Abstract

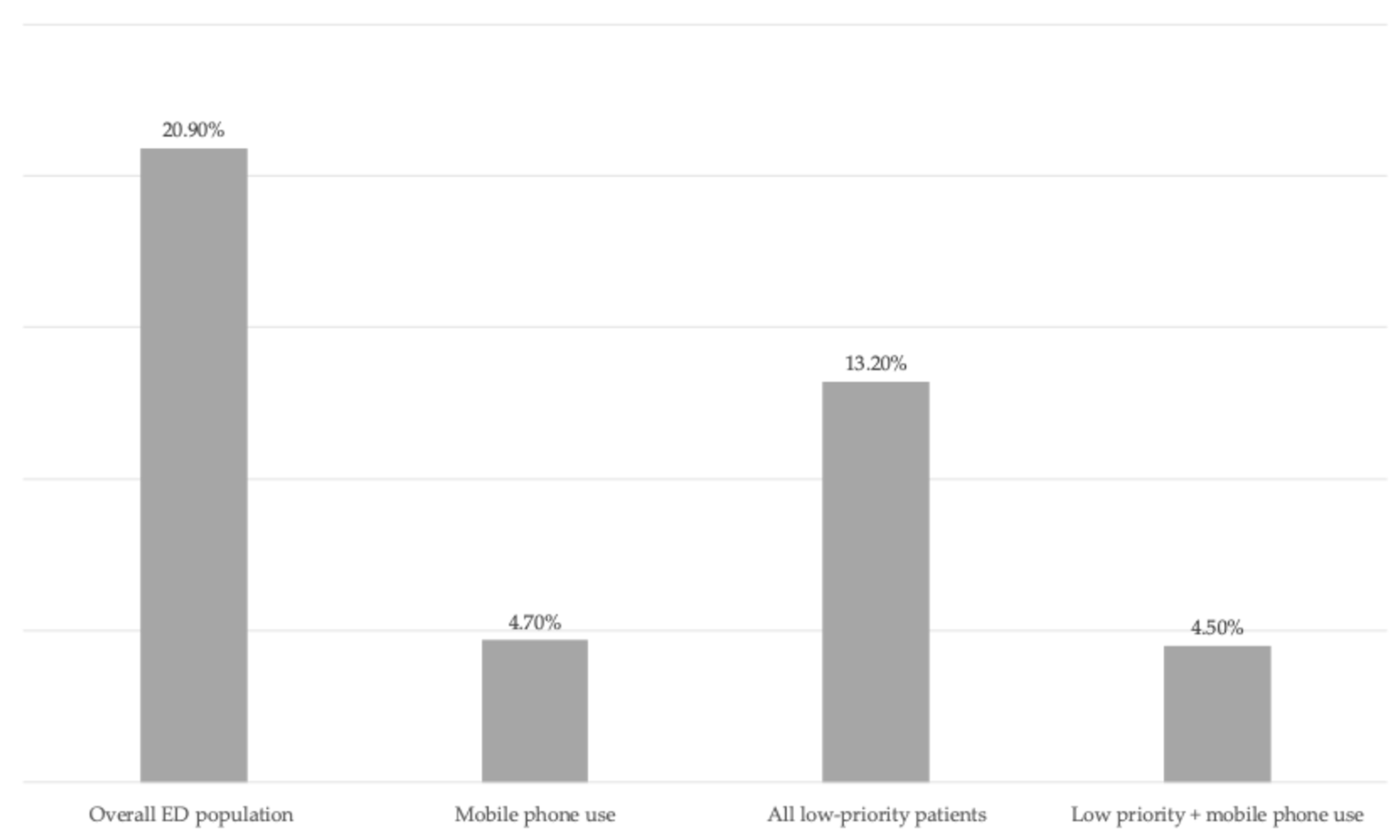

Background: Behavioural cues observed during emergency department (ED) triage may provide additional information on patient acuity. We conducted an exploratory pilot study to investigate whether mobile phone use observed during ED triage was associated with hospital admission. Methods: We performed a retrospective, single-centre study including all adult ED attendances between 1 January 2019 and 30 June 2025. Demographics, triage category, mobile phone use documented by nursing staff during waiting time, and hospital admission were extracted from the electronic health record. The primary outcome was hospital admission, with a secondary analysis restricted to low-priority triage categories. Results: Among 423,267 ED visits, the overall admission rate was 20.9%. Mobile phone use was documented in 171 patients (0.04%), of whom 4.7% were admitted (p < 0.001). In low-priority patients (n = 336,160), admission was 4.5% among those using a phone compared with 13.2% overall (p = 0.001). Conclusions: Mobile phone use observed during ED triage was associated with lower hospital admission rates and may represent a simple behavioural adjunct to conventional triage assessment.

1. Introduction

Patient behaviours in the emergency department (ED) waiting area can provide valuable insights into clinical acuity [1]. Observable actions, such as engagement with a personal mobile device, may reflect preserved attention, motor coordination, and the absence of acute distress—features often incompatible with severe illness [2]. Recognizing these cues could support triage nurses in identifying lower-risk patients more efficiently. Recent research has highlighted the potential of behavioural indicators to complement conventional triage parameters. Studies suggest that subtle non-verbal cues and patient actions can help predict adverse outcomes and guide prioritization in the ED. While previous work has focused on facial expressions, posture, or responsiveness, the role of mobile phone use as a behavioural marker has not been extensively explored [3,4].

Recent research has begun to explore the relationship between patient mobile phone use in the ED and disposition outcomes. For example, a prospective cross-sectional study observed that patients actively using their cell phones at initial assessment had significantly higher rates of ED discharge compared with those who were not, indicating that cell phone engagement may correlate with lower acuity or clinical severity. To our knowledge, however, no previous studies have specifically evaluated the association between mobile phone use observed during ED triage waiting periods and subsequent hospital admission rates.

Mobile phone use during triage could represent an easily observable, immediate signal of patient stability. Patients actively engaging with their devices are unlikely to be experiencing severe respiratory distress, altered consciousness, or intense pain—conditions typically associated with higher acuity and hospital admission. Building on this concept, we hypothesized that mobile phone use observed at triage may be associated with lower hospital admission rates. Accordingly, this exploratory pilot study aimed to evaluate this association in a large, unselected cohort of adult ED patients, providing preliminary, hypothesis-generating evidence on the potential utility of behavioural cues in augmenting triage assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective, single-centre observational study at the ED of Cuneo, north-western Italy, including all adult patients (≥18 years) presenting between 1 January 2019 and 30 June 2025. The ED operates a five-level triage system based on local protocols informed by national and international guidelines for emergency care, including principles similar to those in the Emergency Severity Index. Triage aims to prioritize patients according to urgency, considering presenting complaints, vital signs, and risk of deterioration. Codes 1–2 correspond to high-priority patients requiring immediate or urgent evaluation, while codes 3–5 are considered low-priority, encompassing semi-urgent and non-urgent cases. Triage is performed exclusively by trained nursing staff, following institutional protocols and guidelines. Nurses use structured assessment and professional judgment to assign priority codes, which guide resource allocation and initial patient evaluation.

The ED operates 24/7, and all triage assessments are performed by trained nursing staff following institutional protocols. For this retrospective study, patient data—including demographics, triage category at presentation, and hospital admission outcome—were extracted from the electronic health record. Documentation of mobile phone use was discretionary and recorded by nursing staff during triage or subsequent waiting periods only when actively observed, while all other data were routinely recorded as part of standard clinical care. No prospective data collection was performed; the study relied entirely on existing electronic records. Left without being seen (LWBS) was defined as patient departure from the ED prior to medical evaluation.

The primary outcome was hospital admission. A secondary analysis focused on patients triaged as low priority, defined according to institutional protocol.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. Proportions were compared using chi-squared tests. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using R (R 4.0.0 GUI 1.71 Catalina build, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The identity of the patients was kept anonymous, and the data were treated confidentially.

3. Results

During the study period, 423,267 ED visits were recorded. The overall hospital admission rate was 20.9%. Mobile phone use during triage or subsequent waiting time was documented in 171 patients (0.04%). Characteristics of patients with documented mobile phone use are summarized in Table 1. The median age of these patients was 34 years (interquartile range 25–48), and the male-to-female ratio was 1:1. Among patients observed using a mobile phone, 4.7% were admitted to the hospital, compared with 20.9% in the overall ED population (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with documented mobile phone use.

In patients with documented mobile phone use, 71.3% were Italian nationals, while 28.7% were of foreign nationality. Arrival via emergency medical services occurred in 29.2% of cases. No patients admitted from this subgroup required intensive care or sub-intensive care unit admission. Left without being seen was recorded in 12.9% of patients. The most frequent presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (16%), non-specific low back pain (13%), headache (12%), and chest pain (9%).

When the analysis was restricted to low-priority patients (triage codes 3–5; n = 336,160), 155 patients had documented phone use, with an admission rate of 4.5% versus 13.2% in the entire low-priority group (p = 0.001). Hospital admission rates according to mobile phone use are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hospital admission rates according to mobile phone use and triage priority.

4. Discussion

In this large, single-centre cohort, mobile phone use observed during emergency department (ED) triage was associated with substantially lower hospital admission rates. This finding suggests that engagement with a personal device may serve as a proxy for preserved cognitive and motor function and relative clinical stability [5]. Notably, none of the admitted patients in the mobile phone use group required intensive or sub-intensive care, further supporting the interpretation of mobile phone engagement as a marker of lower clinical severity.

The literature increasingly recognizes the value of behavioural cues—such as mobility, responsiveness, and patient narrative—in augmenting risk stratification and supporting clinical decision-making in triage [6,7].

Patient safety during triage is influenced by multiple factors, including nurse experience, workload, and the ability to interpret both objective and subjective information. While traditional triage systems rely heavily on vital signs and structured algorithms, observational data indicate that nurses also incorporate visual and behavioural cues, sometimes subconsciously, to inform urgency assessments [8]. However, variability in triage performance and interrater reliability remains a challenge, with established systems demonstrating moderate to good validity but inconsistent sensitivity for critical illness and adverse outcomes [9,10].

The integration of digital technologies, such as mobile self-registration and symptom assessment apps, has shown promise in streamlining pre-triage flow and reducing waiting times [11]. Mobile platforms offer greater flexibility and usability compared to fixed kiosks, with higher satisfaction among both patients and staff. Nevertheless, digital triage tools exhibit high sensitivity for identifying high-acuity cases but may suffer from poor concordance with nurse-assigned scores and elevated over-triage rates, limiting their standalone utility in busy EDs [12]. The safety of self-triage apps is generally comparable to telephone triage, but further research is needed to validate their impact on patient outcomes and operational efficiency in real-world settings [13].

The use of wearable devices and continuous monitoring has been proposed as a means to dynamically assess patient status during ED waiting periods, potentially reducing the risk of missed deterioration. However, widespread adoption of such technologies is limited by practical and logistical barriers [14].

In summary, observable patient behaviours such as mobile phone use, combined with digital innovations, represent promising adjuncts to conventional triage assessment. These approaches may enhance the early identification of low-risk patients and optimize resource allocation. However, challenges in documentation, reliability, and integration into existing workflows persist. Future research should focus on prospective validation of behavioural markers, standardization of digital triage tools, and evaluation of long-term outcomes to ensure safe and effective implementation in diverse ED environments.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Documentation of mobile phone use was rare and discretionary, likely underestimating its true prevalence. The retrospective, single-centre design limits generalizability, and we did not adjust for potential confounders such as comorbidities or presenting complaints. Additionally, variability among nursing staff over the study period may have affected documentation.

It is important to emphasize that this study is exploratory in nature. The aim was to suggest that certain patient behaviours, such as mobile phone use during ED triage, may provide additional, easily observable information about clinical acuity. Despite these limitations, the observed association remained statistically significant in both the overall and low-priority cohorts.

In conclusion, mobile phone use at triage may serve as a simple behavioural adjunct to conventional assessment. Future prospective multicentre studies are warranted to validate these findings and explore the integration of behavioural markers into standardized triage models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.G., B.M., and F.D.; methodology, J.D.G. and S.D.; software, J.D.G.; validation, M.G. (Mauro Giraudo), P.V., and M.G. (Marco Garnero); formal analysis, J.D.G. and S.D.; investigation, M.G. (Mauro Giraudo) and F.D.; resources, M.G. (Mauro Giraudo) and G.L.; data curation, P.V., M.G. (Marco Garnero), and G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.G., B.M., and F.D.; writing—review and editing, M.G. (Marco Garnero) and S.D.; visualization, P.V., M.G. (Marco Garnero) M.G. (Mauro Giraudo); supervision, G.L.; project administration, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). It is a retrospective observational study based on anonymized data collected as part of routine clinical care. According to local institutional policies and internal research governance procedures, formal approval was not required for this specific type of study. The study protocol was reviewed and authorized by the hospital medical administration. All data were fully anonymized prior to analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and observational nature of the study and the use of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| ED | Emergency Department |

| LWBS | Left without being seen |

References

- Gorick, H.; McGee, M.; Wilson, G.; Williams, E.; Patel, J.; Zonato, A.; Ayodele, W.; Shams, S.; Di Battista, L.; Smith, T.O. Understanding triage assessment of acuity by emergency nurses at initial adult patient presentation: A qualitative systematic review. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 71, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, W.; Xenochristou, M.; Sui, E.; Ruan, E.; Ribeira, R.; Dash, D.; Srinivasan, M.; Artandi, M.; Omiye, J.A.; Scoulios, N.; et al. Hospitalization prediction from the emergency department using computer vision AI with short patient video clips. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, S.I.; Jacobson, A.; Moore, G.P.; Frank, J.; Gifford, W.; Johnson, S.; Lazaro-Paulina, D.; Mullan, A.; Finch, A.S. Airway, breathing, cellphone: A new vital sign? Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 17, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis Hunter, A.E.; Spatz, E.S.; Bernstein, S.L.; Rosenthal, M.S. Factors Influencing Hospital Admission of Non-critically Ill Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Worster, A. Predictors of admission to hospital of patients triaged as nonurgent using the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 15, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekonja, Z.; Kmetec, S.; Fekonja, U.; Mlinar Reljić, N.; Pajnkihar, M.; Strnad, M. Factors contributing to patient safety during triage process in the emergency department: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5461–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscoe, L.A.; Eisenberg, E.M.; Forde, C. The Role of Patients’ Stories in Emergency Medicine Triage. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald, G.; Jelinek, G.A.; Scott, D.; Gerdtz, M.F. Emergency department triage revisited. Emerg. Med. J. 2010, 27, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, E.E.; Blakely, B.; Tufanaru, C.; Selwood, A.; Braithwaite, J.; Clay-Williams, R. Strategies to measure and improve emergency department performance: A scoping review. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2020, 28, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariasse, J.M.; Van Der Hagen, V.; Seiger, N.; Mackway-Jones, K.; Van Veen, M.; Moll, H.A. Performance of triage systems in emergency care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammila-Escalera, E.; Greenfield, G.; Aldakhil, R.; Mak, H.M.; Sehgal, H.; Neves, A.L.; Harmon, M.J.; Majeed, A.; Hayhoe, B. Safety and Efficacy of Digital Check-in and Triage Kiosks in Emergency Departments: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, I.H.; de la Torre Díez, I.; López-Izquierdo, R.; Villamor, M.A.C.; Martín-Rodríguez, F. Mobile Triage Applications: A Systematic Review in Literature and Play Store. J. Med. Syst. 2021, 45, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotte, F.; Mueller, T.; Gilbert, S.; Blümke, B.; Multmeier, J.; Hirsch, M.C.; Wicks, P.; Wolanski, J.; Tutschkow, D.; Brittinger, C.S.; et al. Safety of Triage Self-assessment Using a Symptom Assessment App for Walk-in Patients in the Emergency Care Setting: Observational Prospective Cross-sectional Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e32340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nino, V.; Claudio, D.; Schiel, C.; Bellows, B. Coupling wearable devices and decision theory in the united states emergency department triage process: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.