Character Virtues in Romantic Relationships and Friendships During Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Virtues and Character Strengths

1.2. Romantic Relationships During Emerging Adulthood

1.3. Friendships During Emerging Adulthood

1.4. Character Virtues and Strengths and Their Role in Shaping Relationships

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims and Hypotheses of the Study

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Values in Action-114GR (VIA-114GR)

2.3.2. Sternberg’s Triangular Love Scale (STLS)

2.3.3. Friendship Network Satisfaction (FNS)

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Means, Standard Deviations, Skewness, and Kurtosis of Character Virtues and Strengths, Love Components, and Satisfaction from Friendships

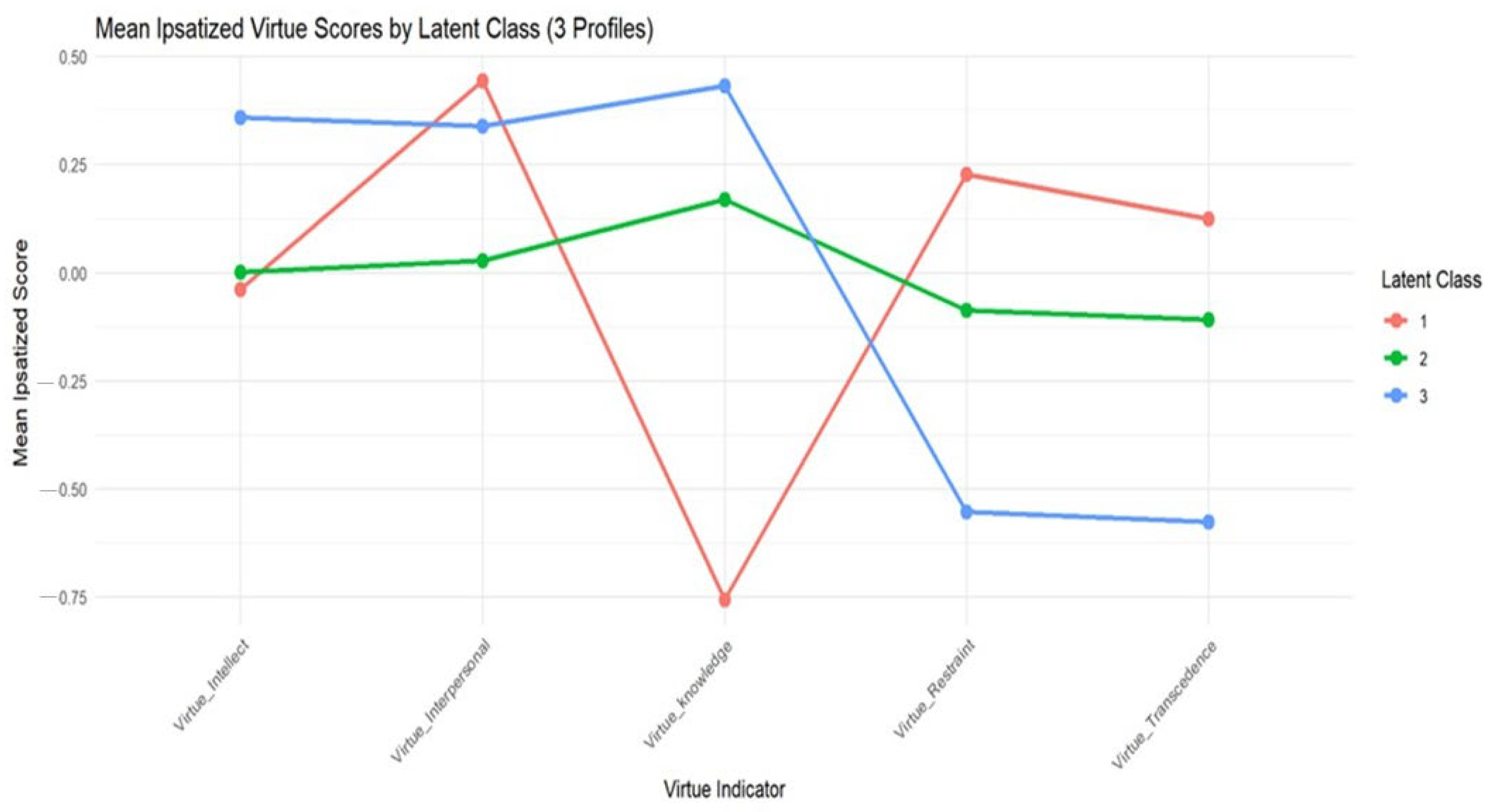

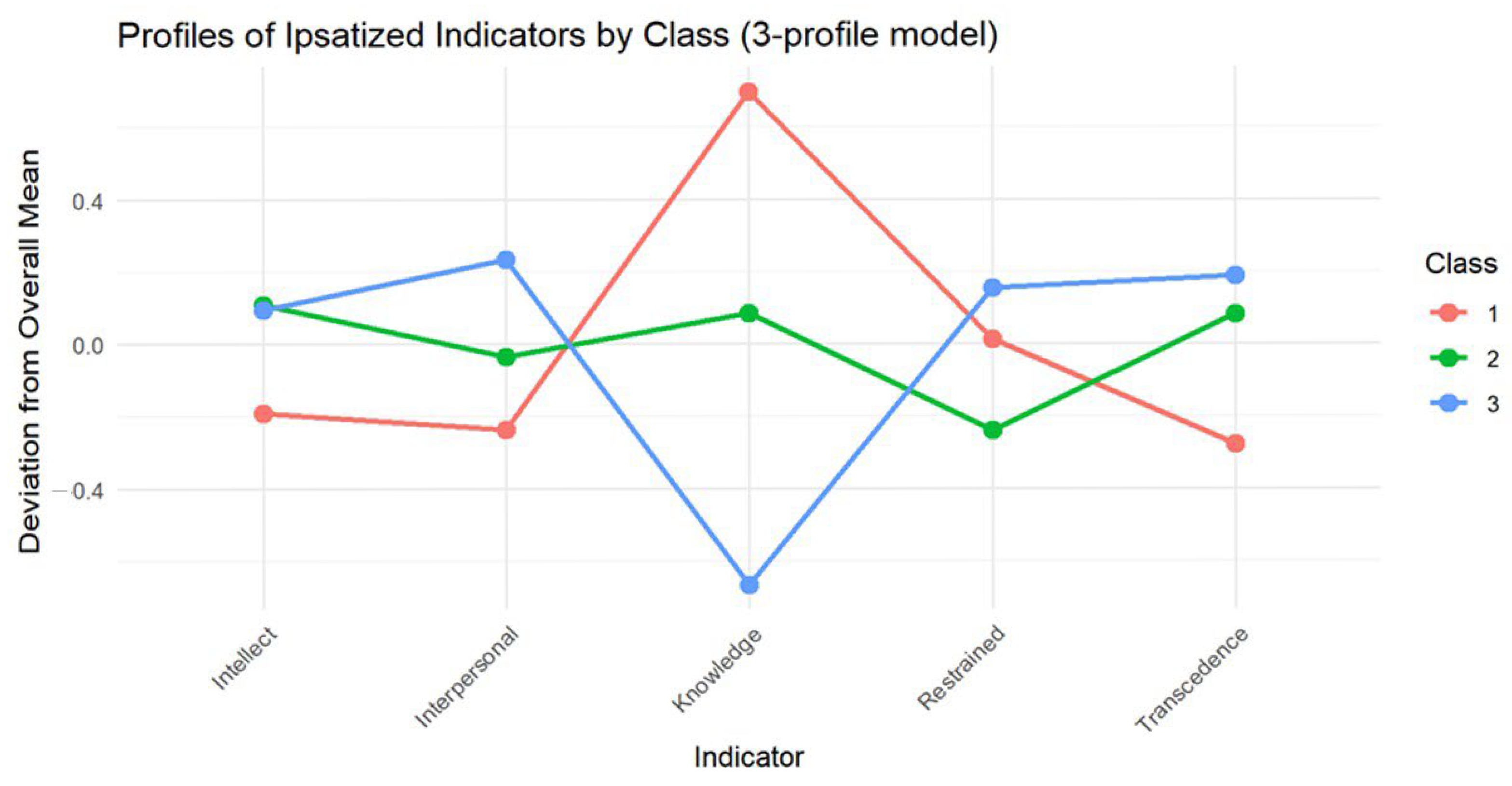

3.2. Virtue Profiles

3.3. The Association Between Character Virtue Profiles and Relationship Status

3.4. The Association of Virtue Profiles with Satisfaction from Friendships

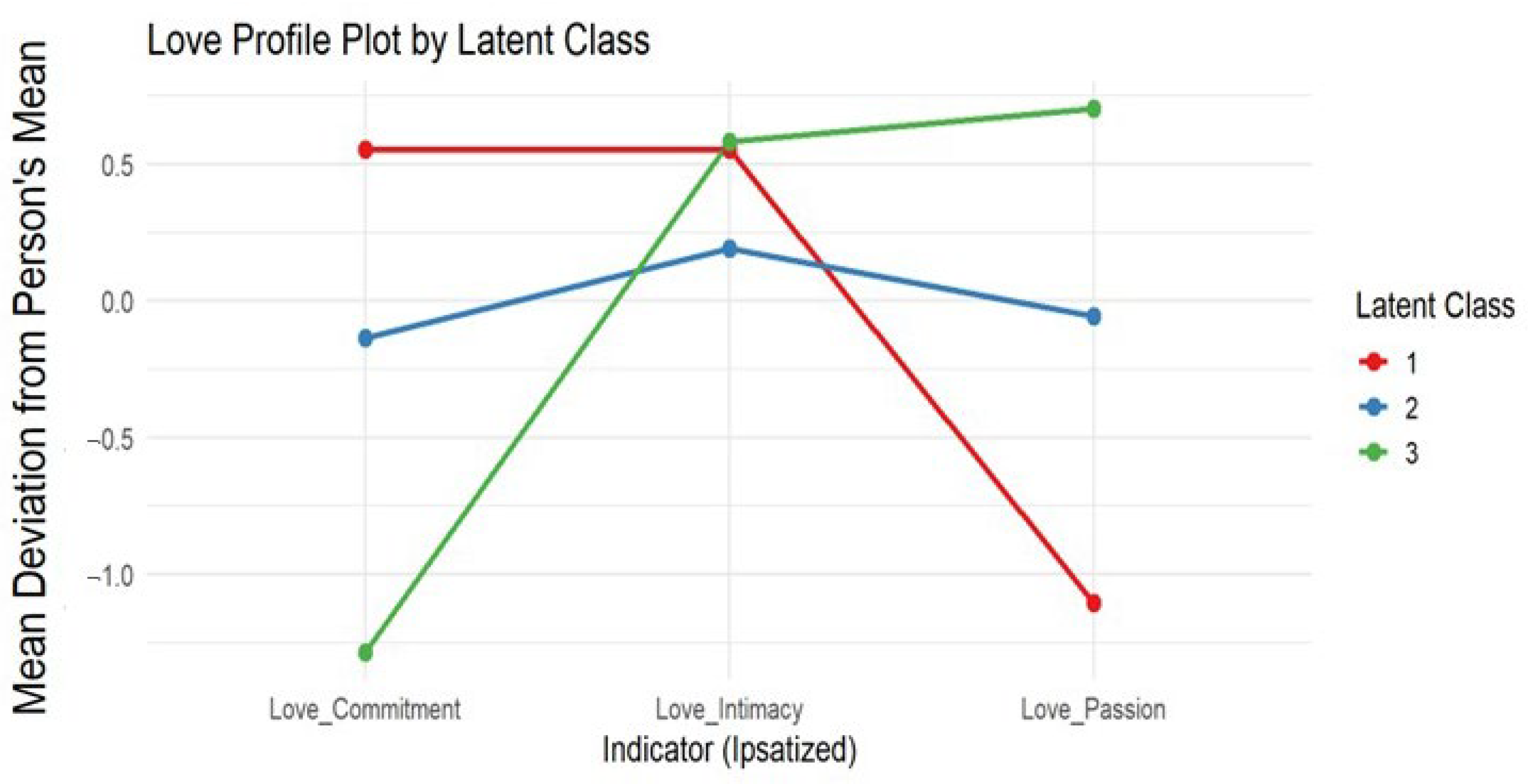

3.5. The Association of Virtue Profiles with Love Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Virtue Profiles

4.2. The Association of Virtue Profiles with Relationship Status

4.3. The Association of Virtue Profiles with Friendships

4.4. The Association of Virtue Profiles with Love Components

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akogul, S., & Erisoglu, M. (2017). An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy, 19(9), 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, C. T., Sidoti, C. L., Briggs, S. M., Reiter, S. R., & Lindsey, R. A. (2017). Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, D., Ruch, W., Margelisch, K., Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2020). Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: An analysis of different living conditions. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeney, J. E., Stepp, S. D., Hallquist, M. N., Ringwald, W. R., Wright, A. G. C., Lazarus, S. A., Scott, L. N., Mattia, A. A., Ayars, H. E., Gebreselassie, S. H., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2019). Attachment styles, social behavior, and personality functioning in romantic relationships. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 10(3), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiman-Meshita, M., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2022). Is it me or you? An actor-partner examination of the relationship between partners’ character strengths and marital quality. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(1), 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, S., & Poulin, F. (2016). Romantic relationship patterns from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Associations with family and peer experiences in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(5), 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1979). The Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(4), 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutus, S., Aguinis, H., & Wassmer, U. (2013). Self-reported limitations and future directions in scholarly reports: Analysis and recommendations. Journal of Management, 39(1), 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W. M., Motzoi, C., & Meyer, F. (2009). Friendship as process, function, and outcome. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 217–231). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Camirand, E., & Poulin, F. (2022). Links between best friendship, romantic relationship, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 183(4), 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, N., Norem, J. K., Niedenthal, P. M., Langston, C. A., & Brower, A. M. (1987). Life tasks, self-concept ideals, and cognitive strategies in a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, K. L., Finkel, E. J., & Kumashiro, M. (2019). Creativity and romantic passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(6), 919–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, K. L., & Impett, E. A. (2021). What fuels passion? An integrative review of competing theories of romantic passion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(8), e12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. L., & Liao, W. T. (2021). Emotion regulation in close relationships: The role of individual differences and situational context. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 697901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C. M., & Ruhl, H. (2014). Friendship and romantic stressors and depression in emerging adulthood: Mediating and moderating roles of attachment representations. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, M. A., Allen, J. P., Womack, S. R., Loeb, E. L., Stern, J. A., & Pettit, C. (2023). Characterizing emotional support development: From adolescent best friendships to young adult romantic relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(2), 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Matos Fernandes, C. A., Bakker, D. M., Flache, A., & Brouwer, J. (2025). How do personality traits affect the formation of friendship and preference-for-collaboration networks? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 42(2), 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSousa, D. A., & Cerqueira-Santos, E. (2012). Relacionamentos de amizade e coping entre jovens adultos. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 28, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadou, D., & Stalikas, A. (2012). Values in action inventory of strengths (VIA-IS). In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Psychometric instruments in Greece (2nd ed., p. 543). Pedio. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G. J. O. (2002). The new science of intimate relationships. John Wiley & Son. [Google Scholar]

- Galanaki, E. P., Nelson, L. J., & Antoniou, F. (2023). Social withdrawal, solitude, and existential concerns in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 11(4), 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2022). Character growth following collective life events: A study on perceived and measured changes in character strengths during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Personality, 36(4), 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, M., Viejo, C., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2019). Well-being and romantic relationships: A systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habenicht, S., & Schutte, N. S. (2023). The impact of recognizing a romantic partner’s character strengths on relationship satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(3), 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjat, M., & Moyer, A. (2017). The Psychology of friendship. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karremans, J. C., & Van Lange, P. A. (2008). Forgiveness in personal relationships: Its malleability and powerful consequences. European Review of Social Psychology, 19(1), 202–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., Blalock, D. V., Young, K. C., Machell, K. A., Monfort, S. S., McKnight, P. E., & Ferssizidis, P. (2018). Personality strengths in romantic relationships: Measuring perceptions of benefits and costs and their impact on personal and relational well-being. Psychological Assessment, 30(2), 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, V. A., Perez, J. C., Reise, S. P., Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2022). Friendship network satisfaction: A multifaceted construct scored as a unidimensional scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(2), 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, K. A., Obeldobel, C. A., Kochendorfer, L. B., & Gastelle, M. (2023). Attachment security and character strengths in early adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(9), 2789–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K. (2024). Factorization of person response profiles to identify summative profiles carrying central response patterns. Psychological Methods, 29(4), 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, V., Curran, T., Celen-Demirtas, S., Karwin, S., Bryant, K., Andrews, B., & Duffy, R. (2019). Commitment among unmarried emerging adults: Meaning, expectations, and formation of relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(4), 1317–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordoutis, P., & Manesi, Ζ. (2012). Love components, duration and sexual intercourse in dating relationships. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 19(1), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langheit, S., & Poulin, F. (2022). Developmental changes in best friendship quality during emerging adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(11), 3373–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, D., LaPorte, E., & Kelley, K. (2023). Moral cognition in adolescence and emerging adulthood. In L. J. Crockett, G. Carlo, & J. E. Schulenberg (Eds.), APA handbook of adolescent and young adult development (pp. 123–138). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Bareli, Y. (2014). Strengths deployment as a mood-repair mechanism: Evidence from a diary study with a relationship exercise group. Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(6), 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, G., Cnaan, R. A., & Boehm, A. (2015). National culture and prosocial behaviors: Results from 66 countries. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(5), 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R. E. (2025). Self-reported character strengths over 21 years. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 10(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J. K., Vennum, A. V., Ogolsky, B. G., & Fincham, F. D. (2014). Commitment and sacrifice in emerging adult romantic relationships. Marriage & Family Review, 50(5), 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(4), 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabila, V., & Gunawan, M. C. (2023). The relationship between the triangular theory of love by Sternberg and romantic relationship satisfaction in the emerging adulthood. European Journal of Psychological Research, 10(1), 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, R. M. (2018). Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners. Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Noronha, A. P. P., & Campos, R. R. F. D. (2018). Relationship between character strengths and personality traits. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 35(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, D. L. (2017). Maintaining long-lasting friendships. In M. Hojjat, & A. Moyer (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (pp. 267–282). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Pezirkianidis, C., Karakasidou, E., Stalikas, A., Moraitou, D., & Charalambous, V. (2020a). Character strengths and virtues in the Greek cultural context. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 25(1), 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezirkianidis, C., Stalikas, A., & Galanakis, M. (2020b). Character strengths and their role in relationship quality: Evidence from Greek adults. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 17(2), 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Ros-Morente, A., Mora, C. A., Nadal, C. T., Belled, A. B., & Berenguer, N. J. (2018). An examination of the relationship between emotional intelligence, positive affect and character strengths and virtues. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 34(1), 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, W., Proyer, R. T., Harzer, C., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2010). Values in action inventory of strengths (VIA-IS). Journal of Individual Differences, 31(3), 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaty, T. L. (2013). Analytic hierarchy process. In S. I. Gass, & M. C. Fu (Eds.), Encyclopedia of operations research and management science (pp. 52–64). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L., Fraley, C., Murphy, T. B., & Raftery, A. E. (2023). Model-based clustering, classification, and density estimation using mclust in R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seffrin, P. M., Giordano, P. C., Manning, W. D., & Longmore, M. A. (2009). The influence of dating relationships on friendship networks, identity development, and delinquency. Justice Quarterly, 26(2), 238–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimai, S., Otake, K., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2006). Convergence of character strengths in American and Japanese young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, S., & Connolly, J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokowski, P., Sorokowska, A., Karwowski, M., Groyecka, A., Aavik, T., Akello, G., Alm, C., Amjad, N., Anjum, A., Asao, K., Atama, C. S., Atamtürk Duyar, D., Ayebare, R., Batres, C., Bendixen, M., Bensafia, A., Bizumic, B., Boussena, M., Buss, D. M., … Mora, E. C. (2021). Universality of the triangular theory of love: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the triangular love scale in 25 countries. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(1), 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanou, G. (2012). Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Perception-partner ideal discrepancies, attributions, and expectations. Psychology, 3(2), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(3), 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, K. H., Brewster, K. L., & Holway, G. V. (2019). Sexual and romantic relationships in young adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wal, R. C., Litzellachner, L. F., Karremans, J. C., Buiter, N., Breukel, J., & Maio, G. R. (2024). Values in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 50(7), 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L. (2019). Good character is what we look for in a friend: Character strengths are positively related to peer acceptance and friendship quality in early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(6), 864–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L., Pindeus, L., & Ruch, W. (2021). Character strengths in the life domains of work, education, leisure, and relationships and their associations with flourishing. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 597534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L. C., Horton, C., Kaufman, R., Rodriguez, A., & Kaufman, V. A. (2024). Heterogeneity in happiness: A latent profile analysis of single emerging adults. PLoS ONE, 19(10), 0310196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, T. E., Raby, K. L., Ruiz, S. K., Martin, J., & Roisman, G. I. (2018). Adult attachment representations and the quality of romantic and parent–child relationships: An examination of the contributions of coherence of discourse and secure base script knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 54(12), 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, N. K., Beckmeyer, J. J., & Jamison, T. B. (2024). Exploring the associations between being single, romantic importance, and positive well-being in young adulthood. Family Relations, 73(1), 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waworuntu, E. C., Kainde, S. J., & Mandagi, D. W. (2022). Work-life balance, job satisfaction and performance among millennial and Gen Z employees: A systematic review. Society, 10(2), 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M., & Ruch, W. (2012). The role of character strengths in adolescent romantic relationships: An initial study on partner selection and mates’ life satisfaction. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Single | In a Relationship | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skewness, Kurtosis | Mean | SD | Skewness, Kurtosis | |

| Love components a | ||||||

| Intimacy | - | - | - | 8.18 | 0.68 | −1.13, −1.68 |

| Commitment | - | - | - | 7.67 | 1.12 | −0.98, −0.37 |

| Passion | - | - | - | 7.80 | 1.04 | −0.56, −0.74 |

| Friendships b | ||||||

| Closeness | 5.28 | 0.72 | −1.22, 0.93 | 5.02 | 0.87 | −1.07, 0.78 |

| Socializing | 4.61 | 1.05 | −0.76, 0.31 | 4.14 | 1.12 | −0.18, −0.80 |

| Virtues c | ||||||

| Knowledge | 3.64 | 0.81 | −0.32, −0.62 | 3.72 | 0.81 | −0.36, −0.86 |

| Interpersonal | 4.01 | 0.39 | −0.22, −0.25 | 4.03 | 0.43 | −0.31, −0.57 |

| Intellect | 3.83 | 0.42 | −0.10, −0.46 | 3.85 | 0.45 | −0.16, −0.35 |

| Transcendence | 3.71 | 0.64 | −0.08, −0.97 | 3.74 | 0.59 | −0.00, −0.69 |

| Restraint | 3.73 | 0.53 | −0.18, −0.84 | 3.83 | 0.51 | −0.50, −0.35 |

| N Profiles | AIC | AWE | BIC | CLC | KIC | Prob Min | Prob Max | Entropy | C-RIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1743 | 1957 | 1811 | 1713 | 1760 | 0.900 | 0.949 | 0.776 | 0.870 |

| 3 | 1589 | 1883 | 1682 | 1546 | 1612 | 0.901 | 0.933 | 0.834 | 0.809 |

| 4 | 1481 | 1856 | 1600 | 1427 | 1511 | 0.692 | 0.934 | 0.799 | 0.800 |

| 5 | 1410 | 1865 | 1553 | 1343 | 1445 | 0.803 | 0.911 | 0.788 | 0.803 |

| N Profiles | AIC | AWE | BIC | CLC | KIC | Prob Min | Prob Max | Entropy | C-RIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtue profiles | |||||||||

| 2 | 3286 | 3511 | 3352 | 3250 | 3308 | 0.967 | 0.978 | 0.913 | 0.870 |

| 3 | 3209 | 3517 | 3299 | 3238 | 3238 | 0.893 | 0.975 | 0.881 | 0.856 |

| 4 | 3111 | 3502 | 3225 | 3147 | 3147 | 0.847 | 0.982 | 0.890 | 0.809 |

| 5 | 3036 | 3511 | 3174 | 2079 | 3047 | 0.840 | 0.979 | 0.895 | 0.802 |

| Love profiles | |||||||||

| 2 | 1111 | 1249 | 1166 | 1112 | 1144 | 0.885 | 0.976 | 0.839 | 0.957 |

| 3 | 999 | 1165 | 1048 | 973 | 1016 | 0.912 | 0.964 | 0.895 | 0.952 |

| 4 | 938 | 1152 | 1000 | 903 | 903 | 0.770 | 0.972 | 0.889 | 0.938 |

| 5 | 944 | 1206 | 1020 | 901 | 901 | 0.477 | 0.955 | 0.708 | 0.775 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniilidou, A.; Nerantzaki, K. Character Virtues in Romantic Relationships and Friendships During Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Approach. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040091

Daniilidou A, Nerantzaki K. Character Virtues in Romantic Relationships and Friendships During Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Approach. Psychology International. 2025; 7(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040091

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniilidou, Athena, and Katerina Nerantzaki. 2025. "Character Virtues in Romantic Relationships and Friendships During Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Approach" Psychology International 7, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040091

APA StyleDaniilidou, A., & Nerantzaki, K. (2025). Character Virtues in Romantic Relationships and Friendships During Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Approach. Psychology International, 7(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040091