Abstract

Breast cancer is a substantial and growing public health issue in India, with epidemiological data demonstrating distinct and often severe disease characteristics in contrast to Western countries. Contrary to the global trend, Indian women frequently develop the disease at an earlier age and tend to present with more advanced stages, emphasizing important variations in disease pathophysiology. This review compiles and critically evaluates the current literature to describe the specific pathophysiology of breast cancer in the Indian population. We investigate the unique cellular and molecular landscapes, evaluate the impact of specific Indian demographic and genetic features, and highlight crucial gaps in knowledge, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic approaches. The assessment reveals a molecular landscape determined by the incidence of specific tumor subtypes; triple-negative breast cancer, for instance, is frequently diagnosed in younger women, and genetic profiling research suggests variations in its susceptibility genes and mutation patterns when compared to global populations. While this paper brings together recent advancements, it highlights the challenges of adopting global diagnostic and treatment guidelines in the Indian healthcare system. These challenges are largely due to variances and specific demographic and socioeconomic discrepancies that create substantial hurdles for timely diagnosis and patient care. We highlight significant gaps, such as the need for more complete multi-omics profiling of Indian patient cohorts, an absence of uniform and readily available screening programs, and shortcomings in healthcare infrastructure and qualified oncology experts. Furthermore, the review highlights the crucial need for therapeutic strategies tailored to the distinct genetic and demographic profiles of Indian breast cancer patients. We present significant strategies for addressing these challenges, with a focus on integrating multi-omics data and clinical characteristics to gain deeper insight into the underlying causes of the disease. Promising avenues include using artificial intelligence and advancements in technology to improve diagnostics, developing indigenous and affordable treatment options, and establishing context-specific research frameworks for the Indian population. This review also underlines the necessity for personalized strategies to improve breast cancer outcomes in India.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) continues to pose a major public health challenge globally, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases and 685,000 deaths reported worldwide in 2020. While the incidence rates are high in developed countries, the burden is growing rapidly in developing nations such as India. In fact, in India, BC has surpassed other type of cancers to become the most common among women, with concerning forecasts for future incidence and mortality [1]. A notable and significant contrast in the Indian demographic is the average age at diagnosis, which is roughly ten years younger than in Western populations. Additionally, greater percentage of patients are diagnosed with more severe or aggressive characteristics, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [2]. Effective management of cancer involves more than just treating the physical illness; it also needs to consider the enormous psychosocial burden that patients suffer. Being diagnosed with and treated for BC can be deeply distressing, with a high incidence of psychiatric morbidities, including sadness and anxiety. This aside, unmanaged psychological distress, including depression, has shown to adversely affect a patient’s quality of life, adherence to treatment regimens, and survival rates [3].

Breast cancer is an extremely diverse disease; its underlying molecular basis and receptor types primarily determine its prognosis and response to therapy. The global perspective of BC molecular subtypes (luminal A/B, HER2+, and TNBC) often guides therapeutic regimens. Nevertheless, research indicates that the prevalence of these subtypes differs greatly by ethnicity [4]. In India, aggressive subtypes, particularly TNBC, are reported at a higher rate than in Western countries. Additionally, distinct genetic susceptibilities, including particular mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, along with other novel gene variants, have been discovered in the diverse Indian gene pool, potentially influencing the early onset and severe progression of the disease. The complete scope and significance of this unique cellular and molecular landscape remains under explored.

This unique Indian BC clinical picture indicates possible variations in the underlying cellular and molecular etiology. Understanding these distinct abnormalities at the genetic and epigenetic levels is critical, as global data and treatment regimens may not be completely applicable to the Indian subcontinent. Regardless of the growing burden and apparent biological disparities, there are considerable gaps in our knowledge and management of BC in India. A key problem is the lack of a comprehensive national cancer registry and large-scale etiological research to determine the causes of early onset and distinct molecular profiles [5]. Setting this aside, diagnostic strategies are often hampered by poor public awareness and limited access to structured screening programs, which results in more advanced diagnoses. In terms of treatment, although there are internationally recognized guidelines, the expensive nature of specialized therapies (such as Trastuzumab), coupled with uneven distribution across the country, reveals significant healthcare inequities, creating a gap in effective treatment for all patients [6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for research aimed at developing and validating new biomarkers, and for innovative treatment approaches for the Indian population.

Nonetheless, the emergence of frontier technological innovations provides hope for addressing these challenges. For example, programs like the Bharat Cancer Genome Atlas are tailoring advanced techniques, including large-scale genomics and multi-omics profiling to the heterogeneous Indian population [7]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is transforming diagnostic options, enabling enhanced image examination and forecasting models tailored to the specific patient demographics of India. These advancements, featuring affordable screening tools, signify an essential progress towards more equitable and efficient cancer treatment.

This review integrates current knowledge of the distinct pathogenesis of breast cancer among the Indian population. It provides an overview of its diverse cellular and molecular landscape in comparison to global understanding and investigates the interplay of demographic, genetic, and environmental factors influencing these discrepancies. Additionally, this paper detects and examines crucial knowledge gaps in the current understanding of the diagnostic procedures and therapeutic strategies in the Indian subcontinent. It also proposes directions for future research and policy changes to improve patient outcomes. Finally, this review will highlight the recent developments and proposes significant future prospects, with an emphasis on Indian-specific innovations in genomics, multi-omics profiling, and artificial intelligence.

2. Breast Cancer Landscape from Indian Epidemiological Context

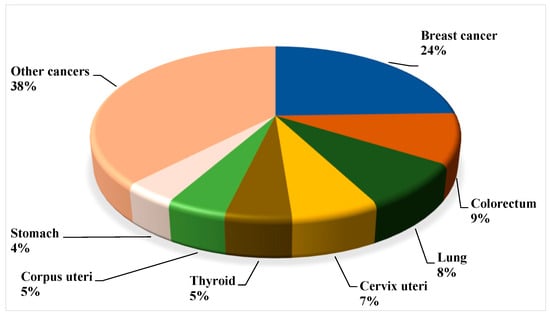

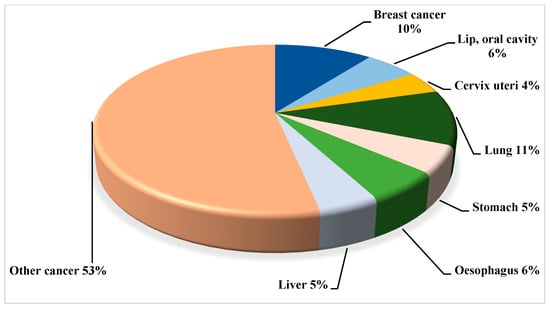

Breast cancer, as mentioned above, is the most common malignancy in women worldwide. With an estimated 2.3 million new cases, accounting for 11.7% of all cancer cases, it has in fact overtaken lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer incidence worldwide in 2020 [8]. According to epidemiological studies, the global implication and significance of BC is projected to surpass nearly 2 million by 2030 [9]. Especially, looking at the circumstance through an Indian perspective, the prevalence has escalated substantially, by nearly 50% between 1965 and 1985 [10]. To further illustrate this, in 2016 the predicted number of incident cases in India was 118,000 (with 95% confidence interval, 107,000 to 130,000), with women accounting for 98.1% of the total, and prevalent cases accounting for 526,000 (474,000 to 574,000). To highlight the severity, from 1990 to 2016, the age-standardized frequency rate of BC in women augmented by 39.1% (95% CI, 5.1 to 85.5), with an upsurge detected in every state of the country [11]. In fact, according to the Globocan data 2020, BC reckoned for 10% (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [12].

Figure 1.

Globally assessed novel cancer cases among women in 2020 (all ages), based on the data from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020).

Figure 2.

Projected relative cancer burden (based on Disability Adjusted Life Years—DALYs) in India for 2030; data based on the sources such as the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN).

In light of the facts presented, and in accordance with the existing trends, a fairly elevated proportion or incidence of the disease was seen to manifest among younger age groups among the Indian women in contrast to their Western counterparts. Furthermore, the National Cancer Registry Program investigated the statistical records from cancer depositories and registries between the years 1998 and 2013 in order to scrutinize the diversity and fluctuation in cancer prevalence. Eventually, the outcomes that ensued from the above examinations in fact revealed a compelling rise in trend of BC. In 1990, the cervix was the prominent site of cancer in India, followed by BC, in Bangalore (23.0% vs. 15.9%), Bhopal (23.2% vs. 21.4%), Chennai (28.9% vs. 17.7%), and Delhi (21.6% vs. 20.3%), respectively, whereas the breast was the prominent site of cancer in Mumbai (24.1% vs. 16.0%), as reported from the above registries. However, from 2000 to 2003 the scenario changed, with breast cancer becoming the prominent cancer site in all registries except the Barshi rural registry (16.9% vs. 36.8%). And noticeably in the case of BC, the registries in Bhopal, Chennai, and Delhi showed a considerable rising trend [13].

To further illustrate the point of conformity, patients with breast cancer have a lower survival rate in India than in Western countries, owing to their early age at the time of onset, the delayed initiation of specific and precise supervision, the late stage of the disease at the time of presentation, and ineffective/imploded treatment regimens [14].

3. Overall Global Understanding of Breast Cancer with the Indian Demographic Characteristics

3.1. Gaps in Knowledge

Compared to Western populations, Indian women have distinct BC characteristics, such as a higher incidence of premenopausal cases, a higher percentage of advanced-stage diagnoses, and a younger average age of diagnosis (40–50 years vs. 60–70 years). Moreover, there is evidence that triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is more common in India [15]. In addition, although BRCA1/2 mutations are known risk factors, studies indicate that Indian BC patients may have a higher incidence of these mutations than Western populations, as well as indicating a notable role for non-BRCA genes that warrants additional research.

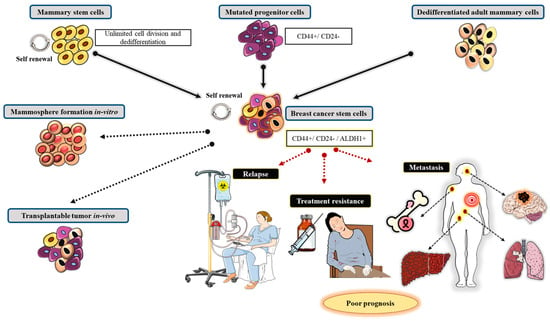

In India, immense knowledge gaps persist regarding the precise role and function of cancer stem cells (CSCs), particularly in tumor development and progression. These gaps encompass the understanding of the basic attributes and prevalence of CSCs among Indian breast cancer patients. Epigenetic and genetic factors, distinctive to the Indian population, consequently modify CSC function, ultimately impacting therapeutic strategies that target CSCs [16]. Understanding the heterogeneity of cancer stem cells (CSCs) across various breast cancer (BC) subtypes in India and their interaction with the tumor microenvironment is undeniably crucial. This knowledge will enhance therapeutic strategies and improve treatment outcomes. Furthermore, developing these strategies necessitates a deep understanding of how this heterogeneity differs among BC subtypes in India. Therefore, more research is required to pinpoint the precise pathways and mechanisms influencing CSC behavior in these different subtypes. A collaborative, interdisciplinary approach uniting scientists, healthcare professionals, and experts in cell biology, cancer genomics, and pharmacology can bridge these knowledge gaps and illuminate the complexities of CSC biology and its role in BC in India [16].

Similarly, for precise risk assessment, timely diagnosis, and the development of precision/personalized medicine, it is essential to comprehend the unique molecular and genetic characteristics among the Indian breast cancer patients. In fact, studies are underway to determine distinct mutations (e.g., TP53 and PIK3CA) and their possible effects for personalized treatment approaches [17].

In India, socioeconomic and cultural barriers—including stigma, lack of awareness, and financial hardship—contribute to delayed breast cancer diagnosis and worse outcomes, particularly in rural regions. Therefore, to acquire a thorough understanding about the predisposing factors for BC among Indian women, studies should investigate the relationship between cultural traditions, lifestyle modifications, and genetic predispositions, which are deeply rooted in one another. This aside, with the fair amount of evidence corroborating the implication of environmental factors and lifestyle modifications, research demonstrates possible connections between BC risk and environmental pollutions in air and water, along with urbanization, dietary habits, lack of physical activity, etc., [18].

3.2. Gaps in Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches or Methodologies

Despite the fact that early detection of BC makes it treatable, numerous gaps in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches result in higher death rates in India than in Western nations. These disparities are especially apparent when taking into account the distinct demographics and the socioeconomic status of the Indian population as discussed below.

In terms of diagnostics, there is limited access to screening and uptake, regardless of some governmental initiatives. Breast cancer screening program participation is very low, particularly among lower socioeconomic groups and in rural regions. This could be because of a lack of knowledge and awareness, as several women are oblivious about the signs of BC and the significance of early identification [19]. Logistical challenges such as a lack of transportation, a long remote distance to screening amenities, and the necessity for a personal care assistant or attendant further hinder easy access, especially for women from rural areas [20]. This aside, Indian women typically have denser breast tissue which may make the common screening procedures, like mammography, less effective.

In addition, given all the specific and unique BC characteristics among the Indian population, there is an immense need for biomarkers that are specific to the Indian population. Therefore, additional studies and research are needed to detect genetic and epigenetic biomarkers unique to the Indian demography for timely discovery and for further individualized screening approaches [19].

Also given the severity from the genetic and molecular heterogeneity standpoint, the role of tumor microenvironment heterogeneity (TME) has a major impact on treatment resistance, metastasis, and tumor progression. Indeed, research studies focusing on the unique traits and variability of the TME among the Indian BC patients will be vital [1].

Similarly, from limited genetic testing perspective, regardless of the fact that BRCA mutations are more common in India, there is little access to genetic testing and counseling. In addition, further study is needed to determine the clinical significance of variations of unknown significance (VUS) mutations among the Indian population in order to guide treatment selection strategies [21].

However, from therapeutics standpoint, despite the recent medical advances, there is still very few high-quality, multimodal treatment centers, particularly in rural areas. The overall burden is compounded by a severe lack of medical resources, including proper infrastructure and essential equipment like radiotherapy units, and a shortage of qualified oncology specialists. Inadequate care from non-oncologists and financial restrictions lead to high rates of treatment attrition. Furthermore, the scope is complicated by limited access to expensive, novel therapies such as immunotherapy and personalized medicine [22].

On the other hand, with the inadequate studies and reports available on cancer biology from epidemiological and factors unique to India, additional research is crucial to define the frequency of molecular subtypes of BC. This, in turn, will help determine the precise genetic and environmental features that contributes to the disease. In addition, given the severity, and notwithstanding the detailed cancer surveillance initiatives, there is a lack of valid and detailed information on frequency, incidence, and mortality, which in turn impedes the implementation of successful public health interventions.

Therefore, addressing the above gaps implies the essential need to promote better public awareness, and to sensitize the public especially women about the signs and risk factors of BC, as well as the significance of early and prompt detection. Reinforcing and reducing the barriers to screening resources and services through community-centered programs, collaborations with primary healthcare personnel, and mobile screening camps may further help overcome the geographical and socioeconomic obstacles. Improving the BC management landscape requires strategic investment in healthcare personnel training, medical device accessibility, and cancer center expansion. Concurrently, enhancing policy measures—specifically through reinforced national policies, higher healthcare funding, and streamlined financial aid—is vital for addressing current shortcomings.

Ultimately, to devise successful prevention and treatment strategies, further studies and research comprising a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of BC in terms of genetics, environments, and lifestyle from Indian context, are crucial. This may, in turn, highlight the importance of investing in personalized medicine and tailored treatment approaches.

4. Genetics and Genomics: Implication of Genetic Susceptibility as a Significant Risk Factor for Breast Cancer

Essentially, a risk factor is something that affects the likelihood of developing breast cancer (BC). However, some major risk factors for BC are beyond an individual’s control, such as gender and age. For example, the disease is about 100 times more common in women than in men, and the majority of breast cancers are diagnosed in women aged 55 and older, illustrating that aging increases risk. Additionally, having a first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) diagnosed with BC almost doubles a woman’s possibility of developing it [23,24].

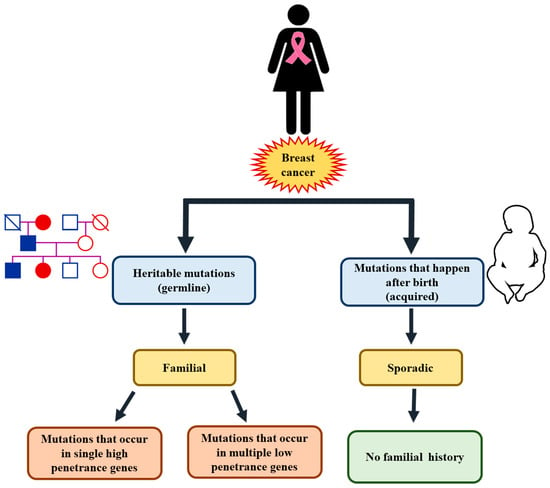

In general, genetic mutations acquired from a parent are linked to about 5–10% of BC cases. And, in fact, an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene is the most common cause of hereditary BC [25]. This aside, women with a BRCA1 mutation pose a 55–65% lifetime possibility of developing BC. And on the other hand, the lifetime possibility for women with a BRCA2 mutation is about 45%. Furthermore, a woman with both BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation has a 70% possibility of developing BC by the age of 80. BRCA1/2 mutations significantly increase lifetime breast cancer (BC) and ovarian cancer risks, with affected individuals often diagnosed at a younger age. The risk of developing BC in the contralateral breast is also elevated. A positive family history further correlates with increased risk. Specific risks vary by gene: BRCA1 mutations are rarely associated with male breast cancer, while BRCA2 mutations carry a modest lifetime male BC risk of approximately 6.8% [25] (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Genetic susceptibility as a significant risk factor for breast cancer.

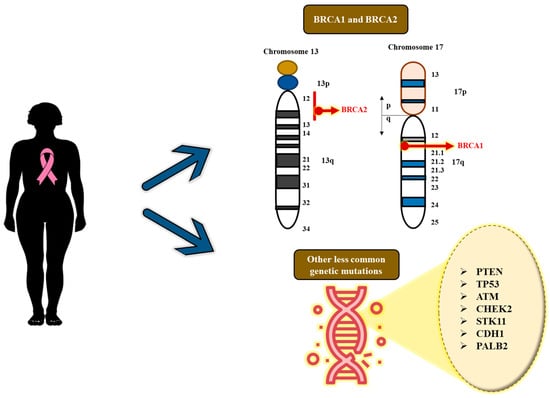

Figure 4.

Significant genetic mutations in breast cancer.

This aside, genetic mutations in numerous other genes can also lead to the development of BC, though they are less common than the BRCA mutations and the possibility of developing BC risk is relatively low [25]. A few of these mutated genes include PTEN (mutations acquired from this gene can result in Cowden’s syndrome, along with the susceptibility to non-cancerous and cancerous tumors in the breasts, in addition to growths in the thyroid, digestive tract, ovaries and uterus), TP53 (mutations of this gene results in Li-Fraumeni syndrome with an augmented susceptibility to BC, and few other cancers like leukemia, brain tumors, and sarcomas), ATM (acquiring two aberrant copies of this gene causes the disease ataxia–telangiectasia), CHEK2 (mutations in this gene can increase the liability to BC by approximately twofold), STK11 (mutations in this gene can result in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome with an increased susceptibility to several other types of cancer in addition to BC), CDH1 (these genetic mutations can result in the genetic diffuse gastric cancer with high predisposition to the invasive lobular BC), and finally PALB2 (this gene generates a protein that binds with the protein made by the BRCA2 gene, consequently resulting in mutations in this gene with a higher risk of BC) [25].

Genetic screening for mutations in genes like BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN, and TP53 is beneficial for timely breast cancer (BC) detection and prevention in high-risk women. However, it is crucial to understand the limitations and potential drawbacks of these tests. Furthermore, the high cost of genetic testing means it is not universally applicable, and its practical use should be weighed carefully as not all women require this screening [25].

Moreover, in the context of the Indian scenario, studies indicate that Indian BC patients have a considerably higher frequency and prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations when compared to their Western counterparts, with one study indicating a prevalence of 29.1%. However, among the Western populations, the incidence of these mutations is normally between 5 and 10%. Additionally, although BRCA mutations are linked to early-stage BC worldwide, the association is particularly prominent in India, as studies demonstrate a substantial connection between being BRCA-positive and the occurrence of BC in younger women ranging between 20 and 45 years of age [26].

The impact of susceptibility genes like TP53, PTEN, CDH1, ATM, CHEK2, and PALB2 in India is indeed substantial for evaluating cancer risk, screening, therapeutic management, and genetic counseling. However, the thorough detailed information tailored to the Indian population is still emerging. Nevertheless, due to India’s genetic and socioeconomic variability, the incidence, expression, and the relationships between the genotype and phenotype for these genes may differ from those in the Western population [27].

However, with respect to risk assessment and penetrance, studies suggest that the range of mutations in these genes among the Indian population may show distinct disparities when compared to their Western counterparts. For example, a study in the Kashmir valley discovered a high prevalence of TP53 mutations in patients with colon cancer, indicating that it is a major contributor to this population’s elevated risk [28]. Similarly, penetrance or the risk of developing cancer because of a mutation may vary depending on the particular variant, or other genetic or environmental factors. The range of malignancies in families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 mutation) can differ from Western cohorts, with a potentially increased occurrence of particular forms such as sarcomas [29].

This aside, numerous research studies have discovered that the mutation spectrum of cancer susceptibility genes in the Indian population is quite diverse, with notable geographical heterogeneity. In addition, although mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most frequent, other genes are also important contributors. Germline pathogenic mutations have a higher incidence and are frequently associated with early-onset cancer.

According to studies, the comprehensive incidence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations in high-risk Indian breast and ovarian cancer patients is between 20% and 30%, which is greater than that found in Western populations. In some cohorts, BRCA1 mutations are more common than BRCA2, which contrasts with many other Asian ethnicities. This aligns with India’s high prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), and early-onset breast cancer, which are frequently associated with BRCA1 [26,30].

This aside, numerous recurring mutations (as discussed below) have been reported, with diverse frequency across regions.

- c.68_69delAG (185delAG) in BRCA1: This mutation, which is a founder mutation in Ashkenazi Jewish communities is recurrent and seems to have originated independently among the South and West Indian populations.

- c.1961delA in BRCA1: This is one of the most common mutations discovered in current studies.

- c.5074+1G>A in BRCA1: This is most common among West Indian and other populations.

- c.5382insC in BRCA1: This is another frequently occurring pathogenic mutation.

Similarly, numerous studies among the Indian population have reported novel BRCA1/2 mutations not previously cataloged in databases like ClinVar, thus emphasizing the distinct genetic diversity of the Indian subcontinent [26].

Indeed, it will be important to address the issue of specific founder mutations for BC among the Indian population, especially in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, that are associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome. India, with its diversified population and endogamous groupings, has distinct regional founder mutations that influence genetic screening and counseling procedures. Founder mutations are essentially genetic changes that occur or originate in a founding (initial) individual and are inherited by their offspring, gradually becoming increasingly prevalent in particular groups or populations that have stayed isolated owing to geographic or cultural reasons. Moreover, owing to the large and genetically diverse population of India, the distribution of BRCA1/2 mutations varies greatly by location and ethnicity. Additionally, the traditional practice of endogamy in certain communities has led to an increase in the frequency of these founder mutations and heritable conditions.

Some of the crucial insights with regard to the founder mutations in India include the following:

- Shared mutation (185delAG): The BRCA1 185delAG (as mentioned earlier) founder mutation, which is widely linked to the Ashkenazi Jewish population, can also be detected in certain areas of India, especially in the south and west. Indeed, studies indicate that this emerged or originated independently within the South Indian population, instead of originating from a common lineage with Ashkenazi Jews [31].

- Regional heterogeneity: Studies have found a wide range of BRCA1/2 variants among various Indian populations, showing that the types of mutations vary by geographical locations. This indeed highlights the importance of developing demographically specific genetic profiles [26].

- Higher frequency of mutations: Some studies in India have discovered an increased overall frequency of BRCA1/2 mutations among breast and ovarian cancer patients when compared to their Western counterparts [26,32].

Additionally, in India, population-specific founder mutations and other socioeconomic factors have a significant impact on genetic screening strategies and counseling, as discussed below:

- Targeted sequencing–next-generation sequencing (NGS): Instead of expensive, laborious, and lengthy whole gene sequencing, the testing or screening strategies can be highlighted on the most frequent founder mutations that are found in specific regional or ethnic populations. This strategy provides a faster and less expensive screening tool for high-risk people.

- Custom-designed gene panel (personalized genetic test): Genetic testing or screening can be performed with panels tailored to contain common founder mutations unique to the Indian population, along with additional pertinent genes associated with high and moderate risks.

- Overcoming barriers to access: Customized or personalized testing methods can assist in tackling the significant obstacles pertaining to the expense and availability of genetic tests in India.

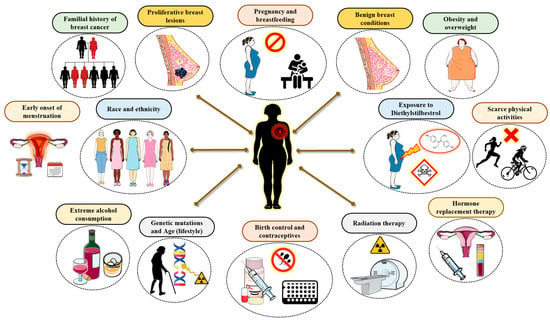

5. Implication of Non-Genetic Risk Factors for Breast Cancer (Figure 5)

5.1. Familial History of Breast Cancer

Although 15% or less women with BC include a familial member who has the disease, women who have close family members who possess the disease are at an immense risk. Especially given this circumstance, having a first-degree relative like mother, sister, or daughter with BC, for instance, nearly increases the risk by twofold. And, on the other hand, having two first-degree relatives with the disease increases the risk threefold [23,24]. Intriguingly, women who have a father or brother who has BC are more likely to develop the disease themselves. Adding to this, and at an individual level, a woman who has cancer in one breast is more likely to develop cancer in the other breast or another part of the same breast [25].

Figure 5.

Implication of non-genetic factors in breast cancer.

Familial history and genetic predisposition are more likely to found among the younger BC patients in India. Typically, the average age at which they are diagnosed is about ten years younger than that of patients in Western countries, thus highlighting the connection between genetic predispositions and the early onset of BC, and consequently assessing the importance of genetic counseling [33]. In fact, 19% of women under forty had a first- or second-degree relative who has cancer. However, the actual frequency of inherited breast cancer in India is probably miscalculated. Numerous BC disease manifestations are reported that are not linked to inherited genes or familial predisposition, indicating that familial history-based screening may overlook a large percentage of mutation carriers [26].

5.2. Proliferative Breast Lesions (PBLs)

Certain proliferating lesions with the absence of atypical hyperplasia has demonstrated to increase a woman’s susceptibility to BC [23,24]. These include fibroadenoma, sclerosing adenosis, ductal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and radial scar. Nonetheless, certain proliferative lesions with atypical hyperplasia in the ducts or lobules of the breast tissue will boost the susceptibility to BC by 4–5 fold which comprises the atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) [34].

However, studies among the Indian population suggest that proliferative breast lesions are substantial contributing factors to BC, which increasingly aggravates young Indian women more than their Western counterparts. In fact, the diagnosis of PBL indicates the necessity for improved screening. Given this severity among the Indian population, the association between PBLs and breast cancer is especially important because of certain traits in the population such as early onset, lifestyle, and hereditary factors. In addition, owing to this higher risk, studies in India recommend that women with proliferative lesions receive more comprehensive follow-up, like clinical breast examinations and mammography screening. In addition, given the greater likelihood of advanced-stage diagnoses in India, detecting women with PBLs is a fundamental strategy for early diagnosis [1,35].

5.3. Lack of Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

To some extent, women who have never had children or who have had their first child at an age later than 30 years old have an increased risk of BC by and large. Having multiple pregnancies and/or conceiving at an early age, on the other hand, lowers the susceptibility to BC [23,24]. However, pregnancy appears to affect different types of BC in a dissimilar manner, and it in fact appears to increase the risk of triple-negative breast cancer. Breastfeeding may perhaps reduce the risk of BC to some extent, especially if it is carried on for 1.5–2 years. One possible interpretation for this conclusion is that breastfeeding decreases a woman’s aggregative number of menstrual cycles over her lifetime.

In India, a lack of pregnancy and breastfeeding, often referred to as nulliparity and never having breastfed, is a substantial and growing risk factor for BC. Although typically Indian women once had timely and numerous pregnancies and breastfed for prolonged durations, these trends are evolving, particularly among the urban, educated population. However, as India undergoes a demographic shift, the prevalence of cancer is rising. In fact, BC has exceeded cervical cancer as the most prevalent malignancy among Indian women predominantly in metropolitan areas. The upsurge in the occurrence of nulliparity and decline of breastfeeding can be attributed as important drivers of this trend, pushing the age of diagnosis to a younger demographic than in Western countries [1].

5.4. Benign Breast Conditions

Women with dense and solid mammograms have an approximately a 1.5- to 2-fold higher susceptibility to BC than women with regular breast density. However, several factors like age, the use of certain medications like menopausal hormone therapy, menopausal status, and pregnancy are found to be involved in defining breast density. This aside, a few non-proliferative lesions may have a minor effect on BC susceptibility. This may comprise fibrosis and/or simple cysts, single papilloma, duct ectasia, mild hyperplasia, adenosis, phyllodes tumor, periductal fibrosis, squamous and apocrine metaplasia, epithelial-related calcifications, and other tumors including lipoma, hamartoma, hemangioma, neurofibroma, adenomyoepithelioma, and mastitis [36].

In the Indian scenario, fibroadenomas and fibrocystic changes are the most frequent benign breast diseases mostly affecting the younger women. Moreover, although the majority of benign conditions pose little to no risk of developing cancer, certain kinds have a marginally increased risk, particularly when combined with other risk factors. Therefore, to differentiate between benign lesions and BC, it is necessary to have an early and precise diagnosis via biopsy, imaging, and clinical testing [37].

5.5. Obesity and Being Overweight

Prior to the onset of menopause, the ovaries produce the majority of the body’s estrogen, while the fat tissue produces only a small amount. Nonetheless, when a woman’s ovaries cease to produce estrogen after menopause, the majority of her estrogen is derived from the fat tissue. Therefore, harboring extra fat tissue after menopause increases estrogen levels which subsequently escalates the susceptibility to BC [23,24]. Additionally, being overweight tends to result in increased insulin levels in the blood. In turn, the elevated levels of insulin are associated with certain types of cancer, including BC. However, the relationship between weight and susceptibility to BC is complex and not yet completely interpreted.

However, given the severity among the Indian population, obesity and being overweight are intricately linked to BC risk, prognosis, and survival, which differs depending on menopausal state and body fat distribution. High body mass index (BMI) is a substantial risk factor for postmenopausal breast cancer, although central obesity is a major risk factor for both premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancers. And, in a broader context, owing to the lifestyle modifications, the growing number of BC cases in India can be somewhat linked to trend towards sedentary lifestyle and dietary changes, leading to a rise in the average body mass index [38].

5.6. Early Onset of Menstruation

Women who begin menstruating early, especially prior to the age of 12, will end up having more menstrual cycles which consequently results in a prolonged lifetime exposure to the hormones like estrogen and progesterone, which, to some extent, increase the susceptibility to BC [23,24]. Likewise, women who reach menopause later, especially after the age of 55, will have more menstrual cycles and a longer lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone, respectively, which again increases their susceptibility to BC.

Early menstruation (menarche) is a major risk factor for BC in the Indian population. This link is mostly attributed to a woman’s prolonged or chronic exposure to hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, which promote breast cell proliferation and raise the risk of cancer. In addition, the landscape of BC in India, characterized by its early onset compared to in Western nations, higher rates of aggressive subtypes like triple-negative BC (TNBC), and substantial discrepancies in detection and treatment, along with lifestyle modifications, contributes its major role [1].

5.7. Race and Ethnicity

On the whole, Caucasian women are to some extent more inclined to develop BC than their African American counterparts, despite the fact that BC is more frequent among the African American women under the of age 45. In addition, they are more prone to die from BC at any age. On the other hand, women from other races, such as those with an Asian, Hispanic, or Native American background, are at a lower risk of developing and dying from BC [23,24].

More specifically, when compared to Western populations, Indian women have a higher prevalence of more aggressive, hormone receptor-negative cancers and are detected at a much younger age. The explanations for these disparities are complex, including genetic predispositions, lifestyle modifications, and socioeconomic background, which contribute to late-stage diagnosis and lower survival rates. Adding to this body of data is a unique clinical presentation with distinct biological characteristics among the Indian BC population. These include early onset, a higher incidence of more invasive tumors (such as TNBC and HER2-positive tumors), and late-stage diagnosis. Such factors make the Indian BC population’s profile more complicated than that of its Western counterparts [1].

5.8. Exposure to Environmental Risk Factors

From the 1940s to the early 1970s, a few pregnant women were prescribed to the estrogen-like drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) which was believed to reduce the incidence of miscarriage [23,24]. These women, to some extent, have an increased risk of BC, and women whose mothers used DES during pregnancy possibly will have a considerably increased risk.

On the other hand, environmental and cultural risk factors in India, together with rising urbanization, confers a substantial impact on BC trends and effects. Indeed, these factors lead to its increased prevalence, with early onset compared to in Western populations, and with diagnostic delays resulting in higher fatality rates [39]. This aside, an emerging risk factor for BC among the Indian population is exposure to pollutants like organochlorine pesticides. This is supported by a case–control study in an Indian population, which found that women with BC had considerably higher serum levels of estrogenic OCPs, including DDT metabolites (DDE) and hexachlorocyclohexane isomers (HCH), compared to healthy control subjects [18].

Similarly, exposure to fine particulate matter like PM2.5, has been linked to an increased risk of breast cancer. According to studies, these small particles can enter the bloodstream and permeate into breast tissue, potentially leading to tumor formation [40]. Likewise, another study conducted among the women from northeast India, found that chewing betel quid was a substantial and independent risk factor for the onset of BC, possibly prompting genetic modifications [41].

Other emerging environmental pollutants like phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are being studied for their potential link to breast cancer. The possible impact of these chemicals that interfere with hormones on the progression of BC is still being investigated [42].

5.9. Scarce Physical Activities

An emerging body of evidence and documentation suggests that routine exercise and physical workouts, particularly in women after menopause, could possibly decrease the risk of breast cancer [23,24]. However, it is unclear as to how physical activity may reduce risk of BC, but it could be because of activity levels influencing body weight, inflammation, hormones, and energy balance.

In the Indian scenario, a lack of physical exercise is a key, alterable factor, leading to the rising incidence of BC, especially in younger urban women. This aside, sedentary lifestyle raises the risk of BC owing to its association with obesity, hormonal disruptions, and inflammation, all of which are proven risk factors that contribute to the illness [1].

5.10. Extreme Alcohol Consumption

Consumption of alcohol is undeniably associated with an increased susceptibility to BC, and this increased risk or susceptibility is proportional to the amount of alcohol consumed. For instance, women who consume two to three drinks per day, have a 20% higher risk of BC than women who do not consume alcohol. And, on the other hand, women who consume only one alcoholic drink per day have a minor increased susceptibility [23,24].

High levels of alcohol intake raise the likelihood of BC among Indian women, reflecting global trends. However, unique lifestyle and genetic factors in the population can lead to different risk factors. In addition, although Indian women have a traditionally lower rate of alcohol consumption than their Western counterparts do, the potential for a negative outcome is growing with the advent of urbanization and “westernized” lifestyles [1].

5.11. Genetic Mutations and Age

An extensive proportion of breast cancers is detected in women with no clear familial history. Furthermore, rather than inherited mutations, these cancers may perhaps be brought about by genetic mutations that appear as a result of the aging process and lifestyle-linked risk factors.

In the Indian population, the effects of genetic mutations and age interact significantly, ensuing in a higher prevalence of BC in younger women, with an increased proportion of aggressive subtypes, and a distinct range of genetic mutations compared to Western populations. More specifically, genetic mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are major contributing factors for the rise in aggressive and early-onset BC cases in India. The prevalence of these mutations, along with diverse mutation patterns, is significantly higher in India than in Western countries [26].

5.12. Birth Control and Contraceptives

Several birth control approaches contain hormones that can increase the risk of BC [23,24]. In addition, women who use oral contraceptives have a higher risk of BC to some extent than women who have never used them. However, the risk appears to return to normal after the regimen is discontinued. To ascertain this, Depo-Provera, administered as an injectable form of progesterone, has been reported to boost the risk of BC; nevertheless, there was no increased risk in women five years after they stopped receiving the shots.

On the other hand, hormonal contraceptives are linked to a minor but considerable increased risk of BC in Indian women, particularly with long-term use. However, this risk should be examined along with other risk factors prevalent in the Indian population, like being of an advanced maternal age at first childbirth and socioeconomic status. Indeed, some Indian studies have indicated a link between the usage of hormonal contraceptives, especially oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) and an increased risk of BC [43,44].

5.13. Chest Radiation Therapy

Women who have had radiation therapy to the chest for another type of cancer at a young age are more likely to develop BC [23,24]. The effect of this factor is ameliorated in case the individual had received radiation as a teen or young adult, when the breasts were still developing. On the other hand, radiation therapy after the age of 40 did not appear to increase susceptibility to BC.

For Indian BC patients, chest radiation therapy carries the same potential risks as it does to other populations, including heart and lung damage, and the development of a secondary malignancy. However, the overall impact and absolute risk of these complications are intensified by underlying factors more prevalent in India, such as increased baseline cardiovascular risk, late-stage diagnosis, restricted access to modern treatment methods, and major financial constraints [45].

5.14. Hormone Replacement Therapy After Menopause

The hormone estrogen (often in combination with progesterone) has been administered to treat menopausal symptoms and thereupon to prevent osteoporosis [23,24]. Most often, combined hormone therapy is required as the usage of estrogen alone can aggravate the risk of uterine cancer. Nevertheless, estrogen can be used alone by women who have had a hysterectomy. This aside, postmenopausal integrated hormone therapy raises the risk of BC, the likelihood of dying from BC, and the chances of detecting cancer only at a more progressive stage subsequently. This increased risk is typically prominent after 2 years of usage. Nonetheless, the increased risk from concomitant or combined HRT is reversible, and it is only relevant to current and recent users. This is because a woman’s BC risk appears to revert to that of the general population after five years of discontinuing HRT. Additionally, the use of bioidentical or “natural” estrogen and/or progesterone is not always safer or more effective and should be regarded as having the same health risks as any other type of HRT. This aside, short-term estrogen usage after menopause does not appear to significantly increase the risk of BC. Yet, long-term treatment (>15 years) has been linked to an increased risk of ovarian and BC, respectively. Therefore, it is up to a woman and her doctor to decide as to whether to use any form of HRT after deliberating the potential risks factors and benefits, and also taking into account other risk factors pertaining to heart disease, BC, and osteoporosis, which occur thereafter.

On the other hand, hormone replacement therapy following menopause offers a complicated risk–benefit scenario for Indian women, which is determined by the type of therapy, the duration it is taken, and the patient’s specific health considerations. Especially for Indian women, who reach menopause at a younger age (46 years) than Caucasian women, the necessity of HRT for symptom relief must be balanced against the long-term risks. An Indian Menopause Society study calls for customized risk assessment, highlighting that the advantages may outweigh the modest absolute risks for healthy women in the first decade after menopause [46].

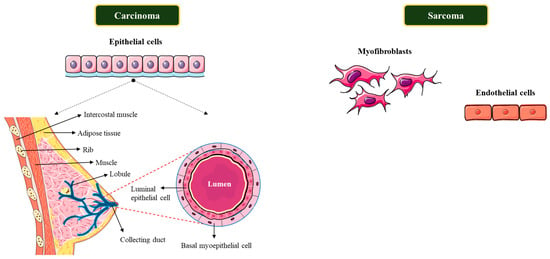

6. Risk Assessment: Breast Cancer Stratification by Way of Pathogenesis, Incidence and Invasiveness

Breast cancers are classified into several types based on where they appear in the breast, for instance in the ducts, lobules, or the tissue in between. The specific cells that are affected define the type of breast cancer. Therefore, they are classified into two distinct types, viz., carcinomas and sarcomas, based on the origin of the cells involved. Principally, carcinomas are breast cancers that develop from the epithelial component of the breast, which includes the cells that outline the lobules and terminal ducts that produce milk. Sarcomas on the other hand, are a much rarer type of breast cancer that develops from the stromal components of the breast, which include myofibroblasts and blood vessel cells (Figure 6). These categories are not always necessary because a single breast tumor can be a mixture of different cell types in some cases [25].

Figure 6.

Breast cancer stratification based on specific cell types.

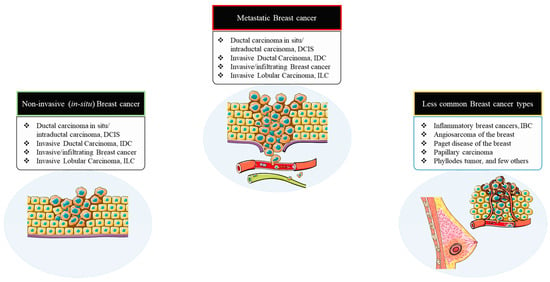

However, the majority of breast cancers are carcinomas. Several different types of breast cancer have been described within the large group of carcinomas depending on their invasiveness corresponding to the primary tumor sites. It is indeed critical to be able to differentiate between the different subtypes since they each have diverse prognoses and treatment implications. Therefore, typically, breast cancers are classified, based on their corresponding pathological features and invasiveness, into three distinct groups: non-invasive (or in situ), invasive, and metastatic breast cancers [25].

6.1. Non-Invasive (In Situ) Breast Cancer

6.1.1. Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (Intraductal Carcinoma; DCIS)

DCIS is a non-invasive or pre-invasive BC that thrives inside from the normal pre-existing ducts, and is one of the most typical types of breast cancer [25]. And, despite the fact that DCIS is not invasive, the in situ carcinomas have a high risk of developing into invasive cancers, and therefore early and appropriate therapeutic regimen is vital in intercepting the patient from developing an invasive cancer.

6.1.2. Invasive/Infiltrating Breast Cancer

Primarily, the cancer cells in invasive breast cancers invade and propagate farther outside of the normal breast lobules and ducts, gradually moving into the adjoining breast stromal tissue [25]. And, when diagnosed with an invasive form of BC, approximately two-thirds of women are 55 or older. In addition, invasive carcinomas have the possibility to progress to other locations of the body, like the lymph nodes or other organs, and form metastases, thus classifying them as metastatic breast cancers [25]. Additionally, the invasive breast cancers are further classified into two types based on the tissue and cell types involved as follows:

6.1.3. Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC)

IDC is the most common type of BC, accounting for approximately 80% of all breast cancers [25]. The IDC group of classification comprises numerous subtypes that include the tubular, medullary, mucinous, papillary, and cribriform carcinomas of the breast [25].

6.1.4. Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC)

ILC is the second most common type of BC, accounting for about 10–15% of all cases [25]. While this subtype of carcinoma can affect women of any age, it is more prevalent in women over the age of 50. Additionally, the invasive lobular carcinoma occur later in life when compared to the invasive ductal carcinoma—for instance, in the early 60s in contrast to the mid-to-late 50s for IDC [25].

Overall, 90–95% of all breast cancers fall into the invasive subcategory. In addition, the invasive ductal carcinoma and the invasive lobular carcinoma have different pathological features. Lobular carcinomas develop as single cells organized individually, in single file, or in sheets, and exhibit distinct molecular and genetic abnormalities. Additionally, both the subtypes distinguish from each other in terms of prognosis and therapeutic regimen (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Breast cancer stratification based on pathogenesis and invasiveness.

6.2. Metastatic Breast Cancer

Metastatic breast cancers are late-stage breast cancers that have spread or progressed to other organs in the body. They are also known as stage IV or advanced breast cancers [25]. Breast cancers can spread to lymph nodes in the armpit and/or distant sites like the lung, liver, bone, and brain. Even after eliminating the prime vital tumor, microscopic tumor cells or micro-metastases may still linger around and prevail in the body, thereby enabling the cancer to recur and spread. Clinically, patients may be diagnosed with metastatic disease (or de novo metastatic BC) at the start of treatment, or they may develop metastases months or years later. The prospective likelihood of BC recurrence and metastasis is not well interpreted or foreseen since it differs from person to person, owing to the tumor’s unique molecular biology and stage at the time of diagnosis. Unfortunately, given the severity, about 30% of women with early-stage BC will develop a metastatic form of the disease (Figure 7) [25].

6.3. Less Common Types of Breast Cancer

Although IDCs and ILCs account for approximately 90–95% of all BC cases, numerous rare or less common types of BC can be detected in the clinical setting [25].

6.3.1. Inflammatory Breast Cancers (IBCs)

IBC is a rare type of invasive BC that accounts for 1–5% of all breast cancers [25]. The inflammatory breast cancers differ from other group of BC in terms of their manifestations, prognosis, and therapeutic regimen. The characteristic symptoms or manifestations of IBC comprises an inflammation-like breast lump or swelling, purple or red skin discoloration, and the pitting or thickening of the breast skin. All of these are possibly triggered by cancer cells blocking the lymph vessels in the skin. However, IBC is not always associated with a breast lump and may not be detected on mammograms. This aside, IBC is more common among younger women and especially the women of African American origin, along with women who are overweight or obese. In addition, it inclines to be more aggressive than other types of BC, growing and metastasizing much more rapidly. It is invariably detected at a locally progressive stage, when the breast cancer cells have spread into the skin. And, in approximately one-third of cases, the IBCs have been detected already metastasized to distant sites of the body, thereby complicating and making treatment more difficult [25].

6.3.2. Angiosarcoma of the Breast

Angiosarcoma is a class of sarcoma that is a very unusual form of cancer that develops from the epithelial cells that line blood or lymph vessels [25]. These angiosarcomas account for 1% of all breast cancer cases and can affect either the breast tissue or the breast skin. A few cases stem as a result of previous radiation therapy in that area. Though uncommon, angiosarcomas grow and spread rapidly and should be treated appropriately.

6.3.3. Paget Disease of the Breast

This uncommon type of BC initiates in the breast ducts, extends to the nipple skin, and then gradually spreads to the areola (the dark circle around the nipple) [25]. Paget disease accounts for 3% of all BC cases and, in addition, the Paget’s cells are visually distinct from normal cells and divide rapidly. Around half of the cells express estrogen and progesterone receptors, and the majority express the HER2 protein. Predominantly, a biopsy of the tissue is usually used to diagnose cancer, and this is occasionally trailed by a mammogram, sonogram, or MRI to verify or validate the diagnosis. It is also worth noting that Paget’s disease of the breast is not medically related to other clinical settings named after Sir James Paget, such as Paget’s disease of the bone.

6.3.4. Papillary Carcinoma

This is another rare form of BC, accounting for less than 3% of all breast cancers [25]. Usually, the cells in papillary carcinoma cancer are typically arranged in finger-like projections. To illustrate further, in certain cases, the cancer cells are relatively minute in dimension and apparently form micropapillary structures. The majority of the papillary carcinomas are invasive, and are treated similarly to IDCs. Nevertheless, the invasive papillary carcinoma typically has a better prognosis than other types of invasive breast cancer. It is worth noting that papillary carcinomas can be identified while still non-invasive. Usually, a non-invasive papillary carcinoma is commonly thought to be a type of DCIS.

6.3.5. Phyllodes Tumor

This is a rare breast tumor that establishes itself in the breast’s stromal cells [25]. The majority of these tumors are benign, but approximately one-quarter are malignant. Phyllodes tumors are most common in women in their 40s, as well as in women with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, who are predisposed to this type of tumor.

6.3.6. Breast Cancers in Men, Children, and Juveniles

The male breast carcinomas can be in situ or invasive, and makes up less than 1% of all cases of breast cancer [25]. They can almost resemble as those observed in women, since the majority of cases are invasive ductal carcinomas with estrogen receptor (ER) expression. Gynecomastia (or breast enlargement) is the most common breast lesion in men, and it can affect either the unilateral or bilateral breasts. Likewise, breast lesions are rare in children and adolescents, but they do happen. These rare cases may comprise both benign and malignant lesions, such as juvenile fibro adenoma and malignant carcinoma. On the other hand, pediatric patients have more possibility to develop lymphoma or alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma that has spread or metastasized to the breast.

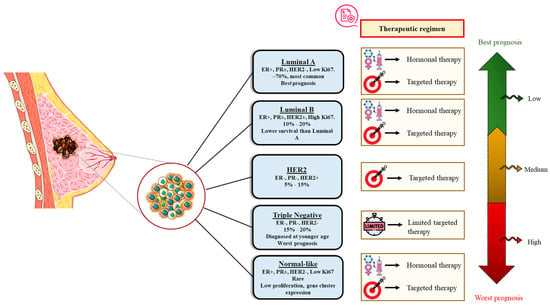

7. Molecular or Intrinsic Subtyping/Classification of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer entails a complex and phenotypically diverse group of diseases and consists of many biological subtypes with specific mechanisms and therapeutic responses. To elucidate further, gene expression studies have determined numerous specific subtypes of BC that vary notably in prognosis along with the therapeutic targets that exist in the cancer cell types [25]. With the advent of gene expression profiling strategies, the list of intrinsic genes that distinguish these subtypes includes several groups of genes linked with the human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) expression, proliferation, the estrogen receptor (ER) expression (the luminal cluster), and a distinct group of genes termed the basal cluster [25]. Accordingly, the BC subtypes are typically classified into five intrinsic or molecular subtypes established on the expression composition or scheme of specific genes using these interpretations (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Molecular or intrinsic subtyping/classification of breast cancer.

7.1. Luminal A Breast Cancer

This subtype is essentially positive for the estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR), and negative for HER2. Luminal A cancers make up roughly 40% of all BCs and are of low grade, growing slowly, and have the best prognosis. The treatment strategy usually includes hormonal therapy [25].

Luminal A breast cancer is defined by high estrogen receptor (ER) expression, indicating its dependence on hormonal signaling. While endocrine dependence is prominent, other involved pathways can lead to resistance if disrupted. This subtype exhibits minimal Ki-67 protein levels, suggesting a slow proliferation rate and a favorable prognosis compared to other subtypes. Key genes linked to luminal epithelial cells, such as GATA3 and FOXA1, function as transcription factors for ER alpha and are significantly expressed, playing a vital role in mammary gland differentiation [47]. In addition, based on integrated genomic analysis, common mutations in the luminal A subtype include the following:

- PIK3CA: Activating mutations are commonly seen in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway.

- GATA3 and MAP3K1: Mutations or alterations in these transcription factors are also frequent.

- TP53: Although not as common as in other subtypes, mutations or alterations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53, are detected in certain luminal A tumors.

7.2. Luminal B Breast Cancer

This subtype accounts for <20% of all BCs and is ER and/or PR positive, HER2 positive or HER2 negative, and has high Ki-67 levels. Luminal B cancers grow somewhat quicker than luminal A cancers and have a slightly worse prognosis [25].

For patients diagnosed with the intrinsic luminal B subtype of breast cancer, the vital molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways are usually distinguished by an elevated proliferative rate along with increased genomic instability when compared to the luminal A subtype. In addition, despite the fact that these subtypes are estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), these tumors frequently use substitute growth pathways, resulting in a more aggressive phenotype and greater rates of endocrine therapy resistance. Similarly, these subtypes have a higher level of somatic mutations, gene copy number alterations (CNAs), and DNA methylation abnormalities than the luminal A subtype. Moreover, these extensive genetic alterations lead to an increased tumor grade with poor prognosis. Likewise, the tumor suppressor gene TP53 is more commonly altered in luminal B malignancies. In addition, deactivating this gene impairs cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair, resulting in unregulated cell division with increased genomic instability [48]. This aside, luminal tumors frequently harbor somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene, which encodes a PI3K subunit. However, the frequency is decreased in luminal B compared to luminal A, indicating that additional factors influence its activation. On the other hand, the deletion or lack of expression of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, which serves as a negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, may lead to an increased pathway activity. Similarly, the Akt and mTOR proteins are activated downstream of PI3K, triggering cell growth and proliferation, while also increasing resistance to endocrine therapy [49].

7.3. HER2-Enriched Breast Cancer

This subtype accounts for 10–15% of all BCs and is defined by the lack of ER and PR expression, high HER2 and proliferation gene cluster expression, and sparse expression of the luminal and basal clusters [25]. This aside, the HER2-supplemented cancers thrive more rapidly than luminal cancers and have a poor prognosis in general. Nevertheless, they can be effectively managed with HER2-targeted therapies like Tykerb (or lapatinib), Herceptin (or trastuzumab), Kadcyla (or T-DM1 or ado-trastuzumab emtansine), and Perjeta (or pertuzumab). Additionaaly, it should be noted that the HER2-supplemented subtype does not imply clinically HER2-positive BC. Despite the fact that approximately 50% of clinical HER2-positive BCs are HER2 supplemented, the residual 50% can be of any molecular subtype but are predominantly HER2-positive luminal subtypes. Yet, approximately 30% of HER2-enriched tumors are clinically HER2-negative [25].

The main molecular mechanism underlying the HER2-enriched (HER2-E) intrinsic subtype of BC is the overexpression or amplification of the ERBB2 gene, which encodes the HER2 receptor. As a result, there is an overactivation of the HER2 signaling pathway, which triggers a number of downstream cascade of events that regulate uncontrolled cell proliferation, growth, and survival. The primary mechanism driving HER2-E BC is the occurrence of too many copies of the ERBB2 gene, which results in a surplus of the HER2 protein on the cell surface [50]. The dimerization of HER2 receptors stimulates a number of critical downstream signaling pathways including the following:

- PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: This signaling pathway is one of the most commonly activated downstream of HER2 and is an important regulator of cell survival, growth, metabolism, and proliferation. Mutations in the PIK3CA gene, which encodes the p110α subunit of PI3K, along with the loss of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, are prevalent in HER2+ BC, leading to constitutive PI3K/Akt activation and treatment resistance.

- MAPK/ERK pathway: The MAPK signaling pathway is yet another important modulator of HER2 signaling, which stimulates cell proliferation. Certain metastatic HER2-positive BCs exhibit genetic modifications that trigger the MAPK pathway, including the deletion of NF1. This can lead to a “pathway switch”, rendering tumors resistant to Akt obstruction, yet more reliant on and susceptible to MEK/ERK inhibition.

- Likewise, other related signaling pathways like HIF-1, Wnt/β-catenin, and STAT signaling pathways are also known to be activated in some HER2-enriched tumors, thus contributing to the resistance of anti-HER2 therapies.

7.4. Triple-Negative/Basal-like Breast Cancer (TNBC)

Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancer are ER, PR, and HER2-negative and account for approximately 20% of all BCs [25]. TNBC is more prevalent among women with BRCA1 gene mutations, women under the age of 40, and African American women. It is a high-grade BC since it acts more destructively than other types of BC. TNBC is most commonly diagnosed with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, though an uncommon histologic subtype, medullary carcinoma, is also triple negative. Additionally, TNBC’s non-surgical treatment/management has been restricted to usual chemotherapy, in contrast to other breast cancer subtypes, which have an arsenal of targeted regimens such as ER antagonists and HER2 monoclonal antibodies, until the validation of the PARP inhibitor Olaparib for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, who are prone to develop TNBC [25].

Likewise, TNBC is more invasive and has a greater rate of early recurrence than other forms of BC. The prognosis is often very bad, and most patients relapse five years following surgery. Not to mention, TNBC is resistant to both targeted and endocrine therapies since ER, PR, and HER2 are negatively expressed. In addition, TNBC can only be treated with a few, often ineffective therapies, and thus there is a pressing, urgent need for novel therapies [51,52].

Additionally, targeting the mechanisms that underpin genomic instability may be required for such cancers, in which chromosomal instability is a driving factor. It is still unclear how significant many genetic dependencies and anomalies are across the various forms of breast cancer. In order to unravel the essential molecular pathways and interconnected nodes, a thorough functional screening such as CRISPR-Cas9 technology coupled with deeper analyses and data integration would be needed [53,54,55].

Furthermore, TNBC is a diverse and aggressive BC subtype, characterized by unique molecular mechanisms and signaling cascades. Certain genetic mutations and dysregulated pathways define this subtype, influencing its proliferation, metastasis, and prognosis [56]. The landscape of TNBC is intricate and can be categorized into molecular subtypes, each presenting distinct treatment-responsive deficiencies and featuring numerous significant pathways discussed below, which play a role among them.

- PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: The PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) signaling pathway is among the most frequently modified and excessively activated in TNBC. This pathway regulates cell proliferation, survival, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Mutations in the PIK3CA gene or the deletion of the tumor suppressor PTEN are common causes of hyperactivation. This pathway may also play a role in contributing to chemoresistance and relapse [57].

- DNA damage response (DDR) pathways: A considerable proportion of TNBC tumors are distinguished by deficiencies in DNA repair processes, a feature known as “BRCAness”, due to its similarities to tumors with inherited BRCA1/2 mutations. This aside, mutations in BRCA1 are especially known to be linked to the basal-like type of TNBC.

- Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway: The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is essential for embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis, but it is abnormally active in certain malignancies, including TNBC. In TNBC, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is frequently overactivated because of the high levels of Wnt receptors such Frizzled (FZD7) and the Wnt co-receptor LRP6. As a result, β-catenin is stabilized and subsequently moves into the nucleus.

7.5. Normal-like Breast Cancer

This subtype resembles to the luminal A disease. They are ER and/or PR positive, HER2 negative, and have low levels of protein Ki-67 [25]. While normal-like breast cancer has a noble prognosis, it is still somewhat worse than luminal breast cancer.

Due to the inherent cellular and molecular diversity of breast cancers (BCs), simultaneous investigation of multiple genetic alterations is essential [27]. Advances in next-generation genomics and transcriptomics have facilitated this, leading to the identification of numerous BC subtypes with distinct prognoses and therapeutic targets [58]. These intrinsic subtypes naturally divide into two main groups based on hormone receptor gene expression, reflecting the clinically understood biological differences between ER-positive and ER-negative cancers, which originate from different progenitor cells.

To sum up, the histopathological and molecular/intrinsic classification of BC are two diverse but complementary approaches used in understanding and categorizing BC. Indeed, each provides a distinctive perspective on the nature of the disease’s manifestation. While histopathology concentrates on the microscopic features of cancer cells and tissue architecture, molecular subtyping focuses on the patterns of gene expression to categorize tumors based on their biological functions. Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), mucinous carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, papillary carcinoma, and others are among the most prevalent histological forms. In addition, HER2-enriched, basal-like/triple-negative, luminal A, and luminal B are the most well-known molecular subtypes. In addition, molecular subtyping counts on the condition of important biomarkers like estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), as well as proliferation markers like Ki-67.

To elaborate, histopathological classification (e.g., ILC, IDC) examines cancer cells’ microscopic organization and features, while molecular subtyping analyzes attributes like gene expression signatures to categorize tumors. Both methods have prognostic significance: specific histological subtypes like tubular carcinoma indicate favorable prognosis, while others like metaplastic cancer suggest a negative one. Similarly, the likelihood of recurrence and response to treatment vary by molecular subtype; for example, luminal A tumors generally have a better prognosis than luminal B tumors [1].

In addition, although prognostic information is provided by both the classifications, molecular subtyping might enable a more accurate evaluation of risk and possible outcomes. Similarly, while there is not always a one-to-one correlation, some histological types are more likely to be linked to particular molecular subtypes. For example, luminal A is a common presentation of invasive lobular cancer. Essentially, histopathology lays the groundwork for comprehending the visual aspects of BC, whereas molecular subtyping sheds light on the disease’s underlying biology and behavior, which in turn influences prognosis and therapeutic approaches.

8. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Molecular Subtypes in the Indian Setting

However, in the Indian context, there is a well-established correlation between the molecular subtypes of BC, particularly those defined by immunohistochemistry (IHC), their histological attributes, and their respective clinical outcomes. In addition, although there is considerable variation across studies, recent research suggests that luminal A is the most prevalent subtype, followed by triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and luminal B, both of which are observed at high rates in India [59,60,61]. Luminal A, which is frequently regarded as the most prevalent subtype among Western populations, may be less common in certain Indian studies, or differences in Ki-67 evaluation may have an impact on its diagnosis. In addition, corresponding to the global trends, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is the most prevalent histological form of BC among all molecular subtypes in India. Moreover, while lower histological grades (Grade I) are often linked to luminal A cancers, higher histological grades (Grade III) are frequently associated with TNBC, HER2-enriched, and luminal B subtypes.

Moreover, in terms of lymphovascular invasion (LVI), some Indian studies suggest a strong association between molecular subtypes and LVI. While the highest prevalence of LVI has been observed in various subtypes depending on the study, it is generally considered higher in aggressive subtypes, such as HER2-positive BC and TNBC compared to luminal A tumors [59,60,61]. However, some studies from India demonstrate a higher rate of lymph node positivity in TNBC, in comparison to some other regions [58]. Additionally, these studies also suggest that HER2 and TNBC-enriched subtypes might present with bigger tumors than that of luminal A.

Given the current oncological landscape of India, molecular profiling is becoming more popular, since it can help guide personalized therapy choices, especially when combined with techniques like next-generation sequencing (NGS). Although promising, a number of limitations in local data solutions and access to the gene expression assays hinder its extensive and fair implementation [21].

In terms of its positive impact on treatment decisions, it undeniably helps gain a deeper insight into tumor heterogeneity. By identifying each tumor’s distinct genetic composition, molecular profiling goes beyond conventional classification systems and enables a more specialized and prospective therapeutic regime. It advances personalized and precision medicine by diagnosing precise molecular subtypes and predicting treatment outcomes [62]. Oncotype DX and similar tests can predict recurrence risk, allowing clinicians to identify individuals who can safely evade chemotherapy, saving unnecessary toxicity exposure and expenses, thus refining prognosis and abating overtreatment [15]. Similarly, gene expression profiling (GEP) aids in the identification of appropriate chemotherapy regimens, predicting therapeutic response, and tracking disease progression [15]. Indeed, clinical studies or trials aimed at specific genetic profiles can accelerate the discovery and regulatory approval of novel therapies.

In addition, given the inadequacy of local data infrastructure and gene expression assay availability, current genomic classifiers, such as Oncotype DX and MammaPrint, are often exorbitant for most Indian patients. The fact that most genomic classifiers were established with data predominantly from Western populations raises questions about their applicability and efficacy within the heterogeneous Indian population [63]. Indeed, there is a significant scarcity of comprehensive and thorough research investigating the molecular heterogeneity of BC subtypes among the Indian population. In fact, ongoing RNA and DNA profiling studies on Indian patients are demonstrating distinct genetic and expression patterns when compared to data from Western populations [64]. In addition, due to India’s insufficient government investment in healthcare and inadequate coverage plans, a substantial amount of healthcare spending comes directly from the patients/individuals, thus making expensive examinations like GEP unaffordable to many.

Furthermore, limited access to diagnostic and treatment technologies, especially in rural areas, insufficient resources and equipment, and a scarcity of experienced specialists in molecular testing make access more challenging. Discrepancies in molecular technologies like microarray, sequencing, RNA extraction, and reverse transcription procedures can result in variations. Therefore, standardized operating procedures or guidelines across the testing centers are essential for consistency [65]. Therefore, overcoming these hurdles, and leveraging focused research, with improved governmental measures, prioritizing healthcare equity initiatives, are critical to realize the prospects of molecular profiling for breast cancer patients in India.

9. Clinical Phasing/Staging and Characteristic Survival Percentage in BC Cases

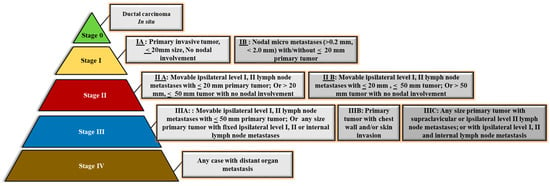

When a patient is detected with breast cancer, routine assessments are implemented to define the stage of the disease, which influences the treatment they receive. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the International Union for Cancer Control’s (UICC) Tumor, Node, and Metastasis (TNM) breast cancer staging system, the clinical staging of breast cancer is alike across breast cancer subtypes: Stage 0, Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, and Stage IV, as detailed in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Clinical phasing/staging and characteristic survival percentage in BC cases.

10. Treatment Options for Breast Cancer

Treatment options for BC are often determined by numerous factors, such as the specific type, progression of the disease, the patient’s genetic composition, and their clinical status. Treatment may consist of a single approach or be used in conjunction with various therapies, such as surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies. While some treatment strategies focus on the specific area surrounding the tumor, others are systemic, affecting the entire body with cancer-fighting agents. Table 1 below outlines and explains the mechanisms of action for various cancer therapies and their application in the Indian context, taking into account factors like population demographics, disease burden, and healthcare infrastructure.

In India, the use of breast cancer therapies is increasing, despite challenges like resource disparities, high costs, and a need for better infrastructure. These obstacles have spurred new research efforts aimed at producing more cost-effective and holistic therapeutic options, as well as gaining a deeper insight into cancer with the resident population. The most prominent challenges and the ongoing research for each of these BC treatment options in the Indian context are discussed below.

10.1. Surgical Therapy

A late-stage diagnosis presents with advanced malignancy, making surgical treatment more challenging and requiring more resources. This is further complicated by a lack of specialized oncologists along with the disproportionate distribution of cancer facilities or centers, which results in many procedures being conducted in less than ideal conditions. Moreover, in terms of research investigations, Indian guidelines are progressively promoting a multidisciplinary team (MDT) strategy for complicated surgeries, particularly for advanced tumors. Studies are also being carried out to perceive the high out-of-pocket expenditure associated with challenging cancer surgeries, including at government institutions [66].

10.2. Radiation Therapy