Abstract

The global decarbonisation strategy has accelerated the shift toward renewable energy and electric transport, demanding advanced electrochemical energy storage systems. Conventional anodes such as graphite and silicon composites face challenges in conductivity, stability and cycling performance. MXenes, a class of two-dimensional (2D) materials, offer promising alternatives owing to their metallic conductivity, tunable surface chemistry and high theoretical capacity. Here, we synthesise and characterise Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx (T = O, OH, F and/or Cl) MXenes for lithium-ion battery anodes and supercapacitors. Unlike Ti3C2Tx, which stores charge via intercalation and surface redox reactions, Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx exhibit conversion-type mechanisms. We also identify novel V2C–VOx heterostructures, achieving a specific capacitance of 532.4 F g−1 at 2 mV s−1 and an initial capacity of 493.3 mAh g−1 at 50 mA g−1 in lithium half-cells, with a low decay rate of 0.071% per cycle over 200 cycles. Pristine Mo2TiC2Tx shows 391.7 mAh g−1 at 50 mA g−1, decaying by 0.109% per cycle. These results experimentally validate theoretical predictions, revealing how MXene structure and transition metal chemistry govern electrochemical behaviour, thus guiding electrode design for next-generation batteries and supercapacitors.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are an integral part of the global decarbonisation strategy. With this growing demand comes a technological race to develop novel advanced material chemistries to obtain an edge in enhancing battery performance. One of the large domains of research focus is the anodes which are typically associated with enhancements in energy capacity, charging times and cycling durability (capacity retention). Moving on from conventional graphitic and hard carbon anodes, materials such as silicon, silicon oxide and silicon carbides have become a stepping stone and core area of commercialisation that will eventually segue to solid-state (and metallic anode) batteries [1,2]. However, although these materials improve the capacity of the devices, they primarily suffer from poor conductivities and rapid degradation. Various strategies have been employed to improve the performance of such materials by reducing particle size, alloying the element and finding a common route of nanoparticle encapsulation within a host matrix [2,3].

Graphene (and derivatives), such as those that are commercially viable at the required volume, namely reduced graphene oxide and liquid-phase exfoliated graphite (forming graphene nanoplatelets, also referred to as GNP) are widely researched host matrix materials for silicon. However, they still suffer from poor conductivity due to intrinsic defects and structural compositions arising from the chosen manufacturing routes. Therefore, this is an area in which alternative host materials such as MXenes are being widely researched; unlike GNP, MXenes are intrinsically conductive regardless of their few-layer structures, and they do not suffer from in-plane defects typical in reduced graphene oxide, as MXene synthesis avoids the significant structural changes that reduce conductivity in graphene-based matrices.

MXenes are intrinsically metallic with surface moieties that not only make them processible in polar and non-polar solvents (a benefit for commercial manufacturing) but also contribute to surface based pseudo-capacitive reactions together with electrochemical double-layer capacitance (EDLC). This has the potential to not only improve the conductivity of the anode, which could lead to more efficient batteries with faster charging times but also, consequentially, greater energy capacities with enhanced durability. MXenes have demonstrated significant enhancements to various aspects of electrochemical energy storage [4]. However, with regard to their application as anode materials in LIBs, the charge storage mechanism falls into two main types, which are intercalation (structure-dependent) and conversion via surface-mediated reactions. One of the first studies on MXenes for anodes in LIBs was a work by M. Naguib et al. [5]. In this work, they accomplished Li insertion into layered, partially oxidised Ti2C fabricated using the HF process. The peak capacity they were able to obtain was 225 mA h g−1 at 0.04 C. At 10 C, it managed to retain 70 mA h g−1 after 200 cycles. These early experimental discoveries demonstrated the capability of MXenes as Li anode materials and subsequently led to a flurry of research activity, both theoretical and experimental, in this area [6].

In 2014, Y. Xie et al. [7] performed early experimentation and density functional theory (DFT) simulations to evaluate how the surface structure of MXenes impacted the Li-ion energy storage capacity. The discoveries made were extensive, hence their findings will be briefly summarised here. Firstly, they established that the nature of the surface functional groups played a big role in the theoretical capacity of the MXene and thus also found that, generally, -O terminations on the MXenes exhibit the highest theoretical Li-ion storage capacity. In their experimental work, they found that Ti2C, V2C, Nb2C and Ti3C2 had vastly superior lithium capacities than what was theoretically predicted [8]. This therefore called for a new description to explain where the excess capacity was coming from. They established through DFT simulations that it was energetically favourable for additional Li atoms to adsorb onto lithiated -OH passivated surfaces and thus was unfavourable for Li intercalation [7]. However, surface reaction of -OH with Li could result in conversion of -OH into -O terminations or bare MXene (Equations (1) and (2)), which was favourable as it enabled an increased number of adsorbed Li+ ions on the MXene surface. However, they found that this was still insufficient to explain the increased capacity. This additional capacity could be further explained by the ability of additional Li layers to form atop the lithiated O-terminated MXenes [7]. This was also supported by the fact that delaminated Ti3C2Tx had significantly higher Li storage capacity than the conventionally stacked Ti3C2Tx found from HF etching. A further interesting observation that these authors made was that Nb2C and V2C MXenes had experimentally higher reversible Li capacities compared to Ti-containing MXenes, potentially due to inherently fewer -OH groups (lower concentration) resulting in faster Li diffusion and fewer trapped reaction products [7]. Additionally, the low diffusion barriers of O-terminated MXenes enabled facile Li-ion movement, thus allowing the MXenes to perform at high rates.

The authors subsequently also built upon their work and studied the applications of MXenes in non-lithium-ion batteries. Similarly, they found that O-terminated (and bare) MXenes had excellent characteristics for implementation as anode materials [9]. In addition, the charge storage processes experienced by MXenes are more complex than originally thought. Initially, as found previously, the -OH will convert into an -O termination, which can then form metal oxides (with the inserting ion) and bare MXenes via a reversible conversion reaction (as seen in Equation (3)). Furthermore, metal ions can further intercalate into the bare MXene, forming a metallic surface adsorbed layer (more than one layer will form in the case of Mg2+ and Al3+) [9]. Hence, MXenes can experience three storage mechanisms cumulatively, which are conversion reactions, intercalation/deintercalation and plating/stripping (of the metal deposited on the MXene surface). Further theoretical studies have validated the discoveries and observations made by these authors [10,11].

Considering these theoretical discoveries, we can observe in experimental work by R. Cheng et al. [12] that modifications to Ti3C2Tx surface structures can significantly affect Li-ion storage behaviour. NH3 treatment of Ti3C2Tx results in one redox couple as opposed to the expected double-redox couple in as-synthesised Ti3C2Tx. This is attributed to variations in the interlayer spacing, which affects Li diffusion. Hence, physical characteristics such as MXene sheet size and interlayer spacing also have governance of the overall performance of MXene in the anode, bridging theoretical understanding and what can be achieved in practice. Studies by H. Zhang et al. [13] experimentally validated that, by carefully annealing Ti3C2Tx, they were able to successfully reduce the amount of -F and -OH terminations on the MXene, which not only enhanced the electronic conductivity of the material but was also able to enhance the adsorption of Li, resulting in greater charge storage capabilities of 221 mA h g−1 at 0.1 C (where C was defined as 320 mA h g−1).

Moving away from Ti3C2Tx, B. Yan et al. [14] explored how the surface chemistry of V2CT2 (whereby T was -O or -S) could influence the performance of the MXene. Computational results demonstrated that -F and -OH on V2C inhibited rapid Li-ion transport, thus reducing the lithium capacity of the material significantly. However, if -O and -S terminations were anchored to V2C, the material remains metallic, even after lithiation, whilst lithiated -F and -OH sites were semi-metallic (low band gap semiconductors). Subsequent experimental studies by F. Liu et al. [15] supported these discoveries and managed to observe a capacity of 260 mA h g−1 at 370 mA g−1 with high purity V2CTx. Further to this, Anasori et al. [16] carried out a blended computational and experimental study comparing the performance of Mo-based MXenes—Mo2TiC2, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ti3C2—as electrodes for lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitor electrodes. An insightful take away from this study was that, despite Mo2TiC2Tx and Ti3C2Tx being isostructural (only surface metal atoms differ), their electrochemical behaviour differs, suggesting that Ti atoms do not play a major role in the electrochemical behaviour of the molybdenum MXene, i.e., the material behaves as a pure Mo MXene. Beyond demonstrating the analogues of lithium adsorption energy of a Mo2TiC2 MXene to a theoretical Mo3C2 MXene, the authors demonstrated the electrochemical behaviour of Mo2TiC2 as lithium-ion battery and supercapacitor electrodes. As a lithium-ion battery electrode, the MXene exhibited good Coulombic efficiency >90% at 180 cycles. A 12 µm MXene ‘paper’ electrode demonstrated a good capacitance of 342 F cm−3 at 2 mV s−1 and 167 F cm−3 at 10 mV s−1. Galvanostatic cycling also demonstrates excellent capacitance retention at 10,000 cycles. Additionally, the majority of the lithiation for Mo2TiC2 occurs below 0.6 V vs. Li/Li+. This is indicative of the conversion reaction in Equation (3), albeit slightly altered, as can be seen in Equation (4). Notably, however, this conversion reaction was found to not be energetically favourable for the Ti3C2Tx MXene, which will only undergo the -OH to -O conversion upon Li+ adsorption.

Another interesting approach was investigated by P.A. Maughan et al. [17]. In one of the only studies with Mo2TiC2Tx, the authors, for the first time, utilised a 9-day MILD etching method to synthesise multilayered Mo2TiC2Tx. Following this, they intercalated the layered structure with tetraethyl orthosilicate which, after hydrolysis and calcination, turned into SiO2 pillared Mo2TiC2. This novel approach (considering the MXene composition being studied) resulted in a specific capacity of 320 mA h g−1 at 1 A g−1, with 80% retained after 500 cycles. This study is promising, as it indicates that if Si-based composites can be integrated into delaminated Mo2TiC2Tx, there could potentially be even greater synergistic effects than Ti3C2Tx. This is because Mo-based MXenes would naturally have a higher concentration of -O terminations on the surface (if synthesised with the HF method), allowing for more conversion reactions to occur, which will add to the already high capacity of Si. This therefore warrants further investigation.

Lastly, an aspect that should be considered is that the compositing of MXenes to form anode materials for LIBs is not limited to Si. Work by Z. Zhang et al. [18] demonstrated that Fe2O3 nanoparticles, which are a conversion reaction material, could be deposited onto crumpled Ti3C2, creating an electrode with enhanced electrochemical performance. They observed a high reversible capacity of 1065 mA h g−1 at 100 mA g−1 with 549 mA h g−1 retained after 400 cycles at 2 A g−1. This promising performance demonstrates the versatility of MXenes to behave as a host material to enhance various characteristics of other promising anode materials. An abundance of work has further explored the integration of MXene composites for LIB anodes, employing various strategies to attempt to address the challenges faced by Si anodes. Some of these strategies might include encapsulation of Si nanoparticles in porous nanospheres of Ti3C2Tx [19], anchoring of SiO2 on laminated Ti3C2Tx [20] or even self-assembling of 3D porous structures with MXene-wrapped Si nanoparticles [21]. We should also note that MXene has also been applied in areas beyond anode formulations. The literature has demonstrated the capability of MXenes to have functional enhancements to the separator [22], as electrolyte additives or anode modifications in solid-state cells [23,24,25,26,27,28], freestanding current collectors [29,30], interfacial modifiers [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] and conductive additives [40]. Cumulatively, previous works have provided evidence that MXene has the potential for synergistic effects when composited, highlighting its capability in creating more capable anode compositions and designs for future battery systems.

Overall, previous collective works demonstrate the unique and complex nature in which MXenes behave as anodic materials in LIBs. They experience a multi-faceted charge storage mechanism, which makes them stand out in the larger area of battery anode development. For the first time, this work carries out direct experimental comparative studies that explore how three different as-synthesised high purity few-layer MXenes of various transition metal chemistry (Ti3C2Tx, Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx) and structure (multi-layer Ti3C2Tx—ML-Ti3C2Tx) behave in lithium-ion half-cells, investigating their behaviour as host-matrix materials for future battery anodes. In addition to this, the investigation is extended to evaluate their capacitive performance for pseudo-capacitive or asymmetric supercapacitor electrodes.

In this work, we present an extensive experimental investigation into the synthesis, structural characterisation and electrochemical evaluation of MXenes with differing transition metal chemistries and structures, namely Ti3C2Tx, multi-layer Ti3C2Tx, Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx. The study aims to elucidate how variations in surface terminations, morphology and elemental composition influence their charge storage behaviour in lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors. Through systematic comparison, this work establishes the relationship between MXene chemistry, structural configuration and electrochemical performance, offering fundamental insights to guide the rational design of next-generation MXene-based electrodes for high-performance energy storage applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ti3C2Tx MXene Synthesis

Ti3C2Tx was synthesised using a variation of the minimally invasive layer delamination (MILD) method. In an HDPE vessel, 3 M of LiF was dissolved in 9 M HCl under stirring, and 3 g of Ti3AlC2 MAX phase was added. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 24 h, then cooled and diluted with deionized water (DIW) before centrifugation at 3500 RPM. The sediment was re-dispersed in DIW and centrifuged repeatedly until the supernatant became translucent. The supernatant was concentrated by centrifugation at 11,000 RPM, and the sediment was freeze-dried.

2.2. Mo2TiC2Tx MXene Synthesis

Mo2TiC2Tx was synthesised using a two-step HF etching and delamination process. A total of 2 g of Mo2TiC2Tx was added to 20 mL of 48% HF and stirred at 55 °C for 72 h. After cooling, the mixture was washed by centrifugation at 11,000 RPM until the supernatant reached pH 6. The sediment was dispersed in 1 wt% TBAOH, vortex-mixed and sonicated for 2 h. The product was centrifuged, washed with DIW and freeze-dried. Only the few-layer Mo2TiC2Tx was used for experimentation.

2.3. Multi-Layer Ti3C2Tx (ML-Ti3C2Tx) MXene Synthesis

Multi-layer Ti3C2Tx was synthesised by slowly adding 2 g of Ti3AlC2 to 20 mL of 48% HF and stirring for 2 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 3500 RPM and washed with DIW until the supernatant reached pH 6. The sediment was freeze-dried.

2.4. V2CTx (Scrolls) MXene Synthesis

V2CTx was synthesised using an in situ etching method. A total of 1 g of V2AlC was dispersed in 40 mL of 9 M HCl and 3.2 g of LiF and stirred at 60 °C for 120 h. After washing to pH 6, the product was sonicated in 1 M TMAOH for 2–3 h, then washed until the supernatant reached pH 7. The supernatant was freeze-dried.

2.5. Electrode and Cell Fabrication

The electrode slurries were prepared by hand-grinding the freeze-dried powdered MXene (Ti3C2Tx, Mo2TiC2Tx, ML-Ti3C2Tx and V2CTx), carbon black (Super P®), styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) with a mass ratio of 90:5:3:2 in deionized water until a homogeneous slurry was obtained. The slurry was then cast onto a copper foil with a doctor blade set at 100 µm. The coated foil was then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 24 h (under vacuum) before cutting into 15 mm electrode discs. The electrode discs were then transferred into an argon-filled glovebox (O2 < 0.1 ppm, H2O < 0.1 ppm) and assembled into CR2032 coin cells. A lithium chip was used as the counter electrode, together with a Celgard 2400 separator and 100 µL (in excess) of 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC = 1:1 (v/v) (50 µL deposited on the electrode disc and another 50 µL deposited on the separator). The mass loading of the active materials was typically in the range of 1.1–6.0 mg cm−2, corresponding to approximately 1.1 mg cm−2 for Ti3C2Tx, 1.5 mg cm−2 for V2CTx, 1.9 mg cm−2 for Mo2TiC2Tx and 6.0 mg cm−2 for ML-Ti3C2Tx electrodes. The cells were then left for 24 h before any testing was conducted. With regard to cell testing protocol, cells were first subjected to cyclic voltammetry, then to galvanostatic rate testing, followed by extended galvanostatic cycling. Unfortunately, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of the cell could not be conducted in the duration of this work due to a lack of available channels.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and Characterisation of MXenes

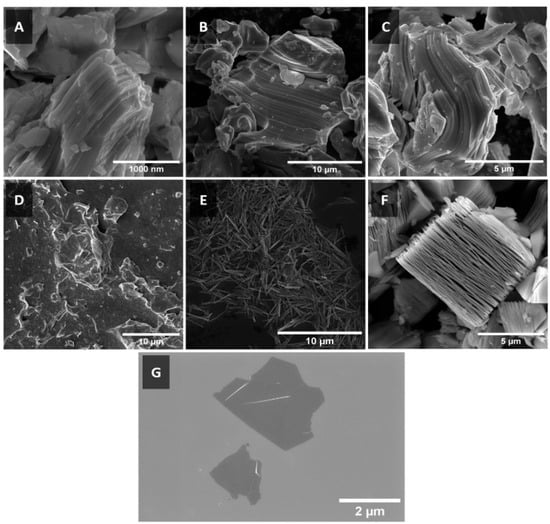

Mo2TiC2Tx was synthesised successfully from its MAX phase precursor Mo2TiAlC2 (Figure 1A) using the HF etching method. This method was also applied to synthesise the ML-Ti3C2 (Figure 1F) from the MAX phase Ti3AlC2. The MILD method was used to synthesise V2CTx and Ti3C2Tx from MAX phase precursors V2AlC (Figure 1B) and Ti3AlC2 (Figure 1C), respectively. The synthesis methods used resulted in MXenes of various morphologies. In Figure 1D, we observe a clustered agglomeration of stacked Mo2TiC2Tx MXene sheets. Although not as evident in this micrograph, the lateral dimensions of the MXene sheet are sub-micron, making it difficult to image via SEM. However, the absence of particulate materials and observed sheet-like morphologies indicate a somewhat successful etching and exfoliation of the Mo2TiC2Tx MXene.

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs of (A) Mo2TiAlC2, (B) V2AlC, (C) Ti3AlC2 MAX phases and (D) Mo2TiC2Tx, (E) V2CTx, (F) multi-layer Ti3C2Tx (ML-Ti3C2Tx), (G) Ti3C2Tx MXenes.

In Figure 1E, we can observe that the resulting V2CTx has formed needle-like scrolls instead of the expected 2D sheet morphology of MXenes. This is a unique outcome that has not been previously observed in the as-synthesised product of this MXene. It suggests that somewhere within the synthesis process, to minimise surface energy, the MXene sheet rolled up into itself, forming the scrolled morphology. A potential stage at which this may have occurred is the intercalation–exfoliation step in which TMAOH was used to intercalate the etched V2AlC and then sonication was used to exfoliate V2CTx. Further work should be conducted to evaluate the exact nature of the scrolling effect, clarifying the exact mechanism of formation, which could lead to the development of targeted processes to create other scrolled MXenes.

In Figure 1F, we observe the ‘accordion-like’ structure of ML-Ti3C2Tx formed by the HF etching process. This MXene morphology is formed by the etching of Al from Ti3AlC2, coupled with the formation of a hydrogen gas by-product, causes expansion in the ‘c’ direction of the lattice, resulting in the observed accordion morphology. The steps in this synthesis process do not produce sufficient energy (or shear force) to induce the delamination of the individual Ti3C2Tx sheets. In contrast, the use of a lithium salt in the MILD method results in intercalation of Li+ ions in this expanded structure such that, when coupled with the centrifugation and shaking steps, it facilitates the exfoliation of 2D Ti3C2Tx sheets, as can be seen in Figure 1G.

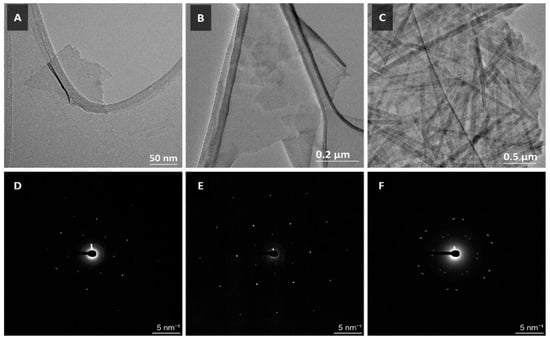

TEM of the as-synthesised MXenes also reflect a successful synthesis. In Figure 2A,B, we observe single- and few-layer sheets of Mo2TiC2Tx and Ti3C2Tx MXenes. SAED on selected regions of the sheets demonstrates monocrystalline diffraction patterns on the set of planes (0 1 0), (1 0 0) and (1 −1 0) for Mo2TiC2Tx (highest intensity diffraction spots in Figure 2D) and (−1 2 0), (1 1 0) and (2 −1 0) for Ti3C2Tx (highest intensity diffraction spots in Figure 2E). This indicates the successful synthesis of single- and few-layer Mo2TiC2Tx and Ti3C2Tx MXenes. TEM of V2CTx, as seen in Figure 2C, demonstrates an agglomerate of V2CTx MXene scrolls. SAED of a single scroll region results in a diffraction pattern in which the set of planes (0 1 0), (1 0 0) and (1 −1 0) are offset by a fixed vector angle (Figure 2F). However, the presence of a discrete electron diffraction pattern suggests that the scrolls are formed by single-layer V2CTx sheets, which is a novel discovery.

Figure 2.

TEM micrographs of (A) Mo2TiC2Tx, (B) Ti3C2Tx and (C) V2CTx MXenes. Images (D–F) are selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of (A–C), respectively.

HRTEM analysis of the as-synthesised MXenes can be seen in Figure S1. A representative selection of the HRTEM micrographs (i) that outlines a highly magnified area of the MXene is de-noised and cleaned by passing the fast-Fourier transform (ii) of the selected region through a filter, resulting in a low-noise image (iii) which allows for more accurate measurements of lattice parameters from the observed fringes. The lattice parameters of Mo2TiC2Tx as measured from Figure S3B are 2.98 Å in the (0 1 −1 0) and (1 0 −1 0) directions and 2.97 Å in the (1 −1 0 0) direction. These numbers are consistent with theoretical predictions [41]. For Ti3C2Tx, the measured lattice parameters were 2.58 Å in the (1 −1 0 0) and (1 0 −1 0) directions and 2.56 Å in the (0 1 −1 0), which are also consistent with theoretical predictions [42]. The slight variation in lattice spacing for both the MXenes across the basal planes might be attributed to some residual uncorrected objective astigmatism or errors in measurement. Unfortunately, the scrolled nature of the V2CTx MXene makes it difficult to resolve layer-specific lattice fringes (as seen in Figure S1C), hence the lattice spacing could not be determined from HRTEM.

To determine the elemental distribution of the respective MXenes, HAADF-STEM-EDS was conducted and can be observed in Figure S2. The bright spot observed on Mo2TiC2Tx in Figure S2A could be due to beam damage, which is further supported by the observed increase in carbon content in the local area in Figure S2A(iii). This supplementary characterisation method allows us to observe the homogeneous distribution of transition metals and surface atoms (oxygen, fluorine and chlorine) in the MXene. Quantitatively, it was found that for Mo2TiC2Tx, the atomic ratio of Mo to Ti was 2:1, consistent with the stoichiometric ratio. With respect to surface atoms on the MXene, the Mo to O ratio was found to be 1:2, while the Mo to F ratio was 1:0.7, i.e., the amount of oxygen moieties was roughly three times higher than fluorine. However, in Ti3C2Tx, the Ti to O atomic ratio was 1:1.7, with the Ti:F ratio being 1:0.3 and Ti:Cl ratio 1:0.1. V2CTx had a similar atomic ratio with V:O being roughly 1:1, V:F being 1:0.3 and V:Cl being 1:0.1. The difference between the two latter MXenes and Mo2TiC2Tx is the presence of a small amount of chlorine, which can be attributed to the use of HCl as the etching reagent in the synthesis process. However, we also observe that there is a greater abundance of fluorine for the Mo2TiC2Tx due to the use of HF and increased amounts of oxygen, potentially indicating partial oxidation. We conducted XPS, which further clarifies these results.

To further verify the successful synthesis of the MXenes, XRD was performed on freeze-dried powdered samples that were pressed into films. These resulting diffractograms of the MXenes and their MAX phase precursors can be observed in Figure S3. For all the MXenes synthesised, we observe the disappearance of diffraction peaks associated with basal planes in their MAX phase precursors, with the exception of the ML-Ti3C2Tx, where we can see a few very low intensity and broad peaks in the 35° to 45° 2θ region and a left shift with broadening of the (1 1 0) peak. This can be attributed to the fact that, although the MXene has been successfully etched, it has not been exfoliated, i.e., there is still some long-range crystallographic order, although the plane spacing has expanded, leading to the observed shift and broadening of the peaks. The shift to a lower angle and broadening of (0 0 2) peak indicate successful exfoliation. The determined (0 0 2) plane spacing was determined to be 1.25 nm for Mo2TiC2Tx, 1.32 nm for Ti3C2Tx, 1.21 nm for V2CTx and 1.00 nm for ML-Ti3C2Tx. These results alone indicate that the most successful exfoliation based on magnitude of the (0 0 2) spacing was Ti3C2Tx. However, it is known that Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx have some of the highest exfoliation energies amongst MXenes [43]. Thus, although the (0 0 2) spacing for Ti3C2Tx was larger, an important consideration is that greater inter-layer (or sheet) interactions in Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx can lead to denser re-stacking and hence smaller (0 0 2) spacing. This can be observed experimentally, in that the freeze-dried exfoliated Mo2TiC2Tx and V2CTx were significantly harder to disperse homogeneously in de-ionised water (DIW), requiring grinding and shear with a mortar and pestle to remove large clusters of agglomerated MXenes. Contrastingly, Ti3C2Tx dispersed homogeneously upon addition of DIW with minimal stirring.

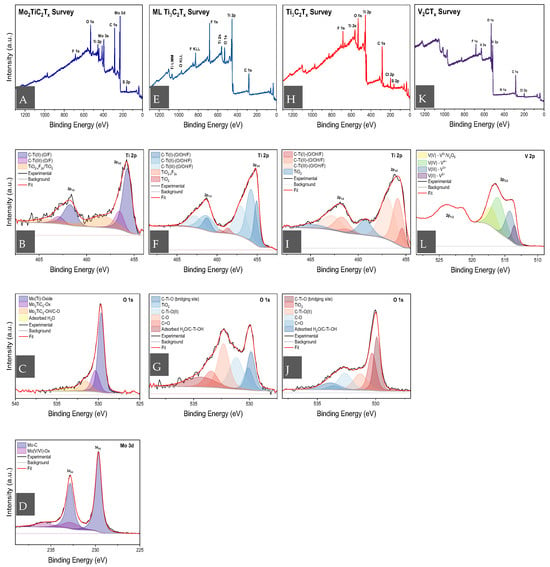

To determine the chemical composition of the MXenes, especially to determine the nature of the surface moieties, XPS was utilised. The resulting XPS data can be observed in Figure 3, where Mo2TiC2Tx survey and core-level scans are seen in Figure 3A–D, ML-Ti3C2Tx in Figure 3E–G, Ti3C2Tx in Figure 3H–J and V2CTx in Figure 3K,L. From the survey scans, we can develop a general idea of the elemental (atomic) composition of the as-synthesised MXenes. When analysing this data, we will omit carbon contributions due to the high chance of adventitious carbon contamination. When normalised against Mo (3d), in Mo2TiC2Tx, we obtain an atomic percentage ratio of 1:0.3:0.64:0.05 for Mo:Ti:O:F.

Figure 3.

XPS of: (A) Mo2TiC2Tx survey scans with core-level scans of (E) Ti 2p, (I) O 1s and (L) Mo 3d; (B) ML-Ti3C2Tx survey scans with core-level scans of (F) Ti 2p and (J) O 1s; (C) delaminated Ti3C2Tx survey scans with core-level scans of (G) Ti 2p and (K) O 1s; (D) V2CTx survey scans with core-level scan of (H) V 2p.

The non-stoichiometric ratio between Mo and Ti deviates from observations in HAADF-STEM-EDS and is difficult to explain. A potential explanation is that the harsh etching process utilised could have resulted in the oxidation of carbon and titanium (forming TiO2), forming internal point defects, resulting in titanium-deficient Mo2TiC2Tx. This reasoning could be supported by the fact that, in the core-level spectra of Ti 2p, we observe the presence of TiO2−xF2x/TiO2 states at 458.7 eV (464 eV, 2p1/2) contributing to 14.1% of the total Ti 2p bonding states. Additionally, Ti2+ (455.7 eV, 461.5 eV (2p1/2)) has a contribution of 60.2% and Ti3+ (456.7 eV, 462.5 eV (2p1/2)) has a contribution of 25.7% to the total bonding states of Ti.

The core-level emission of Mo (3d) in Mo2TiC2Tx exhibits a main peak at 229.6 eV (and 232.8 eV, 2p1/2) indicative of the Mo-C bond and is representative of 87% of the Mo bonding states. There is, however, a small presence of Mo5+/6+ oxide, represented by the peaks at 232.6 eV and 235.5 eV (2p1/2). The Mo-Ox bond represents only 13% of the total Mo bonding states. Thus, although the synthesis of Mo2TiC2Tx was a success, a small amount of the MXene was also oxidised. With regard to oxygen-based functional groups, Mo(Ti)-oxide (530.1 eV), Mo2TiC2-Ox (530.5 eV), adsorbed H2O (533.5 eV) and Mo2TiC2-OH/C-O (531.9 eV) were identified, representing 46.8%, 27.5%, 10% and 15.7%, respectively. The fluorine-based functional groups constitute a singular bonding state, C-(Mo,Ti)-F, at 685.4 eV. The F 1s component labelled as fluoride contamination corresponds to residual reaction by-products (e.g., LiF or other fluoride species) formed during the etching process, consistent with previous MXene reports. Although the C 1s peak is not typically used for quantification, it is interesting to note the presence of metal carbide peaks, Mo-C (282.2 eV) and Mo(Ti)-C (282.9 eV), as these peaks are typically used in the literature to determine the successful synthesis of non-degraded MXenes [44]. We can also observe a strong Ti-C peak in ML-Ti3C2Tx (Figure S4D) and Ti3C2Tx (Figure S4F) at 282.2 eV. It is also interesting to observe that there is a stronger contribution of C-C and C-O in the MXenes synthesised via HF etching, as opposed to the MILD method. The total contributions of C-C and C-O in Mo2TiC2Tx and ML-Ti3C2Tx are 73.4% and 60.2%, respectively, whereas it is only 44.7% for Ti3C2Tx.

Comparing the elemental composition of ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx, normalised with respect to titanium, we obtain the following atomic ratios: 1:0.45:0.43 (Ti:O:F) and 1:0.42:0.17:0.25 (Ti:O:F:Cl). With this, we observe a significantly higher fluoride content in ML-Ti3C2Tx but also a large amount of chloride being present in the Ti3C2Tx synthesised via the MILD method. Looking at the core-level spectra of Cl 2p, we determine that 77.4% of the bonding states are from Ti-Cl (199.4 eV, 201.1 eV (2p1/2)), with 22.6% attributed to potential chloride contamination (adsorbed chloride species and/or salts). In the F 1s core-level spectra, however, fluoride contamination (from reaction by-products or salts used) at 686.7 eV and 686.4 eV represents 38.3% of the fluoride bonding state in ML-Ti3C2Tx and only 24.3% in Ti3C2Tx, respectively. The other chemical state present is attributed to C-Ti-F,O bonds, which are found at 685.4 eV.

From Figure 3G,J, we can observe that the distribution of oxygen bonding states differs between ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx. A significant bond found for both MXenes is C-Ti-O, which is found at the bridging site of the MXene [44]. Found at 529.8 eV for ML-Ti3C2Tx and 529.9 eV for Ti3C2Tx, it represents 15.9% and 26.4% of the total oxygen bonding states, respectively (data summarised in Table S1). The rest of the bonding groups present TiO2, adsorbed H2O/C-Ti-OH, C-Ti2+-O, C-O and C=O constitutes 9.8% (530.1 eV), 14.8% (534.4 eV), 22.7% (531.2 eV), 26% (532.3 eV) and 10.8% (533.4 eV) and 23.7% (530.3 eV), 10.2% (533.9 eV), 17.4% (531.3 eV), 18.2% (532.6 eV) and 4.1% (533.6 eV) for ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx, respectively. Looking at the Ti 2p core-level spectra, the presence and distribution of C-Ti1+-(O/OH/F), C-Ti2+-(O/OH/F), C-Ti3+-(O/OH/F), TiO2−xF2x and TiO2 are very similar. For ML-Ti3C2Tx these bonds are found at 455.1 (461.2(2p1/2)), 455.8 (461.3(2p1/2)), 457 (462.8(2p1/2)), 459.5 (464.6(2p1/2)) and 458.6 (464.6(2p1/2)) eV, respectively. They represent 19.7%, 43.7%, 32.1%, 1.5% and 3% of the total titanium bonding states present. For Ti3C2Tx, they can be found at 455.2 (461.2 (2p1/2)), 455.8 (461.5(2p1/2)), 457.1 (462.8(2p1/2)), 459.4 (464.6(2p1/2)) and 458.6 (464.6(2p1/2)) eV, respectively, representing 17.1%, 41%, 36.6%, 1.9% and 3.4% of the bonding states present. It should be noted that in both cases, the amounts of oxyfluoride and oxide species are very low and can be subjected to significant error in XPS interpretation. Thus, the takeaway should be qualitative, in that there is a very small amount of oxide present for both the ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx, but it is insufficient to alter the overall chemical and physical properties of the MXene.

Finally, we can observe the XPS survey and core-level spectra of V2CTx in Figure 3L. Generally, the atomic ratio normalised to vanadium is determined to be 1:3.30:0.28:0.05:0.05 for V:O:F:Cl:N. The presence of nitrogen indicates a residual amount of amines present from the TMAOH utilised in the exfoliation stage of the synthesis. The significant ratio of oxygen to vanadium indicates a partial oxidation of the MXene. From the V 2p core-level spectra, we identify V5+ (517.5 eV, 2p3/2), associated with V2O5, V4+ (516.5 eV, 2p3/2), V3+ (514.3 eV, 2p3/2) and V-C/V2+ (513.5 eV, 2p3/2), representing 14.9%, 69.3%, 12.6% and 3.2%, respectively, of the total bonding states of vanadium. Low-valence vanadium, V2+ and V3+, are typically associated with V2CTx MXene, whilst higher-valence-state vanadium is typically indicative of oxides. Interestingly, previous work has found that as the outer surface of V2CTx is oxidised to a high-valence VOx, the inner crystalline structure, i.e., V-C-V sheets, can be well preserved, leading to the formation of a V2CTx-VOx heterostructure [45]. Based on the bonding state distribution observed in V 2p, this appears to be the dominant chemical state of the MXene, i.e., a mixture of pristine V2CTx, V2CTx-VOx heterostructure and V2O5. Overall, the XPS results obtained from the as-synthesised MXenes correspond with interpretations made in previous studies [17,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

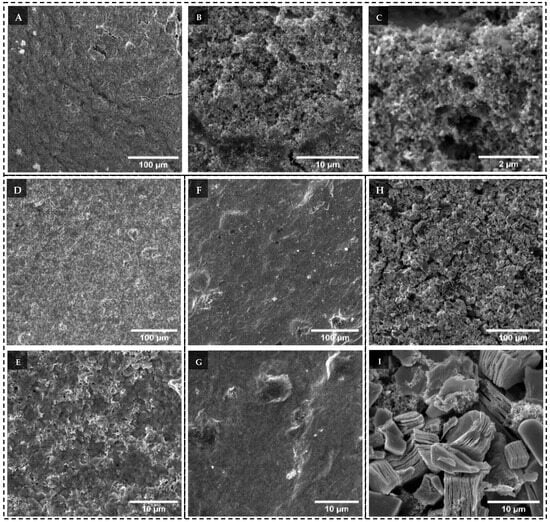

3.2. MXene Electrode Microstructure

Once the as-synthesised MXenes were characterised, they were cast onto copper foil current collectors for assembly in Li coin cells. The resulting electrode thicknesses were 33.1 ± 1.2 µm, 21.5 ± 0.5 µm, 11.3 ± 0.7 µm and 51.5 ± 0.9 µm for V2CTx, Mo2TiC2Tx, Ti3C2Tx and ML-Ti3C2Tx electrodes, respectively. The significantly thinner Ti3C2Tx electrode suggests significant re-stacking of the MXene, resulting in a dense film-like electrode. The differing morphologies of the respective MXene electrodes can be observed in Figure 4. In Figure 4A–C, we can observe the V2CTx electrodes. The surface of the electrode is rough and appears to have a high degree of porosity. Upon closer inspection, in Figure 4B, we can observe sub-micron particulates that are homogeneously dispersed on a matrix. This appears to be the potential V2CTx-VOx heterostructure identified from XPS. It is challenging to resolve, at any degree of magnification, existing V2CTx scrolls within the electrode. Therefore, a conclusion is that, due to the poor stability of pristine V2CTx, the majority of the MXene has converted into a combination of V2CTx-VOx heterostructures and VOx. SEM-EDS in Figure S5D illustrates the homogeneous dispersion of vanadium in the electrode, as well as oxygen, carbon, chlorine and fluorine. In Figure 4E, we observe the morphology of the Mo2TiC2Tx electrode, which appears to resemble dense clusters of re-stacked sheets. Comparatively, the Ti3C2Tx electrode in Figure 4G appears to have formed a dense film with no observable pores, confirming the high degree of re-stacking of the Ti3C2Tx sheets.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of (A) V2CTx electrodes at low, (B) intermediate and (C) high magnifications; (D) Mo2TiC2Tx electrodes at low and (E) intermediate magnifications; (F) Ti3C2Tx electrodes at low and (G) intermediate magnifications; (H) ML-Ti3C2Tx at low and (I) intermediate magnifications.

An explanation for the different electrode morphologies observed between Mo2TiC2Tx and Ti3C2Tx, despite them being isostructural MXenes, could be attributed to their lateral dimensions, which differ by an order of magnitude (or more). The significantly smaller Mo2TiC2Tx sheets (broken sheets due to the rigorous exfoliation steps used in the synthesis), when formed into the electrode, are unable to overlap and stack in a continuous manner, resulting in voids and porosity developing throughout the microstructure of the electrode. On the other hand, the larger, more pristine sheets of Ti3C2Tx form a continuous lay-up of sheets, with their lateral size being sufficient to occlude the space between neighbouring Ti3C2Tx sheets. This results in a densely stacked TI3C2Tx electrode, with no voids or porosity present. Despite the difference in morphology, we can observe in Figure S4A–D that the dispersion of MXene and binders is homogeneous throughout the electrode, although there appears to be a cluster of Mo2TiC2Tx still present in the Mo2TiC2Tx electrode. Finally, in Figure 4I, we can observe the ML-Ti3C2Tx electrode morphology in which the ML-Ti3C2Tx particles are interspersed with Super P conductive additive and binders. The electrode appears to have a significant number of voids and porosity formed between the MXene particles. This electrode microstructure morphology is more commonly observed in commercial electrodes, as opposed to the previously discussed MXene electrodes.

3.3. Electrochemical Performance of MXene Electrodes

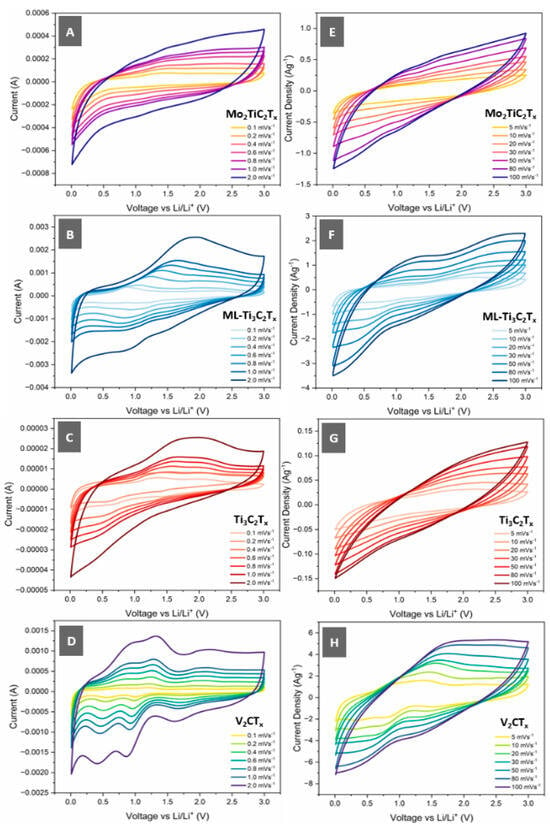

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): With the as-prepared MXenes and electrodes characterised, we can now evaluate the electrochemical performance in lithium half-cells. Figure 5 illustrates the cyclic voltammetry of the respective MXene electrodes at various scan rates between 0.1 mV s−1 and 2.0 mV s−1 (Figure 5A–D) to evaluate diffusion-dominated charge storage mechanisms and between 5 mV s−1 and 100 mV s−1 (Figure 5E–H) to look further into capacitance-dominated charge storage mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) of Mo2TiC2Tx (A), ML-Ti3C2Tx (B), Ti3C2Tx (C) and V2CTx (D) MXene electrodes between the scan ranges of 0.1–2.0 mVs−1 and (E–H) 5–100 mVs−1 between the voltage range of 0.01 V to 3.0 V in lithium half-cells (coin).

Firstly, it should be noted that as it is a half-cell, the lithiation process occurs as the potential is swept from 3 V to 0.01 V, whilst the de-lithiation process occurs when the potential is swept from 0.01 V to 3 V. In the lithiation sweep of the Mo2TiC2Tx, ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx electrodes, we see a broad and shallow peak roughly between 0.5 V and 1.25 V. This is seen prominently in the CV curve of ML-Ti3C2Tx in Figure 5B, together with a shallower and broader peak at roughly 1.5 V. This peak can also still be observed for Mo2TiC2Tx, as seen in Figure 5A, and for the lower scan rates of Ti3C2Tx, but it virtually disappears at higher scan rates. This peak, together with the pronounced peak observed in the de-lithiation sweep between 1.25 V and 2.5 V, can be associated with intercalation of Li+ and partial surface-mediated redox reactions [53]. These peaks are most pronounced on the ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx, suggesting that this is the dominant charge storage mechanism. However, the lack of a strong current response as compared to ML-Ti3C2Tx during lithiation, suggest the difficulty of lithium diffusion into the Ti3C2Tx electrode potentially attributed to the dense re-stacking. This is also potentially why we observe a broader and shallower peak for Ti3C2Tx in the de-lithiation sweep due to the difficulty in extraction of intercalated Li+ ions. This does not appear to be an issue the ML-Ti3C2Tx faces, as the voids and porosity present between the ML-Ti3C2Tx particles allow for the rapid diffusion of Li+ through the electrode and into/out of the MXene particles. On the other hand, the peaks associated with (de)intercalation are not as prominent for the Mo2TiC2Tx MXene, suggesting that it is not the main charge storage mechanism. Previous studies [16,17] have demonstrated that the primary charge storage mechanism for Mo2TiC2Tx is a conversion reaction(s) outlined in the equation below:

Mo2TiC2O2 + 2Li+ + 2e− à Mo2TiC2O2Li2

Mo2TiC2O2Li2 + 2Li+ + 2e− à Mo2TiC2 + 2Li2O

In effect, the Mo-O groups present on the surface of the MXene, which XPS has confirmed is a dominant moiety, undergo a lithiation reaction, as seen in Equation (5). This lithiated MXene is then able to undergo an additional conversion reaction with a further two moles of lithium, as seen in Equation (6). These might be the reactions associated with the peaks observed between 0.5 V and 1.25 V during lithiation and de-lithiation.

The enthalpy changes occurring in Equation (6) make it energetically favourable for the Mo2TiC2O2 MXene to undergo the reaction, whereas it is not so for Ti3C2O2 MXenes, which is why we do not observe this as being the dominant charge mechanism for the ML-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx electrodes [16].

In Figure 5D, we can observe that the CV profile of V2CTx-VOx electrodes differs substantially from those of the other MXenes. We still observe broad shallow peaks at roughly 1.6 V in the lithiation sweep and 2 V in the de-lithiation sweep, which could be attributed to intercalation/diffusion of Li+ into existing V2CTx scroll structures and potentially surface-mediated redox reactions [53]. However, in addition to these peaks, we observe lithiation peaks at roughly 0.5 V and 1 V, as well as de-lithiation peaks at 0.8 V and 1.25 V. These correspond well to a VO2 lithiation/de-lithiation process discovered in previous work [54,55]. In previous work, Bo Yan et al. [54] experimentally validated the following (de)lithiation process:

V2O5 + xLi+ + xe− → ω-LixV2O5 (2 < x < 3)

ω-Li3V2O5 + Li+ + e− → 2LiVO2 + Li2O

2LiVO2 + 2yLi+ + 2ye− → 2Li1+yVO2 (0 < y < 1)

2Li1+yVO2 ↔ 2Li1−yVO2 (0 < y < 1)

Equations (7)–(9) represent the lithiation of a V2O5 species into a lithiated Li1+yVO2 compound within the first lithiation/de-lithiation cycle. Subsequently, the predominant conversion reaction occurring is represented in Equation (10). Although this reaction mechanism elucidates the redox events observed in the CV of the V2CTx-VOx electrode and is further supported by the attainable specific capacity, further post-mortem and “in-situ” work should be conducted to empirically verify this charge storage mechanism.

Figure 5E–H demonstrate CV profiles of the MXene electrodes at high scan rates to evaluate their respective capacitive characteristics. Although capacitive charge storage via electrochemical double-layer capacitance (EDLC) is present at the lower scan rates, by increasing the scan rate, we reduce the diffusive charge storage contributions, and this will enable us to determine the capability of the MXene electrodes to function as pseudo-capacitor and/or supercapacitor electrodes. From the CV plots, we can calculate the attainable specific gravimetric capacitance, which is plotted in Figure S6.

Between the MXene electrodes, we observe similar decay in specific capacitance with scan rate. V2CTx-VOx obtained the highest specific capacitance of 532.4 F g−1 at 2 mV s−1, reducing to 381 F g−1 at 5 mV s−1 and 51.1 F g−1 at 100 mV s−1. The ML-Ti3C2Tx electrode exhibited a maximum specific capacitance of 151.9 F g−1 at 2 mV s−1 that diminished to 18.8 F g−1 at 100 mV s−1. Surprisingly, the worst performer was the Ti3C2Tx electrode, which managed 9.7 F g−1 at 2 mV s−1 and a negligible capacity of 0.73 F g−1 at 100 mV s−1.

The observed performance of the electrodes can be attributed to the chemistry and structure of the respective MXenes. In Figure 5H, we observe that despite the high scan rate, there are still some pseudocapacitive reactions occurring which might be associated with surface redox reactions and intercalation events. This phenomenon holds true for the Mo2TiC2Tx electrode, although the poorer observed capacitance might be attributed to slower reaction kinetics in the formation of Li2O, as seen in Equation (6). Surprisingly, the ML-Ti3C2Tx managed a greater capacitive performance compared to the Mo2TiC2Tx, which could be attributed to the low tortuosity and open morphology of the electrode, allowing for rapid diffusion and intercalation of Li+. The poor capacitive performance of Ti3C2Tx in this context can be associated with its highly dense re-stacked morphology. This reduces the effective electrochemically active surface area (to the top surface of the electrode) as the rest of the electrode bulk is only accessible via highly tortuous and narrow ion diffusion pathways. As a result, when the cell was subject to galvanostatic cycling, it regularly exceeded voltage thresholds and thus was not able to be characterised further. It is important to note that this is not representative of the electrochemical performance of Ti3C2Tx, as previous work [47,48,56] has demonstrated state-of-the-art capacitive performance. However, it does highlight the importance of selecting a suitable manufacturing process to leverage the performance benefits that a 2D material might offer.

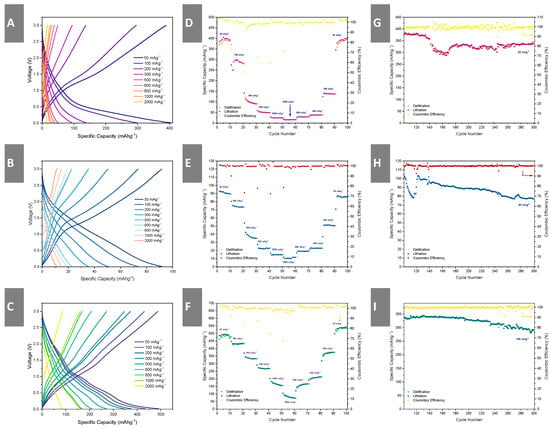

Galvanostatic Charging and Discharging (GCD): Following cyclic voltammetry measurements, the cells were galvanostatically cycled. As it is difficult to determine the exact nominal capacity of the MXene materials, the electrodes were subjected to fixed current densities between 50 mA g−1 to 2 A g−1. Figure 6 demonstrates the results from galvanostatic cycling of the MXene electrodes, including the voltage profiles, rate capability and cycling stability. In Figure 6A, we can observe the voltage profile of Mo2TiC2Tx. Unlike ML-Ti3C2Tx and V2CTx-VOx, it appears that a significant proportion of the electrode capacity comes from below 0.6 V. This is consistent with previous work [16] in which the charge storage mechanism is a conversion reaction represented by Equations (5) and (6). The voltage profile of ML-Ti3C2Tx in Figure 6B is characteristic of an intercalation mechanism, whilst in Figure 6C, the voltage profile of V2CTx-VOx has several short and shallow plateaus, which is evidence of the lithiation/de-lithiation reaction demonstrated in Equation (10). Mo2TiC2Tx has the worst rate capability (capacity retention) amongst the three electrodes. It achieved 391.7 mA h g−1 at 50 mA g−1, 297.2 mA h g−1 at 100 mA g−1, 96.1 mA h g−1 at 300 mA g−1, 50.6 mA h g−1 at 500 mA g−1, 24.4 mA h g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 15.6 mA h g−1 2 A g−1. This indicates a 96% drop in specific capacity as the current density is increased. The ML-Ti3C2Tx electrode achieved 92.8 mA h g−1 at 50 mA g−1, 73.8 mA h g−1 at 100 mA g−1, 36.4 mA h g−1 at 300 mA g−1, 22.3 mA h g−1 at 500 mA g−1, 14.9 mA h g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 10.4 mA h g−1 2 A g−1, which represents an 89% drop in specific capacity. This is still a significant decay, but slightly less so than Mo2TiC2Tx. The V2CTx-VOx electrode managed the highest capacity of 493.3 mA h g−1 at 50 mA g−1, 430.7 mA h g−1 at 100 mA g−1, 336 mA h g−1 at 300 mA g−1, 267.3 mA h g−1 at 500 mA g−1, 164 mA h g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 65.3 mA h g−1 at 2 A g−1. The electrode demonstrated an improved rate capability at intermediate current densities but still suffered from an 87% decay in capacity as current density was increased. The large decay in the specific capacity of the respective electrodes could be attributed to the low density and poor inter-particle contact in the electrode, resulting in lower electronic conductivity. It can be improved with electrode engineering approaches such as the addition of more conductive binder, reducing particle size (in the context of ML-Ti3C2Tx) or calendaring the electrode post-drying. The poor rate capability of Mo2TiC2Tx especially could also be attributed to poor reaction (Equations (5) and(6)) kinetics leading to a lower attainable specific charge capacity.

Figure 6.

Galvanostatic plots demonstrating the voltage profiles (A–C), rate performance (D–F) and cycling stability (G–I) of Mo2TiC2Tx, ML-Ti3C2Tx and V2CTx, respectively, under galvanostatic charge and discharge cycles.

All three electrodes demonstrated respectable cycling stability across 200 cycles. The V2CTx-VOx demonstrated the best cycling stability when cycled at 150 mA g−1, starting at 339.2 mA h g−1 and decaying by 14.2% (0.071% per cycle) after 200 cycles. The ML-Ti3C2Tx demonstrated the worst cycling stability, decaying by 25.8% (0.129% per cycle) across 200 cycles when cycled at 50 mA g−1. The Mo2TiC2Tx fared slightly better when cycled at 50 mA g−1, starting at 430.5 mA h g−1 and decaying by 21.8% (0.109% per cycle) across the 200 cycles.

4. Conclusions

This work has demonstrated the successful synthesis of Mo2TiC2Tx and multi-layer Ti3C2Tx via the commonly used HF etching method. Delaminated Ti3C2Tx and V2CTx were also successfully synthesised using a modified minimally invasive layer delamination (MILD) method. An unprecedented discovery was the formation of pristine monolayer scrolls of V2CTx, which is a novel morphology for as-synthesised MXenes. The as-synthesised MXenes were prepared into electrodes and evaluated in lithium half-cells as anodic and pseudo-capacitor electrodes. It was discovered that, in the preparation of these electrodes, the V2CTx naturally oxidised due to poor stability under ambient conditions, resulting in the formation of V2C-VOx heterostructures, as validated by SEM, XPS and lithiation behaviour. From electrochemical characterisation, we have evaluated the varying lithiation mechanisms of the various MXenes, concurring that both MXene transition metal chemistry and nanomaterial morphology significantly impact the resultant electrochemical performance. The Mo2TiC2Tx MXene lithiation mechanism involves the conversion reaction of Li+ with surface Mo-O groups, leading to the formation of Li2O. On the other hand, the redox behaviour of isostructural Ti3C2Tx (and ML-Ti3C2Tx) indicates lithiation occurs more often through an intercalation process with some surface-mediated redox reactions. The V2CTx-VOx heterostructure appears to undergo a mixture of conversion reactions via formation of Li1-yVO2 as well as intercalation into the remaining scroll-like V2CTx structures. It has also been discovered that the morphology of the respective MXenes led to the formation of electrodes with significantly varying morphology. The smaller lateral size of Mo2TiC2Tx mitigated extensive re-stacking, forming porosity that can act as accessible ion channels, whereas the large lateral size of Ti3C2Tx created a dense film of re-stacked MXene, reducing the accessible electrochemically active surface area. The particulate nature of ML-Ti3C2Tx with void space interspersed also allowed for ion diffusion and rapid Li+ intercalation. The hope is that this work will serve as an informative guide toward the future development of MXene composite materials for battery and supercapacitor materials via the development of a more comprehensive understanding of how the intrinsic chemistry and structure of the as-synthesised MXene, without further processing, can directly impact electrochemical energy storage device performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/esa2040016/s1.

Author Contributions

F.P.M. designed the project and conducted the majority of the experimentation and analysis involved, namely material synthesis; electrode fabrication; cell preparation; cell electrochemical testing and analysis; SEM, XRD, TEM, HRTEM, STEM-EDS, SAED, XPS sample preparation, testing and analysis. Y.G. synthesised the V2CTx MXenes utilised, providing the SEM micrographs, XPS and XRD data associated with the batch. Y.S. experimentally conducting the TEM, HRTEM, STEM and HAADF-STEM-EDS on the as-prepared samples and providing guidance on the respective analysis. M.A.B. contributed to review and editing, validation, supervision and resources. This work is part of F.P.M. and Y.G.’s Doctoral thesis [57,58]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Henry Royce Institute for Advanced Materials, funded through EPSRC grants EP/R00661X/1, EP/S019367/1, EP/P025021/1 and EP/P025498/1. Y.G. would like to acknowledge the EPSRC Graphene NOWNANO CDT, funded through EPSRC grant EP/L01548X/1. F.P.M. would also like to sincerely thank Ping Xiao at The University of Manchester who holds the Royal Academy of Engineering Research Chair in Advanced Coating Technology (appointed by Rolls-Royce).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

F.P.M. would like to firstly thank the donors to the University of Manchester for funding via the Research Impact Scholarship and The University of Manchester for the President’s Doctoral Scholar Award that supported this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors F.P.M. and Y.G. have financial interests in the commercialisation of MXene materials. All other authors declare no known conflicts of interest.

References

- Schmaltz, T.; Hartmann, F.; Wicke, T.; Weymann, L.; Neef, C.; Janek, J. A Roadmap for Solid-State Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, V.; Doerrer, C.; Dyer, M.S.; El-shinawi, H.; Fleck, N.; Irvine, J.T.S.; Lee, H.J.; Li, G.; Liberti, E.; Mcclelland, I.; et al. 2020 Roadmap on Solid-State Batteries. J. Phys. Energy 2020, 2, 32008. [Google Scholar]

- Karuthedath Parameswaran, A.; Azadmanjiri, J.; Palaniyandy, N.; Pal, B.; Palaniswami, S.; Dekanovsky, L.; Wu, B.; Sofer, Z. Recent Progress of Nanotechnology in the Research Framework of All-Solid-State Batteries. Nano Energy 2023, 105, 107994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Shuck, C.E.; Liang, G.; Gogotsi, Y.; Zhi, C. MXene chemistry, electrochemistry and energy storage applications. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naguib, M.; Come, J.; Dyatkin, B.; Presser, V.; Taberna, P.L.; Simon, P.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. MXene: A promising transition metal carbide anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 16, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, H.; Eslami-Farsani, R.; Castillo-Martinez, E. Recent trends in the development of MXenes and MXene-based composites as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Naguib, M.; Mochalin, V.N.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y.; Yu, X.; Nam, K.W.; Yang, X.Q.; Kolesnikov, A.I.; Kent, P.R.C. Role of surface structure on Li-ion energy storage capacity of two-dimensional transition-metal carbides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6385–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, P. Are MXenes promising anode materials for Li ion batteries? Computational studies on electronic properties and Li storage capability of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2X2 (X = F, OH) monolayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16909–16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Dall’Agnese, Y.; Naguib, M.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W.; Zhuang, H.L.; Kent, P.R.C. Prediction and Characterization of Mxene Nanosheet Anodes for Non-Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 9606–9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Hu, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, A. Structural Transformation of MXene (V2C, Cr2C, and Ta2C) with O Groups during Lithiation: A First-Principles Investigation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyamdelger, S.; Ochirkhuyag, T.; Sangaa, D.; Odkhuu, D. First-Principles Prediction of a Two-Dimensional Vanadium Carbide (MXene) as the Anode for Lithium Ion Batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 5807–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Hu, M.; Yang, J.; Cui, C.; Guang, T.; Li, C.; Shi, C.; et al. Understanding the Lithium Storage Mechanism of Ti3C2Tx MXene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xin, X.; Liu, H.; Huang, H.; Chen, N.; Xie, Y.; Deng, W.; Guo, C.; Yang, W. Enhancing Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion toward Extraordinary Lithium Storage Capability of Freestanding Ti3C2Tx MXene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 2792–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Lu, C.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; He, W.; Tian, W.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.M. Oxygen/Sulfur Decorated 2D MXene V2C for Promising Lithium Ion Battery Anodes. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 22, 100713. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, C.; Wang, L.; Hu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, A. Preparation of High-Purity V2C MXene and Electrochemical Properties as Li-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A709–A713. [Google Scholar]

- Anasori, B.; Xie, Y.; Beidaghi, M.; Lu, J.; Hosler, B.C.; Hultman, L.; Kent, P.R.C.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Two-Dimensional, Ordered, Double Transition Metals Carbides (MXenes). ACS Nano 2021, 33, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, P.A.; Bouscarrat, L.; Seymour, V.R.; Shao, S.; Haigh, S.J.; Dawson, R.; Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Bimbo, N. Pillared Mo2TiC2 MXene for High-Power and Long-Life Lithium and Sodium-Ion Batteries. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 3145–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Weng, L.; Rao, Q.; Yang, S.; Hu, J.; Cai, J.; Min, Y. Highly-Dispersed Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Anchored on Crumpled Nitrogen-Doped MXene Nanosheets as Anode for Li-Ion Batteries with Enhanced Cyclic and Rate Performance. J. Power Sources 2019, 439, 227107. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, M.; Chen, B.; Gu, F.; Zu, L.; Xu, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J. Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets as a Robust and Conductive Tight on Si Anodes Significantly Enhance Electrochemical Lithium Storage Performance. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, G.; Mu, D.; Wu, B.; Ma, C.; Bi, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Wu, F. Microsphere-Like SiO2/MXene Hybrid Material Enabling High Performance Anode for Lithium Ion Batteries. Small 2020, 16, 1905430. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, A.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, H. Three-Dimensional Hierarchical Porous Structures Constructed by Two-Stage MXene-Wrapped Si Nanoparticles for Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48718–48728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Tian, Y.; Feng, J.; Qian, Y. MXenes for Advanced Separator in Rechargeable Batteries. Mater. Today 2022, 57, 146–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Kota, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, S.; Qi, H.; Kim, S.; Tu, Y.; Barsoum, M.W.; Li, C.Y. 2D MXene-Containing Polymer Electrolytes for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Chen, H.; Du, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, S. Perpendicular MXene Arrays with Periodic Interspaces toward Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Anodes with High-Rate Capabilities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Luo, W.; Huo, H.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wen, Z.; Huang, Y. A Lithium-MXene Composite Anode with High Specific Capacity and Low Interfacial Resistance for Solid-State Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Guo, Z.; Hua, Q.; Wang, J.; Kou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Guo, Z.; et al. Thin polymer electrolyte with MXene functional layer for uniform Li+ deposition in all-solid-state lithium battery. Green Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Qin, X.; Shao, G. Stable Electrochemical Li Plating/Stripping Behavior by Anchoring MXene Layers on Three-Dimensional Conductive Skeletons. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 37967–37976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, F.; Liu, W.; Zuo, J.; Gu, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Vertically Aligned MXene Nanosheet Arrays for High-Rate Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Kurra, N.; Alhabeb, M.; Chang, J.K.; Alshareef, H.N.; Gogotsi, Y. Titanium Carbide (MXene) as a Current Collector for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 12489–12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Wang, P.; Ye, K.; Zhu, K.; Yan, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, G.; Cao, D. MXene-Modified Conductive Framework as a Universal Current Collector for Dendrite-Free Lithium and Zinc Metal Anode. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 625, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Tao, Y.; An, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Qian, Y. Recent Advances of Emerging 2D MXene for Stable and Dendrite-Free Metal Anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhao, C.; Lian, R.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, X.; Gogotsi, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Mechanisms of the Planar Growth of Lithium Metal Enabled by the 2D Lattice Confinement from a Ti3C2Tx MXene Intermediate Layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Fan, X.; Peng, Y.; Xue, P.; Sun, C.; Shi, X.; Lai, C.; Liang, J. Polysiloxane Cross-Linked Mechanically Stable MXene-Based Lithium Host for Ultrastable Lithium Metal Anodes with Ultrahigh Current Densities and Capacities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhai, P.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zuo, J.; Gu, X.; Gong, Y. Constructing Artificial SEI Layer on Lithiophilic MXene Surface for High-Performance Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; He, S.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; He, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, C.; Xiao, X. V2CTx MXene Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphases toward Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Anodes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9961–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, G.; Wong, C.P.; Liu, B.; Luo, L.; Chen, S.; et al. Induction of Planar Li Growth with Designed Interphases for Dendrite-Free Li Metal Anodes. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 39, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Gong, Y.; Yang, S. Horizontal Growth of Lithium on Parallelly Aligned MXene Layers towards Dendrite-Free Metallic Lithium Anodes. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, S.; Du, Z.; Du, J.; Han, C.; Li, B. MXene-Ti3C2 Armored Layer for Aluminum Current Collector Enable Stable High-Voltage Lithium-Ion Battery. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Cui, C.; Cheng, R.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. MXene Enables Stable Solid-Electrolyte Interphase for Si@MXene Composite with Enhanced Cycling Stability. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 3089–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wu, F.; Dai, X.; Zhou, J.; Pang, H.; Duan, X.; Xiao, B.; Li, D.; Long, J. Robust MXene Adding Enables the Stable Interface of Silicon Anodes for High-Performance Li-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, B.; Shi, C.; Moon, E.J.; Xie, Y.; Voigt, C.A.; Kent, P.R.C.; May, S.J.; Billinge, S.J.L.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. Control of Electronic Properties of 2D Carbides (MXenes) by Manipulating Their Transition Metal Layers. Nanoscale Horiz. 2016, 1, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A Materials Genome Approach to Accelerating Materials Innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 11002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, M.; Ranjbar, A.; Esfarjani, K.; Bogdanovski, D.; Dronskowski, R.; Yunoki, S. Insights into Exfoliation Possibility of MAX Phases to MXenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natu, V.; Benchakar, M.; Canaff, C.; Habrioux, A.; Célérier, S.; Barsoum, M.W. Critical Analysis of the X-Ray Photoelectron Spectra of Ti3C2Tz MXenes. Matter 2021, 4, 1224–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Peng, J.; Lai, W.; Wu, D.; Zuo, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Dai, Z.; et al. In-Situ Electrochemically Activated Surface Vanadium Valence in V2C MXene to Achieve High Capacity and Superior Rate Performance for Zn-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, C.; Dong, C.L.; Liu, R.S.; Han, C.P.; Li, Y.; Gogotsi, Y.; Wang, G. Single Platinum Atoms Immobilized on an MXene as an Efficient Catalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Byun, J.J.; Yang, J.; Moissinac, F.P.; Ma, Y.; Ding, H.; Sun, W.; Dryfe, R.A.W.; Barg, S. All-In-One MXene-Boron Nitride-MXene “OREO” with Vertically Aligned Channels for Flexible Structural Supercapacitor Design. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 7959–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Byun, J.J.; Yang, J.; Moissinac, F.P.; Peng, Y.; Tontini, G.; Dryfe, R.A.W.; Barg, S. Freeze-Assisted Tape Casting of Vertically Aligned MXene Films for High Rate Performance Supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Mater. 2020, 3, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazniak, A.; Bazhin, P.; Shplis, N.; Kolesnikov, E.; Shchetinin, I.; Komissarov, A.; Polcak, J.; Stolin, A.; Kuznetsov, D. Ti3C2Tx MXene Characterization Produced from SHS-Ground Ti3AlC2. Mater. Des. 2019, 183, 108143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, L.Å.; Persson, P.O.Å.; Rosen, J.J. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Ti3AlC2, Ti3C2Tz, and TiC Provides Evidence for the Electrostatic Interaction between Laminated Layers in Max-Phase Materials. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 27732–27742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Jiang, S.; Cong, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, G.; Li, Y.; Li, X. A Hydrofluoric Acid-Free Synthesis of 2D Vanadium Carbide (V2C) MXene for Supercapacitor Electrodes. 2D Mater. 2020, 7, 025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, K.; Yin, H.; Fan, L.Z. Prelithiated V2C MXene: A High-Performance Electrode for Hybrid Magnesium/Lithium-Ion Batteries by Ion Cointercalation. Small 2020, 16, 1906076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Barg, S.; Bissett, M.A. MXene-Based Anodes for Metal-Ion Batteries. Batter. Supercaps 2020, 3, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Li, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Z.; Yang, X. An Elaborate Insight of Lithiation Behavior of V2O5 Anode. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Li, L.; Manthiram, A.J. VO2/RGO Nanorods as a Potential Anode for Sodium- and Lithium-Ion Batteries. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2015, 3, 14750–14758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, J.; Byun, J.J.; Moissinac, F.P.; Xu, J.; Haigh, S.J.; Domingos, M.; Bissett, M.A.; Dryfe, R.A.W.; Barg, S. 3D Printing of Freestanding MXene Architectures for Current-Collector-Free Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1902725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moissinac, P.F. The Influence of MXene Chemistry and Structure on Electrochemical Energy Storage Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Georgantas, Y. Innovative Approaches to the Synthesis and Characterisation of MXenes and Xanes. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, June 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).