Abstract

Field-evolved resistance of Helicoverpa zea to crops expressing Cry insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is widespread across the United States. To comparatively evaluate physiological factors associated with Bt susceptibility, we analyzed two laboratory strains (Benzon and SIMRU) and one field colony obtained from a commercial corn field near Pickens, Arkansas. Biochemical assays of larval midgut extracts showed that Pickens exhibited significantly altered activities of chymotrypsin-like proteases, aminopeptidase N (APN), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) compared with the SIMRU or Benzon colonies, with differences varying by larval instar. In contrast, trypsin-like protease activities did not differ significantly among the three colonies. Gene expression analyses of ten serine protease genes and seven candidate Cry receptor genes (including cadherin, ATP-binding cassette family C2, ALP, and four APN genes) revealed significant transcriptional differences in the Pickens relative to the lab colonies. Collectively, these results suggest that chymotrypsin-like proteases may play an important role in the activation of Cry toxins in H. zea. Altered chymotrypsin and APN activities, together with differential gene expressions in the Pickens population, likely contribute to reduced Bt susceptibility. The biochemical and molecular differences provide insight into potential physiological factors underlying reduced Bt susceptibility and may inform future Bt resistance monitoring and management strategies.

1. Introduction

The corn earworm or cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa zea Boddie; Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is a major agricultural pest in the United States, capable of causing substantial damage to economically important crops such as cotton, corn, and soybean [1,2]. Since the commercial introduction of genetically engineered crops expressing insecticidal protein genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Berliner in 1996, Bt crops played a critical role in managing lepidopteran pests, including H. zea [3,4]. These crops have significantly reduced reliance on conventional insecticides, enhanced biological control by natural enemies, improved farm profitability, and lowered environmental and health risks [5,6,7,8,9]. By 2019, Bt crops were planted in over 109 million hectares across 27 countries [10]. However, the evolution of resistance to Bt toxins in the target insect population reduces the advantages of transgenic crops and threatens the long-term sustainability of these benefits [11,12,13]. Documented cases of field-evolved or “practical” resistance increased from 3 in 2005 to 26 by 2020, involving 11 pest species and 9 different crystalline (Cry) toxins [13]. In the United States, the management of H. zea has proven particularly challenging due to the rapid evolution of practical resistance to 5 different Cry toxins used in Bt crops (Cry1Ab, Cry1A.105, Cry1Ac, Cry1Fa, and Cry2Ab) within just 13 years of commercialization [13]. Several factors likely contributed to this resistance, including inherent tolerance to some toxins [14] and Bt corn varieties expressing Cry toxins that fail to meet the high-dose requirement essential for effective resistance management [15].

Cry proteins are pore-forming toxins. After ingestion, Cry protoxins are solubilized and activated by proteases in the larval midgut, and after crossing the peritrophic matrix, the activated toxins bind to specific receptors on the brush border membrane of midgut epithelial cells [16,17]. Several Cry toxin receptors have been identified, including cadherins, aminopeptidases (APNs), alkaline phosphatases (ALPs), and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters [17]. Effective receptor binding is conducive to pore formation, which causes ion imbalance, cell swelling, lysis, midgut leakage, and ultimately insect death [18]. In H. zea and other lepidopteran pests, resistance to Cry toxins generally arises through two primary mechanisms: reduced midgut serine protease activity hindering protoxin activation, and alterations in midgut receptors that reduce or prevent effective toxin binding [19,20]. For example, resistance to Cry1Ac in H. zea was associated with altered proteolytic processing in the midgut [21]. Practical resistance to Bt corn expressing Cry proteins has also been associated with mutations in a cadherin gene [22], and amplification of a trypsin gene cluster [23]. While not considered a major resistance pathway to Cry toxins, enzymatic detoxification has also been reported to impact susceptibility to Bt toxins [24].

The objective of this study was to comparatively evaluate physiological factors associated with Bt susceptibility in H. zea using two laboratory strains (Benzon and SIMRU) and one field-collected population obtained from a commercial corn field near Pickens, Arkansas. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether variation in midgut protease activity and putative Cry toxin binding proteins correlates with differences in Bt susceptibility among three populations. To address this objective, we examined the enzymatic activities of trypsin- and chymotrypsin-like serine proteases, as well as ALP and APN in midgut extracts from multiple larval instars across three populations. To further identify physiological factors potentially contributing to reduced Bt susceptibility in the field population, we conducted transcriptional analyses of serine proteases genes (four trypsin and six chymotrypsin), candidate Bt receptor genes (cadherin, ABCC2, ALP, and four APN genes), and four detoxification genes (esterase, Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), CYP6B8, and CYP6B28) in 3rd instar larvae across three populations. Collectively, these biochemical and transcriptional assessments provide a comparative framework for identifying the physiological correlation of Bt susceptibility in H. zea and for informing future mechanistic and resistance monitoring studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Colonies

A laboratory reference H. zea colony has been consecutively maintained for over 500 generations at the USDA-ARS Southern Insect Management Research Unit (SIMRU) in Stoneville (MS) since 1971. Another reference H. zea colony was purchased from Benzon Research Inc. (Carlisle, PA, USA). Both SIMRU and Benzon colonies are considered susceptible to Cry toxins and have been widely used in Bt susceptibility studies [2,25]. A field-derived H. zea colony was collected in June 2024 from a commercial corn field near Pickens (AR). Previous research has shown that field colonies frequently display reduced Bt susceptibility to Cry toxins [1,2]. All colonies were reared in the laboratory using an artificial diet containing soy and wheat germ [26], following the procedures described previously [27]. All colonies were reared under laboratory conditions (26 ± 1 °C, 30 ± 5% relative humidity, 14 h light:10 h dark).

2.2. Insecticides and Chemicals

All the reagents, including Triton X-100, Nα-benzoyl-DL-arginine 4-nitroanilide hydrochloride (BApNA), N-succinyl-alanine-alanine-proline-phenylalanine-p-nitroanilide (SAAPFpNA), leucine-p-nitroanilide (LpNA), and p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium (pNPP), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Bradford protein assay kit with a bovine serum albumin standard was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3. Midgut Extracts

Midgut tissues were dissected from 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar H. zea larvae collected from three different populations: SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens. For each developmental stage, midgut samples were pooled as follows: 4 larvae for the 3rd instar, 3 for the 4th instar, and 2 for the 5th instar. Pooled tissue was rinsed and homogenized in 0.3 mL of ice-cold buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) using beads and a homogenizer (Fisherbrand Bead Mill 24, Waltham, MA, USA). The homogenized tissue was then centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were collected for enzymic assays. Protein concentration of each enzyme extract was measured using a Bradford protein assay kit with a bovine serum albumin standard [28] (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Prior to enzymatic testing, samples were diluted 10-fold and assayed for protease, APN, and ALP activity. Three replicates (distinct pools) were performed per strain and instar, and all enzyme and protein assays were conducted in triplicate using a microplate reader (Agilent BioTek Synergy H1 Multimode Microplate Reader, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.4. Midgut Protease Activity

Trypsin and chymotrypsin activities were determined using BApNA and SAAPFpNA as the respective substrates, following slightly modified protocols from Zhu et al. (2007) [29]. Substrate working solutions were prepared by diluting 0.1 mL of BApNA (50 mg/mL in DMSO) or SAAPFpNA (50 mg/mL in Universal buffer) into 4.9 mL of Universal buffer (Britton–Robinson Buffer: Phosphoric acid, Acetic acid, Boric acid, and adjusted to pH 8.5 with sodium hydroxide). For each assay, 50 μL of diluted midgut extract was mixed with 50 μL of substrate solution (final concentration: 0.5 mM) in a 96-well microplate. After 30 s of incubation, the absorbance at 405 nm was recorded every 15 s for 15 min using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader.

2.5. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Aminopeptidase (APN) Activity Assays

Specific activities of APN and ALP were assessed using LpNA and pNPP as substrates, respectively [29]. Working substrate solutions were prepared by diluting LpNA (80 mM in DMSO) or pNPP (51.25 mM in 100% Ethanol) with Tris-HCl (pH 8.5). For each assay, 45 μL of the appropriate working stock LpNA (final concentration: 0.8 mM in Tris-HCl) or pNPP (final concentration: 1.025 mM in Tris-HCl) and 5 μL of midgut extract were added into each well. Absorbance at 405 nm was recorded every 15 s for 15 min using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader.

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Midgut samples from 3rd instar larvae were dissected and preserved in RNAlater, then stored at −80 °C until RNA was extracted. Total RNA was isolated using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), with a minimum of three replicates prepared per colony (each replicate consisting of three pooled midguts). First-strand of cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the SuperScriptTM IV Reverse Transcriptase System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1) were designed using Beacon Designer™ to amplify 100–400 bp fragments of 10 serine protease genes (four trypsin and six chymotrypsin genes), 7 candidate Cry receptor genes (cadherin, ABCC2, ALP, and four APN genes), and 4 detoxification genes (esterase, GST, CYP6B8, and CYP6B28). Elongation factor 1 alpha (EF-1α) and actin were used as internal reference transcript genes for normalizing, EF-1α for serine protease and Cry receptor genes, and actin for detoxification enzyme gene expression. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) reaction was performed in 10 µL volumes containing 1 µL of 1:10 diluted cDNA, 2 µL of 10 µM gene-specific primer, and 5 µL Fast SYBRTM Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplification was carried out on a Bio-Rad CFX Connect real-time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) using the following protocol: 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s followed by 60 °C for 60 s. Gene expression of each gene was measured in at least three replicates (distinct pools) per colony, with each measured in triplicate. Gene expression was analyzed using the ΔCT method, and relative expression levels were estimated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [30].

2.7. Data Analysis

Enzyme activities (trypsin, chymotrypsin, APN, and ALP) and gene expression levels were analyzed using JMP software Version 17.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Differences among treatments were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD test, with significance determined at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Activity of Midgut Trypsin and Chymotrypsin

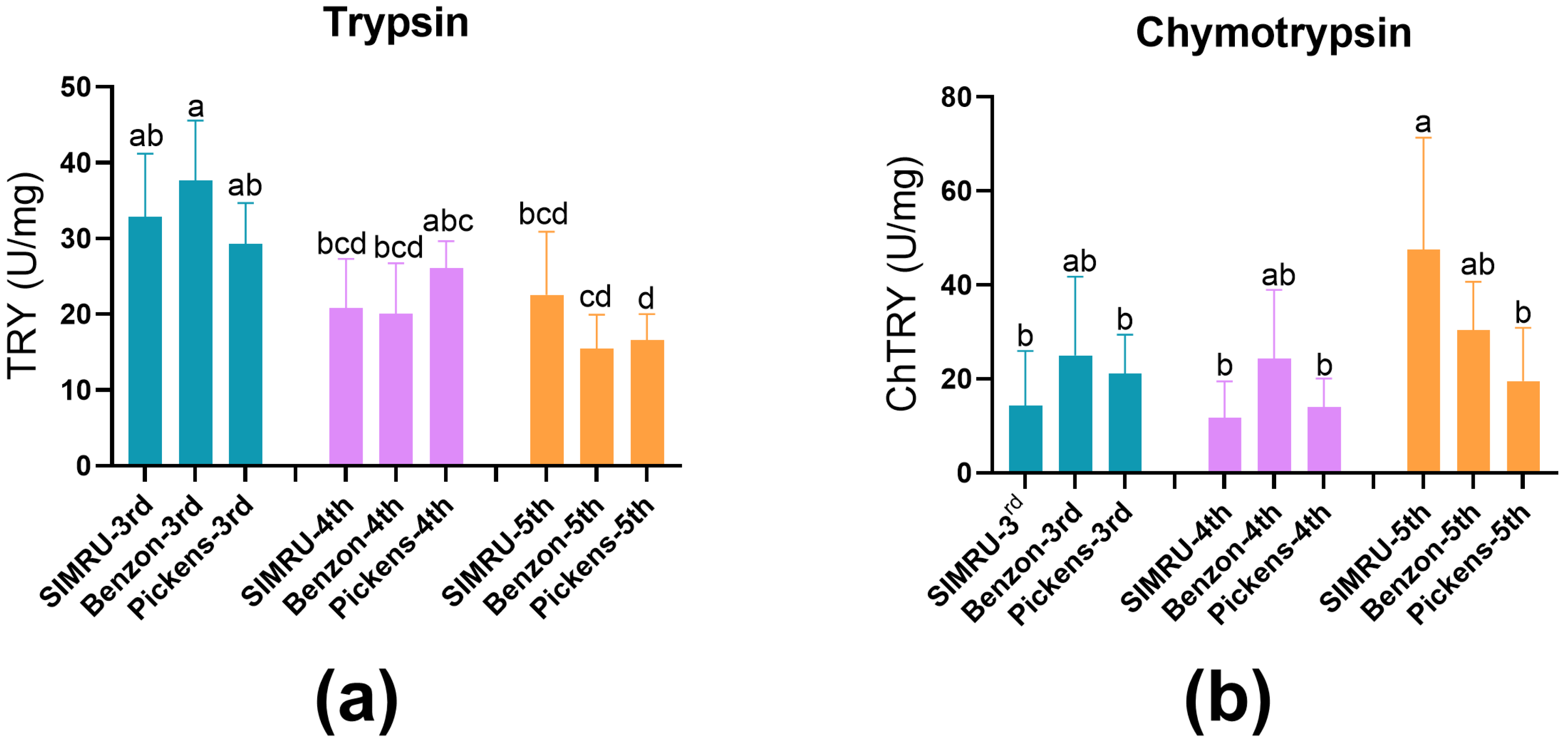

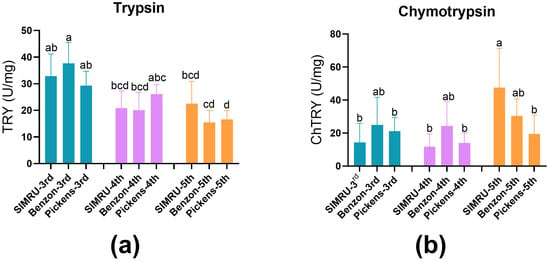

Protease activities (U per mg ± SE) of trypsin and chymotrypsin were examined in midgut extract from 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar H. zea larvae from the SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens colonies. No significant difference in trypsin activity was detected among populations within the same developmental stage (Figure 1a). However, trypsin activity significantly decreased with larval development in both Benzon and Pickens populations (df = 8, 100, F = 12.18, p < 0.001) (Figure 1a). Chymotrypsin activity showed no significant variation among colonies in the 3rd and 4th instar. In contrast, 5th instar larvae from the Pickens colony exhibited significantly reduced chymotrypsin activity compared to the SIMRU colony (df = 8, 93, F = 5.29, p < 0.001), with no significant differences between the Benzon and Pickens populations (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Trypsin (a) and chymotrypsin (b) activity in midgut extracts from three H. zea populations. SIMRU: A laboratory colony maintained continuously since 1971. Benzon: a susceptible colony, obtained from Benzon Research (Carlisle, PA, USA). Pickens: A field-derived Cry-tolerant colony, collected in June 2024 from commercial corn near Pickens, AR. Enzyme activities are expressed as changes in optical absorbance per minute per mg of midgut protein ± SE. Data represents at least three replicates (distinct pools) per strain and instar. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences, as determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05), within each colony at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar stage.

3.2. Activity of Midgut Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Aminopeptidase N (APN)

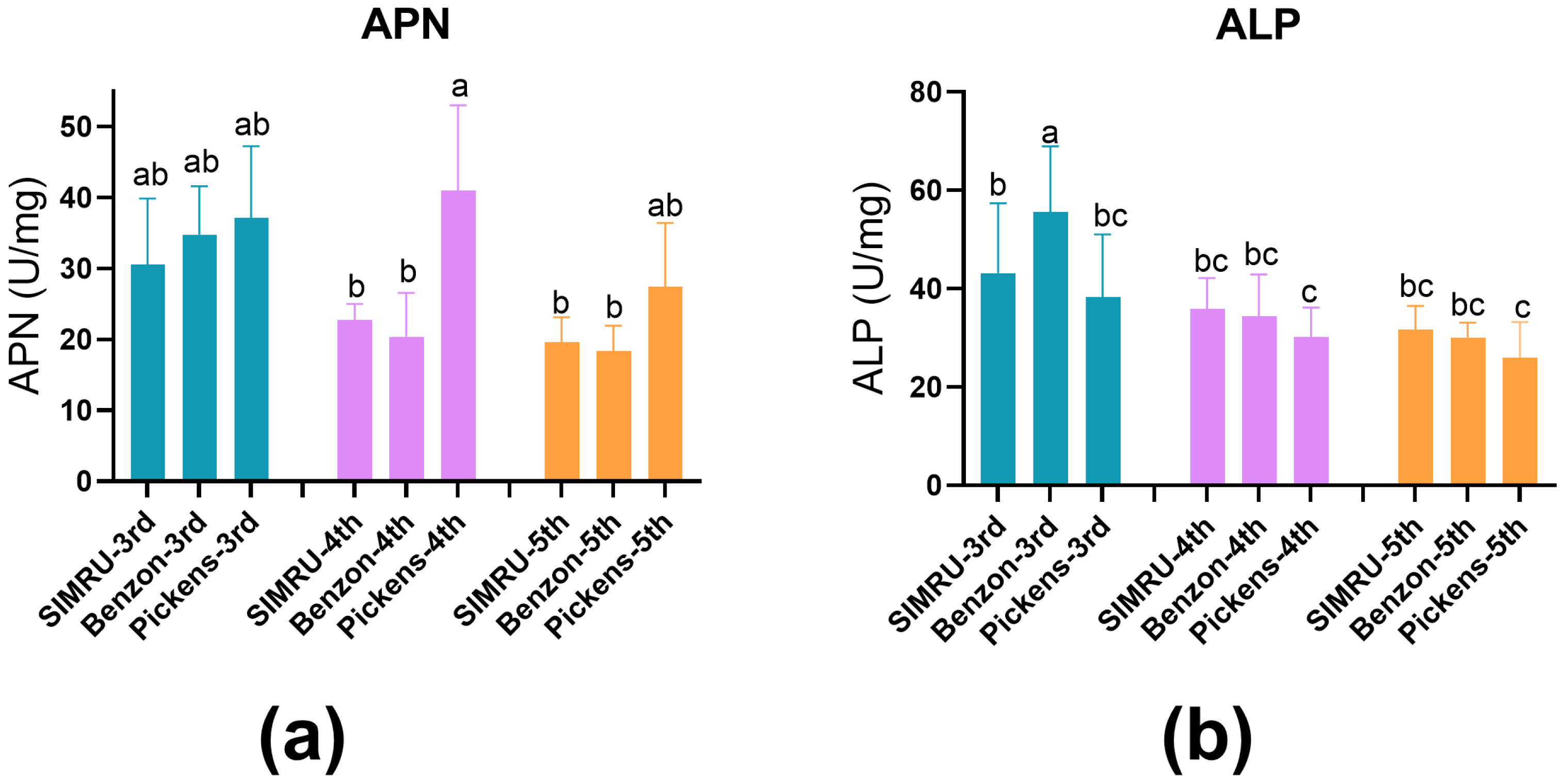

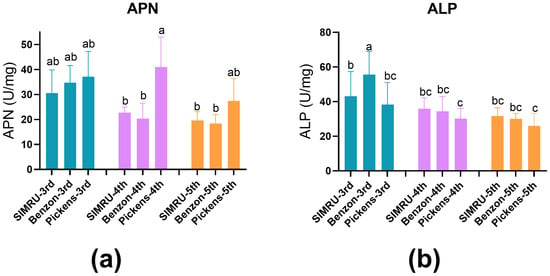

ALP and APN activities (U per mg ± SE) were assessed in midgut extracts from 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar larvae across all three populations. APN activity did not differ significantly among populations in the 3rd and 5th instar. However, 4th instar larvae from Pickens showed significantly elevated APN activity, approximately 1.97- and 2-fold higher than SIMRU and Benzon colonies, respectively (df = 8, 99, F = 10.94, p < 0.001) (Figure 2a). In contrast, no significant differences in ALP activity were detected among SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens in the 4th and 5th instar larvae, but significantly reduced ALP activity in 3rd instar Pickens larvae, compared to Benzon (df = 8, 104, F = 13.83, p < 0.001) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Activities of midgut extracts enzymes: aminopeptidase N proteases (APN) (a) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (b) in three H. zea colonies (SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens). Enzyme activities are expressed as changes in optical absorbance per minute per mg of midgut protein. Data are represented as means ± standard errors from at least three replicates (distinct pools) per strain and instar. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences, as determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05), within each colony at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar stage.

3.3. Expression Levels of Protease, Cry Toxin Receptor, and Detoxification Genes

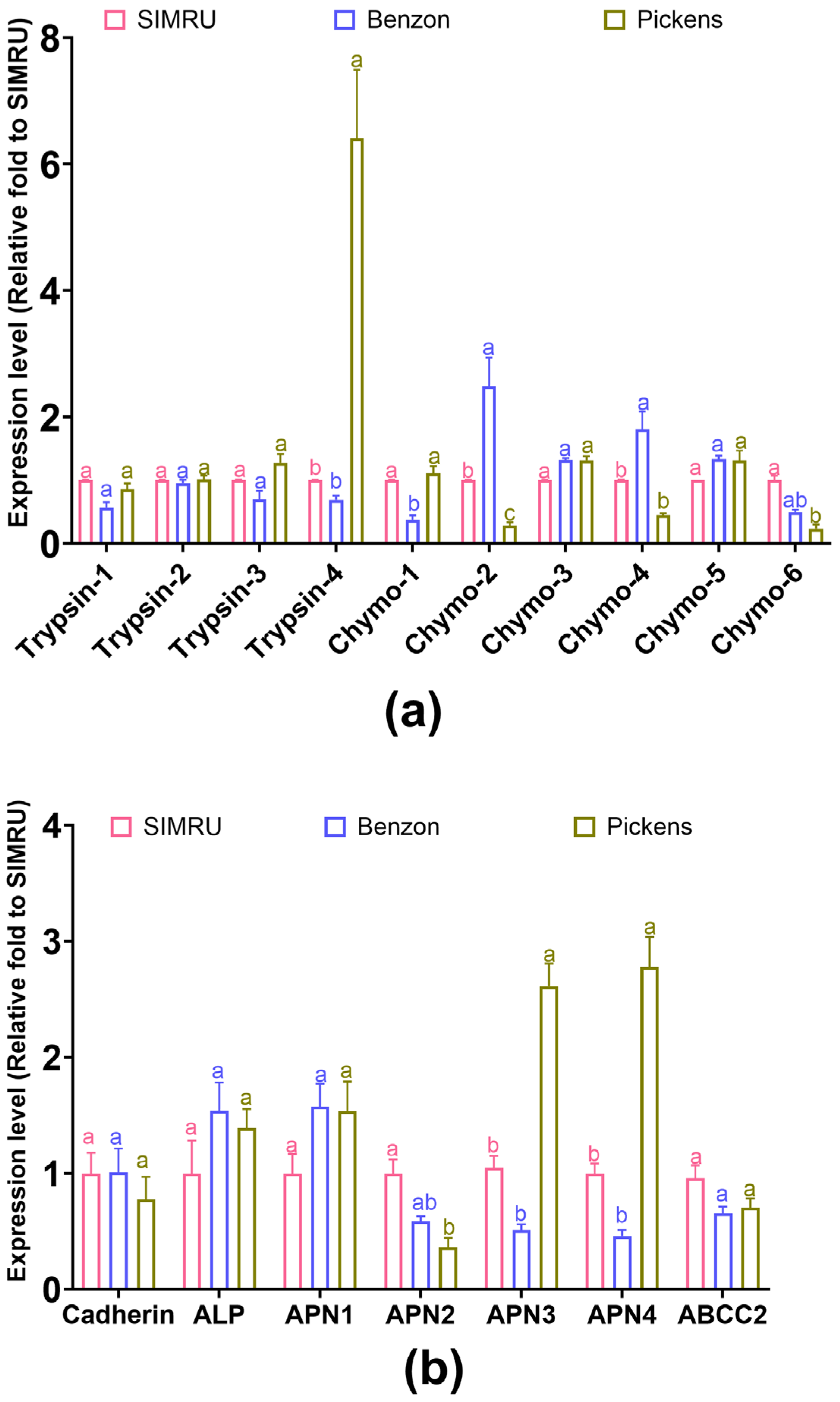

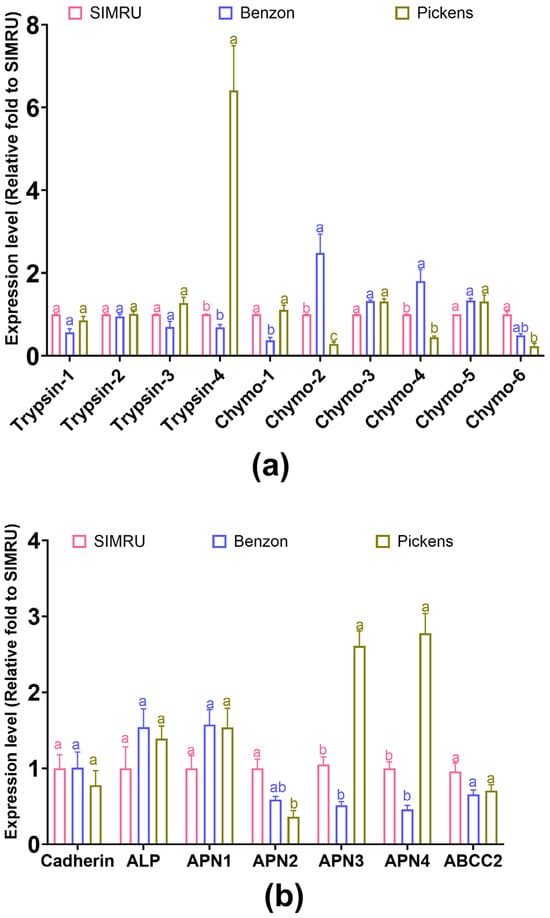

In the Pickens population, the expression of one trypsin gene was significantly increased (Trypsin-4: df = 2, 21, F = 242.22, p < 0.001). In contrast, three of the chymotrypsin genes were significantly downregulated, compared to the SIMRU or Benzon colonies (Chymo-2: df = 2, 21, F = 7.59, p = 0.003; Chymo-4: df = 2, 15, F = 20.28, p < 0.001; Chymo-6: df = 2, 15, F = 6.97, p = 0.007) (Figure 3a). Between the two laboratory colonies, one chymotrypsin gene was significantly downregulated (Chymo-1, df = 2, 18, F = 5.81, p = 0.011), while Chymo-2 was upregulated (Chymo-2: df = 2, 21, F = 7.59, p = 0.003) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Relative expression level of two serine protease gene families (four trypsin and six chymotrypsin genes) (a), and seven receptor binding genes (cadherin, ABCC2, ALP, and four APN genes) (b) in three H. zea colonies (SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens). Gene expression is shown as the fold change relative to the SIMRU colony. Values are means and their standard errors from at least three replicates (distinct pools) per strain. Different lowercase letters on the top of bars indicate significant differences among populations at the 3rd instar stage, as determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

No significant differences in transcript levels were found among the three colonies for cadherin (df = 2, 11, F = 0.41, p = 0.673), ABCC2 (df = 2, 11, F = 3.53, p = 0.065), ALP (df = 2, 11, F = 1.31, p = 0.311), and one APN gene (APN1: df = 2, 11, F = 2.759, p = 0.107) (Figure 3b). Among the remaining three APN genes, one was significantly downregulated, while another two were significantly upregulated in Pickens compared to SIMRU (APN2: df = 2, 11, F = 13.18, p = 0.001; APN3: df = 2, 21, F = 81.93, p < 0.001; APN4: df = 2, 21, F = 81.93, p < 0.001). Between the SIMRU and Benzon colonies, no significant differences in expression were found between the four Cry toxin receptor genes.

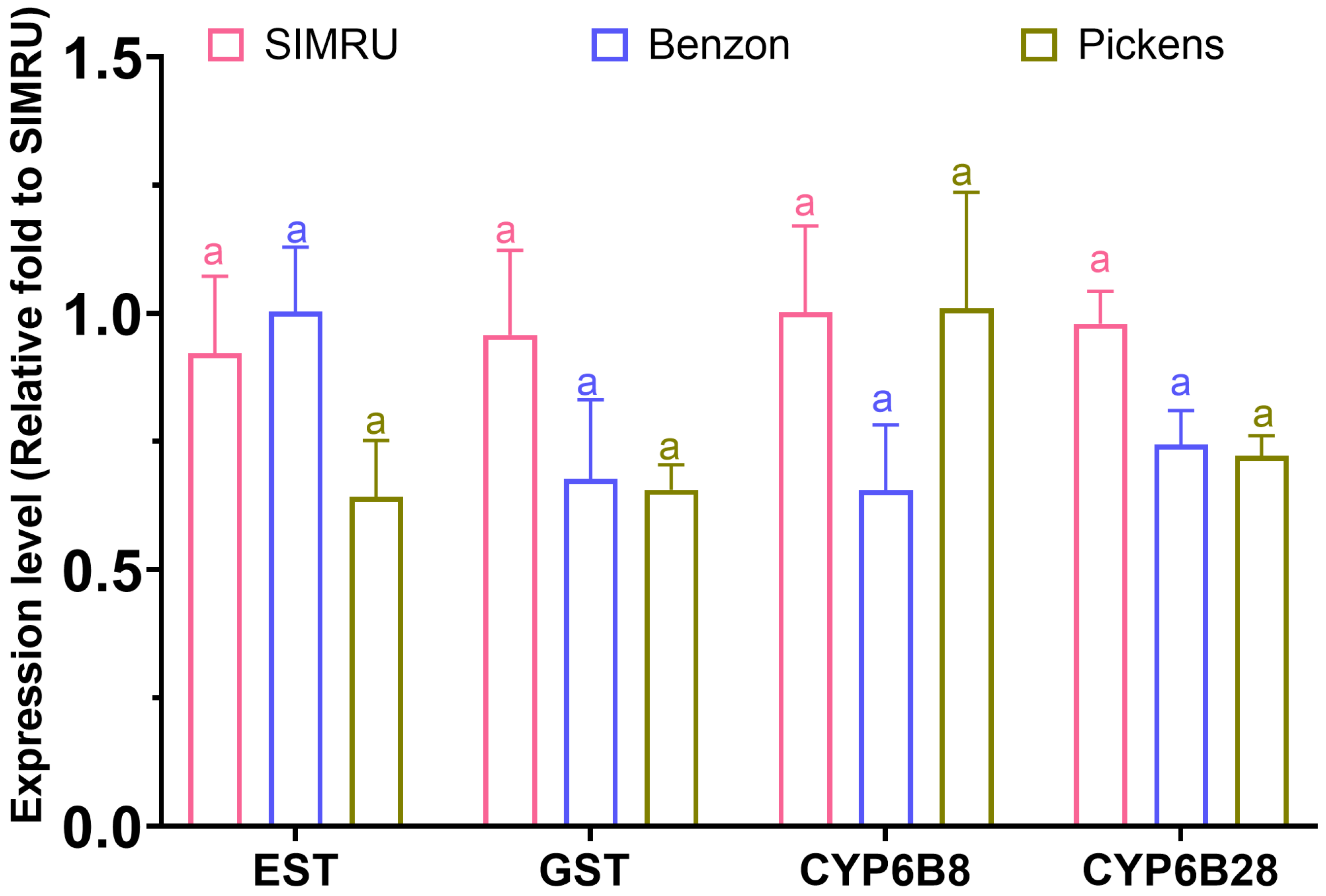

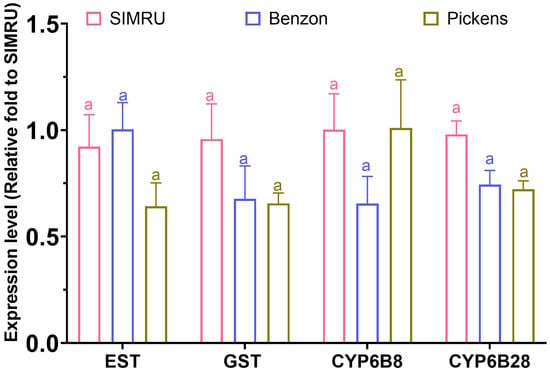

In addition, no significant differences in expression were detected among the three populations for esterase (df = 2, 11, F = 1.75, p = 0.219), GST (df = 2, 11, F = 1.35, p = 0.300), CYP6B8 (df = 2, 11, F = 1.80, p = 0.210), and CYP6B28 (df = 2, 11, F = 3.95, p = 0.052) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relative expression level of four detoxification enzyme genes (esterase, GST, CYP6B8, and CYP6B28) in three H. zea colonies (SIMRU, Benzon, and Pickens). Expression values are shown as the fold change relative to the SIMRU colony. Values are means and their standard errors from at least three replicates (distinct pools) per strain. Different letters on the top of bars indicate significant differences among colonies at the 3rd instar stage, as determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that field-collected H. zea colonies frequently display significant tolerance to Cry toxins [1,2]. For example, Yang et al. (2022) reported that 93 out of 95 colonies collected from non-crop, non-Bt, and Bt crop hosts between 2016 and 2021 exhibited resistance ratios greater than 10 for at least one Cry toxin [2]. In the present study, we examined enzymatic activities and gene expression levels of midgut proteins involved in Cry toxin proteolytic processing and receptor binding in midgut extracts from two reference colonies and one field-derived population of H. zea. Enzyme activity assays revealed significant differences in activities of chymotrypsin, ALP, and APN at specific developmental stages in the Pickens field population compared with the SIMRU or Benzon laboratory colonies. In contrast, trypsin activity remained consistent among colonies within the same developmental stage. Transcriptional analyses of serine protease and Cry toxin receptor genes revealed significant alterations in the expression of several chymotrypsin and APN genes in the Pickens population. No significant differences were detected in the transcript levels of other receptors (cadherin, ABCC2, and ALP) or in the detoxification-related genes examined (esterase, GST, CYP6B8, and CYP6B28). These findings suggest that altered protease activity in the Pickens population may influence its susceptibility to Cry toxins compared to the two laboratory colonies.

Altered proteolytic activation by trypsin and chymotrypsin has been widely reported in multiple insect populations exhibiting resistance to Cry toxins. Proper enzymatic processing of Bt Cry protoxins is critical for mediating toxicity, and improper processing can reduce or eliminate toxin activity, resulting in resistance [31]. In some cases, resistant insects may express alternative proteases that degrade Cry toxins rather than activate them, thereby preventing effective binding to midgut receptors [19,20]. Alterations in midgut proteases have been documented in multiple species, including Plodia interpunctella [32,33], Helicoverpa armígera [34,35], Plutella xylostella [36,37], Ostrinia nubilalis [38,39,40], Heliothis virescens [41,42], Mythimna unipuncta [43], Spodoptera frugiperda [44], Spodoptera littoralis [45] and Leptinotarsa decemlineata [46]. In the present study, reduced chymotrypsin activity and downregulation of multiple chymotrypsin genes in the Pickens population may have impaired Cry toxin processing and activation, potentially contributing to reduced susceptibility commonly observed in field populations [1,2]. Notably, we also detected significant upregulation of one trypsin gene in the Pickens population. Similar upregulation of serine proteases (e.g., HzSP3) has been reported in Cry1Ac-resistant H. zea strains [21] and in field-resistant populations [23]. Such proteolytic alterations may confer cross-resistance to multiple Cry toxins that share similar activation pathways [20,47,48].

The Pickens population exhibited reduced ALP activity and elevated APN activity in 3rd and 4th instars, along with significantly up- or downregulation of three APN family genes in the 3rd instar relative to at least one laboratory colony. These enzymatic activities and transcriptional changes may reduce the efficacy of Cry toxins under field conditions. Consistent with these findings, Cry1Ac-selected H. zea larvae have previously shown 2- and 3-fold reduction in APN and ALP activities, respectively [49]. Similarly, decreased ALP activity has been reported in Cry-resistant strains of H. virescens [50], even when APN activity remained unchanged. Cry1Ac-resistant P. xylostella displayed coordinated downregulation of APN and ALP [51,52,53,54]. In Cry1Ac-resistant Trichoplusia ni, altered expression of TnAPN1 and TnAPN6 was reported, with only APN1 downregulation genetically linked to resistance [55]. Downregulation of APN and ALP has also been documented in other Bt-resistant insect species, including S. exigua [56], Diatrea saccharalis [57] and Ostrinia nubilalis [58]. Collectively, these studies underscore alterations in ALP and APN expression and activity in mediating Cry toxin resistance. While transcriptional variations in the expression of ABCC2 and cadherin have been reported in some Cry toxin-resistant lepidopteran species [19,20], no significant differences in transcript levels of these genes were detected between lab and field-derived H. zea in this study. This is consistent with previous evidence indicating that ABCC2 is not a major functional receptor for Cry1Ac in H. zea [59].

Transcript levels of four midgut detoxification enzyme genes (esterase, GST, CYP6B8, and CYP6B28) did not differ significantly among the three H. zea colonies examined in this study. Likewise, whole-body enzyme assays showed no significant differences in esterases, GST, and P450 activities among colonies, even though the Pickens population has also exhibited reduced susceptibility to λ-cyhalothrin [60]. Although differential expressions of CYP genes have been reported in Cry1Ac-resistant H. zea [61], the absence of variation in the selected detoxification genes in the present study suggests that these enzymes are unlikely to be a major contributor to the reduced Bt susceptibility in the Pickens population.

No significant differences in trypsin and chymotrypsin activity or APN activity were detected between the two laboratory-susceptible colonies within the same larval instar. Similarly, transcript levels of four Cry receptor genes and trypsin did not differ significantly between the Benzon and SIMRU colonies. However, expression of three chymotrypsin genes was significantly altered in Benzon compared to SIMRU, with one gene upregulated and two genes downregulated. We assessed the activities of trypsin and chymotrypsin proteases, APN, and ALP in midgut extracts from 3rd, 4th, and 5th instar larvae across all three populations. In the Pickens population, a significant reduction in chymotrypsin activity was detected in 5th instar larvae, whereas APN activity was elevated in 4th instar larvae. Despite these instar-specific differences, no consistent differences in overall APN and ALP activity were detected across larval stages. Transcript levels of seven known Cry toxin receptor genes (cadherin, ABCC2, ALP, and four APN genes) were evaluated in the Pickens field population, and future work will involve cloning these genes for sequence and protein analysis. Functional characterization using Xenopus laevis oocytes is also planned to evaluate pore formation and morphological changes in response to Cry toxin exposure.

Overall, our findings underscore the need for comprehensive biochemical and molecular investigations to better understand the reduced Bt susceptibility in the field population. Ongoing monitoring of Bt susceptibility in the field population is essential for sustaining the effectiveness of Bt crops and ensuring long-term pest management. Expanding surveillance to include multiple geographically diverse populations and integrating biochemical data with phenotypic resistance assessments will be critical for advancing and optimizing future insect resistance management (IRM) strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agrochemicals5010009/s1, Table S1: Primer sequences used for real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (RTqPCR).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D., N.S.L., and Y.-C.Z.; methodology, S.S.; validation, Y.D., S.S., and B.H.E.; formal analysis, Y.D. and S.S.; investigation, Y.D., S.S., and B.H.E.; resources, B.H.E.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.D., S.S., N.S.L., B.H.E., and Y.-C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the USDA-ARS Research Project 6066-22000-091-00D “Ecologically sustainable approaches to insect resistance management in Bt cotton”. Mention of any trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are reported in the manuscript. Additional details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank R. Michelle Mullen (USDA-ARS, Southern Insect Management Research Unit) for her technical assistance in the lab experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Bt | Bacillus thuringiensis |

| APN | Aminopeptidase N |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| BCC2 | ATP-binding cassette family C2 |

| Cry | Crystalline |

| GSTs | Glutathione S-transferases |

References

- Bryant, T.B.; Greene, J.K.; Reisig, D.; Reay-Jones, F.P. Continued decline in sublethal effects of Bt toxins on Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in field corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Kerns, D.L.; Little, N.; Brown, S.A.; Stewart, S.D.; Catchot, A.L.; Cook, D.R.; Gore, J.; Crow, W.D.; Lorenz, G.M. Practical resistance to Cry toxins and efficacy of Vip3Aa in Bt cotton against Helicoverpa zea. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 5234–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, D.; Musser, F.; Reisig, D.; Greene, J.; Taylor, S.; Parajulee, M.; Lorenz, G.; Catchot, A.; Gore, J.; Kerns, D.; et al. Effects of transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis cotton on insecticide use, heliothine counts, plant damage, and cotton yield: A meta-analysis, 1996–2015. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luttrell, R.G.; Jackson, R.E. Helicoverpa zea and Bt cotton in the United States. GM Crops Food 2012, 3, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dively, G.P.; Venugopal, P.D.; Bean, D.; Whalen, J.; Holmstrom, K.; Kuhar, T.P.; Doughty, H.B.; Patton, T.; Cissel, W.; Hutchison, W.D. Regional pest suppression associated with widespread Bt maize adoption benefits vegetable growers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3320–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, W.D.; Burkness, E.; Mitchell, P.; Moon, R.; Leslie, T.; Fleischer, S.J.; Abrahamson, M.; Hamilton, K.; Steffey, K.; Gray, M. Areawide suppression of European corn borer with Bt maize reaps savings to non-Bt maize growers. Science 2010, 330, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeis, J.; Naranjo, S.E.; Meissle, M.; Shelton, A.M. Genetically engineered crops help support conservation biological control. Biol. Control. 2019, 130, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-M.; Lu, Y.-H.; Feng, H.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Zhao, J.-Z. Suppression of cotton bollworm in multiple crops in China in areas with Bt toxin–containing cotton. Science 2008, 321, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabashnik, B.E.; Sisterson, M.S.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Dennehy, T.J.; Antilla, L.; Liesner, L.; Whitlow, M.; Staten, R.T.; Fabrick, J.A.; Unnithan, G.C. Suppressing resistance to Bt cotton with sterile insect releases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 1304–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISAAA. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops in 2019: Biotech Crops Drive Socio-Economic Development and Sustainable Environment in the New Frontier; ISAAA Brief No. 55; ISAAA: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tabashnik, B.E.; Carrière, Y. Surge in insect resistance to transgenic crops and prospects for sustainability. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabashnik, B.E.; Carrière, Y. Global patterns of resistance to Bt crops highlighting pink bollworm in the United States, China, and India. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 2513–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabashnik, B.E.; Carrière, Y.; Wu, Y.; Fabrick, J.A. Global perspectives on field-evolved resistance to transgenic Bt crops: A special collection. J. Econ. Entomol. 2023, 116, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.I.; Luttrell, R.G.; Young, S.Y., III. Susceptibilities of Helicoverpa zea and Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) populations to Cry1Ac insecticidal protein. J. Econ. Entomol. 2006, 99, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dively, G.P.; Venugopal, P.D.; Finkenbinder, C. Field-evolved resistance in corn earworm to Cry proteins expressed by transgenic sweet corn. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0169115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, J.; Bel, Y.; Lázaro-Berenguer, M.; Hernández-Martínez, P. Vip3 insecticidal proteins: Structure and mode of action. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 65, pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, A.; Pacheco, S.; Gómez, I.; Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry pesticidal proteins. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 65, pp. 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, B.; Johnston, P.R.; Nielsen-LeRoux, C.; Lereclus, D.; Crickmore, N. Bacillus thuringiensis: An impotent pathogen? Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrick, J.A.; Wu, Y. Mechanisms and molecular genetics of insect resistance to insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 65, pp. 123–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Detection and mechanisms of resistance evolved in insects to Cry toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 47, pp. 297–342. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wei, J.; Ni, X.; Zhang, J.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Fabrick, J.A.; Carrière, Y.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Li, X. Decreased Cry1Ac activation by midgut proteases associated with Cry1Ac resistance in Helicoverpa zea. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.L.; Nunziata, S.O.; Guo, R.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Carrière, Y. Mutations in a novel cadherin gene associated with Bt resistance in Helicoverpa zea. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.L.; Quackenbush, J.; Lamberty, C.; Hamby, K.A.; Fritz, M.L. Polygenic response to selection by transgenic Bt-expressing crops in wild Helicoverpa zea and characterization of a major effect locus. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R.V.; Dang, H.T.; Kemp, F.C.; Nicholson, I.C.; Moores, G.D. New resistance mechanism in Helicoverpa armigera threatens transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2558–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, N.S.; Elkins, B.H.; Mullen, R.M.; Perera, O.P.; Parys, K.A.; Allen, K.C.; Boykin, D.L. Differences between two populations of bollworm, Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), with variable measurements of laboratory susceptibilities to Bt toxins exposed to non-Bt and Bt cottons in large field cages. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, T.; Raulston, J. A soybean-wheat germ diet for rearing the tobacco budworm. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1971, 64, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.; Adamczyk, J.J., Jr.; Blanco, C.A. Selective feeding of tobacco budworm and bollworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on meridic diet with different concentrations of Bacillus thuringiensis proteins. J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Abel, C.; Chen, M. Interaction of Cry1Ac toxin (Bacillus thuringiensis) and proteinase inhibitors on the growth, development, and midgut proteinase activities of the bollworm, Helicoverpa zea. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2007, 87, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppert, B. Protease interactions with Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxins. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1999, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, S.; Oppert, B.; Ferré, J. Different mechanisms of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in the Indianmeal moth. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2001, 67, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppert, B.; Kramer, K.J.; Beeman, R.W.; Johnson, D.; McGaughey, W.H. Proteinase-mediated insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23473–23476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Arora, N.; Sivakumar, S.; Rao, N.G.; Nimbalkar, S.A.; Bhatnagar, R.K. Resistance of Helicoverpa armigera to Cry1Ac toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis is due to improper processing of the protoxin. Biochem. J. 2009, 419, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Oppert, B.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Wu, K. Cis-mediated down-regulation of a trypsin gene associated with Bt resistance in cotton bollworm. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, A.H.; Gatsi, R.; Kouskoura, T.; Wright, D.J.; Crickmore, N. Susceptibility of a field-derived, Bacillus thuringiensis-resistant strain of diamondback moth to in vitro-activated Cry1Ac toxin. Appl. Environl Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4372–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Kang, S.; Zhou, J.; Sun, D.; Guo, L.; Qin, J.; Zhu, L.; Bai, Y.; Ye, F.; Akami, M. Reduced expression of a novel midgut trypsin gene involved in protoxin activation correlates with Cry1Ac resistance in a laboratory-selected strain of Plutella xylostella (L.). Toxins 2020, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zhu, K.Y.; Buschman, L.L.; Higgins, R.A.; Oppert, B. Comparison of midgut proteinases in Bacillus thuringiensis-susceptible and-resistant European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera; Pyralidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1999, 65, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Oppert, B.; Higgins, R.A.; Huang, F.; Buschman, L.L.; Gao, J.-R.; Zhu, K.Y. Characterization of cDNAs encoding three trypsin-like proteinases and mRNA quantitative analysis in Bt-resistant and-susceptible strains of Ostrinia nubilalis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 35, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Oppert, B.; Higgins, R.A.; Huang, F.; Zhu, K.Y.; Buschman, L.L. Comparative analysis of proteinase activities of Bacillus thuringiensis-resistant and-susceptible Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcada, C.; Alcácer, E.; Garcerá, M.D.; Martínez, R. Differences in the midgut proteolytic activity of two Heliothis virescens strains, one susceptible and one resistant to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1996, 31, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumbaiah, L.; Oppert, B.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Adang, M.J. Analysis of midgut proteinases from Bacillus thuringiensis-susceptible and-resistant Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 2007, 146, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, J.; García, M.; Hernández-Crespo, P.; Farinós, G.P.; Ortego, F.; Castañera, P. Resistance to Bt maize in Mythimna unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is mediated by alteration in Cry1Ab protein activation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 43, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez–Cabrera, L.; Trujillo–Bacallao, D.; Borrás–Hidalgo, O.; Wright, D.J.; Ayra–Pardo, C. RNAi-mediated knockdown of a Spodoptera frugiperda trypsin-like serine-protease gene reduces susceptibility to a Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ca1 protoxin. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 2894–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Sneh, B.; Strizhov, N.; Prudovsky, E.; Regev, A.; Koncz, C.; Schell, J.; Zilberstein, A. Digestion of δ-endotoxin by gut proteases may explain reduced sensitivity of advanced instar larvae of Spodoptera littoralis to CryIC. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996, 26, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loseva, O.; Ibrahim, M.; Candas, M.; Koller, C.N.; Bauer, L.S.; Bulla, L.A., Jr. Changes in protease activity and Cry3Aa toxin binding in the Colorado potato beetle: Implications for insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 32, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, J.; Van Rie, J. Biochemistry and genetics of insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 501–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, B.; Bezuidenhout, C.; Van den Berg, J. An overview of mechanisms of Cry toxin resistance in lepidopteran insects. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccia, S.; Moar, W.J.; Chandrashekhar, J.; Oppert, C.; Anilkumar, K.J.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Ferré, J. Association of Cry1Ac toxin resistance in Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) with increased alkaline phosphatase levels in the midgut lumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5690–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Adang, M.J. Characterization of a Cry1Ac-receptor alkaline phosphatase in susceptible and resistant Heliothis virescens larvae. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 3127–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Cheng, Z.; Qin, J.; Sun, D.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Crickmore, N.; Zhou, X.; Bravo, A.; Soberón, M.; et al. MAPK-mediated transcription factor GATAd contributes to Cry1Ac resistance in diamondback moth by reducing PxmALP expression. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Gong, L.; Kang, S.; Zhou, J.; Sun, D.; Qin, J.; Guo, L.; Zhu, L.; Bai, Y.; Bravo, A. Comprehensive analysis of Cry1Ac protoxin activation mediated by midgut proteases in susceptible and resistant Plutella xylostella (L.). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 163, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Guo, L.; Bai, Y.; Kang, S.; Sun, D.; Qin, J.; Ye, F.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Xie, W. Retrotransposon-mediated evolutionary rewiring of a pathogen response orchestrates a resistance phenotype in an insect host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300439120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Kang, S.; Chen, D.; Wu, Q.; Wang, S.; Xie, W.; Zhu, X.; Baxter, S.W.; Zhou, X.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; et al. MAPK signaling pathway alters expression of midgut ALP and ABCC genes and causes resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin in diamondback moth. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiewsiri, K.; Wang, P. Differential alteration of two aminopeptidases N associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in cabbage looper. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14037–14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, S.; Gechev, T.; Bakker, P.L.; Moar, W.J.; de Maagd, R.A. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ca-resistant Spodoptera exigua lacks expression of one of four Aminopeptidase N genes. BMC Genom. 2005, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.C.; Ottea, J.; Husseneder, C.; Leonard, B.R.; Abel, C.; Huang, F. Molecular characterization and RNA interference of three midgut aminopeptidase N isozymes from Bacillus thuringiensis-susceptible and-resistant strains of sugarcane borer, Diatraea saccharalis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, B.S.; Johnson, H.; Kim, K.S.; Hellmich, R.L.; Abel, C.A.; Mason, C.; Sappington, T.W. Frequency of hybridization between Ostrinia nubilalis E-and Z-pheromone races in regions of sympatry within the United States. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 2459–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, O.P.; Little, N.S.; Abdelgaffar, H.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Reddy, G.V. Genetic knockouts indicate that the ABCC2 protein in the bollworm Helicoverpa zea is not a major receptor for the Cry1Ac insecticidal protein. Genes 2021, 12, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, H.; Elkins, R.; Mullen, M.; Nathan, S.; Little, K.; Allen, C.; Dixon, K.; Scheibener, S.; Du, Y. The sublethal effects of pyrethroid exposure on the corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea (Boddie)) with impacts to mortality from a diamide insecticide. Crop Prot. 2025, 198, 107370. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie, R.D.; Mitchell, R.D., III; Deguenon, J.M.; Ponnusamy, L.; Reisig, D.; Pozo-Valdivia, A.D.; Kurtz, R.W.; Roe, R.M. Characterization of long non-coding RNAs in the bollworm, Helicoverpa zea, and their possible role in Cry1Ac-resistance. Insects 2021, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.