Abstract

The foliar pathogens of wheat, particularly Zymoseptoria tritici and Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, represent a significant threat to yield. We used a SEIR (Susceptible–Exposed–Infected–Removed) model to quantify epidemic dynamics based on different fungicide application strategies, focusing on the daily dynamic growth rate r(t) (net infection increase) and the removal rate γ(t) (loss infectious tissue) after BBCH 37. In Scenario A (treatment of seed with Systiva®), the r(t) of Z. tritici was positive only during the early phase of the epidemic, followed by progressive suppression over time, while the r(t) for P. tritici-repentis remained negative throughout. Scenario B (seed treatment combined with foliar propiconazole) resulted in uniformly negative r(t) values for both pathogens, indicating stronger and sustained suppression. These findings highlight the practical utility of epidemic growth rate modeling for evaluating fungicide strategies and support integrated seed + foliar applications as a robust approach to disease management in wheat.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is a staple crop that provides important economic and food security crop throughout Mediterranean agriculture, but the production of wheat can often be limited by leaf disease caused by fungi. Tan spot and Septoria leaf blotch are two of the most prevalent and economically important foliar diseases of wheat, both of which are associated with foliar fungal species. There are considerable differences in the biology of infection between the two organisms; P. tritici-repentis is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen that produces necrotrophic toxins that cause tissue death, and Z. tritici is a hemibiotrophic pathogen that has a longer latent period than P. tritici-repentis [1,2].

The high humidity and moderate temperature provide an ideal environment for the growth of P. tritici-repentis, with optimal growth occurring at 25 °C and a water activity value of 0.99. The growth of P. tritici-repentis, as well as its virulence, is strongly correlated with increased rainfall, and therefore with higher levels of humidity; this has been documented in a number of studies [3]. In contrast, lower temperatures (and thus lower humidity) reduce pathogen growth. Similarly, Z. tritici incidence and severity are significantly impacted by temperature and moisture levels. Higher temperatures have been shown to decrease disease incidence (by reducing virulence during host penetration and pycnidia formation) [4]. Both pathogens are dependent upon rainfall to propagate, and both have shown a strong correlation between precipitation and increased prevalence and severity of tan spot; additionally, Z. tritici severity increases with increasing moisture levels [5,6]. In addition, P. tritici-repentis is more commonly seen in sub-humid regions than in semi-arid regions, indicating that Mediterranean climates with sub-humid conditions tend to favor co-occurrence of these pathogens. It is important to note that climate change may have a significant impact on pathogen dynamics, with increased temperature and CO2 levels influencing the virulence and spread of Z. tritici [4,7,8,9].

Various fungicides, including pyraclostrobin, propiconazole, tebuconazole, and azoxystrobin, can help to mitigate the incidence of tan spots [10]. To control Z. tritici, however, demethylation inhibitors (DMIs), succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs), and quinone outside inhibitors (QoIs) would typically be deployed [11]. Fungicides should be applied at flag leaf emergence to limit yield loss, which can be as high as 59% in untreated plots [10]. Multiple treatments are frequently required under situations of high disease pressure, according to field trials [12,13]. In light of the increasing incidence of P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici infection and the emergence of fungicide-resistant strains, an integrated disease management approach (e.g., through the use of biocontrol agents, resistant varieties, and optimized fungicide use) represents the most sustainable, effective response [14,15].

The co-occurrence of P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici is also a typical phenomenon in the Mediterranean environment of Greece, specifically during the stem elongation and flag leaf stages (BBCH 37–39); at this stage in the crop’s life cycle, the structure of the crop canopy together with the microclimate of the area promote the spread of these two diseases [16]. The two main components of an Integrated Disease Management (IDM) strategy for the management of the pathogens include the use of pre-planting seed treatments and the use of systemic fungicide treatments applied on a phenologically-timed basis [1,2,16,17]. However, there is very little published data regarding the interplay between pathogen biology, environmental variables and management timing. The objective of this study was to develop an SEIR-based modeling framework capable of quantifying early epidemic dynamics of Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis under different fungicide management scenarios. In this study, the epidemic growth rate r(t) refers to the net rate of change in the infectious compartment, while the SEIR structure partitions leaf area into susceptible (S), exposed (E), infectious (I), and removed (R) tissue. These terms are used consistently throughout the manuscript.

We calculated the value of r(t), that is, the rate of epidemic increase at day t, as the metric used to compare the following two IDM management strategies: treatment with just seed treatment versus treatment with both seed treatment and foliar fungicides. Within this context, the SEIR framework serves as a predictive tool for evaluating the impact of fungicide strategies on epidemic suppression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Biological Context and Pathogen Traits

The simultaneous interactions of the pathogens Z. tritici (Septoria leaf blotch) and P. tritici-repentis (tan spot) in winter wheat have been simulated in a study. Each has a distinct mode of nutrition, tempo of infection, and reaction to the environment where it occurs. The mode of nutrition for P. tritici-repentis is necrotrophic; this means that it develops a toxin called (ToxA) that produces fast tissue necrosis [18]. The time period from infection to necrosis is approximately 2 days, and under humid conditions the pathogen’s transmission occurs rapidly. Z. tritici is hemibiotrophic meaning it exhibits an asymptomatic colonization phase prior to necrotrophy. It has a longer latent time than P. tritici-repentis, (3–5 days) with transmission occurring more readily with prolonged leaf wetness and moderate temperature [18]. SEIR model parameters directly influence the transmission rate (β), the latent rate (σ), the removal rate (γ), and the dynamic growth rate r(t) in these two diseases.

2.2. SEIR Modeling Framework

The SEIR (Susceptible–Exposed–Infectious–Removed) model is an epidemiological model that allows researchers to study the dynamics of infectious disease over time. In particular, it has been used to explore how different types of human and plant pathogens such P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici develop over time, initial infection to symptom expression and eventual tissue necrosis.

The model partitions the host leaf area into four mutually exclusive compartments:

- S(t): Healthy tissue vulnerable to infection (Susceptible leaf area).

- E(t): Infected tissue in the latent phase, not yet infectious (Exposed).

- I(t): Actively infected tissue capable of transmitting the pathogen (Infectious).

- R(t): Necrotic or non-infectious no longer participating in transmission (Removed).

The dynamics of these compartments are governed by a system of ordinary differential equations:

where

- β(t): Time-dependent transmission rate (dynamic transmission rate), modulated by temperature, humidity, and fungicide effects.

- σ(t): Latent rate, representing the transition from exposed to infectious tissue.

- γ(t): Removal rate, representing the rate of necrosis or non-infectious tissue.

The SEIR model framework is well-suited to represent foliar diseases that have a well-defined latent period and have a strong dependence on environmental conditions for transmission success [19,20,21]. This framework allows for the consideration of crop phenology (i.e., BBCH), how fungicides can impact disease dynamics, and specific plant pathogen characteristics (i.e., that different P. tritici-repentis isolates produce different necrosis-inducing effectors, and they are also highly host-specific).

The SEIR model has been demonstrated as a viable approach to modeling some wheat pathosystems, such as tan spot and Septoria blotch, where the latency and the influence of environmental factors on disease development are fundamental to understanding disease dynamics [20,21,22]. The SEIR structure also provides for characterizing the occurrence of the inverse gene-for-gene interaction in P. tritici-repentis when necrosis-inducing effectors interact with dominant susceptibility genes in the host [20].

In this context, all parameters used in the SEIR framework are summarized in Supplementary Materials, where they are grouped as empirically measured, literature-derived, or model-calibrated.

2.3. Calibration of Baseline Transmission Rate () for Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis

The baseline transmission rate β0 for Z. tritici was estimated using quantitative early-epidemic data collected from long-term wheat field trials in central Greece. These datasets include (i) sequential disease severity assessments during tillering and stem-elongation stages (GS23–GS31), (ii) measurements of initial infection levels and their rate of increase over 7–14-day intervals in untreated plots, and (iii) documented early-season epidemic build-up associated with stubble-borne inoculum under Mediterranean climatic conditions [1,16,19].

The initial exponential growth rate r was calculated from successive disease assessments in untreated plots using

where

- for Z. tritici, I(t) is the proportion of infected leaf area. In our field datasets, typical early-season increases from 2% to 10% infected leaf area over a 10-day interval yielded r ≈ 0.33 day−1, consistent with previously reported early epidemic growth rates under conducive Mediterranean conditions [23]. The infectious period for Z. tritici was set to D ≈ 4.5 days based on lesion development and pycnidia formation dynamics [24], giving a removal rate γ = 1/D ≈ 0.22 day−1 (Supplementary Materials). Assuming S0 ≈ 1 at epidemic onset and applying the SEIR relation r = β0S0 − γ, the calibrated value was

- For P. tritici repentis, I(t) is the proportion of infected leaf area. In our field datasets, early season increases from approximately 1% to 3% infected leaf area over a 10-day interval yielded r ≈ 0.11 day−1, consistent with reported early epidemic development of tan spot under Mediterranean conditions [25,26]. The infectious period for P. tritici repentis was set to D ≈ 3.85 days based on lesion expansion and necrotic progression dynamics [25,26], giving a removal rate γ = 1/D ≈ 0.26 day−1 (Supplementary Materials). Assuming S0 ≈ 1 at epidemic onset and applying the SEIR relation r = β0S0 − γ, the calibrated value was

These values, 0.55 day−1 and 0.38 day−1 (Supplementary Materials: Calibration of β0 for Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis), align with the observed rapid early-season increase of Z. tritici in Greek wheat systems, where high humidity, dense canopies, and stubble-borne inoculum promote strong primary infection pressure [1,16,19].

2.4. Initial Conditions and Seed Treatment Effects

The simulation started at BBCH stage 37, using actual field data collected during our previous research trials [1,2,16,18,19]. Untreated situations are modeled with a starting point for the Infectious compartment of I0 = 0.05 (latent infections) and E0 = 0.05 (permanent/remaining). If no previous necrosis occurred, the Susceptible compartment is calculated defensively as S0 = 0.90 and R0 = 0. Treatment with Systiva (fluxapyroxad) has been shown to reduce early infection (primary spore germination and colonization) pressure by approximately 80% [27]. The result is that for an infected plant there is an Infectious compartment introducing I0 = 0.01, but the starting point for the ET and later stages remain the same (E0). The results of the Susceptible equations will be revised because of the first two equation’s modifications to calculate the new Susceptible value based on the variable changes introduced in calculations.

These adjusted initial conditions are applied uniformly across both pathogens, with subsequent divergence governed by pathogen-specific parameters and environmental modulation.

2.5. Environmental Modulation of Transmission

The effective transmission rate β(t) is dynamically modulated [28] by temperature T(t), relative humidity RH(t), and fungicide application fF(t):

The transmission rate β(t) is introduced in the Methodology/Model section as the core equation showing that transmission is not constant but depends on environmental factors and fungicide application.

Temperature Function:

This function explains how temperature around the optimum (Topt = 22 °C) influences transmission [29]. It is presented as a Gaussian response, showing that transmission decreases when temperature deviates from the optimum.

Humidity Function:

This function introduces the critical relative humidity threshold (RHcrit = 85%) above which infection is favored. In the text, it is used to demonstrate that humidity is a key driver in the epidemiology of Z. tritici.

Fungicide Effect Function:

This function is incorporated to show how fungicide application reduces transmission after a specific time point (tappt). In the manuscript, it provides the explicit link between the mathematical model and the management scenarios (seed treatment vs. seed + foliar application). The decay parameters (δ = 0.8, λ = 0.2) follow standard exponential decay formulations commonly used in fungicide persistence modeling and fall within the typical persistence ranges reported for SDHI and DMI fungicides under Mediterranean field conditions.

Environmental factors dynamically shape the effective transmission rate β(t): temperature, relative humidity, and fungicide application act as modulators, altering the balance between pathogen spread and suppression. Specifically, β(t) is expressed as , where each function captures the influence of microclimatic conditions and management practices on epidemic development. Daily temperature T(t) and relative humidity RH(t) data were obtained from the Hellenic National Meteorological Service station. These processed environmental inputs were used directly in the β(t) scaling functions.

The dynamic description of transmission rate β(t) is consistent with previous studies, which demonstrated that management practices and microclimatic conditions influence the Z. tritici epidemiology. Such temperature responses, with an optimal temperature around 22 °C, have been observed as Gaussian-like curves, indicating adaptation to temperature [29]. Also, high levels of moisture, such as relative humidity > 85%, have been shown to positively influence the success rate of Z. tritici infection [30]. On the other hand, fungicides have been documented to reduce transmission rates following the application of the fungicide, linking transmission models and practical management strategies [31]. The above-cited references also provide the scientific rationale for modelling fT(T), fRH(RH), and fF(t) into the SEIR framework.

2.6. Estimation of the Epidemic Growth Rate r(t)

The epidemic growth rate r(t) quantifies the net expansion of the infectious compartment and varies daily [32], with environmental conditions and crop phenology:

where

- β(t) is the time-varying infection rate; modulated by weather and the decay of fungicides.

- S(t) is the proportion of susceptible leaf area (in this case, infected) by either the fungus or the virus at time t.

- γ(t) is when infectious tissue becomes necrotic or otherwise non-infective.

Environmental conditions strongly influence both the transmission rate (β) and the removal rate (γ), as temperature and humidity directly affect infection processes and disease progression (e.g., BBCH37 vs. BBCH39). For example, at BBCH37 (cool and dry), r(t) may be negative, but at BBCH39 (warm and humid), r(t) may become positive with only a seed treatment [33,34].

2.7. Numerical Integration: Euler Method

To simulate the temporal evolution of the SEIR compartments, we employed the forward Euler method—a first-order explicit numerical scheme suitable for systems of ordinary differential equations with moderate stiffness and short time horizons [35,36].

The Euler method approximates the solution at discrete time steps tn = n·Δt, where Δt = 1 day, using:

The choice of the Euler method is a result of its simplicity, transparency and equivalence to Daily Agronomic Observations. More sophisticated models (such as Runge–Kutta methods) [37,38]) would yield more precise results, but the Euler method is adequate for simulating short (≤10-day) periods with controlled parameters.

All compartment values were bounded from 0 to 1, and the total leaf area remained constant:

The parameters β(t), σ(t), and γ(t) for rates of transmission, latency, and removal were updated daily with respect to temperature, humidity, and fungicide degradation, in addition to specific BBCH susceptibility profiles.

2.8. Study Sites and Empirical Support

The SEIR model was created using data collected from field trials in Central Greece, which studied the earliest appearances of the tan spot and Septoria leaf blotch on winter wheat. The trials also employed UAVs and remote sensing methods to correlate with NDVI and NDRE data that indicated Systiva® (fluxapyroxad), when applied as a seed treatment, resulted in decreased foliar disease scores and improved plant growth [1,2]. Additional studies found a maximum reduction of 60% leaf blotch severity during the tillering and stem elongation stages [19], and even more trials showed that increased tiller density and lower disease scores resulted from Systiva®’s ability to inhibit P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici [2,19]. Field trials conducted under minimum tillage systems in Larissa, Thessaly demonstrated that model-predicted outcomes were achieved, as evidenced by a decreased beta value (β), an increased gamma value (γ), and an early suppression of the epidemic growth rate (r(t)) under both Systiva® and combined fungicide applications.

3. Results

3.1. This Simulation Overview

SEIR simulations were conducted for a 10-day period following BBCH 37, under representative environmental conditions for Thessaly (April). Daily temperature ranged from 17 °C to 26 °C, and relative humidity fluctuated between 78% and 95%. Two intervention scenarios were compared:

- Scenario A: Seed treatment with Systiva® only;

- Scenario B: Seed treatment with Systiva® plus foliar application of propiconazole at BBCH 37.

Both P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici were modeled independently, using pathogen-specific parameters and dynamic environmental modulation of transmission.

3.2. Epidemic Growth Rate r(t)

To quantify the rate of disease increase under different intervention scenarios, the epidemic growth rate r(t) was computed dynamically at each time step using the following SEIR-based expression:

This formulation reflects the net growth potential of the infectious compartment. Positive values of r(t) indicate disease increase, while negative values reflect suppression.

- In Scenario A (Systiva® only), Z. tritici maintained slightly positive r(t) values during the early phase of the simulation, indicating continued disease increase.

- P. tritici-repentis exhibited near-zero or slightly negative r(t) under Systiva® alone.

- In Scenario B (Systiva® + propiconazole), both pathogens showed consistently negative r(t) values throughout the simulation, with P. tritici-repentis reaching −0.22 and Z. tritici −0.19 by day 6.

The epidemic growth rate r(t) was computed dynamically at each time step using the following expression derived from the SEIR-based expression.

Dynamic output from the SEIR model in Table 1 reveals how the fixed estimate of β(t), S(t), γ(t) and r(t) during the early days of simulation are transformed into time-dependent values. The results indicate that the application of foliar fungicide reduces the transmission rate of disease (β(t)), which limits the ability of the pathogen to infect new leaf tissue, in addition to increasing the rate of removal of infected leaf tissue due to necrosis or pathogen suppression (γ(t)). The dynamic output presented in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials, Calculations for Table 1) indicates the usefulness of the SEIR framework as a way to model time-dependent evolution of epidemic pressure over time, as well as how the efficacy of fungicides and environmental modification may help to suppress or enhance the rate for developing disease. The integrated management strategies that follow are based on this foundation.

Table 1.

Infection dynamics of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis and Zymoseptoria tritici under seed treatment alone (Systiva®) across 10 days post BBCH 37. Theoretical and empirical S(t) values are shown to contrast model-defined susceptibility with field-calibrated canopy conditions.

From Table 1 we concluded that changes in β(t) and S(t) correspond directly to observable disease progression in the canopy. Higher β(t) values indicate increased infection pressure and typically precede visible lesion expansion, whereas reductions in S(t) reflect the gradual replacement of healthy tissue by latent or infectious lesions. For Z. tritici, low positive r(t) values during the early colonization phase are consistent with the slow, hemibiotrophic colonization phase observed in the field, where symptoms remain limited despite active infection. In contrast, P. tritici-repentis shows negative r(t) values earlier, reflecting its rapid necrotrophic transition and the faster appearance of visible tan spot lesions.

Table 2 shows the daily SEIR; updates across 10 days post BBCH 37 were computed using the forward Euler scheme, and epidemic growth rates r(t) were derived to indicate whether transmission exceeded removal or suppression dominated infection dynamics.

Table 2.

Infection dynamics of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis and Zymoseptoria tritici under combined seed plus foliar fungicide (Systiva® + Propiconazole) across 10 days post BBCH 37.

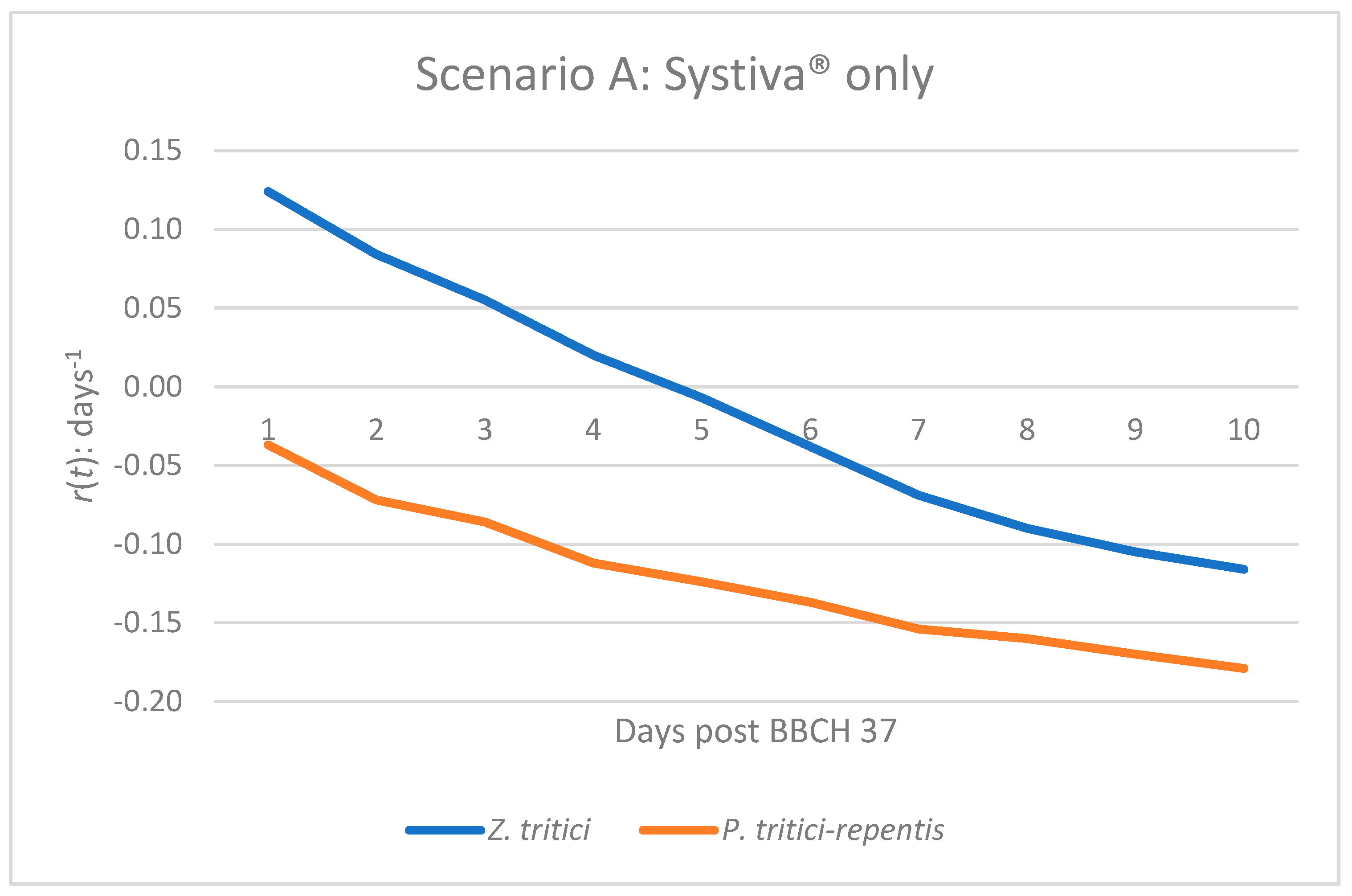

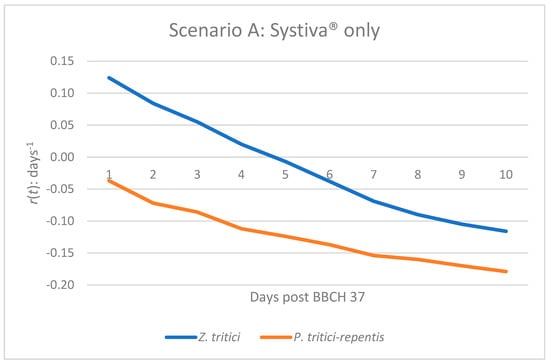

The growth of the epidemic of Z. tritici in scenario A will experience very slight positive growth for a few days after BBCH 37. Following this short period of potential disease increase, r(t) will progressively and continually decline, eventually crossing the zero-growth line around mid-period (Figure 1 and Table 1) and will remain there until day 10. This pattern of disease emergence indicates that while seed treatment can temporarily suppress plant diseases (in this case Z. tritici), this protective effect will diminish over time, ultimately allowing for a small amount of pathogen activity before the greater suppression has a complete effect. For P. tritici-repentis, the negative growth pattern will be apparent on the very first day of tracking r(t), and will progressively get more negative with time (Figure 1 and Table 1), thus demonstrating that this plant disease type will have a greater consistency of suppression when used with any form of seed treatment than the other pathogens discussed in scenario A.

Figure 1.

Infection dynamics based on epidemic growth rate r(t) of Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis under seed treatment alone (Systiva®) at BBCH 37.

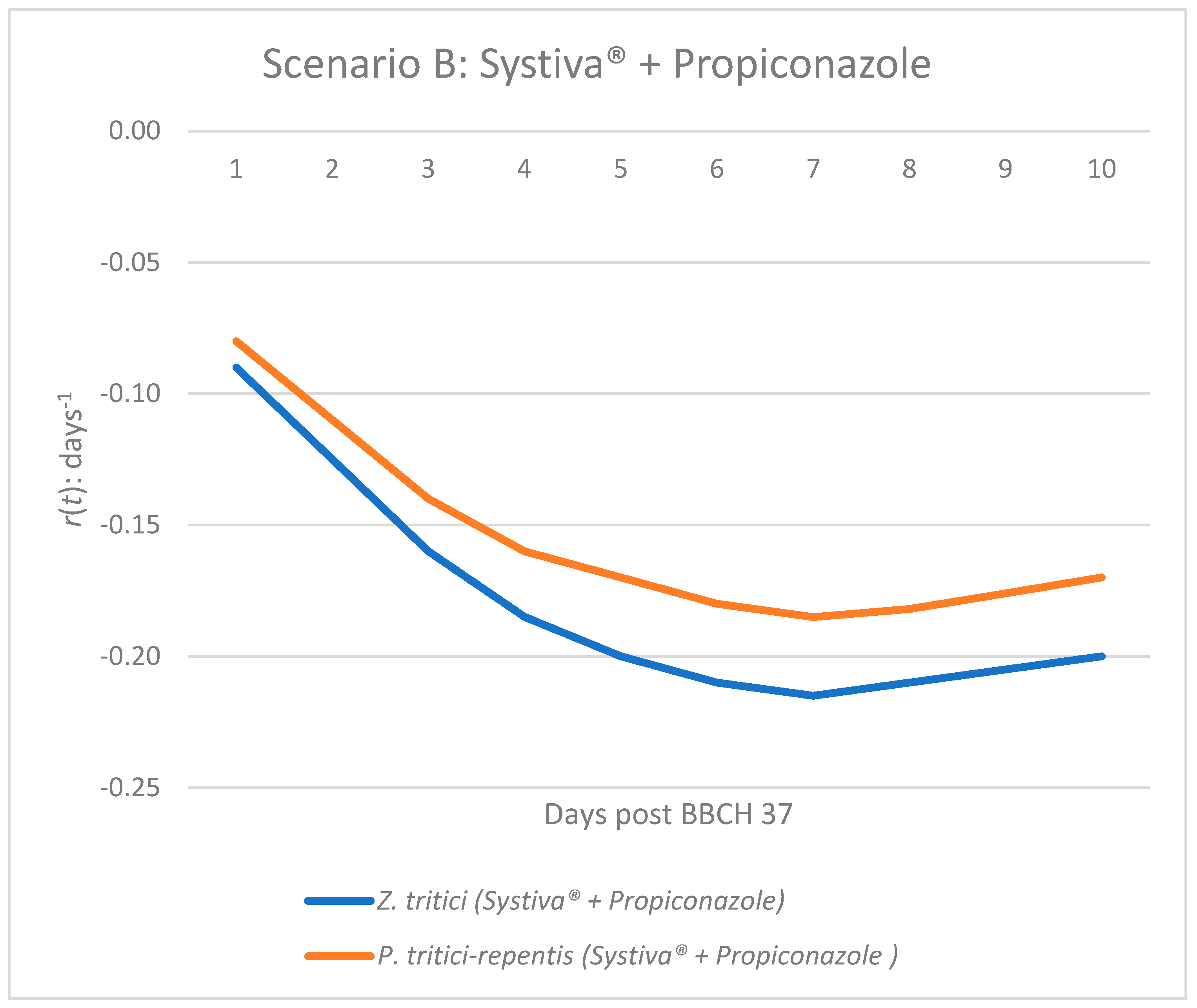

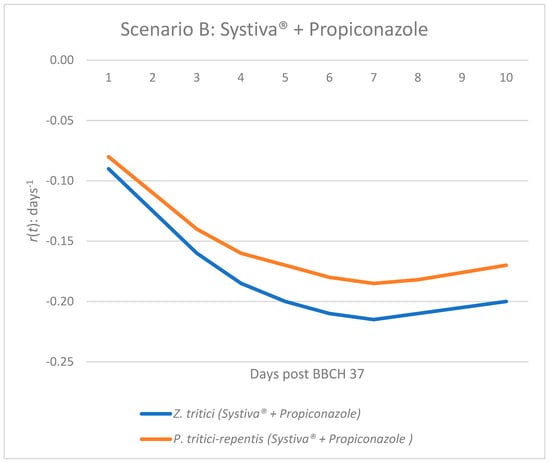

In Scenario B (Systiva® seed treatment combined with propiconazole foliar application), both pathogens exhibit consistently negative values across all days (Figure 2). The magnitude of suppression is greater than in Scenario A, with values dropping as low as −0.20 to −0.215 (Table 2, Figure 2). This indicates that the combined strategy not only prevents any initial disease increase but also maintains a stable and robust suppression throughout the 10-day period. The results highlight the synergistic effect of integrating foliar fungicide with seed treatment, ensuring that both Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis remain under effective control.

Figure 2.

Epidemic growth rate r(t) of Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis under seed treatment (Systiva®) and foliar application of propiconazole at BBCH 37.

- Transmission rate β(t)-Calculations

To estimate the transmission rate β(t) at t = 1 (i.e., Day 1 post-emergence) in the SEIR simulation under Scenario A (Table 1), we apply an exponential decay model to account for the protective effect of the seed-applied fungicide:

where

- k = 0.025 (daily decay constant for fluxapyroxad);

- fenv: environmental scaling factor (humidity, temperature);

- t = 1 (Day 1 post-emergence).

As follows:

- Susceptible Leaf Area S(t) for Day 1

The values are calculated using the exponential decay equation:

or,

- S0 = 1.0 (initial susceptibility);

- d = 0.105 for Z. tritici;

- d = 0.15 for P. tritici-repentis.

The empirical values of S(1) used in the SEIR simulation—0.72 for Z. tritici and 0.70 for P. tritici-repentis—do not arise from the standard exponential decay model with fixed physiological hardening rates. Instead, they reflect a composite reduction in leaf susceptibility due to multiple interacting factors:

- Early fungicide activity (e.g., Systiva® systemic protection);

- Leaf age and cuticle development;

- Canopy microclimate effects (e.g., humidity retention, light interception);

- Pathogen-specific colonization dynamics.

Mathematically, these values correspond to decay coefficients of approximately d = 0.328 for Z. tritici , and d = 0.357 for P. tritici-repentis, which are significantly higher than the theoretical values d = 0.105 and d = 0.15, respectively. This adjustment is consistent with canopy modeling approaches that integrate leaf emergence, expansion, and senescence into disease risk estimation.

According to Milne et al. [39,40], a model of the wheat canopy was developed and integrated into a decision support system to link the stages of leaf development to the spread of pathogens and performance of fungicides. They point out that the timing of the leaf’s susceptibility to disease is only partly influenced by time; the interactions of the leaves’ physiological conditions and environmental conditions have a major influence, and they are different for each cultivar and cropping system.

- Recovery Rate γ(t) Calculation

The recovery rate γ(t) is defined as the inverse of the average infectious period D(t):

Based on Derbyshire et al. [24], for Z. tritici the average infectious period D(1) is approximately 4.5 days; thus, (Table 1).

Based on Cox et al. [41], for P. tritici-repentis the average infectious period D(1) is approximately 3.85 days; thus, (Table 1).

- Epidemic Growth Rate r(t)—Day 1 Calculation

The epidemic growth rate r(t) quantifies the net expansion or contraction of disease within the host canopy at time t. It is defined as

where

- β(t) is the transmission rate at time t;

- S(t) is the proportion of susceptible leaf area;

- γ(t) is the recovery/removal rate.

The positive growth rate of +0.124 indicates active disease increase, consistent with Z. tritici’s latent colonization and immune suppression mechanisms.

The negative growth rate of −0.037 suggests early suppression of epidemic spread, likely due to rapid lesion necrosis and fungicide protection.

- Model Parameterization for Zymoseptoria tritici—baseline transmission rate β0

The baseline transmission rate β0 represents the theoretical maximum rate of pathogen spread under optimal environmental conditions and in the absence of fungicide suppression.

For Z. tritici, we assigned β0 ≈ 0.55, based on converging evidence from microscopy, transcriptomics, effector biology, and field-calibrated SEIR simulations.

Microscopy studies of both Z. tritici and the transcriptome show that Z. tritici has a long asymptomatic (biotrophic) period before exhibiting a very rapid switch to necrotrophy, at which time it produces large amounts of pycnidiospores and invades through stomata [42]. Using confocal microscopy, Aegilops cylindrica infected leaf tissues were shown to be most susceptible and most easily colonized between days 7 and 15 post infection (dpi), which was during the BBCH 31–33 stage of development, a period when high canopy humidity and increased exposed leaf area created conditions favorable for Z. tritici colonization [39]. While Hansen et al. [43] did not include a numerical estimate for the rate of Z. tritici transmission, their use of microscopy and transcriptomic analyses supports the idea that during the biotrophic phase, Z. tritici maintains an environment conducive to continued apoplastic growth and inhibiting host immune responses, thus favoring the efficient spread of Z. tritici. This data supports the establishment of a relatively high baseline transmission parameter β0 ≈ 0.55 for the SEIR simulations (which is used as an upper limit under optimal environmental conditions), which is supported by field (or site) calibrated models from Mediterranean wheat production systems [1]. Additionally, transcriptomic comparisons confirm that the expression of many resistance genes was inhibited in Z. tritici compatible interactions (including RPM1-like, RPP13-like, PR-14, and PR-7).

This transcriptional silencing allows the fungus to colonize the apoplast and inhibit recognition by the host’s immune system, which allows it to continue growing. This effect is consistent with a β0 value of 0.55 in SEIR models [43]. Similarly, the biological effect of effector proteins produced by Z. tritici also supports the idea that the use of this value for β0 is appropriate. Z. tritici has been shown to produce LysM domain proteins (i.e., Mg3LysM3, Mg1LysM2, Mgx1LysM3) that can bind to chitin, suppressing the host’s recognition of the fungus, while also protecting its hyphae from the hydrolytic enzymes produced by the host. As such, the use of this β0 value is also consistent with the fact that the mechanisms of immune suppression are related to increased colonization efficiency [42]. In addition, there is good agreement between initial transmission rates determined with SEIR simulations and estimated initial transmission rates for Z. tritici observed in untreated Mediterranean wheat systems (Thessaly, Greece). These simulations incorporate temperature, humidity, canopy structure and duration of the latent phase in their construction, and they have been verified by field observations of both the expansion of lesions and the density of pycnidia. The estimated upper limit for β0 under ideal conditions (0.55) is supported by Z. tritici documented epidemiological behavior and indicates realistic predictions for Mediterranean agroecosystems [1].

- Model Parameterization for P. tritici-repentis—baseline transmission rate β0

In P. tritici-repentis, the baseline transmission rate (β0 ≈ 0.38) was determined from the following: biological characteristics, residue (in the form of straw)-borne epidemiology and field calibrated model simulations of SEIR systems within the Mediterranean wheat systems. This is considered to be a moderate transmission potential in relation to Z. tritici, which has a shorter latent infection period and a more aggressive pathogenic lifestyle than the latter. Initial infections created from the release of ascospores by P. tritici-repentis into wheat straw residue will lead to a tan spot epidemic during the tillering (for example through GS23, rapid growth through GS31) and stem elongation stage of the plant [1]. The density of pseudothecia in the straw ranged from 4.4 pseudothecia per cm to 15.2 pseudothecia per cm, with a maximum perithecium producing 270 ascospores, thus representing a high level of inoculum pressure but limited canopy colonization state when compared with Z. tritici [1]. The comparative analyses and bibliometric synthesis of literature proposals further substantiate this parameterization.

P. tritici-repentis epidemic trends of increased severity have continued in Central Greece throughout 15 years of field observations and are primarily caused by climatic and other local conservation tillage anomalies [1,2]. However, the ability of P. tritici-repentis to spread quickly is limited by its ability to initially produce symptoms and lesions that quickly develop in small areas, thereby limiting the period of time for being able to spread infectious spores, and limiting secondary transmission opportunities. Fungicide evaluations with propiconazole and fluxapyroxad (Systiva®) indicate that early seed treatment suppresses the initial P. tritici-repentis transmission rate but does not eliminate the disease infection. SEIR simulations calibrated to these fungicidal evaluations estimate untreated P. tritici-repentis transmission paths as between 0.35 and 0.40 and indicate that Systiva® reduces β0 to below 0.30 during the initial 10 days after seed emergence from the soil [1]. Hence, assigning a value of β0 ≈ 0.38 when calculating disease spread probabilities, from the host and with no fungicide suppression, accounts for the ideal or best conditions when computing disease spread. In comparison, β0 represents the highest possible value of the basic transmission rate for disease spread under ideal or best conditions without the addition of chemical suppression. Also, β0 accounts for the biological aggressiveness of the pathogen, the susceptibility of the host, and environmental conditions of the crop canopy.

- Infection Dynamics Over Time, infection dynamics (I(t)) and epidemic growth rates (r(t))

The time patterns of infection (Table 3) indicate how the two pathogens, the foliar pathogenic fungus P. tritici-repentis in this example, respond to fungicide applications differently based on treatment applications. The peak incidence of P. tritici-repentis progressively increased with the seed treatment only, but it was nearly flat when the foliar treatment of propiconazole was added, producing a decrease of approximately 80% in peak incidence. The spread of Z. tritici was more aggressively expanded with the seed treatment only, and the combination treatment decreased peak incidence by approximately 65%. In conclusion, these findings illustrate the synergistic value of dual fungicide protective measures, especially for minimizing the rapid necrotrophic development of P. tritici-repentis as compared to the hemibiotrophic phase of Z. tritici, where they were only partially suppressed.

Table 3.

Infection dynamics of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis and Zymoseptoria tritici under seed treatment alone (Systiva®) and combined seed plus foliar fungicide (Systiva® + Propiconazole) across 10 days post BBCH 37.

In summarizing the two pathogens, Table 3 also shows the pattern of infection dynamics (I(t)) and epidemic growth rates (r(t)). Infection dynamics can be expressed as the percentage of leaf area that is infected; however, the r(t) value provides the growth rate of the pathogen on the same (percentage of leaf area) and provides insight as to whether the epidemic is growing (positive) or diminishing (negative). By providing both the IPM and fungal treatment, the combined treatment consistently decreased infection and transitioned the r(t) of the pathogens to the negative side of the graph, suggesting greater suppression of P. tritici-repentis and more moderate suppression for Z. tritici.

Daily SEIR updates were computed using the forward Euler scheme, and epidemic growth rates r(t) were derived to indicate whether transmission exceeded removal or suppression dominated infection dynamics.

The value r(1) = 0.124 (Table 3) indicates net epidemic expansion on Day 1 under seed treatment alone, consistent with the hemibiotrophic progression of Z. tritici. The calculation process for Day 1 values r(1) = 0.124 of Z. tritici are presented in the Section below entitled “Supplementary Materials; Calculations for Table 3”.

On Day 3, Z. tritici demonstrates an ongoing upward epidemic trend (r(3) ≈ +0.055) while relying solely on seed treatment as an environmental factor for infection expansion. These observations follow the hemibiotrophic life cycle of the fungus; it has a long latent period preceding rapid epidemic growth. However, when compared with Day 1 (r(1) = +0.124), the rate of increase in disease incidence is lower than was seen on Day 1 due to host tissue hardening and also due to residual activity of the seed treatment fungicide. However, the Z. tritici population continues to be in an upward growth state even in the presence of a fungicide. At the same time that Z. tritici is transitioning from a positive growth trend (Day 5) to a negative growth trend (Day 7), the impact of host resistance becomes more pronounced than that of fungicide effectiveness on the overall epidemic, and the reduction of Z. tritici’s expansion phase is much less dramatic than what would have been achieved with continuous foliar fungicide treatments (Days 5–7). If a foliar intervention had been applied around Days 5–7, it may have greatly enhanced the Z. tritici population decline and may have significantly impacted the peak disease burden at I(t) at some future time.

The data detailed in Table 3 on P. tritici-repentis indicate that for Scenario A (Systiva® alone) the incidence of infection increased progressively every day from Day 1 at 0.010 to Day 10 at 0.049, which demonstrates that even with seed-applied fungicide, the fungus continued to spread. In contrast, for Scenario B (Systiva® + Propiconazole) the incidence of infection was nearly unchanged, increasing from 0.008 to 0.010, which is an approximate 80% reduction in peak incidence of infection. For Z. tritici the incidence of infection in Scenario A increased sharply from 0.020 on Day 1 to 0.091 on Day 10 relative to its hemibiotrophic nature and long incubation period, whereas infection rates increased only from 0.015 to 0.033 and indicated an approximate 65% peak reduction in the rate of infection for Scenario B, demonstrating that the combined fungicidal activity is significantly superior to seed treatment alone, particularly with respect to limiting the rapid necrotrophic development of P. tritici-repentis; however, the activity of these products does not completely suppress the hemibiotrophic growth of Z. tritici.

Canopy architecture and crop development are significant determinants of whether a crop will develop severe foliar disease due to the influence they have on disease development and pathogen dispersal. Stem height, stem elongation rate, and leaf size are some traits influencing disease development. For example, taller stems will limit Septoria leaf blotch development on upper leaves due to their length [44,45]. Conversely, a dense canopy of stem elongation during stem development creates a microclimate conducive to both P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici during the stem elongation stage [44]. The two pathogens are typically co-infecting, with P. tritici-repentis predominating during the early and mid-season, while Z. tritici becomes more common during stem elongation up to flowering stage [46]. Foliar epidemics typically develop through repeated cycles of lesion formation and spore dispersal, which are influenced heavily by the degree to which rain can penetrate or be intercepted by canopy architecture and canopy microclimate [44]. Thus, as described above, the co-occurrence of P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici during stem elongation is facilitated by canopy architecture and the canopy microclimate, which are both conducive to the development of foliar epidemics [1,44].

The model predictions are in agreement with biological expectations that humid enclosed microclimates produced by a dense canopy during stem elongation accelerate the spread of both Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis, which allows for an increase in transmission rate β(t) and retained positive epidemic propagation when there is a lack of fungicide protection.

Over the 10-day duration following BBCH 37, Z. tritici was represented by an initial rapid increase in cases occurring under Scenario A (seed treatment only), followed by a plateau to equal growth in cases (r1 = +0.124, r3 = +0.055) and then inhibition on Day 5 (r5 = −0.007, Table 3) (the final report under Day 10 was r7 = −0.069, r10 = −0.162, Table 3). On the other hand, Scenario B (seed treatment plus foliar fungicide application) sustained comparable suppression of the disease consistently through all 10 days with negative rates (r1 = −0.08, r3 = −0.14, …, r10 = −0.17; Table 3).

Although Figure 1 focuses on the epidemic growth rate r(t), inspection of the underlying SEIR outputs confirmed that the infectious compartment I(t) behaved consistently with expected biological patterns. Under Scenario A, I(t) for Z. tritici increased slowly during the early days of the simulation, reflecting its hemibiotrophic latent phase, whereas P. tritici-repentis showed an earlier peak and a faster decline in I(t), consistent with its rapid necrotrophic progression. Under Scenario B, the values of I(t) remained uniformly lower for both pathogens (Table 3), demonstrating the stronger suppressive effect of the combined seed + foliar treatment. These trends indicate that the model behaves realistically across compartments, even though only r(t) is visualized for clarity.

Canopy-driven microclimate effects also make fungicide applications at GS37–39 an epidemiologically important option: at this growing stage, the rapidly closing canopy promotes humidity retention between leaves, and due to that effect, there is increased chance of leaf-to-leaf contact, which results in a higher β(t). Therefore, it is critical to provide timely foliar protection to prevent an increase in conditions that are conducive to an accelerated epidemic development.

P. tritici repentis reported similar negative r(t) figures for both scenarios, indicating that individual seed treatment allowed for complete control of disease development. Overall, using both seed and foliar applications resulted in more complete and lasting control of Z. tritici than individual application.

The observed dynamics of infection patterns are open to further investigation with respect to environmental and product efficacy conditions, as described in more detail below. Table 1 and Table 2 show each risk assessment conducted for the individual management scenarios, while Table 3 gives a direct side-by-side comparison of the management practices.

Table 3 value I(1) = 0.020; this indicates that on Day 1, approximately 2% of the leaf area was actively infectious. The increase from the initial I0 = 0.01 reflects the early progression of latent infections into the infectious stage, despite seed treatment. It shows that the epidemic is beginning to expand under favorable conditions. For Day 3, we first compute Day 2 using Day 1 parameters (to advance the state), then apply Day 3 parameters to reach Day 3.

So, by Day 3, I(3) = 0.045; the infectious leaf area has more than doubled compared to Day 1, reaching 4.5%. This rise demonstrates that Z. tritici continues to expand during its latent-to-infectious transition, consistent with its hemibiotrophic biology. The positive epidemic growth rate r(3) ≈ +0.055 confirms that transmission still outweighs removal at this stage, meaning the epidemic is actively building. The interpretation for Days 5, 7 and 10 for Z. tritici in Scenario A are as follows:

Day 5: I(5) = 0.072, r(5) ≈ −0.007 (Table 3). The infectious area reaches 7.2%, while the growth rate is near zero (slightly negative). This suggests a transition zone: transmission pressure is nearly balanced by removal, with early signs of suppression but no decisive decline yet.

Day 7: I(7) = 0.085, r(7) = −0.069 (Table 3). Infectious tissue increases to 8.5%, but r(t) is clearly negative. Suppression has begun—removal exceeds transmission—yet the accumulated burden from earlier expansion keeps I(t) elevated.

Day 10: I(10) = 0.091, r(10) = −0.162 (Table 3). Infectious area is 9.1%, and suppression intensifies (more negative r(t)). Despite strong negative momentum, I(t) remains high due to prior growth; without foliar intervention, decline is delayed, and residual disease persists.

- Numerical Computation of r(t) for Z. tritici in Scenario A. Day-by-day computation of r(t) for Z. tritici under Scenario A

To quantify the daily rate of the epidemic, we computed the epidemic growth rate r(t) derived from the SEIR framework. At each time t, r(t) is defined as

This formulation expresses the balance between new infections (driven by the transmission rate β(t) and the proportion of susceptible tissue S(t) and removal of infectious tissue at rate γ(t).

- If r(t) > 0, the epidemic expands, as transmission outweighs removal.

- If r(t) < 0, the epidemic is suppressed, as removal dominates transmission.

- If r(t) ≈ 0, the epidemic is in equilibrium, with no significant expansion or decline.

The daily values of β(t), S(t), and γ(t) are estimated from environmental modulation (temperature, humidity), fungicide decay functions, and pathogen-specific latent and infectious periods. By substituting these values into the above equation, we obtain the stepwise estimates of r(t) reported in Table 2.

This dynamic indicator complements the compartmental outputs: while I(t) reflects the realized infectious burden, r(t) reveals the underlying epidemic trajectory, showing whether the disease pressure is building or being suppressed under the seed-treatment scenario.

- Day 1 example: Zymoseptoria tritici under Scenario A (Systiva only, Table 3)

Given initial conditions,

Transmission on Day 1, β(1): Using the exponential decay with environmental scaling,

with

Susceptible leaf area on Day 1, S(1): Theoretical exponential hardening (for context):

Empirical (from calibrated SEIR simulation used in the Table 1):

Recovery rate on Day 1, γ(1): Defined as inverse infectious period,

Epidemic growth rate on Day 1, r(1): Using the SEIR-based indicator,

Substituting the empirical S(1),

The positive value r(1) = 0.124 (Table 3) indicates that on Day 1 transmission outweighs removal. In practical terms, the epidemic is expanding: Z. tritici continues to increase its infectious leaf area despite seed treatment.

- Day 3 example: Zymoseptoria tritici under Scenario A (Systiva only, Table 3)

Transmission rate β(3): From the table, the calibrated value is:

Susceptible leaf area S(3): Theoretical exponential decay:

Empirical (field-calibrated SEIR simulation):

Recovery rate γ(3): From the infectious period estimate (D ≈ 4.1 days),

Epidemic growth rate r(3): Using the SEIR expression,

Substituting empirical values S(3),

For Day 3, the epidemic growth rate r(3) ≈ +0.055 (Table 3) is slightly positive, meaning transmission still outweighs removal. The infection continues to expand, consistent with the pathogen’s latent-to-infectious transition.

For Day 5, it can be seen that the growth rate r(5) (approximately −0.007, Table 3) is nearing zero and thus there is a change in direction; this indicates a point of transition. Transmission is now roughly equal to removal, resulting in a decrease in the rate of increase (growth) of the epidemic. On Day 7, the negative growth rate value r(7) is approximately −0.069 (Table 3), which indicates a period of suppression; at this point, removal is more prevalent than transmission. While the volume of infected tissue remains elevated, the velocity of the epidemic (momentum) has now begun to decline. On Day 10, suppression of the growth rate has increased significantly (r(10) = approximately −0.162, Table 3), with removal being the dominant activity relative to transmission. Additionally, it is very clear that the trajectory of the epidemic has moved downward, but some level of infection burden still exists due to prior growth of the epidemic.

These results provide practical guidance for wheat disease management, as the clear differences between the two fungicide strategies offer a quantitative basis for optimizing application timing around BBCH 37. Although parameterized for Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis, the SEIR framework is readily transferable to other foliar pathosystems with known latent, infectious, and fungicide decay characteristics, supporting broader use in disease control decision-making.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The development of a biologically accurate SEIR framework allows researchers to simulate how two foliar diseases will evolve over winter wheat during the crucial growth stage of BBCH 37. This model integrates pathogen characteristics, environmental influence, and fungicide decay rates to represent realistic fungal disease pressures across different time intervals during this vulnerable stage of wheat development. Seed treatment with the commercial fungicide Systiva®, which contains fluxapyroxad, contributes to early-season suppression of P. tritici repentis, while a BBCH 37-timed foliar propiconazole application enhances overall disease management. The model indicates that the combination of systemic seed protection with the targeted foliar application has had a positive synergistic effect for the entire 10-day simulation period, as evidenced through negative r(t) values and lower infectious leaf area dynamics. This dual approach supports the principles of Integrated Disease Management and is supported by field trial data obtained from Thessaly, Greece. Three independent studies have empirically validated these findings: (i) Vagelas et al. (2022) [1] reported that Systiva® seed treatment reduced the severity of foliar disease and enhanced the vigor of canopies subjected to early season climate stress; (ii) Vagelas et al. (2025) [19] confirmed the utility of SDHI fungicides in suppressing tan spot and Septoria leaf blotch, with substantially decreased disease severity during tillering and stem elongation; and (iii) Vagelas (2025) [2] found Systiva®-treated plots to have higher tiller density and lower infection incidence, supporting the model’s initial conditions and intervention parameters. These studies, conducted under minimum tillage and natural inoculum pressure, provide direct evidence for the modeled decrease in transmission rate (β), increase in removal rate (γ), and early suppression of the epidemic growth rate r(t). Overall, the dynamic calculation of r(t) offers a sensitive and interpretable measure of epidemic disease rate and reflects how environmental factors and management practices influence disease dynamics.

From a practical aspect, this research shows the value of combining seed treatment with foliar fungicide application timed to canopy closure, a period that provides microclimatic conditions favorable to foliar pathogens’ development. The use of the SEIR model further underscores the need for pathogen-specific strategies, as illustrated by the different responses of P. tritici-repentis and Z. tritici to the fungicides evaluated. Scenario analysis (Table 1 and Table 2) presents additional insights into fungicide application strategy. In the case of seed treatment alone, Z. tritici maintains a positive epidemic growth rate beyond BBCH 37, reflecting its hemibiotropic nature and longer latent period, whereas P. tritici-repentis shows growth rates at or near zero or slightly negative, indicating partial suppression. When foliar propiconazole was included for both pathogens, consistently negative growth rates were observed, suggesting that combining seed treatment with foliar propiconazole enhances suppression by reducing transmission and accelerating pathogen removal. The data also indicate that while Z. tritici shows a hemibiotrophic pathogen response to fungicides and P. tritici-repentis a necrotrophic one, effective fungicide strategies require alignment with pathogen biology to achieve maximum suppression. Furthermore, Table 3 provides a side-by-side comparison illustrating the added benefit of incorporating a foliar fungicide.

Environmental conditions and fungicide practices strongly influence the development of Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis, as reflected in their different prevalence patterns, shown in Table 3. Z. tritici was able to germinate and produce mycelium under the favorable moisture and temperature conditions present at BBCH37, meeting the environmental requirements for successful infection [29,30] under Scenario A (seed treatment). As time progressed, the decline in r(t) values indicates the duration over which seed-applied treatments provided protection before their effectiveness gradually diminished. When seed and foliar applications were combined (Scenario B), the continued decline in r(t) values demonstrated the added effectiveness of foliar application of propiconazole in limiting fungal growth under conditions already suitable for P. tritici-repentis [31,47]. Both seed and foliar applications reduced r(t) values, indicating a lower potential for disease progression, with P. tritici-repentis responding more readily due to its lower moisture requirements compared with Z. tritici. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of considering environmental conditions together with management practices when evaluating the epidemiological course of an epidemic.

Both agronomists and farmers can use rate of epidemic growth r(t) as a practical indicator of disease pressure when optimizing the timing of fungicide applications; consequently, r(t) also reflects how frequently fungicides may need to be applied. Beyond its economic relevance, r(t) serves as a dynamic measure that integrates pathogen biology with the environmental factors influencing pathogen development, thereby supporting decision-making within integrated disease management systems for wheat grown in Mediterranean environments.

The scenario analysis aspect of this research enables users to explore the potential influence of cultivar-resistance, canopy architectural variations, and structural differences among pathogen races. Molecular diagnostic testing and the monitoring of effector genes [48] provide improved capabilities for making predictive assessments, while long-term simulations using variability associated with climate change provide insight into the need for adaptive management strategies for Mediterranean and semi-arid wheat systems.

As outlined in previous sections, this research provides a coherent framework for predicting the development of diseases at the leaf level in by integrating field data with epidemiological concepts. This approach supports more precise fungicide application within integrated pest management practices, while also contributing to the continued advancement and refinement of scientifically supported methods in phytopathology, particularly as production systems adapt to ongoing climatic changes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agrochemicals5010010/s1, S1. Calibration of Baseline Transmission Rate (β0) for Z. tritici and P. tritici-repentis; S2. Table S1. Classification of SEIR Model Parameters According to Their Origin; S3. Calculations for Table 3—Stepwise Calculation of I(t) and r(t) under Scenario A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vagelas, I.; Cavalaris, C.; Karapetsi, L.; Koukidis, C.; Servis, D.; Madesis, P. Protective effects of Systiva® seed treatment fungicide for the control of winter wheat foliar diseases caused at early stages due to climate change. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I. Efficacy of Systiva® seed treatment in managing tan spot and Septoria leaf blotch in winter wheat. Mod. Concepts Dev. Agron. 2025, 15, MCDA.000864. [Google Scholar]

- Bouras, N.; Kim, Y.M.; Strelkov, S.E. Influence of water activity and temperature on growth and mycotoxin production by isolates of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis from wheat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, R.; Miguel-Rojas, C.; Lorite, I.J.; Pérez-de-Luque, A.; Sillero, J.C. Characterization of Durum Wheat Resistance against Septoria Tritici Blotch under Climate Change Conditions of Increasing Temperature and CO2 Concentration. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiak, S.F.; Arseniuk, E.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Bartosiak, E. Monitoring of Natural Occurrence and Severity of Leaf and Glume Blotch Diseases of Winter Wheat and Winter Triticale Incited by Necrotrophic Fungi Parastagonospora spp. and Zymoseptoria tritici. Agronomy 2021, 11, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissaoui, S.; Omri-Benyoussef, N.; Chaar, H.; Hassine, M.; Venisse, J.; Nasraoui, B.; Mougou-Hamdane, A. Progression of wheat Tan spot under different bioclimatic stages and agricultural practices. Plant Prot. Sci. 2023, 59, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.W.; Osborne, T.M. Geographic distribution of plant pathogens in response to climate change. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.A.; Nita, M.; Wolf, E.D.; Esker, P.D.; Gomez-Montano, L.; Sparks, A.H. Plant pathogens as indicators of climate change. In Climate Change (Second Edition): Observed Impacts on Planet Earth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Mukhopadhyay, R. Climate change and plant pathogens: Understanding dynamics, risks and mitigation strategies. Plant Pathol. 2024, 74, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, E.; Platz, G.J.; Usher, T.R. Fungicidal control of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis in wheat. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2003, 32, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildea, S.; Heick, T.; Hutton, F.; Bataille, C.; Aldén, L.; Kaneps, J.; Mäe, A.; Weigand, S.; Zajc, J.; Walker, A.S.; et al. Prevalence of key resistance alleles associated with DMI and SDHI fungicide resistance in European Zymoseptoria tritici populations in 2022. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heick, T.M.; Justesen, A.F.; Jørgensen, L.N. Anti-resistance strategies for fungicides against wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici with focus on DMI fungicides. Crop Prot. 2017, 99, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrukaitė, K.; Almogdad, M.; Ramanauskienė, J.; Sabeckis, A. Sensitivity of Lithuanian Zymoseptoria tritici to Quinone Outside Inhibitor and Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor Fungicides. Agronomy 2024, 14, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birr, T.; Hasler, M.; Verreet, J.; Klink, H. Temporal Changes in Sensitivity of Zymoseptoria tritici Field Populations to Different Fungicidal Modes of Action. Agriculture 2021, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, E.M.; Hill, E.M.; Parnell, S. Modelling the effectiveness of Integrated Pest Management strategies for the control of Septoria tritici blotch. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I. Important Foliar Wheat Diseases and their Management: Field Studies in Greece. Mod. Concepts Dev. Agron. 2021, 8, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarra, N.; Colturato, M.; Fernández, J.R.; Naso, M.G.; Simonetto, A.; Gilioli, G. Analysis of a Mathematical Model Arising in Plant Disease Epidemiology. Appl. Math. Optim. 2022, 85, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I. Effective strategies for managing wheat diseases: Mapping academic literature utilizing VOSviewer and insights from our 15 years of research. Agrochemicals 2025, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I.; Sourlas, A.; Cavalaris, C. SDHI fungicides: An important step in maintaining control of tan spot and Septoria leaf blotch diseases of wheat. J. Environ. Sci. Sustain. Green Innov. 2025, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunniffe, N.J.; Laranjeira, F.F.; Neri, F.M.; DeSimone, R.E.; Gilligan, C.A. Cost-Effective Control of Plant Disease When Epidemiological Knowledge Is Incomplete: Modelling Bahia Bark Scaling of Citrus. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunniffe, N.J.; Koskella, B.; Metcalf, C.E.; Parnell, S.R.; Gottwald, T.; Gilligan, C.A. Thirteen challenges in modelling plant diseases. Epidemics 2015, 10, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.A.; Liu, F.; Burrage, P.M.; Burrage, K.; Li, T. Novel analytical and numerical techniques for fractional temporal SEIR measles model. Numer. Algorithms 2017, 79, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.W. Effects of temperature, leaf wetness and cultivar on the latent period of Mycosphaerella graminicola on winter wheat. Plant Pathol. 1990, 39, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, M.C.; Michaelson, L.V.; Parker, J.E.; Kelly, S.L.; Thacker, U.; Powers, S.J.; Bailey, A.M.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Courbot, M.; Rudd, J.J. Analysis of cytochrome b5 reductase-mediated metabolism in the phytopathogenic fungus Zymoseptoria tritici reveals novel functionalities implicated in virulence. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 82, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, L.L.; Bernier, C.C. Evaluation of wheat lines and cultivars to tan spot [Pyrenophora tritici-repentis] based on lesion type. Can. J. Plant Pathol.-Rev. Can. Phytopathol. 1989, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelkov, S.E.; Lamari, L.L. Host–parasite interactions in tan spot [Pyrenophora tritici-repentis] of wheat. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 25, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AHDB. Practical Measures to Combat Fungicide Resistance in Pathogens of Wheat; Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board: Coventry, UK, 2023; Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Baazeem, A.S.; Nawaz, Y.; Arif, M.; Abodayeh, K.; AlHamrani, M.A. Modelling Infectious Disease Dynamics: A Robust Computational Approach for Stochastic SIRS with Partial Immunity and an Incidence Rate. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miñana-Posada, S.; Feurtey, A.; Alassimone, J.; McDonald, B.A.; Lorrain, C. Responses to temperature shocks in Zymoseptoria tritici reveal specific transcriptional reprogramming and novel candidate genes for thermal adaptation. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boixel, A.-L.; Gélisse, S.; Marcel, T.C.; Suffert, F. Differential tolerance of Zymoseptoria tritici to altered optimal moisture conditions during the early stages of wheat infection. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 104, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadi Gohari, A.; Ghiasi Noei, F.; Ebrahimi, A.; Ghanbari, M.A.; Didaran, F.; Farzaneh, M.; Mehrabi, R. Physiological and molecular responses of a resistant and susceptible wheat cultivar to the fungal wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, M.; Van-Dierdonck, J.B.; Stollenwerk, N. Reproduction ratio and growth rates: Measures for an unfolding pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Nelson, A.; Willocquet, L.; Pangga, I.; Aunario, J. Modeling and mapping potential epidemics of rice diseases globally. Crop Prot. 2012, 34, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.; Hijmans, R.; Savary, S.; Pangga, I.; Aunario, J. epicrop: Simulation Modelling of Crop Diseases Using a Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Removed (SEIR) Model, R Package Version 1.0.0.9000; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, E.A.; Chakraverty, S.; Potucek, R. Numerical Solution of an Interval-Based Uncertain SIR (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered) Epidemic Model by Homotopy Analysis Method. Axioms 2021, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanov, D. Analytical solutions and parameter estimation of the SIR epidemic model. In Mathematical Analysis for Infectious Disease Modeling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, B.; Burchard, H. Rosenbrock methods in biogeochemical modelling—A comparison to Runge–Kutta methods and modified Patankar schemes. Ocean Model. 2011, 37, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F.; Bakan, H.Ö.; Weber, G. Strong-order conditions of Runge-Kutta method for stochastic optimal control problems. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 157, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, A.; Paveley, N.; Audsley, E.; Livermore, P. A wheat canopy model for use in disease management decision support systems. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2003, 143, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, A.E.; Paveley, N.D.; Audsley, E.; Parsons, D.J. A model of the effect of fungicides on disease-induced yield loss, for use in wheat disease management decision support systems. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007, 151, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.M.; Garrett, K.A.; Bowden, R.L.; Fritz, A.K.; Dendy, S.P.; Heer, W.F. Cultivar mixtures for the simultaneous management of multiple diseases: Tan spot and leaf rust of wheat. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meile, L.; Carrasco-López, C.; Lorrain, C.; Kema, G.H.; Saintenac, C.; Sánchez-Vallet, A. The molecular dialogue between Zymoseptoria tritici and wheat. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2024, 38, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Fagundes, W.C.; Stukenbrock, E.H. Comparative Transcriptomic and Microscopic Analyses of a Wild Wheat Relative Reveal Novel Mechanisms of Immune Suppression by the Pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2025, 38, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Fournier, C.; Andrieu, B.; Ney, B. Coupling a 3D virtual wheat (Triticum aestivum) plant model with a Septoria tritici epidemic model (Septo3D): A new approach to investigate plant-pathogen interactions linked to canopy architecture. Funct. Plant Biol. FPB 2008, 35, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Garin, G.; Abichou, M.; Houlès, V.; Pradal, C.; Fournier, C. Plant architecture and foliar senescence impact the race between wheat growth and Zymoseptoria tritici epidemics. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.S.; Gibberd, M.R.; Hamblin, J. Co-infection of wheat by Pyrenophora tritici-repentis and Parastagonospora nodorum in the wheatbelt of Western Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2020, 71, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, C.A.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Matzen, N.; Heick, T.M.; O’Driscoll, A.; Clark, B.; Waite, K.; Blake, J.; Glazek, M.; Maumene, C.; et al. Shifting sensitivity of Septoria tritici blotch compromises field performance and yield of main fungicides in Europe. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1060428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.; Cherif, M.; Hafez, M.; Despins, T.; Aboukhaddour, R. Pyrenophora tritici–repentis in Tunisia: Race Structure and Effector Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.