The Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Crystal-Induced Arthritis

Abstract

1. Why Perform Synovial Biopsy in Crystalline Arthritis Crystal-Induced Arthritis?

2. Why Perform Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy?

3. Overview of the Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy Procedure

4. Synovial Tissue Handling for Crystal Analysis

5. Tissue Analysis

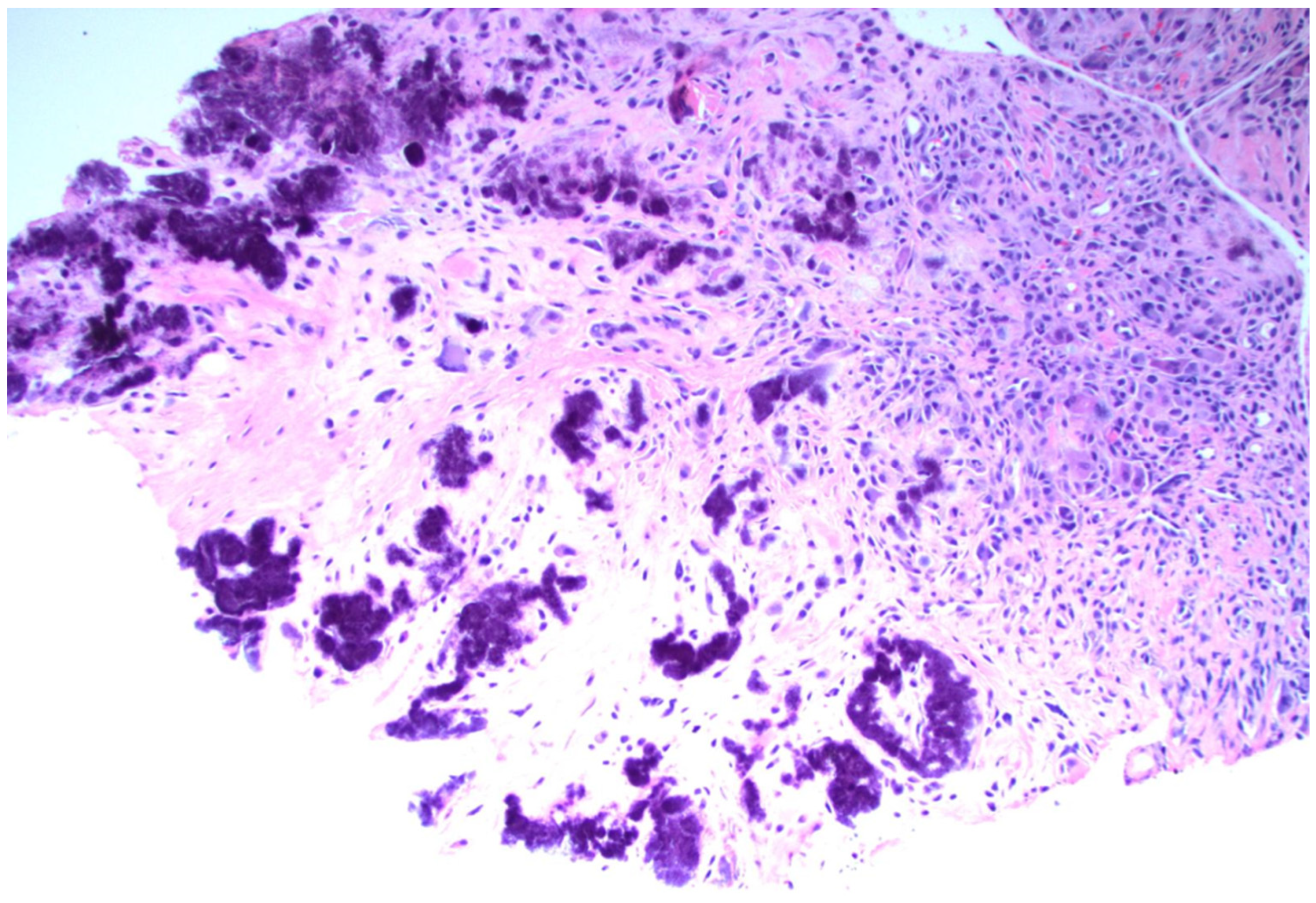

5.1. Disease-Specific Pathologic Findings—Gout

5.1.1. Crystals in Gout

5.1.2. Synovial Tissue Findings in Acute Gout

5.1.3. Synovial Tissue Findings in Chronic Gout

5.1.4. Tophaceous Deposits in Synovial Tissue

5.2. Disease-Specific Pathologic Findings—Calcium Pyrophosphate (CPPD)

5.2.1. Crystals in CPPD

5.2.2. Synovial Tissue Findings in CPPD

5.3. Disease-Specific Pathologic Findings—Basic Calcium Phosphate (BCP)/Hydroxyapatite

5.3.1. Crystals in BCP

5.3.2. Synovial Tissue Findings in BCP

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSU | Monosodium urate |

| CPPD | Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease |

| UGSB | Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| BCP | Basic calcium phosphate |

References

- Lumbreras, B.; Pascual, E.; Frasquet, J.; González-Salinas, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Hernández-Aguado, I. Analysis for crystals in synovial fluid: Training of the analysts results in high consistency. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.; Swan, A.; Dieppe, P. Detection of crystals in synovial fluids by light microscopy: Sensitivity and reliability. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1989, 48, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wallace, S.L.; Robinson, H.; Masi, A.T.; Decker, J.L.; McCarty, D.J.; Yü, T.F. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977, 20, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neogi, T.; Jansen, T.L.; Dalbeth, N.; Fransen, J.; Schumacher, H.R.; Berendsen, D.; Brown, M.; Choi, H.; Edwards, N.L.; Janssens, H.J.E.M.; et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, A.; Tedeschi, S.K.; Pascart, T.; Latourte, A.; Dalbeth, N.; Neogi, T.; Fuller, A.; Rosenthal, A.; Becce, F.; Bardin, T.; et al. The 2023 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, H.R. Pathology of the synovial membrane in gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1975, 18, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippou, G.; Tacchini, D.; Adinolfi, A.; Bertoldi, I.; Picerno, V.; Toscano, C.; Carta, S.; Santoro, P.; Frediani, B.; Spina, D. Histology of the synovial membrane of patients affected by osteoarthritis and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease vs. osteoarthritis alone: A pilot study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 45, 538–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloway, S.; Tucker, B.S. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease in a knee with total joint replacement. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 22, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Bardin, T.; Barskova, V.; Guerne, P.A.; Jansen, T.L.; Leeb, B.F.; Perez-Ruiz, F.; Pimentao, J.; Punzi, L.; et al. European league against rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part I: Terminology and diagnosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slot, O.; Terslev, L. Ultrasound-guided dry-needle synovial tissue aspiration for diagnostic microscopy in gout patients presenting without synovial effusion or clinically detectable tophi. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 21, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, V.; Asirvatham, J.R.; McHugh, J.; Ike, R. Synovial biopsy in the diagnosis of crystal-associated arthropathies. JCR J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 26, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, V.C.; Polido-Pereira, J.; Barros, R.; Luis, R.; Vidal, B.; Vieira-Sousa, E.; Vitorino, E.; Humby, F.; Kelly, S.; Pitzalis, C.; et al. Efficacy, safety and sample quality of ultrasound-guided synovial needle biopsy in clinical practice and research: A prospective observational study. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 72, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitt, J.C.; Griffith, J.F.; Lai, F.M.; Hui, M.; Chiu, K.H.; Lee, R.K.; Ng, A.W.; Leung, J. Ultrasound-guided synovial Tru-cut biopsy: Indications, technique, and outcome in 111 cases. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffier, G.; Ferreyra, M.; Albert, J.D.; Stock, N.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A.; Perdriger, A.; Guggenbuhl, P. Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy improves diagnosis of septic arthritis in acute arthritis without enough analyzable synovial fluid: A retrospective analysis of 176 arthritis from a French rheumatology department. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ike, R.W.; Arnold, W.J.; Kalunian, K.C. Arthroscopy in rheumatology: Where have we been? Where might we go? Rheumatology 2021, 60, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.H.; Pearson, C.M. A simplified synovial biopsy needle. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 1963, 6, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroosh, S.G.; Ghatfan, A.; Farbod, A.; Meftah, E. Synovial biopsy for establishing a definite diagnosis in undifferentiated chronic knee monoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, M.; van de Groes, S.; Thurlings, R.M. Synovial Tissue Biopsy Collection by Rheumatologists: Ready for Clinical Implementation? Front. Med. 2019, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlag, D.M.; Tak, P.P. How to perform and analyse synovial biopsies. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulé, V.; Larédo, J.D.; Cywiner, C.; Bard, M.; Tubiana, J.M. Synovial membrane: Percutaneous biopsy. Radiology 1990, 177, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Artzi, A.; Horowitz, D.L.; Mandelin, A.M., II; Tabechian, D. Best practices for ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy in the United States. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 37, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.; Humby, F.; Filer, A.; Ng, N.; Di Cicco, M.; Hands, R.E.; Rocher, V.; Bombardieri, M.; D’Agostino, M.A.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy: A safe, well-tolerated and reliable technique for obtaining high-quality synovial tissue from both large and small joints in early arthritis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scire, C.A.; Epis, O.; Codullo, V.; Humby, F.; Morbini, P.; Manzo, A.; Caporali, R.; Pitzalis, C.; Montecucco, C. Immunohistological assessment of the synovial tissue in small joints in rheumatoid arthritis: Validation of a minimally invasive ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy procedure. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007, 9, R101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najm, A.; Orr, C.; Heymann, M.F.; Bart, G.; Veale, D.J.; Le Goff, B. Success rate and utility of ultrasound-guided synovial biopsies in clinical practice. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, S.A.; Humby, F.; Lindegaard, H.; Meric de Bellefon, L.; Durez, P.; Vieira-Sousa, E.; Teixeira, R.; Stoenoiu, M.; Werlinrud, J.; Rosmark, S.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes and safety in patients undergoing synovial biopsy: Comparison of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, ultrasound-guided portal and forceps and arthroscopic-guided synovial biopsy techniques in five centres across Europe. RMD Open 2018, 4, e000799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, J.X. Pathology of the synovium. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 114, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidham, V.; Shidham, G. Staining method to demonstrate urate crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, H.R.; Jimenez, S.A.; Gibson, T.; Pascual, E.; Traycof, R.; Dorwart, B.B.; Reginato, A.J. Acute gouty arthritis without urate crystals identified on initial examination of synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 1975, 18, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidham, V.; Chivukula, M.; Basir, Z.; Shidham, G. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis of pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod. Pathol. 2001, 14, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, R.L.; Schumacher, H.R.; Becker, M.A.; Ryan, L.M. (Eds.) Chapter 11: Radiographic Changes of Crystal-Induced Arthropathies. In Crystal-Induced Arthropathies: Gout, Pseudogout and Apatite-Associated Syndromes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Bély, M.; Apáthy, A. Crystal Deposits in Tissue of 64 Patients with Gout—A Comparative Study of Standard Stains and Histochemical Reactions with the Non-Staining Technique of Bély and Apáthy. EC Cardiol. 2022, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Najm, A.; Le Goff, B.; Orr, C.; Thurlings, R.; Cañete, J.D.; Humby, F.; Alivernini, S.; Manzo, A.; Just, S.A.; Romão, V.C.; et al. Standardisation of synovial biopsy analyses in rheumatic diseases: A consensus of the EULAR Synovitis and OMERACT Synovial Tissue Biopsy Groups. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañete, J.D.; Celis, R.; Noordenbos, T.; Moll, C.; Gómez-Puerta, J.A.; Pizcueta, P.; Palacin, A.; Tak, P.P.; Sanmartí, R.; Baeten, D. Distinct synovial immunopathology in Behçet disease and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraan, M.C.; Reece, R.J.; Smeets, T.J.; Veale, D.J.; Emery, P.; Tak, P.P. Comparison of synovial tissues from the knee joints and the small joints of rheumatoid arthritis patients: Implications for pathogenesis and evaluation of treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, H.R., Jr. Pathology of crystal deposition diseases. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1988, 14, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidham, V.B.; Galindo, L.M.; Gupta, D.; Jhala, N.; Shidham, G.B. Histology: Urate Crystals in Tissue: A Novel Staining Method for Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Sections. Lab. Med. 1998, 29, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, C.A.; Schumacher, H.R. The synovitis of acute gouty arthritis: A light and electron microscopic study. Hum. Pathol. 1973, 4, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towiwat, P.; Chhana, A.; Dalbeth, N. The anatomical pathology of gout: A systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, G.M.; Dunne, A. Calcium crystal deposition diseases—Beyond gout. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, C.E.; Crocker, P.R.; Brady, K.; Hasan, N.; Levison, D. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease: Morphological and micro-analytical features. Histopathology 1991, 19, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, A.; Rothfuss, S.; Clayburne, G.; Sieck, M.; Ralph, H.S., Jr. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition in synovium. Relationship to collagen fibers and chondrometaplasia. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 1993, 36, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.K.; Mattson, E.; Gohr, C.M.; Hirschmugl, C.J. Characterization of articular calcium-containing crystals by synchrotron FTIR. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2008, 16, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Niessink, T.; Jansen, T.L.; Coumans, F.A.; Welting, T.J.; Janssen, M.; Otto, C. An objective diagnosis of gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease with machine learning of Raman spectra acquired in a point-of-care setting. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halverson, P.B.; Garancis, J.C.; McCarty, D.J. Histopathological and ultrastructural studies of synovium in Milwaukee shoulder syndrome—A basic calcium phosphate crystal arthropathy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1984, 43, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Positive Aspects | Negative Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Landmark Guided | Does not require rheumatologist to have access to ultrasound or fluoroscopy | Lower yield compared to other methods |

| Increased risk of non-synovial tissue injury | ||

| Increased risk and lower yield in small joints and joints with less inflammation. | ||

| Fluoroscopically guided biopsy | Higher yield of synovial tissue as compared to landmark-guided biopsy | Radiation exposure |

| Increased cost and require investment in fluoroscopy system | ||

| Typically requires collaboration with radiology or orthopedics | ||

| Ultrasound-Guided Portal and Forceps | Higher yield of synovial tissue as compared to landmark-guided biopsy | Requires initial investment in autoclavable reusable equipment |

| Can obtain tissue from multiple angles within the joint space | Requires operator to be experienced in ultrasound and in synovial biopsy | |

| Ultrasound-Guided Guillotine Needle | Higher yield of synovial tissue as compared to landmark-guided biopsy | Requires operator to be experienced in ultrasound and in synovial biopsy Size of tissue sample is limited by size of guillotine needle Shape of the guillotine needle can limit access to certain areas of joint space |

| Ease of use of guillotine needle | ||

| Guillotine needle is disposable | ||

| Cost is more favorable than other methods of obtaining tissue |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal Associated Disease Network. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mandelin II, A.M.; Horowitz, D.L.; Tabechian, D.; Ben-Artzi, A. The Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Crystal-Induced Arthritis. Gout Urate Cryst. Depos. Dis. 2026, 4, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/gucdd4010002

Mandelin II AM, Horowitz DL, Tabechian D, Ben-Artzi A. The Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Crystal-Induced Arthritis. Gout, Urate, and Crystal Deposition Disease. 2026; 4(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/gucdd4010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandelin II, Arthur M., Diane Lewis Horowitz, Darren Tabechian, and Ami Ben-Artzi. 2026. "The Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Crystal-Induced Arthritis" Gout, Urate, and Crystal Deposition Disease 4, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/gucdd4010002

APA StyleMandelin II, A. M., Horowitz, D. L., Tabechian, D., & Ben-Artzi, A. (2026). The Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Crystal-Induced Arthritis. Gout, Urate, and Crystal Deposition Disease, 4(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/gucdd4010002