Experimental Thermal Performance of Air-Based and Oil-Based Energy Storage Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Heat Storage Systems Design and Materials Properties

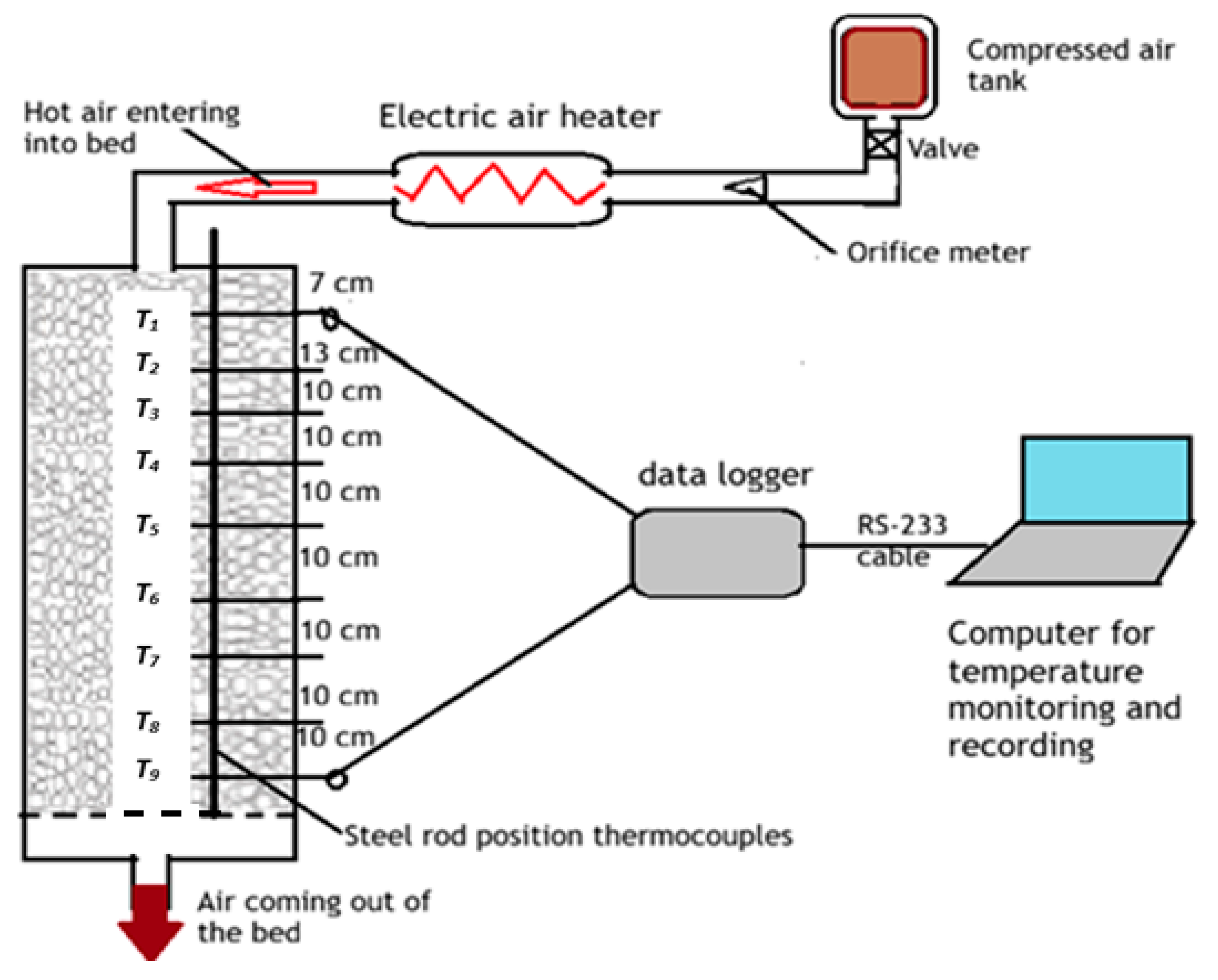

2.1.1. The Air–Rock Pebble TES System

2.1.2. The Oil-Only and Oil–Rock Bed Heat Storage System

2.1.3. The Dimensions and Material Thermal Properties

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. System Operation

2.4. Thermal Performance Analyses of the Oil–Rock Pebble TES System

2.5. Energy Consumption in Boiling Water

3. Results and Discussion

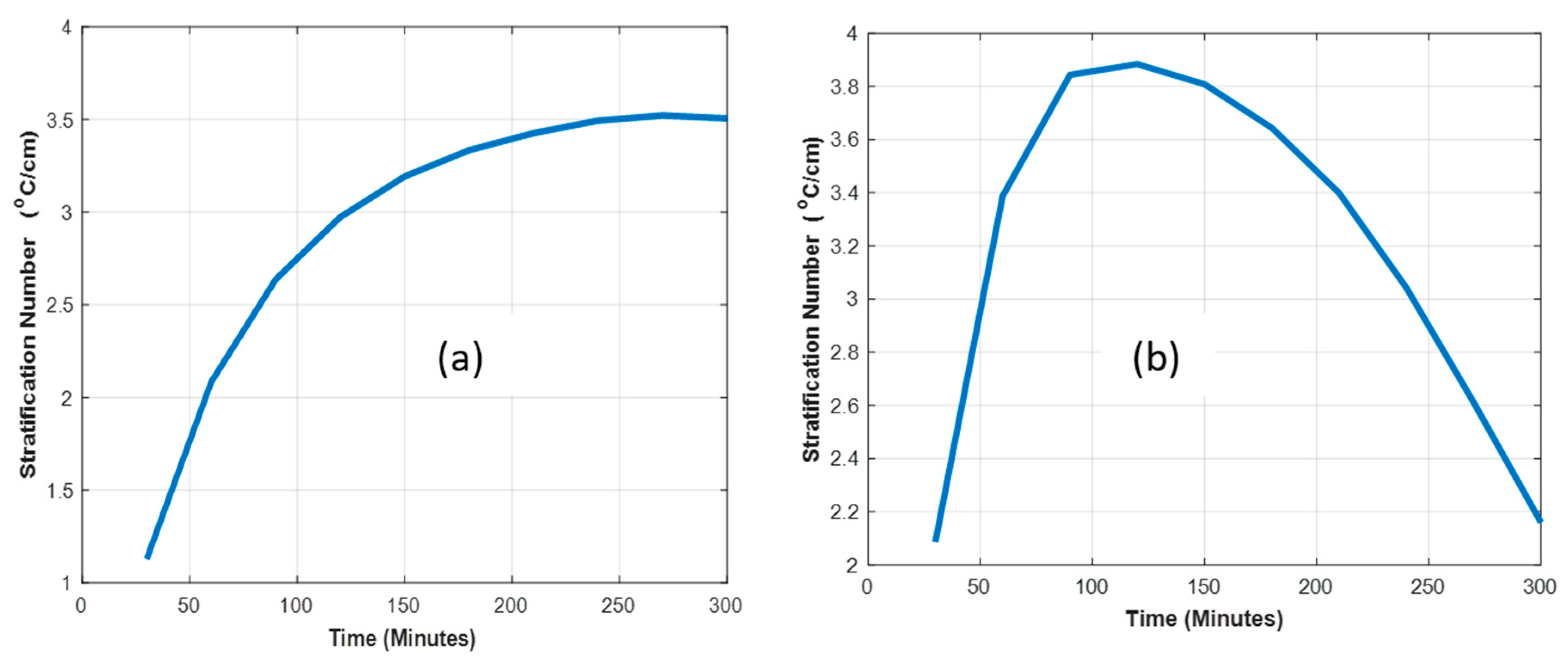

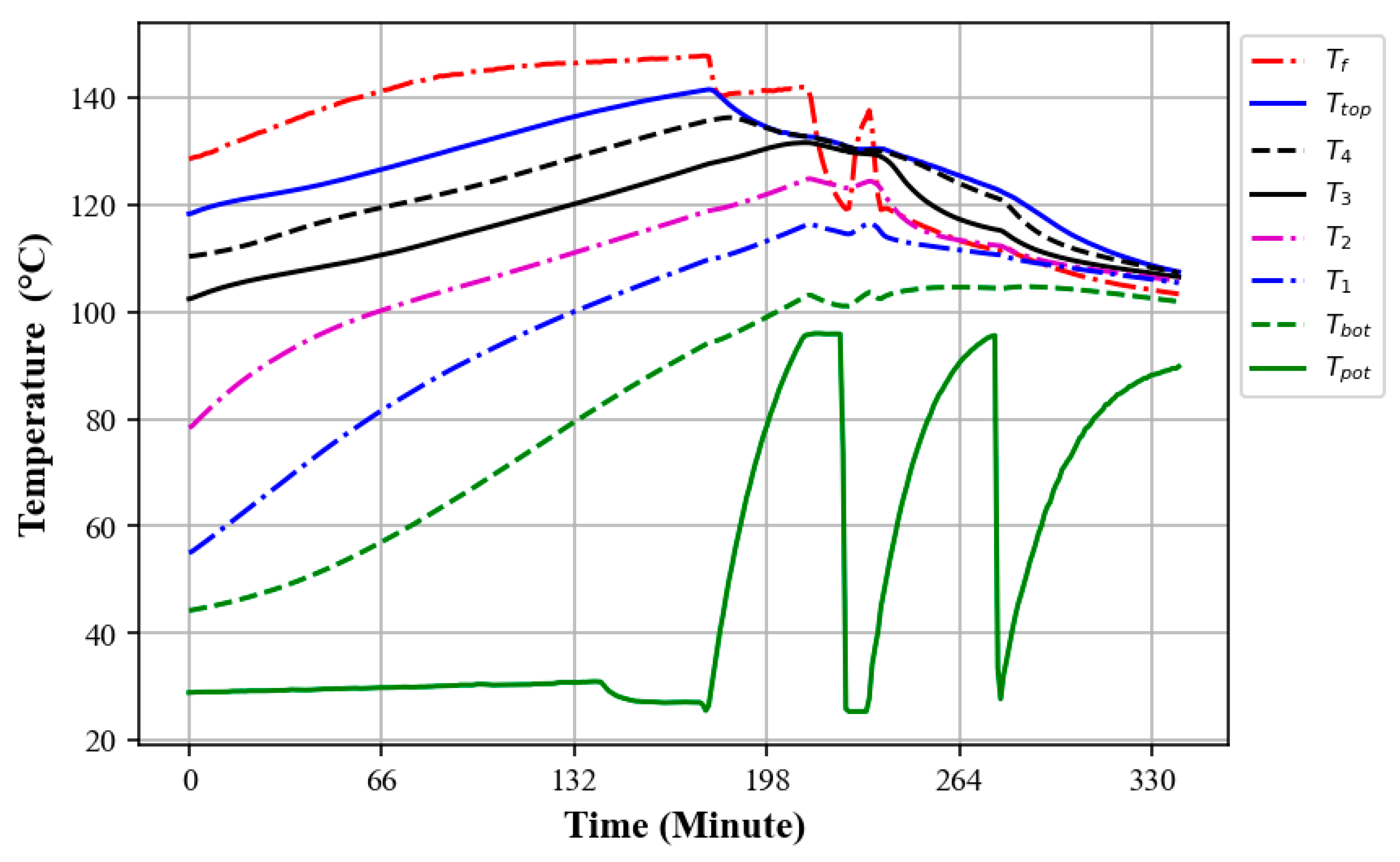

3.1. Temperature Profiles of an Air–Rock Pebble Bed Charged with Different Air Flow Speed

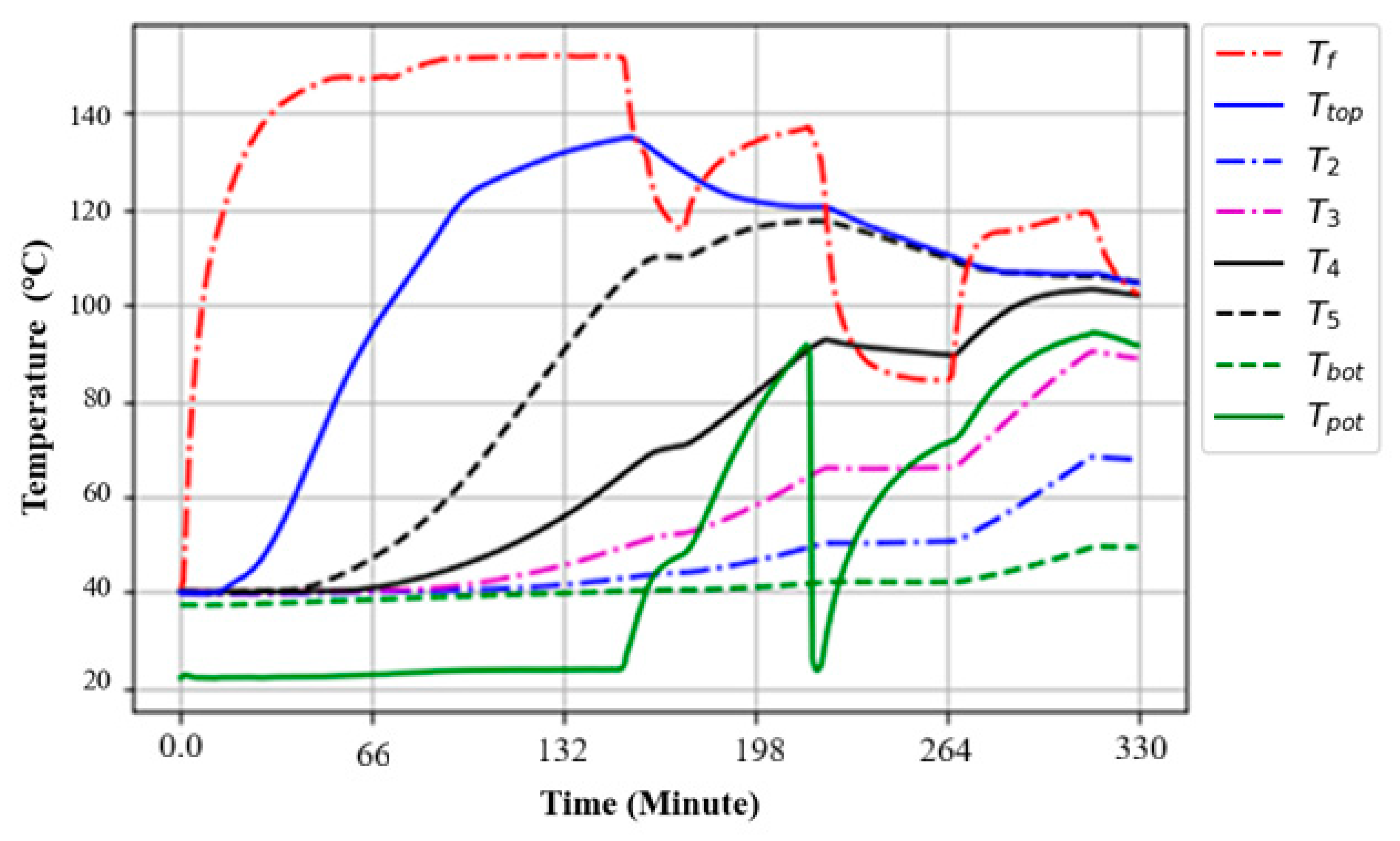

3.2. Temperature Profiles of an Oil-Only TES System During the Charging Process

3.3. Temperature Profiles of an Oil–Rock Pebble TES System During the Charging Process

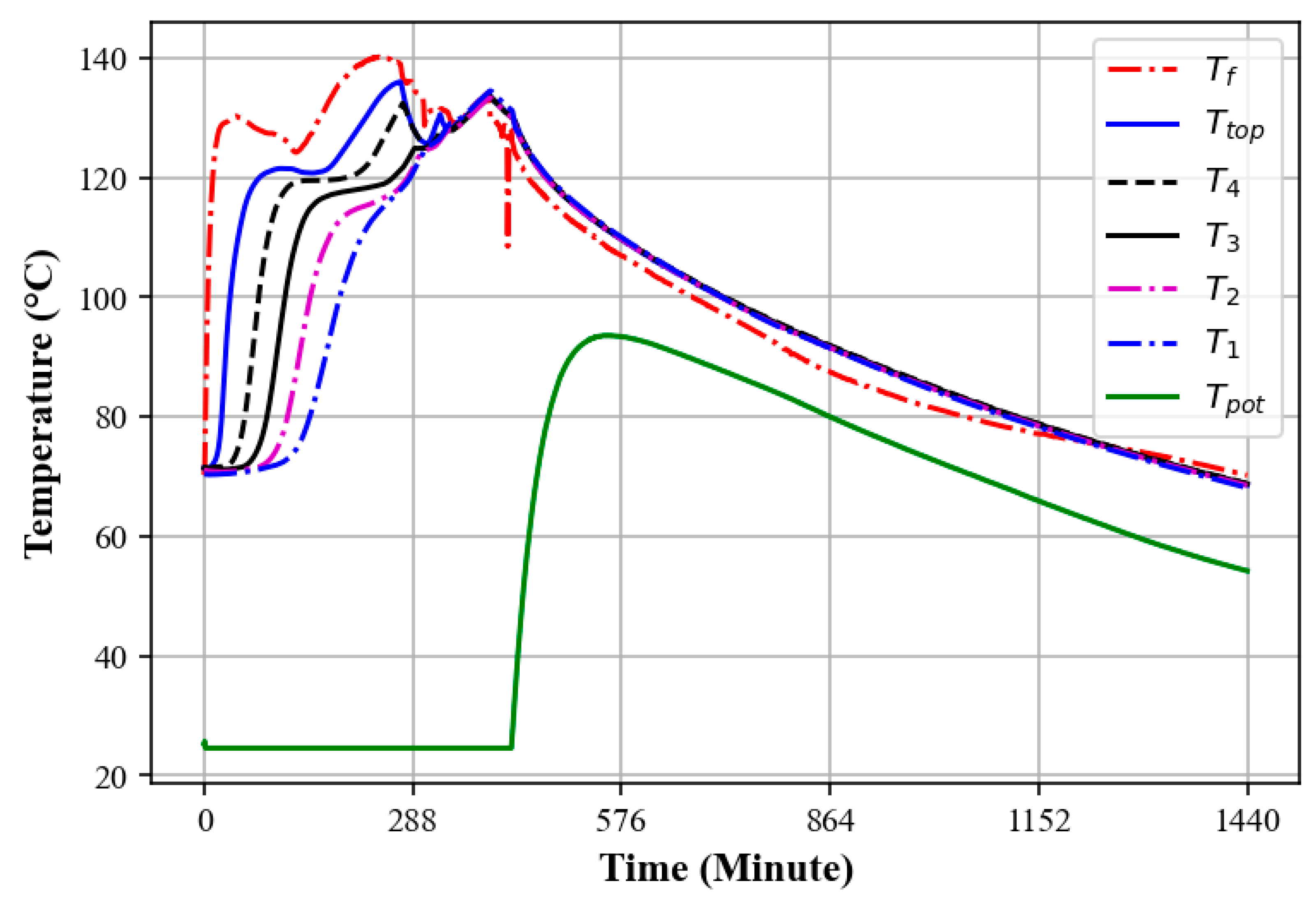

3.4. Charging and Discharging Cycle of the Oil–Rock Bed During Heat Retention

3.5. Thermal Performance of the Oil–Rock Heat Storage and Its Heat Retention

3.5.1. Prolonged Discharge of Heat Storage Through the Water Boiling Test

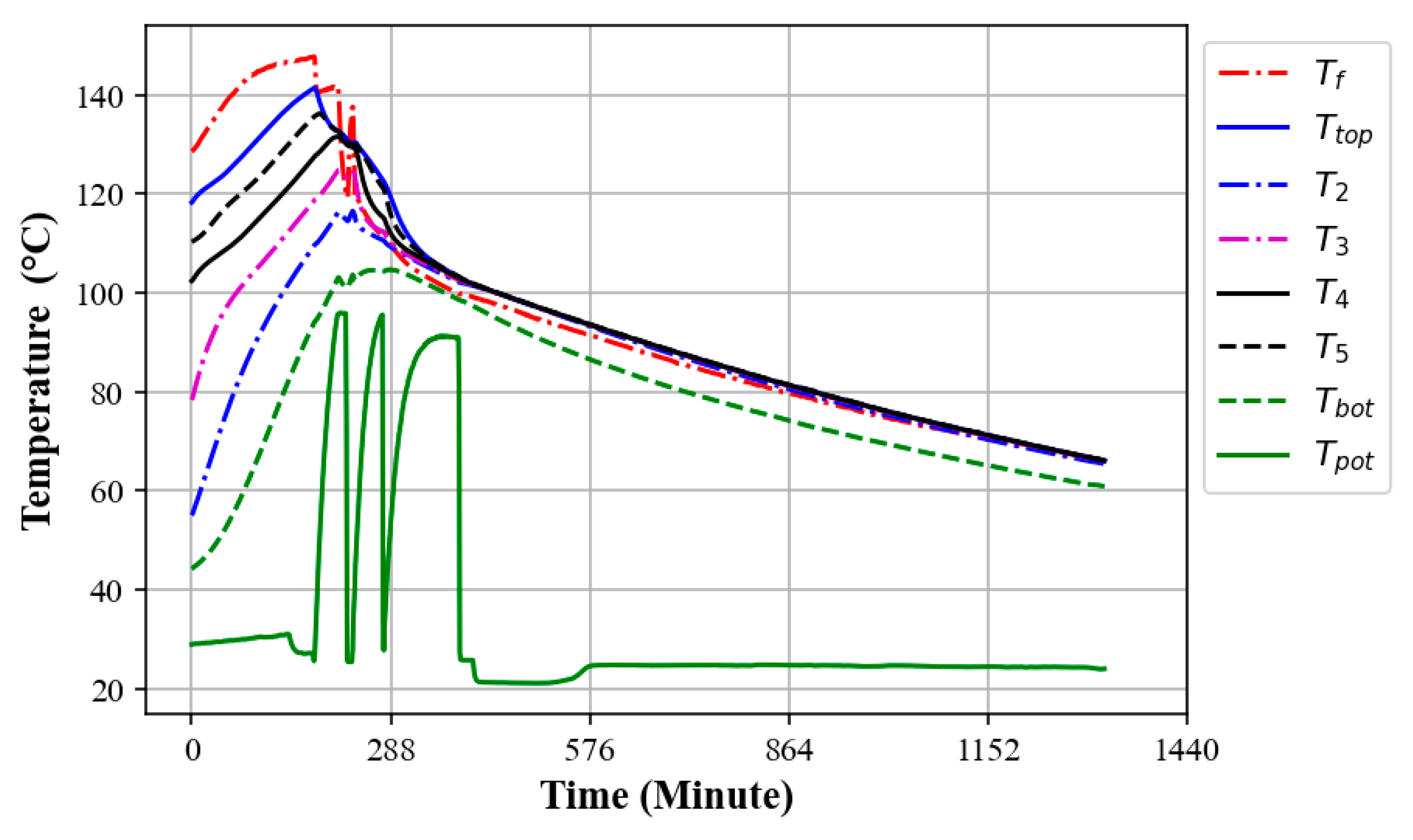

3.5.2. Thermal Discharge of Oil–Rock Bed Heat Storage During Multiple Water Boiling Tests

3.5.3. Thermal Charging While Extracting Heat at the Same Time

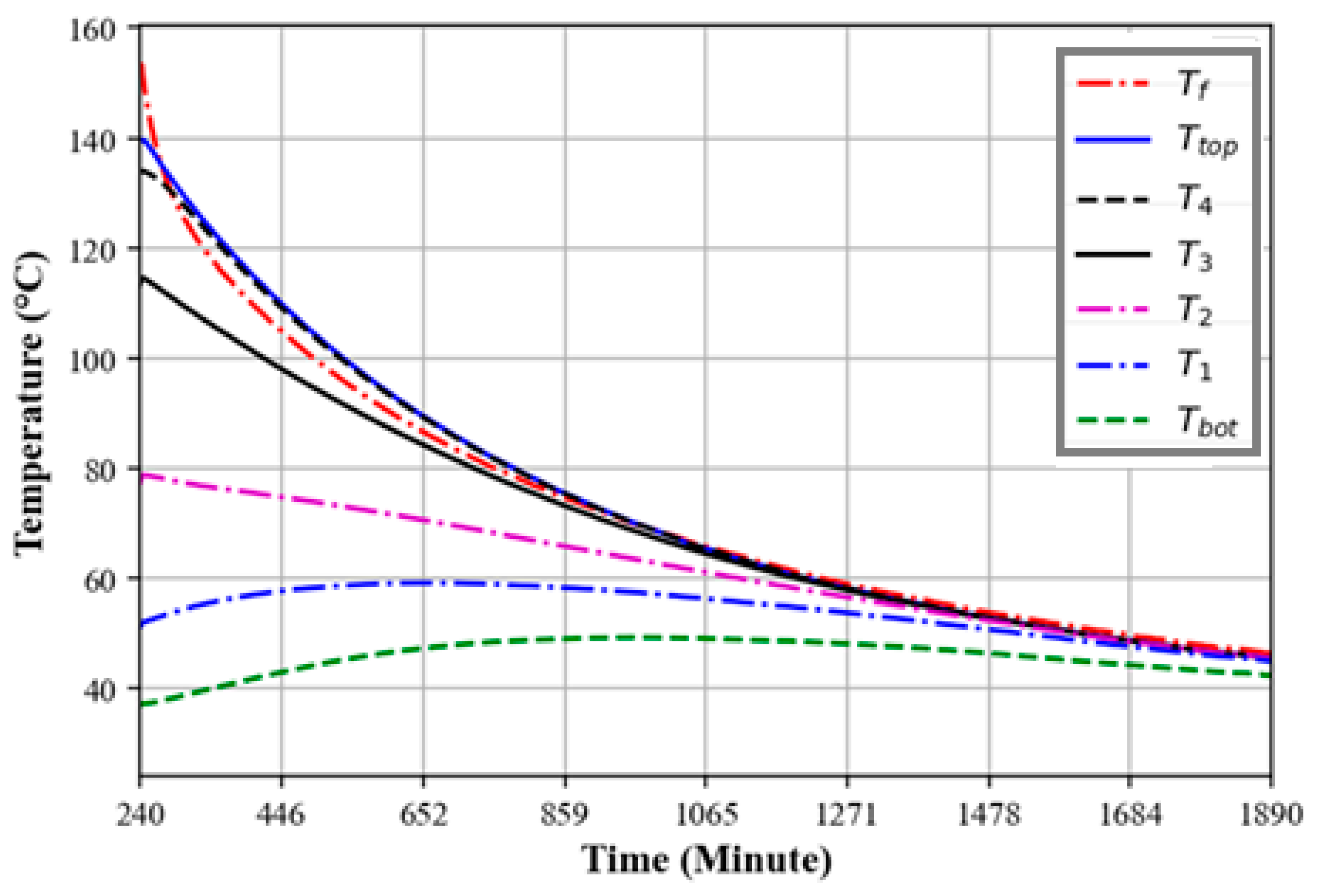

3.6. Heat Retention of the Oil–Rock Bed Heat Storage System

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| SHM | Sensible heat storage material |

| HTF | Heat Transfer Fluid |

| Min | Minutes |

| Symbols | |

| h | hour |

| T | Temperature |

| Temperature of the funnel | |

| Temperature of the water | |

| Temperature at the top | |

| Temperature at the bottom | |

| Initial temperature | |

| Initial temperature | |

| Final temperature | |

| Initial volume of oil | |

| New volume of oil | |

| Volume of water | |

| Void fraction | |

| Total energy stored | |

| Electric power | |

| Specific heat capacity | |

| Density of a substance | |

References

- Energy Institute EI. Statistical Review of World Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Haselip, J. Scaling Up Investment in Climate Technologies Pathways to Realising Technology Development and Transfer in Support of the Paris Agreement Editor. 2021. Available online: https://unepdtu.org/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Bhattacharya, S.C.; Salam, P.A. Low greenhouse gas biomass options for cooking in the developing countries. Biomass Bioenergy 2002, 22, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, J.; Leach, M.; Batchelor, S.; Scott, N.; Brown, E. Battery-supported eCooking: A transformative opportunity for 2.6 billion people who still cook with biomass. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redpath, D.A.G.; McIlveen-Wright, D.; Kattakayam, T.; Hewitt, N.J.; Karlowski, J.; Bardi, U. Battery powered electric vehicles charged via solar photovoltaic arrays developed for light agricultural duties in remote hilly areas in the Southern Mediterranean region. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 2034–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MECS. The State of Access to Modern Energy Cooking Services. 2020. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/937141600195758792/pdf/The-State-of-Access-to-Modern-Energy-Cooking-Services.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Modern Energy Cooking Services MECS. Cooking with Electricity in Uganda: Barriers and Opportunities. 2020. Available online: https://mecs.org.uk/publications/cooking-with-electricity-in-uganda-barriers-and-opportunities/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Gullberg, A.T.; Ohlhorst, D.; Schreurs, M. Towards a low carbon energy future—Renewable energy cooperation between Germany and Norway. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indora, S.; Kandpal, T.C. Institutional cooking with solar energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 84, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Cuce, P.M. A comprehensive review on solar cookers. Appl. Energy 2013, 102, 1399–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Sinha, S. A review of concentrated solar power status and challenges in India. Sol. Compass 2024, 12, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.M.S.; El-Ghetany, H.H.; Nada, S.A. Experimental investigation of novel indirect solar cooker with indoor PCM thermal storage and cooking unit. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, D.; Foong, C.W.; Nydal, O.J.; Banda, E.J.K. An experimental investigation on the combined use of phase change material and rock particles for high temperature (~350 °C) heat storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 79, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawire, A. Performance of Sunflower Oil as a sensible heat storage medium for domestic applications. J. Energy Storage 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, B.; Riba, J.R.; Baquero, G.; Rius, A.; Puig, R. Temperature dependence of density and viscosity of vegetable oils. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 42, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasina, O.O.; Colley, Z. Viscosity and specific heat of vegetable oils as a function of temperature: 35 °C to 180 °C. Int. J. Food Prop. 2008, 11, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.F.; Vaitilingom, G.; Henry, J.-F.; Chirtoc, M.; Olives, R.; Goetz, V.; Py, X. Temperature dependence of thermophysical and rheological properties of seven vegetable oils in view of their use as heat transfer fluids in concentrated solar plants. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 178, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, D.; Polcar, A.; Boldor, D.; Nde, D.B.; Wolak, A.; Kumbár, V. Temperature Dependence of Density and Viscosity of Biobutanol-Gasoline Blends. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawire, A.; Taole, S.H.; Van Den Heetkamp, R.R.J. Experimental investigation on simultaneous charging and discharging of an oil storage tank. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 65, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, T.; Arroyo, P.; Perry, R.; Wang, R.; Arriaga, O.; Fleming, M.; O’Day, C.; Stone, I.; Sekerak, J.; Mast, D. Insulated Solar Electric Cooking—Tomorrow’s healthy affordable stoves? Dev. Eng. 2017, 2, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, S.; Talukder, A.R.; Uddin, R.; Mondal, S.K.; Islam, S.; Redoy, R.K.; Hanlin, R.; Khan, M.R. Solar e-cooking: A proposition for solar home system integrated clean cooking. Energies 2018, 11, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaciga, J.; Nyeinga, K.; Okello, D.; Nydal, O.J. Design and experimental analysis on a single tank energy storage system integrated with a cooking unit using funnel system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 79, 110163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugolole, R.; Mawire, A.; Lentswe, K.A.; Okello, D.; Nyeinga, K. Thermal performance comparison of three sensible heat thermal energy storage systems during charging cycles. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2018, 30, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Description | Value |

|---|---|

| Void fraction (oil–rock system), | 0.42 |

| Volume of oil (±0.5 L) Volume of oil (±0.5 L) | 90 L |

| Total mass of rock in oil–rock bed TES (±0.05 kg), | 65.0 kg |

| Height of rock in oil–rock bed TES (±0.05 cm) | 35.0 cm |

| Density of thermal oil, | 870 kgm−3 |

| Specific heat capacity of oil (±0.5), | 1790 Jkg−1K−1 |

| Height of oil/rock bed heat storage tank (±0.05 cm) | 80.0 cm |

| Height of air/rock bed heat storage tank (±0.05 cm) | 90.0 cm |

| Diameter of oil–rock bed TES unit (±0.05 cm) | 55.0 cm |

| Funnel diameter (±0.05 cm) | 10.0 cm |

| Diameter of wire mesh guarding funnel (±0.05 cm) | 15.0 cm |

| Height of oil above the rock (±0.05 cm) | 30.0 cm |

| Free space above oil level (±0.05 cm) | 15.0 cm |

| Density of air, | 1.2 kgm−3 |

| Specific heat capacity of air (20 °C), | 1006 Jkg−1K−1 |

| Specific heat capacity of rock (±0.5), | 790 Jkg−1K−1 |

| Density of rocks (±0.5 kgm−3), | 2643 kgm−3 |

| Thermal conductivity of rock, | 3.1 Wm−1K−1 |

| Thermal conductivity of oil, | 0.118 Wm−1K−1 |

| Thermal conductivity of air, | 0.026 Wm−1K−1 |

| Diameter cookpot (±0.05 cm) | 31.5 cm |

| Height of cookpot (±0.05 cm) | 20.0 cm |

| Volume of water, | 5–10 L |

| Thermal conductivity of insulating material, | 0.056 Wm−1K−1 |

| Thermal insulation thickness (±0.05 cm) | 10.0 cm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okello, D.; Chaciga, J.; Nydal, O.J.; Nyeinga, K. Experimental Thermal Performance of Air-Based and Oil-Based Energy Storage Systems. Energy Storage Appl. 2025, 2, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/esa2040015

Okello D, Chaciga J, Nydal OJ, Nyeinga K. Experimental Thermal Performance of Air-Based and Oil-Based Energy Storage Systems. Energy Storage and Applications. 2025; 2(4):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/esa2040015

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkello, Denis, Jimmy Chaciga, Ole Jorgen Nydal, and Karidewa Nyeinga. 2025. "Experimental Thermal Performance of Air-Based and Oil-Based Energy Storage Systems" Energy Storage and Applications 2, no. 4: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/esa2040015

APA StyleOkello, D., Chaciga, J., Nydal, O. J., & Nyeinga, K. (2025). Experimental Thermal Performance of Air-Based and Oil-Based Energy Storage Systems. Energy Storage and Applications, 2(4), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/esa2040015