Abstract

Measurement of vitamin E levels is used to evaluate the health status in humans. For routine analytics in clinical laboratories, an accurate, quick, and simple determination method is required. An option for the quantification of vitamin E (α-tocopherol) in human blood samples is the use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in combination with a UV detector. Several sample preparation methods for this purpose have been reported in the literature. Our aim was to generate an overview and comparison of the different methods. The online database PubMed was searched for published HPLC methods. Of 77 reports screened, 16 methods were selected and summarized in tables. These present the parameters of the sample preparation procedure, HPLC settings, and some validation criteria (limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and intra- and inter-assay values, recovery rates) of the reported methods. In the frame of our methodological review, we could find some extraction approaches. The liquid–liquid extraction with hexane or the double extraction with hexane were often used. Another possibility is the single extraction approach. This systematic review highlights the similarities and differences in methods, and it can therefore be used to develop and establish methods in a laboratory.

1. Introduction

1.1. Vitamin E Structure, Occurrence, Function

Vitamin E is an essential micronutrient for humans [1]. Vitamin E is a collective term for a group of compounds with antioxidant effects [2], which includes eight chemical forms (isomers) [3,4]. The forms are four tocopherols (α-, β-, γ- and δ-tocopherol) and four tocotrienols (α-, β, γ- and δ-tocotrienol) [2,3,4]. These cannot be converted into each other.

α-tocopherol covers the vitamin E requirement in humans [2]. The liver preferentially releases α-tocopherol via the hepatic α-tocopherol transfer protein into circulation, while metabolizing and excreting the other forms of vitamin E [1,5].

All vitamin E compounds have the same basic structure: a chromanol ring system and a differently saturated side chain [2,4]. Tocopherols have a saturated side chain called a phytanyl tail [2,4]. Tocotrienols have an unsaturated isopreonide chain [2,4]. The difference between the α-, β-, γ-, and δ-forms of the isomers lies in the number and position of the methyl groups on the chromanol ring [2,3,4].

The human body is not able to synthesize any member of the vitamin E family, so the nutrients must be obtained through food [3]. Numerous foods contain vitamin E, like seeds and fruits, as well as green leafy vegetables [6]. Another very important dietary sources of vitamin E are vegetable oils [2]. The most important and proven physiological function of vitamin E is as an antioxidant [6].

Oxidative stress is defined as an imbalance between the formation of free oxygen radicals and their neutralization by antioxidants [7,8], which potentially leads to damage of cells [9].

Oxidative stress is associated with a range of diseases, including cancer, arthritis, allergies, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions [8,9]. Humans can protect themselves with mechanisms against the effects of these reactive molecules [8]. These include enzymes and water- and fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamin C, vitamin A, coenzyme Q10, and vitamin E [8]. α-tocopherol is among the central vitamins in the human antioxidant defense system and effectively protects cell membranes from lipid peroxidative damage [10].

1.2. Overview of Sample Preparation and Analytical Procedure

Crude plasma or serum is unsuitable for most chemical analyses and must undergo useful processing [11]. The selection and improvement of a suitable sample preparation scheme is crucial to the success of an analysis [12]. The sample preparation process comprises different steps.

1.2.1. Protein Precipitation

By protein precipitation, tocopherols are released from macromolecules [13].

The basic principle of precipitation is based on changing the solvation potential of the solvent, whereby the solubility of the solute is reduced by the addition of an organic solvent to biological matrices [13,14]. The organic solvent displaces water from the protein surface and instead binds it in hydration shells around the organic solvent molecules. This reduces the solvation layer around the protein, which favors the aggregation of the proteins by electrostatic attraction forces [14].

Common organic solvents, which can be mixed with water, such as methanol, ethanol, acetone, and acetonitrile, can be used to reduce the solubility of proteins and precipitate the proteins from solutions [15]. For precipitation, the usual volume ratio of sample to solvent is 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, or 1:5 [13].

1.2.2. Internal Standard

Adding chemically related compounds as an internal standard allows correction for losses during sample preparation [16]. As internal standards, vitamin E homologues are often used.

1.2.3. Stabilizer

Vitamin E is considered stable at room temperature, but it oxidizes easily at high temperatures, under the influence of light, or in an alkaline environment [6]. To prevent oxidation of vitamins during sample preparation, antioxidants such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) or ascorbic acid can be added as stabilizers [17].

1.2.4. Extraction Approaches

The main task in sample preparation is to extract the vitamin E compound from its complex matrix, the so-called lipoprotein particle [18]. After protein precipitation, the supernatant is usually extracted [13]. The most commonly used techniques are liquid–liquid extraction and solid-phase extraction [11,13].

Liquid–liquid extraction is frequently used for the extraction of fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin E [19]. In liquid–liquid extraction, the hydrophobicity of vitamin E is crucial for the selection of the solvent, as the analyte must be soluble in the chosen solvent. Solvents for extraction should have a low boiling point to facilitate solvent removal and a low viscosity to ensure mixing with the sample matrix [15]. The less polar a solvent is, the more selective it is. Typically, the solvent of choice is the least polar one in which the analyte is still soluble [15]. In addition to the classic liquid–liquid extraction method, there is also the variation of double extraction. Solid phase extraction consists of several steps, such as equilibrating the solid phase extraction cartridge and eluting the purified samples with multiple solvents [20].

Another approach is the single-solvent extraction method. This method uses one solvent for deproteinization. The sample is then directly injected into the HPLC system. Evaporation of excess solvent or re-dissolving of the sample is unnecessary.

1.2.5. Evaporation

After the extraction procedure, the used extraction solvent needs to be removed.

Solvent removal is considered the most common rate-limiting step in sample preparation. It should be noted that the solvents used are often toxic and flammable, and their vapors must be vented [15]. For the evaporation step, a vacuum evaporator is often chosen [13].

1.2.6. Mobile Phase

Generally, the mobile phase is a mixture of polar and non-polar liquid components, and their concentration can vary depending on the composition of the sample [21]. In the normal phase HPLC, the solvent is non-polar; in the reverse phase HPLC, the solvent is a mixture of water and a polar organic solvent [21].

Since the analyte vitamin E is insoluble in water, it is reported that a weak organic solvent with lower viscosity, such as methanol, ethanol, or acetonitrile, should be used as the main component of the mobile phase [13,18]. The mobile phase can also contain small amounts of a so-called modifier [13]. This can be ammonium acetate, methyl chloride, dichloromethane, tetrahydrofuran, or isopropanol [13].

1.2.7. Chromatographic Techniques

Both normal-phase and reversed-phase columns can be used for the separation of tocophe-rols. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) represents an alternative to conventional measurement.

The chromatographic elution can be performed isocratically or by using a binary gradient [22].

In isocratic elution, the mobile phase remains constant and circulates uniformly throughout the separation process [23]. The elution constant and the polarity constant also remain constant. In gradient elution, the composition of the mobile phase changes over time. The polarity and elution strength increase during the separation process [23].

The UV/VIS detector uses a UV wavelength range of 200 to 400 nm and a visible wavelength range of 400 to 800 nm [24]. There are two types of UV/VIS detectors: variable-wavelength detectors and fixed-wavelength detectors. The variable-wavelength detector performs over a wavelength range. The fixed-wavelength detector performs at a specific wavelength [24].

1.2.8. Validation

In analytical method development, the aim of the validation process is to test a method and establish the limits of acceptable variability under different conditions. The sensitivity of a method can be expressed by the limit of detection (LOD) and the limit of quantification (LOQ). Reference values are essential for the comparison of analytical methods.

1.3. Clinical Relevance

Vitamin E is discussed to have various beneficial effects on human health: anti-atherogenic, anti-cancer, anti-allergic, anti-cardiovascular, anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging [3,6]. A deficiency of vitamins can lead to certain diseases [25]. Vice versa, some diseases can reduce the absorption of vitamins and thus cause a deficiency of them.

In adults, a tocopherol deficiency is defined by an α-tocopherol level below 5 µg/mL (<11.6 µmol/L) [26].

Vitamin E is used as a dietary supplement for health promotion and disease prevention, alone or in combination with other micronutrients [6]. The recommended daily intake of vitamin E is between 3 and 15 mg per day, depending on the consulted guideline and age [1,6].

The measurement of the vitamin E concentration in plasma or serum is the simplest way to obtain knowledge about the absorption of the compound and thus the vitamin E status [5,27].

1.4. Aim of This Work

The aim of this work is to provide an overview of published methods on the quantification of vitamin E in human blood samples using HPLC and UV detection.

The various sample preparation steps, HPLC conditions, and the achieved quality criteria of the studies will be described in tabular form.

We want to make the various variations in the sample preparation methods apparent, so that similarities and differences can be identified at a glance.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure for Searching the Database

The literature search for the systematic review was executed according to the PRISMA guidelines within the frame of the application of the criteria [28]. The PRISMA checklist is attached to the manuscript as Supplement File S1.

The online database PubMed search was performed with the following search terms:

- #1 vitamin* E OR vitamin-E OR Alpha-Tocopherol OR a-Tocopherol OR D-Alpha-Tocopherol

- #2 HPLC OR “high-performance liquid chromatography” OR “high-pressure liquid chromatography”

- #3 plasma OR blood OR serum

- #4 UV detect*

These search terms were formulated for the search combination:

#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4.

The search was performed on 29 March 2025.

2.2. Selection of Studies

The abstracts of all results were screened for inclusion in the full-text review. Full-text articles were selected for inclusion in this review by using the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1 by two persons. Disagreement was solved by discussion.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Manuscripts about new methods or the modification of existing methods were included. Manuscripts without new methodological adaptations or that relate to applications were excluded.

2.3. Data Collection, Extraction, and Analysis

Based on the collected data, detailed descriptive and qualitative analyses were performed to evaluate published methods for vitamin E quantification. Two people individually analyzed and documented the characteristics of each method. Following characteristic parameters of the sample preparation steps and HPLC settings were examined and summarized: protein precipitation, extraction, extractant, evaporation, mobile phase, elution, flow rate, column, injection volume and oven temperature of the HPLC, UV wavelength, LOD (limit of detection), LOQ (limit of quantification), reference values, calibration curve, linearity, precision intra-assay, precision inter-assay, and chromatogram. Conflicting reports were resolved through discussion. The results were summarized in a narrative manner.

3. Results

3.1. Search

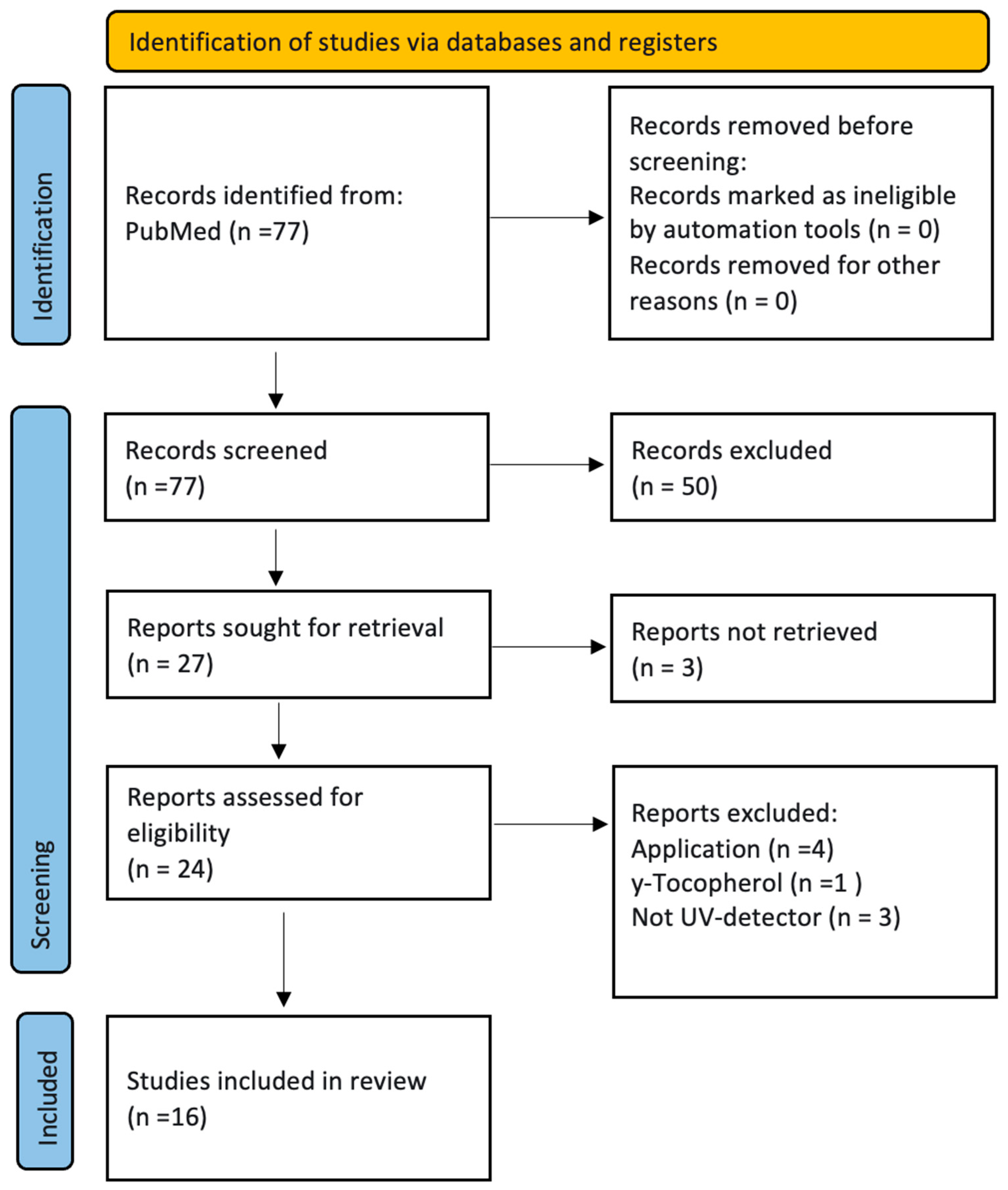

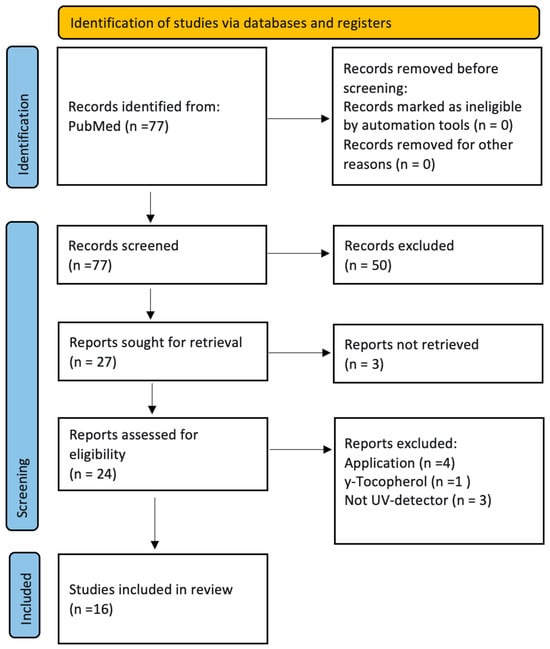

The search and selection process is described in the flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram according to PRISMA 2020 [28].

16 published methods were selected and are discussed in detail in the following chapter with a focus on the respective sample preparation steps.

3.2. Characteristics of Sample Preparation Approaches

Table 2 and Table 3 provide an overview of the different sample preparation characteristics of the 16 selected methods for the quantification of α-tocopherol.

Table 2.

Overview of the sample preparation steps.

Table 3.

Overview of the HPLC settings of the methods presented.

3.3. Reporting of the Sample Preparation Characteristics

The sample preparation process comprises different steps: protein precipitation, liquid–liquid extraction or solid phase extraction, concentration of the extract through evaporation, redissolution of the extract, and finally the chromatographic measurement with a HPLC apparatus. In general, the process of sample preparation was often performed under dim light at ambient temperature [9].

For the precipitation, the following solvents were used: acetonitrile (n = 2) [20,39], methanol pure or in combination (n = 6) [8,9,31,33,34,37], ethanol pure or in combination (n = 8) [9,29,31,32,35,36,38,40] butanol-ethyl acetate (n = 1) [10], methanol/isopropanol (n = 1) [34], dichloromethane mixtures [36], as well as different combinations of these reagents with the addition of BHT (n = 4) [9,10,29,30] or tetrahydrofuran (THF) (n = 2) [30,39] and ethanol with 0.01% ascorbic acid [32].

As internal standards, vitamin E homologues are often used. The following were reported: tocopherol acetate (n = 6) [10,31,32,34,36,40] and alpha-tocopherol nicotinate (n = 1) [38], α-tocopherol (n = 1) [9], and tocol (n = 1) [29].

There are two possibilities for the extraction of α-tocopherol. First, liquid–liquid extraction (n = 12), followed by evaporation. Second, the single-step extraction method, which was performed by Lazzarino et al. [20] and Semeraro et al. [10]. This method executes an extraction without evaporation, but with direct injection into the HPLC apparatus.

The following solvents appeared to be suitable for liquid–liquid extraction: acetonitrile (n = 1), hexane (n = 11), dichloromethane (n = 2), butanol-ethyl acetate (n = 1), ethyl acetate with hexane (n = 1).

Khan et al. [9], Karpinski et al. [8], and Ortega et al. [31] applied the liquid–liquid extraction with hexane and mixtures containing it twice. Barua et al. [36] executed the liquid–liquid extraction with hexane in combination with ethyl acetate.

For concentrating the vitamin E extract after extraction, either an evaporation step under a nitrogen stream (n = 9) [8,9,29,30,32,34,35,37,40] and in combination with a vacuum concentrator (n = 1) [31] or only the use of a vacuum concentrator (n = 1) [38] was reported. Another opportunity is the evaporation with argon gas (n = 1) [36].

After concentration, the dry extract must be redissolved for further chromatographic processing. For the reconstitution, different reagents were used: pure methanol or mixtures (n = 7) [8,9,29,34,35,36,38], pure acetonitrile or mixtures (n = 3) [31,35,40], tetrahydrofuran (n = 2) [29,32] or different compositions of them or 2-propanol (n = 2) [30,31].

For the analytical process the following mobile phase solvents were recommended pure methanol (n = 1) [10], acetonitrile mixtures (n = 7) [20,30,32,33,35,36,40], methanol compositions (n = 14) [8,9,20,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40], mixtures with THF (n = 3) [32,35,39] and with methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (n = 2) [29,38] in different ratios.

The elution can be carried out isocratically or as a gradient. During gradient elution, both the composition and the duration of the mobile phase change during chromatography. The reported flow rates were between 0.4 mL/min [29] and 2.5 mL/min [34].

The oven temperature was specified at around 20 °C [37] and 40 °C [31], but many publications missed to mention it. The UV wavelength differed minimally, being in the range of 284 nm [40] to 296 nm [37].

3.4. Reporting of the Validation Criteria and HPLC Settings

Table 4 shows the validation criteria that were included in the publications mentioned.

Table 4.

Reporting of validation criteria and the type of measurement.

Most of the publications mentioned the validation criteria limit of quantification (LOQ) and limit of detection (LOD). In many publications, the reference value (n = 11) was also mentioned.

The linearity, as well as the further validation parameters intra-assay precision (n = 13), and inter-assay precision (n = 14) were frequently reported.

Almost everywhere, one could find a description of the HPLC settings, including mobile phase, elution, flow rate, column oven temperature, and detector wavelength.

Table 5 shows, additionally, the special features of the presented methods.

Table 5.

Overview of the special features of the publications.

3.4.1. Validation of the Methods

Table 6 shows the validation characteristics of the examined methods, which include LOD, LOQ, as well as reference values. Table 7 shows further validation parameters.

Table 6.

Validation parameters: LOD, LOQ, and reference values.

Table 7.

Validation parameters: recovery rate, inter- and intra-assay precision.

LOD and LOQ Values

The developed methods presented here were validated against the parameters LOD, LOQ, recovery rate, inter-and intra assays (comparison Table 6 and Table 7).

No determination of LOD and LOQ values was performed by Barua et al. and Kock et al. [36,40].

No determination of LOQ values was performed by Franke et al., Ortega et al., Talwar et al., Aksnes et al., Bui et al., Van Haard et al. [18,29,31,32,34,37].

The lowest LOQ values were shown by Lazzarino et al. [20] (13 ng/mL) and Khan et al. [9] (18 ng/mL, 79 ng/mL, and 90 ng/mL). Paliakov et al. [17] showed a LOQ value of 261 ng/mL, and values of just under and over 1000 ng/mL were presented by Cooper et al. [33] (1000 ng/mL), Semeraro et al. [10] (950 ng/mL), and Karpińska et al. [30] (1184 ng/mL).

No LOD values were reported by Boulet et al., Cooper et al., Julianto et al., and Kock et al. [33,38,39,40].

LOD values below 400 ng/mL were determined by Semeraro et al. [10] (290 ng/mL), Karpińska et al. [30] (336 ng/mL), and Bui et al. [18] (198 ng/mL). LOD values over 400 ng/mL were calculated by Aksnes et al. [34] (517 ng/mL), Van Haard et al. [37] (861 ng/mL), Ortega et al. [31] (906 ng/mL), and Talwar et al. [32] (1077 ng/mL).

Methods that exhibit lower LOD and LOQ values compared to other methods are considered high-quality methods in this publication. It should not be overlooked that the determination of these values depends on the chromatographic columns and settings used.

Recovery Rate, Intra- and Inter-Assay Precision

The accuracy of most methods was assessed based on the recovery rate. The recovery rates were above 90% for all methods except those of Karpińska et al. and Aksnes et al. [30,34].

Intra- and inter-assay variability were determined, and, in most cases, the coefficient of variation (CV) was reported based on repeated measurements. The methods demonstrated values in the range from 0.56 to 10%.

The methods of Ortega et al. and van Haard et al. show recovery rates above 100% and CV (intra-assay %) values above 5 to 10% [31,37].

3.4.2. Method Comparison

The two methods of Khan et al. [9] and Lazzarino et al. [20] are described in more detail, because they were assessed as the most suitable in the frame of the validation criteria consideration.

Khan et al. [9] reported a method for the simultaneous determination of all-trans retinol and tocopherol in human serum. The distinctive feature of this method is the double liquid–liquid extraction with a n-hexane-dichloromethane mixture. An ethanol–methanol (95:5, v/v) mixture was used for protein precipitation, with BHT as a stabilizer. The organic layer was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen to avoid the degradation of the analyte.

Three different reversed-phase particle chromatography columns were tested, including the Kromasil 100 C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), the Brownlee Analytical C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), and the (Supelcosil) LC-18 column (150 mm × 3 mm, 3 µm). The sensitivity of the Supelcosil column was higher than that of the other two columns.

The wavelength was adjusted to 292 nm for α-tocopherol. Methanol–water (99:1, v/v) was used as the mobile phase in isocratic mode. The flow rate varied depending on the column used. 20 μL was injected into the HPLC system, and the column oven temperature was maintained at 25 °C.

Lazzarino et al. [20] described a one-step deproteinization and extraction method with acetonitrile for fat-soluble vitamins and antioxidants. The chromatographic column Hypersil C18 (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) was used. For the HPLC measurement, they used a gradient elution. For 0.5 min, 70% methanol with water was used, followed by 8 min 100% acetonitrile as the mobile phase. They used a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and a column temperature of 37 °C. The detection was in combination with a diode array detector at a wavelength of 295 nm.

The differences between the two methods (Khan et al. and Lazzarino et al. [9,20]) lie in the different extraction techniques. Khan et al. [9] used double hexane extraction, while Lazzarino et al. used a single-step extraction method (direct injection method). Khan et al. [9] tested three different columns (Kromasil, Brownlee Analytical C18 column, and Supelcosil), reporting that Supelcosil was the most sensitive. Lazzarino et al. [20] also used a C18 column. Khan et al. [9] used isocratic elution, while Lazzarino et al. [20] used gradient elution. The detector wavelength was 292 nm for Khan et al. [9] and 295 nm for Lazzarino et al. [20].

4. Discussion

4.1. Consideration About Sample Preparation and Analytical Procedure

In the past, the area of analytical separation and detection received considerable attention, while sample preparation remained less noticed [11].

Many methods for quantification of vitamin E in blood samples by HPLC have been published in the literature [9,10,20,41].

Heterogeneity exists between the studies. This makes a comparison difficult. The presented studies have different publication years (from 1987 to 2020). The used equipment exhibits different levels of technology (HPLC apparatus, column type, and column chemistry) and different operators for sample preparation and HPLC analysis.

These differences represent a limiting factor for comparability. A feature of the methodological analysis and evaluation is that the methods can be categorized according to their extraction technique.

4.1.1. Sample Preparation

Protein Precipitation

For deproteinization, ethanol was used in 8 out of 16 studies.

Methanol was applied in 6, and acetonitrile was applied in 2 out of the 16 presented methods (see Table 2).

Parrish et al. reported that blood plasma can be mixed with alcohol to denature proteins and release vitamin E. Cervikova et al. reported that for protein precipitation, methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, and butanol can be used [13]. Next to these reagents, ethyl acetate, mixtures of ethanol with ethyl acetate, hexane, and tetrahydrofuran are also sometimes used [13]. Sodium dodecyl sulfate can also be used for protein denaturation and the breakup of the covalent molecule bonds [13].

Arachchige et al. [19] described how Polson et al. [42] have reported that the use of the two solvents, methanol and acetonitrile, in a plasma to solvent ratio of 1:2.5 removed 94% of the proteins with methanol and 97% with acetonitrile. Protein removal with ethanol showed an efficiency of 88.6%. While acetonitrile is superior in protein removal, ethanol and methanol are less expensive and more commonly used for fat-soluble vitamins. Ethanol and methanol are compatible with a wide range of mobile phases. Ethanol has a broader range of applications for analyte extraction than methanol and is safer to use [19]. Ethanol has low toxicity and easy market availability [43].

Modifier

The addition of antioxidant compounds avoids the oxidation of tocopherols during the sample preparation [13]. The antioxidative compounds are usually added during the extraction process [13]. The following antioxidants can be used: BHT, ascorbic acid, and pyrogallol [13].

In total, 6 of the 16 summarized methods used the antioxidant BHT for sample stabilization.

The use of the antioxidant was investigated in a concentration range of 1 to 5 mg/mL [44]. A higher concentration of BHT leads to a large interference peak, which suppresses the analyte peaks [44].

Overview of Extraction Approaches

The following section describes the different extraction methods.

- Liquid–Liquid Extraction

Liquid–liquid extraction is considered the technique of choice for extracting tocopherols from the biological matrix [13]. Liquid–liquid extraction is suitable because vitamin E is lipophilic and because this technique is relatively simple [13].

The advantages of liquid–liquid extraction include high separation selectivity, low energy consumption, low costs, and short method development times [11].

The disadvantages of liquid–liquid extraction include difficulty in automation, labor-intensiveness, the use of large amounts of toxic organic substances, and poor sample throughput [11]. This technique is not considered very environmentally friendly [13].

In addition to the classic liquid–liquid extraction method, there is also the variation of double extraction. This type of method is also somewhat time-consuming, since the extract has to be taken twice in the hydrophobic phase [13]. Nowadays, the technique represents a miniaturized version of the liquid–liquid extraction technique, where only 100 to 200 µL of the sample is needed, instead of quantities such as 1 mL, as with the old liquid–liquid extraction technique [13].

Quingping et al. [44] investigated several protein precipitating agents (methanol, acetonitrile, ethanol, 2-propanol, zinc sulfate, and strong acids) and various extraction solvents (dichloromethane, diethyl ether, n-hexane, and ethyl acetate). The results demonstrated that the highest extraction efficiency was achieved using n-hexane. Furthermore, it readily dissolves fat-soluble vitamins and prevents mixing of the blood serum matrix with the water fraction. n-Hexane was selected for the studies, and it was shown that the highest extraction yield was achieved with 800 µL of n-hexane [44].

Hexane is typically used for extraction in quantities of 0.5 to 2 mL [13].

In our method comparison, we found the following organic solvents reported as extractants for α-tocopherol: hexane [31,32], ethyl acetate [36], and dichloromethane [37]. Hexane was the predominant extraction solvent, used in 10 of 16 methods.

- Solid Phase Extraction

An alternative to liquid–liquid extraction is solid phase extraction.

In comparison, solid phase extraction is selective with a wide range of matrices, offers a wide range of sorbents, lower consumption of organic solvents, and high sample throughput.

Disadvantages include greater implementation complexity, prolonged method development, higher costs, and limited selectivity or sensitivity [11]. Solid phase extraction is therefore not suitable for the simultaneous processing of large numbers of samples [20].

Liquid–liquid extraction can be used for the efficient analysis of large sample numbers. However, the required transfer steps make the extraction process labor-intensive and time-consuming [11,15]. Further disadvantage is the requirement of manual skills of the personnel [13].

Solid phase extraction requires less sample material than liquid–liquid extraction [19]: typically, only about 100 µL of plasma is needed [19].

However, LLE appears to offer better sensitivity for fat-soluble vitamins than SPE, and quantification with LLE proves to be more cost-effective, faster, and simpler. Both methods are labor-intensive and use many solvents [19]. Despite its advantages, the method is not represented in our review, which is also reflected in Table 2 and Table 3.

- Single-solvent extraction method

An alternative is the single-solvent extraction method. One solvent is used for protein precipitation, and afterwards, the sample is injected directly into the HPLC apparatus for analysis.

Advantages are less time consumption for the sample preparation (no extraction and no removal of excess solvents are required), reduced reagent consumption, and lower reagent costs.

Further advantages are simplicity and speed of the method, as well as simplicity in automation [19]. However, due to the lack of purification methods, matrix effects occur, which can complicate the analysis [19].

- Summary of extraction approaches

In the frame of our methodical summary (Table 2), liquid–liquid extraction was performed 12 times. The double extraction was executed only three times (by Khan et al. and Karpińska et al. and Ortega et al. [9,30,31]). The single-solvent extraction (or single-step extraction) method was performed four times (Lazzarino et al., Cooper et al., Julianto et al., Semeraro et al. [10,20,33,39]).

Evaporation

After extraction, the hexane layer must be removed. The aim of evaporation is the removal of excess solvents and the concentration of the sample.

It is important that the extracts are dried, as vitamin E is sensitive to light and heat and is not stable in n-hexane and ethanol [44].

The evaporation step was performed with a vacuum concentrator (n = 1) or in combination with the use of nitrogen (n = 1). The most frequently used method was the evaporation with nitrogen (n = 9). Another approach was the use of argon (n = 1).

The methods of Lazzarino et al., Semeraro et al., Cooper et al., and Julianto et al. had no evaporation step [10,20,33,39].

Internal Standard

The usage of an internal standard is suggested [13]. The internal standard serves as a correction for the sample loss during the sample preparation procedure [13].

The internal standard should be structurally similar to the target analyte.

Tocol is often used because it has a similar structure to tocopherol and does not appear in biological matrices [13]. α-tocopherol acetate can also be used [45]. In our method review tocol (n = 1), α-tocopherol acetate (n = 6), or α-tocopherol nicotinate (n = 1) were found to be used.

4.1.2. Analysis

Mobile Phase

The mobile phase consists of more than two compounds.

The use of acetonitrile as the mobile phase leads to sharper peak shapes compared to methanol [19]. Therefore, acetonitrile is preferred. Solutions of fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin E, are pH-sensitive. To prevent changes in the solution’s pH, various additives are included, such as acidic or basic modifiers like formic acid or ammonium formate. The ammonium ions act as a base and buffer any increase in pH [19].

It can be recognized that most of the present mobile phases include acetonitrile in different compositions. Dominant is the composition with methanol. The addition of ammonium acetate is also often seen in the selected methods for pH stabilization.

Zhang et al. reported that the most common mobile phases for vitamin separation are methanol–water and acetonitrile–water. Additionally, mixtures of the three ingredients (water, methanol, and acetonitrile) were described [17].

Elution Technique

Determining the elution technique requires a balance between run time and the total number of eluted analytes [46]. Gradient elution may be more suitable than isocratic elution for a larger number of analytes with a shorter analysis time [46]. In terms of separation speed, gradient elution is a slower technique compared to isocratic elution [47].

Isocratic elution is suitable for simple samples containing fewer than 10 components [47]. A disadvantage of isocratic elution is broader, late-eluting peaks due to peak scattering, as well as long analysis times and carryover [19].

Isocratic separation is the most common method for separating tocopherols [48].

The isocratic elution was used in 11 of 16 studies. The gradient elution was performed by 5 of 16 groups. The crucial aspect of sample preparation is its duration in routine analytics.

HPLC

HPLC is one of the most common methods for determining tocopherol [13]. Both normal-phase and reverse-phase HPLC techniques, or columns, are used for this purpose [13].

Mainly, for the tocopherol separation, three Normal HPLC (NHPLC) stationary phases are used: diol, amino, and silicon dioxide [48]. In contrast to NHPLC, reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) uses relatively nonpolar stationary phases, such as C18 and C30, and various compositions of polar eluents.

Acetonitryl, methanol, dichloromethane, and water are frequently used on C18 or C30 columns [48].

Older studies predominantly used normal stationary phases for the determination of tocopherols, as they allowed for complete separation of all isomers [13]. This method requires high solvent consumption and is therefore considered environmentally harmful. Other disadvantages include low stability, poor reproducibility, and long equilibration times, which have led to the replacement of normal-phase columns with reversed-phase columns [13]. A disadvantage of the reversed-phase column, as well as of UHPLC, is the coelution of β- and γ-tocopherol [13].

As long as the determination of all tocopherol forms is not required, the use of the reverse phase was more suitable [13].

RP-HPLC is the most frequently used analytical method for vitamins [17].

UHPLC

UHPLC nowadays represents an alternative to conventional measurement [13].

UHPLC uses a high-pressure pump system and performs analysis under high pressure over 40 MPa, using short columns with particles smaller than 2 µm [13,17,19].

Advantages are higher efficiency, more sensitive analysis, faster analysis time and run time, better separation, and improved resolution in comparison to other chromatography systems [13,49]. A disadvantage is higher operational costs [49].

HPLC-MS/MS

HPLC-MS/MS has higher selectivity and sensitivity than other instrumental methods [17].

For vitamins, the HPLC-MS/MS analysis is commonly performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive ion ionization mode or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) [13,17,19].

Disadvantages of HPLC-MS/MS include the high acquisition costs and the need for trained personnel [50].

Detector Types

For the routine determination of vitamins in various sample types, classic RP-HPLC with UV, PDA, and fluorescence detectors is used [17]. These methods provide quantitative results but no information about structure or composition [17].

UV detection is used in a wavelength range from 210 to 300 nm, but is usually at 292 nm and 295 nm for tocopherols [13]. This is also mostly seen in our methodological evaluation.

The advantage of the UV detector is its low acquisition cost and its wide availability for routine analysis [13]. Further advantages are reliability, easy use, high precision, and high linearity [24]. A limitation is that solvents need to be transparent [51].

Fluorescence detection, however, is more sensitive and selective [17]. Generally, not all compounds show fluorescence [51]. Fluorescence detectors are sensitive to compounds that are fluorescent or those that can be derivatized to be so [52].

For tocochromanols, fluorescence is measured at 290 m excitation and at 330 nm emission [48]. Demirkaya-Miloglu et al. reported a measured native fluorescence at 334 nm with excitation at 291 nm, after extraction of α-tocopherol from human plasma [53].

The electrochemical detection (ECD) can be used for the analysis of electroactive compounds [52]. The compounds must be able to be oxidized or reduced [51]. Tocopherols have oxidative potential [13]. ECD represents a unique detection method for tocochromanols, as it measures their oxidative products and is compatible with RP-HPLC [48]. ECD detectors are selective and sensitive and are easy to use [51].

4.1.3. Validation

Most of the methods were validated with the following parameters: LOD, LOQ, recovery rate, as well as intra- and inter-assay CV values. Method validation allows to ensure that a method is sensitive, reproducible, and robust [19]. We have described two methods in detail by Lazzarino et al. and Khan et al., which are considered high-quality methods in this publication.

It was found that Lazzarino et al. [20] exhibited the lowest LOD value (8.61 ng/mL), and the recovery rate was from 95.3 to 98.9%. This indicates a very good accuracy and recovery, as the values were nearly 100% [54]. The intra-assay CV was around 1%, and the inter-assay CV was around 0.5% and showed very good precision.

Khan et al. [9] achieved both low LOD (5 ng/mL) and LOQ (18 ng/mL) with the column type “Supelcosil”. The recovery rate was between 95.6 and 101.4%, the CV (intra-assay) was specified up to 3.6%, and the CV (inter-assay) was stated up to 1.5%.

Regarding the recovery rates and intra-and inter-assay precision, both methods showed a very good recovery, accuracy, and a very good precision. Both methods are reliable and reproducible.

According to the analysis of the validation parameters, we can conclude that most methods show high recovery rates, high accuracy of sample concentrations, and CV values from 0.5 to 10%, and thus very good to good precision.

Most publications have mentioned that their methods can be applied for analysis in routine analytics and are reliable.

4.2. Choice of a Sample Preparation Method

There are methods that allow the simultaneous measurement of vitamin E along with additional compounds, where other methods are limited to the determination of vitamin E only. So, the desired application must be known before choosing a method.

We do not want to recommend a specific method, as each method also depends on the chromatography equipment used and the fine adjustments of the HPLC system.

However, we prefer a method that requires fewer reagents for sample preparation, as this saves time when handling large numbers of samples. The single-step extraction approach is certainly very interesting, but it needs to be tested in the laboratory environment.

In terms of environmental friendliness, a method with low solvent consumption is recommended.

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

This publication presents a systematic review of sample preparation approaches to analyze vitamin E in human blood samples by HPLC in combination with a UV detector.

A table shows the different sample preparation steps and chromatographic settings. This makes it possible to recognize the similarities and differences immediately.

The main concern was on HPLC measurement with UV detection for vitamin E (α-tocopherol). The quantification of other isomers of vitamin E was not considered here. We have not examined the different species of chromatographic columns, although it seems that the interaction of the analyte with the column has an influence on the separation process. Newer columns should be more sensitive and faster [9].

The approaches described refer to the quantification in human samples and not in other tissues. All included publications also have their differences and limitations.

The individual validation criteria (LOD, LOQ, and reference values) were compared, and thus allow conclusions to be drawn about the sensitivity of the methods.

The determined validation parameters are based on different sample preparation methods and HPLC systems. The determination of the reference values was performed with different sample numbers and matrices.

The studies presented showed variations in design and reported quality criteria. Heterogeneity between the studies is given. Not all criteria in each study could be described because some information was not reported in the literature. Further heterogeneity among the studies can be assigned to the following differences: instrument models, column chemistry, different publication years, and variability in operation through different operators.

These limitations reduce the transferability of the results and direct method comparability. We have tried to classify the methods with regard to the type of extraction (liquid–liquid extraction, double extraction, and single-solvent extraction methods).

Each laboratory should carry out the validation of the individual method as part of its method development and thus generate its own specific characteristic values.

The stability studies of some manuscripts were not considered. This would further underline the robustness of the method.

In this publication, other detection possibilities (e.g., electrochemical and fluorescence) and other measurement techniques, such as LC-MS, were not examined.

Cervinkova et al. [13] provided in 2016 an overview of various analysis techniques for the four forms of vitamin E. In contrast to our publication, their work was not based on a systematic search.

Our work could therefore serve as a further supplement to that. It also considers methods using UV detection after the year 2016.

Gamna et al. have published a review with the title “Vitamin E: A Review of Its Application and Methods of Detection When Combined with Implant Biomaterials” [55].

This review article represents the biological role of vitamin E and its biomedical applications over the past 20 years. The focus is on the application of vitamin E (primarily α-tocopherol and tocopherol acetate) to implantable biomaterials (prosthetics) as surface treatment.

Furthermore, the article provides an overview of detection methods for analyzing vitamin E forms in biomaterials. The HPLC apparatus and wavelength are reported in different tables.

The main difference in our review is that we refer to the quantification of vitamin E. (α-tocopherol) using HPLC with UV detection in human blood samples, rather than in biomaterials.

Zhang et al. have presented a review with the title “A Review of the Extraction and Determination Methods of Thirteen Essential Vitamins to the Human Body: An Update from 2010” [17].

This article presents an overview of sample preparation and analysis methods for 13 human vitamins (fat- and water-soluble) from 2010 onwards.

Various sample preparation techniques (e.g., liquid–liquid extraction, SPE, ultrasonic-assisted extraction) are presented. Different analytical methods (HPLC, UHPLC, and GC), assays, and biosensors are also presented.

A tabular summary of various sample treatment methods for different vitamins is provided, specifying the assay technique (LC, MS, and UHPLC) and the matrix, column, mobile phase, and parameters such as LOD and LOQ.

In comparison to our manuscript, the results are summarized narratively, and no targeted systematic search was performed.

4.4. Outlook

The focus of this systematic review was to present different analytical approaches for the determination of vitamin E using HPLC in combination with a UV detector. The overview highlighted the variations in sample preparation and quality criteria. Future research could aim to evaluate other measurement and detection techniques, such as LC-MS.

Another research approach could be to assess solvent usage and overall consumption within the framework of green chemistry, particularly in the determination of vitamin E by HPLC techniques.

4.5. Conclusions

This systematic literature review summarizes different approaches to quantify α-tocopherol in human blood samples with the application of HPLC in combination with a UV detector.

This tabular summary provides an overview of the different sample preparation approaches, highlighting their similarities and differences.

This methodological review revealed the most commonly used techniques for vitamin E extraction: liquid–liquid extraction with hexane or double hexane extraction. Another method would be solid phase extraction. Some authors do not use an extra extraction step but instead perform deproteinization and extraction of the sample in a single step (single extraction method).

For stabilization, some used BHT, or to correct for sample loss, an internal standard, usually tocol or tocopherol acetate.

Isocratic elution was the most frequently used elution technique, rather than gradient elution. The mobile phase often consisted of a composition of acetonitrile and water or methanol and mixtures of them. The RP-HPLC phase system was preferred. The wavelength for UV detection was between 290 and 296 nm.

Most of the presented methods were validated with the criteria LOD, LOQ, recovery rate, intra- and inter-assay CV.

The methods differ in minor details and have various advantages and disadvantages.

Our overview provides valuable support for method development.

The comparability of the different methods is limited due to the state of the art (HPLC apparatus, columns, and reagents), and this should be taken into account.

Readers can choose the method of interest and adapt it to their laboratory conditions, considering the variations in the sample preparation steps.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/labmed3010004/s1. Supplement File S1: PRISMA Checklist [28].

Author Contributions

M.D.: Conceptualization, Literature search, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. P.H.: Literature search, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| APCI | atmospheric pressure chemical ionization |

| CV | coefficient of variation |

| ESI | electrospray ionization |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| LLE | liquid–liquid extraction |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LOQ | limit of quantification |

| RP-HPLC | reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography |

| SPE | solid phase extraction |

| UV | ultraviolet |

References

- Szymańska, R.N.; Nowicka, B.; Trela, A.; Kruk, J. Vitamin E: Structure and forms. In Molecular Nutrition; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Han, S.N. The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, T.; Burdeos, G.C.; Itaya, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Miyazawa, T. Vitamin E: Regulatory Redox Interactions. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungurianu, A.; Zanfirescu, A.; Nițulescu, G.; Margină, D. Vitamin E beyond Its Antioxidant Label. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G. Vitamin E. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E.; Abe, K. Vitamin E: Structure, Properties and Functions. In Vitamin E: Chemistry and Nutritional Benefits; Niki, E., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A. Oxidative Stress: What Is It? Can It Be Measured? Where Is It Located? Can It Be Good or Bad? Can It Be Prevented? Can It Be Cured? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska, J.; Mikoluc, B.; Motkowski, R.; Piotrowska-Jastrzebska, J. HPLC method for simultaneous determination of retinol, alpha-tocopherol and coenzyme Q10 in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 42, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, M.I.; Iqbal, Z.; Shah, Y.; Ahmad, L.; Watson, D.G. An optimized and validated RP-HPLC/UV detection method for simultaneous determination of all-trans-retinol (vitamin A) and alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) in human serum: Comparison of different particulate reversed-phase HPLC columns. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2010, 878, 2339–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, A.; Altieri, I.; Patriarca, M.; Menditto, A. Evaluation of uncertainty of measurement from method validation data: An application to the simultaneous determination of retinol and alpha-tocopherol in human serum by HPLC. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009, 877, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanu, A.B. Recent developments in sample preparation techniques combined with high-performance liquid chromatography: A critical review. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1654, 462444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyötyläinen, T. Critical evaluation of sample pretreatment techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervinkova, B.; Krcmova, L.K.; Solichova, D.; Melichar, B.; Solich, P. Recent advances in the determination of tocopherols in biological fluids: From sample pretreatment and liquid chromatography to clinical studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 2407–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Havlíček, V. 4-Protein Extraction and Precipitation. In Proteomic Profiling and Analytical Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Ciborowski, P., Silberring, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, R.D. Sample preparation for biomedical analysis. J. Chromatogr. 1989, 492, 3–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.; Casal, S. Validation of a fast and accurate chromatographic method for detailed quantification of vitamin E in green leafy vegetables. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.E.; Yan, J.Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.; Ma, Y.L.; Feng, X.S.; Yang, J.; Li, G.H. A Review of the Extraction and Determination Methods of Thirteen Essential Vitamins to the Human Body: An Update from 2010. Molecules 2018, 23, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno, E.; Castellote, A.I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; de la Torre-Boronat, M.C.; López-Sabater, M.C. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of retinol, alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene in human plasma and low-density lipoproteins. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2001, 758, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchige, G.R.P.; Thorstensen, E.B.; Coe, M.; McKenzie, E.J.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Pook, C.J. LC-MS/MS quantification of fat soluble vitamers—A systematic review. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 613, 113980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarino, G.; Longo, S.; Amorini, A.M.; Di Pietro, V.; D’Urso, S.; Lazzarino, G.; Belli, A.; Tavazzi, B. Single-step preparation of selected biological fluids for the high performance liquid chromatographic analysis of fat-soluble vitamins and antioxidants. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1527, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): A review. Ann. Adv. Chem. 2022, 6, 010–020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richelle, M.; Tavazzi, I.; Fay, L.B. Simultaneous determination of deuterated and non-deuterated alpha-tocopherol in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 2003, 794, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, C.; Minocha, N.; Purohit, D.; Kumar, S.; Makhija, M.; Saini, S.; Kaushik, D.; Pandey, P. High Performance Liquid Chromatography: Recent Patents and Advancement. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2022, 15, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handini, A.; Husni, P.; Agustin, I. Comparative Study of HPLC Detectors in PT. FIP: A Review. Calory J. Med. Lab. J. 2025, 3, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.L.; Burckart, G.J.; Venkataramanan, R. Sensitive high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of plasma vitamin E and vitamin A using amperometric and ultraviolet detection. J. Chromatogr. 1986, 380, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larry, E.; Johnson, G.D.B. Vitamin E Deficiency; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16765550 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ford, L.; Farr, J.; Morris, P.; Berg, J. The value of measuring serum cholesterol-adjusted vitamin E in routine practice. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2006, 43, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, A.A.; Morrison, C.M.; Custer, L.J.; Li, X.; Lai, J.F. Simultaneous analysis of circulating 25-hydroxy-vitamin D3, 25-hydroxy-vitamin D2, retinol, tocopherols, carotenoids, and oxidized and reduced coenzyme Q10 by high performance liquid chromatography with photo diode-array detection using C18 and C30 columns alone or in combination. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1301, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliakov, E.M.; Crow, B.S.; Bishop, M.J.; Norton, D.; George, J.; Bralley, J.A. Rapid quantitative determination of fat-soluble vitamins and coenzyme Q-10 in human serum by reversed phase ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography with UV detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009, 877, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, H.; Coperías, J.L.; Castilla, P.; Gómez-Coronado, D.; Lasunción, M.A. Liquid chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of different lipid-soluble antioxidants in human plasma and low-density lipoproteins. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2004, 803, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.; Ha, T.K.; Cooney, J.; Brownlee, C.; O’Reilly, D.S. A routine method for the simultaneous measurement of retinol, alpha-tocopherol and five carotenoids in human plasma by reverse phase HPLC. Clin. Chim. Acta 1998, 270, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.D.; Thadwal, R.; Cooper, M.J. Determination of vitamin E in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1997, 690, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, L. Simultaneous determination of retinol, alpha-tocopherol, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in human serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1994, 18, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.H. Simple determination of retinol, alpha-tocopherol and carotenoids (lutein, all-trans-lycopene, alpha- and beta-carotenes) in human plasma by isocratic liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1994, 654, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, A.B.; Kostic, D.; Olson, J.A. New simplified procedures for the extraction and simultaneous high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of retinol, tocopherols and carotenoids in human serum. J. Chromatogr. 1993, 617, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haard, P.M.; Engel, R.; Postma, T. Routine clinical determination of carotene, vitamin E, vitamin A, 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 and trans-vitamin K1 in human serum by straight phase HPLC. Biomed. Chromatogr. 1987, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, L.; Alex, B.; Clavey, N.; Martinez, J.; Ducros, V. Simultaneous analysis of retinol, six carotenoids, two tocopherols, and coenzyme Q10 from human plasma by HPLC. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020, 1151, 122158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julianto, T.; Yuen, K.H.; Noor, A.M. Simple high-performance liquid chromatographic method for determination of alpha-tocopherol in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1999, 732, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, R.; Seitz, S.; Delvoux, B.; Greiling, H. Two high performance liquid chromatographic methods for the determination of alpha-tocopherol in serum compared to isotope dilution-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1997, 35, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi, B.; Lazzarino, G.; Leone, P.; Amorini, A.M.; Bellia, F.; Janson, C.G.; Di Pietro, V.; Ceccarelli, L.; Donzelli, S.; Francis, J.S.; et al. Simultaneous high performance liquid chromatographic separation of purines, pyrimidines, N-acetylated amino acids, and dicarboxylic acids for the chemical diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polson, C.; Sarkar, P.; Incledon, B.; Raguvaran, V.; Grant, R. Optimization of protein precipitation based upon effectiveness of protein removal and ionization effect in liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2003, 785, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkowicz, M.J.; Karpinska, J. Analytical problems with the determination of coenzyme Q10 in biological samples. Biofactors 2013, 39, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Shen, M.; Yu, T.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, B.; Zou, J.; Zhang, M. Liquid chromatography as candidate reference method for the determination of vitamins A and E in human serum. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezaal, E.; Mohammed, M.; Ahmed, K. Review: Determination of vitamin E concentration in different samples. IBN AL-Haitham J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2023, 36, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, E.I.; Magda, E.; Hanaa, S.; Mahmoud, M.S. Overview on liquid chromatography and its greener chemistry application. Ann. Adv. Chem. 2021, 5, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellinger, A.P.; Carr, P.W. Isocratic and gradient elution chromatography: A comparison in terms of speed, retention reproducibility and quantitation. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1109, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górnaś, P.; Baškirovs, G.; Siger, A. Free and Esterified Tocopherols, Tocotrienols and Other Extractable and Non-Extractable Tocochromanol-Related Molecules: Compendium of Knowledge, Future Perspectives and Recommendations for Chromatographic Techniques, Tools, and Approaches Used for Tocochromanol Determination. Molecules 2022, 27, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorja, A.; Medala, P.; Madhavi, M.; Meghana goud, G. A Review on Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography. Saudi J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.; Shushan, B. Clinical Applications. In Tandem Mass Spectrometry—Applications and Principles; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M. HPLC detectors: A brief review. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Techno. 2010, 33, 1130–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Das, P. Reverse Phase High-performance Liquid Chromatography: A Comprehensive Review of Principles, Instrumentation, Analytical Procedures, and Pharmaceutical Applications. J. Prev. Diagn. Treat. Strateg. Med. 2025, 4, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkaya-Miloglu, F.; Kadioglu, Y.; Senol, O.; Yaman, M.E. Spectrofluorimetric Determination of α-Tocopherol in Capsules and Human Plasma. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 75, 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, S.; Desai, D. Analytical method validation: A brief review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamna, F.; Spriano, S. Vitamin E: A Review of Its Application and Methods of Detection When Combined with Implant Biomaterials. Materials 2021, 14, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.