Abstract

This work presents the development of a differential-drive wheeled mobile robot educational prototype, manufactured using 3D additive techniques. The robot is powered by an embedded ARM-based computing system and uses open-source software. To validate the prototype, a trajectory-tracking task was successfully implemented. The aim of this contribution is to provide an easily replicable prototype for teaching automatic control and related engineering topics in academic settings.

1. Introduction

Wheeled mobile robots have recently become highly relevant in education, research, and industry. Their mechanical simplicity and versatility make them ideal platforms for hands-on exploration of fundamental concepts like kinematics, control, perception, and programming. In research, wheeled mobile robots are often used as testbeds to validate localization, trajectory planning, navigation, and cooperation algorithms. This work introduces an educational prototype of a differential wheeled mobile robot, highlighting its novel educational utility. The most relevant contributions in this area are presented below.

The literature related to educational differential wheeled mobile robots includes contributions in the following categories: educational prototypes and platforms for general robotics teaching [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]; the use of robots in STEM projects and active learning [16,17,18,19]; and experimentation, control, and programming of educational robots [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The tasks typically addressed in the context of education or research include environmental cleaning and maintenance [1,10,16], as well as autonomous navigation and trajectory tracking [13,18,22,26,27]. Regarding programming approaches, the reported methods include block-based programming [4,6,14,19,23], textual programming (Arduino, C/C++, Python, MicroPython, ROS, etc.) [1,2,3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,29], and hybrid approaches [3,4,6,8,23]. Regarding the types of platforms employed, studies report the use of commercial robots [1,3,18,21,24], custom-built robots [2,5,6,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,22,26,27,28,29], and mixed platforms [4,7,8,23]. Regarding the main processing unit, the most frequently reported devices are: Arduino [2,4,11,12,22,29], LEGO [1,3,18,21], Raspberry Pi [7,12,18], ESP32 [5,20,24,26,27], and Micro:Bit [6]. Regarding the robot structure, reported designs include commercial kits (injection-molded plastic, LEGO, Microbit) [1,3,6,18,21,24]; 3D-printed components [6,7,8,28,29]; low-cost commercial components [4,14,16,18,19,20,23]; and metallic structures [10,12,17,20].

Previous commercial and educational robots (such as LEGO platforms, Jetbot, and Duckiebot) present limitations related to structural robustness, motor durability, and cost. LEGO kits lack the mechanical strength required to incorporate advanced sensors or support more complex experimentation; Jetbot uses plastic-geared motors that wear out with use; and Duckiebot is expensive for many institutions in Latin America. The proposed prototype overcomes these limitations by incorporating metal-geared motors that enhance durability, a 3D-printed chassis that enables structural customization, and a significantly lower total cost (approximately 250 USD), making it a more accessible and research-oriented alternative for robotics education.

On the other hand, the literature supports the technological decisions adopted in this prototype. 3D printing (primarily using PLA) has become a standard manufacturing method for educational robots, offering sufficient strength for academic applications, as discussed in [30]. It has also been demonstrated that the Jetson Nano can perform real-time AI inference with low latency, as shown in [31], making it a suitable embedded platform for robotics education and research. Furthermore, Python remains one of the most widely used languages in robotics education due to its extensive ecosystem of libraries for control, vision, simulation, and machine learning, as evidenced in [32]. These findings support the use of 3D printing, Jetson Nano, and Python in the proposed prototype.

Based on the review above, this work addresses the development of an educational prototype of a differential wheeled mobile robot. The intention is to use this prototype for undergraduate and graduate-level courses, as well as in research areas such as automatic control and artificial intelligence. A key feature of this prototype is its modular design, which allows for future functionality expansions by adding new hardware modules. For example, a camera can be added to perform vision-based tasks, and infrared sensors can be used for line-following applications. Additionally, as a custom-built solution, cost reduction was pursued, resulting in a prototype costing approximately $250 USD. This is significantly lower compared to commercial robots with similar capabilities, such as Jetbot [33], which ranges from $256 to $552 USD [34,35], or Duckiebot, priced at approximately $549 USD [36].

It is worth mentioning that these commercial robots [33,34,35,36] typically use plastic-geared motors, which are cheaper but less durable. In contrast, the proposed prototype uses metal-geared motors, which offer greater wear resistance and longer operational life. The robot structure is manufactured using additive techniques (3D printing), enabling easy modification when adding new hardware elements. For software, all codes are written in Python 3.12. Python offers a short learning curve, broad library support, a strong online community, and open-source licensing, which eliminates licensing costs. The main processing unit is the Jetson Nano development board, manufactured by NVIDIA. This embedded system is based on ARM architecture and has a GPU with 128 CUDA cores. These features support AI libraries and equip the robot with advanced processing capabilities for future applications.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the design of the differential wheeled mobile robot. Assembly instructions are provided in Section 3. Operational guidelines are presented in Section 4. Section 5 outlines the validation process of the proposed prototype. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions of this work.

2. Design

The prototype’s design consists of three main components: additive manufacturing, hardware, and software. The following sections detail each component and the bill of materials.

2.1. Bill of Materials

Table 1 lists the materials required to construct the wheeled mobile robot prototype.

Table 1.

Bill of materials.

Because several components are sold in bulk, some clarifications are necessary: the table lists only the exact quantities used. About 360 g of PLA filament is needed for manufacturing all robot structural parts. Only one glass marble (a small glass sphere) is required; however, it can be replaced with a metal sphere, although the latter has a higher cost. Around 1 m of each red and black 20 AWG silicone wire is used. The wire color is optional. Only eight screws are required. Two male XT60 connectors are needed. Finally, one USB-A-to-USB-C cable is used.

In Table 2, the design file summary is presented. The ‘archivo3D’ archive contains STL design files for 3D printing the robot’s structural parts: chassis base, chassis top cover, shaft couplings, and ball caster mounting. The ‘jetsonCode’ archive contains Python programs for implementing robot control and sensor integration. The ‘arduinoCode’ archive provides the firmware source code for the Arduino Nano microcontroller.

Table 2.

Design file summary (Please refer to the Supplementary Materials for details).

2.2. Additive Manufacturing

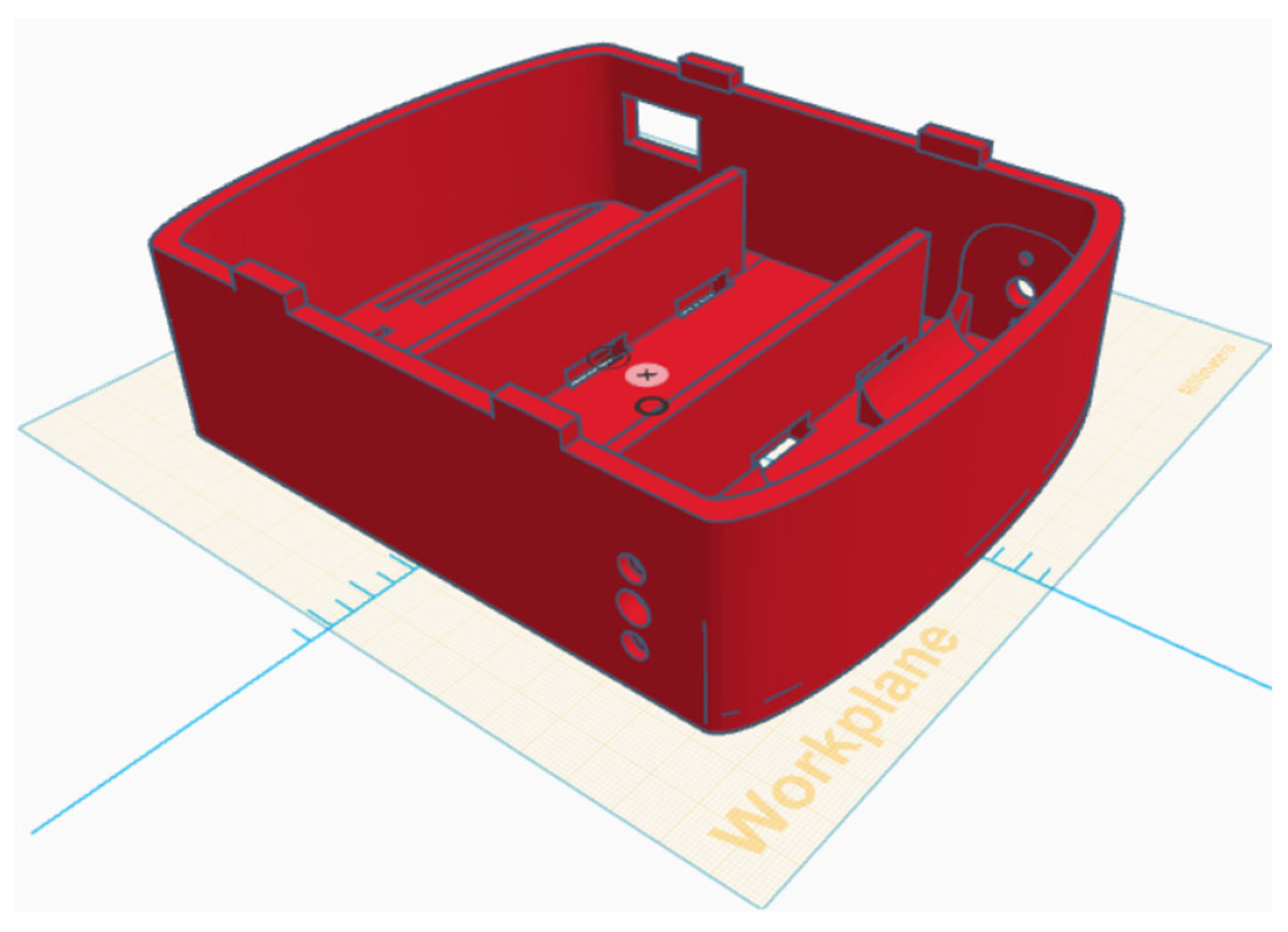

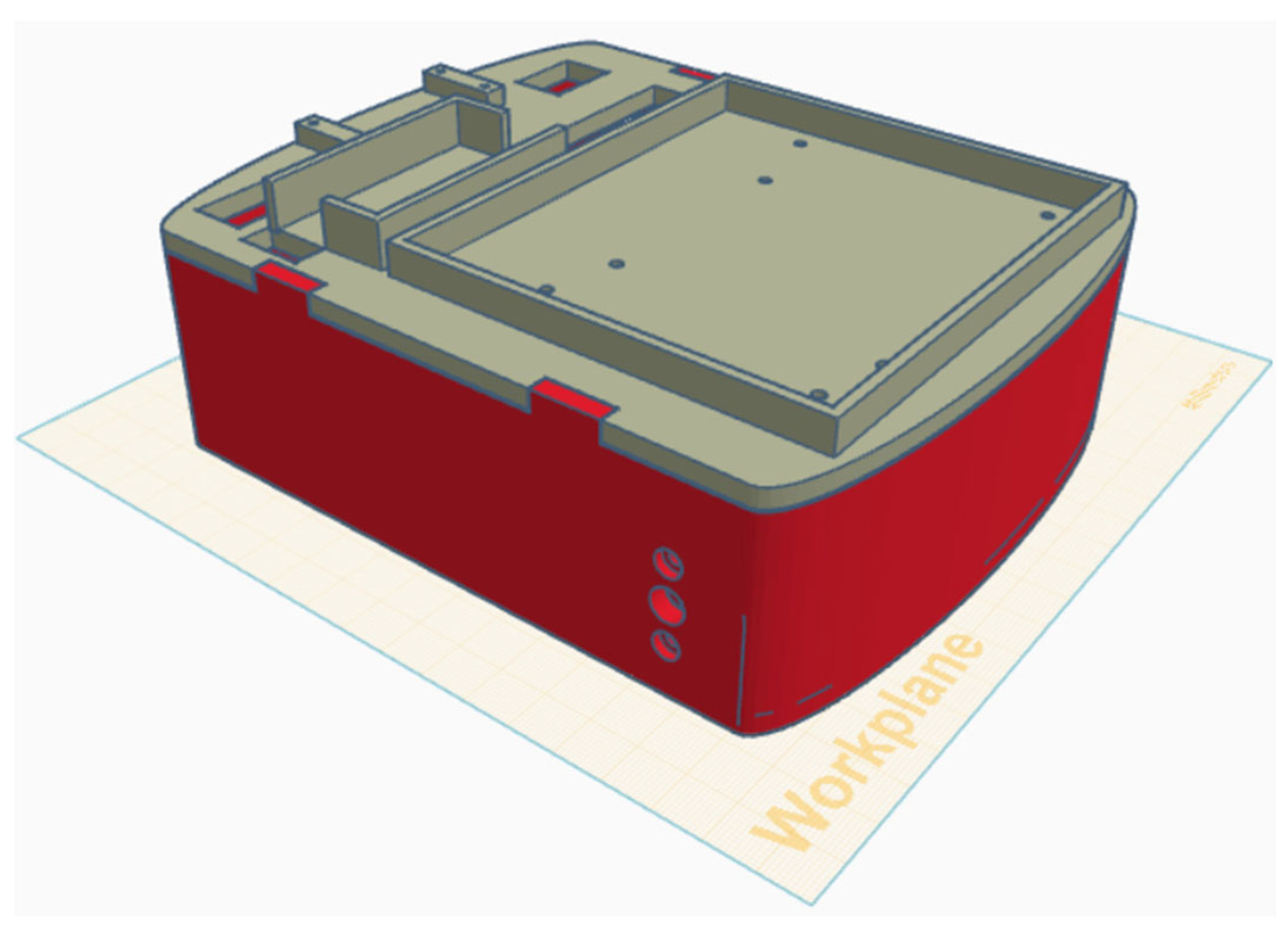

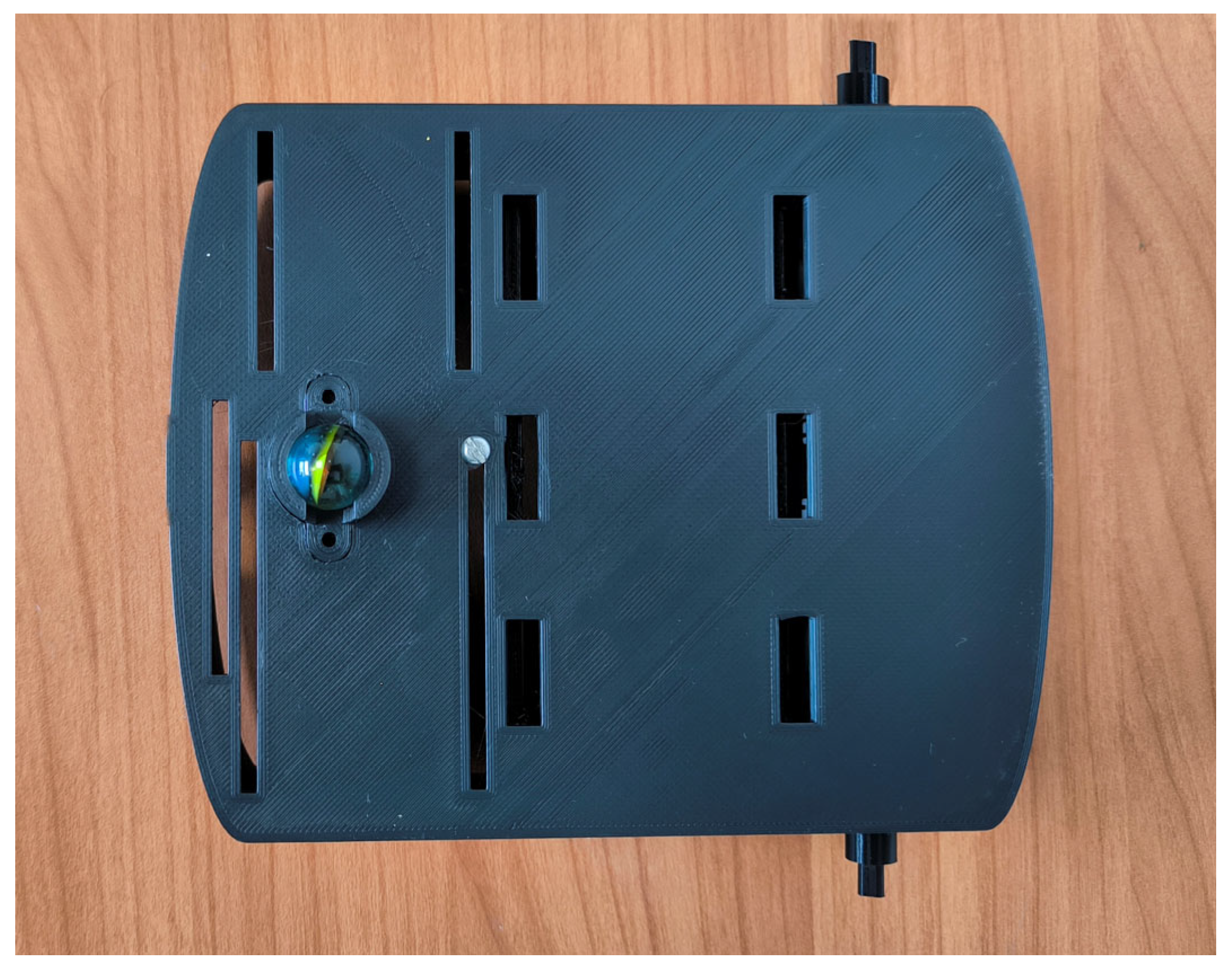

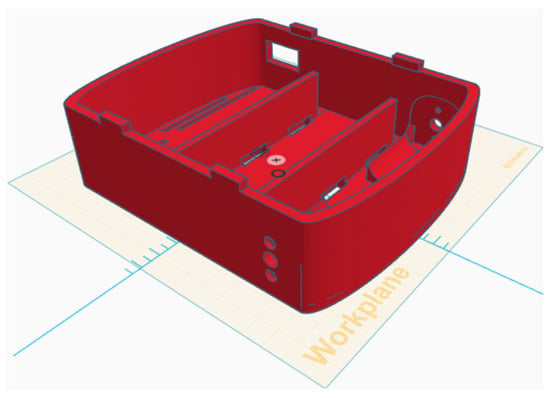

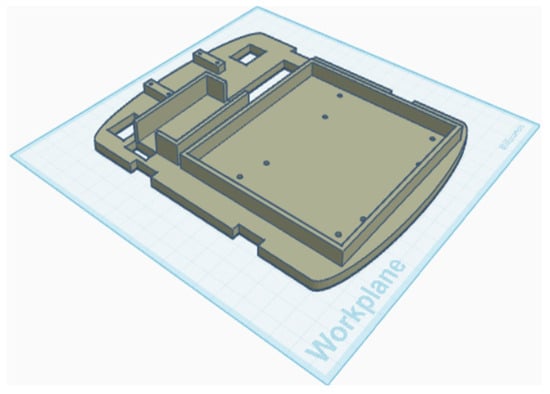

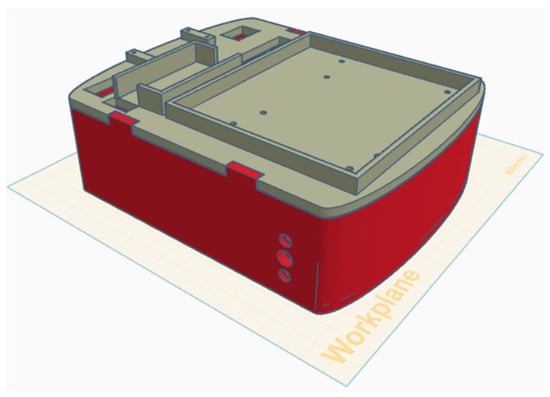

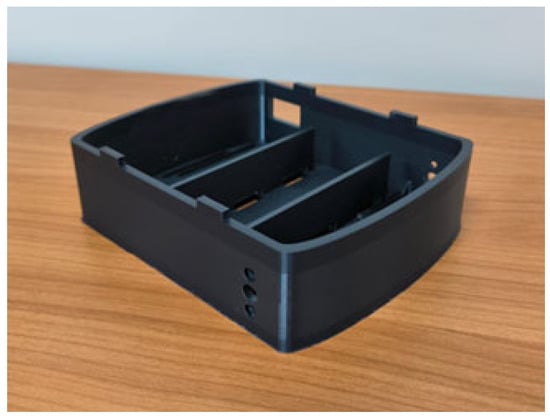

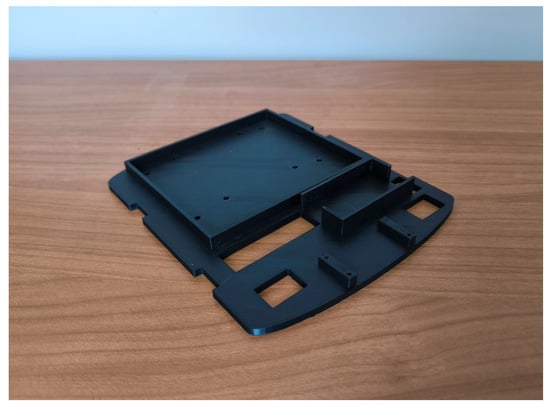

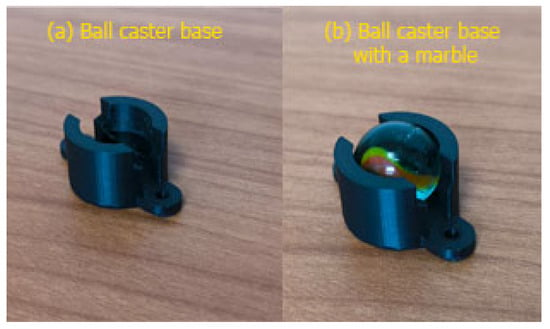

The robot’s chassis was designed in Tinkercad, a free, user-friendly online 3D design tool. The chassis consists of two parts: the base and the top cover. The chassis base contains motors, electronics, and batteries. The top cover supports the Jetson Nano board. Figure 1 shows the chassis view, Figure 2 displays the top cover, and Figure 3 shows the complete assembly. Custom shaft couplings were designed to attach the wheels to the motors (Figure 4). To support the chassis, a ball caster was designed using a glass marble and a 3D-printed mounting (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Robot chassis base.

Figure 2.

Robot chassis cover.

Figure 3.

Complete chassis.

Figure 4.

Wheel coupling.

Figure 5.

Ball caster mounting.

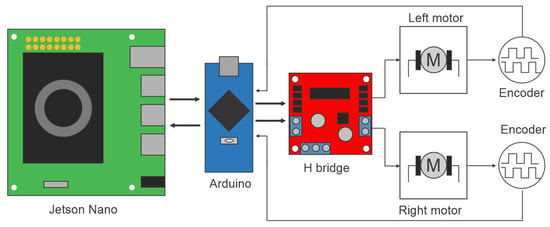

2.3. Hardware Integration

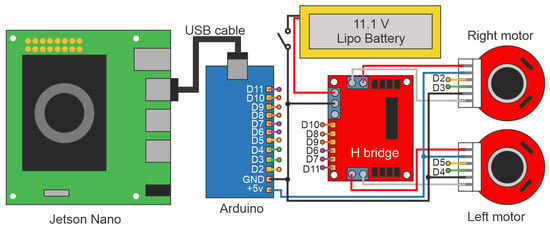

Figure 6 illustrates the overall hardware interaction diagram. The Jetson Nano board acts as the main control unit and communicates with the Arduino to generate control signals for the H-Bridge. The H-Bridge provides the necessary voltage to drive the motors, which are connected to encoders. These encoders generate pulses that the Arduino reads to close the feedback loop.

Figure 6.

General hardware diagram of the prototype.

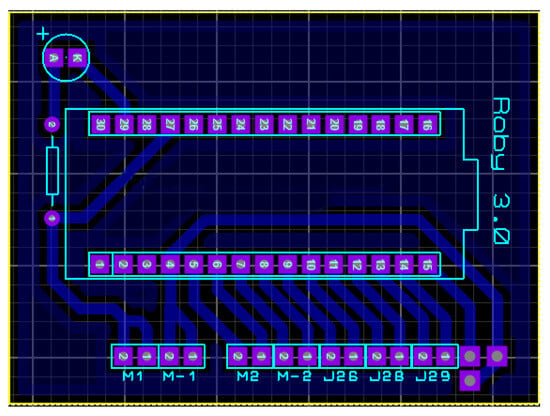

To facilitate the connections between the Arduino Nano and the other electronic components, a custom printed circuit board (PCB) was developed. Figure 7 shows the design of this board.

Figure 7.

Printed circuit board (PCB) design.

2.4. Software Design

The robot’s logic is implemented on the Jetson Nano development board. Although the Jetson Nano supports multiple programming languages, Python was selected because of its rich ecosystem of libraries, ease of use, and open-source nature. The Jetson Nano features a quad-core ARM Cortex-A57 processor, a 128-core Maxwell GPU, 4 GB of LPDDR4 RAM, and runs a customized Linux-based Ubuntu operating system with full support for AI libraries.

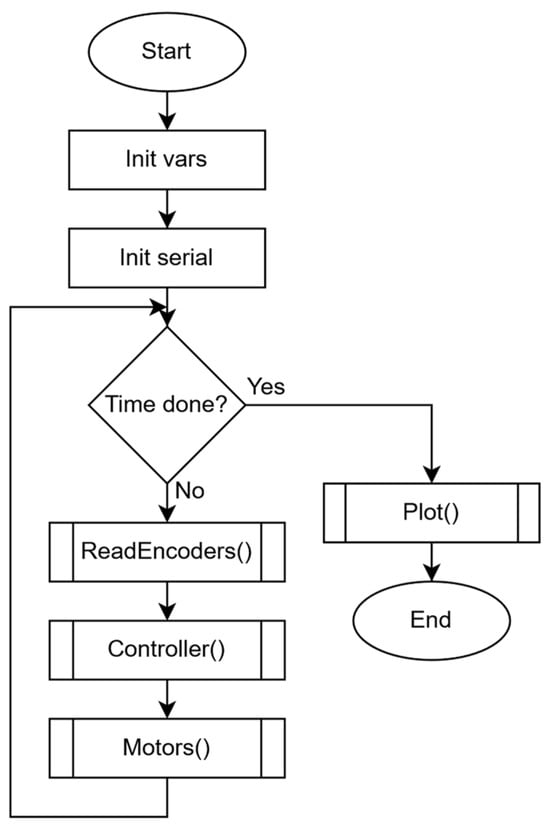

Figure 8 presents the main control program flowchart for the Jetson Nano. First, all initializations are performed. After checking if the total experiment time is reached, three functions are executed in the following order: ‘ReadEncoders’, ‘Controller’, and ‘Motors’. Continuously, total experiment time is rechecked and, if reached, the ‘Plot’ function is executed before the end of the program. As its name states, ‘ReadEncoders’ function reads the robot wheels’ angular velocities provided by the Arduino. The ‘Controller’ function calculates the automatic control law that guarantees trajectory-tracking tasks based on the previously read angular velocities. The ‘Motors’ function codifies the results of the ‘Controller’ function to send variables to Arduino in order to generate the corresponding PWM signals for H-Bridge driving.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of the main program for the Jetson Nano board.

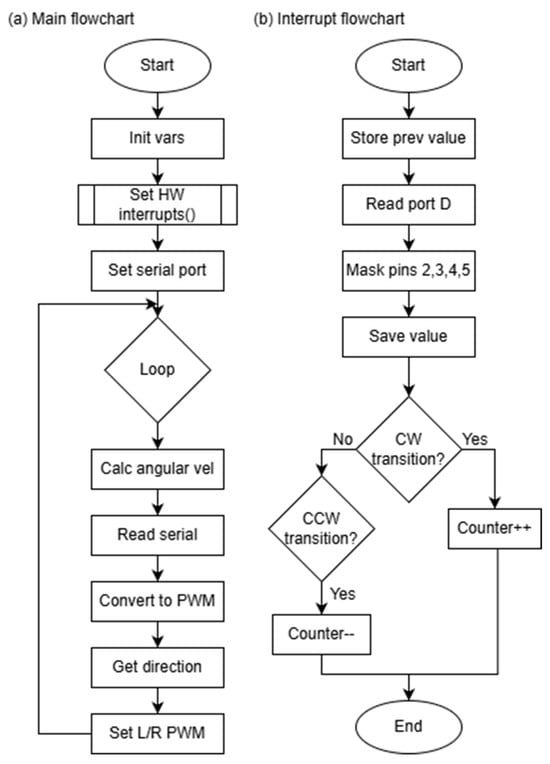

The Arduino Nano main flowchart is shown in Figure 9a. First, general initialization, including variable setup, interrupt setup, and serial communication setup, is performed. The main loop is executed indefinitely and consists of calculating the wheels’ angular velocities, reading the PWM serial data sent by the Jetson Nano, decoding, and generating PWM signals. The Jetson Nano sends string data in the format: “D,value,I,value” where D and I stand for the right and left, respectively. Once a valid string is read, the decoding task consists of extracting right and left PWM data. The sign of each value determines the rotation direction. Arduino’s dedicated hardware is used for PWM generation.

Figure 9.

(a) Main flowchart; (b) Interrupt flowchart.

To calculate the wheels’ angular velocities, an interrupt routine is required. The Encoder interrupt flowchart is shown in Figure 9b. The interrupt routine is triggered when a change is detected in Arduino’s PortD. The routine is as follows: (1) The PortD register is read. (2) A digital mask is applied to isolate pins D2–D5. D2 and D3 correspond to the right motor encoder, while D4 and D5 correspond to the left one. (3) Based on the signal transitions, the direction is determined. If a clockwise transition is detected, the encoder counter is incremented; otherwise, it is decremented.

2.5. Control Law

In automatic control, robots can be designed to perform various tasks; one such task is trajectory tracking. This task consists of guiding the robot along a predefined trajectory at a specified velocity. The reference trajectory is defined as a time-dependent function. Thus, at each time instant, the desired position and orientation are specified.

The control law used in this work is described in [37]. This control law is designed specifically for differential-drive mobile robots, such as the one proposed here. It was selected due to its low computational complexity and its robustness to moderate uncertainties in the robot’s kinematic parameters. These characteristics make it well suited for implementation on embedded systems. Additionally, this control law ensures the convergence of the robot’s position and orientation errors while relying only on simple algebraic operations and without requiring high-resolution measurements.

According to [37], the control law for the trajectory-tracking task is defined as:

where

Let be the robot’s position and the orientation angle, are the controller gains, while and denote the desired linear and angular velocities, respectively.

Regarding the values of the gains and , an experimental procedure was carried out based on the stability conditions established in [37]. First, it was verified that the gains satisfied the required positivity conditions, which are necessary to ensure system stability and adequate damping of errors. Then, a systematic exploration of gain values was performed directly on the robot, evaluating the effect of each gain set in terms of overshoot, reaction time, and smoothness of motion. Based on these criteria, the selected gains were , , and , as this set provided the best balance between stability and trajectory-tracking accuracy.

It is important to note that this control law can be replaced by any other, which is highly desirable for both educational and research purposes.

3. Build Instructions

The construction of the prototype is divided into the following sections: chassis, hardware, and software, which are described in detail below.

3.1. Software

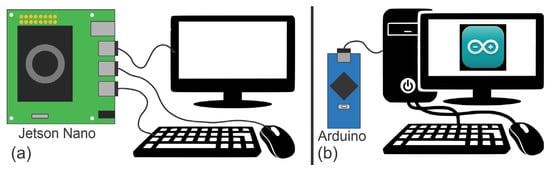

For the steps described in this section, the Jetson Nano board must be disconnected from the chassis and the Arduino Nano. The Jetson Nano should be connected to the necessary peripherals, including a monitor, keyboard, and mouse, as well as to a power supply (see Figure 10a). The Arduino Nano must be connected to a PC with the Arduino IDE installed (see Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

(a) Connection diagram of the Jetson Nano board to peripherals; (b) Connection diagram of the Arduino Nano board to a PC.

To enable the robot’s functionality, both the Jetson Nano and the Arduino Nano must be programmed. The configuration and programming steps for the Jetson Nano are presented first, followed by those for the Arduino Nano.

Jetson Nano: The following instructions assume that the initial setup of the Jetson Nano has already been completed. For a full guide on the initial configuration, please refer to the official Nvidia documentation [38].

To run the software developed in this work, several Python libraries must be installed. It is strongly recommended to create a virtual environment. The required libraries are:

- Numpy 1.13.3

- Matplotlib 2.1.1

- Scipy 0.19.1

- Multiprocessing

Once the libraries are installed, the Supplementary Materials containing the robot’s code can be cloned. It is recommended to create a dedicated folder for this purpose.

Arduino Nano: The code for the Arduino Nano can also be found in the Supplementary Materials. After downloading the source code, it can be uploaded to the Arduino Nano using the Arduino IDE.

3.2. Chasis

The chassis, top cover, caster wheel base, and shaft couplings are fabricated using a 3D printer. The following specifications were used for 3D printing:

- Filament type: PLA

- Material used for chassis: 242 g

- Material used for top cover: 110 g

- Infill density: 30%

- Support type: Tree

- Bed adhesion: None

Figure 11 shows the printed chassis, and Figure 12 shows the top cover. Figure 13 displays the shaft couplings, and Figure 14 shows the caster wheel. For the caster wheel, a glass marble must be placed inside the printed base (see Figure 14b), and then the entire caster wheel should be press-fitted into the underside of the chassis (see Figure 15).

Figure 11.

3D-printed chassis.

Figure 12.

3D-printed top cover.

Figure 13.

Shaft couplings.

Figure 14.

(a) Ball caster base, and (b) Ball caster base with a glass marble.

Figure 15.

Chassis with the ball caster installed.

3.3. Hardware

Once the chassis and top cover are ready, the remaining components can be installed. The following steps should be followed for the chassis:

- Mount the motors to the chassis using two M3 screws for each motor.

- Install the H-Bridge and secure it with nylon standoffs and M3 screws.

- Insert the Arduino Nano into the PCB (the PCB should be fabricated according to the schematic shown in Figure 7).

- Attach the PCB to the chassis using nylon standoffs and M3 screws.

- Install both batteries.

Next, the electronic components must be connected as shown in Figure 16. The batteries should be connected last and only with the power switch in the OFF position. Connections for the encoders and motors should be verified against the component datasheets, as they may vary depending on the manufacturer.

Figure 16.

Electrical wiring diagram.

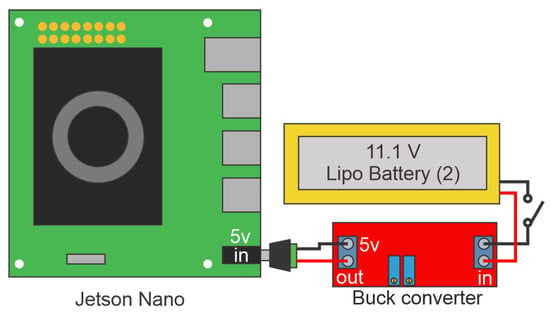

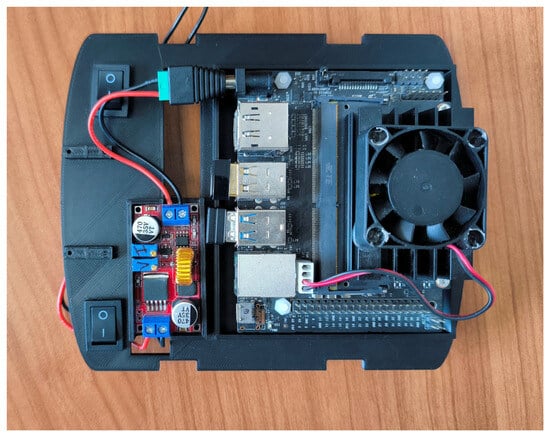

The steps to install the components onto the chassis cover are as follows:

- Figure 17 shows the electrical connections for powering the Jetson Nano.

Figure 17. Jetson Nano power wiring diagram.

Figure 17. Jetson Nano power wiring diagram. - Mount the Jetson Nano to the top cover using nylon standoffs and M3 screws.

- Fabricate a custom cable using a male XT60 connector and a switch with 20 AWG (American Wire Gauge) wire. This cable connects one battery to the voltage regulator (see Figure 17).

- Fabricate a barrel connector cable using 20 AWG wire. This cable connects the voltage regulator to the Jetson Nano (see Figure 17).

- Fabricate another custom cable using a male XT60 connector and a switch with 20 AWG wire. This cable connects one battery to the H-Bridge (see Figure 16).

- Place the fabricated cables and switches on the chassis cover.

- Install the voltage regulator and connect the fabricated cables.

- Connect the Arduino Nano to the Jetson Nano using a USB A to USB C cable.

Figure 18 shows the top cover with all components installed.

Figure 18.

Top cover with mounted components.

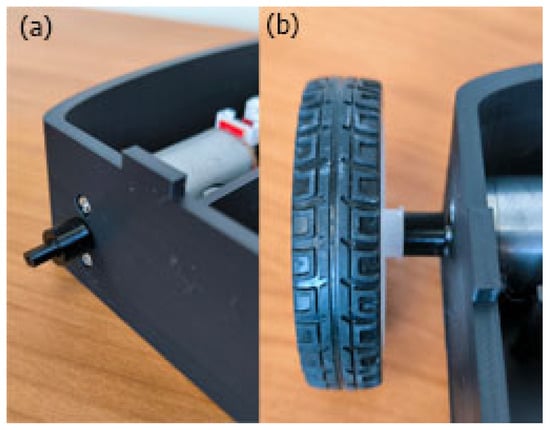

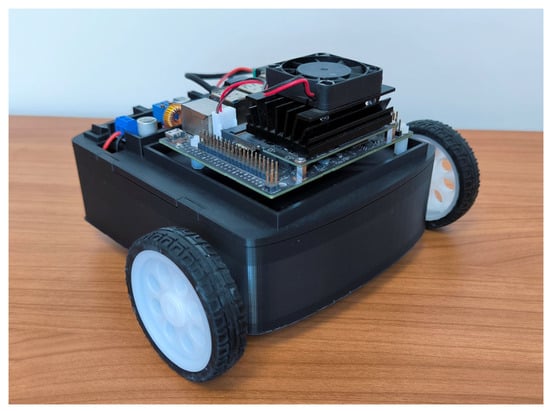

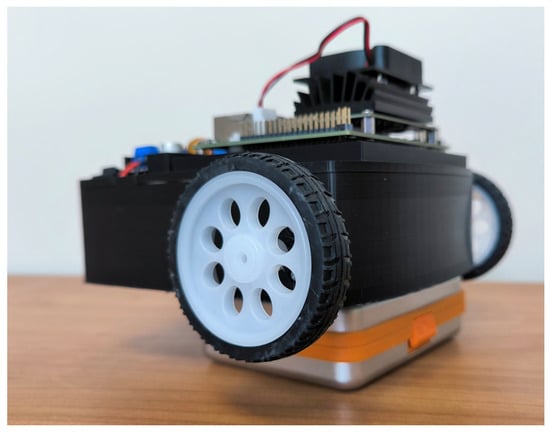

Finally, the shaft couplings are mounted onto the motor shafts (see Figure 19a), followed by the wheels (see Figure 19b). Figure 20 shows the fully assembled prototype, which has been internally named MiniRoby. If different wheels are used, the shaft couplings may need to be modified to fit the new wheel dimensions—this is one of the advantages of using 3D printing.

Figure 19.

(a) Shaft coupling mounted on the motor shaft; (b) Wheel installed on the shaft coupling.

Figure 20.

Differential wheeled mobile robot prototype (MiniRoby).

4. Operating Instructions

4.1. Functionality Verification

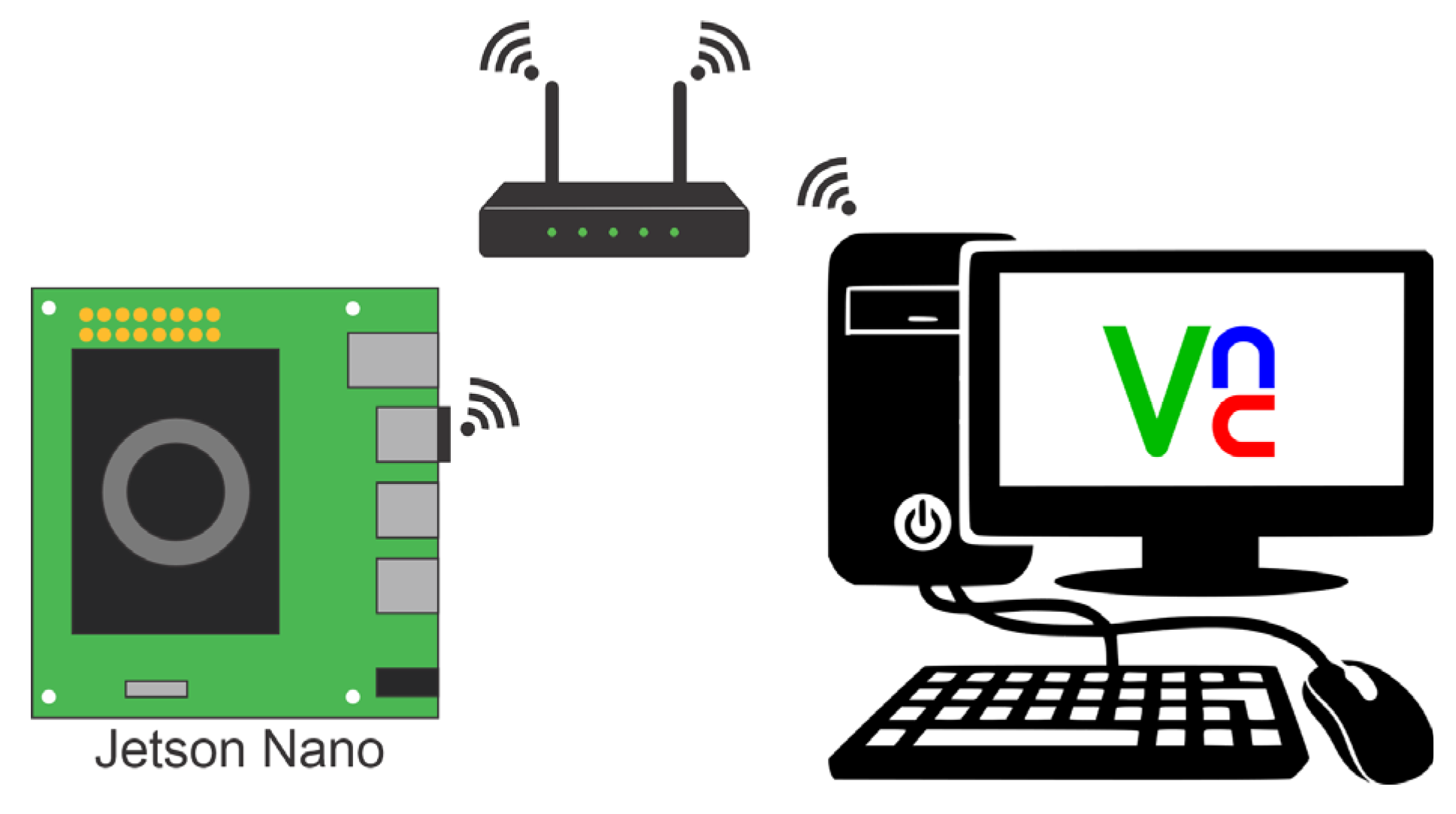

To perform the following verification steps, the robot must be placed on a platform such that the wheels do not touch the ground (see Figure 21). Additionally, a VNC connection must be configured in advance (although tools like PuTTY can be used, VNC is preferred for viewing the plots generated by the program). A PC is also required to establish the VNC connection. Figure 22 shows a general diagram of the components and their connections for VNC setup (several tutorials are available online for configuring VNC on Ubuntu).

Figure 21.

Robot placed on a support base to prevent wheel contact with the surface.

Figure 22.

VNC connection diagram.

Before using the prototype, it is essential to ensure that all components are functioning correctly. The following elements must be verified:

- The left and right motors are connected to the correct sides and rotate in the correct direction.

- The Arduino Nano properly reads the encoder signals.

- The Jetson Nano successfully communicates with the Arduino Nano.

To facilitate this process, a Python script has been developed for testing. To run the script, open the terminal and navigate to the “Test” folder, where the test.py script is located (this folder was downloaded in Section 3.1). Execute the following command:

sudo python3 test.py

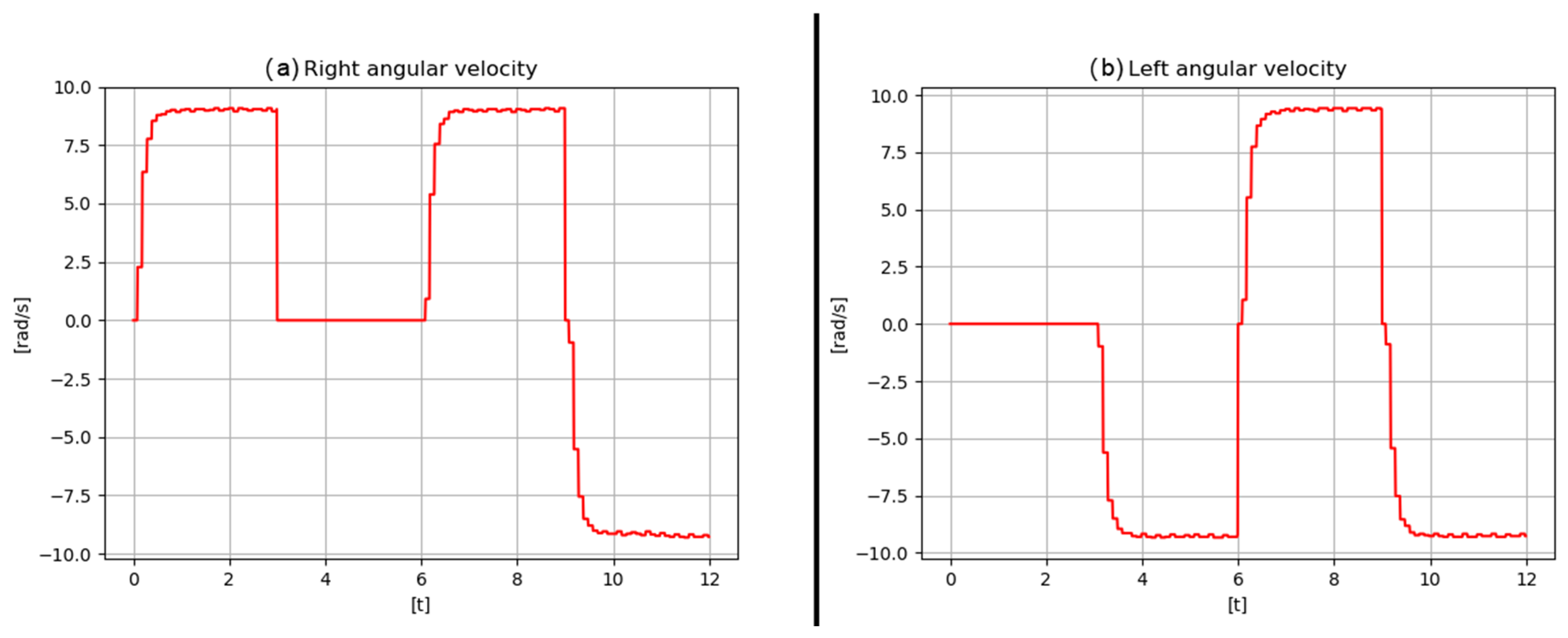

This script will sequentially perform the following actions:

- Rotate the right wheel clockwise for 3 s while the left wheel remains stationary.

- Rotate the left wheel counterclockwise for 3 s while the right wheel remains stationary.

- Rotate both wheels clockwise for 3 s.

- Rotate both wheels counterclockwise for 3 s.

- Plot the angular velocity data for both wheels.

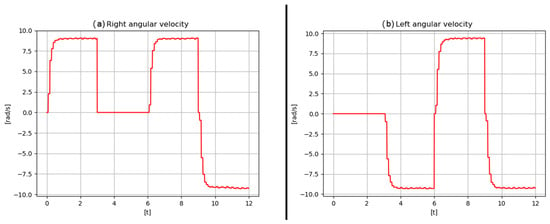

If everything is connected and functioning correctly, results similar to those in Figure 23 should be observed.

Figure 23.

Output results of the test.py script.

Potential errors and troubleshooting:

- Serial connection failure: This occurs when communication between the Arduino and Jetson Nano is not correctly established. Check the serial port name and/or the USB cable used.

- Wheel rotates in the wrong direction: If a wheel rotates in the opposite direction to what is expected, reverse the motor wire connections on the H-Bridge.

- One or both motors do not rotate: Check the wiring from the motor to the H-Bridge. If both motors fail to rotate, ensure that the motor switch is set to the ON position.

4.2. Execution of Experiments

Once all connections have been verified and the robot is operating correctly, experiments can be conducted. It is important to have a workspace free of obstacles, as this version of the prototype does not include obstacle detection sensors.

The following steps must be followed to execute an experiment:

- Place the robot in the workspace. The location where the robot is placed will be considered its initial position (0, 0).

- Ensure the switch associated with the motors is in the OFF position.

- Turn ON the switch connected to the Jetson Nano.

- Establish a VNC connection from the PC.

- Open the terminal and navigate to the experimento directory.

- Turn ON the switch associated with the motors.

- Run the following command:

sudo python3 principal.py

At this point, the robot will begin to move and execute the trajectory tracking task. The desired trajectory must be programmed in advance in the trajectory.py script.

- After completing the experiment, the robot will stop and the relevant variable plots will be displayed. These plots can be customized based on the problem under study.

- Turn OFF the switch associated with the motors.

These steps must be repeated each time a new experiment is performed. After each experiment, the plotted variable values are stored in plain text files, which can later be used in software such as MATLAB if needed.

5. Validation

To validate the functionality of the developed prototype, a series of experimental tests were conducted. The experiments consisted of tracking predefined trajectories, namely: linear, circular, sinusoidal, and complex trajectories. All tests were performed in an indoor obstacle-free environment.

First, the correct motion of the developed prototype is validated. The movements that a differential-drive robot can perform can be classified into two types: forward and backward motion, and turning (left or right). By combining these two basic movements, the robot can execute more complex maneuvers. To validate these basic movements, a dedicated test is conducted for each one. After validating the basic motions, the next step is to verify that the robot can perform the trajectory-tracking task. These tests are described in the following sections.

5.1. Robot Specifications

To conduct the experiments, it is first necessary to know the physical parameters of the robot, as these parameters determine the operating limits and directly influence the robot’s performance. These parameters are presented in Table 3. Obtaining them does not require complex experimentation, as they correspond to characteristics directly associated with the system’s design. These specifications are essential, as they allow for a proper understanding of the experimental results presented in the following sections.

Table 3.

Robot parameters.

5.2. Forward Motion Test

This test is used to verify that the robot can move forward and backward, as well as to compare the physically measured distance traveled with the distance computed using the encoder sensors.

For this test, the robot is programmed to move 1 m in a straight line at a constant velocity. A starting mark is placed on the floor where the robot is positioned, and a second mark is placed at the point where the robot stops. The distance between these two marks is then measured. Using this information, the error between the robot’s computed distance and the actual distance traveled is calculated using the following formula:

The mean error is also computed:

where is the number of samples. The standard deviation is calculated as follows:

Table 4 presents the measured values for the forward and backward motion tests, both performed with a linear displacement of 1 m at a constant velocity of . Based on these data, the mean error for forward motion is cm, and for backward motion cm. The standard deviation for forward motion is cm, and for backward motion cm.

Table 4.

Error results.

A sample size of 10 measurements was considered, given that the developed prototype is intended for academic and research purposes and is not designed to achieve industrial-grade or high-precision performance.

5.3. Turning Test

This test is carried out to verify the correct turning performance of the robot, both to the left and to the right, and to compare the physically measured turning angle with the angle calculated using the mathematical model.

For this test, a cross mark is drawn on the floor, and the robot is aligned with one of its arms. The robot is then programmed to rotate by a specific angle, either clockwise or counterclockwise, and the resulting angle is measured relative to the initial mark. The angular error is computed using the following expression:

The mean angular error is calculated using:

where is the number of samples. The standard deviation is computed using the following expression:

In Table 5, the measured values for the clockwise and counterclockwise turning tests are presented. In both cases, a constant angular velocity of is used. From these data, the mean error for the clockwise turn is , and for the counterclockwise turn . The standard deviation for the clockwise turn is , and for the counterclockwise turn is .

Table 5.

Turning error results.

5.4. Trajectory Tracking Test

To validate that the robot can perform the trajectory-tracking task, the following trajectories were executed: linear, circular, and sinusoidal. These trajectories were selected because they serve as the basis for more complex paths. Additionally, a complex trajectory that includes variations in both linear and angular velocity was also tested. This experiment also serves to validate that the selected embedded system is capable of executing, in real time, both the robot’s pose estimation and the control law required for trajectory tracking.

The robot was tested on a flat surface measuring 1 m × 1 m (the working area can be larger and does not need to be square; for these tests, only 1 m2 was required). Since the selected control law for trajectory tracking requires both linear and angular reference velocities, these values must be provided as inputs. The parameters used for the linear, circular, and sinusoidal trajectories are listed in Table 6. It is important to note that any method for generating reference trajectories may be employed, which is highly desirable in both educational and research contexts. In this regard, a complex trajectory was implemented using the method proposed in [39], which is based on Bézier polynomials to generate trajectories with smooth variations in linear and angular velocity. According to [39], the desired linear velocity and desired angular velocity are given by:

with defined as:

where and are the initial and final times of the trajectory, respectively. The terms and correspond to the constant linear velocities between which the interpolation is performed over the interval . Similarly, and are the constant angular velocities between which the interpolation is performed over the same interval. The coefficients and correspond to the polynomial parameters, which, according to [40], are given by , , and .

Table 6.

Parameters for the reference trajectories.

Accordingly, the parameters used for the complex trajectory based on Supplementary Materials are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Parameters for the complex trajectory.

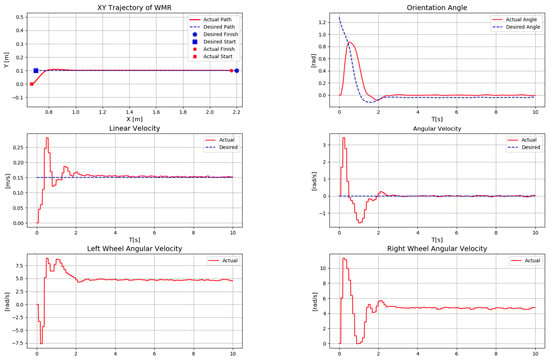

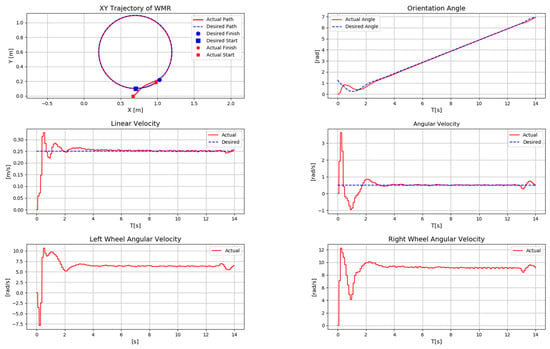

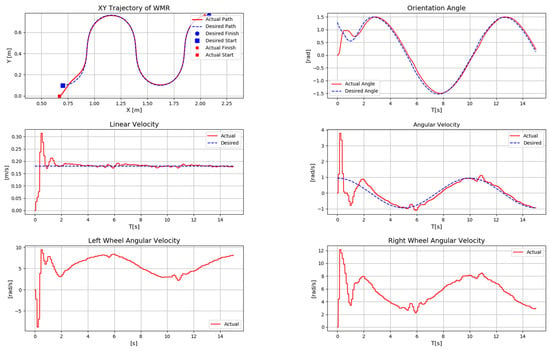

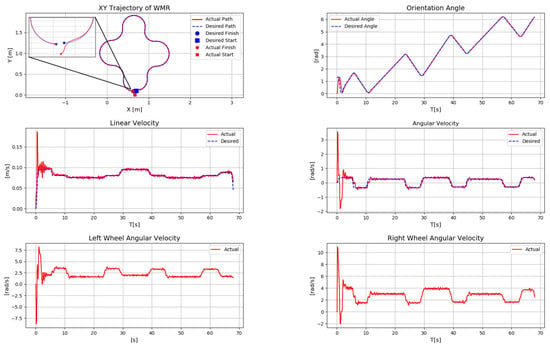

The following figures present the results of the trajectory tracking experiments for the four predefined paths. It is worth noting that the initial robot position (x,y) was arbitrarily set to (0.67,0). This initial offset was intentionally introduced to demonstrate that the robot can converge to and follow the desired trajectory despite an initial position error, thanks to the robustness of the selected control law. Figure 24 shows the result of the linear trajectory, Figure 25 shows the circular trajectory, Figure 26 shows the result for the sinusoidal trajectory, and Figure 27 presents the result for the complex trajectory.

Figure 24.

Results of the linear trajectory experiment.

Figure 25.

Results of the circular trajectory experiment.

Figure 26.

Results of the sinusoidal trajectory experiment.

Figure 27.

Results of the complex trajectory experiment.

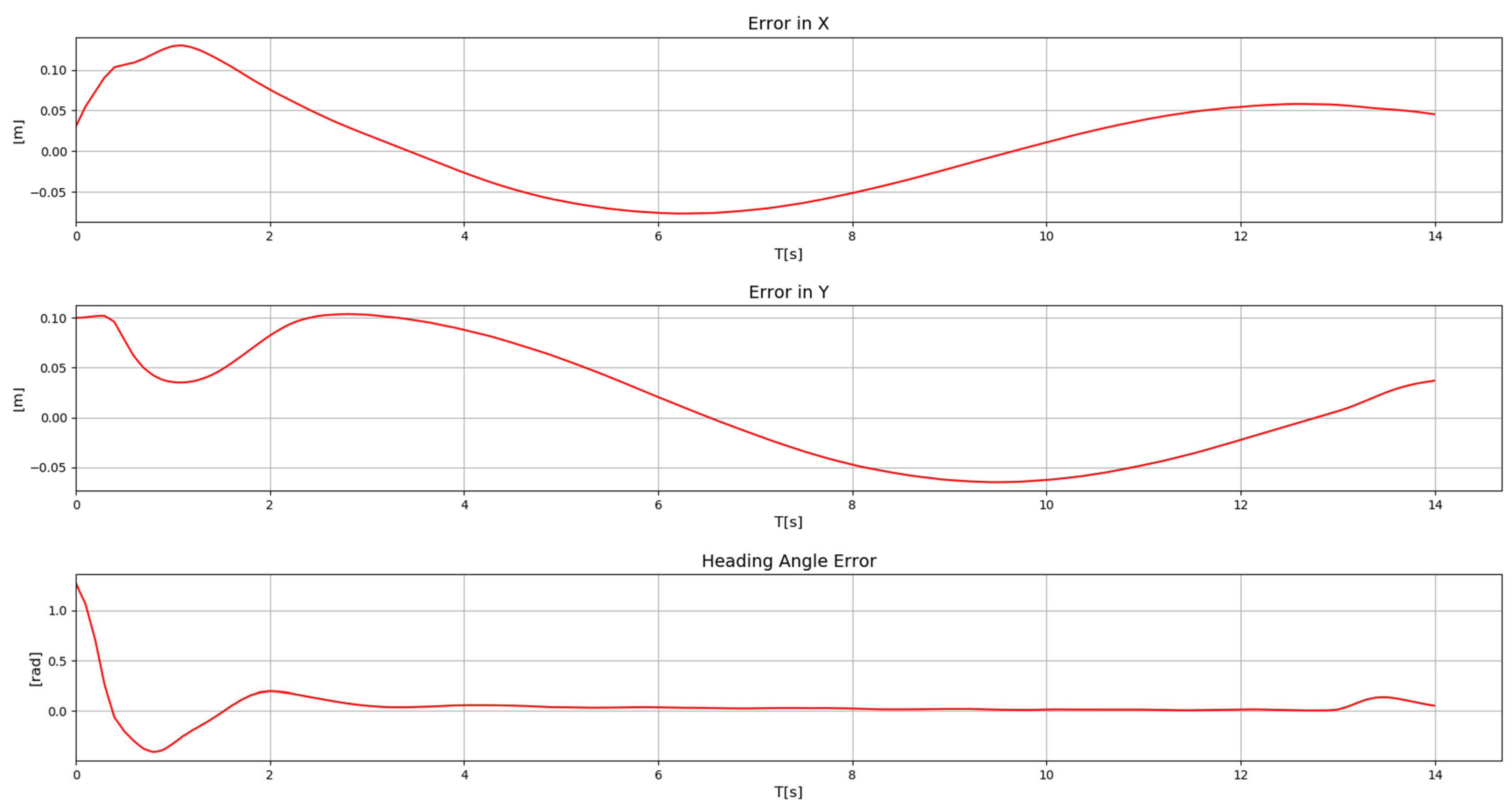

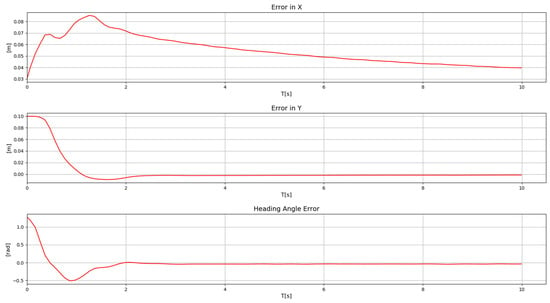

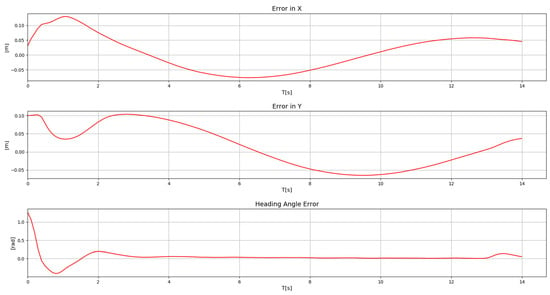

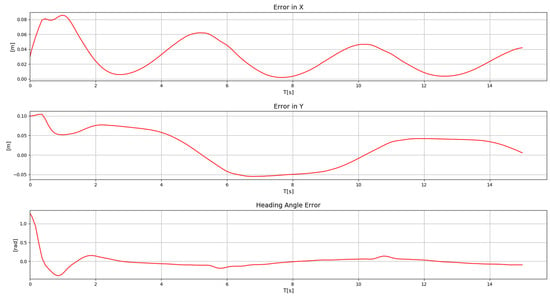

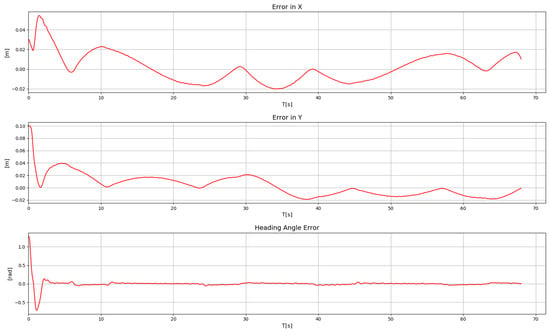

On the other hand, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31 show the tracking and orientation errors for the linear, circular, sinusoidal, and complex trajectories. As can be observed in these plots, the errors are consistent with the values computed in the previous sections.

Figure 28.

Errors for the linear trajectory.

Figure 29.

Errors for the circular trajectory.

Figure 30.

Errors for the sinusoidal trajectory.

Figure 31.

Errors for the complex trajectory.

It is important to note that mean errors and standard deviations are not calculated for this test, as the purpose is solely to validate that the robot is suitable for the trajectory-tracking task. Computing mean errors and standard deviations in this experiment would instead evaluate the performance of the control law employed, which is not the intention of this work.

5.5. Discussion of Results

The experiments carried out allowed for the validation of the proposed platform. The first two tests were conducted to verify the robot’s linear and angular motion. A summary of these results is presented in Table 8, where it can be observed that the experimental data exhibit reasonable linear accuracy, with mean errors of 0.39 cm (forward) and 0.77 cm (backward) for a 1-m displacement. The standard deviation (0.24 cm) indicates good repeatability of the system. For turning movements, the mean error was 4.5° clockwise and 3.7° counterclockwise, values that correspond to good angular accuracy for a differential-drive robot without external sensors. The angular standard deviation confirms that the behavior remains consistent across repetitions.

Table 8.

Mean error and standard deviation for linear and angular motion tests.

The third test focused on validating the ability of the prototype to perform the calculations required for the trajectory-tracking task using the selected embedded system. The results shown in Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31 illustrate the temporal evolution of the robot’s position and orientation error while tracking four different trajectories: (i) linear, (ii) sinusoidal, (iii) circular, and (iv) a complex trajectory. In all cases, the embedded system executed the kinematic model calculations for position estimation and the control law used for trajectory tracking. This confirms that the selected hardware is capable of performing the required processing without perceptible delays.

The observed position and orientation errors remain within the ranges measured during the preliminary experimental tests, which confirms the consistency between the model, the implementation, and the actual performance of the proposed robot prototype. This experimental evidence demonstrates that the robot meets its design objective by performing trajectory tracking with reasonable accuracy, making it suitable for academic and research applications.

5.6. System Limitations

During the experiments, several limitations of the robot were identified, which are described below:

- When estimating the robot’s position and orientation exclusively using the kinematic model, a small error will always be present. This can be improved by incorporating position sensors, although doing so increases the cost of the prototype.

- In practice, no two motors are identical; manufacturing processes can introduce small differences that cause one motor to rotate slightly faster than the other. This may result in forward-motion and heading errors. Such discrepancies can be mitigated by introducing a compensation factor directly into the computed wheel velocities.

- The presented prototype is designed specifically for the trajectory-tracking task. For the robot to perform additional tasks, it is necessary to integrate other sensors. Obstacle-detection sensors or cameras for vision-based tasks can be incorporated. The selected embedded system allows the integration of these and other types of sensors due to its computational capabilities.

- The robot is designed to operate on flat surfaces. On irregular floors, dusty environments, or surfaces with varying friction, wheel slip may increase position and orientation errors. Operating on irregular terrain would require a different type of locomotion.

- The forward-motion and turning tests were performed only at the mean values of the linear and angular velocities. Additional experiments using the minimum and maximum allowable velocities should be conducted to obtain a more complete characterization of the robot’s performance and potentially more precise error estimates.

- For applications beyond academic and research environments, additional mechanisms would be required to ensure safe operation.

6. Conclusions

This work presented the development of a differential wheeled mobile robot prototype for educational and research purposes. The platform integrates a Jetson Nano as the main processing unit, selected for its computational capability and compatibility with Python-based AI libraries. The robot chassis was manufactured using 3D printing, allowing rapid modifications and enabling future functional extensions.

To evaluate the robot’s basic motion capabilities, linear and angular validation tests were conducted. The linear motion tests showed good accuracy, with mean errors of 0.39 cm in the forward direction and 0.77 cm in the backward direction for 1-m displacements, and a standard deviation of 0.24 cm, indicating high repeatability. For turning movements, performance was also consistent, with mean errors of 4.5° clockwise and 3.7° counterclockwise, and standard deviations below 1.1°, values that are acceptable for a robot without position sensors.

A third set of experiments validated the robot’s ability to perform trajectory-tracking tasks, where the embedded system executed in real time both the kinematic model calculations and the selected control law. The robot successfully followed four different trajectories, namely, linear, sinusoidal, circular, and a complex trajectory, showing stable evolution of position and orientation errors over time, even when the complex trajectory included variations in linear and angular velocity.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed robot offers reliable performance in linear motion, turning, and trajectory tracking, while maintaining low cost and high reproducibility. The platform is compatible with other embedded systems, such as the Raspberry Pi or Jetson Orin Nano, requiring only minor adjustments to the main software. Furthermore, its modular design facilitates the integration of additional sensors, such as cameras for vision tasks, ultrasonic sensors for obstacle detection, or infrared sensors for line following, enabling more advanced autonomous navigation capabilities in future educational and research developments.

7. Future Work

Future work will focus on integrating additional sensors into the robot to enable new types of tasks. Among the planned additions are obstacle-detection sensors to support obstacle-avoidance behaviors. A vision system is also intended to be implemented so the robot can perform computer-vision tasks. Another planned capability is line following, using sensors to detect a painted line on the floor. With these sensors, the goal is to equip the robot for autonomous navigation. Finally, didactic materials and classroom evaluations will be developed to strengthen the educational value of the platform.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hardware4010002/s1: text file S0: software requirements; 3Dfiles S1: STL files for 3D printing; jetsonCode S2: Scripts of python source code; arduinoCode S3: Code for Arduino Nano; Video S4: Video of the linear trajectory; Video S5: Video of the circular trajectory; Video S6: Video of the sinusoidal trajectory; Video S7: Video of the complex trajectory.

| Name | Type | Description |

| S0 | text file (.txt) | Software Requirements |

| S1 | 3Dfiles (.rar) | STL files for 3D printing |

| S2 | jetsonCode (.rar) | Scripts of python source code |

| S3 | arduinoCode (.ino) | Code for Arduino Nano |

| S4 | Video (.mp4) | Video of the linear trajectory (Figure 24) |

| S5 | Video (.mp4) | Video of the circular trajectory (Figure 25) |

| S6 | Video (.mp4) | Video of the sinusoidal trajectory (Figure 26) |

| S7 | Video (.mp4) | Video of the complex trajectory (Figure 27) |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.-S.; methodology, J.S.-G.; software, C.M.-S. and J.S.-G.; validation, C.M.-S. and D.L.M.-V.; formal analysis, D.L.M.-V.; investigation, J.S.-G. and D.L.M.-V.; resources, J.S.-G.; data curation, J.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.M.-V.; writing—review and editing, C.M.-S.; supervision, C.M.-S.; project administration, C.M.-S.; funding acquisition, C.M.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) through internal research funding under the project titled Diseño y construcción de un prototipo de robot móvil (2.0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National System of Researchers (SNII) of the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI). During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepL Translator (https://www.deepl.com/es/translator) (accessed on 12 December 2025) for the purposes of auxiliary tasks, specifically for grammatical revision and partial assistance in the translation of the original Spanish text into English, in order to ensure linguistic accuracy and clarity. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Montufar-Chaveznava, R.; Fernandez, Y.L. Crabot: Educational Robot Prototype for Cleaning. In Proceedings of the Portuguese Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Covilha, Portugal, 5–8 December 2005; pp. 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperidis, S.; Doitsidis, L.; Anastasopoulos, C.; Tsourveloudis, N.C. A low cost modular robot vehicle design for research and education. In Proceedings of the Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, Athens, Greece, 27–29 June 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T.F.O.; Falcão, M.A.S.; Lima, A.M.N.; Loureiro, C.F.C.L. MaeRobot: An open source test platform for prototyping robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE Latin American Robotic Symposium, Salvador, Brazil, 29–30 October 2008; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Paina, G.; Guizzo, E.J.; Torres, I.; Gonzalez-Dondo, D.; Paz, C.; Trasobares, F. Open hardware wheeled mobile robot for educational purposes. In Proceedings of the Ninth Argentine Symposium and Conference on Embedded Systems (CASE), Cordoba, Argentina, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, A.; Szybicki, D.; Kurc, K.; Muszyńska, M. Mechatronic designing and prototyping of a mobile wheeled robot driven by a microcontroller. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2020, 58, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piljek, P.; Kotarski, D.; Šćuric, A.; Petanjek, T. Prototyping and Integration of Educational Low-Cost Mobile Robot Platform. Teh. Glas. 2023, 17, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Ohkubo, T.; Watanabe, K.; Tian, K.; Sebi, N.J. Seamless Rapid Prototyping with Docker Container for Mobile Robot Development. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers (SICE), Kumamoto, Japan, 6–9 September 2022; pp. 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Seth, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S. MecQaBot: A Modular Robot Sensing and Wireless Mechatronics Framework for Education and Research. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Sensing Technology (ICST), Sydney, Australia, 9–11 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamvazuthi, I.; Law, J.; Singh, V.; Khan, M.A.; Parasuraman, S.; Balaji, M.; Chandrasekaran, M. Development of an autonomous tennis ball retriever robot as an educational tool. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 76, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, B.S.; Corsiga, C.M.; Baxter, B.W.; Martinez-Garcia, J.; Koury, J.S.; Moon, A.J.S. Design and Prototyping of Smart Mobile Grinding Bots as an Educational Tool. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 41, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.H.; Monteiro, J.M.; Gonçalves, J.; Costa, P. Prototyping and Programming a Multipurpose Educational Mobile Robot—NaSSIE. Robotics in Education. RiE 2018. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Lepuschitz, W., Merdan, M., Koppensteiner, G., Balogh, R., Obdržálek, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 829, pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Pinto, V.H.; Costa, P. A line follower educational mobile robot performance robustness increase using a competition as benchmark. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, W.A.; Da Silva Rezende, J.P.; Pimenta, M.B.; Bacheti, V.P.; Sarcinelli-Filho, M.; Dourado Villa, D.K. Connecting Theory to Practice: Mathematics, Physics, and Mobile Robotics in Our Daily Lives. In Proceedings of the Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR) and Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), Goiania, Brazil, 13–15 November 2024; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, M.; Sing, J.C.; Nadarajan, M.; Wee, C.C. Early childhood educational robotic system (C-Block): A design methodology. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 11206–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.B.; Gomes, P.H.L.; Rodriguez Silva, L.F.; Pastrana, M.A.; Gontijo, M.C.C.; Luiz, M.S.; Muñoz, D.M. Utilizing Mobile Robots to Teach Dengue and Chikungunya Prevention in Brazilian Schools. In Proceedings of the Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR) and Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), Goiania, Brazil, 13–15 November 2024; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanashetty, K.; Balaji, K.P.; Pandian, S.R. Educational outdoor mobile robot for trash pickup. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–16 October 2016; pp. 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwatkit, C.; Prommool, P.; Nobnob, R.; Boonsamuan, S.; Suwan, R. A collaborative STEM project with educational mobile robot on escaping the maze: Prototype design and evaluation. Advances in Web-Based Learning—ICWL 2018. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Hancke, G., Spaniol, M., Osathanunkul, K., Unankard, S., Klamma, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11007, pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachantidis, N.; Dimitriou, A.G.; Pliasa, S.; Dagdilelis, V.; Pnevmatikos, D.; Perlantidis, P.; Papadimitriou, A. Android OS mobile technologies meets robotics for expandable, exchangeable, reconfigurable, educational, STEM-enhancing, socializing robot. Interactive Mobile Communication Technologies and Learning (IMCL 2017). In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Auer, M., Tsiatsos, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 725, pp. 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura Ballestero, E.; Calderón-Arce, C.; Solís-Ortega, R.; Brenes-Torres, J.C.; Arias-Méndez, E. Educational Atta-Bot: A Multiplatform Mobile Application. In Proceedings of the IEEE VII Congreso Internacional en Inteligencia Ambiental, Ingeniería de Software y Salud Electrónica y Móvil (AmITIC), David, Panama, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobyzev, N.P.; Golubev, S.A.; Artamonov, Y.G.; Karimov, A.I.; Goryainov, S.V. Embedded control system for tracked robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE II International Conference on Control in Technical Systems (CTS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 25–27 October 2017; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassanov, A.; Krupenkin, A.; Borgul, A. Control of the mobile robots with ROS in robotics courses. Procedia Eng. 2015, 100, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Costa, P. Differential mobile robot controller study: A low cost experiment based on a small Arduino based prototype. In Proceedings of the 25th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Valletta, Malta, 3–6 July 2017; pp. 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamphroo, M.; Kwankeo, N.; Kaemarungsi, K.; Fukawa, K. Integrating MicroPython-based educational mobile robot with wireless network. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Technology and Electrical Engineering (ICITEE), Phuket, Thailand, 12–13 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Aldás, J.; Junta, C.; Buele, J.; Palacios-Navarro, G. An Assessment of a ROS Class Using an Educational Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the 9th International Engineering, Sciences and Technology Conference (IESTEC), Panama City, Panama, 23–25 October 2024; pp. 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filaretov, V.F.; Pryanichnikov, V.E. Autonomous mobile university robots AMUR: Technology and applications to extreme robotics. Procedia Eng. 2015, 100, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; MahmoudZadeh, S.; Yazdani, A.; Moshayedi, A.J. Feasibility assessment of Kian-I mobile robot for autonomous navigation. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 34, 1199–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Zamaia, J.F.; Flávio de Melo, L. Nonholonomic mobile robot prototype for standalone navigation with embedded system. In Proceedings of the CHILEAN Conference on Electrical, Electronics Engineering, Information and Communication Technologies (CHILECON), Pucon, Chile, 18–20 October 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkáčik, M.; Březina, A.; Jadlovská, S. Design of a prototype for a modular mobile robotic platform. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Law, F.; Thurlbeck, A.; West, C.; Baxter, M.; Inayat, A. Design of a mobile robot prototype for a relay race. In Proceedings of the 31st Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Wuhan, China, 11–13 November 2016; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegarpanah, M.; Asif, M.E.; Butt, J.; Voos, H.; Rastegarpanah, A. Mobile robotics and 3D printing: Addressing challenges in path planning and scalability. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2433588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, G.; Jeswin, Y.; Divith, R.R.; Suhaag, B.R.; Daksh, U.; Kiran, R.K.M. Real Time Object Detection and Tracking Using SSD Mobilenetv2 on Jetbot GPU. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing, VLSI, Electrical Circuits and Robotics (DISCOVER), Mangalore, India, 18–19 October 2024; pp. 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraanje, R.; Koreneef, T.; Le Mair, A.; Jong, S. Python in robotics and mechatronics education. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th France-Japan & 9th Europe-Asia Congress on Mechatronics (MECATRONICS)/17th International Conference on Research and Education in Mechatronics (REM), Compiegne, France, 15–17 June 2016; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetbot. Available online: https://jetbot.org/master/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- JetBot AI Kit, AI Robot Based on Jetson Nano. Available online: https://www.waveshare.com/catalog/product/view/id/3755 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Yahboom Jetbot Mini AI Vision Robot Car ROS Starter Kit w/Jetson Nano 4GB/2GB SUB Board—RobotShop. Available online: https://www.amazon.com.mx/Yahboom-Robotic-programable-Starter-universidad/dp/B09P566831?th=1 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Duckiebot (DB-J)—DIY Autonomous Car Kit—The Duckietown® Project Store. Available online: https://get.duckietown.com/products/duckiebot-db21?variant=41543707099311 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Fukao, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Adachi, N. Adaptive tracking control of a nonholonomic mobile robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2000, 16, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Get Started With Jetson Nano Developer Kit|NVIDIA Developer. Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/embedded/learn/get-started-jetson-nano-devkit#intro (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Márquez-Sánchez, C.; Sanchez, J.R.G.; Cervantes, C.Y.S.; Ortigoza, R.S.; Guzman, V.M.H.; Juarez, J.N.A. Trajectory Generation for Wheeled Mobile Robots Via Bézier Polynomials. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 4482–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, L.; Melchiorri, C. Trajectory Planning for Automatic Machines and Robots; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; p. 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.