Abstract

Spectroscopic techniques have emerged as crucial tools in the field of malaria research, offering immense potential for improved diagnosis and enhanced understanding of the disease. This review article pays tribute to the pioneering contributions of Professor Henry Mantsch in the realm of clinical biospectroscopy, by comprehensively exploring the diverse applications of spectroscopic methods in malaria research. From the identification of reliable biomarkers to the development of innovative diagnostic approaches, spectroscopic techniques spanning the ultraviolet to far-infrared regions have played a pivotal role in advancing our knowledge of malaria. This review will highlight the multifaceted ways in which spectroscopy has contributed to the field, with a particular emphasis on its impact on diagnostic advancements and drug research. By leveraging the minimally invasive and highly accurate nature of spectroscopic techniques, researchers have made significant strides in improving the detection and monitoring of malaria parasites. These advancements hold the promise of enhancing patient outcomes and aiding in the global efforts towards the eradication of this devastating disease.

Keywords:

malaria; hemozoin; spectroscopy; infrared; Raman spectroscopy; near-infrared; SERS; TERS; UV/Visible; photoacoustic; AFM-IR; antimalarial 1. Introduction

Malaria remains a formidable global health challenge, with an estimated 249 million cases in 2022, a 55% increase from pre-COVID-19 levels [1]. To effectively combat this disease, there is a critical need for affordable and highly sensitive diagnostic tests that can identify asymptomatic carriers [2]. Nucleic acid amplification tests, such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays, are highly sensitive methods for detecting low-density malaria infections. However, their use is limited to well-equipped laboratory settings due to their complexity [2].

In response to the need for more accessible diagnostic tools, ultrasensitive Rapid Diagnostic Tests (uRDTs) have been developed. These tests, which detect proteins like Histidine-Rich Protein 2 (HRP2), have shown promise in laboratory conditions, following the same principles as conventional Rapid Diagnostic Tests (cRDTs) [3]. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these uRDTs are still lower compared to the gold standard PCR assays. In a recent meta-analysis, the Alere™ Ultra-sensitive Malaria Ag P. falciparum RDT had a sensitivity of 72.1% for symptomatic patients, higher than the 67.4% sensitivity reported for cRDTs in the same field conditions [3]. Yet, these values remain well below the 95% sensitivity achieved by PCR assays [3].

To strengthen the fight against malaria, continued research and development are critical. Improving the performance of malaria diagnostic tests is essential, bringing them closer to the accuracy of laboratory-based molecular tests while maintaining the affordability and portability that are crucial for widespread deployment, especially in resource-limited settings. In this context, spectroscopic approaches offer a viable alternative as point-of-care tests in remote villages and resource-poor clinical settings. These spectroscopic techniques can also play a role in developing new drugs and understanding the mechanisms of drug interaction, along with monitoring the therapeutic effects of drugs by quantifying parasitemia—a capability currently lacking in Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs). By enhancing the accuracy, affordability, and accessibility of malaria diagnostics, we can bolster the tools available to combat this devastating disease, particularly in the most vulnerable communities.

The use of spectroscopic techniques for disease diagnosis was eloquently summarized by Professor Henry Mantsch, who stated that “changes in tissue biochemistry must precede any morphological or symptomatic manifestations, thus allowing spectroscopic diagnosis at an earlier stage of the disease” [4]. This principle has been instrumental in the fight against malaria, where spectroscopic methods have provided a minimally invasive and accurate approach to detecting and monitoring the disease. These diagnostic tools span a range of spectroscopic modalities, including Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), near-infrared (NIR), Raman, surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) tip enhanced Raman scattering (TERS), atomic force microscopy–infrared (AFM-IR), ultraviolet/visible (UV/Vis) and photoacoustic spectroscopy.

Infrared spectroscopy has shown great promise in malaria diagnosis, as it can detect specific biomarkers associated with Plasmodium-infected red blood cells. These biomarkers include lipids, proteins, and hemozoin, a by-product of the malaria parasite’s hemoglobin digestion. Raman spectroscopic approaches have relied on detecting hemozoin but other markers including proteins and lipids can also be detected using Raman spectroscopy. Near-infrared spectroscopy, on the other hand, leverages the unique optical properties of hemozoin and lipids to differentiate between infected and uninfected red blood cells using the overtone and combination bands of these biomarkers. UV/Visible spectroscopy has been employed to detect changes in the optical absorption spectra of blood samples, which can be correlated with the presence and density of malaria parasites.

The advantages of spectroscopic approaches for malaria diagnosis are numerous. These techniques are minimally invasive, requiring only a small blood sample, and can provide rapid, objective results without the need for skilled personnel. Moreover, they have the potential to detect asymptomatic infections, which are crucial for interrupting disease transmission. Importantly, spectroscopic methods can also quantify parasitemia levels, enabling healthcare providers to monitor the efficacy of antimalarial drug treatments. The field of spectroscopy-based malaria diagnostics has seen remarkable advancements with the development of miniaturized chip-based spectrometers [5,6]. These compact devices integrate multiple spectroscopic functions onto a single electronic chip, enabling greater affordability and portability compared to traditional bulky spectrometers. The integration of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology has been pivotal in realizing this compact and versatile design, allowing for the seamless incorporation of spectroscopic capabilities into smaller, more accessible platforms. This technological progress has significantly expanded the applications of clinical spectroscopy, empowering healthcare professionals and researchers with powerful analytical tools that can be readily deployed in various clinical settings.

While spectroscopic techniques have shown promising results in laboratory settings, their translation to the clinic and point-of-care settings is not without limitations. Factors such as sample preparation, environmental interference, and variations in individual physiology can affect the accuracy and reliability of these methods. Addressing these challenges through continued research and development is essential for a broader adoption of spectroscopic approaches in the field. This review will provide an overview of the application of optical spectroscopy techniques in the diagnosis and research of malaria. The review will highlight the key spectroscopic biomarkers that have been identified for the detection of malaria infection before delineating the diverse range of spectroscopic methods that have been utilized in malaria research, including FTIR, Raman, SERS, NIR, AFM/IR, photothermal imaging, TERS photoacoustic and UV/Vis spectroscopy. For each technique, the review will discuss how spectroscopic signatures have contributed to advancing our understanding of malaria, from disease diagnosis to investigating drug interactions and mechanisms of action. Additionally, the review will address the barriers that have hindered the translation of these spectroscopic approaches from the research lab to clinical practice. Finally, the review will speculate on future applications and potential of optical spectroscopy in advancing malaria research and improving disease management. Overall, this review aims to provide a comprehensive survey of the role optical spectroscopy has played, and continues to play, in the fight against the global health challenge of malaria.

2. Life Cycle of the Parasite

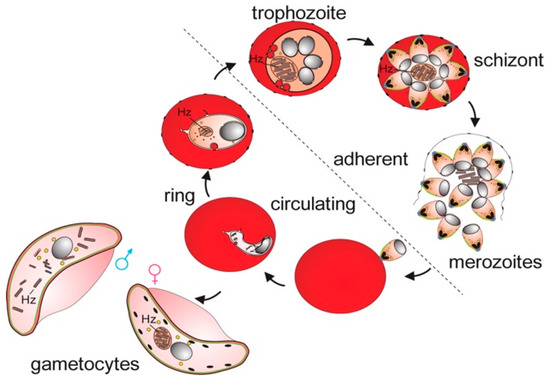

The life cycle of the malaria parasite involves both a sexual and an asexual phase (Figure 1). Most current diagnostic techniques have focused on detecting markers of the erythrocytic (red blood cell) stage of the parasite’s life cycle in peripheral blood. However, the future may see the exploration of alternative, non-invasive sample types such as saliva, breath, urine, and stool as potential targets for malaria diagnosis. These non-blood-based approaches could detect markers of infection without the need to identify circulating parasites in the peripheral blood.

Figure 1.

Asexual and sexual phases of the malaria parasite in RBC. After sporozoites enter the bloodstream, they travel to the liver, where they invade hepatocytes and develop into schizonts, each containing thousands of merozoites. These merozoites are then released and invade erythrocytes, initiating the intraerythrocytic asexual phase. During this phase, the parasites grow and divide within the food vacuole, progressing through three distinct morphological stages: ring, trophozoite, and schizont. When schizonts rupture, they release merozoites, continuing the erythrocytic cycle. Some merozoites, instead of replicating, differentiate into male and female gametocytes capable of transmission to mosquitoes. The digestion of hemoglobin by the parasite leads to the accumulation of Hz. In the circulation, only ring-stage parasites and late-stage gametocytes are observed. Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry [7].

3. Spectral Biomarkers for Malaria

The malaria parasite, Plasmodium, produces distinct biochemical signatures during its complex life cycle within human hosts that serve as valuable diagnostic and therapeutic targets. Among these biomarkers, hemozoin, a crystalline byproduct of hemoglobin digestion, has emerged as a unique indicator of infection due to its specific magnetic and spectroscopic properties. The parasite also exhibits characteristic changes in lipid metabolism, producing unique lipid profiles that differ significantly from those of healthy cells. Additionally, specific nucleic acid sequences and protein expressions unique to Plasmodium provide molecular fingerprints of infection, while also offering insights into drug resistance and disease progression. Understanding these biomarkers not only advances our knowledge of parasite biology but also enables the development of more sensitive and specific diagnostic tools.

3.1. Hemozoin

3.1.1. Discovery of Hemozoin and Malaria Infection

Hemozoin, also known as malaria pigment, is a dark brown/black molecule that results from the catabolization of hemoglobin by the malaria parasite. For a detailed review of the molecular analysis of hemozoin, the reader is referred to a recent in-depth review by Rathi et al. [8] that comprehensively examines the structure, function, and biosynthesis of this important malaria pigment. Johann Friedrich Meckel, a German pathologist, made early observations of the malaria pigment in 1847. He noticed this dark pigment in the organs of individuals who had died of pernicious fever, often found in the spleen, liver, brain, or kidneys on autopsy. Meckel associated this pigment accumulation with the presence of malaria in the blood [9]. In 1871, Meckel’s observations were later confirmed by two scientists—Rudolf Virchow in Germany and Maxime Cornu in France. However, their findings were not widely recognized at the time as they were unpublished [9]. In 1879, Philipp Friedrich Hermann Klencke, a German scientist, was also recognized for his early observations of the malaria parasite [10]. However, due to the lack of publication and differences in his drawings compared to later photomicrographs, his contributions were not widely acknowledged [9]. The ground-breaking discovery of the malaria parasite is credited to Alphonse Lavéran in 1880 [11]. Lavéran’s understanding of the significance of his discovery and its potential impact on the treatment and transmission of malaria earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907. While there was some debate over the priority of the discovery, Lavéran’s work is considered the most significant in understanding and identifying the malaria parasite [9].

3.1.2. Organisms Producing Hemozoin

Human malaria parasites, including P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi, all produce hemozoin during their life cycles. Hemozoin formation has also been documented in the New World monkey malaria parasite P. brasilianum, the rodent malaria parasite P. yoelii, and the avian malaria parasite P. gallinaceum [12]. Beyond the Plasmodium genus, hemozoin has been identified in another protozoan parasite that infects birds, Hemoproteus columbae. Interestingly, the unrelated human parasitic worms Schistosoma mansoni [13] and Echinostoma trivolvis also dispose of heme through hemozoin production, though E. trivolvis only forms the pigment when residing in its intermediate snail host. Even insects, such as kissing bugs of the genus Rhodnius, excrete excess heme as hemozoin in their feces [12]. So, while hemozoin is closely associated with and vital to the lifecycle of the malaria parasite, trace amounts may occasionally be detected in a few other severe infectious or hematological conditions, though it remains a uniquely defining feature of Plasmodium infections.

3.1.3. Hemozoin Location in Humans

For P. falciparum infection, infected red blood cells (RBCs) containing trophozoites and schizonts are often absent from the peripheral circulation, especially at low levels of infection [14]. However, at high levels of infection, trophozoites have been reported in peripheral blood [15]. The low number of schizonts and trophozoites in peripheral blood is due to a process called sequestration, where the infected RBCs adhere to the endothelium of blood vessels, particularly in the venules [14]. The infected RBCs develop electron-dense structures on their membrane, known as knobs, which facilitate their attachment to the venular endothelium. By sequestering in the vasculature, the mature parasites (trophozoites and schizonts) can evade destruction in the spleen. Importantly, the sequestered parasites can continue to release new merozoites, which can then invade uninfected RBCs, thereby perpetuating the asexual cycle of the parasite [14]. This sequestration of P. falciparum-infected RBCs in the vasculature presents a potential opportunity for non-invasive diagnostic approaches. The stationary, sequestered cells containing hemozoin-rich trophozoites and schizonts could serve as targets for spectroscopic detection, such as NIR or Raman spectroscopy. Late-stage rings and mature stage IV–V gametocytes, which are found in peripheral blood, do contain hemozoin [16]. The female gametocyte is characterized by a centralized accumulation of the hemozoin pigment. The hemozoin granules are condensed and localized within the center of the female gametocyte. In contrast, the hemozoin pigment in the male gametocyte is dispersed throughout the infected red blood cell rather than being concentrated in the center [16]. Hemozoin is also found in leukocytes, including neutrophils [15,17] and monocytes [17]. While schizonts and trophozoites are not common in peripheral blood, other cell types including late-stage rings, gametocytes, and leukocytes still make hemozoin an attractive marker for spectroscopy-based diagnosis.

3.1.4. Crystal Structure

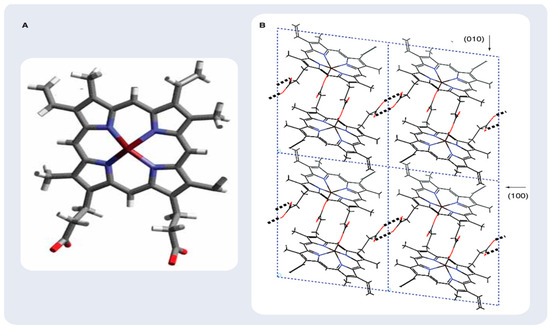

Hemozoin is a crystalline pigment that has a well-characterized molecular and crystal structure. At the molecular level, hemozoin is a dimer of heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX) molecules, where each heme molecule consists of a central ferric (Fe3+) iron atom coordinated to a porphyrin ring and various side chains. Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence powder diffraction data indicated that the heme molecules are linked together through a reciprocal coordination bond between the central iron atom of one heme and a carboxylate group of the propionate side chain of the adjacent heme [18]. The Fe–O bond distance converged to a value of 1.886(2) Å, which was found to be consistent with other high-spin ferric porphyrins [18]. These hemozoin dimers then crystallize into a unique monoclinic crystal structure, with the heme dimers arranged in stacks and held together through hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking interactions between the porphyrin rings, as well as Van der Waals interactions between the alkyl side chains (Figure 2). The resulting hemozoin crystals typically range in size from 0.2 to 1.0 μm in length and exhibit a characteristic needle-like or rod-shaped morphology with a hexagonal cross-section. This unique crystal structure allows the malaria parasite to sequester the potentially toxic heme molecules, preventing them from causing oxidative damage to the parasite’s cellular components, and the presence of hemozoin crystals in the blood of infected individuals serves as a diagnostic marker for malaria.

Figure 2.

Hematin and β-hematin structure. (A) Schematic representation of hematin, the monomeric precursor of β-hematin. (B) Structure and packing arrangement of β-hematin (synthetic malaria pigment) viewed along the c-axis. Some (h,k,l) planes are indicated. Reprinted with permission from the American Chemical Society [19].

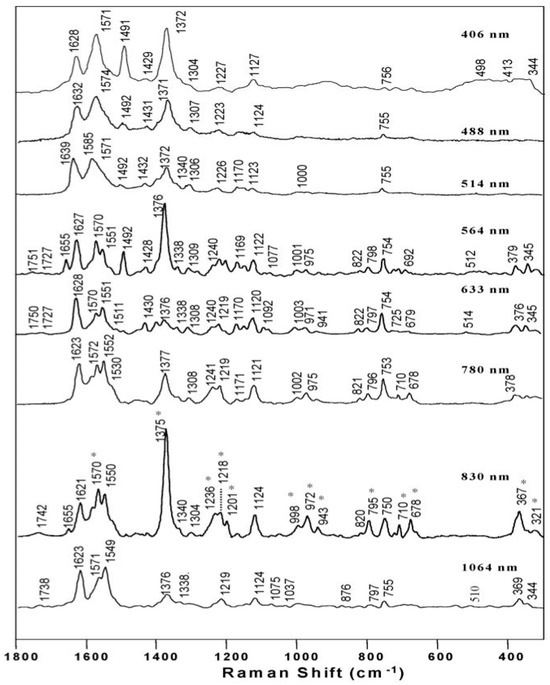

3.1.5. Raman Spectroscopy of Hemozoin

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful tool for the analysis of hemozoin, as it can provide detailed information about the molecular structure and vibrational modes of this important biomolecule. When analyzing hemozoin using Raman spectroscopy, several distinct and characteristic bands are observed in the spectrum. Excitation of hemozoin with a laser wavelength in the Soret band region (e.g., 406 nm) results in a significant enhancement of the Raman signal, a phenomenon known as type-A resonance Raman scattering (or Frank–Condon scattering), due to the π→π* electronic transitions of the porphyrin [20], which is in resonance with the excitation wavelength, allowing for the detection of very low concentrations of hemozoin and making it a highly sensitive technique for the identification and quantification of this biomolecule. The Raman bands observed in this region are primarily associated with the porphyrin ring vibrations, such as the intense ν4 mode at around 1375 cm−1, which corresponds to the C-N stretching of the porphyrin macrocycle. Excitation of hemozoin in the near-infrared region, such as with a 785 or 830 nm laser, also results in enhanced Raman scattering, attributed to the presence of the central iron atom in the heme group, which can undergo charge transfer transitions with the porphyrin macrocycle in this wavelength range. Dramatic enhancement of certain Raman modes when irradiating β-hematin and hemin (the precursor to hemozoin) with 780 nm and 830 nm laser excitation wavelengths is observed (Figure 3). Specifically, the A1g modes at 1570, 1371, 795, 677, and 3 cm−1, the ring breathing modes in the 850–650 cm−1 range, and the out-of-plane modes including iron ligand modes in the 400–200 cm−1 range were significantly enhanced. This enhancement was more pronounced in beta-hematin compared to hemin. The absorbance spectra recorded during the transformation of hemin to beta-hematin showed a red shift of the Soret and Q (0–1) bands, which has been interpreted as resulting from excitonic coupling due to porphyrin aggregation. Additionally, a small broad electronic transition observed at 867 nm was assigned to a z-polarized charge transfer transition dxz → eg(π*).

Figure 3.

Raman excitation wavelength measurements recorded of β-hematin. The asterisks (*) highlight the bands enhanced relative to the other excitation wavelengths at 830 nm. Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society [20].

The extraordinary band enhancement observed when exciting beta-hematin with near-infrared wavelengths, compared to hemin, can be explained by the theory of aggregate-enhanced Raman scattering. This occurs due to intermolecular excitonic interactions between the porphyrinic units, leading to a superposition of electronic transitions that result in enhanced Raman scattering. Hemozoin pigment, like other haem pigments, produces intense overtone tones when excited with green laser light [21]. Enhancement with the 514.5 and 532 nm excitation laser lines, which are in close proximity to the vibronic Qv band of the visible spectrum of hemoporphyrins, enables the C–Term enhancement mechanism to dominate, which occurs between forbidden electronic transitions which are prohibited at the equilibrium geometry of the molecule [21]. The enhanced Raman scattering observed in both the Soret band and near-infrared regions is a characteristic feature of hemozoin and allows for its sensitive and selective detection in complex biological samples, such as those obtained from malaria-infected individuals, making Raman spectroscopy a valuable technique for the diagnosis and study of malaria.

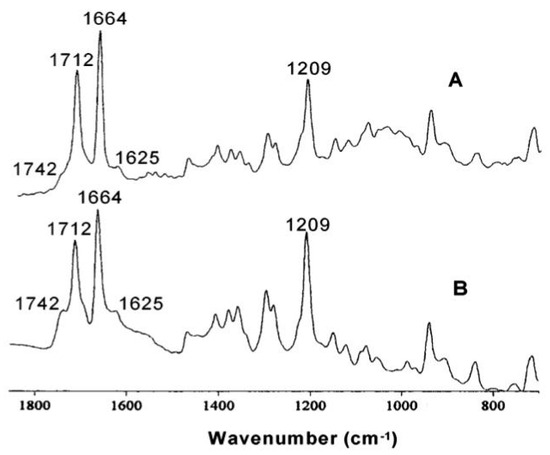

3.1.6. FTIR Spectroscopy of Hemozoin

The FTIR spectra of β-hematin and hemozoin are shown in Figure 4. Slater et al. [22,23] were the first to report the infrared (IR) spectrum of hemozoin and β-hematin. They identified two distinct absorption bands in the hemozoin spectrum at 1664 cm−1 and 1211 cm−1, which were absent in the spectra of free heme (hematin) and heme complexes (hemin). By comparing the hemozoin spectrum to other iron-carboxylate-containing compounds, Slater et al. [23] proposed that the heme units in hemozoin are coordinated in a unidentate fashion, where one of the carboxylate C-O bonds exhibits double-bond character, resulting in a C=O stretching vibration between 1700 and 1600 cm−1. The strong absorption at 1211 cm−1 was also attributed to the C-O stretching of an axial carboxylate ligand, based on studies of metalloporphyrin compounds with O-methyl groups, which showed similar C-O stretching bands in the 1270–1080 cm−1 region [23]. These distinct spectroscopic signatures of hemozoin, compared to the heme precursors, provided a valuable IR-based marker that could potentially be exploited for the development of diagnostic tools for malaria infection. The unique IR absorption features highlighted the structural differences between the crystalline hemozoin and the soluble heme species, which have important implications for understanding the biochemistry of malaria parasites.

Figure 4.

(A) FTIR spectrum of β-hematin. (B) FTIR spectrum of hemozoin extracted from malaria trophozoites. Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society [20].

3.1.7. UV/Visible Spectroscopy of Hemozoin

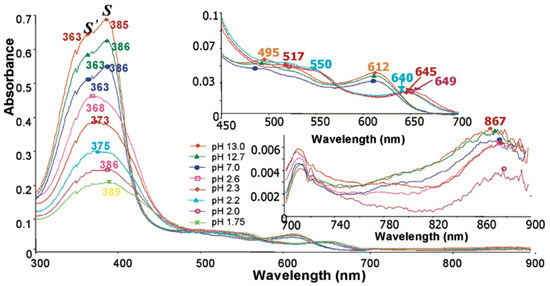

Hemin exhibits a distinct Soret band (or B band) that is resolved into two bands at 363 nm (S′) and 385 nm (S), along with Q bands at 495 nm, 521 nm, 550 nm (very weak), and 612 nm. In contrast, the Soret band of β-hematin collapses into a single broad band centered at 389 nm, along with a Q band at 649 nm, when observed at low pH. This distinction helps to discriminate β-hematin from hematin and hemin. Other bands observed in the absorbance spectrum of β-hematin include bands at 513 nm and 550 nm [20]. The absorbance spectrum of β-hematin at low pH exhibits characteristics consistent with those reported by Bohle et al. [24] Their study, using a potassium bromide pellet technique, revealed distinct spectral bands at 406 nm, 510 nm, 538 nm, and 644 nm [24]. These findings align closely with our observed spectrum, providing corroborative evidence for the spectral properties of β-hematin under acidic conditions [20]. They also reported a band at 580 nm that is not observed in the solution spectra reported here [24]. The 649 nm band is characteristic of hemin aggregates, as determined by micro-spectrophotometry [25] and photoacoustic spectroscopy [26]. This band sequentially shifts (640 nm, 645 nm, 649 nm) as the pH decreases. Figure 5 shows representative spectra of the conversion of hemin to β-hematin. The decrease in pH causes broadening and reduced intensity of the Soret band in β-hematin, attributed to aggregation and precipitation. An apparent red shift occurs from 363 nm to 389 nm, though accurate maxima determination is difficult due to the broad nature of the band at low pH. Red shifts in both Soret and Q-bands indicate excitonic coupling from porphyrin aggregation. Interestingly, a small, broad band centered around 867 nm is observed in both hemin and β-hematin [20]. This band slightly red-shifts as the reaction progresses and appears less intense in β-hematin compared to hemin, likely due to β-hematin precipitation. This previously unreported band is tentatively assigned to a charge transfer (CT) transition, specifically band I (dxz → eg(π*)) [20]. These spectral changes provide insight into the formation and characteristics of β-hematin, offering valuable information about the molecular processes involved in its synthesis and structure.

Figure 5.

Absorbance spectra recorded during the acidification of hemin to form β-hematin. Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society [20].

3.1.8. NIR Spectroscopy of Hemozoin

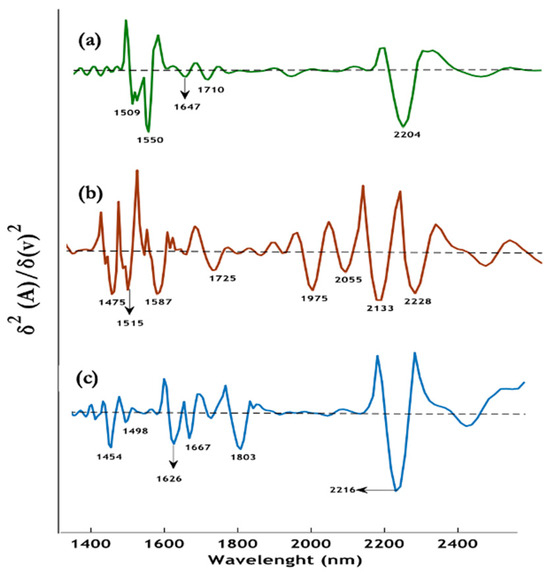

The near-infrared (NIR) spectra of the hemozoin standard purchased from Invivogen and hemozoin extracted from infected red blood cells, along with synthetic β-hematin, are presented in Figure 6a–c. The spectra do not show much consistency, indicating a lot of impurities. Notably, the spectrum of hemozoin isolated from infected red blood cells (Figure 6b) exhibits slight differences in the 1960 nm–2500 nm region compared to the hemozoin purchased from Invivogen. Specifically, four intense bands are observed at 1975 nm, 2055 nm, 2133 nm, and 2228 nm in the extracted hemozoin, whereas the synthetic β-hematin (Figure 6c) shows a single intense peak at 2216 nm [5]. These additional bands in the extracted hemozoin sample are tentatively assigned to ν(CH3/CH2) vibrations, possibly originating from residual hemoglobin left behind during the isolation process. The experimental NIR wavelength values are based on the second derivative spectra, providing enhanced spectral resolution and allowing for the identification of these subtle differences between the natural and synthetic forms of the pigment possibly resulting from impurities [5].

Figure 6.

Representative second derivative spectra, (a) β-hematin (green), (b) dry hemozoin isolated from infected red blood cells (red), (c) dry crystalline hemozoin purchased from Invivogen (blue). Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society [5].

3.2. Lipids

The role of lipids in the formation of hemozoin, a by-product of the malaria parasite’s digestion of host hemoglobin, has been the subject of investigation. Bendrat et al. [27] suggested that this process is mediated by lipids, as they observed that an acetonitrile extract of P. falciparum promoted the formation of beta-hematin, a synthetic analog of hemozoin. Further evidence supporting the involvement of lipids in hemozoin formation comes from the dramatic increase in lipid content within P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes [28,29,30,31] and observations of hemozoin localization in close proximity to neutral lipid bodies (NLBs) [30,32]. Specifically, the parasites synthesize and package triacylglycerol (TAG) and diacylglycerol (DAG) into NLBs in a stage-specific manner within the digestive vacuole (DV) [30,33,34]. These lipids are barely detectable in uninfected erythrocytes [28,35]. However, the precise function of NLBs during parasite growth remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that NLBs may serve as a depot of lipid intermediates generated during the digestion of phospholipids [33] or, alternatively, as a source of lipids that can be mobilized to supply the growing parasite with fatty acids and acylglycerols for membrane generation [34]. Importantly, the specific composition of the P. falciparum NLB lipid blend, identified by mass spectrometry, has been shown to be sufficient for mediating hemozoin formation [32]. This lipid blend consists of a 4:2:1:1:1 ratio of the monoglycerides monostearoylglycerol (MSG) and monopalmitoylglycerol (MPG), and the diglycerides 1,3-dioleoylglycerol (DOG), 1,3-dipalmitoylglycerol (DPG), and 1,3-dilinoleoylglycerol (DLG) [32]. Research has revealed some fascinating insights into the formation of β-hematin in the presence of lipids. Egan et al. [36] discovered that β-hematin can rapidly form under conditions that closely mimic the physiological environment, particularly in the presence of interfaces between octanol/water, pentanol/water, and lipid/water. Molecular dynamics simulations have provided further elucidation of this process. These simulations have shown that a precursor to the hemozoin dimer can spontaneously form in the absence of the competing hydrogen bonds that are typically present in water. This suggests that beta-hematin likely self-assembles near a lipid/water interface within the living organism (in vivo), as confirmed by Raman spectroscopy [36].

The ability of β-hematin to form so readily under these realistic conditions is a significant finding. It sheds light on the mechanisms underlying the production of this important biological substance and highlights the importance of examining these processes in the context of relevant interfaces and environmental factors. Further research in this direction could yield valuable insights into the physiological relevance and potential applications of β-hematin.

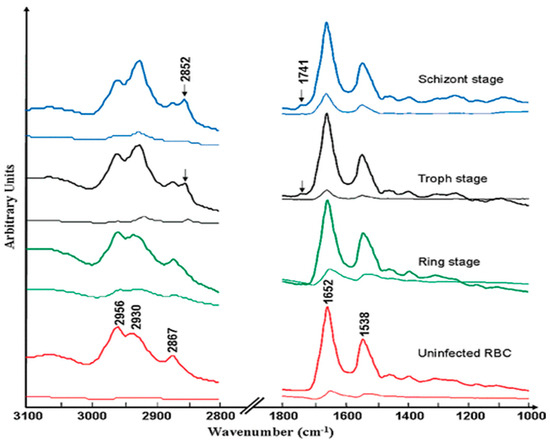

FTIR synchrotron spectra recorded of single cells from the different phases of the erythrocytic life cycle show the continuous increase in lipid components as the cells progress from being uninfected to the ring, schizont, and trophozoite stages [31]. Figure 7 shows synchrotron FTIR spectra of single uninfected red blood cells compared with ring, trophozoite, and schizont stages cells. The ester carbonyl band from triglyceride fatty acids at 1742 cm−1 increases through the different stages and is barely discernible in uninfected cells. Bands at 2922 cm−1 and 2852 cm−1, assigned to the νasym(CH2 acyl chain lipids) and νsym(CH2 acyl chain lipids), respectively, increase as the parasite matures from its early ring stage to the trophozoite and finally to the schizont stage [15]. The principal component analysis (PCA) enabled discrimination between uninfected, ring, trophozoite and schizont stages on a PC1 versus PC2 Scores plot [31]. Raman spectroscopy was employed to differentiate between P. falciparum and P. vivax on a PCA 2D scores plot. The PCA performed in the CH stretching region 3100–2800 cm−1 showed a clear clustering of the two species, indicating that the lipidomic component can be used to distinguish species of sp. using Raman spectroscopy. This finding is crucial for informing appropriate drug treatment strategies against different species [37].

Figure 7.

FTIR averaged normalized spectra of the C-H stretching region and fingerprint region from the Australian Synchrotron of RBCs (control) and the three stages of the parasitic life cycle (ring, trophozoite, and schizont) within a fixed RBC. Standard deviation spectra are shown below each spectrum for both spectral regions. Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society [31].

3.3. Nucleic Acids

The Plasmodium genome is a circular, AT-rich DNA molecule of approximately 23 megabases, containing around 5400 genes [38]. Compared to the genomes of free-living eukaryotic microorganisms, the genome of the intracellular malaria parasite Plasmodium encodes a smaller number of enzymes and transporters. However, a substantial proportion of the Plasmodium genome is dedicated to genes involved in immune evasion mechanisms and host–parasite interactions [38]. During the blood stage of the Plasmodium life cycle, the parasite’s DNA content or the number of daughter cells can increase dramatically within a single round of replication. On average, studies have documented a 20-fold to 30-fold rise in DNA content or daughter cell number over the course of one proliferative cycle [39,40]. This large amount of Plasmodium DNA inside the host red blood cell can be detected and used for diagnosis of malaria infection. In addition to the DNA within infected red blood cells, Plasmodium parasites also release DNA fragments into the host’s bloodstream. These cell-free, circulating Plasmodium DNA molecules can be detected in the modiumma or serum of infected individuals [40]. The presence and quantification of circulating malaria DNA in plasma has emerged as a valuable biomarker for the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of malaria [41]. Circulating Plasmodium DNA can be detected even in low-density infections or in cases where the parasites are sequestered in the deep vasculature, making it a more sensitive method compared to traditional microscopy. Analysis of circulating malaria DNA has also provided insights into parasite dynamics, drug resistance, and the genetic diversity of sp. during infection.

In terms of RNA, malaria parasites exhibit some unique genomic features when compared to other eukaryotic organisms. Most notably, the Plasmodium genome lacks the long, tandemly repeated arrays of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes that are characteristic of many other eukaryotes [38]. Instead, Plasmodium parasites contain multiple single 18S-5.8S-28S rRNA units distributed across different chromosomes [38]. Furthermore, the expression of these rRNA units is tightly regulated throughout the various stages of the Plasmodium life cycle [38]. This results in the selective expression of different sets of rRNAs at different points during the parasite’s development. This developmental regulation of rRNA gene expression contrasts with the more uniform rRNA profiles seen in many other eukaryotic organisms [38].

Vibrational spectroscopic techniques, such as Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy, have faced challenges in the direct detection of DNA within malaria-infected cells. In an early FTIR spectroscopy study investigating single infected rings, trophozoites, and schizonts, no clear DNA phosphodiester bands were identified at the expected wavenumber values of ~1240 cm−1 and ~1080 cm−1, corresponding to the asymmetric and symmetric PO2− vibrations, respectively [31]. Similarly, Raman spectroscopy studies did not detect the characteristic Raman bands at 813 cm−1 or 840 cm−1 that would be anticipated for RNA or DNA [42]. The apparent lack of detectable DNA/RNA signals in these vibrational spectra suggests that the parasite DNA may be present at levels below the sensitivity threshold of these techniques. Another potential explanation for this observation lies in the conformational dependence of the DNA molar extinction coefficient. When DNA is in the dried, A-DNA conformation, the molar extinction coefficient is significantly lower compared to the hydrated, B-DNA state. This is likely due to the more ordered arrangement of the phosphodiester groups in B-DNA, in contrast to the less organized structure of A-DNA. Specifically, in the case of FTIR spectra of DNA, the symmetric PO2− vibration is approximately 3 times less absorbing in the A-DNA form compared to the B-DNA form, and the asymmetric PO2− band is shifted from ~1240 cm−1 in the A-form to ~1220 cm−1 in the B-form [43]. These conformational-dependent changes in the DNA FTIR spectrum may explain the apparent lack of detectable DNA signals in FTIR analyses of dried, malaria-infected red blood cells, as the less IR-active A-DNA conformation predominates under those conditions.

3.4. Proteins

The Plasmodium genome exhibits a high degree of uniqueness, with almost two-thirds of its proteins appearing to be unique to this organism. This proportion is much higher than what is typically observed in other eukaryotes [44]. This finding may be a reflection of the greater evolutionary distance between Plasmodium and the other eukaryotic organisms that have been sequenced to date [44]. Additionally, the (A+T) richness of the Plasmodium genome may have contributed to the reduction in sequence similarity, further exacerbating the observed uniqueness [44]. Another 257 proteins, constituting approximately 5% of the total, showed significant similarity to hypothetical proteins found in other organisms [44].

The increase in parasitic load leads to elevated plasma levels of molecules such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP), and various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and interferon-gamma, are typically seen during this phase, which is common for other types of infection [45]. The most specific protein for malaria infection, particularly for Plasmodium falciparum, is Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2 (PfHRP2), which is produced by the parasite and released into the bloodstream during infection and is widely used in rapid diagnostic tests. However, gene deletions can allow certain parasites to remain undetected [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Another parasite-specific protein, not mentioned in the previous list, is Plasmodium falciparum Lactate Dehydrogenase (PfLDH), with different species of Plasmodium producing slightly different forms of LDH, making it useful for species-specific diagnosis [52,53,54]. Plasmodium Aldolase, a parasite-specific enzyme found in all human malaria species, is less commonly used as a biomarker than PfHRP2 or PfLDH but can be useful for pan-malarial detection [54]. It’s important to note that while these proteins are specific to malaria, their detection doesn’t always indicate an active infection; for example, PfHRP2 can persist in the bloodstream for weeks after successful treatment, potentially leading to false-positive results.

3.4.1. FTIR Spectroscopy of Proteins

The FTIR spectra of uninfected red blood cells are dominated by the alpha-helical protein hemoglobin. Red blood cells contain a remarkably high concentration of hemoglobin, comprising approximately 95% of the total cytosolic proteins within these cells [55]. This hemoglobin is present at a concentration of 5 millimolar (mM) inside the red blood cell [55]. The percentage of hemoglobin in different stages of malaria parasites (rings, trophozoites, and schizonts) varies as the parasite develops within the red blood cell. In the early ring stage, the parasite has consumed relatively little hemoglobin, with approximately 0–20% of the host cell hemoglobin digested. The trophozoite stage is the most active feeding stage, during which about 60–80% of the host cell hemoglobin is typically digested [55]. By the late schizont stage, most of the hemoglobin has been consumed, with approximately 80–100% of the host cell hemoglobin digested. These percentages are approximate and can vary depending on the specific sp. and individual parasites.

FTIR spectra of both infected and uninfected red blood cells at all stages are dominated by strong amide bands appearing at 1650 cm−1 and 1544 cm−1 assigned to the amide I mode (ν(C=O) + ν(C-N) + δ(NH2)) and amide II mode (ν(C-N) + δ(NH2) + ν(C-C) + ν(C=O)), respectively, and a weaker band at ~1300 cm−1 assigned to the amide III mode ((ν(C-N) + δ(CH2) + δ(NH2) +δ(C-C-N) + δ(C-O)). Other bands, including the band at 1450 cm−1 and ~3300 cm−1, are assigned to the carboxylate group of amino acid side chains and the amide A mode (N-H stretching) from the peptide functional group. The amide I mode is very sensitive to protein conformational change, and the profile can be used to predict the relative contribution of alpha-helical, β-pleated sheet, random coil, and other protein conformational motifs [56]. The amide I and II band profile has been shown to change radically between the different stages of the malaria parasite, especially after performing a second derivative [31]. However, in our field trial using ATR-FTIR technology, the amide I and II region was found not to be particularly useful in diagnosing infected from uninfected patients, and instead, the region between 3000–2700 cm−1 and 1200–900 cm−1 proved to be better in terms of sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing patients with malaria infection [57].

3.4.2. Raman Spectroscopy of Proteins

Raman spectroscopy provides valuable information about protein structure and composition through characteristic vibrational bands. In addition to the amide modes mentioned above in the context of FTIR, Raman also shows bands from aromatic amino acid side chains which result in distinct bands from phenylalanine, which shows a sharp peak near 1000 cm−1, tyrosine exhibits a doublet at approximately 830 and 850 cm−1, and tryptophan displays bands at about 760 and 1340 cm−1. The S-S stretching vibration of disulfide bonds appears around 500–550 cm−1. C-H stretching vibrations from aliphatic amino acids are observed in the 2800–3000 cm−1 region. The band near 1450 cm−1 is attributed to CH2 and CH3 deformations. Additionally, the region between 500 and 800 cm−1 contains various skeletal vibrations that can provide information about protein conformation. These Raman bands collectively offer insights into protein secondary structure, side chain environments, and overall conformation, making Raman spectroscopy a powerful tool for protein analysis.

3.4.3. UV/Visible Spectroscopy of Proteins

The UV/Visible spectrum of proteins is characterized by several key absorption bands that provide valuable information about their structure and composition. The primary absorption band in the UV region, known as the peptide bond absorption, occurs around 190–230 nm and is due to the n→π* and π→π* transitions of the peptide bond. This band is present in all proteins and is sensitive to secondary structure. The far-UV region (180–240 nm) is particularly useful for analyzing protein secondary structure, with α-helices showing a characteristic double minimum at 208 and 222 nm, and β-sheets displaying a single minimum near 215 nm. In the near-UV region (250–300 nm), absorption is primarily due to aromatic amino acid side chains: phenylalanine absorbs weakly near 257 nm, tyrosine shows a peak around 274 nm, and tryptophan exhibits the strongest absorption with a maximum near 280 nm. The exact positions and intensities of these aromatic peaks can provide information about the local environment and tertiary structure of the protein. Disulfide bonds (cystine) contribute a weak absorption band around 260 nm. Some proteins containing metal ions or other chromophores may show additional absorption bands in the visible region, such as the heme group in hemoglobin and myoglobin, which gives rise to the Soret band around 400 nm and Q-bands between 500 and 600 nm. Flavoproteins typically show absorption bands in the 350–500 nm range. The overall shape and intensity of the UV/Visible spectrum can be used to estimate protein concentration and purity and to monitor conformational changes. It is worth noting that the exact positions and intensities of these bands can vary depending on the specific protein, its environment, and any modifications or ligands present.

3.4.4. Near Infrared Spectroscopy of Proteins

NIR spectroscopy has been widely used to investigate protein structures, folding patterns in polypeptides, and amino acid composition [58]. The primary functional groups for near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopic analysis in protein studies are the amides and C-H modes. NIR absorption bands related to proteins, particularly amides, are thoroughly detailed in the review by Salzer [59]. The 1500–1530 nm region includes the NH stretching first overtone, while the 2050–2060 nm region pertains to the NH-stretching combination bands. Additionally, absorption bands within the 2148 to 2200 nm wavelength range are valuable for constructing calibration and prediction models in protein research [59,60].

Around the early 2000s, more compact, rapid, and user-friendly spectrometers equipped with state-of-the-art software began to emerge. Miniaturization of NIR devices has significantly reduced the high capital costs associated with traditional large NIR instruments. Over the past decade, there have been substantial advancements in instrument miniaturization, including those designed for use in non-traditional environments [61,62]. Miniaturized NIR instruments are now being utilized by the military for security surveillance, farmers for rapid analysis of agricultural produce and pest control, and pharmacies for drug screening. Additionally, NIR handheld instruments have shown strong potential for disease diagnosis, though this area has not yet been fully explored [63].

4. Application of Spectroscopy for the Detection and Analysis of Malaria Parasites and Related Metabolites

4.1. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy is a technique that identifies the chemical fingerprints of molecules based on their vibrational modes, resulting from inelastic scattering, also known as the Raman effect. This method is rapid, label-free, non-destructive, and highly specific, requiring little to no sample preparation, making it particularly suitable for the analysis of biological samples. Raman confocal microscopy is capable of providing sub-micron spatial and spectral resolution down to subcellular components, enabling the detection of single malarial-infected cells [64].

4.1.1. Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

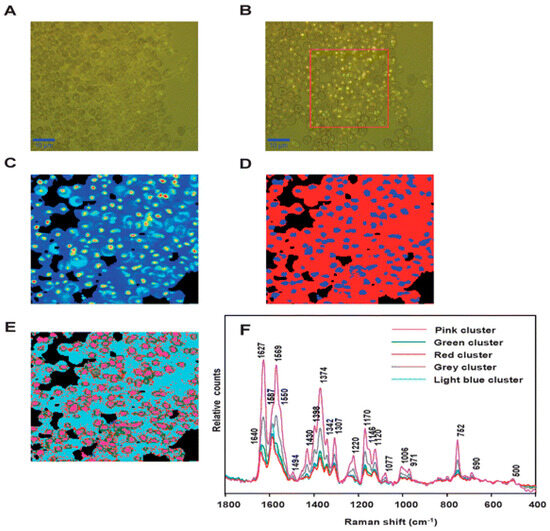

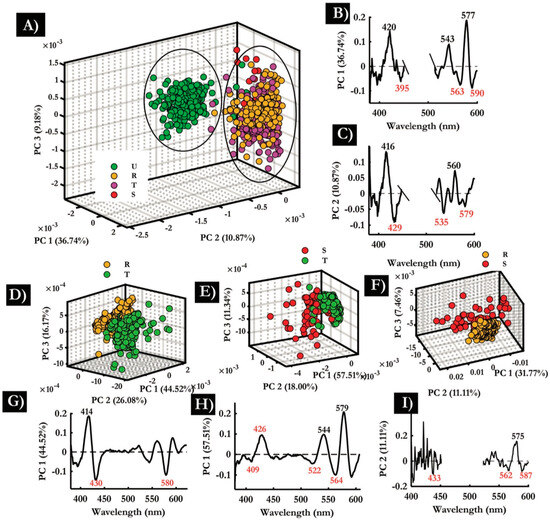

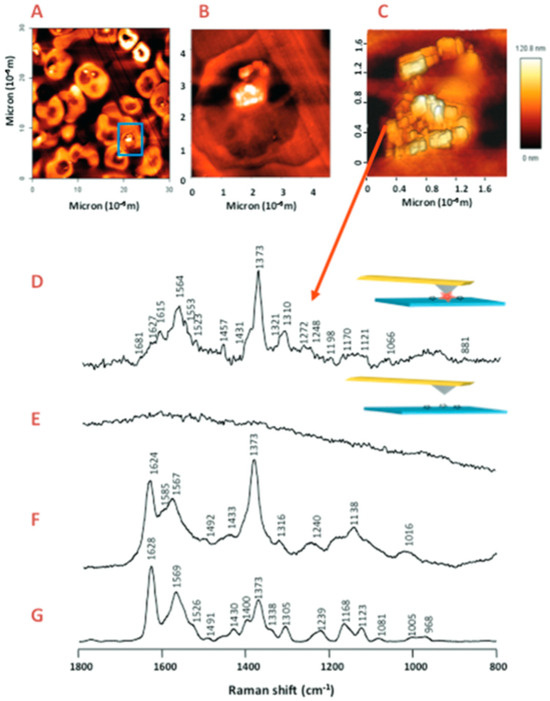

Resonance Raman spectroscopy results in the enhancement of the specific vibrational modes as the excitation wavelength used for Raman coincides with the electronic transition [65]. Ong et al. [66] were the first to compare the Resonance Raman spectroscopy of rodent normal erythrocytes and P. berghei infected erythrocytes using a 488 nm laser, which revealed a shift in peak from 747 to 754 cm−1 in uninfected to infected erythrocytes attributed to the pyrrole breathing mode. They also indicated that the Fe in hemozoin is in a ferric state due to the presence of an oxidation state band occurring at 1371 cm−1 [66]. Hemozoin showed unusual enhancement at 780 nm due to the excitonic coupling in stacked porphyrin moieties as compared to poor enhancement by hemoglobin, thereby enabling Raman imaging of hemozoin within the food vacuole of P. falciparum trophozoites [67]. Resonance Raman mapping has also been utilized along with multivariate analysis to understand the heme species distribution within the erythrocytes infected with P. falciparum. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis (UHCA) was utilized to study the spatial distribution of heme as either hemozoin or hemoglobin. Wood et al. [68] combined resonance Raman spectroscopy with partial dark-field microscopy to identify parasites in RBCs. Figure 8 shows the comparison of the dark field images with the Raman maps along with UHCA maps in the range of 1700–1300 cm−1, clearly indicating the bright spots in the dark-field image correlating with the hemozoin cluster.

Figure 8.

(A) Visible image of the thick film of malaria-infected RBCs. (B) Partial dark-field effect visible micrograph highlighting the trophozoites. (C) Chemical map of the area outlined by the red square (ROI) in (B), generated by integrating the region between 1680 and 1620 cm−1, with lighter colors indicating hemozoin deposits within the trophozoites. (D) UHCA of ROI using D-values algorithm in the range of 1700–1300 cm−1 revealing two clusters: Blue cluster, hemozoin, and red cluster, hemoglobin. (E) UHCA of ROI showing five clusters where the pink cluster spectrum is like hemozoin in the late-stage trophozoites, while green and grey clusters represent a mix of hemoglobin and hemozoin. The light blue cluster corresponds well with the hemoglobin present within RBCs, along with red cluster present as submicron dots (300 nm) corresponding to the hemozoin throughout the stages of P. falciparum life cycle. (F) Mean spectra corresponding to each cluster shown in (E). Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry [68].

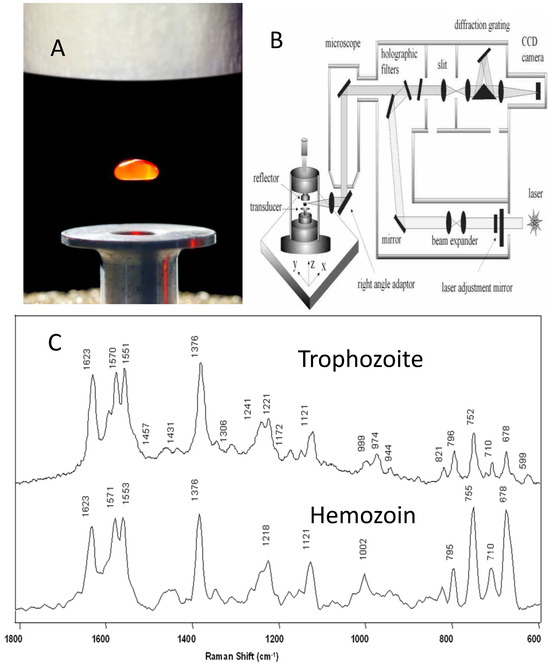

4.1.2. Raman Acoustic Levitation Spectroscopy (RALS)

Several other modalities and functionalities have been combined with Raman microscopy to study malarial parasites. An acoustic levitator was combined with a Raman spectrophotometer to perform Raman acoustic levitation spectroscopy (RALS) on normal RBCs and P. falciparum trophozoites (Figure 9). A 5 µL suspension containing RBCs was levitated to monitor the dynamics of heme in RBCs and was used to detect hemozoin in the malarial infected cells, improving the signal-to-noise ratio of hemozoin due to the concentrating effect of water evaporation in the levitator [69].

Figure 9.

Raman acoustic levitation spectroscopy (RALS). (A) A droplet of isolated red blood cells levitated using a piezo-electric transducer and reflective plate. (B) Schematic showing acoustic levitator coupled to a Raman microscope using a right-angled adaptor. (C) Spectra of trophozoite lysate from lysed red blood cells (top) and micro-Raman spectrum of hemozoin (bottom). Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry [69].

4.1.3. Raman Spectroscopy Coupled to Quantitative Phase Microscopy (QPM)

A novel multimodal microscopy system integrating a confocal Raman microscope and quantitative phase microscopy (QPM) was used to study normal and P. falciparum-infected RBCs [70]. The distribution of hemoglobin in normal red blood cells (RBCs) was analyzed using confocal Raman spectroscopy and correlated with sample thickness to elucidate cellular morphology. A similar approach was subsequently applied to study the hemozoin content in P. falciparum-infected RBCs [70]. A new system involving a fiber array-based spectral translator coupled with a laser illumination system was used for Raman hyperspectral imaging to study early ring-staged P. falciparum-infected RBCs providing improved spectral and spatial resolution compared to tuneable filter Raman imaging [71].

4.1.4. Raman Analysis of Malaria Analytes in Serum, Plasma, and Blood Samples

Raman spectroscopy has been utilized for studying the presence of malarial parasites in serum and blood samples. Serum and plasma samples also provide a valuable means for early-stage detection of malarial parasites, even at parasitemia levels as low as 0.2%, due to the inherent low heme background [42]. Hobro et al. [42] studied the malaria disease progression from 0 to 7 days in blood and plasma samples of mice using Raman spectroscopy and PCA analysis. They analyzed heme, hemoglobin, and hemozoin Raman spectra of blood by looking at the notable differences in three regions: 1100–1200 cm−1 attributed to pyrrole half-ring asymmetric stretching, 1300–1450 cm−1 for C-N stretching of porphyrin ring and 1515–1650 cm−1 for C-C vibrations. In plasma samples, PC2 scores increased with Plasmodium infection and with small positive peaks at ~1628 and 1671 cm−1 correlating to hemozoin and large positive bands at ~2888, 2915, and 2928 cm−1 showing the lipid changes in plasma related to malarial infection [42]. Raman spectroscopy was used to study the early ring staged P. falciparum-infected RBCs in 10 patients (5 malaria-infected and 5 healthy volunteers) by looking at the I1130/I1075 and I2930/I2850 intensity ratio to study alterations in erythrocytes membrane and changes in the structure of membrane lipids and proteins [72]. A rapid diagnostic method was developed to discriminate between 130 patients’ sera, which includes healthy controls, malaria- and dengue-infected patients using Raman spectroscopy and supervised principal components linear discriminant analysis (PC-LDA) methods. The major spectral peaks of molecules studied were creatinine, bilirubin, amino acids (Tyr, Trp, Asn, Glu, Pro, and Phe), protoporphyrin IX, and cell-free DNA [73]. RBCs of 10 patients were analyzed to discriminate between P. falciparum and P. vivax infection using Raman spectroscopy and PCA. Aspartic acid (Asp) vibrations at 1385 cm−1 and Glutamine (Gln) band at 1587 cm−1 were indicative of P. falciparum infection, whereas Tryptophan (Trp) bands at 1361 and 1544 cm−1 were indicative of P. vivax infection [37].

4.1.5. Raman Analysis of Malaria Parasites in Tissues

In terms of organs, malaria mainly infects the brain, spleen, and liver. A few studies have utilized Raman spectroscopic analysis to investigate malaria-infected tissue in mice [74,75]. Hackett et al. [74] used a multi-modal approach incorporating Fourier transform infrared microscopy (FTIRM), particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM), and resonance Raman spectroscopy to study the biochemical alterations occurring at the cellular and subcellular level within the cerebellum tissue of murine cerebral malaria (CM). They combined resonance Raman spectroscopy and XFM to study the tissues surrounding the microhemorrhage to identify the elevation in the non-heme Fe [74]. Another study on mouse spleens infected with P. berghei employed Raman imaging to differentiate between infected and non-infected tissue sections. PCA results revealed a clear distinction between infected and non-infected spleen tissues, attributed to the increase in accumulation of hemozoin in the spleen, with key peaks occurring at 1370, 1529, 1588, and 1628 cm−1 [75]. Raman imaging on the macrophage response to the hemozoin pigment was investigated to understand the biochemical changes in the macrophages upon hemozoin uptake in a timescale of five hours. PCA scores images were used to explain the biochemical changes in the macrophages after three- and five-hour timescales where most of the PC1 component and negative component of the PC3 was attributed to hemozoin bands. The study also identified the localization of hemozoin within the phagosomes and lysosomes of macrophages. However, the investigation of hemozoin degradation was not feasible within the timescales of the study [76].

4.1.6. Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a popular tool to detect and study Hemozoin and other biomarkers [67]. However, Raman scattering is weak in nature and thus not suitable to detect biomarkers in quantities meaningful to diagnostics [77]. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a technique that improves the sensitivity of Raman scattering by attaching plasmonic nanomaterial to the analyte of interest. Under carefully engineered conditions, intense bands appear from trace amounts of analyte that are too weak to appear in an ordinary Raman spectrum. The plasmonic nanostructures amplify the localized electric field of incoming radiation and increase scattering intensities exponentially [78]. This technique is used to detect changes in cell membranes due to malarial infection.

SERS spectra of ring-stage infected RBCs show a characteristic Raman band at 1599 cm−1, which is absent in healthy RBCs. In contrast, the trophozoite and schizont stages exhibit identical SERS bands, featuring a characteristic peak at Δν = 723 cm−1 [79]. The vibrational features of hemozoin 754 cm−1, 1120 cm−1, 1551 cm−1, 1570 cm−1, and 1628 cm−1 can be observed in the SERS spectra of hemozoin and infected RBCs. The bands common between hemozoin and healthy RBCs are 1120 cm−1, 1570 cm−1, and 748 cm−1 could be attributed to hemoglobin in the cells [80]. Plasmodium schizonts are easily observed under a microscope due to their larger size and distinct morphology, while the smaller size and subtle appearance of ring-stage parasites make them more challenging to detect. However, Giemsa-stained parasites can be readily observed in both stages [80].

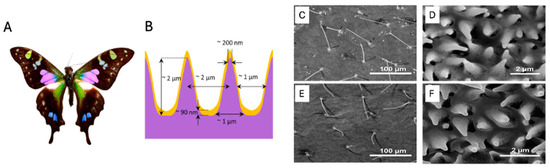

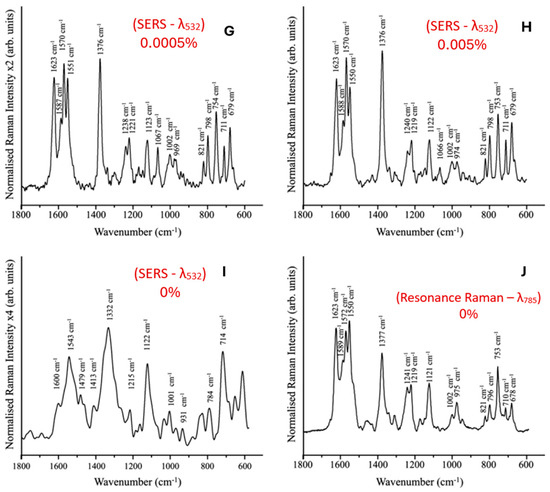

The Graphium weiskei butterfly wings (Figure 10A) feature a unique nanostructure that can be utilized for biosensing applications. A schematic cross-sectional view of a gold-coated wing (Figure 10B) reveals typical chitinous conical protrusion dimensions and spacings, as observed in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images. SEM analysis of the wings shows chitinous nano-structured conical arrays (Figure 10C–F), both after deposition with P. falciparum-infected red blood cell (RBC) lysate (Figure 10C,D) and in control wings without lysate deposition (Figure 10E,F). SER spectra were obtained for various concentrations of malarial-infected RBC lysate, including 0.0005% (Figure 10G), 0.005% (Figure 10H), and a 0% control (Figure 10I). For comparison, a conventional Raman spectrum of hemozoin at 785 nm is also presented (Figure 10J). These findings demonstrate the potential of butterfly wing nanostructures as sensitive biosensors for malaria detection.

Figure 10.

(A) Graphium weiskei butterfly wings. (B) Schematic cross-sectional view of a gold-coated wing showing typical chitinous conical protrusion dimensions and spacings based on SEM images. (C–F) SEM images of chitinous nano-structured conical arrays found on the wings of the G. weiskei butterfly. (C,D) SEM images acquired after deposition with P. falciparum-infected RBC lysate. (E,F) Control butterfly wings without lysate deposition. (G–I) SERS spectra of 0.0005%, 0.005%, and 0% (control) malarial-infected RBC lysate, respectively. (J) Conventional Raman spectrum of hemozoin at 785 nm. Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry [81].

The SERS technique relies heavily on hotspots that trap analytes within multiple sharp plasmon tips [78]. This condition is difficult to control and poses a challenge in acquiring SERS signals [82]. By aggregating hemozoin using a magnetic field, faster detection can be achieved.

4.1.7. Magnetic Field-Assisted SERS

Infected RBCs have a higher ratio of paramagnetic Fe2+ ions compared to healthy RBCs, and there is a detectable change in magnetic properties. This property has long been used to test malarial infection [83]. Paramagnetism of β-hematin (an equivalent marker of hemozoin) is also exploited by using magnetic field-induced aggregation that leads to better sensitivity in the SERS technique.

Ultrasensitive detection of β-hematin was demonstrated with a tuned core–shell thickness of iron oxide core and silver shell [82,83] coupled with magnetic field enrichment of hemozoin. A study performed by Liu et al. [84] demonstrates SERS combined with resonant wavelength detection of β-hematin of 5 × 10−9 M or equivalent to 30 parasites/µL.

Commonly used SERS substrates, Silver NPs (AgNPs) provide low sensitivity of 500 parasites/µL [85]. To improve this, Chen et al. [85] demonstrated two ways of incorporating plasmonic component in the infected blood sample; synthesized silver nanoparticles mixed with lysed blood samples led to a more consistent signal enhancement whereas silver nanoparticles synthesized directly in P. falciparum parasites showed higher sensitivity to malarial parasites owing to greater adsorption of hemozoin on silver nanoparticles. Recently, nanostructured gold (AuNS) was used to obtain SERS from 0.1 parasites/µL from infected blood samples of 25 patients [86]. In another study, to ease point-of-care detection, a microfluidic chamber was interfaced with contact-activated AgNP synthesis. The detection limit for this method was 125 parasites/µL [87]. Yuen et al. [88] optimized Fe3O4@Ag core-shell nanoparticles for magnetic field-enhanced SERRS detection of β-hematin (a malaria biomarker), demonstrating both experimentally and theoretically that optimal particle size and magnetic field-induced aggregation are crucial for achieving highly sensitive detection. A polystyrene-based microfluidic device combined with SERS immunoassay was developed for malaria detection, achieving parasitemia detection of 0.0012% in P. falciparum samples-seven times more sensitive than current rapid diagnostic tests while being adaptable for point-of-care testing and other pathogens [89]. Table 1 summarizes the types of SERS approaches applied to detect malaria and their respective sensitivities.

Table 1.

Summary of SERS-based methods to detect malarial parasites.

4.2. Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR)

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is a variant of FTIR spectroscopy that utilizes a high refractive index internal reflection element (such as diamond, silicon, germanium, or ZnSe). Infrared light is directed between this element and the sample at an angle greater than the critical angle, resulting in total internal reflection. The evanescent wave generated at the interface interacts with the sample, providing valuable spectral information. ATR-FTIR is non-destructive and requires minimal sample preparation, allowing for rapid analysis of biological samples like blood. Additionally, it can detect subtle biochemical changes associated with malaria infection by providing detailed molecular fingerprints (Table 2). This capability makes it a promising tool for early-stage malaria detection, potentially reducing reliance on more time-consuming, reagent-based diagnostic methods.

Table 2.

IR band assignment for the spectra of RBCs and malaria parasites [8,9,11].

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy has emerged as a rapid and cost-effective method for screening and diagnosing infectious diseases. The first study on its application for malaria diagnosis was conducted by Khoshmanesh et al. [7] in 2014. Their work demonstrated the ability of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, coupled with chemometric analysis, to detect and quantify different stages of malaria parasites in infected erythrocytes. They reported significant spectral differences between the various stages of parasite development within red blood cells (RBCs) and achieved a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.00001%, which translates to <1 parasite/µL of blood and is comparable to the gold standard of detection by PCR. This pioneering study opened the door for future developments in ATR-FTIR-based malaria diagnostics.

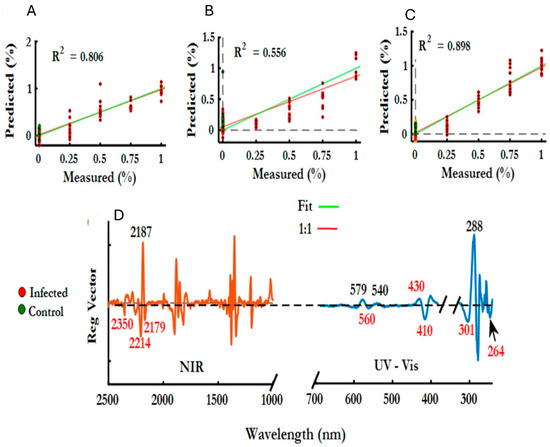

Despite its advantages, such as minimal sample preparation and rapid analysis, challenges remain, particularly when analyzing clinical samples. Factors like biological variability and sample pre-processing, which are hard to replicate in laboratory settings, can impact accuracy. For instance, anticoagulants used to prevent blood clotting can interfere with key spectral bands. Martin et al. [90] studied the effects of common anticoagulants—sodium citrate, potassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and lithium heparin on ATR-FTIR spectra for malaria diagnosis. Sodium citrate exhibits strong absorption at 1572 cm−1 due to carboxylate groups, EDTA at 1618 cm−1 for its carboxylate groups, and heparin contributes bands at 1146 and 1036 cm−1 (carbohydrates), 1438 and 1420 cm−1 (secondary amines), and 1628 cm−1 (sulfonated amine). These bands, falling within the fingerprint region, can obscure key biological signals, complicating detection. However, heparin had the least spectral interference, allowing successful calibration (R2 = 0.92) in samples with parasitemia levels up to 0.1%.

Another source of variability in samples comes from metabolic changes, which can significantly impact the spectra, especially when analyzing whole blood. While whole blood is easier to work with, serum components can heavily influence the spectral data. In 2017, Roy et al. [91] conducted a study that demonstrated the ability of ATR-FTIR to correctly identify 98% of parasitemia samples with densities above 0.5% (~25,000 parasites/µL). This was the first multianalyte diagnostic study using ATR-FTIR, where they simultaneously predicted levels of parasitemia, urea, and glucose. The researchers spiked whole blood with Plasmodium cultures and prepared 132 specimens with varying amounts of P. falciparum parasites, glucose, and urea by creating multiple aliquots. Remarkably, only 5 µL of isolated RBCs was sufficient to cover the ATR crystal, highlighting the technique’s efficiency in sample usage. In 2019, Mwanga et al. [92] used ATR-FTIR on dried blood spots collected in the field, coupling it with machine learning algorithms to differentiate between positive and negative cases and identify the parasite species, which is discussed under “Clinical field trials of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy”.

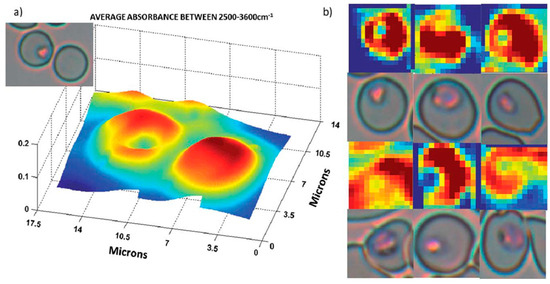

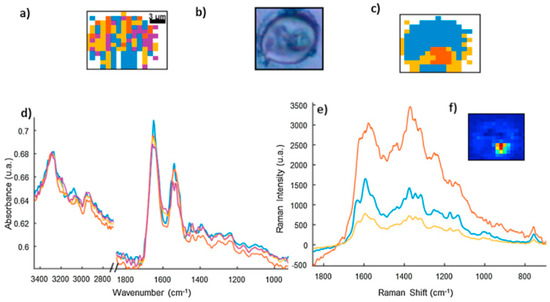

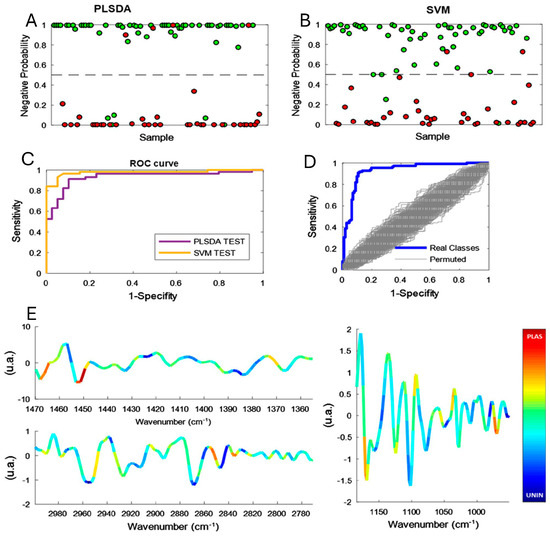

4.3. Focal Plane Array Fourier Transform Infrared (FPA-FTIR) Imaging Spectroscopy

FTIR can be combined with a focal plane array (FPA) detector to simultaneously acquire 16,384 spectra, generating hyperspectral infrared images composed of 128 × 128 pixels. By producing spatially resolved spectral data, it has been effectively used to diagnose malaria in red blood cells at the single-cell level and to investigate the structures of infected red blood cells. Perez-Guaita et al. [93] used a 25x Cassegrain objective to achieve a 0.66 µm2 pixel size, an effective 1.4 µm2 spatial resolution and investigated thin-layer RBCs on glass slides. Using a supervised leave-one-out PLS-DA cross-validation approach, they achieved success with 88% specificity and 87% sensitivity in distinguishing malaria-infected from control RBCs [93]. Bands at 3300 cm−1, 2952 cm−1, and 2870 cm−1 were the most significant contributors to the observed separation, corresponding to asymmetric and symmetrical CH3 stretching vibrations and amide A bands, respectively. Furthermore, a change in the lipid-to-protein ratio was attributed to the consumption of hemoglobin within the erythrocyte [93]. Figure 11 shows a 3D representation of infected and healthy RBCs that closely resembled their visible images. Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) performed on these cells showed bands at 2914 cm−1, 3150 cm−1, 3028 cm−1, and 3300 cm−1 were significant in achieving 81% specificity and 83% sensitivity in distinguishing trophozoite vacuoles from cell cytoplasm [93].

Figure 11.

Infrared images of trophozoites inside infected erythrocytes. (a) Three-dimensional representation of an infected and an uninfected cell. (b) False color images of 6 erythrocytes infected with trophozoites and their visible images. Color scale corresponding to the integration area underneath each spectrum (pixel). Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry [93].

However, when similar FPA-FTIR experiments were conducted using a 15× objective on CaF2 slides and unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis, the results were not replicated. For this magnification, the spectra were dominated by bands attributed to hemoglobin and were not representative of hemozoin or the signature lipid and DNA bands expected to be seen with bacteria [94]. Furthermore, Banas et al. [95], using 1800 cm−1–1000 cm−1 region and a 15× objective, were unable to separate infected from control RBCs using principal component analysis, highlighting the importance of highly resolved data points and peak selection when using infrared imaging modalities [95].

With its non-destructive and label-free imaging approach, FPA-FTIR can also be used to investigate pathologies within tissues. Cerebral malaria is one of the most severe complications from malaria infection, with a mortality rate of 15–20% even after treatment. The symptoms include altered consciousness and convulsions that can lead to comas and death, often in young children with developing immune systems [96,97]. Pathologies of encephalopathy, endothelial activation, and damage to the blood–brain barrier are often observed post-mortem and are major contributing factors in fatal cases [96]. FPA-FTIR has successfully been used to contribute to the growing body of knowledge of cerebral malaria pathogenesis and how neurological symptoms manifest. Hackett et al. [74] used murine models of cerebral malaria to show heightened lactate levels and protein aggregates at hemorrhage sites within the brain, using bands at 1742 cm−1, 1566 cm−1, 1625 cm−1, and 1127 cm−1 to demonstrate lipid, α-helix proteins, β-pleated sheet proteins, and lactate, respectively. The 1742 cm−1 decreased in white matter at the sites of hemorrhage, alongside an increase in 1656 cm−1, 1627 cm−1, and 1127 cm−1, corresponding to increased α-helical and β-pleated sheet structures colocalized with an increase in lactate concentration. Adjacent to sites of hemorrhage, decreased α-helical content was observed alongside an increase in lactate and β-pleated sheet structures in the granular layer of the cerebellum [74].

The same group also found crystalline creatine microdeposits within the granular and molecular layers of the cerebellum. Using FPA-FTIR imaging, Hackett et al. [98] employed the lipid carbonyl band at 1742 cm−1 and the organophosphate band at 1087 cm−1 to isolate the white matter, granular, and molecular layers of the cerebellum and, using multivariate K-means clustering analysis, found creatine microdeposits throughout the granular and molecule tissue layers due to the signature 1402 cm−1 band of creatine. These deposits could not be observed in traditional H&E staining methods performed after FPA-FTIR imaging, thereby demonstrating the unique advantage of chemical mapping over traditional staining methods [98].

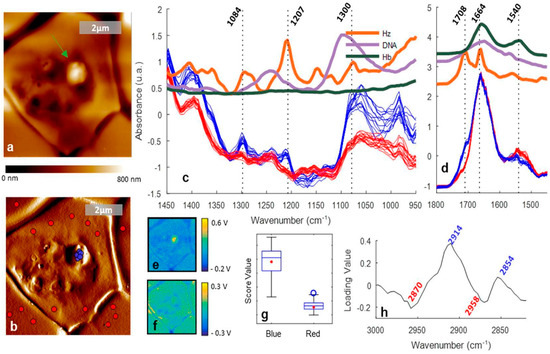

4.4. Synchrotron FTIR Spectroscopy

A synchrotron is a particle accelerator that produces a high-energy beam of charged particles, usually electrons. As they follow a circular path, they emit synchrotron radiation, which is a highly intense and focused beam of electromagnetic radiation that spans from the range of X-rays, passing through the visible and reaching the far infrared. Synchrotron provides a much brighter and more intense source of infrared light, which gives a better signal-to-noise ratio and enables the detection of weaker signals. The pulsed nature allows for time-resolved studies that make it possible to observe dynamic processes in real time. With the objective of a brighter source, also in malaria, synchrotron light has been used.

Pioneering studies in 2009 were performed at the Australian Synchrotron to discriminate the different erythrocytic lifecycle stages of the malaria parasite in erythrocytes. Webster et al. [31] applied synchrotron infrared spectroscopy to acquire single-point spectra from single red blood cells and compared the spectra from different stages of the infection (schizont, trophozoite, ring). Major differences were found in the C-H stretching region and the ester carbonyl band. Excellent discrimination was achieved between infected and control cells using an artificial neural network.

Wood et al. [99] used the IRENI synchrotron to illuminate the focal plane array detector and increase its signal and the speed at which the spectra are acquired since with an FPA in each acquisition, 4096 spectra are saved for each tile. In this work, the different stages of cells were possible to discriminate by using hierarchical cluster analysis.

Even though the limit in spatial resolution due to diffraction limitations is now being overcome with recent advances in technology like the far field Optical Photothermal Infrared (O-PTIR) instrument and the near field technology like AFM-IR, the results presented here are still milestones in the search for understanding malaria infection and the stages of the infected red blood cells by pushing the limit in the technique’s capabilities. A recent study compared FTIR, AFM-IR, and O-PTIR to distinguish P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes, as discussed below [95].

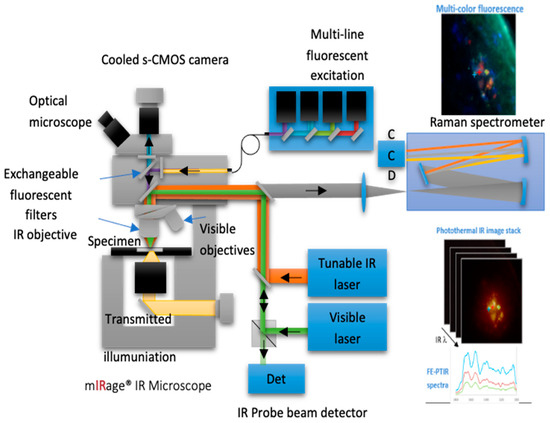

4.5. Optical Photothermal Infrared (O-PTIR) Imaging

Typical IR microspectroscopic techniques covered previously are restricted by their diffraction-limited optical components and thus have an achievable spatial resolution on the order of microns in the mid-IR spectral regions [100,101]. Although these spatial resolutions are sufficient for analyzing, for example, the chemical composition of whole single infected and healthy erythrocytes, obtaining chemical information on subcellular components is beyond the reach of these techniques. The Plasmodium parasite and its associated digestive vacuole (an important therapeutic target) [102,103] are typically much smaller than the achievable spatial resolution of IR microscopes [104,105,106]. Hence, investigating the interaction of the parasite with the host or potential therapeutic treatments using IR spectroscopy would heavily benefit from a smaller achievable spatial resolution. Optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy (O-PTIR) is a technique with the ability to meet these needs, with an achievable spatial resolution of about 500 nm [107]. Furthermore, unlike the diffraction-limited IR microscopes, this spatial resolution is achievable across the entire mid-IR range that is accessible to these instruments. To achieve this greater spatial resolution, O-PTIR instruments introduce a monochromatic visible laser light collinear with the incident IR beam. The IR beam induces a photothermal effect in the sample that modulates the reflection and scattering of the visible light. The photothermal effect is proportional to the absorption of IR light by the sample. Therefore, the measurement of the intensity of the collected visible light is proportional to the IR absorption, producing an O-PTIR spectrum that is analogous to a typical IR spectrum (Figure 12) [108,109]. A much smaller spatial resolution is now achievable since it is determined by the diffraction limit of the visible light’s wavelength and optics. Nevertheless, this technique has only been made available very recently, and its applications to malaria research are severely limited, with only a single study published thus far. Banas et al. [95] investigated the use of O-PTIR for the characterization of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes and compared it against data obtained with an FTIR microscope equipped with an FPA detector. Initially, the authors perform a simple comparison of the techniques by mapping a single healthy erythrocyte. The spectra collected using the FTIR microscope lacked contrast across the map, while the spectra collected with O-PTIR are clearly heterogeneous, revealing the intracellular chemical and morphological variability of the erythrocyte owed to the technique’s submicron spatial resolution. Next, they investigated whether either technique exhibited an advantage in discerning between healthy and P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes by performing PCA on datasets containing spectra collected from these groups. In the first three principal components (PCs, 67.4% explained variance) of the dataset collected with an FTIR microscope, there was no evident clustering or separation of the healthy and infected cells, suggesting this technique’s inability to identify infected cells. In contrast, the data collected with O-PTIR displayed a clear separation of the classes along the first PC (55.9% explained variance). Peaks represented in the loadings plot of this PC could be directly related to the presence of hemozoin, particularly from the peak around 1720–1708 cm−1 arising from H-bonded carboxylate groups. This clear separation of the healthy and infected erythrocytes in the O-PTIR data demonstrates the advantages that the greater spatial resolution of this technique provides. Despite the current lack of reported studies employing this technique, there is unmistakable potential for future promising discoveries that could be made in malaria research with its utilization.

Figure 12.

A diagram of the instrumentation and operation of an O-PTIR microscope (Photothermal Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). This figure is from an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY license [109].

4.6. Near Infrared Spectroscopy

Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy has seen considerable progress since its discovery in the 18th century by Frederick W. Herschel, who initially observed that NIR radiation is absorbed by matter. This method generally employs photon energies between 1.65 eV and 4.96 eV, spanning a wide wavelength range from 750 nm to 2500 nm (0.75 μm to 0.25 μm) [110]. Molecules absorb NIR radiation when the frequency of the radiation matches the intrinsic vibrational frequencies associated with mainly overtone and combination bands. Due to anharmonicity, multiple transitions occur between various vibrational energy states (where Δν = ±1, ±2, ±3, etc.). These multilevel energy transitions are the basis for near-infrared overtones, which appear as integral multiples of the fundamental absorption frequencies [111,112].

In the electromagnetic spectrum, NIR overtones are found between 780 nm and 2000 nm, depending on the mass of atoms and the bond strength. In polyatomic molecules, different vibrational modes can combine to cause simultaneous energy changes, resulting in combination bands that typically occur between 1900 nm and 2500 nm [111,112]. NIR spectra mainly display significant X–H chemical vibrations (C–H, O–H, N–H, and S–H) [113]. One major challenge with the use of this technique is that the individual bands in NIR measurement are not well-resolved compared to mid-infrared bands due to nearly all participating molecules absorbing NIR energy across the entire wavelength region. This makes it challenging to establish a usable baseline for simple quantitative methods like peak-height or peak-area analysis. However, new methods have been developed to address background interferences and poor spectral resolution, which have been thoroughly reviewed [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117].

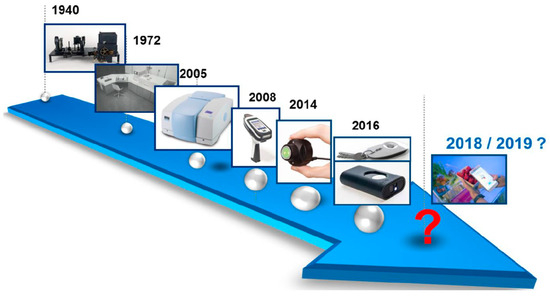

Around the early 2000s, more compact, rapid, and user-friendly spectrometers equipped with state-of-the-art software began to emerge (Figure 13). Miniaturization of NIR devices has significantly reduced the high capital costs associated with traditional large NIR instruments. Over the past decade, there have been substantial advancements in instrument miniaturization, including those designed for use in non-traditional environments [61,62,118,119]. Miniaturized NIR instruments are now being utilized by the military for security surveillance, farmers for rapid analysis of agricultural produce and pest control, and pharmacies for drug screening. Additionally, NIR handheld instruments have shown strong potential for disease diagnosis, though this area has not yet been fully explored [63].

Figure 13.

Trends in miniaturization of near-infrared spectrometers. This article containing this figure is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 License [119].