Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G–CAN) Conference 2025: Early-Career Investigators’ Abstracts

Abstract

1. Progression of CPPD Burden in a Cohort of Patients with CPPD Disease: Over 1 Year Follow-Up

- Antonella Adinolfi 1, Silvia Sirotti 2,3, Greta Pellegrino 2,3, Alessandro Lucia 4, Daniele Cirillo 4, Rodolfo Fabbri 4, Laura Pezzoni 4, Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini 2,3, Oscar Massimiliano Epis 1 and Georgios Filippou 2,3

- 1

- Rheumatology Division, Multispecialist Medical Department, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milan, Italy

- 2

- IRCCS Galeazzi–Sant’Ambrogio Hospital, Rheumatology Department, Milan, Italy

- 3

- University of Milan, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Milan, Italy

- 4

- University of Milan, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, Milan, Italy.

- *

- Correspondence: antonella.adinolfi986@gmail.com

- Abstract: Background: Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) is a complex disorder. A pathological key could be the relationship between the extent of crystal deposition and the clinical phenotypes. In 2023, the OMERACT Ultrasound (US) Working Group validated a scoring system for assessing the extent of CPPD. This system evaluates bilaterally the triangular fibrocartilage of the wrist, the knee hyaline cartilage and both menisci. Each site is graded on a 4-point scale (0–3), resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 24. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between crystal burden changes, evaluated with the US score, and clinical progression across the CPPD subsets. Methods: From January 2024, consecutive CPPD disease patients diagnosed according to the 2023 ACR/EULAR classification criteria were enrolled. All participants underwent a comprehensive clinical examination to classify them into one of the following phenotypes: acute arthritis, osteoarthritis (OA) with CPPD, or chronic arthritis. Disease activity was evaluated using visual analog scales (VAS) given by both the patient and physician, while medications were systematically recorded. US assessments were performed by two rheumatologists with expertise in CPPD and US, following a pre-specified scanning protocol. For each following visit, the same assessments were repeated. The statistical analysis was performed using R software v4.4.2. Statistical significance was fixed at a p-value < 0.05. Results: A total of 53 patients were enrolled in the study: 69.6% female, with a mean age of 77.9 years (±8.26 SD), 24 affected by acute CPP crystal arthritis, 16 with chronic arthritis and 10 with OA + CPPD. 3 patients were classified as asymptomatic CPPD. 31 patients ended the first year of follow-up. Over 80% started a treatment, mostly represented by colchicine, followed by methotrexate (MTX) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). At baseline, the VAS of the patient was 52.5 (SD ± 29), while the physician’s was 43 (SD ± 28.17). During the follow-up, these improved, respectively, to 37.4 (SD ± 26.3) and 26.3 (SD ± 24.57), both reaching statistical significance.

- -

- Acute CPP crystal arthritis: 12.41 (SD ± 3.98, median 12.5).

- -

- Chronic CPP crystal arthritis: 14.5 (SD ± 4.95, median 15.5).

- -

- OA with CPPD: 13.5 (SD ± 4.06, median 14).

- -

- Acute CPP crystal arthritis: 12.25 (SD ± 5.46, median 12).

- -

- Chronic CPP crystal arthritis: 14 (SD ± 5.3, median 15).

- -

- OA with CPPD: 14.5 (SD ± 3.29, median 14).

2. Detection of Future Gout Flare Using Peripheral Blood Gene Expression with Machine Learning

- Hussain Aljafer 1,*, Guanqi Lu 1, Ted R. Mikuls 2, Angelo Gaffo 3, Tony R Merriman 3, Austin M. Wheeler 2, James O’Dell 2, Jefferey Newcomb 2, Michael Pillinger 4, Robert Terkeltaub 5, Ryan Ferguson 6,7, Mary Brophy 6,8, Tuhina Neogi 7, Jeffrey C Edberg 3, Richard J Reynolds 3,†, Ana I Vazquez 1,†

- 1

- Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

- 2

- University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE and VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Healthcare System, Omaha, NE, USA

- 3

- University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

- 4

- VA New York Harbor Health Care System, New York, NY, USA

- 5

- University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA. USA

- 6

- VA Boston Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, Boston, MA, USA

- 7

- Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

- 8

- School of Medicine, VA Boston Health Care System, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA

- *

- Correspondence: aljaferh@msu.edu

- †

- Authors with equal contribution.

- Abstract: Background: Urate-lowering therapy is an effective treatment for gout if properly dosed and if serum urate levels below 6 mg/dL are achieved and maintained [1]. Nevertheless, people properly treated for gout may still flare, for reasons largely unknown. Most people with gout are unable to identify a trigger for their gout flares; hence, their unpredictable nature represents a significant therapeutic challenge [2]. If gout flares in the future were predictable, prophylactic therapy could be extended in individuals at high risk for future gout flares. Objective: To use machine learning methods and circulating transcriptomic features to predict gout flares. Methods: Our work aims to investigate the feasibility of predicting gout flares based on gene expression counts derived from peripheral blood samples. RNA and clinical data were obtained from a subgroup of the STOP Gout (NCT02579096) clinical trial [3]. The current analysis utilized RNA obtained from 174 participants sampled at week 48. For six months thereafter, flares were observed during the flare monitoring period. The primary outcome was at least one flare. We implemented and evaluated six machine learning models to predict the primary outcome. We evaluated the predictive ability of the models with AUC using 10-fold cross-validation. RNA transcripts selected for prediction (between 700 and 1000 per training set) were differentially expressed between flare and no flare groups (p-value < 0.05; independent T-test). Results: The prediction accuracy of the PyTorch v2.9.0 neural network model (a machine learning algorithm implemented in Python and developed by Meta) was the highest and XGBoost was the lowest compared to other models. Of the 174 subjects, 94 participants flared during the outcome observation period. The neural network predicted 100 flares, of which 65 predictions were correct, resulting in a positive predictive value (PPV) of 65%. XGBoost predicted 101 flares, of which 54 were correct predictions, resulting in a PPV of 53% (Figure 1; Table 1). The neural network achieved a 65.3% AUC across the average of 10 fold cross validations, outperforming other models and classification approaches tested. The PyTorch neural network model resulted in higher AUCs vs. logistic regression (59.8%), naïve Bayes (57.1%), random forest (51.1%), XGBoost (50.2%), and K-nearest neighbor (53.3%). Conclusions: This is the first application of an omics-enabled machine learning predictive tool for future gout disease activity. The results demonstrate that gene expression data contains signals predictive of the onset of gout flares. Recently obtained clinical and demographic data from Stop Gout will allow us to calculate the increase in AUC when adding omics to a base flare prediction model. The findings support the potential utility of transcriptomic biomarkers in developing predictive tools for clinical decision-making.

- FitzGerald, J.D.; Dalbeth, N.; Mikuls, T.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Guyatt, G.; Abeles, A.M.; Gelber, A.C.; Harrold, L.R.; Khanna, D.; King, C.; et al. American college of rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 744–760.

- Abhishek, A.; Valdes, A.M.; Jenkins, W.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M. Triggers of acute attacks of gout, does age of gout onset matter? A primary care based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186096.

- O’Dell, J.R.; Brophy, M.T.; Pillinger, M.H.; Neogi, T.; Palevsky, P.M.; Wu, H.; Davis-Karim, A.; Newcomb, J.A.; Ferguson, R.; Pittman, D.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Allopurinol and Febuxostat in Gout Management. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, evidoa2100028. https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2100028.

3. Unraveling a New Inflammatory Pathway: CSF1 and Its Regulatory ncRNAs in Gout

- Nils Asmann 1, Nicholas A. Sumpter 1, Brenda Kischkel 1, Ezio T. Fok 2, Riku Takei 3, Megan P. Leask 4, Jeffrey Edberg 3, Richard J. Reynolds 3, Musa M. Mhlanga 5,6, Tony R. Merriman 3,7 and Leo A. B. Joosten 1,8

- 1

- Radboud University Medical Center, Department of Internal Medicine, 6500HB, Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

- 2

- Lemba Therapeutics, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

- 3

- Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA

- 4

- Department of Physiology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- 5

- Department of Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

- 6

- Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Science, Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

- 7

- Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- 8

- Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Medical Genetics, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- Abstract: Background: Gout is characterized by inflammatory flares caused by intra-articular monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposition and innate immune activation. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS), including >120,000 gout patients, identified >350 genetic loci. Some of these variants are associated with gout but not hyperuricemia, pointing to genes involved in the immune response. We focus here on non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) controlling the transcription of putative gout flare-related genes. A previously unidentified expression QTL identified the CSF1−CSF1R axis. The role of colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) in immunity remains controversial, with both pro- and anti-inflammatory functions reported [1–3]. These dual properties may contribute to gout flare progression, making its regulatory ncRNAs (immune-priming lncRNA (IPL)) and sense and antisense enhancer RNAs (eRNA) key modulators (Figure 2). Our goal is to target these ncRNAs to modulate inflammation. Methods: We first validated a robust detection assay of IPL, eRNA, and CSF1 in PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells using digital droplet PCR (ddPCR). We then transitioned to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 10 healthy, European white males (>50 years old). These cells were stimulated with MSU crystals with and without LPS. As the negatively charged crystal surfaces interfered with commercial RNA isolation kits—causing contamination and selection bias—we established a protocol using classical Chloroform-RNA extraction followed by a bead-based clean-up. Analyses include ELISAs, total RNA sequencing, Olink proteomics, and ddPCR on subcellular fractions, with nuclear RNA subject to further division. Results: Using THP-1 cells, both the IPL and eRNA showed an initial transcription peak at 4 h, supporting a regulatory function, while their targets, CSF1 and CSF1R, became continuously upregulated over 96 h. In PBMCs, we found that 4 h MSU crystal stimulation alone upregulated CSF-1 along with its associated sense and antisense eRNA. Interestingly, this upregulation was abrogated by co-stimulation with LPS. The increase in CSF-1 was still present at 8 h, but the signal for its potential eRNAs vanished, suggesting a transient regulatory action. The IPL was consistently below the detection limit (<0.5 copies/µL) in all primary cell settings. Olink proteomics data confirmed the MSU crystal-driven regulation of CSF1 (Figure 3) and revealed novel protein hits for both MSU crystal and MSU crystal + LPS stimulation. Conclusion: This study explores CSF1 and its low-abundant ncRNAs in gout, highlighting key molecular considerations from RNA isolation to cell type. Our ongoing work with PBMCs, using RNA-seq and Olink proteomics, aims to elucidate drivers of gout. Initial Olink analysis implicates novel proteins, including CSF1, in the MSU crystal response, supporting further investigation into the CSF1 axis and its role in the inflammatory MSU crystal response and finally in gouty arthritis.

- Stanley, E.R.; Chitu, V. CSF-1 Receptor Signaling in Myeloid Cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a021857.

- Chitu, V.; Stanley, E.R. Colony-stimulating factor-1 in immunity and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006, 18, 39–48.

- Hume, D.A.; MacDonald, K.P.A. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood 2012, 119, 1810–1820.

4. Serum Metabolomics Reveals Dyslipidaemia in Gout and Hyperuricemia: Elucidating Inflammatory Links Through Integrative Multi-Omics

- Georgiana Cabău 1,*, Marko Barovic 2, Triantafyllos Chavakis 2, Tania O. Crișan 1,† and Leo Joosten 1,3,†

- 1

- Department of Medical Genetics, “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- 2

- Institute for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, University Hospital, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

- 3

- Department of Internal Medicine, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

- *

- Correspondence: georgiana.cabau@gmail.com

- †

- T.O.C and L.J. share last authorship.

- Abstract: Background & Objectives: Gout and asymptomatic hyperuricemia (AH) are characterized by both metabolic dysregulation and systemic inflammation, yet the interplay between lipid alterations and inflammatory responses remains insufficiently understood. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics enables the characterization of metabolite and lipid species, providing insights into metabolic disturbances associated with these conditions. While dyslipidaemia, including elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), has been previously reported in gout and AH, its relationship with inflammatory pathways remains unclear. This study aims to: (i) identify metabolomic and lipidomic alterations distinguishing gout and AH from normouricemic controls; (ii) investigate correlations between these metabolic shifts and in vivo inflammatory responses; and (iii) experimentally validate the inflammatory potential of VLDL through in vitro human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) stimulations, testing the hypothesis that VLDL, potentially modulated by urate exposure, might drive inflammation. Methods: Serum samples from patients with gout, AH, and normouricemic controls were analyzed using an NMR-targeted metabolomics approach to profile lipid and metabolic alterations. Principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were employed to identify key metabolites differentiating groups, while correlation analyses with inflammatory serum proteins (in vivo) provided insights into lipid-associated immune activation. To further explore these findings, ongoing in vitro PBMC stimulations with Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and VLDL are being conducted, assessing cytokine production (IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-6) in relation to observed lipidomic changes, thereby providing mechanistic insights into its contribution to systemic inflammation in gout and AH. Results: Preliminary analyses identified distinct dyslipidemic profiles in gout and AH, prominently featuring elevated VLDL and associated lipid species. Significant correlations were observed between these lipid profiles and serum inflammatory proteomic markers, suggesting a potential metabolic-inflammatory association. Ongoing PBMC stimulations aim to clarify whether VLDL directly contributes to inflammatory cytokine responses, potentially elucidating mechanisms linking lipid alterations to inflammation. Conclusions & Significance: This integrative multi-omics approach reveals significant dyslipidaemia associated with gout and AH, potentially linking metabolic disturbances with systemic inflammation. By combining in vivo metabolic and inflammatory profiling with targeted in vitro validation, this study seeks to clarify the role of VLDL as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Findings may offer new therapeutic targets to modulate metabolic and inflammatory pathways in hyperuricemia-associated conditions, as a strategy to improve patient outcomes.

5. Effect of Smartphone Application-Led Patient Management Model on Adult Gout Patients in China

- Zhiwei Cao * and Haibing Chen

- School of Medicine, Tongji University, 301 Yan Chang Zhong Road. Jing’an District, Shanghai 200072, China; hbchen@tongji.edu.cn

- Abstract: Background and Objectives: Current gout management in China faces challenges including low serum urate (SU) target achievement rates and suboptimal long-term disease control. While nurse-led management models can improve SU target attainment and reduce gout flares, they require high manpower costs. Smartphone applications (apps) for patient self-management have shown potential in lowering SU levels but lack comprehensive evaluation of gout and other metabolic indicators. This study evaluates a smartphone app-led patient management model for gout patients, assessing its impact on SU target achievement, gout flare reduction, and quality of life improvement. Study Design and Methods: This 6-month, single-center, open-label, superiority, parallel-group randomized controlled trial screened and recruited hyperuricemia and gout patients from Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital between November 2023 and July 2024. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to either the app-management group (using the “1CARE Health” digital platform with continuous SU monitoring, tiered education, online communication, follow-up reminders, and cloud data sharing) or the conventional management group (quarterly outpatient follow-ups). The primary outcome was SU target achievement rate (<360 μmol/L). Secondary outcomes included SU levels, gout flare frequency, lipid/glucose metabolic parameters, and quality-of-life scores (SF-36 and Gout Impact Scale). Results: Among 280 enrolled male patients, 247 completed 6-month follow-up. The app-management group showed significantly higher SU target achievement (52.14% vs. 32.86%; RR 1.59, 95% CI (1.19–2.11); p = 0.002) and lower mean SU levels (349.23 ± 57.65 vs. 394.04 ± 62.96 μmol/L, p < 0.001) versus controls. Consistent improvements were observed in SU < 300 μmol/L rates, gout flare frequency, total cholesterol, LDL-C, fasting glucose, and HbA1c. The app group demonstrated better SF-36 physical functioning (76.06 ± 13.83 vs. 72.32 ± 15.52, p = 0.001) and Gout Impact Scores (30.18 ± 12.70 vs. 35.31 ± 16.85, p = 0.004). Improved adherence was evidenced by higher water intake and regular SU monitoring rates in the app group. Other secondary outcomes showed no significant differences. Conclusions: The smartphone app-led management model effectively improves health behaviors and adherence, leading to enhanced SU target achievement, reduced SU levels, decreased gout flares, better metabolic control, and improved quality of life.

6. Validation of an Allopurinol Dose Prediction Tool to Achieve Goal Serum Urate Among Patients with Gout in a Protocolized Dose Escalation Trial

- Brian W Coburn 1,2, Daniel Wright 3, Jeff A Newcomb 4,5, Mary T Brophy 6,7, Anne Davis-Karim 8, Ryan Ferguson 6, Michael H Pillinger 9,10, Tuhina Neogi 11, Paul Palevsky 12,13, Bryant England 4,5, James O’Dell 4,5, Lisa Stamp 14, Ted R Mikuls 4,5 and Joshua Baker 1,2

- 1

- University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

- 2

- Philadelphia VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

- 3

- University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- 4

- University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

- 5

- VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE, USA

- 6

- Boston Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, Boston, USA

- 7

- VA Boston Health Care System, Boston, MA, USA

- 8

- Wentworth Institute of Technology, Boston, MA, USA

- 9

- VA New York Harbor Health Care System, New York City, NY, USA

- 10

- NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, NY, USA

- 11

- Boston University, Boston, MA, USA

- 12

- VA Pittsburgh Health Care System, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

- 13

- University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

- 14

- University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand

- *

- Correspondence: brian.coburn@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

- Abstract: Background/Purpose: Despite evidence-based recommendations, allopurinol dose escalation to goal serum urate (SU) is frequently suboptimal. The EasyAllo tool was developed to facilitate pre-planned allopurinol dose escalation by predicting the allopurinol dose needed to achieve SU < 6 mg/dL > 80% of the time and promote easier dose titration [1]. The purpose of this study was to externally validate EasyAllo among trial participants who achieved goal SU using protocolized dose escalation. Methods: We included participants in the STOP Gout trial who were randomized to the allopurinol arm, and limited our analyses to those without tophi at baseline who achieved goal SU < 6 mg/dL and completed week 48 of the study to ensure adequate dose escalation and SU capture. All participants fulfilled the 2015 ACR-EULAR gout classification criteria. The trial used protocolized allopurinol dose escalation if SU was ≥6 mg/dL through week 30. Two versions of EasyAllo exist: EasyAllo2, based on weight and creatinine clearance, and EasyAllo1, which also incorporates baseline SU. We used EasyAllo2 in the primary analysis to allow for inclusion of participants taking allopurinol at enrollment whose baseline SU reflected active treatment, and secondarily explored EasyAllo1 among those not already taking allopurinol. In primary analysis, we determined the frequency with which the study dose required to achieve the SU goal < 6 mg/dL between weeks 36 and 48 was at the EasyAllo2 predicted dose or lower. As a secondary aim, we assessed univariate associations between baseline characteristics and being at the EasyAllo predicted dose or lower. We also evaluated whether participants whose study dose was the EasyAllo2 predicted dose at the time of first achieving SU < 6 mg/dL demonstrated superior long-term maintenance of SU < 6 mg/dL compared to participants whose study dose was less than the predicted dose. Results: A total of 291 participants met the inclusion criteria for the primary analysis (Table 2). Approximately 77% (n = 224) of participants who achieved the SU goal < 6 mg/dL between weeks 36 and 48 were on the EasyAllo2 predicted dose or less (Figure 4). Younger age, lower kidney function, and higher SU were associated with requiring allopurinol doses higher than predicted by EasyAllo2 (Table 3). In secondary analysis using EasyAllo1, which includes baseline SU for prediction, younger age, higher baseline weight, and higher SU were associated with allopurinol doses higher than predicted. Considering all participants who ever achieved SU < 6 mg/dL, half (n = 207, 51%) subsequently had SU that was not at goal (≥6 mg/dL). This occurred more frequently among participants on a study dose below the EasyAllo2 predicted dose relative to participants on a study dose at or above the, though, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (55% vs. 45%, p = 0.06). Conclusion: Among participants who achieved SU < 6.0 mg/dL through protocolized allopurinol dose escalation, nearly 3 out of 4 would likely have achieved the SU goal at the EasyAllo2 predicted dose. These findings suggest that EasyAllo2 would perform well in this population with a small proportion requiring additional dose escalation.

- Wright, D.F.B.; Hishe, H.Z.; Stocker, S.L.; Dalbeth, N.; Horne, A.; Drake, J.; Haslett, J.; Phipps-Green, A.J.; Merriman, T.R.; Stamp, L.K. The development and evaluation of dose-prediction tools for allopurinol therapy (Easy-Allo tools). Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 1268–1279.

7. Macrophage Tolerance Regulates the Progression of Atherosclerosis by MSUc

- Benjamin Hemming *, Riley W. Porter, Daniel Ward Phillips, Mohnish Alishala, Xiaoxiao Geng, Stephen Calderon, Faith Inkum, Enchen Zhou, Christian K. Nickl, Kimberley Weldy, Elena Alekseeva, Calvin Yeang, Christopher K. Glass, Monica Guma, Robert Terkeltaub and Isidoro Cobo

- *

- Division of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Heersink School of Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1825 University Blvd, Shelby 1210, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA; bhemming@uab.edu

- Abstract: Background: Gout is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity, including atherosclerosis, yet the immunologic mechanisms remain unclear. We hypothesized that the enhanced atherosclerotic burden in gout patients is driven by local immune activation in response to monosodium urate crystal (MSUc) deposition. Methods: To investigate this, we injected MSUc or PBS into the air pouch of atherosclerosis-prone Ldlr−/− mice fed a Western diet using two injection protocols: Protocol A (Mon/Wed/Fri) and Protocol B (Mon/Tue/Fri). Results: Oil Red O staining and aortic root histology revealed significantly increased lesion area in both groups, with Protocol A inducing more extensive atherosclerosis (Figure 5). These differences occurred without changes in circulating cholesterol, implicating inflammatory timing rather than lipid burden. To assess how prior MSUc exposure alters inflammatory response to rechallenge, we performed sequential MSUc injections following rest intervals of 12 or 16 h, or 1, 2, or 3 days. Remarkably, prior exposure conferred transient protection against secondary challenge, with reduced leukocyte recruitment at 12–24 h and a return to baseline by 48–72 h (Figure 6). Similar tolerance was observed following intraperitoneal MSUc, suggesting systemic coordination. These findings indicate MSUc induces a short-lived innate immune memory response, functionally resembling macrophage tolerance that might be implicated in MSUc-enhanced atherosclerosis. To probe this tolerance mechanistically, we stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with MSUc once or twice, separated by rest intervals ranging from 0 h to 3 weeks. We defined tolerance as reduced inflammatory gene induction upon re-stimulation, and training as amplification of gene expression. Of genes upregulated during the first MSUc exposure, 29% were tolerized and 16% trained after a second exposure (Figure 7). Trained responses diminished by day 3, while tolerance persisted and gradually returned to baseline by 1–2 weeks. Strikingly, tolerance was maintained even after four sequential 5-h MSUc stimulations, indicating a non-exhaustible regulatory program. Conclusions: These findings suggest that MSUc induces a unique state of macrophage adaptation that tempers subsequent inflammatory responses and modulates atherogenic progression. Understanding the molecular underpinnings of this tolerogenic program may uncover new therapeutic strategies aimed at promoting protective immune reprogramming to limit vascular inflammation in gout-associated atherosclerosis.

8. Colocalization of Genetic Association Signals and QTLs Reveals Insights into the Pathogenesi of Gout

- Aichang Ji 1,2,†, Riku Takei 2,†, Richard Reynolds 2, Changgui Li 1 and Tony R.Merriman 2,3,*

- 1

- Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Metabolic Diseases, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 2

- Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

- 3

- Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- *

- Correspondence: tony.merriman@otago.ac.nz

- †

- These authors contributed equally.

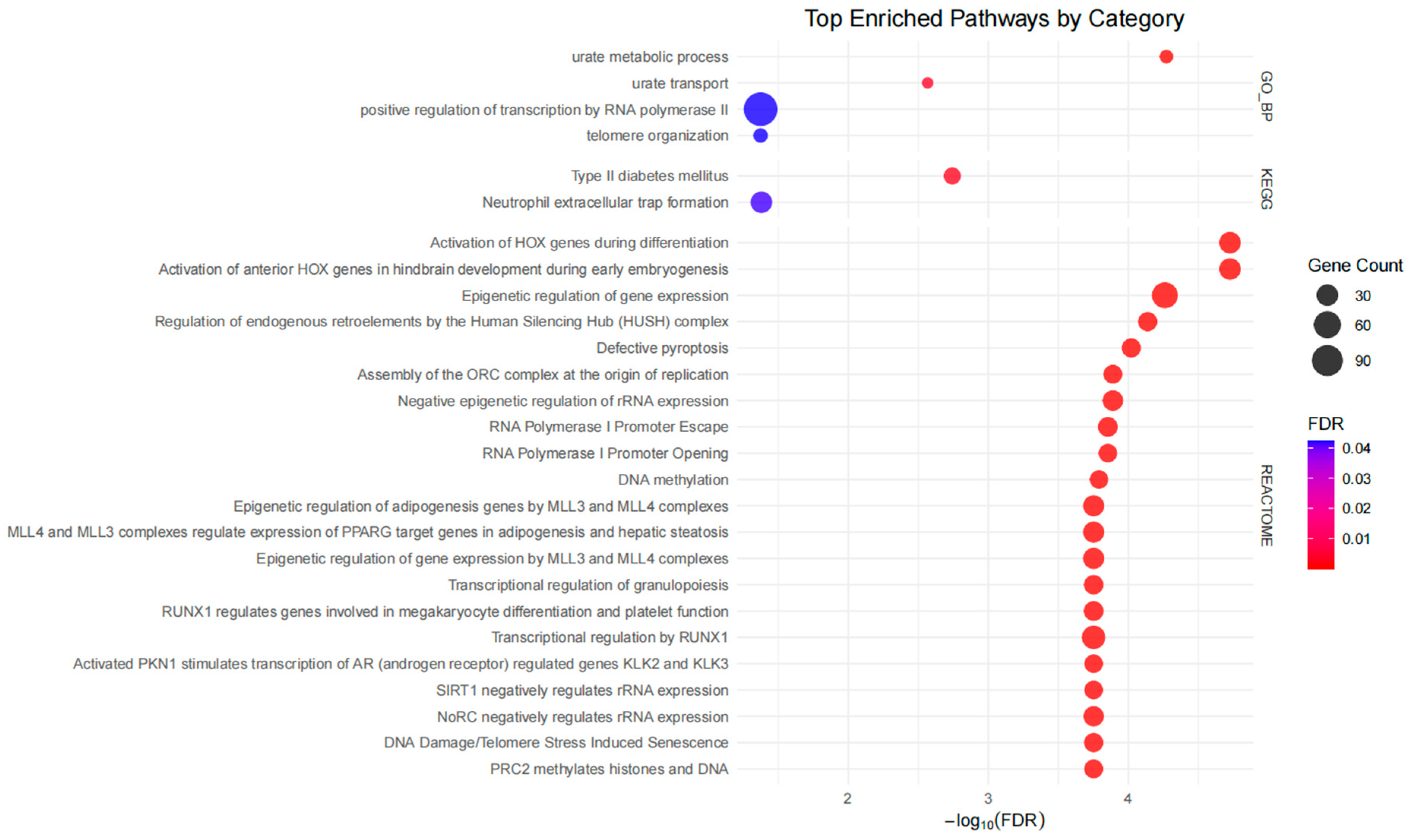

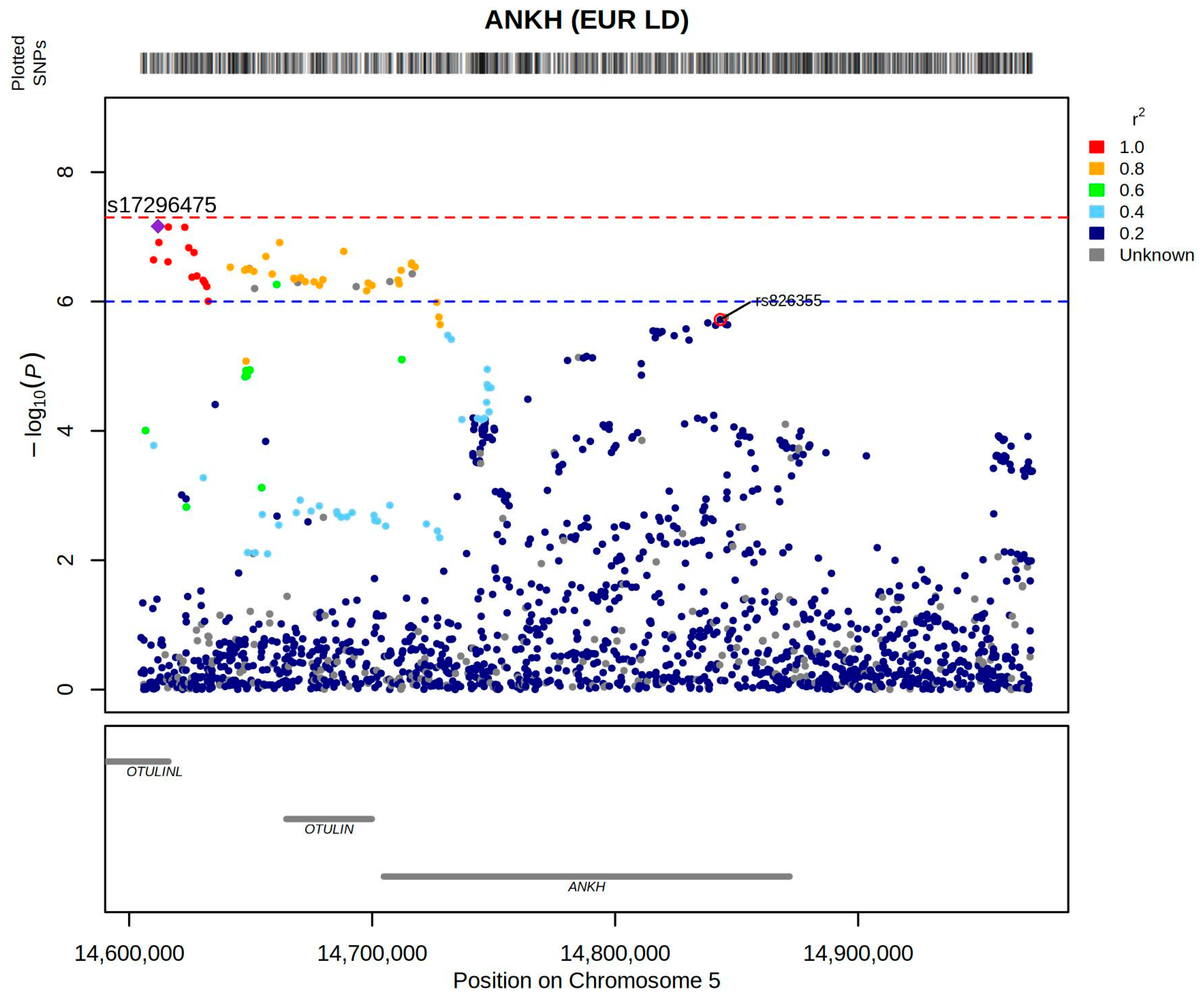

- Abstract: Introduction: Gout is triggered by an innate immune response to monosodium urate crystal deposition. While recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous genetic loci associated with gout, elucidating their functional relevance remains challenging, particularly because most are located in non-coding regions of the genome. In this study, we used colocalization of genetic association signals of gout with quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), alternative splicing QTLs (sQTLs), and protein QTLs (pQTLs) to identify new pathogenic mechanisms and pathways in gout. Method: We conducted the largest GWAS to date involving 2.7 million individuals of European ancestry, including 162,361 individuals with prevalent gout. We performed genetic colocalization analyses with cis expression eQTLs, sQTLs in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database [1], and both cis and trans pQTLs in the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project (UKB-PPP) [2]. A total of 414 lead variants were used for the colocalization analysis using the ‘coloc’ R package [3]. Colocalization analysis was performed using a 1-Mb (±500-kb) region around the lead variant, and genetic loci with posterior probability of co-localization (PPH4) ≥ 0.8 were considered significant. KEGG, Reactome and GO pathway analyses were. Results: We identified 387 loci and 414 genetically independent signals, including 165 novel loci and 193 novel signals not reported in the previous largest European study [4] (Figure 8). Among these, 38 lead variants were missense variants or in strong linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.98) with missense variants, mapping to 40 protein-coding genes and 12 of these genes were newly implicated in gout (Figure 9). Using genetic colocalization analysis, we identified 479 candidate genes via eQTLs and 106 via sQTLs. Enrichment analysis of 1603 unique candidate genes, including those identified by missense variants, eQTLs and sQTLs, and MAGMA gene-set analysis, revealed significant enrichment in 111 pathways. A notable new pathway identified was neutrophil extracellular trap formation (KEGG), which is important in the local immune response in gout [5] (Figure 10). We identified 904 pQTLs. Notably, trans-pQTL signals were extremely common among colocalized pQTLs (895/904 = 99%). Three lead variants, rs4766578 (ATXN2), rs879055593 (ABO), and rs1260326 (GCKR), were each associated with the levels of many proteins (205, 173, and 155, respectively). Pathway analysis of the corresponding 690 pQTL-identified proteins showed enrichment in cell adhesion, immune regulation, and cytokine-receptor interactions. Conclusion: Our integrative genomic analysis reveals the complex molecular mechanisms underlying gout. Colocalization with multiple QTL types provides functional insight into non-coding variants. In particular, the abundance of trans-pQTLs suggests they may regulate gout-related pathways on a systemic level, perhaps by modulating metabolite levels, for example, through epigenomic regulation of gene expression and/or post-translational modification and protein stability.

- Oliva, M.; Muñoz-Aguirre, M.; Kim-Hellmuth, S.; Wucher, V.; Gewirtz, A.D.H.; Cotter, D.J.; Parsana, P.; Kasela, S.; Balliu, B.; Viñuela, A.; et al. The impact of sex on gene expression across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, eaba3066.

- Sun, B.B.; Chiou, J.; Traylor, M.; Benner, C.; Hsu, Y.H.; Richardson, T.G.; Surendran, P.; Mahajan, A.; Robins, C.; Vasquez-Grinnell, S.G.; et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 2023, 622, 329–338.

- Giambartolomei, C.; Vukcevic, D.; Schadt, E.E.; Franke, L.; Hingorani, A.D.; Wallace, C.; Plagnol, V. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genetics 2014, 10, e1004383.

- Major, T.; Takei, R.; Matsuo, H.; Leask, M.P.; Sumpter, N.A.; Topless, R.K.; Shirai, Y.; Wang, W.; Cadzow, M.J.; Phipps-Green, A.J.; et al. A genome-wide association analysis reveals new pathogenic pathways in gout. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 2392–2406.

- Schauer, C.; Janko, C.; Munoz, L.E.; Zhao, Y.; Kienhöfer, D.; Frey, B.; Lell, M.; Manger, B.; Rech, J.; Naschberger, E.; et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 511–517.

9. Explaining Variation in Equitable Urate-Lowering Therapy Uptake: Findings from a Realist Synthesis to Support Context-Sensitive Implementation of Gout Interventions in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Julia Muir 1,*, Rebecca Grainger 2 and Lisa Stamp 1

- 1

- University of Otago Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand

- 2

- University of Otago Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

- *

- Correspondence: julia.muir@otago.ac.nz

- Abstract: Background: Despite the availability of effective and affordable pharmacological treatments for gout, real-world uptake of urate-lowering therapy (ULT) is low. People with gout are often started on ULT but sustained use and long-term maintenance of target serum urate levels are often not maintained, exacerbating inequities in access, quality of care, and outcomes. These uptake challenges persist despite recent efforts to shift gout models of care using multidisciplinary, equitable approaches, suggesting the need to more comprehensively examine factors outside of individual adherence, and consider broader implementation dynamics. This study used a realist synthesis approach to better understand how uptake of ULT is shaped by wider clinical, interpersonal, and systemic processes, with a focus on equity-sensitive delivery contexts. Methods: A hybrid critical realist synthesis was conducted, focusing on the research question: what explains variation in equitable gout outcomes across different care settings and patient populations in interventions aimed at increasing ULT uptake in Aotearoa New Zealand? The synthesis included 48 empirical and conceptual papers from rheumatology, health psychology, and implementation science literature. Context Mechanism Outcome configurations (CMOc) were developed to explain how factors such as intervention delivery, patient experience, and health system design interact to shape equitable uptake. Results: Three key generative mechanisms influenced uptake: (1) Treatment legitimacy, shaped by how medications are introduced, framed, and situated within a patient’s broader life context; (2) Relational trust, mediated by symptom experience, and prior treatment experiences; and (3) Systemic constraint, shaped by shared decision-making, reduced decision-complexity, and redistribution of cognitive load through structured support and streamlined care delivery. These mechanisms failed to activate when services were rigid, fragmented, and/or lacked individualised, culturally responsive communication. This failure particularly impacted Māori and Pacific participants, especially those with more complex health needs or lower socioeconomic resources. Conclusions: Realist methods offer a useful lens for understanding and anticipating variation across patient populations and care settings, and for designing equity-sensitive implementation strategies. Improving uptake requires attention to how the interplay between trust, meaning, and system design shapes real-world ULT use. Moving forward, integrating relational continuity and flexible, structured support into service models may better activate key mechanisms for equitable uptake.

10. Prolonged State of Hyperuricemia Activates the Human Innate Immune System: A Two-Year Follow-Up from the GO TEST Finale Study

- Brenda Kischkel 1, Iris Rose Peeters 2, Alfons A. den Broeder 2, Noortje van Herwaarden 2 and Leo A. B. Joosten 1,3

- 1

- Department of Internal Medicine and Research Institute for Medical Innovation, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Phone: +31-06-84452806. Email: Brenda.Kischkel@radboudumc.nl. Secondary email: brendakischkel@gmail.com

- 2

- Department of Rheumatology, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

- 3

- Department of Medical Genetics, Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- *

- Correspondence: Brenda.Kischkel@radboudumc.nl

- Abstract: Background: Long-term treatment of gout focuses on lowering serum urate (SU) concentrations to prevent the recurrence of gout flares and the formation of tophi. This is achieved primarily through urate-lowering therapy (ULT) [1]. Although EULAR/ACR guidelines recommend lifelong ULT treatment, in clinical practise 46–90% of patients choose discontinuation [2,3]. The debate on the best strategy regarding long-term ULT use is the basis for the GO TEST Finale study, a 2-year follow-up, multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing ULT continuation with ULT discontinuation (with restart in case of recurrent flares/tophi) in patients with gout in prolonged remission while using ULT [4]. Here, we report the long-term effects of ULT discontinuation on the human immune system. Results: A subgroup of patients in the discontinuation arm of the GO TEST Finale study (31 of 155 patients) were enrolled in a sub-study, which included extensive blood sampling at 3-month intervals throughout the study period. At baseline, all patients had SU concentrations below 0.36 mmol/L. Two weeks after stopping ULT, SU levels increased to 0.53 mmol/L [IQR 0.4–0.65] and remained elevated over 2 years. Exposure of primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to monosodium urate (MSU) crystals and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) resulted in increased IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, IL-8, and IL-10 production after 15 months. In contrast, IL-1Ra levels decreased significantly after 12 months. Hematological analysis revealed no significant differences in total counts of monocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, basophils, or eosinophils over time. Of high interest, flow cytometry analysis uncovered an increase in the population of classical monocytes (CD14+CD16−), typically responsible for the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Changes in systemic inflammation were observed using proximity extension assay technology (Olink) to measure 384 inflammation-related proteins in the plasma of these patients. Differently expressed proteins were obtained by linear regression models using age and sex as covariates (Limma R package release 3.22). Patients who restarted ULT were removed from this analysis. Comparison between baseline and 1 and 2 years after ULT discontinuation identified 32 upregulated proteins and 2 downregulated, including FIS1 (p = 0.002), CXCL8 (0.005), HSPA1A (0.006), GZMA (0.012), PRDX5 (0.018), TNFRSF11A (0.029), and TNFRSF14 (0.047). These proteins are linked to processes such as inflammation, cell death, neutrophil recruitment, and antioxidant defence. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that after ULT discontinuation, PBMCs exhibit increased responsiveness over time, producing higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to endogenous stimuli in vitro. This effect may be related to prolonged cellular exposure to urate and potential epigenetic reprogramming. Additionally, systemic changes observed in plasma after 1 and 2 years suggest the development of a persistent low-grade inflammatory state. Future directions include generating transcriptomic and epigenomic profiles and extending patient follow-up for another three years.

- Richette, P.; Flendrie, M.; Joosten, L.A.B.; van Herwaarden, N. Can urate lowering therapy be stopped in gout? Rationale and Design of Two Large Randomised Trials. Gout Urate Cryst. Depos. Dis. 2025, 3, 2.

- Richette, P.; Doherty, M.; Pascual, E.; Barskova, V.; Becce, F.; Castañeda-Sanabria, J.; Coyfish, M.; Guillo, S.; Jansen, T.L.; Janssens, H.; et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 29–42.

- FitzGerald, J.D.; Dalbeth, N.; Mikuls, T.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Guyatt, G.; Abeles, A.M.; Gelber, A.C.; Harrold, L.R.; Khanna, D.; King, C.; et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 879–895.

- Peeters, I.R.; den Broeder, A.A.; Taylor, W.J.; den Broeder, N.; Flendrie, M.; van Herwaarden, N. Urate-lowering therapy following a treat-to-target continuation strategy compared to a treat-to-avoid-symptoms discontinuation strategy in gout patients in remission (GO TEST Finale): study protocol of a multicentre pragmatic randomized superiority trial. Trials 2023, 24, 282.

11. Health Care Utilization Patterns Among Patients Presenting to Emergency Department for Gout Flares in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Retrospective Observational Study

- Timothy S.H. Kwok 1,2,*, Samantha Morais 3, Ping Li 3, William K. Silverstein 4,5, Clare L. Atzema 3,5,6,7, Gregory Choy 1, Priyanka Chandratre 8,9 and Jessica Widdifield 2,3,7

- 1

- Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada

- 2

- Holland Bone & Joint Program, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, Canada

- 3

- ICES, Toronto, Canada

- 4

- Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada

- 5

- Integrated Community Care, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, Canada

- 6

- Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada

- 7

- Institute of Health Policy, Management & Evaluation, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada

- 8

- Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada

- 9

- Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- *

- Correspondence: timothysh.kwok@utoronto.ca

- Abstract: Background: Gout flares can be intensely painful, leading patients to seek care in emergency departments (ED). Although gout can typically be effectively managed in outpatient settings, high rates of ED use may indicate potential gaps in ambulatory chronic disease management. To inform targeted improvements in gout healthcare delivery, we assessed annual ED visits for gout and identified patient characteristics and health services patterns that may be contributing to ED presentations. Methods: Using province-wide health administrative data, we performed a population-based retrospective observational study, identifying the annual number of gout ED visits occurring between 2014 and 2023 in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. Annual total and incident ED gout visits were separately determined, then stratified by sex and age. Annual rates were estimated using population denominators. We described clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and assessed patient-level health care usage factors both preceding and after the gout ED visit. Repeat ED presentations and hospitalizations were determined within 90-days. Among individuals aged ≥66 years, we further assessed dispensations for flare abortive medications, urate-lowering therapy, and opioids within a 30-day window. Results: The mean age of individuals presenting to the ED was 59.7 (SD 16.4), and 77.5% were male. Annual ED gout encounters peaked in 2018 with 14,017 total encounters translating to an annual crude rate of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97 to 1.01) and male-stratified annual rate of 1.56 (95% CI: 1.53 to 1.59) visits per 1000-persons (Figure 11). Older adults had the highest ED visit rates at 3.01 (95% CI: 2.89 to 3.15) visits per 1000-persons in the 75 to 84 age group in 2015 (Figure 12). Between 2014 and 2023, there were 125,505 gout ED visits in Ontario, including 86,824 incident visits. Patients were predominantly from lower-income neighborhoods and resided in less racially diverse areas. Patients were highly comorbid with 55.5% of patients with ≥10 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups. Common comorbidities included hypertension (57.7%), diabetes (24.0%), cardiovascular (5.8%) and renal disease (4.6%). By 30-days post-ED encounter, 28.3% and 21.3% of patients were dispensed a flare abortive medication or attended an ambulatory physician visit for gout, respectively, while 10.3% were dispensed an opioid. By 6 months, 38.1% of patients had serum urate testing (Table 4). By 90 days, 29.9% of encounters led to ED re-presentation, with 9.4% of total encounters representing specifically for gout, culminating in 6.2% (1.5% for gout) of total encounters leading to hospital admission. Findings were comparable for incident ED gout visits. Conclusion: In what is one of the first Canadian population-based assessments of acute care use for gout, our work suggests that there is a large burden of ED visits, with suboptimal post-ED health services use, marred by under-prescribing of flare medications, over-prescribing of opioids and high acute care representation rates. Quality improvement efforts should be directed at strategies to prevent upstream ED presentations for gout and enhancing appropriate follow-up care.

12. Epigenetic Clocks Reveal Accelerated Aging in Patients with Gout and Individuals with Hyperuricemia

- Medeea Badii 1,2, Zhaoli Liu 3, Mohamad Ballan 3, Orsolya Gaal 1,2, Georgiana Cabău 1, Valentin Nica 1, Ancuta R. Straton 1, Ioana Hotea 4, HINT Consortium, Cristina Pamfil 4, Simona Rednic 4, Radu A Popp 1, Cheng-Jian Xu 3, Tania O Crişan 1,2,* and Leo A B Joosten 1,2

- 1

- Department of Medical Genetics, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 400349 Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- 2

- Department of Internal Medicine and Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences (RIMLS), Radboud University Medical Centre, 6525GA Nijmegen, The Netherlands

- 3

- Centre for Individualized Infection Medicine (CiiM), a joint venture between Hannover Medical School and Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, 30625 Hannover, Germany

- 4

- Department of Rheumatology, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- 5

- Centre for Individualized Infection Medicine (CiiM), a joint venture between Hannover Medical School and Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, 30625 Hannover, Germany

- 6

- Department of Rheumatology, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- *

- Correspondence: tania.crisan@gmail.com

- Abstract: Introduction: Epigenetic clocks are predictive models trained on DNA methylation at CpG sites to estimate biological age, offering valuable insights that may differ from an individual’s chronological age. These tools are central in aging research, enabling the assessment of age-related health and disease risk. Hyperuricemia is a metabolic disorder that plays a key role in the onset of gout. This study aims to explore whether hyperuricemia and gout are associated with accelerated biological aging by analyzing DNA methylation patterns and immune cell proportions in the whole blood of individuals with normouricemia, asymptomatic hyperuricemia, and gout. Methods: DNA methylation profiles were obtained using the Infinium EPIC v2 array across 150 normouricemic controls, 128 individuals with asymptomatic hyperuricemia, and 148 patients with gout. Beta values were extracted with the getBeta function from the preprocessFunnorm package in R. Epigenetic age was estimated using three established DNA methylation clocks: Horvath, Hannum and PhenoAge. DNA methylation age (DNAmAge) was estimated using the methylclock package in R. Epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) was calculated as the residuals from regressing DNAmAge on chronological age. Blood cell counts were inferred from DNA methylation data with FlowSorted.Blood.EPIC. Results: DNAmAge (expressed in years) correlated strongly with chronological age across all groups and clocks. Welch’s ANOVA with Games-Howell post hoc testing revealed significantly increased epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) in gout based on the Hannum clock (+1.75 years, p = 0.004) and in both gout and hyperuricemia based on PhenoAge (+3.38 and +3.64 years, p = 0.002) compared to controls. No significant differences were found using the Horvath clock. Significant immune cell shifts were observed in gout and hyperuricemia, including reduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and increased neutrophils, with monocytes elevated in gout. Across all groups, both chronological age and DNAmAge (Horvath, Hannum, PhenoAge) were inversely correlated with T cells and positively with neutrophils. We assessed whether the association between cell types and epigenetic age acceleration varied by group. In gout, neutrophils and monocytes were linked to Horvath and PhenoAge EAA; monocytes also showed associations in hyperuricemia. For Hannum, only monocytes were significant in gout. No significant effects were seen in hyperuricemia for Hannum or PhenoAge. Conclusion: These findings suggest that biological aging may be accelerated in disease states such as gout and hyperuricemia. While Hannum and PhenoAge clocks revealed significant epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) in these groups, the Horvath clock did not show group-level differences. However, interaction analyses indicated that in gout, higher neutrophil and monocyte levels were significantly associated with Horvath, suggesting that immune cell shifts may contribute to or reflect intrinsic aging processes in disease contexts. However, further analyses are warranted to validate and extend these observations.

13. Characterisation of Clinical Phenotypes in CPPD by Hierarchical Analysis in Two Large Cohorts of Patients

- Greta Pellegrino 1,*, Laurène Norberciak 2, Silvia Sirotti 1, Abhishek Abhishek 3, Mariano Andrès 4, Edoardo Cipolletta 5, Julien Damart 6, Renaud Desbarbieux 7, Pilar Diez 4, Vincent Ducoulombier 6, Hang-Korng Ea 8,9, Emilio Filippucci 5, Charlotte Jauffret 6, Augustin Latourte 8,9, Jean-Guillaume Letarouilly 10, Sébastien Ottaviani 11, Pascal Richette 8,9, Pierre Robinet 6, Georgios Filippou 1,† and Tristan Pascart 6,†

- 1

- Department of Rheumatology, IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi, Milan, Italy

- 2

- Department of Biostatistics and Methodology, Saint-Philibert Hospital, Lille Catholic University, Lille, France

- 3

- Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

- 4

- Department of Rheumatology, Dr Balmis General University Hospital-ISABIAL, Miguel Hernandez University, Alicante, Spain

- 5

- Rheumatology Unit, Department of Clinical and Molecular Sciences, Polytechnic University of Marche, Ancona, Italy

- 6

- Department of Rheumatology, Saint-Philibert Hospital, Lille Catholic University, Lille, France

- 7

- Department of Rheumatology, Boulogne-sur-Mer Hospital, Boulogne-sur-Mer, France

- 8

- Hôpital Lariboisière, APHP-Nord, Service de Rhumatologie, 2 rue Ambroise Paré, Paris, France

- 9

- Bioscar UMR Inserm 1132 and Université de Paris Cité, Paris, France

- 10

- Université de Lille, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Lille, MABLab ULR 4490, Service de Rhumatologie, Lille, France

- 11

- Department of Rheumatology, Hôpital Bichat APHP Paris Nord and Université de Paris, Paris, France

- *

- Correspondence: greta.pellegrino@unimi.it

- †

- Shared co-author.

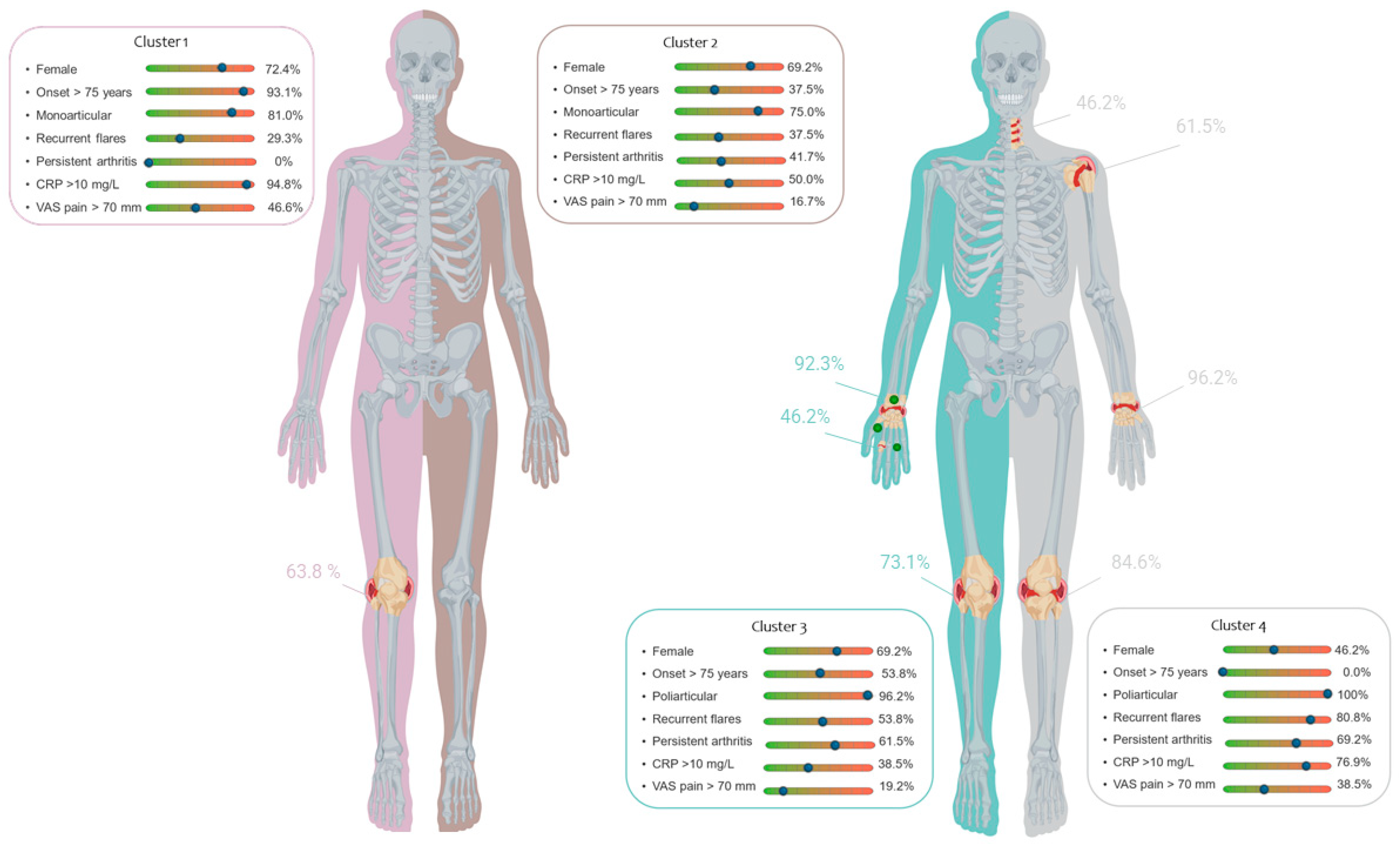

- Abstract: Background: Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease is a heterogeneous condition, ranging from monoarticular to polyarticular involvement and from acute to chronic arthritis. It is frequently misdiagnosed, as it mimics other musculoskeletal disorders. In 2011, the EULAR task force proposed four phenotypes based on expert opinion. However, these phenotypes show substantial overlap and they were never validated in real-world patient cohorts. Objective: The aim of this study was to identify, for the first time using rigorous methodology, clinical phenotypes of CPPD disease by integrating real-world data from two datasets. Methods: Data from the COLCHICORT randomised controlled trial and CHRONIC-CPPD European observational cohort were analysed. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was employed to evaluate and visualize the association between modalities of qualitative variables. Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) obtained from MCA identified clusters based on the Ward agglomeration method with Euclidean distance. A bivariate analysis between clusters was then performed to characterize the clusters numerically. Results: A total of 227 patients were included in the analysis, 98 patients from the COLCHICORT study and 129 patients from the CHRONIC CPPD study. Due to missing data, the final analysis was conducted on 134 patients. A 4-cluster partition emerged from the visual analysis of the dendrogram (Figure 13). The distribution of patients across these clusters was as follows: Cluster-1 (43.3%), Cluster-2 (17.9%), Cluster-3 (19.4%), and Cluster-4 (19.4%). The demographic, clinical, laboratory and imaging characteristics are shown in Table 5 and summarized in Figure 14. Two phenotypes demonstrated predominantly monoarticular involvement: Cluster-1, corresponding to the EULAR-defined “acute CPP crystal arthritis”, and Cluster-2, which does not fully align with any EULAR-defined phenotype. In Clusters-3 and -4, there were the most clinically burdened group of patients, with a higher number of affected joints and persistent arthritis. Cluster-3 could be considered equivalent to the “chronic CPP crystal arthritis” phenotype proposed by EULAR, as it is characterized by polyarticular arthritis, particularly involving the wrist and knee joints. Cluster-4 represents the most intriguing finding of our study, as it includes patients with a high frequency of polyarticular involvement, affecting the shoulders and the spine in a large proportion of patients. It mostly affects males and younger patients and CRP values are frequently elevated. Cluster-4 appears to be a “new” cluster that in many cases could be mistaken for Polymyalgia Rheumatica with synovitis. Conclusions: In conclusion, by using for the first time a robust, data-driven methodology based on real-world data, two clusters similar to the EULAR phenotypes “acute CPP crystal arthritis” and “chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis” were confirmed, but in addition, two more clusters that do not correspond to any existing EULAR phenotypes were also identified. Future research should aim to validate these findings in larger prospective cohorts or registries to further refine CPPD phenotypes.

14. Local MSUc Gout Inflammation Accelerates Atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− Mice by Expanding an EMP1+ Monocyte Population Systemically via DNMT3A and Type-I IFN Signaling

- Daniel Ward Phillips 1,*, Benjamin Hemming 1, Riley W. Porter 1, Mohnish Alishala 2, Xiaoxiao Geng 3, Stephen Calderon 2, Faith Inkum 1, Enchen Zhou 2, Christian K. Nickl 2, Kimberley Weldy 4, Elena Alekseeva 4, Calvin Yeang 4, Christopher K. Glass 5, Monica Guma 6,7, Robert Terkeltaub 8 and Isidoro Cobo 1,3,9

- 1

- Division of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA

- 2

- Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California San Diego, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

- 3

- Department of Biomedical Engineering, School of Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA

- 4

- Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

- 5

- Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California San Diego, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

- 6

- Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology. UCSD School of Medicine, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, USA

- 7

- Department of Medicine, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Plaça Cívica, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain

- 8

- Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Department of Medicine, University of California, 9500 Gilman Drive, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, 92093, USA

- 9

- CAMBAC (Comprehensive Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, Bone and Autoimmunity Center), University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA

- *

- Correspondence: dp2201@uab.edu

- Abstract: The role of gout in driving atherosclerosis progression remains unclear. Monocyte–macrophage lineage cells respond to monosodium urate crystals (MSUc) by producing inflammatory cytokines, contributing to a heightened immune state. To model this in vivo, we utilized the air pouch system to induce gouty inflammation in Ldlr−/− mice fed with a Western diet. Mice received intra-pouch injections of MSUc or PBS (control) three times weekly for twelve weeks (Figure 15A). Oil Red O staining of aortas revealed significantly increased lesion area in MSUc-treated animals (Figure 15B,C). Histological examination of the aortic root using H&E staining confirmed greater plaque burden in the MSUc group, despite no significant changes in serum cholesterol (Figure 15D,E). These results indicate that MSUc-mediated local inflammation can potentiate atherosclerosis independent of systemic lipid alterations. To evaluate broader immune effects, we performed bulk RNA sequencing on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), comparing them to bone marrow (BM) cells, Kupffer cells (KCs), and microglia (MG) after MSUc treatment. PBMCs were the only cell type to exhibit both significant transcriptional changes and upregulated inflammatory signaling pathways (Figure 16A,B), underscoring their unique systemic role following local MSUc exposure. Key upregulated genes included inflammatory chemokines (Ccl2, Ccl7, Cxcl3), tissue remodeling factors (Mmp19), immune modulators (Dab2, Clec7a, Ms4a4a), and Emp1 (Figure 16C). Notably, Emp1 expression was significantly increased in circulating monocytes isolated from MSUc-injected mice assessed by single-cell RNA-Seq (Figure 16D). Interestingly, Emp1 is among the genes upregulated during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, suggesting that the systemic inflammatory response to MSUc primes monocytes toward an activated, macrophage-like phenotype (Figure 16E). We next investigated DNMT3A, a gene frequently mutated in clonal hematopoiesis and associated with both gout and atherosclerosis, as a regulator of EMP1. Knockdown of DNMT3A in primary human monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) led to a marked increase in EMP1 expression (Figure 17A,B). Notably, DNMT3A binds to the EMP1 promoter by ChIP-Seq, indicating direct regulation (Figure 17C). Additionally, modulation of interferon signaling—which is upregulated in DNMT3A-mutant settings—further influenced EMP1 levels (Figure 17D). Our study demonstrates that gout-like inflammation driven by MSUc can accelerate atherosclerosis through systemic activation of PBMCs and upregulation of EMP1. This response is amplified by loss of DNMT3A and altered interferon signaling, highlighting a potential mechanistic link between clonal hematopoiesis, gouty inflammation, and cardiovascular disease progression.

15. Molecular Mechanisms Driving Divergent Response to Monosodium Urate Crystals in Genetically Distinct Macrophages Driven by PPARG

- Riley W. Porter *, Benjamin Hemming, Daniel W. Phillips, Zeyang Shen and Isidoro Cobo

- Division of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Heersink School of Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA; rwporter@uab.edu

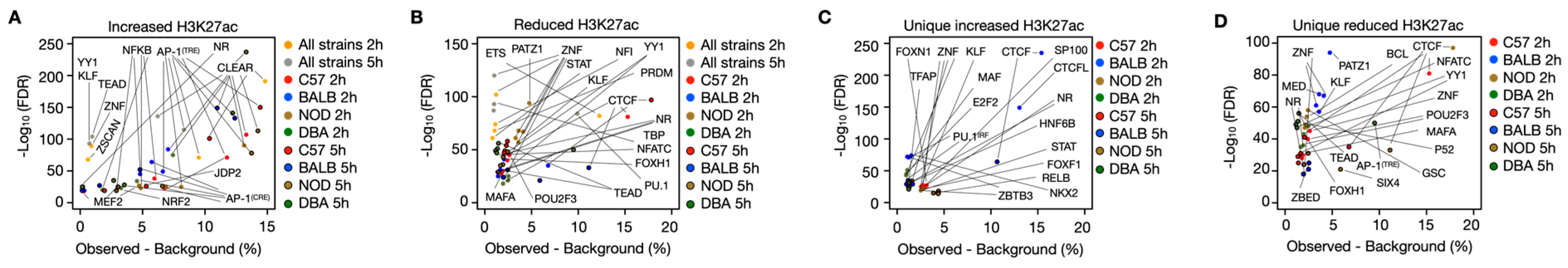

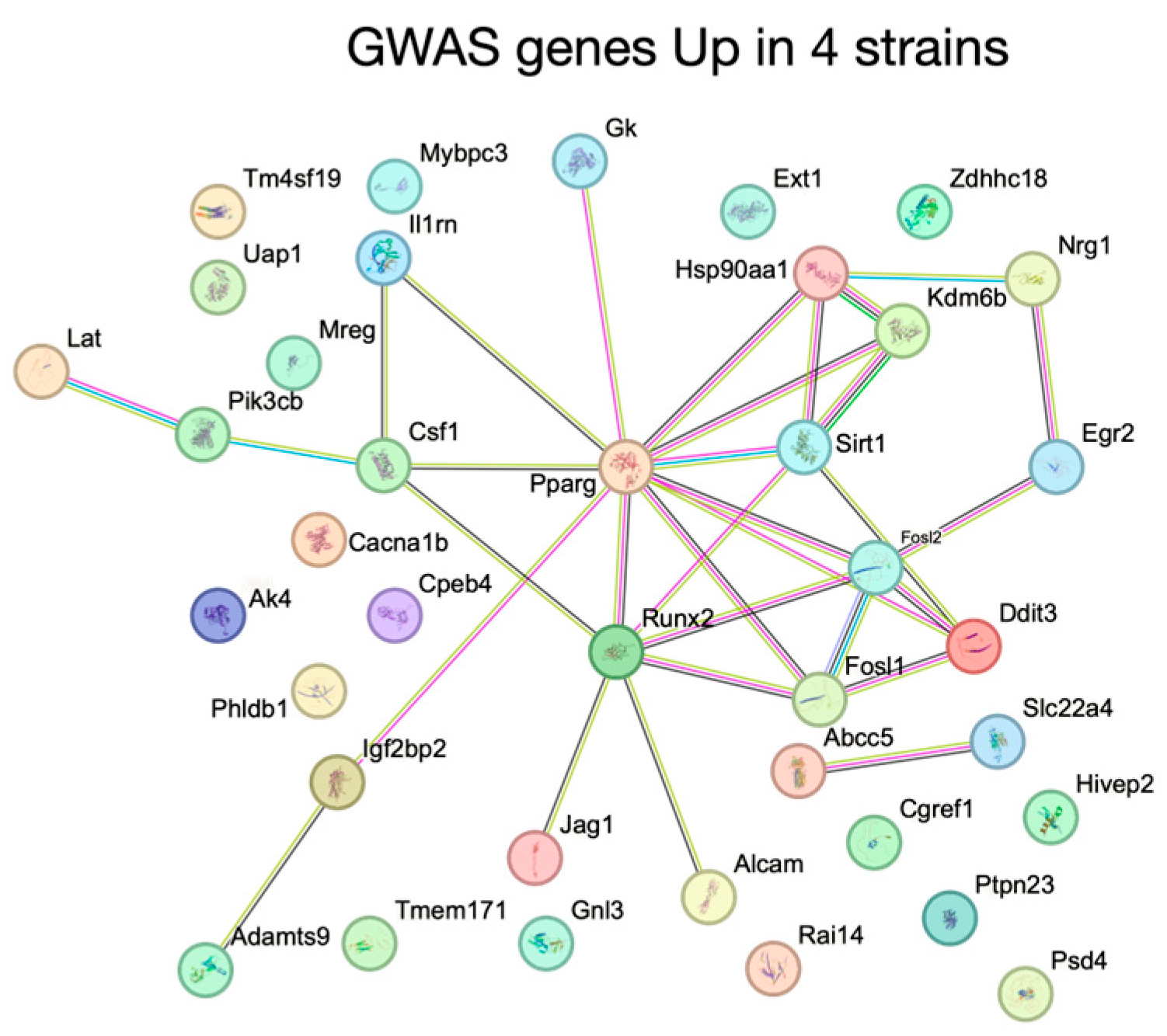

- Abstract: The influence of noncoding genetic variation on macrophage gene expression is not yet fully understood, but it is widely recognized as a major factor shaping phenotypic diversity and disease susceptibility. In our study, we analyzed four inbred mouse strains to determine how their genetic variations affect macrophage responses to monosodium urate crystals (MSUc), which trigger the acute inflammatory response characteristic of gout. We chose C57, BALB, NOD and DBA, as combined they provide over 2 million ins/del/SNPs based on our previous publication [1]. Across the four strains, MSUc treatment dysregulated over 5000 genes by more than two-fold, yet only 16% of those genes were shared across all strains (Figure 18A–D). Similarly, of the more than 75,000 enhancer regions showing at least a two-fold change in response to MSUc assessed by H3K27ac ChIP-Seq, fewer than 10% were common to every strain (Figure 18E–H). DBA macrophages displayed the largest overall transcriptional shift, both under basal conditions and upon MSUc stimulation, suggesting heightened susceptibility. In contrast, the C57 and NOD strains exhibited more restrained responses, with fewer differentially expressed genes and enhancers, indicating variability in inflammatory potential driven by genetic background (Figure 18). By examining histone modifications in macrophages from each strain, we identified distinct combinations of transcription factors governing strain-specific responses to MSUc, contributing to unique gene-expression patterns and phenotypic diversity. DBA macrophages uniquely upregulated genes linked to nitric oxide signaling, inflammatory cytokine regulation, and transcriptional networks. BALB macrophages activated genes involved in tissue remodeling and extracellular matrix organization. NOD macrophages were enriched for cytoskeletal reorganization, immune-complex handling, and complement pathways, whereas C57 macrophages emphasized apoptosis, cell migration, and adhesion (Figure 19). Importantly, by cross-referencing our mouse data with a recently published gout genome-wide association study (GWAS), we identified a significant overlap between strain-specific transcriptional responses and human genetic susceptibility to gout, particularly in Nuclear Receptor Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma, which lies at the core of the GWAS gene regulatory network associated with increased expression and higher enhancer activity (Figure 20). This integrative analysis suggests that gout-associated genetic variants contribute to divergent transcriptional responses in macrophages upon MSUc stimulation. In particular, the distinct inflammatory and metabolic signatures observed highlight the critical role of genetic background in modulating disease susceptibility and pathogenesis. Our data clearly indicates that the Nuclear Receptor family, particularly PPARG, is a novel transcriptional regulator of macrophage response to MSUc, whose genomic regions confer gout susceptibility as defined in the latest gout GWAS [2].

- Hoeksema, M.A.; Shen, Z.; Holtman, I.R.; Zheng, A.; Spann, N.J.; Cobo, I.; Gymrek, M.; Glass, C.K. Mechanisms underlying divergent responses of genetically distinct macrophages to IL-4. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf9808.

- Major, T.J.; Takei, R.; Matsuo, H.; Leask, M.P.; Sumpter, N.A.; Topless, R.K.; Shirai, Y.; Wang, W.; Cadzow, M.J.; Phipps-Green, A.J.; et al. A genome-wide association analysis reveals new pathogenic pathways in gout. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 2392-2406.

16. Exploring the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Gout: Prospective Analysis of Dietary Fiber Intake and the Risk of Gout

- Sharan K. Rai 1,2,3,4, Natalie McCormick 1,2,3,4, Chio Yokose 1,2,3, Robert A. Terkeltaub 5, Dylan Dodd 6,7, Lama Nazzal 8, Huilin Li 9, Gary C. Curhan 2,10,11, Qi Sun 2,10,12,13,† and Hyon K. Choi 1,2,3,4,10,†

- 1

- Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

- 2

- Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

- 3

- The Mongan Institute, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

- 4

- Arthritis Research Canada, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 5

- Division of Rheumatology, Autoimmunity and Inflammation, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

- 6

- Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

- 7

- Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

- 8

- Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA

- 9

- Division of Biostatistics, Department of Population Health, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA

- 10

- Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

- 11

- Division of Renal (Kidney) Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

- 12

- Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

- 13

- Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

- *

- Correspondence: srai1@mgh.harvard.edu

- †

- Co-senior authors.

- Abstract: Background/Objectives: The role of the gut microbiome has been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of gout. For instance, gout patients have shown depletion of bacteria that lower urate levels or produce anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Dietary fiber is fermented by the gut microbiota and produces beneficial microbial metabolites, including SCFAs [1]. Accordingly, greater dietary fiber (particularly cereal fiber) intake is also associated with lower levels of inflammatory biomarkers [2], which may be particularly relevant to gout. Indeed, prior work has found that a pro-inflammatory diet that is low in dark leafy and yellow vegetables as well as high in refined grains is associated with a nearly two-fold increased risk of gout among women [3]. Taken together, these data suggest that dietary fiber may play a role in gout prevention through the modulation of gut microbiota and the corresponding inflammatory pathway. We aimed to prospectively examine whether long-term dietary fiber intake is associated with the risk of gout among women over 34 years of follow-up. Methods: We analyzed data from 80,175 women in the Nurses’ Health Study with complete dietary data who were free from gout at baseline. We used a validated food frequency questionnaire to collect repeated measures of usual intake of 130+ food and beverage items every four years. We calculated dietary fiber intakes for all participants using the Harvard University Food Composition Database. In addition to total fiber, we calculated individual intakes of fiber sourced from cereals, fruits, vegetables, and legumes. Every two years, we collected updated data on relevant covariates as well as new confirmed cases of incident gout. We used multivariable Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the associations between quintiles of dietary fiber intake and incident gout. Results: We documented 1117 gout cases over 2,218,527 person-years of follow-up. At baseline, women consuming more total fiber tended to be older (Q1 vs. Q5: 49.3 vs. 53.3 years), be more physically active (Q1 vs. Q5: 10.5 vs. 19.0 metabolic equivalent of task hours/week), and consume less alcohol (Q1 vs. Q5: 11.5 vs. 4.2 g/day). After multivariable adjustment, greater intake of total dietary fiber was associated with a 31% lower risk of incident gout, comparing extreme quintiles (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.69 (95% confidence interval: 0.56 to 0.87); p for trend = 0.001) (Table 6). This protective association was primarily driven by cereal fiber (from food sources such as cold cereals, dark breads (e.g., rye, pumpernickel, wheat, oatmeal, or other whole grain breads), cooked oatmeal, and added bran) (multivariable HR comparing extreme quintiles = 0.61 (0.50 to 0.76); p for trend < 0.001) and fruit fiber (multivariable HR comparing extreme quintiles = 0.81 (0.65 to 1.00); p for trend = 0.009) (Table 6). Conclusion: Long-term dietary intake of fiber, particularly fiber sourced from cereals and fruits, is independently associated with a lower risk of incident gout among women. These findings support a role for fiber in the pathogenesis of gout, potentially by modulating the gut microbiome.

- Sawicki, C.M.; Livingston, K.A.; Obin, M.; Roberts, S.B.; Chung, M.; McKeown, N.M. Dietary Fiber and the Human Gut Microbiota: Application of Evidence Mapping Methodology. Nutrients 2017, 9, 125. PMID: 28208609.

- Shivakoti, R.; Biggs, M.L.; Djoussé, L.; Durda, P.J.; Kizer, J.R.; Psaty, B.; Reiner, A.P.; Tracy, R.P.; Siscovick, D.; Mukamal, K.J. Intake and Sources of Dietary Fiber, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease in Older US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e225012. PMID: 35357453.

- Rai, S.K.; Choi, H.K.; Lu, N.; Yokose, C.; Lin, K.; Lee, D.H.; Tabung, F.K.; McCormick, N. Proinflammatory Dietary Pattern and the Risk of Female Gout: Sex-Specific Findings From Three Prospective Cohort Studies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025, 77, 1077–1086. PMID: 39866115.

17. Hospital Burden of Crystal-Related Arthritis in Spain: A Nationwide Dataset of 214,635 Inpatients

- Cristina Rodríguez-Alvear 1, Fernando Borrás 2 and Mariano Andrés 3

- 1

- Rheumatology Section, Virgen de la Peña General Hospital, Fuerteventura, Spain

- 2

- Rheumatology Section, Dr. Balmis General University Hospital, Miguel Hernandez University, Alicante, Spain

- 3

- Statistics, Mathematics and Informatics, Miguel Hernández University, San Juan de Alicante, Spain

- *

- Correspondence: rodriguezalvearcristina@gmail.com

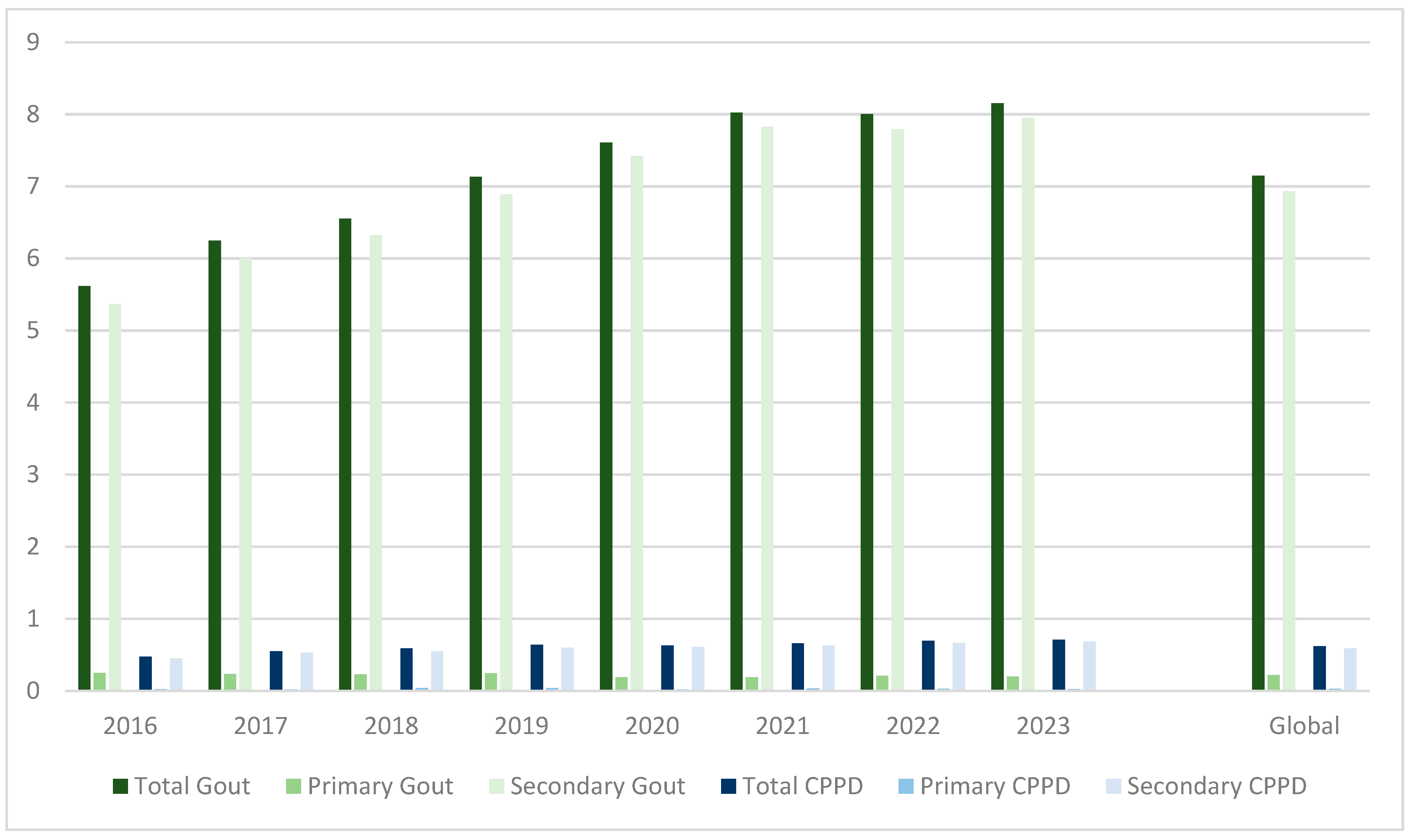

- Abstract: Introduction/Purpose: Gout and calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (CPPD) disease are frequent in hospital settings. In Spain, the last available data (2005–2015) indicated that 0.48% of hospital discharges had a gout diagnosis, with rising prevalence and mortality within the period [1]. Conversely, no national studies exist for CPPD disease. We aimed to analyze prevalence, hospital stays, mortality, and costs of inpatients with gout or CPPD disease in Spain between 2016 and 2023. Methods: We audited the Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) of the National Health Service for adult patients with coded diagnoses of either primary or secondary gout (ICD-10-ES M10.X or M1A.X) or CPPD disease (M11.X), admitted to public hospitals between 2016 and 2023. Prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated over annual discharges. Differences in age, sex, mean stay, mortality, and costs (based on All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups) were analyzed between patients with gout and CPPD, stratified by being primary or secondary diagnoses. Results: We retrieved 214,635 hospitalizations with gout or CPPD disease over the 2016–2023 period. Gout prevalence was 0.71% (n = 196,643/27,508,613; 95% CI 0.71–0.72%), coded as primary diagnosis in 6030 (3.07%) and secondary in 190,613 (96.93%). Meanwhile, the prevalence of CPPD disease was 0.06% (n = 16,997/27,508,613; 95% CI 0.06–0.06%), mostly as secondary diagnoses (95.21%, n = 16,182). The hospitalizations with gout and CPPD disease increased over the period, in particular as secondary diagnoses (Table 7; Figure 21). A total of 995 patients (0.46%) had both crystal diagnoses. Compared to patients with gout, those with primary or secondary CPPD disease were older (74.5 0± 14.4 vs. 70.9 ± 14.3 years, p < 0.001; 79.9 ± 10.8 vs. 74.9 ± 12.1 years, p < 0.001) with a female predominance (53.4% vs. 16.2%, p < 0.001; 60.1% vs. 16.6%, p < 0.001). The average age steadily increased up to +2.0 years in gout (p = 0.005) and +3.8 years (p = 0.001) in CPPD disease as primary diagnoses during the study period. Mean hospital stay was significantly longer in gout (6.4 ± 6.9 vs. 5.5 ± 5.1 days, p < 0.001). The stay decreased for secondary groups (Gout: −0.95 days, p < 0.001; CPPD disease: −0.32 days, p = 0.001). The intra-hospital mortality rate in cases with primary diagnosis of gout or CPPD disease were 0.7% and 0.1%, respectively (p < 0.001). A similar figure was noted for secondary diagnoses (6.1% vs. 4.9%, p < 0.001). Mortality increased significantly in gout diagnoses (Primary: +0.2%, p = 0.002; Secondary: +1.4%, p < 0.001) and secondary CPPD disease diagnoses (+2.3%, p < 0.001). Costs were similar in gout and CPPD disease-related hospitalizations (3677.11 € vs. 3692.00 €), but higher in the case of secondary diagnoses of gout (5385.08 € vs. 5003.57 €, p < 0.001). In all cases, mean costs increase progressively. Conclusions: The updated nationwide hospital prevalence of gout is higher than earlier reports. The first national CPPD disease data is provided. Despite CPPD disease predominating in older patients and women, hospital stays and intrahospital mortality were notably higher in gout. Hospitalizations, admission ages, costs, and mortality rates progressively increased during the study period. Thus, crystal-related arthritis still carries a significant hospital burden.

- Benavent, D.; Peiteado, D.; Martinez-Huedo, M.Á.; Hernandez-Hurtado, M.; Balsa, A.; de Miguel, E. Healthcare-related impact of gout in hospitalized patients in Spain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13287.

18. Proteomic Signature in Hyperuricemic People Living with HIV

- Ancuta R. Straton 1,*, Nicholas A. Sumpter 2, Nadira Vadaq 2,3, Jéssica C. dos Santos 2, André J.A.M. van der Ven 2, Tania O. Crisan 1,2 and Leo A.B. Joosten 1,2

- 1

- Department of Medical Genetics, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- 2

- Department of Internal Medicine and Research Institute for Medical Innovations (RIMI), Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

- 3

- Division of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia

- *

- Correspondence: anca.straton1@gmail.com

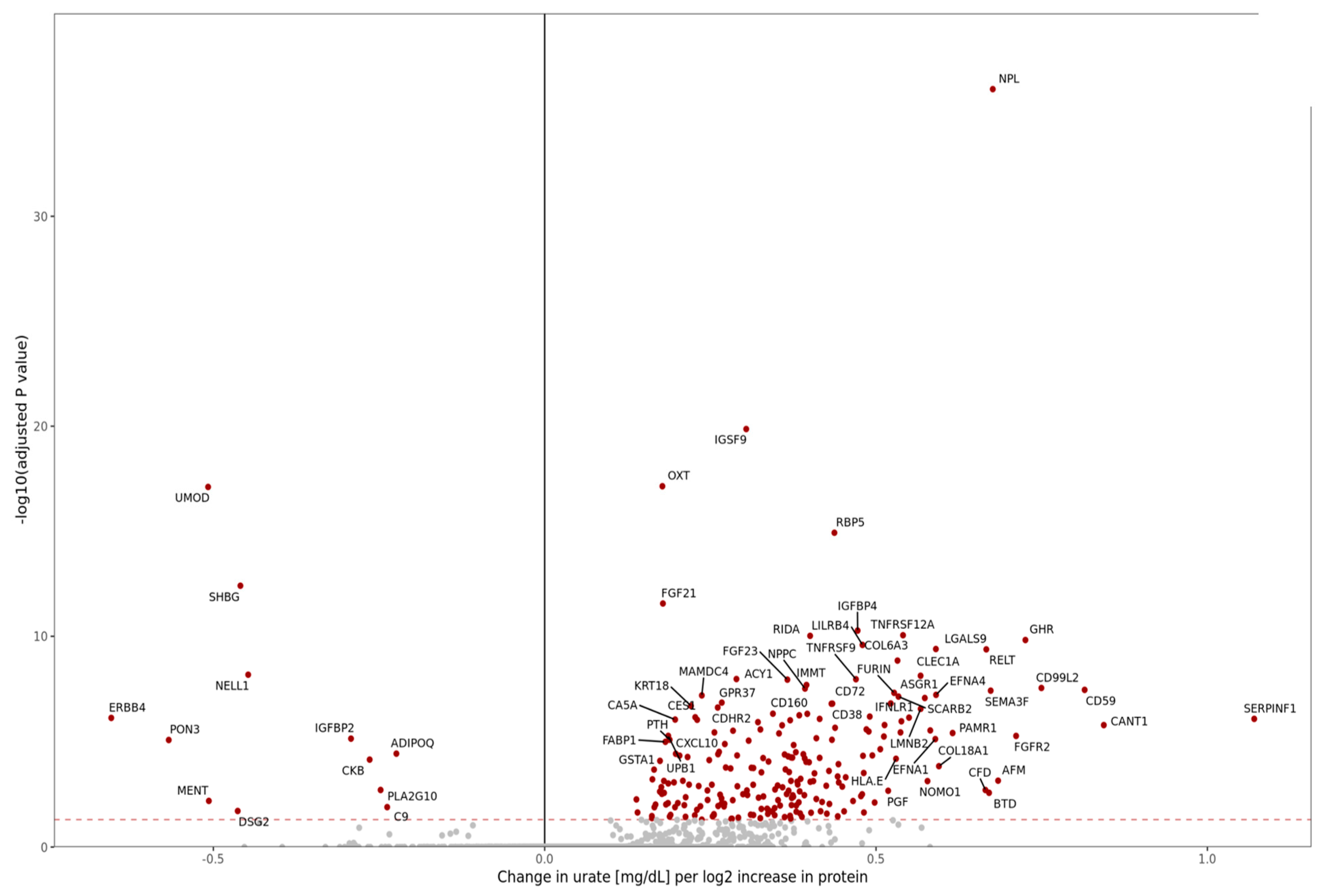

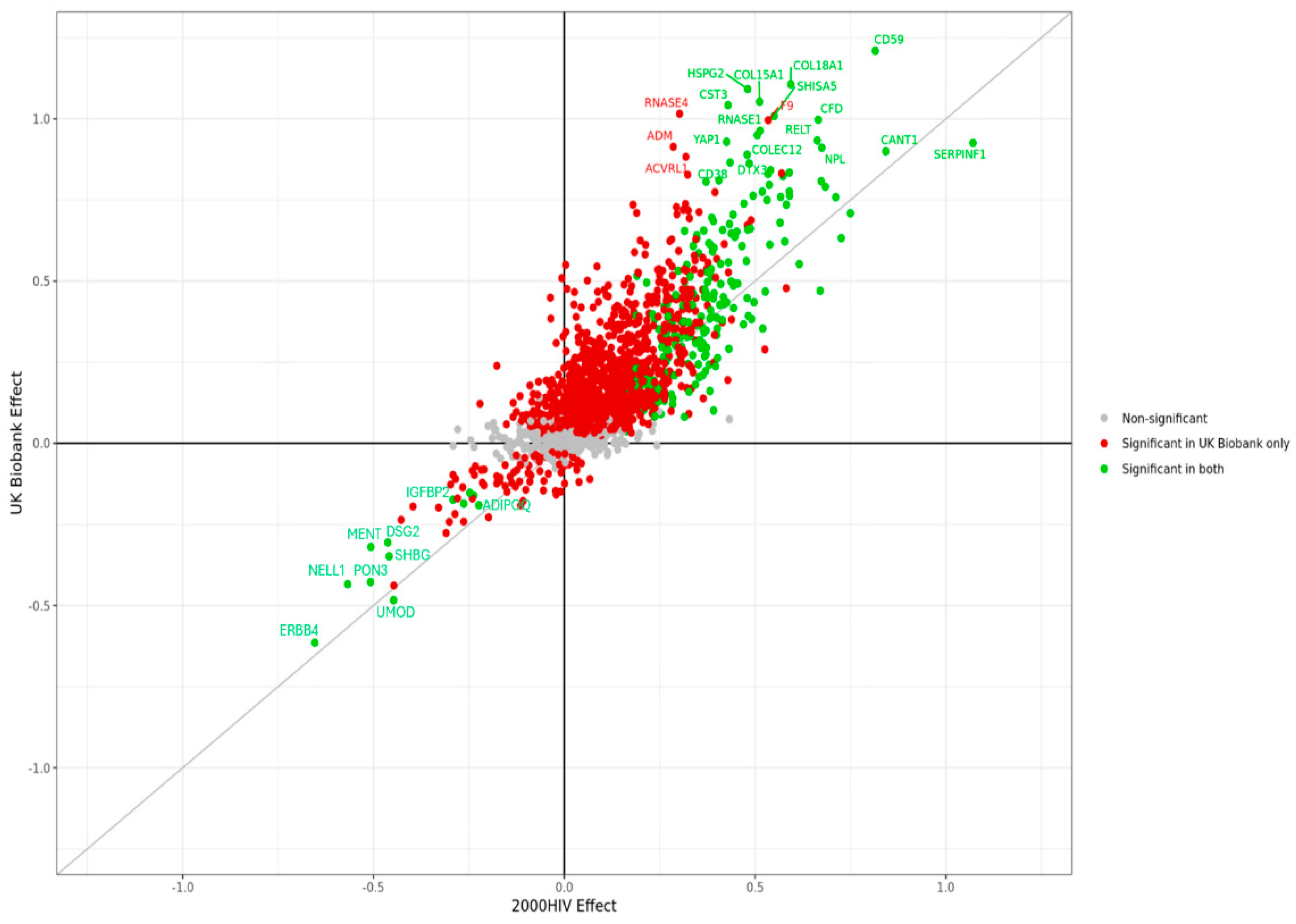

- Abstract: Background: People living with HIV (PLHIV) under viral remission following treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART) are exposed to persistent inflammation, which increases their susceptibility to non-AIDS comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease. Elevated urate concentrations, often associated with inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, may play a key role in exacerbating these conditions and contributing to chronic inflammatory profile. This study investigates the proteomic signature of hyperuricemia in virally suppressed PLHIV. Methods: We analyzed data from 1866 participants enrolled in the 2000HIV cohort, a Dutch multicenter, longitudinal study involving people living with HIV (PLHIV) who are virally suppressed and receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART). The analysis focused on a subset of 1404 individuals of White ethnicity. To account for sex imbalance and treatment-specific effects observed in the cohort, we applied a linear regression model adjusting for sex, body mass index (BMI), and treatment regimen. Rather than relying on categorical thresholds, serum urate concentrations were analyzed as a continuous variable. Biological samples were collected at study entry, with initial laboratory assessments followed by additional analyses of urate and creatinine levels in both plasma and urine. Proteomic profiling was conducted using the Olink® Explore platform, covering 2367 circulating proteins, which were compared between PLHIV with and without hyperuricemia (defined as serum urate ≥ 7 mg/dL). Results: We conducted a proteome-wide analysis of serum urate concentrations across 2367 proteins, identifying 233 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) using an adjusted p-value threshold of <0.05. Among the most positively associated proteins were N-acetylneuraminate pyruvate lyase (NPL), immunoglobulin superfamily member 9 (IGSF9), and oxytocin (OXT), while Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (ERBB4), paraoxonase 3 (PON3), and uromodulin (UMOD) showed the strongest negative associations (Figure 22). To replicate our findings, we applied a similar analytical model to the UK Biobank cohort, which has a substantially larger sample size. The increased statistical power resulted in a greater number of significant DEPs, supporting the robustness of our initial findings (Figure 23). To assess consistency, we compared effect estimates across cohorts in a scatter plot, yielding a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.7. This strong concordance reinforces the reproducibility and biological relevance of the observed protein–urate associations (Figure 24). Conclusion: This proteomics-based study reveals a distinct urate-related molecular profile in individuals living with HIV, implicating broader systemic pathways beyond traditional associations with gout. The identification of 233 urate-associated proteins and their replication in the UK Biobank (Spearman r = 0.7) underscores the strength and reliability of our findings. These results point to a potential role for urate in immune regulation and chronic inflammation. Although limited by a cross-sectional design and single time-point measurements, our findings offer a valuable foundation for future investigations into urate as a biomarker or therapeutic target in related inflammatory conditions.

19. Genetic Analysis of the Synergistic Cytokine Response of Monosodium Urate Crystals and Palmitate Identifies a New Role for the SFMBT1 Locus

- Nicholas A Sumpter 1,*, Riku Takei 2, Tony R Merriman 2, Mihai Netea 1, Tania O Crisan 3 and Leo A B Joosten 1,3

- 1

- Department of Internal Medicine, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 2

- Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA

- 3

- Department of Medical Genetics, Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- *

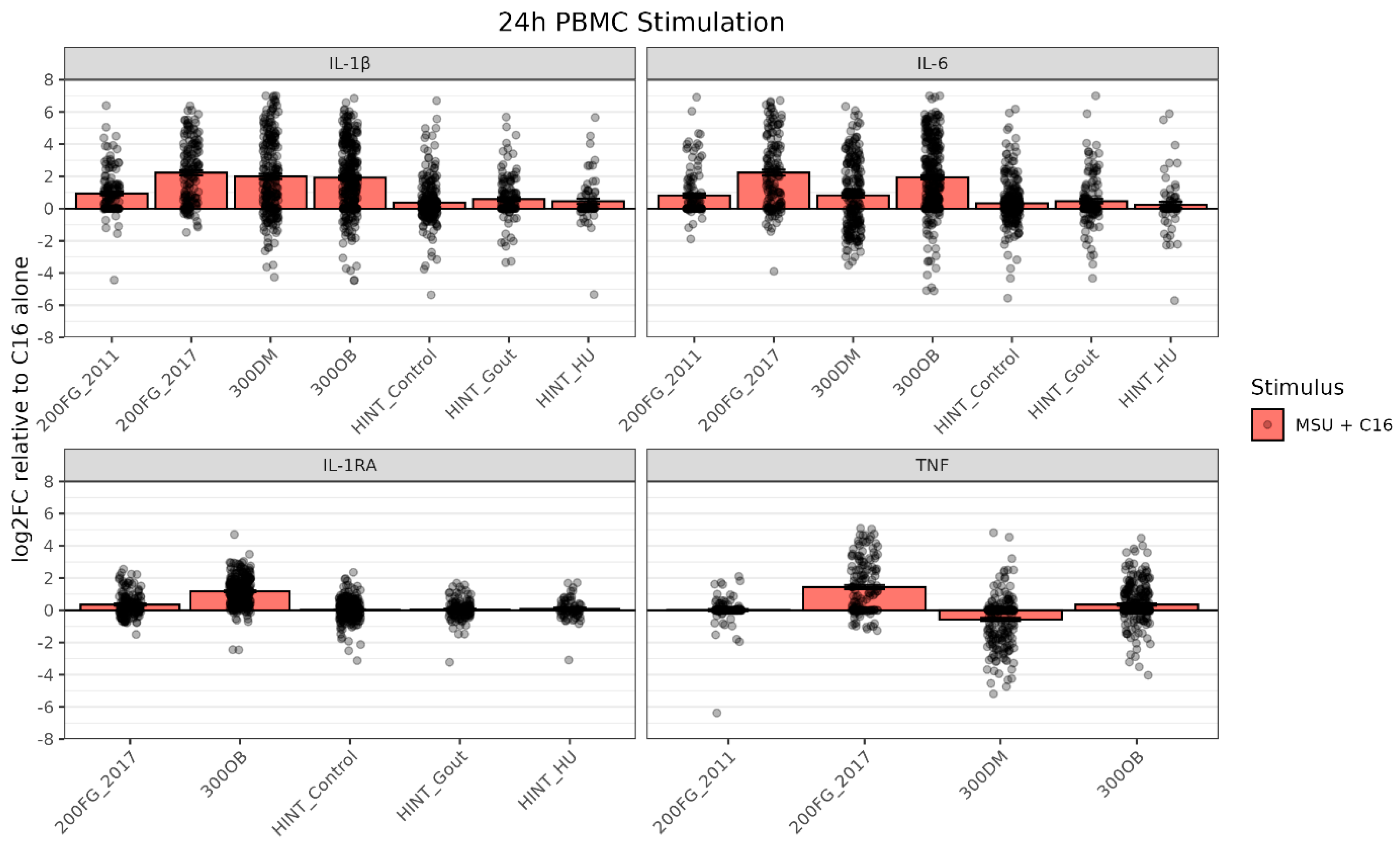

- Correspondence: nicholas.sumpter@radboudumc.nl