1. Introduction

Air pollution adversely affects community health and well-being. Particulate matter (PM), especially PM

2.5, is known to increase risks for a wide range of health effects, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Furthermore, air pollution entails substantial economic and social consequences, such as reduced agricultural productivity, damages to buildings and infrastructures, and acidification of soil and water bodies, among others [

9,

10].

A variety of technologies and management practices have been developed to monitor and mitigate air pollution. Many cities and governments have established networks of fixed air quality monitoring stations to measure pollution levels. In recent years, these networks have been complemented with innovative solutions, such as low-cost stationary sensors and drones equipped with sensing devices, sometimes coordinated through artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. A comprehensive review is provided in [

11].

In addition to passive air pollution monitoring, active control measures—such as policies and regulations aimed at reducing emissions from industries, transportation, and domestic heating—have been developed. These initiatives target reductions in hourly, daily, and annual mean concentrations of the key pollutants and have proven to be effective within the European Union (EU). Over the fifteen-year period from 2005 to 2019, emissions of several pollutants declined significantly in EU Member States: particulate matter (PM

2.5, −29%), nitrogen oxides (NOx, −42%), sulfur oxides (SOx, −76%), and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs, −29%). These reductions have been achieved through strong, sector-specific EU legislation, such as the Industrial Emission Directive, the Large Combustion Plants Directive, and Euro vehicle standards [

12].

Despite these achievements, several challenges remain unsolved. The main issues can be summarized as follows: (1) in many developing countries, these measures require considerable amounts of time to become effective, as baseline pollution levels are extremely high; (2) current policies and regulations are often focused on large-scale objectives (e.g., total annual emissions reduction, or mean hourly and annual concentration decreases), since they rely on fixed air quality monitoring stations and spatial models with resolutions of several kilometers. Consequently, they fail to adequately capture small-scale spatial and temporal variability, meaning that compliance with annual limits may still coincide with local concentration peaks, which is particularly critical near sensitive receptors, such as schools, hospitals, and residential areas [

13]; (3) in some regions, law enforcement alone may be insufficient to achieve the air-quality objectives, due to unfavorable geomorphological conditions (e.g., the Po Valley in northern Italy, which is surrounded on three sides by the Alps and the Apennines). Regarding point (3), a recent study demonstrated that even when emission reductions in the Po Valley matched or exceeded those in comparable EU regions, improvements in air quality were less pronounced. This is primarily because during colder seasons, the wind, planetary boundary layer (PBL) height, and atmospheric pressure are three to five times less effective at dispersing pollutants than in regions located north of the Alps [

14].

It is therefore necessary to explore complementary technical solutions. Several studies have investigated the scavenging effect, whereby wet deposition removes pollutants from the atmosphere. It has been observed that, when it rains or snows over a city, water droplets capture air pollutants and transport them down to the ground, reducing atmospheric concentrations. For instance, on 23 February 2024 in Turin (northwestern Italy), 2.6 mm of rain reduced the daily mean PM

10 concentration from 74 µg/m

3 to 23 µg/m

3.

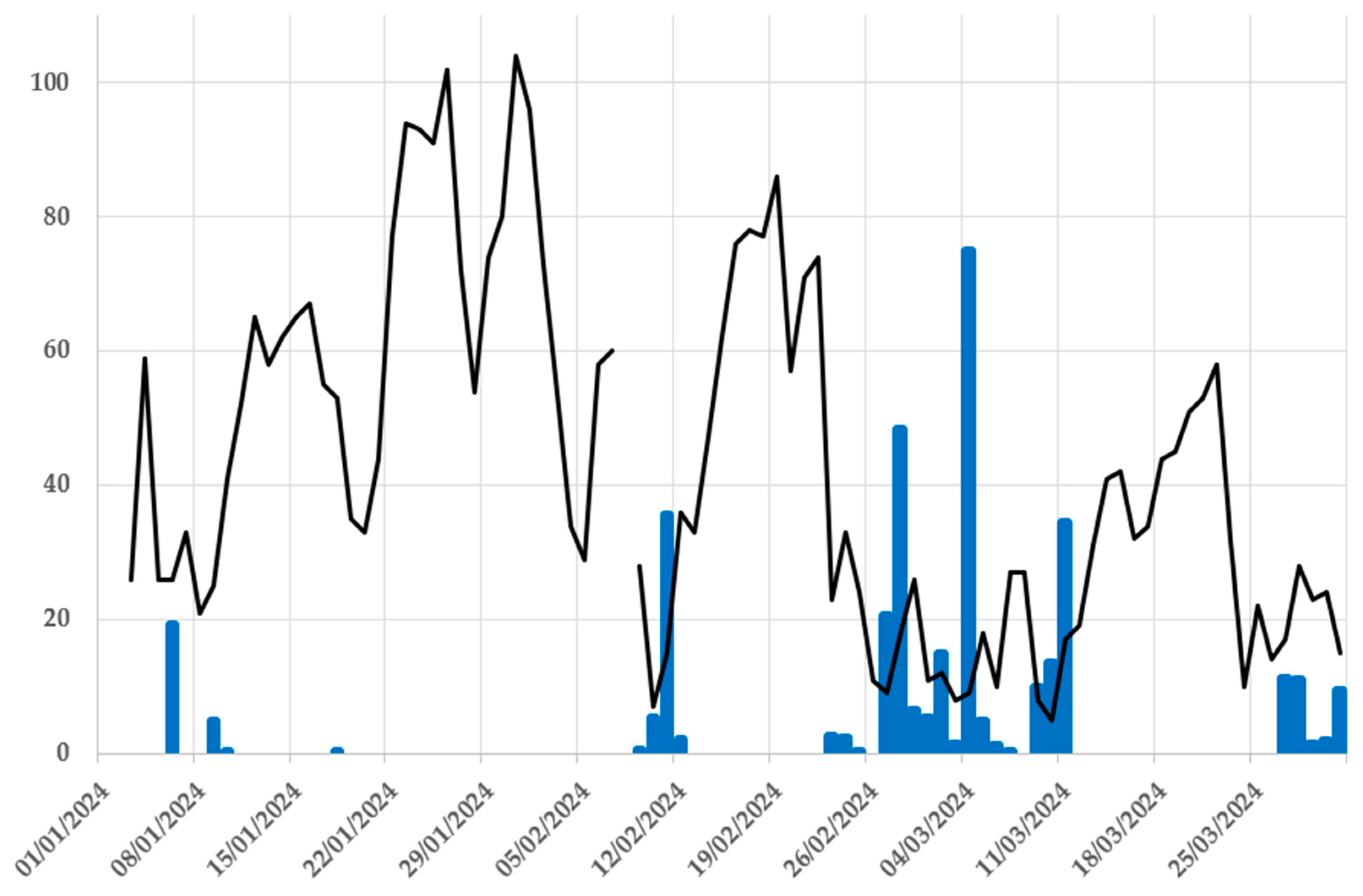

Figure 1 illustrates how rainfall events correspond to reductions in daily mean PM

10 concentrations (data from Reiss Romoli weather station and from the nearby Torino Grassi air quality station): each rainfall peak coincides with a minimum PM

10 concentration value.

The interactions between raindrops, gases, and PM have been extensively studied [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] and can be grouped into two main categories: (1) collision and coagulation processes and (2) absorption phenomena [

25]. Although similar mechanisms are widely used in industrial sectors—such as mining, construction, and waste management [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]—and in water-spraying systems used for cooling [

34,

35,

36], relatively little scientific research has focused on the deliberate use of wet deposition as a mean to reduce pollution in urban environments. It should be noted that industrial applications generally deal with larger particles (up to 100 µm), whereas urban PM is much finer, and thus more difficult to remove. Reference [

27] demonstrated that water must be atomized into droplets that are comparable in size to the target particles—specifically, 1 to 8 µm droplets—requiring high-pressure pumps and precision nozzles to effectively remove PM

2.5—PM

10.

Artificial rain has also been proposed as a mitigation strategy, as reviewed in [

25]. Roadside sprinklers have received somewhat greater attention [

37,

38,

39], and a recent work has examined spraying towers: an evolution of solar chimneys [

40]. Sprinklers installed atop tall buildings as a means to reduce PM pollution in urban areas were proposed in [

41] and thoroughly investigated in [

42]. These systems are intended as emergency interventions during severe pollution episodes and to protect sensitive populations, while awaiting the effects of long-term structural solutions. Results from a large-scale experiment in a Chinese metropolis are promising: [

42] reported reductions up to 13 µg/m

3 for PM

2.5 and 19 µg/m

3 for PM

10.

The Indian Commission for Air Quality Management in National Capital Region and Adjoining Areas has recently issued a Direction mandating the use of anti-smog cannons (ASC) in construction and demolition sites that also specifies criteria for their number, based on site area [

43]. This directive builds upon an earlier ruling by the Indian Supreme Court (13 January 2020), which examined several technical measure solutions to combat air pollution in New Delhi [

44]. These include the deployment of anti-smog cannons not only at construction sites, but also along road sections with exceptionally high particulate levels.

Ref. [

45] proposed the use of mobile sprinklers coordinated by drones equipped with sensors for similar purposes, while [

46] suggested installing fixed sprinklers in urban parks to protect trees from particulate-related damage. To the best of our knowledge, following an extensive literature review, ref. [

41,

42] remain the only scientific studies specifically devoted to the use of rooftop sprinklers to mitigate PM air pollution in urban environments.

However, several key questions remain unanswered in [

41,

42]. For example, it is unclear how many ASC units are required. Should they cover the entire urban area or only selected sensitive sites? Is it necessary to rule one ASC for every sensitive receptor? Furthermore, neither Capital Expenditures (CapEx) nor Operating Expenditures (Opex) were discussed, and no criteria were provided to determine the number of operating hours required aside from the iSpray system described in [

42].

In this study, we systematically examine the essential factors needed to design and implement a network of ASC units in a large city, to protect the sensitive receptors from severe air pollution episodes. These factors include the number of devices, CapEx and OpEx considerations, and prioritization criteria for selecting receptors when universal coverage is not feasible. Based on this analysis, we establish a generalizable methodology that is applicable to cities worldwide. We further illustrate its potential application to the city of Turin (population ≈ 850,000 inhabitants north-western Italy), which serves as a representative example of Western European urban areas. Our results demonstrate that the proposed ASC network is both technically feasible and economically sustainable for local government authorities.

2. Materials and Methods

This study investigates the potential application of water sprinkling in urban areas to reduce PM pollution. As the first step, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to assess the current state of research on this topic.

The review considered the following major scientific databases: Scopus, Science Direct, Springer Nature Link and Research Gate. Scopus is an abstract and citation database, launched by Elsevier, providing access to a vast range of the peer-reviewed scientific literature. ScienceDirect is a web-based bibliographic platform, offering access to more than 4000 academic journals and 30,000 e-books published by several smaller academic publishers. Spinger Nature Link is a research database containing more than four academic journals and almost 350,000 books, primarily published by Nature, Springer.com, BioMed Central, Scientific American, Heinrich Vogel Verlag, and SciGraph. Research Gate is a European commercial social networking platform for scientists and researchers, enabling them to share publications, collaborate, and discuss research findings.

The following keywords were used in the search queries: “Water Spraying” AND “air pollution”; “Water spraying” AND “PM removal”; “Water Spraying” AND “geoengineering”; “Water spraying” AND “scavenging”; “sprinklers” AND “scavenging”. From the retrieved results, 59 papers, conference proceedings, and book chapters were selected and reviewed in detail. Of these, 45 publications were ultimately found to be directly relevant and useful for the present research. Some of the excluded articles refer to spraying towers functioning as scrubbers; others discuss the use of water-spraying systems to reduce dust from unpaved roads in agricultural settings; others focus on the use of similar systems to limit emissions from piles of inert materials; additional articles address sprayers used as cooling systems (without providing further information beyond what had already been cited); others concern street-cleaning systems that are different from sprinklers; others examine indoor or outdoor pollution-mitigation techniques for buildings that were unrelated to rooftop sprayers; finally, some works address geoengineering methods that fell outside the scope of the present study. In essence, all articles that were not useful for reconstructing the different techniques employed, the underlying physical processes, or for informing the design of an urban ASC network, were excluded.

In

Section 4, which focuses on a possible application of the proposed method in the city of Turin (northwestern Italy), an open-access georeferenced database developed by Regione Piemonte was used to identify sensitive receptors: namely, schools and hospitals within the city [

47]. Regione Piemonte is one of the twenty administrative regions of Italy, located in the northwestern part of the Country.

The open-source software Q-Gis (version 3.34.6-Prizren) was used to process the spatial data, while the results were visualized using Arc-GIS Earth (version 2.3.0.4289 released by ESRI in December 2024). Data on the annual mean concentrations of PM

10 and the number of days exceeding PM

10 limits, as measured at air quality monitoring stations in Turin, are available online at [

48]. Rainfall data series from the Regione Piemonte meteorological station are also publicly accessible at [

49].

3. Results

In this section, we systematically discuss the key elements that are necessary to design and implement a network of ASC in large urban areas aimed at protecting sensitive receptors, such as schools, hospitals, and residential zones. The discussion covers the determination of the number of units required, CapEx, OpEx considerations, and the prioritization criteria for selecting which sensitive receptor to protect when full coverage is not feasible. Based on this analysis, a generalized methodology is proposed, which can be applied to the planning and realization of similar ASC networks in cities worldwide.

3.1. Characteristics of the Sprayers Needed

According to [

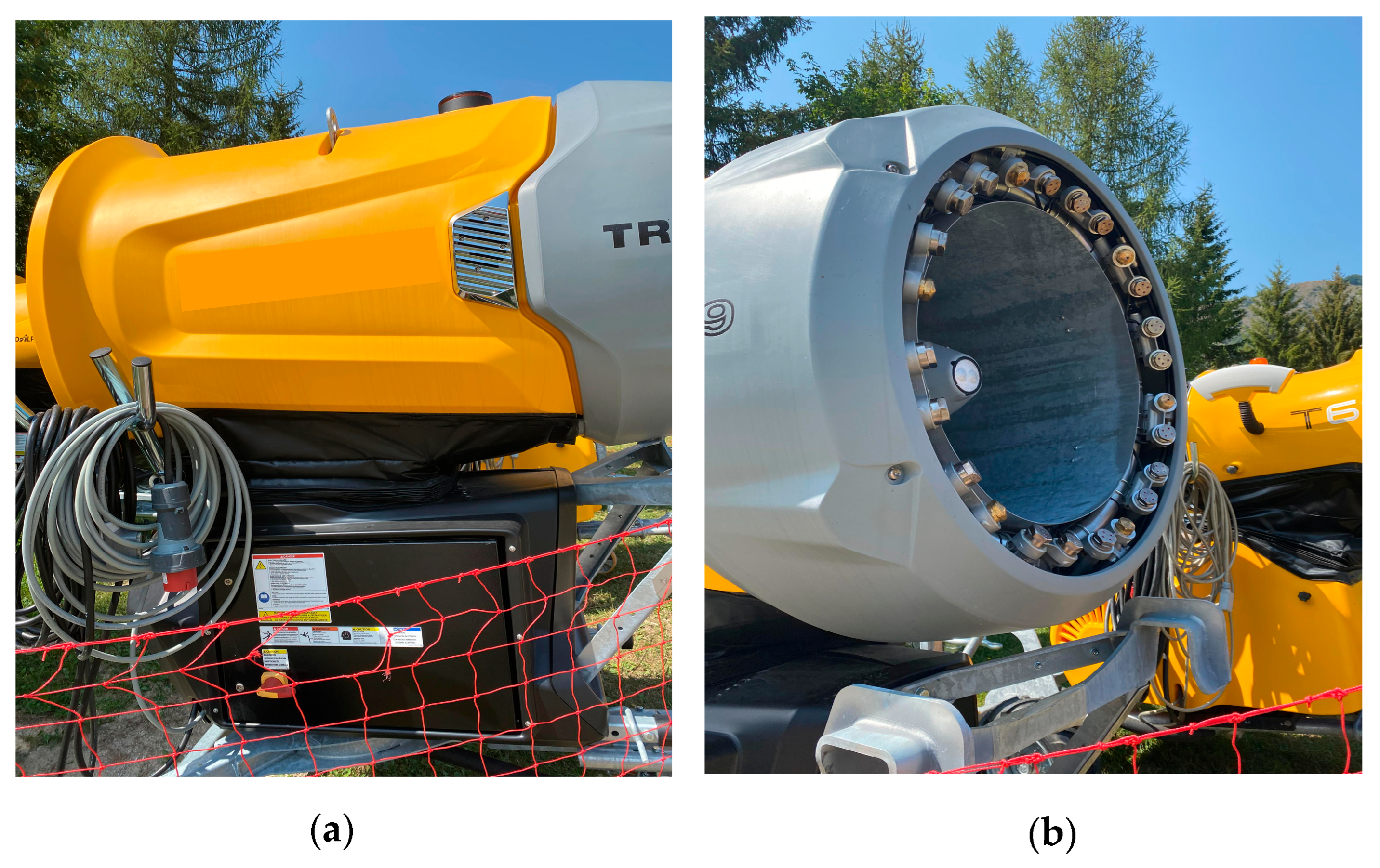

42], each sprayer consists of a high-pressure water pump, a water tank, some high-pressure resistant pipes, and a sprinkler with multiple nozzles installed on the rooftop of a building. However, that study does not provide further technical descriptions or figures illustrating the used devices. The Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC)—established by the National Capital Territory (NCT) Government of Delhi as the regulatory authority responsible for implementing water, soil and air pollution control laws—refers to the anti-smog cannons (ASC) described in [

43] as being devices that are conceptually similar to snow cannons. Snow cannons typically consist of a ring of nozzles through which pressurized water is sprayed, generating a cloud of fine water droplets that are propelled forward by a coaxial fan mounted behind the ring (see

Figure 2).

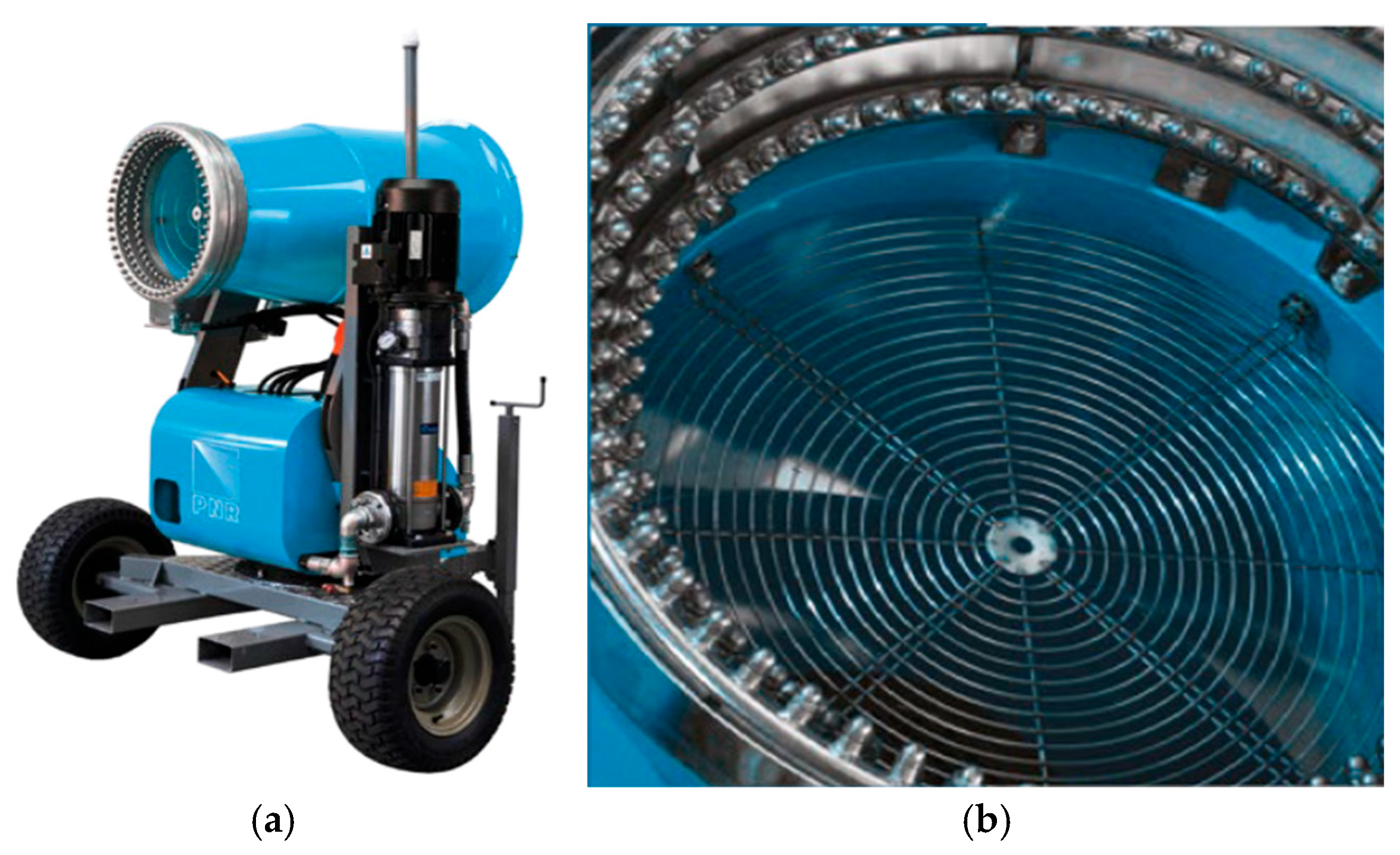

In Italy, eight manufacturers produce fog cannons, primarily for traditional applications, such as in construction sites, industrial facilities, and mining operations, but increasingly also for air quality improvement. These companies export their products worldwide, including to India and China, where they are already used for pollution control purposes. As a part of this research, all eight manufacturers were contacted to gather information on technical specifications, construction features, and cost parameters (both installation and operation). Four of them provided detailed responses. The data confirmed that fog cannons are conceptually similar to the snow cannons used for artificial snowmaking on ski slopes. The main difference lies in the water inlet pressure, which determines the size of the emitted droplets. For air quality applications, much smaller droplets are required than for snowmaking: hence, the inlet water pressure is typically 80–100 bar in fog cannons, compared to 28–69 in snow cannons. Additionally, the number of nozzle rings differs between the two systems. While snow cannons usually employ a single nozzle ring, fog cannons are often equipped with two, three, or even four concentric nozzle rings, depending on the intended application and the distance over which the water droplet cloud must be projected (see

Figure 3).

3.2. Criteria to Determine the Number of Sprayers Needed

According to [

42], a single nozzle can produce an aerosol cloud extending 3–5 m in length, which can disperse up to 30 m under calm conditions and up to 100 m in the presence of wind. These values are consistent with the technical specifications provided by Italian fog cannon manufacturers, whose products can project a cloud of water droplets between 10 and 150 m, depending on the model. Intermediate models are also available, with effective reach values of about 40 m from the ASC axis, as well as 50, 60, 70, 90, or 100–110 m. For the purposes of this study, an ASC model that is capable of spreading the water droplet cloud up to 100 m from the cannon axis is considered to be a reasonable design assumption. The area covered by a single ASC is then 31,416 m

2. This choice represents a balanced compromise to minimize the number of devices required and the overall capital expenditure (CapEx) of the network. In recent days—specifically on 18 November 2025—a new Air Quality Plan for the city of New Delhi was approved (a brief description can be found in [

51]), which foresees the installation of a network of 250–600 ASCs, each capable of dispersing the water-droplet cloud over a distance of 30–50 m and to cover an area of 30,000 m

2. It appears that the Environmental Department of New Delhi has assumed that an ASC with an effective range of 30–50 m can disperse the water-droplet cloud up to 100 m, given that the estimated coverage area (30,000 m

2) corresponds to a circular area with about a 100 m radius. As a consequence, our assumption to consider an ASC model that is capable of spreading the water droplet cloud up to 100 m may lead to an overestimation of the required power and, consequently, of the associated installation costs compared to the Indian project. We therefore consider it necessary to install a pilot ASC to empirically assess the appropriate unit size before proceeding with large-scale deployment. At the end of the present section, we will briefly discuss our proposal, subject to future research.

In [

42], the authors reported the use of 55 sprayers within a research area measuring 18 × 24 km. However, the study does not specify the criteria used to determine this number; it remains unclear whether the selection was based on the distribution of sensitive receptors, or on a spatial density criterion (e.g., a fixed number of sprayers per square km).

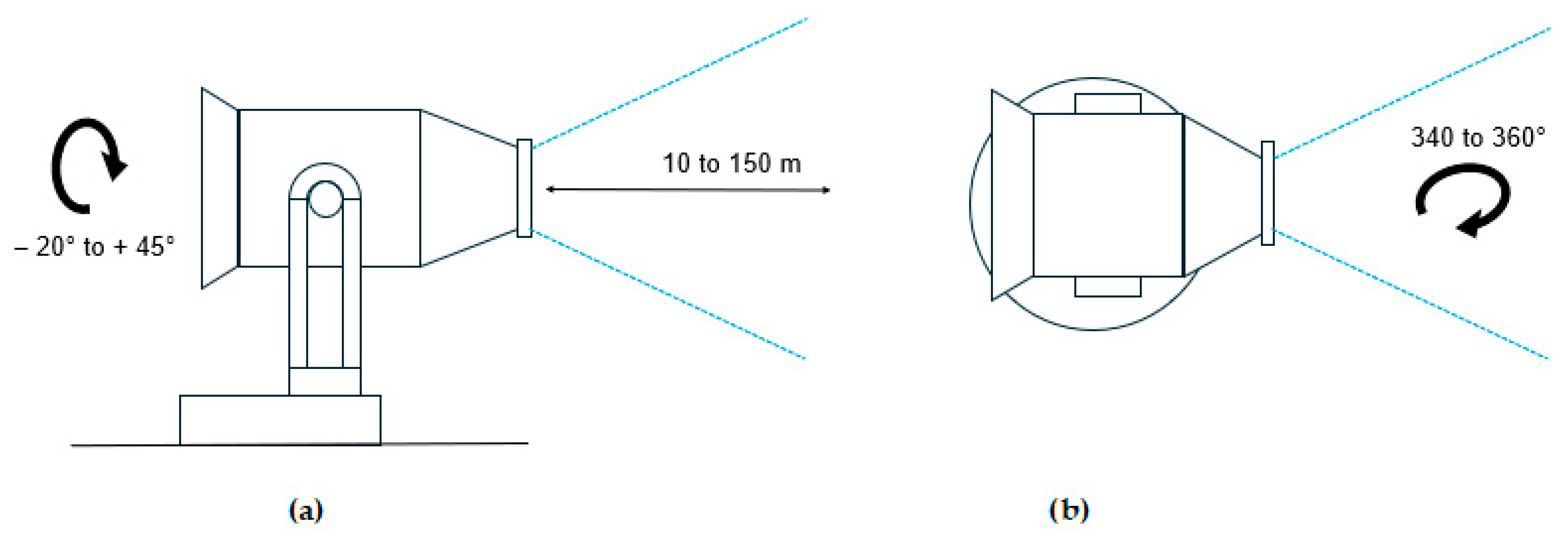

When defining the number of ASC units needed for a specific area, the most direct approach would be to attempt complete spatial coverage. Considering that the aerosol cloud extends up to 100 m, and assuming that each ASC can rotate 360° around its vertical axis (see

Figure 4), each sprayer can be considered to cover a circular area with a radius of 100 m. The corresponding covered area per sprayer is therefore approximately 0.03 km

2, implying a theoretical density of 32 sprayers per square kilometer. Applying this density to the 18 × 24 km area described in [

42] would require 13,824 sprayers to achieve full coverage. This calculation clearly demonstrates that the complete area coverage is not a feasible strategy, due to the excessive number of devices and the unrealistically high investment cost it would entail.

An alternative approach consists of applying a spatial density criterion: that is, installing a specific number of sprayers per square kilometer. In [

42], the authors used 55 sprayers in a research area of 18 × 24 km, corresponding to a density of approximately 0.13 sprayers per km

2. However, as previously discussed, ref. [

42] does not clarify the rationale or criteria used to determine this number. Ref. [

43] introduces a spatial density criterion, applied to construction and demolition sites, which can, in principle, be extended to more general air quality control contexts: the directive specifies at least one ASC for areas between 5000 and 10,000 square meters, at least two for areas between 10,001 and 15,000 square meters, at least three for areas between 15,001 and 20,000 and at least four for areas exceeding 20,000 square meters. This corresponds roughly to 1 ASC per 7500 m

2, which, when extrapolated to the 18 × 24 km research area in [

42], would imply the installation of about 57,600 sprayers. It is therefore evident that this approach is not feasible for large urban areas, due to the prohibitive number of devices required.

Since full surface coverage is impractical, a more realistic approach is to assign one sprayer per sensitive receptor. However, in densely built urban environments—typical of Western European cities—sensitive receptors are often located close to one another. Installing a dedicated ASC for each receptor would thus be redundant and economically inefficient (see

Figure 5). A case-by-case optimization is therefore necessary, identifying the minimum number of sprinklers required to cover all sensitive receptors. In the case study in

Section 4, which refers to the city of Turin in northwestern Italy, the analysis resulted in 324 ASCs, which was sufficient to cover 656 sensitive targets (schools and hospitals) within the municipal borders.

Although this optimized number is significantly lower than that obtained using other criteria, it remains financially demanding, due to the high cost of each ASC. Depending on the size and economic capacity of the city under examination, it may be necessary to further reduce the total number by applying a priority-based classification of sensitive receptors. The chosen rule is vulnerability of the sensitive receptor. So, they were divided into four classes, where the highest risk (Class 1) corresponds to the greatest vulnerability of the sensitive receptor (hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes), and progressively lower risk classes correspond to decreasing vulnerability (first children under 6 years of age—class 2, then those aged 6 to 11—class 3, and finally young people aged 12 to 25—class 4). The classes are, then, as follows: Class 1 (highest priority): hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes; Class 2: daycare centers and preschools; Class 3: elementary schools; Class 4: middle schools, high schools, and universities.

Section 4 demonstrates how applying this prioritization scheme to an Italian city substantially reduces the total number of sensitive receptors considered for protection.

A further reduction may be achieved by excluding receptors located far from major traffic routes or surrounded by extensive greenery, where pollution levels are generally lower.

Finally, it may be advisable to install a pilot plant, to evaluate actual water consumption within the operational range presented in

Section 3.3, and to verify whether local meteorological conditions produce the same droplet dispersion pattern observed in [

42]. This experimental phase represents an essential step for accurately determining both the number of sprayers required and the operating power needed to achieve the desired droplet cloud length and spatial coverage.

3.3. Some Indication of Installation (CapEx) and Operating (OpEx) Costs

Regarding installation costs, ref. [

42] provides no specific information. However, Italian ASC manufacturers report comparable price ranges, typically between EUR 10,000 and EUR 45–50,000 per unit. The installation cost of EUR 10,000 corresponds to the ASC that is capable of dispersing the water-droplet cloud over a distance of 30 m and the installation cost of EUR 45–50,000 corresponds to the one capable of a distance of 100–110 m. Intermediate distances would correspond to intermediate costs between these two extremes. The main factor influencing cost is the need for larger fans and higher-pressure pumps.

With respect to operating costs, ref. [

42] indicates an energy consumption of 5 kWh/hour and a water flow rate of 0.6 m

3/h (equivalent to 0.17 L/s) for a single ASC. In [

51], each ASC is indicated to have a water consumption ranging from 0.66 to 4.17 L/s. Italian manufacturers are broadly consistent with these values, reporting electric power consumption ranging from 0.8 kWh for units with a 10 m range up to 22 kWh for units capable of reaching 80–90 m. Therefore, the 30 m range mentioned in [

42] corresponds with an average consumption of approximately 6.1 kWh/h, which is very close to the value reported by the authors. As for water consumption, Italian manufacturers indicate slightly higher values, varying between 0.25 and 2.53 L/s. As already stated before, anti-smog cannons (ASCs) are capable of dispersing water-droplet clouds over distances ranging from approximately 10 to 150 m. Intermediate models are also available, with effective reach values of about 30 m from the ASC axis, as well as 50, 60, 70, 90, or 100–110 m. Each model operates at a distinct water pressure, which consequently results in different consumption rates. Smaller units are equipped with only one nozzle ring, whereas larger systems feature four; intermediate sizes typically employ three. The total number of active nozzles likewise affects the overall water consumption, because it is typically possible to activate one or more nozzle rings independently, depending on the required spraying intensity.

Based on these technical specifications, and considering the average cost of water and electricity in the examined region, it is possible to estimate the hourly and daily operating cost of a single ASC. To obtain a realistic estimate of the total OpEx of an entire network, three additional parameters must be defined: (1) the number of hours or days the system is expected to operate, (2) the already-mentioned total number of sprayers required to achieve the desired level of air quality improvement (see

Section 3.2), and (3) the maintenance costs per unit and of the whole network.

When it comes to point (3), annual maintenance costs for simple machinery (e.g., small systems, basic engines, pumps, and fans) typically range from 1% to 3% of their CapEx; medium-scale industrial equipment (such as compressors, boilers, HVAC systems, and standard machine tools) generally requires 3% to 6%, while complex machinery (including automated systems, robotics, and advanced CNC equipment) falls between 6% and 10%. When an ASC is operated only for a limited number of days per year (see the case study in

Section 4), its maintenance requirements lie in the lower portion of the typical ranges—approximately 3% to 5%. Because wear on the high-pressure pump is minimal, nozzle degradation is primarily a function of spraying hours and the fan accumulates comparatively few operational hours. Environmental exposure (water, dust, freezing conditions) remains a factor, though a limited one. For prudence, we adopted an annual maintenance cost that was equal to 5% of the installation cost (i.e., approximately EUR 2250–2500 per unit per year).

3.4. Criteria to Determine the Number of Days the Sprayers Should Be Turned on

The pollutant targeted by this anti-smog cannon system is particulate matter (PM

2.5 and PM

10). This pollutant is generally not linked to acute health effects; rather, its impacts are chronic, arising from exposure to certain concentrations over long periods of time. For this reason, the WHO guidelines (and, consequently, the European Directives [

52,

53]) do not set hourly limit values for PM

2.5 and PM

10 for the protection of human health. Instead, they only establish daily and annual average limits, while allowing for a certain number of days per year in which the daily mean concentration may exceed the prescribed limit.

In recent years, the maximum number of exceedances allowed by the legislation has been surpassed at several air quality monitoring stations in Western Europe. Our objective is therefore to ensure that the number of exceedances returns to a value equal to or below the maximum permitted by the European Directives. So, the number of days exceeding the PM

10 daily limit value of 50 µg/m

3 can serve as a basis for estimating how many days the ASC should operate. In particular, when the number of exceedances surpasses the 35 days per year that are currently permitted by [

52]—a threshold that will be reduced to 18 days by 1 January 2030, according to [

53]—the difference between the observed exceedances and the permitted maximum can be interpreted as the number of days requiring ASC activation.

However, when multiple air quality monitoring stations are available within the same urban area, with each recording different pollutions patterns, over time, additional considerations are required. A suitable approach involves analyzing data from several consecutive years of air quality measurements, while excluding anomalous years, e.g., 2020, which was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, or years characterized by exceptional drought and unusually low rainfall. Among the remaining representative years, it is advisable to identify the worst-performing year in terms of PM

10 exceedances and then compute the average differences (between observed exceedances and the permitted maximum) across all air quality stations. This procedure yields a mean number of exceedance days beyond the legally allowed threshold of 35 per year (as defined by [

52]), which can be used as a reasonable estimate of the number of days per year during which the ASC network should operate.

The analysis does not focus on intra-day concentration variations or short-term peaks. In any case, the measurements from the air quality monitoring network could be available in real time, which means that the activation of the system (or of a subset of it) could be linked to rising concentrations beyond a given threshold, and its deactivation could follow accordingly.

In this sense, the indication regarding the number of activation days should be understood as a maximum number of days (and therefore hours) of operation, within which further refinements may be implemented. This maximum number of operating hours corresponds to the maximum cost that needs to be considered and upon which the feasibility of the system must be evaluated. Lower activation times (in terms of total hours) will naturally result in lower operational costs, which would automatically be more manageable.

3.5. Some Considerations on the Scalability, Sensitivity, and Environmental Sustainability of the System

The ASC network is inherently modular and scalable, as each individual ASC can be operated independently from the others and can be added or removed according to changing protection needs for the sensitive receptors.

Regarding the scenario–sensitivity analysis, in this work, we started from the number of ASCs, because this value corresponds to the number of sensitive receptors protected by the system (based on the assumption that if one or more receptors are equipped with an ASC, then they are better-protected from PM pollution because the air quality limits are complied with). This number was then determined on the basis of a risk-class classification, where the highest risk class (Class 1) corresponds to the greatest vulnerability of the sensitive receptor (hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes), and progressively lower risk classes correspond to decreasing vulnerability (first, children under 6 years of age, then those aged 6 to 11, and finally, young people aged 12 to 25). In the following case study, we found that only the first class—or at most, the first two classes—can be covered within an affordable framework, so we constructed two scenarios: Scenario (1), which included the coverage of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes, and was further subdivided into two sub-scenarios corresponding to the extreme water-consumption values reported in

Section 3.3; and Scenario (2), in which nursery schools and kindergartens are added to the coverage, which was also subdivided into two sub-scenarios corresponding to the extreme water-consumption values. The four resulting sub-scenarios captured a wide range of intermediate conditions.

As it comes to the environmental sustainability of the ASCs’ network, the energy consumption can be offset through the use of photovoltaic systems installed on the roofs of the same buildings hosting the ASC units. Concerning water consumption, the implementation of the ASC network could be accompanied by the installation of a rainwater harvesting system. Alternatively, as originally envisaged, the network would be supplied with municipal water. According to [

51], each ASC has a water consumption ranging from 0.66 to 4.17 L/s to cover an area of 30,000 m

2, which is comparable to, or even higher than, the values reported in

Section 3.2. The new Air Quality Plan for the city of New Delhi also estimates a total water demand of 2500–9000 m

3 day

−1, corresponding to 0.12–0.17 L s

−1 per unit, which is lower than the values indicated in

Section 3.2. It is therefore plausible that the values we previously reported are overestimated, further reinforcing the importance of installing a pilot unit prior to the full-scale deployment of the network.

Finally, with respect to the possible need to dispose of contaminated wastewater, we believe that this situation is unlikely to occur. The water is atomized into very small droplets (1–8 µm), which subsequently incorporate airborne particles and aggregate, increasing in size, but still reach the ground as mist, rather than rainfall. Pollutants are therefore brought to the ground without generating any wastewater flow.

4. A Case Study: The Application of the Method to a Large Urban Area in Italy

In this section, we examine the application of the proposed methodology to the city of Turin, located in northwestern Italy and home to approximately 850,000 inhabitants. Turin serves as a representative case study for other Western European cities, facing similar air quality challenges. The sequence of operations required to determine the installation (CapEx) and operating (OpEx) costs of an ASC network is essentially the same across all European countries. The primary differences concern the unit prices of electricity and water, which naturally influence the final OpEx. However, the variability observed among European nations is not substantial and is generally favorable when compared with Italy, where electricity costs tend to be higher. Moreover, urban areas of comparable size in Western European countries typically operate with similar municipal budgets. Consequently, the considerations developed for the case of Turin can be reasonably extended to urban areas of similar scale throughout the EU.

No attempt was made to achieve full surface coverage of the municipal area, as the number of required ASCs would be excessively high. The anthropized portion—approximately half of the municipal area, excluding green and uninhabited zones (see

Figure 7)—amounts to 114 km

2. Considering that each ASC covers 0.0314 km

2, a total of 3625 units would be necessary for full coverage. For similar reasons, the spatial density criterion proposed by [

43] (one every 7500 m

2) was not applied, as it would require around 15,200 ASCs. Likewise, the criterion from [

42] was disregarded, due to the lack of a clear methodological justification. Following the optimization procedure of

Section 3.2, we adopt a target-based approach, aiming to protect each sensitive receptor while minimizing the total number of ASCs. In an area where receptors are spatially clustered, a single sprayer was designed to cover two or three targets simultaneously (see

Figure 5).

The final configuration required 324 ASCs to cover all the 656 sensitive receptors within the municipal borders of Turin, corresponding to approximately 50% of the total. These receptors included 635 schools and 21 hospitals and nursing homes, according to [

47]. Sensitive receptors located in the green hills that are east of the city were excluded, as air quality in that area is consistently higher (see

Figure 7). Their exclusion has a negligible impact on the overall conclusions, due to their limited number, as the required number of ASCs decreased from 331 to 324.

According to the CapEx estimates in

Section 3.3 (the two extreme unit costs provided by manufacturers for the required cannon are EUR 45,000 and EUR 50,000), the total installation cost for 324 ASCs ranges from EUR 14,580,000 and EUR 16,200,000: a substantial investment that would likely exceed the local government authorities’ budget capacity. Consequently, it becomes necessary to apply the priority criteria described in

Section 3.2, which classifies receptors according to their vulnerability and exposure risk.

Table 1 presents the distribution of Turin’s sensitive receptors across the four defined risk classes and the corresponding CapEx required, to ensure full coverage of each category.

Table 2 summarizes the cumulative investment required for the combination of classes (i.e., class 1, class 1 + 2, class 1 + 2 + 3, etc.), including the number of ASCs needed and the related CapEx.

The most financially feasible scenarios are the implementation of class 1 only (hospital and nursing homes) or classes 1 + 2 (adding preschools and daycare centers). These options require between 22 and 164 ASC, with a total CapEx ranging from EUR 990,000 to EUR 8,180,000. Further assessments of economic feasibility are discussed in Section Financing Framework for the ASCs Network Within the Regional Air Quality Strategy.

As reported by Italian ASC manufacturers, the electricity consumption of each sprayer is approximately 22 kWh per hour, while water consumption ranges from 0.9 to 9.1 m

3/h, depending on the nozzle configuration and pressure settings. Using these data and the average water and electricity tariffs in northwestern Italy (according to [

54]), we estimated the hourly and daily operational cost of the system for two extreme scenarios: (1) scenario 1—22 ASCs (covering only hospitals and nursing homes); (2) 164 ASCs (covering hospitals and nursing homes, preschools and primary schools). The resulting costs are reported in

Table 3. In [

50], the Environmental Department of New Delhi is said to estimate water consumption between 0.66 and 4.17 L/s per unit, which is comparable to, or even higher than, the values reported in

Section 3.2. The plan also estimates a total water demand of 2500–9000 m

3 day

−1, corresponding to a water consumption of 0.12–0.17 L/s per unit, which is much lower than the 0.25–2.53 L s

−1 range indicated in

Section 3.2. This discrepancy is likely attributable to the fact that the ASC network does not operate continuously. Therefore, our estimate should be considered to be a conservative upper bound, as the network is unlikely to function 24 h per day.

To estimate the annual operating time, we referred to the number of days exceeding the PM

10 daily limit value of 50 µg/m

3. In compliance with the EU directive [

52], which currently permits 35 exceedance days per year (to be reduced to 18 by 1 January 2030, according to [

53]), the difference between the observed and permitted exceedances was considered to be the number of operational days for the ASC network.

Turin has five fixed air quality monitoring stations, each reflecting district environmental conditions (Ref. [

48]; see

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). The Lingotto and Rubino stations monitor the background air quality, while Consolata, Grassi, and Rebaudengo record traffic-related air quality conditions; consequently, the latter typically show higher PM

10 concentrations and a greater number of exceedance days. Data from the past five years were analyzed, excluding 2020 (due to the COVID-19 lockdown effects of pandemic) and 2022, which was a year of exceptional drought and low rainfall. Among the remaining years, 2021 was identified as the worst case, with an average of 60.4 exceeding 50 µg/m

3, rounded to 61, across the five stations (See

Table 4 and

Table 5). Given the legal threshold of 35 days, the sprayers should operate for 26 days per year.

Based on the hourly and daily cost estimates presented in

Table 3, the resulting annual operating costs for the 22 and 164 ASCs (Scenario 1 and 2) are summarized in

Table 6, together with the annual unit maintenance costs.

As shown in

Table 2 and

Table 6, the use of ASCs to mitigate air pollution episodes in Turin appears to be technically viable and economically sustainable, within the range of 22 to 164 sprayers. Nevertheless, the wide variation in estimated installation and operating costs highlights the need for empirical validation. We therefore propose the installation of a pilot ASC at ITTS “Carlo Grassi” High School, located in the northwestern sector of the city. Although it belongs to risk class 4, it lies adjacent to the “Torino Grassi” air quality monitoring station (see

Figure 9), allowing for a direct evaluation of the ASC’s effectiveness without additional instrumentation. Furthermore, the “Ignazio Vian” Middle School, located immediately south of the site, could also be covered by the same sprayer, thus testing the possibility of multi-receptor coverage by a single ASC. The installation and performance monitoring of this pilot system will be the subject of future research, aimed at refining both the cost–benefit analysis and the design parameters (e.g., spray range, water droplets dynamics, and meteorological dispersion effects) that are necessary to optimize full-scale deployment.

Financing Framework for the ASCs Network Within the Regional Air Quality Strategy

The financing of a water-based ASC system—designed to replicate natural wet deposition processes and thereby reduce airborne pollutant concentrations in urban environments—can be effectively integrated into the broader strategic framework of the Regional Air Quality Plan of Regione Piemonte [

55]. This plan, which was developed in response to the persistent and severe air quality issues affecting the Po Valley Basin, one of Europe’s most polluted areas, seeks to combine structural, infrastructural, and emergency interventions to achieve both immediate and long-term improvements in environmental conditions and public health.

Among the actions that future plans are going to outline, additional emergency-oriented interventions may be supported through dedicated funding streams that are accessible to Regione Piemonte, rather than through the mobility-related measures that are already activated. In particular, Regione Piemonte may draw on national programs managed by the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security (MASE), European Regional Development Fund (ERDF/FESR) resources allocated to environmental quality and climate adaptation, and complementary instruments such as the Development and Cohesion Fund (DCF). Further opportunities may arise from European programs that specifically target the environment and climate, including LIFE and Horizon Europe calls for pilot and demonstrative actions.

These financial instruments, which are already used by Regione Piemonte for other air-quality interventions, offer a coherent framework for supporting innovative, rapid-response measures that are designed to reduce population exposure during acute pollution episodes. Their alignment with both regional air-quality priorities and broader national and European funding objectives strengthens the feasibility and strategic integration of ASC-based emergency actions within the Regional Air Quality Plan [

55].

Within this financial and regulatory context, the deployment of ASC networks is conceived as an innovative and complementary emergency measure. Unlike major infrastructural projects that require extensive planning and prolonged implementation timelines, ASCs’ networks offer an immediate, flexible response that is capable of temporarily reducing pollutant concentrations during acute air quality episodes. Their application is particularly strategic for safeguarding vulnerable population groups, including children, elderly individuals, and persons with pre-existing respiratory conditions, thus directly contributing to the protection goals defined in the Regional Air Quality Plan.

The inclusion of ASC networks among the eligible interventions reflects a forward-looking approach to urban environmental management, integrating short-term mitigation actions with long-term structural transformations. It exemplifies the capacity of the regional authorities to develop adaptive governance models that combine strategic planning instruments, operational flexibility, and the effective use of European structural funds. Ultimately, financing these represents a tangible example of how multi-level governance, informed by European cohesion policy mechanisms, can enable cities and regions to address complex environmental challenges through integrated, dynamic, and resilient responses.

5. Conclusions

ASCs installed on the rooftops of urban buildings can serve as an effective measure to reduce PM pollution in urban areas, and to protect sensitive population groups—such as children and hospitalized individuals—during episodes of elevated PM concentrations. Their deployment is particularly valuable in contexts where achieving air quality standards is challenging due to unfavorable geomorphological or meteorological conditions, or when meeting daily and annual limit values does not guarantee adequate air quality at finer spatial and temporal scales. Early experimental findings are promising: in a Chinese metropolis, reductions of up to 13 µg/m3 for PM2.5 and 19 µg/m3 for PM10 were observed following the application of the sprayers’ system.

The potential application of ASCs in the Po Valley (Italy) is especially noteworthy. The region, enclosed on three sides by the Alps and the Apennines, systematically struggles to meet regulatory thresholds for several pollutants. A recent study demonstrated that emission reductions that are comparable to, or greater than, those implemented in other European regions yield significantly smaller improvements in the Po Valley. During the cold seasons, reduced wind speeds, lower PBL heights, and higher atmospheric stability make the dispersion and dilution of pollutants three to five times less efficient than in the north of the Alps [

14].

Despite these considerations, the scientific literature on ASC in urban environments remains extremely limited. To the best of our knowledge, based on an extensive and systematic review, only two studies—[

41,

42]—directly examine the use of rooftop water sprinklers to reduce PM concentrations in cities. However, crucial questions remain unsolved in these works. For example, it is unclear how many ASCs are required in a given urban area: should one be installed for each sensitive receptor or should a spatial density criterion, such as the one proposed in [

43], be adopted? Furthermore, neither study provides a detailed discussion of Capital Expenditures (CapEx) and Operating Expenditures (Opex) or the criteria needed to determine the number of operating hours required, aside from the proprietary iSpray system described in [

42].

In this study, we systematically analyze the fundamental elements required to design and implement an ASC network in a large urban area, with the objective of protecting sensitive receptors. These elements include the definition of the number of sprayers, CapEx and OpEx evaluations, and the establishment of priority criteria for the protection of specific receptors in cases where full coverage is not feasible. On this basis, we outline a replicable methodological framework that could be applied to any city worldwide. We also investigate the conditions for implementing this method in the city of Turin (Italy)—home to approximately 850,000 inhabitants—as a representative case study for Western European urban areas.

Our findings suggest that the adoption of ASCs for emergency pollution mitigation is technically feasible, and that both installation and operating costs could be considered to be affordable by local government authorities, regardless of whether the intervention targets only hospitals or also includes preschools and primary schools. However, the range of possible annual operating costs remains substantial—from EUR 183,000 for 22 sprayers in a low water-consumption configuration to EUR 2,650,000 for 164 sprayers in a high water-consumption scenario. For this reason, we recommend the installation of a pilot sprayer with a single sensitive receptor. This preliminary step would support a more accurate assessment of actual water and energy consumption, ensuring that the final cost estimates fall within realistic bounds. The proposed pilot installation is located near an existing air quality monitoring station, thus allowing for the evaluation of ASC effectiveness without the need for additional monitoring equipment. Furthermore, the pilot system will provide essential information on whether the meteorological conditions of Turin reproduce the same droplet dispersion pattern observed in [

42]: a key factor in determining the number of sprayers required and their operational specifications (e.g., power, droplet cloud range). The installation, operation, and evaluation of this pilot ASC will be the focus of future research.