Abstract

Alcohol-associated liver disease, particularly severe alcoholic-associated hepatitis (AH), remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Conventional treatments, including corticosteroids, offer limited short-term benefit and are contraindicated in many patients, necessitating exploration of alternative therapies. Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) has emerged as a novel therapeutic intervention, targeting the gut–liver axis that is disrupted in AH. This review synthesizes the current literature on FMT in the management of alcohol-induced liver injury, examining its pathophysiological basis, clinical efficacy, and implementation challenges. Dysbiosis and increased gut permeability in patients with alcohol use disorder contribute to systemic endotoxemia and hepatic inflammation. FMT aims to restore microbiota diversity and gut barrier integrity, mitigating the progression of liver injury. Some clinical trials have demonstrated encouraging survival benefits and modulation of gut microbiota composition in patients with severe AH. These studies report improved one-year survival rates and reductions in pathogenic bacterial taxa following FMT. However, the field remains nascent, with unresolved questions regarding optimal donor selection, sample preparation, administration routes, and long-term safety. Despite limited large-scale randomized data, FMT shows potential as an adjunct or alternative to existing therapies. Continued research is needed to establish standardized protocols and fully elucidate its role in the treatment algorithm for AH. Given the high mortality associated with untreated severe AH and limitations of current therapies, FMT represents a promising frontier in the management of alcohol-associated liver disease.

1. Introduction

The current standard of care for severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) has several limitations, with only up to one-third of patients being eligible for steroid therapy [1]. Patients with untreated acute AH are reported to have 50–65% 28-day survival [2]. Moreover, corticosteroids carry inherent drawbacks, and for patients who are ineligible for therapy, there are only a limited number of definitive treatment options. Treatment advances have been recently developed, namely Resmetirom, which has recently been approved by the FDA for treatment of metabolic-associated steatohepatitis. However, this medication is currently not approved for the treatment of AH or sequela that follow [3]. This creates a large discrepancy in the available therapy for AH, necessitating further innovation of available therapeutic options.

Despite their initial promise, steroids show limited efficacy in enhancing short-term survival, with no evidence suggesting long-term benefits in AH. The maximum benefit of corticosteroids was seen in patients with MELD scores between 25 and 39 [4]. Additionally, a significant proportion of patients with AH are ineligible to receive steroids [5]. Beyond administration of steroids, pentoxifylline can be considered, though the well-known STOP-AH trial demonstrated no survival benefit with the use of pentoxifylline in AH. In patients who do not improve, early liver transplant can be considered. Although transplantation is often not feasible due to a lack of availability, sepsis, active alcohol consumption, and other logistical barriers, despite available literature suggesting the mortality benefit of early transplantation [6].

AH is closely linked to Alcohol use disorder (AUD) [7]. AUD and alcohol-associated cirrhosis are major causes of morbidity and mortality; thus, understanding the pathogenesis and treatment options is crucial. The gut microbiome is receiving increasing interest from researchers due to its interplay with the immune system [8]. Gut microbiota can be affected by the food we eat, drugs we take, and other aspects of our lifestyle, including alcohol intake [9]. It has been proposed that changes in the gut microbiome due to dysbiosis and disrupted gut barrier function can contribute to alcoholic hepatitis.

AUD is associated with profound alterations in the gut–brain axis, a situation exacerbated by cirrhosis [9]. More specifically, the pathogenesis of AH includes a reduction in gut epithelial tight junction protein expression, mucin production, and antimicrobial peptide levels. This disruption of the gut barrier is a precursor to AH, facilitating the translocation of bacterial products into the bloodstream, a condition known as endotoxemia [10]. Specific metabolites produced by gut bacteria, including short-chain fatty acids, volatile organic compounds, and bile acids, play significant roles in this process [11]. Current efforts aim to reduce the quantitative number of toxic compounds produced by the gut microbiota in the setting of acute AH. Based on this potential treatment pathway, a recent randomized controlled trial by Bajaj et al. compared fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) to placebo in AUD with a primary outcome of 6-month safety [12]. This study indicated that FMT can reduce alcohol cravings, suggesting a mechanism by which FMT reduces further alcohol intake to improve outcomes in AUD patients with AH.

Advancements in genomic sequencing have further elucidated the complexities of the gut microbiome, enabling rapid RNA and DNA sequencing and reducing reliance on cumbersome culture methods. Metagenomics provides invaluable insights into the abundance of specific bacterial species within the gut microbiome, which can aid in developing viable therapeutic strategies. In this article, we aim to summarize the current literature on FMT in relation to AH and explore the pathophysiology of the gut microbiome’s relationship to liver disease, detail the development and logistics of FMT, and elaborate on its role in AH treatment.

2. Search Strategy and Review Methodology

This article is a narrative review designed to synthesize key advances in FMT. To identify relevant studies, we searched the PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for English-language articles published from inception to May 2025 using all possible variations and combinations of the following terms: “fecal microbiota transplantation”, “FMT”, “alcoholic hepatitis”, “alcoholic liver disease”, “alcohol induced liver injury”, “therapy”, and “treatment”.

We included peer-reviewed original studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses that investigated or discussed the use of FMT in alcohol-related liver disease. The exclusion criteria were non-English publications, conference abstracts, and pre-print publications. Exclusion decisions were made based on either the abstract or manuscript. As this was a narrative rather than a systematic review, study selection was guided by relevance to clinical practice and technological development in the subject. Supplementary Figure S1 includes more details on our search strategy.

3. Pathophysiology of the Gut Microbiome in Alcohol Liver Disease

Intestinal bacterial dysbiosis, characterized by an imbalance among various microbial entities in the intestine, disrupts symbiosis. Dysbiosis can manifest in three primary forms: pathobiont expansion, reduced diversity, and loss of beneficial microbes, none of which are mutually exclusive [13]. Both acute and chronic alcohol consumption lead to significant changes in the gut microbiome, particularly an overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria and an overall reduction in microbiome diversity. Alcoholic patients with elevated gut permeability had a lower abundance of the Ruminococcaceae family (Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Subdoligranulum, Oscillibacter, and Anaerofilum), as well as Clostridia, than patients with less gut permeability [11].

Alcohol-derived aldehydes in the intestine produce reactive oxygen species, leading to epithelial damage and dysfunction [13]. This predisposes to bacterial transcytosis and translocation of bacterial products, including endoxins and bacterial DNA, into the bloodstream and ultimately to the liver [14]. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with alcoholic liver disease have significantly elevated serum levels of bacterial products compared to healthy controls [14].

Bacterial overgrowth in alcohol use disorder was first documented over three decades ago [15]. Bacterial cultures of samples from jejunal aspirate displayed significantly higher bacterial counts in alcoholics compared to healthy controls. Breath testing further revealed a higher prevalence of small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth in chronic alcohol users [16]. Subsequent studies have corroborated these findings in alcoholics with cirrhosis [17,18,19].

Despite increasing studies on bacterial overgrowth and dysbiosis, no specific intestinal bacterial pattern has been identified to have an etiological role in the development of AH. However, studies have revealed that subjects with initial altered gut permeability had greater alteration in gut microbiome and fecal metabolites [20]. Notably, alcoholic individuals with high intestinal permeability exhibit elevated phenol levels and reduced 4-methyl-phenol concentrations in feces compared to those with lower permeability. Additionally, concentrations of indole and 3-methyl-indole are diminished in subjects with high gut permeability [21]. Volatile organic compounds were also assessed, revealing caryophyllene (alcohol consumption natural suppressant), camphene (hepatic steatosis attenuator), and propionate and isobutyrate (beneficial short-chain fatty acids) were all decreased in alcoholic patients [21]. Meanwhile, tetradecane (oxidative stress biomarker) was elevated in alcoholics [21]. Experimental studies indicate that proinflammatory, gut-derived bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are essential co-factors in alcohol-induced organ pathologies such as AH, as they translocate from the gut into the bloodstream. This is especially true when gut barrier integrity is compromised by alcohol consumption—triggering systemic inflammation that exacerbates liver injury and promotes disease progression [22,23].

4. Fecal Microbiota Transplant

Historically, fecal coprophagy (the consumption of feces) has been observed across the animal kingdom and is a common practice in veterinary medicine for treating conditions such as ruminal acidosis and chronic diarrhea [24]. FMT offers a potential pathway to restore thousands of bacterial species within the intestinal flora, ultimately reestablishing a healthy gut microbiome [25]. Traditional Chinese medicine has records of using oral fecal microbiota transplant in the treatment of poorly controlled diarrhea. Recently, there has been a resurgence of FMT in managing human diseases, with the United States Food and Drug Administration currently regarding FMT as an investigational new drug for managing difficult-to-treat Clostridium difficile infections [26].

Rigorous screening of donors is critical in the FMT process to ensure the health and safety of recipients. Infectious disease screening includes testing for hepatitis B surface antigens, anti-hepatitis C antibodies, human immunodeficiency viruses 1 and 2, and venereal disease research laboratory testing [26]. The FDA currently regards FMT as an investigational new drug, as such precise infectious screening has not been created [26]. Emory University has performed more than 125 FMT procedures, with a greater than 90% success rate in treating C. difficile-resistant infections through FMT [26]. They have created an FMT protocol recommending that a donor’s stool should test negative for parasitic ova/cysts, Rotavirus antigens, Helicobacter pylori antigens, Cryptosporidium, Isospora (AFB stain), and C. difficile toxins [26]. Additionally, Emory University also ensures donors are not currently using alcohol (ideally >90 days), and do not have altered bowel habits or recent antibiotic usage [26]. An ideal donor is typically a young, healthy, lean individual, preferably a relative who may share compatible human leukocyte antigen alleles. A stool sample should ideally be taken near the facility where it is to be processed. The automated filtration system then separates fibrous products within the stool, leaving a microbiome suspension [26].

5. Donation and Routes of Administration

The timeline from donation to implementation remains a topic of debate. Some studies suggest that frozen samples are as effective as fresh ones; however, concerns persist regarding the viability of certain microbiome components during the freezing and thawing processes, making fresh samples the preferred option [27]. Several high-volume centers report a three-hour window from donation to implantation, thus minimizing concerns about lost viability [28].

The route of administration varies, including oral, nasogastric, rectal, or endoscopic methods, depending on the disease presentation and location. There is currently a lack of studies in the literature comparing the efficacy of different administration routes and their outcomes for severe alcoholic hepatitis or chronic conditions such as alcohol induced cirrhosis. Additionally, patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis may not be suitable candidates for endoscopic delivery due to anesthesia, bowel prep, or additional clinical factors.

6. Current Knowledge of Fecal Microbiota Transplant in Alcoholic Liver Disease

Patients with untreated severe AH face a grim 50–65% survival rate at 28 days [29]. Gut dysbiosis is believed to play a role in the development and progression of alcoholic liver disease. This process is thought to occur through changes in the microbiome that lead to increased production of volatile organic compounds [30]. Additionally, increased gut permeability results in these biochemical products entering portal circulation, causing the activation of both innate and adaptive immune responses and resulting in hepatic injury [30]. Although the precise methods for gut modulation, as well as the optimal site, duration, and technique, remain unclear, ongoing clinical trials are exploring a broad range of therapeutic options for both severe AH and chronic conditions such as hepatic encephalopathy, hepatitis B-related liver disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

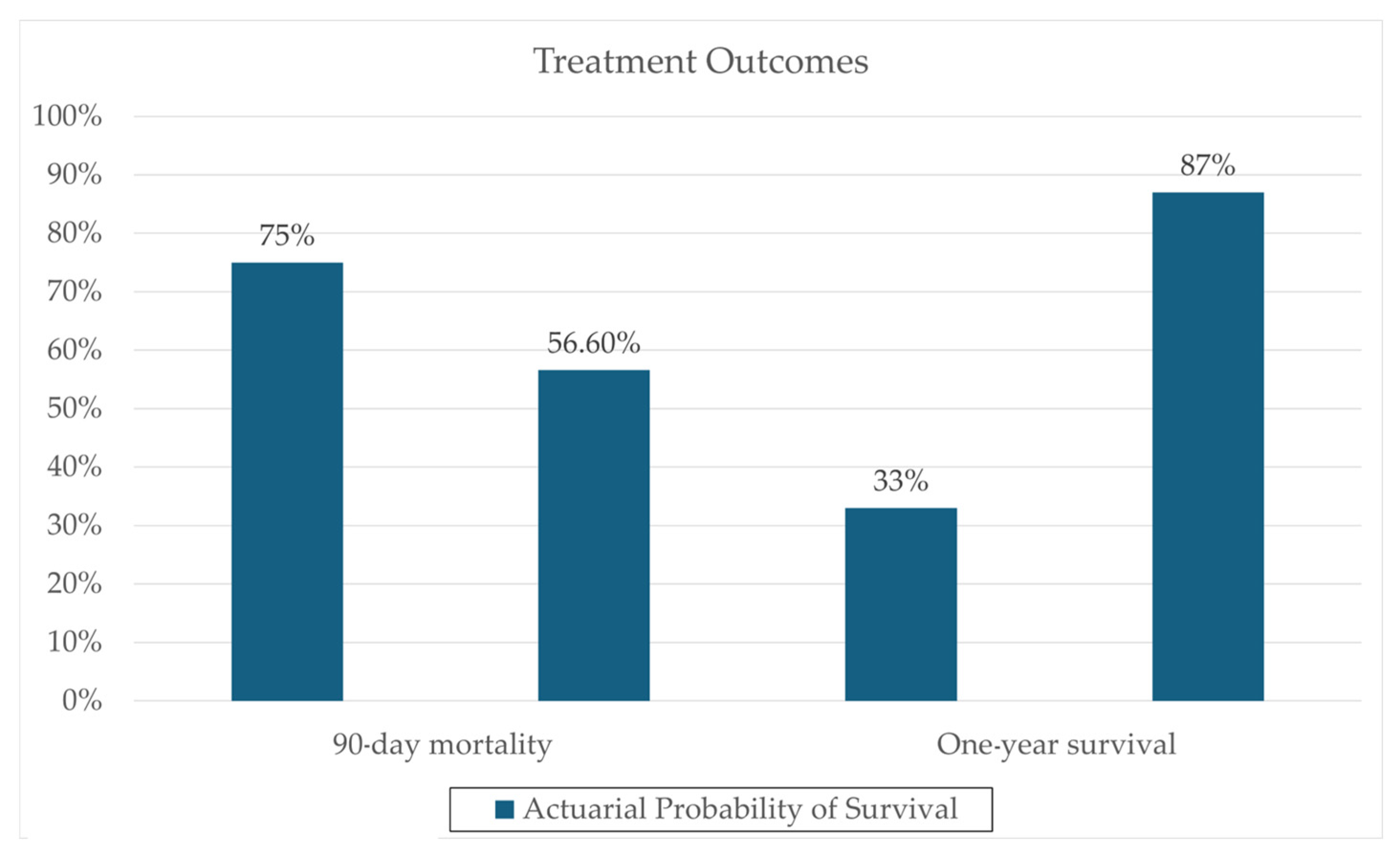

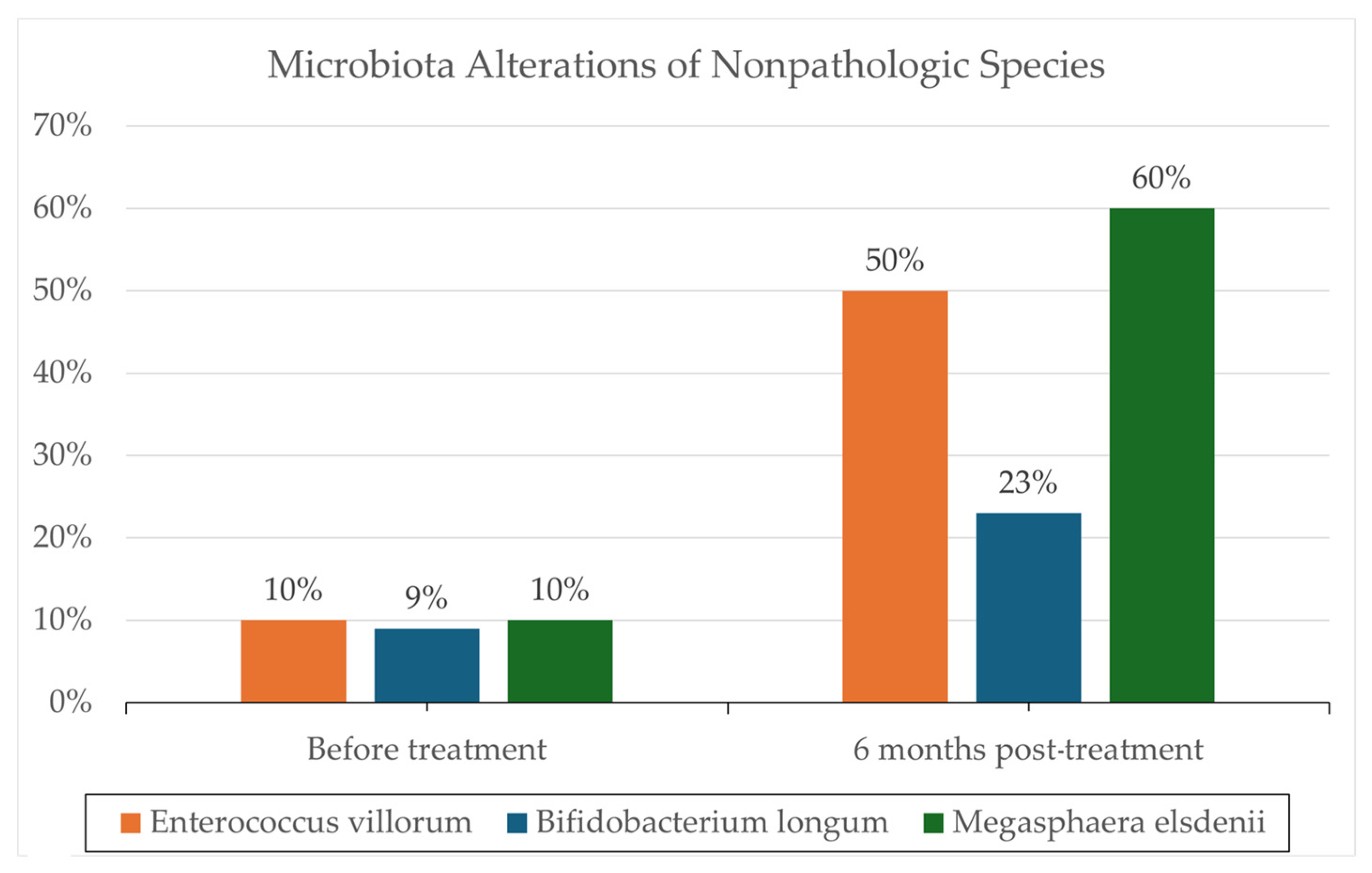

One notable trial involving patients with severe AH (8 in FMT, 18 in control group) conducted by Philips et al. administered FMT consecutively for seven days in steroid-ineligible patients, revealing a significant one-year survival improvement (87% in the FMT group versus 33.3% in the control group; p = 0.018) [28]. These results can be seen in Figure 1. Remarkably, 6–12 months post-administration, co-existence of donor and recipient microbiota was still evident, supporting the hypothesis that donor samples can modulate recipient microbiota, potentially reducing the pathogenicity of overrepresented microbes through a more balanced microbiota. Additionally, changes in the relative abundance of certain pathogenic species, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (10% to <1% at 1 year), were reported. Also, changes in the relative abundance of nonpathogenic species, such as Enterococcus villorum (9–23% at 6 months), Bifidobacterium longum (6–50% at 6 months), and Megasphaera elsdenii (10–60% at 1 year), were reported; the results are shown in Figure 2. Excessive flatulence was a complaint of 50% of patients with FMT [28]. The current literature lacks trials addressing significant adverse effects in FMT recipients.

Figure 1.

Clinical outcome data, comparing actuarial probability of survival in FMT and Steroid groups. Data derived from a prospective cohort (N = 195) reported by Philips et al. 2017 [28].

Figure 2.

Microbiota analysis utilizing standard protocols for DNA isolation and microbial community analysis. Reported are the changes in the relative abundance of specific microbes before and following FMT. Microbiota alteration results are reported from a prospective cohort (N = 195) reported by Philips et al. 2017 [28].

Philips et al. further explored FMT in severe AH in their 2018 retrospective study comparing corticosteroids, nutrition, pentoxifylline, and FMT in patients with severe AH [31]. 51 patients were included with 8, 17, 10, and 16 patients in the corticosteroids, nutrition, pentoxifylline, and FMT groups, respectively. Patients in the corticosteroid group were treated with oral prednisolone at a daily dose of 40 mg for 7 days, extended up to 28 days if they showed an adequate response, with only corticosteroid responders included in the final analysis. Patients receiving nutritional therapy were started and maintained on a diet providing 1.5 g of protein and 40 kcal per kilogram of body weight, along with supplements including a vitamin B-complex and zinc. Patients in the pentoxifylline group received oral pentoxifylline at 400 mg thrice daily after meals for 1 month. Patients in the FMT group received treatment per the protocol developed in the Philips et al. 2017 study [28]. The proportion of patients surviving at the end of 1 month in the CS, nutrition, pentoxifylline, and FMT groups were 63.0%, 47.0%, 40.0%, and 75.0%, respectively, while the proportion of patients surviving at the end of 3 months were 38.0%, 29.0%, 30.0%, and 75.0%, respectively.

Most recently in 2022, Philips et al. conducted a retrospective study involving 47 SAH patients who underwent FMT for 7 days compared with 25 matched patients receiving pentoxifylline [32]. Patients receiving FMT had a significantly higher 6-month survival rate compared with those treated with pentoxifylline (83.0% vs. 56.0%, p = 0.012). By the conclusion of the 6-month follow-up, patients in the pentoxifylline group exhibited significantly higher incidences of clinically significant ascites (56.0% vs. 25.5%, p = 0.011), hepatic encephalopathy (40.0% vs. 10.6%, p = 0.003), and serious infections (52.0% vs. 14.9%, p < 0.001) compared to patients in the FMT group. At the 3-month follow-up, biomarker analysis revealed a higher prevalence of Bifidobacterium in the FMT group, whereas Eggerthella was more abundant in the pentoxifylline group. By 6 months, Bifidobacterium continued to be prominent in the FMT group, while pathogenic Aerococcaceae was more evident in the pentoxifylline group. Network analysis further identified Bifidobacterium as a key beneficial microbe influencing patient outcomes in the FMT-treated cohort.

A prospective study by Sharma et al. in 2022 also demonstrated the safety and efficacy of FMT in severe AH [33]. The investigators enrolled patients aged 18–60 years with a clinical diagnosis of severe AH, a modified Maddrey’s discriminant function ≥ 32, and meeting criteria for acute-on-chronic liver failure. In total, 33 patients were included, with 13 in the FMT group and 20 in the standard treatment group. In this study, stool donors were recruited from healthy close family members aged 18–60 years who underwent extensive testing to exclude those with acute or chronic infections. The main findings of the study were that survival was significantly better in the FMT group at both 28 days (100.0% versus 60.0%, p = 0.01) and 90 days (53.8% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.02). Secondary findings were that ascites resolved in 100.0% versus 40.0% of survivors (p = 0.04). Hepatic encephalopathy resolved in 100.0% versus 57.1% of patients (p = 0.11). Major adverse event rates were similar between groups and included spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (p = 0.77) and gastrointestinal bleeding (p = 0.70).

More recently, a randomized controlled trial published by Pande et al. in 2022 compared 90-day mortality in steroid-eligible severe AH patients [34]. In this study, individuals were divided into a prednisolone 40 mg/day for 28 days group (n = 60) and a healthy-donor-FMT group (n = 60), where patients received FMT via naso-duodenal tube (7-day treatment duration). Results showed that 90-day survival was achieved by 56.6% (34/60) of patients in the prednisolone group and 75.0% (45/60) in the FMT group (p = 0.044). Specifically, a reduction in pathogenic taxa was observed, including a decline in Campylobacter species and anaerobes such as Parcubacteria, Weissella, and Leuconostocaceae. Conversely, there was a significant increase in the abundance of Alphaproteobacteria (approximately sevenfold, p = 0.047) and Thaumarchaeota (a known ammonia oxidizer, p = 0.06) [34]. These findings suggest that FMT not only improves short-term mortality rates but also shows promise for enhancing outcomes at 1 year post-treatment.

A meta-analysis published by Pakuwal and colleagues included eight studies and showed that FMT improved survival from AH at both 28 days and 90 days (RR 2.3 and 2.5, respectively, p < 0.01) [35]. The difference in mortality at 6 months and 12 months was not significant (p = 0.10, 0.22). No adverse events were recorded across the 218 patients included in the FMT group. It is interesting to note that statistically significant findings were found only in the retrospective trials included. Table 1 shows a summary of the primary studies discussed. A comprehensive review of the literature indicates that FMT has the potential to improve survival rates in patients with severe AH. Given these findings, we propose that with further validation of its efficacy, FMT could emerge as a viable therapeutic option not only for steroid-ineligible severe AH patients but also for those who are steroid-eligible.

Table 1.

Summary of studies.

Although no safety concerns were noted in the above studies, there are significant safety concerns with FMT, notably the transmission of infectious diseases. Most short-term risks relate to the administration method (endoscopic procedures) rather than to FMT itself. The most common adverse effects are mild and self-limiting, including transient diarrhea, abdominal pain or cramps, bloating, flatulence, and constipation [36]. Many potential risks are mitigated by careful donor selection and screening. This includes obtaining a detailed medical history and testing for a broad panel of infectious diseases. In some programs, this process rejects up to 97% of volunteers [36]. Many centers operate a Universal Stool Bank model, distributing pre-screened, frozen FMT preparations [36]. This model reduces costs through economies of scale and enhances safety via standardized processes, traceability, and ongoing monitoring.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

While promising, the current state of FMT for AH remains experimental. Overall, the quality of data is limited by being mostly observational data. The sample sizes in each individual study also tended to be low, although the most recent randomized controlled trial included the largest number of patients, with 60 in each study arm. This was a key limitation of the Pakuwal et al. meta-analysis, which affected the confidence in the numerical results of the study [35].

The bulk of data were from India, a nation with a distinct genetic and cultural heritage affecting baseline risks, diet, and environment. This limits the external validity of the current evidence, as populations from other areas have distinct genetic and environmental factors. Heterogeneity in the FMT regimens also needs to be considered when appraising the evidence on FMT therapy. The various investigator groups referenced in this review had their own donor selection protocol and methods for formulating their FMT therapies. There is not enough data to perform robust modulator analyses such as meta-regression to assess method-specific effects.

In the West, efforts have been made to standardize methods and develop capsule formulations rather than rely on donor samples collected via colonoscopy or nasojejunal tube [37]. In the United States, OpenBiome previously provided screened and filtered stools for use in fecal microbiota transplantation FMT therapies; however, recent policy changes have limited the availability [38]. Purified single-culture therapies such as SER-109 (VOWST) are available for C. difficile infections; however, they have not yet been studied in alcoholic liver disease [39]. Further studies can explore the efficacy of single-culture therapies in this patient population.

8. Conclusions

This literature review suggests that FMT may be a safe and viable therapeutic option for acute AH. The clinical trials cited herein report improved mortality outcomes associated with FMT, with follow-up assessments ranging from 28 days to one year after transplantation. Moreover, FMT may contribute to a sustained reduction in hepatic injury by restoring a healthy intestinal microbiota.

Given the limited cohort size and single-center design of the aforementioned studies, further investigation remains critical. The current reliance on steroids as the primary treatment for AH necessitates a reevaluation of therapeutic strategies. FMT presents a promising alternative that warrants further exploration to fully understand its potential benefits in the management of severe AH.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/therapeutics3010002/s1, Figure S1. Search Strategy Flow Diagram.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., Y.W. and E.R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., Y.W., K.M. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, E.R.S., E.Y., T.J.E. and R.S.; visualization, A.G. and E.Y.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the clinical and academic faculty of Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Round Rock.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AH | Alcoholic hepatitis |

| AUD | Alcohol use disorder |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplant |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

References

- Singeap, A.-M.; Minea, H.; Petrea, O.; Robea, M.-A.; Balmuș, I.-M.; Duta, R.; Ilie, O.-D.; Cimpoesu, C.D.; Stanciu, C.; Trifan, A. Real-world utilization of corticosteroids in severe alcoholic hepatitis: Eligibility, response, and outcomes. Medicina 2024, 60, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.; Bataller, R. Alcoholic hepatitis: Prognosis and treatment. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 37, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogieuhi, I.J.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Adeniran, O.; Awosan, W.; Kwentoh, I.; Samuel, O.; Ajimotokan, O.I.; Victoria, O.O.; Moradeyo, A.; et al. Resmetirom in the management of metabolic associated steatohepatitis (MASH): A review of efficacy and safety data from clinical trials. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 37, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, J.P.; Díaz, L.A.; Baeza, N.; Idalsoaga, F.; Fuentes-López, E.; Arnold, J.; A Ramírez, C.; Morales-Arraez, D.; Ventura-Cots, M.; Alvarado-Tapias, E.; et al. Identification of optimal therapeutic window for steroid use in severe alcohol-associated hepatitis: A worldwide study. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crabb, D.W.; Im, G.Y.; Szabo, G.; Mellinger, J.L.; Lucey, M.R. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020, 71, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathurin, P.; Moreno, C.; Samuel, D.; Dumortier, J.; Salleron, J.; Durand, F.; Castel, H.; Duhamel, A.; Pageaux, G.-P.; Leroy, V.; et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1790–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, C.A. A comprehensive review of diagnosis and management of alcohol-associated hepatitis. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasthry, S.M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in alcohol related liver diseases. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2020, 26, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, M.R.; Mathurin, P.; Morgan, T.R. Alcoholic Hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2758–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassard, A.-M.; Ciocan, D. Microbiota, a key player in alcoholic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2018, 24, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Gavis, E.A.; Fagan, A.; Wade, J.B.; Thacker, L.R.; Fuchs, M.; Patel, S.; Davis, B.; Meador, J.; Puri, P.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplant for alcohol use disorder. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; McClain, C.J.; Feng, W. Microbiome dysbiosis and alcoholic liver disease. Liver Res. 2019, 3, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlesak, A.; Schäfer, C.; Schütz, T.; Bode, J.C.; Bode, C. Increased intestinal permeability to macromolecules and endotoxemia in patients with chronic alcohol abuse in different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, J.C.; Bode, C.; Heidelbach, R.; Dürr, H.K.; A Martini, G. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Hepatogastroenterology 1984, 31, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, C.; Kolepke, R.; Schäfer, K.; Bode, J.C. Breath hydrogen excretion in patients with alcoholic liver disease—Evidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Z. Gastroenterol. 1993, 31, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Morencos, F.C.; Castaño, G.d.L.H.; Ramos, L.M.; López Arias, M.J.; Ledesma, F.; Romero, F.P. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996, 41, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirpich, I.A.; Solovieva, N.V.; Leikhter, S.N.; Shidakova, N.A.; Lebedeva, O.V.; Sidorov, P.I.; Bazhukova, T.A.; Soloviev, A.G.; Barve, S.S.; McClain, C.J.; et al. Probiotics restore bowel flora and improve liver enzymes in human alcohol-induced liver injury: A pilot study. Alcohol 2008, 42, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhonchal, S.; Nain, C.K.; Taneja, N.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Sinha, S.K.; Singh, K. Modification of small bowel microflora in chronic alcoholics with alcoholic liver disease. Trop. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Dig. Dis. Found. 2007, 28, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, S.; Matamoros, S.; Cani, P.D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Jamar, F.; Stärkel, P.; Windey, K.; Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F.; Verbeke, K.; et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4485–E4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, R.D.; Dailey, A.; Zaidi, F.; Navarro, K.; Forsyth, C.B.; Mutlu, E.; A Engen, P.; Keshavarzian, A. Alcohol induced alterations to the human fecal VOC metabolome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigatello, L.; Broitman, S.; Fattori, L.; Dipaoli, M.; Pontello, M.; Bevilacqua, G.; Nespoli, A. Endotoxemia, encephalopathy, and mortality in cirrhotic-patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1987, 82, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, C.B.; Farhadi, A.; Jakate, S.M.; Tang, Y.; Shaikh, M.; Keshavarzian, A. Lactobacillus GG treatment ameliorates alcohol-induced intestinal oxidative stress, gut leakiness, and liver injury in a rat model of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol 2009, 43, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePeters, E.; George, L. Rumen transfaunation. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 162, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauxe, W.M.; Dhere, T.; Ward, A.; Racsa, L.D.; Varkey, J.B.; Kraft, C.S. Fecal microbiota transplant protocol for clostridium difficile infection. Lab. Med. 2015, 46, e19–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Yin, W.; Liu, W. Is frozen fecal microbiota transplantation as effective as fresh fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection: A meta-analysis? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 88, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, C.A.; Pande, A.; Shasthry, S.M.; Jamwal, K.D.; Khillan, V.; Chandel, S.S.; Kumar, G.; Sharma, M.K.; Maiwall, R.; Jindal, A.; et al. Healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation in steroid-ineligible severe alcoholic hepatitis: A Pilot Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 600–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, F.; Guo, J.; Shi, D.; Fang, D.; Li, L. Dysbiosis of small intestinal microbiota in liver cirrhosis and its association with etiology. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, C.A.; Phadke, N.; Ganesan, K.; Ranade, S.; Augustine, P. Corticosteroids, nutrition, pentoxifylline, or fecal microbiota transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 37, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, C.A.; Ahamed, R.; Rajesh, S.; Singh, S.; Tharakan, A.; Abduljaleel, J.K.; Augustine, P. Clinical outcomes and gut microbiota analysis of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis patients undergoing healthy donor fecal transplant or pentoxifylline therapy: Single-center experience from Kerala. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2022, 10, goac074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Roy, A.; Premkumar, M.; Verma, N.; Duseja, A.; Taneja, S.; Grover, S.; Chopra, M.; Dhiman, R.K. Fecal microbiota transplantation in alcohol-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure: An open-label clinical trial. Hepatol. Int. 2022, 16, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, A.; Sharma, S.; Khillan, V.; Rastogi, A.; Arora, V.; Shasthry, S.M.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; Jagdish, R.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, G.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation compared with prednisolone in severe alcoholic hepatitis patients: A randomized trial. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakuwal, E.; Tan, J.L.; Woodman, R.J.; Page, A.J.; Stringer, A.M.; Chinnaratha, M.A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of fecal microbiome transplantation in patients with severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 37, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Colville, A. Adverse events in faecal microbiota transplant: A review of the literature. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 92, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, N.M.M.; ter Linden, D.; Lilley, A.K.; Royall, P.G.; Tsoka, S.; Bruce, K.D.; Mason, A.J.; Hatton, G.B.; Allen, E.; Goldenberg, S.D.; et al. Design and manufacture of a lyophilised faecal microbiota capsule formulation to GMP standards. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, H.L.; DuPont, A.W.; Tillotson, G.S. Microbiota restoration therapies for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection reach an important new milestone. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2024, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, H.A. SER-109 (VOWST™): A Review in the Prevention of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Drugs 2024, 84, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.