [49]. Finally, it is important to contextualize familial experiences within the life course, as coresidence for a newly married young couple is likely to involve a different set of circumstances than for an older established couple with their much older parents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The emergence of linked databases connecting a wealth of information about one stage of a person’s life to a much later stage has led to the growth of research exploring the effect of early life conditions on later morbidity and mortality, including early life socioeconomic conditions [22,65,66,67] and intergenerational coresidence and cognitive functioning [54]. One reason for the substantial research exploring childhood to adulthood links is the existence of panel data such as PSID (Panel Study of Income Dynamics), NLSY (National Longitudinal Survey of Youth) and others, but these data could not include birth cohorts from much earlier in the 20th century and therefore have insufficient lifespan years for mortality studies. The recently available CenSoc-DMF data set used in this study provides a sufficient span of years. It consists of the 1940 Full Count Census [68] and, when possible, individuals who have been matched to the DMF [69]. Instructions for downloading the publicly available data and merging it to the 1940 US Census can be found on the CenSoc website (censoc.berkeley.edu). The 1940 Census is ideal for this purpose as it has a broad set of questions regarding household members and structure as well as numerous socioeconomic measures. The DMF, available through the CenSoc project for linking to the 1940 Census data set, consists of deaths for the years 1962 to 2011. Data quality checks conducted by the CenSoc team compared linked data in the CenSoc-DMF records to the Human Mortality Database (www.mortality.org). This effort led to a decision to limit the years to 1975–2005 because few had died before 1975 and because deaths recorded after 2005 were somewhat unreliable for the oldest adults [70]. The matched file contains 7.5 million cases, men only, who are in both the census file and the DMF. The data for this project are further restricted to men who were married in the 1940 Census and living with their wife, ranging in age at the time of the census from 21 to 45 years old, and the DMF death ages range from 56 to 99. This range focuses on adults who are likely to be both in the prime years of their labor force participation and in the years of raising children in the household. A further reduction is carried out by using the conservative method for matching, which gives a lower rate of false positive matches [70]. See Breen and Osborne [71] for a comparison of the CenSoc data with the total Census, who report a lower likelihood of matching for African Americans and those without a high school education, but the SES characteristics of African Americans in the CenSoc data are similar to that of the overall census population [72]. One can find a comparison of the Census data for the study population in the right-most column of Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample population within each living arrangement.

The primary dependent variable is age at death (the year of death minus the birth year), calculated from the DMF variables. The goal of the analysis is not, however, how long one lives per se, but the effect of the intergenerational living arrangements. The primary set of independent variables for married men’s family structure are constructed from variables in the IPUMS 1940 Complete Count Census (PERNUM, MOMLOC, POPLOC, MOMLOC-SP and POPLOC-SP): living with spouse only, living with one or both of his parents, or living with one or both of her parents. The 1940 Census data also allow one to identify the head of household, with the reference being those who are not head of household.

As stated above, it is not possible to disentangle the effects of all possible pathways, but some can be identified. Financial status indicators related to both mortality and coresidence include whether he is employed (yes or no), whether the home is owned (yes or no), and Duncan’s Socioeconomic Index. Education is measured with individual grades. Because 1.7 percent of cases were missing, they were assigned the mode value of 8 because 49 percent of all cases were 8 or below and an effect variable for missing cases is included. No measure of income is included as there were inconsistencies between wage earners, self-employed, farmers, and other employment statuses. Farm residence is a composite variable for living on a farm, with urban versus rural residence, leading to three categories: residence on rural farms, rural non-farm residence, and urban residence, as living on a farm through 1940 was found to be healthier than living in cities [51,73]. While most farmers, as designated by the occupation code, lived on farms, not all did, and as the focus of this analysis is living arrangements, the residential location was selected. Substituting the farmer occupation and urban/rural residence did not meaningfully alter the other coefficients. Race was recoded as White with Black as the reference (other racial groups in these data were too small and thus excluded). Immigrant status was indicated by whether the man was native-born in the United States, with foreign-born as the reference. A control for geographic location was included, with an effect variable for southern states. The resulting sample size in the multivariate models is 1,721,007. Note that while there is a temporal order of events, no causal mechanism is assumed in this model.

2.2. Method

The dependent variable is age at death. Because full mortality data is not available due to the truncation from deaths prior to 1975 and after 2005, traditional survival models are not appropriate [74]. The dependent variable is continuous, so the method is ordinary least squares regression, but because each birth cohort experiences a different mortality outcome, a fixed effects model for birth year is employed. The model fit is of the following form:

where age at death is Di, α is the general intercept, λbirth year is the fixed effect for a given year of birth, δliving arrangements is a set of dummy variables for parental coresidence, and βx is a set of regression coefficients for the control variables.

Di = α + βx + λbirth year + δliving arrangements + ϵ

After presenting patterns for coresidence by age, the multivariate analysis begins with two fixed effect models that examine living with either parents or in-laws, compared to living with none (Model 1a). The second model, Model 1b, tests for an interaction of being the head of household with coresiding parents and/or in-laws to explore whether the effect of being in one’s own home is distinct for the two different parent types, that is, having parents move in versus having in-laws move in. A third fixed model, Model 2a, examines detailed forms of living with parents and in-laws: mother or mother-in-law, father or father-in-law, and both parents or in-laws together. Model 2b tests again for the interactions of the various forms of coresidence with householder status.

The next part of the analysis is an exploration of subgroups in order to disentangle possible effects. First, separate models were run to examine interactions between statuses: southern versus non-southern states, employed versus unemployed, native-born versus foreign-born, and White versus Black. Then, outcomes for different birth cohorts for the entire sample are presented to aid in identifying life course dynamics.

Data are not weighted as not all cases have weights assigned to them, and the model controls for most components of the weights.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Intergenerational Coresidence

The descriptive statistics in Table 1 present a picture of intergenerational coresidence for married men in 1940. The majority (87.8%) of married men in our sample did not live with other parents or in-laws. Compared to married men living with a parental generation, those living with just their spouse were typically householders and older, and less likely to be in homes that were owned by the family. The distinctions among those who lived with the older generation were more pronounced. Being a household head was less common among those that lived with one parent or in-law, with just about two thirds being household heads, but for those that lived with both parents or both in-laws, the percentage of household heads dropped to 13% and 16%, respectively. Those living with parents were more likely to be living in a home that was family-owned rather than rented. Nearly all (98%) of married men who did not reside with both parents were household heads. The importance of farm residence and occupation is particularly salient for living with one parent or in-law. About 37% of men who lived with their father or both parents lived on farms, compared to 27% who lived with just their mother, and 20% overall. The percentage of those living with any of one’s in-laws was slightly higher than for those living with one’s own parents. These patterns indicate the presence of several demographic, economic, and normative behaviors regarding coresidence. The parents of husbands are more likely to be older than parents of wives, given that men tend to marry women younger than they are, so this too would affect availability of parents and in-laws. Living with a daughter may be preferred but at least one son of farmers is expected and needed to help out on the farm [24]. Younger men are less likely to be able to form their own household until a bit older and more financially secure, which may mean renting until they have enough resources to purchase their own home. Together these bivariate results suggest shifting patterns across the life course.

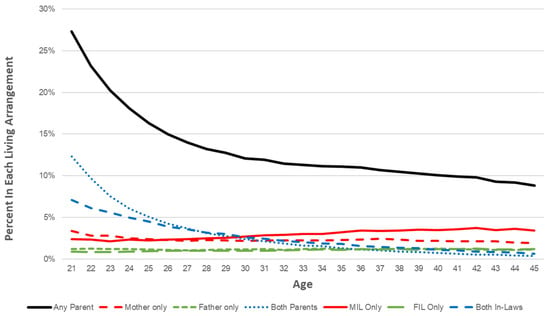

Figure 2 presents more evidence of life course changes as seen in the prevalence of intergenerational residence by age, and whether a married man coresided with parents or with in-laws. Intergenerational residence was relatively common for young married men, with a somewhat higher proportion who lived with their in-laws than with their parents. This prevalence dropped in mature adult ages and then mostly stabilized. Living with mothers-in-law, however, slightly increased and only began to decline in later ages. The percentage for coresiding with any parent declined with age, most likely due to the mortality of the older parent generation.

Figure 2.

Percentage living with parents or in-laws by age.

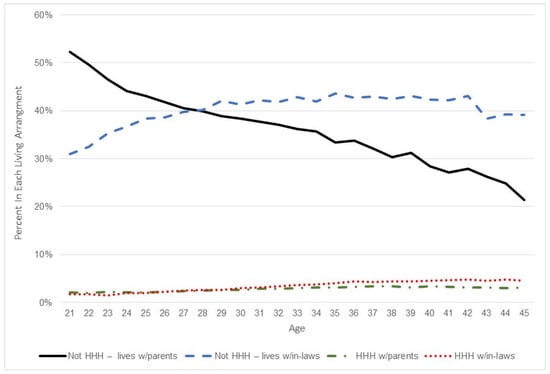

Figure 3 examines the prevalence of married men’s coresidence with parents or in-laws and compares married men who were householders to those who were not. As seen in the bottom two lines, married men who were the householders were much less likely to live with both parents than those who were non-householders (top two lines), though this propensity increased presumably as the older parent experienced health declines or widowhood and/or the adult children succeeded in attaining a higher income. The patterns for these 1940 cross-sectional data suggest that those who initially lived with their own parents as young adults ceased to do so upon independence, such that the rate of coresidence declined toward the rate of those who did not initially live in their parents’ home. In contrast, men who began living with their in-laws when not householders themselves trended toward an increase in propensity of coresidence, which flattened after the husband turned forty years old, and then declined after his forties. The results suggest a strong normative preference for coresidence with in-laws versus one’s own parents.

Figure 3.

Householder status and living with parents or in-laws by age.

3.2. Intergenerational Coresidence and Age of Death

The multivariate results in Table 2 compare living with parents or in-laws to living with neither. The results in the left-most column are the months either lost or gained, followed by the unstandardized B coefficient (for change in year of death), and then the standard errors (SE). Coresidence appears to be most deleterious in terms of length of life for married men when living with their own parents and is associated with a reduction of 3.74 months; living with in-laws has a smaller effect of 1.79 months. Specifically, the results for Model 1a support the hypothesis that living with parents or in-laws is associated with reduced average years lived. As expected, being head of household is associated with a gain for later age at death of close to 4 months. Model 1b includes the interaction terms. The results indicate that there is a negligible negative interaction effect of 0.01 of living with one’s parents when household head.

Table 2.

Fixed effects regressions: married men’s living arrangements: parents vs. in-laws.

Additional detail on specific configurations of coresident parents and in-laws is presented in Models 2a and 2b (Table 3). Living with any or both of one’s parents is associated with a lower average age at death, 5 months and 4.28 months for mothers and fathers, respectively, or either of one’s in-laws, with 1.59 and 2.77 months, respectively, for mothers-in-law and fathers-in-law. When living with both parents, the result is lower compared to one parent alone, just 1.68 months, while living with both in-laws has no significant effect. In Model 2b there are no statistically significant interaction effects for living with both in-laws when they live in the son-in-law’s home.

Table 3.

Fixed effects regressions: married men’s detailed living arrangements.

3.3. Subgroup Experience

In this portion of the analysis, subgroup differences are explored with Model 2a (detailed living arrangements) in order to test for interactions between statuses that might affect response to intergenerational coresidence. Table 4 presents the months lost (or gained) associated with coresidence, comparing four subgroups: southern states versus others, those born in the United States versus in a foreign country, employed versus unemployed, and White versus Black. There is some evidence of a distinctive southern acceptance of intergenerational living seen in the coefficients, and therefore the months lost, for living with fathers, mothers, and fathers- and mothers-in-law, as the months for these living arrangements are associated with a greater loss for non-southerners, e.g., −4.5 months for mothers in southern states but −5.2 in other states. Another geographic factor is whether one was born in the United States or foreign-born. Again, it may be that coresidence norms are stronger among foreign-born men than among those born and raised in the US. Indeed, the coefficients for US-born men are significant for all but both in-laws, whereas no living arrangement for foreign-born men is significantly different than living with no parents or in-laws. Turning to employment, an unemployed adult son coresiding with parents might be understandable even if stressful. All living arrangements for employed men, except for both in-laws, were associated with a reduction in years lived, e.g., −4.8 months for living with one’s father and −3.1 months for living with one’s father-in-law. In contrast, being unemployed was associated with significantly fewer months only for living with either parent. The fourth subgroup comparison examined was that of White and Black men. One would expect that Black men, with a stronger norm of intergenerational coresidence, would be associated with a smaller negative impact. As expected, none of the living arrangements for Black men had significant differences compared to living with no parents, whereas for White men, living with either parent or either in-law was significantly associated with fewer months lived.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis: months lost/gained for coresidence. Based on unadjusted B coefficients for specific parent combinations.

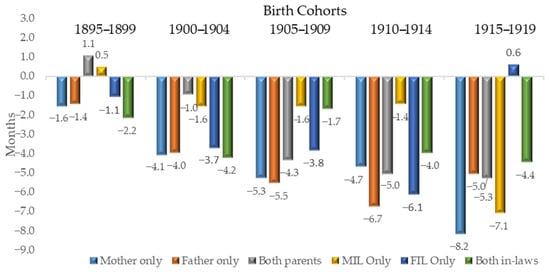

3.4. Life Course Contexts

The experience of sharing a home with parents is likely to vary according to one’s position along the life course, for example, young couples just starting out, perhaps with few financial resources, versus mature couples, likely with their own families and/or with elderly parents who may be dealing with health issues. In Figure 4, the change in months from the adjusted predicted age at death (based on Model 2a) is presented for each of the intergenerational coresidence scenarios for five-year cohorts. Because coresidence is measured only at one point in time, the cohorts are also age groups and can be viewed not only as stages in the historical context but also along the life course. The overall pattern, representing 86–87% of all combinations, indicates that there are negative consequences for longevity when living with parents or in-laws for nearly every five-year cohort and nearly every living arrangement. The younger men are associated with larger reductions in years lived, perhaps because this cohort’s life span is further from completion than those of the older cohorts, and that the frailest or least well off are more likely to coreside and would be at higher risk of early death. The oldest age group is most likely to find positive benefits with coresidence. Within each cohort, especially in the younger three cohorts, there is a tendency for the effect of living with one’s own parents to be associated with a larger effect than living with in-laws, with some variation. For example, living with either or both parents for those in the 1905–1909 cohort ranges from 4.3 to 5.5 months and 1.6 to 3.8 for the in-law combinations. While these results are a static view, they suggest the existence of a relationship—either owing to selectivity or as a consequence—between coresidence and later life health outcomes. Because coresidence is associated with larger effects for younger men than for older, the results emphasize the implications of position in the life course for intergenerational coresidence.

Figure 4.

Difference in months from living with no parents/in-laws for coresidence scenarios for five-year birth cohorts.

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses

An analysis of crowding was explored using the number of children in the household, the number of total members of the household excluding children, and the total number of people in the household. Because the number of children is a 1940 static status of household structure rather than a measure of completed fertility, it has a structural result such that the men in this sample who were closer to age 45 were more likely to have more children than those who were closer to 21, but these older men in general lived shorter lives than the younger men, who were able to benefit from the mid-twentieth century advances in medicine and reductions in smoking. Thus, the coefficient for the number of children was negative, despite completed fertility being positively associated with longevity in the US [18]. Note that the measurement for children in IPUMS, NCHILD, is the number of the husband’s children in the household and is set as equivalent to the number of the wife’s children, with no distinction made between biological, adopted, or stepchildren. Including just the number of non-kin had no effect. As a result, household size variables were not included in the analyses.

Simple OLS models without fixed effects for birth year but controlling for each birth year separately also yielded very similar results. A set of Gompertz models run as a comparison to the fixed effects models revealed fewer lost months for living with parents, whereas the detailed models obtained more months lost for living with a mother or father versus other combinations. To summarize, the results support the hypotheses that living with parents comes at a cost, whereas living with in-laws is a more mixed outcome, and these patterns are filtered through specific characteristics of the families.

4. Discussion

The results of this study support the overall hypothesis that living with an older parental generation early in a man’s married life would be detrimental for mortality. The younger age at death for married men living with one’s parents, particularly one’s father, is thus noteworthy. Interestingly, living with one’s in-laws has a smaller effect, despite popular perceptions. Several possible mechanisms may be at work related to the selectivity leading to a coresidence situation, and/or the consequences and trajectories as a result. The pathways in Figure 1 provide the outline for the discussion.

One possibility for reduced mortality is selectivity, meaning a weakness or deficit in the well-being of the married men who coresided. Compared to the older cohorts, younger adults had greater differences in age at death for coresidence compared to living without any parental generations, which suggests that these young adults may indeed have had some compelling need to coreside with parents. In contrast, older men may have been called into coresidence because their parents’ or in-laws’ health or financial circumstances required it.

Other societal and cultural factors could affect the pathway between coresidence and age at death. The findings that Black men and foreign-born men showed no differences between any form of coresidence and living without any parental generation indicates that coresidence is an expected and perhaps preferable situation. To a lesser degree, those in southern states compared to other states, with the higher proportion of agriculture affecting norms regarding coresidence, were associated with no differences between living with one’s spouse only and coresidence with in-laws.

Being the head of the household is associated with a later age of death, indicating a position of strength and well-being, yet we should note that the majority of married men who lived with both parents or in-laws were not the householders. When living with one’s own parents in the parental home, men may be late in launching into full independence. For young adults, coresidence is not particularly unexpected, but as men get older, it suggests a fundamental weakness in the husband’s ability to support himself and his family, and this weakness is likely tied to known predictors of early mortality, such as lower earnings. This mechanism is consistent with other research, indicating that while intergenerational coresidence often provides resources to the younger generation, this support may not be enough to compensate for the delayed or failed independence.

Another possible mechanism is stress. Being a household head was associated with a later age at death, so stress could occur when the man has a lower status in the household. Despite that, coresiding with a parent outweighs being a householder, such that men living with their parents may be at risk of new or unresolved parent–child relationship dynamics [75], perhaps due to disappointment in expectations of where a married son should be in his life, and/or because of the wife’s experiences with the in-laws. In contrast, living with the husband’s in-laws may be less stressful, though not without stress, as the wife is present to negotiate the relationship in a kin-keeper role extension, and also because it is normative for adult daughters to take care of parents. Relatively little is known about stress or conflict for intergenerational coresidence for adult children with parents; most research is from the perspective of the older generation (e.g., [44]) and is focused on the economic picture for unmarried children who have either failed to launch, or boomeranged back (e.g., [76,77]). While it was not uncommon for young couples to live in a parental home, as shown in Figure 1, at some point the failure of the expectation to live independently may become a source of strain in the household relationship [38,78].

It is important to consider the net benefit from these flows of support between generations. The younger generation receives a residence and perhaps childcare in exchange for providing parental care and making it possible for the older parents to age in place. Despite any older generation needs, in most cases the net intergenerational flow is to children [26]. At the same time, the results here suggest that longevity does not necessarily seem to be one of those benefits, perhaps because of the stress and strain often accompanying intergenerational coresidence. Coresidence may also result in a loss of opportunities owing to its responsibilities and commitments, which in turn may dampen financial well-being and affect mortality down the road. An exposure to greater morbidity through a reduced set of resources may also occur. While the net exchange may have short-term benefits, it may also come at a cost when viewed over the life course. Indeed, given the pattern of coresidence, with very young couples frequently coresiding, which falls to much lower levels in middle age, the net intergenerational flows from coresidence may depend on the position in the life course for both generations.

An interesting result from this analysis is obtained by focusing on the adult son as the unit of analysis. Research on intergenerational coresidence that uses the parent as the unit of analysis has highlighted the high incidence of older parents living with their children, yet from these results it is clear that living with parents is generally uncommon for the younger generation past age 25, insofar as the cross-sectional 1940 Census data indicate. Others have noted [26,79] that the older parents were heads of household when coresiding. When looking at this 1940 sample from the perspective of adult children who are married men, the household head was often the adult child. In other contexts, children who have failed to launch may receive net benefits with intergenerational coresidence, as they typically are not the household head, and often they have not married. The results here suggest that when the intergenerational household is one where the coresident child is the married household head, the selection is because of the younger generation’s resources and strengths, rather than those of the older generation. Further, distinguishing between home ownership versus head of household status was shown to be fruitful in understanding dynamics of intergenerational coresidence, as they function independently.

While this research explored sons and parents, a different relationship in the household—that of the husband and wife—may be another part of this dynamic. Living with one’s own parents was more problematic for married men than living with in-laws. Surprisingly, living with the wife’s parents was not associated with the same level of negative impact on longevity, perhaps because the burden—or benefit—of coresidence rests on the wife. The wife could also mediate the relationship between her parents and her husband. In addition, the familial expectation of a daughter coresiding with parents may be considered more acceptable than a son, regardless of whether she is residing for financial support [80]. Thus, a logical next step is to replicate and extend this research using a different death record linkage to the CenSoc data set, the Numident data set, which includes both men and women, although with a smaller sample size and fewer high-quality matches for women relative to men. Other linkage efforts with additional health data or tracking through a subsequent or previous census can also add perspective.

In addition to the age-related patterns seen in this paper, there are also cohort effects. The married couples in this study lived at a time when the country was emerging from the Great Depression, and it is likely that a high proportion were financially challenged as they entered the ‘starting out’ phase of wealth-building, which was also just prior to the phase of post-World War II economic growth. This generation went through the Pandemic of 1918–1919, which also had some long-term consequences for health [49,65]. In addition, Deaton and Stone [81] found that in countries with high fertility and high rates of coresidence, both the parents and grandparents in the household are equally well off, but in countries with low fertility and low levels of coresidence, such as the United States, coresidence tends to mean that one generation is less well off. Motivations for coresidence have evolved over time to reflect macro-level changes, e.g., increased wealth for the older generation that made it possible to ‘purchase’ independent living for more years. Young adults in the 2020s are facing very high housing costs, and once again, young people are staying home and coresidence is increasing. The COVID pandemic also exposed the vulnerabilities in centralized senior residence options. These changes are concurrent with the changes in propinquity of generations. It is easier to make the decision to coreside when the generations live near each other, but that likelihood has decreased substantially over time [79]. Thus, on the one hand, parents will have fewer options for coresidence, but on the other, the percentage of adult children experiencing coresidence will be higher with fewer siblings available for dependent parents, possibly constraining the selection effect for which child is designated as the coresident one.

Limitations

CenSoc data has been used in a number of analyses linking the 1940 status with mortality outcomes (e.g., [82,83]) yet certain limitations to this study derive from the specific nature of the data, in addition to the issue of cross-sectional data discussed above. First, the linkage of the death records to the 1940 Census is for deaths that occurred between the years 1975 and 2005. The age at death is truncated on both ends; that is, early deaths are not recorded, nor are later deaths, perhaps weakening the strength of these results. Another limitation is that it is not possible to know whether the parents or in-laws are still living, health statuses of any family members, the financial or health need for coresidence, or the number of siblings available other than the referent men in this analysis, although it is technically possible to develop sibling groups for some cases [84]. As such, some details in the comparison groups are unknown. Also unknown is the length of coresidence and whether they coresided at some point before or after the census. Nevertheless, this analysis is not about their parents or siblings or the family system, but about the men’s experience as measured during that phase of their lives. These issues could be explored in future research by matching people in the 1940 Census with those in previous decennial censuses. While linkages between the 1940 Census and other data sets have opened up an entirely new area of research, the ability to link names in the Census to names in the other data sets is reduced for non-white and female populations, as well as for people with more common names [69,85].

5. Conclusions

This analysis contributes several important aspects to the literature on family and mortality. The first is considering the middle generation when examining multi-generational coresidence. The second is examining adult men’s health within the family system rather than only comparing married men to unmarried men. The third is that living arrangements at one stage in the life course may have downstream consequences, even for career-aged adults. Further research would do well to consider different typologies of intergenerational living arrangements, e.g., by life course status rather than examining average propensities, and in this way better understand the intergenerational transfers of resources and support. This kind of detail in family studies was acknowledged in a review article by Dunifon et al. [86] who concluded that while three-generational households were common, they were also highly diverse in terms of the reasons for entering into these living arrangements. Applying and expanding this model to include spouses, dyads, and the timing of marriage would likely further disentangle the relationship between intergenerational coresidence and well-being. Data permitting, this effort could include incorporating predictors of coresidence and features of the coresidence experience, e.g., caregiving responsibilities, quality of relationship, and duration. While a good deal of research has examined contexts that lead to intergenerational coresidence, this research adds to the very small body of literature on the mortality consequences for the middle generation. Future linkage models using other panel samples such as NLSY will likely add more depth of detail. That living with in-laws posed a lesser mortality risk invokes the classic paper by Ethel Shanas, “Social Myth as Hypothesis” [87], which found that elderly parents were not generally neglected by their modernizing offspring. In this work, we find little support for another myth: that parents-in-laws are the most damaging relationship for sons-in-law.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute on Aging, grant number R01AG058940 and P30AG012839, and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant number P2CHD073964.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data for this research was ascertained as exempt from IRB review by UC Berkeley’s Office of Human Subjects Research as it contains only publicly available data that has no personal identifying information and involves only deceased subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent is not relevant for this project, as response to the US Census is required by federal law.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are publicly available. The Full Count US 1940 Census may be downloaded from https://usa.ipums.org/usa/full_count.shtml and the CenSoc DMF may be downloaded from https://censoc.berkeley.edu/data/.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Joshua Goldstein and Casey Breen for helpful comments and support, Maria Osborne for technical support, and also several anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Family Relationships, Social Support and Subjective Life Expectancy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D. Family Status and Health Behaviors: Social Control as a Dimension of Social Integration. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1987, 28, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillard, L.A.; Waite, L.J. ’Til Death Do Us Part: Marital Disruption and Mortality. Am. J. Sociol. 1995, 100, 1131–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.G. The Effects of Family Composition, Health, and Social Support Linkages on Mortality. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1996, 37, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, L.J.; Gallagher, M. The Case for Marriage; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.G.; Hummer, R.A.; Tilstra, A.M.; Lawrence, E.M.; Mollborn, S. Family Structure and Early Life Mortality in the United States. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.E.; Margolis, R.; Verdery, A.M. Family Embeddedness and Older Adult Mortality in the United States. Popul. Stud. 2020, 74, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-T. Living Arrangements and Disability-Free Life Expectancy in the United States. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, E.; Kravdal, O. Reproductive History and Mortality in Late Middle Age among Norwegian Men and Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 167, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shor, E.; Roelfs, D.J.; Yogev, T. The Strength of Family Ties: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Self-Reported Social Support and Mortality. Soc. Netw. 2013, 35, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Lubetkin, E.I. Life expectancy and active life expectancy by marital status among older U.S. adults: Results from the U.S. Medicare Health Outcome Survey (HOS). SSM Popul. Health 2020, 12, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child, S.T.; Lawton, L. Loneliness and Social Isolation among Young and Late Middle-Age Adults: Associations with Personal Networks and Social Participation. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Social Isolation and Health, with an Emphasis on Underlying Mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003, 46, S39–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Grundy, E. The Association between Social Networks and Mortality in Later Life. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 1998, 8, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Crosnoe, R.; Reczek, C. Social Relationships and Health Behavior Across the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T. Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support, and Health. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 137–173. ISBN 978-0-19-508331-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kobrin, F.E.; Hendershot, G.E. Do Family Ties Reduce Mortality? Evidence from the United States, 1966-1968. J. Marriage Fam. 1977, 39, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, A.J.; Wu, J.; Witkiewitz, K.; Epstein, D.H.; Preston, K.L. Marriage and Relationship Closeness as Predictors of Cocaine and Heroin Use. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Diez-Roux, A.; Kawachi, I.; Levin, B. “Fundamental Causes” of Social Inequalities in Mortality: A Test of the Theory. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, N. Marriage Selection and Mortality Patterns: Inferences and Fallacies. Demography 1993, 30, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, D.P.; Eggebeen, D.J.; Clogg, C.C. The Structure of Intergenerational Exchanges in American Families. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 1428–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudrovska, T.; Anikputa, B. Early-Life Socioeconomic Status and Mortality in Later Life: An Integration of Four Life-Course Mechanisms. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2014, 69, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, K.S. Social Networks in Later Life: Weighing Positive and Negative Effects on Health and Well-Being. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareven, T.K. Aging and Generational Relations: A Historical and Life Course Perspective. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1994, 20, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S. Patriarchy, Power, and Pay: The Transformation of American Families, 1800–2015. Demography 2015, 52, 1797–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S. The Decline of Intergenerational Coresidence in the United States, 1850 to 2000. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 964–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S. Intergenerational Coresidence and Family Transitions in the United States, 1850–1880. J. Marriage Fam. 2011, 73, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernskaya, Z.; Tang, Z. Just Like in Their Home Country? A Multinational Perspective on Living Arrangements of Older Immigrants in the United States. Demography 2017, 54, 1973–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschman, C. Immigration and the American Century. Demography 2005, 42, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research. Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants: Immigrant Share of U.S. Population Nears Historic High. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ft_2020-08-20_immigrants_01/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Kramarow, E.A. The Elderly Who Live Alone in the United States: Historical Perspectives on Household Change. Demography 1995, 32, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, K.; Schoeni, R.F. Social Security, Economic Growth, and the Rise in Elderly Widows’ Independence in the Twentieth Century. Demography 2000, 37, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemers, E.E.; Slanchev, V.; McGarry, K.; Hotz, V.J. Living Arrangements of Mothers and Their Adult Children Over the Life Course. Res. Aging 2017, 39, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speare, A.; Avery, R. Who Helps Whom in Older Parent-Child Families. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, S64–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Aquilino, W.S. The Likelihood of Parent–Adult Child Coresidence: Effects of Family Structure and Parental Characteristics. J. Marriage Fam. 1990, 52, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, V.L.; Ferrier, P.J.; Pugh, S.M.; Bohecker, L.; Edwards, N.N. Coresidence Is Not a Failure to Launch or Boomerang Children. Fam. J. 2022, 30, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, C. Intergenerational Household Structure and Economic Change At the Turn of the Twentieth Century. J. Fam. Hist. 1998, 23, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, F.K.; Lawton, L. Family Experiences and the Erosion of Support for Intergenerational Coresidence. J. Marriage Fam. 1998, 60, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.R.; Goldscheider, F.; García-Manglano, J. Growing Parental Economic Power in Parent–Adult Child Households: Coresidence and Financial Dependency in the United States, 1960–2010. Demography 2013, 50, 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G. Coresidence between Unmarried Aging Parents and Their Adult Children: Who Moved in with Whom and Why? Res. Aging 2003, 25, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J. Health in Household Context: Living Arrangements and Health in Late Middle Age. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, T.H.; Brubaker, E. Adult Child and Elderly Parent Household: Issues in Stress for Theory and Practice. Altern. Lifestyles 1981, 4, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Marks, N.F. Linked Lives: Adult Children’s Problems and Their Parents’ Psychological and Relational Well-Being. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.M.; Kim, K.; Fingerman, K.L. Is an Empty Nest Best? Coresidence with Adult Children and Parental Marital Quality Before and After the Great Recession. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, M.; Grundy, E. Returns Home by Children and Changes in Parents’ Well-Being in Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, I.T.; Preston, S.H. Effects of Early-Life Conditions on Adult Mortality: A Review. Popul. Index. 1992, 58, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, E.; Kremer, M. Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities. Econometrica 2004, 72, 159–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, D.; Mazumder, B. The 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Subsequent Health Outcomes: An Analysis of SIPP Data. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgertz, J.; Bengtsson, T. The Long-Lasting Influenza: The Impact of Fetal Stress During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic on Socioeconomic Attainment and Health in Sweden, 1968–2012. Demography 2019, 56, 1389–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.M. The Effects of in Utero Exposure to the 1918 Influenza Pandemic on Family Formation. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2018, 30, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, M.D.; Gorman, B.K. The Long Arm of Childhood: The Influence of Early-Life Social Conditions on Men’s Mortality. Demography 2004, 41, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, K.; Casper, L. Co-Resident Grandparents and Grandchildren; Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 23–198. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1999/demographics/p23-198.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Dunifon, R. The Influence of Grandparents on the Lives of Children and Adolescents. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ryan, L.H.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Smith, J. Multigenerational Households During Childhood and Trajectories of Cognitive Functioning Among U.S. Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masfety, V.K.; Aarnink, C.; Otten, R.; Bitfoi, A.; Mihova, Z.; Lesinskiene, S.; Carta, M.G.; Goelitz, D.; Husky, M. Three-Generation Households and Child Mental Health in European Countries. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Avendano, M. Under One Roof: The Effect of Co-Residing with Adult Children on Depression in Later Life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, A.; Litwin, H. Intergenerational Financial Transfers and Mental Health: An Analysis Using SHARE-Israel Data. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S. Living Arrangements of the Elderly in America, 1880–1980. In Aging and Generational Relations Over the Life Course: A Historical and Cross-Cultural Perspective; edited by and Cross-Cultural Perspective; Hareven, T.K., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Pysklywec, A.; Plante, M.; Auger, C.; Mortenson, W.B.; Eales, J.; Routhier, F.; Demers, L. The positive effects of caring for family carers of older adults: A scoping review. Int. J. Care Caring 2020, 4, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, E.P. Parental Caregiving by Adult Children. J. Marriage Fam. 1983, 45, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, M.; Di Gessa, G.; Tomassini, C. A change is (not) gonna come: A 20-year overview of Italian grandparent–grandchild exchanges. Genus 2021, 77, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J. Southern families. In The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia; Coleman, M.J., Ganong, L.H., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, J.; Batson, C. Under One Roof: A Review of Research on Intergenerational Coresidence and Multigenerational Households in the United States. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghanibehambari, H.; Fletcher, J.M. Early-Life Income Shocks and Old-Age Mortality: Evidence from World War I Veterans’ Bonus. SSRN 2025, 4499916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnry, M.; Palloni, A. Early life exposures and the occurrence and timing of heart disease among the older adult Puerto Rican population. Demography 2010, 47, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherwood, S. Does a Prolonged Hardship Reduce Life Span? Examining the Longevity of Young Men Who Lived through the 1930s Great Plains Drought. Popul. Environ. 2022, 43, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghanibehambari, H.; Engelman, M. Social Insurance Programs and Later-Life Mortality: Evidence from New Deal Relief Spending. J. Health Econ. 2022, 86, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggles, S.; Nelson, M.A.; Sobek, M.; Fitch, C.A.; Goeken, R.; Hacker, J.D.; Roberts, E.; Warren, J.R. IPUMS Ancestry Full Count Data, Version 4.0 [Dataset]; IPUMS: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.R.; Alexander, M.; Breen, C.; Miranda González, A.; Menares, F.; Osborne, M.; Snyder, M.; Yildirim, U. CenSoc Mortality File, Version 3.0; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, C.F.; Osborne, M. An Assessment of CenSoc Match Quality; CenSoc Working Paper; University of California, Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://censoc.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/censoc_match_quality_report_2_1.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Abramitzky, R.; Boustan, L.; Eriksson, K.; Feigenbaum, J.; Pérez, S. Automated Linking of Historical Data. J. Econ. Lit. 2021, 59, 865–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, C.F.; Osborne, M.; Goldstein, J.R. CenSoc: Public Linked Administrative Mortality Records for Individual-Level Research. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thelin, N.; Holmberg, S.; Nettelbladt, P.; Thelin, A. Mortality and Morbidity among Farmers, Nonfarming Rural Men, and Urban Referents: A Prospective Population-Based Study. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 15, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, J.R.; Osborne, M.; Atherwood, S.; Breen, C.F. Mortality Modeling of Partially Observed Cohorts Using Administrative Death Records. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2023, 42, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, A. Solidarity and Conflicts in Coresidence of Three-Generational Immigrant Families from the Former Soviet Union. J. Aging Stud. 2002, 16, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, S.J.; Lei, L. Failures-to-Launch and Boomerang Kids: Contemporary Determinants of Leaving and Returning to the Parental Home. Soc. Forces 2015, 94, 863–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, M.; Billari, F.C. Leaving Home, Moving to College, and Returning Home: Economic Outcomes in the United States. Popul. Space Place. 2020, 26, e2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R.A. A Time to Leave Home and A Time Never to Return? Age Constraints on the Living Arrangements of Young Adults. Soc. Forces 1998, 76, 1373–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.A. The Decline of Patrilineal Kin Propinquity in the United States, 1790–1940. Demogr. Res. 2020, 43, 501–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitze, G.; Logan, J.R. Sibling Structure and Intergenerational Relations. J. Marriage Fam. 1991, 53, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.; Stone, A. Grandpa and the Snapper: The Wellbeing of the Elderly Who Live with Children; NBER Working Paper; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c12962/c12962.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Helgertz, J.; Warren, J.R. Early Life Exposure to Cigarette Smoking and Adult and Old-Age Male Mortality: Evidence from Linked US Full-Count Census and Mortality Data. Demogr. Res. 2023, 49, 651–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghanibehambari, H.; Fletcher, J. Unequal before Death: The Effect of Paternal Education on Children’s Old-Age Mortality in the United States. Popul. Stud. 2024, 78, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, C.F. The Longevity Benefits of Homeownership: Evidence From Early Twentieth-Century U.S. Male Birth Cohorts. Demography 2024, 61, 1731–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramitzky, R.; Mill, R.; Pérez, S. Linking Individuals across Historical Sources: A Fully Automated Approach. Hist. Methods J. Quant. Interdiscip. Hist. 2020, 53, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunifon, R.E.; Ziol-Guest, K.M.; Kopko, K. Grandparent Coresidence and Family Well-Being: Implications for Research and Policy. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2014, 654, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanas, E. Social Myth as Hypothesis: The Case of the Family Relations of Old People. Gerontologist 1979, 19, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).