Abstract

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a spectrum of gastrointestinal disorders in which protein loss occurs through the gastrointestinal tract. One of the underlying causes is chronic inflammatory enteropathy (CIE). Conventional therapies for CIE often include diet, immunosuppressives, anti-microbials, probiotics, and, recently, fecal microbial transplantation (FMT). This case report highlights the use of lyophilized material-based FMT through oral capsules and enema in a dog with PLE and concurrent protein-losing nephropathy (PLN). The patient initially had a significantly increased dysbiosis index (DI) and required repeated FMT treatments, resulting in a positive clinical response through improvement in body weight, serum albumin concentrations, fecal scores, and normalization of the DI over time. To maintain clinical responses, FMT had to be performed monthly. Approximately 1 year after starting FMT therapy, the patient then developed an episode of acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (AHDS) associated with netF-gene-encoding Clostridium perfringens strains, after which the DI became abnormal again. The patient responded clinically well to monthly FMT treatments again, but it took several months for normalization of the DI after the AHDS episode. In summary, this case report highlights the continued use of adjunct lyophilized FMT in a dog with PLE resulting in improved clinical control over time.

1. Introduction

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a group of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders where protein loss, mainly of albumin and globulins, occurs across the enteric mucosa. Clinical signs may include vomiting, diarrhea, borborygmi, hyporexia, abdominal pain, nausea, and/or weight loss [1,2]. The most common causes are chronic inflammatory enteropathy (CIE) and lymphangiectasia [3]. Chronic inflammatory enteropathies are diagnosed based on the presence of chronic gastrointestinal signs (≥3 weeks), histopathological evidence of intestinal mucosal inflammation, and exclusion of other GI disorders (such as infectious, parasitic, mechanical, and neoplastic causes) and extra-GI disorders [3,4,5]. Chronic enteropathies (CEs) are currently subcategorized into groups based on clinical response to treatment. These include food-responsive enteropathy (FRE), immunosuppressant-responsive enteropathy (IRE), antibiotic-responsive enteropathy (ARE), and non-responsive enteropathy (NRE), with 13–18% of dogs with CIE being categorized as having NRE [6,7]. A system modified by replacing ARE with microbiota-related modulation-responsive enteropathy (MrMRE) has been proposed by another author group [8]. However, overall, this is a clinical classification system and the underlying pathophysiology among these subgroups is often overlapping [9], and dogs within one subgroup can potentially also respond to other treatments. For example, in recent literature, some NRE dogs were still recategorized as FRE when another diet was trialed [10]. Similarly, a subset of dogs with NRE can also respond to FMT [11,12] or treatment with bile acid sequestrants as adjunct therapy [13].

Protein-losing nephropathy (PLN) describes a kidney disease that causes persistent proteinuria. Proteinuria can be pre-glomerular, glomerular, or post-glomerular in origin. When the urine protein/creatinine ratio (UPC) is >2.0, the amount of albumin loss in urine can sometimes result in a decrease in serum albumin and is more often attributed to glomerular diseases [14]. The most common causes of glomerular disease in dogs include immune complex glomerulonephritis (ICGN), amyloidosis, and glomerulosclerosis, with roughly 50% being ICGN and responsive to immunosuppression [15,16]. This can lead to chronic kidney disease (CKD) where there are structural and/or functional abnormalities in one or both kidneys that have been continuously present for ≥3 months [13], resulting in accumulation of nitrogenous blood products.

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) is an emerging treatment in humans, with high success rates for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection [17,18,19,20,21]. More recent investigations in veterinary medicine have been conducted for a variety of disorders including canine parvovirus [22], chronic inflammatory enteropathy [11,12,23,24], acute diarrhea [25], and acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (AHDS) [26,27]. Other initial studies have also explored the use of FMT in extraintestinal disorders, such as atopic dermatitis [28], diabetes mellitus [29], and epilepsy [30,31]. FMT involves taking the feces of a healthy donor and administering them to a diseased recipient, often as an adjunct therapy. A subset of dogs with CE have severe shifts in their microbiome, as demonstrated by an increased dysbiosis index (DI), and these are associated with more severe functional changes in the host and the microbiome, such as malabsorption of fatty acids, carbohydrates, and bile acids [9,12,32,33,34]. Therefore, FMT may be useful as an adjunct therapy for the improvement of clinical signs, although success may vary, as was noted in a recent study that highlighted that animals with an increased DI often have a short-lived response to FMT, necessitating multiple treatments due to relapses [12]. Proposed mechanisms for improvement with FMT include niche exclusion, where fecal donor strains may compete for the same intestinal niches more successfully than the recipient’s pathogenic strains; increased nutrition competition with pathobionts that reduces the survival of these organisms; production of antimicrobials; and lastly, normalization of bile acid conversion and secondary bile acid concentrations [35]. Other perceived effects include helping restore the integrity of the intestinal barrier through secretions of mucin [36] and shifting of microbial diversity to butyrate-producing bacterial species, which can decrease inflammation via induction of regulatory T cells and IL-10 production [37,38]. In various studies, animals who have received FMT have been reported to exhibit improvements in fecal consistency, clinical signs, appetite, weight gain when underweight, reduction in corticosteroid dosages, and mentation [11,12,22,23,25]. Side effects reported in humans such as bloating, worsening of diarrhea/stool consistency, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or low-grade fever [25,26,27,32] are typically mild or transient in dogs [12]. Currently, there is no clear evidence on the efficacy of different procedures to prepare feces for FMT (e.g., fresh versus lyophilized feces), nor the administration route (oral versus enema) [39]. Some studies have shown clinical benefits of administering FMT with oral capsules [40,41], although long-term follow-up data are still limited. Several studies using repeated enemas reported clinical improvement lasting for more than 6 months in many patients [11,12]. Therefore, FMT administered through rectal enemas was chosen as the primary delivery mode. This is based on our clinical experience and also the fact that an enema will introduce more volume to the recipient compared to oral capsules.

This case report describes the clinical course of a dog with concurrent PLE and PLN that was treated successfully with diet and repeated FMT administered via rectal enema. FMT was considered first before immunosuppressive therapy was attempted due to the concurrent co-morbidity of PLN (see Section 3). Furthermore, we also describe the clinicopathological impact that an episode of AHDS had on the patient.

2. Case Description

A 32.3 kg, 4-year-old, female spayed American Pit Bull Terrier presented to the Internal Medicine service as a second-opinion consultation for PLN and hypoalbuminemia. Her prior diagnostics, 8 months prior to presentation, included complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry, urinalysis, and urine protein/creatinine ratio (UPC), which revealed hypoproteinemia (4.4 g/dL, reference range (RR) 5.2–8.2 g/dL) characterized by hypoalbuminemia (1.9 g/dL, RR 2.3–4.0 g/dL) and low-normal globulin (2.5 g/dL; RR 2.5–4.5 g/dL), azotemia (creatinine 2.1 mg/dL, RR 0.5–1.8 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 52 mg/dL, RR 7–27 mg/dL), hyperphosphatemia (7.4 mg/dL, RR 2.5–6.8 mg/dL), mildly elevated alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) (174 U/L; RR 10–125 U/L), low urine specific gravity (USG) of 1.025, and an elevated UPC (12.6). Prior diagnostics also included abdominal ultrasound, which showed a diffusely thickened gastric wall (1.56–1.86 cm) with mild heterogeneous echotexture, and small intestinal ileus with mild segmental fluid dilation. Other relevant diagnostics included infectious disease testing via Dirofilaria/Anaplasma/Lyme/Ehrlichia serology testing (SNAP 4Dx Plus, IDEXX, Westbrook, ME, USA) and a rapid Leptospirosis IgM-detection immunochromatographic test (WITNESS® Lepto, Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ, USA), both of which were negative; a normal blood pressure (136 mmHg); and an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test that was not consistent with either hypoadrenocorticism or hyperadrenocorticism (pre- and post-cortrosyn cortisol of 1.8 µg/dL and 6.4 µg/dL, respectively). Gastroduodenoscopy showed an edematous gastric mucosa with a mildly hyperemic and irregular duodenal mucosa. Gastric and duodenal endoscopic biopsies revealed sections of histologically normal stomach with focal, moderate lymphoplasmacytic (LP) gastritis with focal gland atrophy and gland fibrosis, and chronic moderate LP and eosinophilic enteritis. She was started on telmisartan 20 mg (0.7 mg/kg) PO q24h, clopidogrel 37.5 mg (1.3 mg/kg) PO q24h, omeprazole 10 mg (0.35 mg/kg) PO q12h, a probiotic (Visbiome®, ExeGI Pharma® Rockville, ML, USA), and a mixture of JustFoodForDogs® Irvine, CA, USA (JFFD) Renal Support Low Protein diet and Royal Canin Renal Support dry food. One month later, albumin and UPC had improved to 2.4 g/dL and 0.3, respectively, and ALT had normalized. At that time, her telmisartan dose was decreased to 10 mg (0.34 mg/kg) PO q24h.

The patient presented one month later for the second opinion consultation, and was reported to have soft stools with mucus, a picky appetite, and ptyalism. Physical examination showed mild peripheral edema of the distal limbs, good body and muscle condition scores (BCS 5/9, MCS 3/3), and a weight of 31.6 kg. Diagnostics included serum chemistry, urinalysis, UPC, and serum cobalamin, folate, trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI), and pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (PLI). Results revealed worsening hypoalbuminemia (1.2 g/dL; RR 2.5–4 g/dL), static globulin (2.8 g/dL; RR 2–3.6 g/dL), hypercholesterolemia (324 mg/dL; RR 120–310 mg/dL), hypocalcemia (8.8 mg/dL; RR 9–12.2), urine specific gravity of 1.032, with 4+ proteinuria on dipstick, pyuria (4–10 WBC/hpf), UPC of 2.6, normal cobalamin (781 ng/L; RR 251–908 ng/L), hypofolatemia (5.6 µg/L; RR 7.7–24.4 µg/L), normal TLI 29.1 µg/L (RR 5.7–45.2 µg/L), and normal PLI (74 µg/L; RR ≤ 200 µg/L). Abdominal ultrasound revealed mild ascites and resolved gastric wall thickening. She was transitioned from a renal diet to a novel protein (white fish), moderately protein-restricted (5.2 g/100 kcal), and low-fat (1.8 g/100 kcal) commercially available diet (JustFoodForDogs® Hepatic Support Low Fat). Other treatment adjustments included adding psyllium husk 3 teaspoons PO q12h, folic acid 400 mcg PO q24h, and omega-3 supplementation of 4 capsules per day (Nordic Naturals® Watsonville, CA, USA, total 660 mg EPA/420 mg DHA, 1320 mg total omega-3 fatty acids), and telmisartan was increased back to 20 mg (0.63 mg/kg) PO q24h.

One month later, she had lost 1.1 kg (30.5 kg) and had an improvement in stool consistency (Purina® St. Louis, MO, USA fecal score*, PFS, 4). The owner ran out of Visbiome® and replaced it with Proviable® (Nutramaxx® Lancaster, CA, USA). Serum chemistry showed improved albumin (2.1 g/dL), decreased globulin (2.4 g/dL), and improved UPC (2.0) with resolved ascites on point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). Telmisartan dose was further increased to 30 mg (0.98 mg/kg) PO q24h.

Another month later, there was progressive weight loss (30.1 kg) and more flatulence. Serum chemistry showed improved albumin 2.6 g/dL, static globulin 2.4 g/dL, and improved UPC (1.3). Telmisartan dose was increased to 40 mg (1.32 mg/kg) PO q24h, along with a further increase in psyllium husk to 4 tsp BID two weeks after that visit.

Four days after increasing her psyllium husk dose, the patient presented for a 24 h history of regurgitation, hyporexia, and urinary incontinence. Thoracic radiographs were unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasound revealed trace ascites, gastric ileus, and mild gastric wall thickening that were previously resolved for 3 months, suspected to be gastritis. Spec cPL was 78 µg/L (normal ≤ 200 µg/L). Urinalysis showed isosthenuria (USG 1.008), 2+ proteinuria, trace hematuria, with no growth on culture. She was hospitalized on a metoclopramide continuous-rate infusion (CRI) at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day and was discharged within 24 h with cisapride 15 mg (0.53 mg/kg) PO q8h and maropitant 60 mg (2.11 mg/kg) PO q24h, with further weight loss at 28.4 kg.

One week after discharge, she had continued weight loss of 0.3 kg (28.1 kg), worsening diarrhea (PFS 6) with increased frequency/urgency, continued flatulence, and resolved regurgitation. Recheck ultrasound revealed mild gastric ileus and trace ascites but normal gastric wall. Recheck labwork showed a new non-regenerative anemia (hematocrit (HCT) 29%, RR 35–57%) and panhypoproteinemia (albumin 2.2 g/dL, globulin 2.2 g/dL), despite a UPC of 0.6 indicating sufficient control of the patient’s PLN. Mycophenolate was initiated for treatment of CIE at a lower dose of 250 mg (8.9 mg/kg) PO q24h due to concern for possible side effects such as diarrhea.

Two weeks later, her stools had firmed up (PFS 4) but were still intermittently soft. Her weight had improved by 0.6 kg (28.7 kg) and her energy was better, and she was strictly on her JFFD diet. Mild ascites noted on POCUS were thought to explain the minor weight gain. CBC and serum chemistry showed static anemia (HCT 30%) and progressive panhypoproteinemia (albumin 1.8 g/dL, globulin 2.0 g/dL). The fecal microbiota Dysbiosis Index® (Texas A&M University, Gastrointestinal Laboratory, College Station, TX, USA) was increased (2.9, normal < 0). The cisapride dose was decreased to 20 mg (0.7 mg/kg) PO, but at q12h since the owner was unable to administer q8h. Due to the persistent soft stool, worsening panhypoproteinemia, muscle mass, and weight loss that were suspected to be related to poorly controlled CIE, treatment escalation was deemed necessary. However, in order to decrease the risk of worsening the management of the PLN, a decision was made not to initiate steroid and/or cyclosporine therapy; therefore, FMT was scheduled for the following week, with the plan to administer a series of 2 FMTs approximately 14 days apart as initial induction therapy, as suggested based on previous data [12].

A few days before the scheduled first FMT, the patient presented with a 2-day history of regurgitation, vomiting, diarrhea (PFS 6–7), hyporexia, and further weight loss of 1 kg (26.7 kg). Gastrointestinal ileus and trace ascites were noted on POCUS. Recheck CBC and chemistry showed static to minimally improved serum proteins (albumin 1.9 g/dL, globulin 2.3 g/dL) and persistent anemia (HCT 33%). She was hospitalized on supportive care (intravenous [IV] fluids and metoclopramide CRI 1.5 mg/kg/day) and ate well. FMT was then performed using feces from a donor that was screened based on current guidelines [39]. The donor was a 4-year-old female spayed Golden Retriever and deemed healthy based on history and physical exam with a BCS of 4–6/9 and a BW of 34 kg. The donor underwent regular screening at least every 6 months, which included a normal DI (typically below −4) and fecal testing for Salmonella spp., Campylobacter jejuni, Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., and other intestinal parasites via centrifugal fecal floatation. Fecal samples were lyophilized without preservatives and stored in a −20 °C freezer for up to 6 months, as described previously [42]. Briefly, fecal samples were divided into multiple aliquots, each containing approximately 10 g of feces in 15 mL plastic tubes. The tubes were covered with Kimwipes secured by rubber bands and frozen at −80 °C for 2–24 h. Frozen samples were then transferred to lyophilizer beakers and freeze-dried overnight using a freeze-drying system (Labconco 710401000 FreeZone 4.5 L –84 C Complete Freeze Dryer System) set to −80 °C and 0.014 mbar (1.4 Pa). The following day, Kimwipes and rubber bands were removed, and the lyophilized feces were gently ground into a fine powder using a spatula. The powdered feces were then used for fecal enemas or capsules and stored at −20 °C for up to 6 months. During this study period, 5 batches of lyophilized fecal materials were from the same fecal donor, with bacterial viability verified after reconstitution with propidium monoazide (PMA)-qPCR in every batch and routine culturing for P. hiranonis as described previously [42]. For each procedure, the patient was walked to defecate before and after being administered a warm water enema (about 20 mL/kg); then, FMT was performed under mild sedation (butorphanol 0.3 mg/kg IV) using 25 g lyophilized feces (approximately 1 g lyophilized feces/kg BW, equaling approximately 3 g fresh feces/kg BW based on previously published protocols [11,12]), which was re-suspended in 150 mL saline and administered via retention enema into the colon over 10 min, and manually held for 10–15 min. The patient then rested in her kennel for at least 90 min. She had hematuria prior to her discharge the next day, so a 1-week course of prazosin 2 mg (0.07 mg/kg) PO q12h was dispensed pending urine culture, which grew Escherichia coli (E. coli). However, her hematuria had resolved, so anti-microbial therapy was not instituted.

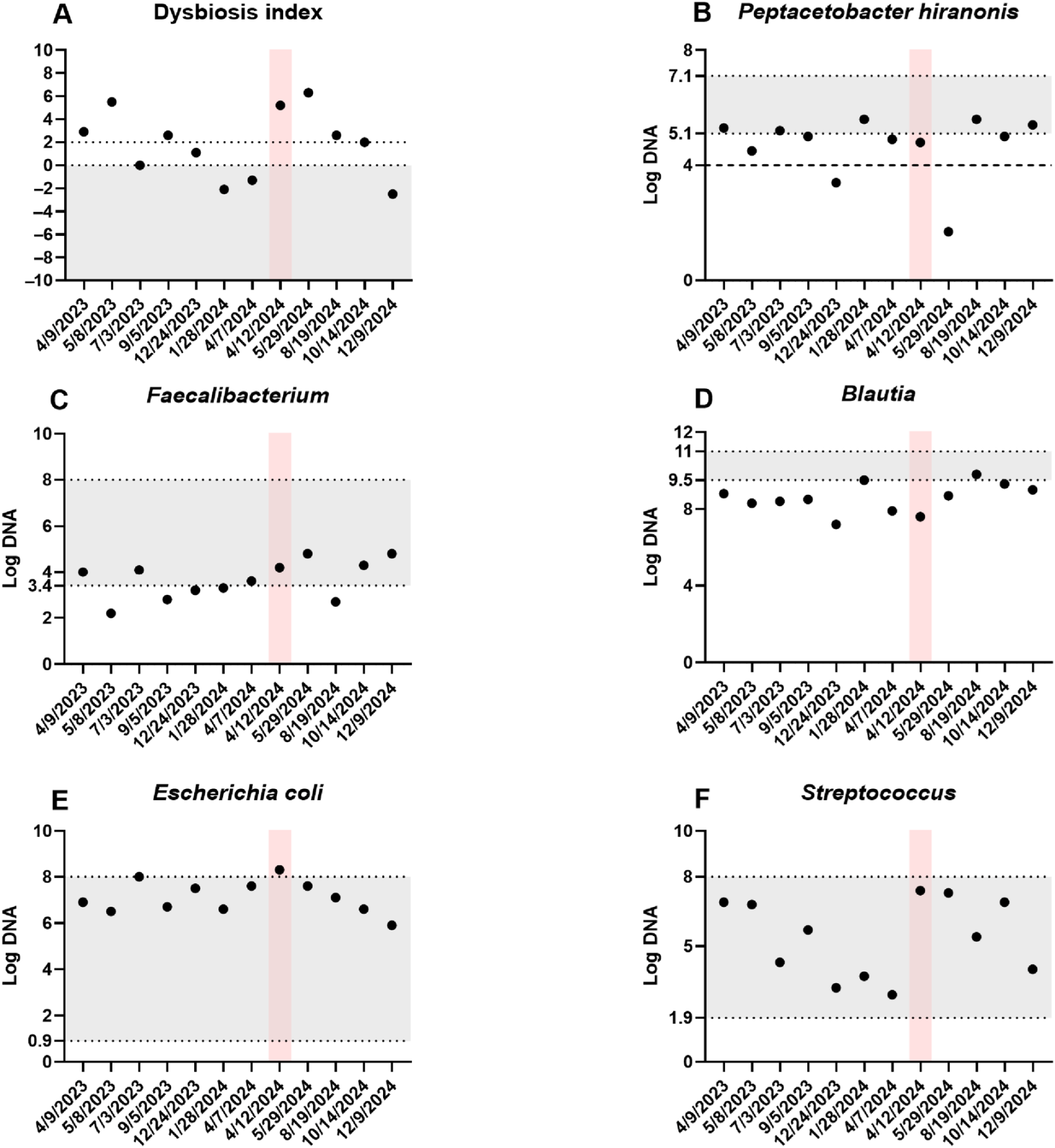

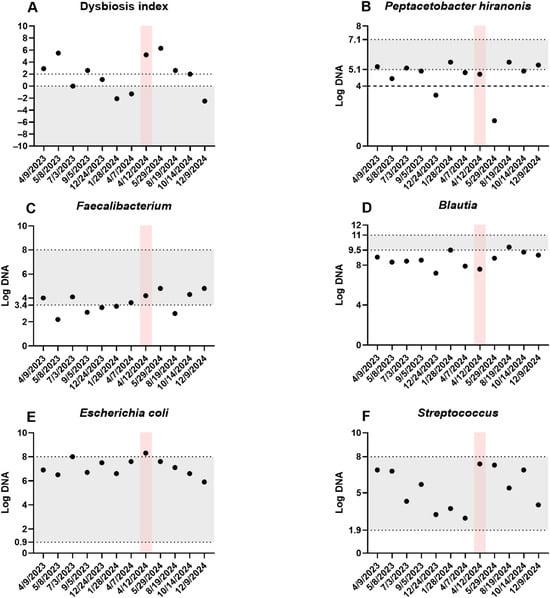

The patient had a decreased appetite for 24 h after the FMT, after which she vomited once, but was noted to have improved energy and appetite and improved PFS (3–4). The patient received her second FMT approximately 2 weeks later and again had transient inappetence for 24 h, which resolved with maropitant. FMT was then performed at 4-weekly intervals due to the patient improving clinically after each FMT but then exhibiting worsening energy and stool quality by week 5. Subsequent FMTs and their clinical data are highlighted in Table 1 and Figure 1. Dysbiosis indexes were submitted after the second and third FMT, which showed an initial persistence of dysbiosis (DI = 5.5 after 2 FMTs) and then progressive normalization (<0) over time in response to repeated FMTs without other changes in treatment (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Timeline of events throughout the case report with presenting complaints/history from prior recheck, treatment changes, and changes to body weight (BW), albumin (alb), globulin (glob), canine chronic enteropathy activity index (CCECAI), and dysbiosis index (DI).

Figure 1.

Fecal dysbiosis and bacterial taxa. The dysbiosis index (A) and five bacterial taxa showing the greatest temporal variation (B–F) are displayed. Each sample was collected prior to a fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) procedure. The patient experienced an episode of acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome from 12 to 15 April 2024, indicated by the red shaded area. The gray shaded area represents the reference intervals. For P. hiranonis (B), the dashed line at log DNA 4 marks the bile acid conversion cutoff, with values below associated with abnormal conversion of primary to secondary unconjugated bile acids.

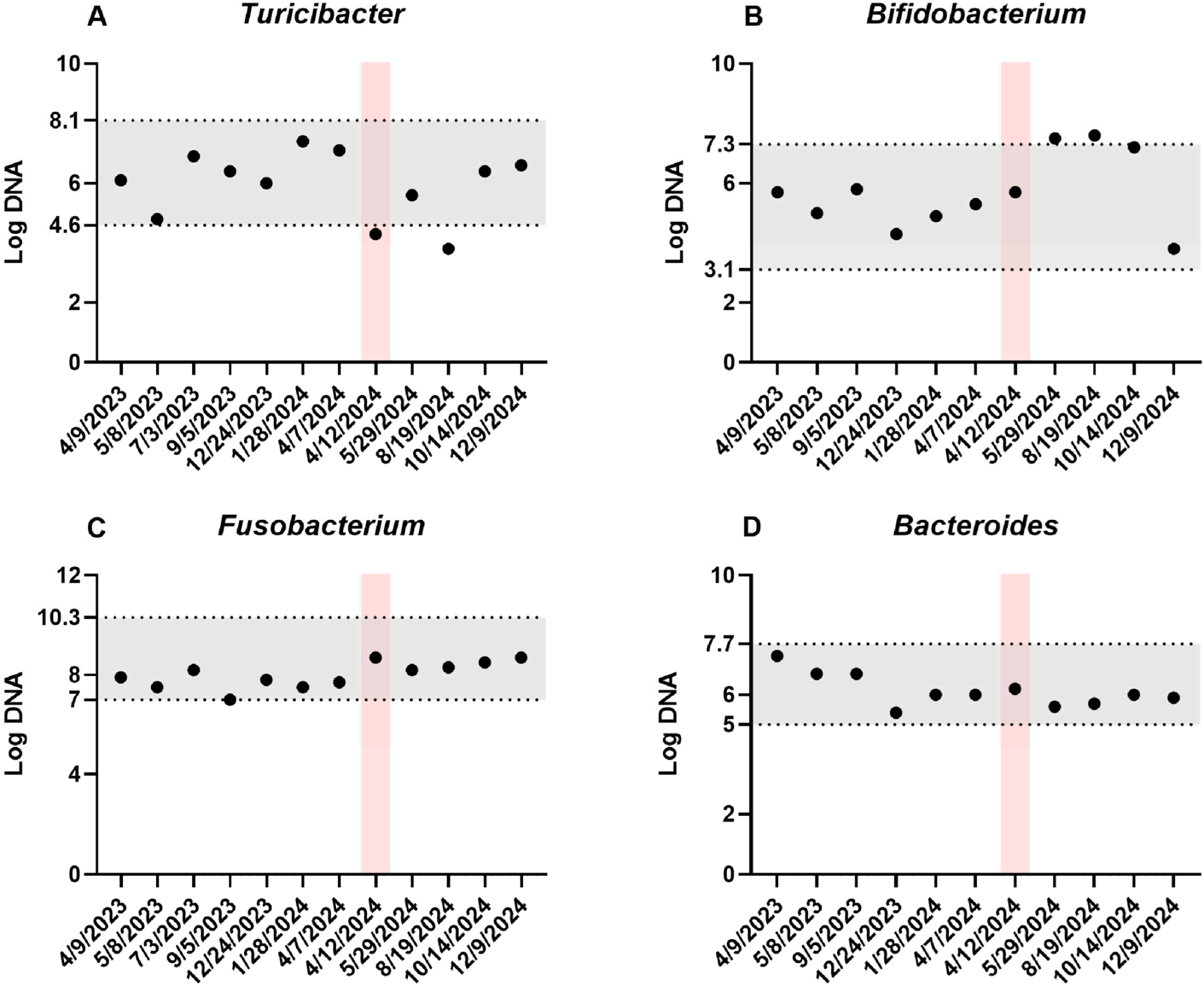

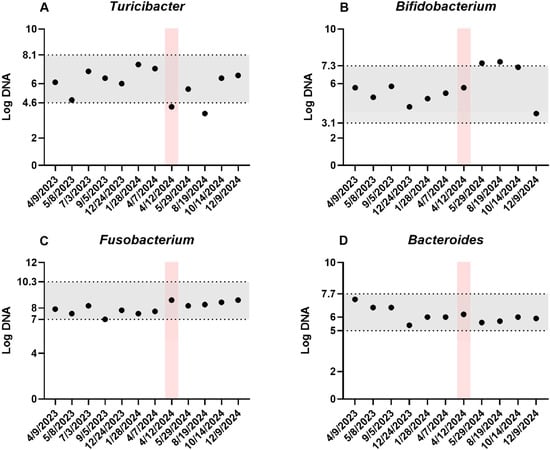

Figure 2.

Additional core bacterial taxa. Four additional bacterial taxa (A–D) were quantified at multiple timepoints, with each sample collected prior to a fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) procedure. The pink shaded area indicates an episode of acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (12–15 April 2024), and the gray shaded area represents the reference intervals.

Mycophenolate was discontinued after the third FMT as it was felt not to have made any clinical impact. No adverse effects were associated with its discontinuation. Since the patient was doing well clinically, the FMT interval was extended to 5 weeks at the 11th FMT. The DI at this visit was normal at −2.1. Unfortunately, the patient relapsed in clinical signs (lethargy, inappetence, and diarrhea) after only 5–6 days after the 11th FMT. At the time of the 12th FMT visit, lyophilized fecal capsules were also initiated at six capsules PO per day (six size #3 capsules each filled with 85 mg (510 mg total) of lyophilized feces per day) for 3 weeks to see if it could help control clinical signs and eventually extend rectal enema FMT treatment intervals. The oral FMT dosage was based on previously published studies and clinicians’ experiences [29,39]. During and after oral FMT, the patient did well during the 4-week interval between enema FMTs apart from one episode of vomiting. Her serum proteins remained static (albumin 2.5 g/dL, globulin 2.3 g/dL). Folic acid was also discontinued. At the 14th FMT visit, the DI was −1.3.

Five days later, roughly 12 months from the first FMT, the patient presented for acute onset of vomiting and hemorrhagic diarrhea. Diagnostics included a mildly elevated Spec cPL (357 ug/L). The patient had mild leukopenia (4.11 × 109/L; RR 6–17 × 109/L) characterized by neutropenia (2.79 × 109/L; RR 3–12 × 109/L), increased BUN 31.8 mg/dL (RR 9–29 mg/dL), mild hypotriglyceridemia (29 mg/dL; RR 30–130 mg/dL), hyponatremia 136 mEq/L (RR 141–152 mEq/L), and overall static albumin and globulin at 2.4 g/dL and 3.2 g/dL, respectively. Because an infectious cause for hemorrhagic diarrhea was suspected, a fecal enteropathogen panel was requested, which was negative for Giardia and Cryptosporidium on immunofluorescence, and PCR-negative for C. difficile, Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, and canine parvovirus. However, the patient was positive for Clostridium perfringens encoding the netF toxin gene on PCR, consistent with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (AHDS). The dysbiosis index was markedly abnormal (5.2, previously −1.3), with an increase in E. coli (8.3; RR 0.9–8 log DNA), and a slight decrease in P. hiranonis (4.8 log DNA; RR 5.1–7.1 log DNA).

The patient was hospitalized with supportive care, which included isotonic fluid therapy, maropitant 27.9 mg (1.02 mg/kg) IV q24h, ondansetron (14 mg; 0.51 mg/kg) IV q8h, and clopidogrel 35 mg (1.28 mg/kg) PO q24h was continued. The next day, the patient became progressively neutropenic (1.10 × 109/L; RR 3–12 × 109/L), monocytopenic (0.08 × 109/L; RR 0.2–1.5 × 109/L), thrombocytopenic (137 × 109/L; RR 165–500 × 109/L), and mildly anemic (HCT 36.82%; RR 37–55%). Antimicrobials, including ampicillin/sulbactam (819 mg IV q8h; 30 mg/kg) and enrofloxacin (227 mg IV q24h; 8.32 mg/kg), were administered due to concern for bacterial translocation. Abdominal ultrasound revealed gastric wall thickening (0.88 cm), colonic wall thickening (0.38 cm), small intestinal ileus, and trace ascites. Enteral nutrition with Vivonex® (Nestlé Health Science, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) via nasogastric tube, psyllium husk 1–2 teaspoon via gel capsules PO q8h, Visbiome® probiotic 1 packet PO q12h (450 billion cfu/packet), and capromorelin 90 mg PO q24h (3.3 mg/kg) were initiated on day 3 of hospitalization. The patient was discharged on day 6 of hospitalization with a recheck chemistry 3 days prior showing decreased serum albumin and globulin of 1.6 g/dL and 2.7 g/dL, respectively.

The patient presented two weeks later for ongoing 4-weekly intervals of FMT. Weight loss of 0.5 kg was noted since discharge (27.4 kg). Serum albumin had improved (2.7 g/dL), with static to slightly improved globulin (2.8 g/dL). Recheck DI showed 5.2 with decreased Blautia, and increased E. coli. Repeated PCR for netF toxin gene was negative.

The patient re-presented for transient large bowel diarrhea 6 days later. Weight gain of 1.5 kg (28.9 kg) was noted. Leflunomide was discussed as another immunomodulatory agent for CIE management, but was never started as her diarrhea quickly resolved.

The patient presented for the 16th FMT 3 weeks later with a 1.1 kg weight loss (27.8 kg). Her submitted DI (6.3) showed decreased P. hiranonis (1.7 log DNA). During the following two FMT visits, her weight and serum proteins remained relatively stable. Due to soft stools (PFS 4 with occasional 5 noted), a 3-week course of lyophilized FMT capsules (six capsules for a total of 510 mg lyophilized feces PO daily) was dispensed at her 18th FMT in addition to her regular enemas.

One month later (19th FMT), the patient’s weight and serum protein remained stable. The patient was doing well for 2 weeks after starting the 3-week course of FMT pills. However, the patient became lethargic, had softer stool (PFS 5), and vomited twice prior to presentation. Serum albumin was decreased (2.5 g/dL). A Fecal Keyscreen® GI PCR (Antech Diagnostics, Fountain Valley, CA, USA) was not suggestive of bacterial or parasitic infection. The recheck DI at that time was 2.6.

A week before the 20th FMT, the patient began regurgitating for 3 days, which improved on cisapride (15 mg PO q8–12 h; 0.51 mg/kg). At the visit, she was noted to be the heaviest she had been (29.4 kg) since the initial FMT. POCUS showed mild gastric ileus, so cisapride was continued. Her serum chemistry showed improved albumin 2.9 g/dL with decreased globulin (2.3 g/dL). Her dysbiosis index was 2. At the 21st FMT visit, the patient showed another 1.1 kg weight gain (30.5 kg) and her PFS was 2, with further improved serum albumin (3.3 g/dL) and similar globulin levels (2.4 g/dL). Her regurgitation and gastric ileus had resolved, so cisapride was tapered.

At the time of writing this manuscript (after the 34th FMT), the patient continues to do well with good energy, stable weight, stable albumin and globulin, and normal stools (PFS 2–3). Her last DI improved markedly at the time of writing (DI −2.5), with normalization of all taxa besides a mild decrease in Blautia spp.

3. Discussion

This case report describes a dog with PLE and PLN that showed clinicopathological improvement with multiple consecutive FMTs. In veterinary medicine, FMT has been reported in case reports or case series as an adjunct treatment in gastrointestinal diseases, where various improvements in weight gain, diarrhea, fecal scoring, vomiting, lethargy, and improved canine inflammatory bowel disease activity index (CIBDAI) scores have been observed [11,18,22,23,25,43]. Various routes of FMT administration include oral, retention enema, or endoscopic [39]. The fecal transplant in this study was delivered primarily via retention enema. Due to soft stools between the patient’s FMT enemas, two courses of oral FMT capsules were added on 12 March 2024 and 22 July 2024. To date, there are no studies comparing the two methods. However, most case reports and canine FMT studies utilize rectal enema or oral capsules [11,12,39,40,42]. Additionally, different forms of fecal material, including fresh, fresh-frozen, and lyophilized feces, have been used in FMT studies [39]. In this report, lyophilized fecal material without cryoprotectants was chosen due to its storage convenience and ease of preparation and reconstitution before procedures. Although lyophilization without cryoprotectants reduces microbial viability compared to fresh feces, the viability was shown to be stable under our storage conditions [42] and was verified for each batch. Currently, there is no established guideline in veterinary medicine defining the minimum viable microbial load required for a successful FMT. And it is possible that the therapeutic effect is driven by multiple factors, including the colonization of live microbes, bacterial cell components, and metabolites present in the fecal material. Furthermore, in two studies using fresh-frozen feces without cryoprotectants, the clinical response was associated with improvement of the DI, which aligns with the overall shift of the gut microbiome and functionality. Therefore, it is reasonable to suspect that the response to FMT is likely related to the severity of the underlying pathophysiology, rather than the microbial viability alone. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to directly assess both the clinical efficacy and microbial viability of FMT materials and correlate with clinical long-term outcomes.

In our case report, the patient experienced clinical improvement, in particular, improved energy and weight gain, along with eventually normalized serum proteins. Two to three initial FMTs were required for the patient to start exhibiting more consistent clinical improvement, which we suspect was related to a markedly increased DI at presentation, as described in previous retrospective studies as well as a recent prospective [11,12]. For example, in one study [44], three dogs with CE were treated with one single FMT, and the DI was analyzed weekly for eight weeks. After FMT, the DI decreased but increased again 3–4 weeks later, and disease activity increased in some dogs. This clinical data shows that repeated FMT is needed to normalize the microbiome, and while there may not be an initial improvement in some patients, there can still be a clinical benefit later on with repeat treatments. This is likely due to underlying persistent pathology, as dogs with an increased DI have more functional changes that are associated with abnormal mucosal absorption due to chronic mucosal remodeling [9].

Therefore, in our case, continuous repeated FMT also led to progressive improvement/normalization in the DI, with increases in Blautia, Turicibacter, and Faecalibacterium, and decreases in E. coli and Streptococcus species. One of the described beneficial mechanisms of FMT is the reestablishment of bile acid metabolism. In dogs, P. hiranonis is the main converter of primary to secondary bile acids and is decreased in a subset of dogs with CIE [24]. There is a significant interplay between host bile acids and the microbiome; for instance, secondary bile acids inhibit the growth of certain pathobionts, which may otherwise contribute to further dysbiosis [45]. However, our patients had normal or just slightly decreased P. hiranonis most of the time, with values above the cut-off for abnormal bile acid conversion (Figure 1). Another positive effect of FMT can be due to the re-establishment of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria. Short-chain fatty acids help reduce inflammation, regulate intestinal motility, and maintain intestinal barrier integrity [39,46,47,48]. Replenishment of the microbiome would help promote an anti-inflammatory state. However, with the underlying inflammatory process of CIE being persistent and multifactorial, it is to be expected that, over time, dysbiosis would likely return after cessation of the FMT, particularly in the absence of other therapies to address, which further emphasizes that FMT should be an adjunct rather than sole/primary therapy in CIE cases [11,12].

The DI is a quantitative PCR-based assay that has been validated to assess overall shifts in the fecal microbiome by quantifying seven core bacterial taxa and the total bacterial abundance, which are commonly altered in both canine and feline chronic enteropathies [33]. In this case report, FMT was performed every 4 weeks due to the timeline of recurrence of clinical signs such as worsening of energy and stool consistency, often by the end of the fourth week or by the fifth week. This illustrates that in some CIE dogs, FMT could be considered as an ongoing adjunct treatment, and this was demonstrated in one study where the DI in dogs receiving FMT was significantly decreased one week post-FMT, but then started to worsen by the four-week mark in one quarter of the dogs enrolled [49]. The findings in our case demonstrate the need for some patients to have repeated FMT, with responses noted after multiple FMTs likely due to the ongoing attempts to correct a significantly dysbiotic microbiome, which was also highlighted in two studies in which dogs with higher DIs, indicating severe dysbiosis, were less likely to respond to FMT [11,12].

Of note, other treatment modalities such as cyclosporine and steroids were not prescribed in our patient due to her concurrent PLN. In our case, steroids were also elected not to be used as a treatment due to the possibility of increased proteinuria [50] as to not confound monitoring of the dog’s PLN, and also due to the risk of worsening hypercoagulability [51] in an animal already at higher risk for thromboembolic disease due to both of her major conditions (PLE and PLN) [52,53]. Cyclosporine was also not utilized due to available human data suggesting possible nephrotoxicity with chronic use [54]. In humans, cyclosporine has been shown to cause renal damage through inflammatory cell infiltration, tubular shrinkage, arteriolopathy, increased immunogenicity and tubular interstitial fibrosis [55]. However, data is lacking in dogs, and discussion of this is beyond the scope of this paper.

During the case report, one year after starting FMTs, the patient experienced an episode of acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (AHDS). Pancreatitis was considered less likely given only a mild elevation in Spec cPL, which was likely secondary to acute gastroenteritis, and a lack of pancreatic abnormalities on ultrasonography [56]. AHDS is a disease that results in an acute onset of hemorrhagic diarrhea with possible vomiting and anorexia preceding the event [57]. Although not present in every dog with AHDS, a higher prevalence of netF-encoding Clostridium perfringens strains has been shown in fecal samples of dogs with AHDS compared with healthy dogs or dogs with other intestinal diseases [58,59]. The netF toxin is a pore-forming toxin that can cause necrosis of the intestinal mucosa, leading to acute vomiting, hemorrhagic diarrhea, and hemoconcentration with discordant serum protein levels [27,60]. For each batch, the same material was analyzed immediately before lyophilization for netF toxin gene-carrying Clostridium perfringens using qPCR, making the possibility of transferring this organism to the recipient unlikely. In dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea, shifts in the microbiome can be seen in dogs, although these are typically milder compared to CIE, and the DI remains < 0 in most dogs, with P. hiranonis remaining within the reference interval [61]. C. perfringens and E. coli are increased, but they normalize relatively quickly, independent of treatment [61]. In our patient, we saw a marked increase in the DI, which may be because the acute episode reactivated the underlying disorder, leading to more severe dysbiosis than would be expected from an AHDS episode alone. This was likely compounded by anti-microbial therapy, as some animals can remain dysbiotic for a prolonged timeframe, as was highlighted in one study where 3/8 dogs were dysbiotic even at 42 days post-event, characterized by increased Bifidobacterium and decreased P. hiranonis, as also seen in this patient [61]. After the next FMT, P. hiranonis increased again to similar levels as before the AHDS and antibiotic administration, further suggesting that the temporary change in this organism was in part due to antibiotic administration. Nevertheless, the DI remained high and again required multiple FMTs to normalize, indicating that the acute episode exacerbated the underlying disease. It is difficult to determine if the patient’s underlying CIE led to the occurrence of the AHDS episode per se. However, we do suspect that the underlying significant microbiome derangement common in CIE may make a patient more susceptible to acute GI episodes, and may take longer to recover from episodes such as AHDS compared to a dog that was previous clinically normal. Interestingly, it took almost 8 months, during which there were continued improvements and declines in the clinical presentation, for the patient’s microbiome to recover from the AHDS event, further highlighting the effect of these acute events on an animal that has also had pre-existing chronic enteropathy and dysbiosis. The acute event did not alter the treatment frequency, as the patient still responded well to the established timeline for repeated FMTs. However, possible consideration could have been given to attempting repeated oral FMT capsules if the patient had required more frequent therapy than what was given prior to the event.

Dogs with CIE with the same disease process can present heterogeneously, so while our management of this patient has led to an ongoing positive outcome, treatment for each CIE patient should be individualized and adjusted based on treatment response. At the time of writing this manuscript, the patient is clinically doing well but still requires repeated monthly FMT enemas.

4. Conclusions

This case report highlights the continued use of adjunct FMT in a dog with CIE, resulting in improved clinical control over time and further highlighting the therapeutic benefits and alternative treatment modality to immunomodulatory therapy that adjunct FMT can provide. The patient suffered from an episode of AHDS, which negatively impacted the overall clinical control of the patient’s CIE with prolonged dysbiotic effect for the following 8 months, illustrating the long-lasting impact of an acute condition on a CIE patient with underlying significant global GI dysfunction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.S. and B.C.; methodology, J.S.S. and B.C.; formal analysis, A.S., C.-C.C., J.S.S. and B.C.; investigation, A.S., J.S.S. and B.C.; resources, A.S., J.S.S. and B.C.; data curation, A.S., J.S.S. and B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and B.C.; writing—review and editing, A.S., C.-C.C., J.S.S. and B.C.; visualization, A.S., C.-C.C., J.S.S. and B.C.; supervision, J.S.S. and B.C.; project administration, J.S.S. and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The microbiome research at Texas A&M University Gastrointestinal Laboratory is supported in part by the Purina Petcare Research Excellence Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not necessary for this study, as a signed informed consent form was considered adequate in the circumstance of a case report. A signed informed consent form was obtained from the owner, allowing the abovementioned procedures to be performed and the use of data for scientific purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owner.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AHDS | Acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome |

| ALT | Alanine-aminotransferase |

| ARE | Antibiotic-responsive enteropathy |

| BCS | Body condition score |

| BW | Body weight |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CBC | Complete blood count |

| CCECAI | Canine chronic enteropathy activity index |

| CE | Chronic enteropathy |

| CIBDAI | Canine inflammatory bowel disease activity index |

| CIE | Chronic inflammatory enteropathy |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRI | Continuous rate infusion |

| FMT | Fecal microbial transplantation |

| FRE | Food-responsive enteropathy |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HCT | Hematocrit |

| ICGN | Immune complex glomerulonephritis |

| IRE | Immunosuppressant-responsive enteropathy |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LP | Lymphoplasmacytic |

| MCS | Muscle condition score |

| NRE | Non-responsive enteropathy |

| PFS | Purina fecal score |

| PLI | Pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity |

| PLN | Protein-losing nephropathy |

| POCUS | Point-of-care ultrasound |

| PLE | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| PO | Per os |

| RR | Reference range |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| TLI | Trypsin-like immunoreactivity |

| UPC | Urine protein/creatinine ratio |

| USG | Urine specific gravity |

References

- Dossin, O.; Lavoue, R. Protein-losing enteropathies in dogs. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pr. 2011, 41, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, E.J.; German, A.J.; Ettinger, S.J.; Feldman, E.C. Small Intestinal Diseases. In Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine; Ettinger, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 4776–4907. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, M.D.; Washabau, R.J. Comparative pathophysiology and management of protein-losing enteropathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandrieux, J.R. Inflammatory bowel disease versus chronic enteropathy in dogs: Are they one and the same? J. Small Anim. Pr. 2016, 57, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.W.; Jergens, A.E. Pitfalls and progress in the diagnosis and management of canine inflammatory bowel disease. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pr. 2011, 41, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, M.; Simpson, J.W.; Ridyard, A.E.; Chandler, M.L. Canine inflammatory bowel disease: Retrospective analysis of diagnosis and outcome in 80 cases (1995–2002). J. Small Anim. Pr. 2004, 45, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, K.; Wieland, B.; Gröne, A.; Gaschen, F. Chronic Enteropathies in Dogs: Evaluation of Risk Factors for Negative Outcome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 21, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouy-Manescau, N.; Méric, T.; Sénécat, O.; Drut, A.; Valentin, S.; Leal, R.O.; Hernandez, J. Updating the Classification of Chronic Inflammatory Enteropathies in Dogs. Animals 2024, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Rachel, P.; Toresson, L.; Sung, C.H.; Blake, A.B.; Lopes, B.C.; Turck, J.; Jergens, A.E.; Summers, S.C.; Unterer, S.; et al. Microbial Gene Profiling and Targeted Metabolomics in Fecal Samples of Dogs With Chronic Enteropathy With or Without Increased Dysbiosis Index. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennogle, S.A.; Stockman, J.; Webb, C.B. Prospective evaluation of a change in dietary therapy in dogs with steroid-resistant protein-losing enteropathy. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2021, 62, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toresson, L.; Spillman, T.; Pilla, R.; Ludvigsson, U.; Hellgren, J.; Olmedal, G.; Suchodolski, J.S. Clinical Effects of Faecal Microbiota Transplantation as Adjunctive Therapy in Dogs with Chronic Enteropathies—A Retrospective Case Series of 41 Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toresson, L.; Ludvigsson, U.; Olmedal, G.; Hellgren, J.; Toni, M.; Giaretta, P.R.; Blake, A.B.; Suchodolski, J.S. Repeated fecal microbiota transplantation in dogs with chronic enteropathy can decrease disease activity and corticosteroid usage. J. Am. Vet. Med Assoc. 2025, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Toresson, L.; Blake, A.B.; Sung, C.H.; Olmedal, G.; Ludvigsson, U.; Giaretta, P.R.; Tolbert, M.K.; Suhodolski, J.S. Fecal and Clinical Profiles of Dogs with Chronic Enteropathies Treated With Bile Acid Sequestrants for 5–47 Months: A Retrospective Case Series. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dibartola, S.W.; Smith, J.R. Glomerular Disease. In Small Animal Internal Medicine; Ettinger, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 672–685. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.M.; Cianciolo, R.E.; Nabity, M.B.; Clubb, F.J., Jr.; Brown, C.A.; Lees, G.E. Prevalence of immune-complex glomerulonephritides in dogs biopsied for suspected glomerular disease: 501 cases (2007–2012). J. Vet. Intern Med. 2013, 27, S67–S75. [Google Scholar]

- IRIS Canine GN Study Subgroup on Immunosuppressive Therapy Absent a Pathologic Diagnosis; Pressler, B.; Vaden, S.; Gerber, B.; Langston, C.; Polzin, D. Consensus guidelines for immunosuppressive treatment of dogs with glomerular disease absent a pathologic diagnosis. J. Vet. Intern Med. 2013, 27, S55–S59. [Google Scholar]

- van Nood, E.; Vrieze, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Fuentes, S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Visser, C.E.; Kuijper, E.J.; Bartelsman, J.F.; Tijssen, J.G.; et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, G.; Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; Kump, P.; Satokari, R.; Sokol, H.; Arkkila, P.; Pintus, C.; et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2017, 66, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Steiner, T.; Petrof, E.O.; Smieja, M.; Roscoe, D.; Nematallah, A.; Weese, J.S.; Collins, S.; Moayyedi, P.; Crowther, M.; et al. Frozen vs Fresh Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Clinical Resolution of Diarrhea in Patients With Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kassam, Z.; Lee, C.H.; Yuan, Y.; Hunt, R.H. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Masucci, L.; Quaranta, G.; Simonelli, C.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Sanguinetti, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G. Randomised clinical trial: Faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy plus vancomycin for the treatment of severe refractory Clostridium difficile infection-single versus multiple infusions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.Q.; Gomes, L.A.; Santos, I.S.; Alfieri, A.F.; Weese, J.S.; Costa, M.C. Fecal microbiota transplantation in puppies with canine parvovirus infection. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 707–711. [Google Scholar]

- Berlanda, M.; Innocente, G.; Simionati, B.; Di Camillo, B.; Facchin, S.; Giron, M.C.; Savarino, E.; Sebastiani, F.; Fiorio, F.; Patuzzi, I. Faecal Microbiome Transplantation as a Solution to Chronic Enteropathies in Dogs: A Case Study of Beneficial Microbial Evolution. Animals 2021, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchiato, C.G.; Sabetti, M.C. Effect of faecal microbial transplantation on clinical outcome, faecal microbiota and metabolome in dogs with chronic enteropathy refractory to diet. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitman, J.; Ziese, A.L.; Pilla, R.; Minamoto, Y.; Blake, A.B.; Guard, B.C.; Isaiah, A.; Lidbury, J.A.; Steiner, J.M.; Unterer, S.; et al. Fecal Microbial and Metabolic Profiles in Dogs With Acute Diarrhea Receiving Either Fecal Microbiota Transplantation or Oral Metronidazole. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, A.; Barko, P.C.; Biggs, P.J.; Gedye, K.R.; Midwinter, A.C.; Williams, D.A.; Burchell, R.K.; Pazzi, P. One dog’s waste is another dog’s wealth: A pilot study of fecal microbiota transplantation in dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugan, M.C.; KuKanich, K.; Freilich, L. Clinical response in dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome following randomized probiotic treatment or fecal microbiota transplant. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1050538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, K.; Shima, A.; Takahashi, K.; Ishihara, G.; Kawano, K.; Ohmori, K. Pilot evaluation of a single oral fecal microbiota transplantation for canine atopic dermatitis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.; Barko, P.; Ruiz Romero, J.D.J.; Williams, D.A.; Gochenauer, A.; Nguyen-Edquilang, J.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Pilla, R.; Ganz, H.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; et al. The effect of lyophilised oral faecal microbial transplantation on functional outcomes in dogs with diabetes mellitus. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2025, 66, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanangura, A.; Meller, S.; Farhat, N.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Pilla, R.; Khattab, M.R.; Lopes, B.C.; Bathen-Nöthen, A.; Fischer, A.; Busch-Hahn, K.; et al. Behavioral comorbidities treatment by fecal microbiota transplantation in canine epilepsy: A pilot study of a novel therapeutic approach. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1385469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrino, M.; Pirolo, M.; Bianco, A.; Castellana, S.; Del Sambro, L.; Tarallo, V.D.; Guardabassi, L.; Zatelli, A.; Gernone, F. Idiopathic epilepsy in dogs is associated with dysbiotic faecal microbiota. Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, A.P.; Souza, C.M.M.; de Oliveira, S.G. Biomarkers of gastrointestinal functionality in dogs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2022, 283, 115183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShawaqfeh, M.K.; Wajid, B.; Minamoto, Y.; Markel, M.; Lidbury, J.A.; Steiner, J.M.; Serpedin, E.; Suchodolski, J.S. A dysbiosis index to assess microbial changes in fecal samples of dogs with chronic inflammatory enteropathy. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.H.; Pilla, R.; Chen, C.C.; Ishii, P.E.; Toresson, L.; Allenspach-Jorn, K.; Jergens, A.E.; Summers, S.; Swanson, K.S.; Volk, H.; et al. Correlation between Targeted qPCR Assays and Untargeted DNA Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing for Assessing the Fecal Microbiota in Dogs. Animals 2023, 13, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuniyazi, M.; Hu, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, N. Canine Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Current Application and Possible Mechanisms. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoruts, A.; Sadowsky, M.J. Understanding the mechanisms of faecal microbiota transplantation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, M.N.; Shaheen, W.; Oo, Y.H.; Iqbal, T.H. Immunological mechanisms underpinning faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 199, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quera, R.; Espinoza, R.; Estay, C.; Rivera, D. Bacteremia as an adverse event of fecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with Crohn’s disease and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, J.A.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Gaschen, F.; Busch, K.; Marsilio, S.; Costa, M.C.; Chaitman, J.; Coffey, E.L.; Dandrieux, J.R.; Gal, A.; et al. Clinical Guidelines for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Companion Animals. Adv. Small Anim. Care 2024, 5, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, F.; Simionati, B.; Patuzzi, I.; Lombardi, A.; Giron, M.C.; Savarino, E.; Facchin, S.; Giada, I. A Protocol for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Using Freeze-Dried Capsules: Dosage and Outcomes in 171 Dogs with Chronic Enteropathy. Pets 2025, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.-O.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Youn, H.; Seo, K. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation via Commercial Oral Capsules for Chronic Enteropathies in Dogs and Cats. J. Vet. Clin. 2024, 41, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Lopes, B.; Turck, J.; Tolbert, M.K.; Giaretta, P.R.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Pilla, R. Prolonged storage reduces viability of Peptacetobacter (Clostridium) hiranonis and core intestinal bacteria in fecal microbiota transplantation preparations for dogs. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1502452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niina, A.; Kibe, R.; Suzuki, R.; Yuchi, Y.; Teshima, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Kataoka, Y.; Koyama, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation as a new treatment for canine inflammatory bowel disease. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2021, 40, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbec, Z. Evaluation of Therapeutic Potential of Restoring Gastrointestinal Homeostasis by a Fecal Microbial Transplant in Dogs. Master Thesis, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.D.; Myers, C.J.; Harris, S.C.; Kakiyama, G.; Lee, I.K.; Yun, B.S.; Matsuzaki, K.; Furukawa, M.; Min, H.K.; Bajaj, J.S.; et al. Bile Acid 7alpha-Dehydroxylating Gut Bacteria Secrete Antibiotics that Inhibit Clostridium difficile: Role of Secondary Bile Acids. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.M.; Howitt, M.R.; Panikov, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C.A.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Glickman, J.N.; Garrett, W.S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 2013, 341, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Regulatory role of short-chain fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Commun. Signal 2022, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M.D. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2013, 20, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitman, J.G.; Guard, B.; Sarwar, F.; Lidbury, J.A.; Suchodolski, J.S. Fecal Microbial Transplantation Decreases the Dysbiosis Index in Dogs Presenting with Chronic Diarrhea (Abstract). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 1287. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, C.B.; Adams, L.G.; Scott-Moncrieff, J.C.; DeNicola, D.B.; Snyder, P.W.; White, M.R.; Gasparini, M. Effects of glucocorticoid therapy on urine protein-to-creatinine ratios and renal morphology in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1997, 11, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.J.; Dunn, M.E.; Allegret, V.; Bédard, C. Effect of prednisone administration on coagulation variables in healthy Beagle dogs. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 40, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon, E.M.; Hanel, R.M.; Walker, J.M.; Vaden, S.L. Hypercoagulability in dogs with protein-losing nephropathy as assessed by thromboelastography. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L.V.; Goggs, R.; Chan, D.L.; Allenspach, K. Hypercoagulability in dogs with protein-losing enteropathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Nepovimova, E.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Kuca, K. Mechanism of cyclosporine A nephrotoxicity: Oxidative stress, autophagy, and signalings. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.E.; Yang, C.W. Established and newly proposed mechanisms of chronic cyclosporine nephropathy. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, M.D.; Hosgood, G.; Swindells, K.L.; Mansfield, C.S. Diagnostic accuracy of the SNAP and Spec canine pancreatic lipase tests for pancreatitis in dogs presenting with clinical signs of acute abdominal disease. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2014, 24, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterer, S.; Busch, K.; Leipig, M.; Hermanns, W.; Wolf, G.; Straubinger, R.K.; Mueller, R.S.; Hartmann, K. Endoscopically visualized lesions, histologic findings, and bacterial invasion in the gastrointestinal mucosa of dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2014, 28, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh Gohari, I.; Parreira, V.R.; Nowell, V.J.; Nicholson, V.M.; Oliphant, K.; Prescott, J.F. A novel pore-forming toxin in type A Clostridium perfringens is associated with both fatal canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and fatal foal necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122684. [Google Scholar]

- Wessely, V.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Cavasin, J.P.; Holz, M.; Busch-Hahn, K.; Unterer, S. Prevalence of Clostridium perfringens Encoding the netF Toxin Gene in Dogs with Acute and Chronic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Pets 2025, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipig-Rudolph, M.; Baiker, K.; Prescott, J.F.; Mehdizadeh Gohari, I.; Hermanns, W.; Wolf, G.; Verspohl, J.; Unterer, S. Intestinal lesions in dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome associated with netF-positive Clostridium perfringens type A. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2018, 30, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisinger, A.; Stübing, H.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Pilla, R.; Unterer, S.; Busch, K. Comparing treatment effects on dogs with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome: Fecal microbiota transplantation, symptomatic therapy, or antibiotic treatment. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.