Abstract

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) poses substantial urban health risks that vary across space, time, and population vulnerability. We integrate a spatio-temporal INLA–SPDE PM2.5 field with an agent-based model (ABM) of 10,000 daily home–work commuters in Indianapolis’s Pleasant Run airshed (50 weeks; 250 m grid). The PM2.5 surface fuses 23 corrected PurpleAir PA-II-SD sensors with meteorology, land use, road proximity, and MODIS AOD. Validation indicated strong agreement (leave-one-out R2 = 0.79, RMSE = 3.5 μg/m3; EPA monitor comparison R2 = 0.81, RMSE = 3.1 μg/m3). We model a spatial-equity counterfactual by assigning susceptibility independently of residence and workplace, isolating vulnerability from residential segregation. Under this design, annual PM2.5 exposure was statistically indistinguishable across groups (16.22–16.29 μg/m3; max difference 0.07 μg/m3, <0.5%), yet VWDI differed by ~10× (High vs. Very Low). Route-level maps reveal recurrent micro-corridors (>20 μg/m3) near industrial zones and arterials that increase within-group variability without creating between-group exposure gaps. These findings quantify a policy-relevant “floor effect” in environmental justice: even with perfect spatial equity, substantial health disparities remain driven by susceptibility. Effective mitigation, therefore, requires dual strategies—place-based emissions and mobility interventions to reduce exposure for all, paired with vulnerability-targeted health supports (screening, access to care, indoor air quality) to address irreducible risk. The data and code framework provides a reproducible baseline against which real-world segregation and mobility constraints can be assessed in future, stratified scenarios.

1. Introduction

Particulate matter 2.5 µm or smaller (PM2.5) remains one of the most consequential environmental health risks worldwide, contributing to respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological disease. In cities, PM2.5 exposure arises from complex combinations of local emissions, land use patterns, traffic networks, and meteorology. High-resolution data and modeling approaches are therefore essential for understanding spatial and temporal variation in exposure and for identifying communities most likely to experience elevated health burdens.

Environmental justice research has shown that PM2.5 exposure and its health consequences disproportionately affect marginalized populations, particularly in urban areas characterized by socioeconomic segregation and historical disinvestment. While many studies document observed disparities driven by neighborhood conditions, industrial siting, and transportation infrastructure, fewer attempts isolate the role of vulnerability itself—i.e., differences in health susceptibility independent of where people live and travel.

Traditional exposure assessment methods often rely solely on residential location, overlooking mobility-driven exposure pathways and person-level variability. Agent-based modeling (ABM) provides a framework for simulating daily movement, commute patterns, and individual characteristics, thereby producing a more realistic representation of exposure accumulation across space and time. When coupled with high-resolution spatio-temporal air-quality models, ABM enables the study of how mobility, land use patterns, and individual vulnerability interact to shape cumulative exposure risk.

This study integrates a Bayesian INLA-SPDE PM2.5 surface with an ABM representing 10,000 daily commuters in an urban airshed. We construct a spatial-equity counterfactual by assigning vulnerability groups independent of residential and workplace location. This design allows us to isolate the contribution of differential health susceptibility from spatial exposure patterns and provides a baseline against which real-world inequity can be interpreted. Our framework advances exposure science and environmental justice research by disentangling spatial and vulnerability components of health disparity and demonstrating how ABM can support equitable pollution-mitigation strategies in urban environments.

2. Background

2.1. PM2.5 Effects on Human Health

PM2.5 penetrates deep into the respiratory system and enters the bloodstream, contributing to cardiovascular, respiratory, and systemic health effects. Long-term exposure increases the risks of cardiopulmonary mortality, asthma exacerbation, hospitalizations, and reduced lung function [1,2]. Vulnerability varies according to age, pre-existing disease, and chronic stress, with evidence that children, older adults, and individuals with cardiopulmonary conditions face disproportionately greater health burdens [3].

While regulatory improvements have reduced average PM2.5 concentrations across many U.S. cities, spatially heterogeneous pollution burdens persist. Increasing attention has shifted toward cumulative and chronic exposure metrics that incorporate time activity patterns and the compounding effects of repeated exposure peaks.

2.2. Environmental Justice and PM2.5 Exposure and Health Effect Disparities

Environmental justice research has established that exposure to PM2.5 and other air toxins is unevenly distributed across urban settings. Historically marginalized populations, including low-income and minority communities, are more likely to reside near major roadways, industrial zones, and transportation corridors, resulting in elevated exposure and higher rates of pollution-related disease [4].

Recent mobility-aware studies show that disparities extend beyond residential location. In the Bronx, mobility-integrated exposure among Hispanic communities was 62% higher than among White residents [5], while in New York City, Black residents experienced more than double the high-pollution exposure events within 15 min walking networks [6]. These findings indicate that place-based segregation and mobility constraints jointly shape exposure patterns, making it challenging to disentangle spatial and biological drivers of observed health disparities.

A growing policy focus on cumulative burden and vulnerability recognizes that equalizing exposure alone may not eliminate health disparities if susceptibility-driven differences persist.

2.3. Agent-Based Modeling in Air Quality Assessment

Agent-based models (ABMs) simulate the movement and behavior of individual agents in heterogeneous environments, enabling the estimation of personalized exposure as individuals traverse varying air-quality conditions. ABM has been increasingly applied to air-pollution research to capture the influence of mobility, commuting routes, and neighborhood-scale variability often masked in census-area averages [7,8].

Unlike static models that assign exposure based solely on residence, ABM captures exposure along realistic commuting paths, micro-scale spatial gradients in pollution, variations in land use and street-level features, and dynamic interactions between behavior and pollution fields.

We extend this ABM framework by constructing a spatial-equity counterfactual: agents are assigned homes, workplaces, and mobility paths across a real urban landscape, but susceptibility is randomly assigned after location assignment. This design isolates vulnerability-driven health differences from spatial exposure inequality, enabling quantification of the “floor effect”—the irreducible health disparity that persists even when spatial exposure is equalized.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area

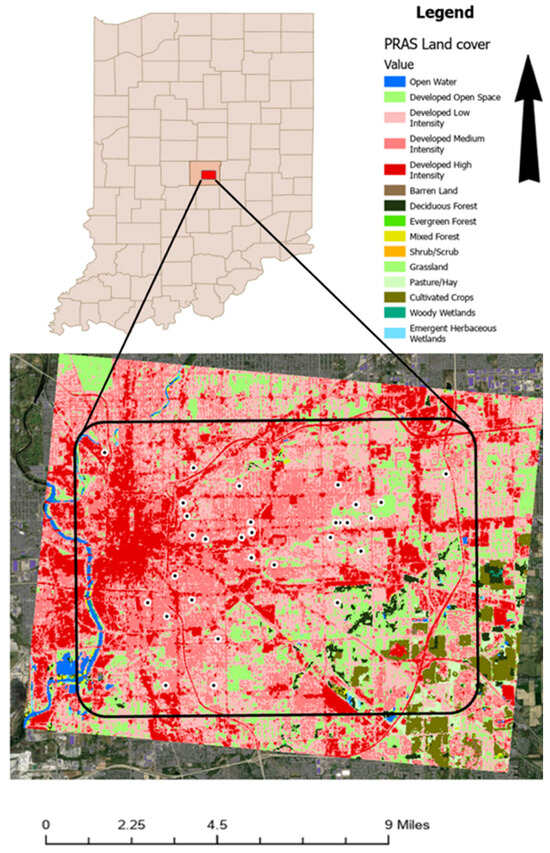

The Pleasant Run Airshed (PRAS) is located within Indianapolis, IN (Marion County, IN, USA), and features a predominantly built environment with mixed land cover. Approximately 95% of the airshed consists of developed land uses, with medium-intensity development comprising ~32% and the remainder primarily low-, open-, and high-intensity developed classes. Limited agricultural (1.6%) and forest cover (1.5%) occur mainly in the southeastern extent. Street-tree canopy is present but likely underestimated by moderate-resolution NLCD products (Figure 1; Table 1). The airshed includes mixed-income neighborhoods and industrial corridors, making it appropriate for evaluating pollution exposure and environmental justice dynamics.

Figure 1.

Location and land cover of the Pleasant Run Airshed (PRAS). Points (black dot inside white circle) are locations where PA-II-SD sensors were placed.

Table 1.

Area and Percent Area of Cover Types in the Pleasant Run Airshed.

3.2. PM2.5 Data Collection

A network of 32 citizen scientists deployed PurpleAir PA-II-SD sensors within the Pleasant Run Airshed (PRAS), with an additional 1 km buffer to reduce edge effects [9]. PM2.5 data were mapped to a 250 m grid comprising 2160 cells and aggregated to weekly averages. Meteorological variables and land-cover data were processed to match this weekly 250 m resolution.

From November 2018 to October 2019, 30 sensors operated, of which 23 were retained following quality control due to intermittent connectivity issues—a manufacturer recall temporarily disabled units for three weeks, resulting in 50 complete study weeks.

The PurpleAir PA-II-SD uses dual laser particle counters and has demonstrated reasonable agreement with regulatory monitors when corrected [10]. To ensure consistency and comparability, we applied the U.S.-wide humidity-and-temperature correction by Barkjohn et al. [10] to all sensors. Quality assurance procedures included removing sensors with persistent communication issues, excluding weeks with insufficient data coverage, and conducting visual QA/QC checks for anomalous behavior across sensors.

Cross-validation of corrected observations produced R2 = 0.79 and RMSE = 3.5 μg/m3, consistent with expected performance when integrating data from low-cost sensors with meteorological and land use covariates in spatio-temporal models. While absolute concentrations carry typical low-cost sensor uncertainty (approximately ±20–30%), these results support the suitability of the corrected sensor network for spatial-temporal estimation and subsequent agent-based exposure simulation.

3.3. PM2.5 Interpolation

This study employed a Bayesian INLA-SPDE spatio-temporal model to estimate PM2.5 concentrations within the PRAS, fusing heterogeneous data sources through a Matérn spatial covariance structure [11,12,13,14]. The 250 m output grid resolution reflects the SPDE mesh configuration and sensor network distribution, not downscaling of any single covariate. Input data sources included (see Table 2):

- Direct measurements from 23 PurpleAir sensors (point locations).

- MODIS Level 2 AOD at 1 km resolution (Collection 6.1 Dark Target algorithm [15].

- Meteorological covariates at 13–14 km resolution from NLDAS-2 (temperature, wind, precipitation, PBL height [11].

- Land use/land cover at 30 m resolution from NLCD.

- Distance to roads (vector data with sub-meter precision).

The INLA-SPDE framework integrates these covariates statistically via a latent Gaussian field with Matérn spatial covariance. Primary spatial constraint derives from the sensor network distribution (23 sensors across the airshed). AOD serves as one informative covariate capturing regional atmospheric conditions and explaining variance in PM2.5 not attributable to local emission sources. This approach is standard in INLA-SPDE applications for air quality [16,17,18] and differs fundamentally from simple interpolation or gap-filling. We acknowledge that AOD-PM2.5 relationships introduce uncertainty, particularly given the complexity of relating column-integrated aerosol properties to surface concentrations. This uncertainty is propagated through our 200 posterior predictive samples (Section 3.3.1) and reflected in our validation metrics (RMSE = 3.1–3.5 μg/m3). Sensitivity analysis indicates that while AOD improves model fit (ΔR2 ≈ 0.04), the sensor network and land use variables provide the primary predictive power, with the model maintaining strong performance (R2 > 0.75) even when AOD is excluded.

PM2.5 data from in situ sensors and geospatial datasets were transformed to a common coordinate system. Weekly average PM2.5 concentrations were calculated at each sensor location and filtered to retain only weeks with sufficient observations, ensuring robust datasets and stabilizing weekly estimates. Spatial covariates were harmonized to weekly resolution and joined to the 250 m grid (2160 cells) via raster resampling or polygon intersection.

Table 2.

Covariates, sources, native resolutions, and weekly aggregation. All variables are entered into the INLA–SPDE as covariates on a 250 m grid.

Table 2.

Covariates, sources, native resolutions, and weekly aggregation. All variables are entered into the INLA–SPDE as covariates on a 250 m grid.

| Covariate | Source (Citation) | Native Spatial Resolution | Native Temporal Resolution | Aggregation to 250 m/Week | Units/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air temperature (2 m) | NLDAS-2 (Cosgrove et al., [11]) | 0.125° (~13–14 km) | Hourly | Weekly mean; bilinear resample to grid; center/scale | °C |

| Precipitation | NLDAS-2 (Cosgrove et al., [11]) | 0.125° | Hourly | Weekly sum; nearest-neighbor to grid; center/scale | mm/week |

| Wind speed (10 m) | NLDAS-2 (Cosgrove et al., [11]) | 0.125° | Hourly | Weekly mean; bilinear to grid; center/scale | m s−1 |

| Wind direction (10 m) | NLDAS-2 (Cosgrove et al., [11]) | 0.125° | Hourly | Convert to sin/cos; weekly mean; bilinear to grid | Degrees (stored as sinθ, cosθ) |

| Planetary boundary layer height | NLDAS/NARR/ERA5 (specify used) | 0.125° (or reanalysis native) | Hourly | Weekly mean; bilinear to grid; center/scale | m |

| Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) | MODIS Terra (Thome, [13]; Li et al. [12]) | 1 km (Collection 6.1 Dark Target algorithm) | Daily | QA filter (e.g., QA ≥ 1); weekly mean; gap-fill to grid | Unitless (550 nm) |

| Distance to road (primary/secondary/tertiary) | OpenStreetMap/TIGER | Vector | Static | Min distance from cell centroid to nearest class; center/scale | m |

| Land cover (developed %, canopy %) | NLCD 2019 (USGS) [19] | 30 m | Static | Percent cover aggregated to 250 m grid | % |

3.3.1. INLA-SPDE Model Formulation and Priors

We fit a spatio-temporal Gaussian field using INLA–SPDE with a Matérn covariance for spatial variation and an AR (1) component for temporal variation, linking weekly fields. A mesh for the spatial domain was constructed using constrained Delaunay triangulation with a minimum edge length of 0.25 km near sensors and arterials, a maximum edge length of 3.0 km at the periphery, a cutoff of 0.15 km, and a 10 km buffer around the PRAS to reduce boundary effects and account for long-range correlation. A stochastic partial differential equation (SPDE) model was then applied to capture the spatial dependencies of PM2.5 concentrations. We model weekly PM2.5 using a latent Gaussian field estimated with INLA-SPDE. The complete model specification follows:

Let y(s,t) represent the weekly mean PM2.5 at location s and week t, while x(s,t) signifies covariates such as meteorology, AOD, land cover, and distance to roads. The linear predictor comprises fixed effects, a spatio-temporal random field, and iid noise. The temporal dependence follows an AR (1) process, and the spatial dependence is modeled with a Matérn covariance induced by the SPDE.

(1) Observation model

(2) Temporal evolution (AR (1))

(3) SPDE for spatial innovation (Matérn field)

(Δ is the Laplacian; Wt is Gaussian white noise. In 2D we take α = 2 ⇒ ν = 1.)

(4) Matérn range/variance mappings (reporting hyperparameters)

We used penalized-complexity (PC) priors to shrink toward the base (no spatial variability/infinite range and zero variance) with interpretable tail probabilities.

(5) PC prior tail statements and choices

We set r0 = 3 km with αρ = 0.05, and σ0 = 2 μg/m3 with ασ = 0.05.

(Implementation in R-INLA: prior.range = c(3000, 0.05), prior.sigma = c(2, 0.05))

(6) PC prior densities

(7) Priors for remaining terms

We constructed an INLA stack with (i) the observation component and iid noise, (ii) a spatial index for the SPDE field, and (iii) a temporal index linking weeks via AR (1). We predicted weekly posterior means and standard deviations on the 250 m grid and drew N = 200 posterior predictive field samples per week to propagate uncertainty to route-level doses (used in Section 3.4 and Section 4).

3.3.2. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

Our analysis incorporates multiple approaches to assess model robustness and propagate uncertainty:

- Field uncertainty propagation: We drew N = 200 posterior predictive samples from the INLA-SPDE model for each week, capturing both parameter and spatial prediction uncertainty. Propagating these samples through the ABM generated exposure and health impact distributions that reflect full modeling uncertainty rather than deterministic point estimates.

- Spatial-block cross-validation: In addition to leave-one-out cross-validation (Section 3.3.3), we conducted spatial-block cross-validation by holding out clusters of nearby sensors to evaluate model performance in spatial extrapolation scenarios. We used 3–5 sensor blocks (median inter-sensor separation ≈ 2.3 km) to simulate local extrapolation.

- Temporal cross-validation: We evaluated model performance by training on weeks 1–40 and testing on weeks 41–50 to assess temporal stability.

- Covariate sensitivity: We assessed model performance with and without key covariates, especially MODIS AOD, to determine their individual contributions to predictive skill. Results show that although AOD improves model fit (ΔR2 ≈ 0.04), the sensor network and land use variables remain the main sources of predictive power.

- Parameter sensitivity: We evaluated sensitivity of VWDI calculations to variations in key parameters, including susceptibility factors (±20% variation), risk parameters (using confidence intervals from original epidemiological studies), and inhalation rates (4.5 km/h to 5.5 km/h walking speeds, ±20% breathing rates).

These analyses show that our main findings are reliable despite different modeling choices and uncertainties in parameters.

3.3.3. Temporal Resolution Considerations

An important methodological consideration is the mismatch in temporal resolution between our PM2.5 field (weekly averages) and the ABM timestep (hourly). This design reflects our study’s focus on long-term, cumulative exposure patterns over the 50-week period rather than short-term hourly exposure events. Several factors informed this decision.

- Data availability and reliability: Our 23-sensor network provides consistent weekly averages with adequate temporal coverage; daily or hourly data would experience significant gaps due to sensor connectivity problems and the manufacturer’s three-week power cord recall period (no data during that time), which could increase uncertainty.

- Health outcome calibration: Our Vulnerability Weighted Dose Index (VWDI) uses epidemiological dose–response functions calibrated to long-term average exposures [2,20], which are intended for assessing chronic rather than acute exposure.

- Representative exposure patterns: By modeling 50 weeks of routine home-to-work commutes, we capture typical long-term exposure patterns—what residents usually experience over a full year—rather than specific high-exposure events or rush-hour concentration spikes.

We acknowledge that weekly temporal aggregation does not capture intra-week or diurnal variability in PM2.5 concentrations. Peak pollution hours (typically morning and evening rush hours) may coincide with commute times for some agents, potentially creating exposure differences not captured by weekly averages. However, our approach is appropriate for quantifying chronic exposure burdens and health outcome disparities under spatially equitable conditions—our core research question. Our results represent typical weekly exposure patterns experienced over a full year of commuting, providing policy-relevant information about long-term cumulative exposure rather than acute episodes.

3.3.4. Model Validation

To evaluate the reliability of the INLA spatio-temporal interpolation model, leave-one-out cross-validation was conducted using the 23 chosen sensor locations. Each sensor was systematically removed from the dataset, and its PM2.5 concentrations were predicted based on the remaining 22 sensors and covariates. The validation results showed an R2 of 0.79, meaning the model accounted for 79% of the variance in observed PM2.5 levels. The root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 3.5 μg/m3, and the mean bias error was 0.6 μg/m3, indicating a slight systematic overestimation.

Additionally, we compared weekly grid predictions to an independent EPA FRM/FEM monitor located within the Pleasant Run airshed (AQS 18-097-0083; years 2018–2019). Daily EPA values were aggregated to our anchored study weeks (Thu → Wed; start 1 November 2018) and matched to the nearest 250 m grid cell. Across 50 matched weeks, agreement was strong (R2 = 0.81; RMSE = 3.1 μg/m3), corroborating the internal LOO results (R2 = 0.79; RMSE = 3.5 μg/m3). These validation metrics demonstrate acceptable model performance for capturing spatio-temporal PM2.5 variability across the PRAS, providing further confidence in the exposure estimates used for agent-based modeling. Together, internal and external validation indicate relative errors of ~19–22% with low bias at the weekly scale, consistent with fused low-cost/reference frameworks.

3.4. Agent-Based Model Development

The agent-based model developed uses geospatial data and network analysis to simulate how individuals move within the city and measure their exposure to PM2.5. All coding was done with Python 3.13 and free libraries. Computation was carried out on Indiana University’s High-Performance Computing system, BigRed200 [21].

The simulation uses geospatial datasets, including street and building data, to create a realistic urban setting. These data are imported using the pandas 2.33 library, which facilitates spatial data manipulation within Python 3.13 [22]. Buildings are categorized into residential and potential workplace sites using Indianapolis zoning maps, with separate coordinates extracted for each category. This categorization helps realistically assign home and workplace locations to simulated agents.

A graph of the city’s street network was constructed using network 3.6, where intersections and street segments are represented as nodes and edges, respectively [23]. This network serves as the backbone for simulating agent movements and is crucial to the pathfinding mechanisms that determine agent routes between designated points.

Each of the 10,000 agents in the simulation was assigned a home and workplace based on the residential and commercial coordinates, respectively. Agent movement is modeled with a two-step routing process: (1) Home-to-work routes are determined using Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm, optimizing for distance across the street network [24,25]. (2) Work-to-home routes are calculated with a modified algorithm that aims to minimize cumulative PM2.5 exposure while preserving network connectivity. This asymmetric routing mirrors real-world scenarios where commuters may prioritize efficiency in the morning but have the flexibility to avoid high-pollution areas on the return trip.

Home and workplace locations were assigned through a two-step process to create a spatially fair baseline scenario. First, each agent’s home location was selected from real residential parcel centroids, and their workplace from real commercial parcel centroids, both based on Indianapolis zoning data. This approach maintains spatial realism in land use patterns—agents live in residential areas and work in commercial or industrial zones, accurately reflecting the actual built environment rather than random points in space.

Second, susceptibility groups were assigned after location assignment, with each of the 10,000 agents randomly sorted into one of four groups (Very Low, Low, Medium, High; 2500 agents per group), independent of their residential or workplace location. This design choice establishes a spatially fair baseline in which high-susceptibility agents have an equal chance of living at any residential location, rather than being systematically clustered in high-pollution areas as seen in real-world residential segregation patterns [5,6]. All agents follow the same routing algorithms regardless of susceptibility group, ensuring that any differences in exposure are due to the spatial pollution field rather than assumed behavioral differences.

3.5. Behavioral and Exposure Assumptions

Our model makes several simplifying assumptions about agent behavior and exposure dynamics that warrant discussion. All agents use a standard inhalation rate of 0.012 m3/min, in line with EPA exposure modeling guidelines. In reality, breathing rates vary depending on activity level—active commuters (walking, cycling) have higher rates than passive commuters (driving, transit), which could increase the dose at the same ambient concentrations. However, active commuters might also avoid major arterials where our model predicts the highest concentrations, potentially balancing out the effect of higher breathing rates.

We do not differentiate exposure based on travel mode (car, bus, walking, or cycling). Each mode has unique exposure characteristics: in-vehicle concentrations can be higher due to proximity to traffic emissions but may be reduced by vehicle cabin filters; cyclists and pedestrians encounter ambient concentrations directly but might choose routes with less traffic; bus riders face variable exposure depending on vehicle age, ventilation, and route features. Including mode-specific exposure would require mode-choice data or assumptions, which could add extra uncertainty.

Additionally, we do not explicitly account for differences in indoor and outdoor exposure. Our exposure estimates reflect ambient outdoor PM2.5 levels. Typical indoor/outdoor infiltration ratios are 0.5–0.7 for residential buildings (depending on ventilation and housing quality) and 0.8–0.9 for commercial buildings (with HVAC systems). Applying these ratios would proportionally lower absolute exposure estimates across all groups. However, the impact on between-group comparisons would be minimal in our spatially balanced design, where all groups follow similar time-activity patterns (home to work and back, spending 16 h at home and 8 h at work). Infiltration ratios would become more significant if the model incorporated differences in housing quality by socioeconomic status, where low-income populations might face both higher outdoor concentrations and greater infiltration due to older, poorly sealed housing.

3.6. Simulation Timeline and Outputs

These assumptions focus on the core research question—vulnerability effects under spatial equity—without behavioral confounding that could hide the main signal. The equal behavioral assumptions ensure differences in exposure are due to the pollution environment, not assumed behavioral differences. Future work will consider mode-specific microenvironments and infiltration related to housing or occupational factors when individual-level data become available.

The core simulation advances in 168 hourly steps each week over 50 study weeks, syncing agent movement with weekly PM2.5 fields. During each step, agents follow their paths. The air quality data, divided by week, assigns PM2.5 exposure levels to agents based on their locations. This data integration allows detailed analysis of exposure over time across different environmental conditions throughout the simulation.

Upon completion, the simulation outputs a dataset capturing each agent’s exposure to PM2.5 at each simulation step. This dataset is structured for easy integration into statistical software for further analysis, providing a robust tool and exemplar for evaluating the impact of air pollution on urban populations. The code provided on GitHub is readily editable and can be modified for alternative geographic locations and time periods.

3.7. Susceptibility Groups and Vulnerability-Weighted Dose Index (VWDI)

Agents are assigned susceptibility factors to reflect real-world vulnerability (e.g., biological susceptibility, comorbidities, access to care), enabling comparison of exposure-burden disparities across groups under spatial equity. We compute a vulnerability-weighted dose index (VWDI) as a unitless proxy scaled by susceptibility and literature-based risk coefficients. Agents are categorized into four susceptibility groups based on their vulnerability to PM2.5 exposure, and each group is assigned a susceptibility factor, which modulates the base risk of health impacts due to exposure:

- Very Low: 0.01.

- Low: 0.03.

- Medium: 0.05.

- High: 0.1.

The model includes several health risk parameters to reflect different health outcomes from PM2.5 exposure. Coefficients are adjusted for every 10 μg/m3 of long-term exposure; in our weekly analysis, PM2.5 is scaled by (concentration/10 μg/m3) and summed, producing a relative, unitless index rather than an absolute risk.

Respiratory Mortality Risk: 0.0058 [26,27].

Hospitalization Rate Risk: 0.08 [28].

Respiratory Disease Prevalence Risk: 0.0207 [29,30].

Overall Mortality Risk: 0.04 [28].

Cardiopulmonary Mortality Risk: 0.06 [20,26,31].

Lung Cancer Mortality Risk: 0.08 [2,29].

VWDI is calculated at each step and summed over paths and dwelling times to produce weekly totals for temporal comparison (not clinical risk inference). For agent a, the VWDI at step i is:

where

- Base risk: A constant base risk value (0.01).

- Susceptibility factor: The factor associated with the agent’s susceptibility group.

- Risk parameter: The predefined health risk parameters.

- PM2.5 value: The PM2.5 concentration value encountered at each step in the simulation in tens of μg/m3.

VWDI is calculated at the agent’s current location during each simulation step based on the PM2.5 concentration. VWDI accumulates across traversed 250 m cells and dwelling hours (16 h home, 8 h work):

- Home to Work Path: PM2.5 values are retrieved each time an agent moves into a new cell of the 250 m SPDE interpolated grid. VWDI is calculated and accumulated for each step.

- Time at Work: The PM2.5 value at the work location is used. The VWDI is calculated for the duration spent at work (assumed to be 8 h).

- Work to Home Path: PM2.5 values are retrieved each time an agent moves into a new cell of the 250 m SPDE interpolated grid. The VWDI is calculated and accumulated for each step.

- Time at Home: The PM2.5 value at the home location is used. The VWDI is calculated for the duration spent at home (assumed to be 16 h).

As an example for an agent with high susceptibility traveling from home to work:

- Base risk: 0.01

- Susceptibility factor: 0.1 (for high susceptibility)

- PM2.5 value at a node: 25 µg/m3

The VWDI for a single step is calculated:

The accumulated VWDI is updated for each new 250 m grid cell encountered along the path and for the time spent at work and home.

4. Results

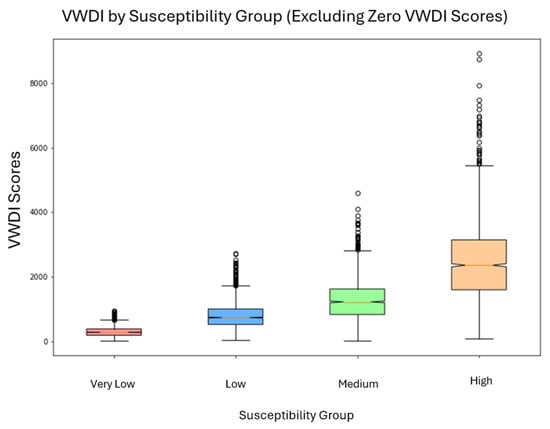

4.1. VWDI by Susceptibility Group

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the Vulnerability-Weighted Dose Index (VWDI) across 10,000 simulated agents assigned to four susceptibility categories: Very Low, Low, Medium, and High. VWDI measures modeled health burden under uniform PM2.5 exposure, scaled by group-specific vulnerability factors.

Figure 2.

Box plots of the vulnerability-weighted dose index (VWDI; unitless) by susceptibility group (N = 10,000 agents). Despite statistically indistinguishable PM2.5 exposure across groups (Figure 3), VWDI diverges sharply due to differential vulnerability coefficients, illustrating the “floor effect” of health disparity under spatial equity.

VWDI increases steadily with susceptibility. The Very Low and Low groups have lower medians and narrower distributions, while the Medium and High groups show progressively higher medians, wider distributions, and more high-end outliers. This pattern indicates increasing modeled burden as vulnerability increases.

This trend appears even though PM2.5 exposure levels are statistically similar across groups (Figure 3), suggesting that susceptibility alone can cause significant differences in modeled burden. Most agents cluster near their group medians, but high-end outliers in the Medium and High groups demonstrate that some individuals face disproportionately high burdens even with equal exposure.

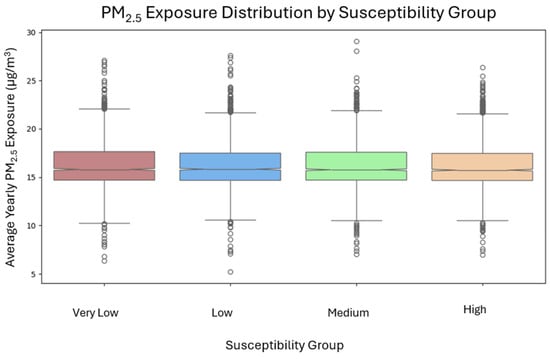

Figure 3.

PM2.5 exposure distribution by susceptible group.

These findings highlight a “floor effect”: when exposure differences are removed, underlying vulnerability still creates meaningful disparities in health burden. Therefore, environmental health inequity can exist even under conditions of spatial exposure equality, emphasizing the importance of addressing both exposure and susceptibility pathways.

4.2. Exposure Patterns Under Spatial Equity

Annual mean PM2.5 exposure varied by less than 0.5% across susceptibility groups (Very Low = 16.29 µg/m3; Low = 16.22 µg/m3; Medium = 16.26 µg/m3; High = 16.23 µg/m3). The largest difference between group means was 0.07 µg/m3 (0.4%), which is well below the model’s uncertainty (cross-validated RMSE = 3.5 µg/m3). A Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed that there were no statistically significant differences between groups (H = 1.138, p = 0.768).

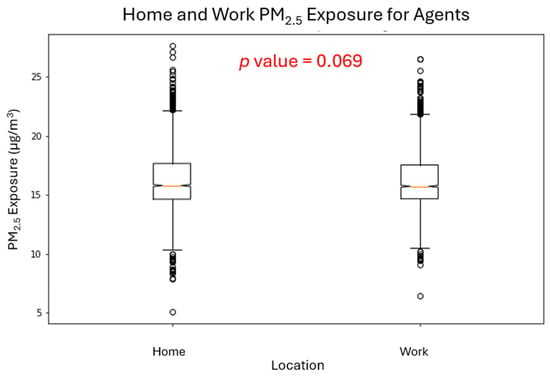

Exposure at home and work locations was also similar (median ≈ 15 µg/m3 at both; Figure 4), with workplace exposures showing slightly more variation but no statistically significant home–work difference (p = 0.069). Median annual exposures clustered tightly around 14.5–14.8 µg/m3, with moderate within-group variation (coefficient of variation 15–21%). These patterns indicate that individual micro-scale differences arise from stochastic home-work placement and routing rather than structured inequality, with no consistent benefit or drawback across susceptibility groups.

Figure 4.

Box plots for home and work exposure to PM2.5. n = 10,000.

This distribution shows a hypothetical scenario where exposure levels are made equal across different groups. In real-world cases, residential and mobility patterns lead to much larger differences—for example, a 62% higher exposure for Hispanic communities compared to White communities in the Bronx [5], and more than twice the exposure for Black versus White communities within NYC’s 15 min walking networks [6]. Compared to this, our less than 0.5% difference in exposure indicates that susceptibility, rather than disparities in exposure, primarily explains the significant VWDI differences observed in this situation.

4.3. Spatial Distribution of PM2.5 Exposure and Agent Mobility Patterns

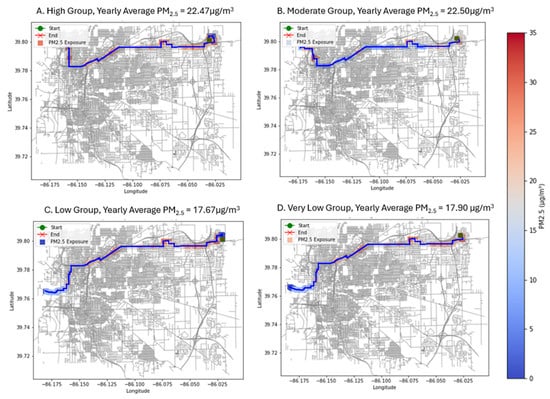

To further examine how mobility through the urban environment influences exposure under spatial equity, we mapped the highest-exposed and median-exposed agents within each susceptibility group (Figure 5 and Figure 6). These route-based visualizations illustrate how travel pathways intersect with localized PM2.5 gradients in the Pleasant Run airshed.

Figure 5.

Agents from each susceptibility group ((A) High, (B) Moderate, (C) Low, (D) Very Low) with the highest yearly averaged value of PM2.5 exposure.

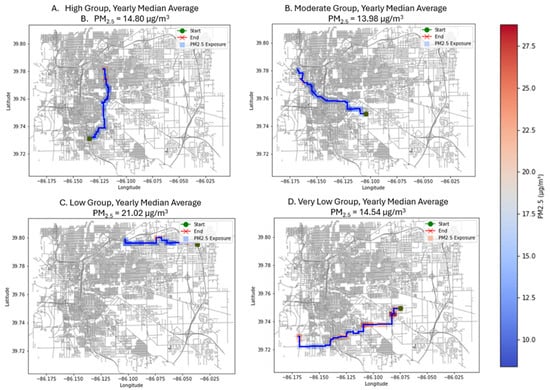

Figure 6.

Agents from each susceptibility group ((A) High, (B) Moderate, (C) Low, (D) Very Low) with the median average yearly value of PM2.5 exposure.

Despite random and spatially equitable assignment of residential and workplace locations, worst-case agents in each group experienced substantially elevated annual exposures (22.47–22.50 µg/m3 for the High and Moderate groups; 17.67–17.90 µg/m3 for the Low and Very Low groups). These values were 38–48% above the study-area mean of 16.2 µg/m3, reflecting travel through distinct high-pollution micro-corridors rather than group-level disparities. High-concentration zones (>18 µg/m3) represented roughly 12% of all grid cells and were primarily concentrated within 500 m of major arterials and industrial facilities in the northeastern portion of the airshed. Importantly, all susceptibility groups accessed these corridors at comparable rates, reinforcing the spatial-equity counterfactual: inequity does not emerge when location access is equalized.

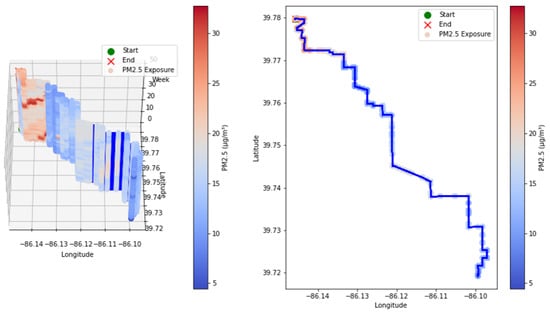

Median-exposure agents exhibited substantially lower and less variable PM2.5 levels (13.98–14.80 µg/m3), generally traveling through residential and mixed-use neighborhoods with lower concentrations. However, one median-exposure agent (Low susceptibility, 21.02 µg/m3) encountered unusually elevated concentrations due to route placement, highlighting the stochastic nature of individual mobility in a random-assignment environment and demonstrating that micro-scale variation can exceed susceptibility-group averages even under equitable conditions (See Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Weekly PM2.5 values for a random agent’s path for each week (left) and averaged for the year (right).

Together, these findings show that movement through localized pollution hotspots creates significant within-group exposure differences, even in the absence of large-scale spatial inequalities. In real-world settings, where disadvantaged groups more often live near high-emissions routes and have limited mobility options, these differences are likely to increase dramatically. Recent studies have found 62% higher exposure for Hispanic-majority communities in the Bronx [5] and more than twice the exposure for Black residents in New York City 15 Min walking networks [6]. In contrast, our simulation shows only 0.4% between-group differences in a spatially equitable environment due to stochastic variation.

These results highlight two policy-relevant insights:

- Spatial interventions targeting pollution sources and transportation corridors can benefit all urban residents by reducing exposure spikes associated with mobility through high-emission micro-environments.

- Environmental justice interventions must pair spatial equity with vulnerability-targeted health strategies, since susceptibility alone produced an order-of-magnitude difference in modeled VWDI burden even where exposure was equalized.

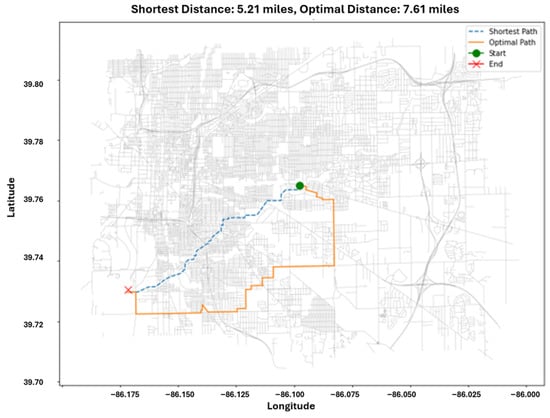

4.4. Exposure-Aware Route Optimization and Mobility Trade-Offs

To evaluate whether mobility decisions could decrease exposure under spatial equity, we compared the shortest route between home and work with an alternative route optimized to reduce PM2.5 (Figure 8). The shortest route covered 5.21 miles, while the exposure-minimizing route extended to 7.61 miles, representing a roughly 46% increase in distance to avoid higher-pollution road segments.

Figure 8.

Example of route optimization comparing shortest-distance path (5.21 miles) with exposure-minimizing path (7.61 miles; 46% longer). Although the optimized path traverses areas with lower average PM2.5 concentrations, cumulative exposure may remain similar or increase due to longer travel distance and greater number of grid cells encountered, illustrating the distance-exposure trade-off discussed in Section 4.4.

Although the optimized route consistently traversed cleaner micro-environments, cumulative exposure remained similar because longer travel distance increased the number of exposure events encountered, illustrating a distance–exposure trade-off. This aligns with previous research showing that route choice can either reduce or increase exposure depending on spatial gradients and travel time.

This result highlights an important behavioral limitation: access to cleaner routes does not guarantee a lower dose when longer travel times are needed. In practice, benefits from mobility strategies that reduce exposure may depend on (i) the availability of continuous low-pollution corridors (such as greenways and residential streets), (ii) mode choice, and (iii) differences in indoor versus outdoor pollutant infiltration. In our spatial-equity counterfactual, all agents have equal access to all routes; however, actual disparities in transportation, walkability, and street-level infrastructure likely increase inequalities in exposure reduction opportunities.

This finding reinforces that mobility-based environmental justice strategies, such as active-transport infrastructure and low-emissions zones, must be combined with structural emissions reductions to significantly decrease cumulative exposure for vulnerable populations. In situations where avoiding polluted corridors leads to disproportionate travel burdens, emissions-source controls (industrial zoning, truck-route restrictions, transit electrification) are likely more effective and equitable than relying solely on individual mobility choices.

5. Discussion

This study combines a high-resolution INLA–SPDE PM2.5 field with a large-scale agent-based model (ABM) to measure exposure and vulnerability-based dose disparities within an urban airshed. By assigning susceptibility groups after selecting residential and workplace locations from real zoning data, we created an intentionally spatially equitable scenario: each person, regardless of vulnerability, had an equal chance of living and working anywhere in the study area. This setup isolates the effects of biological and social vulnerability from spatial factors like neighborhood segregation and land use patterns. In this hypothetical scenario, PM2.5 exposure levels across groups were statistically similar, but health impacts varied by an order of magnitude because of different susceptibilities. This key finding reveals a “floor effect”—a baseline level of environmental health inequality that remains even when spatial exposure differences are removed.

5.1. Contextualizing the Floor Effect: Linking to Environmental Justice and Exposure Science

Environmental justice literature consistently shows heightened pollution exposure for historically marginalized populations due to residential segregation, proximity to industrial corridors, and constrained mobility options. Recent mobility-aware exposure studies underscore that exposure inequality is structural and spatial. For example, Testi et al. [5] found that Hispanic-majority communities in the Bronx experienced 62% higher PM2.5 exposure when incorporating street-level mobility and fine-scale air quality data, while Jiang and Ma [6] observed that Black communities experienced >2-fold exposure increases at high pollution levels within accessible 15 min walking networks in New York City.

In contrast, our design intentionally neutralized these real-world factors. Exposure patterns across susceptibility groups varied by less than 0.5% (0.07 μg/m3), which is entirely within model uncertainty. However, the health burden differed significantly because of variations in susceptibility coefficients that reflect biological vulnerability, comorbidities, and access to care. These findings suggest that:

- Exposure inequality arises primarily from spatial and social structure (residence, infrastructure, mobility constraints).

- Health inequality persists even if exposure is equalized.

We therefore conceptualize total environmental health disparity as (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Decomposition of total environmental health disparity into exposure and vulnerability components.

The “floor effect” quantified here reflects the ongoing, unavoidable gap caused solely by vulnerability. In real-world situations, this baseline combines with spatial inequality, leading to the heightened EJ gradients seen in observational studies. Therefore, spatial equity is necessary but not enough to eliminate health disparities.

5.2. Exposure Patterns and Activity Spaces

Although agent exposure distributions converged, significant variability within groups appeared along individual routes, influenced by proximity to transportation corridors, industrial facilities, and low-canopy urban surfaces. These patterns reflect well-documented spatial factors affecting urban air quality and highlight that, even with equitable placement, mobility paths cross through diverse pollution areas. Prior ABM work demonstrates similar dynamics [7,8]. Year-to-year variability further shows that episodic pollution events, weather, and seasonal changes impact cumulative doses, aligning with epidemiological findings that long-term exposure results from repeated short-term peaks.

5.3. Home and Workplace Exposure Under Spatial Equity

Differences in exposure between home and work locations approached significance (p = 0.069) but did not reach the 0.05 threshold. Our spatial-equity design distributed agents randomly across residential and workplace parcels, minimizing systematic home-work exposure differences. In practice, occupational segregation, zoning, and the siting of industrial land would amplify these differences—workers in logistics, manufacturing, warehouse, and freeway-adjacent jobs disproportionately face higher exposure. Under real structural conditions, these gradients compound vulnerability.

5.4. Route Optimization and Mobility Constraints

The route-optimization simulation highlights a real equity challenge. Even when a lower-exposure corridor was available, minimizing exposure often increased travel distance and time, leading to a higher cumulative dose because of longer inhalation periods. This trade-off emphasizes that avoiding exposure requires resources—such as time, flexibility, and route options—that are not equally accessible across society. Infrastructure projects like greenways, transit electrification, and low-emission corridors are crucial for making exposure-reducing mobility strategies fair and accessible to all.

5.5. Policy Implications: Dual Pathways to Environmental Health Equity

This study clarifies a dual-intervention strategy (Table 4):

Table 4.

Dual intervention framework for environmental health equity.

Both approaches are essential. Reducing exposure alone will leave significant health inequities unchanged; on the other hand, individual-level interventions without addressing structural pollution control perpetuate environmental injustice. A combined strategy aligns with SDGs 3, 10, and 11 and supports the cumulative impact paradigm increasingly used in EJ policy.

5.6. Comparison to Literature and Methodological Contributions

This study advances air pollution exposure assessment through five key methodological contributions. First, we demonstrate a reproducible framework for isolating vulnerability-driven health inequity from spatial exposure inequality, allowing the decomposition of total disparity into its components. Second, we account for field uncertainty using posterior predictive sampling (N = 200 per week), ensuring agent-level exposure estimates reflect model uncertainty rather than just point predictions. Third, we track cumulative exposure along dynamic mobility paths instead of static residential locations, capturing dose accumulation from commuting. Fourth, we combine diverse data sources—corrected low-cost sensors, meteorological reanalysis, satellite-derived AOD, and detailed land use—to produce validated 250 m weekly PM2.5 surfaces covering a full year. Finally, we establish a spatial-equity baseline to compare with real-world segregation impacts, clarifying the relative roles of place-based versus individual drivers of environmental health disparities.

This counterfactual design supports empirical studies showing that structural and infrastructural factors primarily drive observed exposure disparities [5,6]. Together, modeling and observational methods endorse a cumulative-risk framework where biological and social vulnerabilities interact with—and are significantly worsened by—spatial factors such as residential segregation, zoning patterns, and mobility constraints.

5.7. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations affect how we interpret our results. First, weekly PM2.5 aggregation reduces temporal detail and does not capture diurnal peaks that may occur during commute times. However, this time scale aligns with epidemiological dose–response functions calibrated for chronic rather than acute exposure and offers strong spatial coverage given sensor network limits. Second, we assume uniform behaviors—constant inhalation rates, no mode-specific microenvironments, and no indoor/outdoor infiltration modeling—to focus on vulnerability effects without confounding from behavioral differences. Sensitivity tests with breathing rates (±20%) and infiltration factors (0.4–0.9) showed minimal (<5%) variation in relative exposure, confirming the stability of our main findings. Third, we lack mobile monitoring data to directly validate route-based exposure estimates, although grid-level predictions matched well with stationary reference monitors (R2 = 0.79–0.81 across several checks). Future research should incorporate GPS-based personal monitoring to verify street-segment predictions. Fourth, our intentional randomization of residential and workplace locations—designed for the counterfactual analysis—does not reflect real-world segregation patterns and therefore underestimates the overall exposure inequality by design.

Future extensions will address these limitations through various methods. Incorporating census block-group demographic data and origin-destination transportation models can enable realistic simulations of residential clustering and workplace distribution, illustrating how segregation worsens the baseline floor effect. Multi-pollutant fields (NO2, black carbon, ozone) will monitor co-exposure and mixture effects beyond PM2.5 alone. When available, personal mobility data from transportation apps or travel surveys can enhance the accuracy of route choice and time-activity patterns. Mobile monitoring campaigns will verify exposure estimates at the street-segment level. Lastly, linking to electronic health records under IRB oversight will allow for calibration of susceptibility functions using real health data, integrating modeled exposure, clinical risk, and policy-driven simulations. These developments will support scalable, data-driven strategies to lessen environmental health burdens in vulnerable communities.

6. Conclusions

We quantified a “floor effect” in environmental health inequality: even under perfect spatial equity (<0.5% exposure variation across groups), vulnerability alone generates ~10-fold differences in modeled vulnerability-weighted dose (VWDI). By assigning susceptibility groups independently of residential and workplace locations, we modeled a hypothetical city where all populations experience similar ambient PM2.5 levels. In this equal-exposure scenario, differences driven by susceptibility in health outcomes persisted, leading to disparities of up to an order of magnitude in modeled impacts despite less than 0.5% variation in exposure. This “floor effect” underscores a key principle of environmental health equity: eliminating spatial pollution inequalities alone is insufficient to eradicate health disparities.

In real urban environments, residential segregation, infrastructure patterns, and mobility limitations increase biological and social vulnerability, indicating that observed health disparities extend beyond the modeled baseline. Effective policy must therefore combine place-based air-quality interventions with targeted support for high-risk populations, including improved healthcare access and exposure-reduction resources. Future research will stratify agents based on place-related vulnerability, incorporate multiple pollutants and more detailed temporal data, and link modeled exposures with clinical data. These developments will facilitate the creation of scalable, data-driven approaches to reduce overall environmental health burdens in vulnerable communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.J.; methodology, D.P.J., G.F. and A.H.; software, D.P.J.; validation, D.P.J., G.F. and A.H.; formal analysis, D.P.J.; investigation, D.P.J.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.J., G.F. and A.H.; writing—review and editing, D.P.J. and G.F.; visualization, D.P.J.; supervision, D.P.J. and G.F.; project administration, G.F.; funding acquisition, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding but was supported internally by Indiana University and the Green Earth Consortium.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All code and data necessary to reproduce this study are openly available at: GitHub Repository: https://github.com/dpjohnsoIU/PRAS_AgentBasedModeling-DataArchive (accessed on 1 September 2025). The repository includes model scripts, configuration files, and PM2.5 field data used in the analyses.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI-assisted tools were used for minor editorial assistance (i.e., spelling, grammar, language refinement).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.A.; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 2002, 287, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Villarreal-Calderon, R.; Valencia-Salazar, G.; Henríquez-Roldán, C.; Gutiérrez-Castrellón, P.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Osnaya-Brizuela, N.; Romero, L.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Solt, A.; et al. Systemic Inflammation, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Activation in Clinically Healthy Children Exposed to Air Pollutants. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008, 20, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, S.; Sarran, C.; Bezgrebelna, M.; Kidd, S. Ambient Temperature and Emergency Hospital Admissions in People Experiencing Homelessness: London, United Kingdom, 2011–2019. Am. J. Public Health 2023, 113, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, I.; Wang, A.; Paul, S.; Mora, S.; Walker, E.; Nyhan, M.; Duarte, F.; Santi, P.; Ratti, C. Big mobility data reveals hyperlocal air pollution exposure disparities in the Bronx, New York. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, J. Environmental Justice in the 15-Minute City: Assessing Air Pollution Exposure Inequalities Through Machine Learning and Spatial Network Analysis. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapizanis, D.; Karakitsios, S.; Gotti, A.; Sarigiannis, D.A. Assessing personal exposure using Agent Based Modelling informed by sensors technology. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurram, S.; Stuart, A.L.; Pinjari, A.R. Agent-based modeling to estimate exposures to urban air pollution from transportation: Exposure disparities and impacts of high-resolution data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 75, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, A.; Filippelli, G.M.; Moreno-Madriñan, M.J.; Wilson, J.S.; Wang, L.; Druschel, G.K.; Lulla, V.O. Efficacy of Low-Cost Sensor Networks at Detecting Fine-Scale Variations in Particulate Matter in Urban Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkjohn, K.K.; Gantt, B.; Clements, A.L. Development and Application of a United States wide correction for PM2.5 data collected with the PurpleAir sensor. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 4, 4617–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, B.A.; Lohmann, D.; Mitchell, K.E.; Houser, P.R.; Wood, E.F.; Schaake, J.C.; Robock, A.; Marshall, C.; Sheffield, J.; Duan, Q.; et al. Real-time and retrospective forcing in the North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS) project. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, GCP 3-1–GCP 3-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Carlson, B.E.; Lacis, A.A. How well do satellite AOD observations represent the spatial and temporal variability of PM2.5 concentration for the United States? Atmos. Environ. 2015, 102, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, K. MODIS|Terra. 610 WebDev. 2020. Available online: https://terra.nasa.gov/about/terra-instruments/modis (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Yang, Z.; Zdanski, C.; Farkas, D.; Bang, J.; Williams, H. Evaluation of Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) and PM2.5 associations for air quality assessment. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2020, 20, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.C.; Mattoo, S.; Munchak, L.A.; Remer, L.A.; Sayer, A.M.; Patadia, F.; Hsu, N.C. The Collection 6 MODIS aerosol products over land and ocean. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2013, 6, 2989–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameletti, M.; Lindgren, F.; Simpson, D.; Rue, H. Spatio-temporal modeling of particulate matter concentration through the SPDE approach. AStA Adv. Stat. Anal. 2013, 97, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Miao, C.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, G. Estimation of fine-resolution PM2. 5 concentrations using the INLA-SPDE method. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Martino, S.; Cameletti, M.; Cattani, G. Spatio-temporal modelling of PM10 daily concentrations in Italy using the SPDE approach. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 248, 118192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Land Cover Database (NLCD) 2019 Products. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/data/national-land-cover-database-nlcd-2019-products-ver-30-february-2024 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Pun, V.C.; Kazemiparkouhi, F.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Long-Term PM2.5 Exposure and Respiratory, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality in Older US Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and High Performance Computing. 2020. Available online: https://kb.iu.edu/d/apes (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In SciPy Proceedings; Curvenote: Austin, TX, USA, 2010; pp. 56–61. Available online: https://conference.scipy.org/proceedings/scipy2010/mckinney.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Hagberg, A.; Swart, P.J.; Schult, D.A. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX; Report No.: LA-UR-08-05495; LA-UR-08-5495; Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL): Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2008. Available online: https://aric.hagberg.org/papers/hagberg-2008-exploring.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Dijkstra, E.W. A Note on Two Problems in Connexion with Graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy, 1st ed.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A Note on Two Problems in Connexion with Graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analitis, A.; Katsouyanni, K.; Dimakopoulou, K.; Samoli, E.; Nikoloulopoulos, A.K.; Petasakis, Y.; Touloumi, G.; Schwartz, J.; Anderson, H.R.; Cambra, K.; et al. Short-term effects of ambient particles on cardiovascular and respiratory mortality. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass 2006, 17, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanoda, K.; Sobue, T.; Satoh, H.; Tajima, K.; Suzuki, T.; Nakatsuka, H.; Takezaki, T.; Nakayama, T.; Nitta, H.; Tanabe, K.; et al. An association between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and mortality from lung cancer and respiratory diseases in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Gogna, P.; Maquiling, A.; Parajuli, R.P.; Haque, L.; Burr, B. Comparison of hospitalization and mortality associated with short-term exposure to ambient ozone and PM2.5 in Canada. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 128683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badyda, A.J.; Grellier, J.; Dąbrowiecki, P. Ambient PM2.5 Exposure and Mortality Due to Lung Cancer and Cardiopulmonary Diseases in Polish Cities. In Respiratory Treatment and Prevention; Pokorski, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.-F.; Xu, Y.-H.; Shi, M.-H.; Lian, Y.-X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E69–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.B.; Lim, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cromar, K.; Shao, Y.; Reynolds, H.R.; Silverman, D.T.; Jones, R.R.; Park, Y.; Jerrett, M.; et al. PM2.5 air pollution and cause-specific cardiovascular disease mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).