1. Introduction

The housing deficit in developing countries, such as Brazil, is a continuous and multifaceted issue that most severely impacts the population living in conditions of socioeconomic vulnerability. Brazil’s housing shortage reached six million units in 2022 [

1], representing the most recent official data released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), an agency of the federal government. This information is strategically employed by the Brazilian Ministry of Cities to plan, execute, monitor, and evaluate the National Housing Policy. Specifically, these figures are crucial for gauging the magnitude of the problem and establishing governmental production targets for new housing units and housing improvements, while also ensuring a more equitable and efficient regional distribution of financial resources toward areas with the greatest housing needs. For instance, the regional heterogeneity of the Brazilian housing deficit is pronounced: it is characterised by the predominance of precarious housing in the North Region [

2], which has the highest relative need. Conversely, the Southeast Region, which is the focus of this study, faces a deficit of a distinct structural nature, yet contains the largest absolute number of affected households. This disparity necessitates a decentralised and differentiated financial resource allocation, requiring the calibration of housing policy instruments to justly and efficiently mitigate regional deficiencies, in accordance with the distinct socioeconomic and demographic specificities of each region.

This alarming figure reveals only part of the problem, which can be unfolded in two dimensions, the quantitative (shortage of housing units) and the qualitative, which is related to the inadequacy of housing conditions. The latter dimension is more prominent—approximately four times greater—and includes houses with structural damage, lack of urban infrastructure (e.g., water supply), or unhealthy living conditions [

3].

This problem stems from technical, economic, and operational factors that have historically undermined the construction quality of developing countries, such as Brazil. In parallel, the construction industry in such countries faces challenges like the skilled labour gap, the scarcity of resources, and a usual cost-cutting culture [

4], which, combined with inefficient regulatory and inspection bodies, fails to ensure minimum standards of safety, durability, and habitability [

1]. In this context, the lack of public policies contributes to the perpetuation of the housing deficit. In contrast, well-structured public policies would serve as corrective instruments that, if properly planned and implemented, could mitigate the effects of the structural deficiencies in the construction sector.

Given this scenario of technical and functional fragility, it becomes urgent to rethink the methodologies used in the design and execution of housing problems, mainly associated with low-income populations. Low-cost solutions do not always meet standard requirements, as shown by [

5], and can fail to provide basic housing functionality (i.e., the capacity to accommodate daily domestic uses efficiently and comfortably). In fact, social housing design has been neglected in projects that overlook criteria related to usability, circulation, minimum furniture requirements, and user comfort. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt methodologies capable of improving project quality from the early stages, reducing design errors and supporting the decision-making process, rather than blindly choosing low-cost approaches. In this regard, Brazil has stood out among developing countries with research and federal government laws mandating the use of Building Information Modelling (BIM) in architectural and engineering projects, such as the National BIM Dissemination Strategy [

6] and Law No. 14,133/2021 [

7]. In fact, public authorities around the world are aware of the benefits of BIM implementation in public projects and are creating regulatory guidelines to force the Architectural, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) sector to adopt it [

8,

9,

10].

In Brazil, the new national strategy “Nova Estratégia BIM BR” aims to expand the adoption of Building Information Modelling across the public sector, targeting 99 federal agencies by 2027 and integrating BIM workflows into social housing programmes such as “Minha Casa, Minha Vida”, with at least 20 pilot projects planned by 2027 [

11]. These numbers illustrate the growing scale and institutional commitment to BIM-based housing policies, highlighting their potential to impact low-income families and enhance public sector efficiency.

BIM thus emerges as a proper methodology to potentially reverse this scenario, since it can be an appropriate technology to address such issues, as it has parametric, collaborative and quality control capabilities that can promote improvements in the logical flow of projects and work executions. According to ISO 19650-1 [

12], BIM entails the “use of a shared digital representation of a built asset to facilitate design, construction and operation processes to form a reliable basis for decisions.” Recent literature distinguishes between two complementary perspectives on this concept: a narrow and a broad approach. The narrow approach focuses on BIM as a digital modelling environment and semantic database that supports design and construction processes, while the broad approach conceives BIM as a socio-technical framework that integrates people, information systems, databases, and collaborative governance structures, extending its scope beyond technical modelling toward organisational and policy dimensions [

13]. Recent studies have shown that its application can contribute to the improvement in house functionality through the parametric modelling of 3D furniture objects that are already adjusted to the market availability and standard requirements [

5].

The concept of social technology refers to techniques and methodologies that interact with the population to solve social problems and improve living conditions. The main idea is community participation in the democratisation of knowledge and the search for sustainable, low-cost solutions. In this context, BIM, as a methodology/process that integrates different tools, data, and collaborative practices, enables the 3D visualisation of environments requiring renovation. Thus, BIM facilitates the process of creating 3D models, displaying possibilities in a user-friendly manner during the design phase as well as during construction. Therefore, BIM can contribute to social technology by participating in the decision-making process of government agencies, considering the desires and expectations of the community.

Recent evidence shows that digital technologies can either enable collaborative, citizen-empowering participation or consolidate more technocratic models, depending on governance design, trust, and data policies. Comparative cases from Helsinki and Copenhagen versus Dubai and Tokyo, as well as the Toronto Quayside experience, illustrate how privacy and data-governance choices shape deliberation quality and public engagement in urban initiatives [

14].

This study thus investigates the use of BIM methodology as a social technology to improve the governmental decision-making process in social housing programming. To this end, the authors carry out a literature review to better understand the state of the art related to studies that connect BIM with social purposes. After that, the present study proposes a workflow integrating BIM into housing improvement projects, focusing on the concept of social technology. Then, a case study is presented that applies the proposed process map, and the results of such implementation are obtained to develop a critical analysis of the BIM adoption in social housing programming, orientated to discuss its contribution to the core problem related to housing deficit in low-income countries. By providing access to the use of BIM by the population, through dissemination as a social technology, it is possible to use BIM to contribute to quantitative housing planning with urban-scale simulations or digital master plans in the future, allowing it to become a facilitator for solving problems related to the housing deficit.

2. Literature Review

To better understand the literature about BIM in the social housing context, this study carried out a systematic literature review (SLR) using the five steps established by Tranfield et al. [

15], which are, in brief: guiding questions; study location; study selection; analysis; and report. The research question was “How is BIM being used for social purposes in housing projects?” Thus, to locate the studies using the Scopus database, the following search terms were defined: “BIM” AND “social” AND “hous*”, with the asterisk functioning as a wildcard to include variations in the root, such as “housing”, “houses”, and “households”. Note that the terms were searched in the title, abstract, or keywords of the publications. To filter the results, some inclusion/exclusion criteria were defined: only journal articles published in the last five years in either English or Portuguese.

The search engine returned 51 studies, whose titles and abstracts were read, and, following inclusion/exclusion criteria related to the research area, 25 were removed, totalling 26 studies to carry out a literature analysis and report. It is worth pointing out that most studies are discussing energy-related issues (e.g., energy consumption, energy efficiency…), which are not directly linked to social purpose and, thus, were removed from the SLR. Also, some studies are related to heritage or historic BIM (HBIM), which is out of the scope of this SLR.

After a full reading of the 26 studies selected in the SLR, it was possible to observe four research areas in this macro topic: construction and design phases, energy performance, life cycle assessment, and evaluation of the existing conditions. The first group of studies is the most common and is represented by works that focus on digital modelling technologies applied in project management and development. The second research area, related to energy performance, includes papers that aim to target thermal efficiency and energy consumption to improve sustainability issues. The third identified research group brings together studies that consider not only environmental but also social and economic issues associated with the whole project lifecycle. The list of mapped studies in each research area is presented in

Table 1.

Some studies deal with post-disaster scenarios, promoting the BIM approach to enhance the decision-making process. For instance, Montalbano and Santi [

37] suggested that BIM methodology can be applied to temporary housing units to facilitate the reuse of components, carry out Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), and assess user comfort. In fact, Abu-Aridah and Henn [

19] showed, based on a case study using a refugee camp, that Construction 4.0 technologies, such as BIM, can be useful to optimise the design and management to result in more human and adaptable shelters.

Also on the theme of disaster management, Park and Seo [

38] studied the adoption of BIM methodology for structural damage mapping after seismic events. They explored BIM models combined with 3D scanning, which proved to improve the accuracy of structural damage mapping, especially in older buildings where there is a lack of construction documentation. Note that this work aimed to support decision-making strategies and risk assessment practices for buildings exposed to earthquakes.

Different from post-disaster scenarios, some studies from the selected sample are related to persistent challenges of social housing. For instance, Logsdon et al. [

5] carried out a study to understand the functional deficiencies in daily household tasks and used BIM methodology to develop parametric objects that could support architects to improve their design practices. Their study thus evaluated the construction market’s readiness to provide adequate furniture in social housing projects. This study highlights how the construction market is not fully prepared to support design practices that aim to maximise user satisfaction.

This focus on integrating user needs and building performance is also evident in studies related to developing countries. Silva et al. [

18] carried out a case study applying BIM in the maintenance management of social housing in Brazil. BIM use was orientated toward Building Energy Modelling (BEM), aiming to propose architectural layouts that better meet the user needs and the thermal performance requirements, defined by national standards, simultaneously. The study concluded that BIM adoption should be expanded to the post-occupancy phase, connecting energy efficiency and user satisfaction to maintenance management.

It was possible to observe from the SLR that the post-occupancy phase is also a recurring theme. Gonzalez-Caceres et al. [

8] studied the impacts of high humidity levels in social houses during the post-occupancy phase. Also, they adopted BIM methodology to digitally map deterioration processes in the buildings. Through the diagnostic analysis, they observed that moisture-related damage can be caused by inadequate thermal regulation, poor construction quality, and overcrowding in such houses. Together, these studies underscore the necessity of post-occupancy assessment as a tool for the continuous improvement of residents’ quality of life. While the aforementioned studies address the technical aspects, the decision-making process and its integration with residents is also explored in some studies. To address this point, for example, Baldauf et al. [

21], continuing the study developed by Tzortzopoulos et al. [

28], proposed a framework consisting of a map process and guidelines, supported by BIM-based tools, to standardise design assessment, improve communication, and enhance value generation. However, they do not explain the interactions involving government bodies.

Overall, the literature on BIM applied to social housing reveals a predominantly technical focus, centred on energy efficiency, environmental performance, and cost management. Only three studies [

20,

23,

33] directly address the participation of residents or the integration of their needs through BIM. Two other works propose conceptual frameworks with participatory potential, although without practical application. The remaining studies, while addressing social housing, do not incorporate mechanisms of active listening, institutional collaboration, or social inclusion in their approaches. This observation suggests a relevant gap in the field, which, although not addressed directly in this study, is recognised as significant and deserving of further exploration in future research.

Although the studies are organised into distinct thematic groups, a cross-cutting analysis reveals a common pattern: most applications of BIM in the context of social housing prioritise technical and environmental performance, with limited attention to participatory processes or institutional articulation. Even in studies that reference user needs or quality of life, such as in post-occupancy assessments or maintenance management, the role of residents is often treated passively or indirectly. Only a few works explore frameworks or methodologies that consider residents as active agents in the design or evaluation process. These insights underscore a structural gap in the literature and justify the relevance of further investigation into integrative workflows involving public institutions, academia, and the community, especially in contexts marked by complex bureaucratic structures and social vulnerabilities.

In this sense, the present study focuses on the integration process connecting public bodies with house residents through bureaucratic processes and third parties, such as universities, to support the design process. While the study did not involve experimental procedures requiring formal ethical approval, all engagements with residents were guided by the principles of respect, beneficence, and justice outlined for community-based research, ensuring informed consent, confidentiality, and adherence to local norms [

39].

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed methodology employs Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) to systematically organise BIM processes into traditional workflow. The key interfaces mapped are related to public agencies, civil society, and designers—represented in this study by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Through understanding the information exchange between players, this methodology aims to optimise decision-making processes. Note that the proposed workflow was tested using Brazilian context and self-built communities and may need to be adapted to other contexts.

Thus, in the next sections, the proposed workflow is described, including the process maps.

3.1. Stakeholder Integration Process

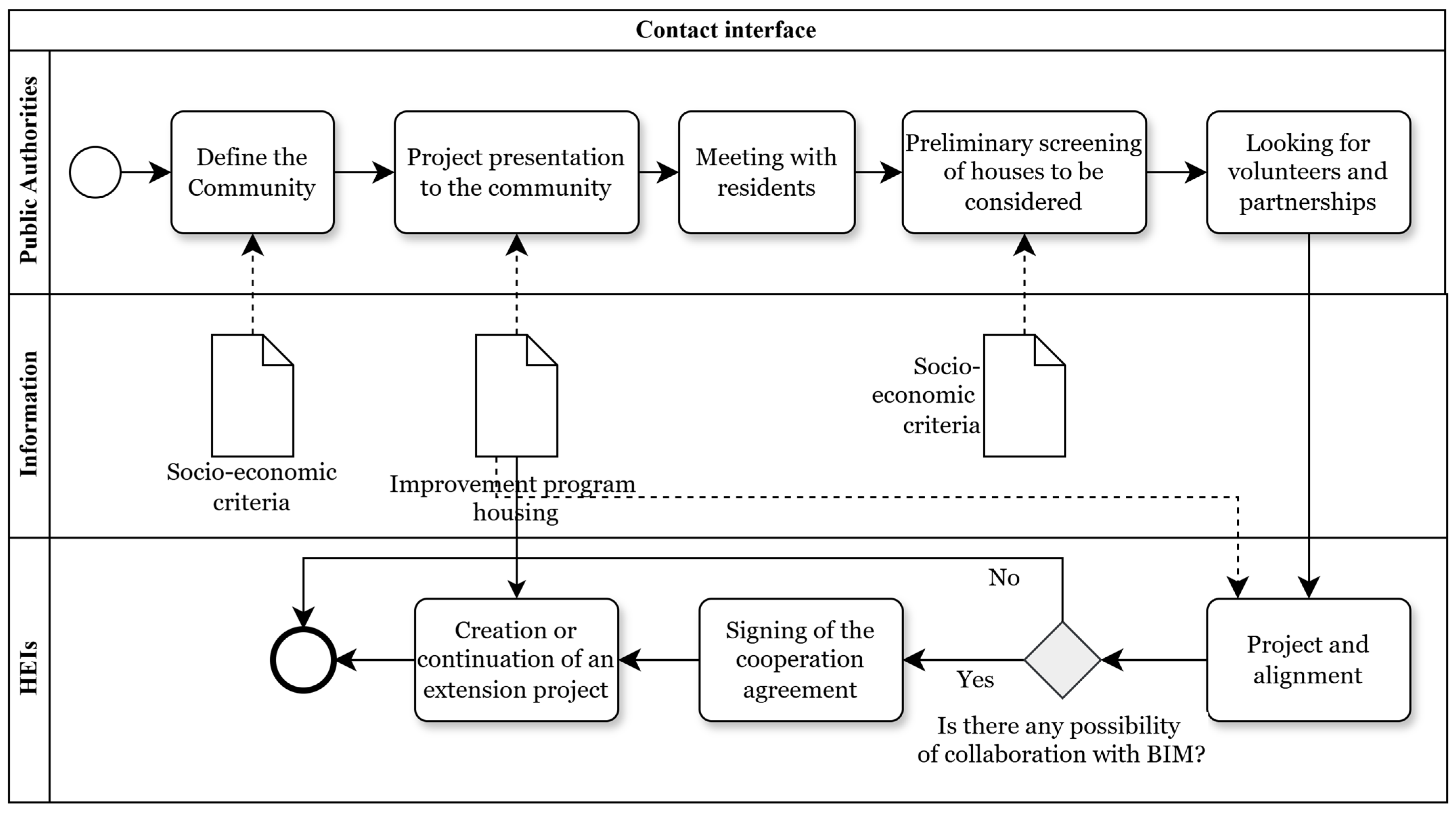

The first BPMN diagram (

Figure 1) shows the initial interface, involving the public bodies (e.g., municipal governments) and HEIs. In this process map, the process starts with the identification of the urban communities that require housing improvements, which rules are defined by public agencies based on macro-socioeconomic criteria, such as high-risk area classification and per capita income. For example, a dense community with a high risk of land erosion is prioritised.

After this definition, the public authorities present the housing improvement programme to the families that were selected, outlining its technical, social, and participatory scopes. At this stage, it is crucial to explain the deadlines and parties that will be involved in the project, to align the expectations and avoid future frustrations. Subsequently, the families are gathered for informational meetings, and triage is conducted to understand the design sequence that must be followed. This triage is based on micro-socioeconomic criteria such as:

Household income below three minimum wages;

Registration in the federal income support system;

Female-headed households, elderly occupants, or people with disabilities.

Following the establishment of the government–community interface, design and construction partnerships can be established. Aiming to apply this process map to a case study, this work proposed HEIs as third parties. The HEIs then evaluate the feasibility of collaboration through BIM implementation. In a positive case, a cooperation agreement must be signed, and the third party initiates the housing improvement project. Without a formal document establishing the collaboration using BIM, the proposed workflow ends and may be restarted with a new opportunity in the future. It is important that the public authority has a project team with previous experience in BIM projects, having skills to not only handle the models but also to edit them and coordinate the BIM workflow. Therefore, the lack of a skilled labour force, for instance, may block BIM adoption in this workflow.

3.2. Initial Activities

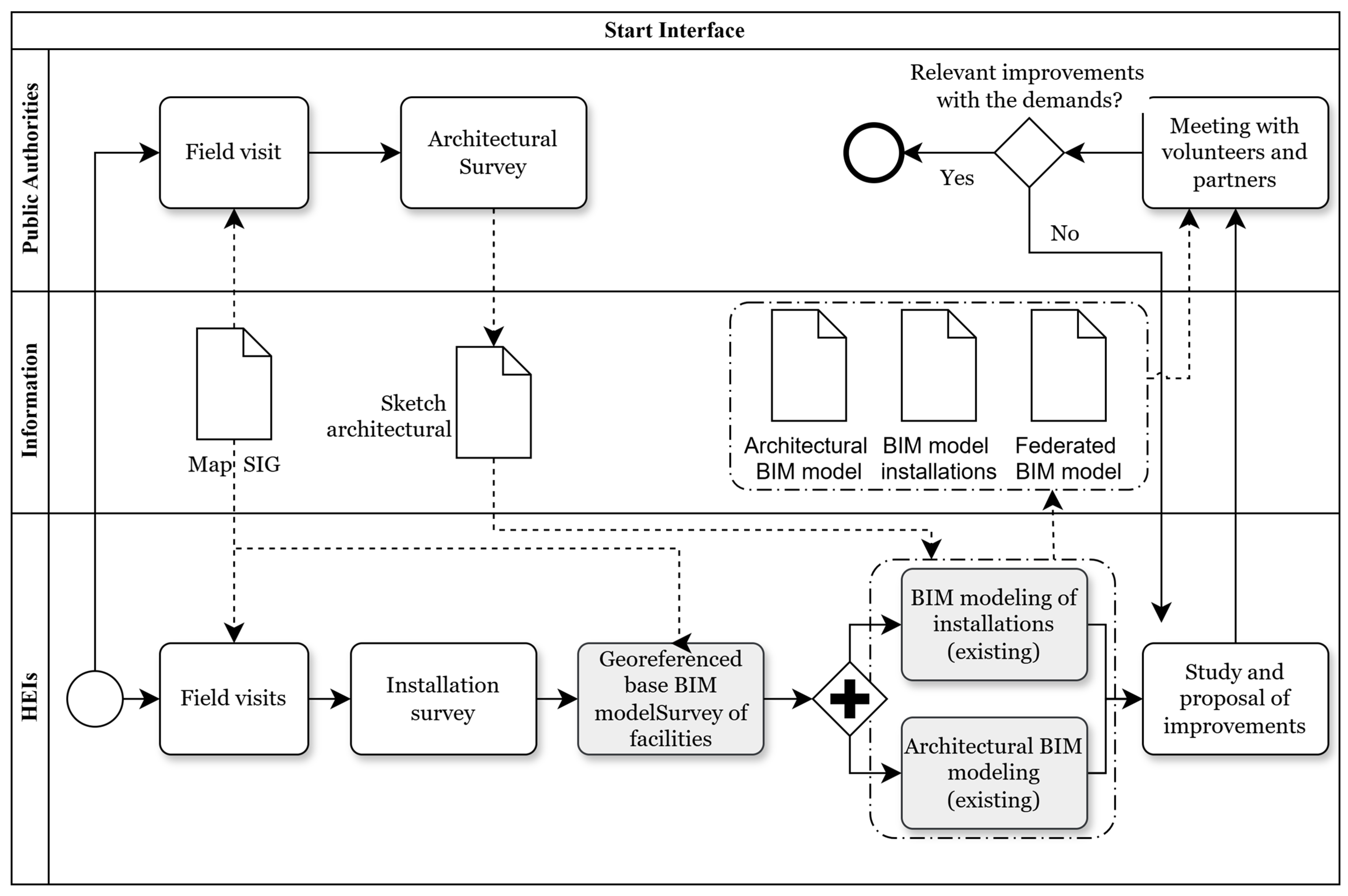

The second process map, presented in

Figure 2, shows the interactions between the government and the third parties (HEIs) post-stakeholder contact. Thus, it details the moment in which the site visits occur to provide a better understanding of the selected communities and the residences that will be reformed. Through this in loco investigation, the task team can map community dynamics and collect data from architectural and engineering surveys, such as building systems and damaged walls. It is important to note that this is the first instance of contact between the family and the third parties, which can create positive expectations for the families regarding the next steps. This moment is also important to connect the designers with the families, aiming to generate better design decisions through critical thinking induced by the experienced context.

As a result of the site visit, the initial deliverables are developed. They are mainly building sketches, including the existing conditions and integrating with public databases (topography, roads, etc.). After that, the third parties (HEIs) start the BIM modelling process based on the georeferenced site data. The architectural and engineering models are produced in parallel and integrated by a federated model.

The federated model was created based on a georeferenced model, which contains the topographic surface, orthophoto, and public utility systems for water supply, sanitary sewage, and electricity. Models from different disciplines were then appended to this georeferenced model to check for conflicts between them and to assess compatibility with the existing site information. If any interference was detected, the issue was resolved by the responsible party, and the revised model was updated to the federated model.

Therefore, this phase defines the first BIM use, converting the documentation generated by the site visit to digital shared models, thereby improving the information management compared to traditional methods. In the proposed method, the public agencies will have, thus, a better understanding of the real conditions of the selected houses to support the decision-making process, i.e., BIM acts as a social technology connecting the government to the people.

3.3. Design Proposals

The third mapped phase (

Figure 3) consists of detailed modelling and delivery processes. It includes, thus, the BIM modelling of house improvements, quantities takeoff for direct cost budgeting, and budget report and review. In this phase, the public party will check if the budget is aligned to the authorised cost per house unit. If it is over the authorised budget, the third party (HEI) revises the project to optimise the design cost, testing alternative solutions or removing non-prioritised improvements.

In case of positive feedback from the public party, the BIM models are approved and ready to be presented to families. Traditionally, the house design is presented using CAD drawings, usually in 2D projections. However, in the present study, the proposed approach suggests that the project presentation be enhanced by humanised design enabled by BIM models. The concept of “humanised design” is structured around the intention of facilitating understanding of the project through more intuitive visual elements and simplified interpretations, which is essential to ensure that the digital model not only records technical data but also acts as a facilitator between technical knowledge and everyday use. This approach contributes to the democratisation of access to project information, facilitating understanding, engagement, and action by the different audiences involved. In addition, as discussed by Zhang and El-Gohary [

40], the humanisation of the design through the BIM model is no longer an optional choice but rather a natural extension of modelling aimed at the end user, in most cases with limited technical capacity, by integrating human values and stakeholder priorities directly into the building value analysis process.

To visualise the BIM models, the residents need to access a BIM viewer web platform, and to review it, they can comment directly on the same platform. In this sense, the review feedback will be integrated into the federated model for a better understanding by the design team. Also, the quantity take-offs are carried out to support the budgeting process.

This phase marks the second BIM use related to project visualisation, understanding, and communication. This step brings the residents closer to the design process and, indirectly, to the decision-making process. Thus, the BIM methodology can be understood as a social technology again by the connection between people and government decisions.

3.4. Post-Occupancy Monitoring

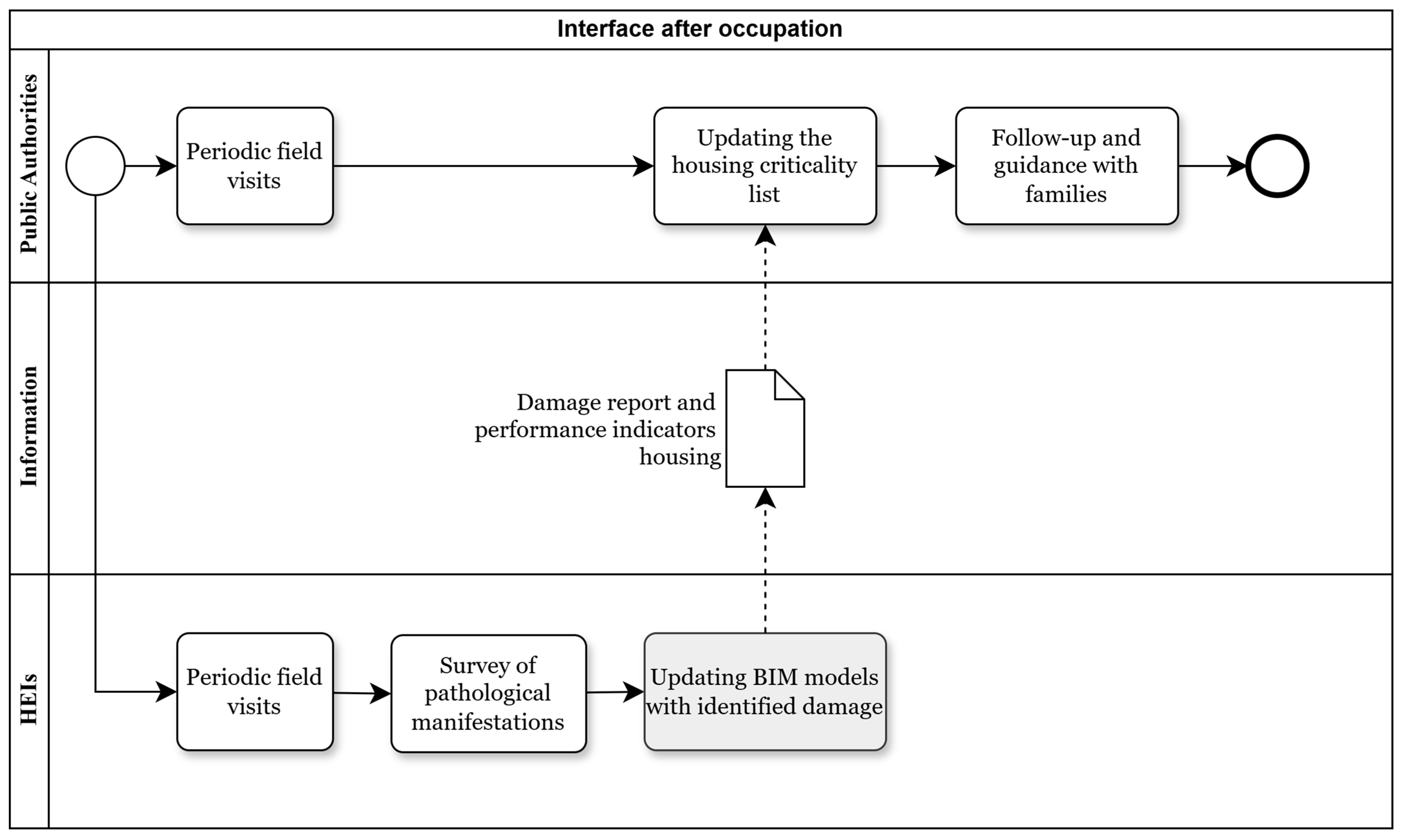

The final process map (

Figure 4) corresponds to the post-occupancy phase, following the implementation of the proposed design improvements. In this phase, the proposed method indicates that periodical site inspections are needed to identify pathological manifestations, such as moisture and structural cracks, to update BIM models with new house modifications, and to assess and evaluate the living conditions and house performance using climate indicators, such as dry and wet bulb humidity values.

It is important to highlight that house maintenance must be planned and executed by the residents, but the public agencies can support this process by providing updated BIM models and inspection reports. Also, this phase is crucial to ensure the sustainability of the adopted housing improvements, aligned with Gonzalez-Caceres et al. [

8].

Although the study developed by Gonzalez-Caceres et al. [

8] recognises the potential of updated BIM models to support building maintenance by residents themselves, the authors also highlight the existence of a significant gap between the technical data contained in the model and the ability of end users to interpret this data. In this sense, the Digital Housing Model (DHM) proposal can be understood not as a tool for direct use by residents, but as an information base that requires the involvement of intermediaries, such as community technical offices, trained residents’ associations, or university extension teams, capable of translating the technical language of the models into practical and understandable actions in the daily routine of housing management.

The idea of using BIM, even after the design and construction period, is mainly to reflect and distinguish the theoretical part from the practical part, through feedback from residents, which may include challenges in space dimensioning, poorly solved cross ventilation, presence of moisture, or infiltration. For example, in the case of poor ventilation, a comment about the lack of ventilation can be attached to the model and linked to the “bedroom window” and the designed ventilation system. For infiltration, a photo is attached to the element “wall X of room Y” in the 3D model. These items will be evaluated, confirming their relationship with the architecture of the houses and their location, so that they can later be inserted into the BIM model, in order to mitigate these mistakes. Once this is performed, it will be necessary to create parameters for the model to become “intelligent.” Based on the information collected, the BIM software, such as Autodesk Revit 2025, will be able to read and analyse this information. For example, a parameter called “State of Conservation” can be created with values such as “Good,” “Average,” and “Poor.” This allows problems to be viewed systematically and not just as isolated notes, enhancing future projects so that they do not make the same mistakes. It is important to note that this method was explored by Gonzalez-Caceres, so this is yet another study that reaffirms the importance of using BIM in post-construction in order to build homes that are more consistent with their locations.

As emphasised by the authors, the purpose of the DHM is to act as a tool to support public management, promoting continuous monitoring of building conditions and enabling the automated generation of alerts, maintenance reports, and operational guidelines for residents. Thus, it can be inferred that the BIM model, in its raw form, is not intended for direct use by lay users but rather for the construction of simplified interfaces and communication strategies that enable its indirect appropriation. Mediation between the technical model and the social reality of users is therefore essential for the benefits of BIM to be effectively perceived and incorporated in a sustainable manner into everyday housing practice.

4. Results and Discussion

The present study evaluated the proposed methodology through its application in a real-world case study conducted in a coastal city located in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil, with an estimated population of approximately 500,000 inhabitants and a demographic density of 3601.67 inhabitants per square kilometre. Within the proposed stakeholder framework, the public party was represented by the municipal government, while the third party corresponded to the HEI Fluminense Federal University (UFF). At the initial stage of the study, the municipal government selected the city’s most densely populated urban community to pilot the proposed methodology within the framework of a housing improvement programme. The selection of households was guided by predefined criteria related to social vulnerability and substandard housing conditions, as detailed in the methodology section. Accordingly, it is important to highlight that the selected area is predominantly composed of informal settlements, where most dwellings are self-built using masonry and wood, and where access to basic infrastructure and essential urban services remains significantly limited. In line with these parameters, a total of 23 housing units were selected for the intervention; these are indicated by black circles in

Figure 5.

To formalise the institutional partnership, a cooperation agreement was signed by both public and third parties involved in this house improvement project. It is important to officialise the interactions between the municipal government and HEI in a way that both teams must engage and dedicate efforts.

Following the cooperation agreement, field visits were planned to start the second phase of the proposed workflow. The site visit planning should include communication with the families and community leaders to align the best day and hour to visit their spaces. Also, it is important to ensure that there is no police operation occurring on that date, since it can put the design teams at risk.

Preceding the site visit, a GIS map is also developed, including all the selected residences, reference points (e.g., community centre), topography, risk areas, street layouts, and other relevant geographical information. The produced GIS map in this case study is illustrated in

Figure 5. This information was stored in .DWG files to better interoperate natively with the BIM models.

Therefore, on a site visit that took 4 h, the visual inspections revealed recurring critical house conditions (see

Table 2), which include:

Presence of moisture stains near openings;

Lack of mortar between bricks;

Absence of finishing coatings on walls;

Roof structures in precarious conditions, with visible holes;

Inadequate placement of cold water tanks;

Exposed plumbing installations at incorrect angles.

Following the visual inspection, architectural and engineering surveys were collected by the third party (HEI) to create the georeferenced information models of the existing conditions. It is worth pointing out that the models included the geometrical and non-material (e.g., material information) necessary for the next steps. Accordingly, the use of BIM at this step facilitates the understanding of house conditions among stakeholders.

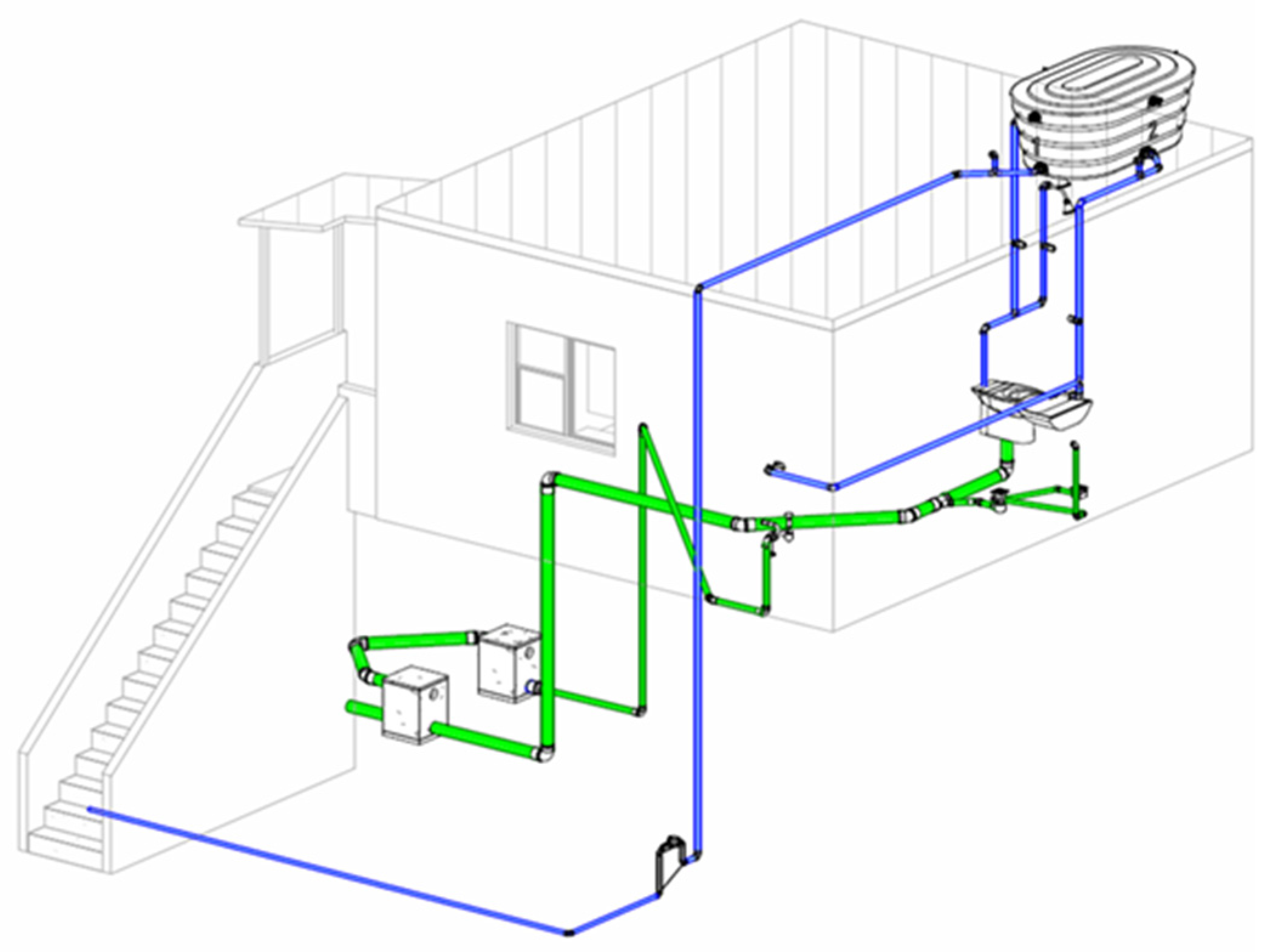

So, a set of priority improvement options was proposed based on the models and focused on criticalities and budget optimisation. Interventions included, for instance, proper repositioning of upper water reservoirs, repair of damaged plumbing connections and pipes, electrical circuit organisation, and correct routing of wastewater systems. Some of these proposals are illustrated in

Figure 6 through the BIM models.

The proposed house improvements were then reviewed and approved by the municipal institution. Following the design approval, information about budget codes was included in the models to enable automatic cost estimation that could be checked by the budget limit. In this specific project, the total cost established for each house unit could not exceed BRL 35,000 (approximately USD 7000). Therefore, the second BIM use was observed: to control precisely the intervention scope and budget.

The review process was conducted in a participatory manner, actively involving residents through the use of humanised design through BIM models. Access to the proposed designs was provided via Autodesk Viewer, a free web-based visualisation tool, which enabled transparent and inclusive engagement throughout the design validation phase. This process facilitated user-centred evaluations of spatial configurations and functional elements. For instance, in a specific house, the family used the 3D visualisation to point out that the proposed new location for the water tank would obstruct rooftop spaces used for laundry. Such end-user feedback informed the iterative refinement of the BIM models, ensuring alignment between user requirements and technical feasibility.

Once the design and budget were validated, traditional documentation was extracted from BIM models and submitted to the public party, which could communicate the residents about the final design and initiate bureaucratic procedures for the bidding processes related to the construction phase.

It is important to highlight that the integration of BIM as a social technology within this project demonstrated the potential to enhance government decision-making processes in the context of social housing programmes. Notable benefits included increased efficiency in housing diagnostics through comprehensive information models of existing conditions, improved project transparency due to enhanced communication and design comprehension among stakeholders, including residents, cost control, and data centralisation to support future monitoring and post-occupancy evaluation. In addition to these technical contributions, several social outcomes were observed, which reinforce BIM’s role as an instrument for inclusive urban development. These include:

increased trust in public housing programmes;

higher resident satisfaction with proposed interventions;

improved understanding of housing systems and their maintenance;

greater resident engagement and sense of ownership over the design process;

reduced resistance to implementation due to clearer communication and visualisation of design decisions.

Furthermore, the approach aligns with the principles of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly those related to inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities (SDG 11) and sustainable infrastructure and innovation (SDG 9), demonstrating that BIM adoption in this context can foster not only technical advancements but also meaningful and measurable social benefits.

5. Conclusions

As a result, this study corroborates the findings of the literature review, emphasising the potential of BIM methodology in the construction industry, particularly in social housing projects. As observed in the SLR results, new technologies such as BIM and 3D digitalisation have enhanced the management of construction materials due to the better precision in quantitative takeoffs from the design, which results in more accurate material orders, reduced waste, among other benefits that can be achieved from better quantitative estimation. Also, the literature review revealed that there is potential research area to use BIM as social technology tools, which was the aim of this study.

This case study, developed in collaboration with a municipality, HEI, and house residents, demonstrated that integrating BIM as social technology into government-led housing improvement programmes is feasible and effective, especially when the integration processes are mapped. By creating georeferenced information models of the existing conditions and proposed house improvements, the present study established a replicable workflow that can be a reference for future interventions in consolidated, self-built communities. It is important to highlight that the adoption of georeferencing process in BIM facilitated not only the creation of federation models but also prepared the models to be further integrated with the public database which are based on GIS platforms, such as QGIS 3.44.4. With such integration, the public authority will have a better digital database to develop risk assessments and site diagnosis.

The findings are aligned with those of previous studies highlighting BIM’s potential to increase the budget accuracy, reduce design errors, and ultimately enhance the overall quality of social housing projects.

In the Brazilian context, the use of the BIM workflow for the decision-making collaboration process has shown significant benefits in tailoring solutions to residents’ actual needs. The proposed approach continues this trend by proposing continuous updates of BIM models after project completion, which were not implemented in the present case study. This strategy establishes a robust database for post-occupancy monitoring and management, thereby supporting proactive maintenance and promoting the long-term functionality of house units, which can be further investigated in future studies. Therefore, the use of such information models in post-occupancy interventions is recommended as future work to understand how the construction data history can support future interventions.

Furthermore, the project revealed potential pathways for broader urban planning integration. The produced BIM models and associated databases may be incorporated into existing municipal strategies, such as city risk and resilience plans. This opens new perspectives for studies exploring the use of BIM as a central digital methodology in integrated urban resilience and risk management frameworks.

Despite these positive outcomes, some limitations were observed, particularly in data acquisition challenges and community engagement constraints during the initial diagnosis phase. Future studies should prioritise comprehensive participatory strategies and leverage mobile data collection technologies to streamline information-gathering processes.

Overall, the findings of this study contribute to the broader discourse on digital transformation in public governance, illustrating how BIM, when recontextualised as a social technology, can bridge the gap between technical innovation and social development.