Abstract

This mixed-methods study examined the influence of physical activity on mental health and sleep quality among 78 long-distance South Asian caregivers of older adults. As caregiving demands grow globally, long-distance caregivers face unique stressors intensified by cultural obligations and geographic separation. Quantitative analyses revealed a significant inverse relationship between depressive symptoms and sleep quality (p < 0.001), with caregivers experiencing frequent depressive feelings and reporting fewer hours of sleep. Although the relationship between physical activity and sleep did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0903), a positive trend was observed: caregivers engaging in regular activity (≥5 days/week) reported better sleep. Depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with reduced physical activity (p = 0.0378). Qualitative findings enriched these results, illustrating how walking, yoga, and community sports were used to manage stress, enhance mood, and promote sleep. Participants emphasized the therapeutic value of outdoor environments and culturally familiar activities in coping with emotional strain. The findings suggest that physical activity plays an independent and protective role in caregiver well-being. Culturally responsive interventions that promote accessible physical activity may enhance mental health and sleep outcomes in this population, supporting sustainable caregiving and informing policy development for underrepresented caregiver groups.

1. Introduction

The global demographic landscape is rapidly changing, with a significant increase in the aging population across various regions (Gu et al., 2021; Maestas et al., 2023; Clark et al., 2020). This trend is particularly prominent in South Asian communities, where socio-cultural norms and family structures often place the responsibility of caregiving on family members (Gupta & Pillai, 2002). As life expectancy increases due to advances in healthcare, the number of older adults requiring care continues to rise, thereby escalating the demand for caregivers (Vinarski & Halperin, 2020; Ribeiro et al., 2022; Spillman et al., 2021; Mar, 2020). This shift poses unique challenges, not only in terms of physical caregiving demands but also in addressing the mental and emotional health of the caregivers themselves (Spillman et al., 2021; Yu-Nu et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2021).

In South Asian communities, caregiving is traditionally seen as a familial duty, with multiple generations often living under one roof (Raj et al., 2021; Gill, 2020; Ng & Indran, 2021). This arrangement, while supportive in many ways, can lead to significant physical, emotional, and financial stress on the caregivers (Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020). The need to balance work, personal life, and caregiving responsibilities can strain mental health and disrupt sleep patterns, leading to a decrease in overall well-being (Raj et al., 2021; Gill, 2020; Ng & Indran, 2021; Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020).

Despite the critical role of caregivers and the challenges they face, there is a notable gap in research at the intersection of physical activity, mental health, and caregiving within South Asian contexts. Existing studies predominantly focus on Western populations and may not fully capture the cultural nuances and specific challenges faced by South Asian caregivers. Furthermore, while the benefits of physical activity on general health are well-documented (Schuch & Vancampfort, 2021; Jacob et al., 2020; Herbert et al., 2020; Callow et al., 2020), its specific impact on caregivers’ mental health and sleep quality remains underexplored.

Stress, anxiety, and depression are widespread among caregivers, yet these mental health concerns often remain unaddressed in South Asian communities due to cultural stigma and limited mental health awareness (Ng & Indran, 2021; Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020). Physical activity, known for its positive effects on mental health in the general population (Schuch & Vancampfort, 2021; Jacob et al., 2020), could offer substantial benefits to caregivers. However, research that is culturally specific to South Asian communities is essential to understanding the effectiveness and feasibility of physical activity interventions within this group, considering their unique cultural and societal contexts.

1.1. Study Aims and Objectives

This study aims to bridge this research gap by focusing on South Asian caregivers of older adults, examining how engaging in physical activity affects their mental health and sleep quality. The objectives of the study are:

- Assess the Mental Health Impact: To evaluate how regular physical activity influences the mental health of caregivers, particularly in managing stress and reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety.

- Explore Sleep Quality: To investigate the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality among caregivers, understanding how exercise can help alleviate sleep disturbances commonly reported in this population.

- Cultural and Contextual Adaptations: To consider the cultural attitudes towards physical activity and caregiving in South Asian communities, identifying barriers and facilitators to engaging in regular physical exercise.

By achieving these objectives, the study not only contributes to the existing body of knowledge but also aids in developing culturally appropriate strategies to enhance the well-being of caregivers. Addressing these aspects is crucial for creating supportive environments that promote the health of caregivers, thereby improving the quality of care provided to older adults.

1.2. Literature Review

Caregiving, while often rewarding, poses significant challenges that impact both physical and mental health (Spillman et al., 2021; Mar, 2020). Numerous studies have documented the extensive burdens faced by caregivers, with chronic stress being a predominant issue (Spillman et al., 2021; Yu-Nu et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2021). Caregivers frequently experience higher levels of stress and depression compared to non-caregivers (Lillekroken et al., 2023). This heightened stress can lead to serious health consequences, including increased risks of cardiovascular diseases and a generally poorer quality of life.

The mental health challenges are particularly severe. Depression, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion are commonly reported among caregivers (Spillman et al., 2021; Mar, 2020; Hossain et al., 2020). Further, caregivers often suffer from depressive symptoms at rates substantially higher than their non-caregivers (Lillekroken et al., 2023). These mental health issues are compounded by the lack of adequate sleep, as caregivers struggle with frequent nighttime awakenings due to caregiving duties, leading to sleep deprivation and its associated risks (Raj et al., 2021; Gill, 2020).

Physical health also deteriorates under the strain of caregiving (Spillman et al., 2021; Yu-Nu et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2021). Caregivers frequently report neglecting their own healthcare needs, engaging less in preventive health behaviors, and having less time for exercise (Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020). The physical demands of caregiving, such as lifting and assisting the care recipient, can lead to physical injuries, including back pain and muscle strains, which further exacerbate stress and health decline (Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020).

Physical activity is known to reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, and has a positive impact on mental health by reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Herbert et al., 2020; Callow et al., 2020; Pascoe et al., 2020). Regular engagement in physical activity can also improve sleep quality, enhance self-esteem, and provide a respite from caregiving responsibilities, thereby reducing overall caregiver burden (Wang, 2024; Cui, 2024). Caregivers who engaged in regular physical activity reported better mental health outcomes than those who did not (Tam et al., 2025; Sibalija et al., 2020). The physiological benefits, such as improved endurance, strength, and flexibility, also assist caregivers in performing their duties more efficiently, reducing the risk of injury and physical fatigue (Tam et al., 2025; Sibalija et al., 2020; Prado et al., 2020). Moreover, the psychological benefits of exercise, including the release of endorphins, act as a natural combatant to stress and depression (Callow et al., 2020; Wang, 2024; Cui, 2024). The social aspect of certain types of exercise, such as community walks, provides essential social support, which is crucial for caregivers who may otherwise feel isolated (Tam et al., 2025; Sibalija et al., 2020; Odzakovic et al., 2020; Koay & Dillon, 2020; Iqbal et al., 2023).

In South Asian communities, caregiving is deeply influenced by cultural norms and values and is often not socially defined by the term ‘caregiver’. The concept of sewa (selfless service) is ingrained in many South Asian cultures, often leading to an expectation that family members will care for aging relatives (Varghese et al., 2021; Sathish, 2023; Ahmad, 2020). This cultural expectation can both support and strain caregivers, as the responsibility is honored but may also be overwhelming without additional support from the community or health services (Hossain et al., 2020; Gill, 2020).

Access to physical activity is another area affected by cultural considerations. In many parts of South Asia, there are significant gender disparities in access to exercise and recreational activities (Lillekroken et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Bhan et al., 2020). Women, who are often the primary caregivers, may face greater restrictions due to cultural norms regarding appropriate behavior and mobility, which can limit their ability to engage in physical activity outside the home (Bhan et al., 2020; Lasker & Hossain, 2023). Additionally, the urban design and availability of safe, accessible spaces for physical activity can vary greatly. In many South Asian cities, a lack of infrastructure such as sidewalks, parks, and recreational facilities can impede regular physical activity (Parida et al., 2022; Sahakian et al., 2020; Lakshyayog, 2023; Kajosaari & Laatikainen, 2020). Moreover, socioeconomic factors often influence the availability of leisure time for exercise, particularly among those who might be balancing multiple jobs along with caregiving responsibilities (Bhan et al., 2020; Lasker & Hossain, 2023; Landwehr, 2021). Importantly, these cultural norms and perceptions around gender roles and physical activity often persist even after migration. South Asian immigrants in Western countries, including the United States, may continue to face similar cultural barriers to engaging in physical activity, particularly among women caregivers (Gill, 2020; Hossain et al., 2020). This highlights the need for culturally sensitive health promotion strategies.

There is a clear link between the physical and mental health challenges faced by caregivers and the beneficial effects of physical activity. However, cultural nuances in South Asian communities require that interventions be tailored to meet the specific needs and circumstances of caregivers. Understanding these cultural factors is crucial for designing effective, accessible, and sustainable physical activity programs that can truly benefit caregivers. Thus, there is a pressing need for further research that directly addresses these cultural considerations and develops targeted strategies to encourage physical activity among caregivers in South Asian contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a mixed-methods concurrent nested design, prioritizing quantitative data to explore the impact of physical activity on the mental health and sleep quality of South Asian caregivers. A qualitative component was embedded within the quantitative data collection and analysis to provide deeper insights into the personal experiences and cultural contexts of caregiving. This approach capitalized on the strengths of both methodologies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the caregiving experience. The quantitative component measured and analyzed key health outcomes, while the qualitative component offered context through focus group discussions.

2.2. Participants

The study included 78 South Asian caregivers residing in Omaha, Nebraska, United States. Participants included individuals from Nepali, Bhutanese, Indian, Burmese, Myanmarese, Karen, and Hindi-speaking communities, reflecting a diverse South Asian caregiver population. They were recruited through snowball sampling methods involving community centers, online forums, and local non-governmental organizations. The inclusion criteria for participation were as follows:

- South Asian adults aged 19 or older.

- Actively providing unpaid support to an adult aged 50+ through social/emotional contact, caregiving roles, financial support, and/or meal/transportation assistance.

- Ability to communicate in English or a South Asian language (e.g., Nepali, Burmese, Hindi).

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Quantitative Data Collection

Quantitative data were collected from 78 participants through both online and in-person surveys. The questionnaire included items on demographics, sleep patterns, caregiving roles, physical activity levels, and self-reported mental health perceptions. Recruitment was conducted via community centers, local universities, religious institutions, and online advertisements.

2.3.2. Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data were obtained through five focus group sessions, each consisting of 3 to 6 caregivers. Participants for the focus groups were drawn from survey respondents; all individuals who completed the survey were invited to participate in a focus group if they expressed interest. The sessions were guided by a semi-structured interview protocol that focused on participants’ experiences of physical activity, the impact of caregiving on their health, and cultural beliefs surrounding caregiving. Each focus group was conducted via Zoom, facilitated by bilingual researchers to accommodate language preferences, and lasted approximately 90 min. Informed consent was obtained, and sessions were audio and video recorded for analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using R statistical software version 4.5.1. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic information and general health data. Inferential statistics, including Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Pearson correlation coefficients, and effect sizes (η2), were applied to examine the relationships between physical activity, depressive symptoms, and sleep quality (Landwehr, 2021; Benesty et al., 2009). For the purposes of analysis, the following categorical groupings were used:

- Physical Activity Frequency: Grouped into three categories based on days per week participants walked for at least 10 min (1) Less than 2 days, (2) 2–4 days, and (3) 5 or more days.

- Depressive Symptoms: Based on participant self-report, responses were grouped into (1) None of the time, (2) Some of the time, and (3) Most of the time.

- Sleep Quality: Measured as an average self-reported hours of sleep per night (continuous) and used as the primary outcome in ANOVA comparisons across depressive symptoms and physical activity levels.

Qualitative data from five focus groups (n = 21) were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis. Transcripts were manually cleaned for accuracy and uploaded to MAXQDA for coding and analysis. A codebook was developed based on the semi-structured interview guide and an initial review of the data. Coding and theme development followed an iterative and systematic process, with regular refinement of codes to ensure consistency and analytic depth. Credibility and trustworthiness were enhanced through multiple transcript reviews, detailed memo writing, and adherence to structured coding procedures. The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings provided a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex interactions between physical activity, mental health, and sleep quality in South Asian caregivers.

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 78 South Asian caregivers aged 24 to 68 years, with a gender distribution of 62% male (n = 48) and 38% female (n = 30). Most caregivers were children of care recipients (47%), followed by grandchildren (27%) and other relatives or friends (26%). A subset of 21 survey respondents also participated in follow-up focus group discussions. Demographic characteristics of both the full survey sample and the focus group participants are presented in Table 1 to allow for comparison between the two groups. Importantly, none of the caregivers in the sample resided with the care recipient, confirming their status as long-distance caregivers.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants (n = 78) and Focus Group Participants (n = 21).

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality

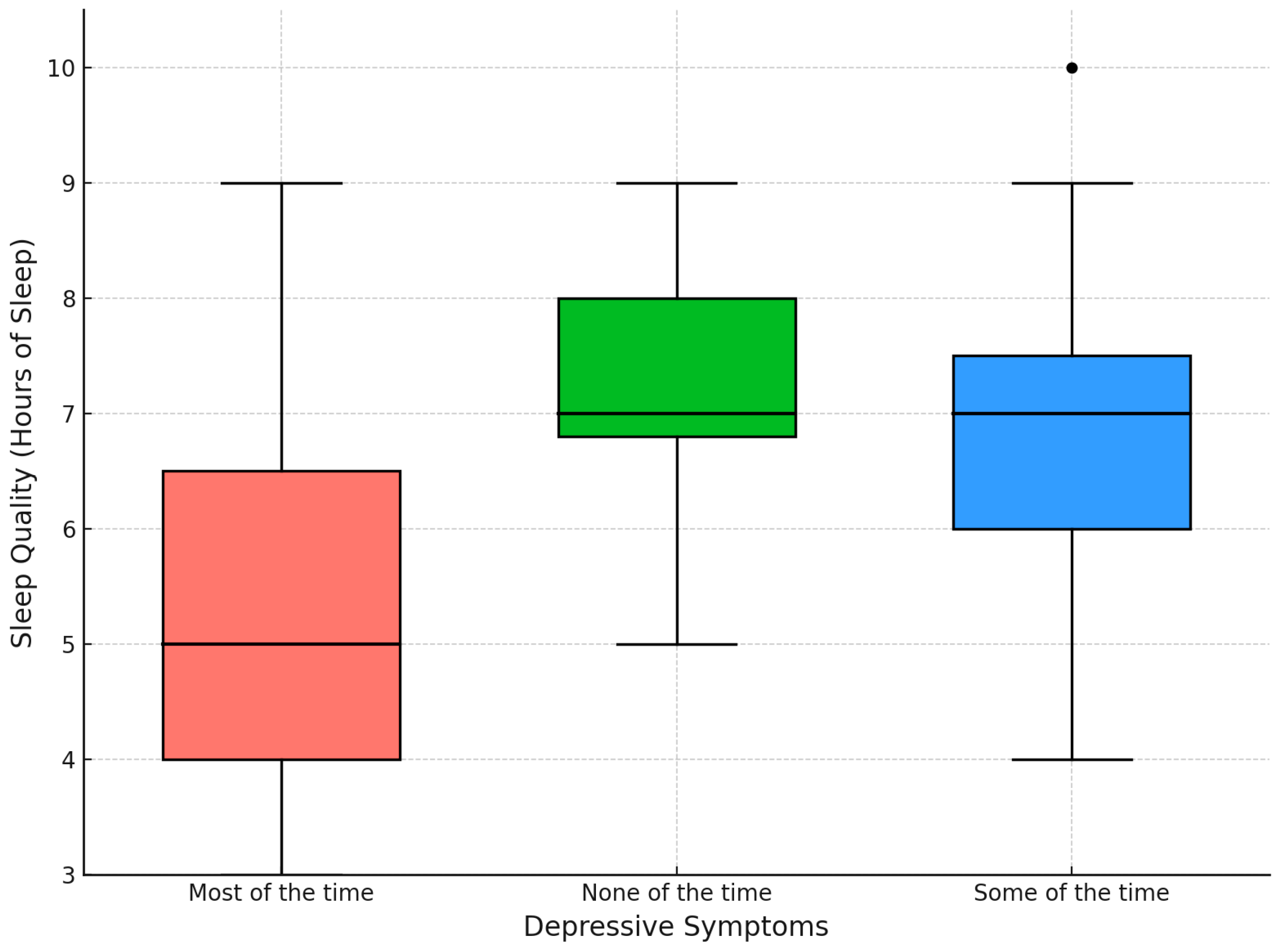

A one-way ANOVA (Table 2) showed a significant effect of depressive symptoms on sleep quality (F(2, 75) = 11.28, p < 0.001). The effect size for this relationship was η2 = 0.23, indicating a large effect based on conventional benchmarks. Caregivers experiencing depressive symptoms “most of the time” reported significantly fewer hours of sleep compared to those experiencing depressive symptoms “some of the time” or “none of the time.” This finding indicates that depressive symptoms are strongly associated with lower sleep quality. The relationship is visually illustrated in Figure 1 where the median hours of sleep decrease as depressive symptoms increase.

Table 2.

ANOVA Results for Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality.

Figure 1.

Sleep Quality by Depressive Symptoms.

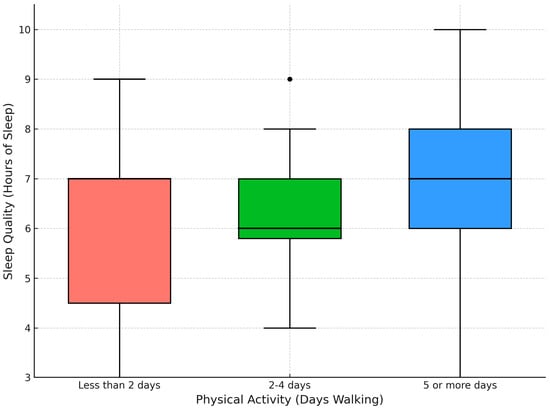

3.1.2. Effect of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality

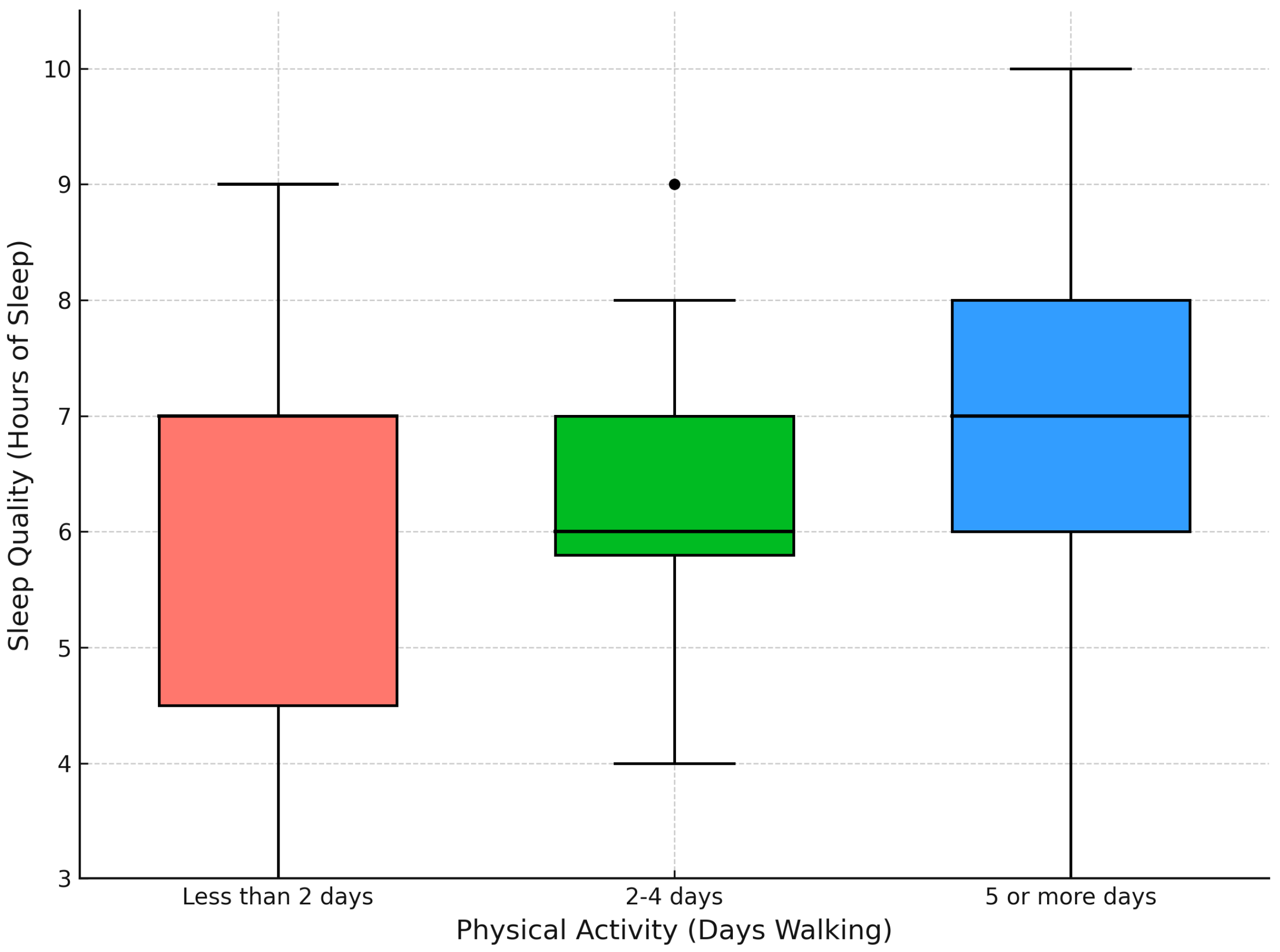

The effect of physical activity on sleep quality was also examined using an ANOVA as shown in Table 3. While the relationship did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0903), the observed trend suggests a potential positive association warranting further study. The effect size for this relationship was η2 = 0.035, indicating a small effect based on conventional benchmarks. Caregivers who engaged in physical activity for 5 or more days per week reported better sleep quality compared to those engaging in fewer days of activity. This trend can be observed in Figure 2, which shows that higher levels of physical activity tend to be associated with more hours of sleep.

Table 3.

ANOVA Results for Physical Activity and Sleep Quality.

Figure 2.

Sleep Quality by Level of Physical Activity.

Additionally, a Pearson correlation analysis revealed a weak positive correlation (r = 0.193) between the number of days caregivers walked for at least 10 min per week and their reported hours of sleep. This suggests that higher physical activity might slightly improve sleep quality, though the relationship is weak.

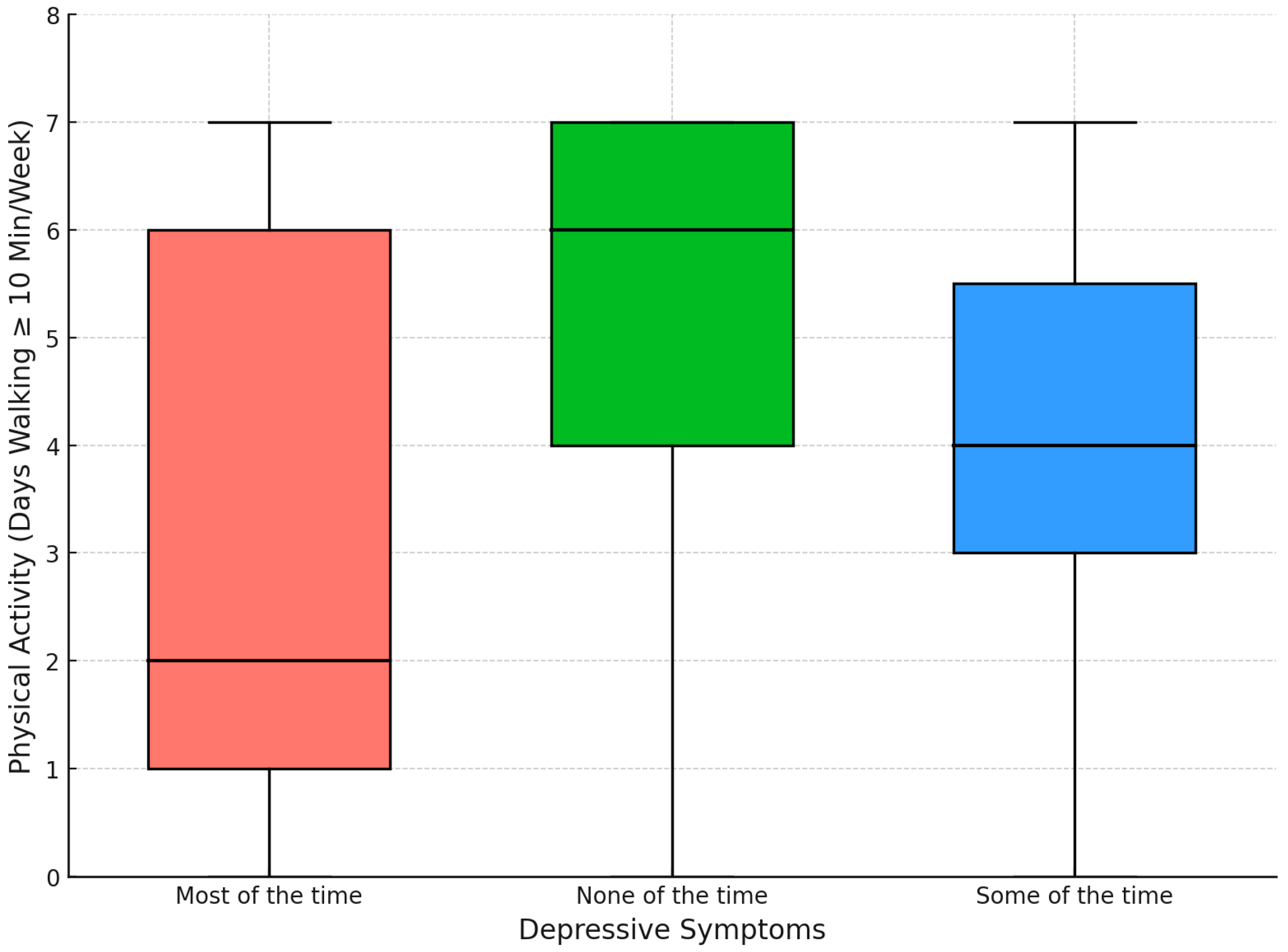

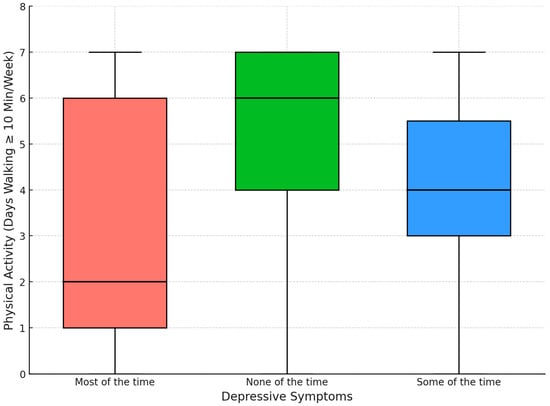

3.1.3. Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Physical Activity

A separate ANOVA analysis (Table 4) revealed a significant relationship between depressive symptoms and physical activity (F(2, 75) = 3.424, p = 0.0378). The effect size for this relationship was η2 = 0.072, indicating a moderate effect based on conventional benchmarks. Caregivers who reported depressive symptoms “most of the time” engaged in fewer days of physical activity compared to those who experienced fewer or no depressive symptoms. This finding is clearly visualized in Figure 3, where the number of days walking for at least 10 min per week decreases with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 4.

ANOVA Results for Depressive Symptoms and Physical Activity.

Figure 3.

Physical Activity by Depressive Symptoms.

3.2. Qualitative Results

Walking emerged as a recurring theme across the focus groups, mentioned in 4 out of 5 groups and accounting for approximately 18% of all coded comments. Caregivers frequently described walking as a vital outlet for stress relief and mental rejuvenation. One participant noted, “And whenever I feel stressed out, or maybe, if I have a lot of work to do, and I don’t know where to start, I just go out for a walk in my community so that you know, I can feel fresh and calm after going for a walk.” Community features such as walking trails were frequently mentioned, with another caregiver stating, “I live in a community where, you know, there are walking trails, that make me feel close to nature and relaxed,” indicating that environmental factors significantly enhance the therapeutic effects of walking.

The availability of play areas and engagement in physical activities was another commonly discussed topic, appearing in 3 of the 5 focus groups and representing roughly 12% of total comments. One caregiver shared, “Actually, in our neighborhood, there is no place to play. We love to play Cricket. Yeah. That one thing we have the priority.” Another added, “If I play more time before sleeping, I can get good sleep.” These narratives underscore the positive impact of physical activities on sleep quality, particularly when performed in the evening.

Yoga and other physical activities were also described as strategies for managing stress, with references appearing in three focus groups and comprising about 10% of the coded data. A participant mentioned, “Maybe attending the Yoga Sessions online or in person can be helpful in leading a stress-free life.” Additionally, the emotional toll of geographic separation from care recipients was a recurrent concern, emerging in all 5 focus groups. One caregiver expressed, “I feel stressed out for being far distant from the care recipient and feel bad about leaving them alone,” highlighting how distance can contribute to emotional burden.

Changes in environment and isolation were recurring factors contributing to feelings of depression and anxiety among caregivers. One caregiver reflected, “When I first came to the US, it was so silent that I felt depressed.” Another discussed the complications of sharing emotional burdens, stating, “Sometimes when I share my problems with the care recipient, they get anxious, so I will not share with them.” This highlights the complex dynamics of caregiver-care-recipient relationships and their impact on mental health.

Caregivers emphasized the critical role of sleep in maintaining their health and caregiving performance. As one participant briefly put it, “I think for us sleep is the most important thing in our life. And I think we should probably sleep like six to eight hours per night.” Another caregiver who reported getting quality sleep shared, “I’m getting very good quality sleep, so I have been giving my time to my parents, and it doesn’t affect my caregiving ability.”

These qualitative insights provide a deeper understanding of caregivers’ lived experiences, particularly within the context of long-distance caregiving. The data highlight the integral role of physical activity and environmental factors in managing stress, depressive feelings, and sleep disturbances; challenges that are often intensified by the emotional strain of being geographically separated from care recipients. Walking, yoga, and access to recreational spaces not only served as coping mechanisms but also helped caregivers maintain a sense of emotional balance and connection despite the distance. The qualitative findings not only enrich the quantitative results but also offer contextually rich perspectives that are essential for developing comprehensive, culturally responsive interventions for long-distance caregivers.

3.3. Summary of Key Findings

The research conducted on long-distance South Asian caregivers of older adults provides significant insights into the impact of physical activity on their mental health and sleep quality. Both quantitative and qualitative analyses contribute to a comprehensive understanding of how lifestyle factors intersect with caregiving responsibilities.

3.3.1. Quantitative Findings

- Depressive Feelings and Sleep: The analysis revealed a significant relationship between depressive feelings and reduced sleep quality. Caregivers reporting feelings of depression ‘Most of the time’ experienced fewer hours of sleep compared to those feeling depressed ‘Some of the time’ or ‘None of the time’.

- Physical Activity and Sleep: While the relationship between the number of days caregivers engaged in physical activity (specifically walking for at least 10 min) and sleep quality did not reach statistical significance, there was a positive trend suggesting that more frequent physical activity may be associated with better sleep quality.

- Independent Effects: There were no significant interaction effects between depressive feelings and physical activity on sleep quality, indicating that each has an independent impact on sleep.

3.3.2. Qualitative Findings

- Therapeutic Role of Physical Activity: Caregivers extensively described physical activity, especially walking, as a vital mechanism for stress relief and mental rejuvenation. Walking trails and interaction with nature were particularly valued for their calming effects.

- Community and Recreational Activities: The availability of community play areas and engagement in group activities like playing cricket or participating with children were highlighted as enhancing both physical and mental well-being, and indirectly improving sleep quality.

- Coping with Stress and Depression: Activities like yoga and other forms of exercise were cited as important for managing stress and depressive symptoms, particularly in the context of the challenges posed by caregiving and geographical separation from care recipients.

- Importance of Sleep: The qualitative narratives emphasized that maintaining adequate sleep is crucial for effective caregiving. Caregivers noted that better sleep quality, facilitated by physical activity, significantly improves their caregiving abilities.

3.4. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

Quantitatively, the significant association between self-reported depressive feelings and reduced hours of sleep underscores the critical role of mental health in sleep quality. Qualitatively, caregivers’ narratives about the stress-relieving properties of walking and other physical activities explain how these practices contribute to better mental health and, indirectly, to improved sleep.

For instance, the quantitative data showed a weak positive correlation between the number of days caregivers walked and their hours of sleep. This finding is reflected in qualitative comments where participants reported increased calmness and stress reduction after walking, particularly in environments that promote a connection with nature. These activities were especially meaningful given the emotional strain of being physically distant from their care recipients, a dynamic unique to long-distance caregiving.

Additionally, the absence of significant interaction effects in the quantitative analysis between depressive feelings and physical activity on sleep quality suggests that each factor independently contributes to sleep. Qualitative insights further support this, as caregivers described using physical activity to manage depressive feelings stemming not only from caregiving responsibilities, but also from feelings of guilt, helplessness, and isolation associated with geographic separation from their loved ones.

The integration of these findings highlights the multifaceted role of physical activity in enhancing the well-being of long-distance caregivers. Unlike co-residential caregivers who provide hands-on care, long-distance caregivers often experience heightened emotional stress due to their limited physical proximity and inability to respond quickly to care needs. In this context, regular physical activity serves as a critical buffer against emotional exhaustion, while also promoting better sleep and mental health.

These insights are essential for developing targeted interventions that support the unique experiences of long-distance caregivers, particularly within the cultural context of South Asian communities. This study underscores the importance of integrating physical activity into daily routines as a strategic approach to mitigating the specific emotional and psychological challenges of long-distance caregiving, with broader implications for community health programming and culturally tailored policy efforts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

The findings from this study provide insights into the effects of physical activity on the mental health and sleep quality of South Asian caregivers. The quantitative analysis revealed a clear relationship between depressive feelings and decreased sleep quality, affirming the vulnerability of caregivers to mental health challenges. This is consistent with the broader caregiving literature which often documents high levels of stress and mental health problems among caregivers (del-Pino-Casado et al., 2019; Cheval et al., 2022; Su et al., 2021; Herring et al., 2018; King et al., 2002). The positive trend between physical activity and improved sleep quality observed in this study, although not reaching conventional levels of statistical significance, suggests a beneficial role of exercise that warrants further exploration.

Interestingly, the lack of significant interaction effects between depressive feelings and physical activity on sleep quality suggests that these factors may independently affect sleep. This independence is especially important when considering interventions for long-distance caregivers, who often face emotional distress stemming from geographic separation and limited control over day-to-day caregiving. The findings suggest that even when caregivers are not in close physical proximity to their care recipients, physical activity can still play a meaningful role in enhancing sleep and reducing emotional burden. In other words, physical activity may serve as a protective factor regardless of mental health status or proximity to the care recipient, underscoring its potential value in interventions designed for geographically distant caregivers.

The qualitative results enriched these findings by providing context and depth to the numerical data. Caregivers in this South Asian, long-distance caregiving sample spoke of physical activity as a valuable outlet for managing stress, emotional guilt, and disconnection—challenges that are often compounded by cultural expectations of caregiving and family duty. Narratives reflected the dual pressures of honoring familial obligations while grappling with the limitations of caregiving from afar, a tension deeply rooted in South Asian cultural norms such as sewa (selfless service).

Some participants described the value of connecting with other caregivers or engaging with culturally familiar communities, suggesting that social belonging and informal support networks also play an important role in mitigating emotional strain. Physical activity, whether walking, playing sports, or practicing yoga offered not only physical and mental relief but also a culturally acceptable and personally meaningful way to cope with caregiving stress. These subjective experiences highlight the need for culturally responsive strategies that recognize the emotional complexities faced by caregivers providing support across geographic distances.

4.2. Implications for Practice

Given the benefits of physical activity on both physical and mental health, caregiving support programs should incorporate structured physical activity components. For instance, community centers could offer specialized fitness classes for caregivers that account for their time constraints and stress levels. Programs might include yoga or any other activity which are not only physically beneficial but also provide mental relaxation.

Moreover, considering the role of physical activity in improving sleep, interventions could also focus on educating long-distance caregivers about sleep hygiene practices that integrate physical activity, such as scheduling regular exercise sessions. Healthcare providers should also be encouraged to discuss physical activity as a part of routine health check-ups with caregivers, emphasizing its importance in managing stress and maintaining mental health.

Community-based initiatives could also be beneficial, such as creating caregiver support groups centered around physical activity. These groups could serve dual purposes: providing social support, which is crucial for mental health, and promoting regular physical activity, thereby addressing two significant challenges faced by caregivers. Future research should explore the differential effects of specific types of physical activities—such as yoga, walking, or culturally familiar sports—to develop more targeted and effective interventions.

4.3. Policy Recommendations

At the policy level, these findings highlight the need for physical activity guidelines and interventions that are specifically tailored to the needs of long-distance caregivers (LDCGs), particularly those from South Asian (SA) communities. While general physical activity recommendations exist for the broader population, caregivers especially those managing care remotely face unique barriers such as irregular schedules, emotional strain from geographic separation, and culturally rooted expectations around caregiving. As such, tailored guidelines for caregivers may emphasize flexibility, low-cost or home-based activity options, and community-building components (e.g., group walks or online yoga) that accommodate these realities.

Policymakers should also consider how such guidelines can account for cultural preferences and gender norms prevalent in South Asian communities. For example, women who often serve as primary caregivers may face additional cultural or logistical barriers to engaging in public physical activity. Therefore, culturally sensitive policies might encourage gender-inclusive environments, indoor exercise opportunities, and language-accessible wellness programming in areas with large South Asian populations.

Funding allocations should support infrastructure that enables accessible and culturally appropriate physical activity. This includes developing safe walking trails, community play spaces, and public recreation centers in neighborhoods with high concentrations of South Asian residents. These investments are particularly crucial in urban immigrant communities, where opportunities for culturally relevant physical activity are often limited. Additionally, workplace policies should reflect the realities of LDCGs who may be juggling multiple roles. Organizations could implement flexible work hours and encourage virtual wellness programming that fits into caregivers’ varied schedules. Policies that normalize physical activity as a coping tool, especially for those who cannot provide hands-on care daily can foster long-term caregiver resilience and mental well-being.

Urban planning efforts should also incorporate insights from this study. Creating safe, walkable spaces and fostering community-connected environments can help reduce social isolation among caregivers and promote culturally resonant physical activity. For LDCGs who may not live with the care recipient but are deeply engaged emotionally and financially, having accessible wellness spaces within their own neighborhoods can serve as a critical support system.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

While the findings of this study are compelling, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size, although adequate for preliminary investigation, limits the generalizability of the results to all South Asian caregivers. Larger studies could provide more robust data and allow for more definitive conclusions. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures for both physical activity and mental health could introduce bias or inaccuracies in reporting, which might affect the findings. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study restricts the ability to draw causal inferences from the observed relationships. The predominance of male caregivers in our sample may reflect cultural dynamics or migration-related factors that shift caregiving roles, particularly in long-distance contexts. The age difference between survey participants and focus group participants may affect the transferability of qualitative insights to the broader sample. This study did not systematically examine caregiver gender differences, the role of care recipient health status, or the emotional effects of caregiver-care recipient dynamics such as familial appreciation. These are important aspects that may significantly influence caregiver outcomes and should be addressed in future research.

Future research should address these limitations and expand on this study’s findings. Longitudinal studies would be particularly valuable to determine causal relationships between physical activity, mental health, and sleep quality over time. Furthermore, exploring the effects of different types of physical activities and their intensity on the well-being of caregivers could tailor more specific activity recommendations. While this study emphasized physical activity, future research should also explore the roles of social connection, family dynamics, and systemic support structures in caregiver well-being, especially in the context of migration and long-distance care.

Investigating the impact of supportive interventions, such as community-based physical activity programs tailored for caregivers, could provide practical insights into effective strategies for improving caregiver health. Research could also explore the integration of technology, such as mobile health applications, to promote physical activity among caregivers, providing them with accessible tools to manage their health needs.

Additionally, studies that delve deeper into the cultural nuances affecting physical activity behaviors in different South Asian sub-communities could help in designing culturally sensitive interventions that are likely to be adopted and sustained by caregivers. Future research should consider expanding the sample size and demographic diversity to increase generalizability and capture a broader range of caregiving experiences.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of physical activity on the mental health and sleep quality of long-distance South Asian caregivers, revealing several significant insights. Findings highlighted a strong link between depressive symptoms and poor sleep quality among caregivers, with physical activity emerging as a potential contributor to improved sleep and reduced stress. Caregivers described physical activity as a key strategy for managing emotional strain and enhancing well-being. These insights underscore the importance of integrating physical activity into caregivers, supporting interventions that address both physical and mental health needs, and informing policies that promote accessible, culturally appropriate wellness resources for caregivers.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the need for comprehensive support programs tailored to long-distance caregivers from South Asian backgrounds, a population that is often underrepresented in caregiving research. Their experiences are shaped not only by geographic distance but also by cultural expectations, gender norms, and limited access to culturally resonant resources. By continuing to explore and respond to the specific needs of this group through research, community-based programs, and policy, we can better support their well-being and ultimately enhance the quality of care provided to older adults in transnational families and communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and J.B.B.; methodology, J.B.B.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C., A.S. and J.B.B.; formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, S.C.; resources, J.B.B.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and J.B.B.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, J.B.B.; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, J.B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (JHAD-RCMAR) Pilot Grant & Leo Missinne professorship awarded to J.B.B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA MEDICAL CENTER (IRB PROTOCOL #0629-22-EP, Approved on 25 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are part of an ongoing study and involve human subjects, requiring compliance with IRB protocols. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the author, J.B.B., and will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ahmad, K. (2020). Informal caregiving to chronically III older family members: Caregivers’ experiences and problems. South Asian Studies, 27(1), 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benesty, J., Chen, J., Huang, Y., & Cohen, I. (2009). Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise reduction in speech processing (pp. 1–4). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bhan, N., Rao, N., & Raj, A. (2020). Gender differences in the associations between informal caregiving and wellbeing in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(10), 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, D. D., Arnold-Nedimala, N. A., Jordan, L. S., Pena, G. S., Won, J., Woodard, J. L., & Smith, J. C. (2020). The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(10), 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheval, B., Maltagliati, S., Sieber, S., Cullati, S., Sander, D., & Boisgontier, M. P. (2022). Physical inactivity amplifies the negative association between sleep quality and depressive symptoms. Preventive Medicine, 164, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A., Jit, M., Warren-Gash, C., Guthrie, B., Wang, H. H., Mercer, S. W., Sanderson, C., McKee, M., Troeger, C., Ong, K. L., Checchi, F., Perel, P., Joseph, S., Gibbs, H. P., Banerjee, A., Eggo, R. M., & Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 working group. (2020). Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: A modelling study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(8), e1003–e1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. (2024). A015: Physical activity and social well-being in older adults: A chain-mediated model. International Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(3), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del-Pino-Casado, R., Espinosa-Medina, A., López-Martínez, C., & Orgeta, V. (2019). Sense of coherence, burden and mental health in caregiving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S. S. (2020). ‘I need to be there’: British South Asian men’s experiences of care and caring. Community, Work & Family, 23(3), 270–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D., Andreev, K., & Dupre, M. E. (2021). Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC weekly, 3(28), 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., & Pillai, V. K. (2002). Elder care giving in South Asian families: Implications for social service. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33(4), 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C., Meixner, F., Wiebking, C., & Gilg, V. (2020). Regular physical activity, short-term exercise, mental health, and well-being among university students: The results of an online and a laboratory study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 491804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, M. P., Monroe, D. C., Kline, C. E., O’Connor, P. J., & MacDonncha, C. (2018). Sleep quality moderates the association between physical activity frequency and feelings of energy and fatigue in adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M., Crossland, J., Stores, R., Dewey, A., & Hakak, Y. (2020). Awareness and understanding of dementia in South Asians: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Dementia, 19(5), 1441–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S., Di Martino, S., & Kagan, C. (2023). Volunteering in the community: Understanding personal experiences of South Asians in the United Kingdom. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(5), 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L., Tully, M. A., Barnett, Y., Lopez-Sanchez, G. F., Butler, L., Schuch, F., López-Bueno, R., McDermott, D., Firth, J., Grabovac, I., Yakkundi, A., Armstrong, N., Young, T., & Smith, L. (2020). The relationship between physical activity and mental health in a sample of the UK public: A cross-sectional study during the implementation of COVID-19 social distancing measures. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 19, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajosaari, A., & Laatikainen, T. E. (2020). Adults’ leisure-time physical activity and the neighborhood built environment: A contextual perspective. International Journal of Health Geographics, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. C., Baumann, K., O’Sullivan, P., Wilcox, S., & Castro, C. (2002). Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: A randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 57(1), M26–M36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, W. I., & Dillon, D. (2020). Community gardening: Stress, well-being, and resilience potentials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshyayog. (2023). Influence of planning on physical activity in public spaces: A case study of Chirag Delhi Ward, New Delhi, India. In Urban transformational landscapes in the city-hinterlands of Asia: Challenges and approaches (pp. 201–217). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Landwehr, J. R. (2021). Analysis of variance. In Handbook of market research (pp. 265–297). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, S. P., & Hossain, A. (2023). Public facilities for better health and urban plan. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics, 14(3), 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillekroken, D., Halvorsrud, L., Gulestø, R., & Bjørge, H. (2023). Family caregivers’ experiences of providing care for family members from minority ethnic groups living with dementia: A qualitative systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(9–10), 1625–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., & Powell, D. (2023). The effect of population aging on economic growth, the labor force, and productivity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 15(2), 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, L. (2020). Population aging in Canada: Examining the caregiving needs of the elderly. The Sociological Imagination: Undergraduate Journal, 6(1), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R., & Indran, N. (2021). Societal narratives on caregivers in Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odzakovic, E., Hellström, I., Ward, R., & Kullberg, A. (2020). ‘Overjoyed that I can go outside’: Using walking interviews to learn about the lived experience and meaning of neighbourhood for people living with dementia. Dementia, 19(7), 2199–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, D., Khan, R. R., & Lavanya, K. N. (2022). Urban built environment and elderly pedestrian accessibility: Insights from South Asia. SN Social Sciences, 2(6), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M., Bailey, A. P., Craike, M., Carter, T., Patten, R., Stepto, N., & Parker, A. (2020). Physical activity and exercise in youth mental health promotion: A scoping review. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 6(1), e000677. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, L., Hadley, R., & Rose, D. (2020). Taking time: A mixed methods study of Parkinson’s disease caregiver participation in activities in relation to their wellbeing. Parkinson’s Disease, 2020(1), 7370810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M., Zhou, S., Yi, S. S., & Kwon, S. (2021). Caregiving across cultures: Priority areas for research, policy, and practice to support family caregivers of older Asian immigrants. American Journal of Public Health, 111(11), 1920–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O., Araújo, L., Figueiredo, D., Paúl, C., & Teixeira, L. (2022). The caregiver support ratio in Europe: Esti-mating the future of potentially (Un) available caregivers. Healthcare, 10(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakian, M., Anantharaman, M., Di Giulio, A., Saloma-Akpedonu, C., Zhang, D., Khanna, R., Narasimalu, S., Favis, A. M. T., Alfiler, C. A., Narayanan, S., Gao, X., & Li, C. (2020). Green public spaces in the cities of South and Southeast Asia: Protecting needs towards sustainable well-being. The Journal of Public Space, 5(2), 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, A. (2023). Caring for the caregivers: Exploring the experiences of South Asian carers of people with dementia in Greater Manchester area [Doctoral dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University]. [Google Scholar]

- Schuch, F. B., & Vancampfort, D. (2021). Physical activity, exercise, and mental disorders: It is time to move on. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 43, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibalija, J., Savundranayagam, M. Y., Orange, J. B., & Kloseck, M. (2020). Social support, social participation, & depression among caregivers and non-caregivers in Canada: A population health perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 24(5), 765–773. [Google Scholar]

- Spillman, B. C., Allen, E. H., & Favreault, M. (2021). Informal caregiver supply and demographic changes: Review of the literature. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y., Wang, S.-B., Zheng, H., Tan, W.-Y., Li, X., Huang, Z.-H., Hou, C.-L., & Jia, F.-J. (2021). The role of anxiety and depression in the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality: A serial multiple mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 290, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, H. L., Choi, K. C., Lau, Y., Leung, L. Y. L., Chan, A. S. W., Zhou, L., Wong, E. M. L., & Ho, J. K. M. (2025). Re-engagement in physical activity slows the decline in older adults’ well-being—A longitudinal study. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 62, 00469580251314776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, M., Baruah, U., & Loganathan, S. (2021). Family caregiving in dementia in India: Challenges and emerging issues. In Dementia care: Issues, responses and international perspectives (pp. 121–136). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vinarski, H., & Halperin, D. (2020). Family caregiving in an aging society: Key policy questions. European Journal of Public Health, 30Suppl. 5, ckaa166-1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2024). Psychological well-being, spousal caregiving and utilization of healthcare services among older adults. In Advancing older adults’ well-being (pp. 145–164). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Nu, W. A. N. G., Wen-Chuin, H. S. U., & Shyu, Y. I. L. (2020). Job demands and the effects on quality of life of employed family caregivers of older adults with dementia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Research, 28(4), e99. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).