Detecting Construct-Irrelevant Variance: A Comparison of Network Psychometrics and Traditional Psychometric Methods Using the HEXACO-PI Dataset

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impact of CIV Items on Measurement Validity

1.2. Traditional Psychometric Approaches for Identifying CIV Items

1.3. Network Psychometrics: An Alternative Approach to CIV Item Detection

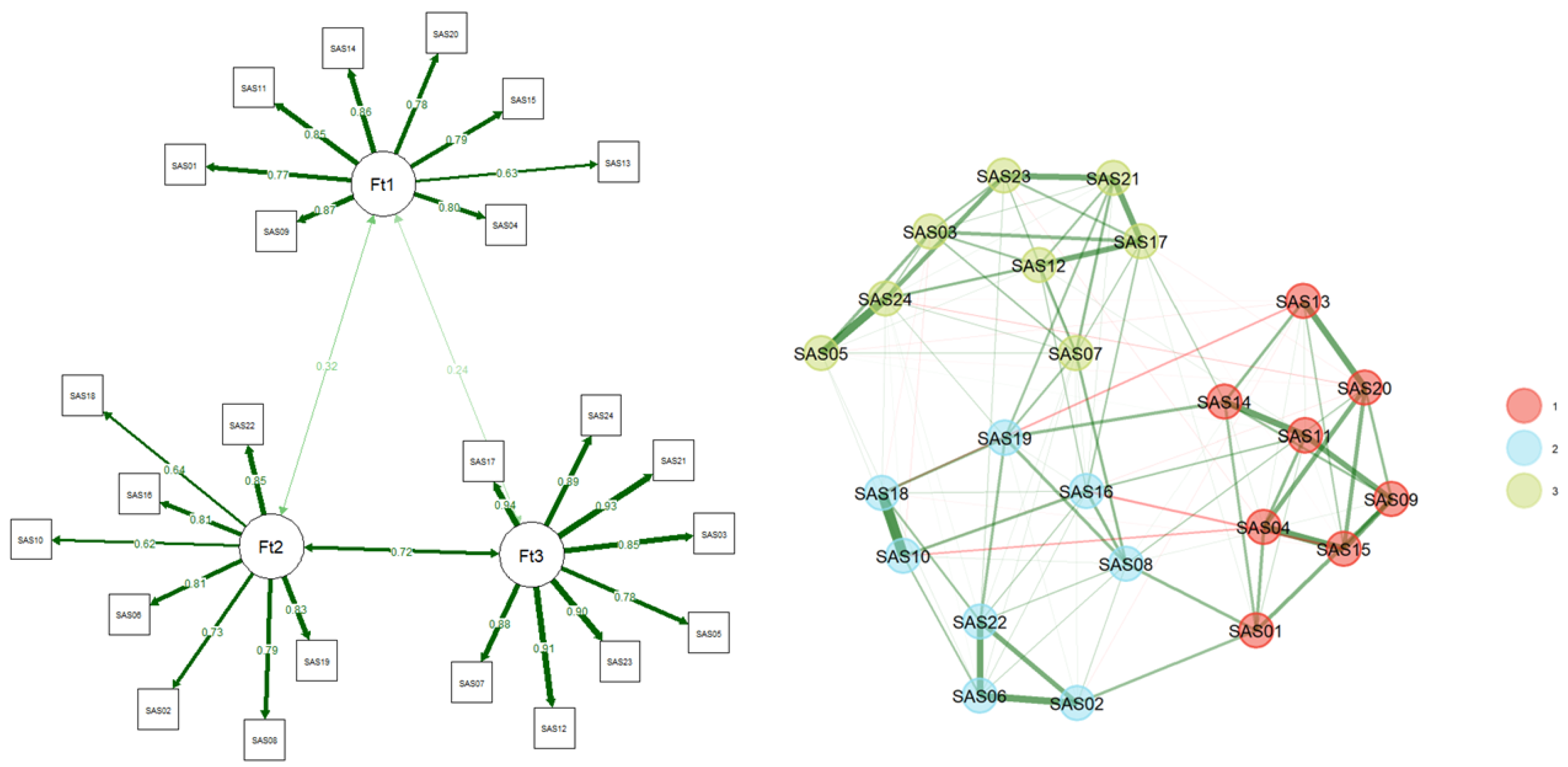

1.3.1. EGA

1.3.2. UVA

1.3.3. TMFG

1.4. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.2. Data Analysis

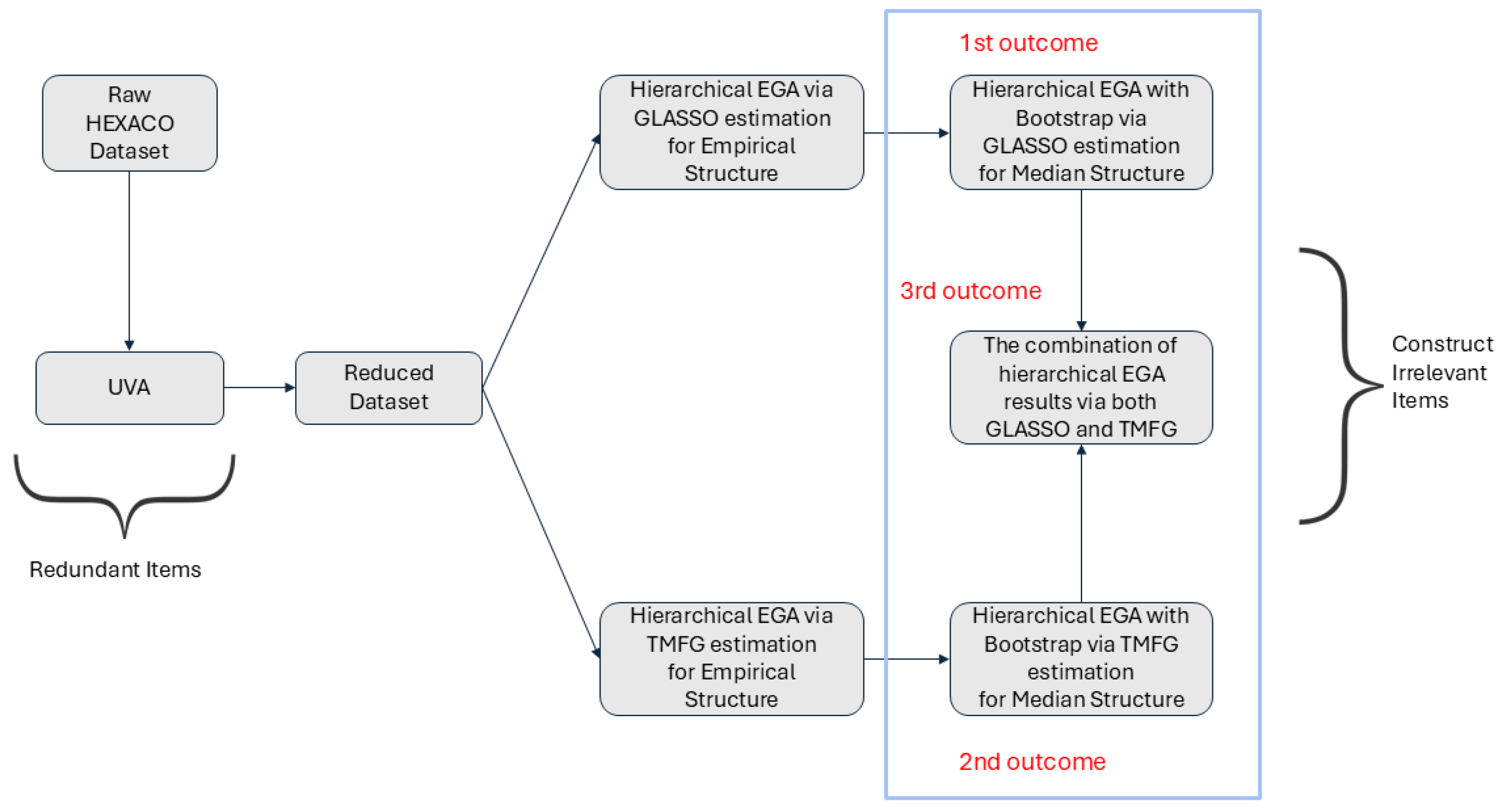

2.2.1. Network Psychometrics Analysis

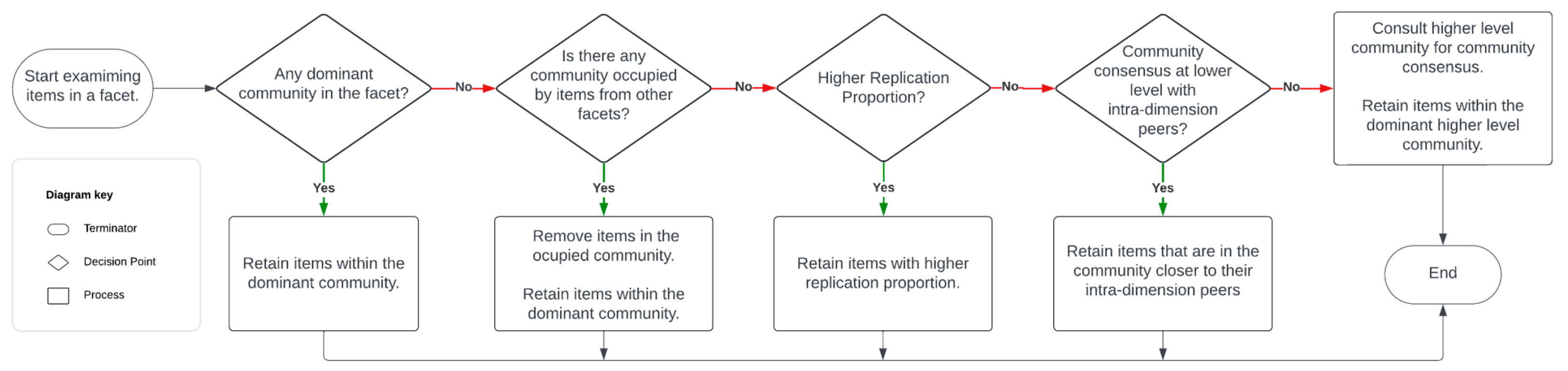

Item Filtering Process of the Network Approach

- Check the Main Community: First, examine the community where most of the items from a specific facet are grouped. For example, if most “modesty” items are in the 2nd community, but a few are in the 3rd, the outlier items in the 3rd community are identified as construct-irrelevant and removed.

- Handle Ties or Small Differences: When there is a tie between communities, or the difference is small (e.g., only one item), preference is given to the community where other related items are grouped. For example, if “modesty” items are evenly split between the 2nd and 3rd communities, but most “greed avoidance” items are in the 3rd community, the modesty items in the 3rd community were removed for consistency.

- Consult Replication Proportion: If the above guideline does not apply, the stability of the communities is checked using replication proportions. This shows how often items are consistently placed in the same community during bootstrapping. For example, if three modesty items are in the 2nd community and two are in the 3rd, but the replication proportion for the 2nd community is lower than the within-facet mean, items in the 2nd community may be removed to maintain the stability of the measurement.

- Use Intra-Dimension Peers: If two communities are still tied in terms of item count and replication proportion, reference their peers within the same dimension. For instance, if two “unconventionality” items are in community 37 and three in community 8, and no other facets are associated with these communities, but facets like aesthetic appreciation, inquisitiveness, and creativity are grouped in communities 34–36, it may be best to eliminate items in community 8 as it is more of an outlier within the dimension, given that community reflects the number of latent factors in a domain (H. F. Golino & Epskamp, 2017; Jiménez et al., 2023).

- Default to Higher-Level Community: If no consensus can be reached at the lower level (i.e., all items belong to unique communities or the communities are already occupied by items from other facets), the higher-level community allocation takes precedence. For example, if four items are spread across communities 5, 7, 8, and 9 at the lower level but three of them belong to community 4 at the higher level, the item associated with another higher-level community was excluded to maintain coherence.

Post-Reduction Analysis of the Network Approach

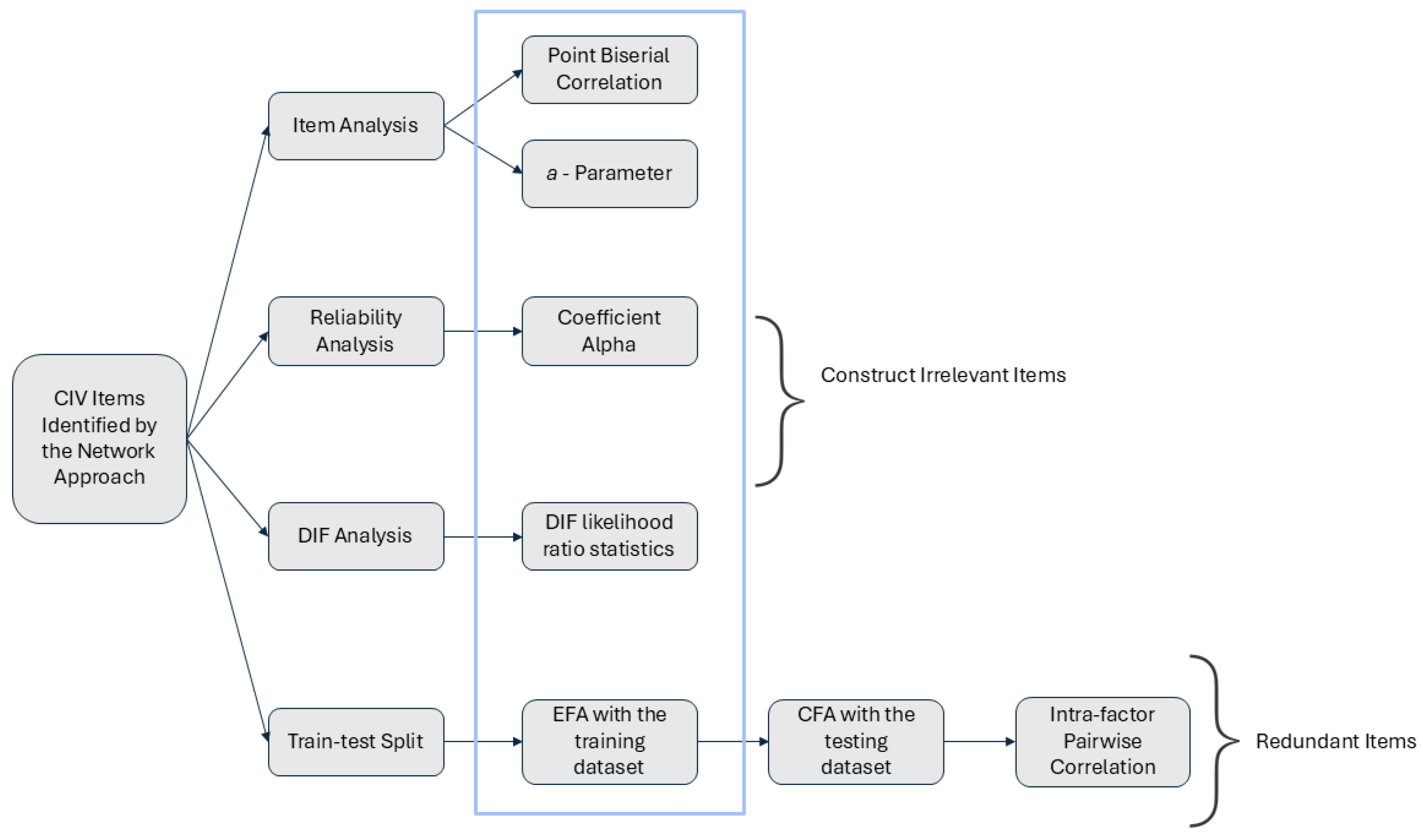

2.2.2. Traditional Psychometrics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Network Psychometrics

3.1.1. UVA Analysis

3.1.2. Hierarchical EGA with GLASSO

- Non-Dominant Community Assignment: Items in the facets of Sincerity (Hsinc 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9), Fairness (HFair5), Greed Avoidance (HGree8), and others were removed as they were assigned to non-dominant or minority communities, suggesting weak alignment with core construct definitions.

- Occupied or Exclusive Community Assignment: Items in facets such as Sincerity, Modesty, and Flexibility were excluded due to assignment to occupied or exclusive communities, indicating possible divergence from intended construct facets.

- Low Replication Proportion: Items in facets like Anxiety, Dependence, and Sentimentality were removed based on low replication proportions, reflecting inconsistencies in measurement across communities.

3.1.3. Hierarchical EGA with TMFG

- Occupied or Minority Community Assignment: Items within the Sincerity (HSinc 5, 7, 9, 10), Fairness (HFair5), Greed Avoidance (HGree 1, 2), and other facets were removed due to their assignment to occupied or minority communities, suggesting they diverged from the main constructs.

- Low Replication Proportion: Items across facets such as Social Boldness, Dependence, and Expressiveness were excluded due to low replication proportions, indicating inconsistent measurement reliability within these communities.

- Community Overlap with Related Facets: Items in the Unconventionality facet (e.g., OUnco 4, 10) were assigned to the same community as Creativity items, a permissible overlap given their shared emphasis on unique perspectives, norm-challenging, and innovation (Ashton, 2023).

3.1.4. Hierarchical EGA with Both GLASSO and TMFG

- Honesty/Humility: HSinc 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10; HFair 1, 5; HGree 1, 2, 3, 4, 8; HMode 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10.

- Emotionality: EAnxi 5, 7, 8, 9; EDepe 4, 5, 6, 7, 9; ESent 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

- Extraversion: XExpr 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10; XSocB 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; XSoci 2, 4; XLive 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10.

- Agreeableness: AForg 7, 9, 10; AGent 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9; AFlex 1, 2, 4, 10; APati 6, 10.

- Conscientiousness: COrga 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 10; CDili 3, 5, 10; CPerf 3, 9, 10; CPrud 1, 2, 3.

- Openness to Experience: OAesA 1, 5; OInqu 2, 4, 5; OCrea 1, 3, 8, 9, 10; OUnco 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

3.1.5. Model Fit Evaluation for Final Condition Selection

Theoretical Fit Evaluation

Empirical Fit Evaluation

Network Fit Evaluation

Final Dataset Selection

3.1.6. Summary of Network Findings

3.2. Traditional Psychometrics

3.2.1. Item Analysis

- Honesty/Humility: 9 items with Δ ranges from −0.11 to −1.041 (HSinc9, 10; HFair5; HGree1, 2, 3, 8; HMode2, 3).

- Emotionality: 9 items with Δ ranges from −0.053 to −0.568 (EAnxi7, 8; EDepe6, 7, 9; ESent5, 6, 7, 8).

- Extraversion: 8 items with Δ ranges from −0.150 to −0.582 (XExpr2, 5, 10; XSocB1, 6, 10; XLive7, 10).

- Agreeableness: 9 items with Δ ranges from −0.066 to −0.869 (AForg9, 10; AGent2, 4, 9; AFlex1, 2, 4; APati10).

- Conscientiousness: 4 items with Δ ranges from −0.048 to −0.513 (COrga5, 10; CPerf3, 10).

- Openness to experience: 9 items with Δ ranges from −0.035 to −0.936 (OInqu5; OCrea3, 9, 10; OUnco4, 6, 7, 8, 9).

3.2.2. DIF Analysis

- Honesty/Humility: 15 items showed DIF (χ2 = 11.361–280.467, p < 0.05), including items from HSinc, HFair, HGree, and HMode facets.

- Emotionality: 15 items displayed DIF (χ2 = 10.615–179.562, p < 0.05), including items from EAnxi (5, 7, 9), EDepe (4, 5, 6, 7, 9), and ESent (2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10) facets.

- Extraversion: 18 items exhibited DIF (χ2 = 6.942–104.018, p < 0.05), including items from XExpr (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8), XSocB (1, 3, 8, 9, 10), XSoci (2, 4), and XLive (3, 6, 7, 8) facets.

- Agreeableness: 12 items showed DIF (χ2 = 11.323–163.879, p < 0.05), including items from AForg (7, 10), AGent (1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 9), AFlex (2, 4, 10), and APati (6) facets.

- Conscientiousness: 9 items demonstrated DIF (χ2 = 6.877–116.98, p < 0.05), including items from COrga (1, 2, 3, 5), CDili (3, 5, 10), CPerf (3), and CPrud (1) facets.

- Openness: 11 items displayed DIF (χ2 = 7.716–302.163, p < 0.05), including items from OAesA (1, 5), OInqu (2), OCrea (1, 9, 10), and OUnco (4, 5, 6, 8, 10) facets.

3.2.3. Factor Analysis

EFA for Construct Irrelevant Items

- Honesty/Humility: 9 items misloaded (ESent8, AForg7, 8, AGent7, 10, AFlex8, 10, OInqu9, OAesA10).

- Emotionality: 14 items misloaded (APati10, CPrud7, 9, 10, HGree8, HFair5, XLive9, 10, HSinc9, 10, HMode2, 4, AFlex4, 5).

- Extraversion: 6 items misloaded (HMode7, AForg9, 10, EDepe9, HGree1, OAesA9).

- Agreeableness: 1 item misloaded (HMode1).

- Conscientiousness: 3 items misloaded (OUnco8, HMode8, HGree2).

- Openness: 9 items misloaded (EFear5, 6, 8, 9, 10, XSocB5, XLive7, AGent9, HMode3).

CFA for Model Fit and Psychometrically Redundant Items

3.2.4. Summary of Traditional Findings

3.3. The Comparison of CIV Items Between the Two Approaches

3.3.1. Inter-Approach Agreement

- Honesty-Humility: 18 items (e.g., Sinc2, HSinc7, HFair1, HGree3, HMode10).

- Emotionality: 16 items (e.g., EAnxi5, EDepe4, ESent7).

- Extraversion: 20 items (e.g., XExpr1, XSocB6, XLive8).

- Agreeableness: 14 items (e.g., AForg7, AGent4, AFlex10).

- Conscientiousness: 11 items (e.g., COrga2, CDili3, CPrud1).

- Openness to Experience: 15 items (e.g., OAesA1, OCrea9, OUnco7).

3.3.2. Inter-Approach Disagreement

3.3.3. Summary of Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIV | Construct-Irrelevant Variance |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| DIF | Differential Item Functioning |

| CTT | Classical Test Theory |

| IRT | Item Response Theory |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| EGA | Exploratory Graph Analysis |

| UVA | Unique Variable Analysis |

| TMFG | Triangulated Maximally Filtered Graph |

| GLASSO | Graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| TEFI | Total Entropy Fit Index |

| wTO | Weighted Topological Overlap |

| IPIP | International Personality Item Pool |

| MHRM | Metropolis-Hastings Robbins-Monro |

| BH | Benjamini-Hochberg |

| pBis | point-Biserial Correlation |

References

- Acar Güvendir, M., & Özer Özkan, Y. (2022). Item removal strategies conducted in exploratory factor analysis: A comparative study. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 9(1), 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. M., & Bordbar, S. (2017). Differential item functioning analysis of high-stakes test in terms of gender: A Rasch model approach. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(1), 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, M. C. (2023). Individual differences and personality (4th ed.). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The IPIP–HEXACO scales: An alternative, public-domain measure of the personality constructs in the HEXACO model. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(8), 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K., Shibata, R., & Sibuya, M. (2004). Partial correlation and conditional correlation as measures of conditional independence. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Statistics, 46(4), 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D., Deserno, M. K., Rhemtulla, M., Epskamp, S., Fried, E. I., McNally, R. J., Robinaugh, D. J., Perugini, M., Dalege, J., Costantini, G., Isvoranu, A.-M., Wysocki, A. C., van Borkulo, C. D., van Bork, R., & Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 1(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, O., & Suh, Y. (2017). Detecting multidimensional differential item functioning with the multiple indicators multiple causes model, the item response theory likelihood ratio test, and logistic regression. Frontiers in Education, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). Field listing—Languages. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/archives/2021/field/languages/ (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Chalmers, R. P. (2012). mirt: A multidimensional item response theory package for the R environment. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(6), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, P. K. H., Dillon, D. B., & Swinbourne, A. L. (2018). An examination of the internal consistency and structure of the statistical anxiety rating scale (STARS). PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0194195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A. P., Cotter, K. N., & Silvia, P. J. (2019). Reopening openness to experience: A network analysis of four openness to experience inventories. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(6), 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A. P., Garrido, L. E., & Golino, H. (2023). Unique variable analysis: A network psychometrics method to detect local dependence. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 58(6), 1165–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A. P., & Golino, H. (2021a). Estimating the stability of psychological dimensions via bootstrap exploratory graph analysis: A monte carlo simulation and tutorial. Psych, 3(3), 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A. P., & Golino, H. (2021b). On the equivalency of factor and network loadings. Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), 1563–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A. P., Kenett, Y. N., Aste, T., Silvia, P. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2018). Network structure of the wisconsin schizotypy scales–short forms: Examining psychometric network filtering approaches. Behavior Research Methods, 50(6), 2531–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cor, M. K. (2018). Measuring social science concepts in pharmacy education research: From definition to item analysis of self-report instruments. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, M. (2004). Use of differential item functioning (DIF) analysis for bias analysis in test construction. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 30(4), 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Champlain, A. F. (2010). A primer on classical test theory and item response theory for assessments in medical education. Medical Education, 44(1), 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, S. M. (2002). Construct-irrelevant variance and flawed test questions: Do multiple-choice item-writing principles make any difference? Academic Medicine, 77(10), S103–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S. (2017). Network psychometrics [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, C. F., & Muthukrishna, M. (2023). Parsimony in model selection: Tools for assessing fit propensity. Psychological Methods, 28(1), 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, W. H., & French, B. F. (2019). Educational and psychological measurement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, W. H., French, B. F., & Hazelwood, A. (2023). A comparison of confirmatory factor analysis and network models for measurement invariance assessment when indicator residuals are correlated. Applied Psychological Measurement, 47(2), 014662162311517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D. B., LaBrish, C., & Chalmers, R. P. (2012). Old and new ideas for data screening and assumption testing for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H., Christensen, A., Moulder, R., Garrido, L. E., Jamison, L., & Shi, D. (2022). EGAnet: Exploratory graph analysis—A framework for estimating the number of dimensions in multivariate data using network psychometrics. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/EGAnet/index.html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Golino, H., Moulder, R., Shi, D., Christensen, A. P., Garrido, L. E., Nieto, M. D., Nesselroade, J., Sadana, R., Thiyagarajan, J. A., & Boker, S. M. (2021). Entropy fit indices: New fit measures for assessing the structure and dimensionality of multiple latent variables. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(6), 874–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golino, H. F., & Epskamp, S. (2017). Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0174035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haladyna, T. M., & Downing, S. M. (2005). Construct-irrelevant variance in high-stakes testing. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 23(1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haladyna, T. M., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2013). Developing and validating test items. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist, M. N., Wright, A. G., & Molenaar, P. C. (2021). Problems with centrality measures in psychopathology symptom networks: Why network psychometrics cannot escape psychometric theory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, R., & Jones, R. (1993). An NCME instructional module on comparison of classical test theory and item response theory and their applications to test development. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 12(3), 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R. K., Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. J. (1991). Fundamentals of item response theory (Vol. 2). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hladká, A., & Martinková, P. (2020). difNLR: Generalized logistic regression models for DIF and DDF detection. The R Journal, 12(1), 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Dong, Y., Han, C., & Wang, X. (2023). Evaluating the language- and culture-related construct-irrelevant variance and reliability of the sense of school belonging scale: Suggestions for revision. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 4(18), 852–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isvoranu, A.-M., Epskamp, S., Waldorp, L. J., & Borsboom, D. (Eds.). (2022). Network psychometrics with R: A guide for behavioral and social scientists. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M., Abad, F. J., Garcia-Garzon, E., Golino, H., Christensen, A. P., & Garrido, L. E. (2023). Dimensionality assessment in bifactor structures with multiple general factors: A network psychometrics approach. Psychological Methods, 30(4), 770–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. T. (2013). Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50(1), 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N. L. A. (2011). Judging behaviour and rater errors: An application of the many-facet rasch model. GEMA Online™ Journal of Language Studies, 11(3), 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Massara, G. P., Di Matteo, T., & Aste, T. (2016). Network filtering for big data: Triangulated maximally filtered graph. Journal of Complex Networks, 5(2), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellenbergh, G. J. (1995). Conceptual notes on models for discrete polytomous item responses. Applied Psychological Measurement, 19(1), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (pp. 13–103). American Council on Education and Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mislevy, R. J., & Chang, H.-H. (2000). Does adaptive testing violate local independence? Psychometrika, 65(2), 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A. J. S., Myers, N. D., & Lee, S. (2020). Modern factor analytic techniques: Bifactor models, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and bifactor-ESEM. In G. Tenenbaum, & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (1st ed., pp. 1044–1073). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowick, K., Gernat, T., Almaas, E., & Stubbs, L. (2009). Differences in human and chimpanzee gene expression patterns define an evolving network of transcription factors in brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(52), 22358–22363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbeck, F. W., Eid, M., & Lischetzke, T. (2006). Analysing multitrait–multimethod data with structural equation models for ordinal variables applying the WLSMV estimator: What sample size is needed for valid results? British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 59(1), 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcan, F. (2018). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Which one to use first? Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 9(4), 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P., & Latapy, M. (2006). Computing communities in large networks using random walks. Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications, 10(2), 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Reise, S. P., Bonifay, W., & Haviland, M. G. (2018). Bifactor modelling and the evaluation of scale scores. In P. Irwing, T. Booth, & D. J. Hughes (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of psychometric testing (1st ed., pp. 675–707). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, N., & Cook, D. (2023). Expanding tidy data principles to facilitate missing data exploration, visualization and assessment of imputations. Journal of Statistical Software, 105(7), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuilen, J., Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2021). Burnout–depression overlap: Exploratory structural equation modeling bifactor analysis and network analysis. Assessment, 28(6), 1583–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willse, J. T. (2018). CTT: Classical test theory functions. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=CTT (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Wood, D., Lowman, G. H., Armstrong, B. F., & Harms, P. D. (2023). Using retest-adjusted correlations as indicators of the semantic similarity of items. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(2), 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, C., Hutz, C. S., Yoo, H., & Hambleton, R. K. (2016). An application of item response theory to psychological test development. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 29(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Purpose | Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical EGA with | Identify the number of latent dimensions with community detection algorithms | RMSEA, SRMR, CFI, TLI, TEFI, Assigned Community |

| Hierarchical EGA with Bootstrapping | Identify the stability of estimated dimensions across multiple dataset variants | Dimensionality Replication, Proportion, Median Dimension |

| UVA | Identify redundant items (i.e., nodes) that may cause local dependency | wTO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wongvorachan, T.; Bulut, O. Detecting Construct-Irrelevant Variance: A Comparison of Network Psychometrics and Traditional Psychometric Methods Using the HEXACO-PI Dataset. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040088

Wongvorachan T, Bulut O. Detecting Construct-Irrelevant Variance: A Comparison of Network Psychometrics and Traditional Psychometric Methods Using the HEXACO-PI Dataset. Psychology International. 2025; 7(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleWongvorachan, Tarid, and Okan Bulut. 2025. "Detecting Construct-Irrelevant Variance: A Comparison of Network Psychometrics and Traditional Psychometric Methods Using the HEXACO-PI Dataset" Psychology International 7, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040088

APA StyleWongvorachan, T., & Bulut, O. (2025). Detecting Construct-Irrelevant Variance: A Comparison of Network Psychometrics and Traditional Psychometric Methods Using the HEXACO-PI Dataset. Psychology International, 7(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040088