Abstract

Fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke occurs when a driver accidentally leaves a child in a vehicle, leading to death by overheating. Most such accidents are caused by simple cognitive errors. One aspect of these events, described anecdotally, is false memories: the driver has a conscious recollection of removing the child, despite knowing that, tragically, it did not happen. We systematically examined media reports of all cases in the USA over a five-year period, involving 164 separate incidents in which 166 children died. Although for many incidents insufficient information was available, with rigorous criteria, we identified cases that likely involved false memories. Tentatively, we suggest that these appear to be more common when a male child dies, and when more than one child dies, hinting that the severity of psychological trauma is a factor in their emergence. Possible explanations for these false memories are explored, with script/schema theory emerging as a reasonable explanation. This suggests that drivers fill in gaps in their memory for the journey, based on routine journey schemata. An example would be a memory gap filled with a default value of dropping the child at daycare, when in fact, they know they did not. In turn, this schema approach provides a framework for better understanding the reason that drivers sometimes experience cognitive slips, with fatal consequences for child passengers.

1. Introduction

Every year, children, usually babies, succumb to heatstroke after being left in parked vehicles by adults, usually the parents. Fatal heatstroke occurs rapidly because the interior of vehicles can become substantially higher than the ambient temperature within only a few minutes (Grundstein et al., 2010). In addition, the underdeveloped thermoregulatory system of young children, coupled with a high surface area to mass ratio (which causes the body to heat rapidly), renders them very sensitive to catastrophic physiological changes (Adato et al., 2016).

In most countries, figures on incidence are not available. However, there are usually about 28 cases each year in the USA (Hammett et al., 2021). And a study of cases in Italy found an average of one per month (Ferrara et al., 2013). Although in some cases the death is caused by recklessness, in that the driver of the vehicle deliberately left the child in the vehicle, in most cases, there is some form of cognitive error in which the driver becomes unaware that they have left a child in a parked vehicle. Hence, these cases are often dubbed in the media as ‘forgotten baby syndrome’. It is estimated that around 78% of cases of children being left in vehicles are likely due to such cognitive errors (Hammett et al., 2021).

Executive functions appear to be a useful concept in explaining this error. Such cognitive processes are defined in terms of behavior that is goal-directed, intelligent, and that draws on limited processing resources (Pluck et al., 2023). This latter aspect is important, as several authors have suggested that overload of an executive system, such as working memory, is the cause of children being forgotten in vehicles. It is argued that stress, multitasking, etc., place an extra burden on limited executive resources, leading to failures to recall important parts of a plan (Ferrara et al., 2013; Anselmi et al., 2020; Breitfeld, 2020). The neglected parts could be things such as dropping a child off at daycare before proceeding to one’s place of work.

Other theories have suggested that learning systems in the brain are equally implicated. Diamond (2016, 2019) have proposed the most detailed cognitive and neurological theory of why people sometimes make simple cognitive slips, leading to children being accidentally left in parked vehicles. He draws on theories of brain function that propose an antagonistic relationship between the cortico-hippocampal systems involved in deliberate declarative memory and a subcortical procedural memory system (e.g., Poldrack & Packard, 2003; Pluck et al., 2019). He argues that a plan to remove a child from a vehicle is essentially executive control, set by cortical systems, and is to be triggered by activity in the hippocampus. That hippocampal system is used to recall that there is a child in the vehicle. However, Diamond argues that a basal-ganglia system that has learnt stimulus-response habits allows the driver to go into ‘autopilot’, a system that also suppresses the hippocampal reminding system. Although they are attempting to work together, the inhibition can lead to prospective memory failure, i.e., forgetting about the part of the plan involving the child.

Such an explanation is attractive. It is broadly consistent with neuroscience of learning and decision making that posits a basal-ganglia-based habit-learning system (Tricomi et al., 2009) and a relatively separate frontal lobe system for conscious goal-directed decisions (Valentin et al., 2007). Simple stimulus-response learning allows the automaticity of the behavior controlled by habits (Devan et al., 2011). However, these simple stimulus-response connections can be chained together to allow seemingly complex, but stereotypical actions, such as driving a familiar, routine journey (Robbins & Costa, 2017). Such journeys on ‘autopilot’ often result in people driving to places that they did not actually plan to drive to. These mistakes, known as capture errors, have been detailed by Reason (1984, 1990). This mirrors, in many ways, the circumstances of several incidents of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke. In such cases, drivers have described taking a routine journey, often to their workplace, instead of the originally planned journey, which involved dropping a child en route, such as at daycare.

Nevertheless, there is one other cognitive aspect to the phenomenon that is not clearly explained. Several reports mention that false memories are common. That is, the drivers apparently claim afterwards that they have memories of dropping off the child or removing them from the vehicle, despite the objective facts that they did not. Such false memories would not be predicted from the cognitive-learning-based models that suggest the error is caused by a stimulus-response-based habit system controlling behavior, leading to a failure to trigger prospective memory. Take, as an example, a person who decides to stop at a store on the drive home from work. That would be a prospective plan to interrupt a well-practiced, habitual drive. Now, let us further suppose that they arrive home and realize that they forgot to stop at the store. We would not expect that person to develop a false memory of having stopped at the store. In fact, they would most likely report that they simply forgot to stop (what cognitive psychologists would call a prospective memory failure). We can see from this hypothetical scenario that a prospective memory failure due to habit does not require, or even imply, that a false memory would be formed.

Nevertheless, several commentators discussing the legal aspects of pediatric vehicular heatstroke incidents (Kaltwang et al., 2024; Breitfeld, 2020; Murphy, 2020; Washabaugh, 2020) have suggested that false memories may occur. Diamond (2016, 2019) go much further, suggesting that false memories are a universal phenomenon of such events. However, this observation is not supported by data and appears to be his impression of working as an expert witness on several cases. In fact, all the mentions of false memories in the context of pediatric vehicular heatstroke in the peer-reviewed literature appear to be rather anecdotal.

Are such reports credible? Although the creation of false memories in the laboratory has been demonstrated many times, this generally involves a quite simple fact that the research participant has no reason to doubt, such as there was broken glass visible in a car crash observed previously (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). Even in seemingly naturally occurring false memories that have been documented, the person involved does believe their own account, for example, that they had been abducted by aliens (Garry et al., 2009). The false memories associated with pediatric vehicular heatstroke are though more extreme, the drivers simultaneously experience a conscious recollection (dropping the child off), and the knowledge that it cannot possibly be true (the child was left in the vehicle).

The existence of such drastic false memories may provide important clues to the mechanism that produces the catastrophic cognitive error behind many cases of pediatric vehicular heatstroke. For example, they may be linked to the automaticity of action control suggested by Diamond (2016, 2019). However, the evidence for their occurrence is currently ambiguous. This is understandable, as, due to the sporadicity of incidents, their legal aspects, and their sensitivity, there is very little research involving primary data. One solution, which has been used by several researchers, is content analysis of news reports (e.g., Guard & Gallagher, 2005; Ferrara et al., 2013; Fatima Siddiqui et al., 2021).

We used this approach, examining all cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke reported in the US media over a five-year period. We aimed to identify cases that involved false memories and to examine factors that might be associated with them, such as the routine of the route taken. To pre-empt the results, we confirm that false memories do seem to occur, and we identify some of the factors associated with possible false memories in cases where children have died in parked vehicles. We further show that false memories are consistent with the idea of cognitive schemata, particularly a classical theory from cognitive science- script theory (Schank & Abelson, 1977; Abelson, 1981). We argue that this may be a useful alternative approach to understanding the cognitive errors leading to fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

This study involved a content analysis of media reports describing cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke. Specifically, cases in which there was evidence that a cognitive error had been an important contributing factor, and that first-person verbal accounts were available that could potentially reveal false memories. For each case analyzed, multiple news reports were accessed, mainly on news websites, but also involving television news clips (e.g., on YouTube).

2.2. Information Recorded

All cases were studied to identify and record various aspects of the case, particularly evidence of false memories of removing the child from the vehicle. The presence or absence of false memories was scored on a four-point scale:

- 0.

- Unlikely to involve false memory: parent/driver acknowledges error was made and makes no reference to false memory; for example, saying that they just forgot.

- 1.

- Possible false memory: parent/driver makes statements suggestive of false memory, such as ‘I thought I had’, or ‘I assumed I had’.

- 2.

- Probable false memory: between suggestive and expressing actual memory. For example, ‘I was so sure that I had taken them from the car’ or ‘I did, I brought the baby in’.

- 3.

- False memory: Expresses an explicit memory that they actually did remove the child, despite knowing now that it did not happen. For example, saying ‘I remember taking them out of the car’.

We additionally scored the routine of the journey made on a five-point scale, ranging from a highly routine trip, taken at the usual time, to the same locations, to a completely non-routine trip, such as an emergency journey. The number of stops in the planned journey was counted, but in cases where a vague number was stated (e.g., ‘multiple stops’), ‘4’ was recorded. Other details of the incidents we recorded include: age of the child involved, number of children in the vehicle, number of fatalities, age of the driver, etc.

As the cases varied, not only in incident context but also in quantity and quality of reporting, we graded the available evidence for each incident on a three-point scale. That scale ranged from low-quality (i.e., only brief, journalistic, repetitive reporting) through medium quality (i.e., including comments from police officers, more extensive reporting) to high-quality (i.e., including information from formal processes, enquiries, court cases etc.).

2.3. Cases Included

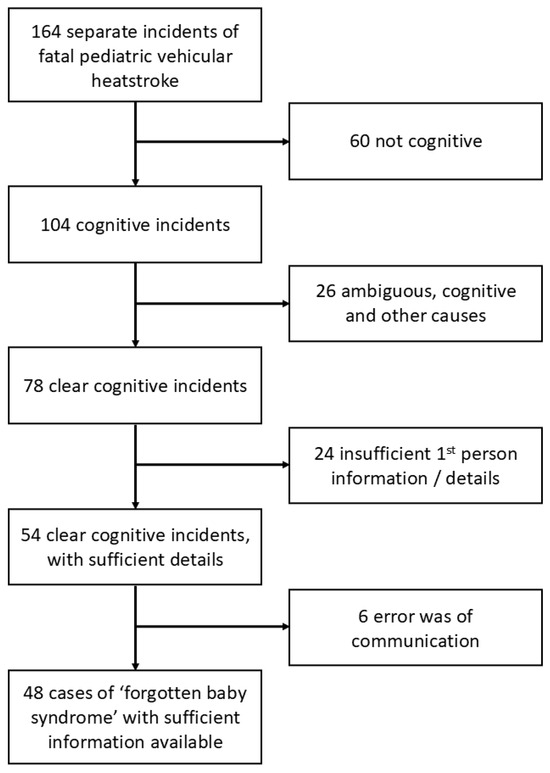

We examined all cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke over a five-year period in the USA (2019–2023), as listed on two public websites, Kids and Car Safety (https://www.kidsandcars.org/ accessed on 20 January 2024) and No Heat Stroke (https://www.noheatstroke.org accessed on 20 January 2024). We also conducted additional searches to check for any cases not listed on either site but reported in the media. This resulted in over 300 news reports being analyzed. In total, 164 incidents were identified and examined, involving 166 child fatalities. However, 60 incidents did not appear to involve a cognitive error by the driver; in these incidents, the driver deliberately left children within the vehicle, or children gained access to the interior of parked vehicles and became trapped, or there was insufficient information to determine the context of the incident. This left 104 incidents in which cognitive errors were possible or probable important factors in the events leading to fatal heatstroke. However, 26 cases were ambiguous (e.g., the child could have been either intentionally left in the vehicle, or they could have been forgotten). Thus, we excluded those 26 incidents and focused our analysis on the 78 that appeared to be clear cases of cognitive error by the driver.

Further analysis of those 78 cases revealed that in 24 incidents, although a cognitive error appeared to be the cause of the fatal accident, there was insufficient first-person information about how the driver responded, or other details, to estimate whether false memories had, or had not, occurred. This left a sample of 54 incidents. For six of those 56 cases, the error that was made was not one of prospective memory, but of communication, that is, the child was not forgotten, the driver thought that the child had vacated the vehicle. This left a sample of 48 incidents, in which 50 children died. In each case, the fatality was a consequence of heatstroke while trapped in a vehicle, for which verbal reports from the drivers were available. The process of case selection is shown visually in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of cases from all known incidents of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke in the USA, 1999–2023.

2.4. Statistical Methods

For the occurrence of false memories, we have used simple counts, expressed as percentages, with 95% confidence intervals, estimated by bootstrapping. For null-hypothesis testing with inferential statistics, parametric or nonparametric methods were used as appropriate. For categorical data, Chi-squared tests have been employed, or Fisher’s Exact test when expected cell counts are below 5. All inferential analyses were two-tailed with a significance threshold of 0.05. Calculations were performed with SPSS v29.

3. Results

3.1. Incident Details

Details of the 48 incidents are shown in Table 1. Two of the incidents involved two child fatalities, so the total number of cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke is 50.

Table 1.

Details of all 48 fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke incidents analyzed (50 fatalities), and broken down by possible false memory presence.

3.2. Media Details

Of the 48 incidents analyzed here, the modal number of reports accessed for each was three (27 incidents), which was dependent on how many news outlets covered the accident. For one incident, only one report was available; for another nine, separate reports were available and analyzed. We evaluated the media information available for those 48 incidents as being ‘medium quality’ (33/48), or as ‘high quality’ (14/48), and only one as low-quality evidence.

3.3. Evidence of False Memories

From the 48 incidents analyzed, only one (2.1%, 95%CI = 0.0–6.6%) explicitly reported a false memory of removing children from the vehicle. The statement was given by a police officer saying that the driver honestly believed, without any doubt, that they had dropped the children off at daycare. In actuality, the driver had set off with a plan to drop the children at a daycare center but had instead driven to work and parked the vehicle outside for several hours, with two young children left on the backseat. It is notable that in this incident, the driver was not prosecuted, despite the majority of similar cases in the USA resulting in prosecutions (Hammett et al., 2021). This supports the view that the driver’s description of events, including the false memory, was believed by the law enforcement agencies involved.

One other incident included information that we classified as probable false memory (2.1% of the 48 incidents, 95%CI = 0.0–6.6%). Similar to the case described above, a driver dropped two of their children at daycare but forgot to drop a third child at a different location before parking the vehicle for an extended period, with the child trapped inside. The news reports quote that the driver insisted that she had dropped the child off at daycare, when in fact that did not happen. That statement was made before the child was found, deceased, in the vehicle. For both of these cases, we had classified the media information available as medium quality.

There were also several cases that were suggestive of false memory, which we had classified as possible examples. In fact, of the 48 incidents, eight were classified in that way (16.7%, 95%CI = 6.7–27.1%). In these cases, the drivers made rather vaguer statements; for example, that they ‘assumed’ that they had dropped their children at daycare, while also acknowledging that they had, in fact, forgotten to do so. For the remaining incidents, 38/48, 79.2% (95%CI = 67.3–89.8%), there were no verbal reports by the drivers of the vehicles to give any indication of false memories.

3.4. Factors Associated with False Memories

We grouped all incidences of fatal pediatric heatstroke that we classified as at least possible false memory (n = 10, 21%). We then compared them to the incidents in which there was no evidence to suggest false memories (n = 38, 79%). These comparisons are summarized in Table 1. Regarding the sex of the victims, when there were at least possible false memories, nine victims were male, and only three were female, a significant overrepresentation, compared to incidents in which no false memories were reported, χ2 (N = 49) = 5.02, p = 0.02, V = 0.32. Victims appeared to be older when there was a false memory, by about 6 months, but the difference was not significant, Mann–Whitney U = 296.5, p = 0.12. There was no association with the sex of the driver or other adults in the vehicle, χ2 (N = 49) = 0.72, p = 0.70, V = 0.12, nor with the number of adults in the vehicle. The age information of the drivers had too many missing data points to be analyzed. In cases with possible false memory, the mean number of children in the vehicle during the journey was 2.3 (range 1–5), compared to 1.5 (range 1–4) in incidents without false memory. However, probable false memory was not significantly associated with journeys involving more than one child, χ2 (N = 47) = 0.89, p = 0.35, V = 0.14. In contrast, false memory was statistically associated with there being more than one fatality. There were two incidents from ten with possible false memory, which involved more than one child fatality, compared to zero out of 38 incidents without false memory, Fisher’s exact p = 0.04, V = 0.41.

There was no significant difference associated with the planned stops on the journey, Mann–Whitney U = −0.498, p = 0.64. For ratings of the routineness of the journey, there was also little difference between groups. For incidents with possible false memory, the mean rating was 2.0 (range = 0–4), which was the same as for incidents without evidence of false memory, plainly not significantly different, confirmed as such statistically, Mann–Whitney U = −0.02, p = 0.98. Just focusing on the two cases that likely included false memory, there was no strong evidence that the journeys were highly routine.

4. Discussion

We found that one or two cases, depending on the stringency of the criteria used, involved credible evidence of false memories reported by drivers who had accidentally left children in vehicles, with fatal consequences. This is from a final sample of 48 incidents. In both cases, the drivers explicitly expressed having a memory or removing the child from the vehicle. And in both cases, the falsity of that memory was demonstrated by the presence of the deceased children, still in the vehicle.

To be clear, these are memories that the person holds, despite simultaneously knowing them to be untrue. One or two cases are clearly less than would be expected from the ‘universal’ phenomenon described by a previous writer on the topic (Diamond, 2016, 2019). However, we did identify an additional eight incidents that we thought possibly involved false memories. Consequently, using a simple Popperian falsification approach (Popper, 1959), we are confident in rejecting the thesis that false memories do not occur in cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke. Given that they exist, an important question is why?

Diamond (2016, 2019) has argued that the cause of the incidents is non-conscious habit-driven behavior, and that false memories are extremely common, perhaps universal. However, he does not provide an explanation for the occurrence of false memories, other than “in a process which is not well understood, the brain creates a false memory that the child has been taken to the planned destination” (p. 122). This suggests an active (false-)memory formation process.

If it is an active process, our observations may be relevant. When there was more than one heatstroke victim, false memory was statistically more likely to occur, compared to cases with only one victim. Although the number of observations is low, this does require consideration. It could possibly indicate a psychological response to the trauma, as it is reasonable to assume that making an error that leads to two child deaths is more traumatic than a single death. Possibly related to this, false memories were observed more often when the deceased child was a boy than when the child was a girl. There is some evidence that deaths of boys produce stronger grief responses than deaths of girls (Littlefield & Rushton, 1986; Hazzard et al., 1992; Chen et al., 2012).

It is known that people tend to fill in details within traumatic scenarios (Strange & Takarangi, 2012), and parents suffering infant deaths tend to experience changes to their general cognitive outlook (Jind et al., 2010). Cognitive dissonance, the active alteration of beliefs to make them consistent (Festinger, 1957), perhaps could produce sufficient friction between beliefs that a false memory was formed. However, the memories that we have described do not appear to have achieved consonance- they are, in fact, incompatible. If anything, they indicate an absence of an active mechanism to reduce dissonance.

An alternative explanation comes from clinical neuroscience. False memories are relatively common in disorders of the higher nervous system. Their occurrence in vehicular heatstroke cases could perhaps be explained by the extra shock and emotional responses associated with accidentally forgetting about children in one’s care, leading to their death. When there is an organic brain disorder, the tendency to create false memories is called confabulation (Gilboa et al., 2002). This term has also been applied to the false memories reported by drivers involved in pediatric vehicular heatstroke (Breitfeld, 2020). However, true neuropsychological confabulations tend to be actually believed by the patient. The false memories described here are recognized by the individuals involved as being incorrect recall of events. As such, confabulation may not be an appropriate conceptualization.

Rather than pathologizing, we feel that the incorrect memories described in this study may be considered normal. False memories are actually likely normal aspects of human cognition. As mentioned earlier, numerous experimental procedures have been applied to show that false memories can be implanted within the recollections of research participants (e.g., Loftus & Palmer, 1974). And there is much evidence from the recollections of natural events to suggest that memory distortions, or even frank false memories of things that never happened, occur normally in non-clinical participants (Garry et al., 2009).

We suggest that script theory, also known as schema theory, provides the best explanation for false memories of removing children from vehicles. This has been proposed in various forms from different research perspectives; however, a particularly detailed and influential version was presented by Schank and Abelson (1977). Though almost half a century has passed since that work was published, the central idea of scripts remains popular for explaining human behavior (e.g., Taylor et al., 2023). The original script theory of Schank and Abelson theory was designed to aid understanding of natural language but was based around an individual’s episodic memory. They proposed that episodic memories build up into scripts for events that occur frequently in sequential action sequences. These scripts have been described as ‘standardized generalized episodes’ (p. 19), existing as structural representations of chains of typical events, from a first-person perspective, in well-known contexts. The benefit of the script is that it provides typical context, reduces processing requirements, and allows ‘filling in the blanks in understanding’ (p. 18). Although originally proposed to explain human language comprehension and ways to produce it in silico with artificial intelligence, script theory has proven useful in explaining the occurrence of false memories.

Memory research has tended to use the term schema rather than script, but the general principles are the same and constitute one of the main ways that false memories are interpreted (Steffens & Mecklenbräuker, 2007). Such false memories have been particularly investigated in connection with witnesses to crimes. Laboratory studies show that, for example, people falsely recall aspects in crime scenarios, inserting pieces of script-consistent information. Furthermore, they are highly confident that these false memories are real (García-Bajos & Migueles, 2003).

Driving is well-recognized as an activity that becomes highly automated (Summala, 2000). It fits all of the characteristics of script/schema development, being routine, sequential, automated, first-person, etc. Although there are various levels of cognitive control, from attentive, top-down control for unexpected activities, continuous control, particularly for highly routine journeys such as a daily commute, relies heavily on action schemata (Ranney, 1994). Furthermore, studies of drivers on routine trips show that false memories of events occurring within journeys are very common (Charlton & Starkey, 2018). Importantly, these false memories occur most commonly with script/schema consistent events, that is, things that could typically be expected in a journey, but did not actually happen during the journey that was probed (Charlton & Leov, 2021).

It seems reasonable to assume that, when driving routine journeys with children, removing them from the vehicle becomes a schema-based process. Following this, when the event does not happen for whatever reason, false memories would be expected, as the drivers interpret their own episodic recall of the journey through the schema they have built up from repeated similar journeys. This can lead to default values being used to fill the blanks in the memory. Furthermore, the extreme stress of realizing that a catastrophic error has occurred, causing a child’s fatality, would be expected to create much neurological, emotional, and cognitive disruption. In turn, that processing load could produce greater reliance on default values in scripts and other automatic modes of processing (Fabio et al., 2021).

Tentatively, this may therefore offer a new insight into the cause of pediatric vehicular heatstroke incidents. Past theorizing has focused on a stimulus-response habit system being a crucial causative factor, specifically, that it remains in control of driver behavior for too long (Diamond, 2016, 2019; Breitfeld, 2020; Murphy, 2020). The current observations suggest a slight modification, focused on scripts/schemata. These have been proposed as not only used for understanding and memory, but for additionally guiding routine behavior. Either proposed as ‘scripts in behavior’ (Abelson, 1981) or ‘action schemas’ (Cooper & Shallice, 2006), the same constructs that aid interpretation are said to be involved with control of routine behavior. As there is already an extensive literature on scripts from cognitive science and artificial intelligence (Schank & Abelson, 1977; Abelson, 1981; Taylor et al., 2023), modeling of the cognitive failure that leads to children being forgotten within vehicles and the potential for script-based memories to occur could be an avenue for future research using formal in silico methods (e.g., Cerone et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, we did not find any relationship between the existence of false memories and trip routineness. Such a relationship, if it had been observed, would have been consistent with script/schema theory. However, we acknowledge that the precision of our measures is low, as is our statistical power to detect associations. However, we still feel that scripts/schemata provide the best explanation for the false memories observed. Future research could explore the role of script/schema-based action on the occurrence of errors leading to children being accidentally left in vehicles, possibly with a closer examination of trip routineness, and the role of extreme psychological stress.

The research described here does have some other limitations. Most importantly, we have relied on secondary sources, specifically news media available on the internet. This may have limited the validity of the findings and should be considered when evaluating our explanation of the phenomena of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke. Furthermore, our observations of convincing false memories were few, which also may cast some doubt on the reliability of the research. As a large number of cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke result in legal investigations, some of the limitations described here could be attenuated by reliance on court records, arguably more reliable sources than media reports. A further limitation is that we only located a small number of convincing cases of false memory; as such, our interpretations are based on a very small set of observations. Related to this, our inferential statistical tests were also based on quite small data sets, which means that decisions based on null-hypothesis testing may be of reduced reliability. This should be kept in mind while interpreting the current findings.

5. Conclusions

False memories, specifically removing children from vehicles or dropping them off, do occur in cases of fatal pediatric vehicular heatstroke. We therefore provide evidence, in an academically citable form, of false memories in real life (as opposed to the better-known lab-induced false memories). These false memories may be more common when more than one child dies. There are reasonable grounds for arguing, therefore, that the severity of psychological trauma is a factor, perhaps indicating an active memory distortion process. However, it seems likely that scripts/schemata are also an important aspect, one that has not been explored previously in this context. Consequently, this approach has the potential to extend our understanding of how these catastrophic accidents occur and how they affect drivers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and A.C.; methodology, G.P. and P.K.; formal analysis, G.P.; investigation, G.P., M.S.G. and P.K.; data curation, G.P. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, P.K., M.S.G. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the data are publicly available and no identifiable human subjects were directly involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, the data file has not been made publicly available; however, it can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| M/F/B | Male/Female/Both |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Abelson, R. P. (1981). Psychological status of the script concept. American Psychologist, 36(7), 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adato, B., Dubnov-Raz, G., Gips, H., Heled, Y., & Epstein, Y. (2016). Fatal heat stroke in children found in parked cars: Autopsy findings. European Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmi, N., Montaldo, S., Pomilla, A., & Maraone, A. (2020). Forgotten baby syndrome: Dimensions of the phenomenon and new research perspectives. Rivista di Psichiatria, 55(2), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitfeld, E. (2020). Hot-car deaths and forgotten-baby syndrome: A case against prosecution. Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law, 25, 72–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerone, A., Murzagaliyeva, D., Nabiyeva, N., Tyler, B., & Pluck, G. (2022). In silico simulations and analysis of human phonological working memory maintenance and learning mechanisms with behavior and reasoning descriptive language (BRDL). In A. Cerone, M. Autili, A. Bucaioni, C. Gomes, P. Graziani, M. Palmieri, M. Temperini, & G. Venture (Eds.), Software engineering and formal methods. SEFM 2021 collocated workshops. SEFM 2021. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 13230). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, S. G., & Leov, J. (2021). Driving without memory: The strength of schema-consistent false memories. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 83, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, S. G., & Starkey, N. J. (2018). Memory for everyday driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 57, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. C., Kuo, C. C., Wu, T. N., & Yang, C. Y. (2012). Death of a son is associated with risk of suicide among parous women in Taiwan: A nested case-control study. Journal of Epidemiology, 22(6), 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cooper, R. P., & Shallice, T. (2006). Hierarchical schemas and goals in the control of sequential behavior. Psychological Review, 113(4), 887–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devan, B. D., Hong, N. S., & McDonald, R. J. (2011). Parallel associative processing in the dorsal striatum: Segregation of stimulus–response and cognitive control subregions. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 96(2), 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. (2016, June 20). Children dying in hot cars: A tragedy that can be prevented. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/children-dying-in-hot-cars-a-tragedy-that-can-be-prevented-60909 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Diamond, D. (2019). When a child dies of heatstroke after a parent or caretaker unknowingly leaves the child in a car: How does it happen and is it a crime? Medicine, Science and the Law, 59(2), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R. A., Picciotto, G., & Caprì, T. (2021). The effects of psychosocial and cognitive stress on executive functions and automatic processes in healthy subjects: A pilot study. Current Psychology, 41, 7555–7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima Siddiqui, G., Vir Singh, M., Shrivastava, A., Maurya, M., Tripathi, A., & Akhtar Siddiqui, S. (2021). Children left unattended in parked vehicles in India: An analysis of 40 fatalities from 2011 to 2020. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 67(3), fmaa075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P., Vena, F., Caporale, O., Del Volgo, V., Liberatore, P., Ianniello, F., Chiaretti, A., & Riccardi, R. (2013). Children left unattended in parked vehicles: A focus on recent Italian cases and a review of literature. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 39, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bajos, E., & Migueles, M. (2003). False memories for script actions in a mugging account. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 15(2), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, M., French, L., & Loftus, E. (2009). 2 False memories: A kind of confabulation in non-clinical subjects. In W. Hirstein (Ed.), Confabulation: Views from neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology and philosophy (pp. 33–66). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, A., Moscovitch, M., Baddeley, A., Kopelman, M., & Wilson, B. (2002). The cognitive neuroscience of confabulation: A review and a model. In A. D. Baddeley, M. D. Kopelman, & B. A. Wilson (Eds.), Handbook of memory disorders (2nd ed., pp. 315–342). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Grundstein, A., Dowd, J., & Meentemeyer, V. (2010). Quantifying the heat-related hazard for children in motor vehicles. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 91(9), 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guard, A., & Gallagher, S. S. (2005). Heat related deaths to young children in parked cars: An analysis of 171 fatalities in the United States, 1995–2002. Injury Prevention, 11(1), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammett, D. L., Kennedy, T. M., Selbst, S. M., Rollins, A., & Fennell, J. E. (2021). Pediatric heatstroke fatalities caused by being left in motor vehicles. Pediatric Emergency Care, 37(12), e1560–e1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazzard, A., Weston, J., & Gutterres, C. (1992). After a child’s death: Factors related to parental bereavement. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 13(1), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jind, L., Elklit, A., & Christiansen, D. (2010). Cognitive schemata and processing among parents bereaved by infant death. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltwang, M. E., Biganzoli, A., Barideaux, K., Jr., & Gray, J. M. (2024). Vehicular heatstroke: How do extralegal factors influence perceptions of blame, responsibility, forgiveness and punishment? Psychology, Crime & Law, 30(1), 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlefield, C. H., & Rushton, J. P. (1986). When a child dies: The sociobiology of bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S. (2020). Distracted guardians yield deadly results: When memory fails, additional regulations can protect children and animals from vehicular heat-stroke. William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, 44, 777–798. Available online: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol44/iss3/5 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Pluck, G., Bravo Mancero, P., Maldonado Gavilanez, C. E., Urquizo Alcívar, A. M., Ortíz Encalada, P. A., Tello Carrasco, E., Lara, I., & Trueba, A. F. (2019). Modulation of striatum based non-declarative and medial temporal lobe based declarative memory predicts academic achievement at university level. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluck, G., Cerone, A., & Villagomez-Pacheco, D. (2023). Executive function and intelligent goal-directed behavior: Perspectives from psychology, neurology, and computer science. In P. Masci, C. Bernardeschi, P. Graziani, M. Koddenbrock, & M. Palmieri (Eds.), Software engineering and formal methods. SEFM 2022 collocated workshops. SEFM 2022. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 13765). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldrack, R. A., & Packard, M. G. (2003). Competition among multiple memory systems: Converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia, 41(3), 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. Hutchinson. [Google Scholar]

- Ranney, T. A. (1994). Models of driving behavior: A review of their evolution. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 26(6), 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. (1984). Chapter 14: Lapses of attention in everyday life. In R. Parasuraman, & D. R. Davies (Eds.), Varieties of attention. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. (1990). Human error. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, T. W., & Costa, R. M. (2017). Habits. Current Biology, 27(22), R1200–R1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding: An inquiry into human knowledge structures. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M. C., & Mecklenbräuker, S. (2007). False memories. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 215(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, D., & Takarangi, M. K. (2012). False memories for missing aspects of traumatic events. Acta Psychologica, 141(3), 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summala, H. (2000). Automatization, automation, and modeling of driver’s behavior. Recherche-Transports-Sécurité, 66, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D., Gönül, G., Alexander, C., Züberbühler, K., Clément, F., & Glock, H. J. (2023). Reading minds or reading scripts? De-intellectualising theory of mind. Biological Reviews, 98(6), 2028–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricomi, E., Balleine, B. W., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2009). A specific role for posterior dorsolateral striatum in human habit learning. European Journal of Neuroscience, 29(11), 2225–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, V. V., Dickinson, A., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2007). Determining the neural substrates of goal-directed learning in the human brain. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(15), 4019–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washabaugh, A. (2020). Child vehicular heatstroke deaths: How the criminal legal system punished grieving parents over a neurobiological response. Cardozo Law Review De-Novo, 78, 195–223. Available online: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/de-novo/78 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).