Abstract

In Norway, organized cervical cancer screening was cytology-based until 2023, and women screened in 2013–2015 were largely unvaccinated. We conducted a retrospective, population-based cohort study to assess whether co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay improves detection of high-grade cervical lesions in women < 40 years. Among 11,395 women screened in Northern Norway and followed for 8–10 years, 2807 formed a co-testing cohort (ThinPrep cytology plus PreTect SEE; HPV16/18/45) and 8588 formed a cytology-only cohort. The endpoint was histologically confirmed CIN2+. Sensitivity for CIN2+ was 63.7% with cytology alone and 71.0% with co-testing (absolute +7.3 percentage points; p = 0.034). In the co-testing cohort, HPV mRNA was detected in 10.2% of women, of whom 46.0% developed CIN2+, while CIN2+ risk in HPV mRNA-negative women was 5.2%. Co-testing produced wide risk gradients: CIN2+ risk was 58.3% in double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+) and 3.3% in double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology), with no cervical cancers observed in the latter group. In this cytology-based, largely unvaccinated setting, co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay improved detection performance and long-term risk stratification in women < 40 years, supporting its use as a quality-assurance and triage tool within organized screening programs.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer arises almost exclusively from persistent HPV infection and is rare before age 30; age-specific incidence remains much lower below age 40 than at older ages in many high-income settings [1,2,3]. Most HPV infections in younger women are transient [4,5]. Screening strategies must therefore balance early detection of clinically significant disease against harms from overtesting and overtreatment (e.g., unnecessary colposcopy and excisional procedures), as emphasized in contemporary guidelines [6,7,8]. Cytology has long been the basis of screening in younger women, but can miss HPV-driven precancer [9,10]. Primary HPV DNA testing improves sensitivity, yet its limited specificity in younger women—where transient infections are common—may increase follow-up and anxiety without necessarily improving outcomes [10,11].

HPV mRNA assays detect expression of the E6/E7 oncogenes that drive malignant transformation, providing a more proximate marker of clinically relevant infection than viral DNA alone [11,12,13]. Targeted assays for HPV16, HPV18 and HPV45 are of particular interest in women under 40 because these genotypes are among the most frequently detected types in cervical cancer in this age group and are overrepresented in invasive cancer compared with high-grade precursor lesions [14,15,16,17].

In Norway, organized cervical screening was cytology-based with a three-year interval until the national roll-out of primary HPV testing in 2023, and women screened in 2013–2015 were largely unvaccinated [10,18]. The HPV vaccine was introduced for 12-year-old girls in 2009, and a national catch-up program was not implemented until 2016 [18,19]. Many high-income countries introduced HPV vaccination in school-based programs for preadolescent girls between 2007 and 2012, often with temporary catch-up campaigns for older adolescents and young adults, and several have later expanded vaccination to include boys [20]. In parallel, countries such as Australia, the UK, Italy and the Nordic countries have progressively transitioned from cytology-based screening to primary HPV testing, typically with extended screening intervals and age-targeted algorithms [21,22]. Within this historical and international context, Norway provides a distinct setting in which to evaluate the added value of HPV mRNA co-testing in young women.

Here, we evaluate whether co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay (PreTect SEE; HPV16/18/45) and liquid-based cytology, compared with cytology alone, improves detection performance and risk stratification for CIN2+ in women under 40 in Northern Norway, with 8–10 years of follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective, population-based cohort study within the organized cervical cancer screening program in Northern Norway, following STROBE recommendations for reporting cohort studies. The objective was to compare co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay (PreTect SEE; HPV16/18/45) plus liquid-based cytology (LBC; ThinPrep) versus cytology alone for detection and risk stratification of histologically confirmed CIN2+ in women < 40 years. All screening samples were collected between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2015, and women were passively followed for incident CIN2+ and cervical cancer through 31 December 2023 via linkage to regional and national pathology and screening registers. The study was conducted at the Department of Clinical Pathology, University Hospital of North Norway (UNN), which serves as the sole pathology provider for Troms and Finnmark counties.

2.2. Study Population

The source population comprised all cervical cytology samples received by the Department of Clinical Pathology, UNN, from residents of Troms and Finnmark counties during the inclusion period. From 79,140 cytology samples originating from 67,263 women, we identified 11,395 women aged < 40 years who met eligibility criteria and contributed one index screening episode each. These women formed two calendar-defined cohorts: (i) co-testing cohort (intervention): women screened during predefined periods in 2013–2014 in whom the same screening sample underwent LBC and HPV mRNA testing (n = 2807); and (ii) cytology-only cohort (control): women screened in 2015 with LBC alone and no concurrent HPV testing (n = 8588).

Inclusion was restricted to routine or opportunistic screening encounters with a satisfactory cytology specimen according to program criteria. Exclusion criteria were unsatisfactory or indeterminate cytology; insufficient residual LBC material for mRNA testing in the co-testing cohort; invalid intrinsic sample control (ISC) on the mRNA assay; missing personal identifiers precluding deterministic record linkage; and non-residency in the catchment area at index screening. Women with invalid or unsatisfactory samples were recommended a repeat test according to national guidelines, and the first subsequent valid sample during the inclusion period was used as the index screening test. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants from the source population to the final analytical cohorts, including numbers excluded at each step. Study size was determined by the total number of eligible women in the catchment area during 2013–2015; no a priori sample size calculation was performed.

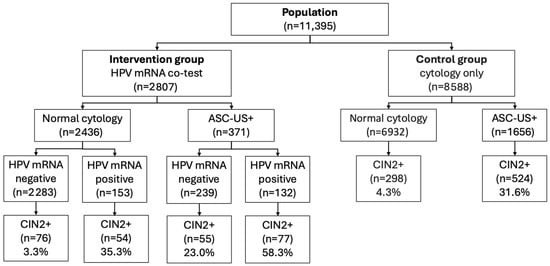

Figure 1.

Flow of included women in the intervention group (HPV mRNA co-test, 2013–2014) and control group (cytology only, 2015). The figure shows the number of women with normal cytology and ASC-US+ at baseline, stratified by HPV mRNA result (negative/positive) and subsequent diagnosis of CIN2+ during follow-up. Abbreviations: ASC-US+, ASC-US or more severe cytological abnormalities according to the Bethesda classification (ASC-US, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, AIS, cytological cervical cancer); CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus; mRNA, messenger RNA.

Individual HPV vaccination status was not recorded in the screening database and was therefore unavailable for analysis. The school-based HPV vaccination program in Norway targeted 12-year-old girls from 2009, and a national catch-up program for older cohorts was not introduced until 2016–2019. Thus, women aged < 40 years who attended screening in 2013–2015 were born before the vaccine-eligible cohorts and are expected to be virtually unvaccinated; opportunistic HPV vaccination outside the childhood program was rare because the vaccine was self-paid and not actively promoted in this age group. No exclusions were made on the basis of previous HPV infection, abnormal cytology, or histologically confirmed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; women with such histories were eligible for inclusion provided the index cytology specimen fulfilled the technical criteria above.

2.3. Cytology

Cervical samples were collected in ThinPrep PreservCyt solution (ThinPrep Pap Test, Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) according to national program practice by general practitioners and gynecologists, transported to UNN, processed on the ThinPrep platform, and reported by cytotechnologists and pathologists using the 2014 Bethesda System (NILM, ASC-US, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, AIS, carcinoma). All cytology was read at a single laboratory (UNN) using stable protocols throughout the study period. Quality control followed departmental standard operating procedures, including random rescreening of negative smears and targeted review of selected categories (e.g., ASC-US, HSIL, glandular abnormalities), to minimize misclassification and ensure consistency over time.

2.4. HPV mRNA Testing

Residual LBC material from the same screening vial was tested with PreTect SEE (PreTect AS, Klokkarstua, Norway), a qualitative, type-specific E6/E7 mRNA assay for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 based on real-time NASBA (isothermal amplification at 41 °C) with molecular beacon probes. Total nucleic acids were isolated from 1 mL residual PreservCyt using the manufacturer’s protocol [23]. Each analytical run included positive (synthetic oligonucleotides) and negative (RNase-free water) controls and an ISC targeting a human housekeeping transcript to verify RNA integrity and absence of inhibition. According to the quality-assurance workflow, cytology was generally reported before HPV testing, and cytologists were blinded to mRNA results at primary screening; in a minor subset, mRNA results could have been available at final sign-out, as discussed under bias minimization (Section 2.7) [11,17].

2.5. Clinical Management and Follow-Up

Clinical management followed national program guidance in force during the study periods, within the framework of the organized Norwegian cervical cancer screening program (3-year interval, ages 25–69 years). Women with abnormal cytology were managed according to guideline algorithms (repeat testing, reflex HPV testing and/or referral to colposcopy/biopsy as indicated), and the same regional gynecology services served both cohorts.

In the cytology-only cohort, management was based on cytology and reflex HPV DNA testing. Smears with ASC-US/LSIL were triaged by HPV DNA testing (Cobas 4800; Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, USA) with partial HPV16/18 genotyping; women who were HPV16/18-positive or had persistent HPV positivity and/or cytology ≥ASC-US were referred to colposcopy with biopsy, whereas those with HPV-negative low-grade cytology were followed with repeat cytology and/or HPV testing at 6–12 months according to contemporaneous guidelines.

In the co-testing cohort, HPV mRNA results were incorporated within a predefined quality-assurance framework. Women with HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology (NILM) were generally recalled for repeat co-testing at 12 months, and those with persistent HPV mRNA positivity and/or cytology ≥ASC-US were referred to colposcopy with biopsy. In women with persistent HPV mRNA positivity and negative or ≤CIN1 histology after two biopsy episodes, a third biopsy or diagnostic LEEP could be considered at the gynecologist’s discretion to exclude occult CIN2+. Apart from the additional information provided by the HPV mRNA test in the co-testing cohort, clinical pathways and access to colposcopy were similar in both cohorts.

Outcomes were ascertained through linkage to pathology records at UNN and affiliated laboratories (cervical cytology, HPV tests, cervical biopsies, LEEP specimens and hysterectomy samples) and by review of colposcopy/biopsy reports through 31 December 2023.

2.6. Outcomes and Definitions

Index tests comprised the cytology category at baseline and the HPV mRNA result (positive for any of 16/18/45 or negative) in the co-testing cohort. The primary outcome was histologically confirmed CIN2+ (CIN2, CIN3/AIS or invasive cervical carcinoma) occurring after the index screening test. Women were classified as having CIN2+ if at least one cervical biopsy, LEEP specimen or hysterectomy specimen showed CIN2+. Women without any CIN2+ diagnosis during follow-up were classified as no CIN2+. Time at risk was measured from the date of the index screening test to the earliest of CIN2+ diagnosis, hysterectomy, emigration/out-migration from the catchment area, death, or end of follow-up (31 December 2023).

2.7. Bias Minimization and Handling of Missing Data

Verification of disease status was based on routine care within the organized Norwegian screening program. All women were passively followed for 8–10 years through the laboratory information system SymPathy (Tieto, Helsinki, Finland), which captures all cervical cytology, HPV tests, cervical biopsies, LEEP specimens and hysterectomy samples from Troms and Finnmark. In addition to the national call–recall system, local reminder routines and, when indicated, HPV self-sampling were used to reduce loss to follow-up among women who did not attend recommended control visits. For women who moved to other regions of Norway, follow-up information was supplemented by linkage to national screening and pathology registers, ensuring near-complete ascertainment of CIN2+ within Norway.

To address potential work-up (verification) bias, the primary analyses included all women irrespective of whether they underwent biopsy, and histology was considered “negative” unless CIN2+ was subsequently diagnosed during follow-up. Because biopsy referral depended primarily on cytology and guideline-based algorithms applied similarly in both cohorts, differential verification by HPV mRNA status was minimized. Sensitivity analyses were performed restricting to women with ≥1 follow-up test and stratifying by baseline cytology (NILM vs. abnormal) to assess the robustness of the findings.

Records with invalid HPV mRNA ISC or unsatisfactory cytology were excluded a priori and replaced by the first subsequent satisfactory sample within the inclusion window when available. Individual-level covariates such as HPV vaccination status, smoking and parity were not available in the screening database and were therefore not included in multivariable models; no statistical imputation of missing covariate data was undertaken.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized by cohort, with the woman as the unit of analysis (first eligible screening within the inclusion window). Diagnostic performance for CIN2+ was calculated with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI): sensitivity = TP/(TP + FN); specificity = TN/(TN + FP); positive predictive value (PPV) = TP/(TP + FP); negative predictive value (NPV) = TN/(TN + FN). For co-testing, we evaluated cytology alone, HPV mRNA alone (within the co-testing cohort), and an either-positive co-test strategy. Group comparisons used χ2 tests (Fisher’s exact test where expected counts < 5). Absolute differences in proportions (including the difference in sensitivity) were reported with 95% CIs using the Newcombe score method. Two-sided p < 0.05 defined statistical significance. Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics v29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with selected endpoints replicated in R v4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

2.9. Ethics and Data Protection

This work was conducted as a quality-assurance project at UNN using leftover LBC material to reduce the risk of cancer after potential false-negative cytology. The protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, REC Nord (2013/497/REK Nord), as quality assurance with waiver of informed consent, and by the UNN Data Protection Officer (2016/2873). All analyses used anonymized datasets. De-identified analysis files and code will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to institutional and legal data-protection requirements.

3. Results

3.1. Final Study Population

After exclusions, 11,395 women < 40 years were included: in total, 2807 underwent co-testing with ThinPrep cytology and a 3-type HPV mRNA assay (PreTect SEE), and 8588 had cytology alone (Figure 1).

3.2. Overall CIN2+ During Follow-Up

CIN2+ was diagnosed in 1084/11,395 women (9.5%) overall: 262/2807 (9.3%) in the co-testing cohort and 822/8588 (9.6%) in the cytology-only cohort (p = 0.737). Among women with normal cytology at baseline, CIN2+ occurred in 130/2436 (5.3%) in the co-testing cohort versus 298/6932 (4.3%) in the cytology-only cohort (p = 0.040). Among women with ASC-US+ cytology at baseline (ASC-US or more severe cytological abnormalities according to the Bethesda classification), the corresponding proportions were 132/371 (35.6%) and 524/1656 (31.6%), respectively (p = 0.16).

3.3. HPV mRNA Status and CIN2+ Risk (Co-Testing Cohort)

In the co-testing cohort, HPV mRNA was positive in 10.2% (285/2807) of women. CIN2+ was detected in 131/285 (46.0%) HPV mRNA-positive women and in 131/2522 (5.2%) HPV mRNA-negative women (p < 0.0001). Double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology) had a CIN2+ risk of 3.3% (76/2283), whereas double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+) had the highest risk at 58.3% (77/132) (p < 0.0001). Among women with discordant results, CIN2+ risk was 35.3% (54/153) for HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology and 23.0% (55/239) for HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-US+ (p = 0.011).

3.4. Diagnostic Performance of HPV mRNA (Co-Testing Cohort)

Using histologically verified CIN2+ as the endpoint, the 3-type HPV mRNA test in the co-testing cohort had a sensitivity of 50.0% (131/262), specificity of 93.9% (2391/2545), PPV of 46.0% (131/285), and NPV of 94.8% (2391/2522). The cross-tabulation of HPV mRNA results versus CIN2+ status is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

HPV mRNA test result and detection of CIN2+ in the co-testing cohort.

3.5. Genotype-Specific Findings (Co-Testing Cohort)

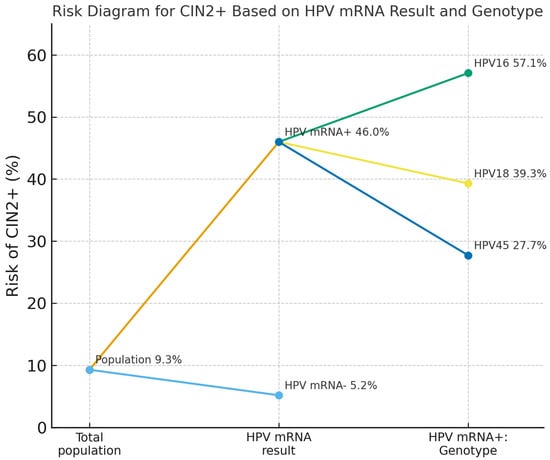

In the co-testing cohort, overall HPV16/18/45 mRNA positivity was 10.2% (285/2807), comprising HPV16 in 6.3% (177/2807), HPV18 in 3.2% (89/2807) and HPV45 in 3.3% (94/2807), with some women harboring multiple genotypes. The PPV for CIN2+ was highest for HPV16 (57.1%), and lower for HPV18 (39.3%) and HPV45 (27.7%). The genotype-stratified CIN2+ risks are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of CIN2+ in the co-testing cohort according to overall HPV mRNA status and genotype among HPV mRNA-positive women. The diagram shows the risk in the total screening population (9.3%), then stratified by HPV mRNA status alone (46.0% for HPV mRNA-positive vs. 5.2% for HPV mRNA-negative women), and further by genotype among HPV mRNA-positive women: 57.1% for HPV16, 39.3% for HPV18, and 27.7% for HPV45. Abbreviations: CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus; mRNA, messenger RNA.

3.6. Cytology Performance (Co-Testing Cohort)

At baseline, ASC-US+ cytology was observed in 13.2% (371/2807) of women and yielded a sensitivity of 50.4%, specificity of 90.6%, PPV of 35.6% and NPV of 94.7% for CIN2+. High-grade cytology (ASC-H+) occurred in 3.6% (102/2807) and showed lower sensitivity at 29.8% but higher specificity (94.1%), with a PPV of 76.5% and NPV of 93.2%.

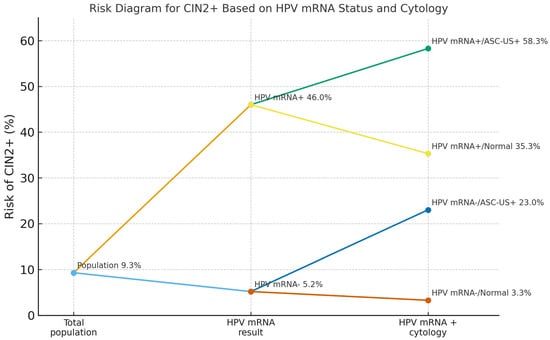

3.7. Combined Cytology–HPV mRNA Strata (Co-Testing Cohort)

When cytology and HPV mRNA results were combined, CIN2+ risk varied markedly across strata. In the low-grade framework, CIN2+ risk was 3.3% (76/2283) in double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology), 23.0% (55/239) in HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-US+, 35.3% (54/153) in HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology, and 58.3% (77/132) in double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+; Figure 3). In the high-grade framework, CIN2+ risk was 4.2% (105/2,481) in HPV mRNA-negative women with NILM/LSIL, 63.4% (26/41) in HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-H+, 35.3% (79/224) in HPV mRNA-positive/NILM–LSIL and 85.2% (52/61) in double-positive women with HPV mRNA-positive/ASC-H+ cytology (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk of CIN2+ in the co-testing cohort according to HPV mRNA status and cytology. The diagram shows the overall risk in the total screening population (9.3%), then stratified by HPV mRNA status alone (46.0% for HPV mRNA-positive vs. 5.2% for HPV mRNA-negative women), and further by cytology grade. Among HPV mRNA-positive women, CIN2+ risk was 58.3% with ASC-US+ cytology and 35.3% with normal cytology. Among HPV mRNA-negative women, the corresponding risks were 23.0% and 3.3%, respectively. Abbreviations: CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus; mRNA, messenger RNA; ASC-US+, ASC-US or more severe cytological abnormalities according to the Bethesda classification (ASC-US, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, AIS, cytological cervical cancer).

3.8. Comparative Detection Performance: Co-Testing vs. Cytology Alone

In the cytology-only cohort, sensitivity for detecting CIN2+ was 63.7% (524/822). In the co-testing cohort, defining a positive screen as either HPV mRNA-positive or ASC-US+ cytology, sensitivity increased to 71.0% (186/262), corresponding to an absolute gain of 7.3 percentage points (95% CI: 0.8–13.6), a relative increase of 11.4% and p = 0.034.

3.9. Cervical Cancer Outcomes

Cervical cancer was diagnosed in 0.1% of women in both cohorts (12/8588 in the cytology-only cohort and 4/2807 in the co-testing cohort). No cancers occurred among double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology). In the co-testing cohort, cancer risks by baseline stratum were 0.4% (1/239) for HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-US+, 0.7% (1/153) for HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology and 1.5% (2/132) for HPV mRNA-positive/ASC-US+. Among women with high-grade cytology, cancer occurred in 2.4% (1/41) of those who were HPV mRNA-negative and 1.6% (1/61) of those who were HPV mRNA-positive (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between HPV mRNA test, low-grade cytology and cervical cancer (CxCa) in the co-testing cohort.

3.10. Age-Specific Distribution of HPV mRNA Genotype Positivity in the Co-Testing Cohort

In the co-testing cohort, overall HPV mRNA positivity was 10.2% (285/2807), with a clear decline by age: 18.4% in women < 25 years, 9.6% at 25–29 years, 5.0% at 30–34 years and 2.9% at 35–39 years. HPV16 was the most frequent genotype in all age groups, detected in 12.1%, 6.2%, 2.3% and 1.2% of women, respectively. The corresponding prevalences for HPV18 were 6.8%, 1.7%, 1.5% and 0.9%, and for HPV45 were 6.9%, 2.0%, 1.5% and 1.2%. Multiple HPV mRNA infections were most common in women < 25 years (7.3%) and rare in older age groups (≤0.4%), yielding an overall prevalence of multiple infections of 2.7% in women < 40 years, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

HPV mRNA positivity by age group, genotype and multiple infections in the co-testing cohort.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

In this real-world cohort of 11,395 women < 40 years, co-testing with a targeted 3-type HPV mRNA assay (HPV16/18/45) plus cytology increased sensitivity for CIN2+ from 63.7% with cytology alone to 71.0% (absolute +7.3 percentage points; p = 0.034). Co-testing also improved risk stratification: double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+) had the highest CIN2+ risk (58.3%), whereas double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology) had very low long-term risk (3.3%) and no observed cancers. Genotype-specific analyses showed the highest PPV for HPV16 (57.1%), with lower PPVs for HPV18 and HPV45.

4.2. HPV mRNA Versus Cytology

Within the co-testing cohort, HPV mRNA positivity alone identified a high-risk group (PPV 46.0%), outperforming low-grade cytology (PPV 35.6%) at similar sensitivity (~50%). The NPV of a negative HPV mRNA result (94.8%) was comparable to that of normal cytology (94.7%). Compared with high-grade cytology (ASC-H+), which had higher PPV (76.5%) but lower sensitivity (29.8%), HPV mRNA expanded case ascertainment while maintaining high specificity (93.9%). These findings align with prior reports that E6/E7 mRNA testing enriches for clinically meaningful disease and improves program sensitivity in younger women [11,17]. In our cohort, 131/262 women who developed CIN2+ during 8–10 years of follow-up were HPV mRNA-positive at baseline, corresponding to an overall CIN2+ sensitivity of 50.0% for the 3-type mRNA assay used as a stand-alone test. This lower long-term sensitivity compared with multi-type HPV DNA assays (e.g., 79.6% CIN2+ and 69% cancer sensitivity over 5 years with a 13-type HPV DNA test in Katki et al. [24]) likely reflects both the restricted genotype panel (HPV16/18/45 only) and the extended follow-up period, during which new infections with other HPV types may have arisen.

Our finding that HPV mRNA testing and low-grade cytology (ASC-US+) had similar sensitivity for CIN2+, but that HPV mRNA provided higher PPV and NPV, is consistent with earlier Norwegian work using the same 3-type assay. Al-Shibli et al. reported that among 25–39-year-old women with normal cytology, a positive HPV mRNA result conferred a CIN3+ risk of 28.6%, whereas the risk after a negative test was only 0.8%, illustrating the strong discriminative value of mRNA positivity in younger women [11]. Westre et al. likewise showed that applying the 3-type HPV mRNA test as a quality-control tool in women <40 years with normal cytology increased program sensitivity for CIN3 by approximately 17–18%, without an excessive rise in colposcopy referrals [17]. Taken together with our results, these studies support the use of E6/E7 mRNA testing as a complementary tool to cytology in younger women, enriching for clinically significant disease while maintaining high reassurance in mRNA-negative women.

4.3. Cotesting Versus Cytology Alone

Co-testing yielded a statistically significant gain in sensitivity compared with cytology alone and created clinically useful risk strata across concordant and discordant results. Double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+) warrant expedited colposcopy, whereas double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology) can be safely deferred. Women with HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology had a CIN2+ risk of 35.3%, underscoring the incremental detection of high-grade disease beyond morphology alone. The absence of cancers among double-negative women supports longer screening intervals after a negative co-test [11]. The higher CIN2+ risk in the HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology group compared with the HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-US group is biologically plausible: detection of E6/E7 mRNA from HPV16/18/45 reflects a transcriptionally active transforming infection that may precede overt morphological atypia [12,25], whereas ASC-US in HPV mRNA-negative women often represents reactive or transient changes without ongoing oncogene expression, or infections with non-detected HPV types, and therefore carries a lower risk of progression [26,27].

The observed absolute gain of 7.3 percentage points in CIN2+ sensitivity with co-testing versus cytology alone is modest but clinically relevant, given the low underlying cancer incidence in women under 40. Similar sensitivity gains from combining HPV testing with cytology have been reported in other settings and age groups, where co-testing or primary HPV testing reduces the proportion of cancers arising after a negative screen [21,27,28]. In our study, co-testing also improved predictive values: the PPV for CIN2+ increased from 46.0% with HPV mRNA alone to 58.3% in double-positive women, while the NPV rose from 93.9% to 96.7% in double-negative women. These gradients mirror the risk-stratified patterns described in previous Norwegian and international studies, in which HPV mRNA positivity—especially for HPV16—identifies women who benefit from closer follow-up, whereas double-negative results support safely extended screening intervals [11,17,25].

4.4. HPV Genotype (16, 18, 45)

HPV16 positivity conferred the highest immediate CIN2+ risk (PPV 57.1%), consistent with its well-documented predominance in CIN3+ and invasive cervical cancer. Although PPVs were lower for HPV18 and HPV45, both genotypes are overrepresented among adenocarcinomas and cancers at younger ages, and part of their carcinogenic potential may not be fully captured by a CIN2+ endpoint restricted to squamous lesions. Similar genotype-specific gradients have been reported in mRNA triage studies of HPV DNA–positive women, where HPV16 mRNA positivity carries the highest CIN2+ risk, followed by HPV18 and other types [15,29]. Taken together, these data support a tiered approach in which genotype-specific mRNA results—particularly HPV16—inform triage intensity, with HPV16-positive women prioritized for the most immediate work-up and HPV18/45-positive women followed closely in conjunction with cytology findings [11,17,29].

4.5. Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer incidence during follow-up was low (0.1% overall), with fewer cancers observed in the co-testing cohort (4/2807) than in the cytology-only cohort (12/8588). No cancers occurred among double-negative women, highlighting the high reassurance value of a negative co-test in this age group [11]. Our findings are consistent with long-term data from other HPV-based screening cohorts. In the 12-year follow-up study by Rad et al., using a 5-type HPV mRNA assay (HPV16/18/31/33/45) in women aged 25–69 years, the incidence of cervical cancer among HPV mRNA-negative women was 2 per 100,000 woman-years [30], comparable to the incidence observed after a negative 13-type HPV DNA test in large European and U.S. studies. In the meta-analysis of four European trials by Ronco et al., the cumulative incidence of cervical cancer after a negative HPV DNA test was approximately 2 per 100,000 woman-years at 6.5 years of follow-up [21], and in the study by Katki et al. the incidence among HPV DNA–negative women was 3.8 per 100,000 woman-years [24]. In the Netherlands, HPV DNA-based screening is offered at ages 30, 35, 40, 50 and 60, with screening intervals extended from 5 to 10 years for older women with previous negative HPV tests [31,32], reflecting the high long-term reassurance conferred by a negative HPV result. Together, these external data support our observation that double-negative women have a very low long-term risk of cervical cancer and reinforce the notion that negative HPV-based tests (including targeted mRNA assays) provide strong reassurance over extended intervals.

4.6. Risk Stratification

Effective screening separates women into groups with actionable differences in near- and long-term risk. In our study, co-testing created wide risk gradients, from 3.3% CIN2+ risk in double-negative women to 58.3% in double-positive women, supporting more efficient referral to colposcopy and reduced follow-up in low-risk women. Importantly, mRNA positivity identified a high-risk subgroup with normal cytology (35.3% CIN2+), who would not have been flagged by morphology alone. These findings support personalized management pathways that escalate work-up for double-positive and mRNA-positive/NILM results, and de-escalate surveillance for double-negative women, in whom both our data and external evidence indicate a very low long-term risk of cervical cancer [6].

4.7. Other Molecular Approaches, Including Self-Sampling and E4/L1 Biomarkers

Beyond targeted HPV mRNA co-testing, several molecular strategies are being explored to optimize cervical screening. HPV DNA testing on self-collected vaginal samples has shown sensitivity for CIN2+ comparable to clinician-collected specimens, while substantially increasing participation among under-screened women in randomized trials and meta-analyses [33]. Such self-sampling approaches are now being incorporated into screening programs as an alternative for women who do not attend regular screening and could, in the future, be combined with mRNA-based triage [34,35]. Tissue biomarkers are also under investigation to refine histological classification of squamous intraepithelial lesions. In particular, combined immunohistochemical assessment of HPV E4 protein and the L1 major capsid protein has been proposed to distinguish productive infections from transforming lesions; Przybylski et al. showed that E4/L1 expression patterns correlated with CIN grade and may help separate regressive low-grade lesions from those with higher malignant potential [36]. These evolving molecular tools complement our findings by illustrating how HPV-related biomarkers—whether in cytology samples, self-samples or tissue—can support more precise, risk-based management within modern screening programs.

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths include the population-based design within an organized national screening program, with complete capture of all cervical cytology, HPV tests and histological specimens from a clearly defined geographical catchment area, a large sample size (n = 11,395), and long follow-up (8–10 years) with histologically verified CIN2+ as the primary endpoint. Use of a single pathology laboratory (UNN) with standardized cytology and HPV mRNA protocols, together with linkage to regional and national registries and local reminder routines (including self-sampling for non-attenders), helped ensure near-complete follow-up and minimize loss to follow-up. The intervention and control cohorts had similar overall CIN2+ prevalence (9.3% vs. 9.6%), suggesting comparable baseline risk and supporting internal validity.

Important limitations must also be acknowledged. First, the non-randomized, calendar-cohort design (2013–2014 vs. 2015) may introduce period effects (e.g., changes in referral thresholds or clinical practice over time) that could confound comparisons between cohorts. Second, work-up (verification) bias is possible because not all women underwent biopsy; although we sought to mitigate this through long passive follow-up and by classifying women without histology as no CIN2+ unless a later CIN2+ diagnosis occurred, some residual differential verification cannot be excluded. Third, although cytology was usually interpreted blinded to HPV mRNA results, limited unblinding may have occurred within the quality-assurance framework and could have influenced individual diagnostic decisions. Fourth, the mRNA assay targeted only three genotypes (16/18/45); CIN2+ caused by other HPV types would be mRNA-negative by design, which enhances specificity in younger women but limits direct comparison with broader HPV DNA-based strategies. Finally, individual-level covariates such as vaccination status, smoking, parity and sexual behavior were not available, precluding adjustment for potential confounders and limiting generalizability to fully vaccinated cohorts and to settings using contemporary primary HPV DNA screening with extended genotyping.

4.9. Clinical Implications Within Evolving Screening Practice

Norway has transitioned to HPV-based primary screening with extended genotyping and reflex cytology [37]. Within this framework, a targeted HPV mRNA assay can enhance quality assurance by identifying women with normal cytology who nevertheless have substantial risk despite NILM, support risk-based triage in which genotype-specific mRNA positivity—particularly HPV16—signals the need for closer follow-up, and provide strong reassurance for double-negative women, thereby justifying extended screening intervals. The zero-cancer rate among double-negative women and the pronounced PPV gradients observed in our study argue for integrating mRNA-informed risk tiers into modern screening algorithms to optimize referrals and reduce over-management.

4.10. Future Research

Key priorities for future work include (i) formal cost-effectiveness analyses of targeted HPV mRNA co-testing strategies in increasingly vaccinated cohorts; (ii) prospective evaluation of mRNA-guided triage embedded within primary HPV DNA screening workflows, including in settings with extended genotyping; (iii) head-to-head comparisons of targeted 3-type HPV mRNA testing versus extended HPV DNA genotyping algorithms (with and without self-sampling components); and (iv) prospective validation of risk-based management thresholds (e.g., immediate colposcopy for double-positive or HPV16-positive/NILM results, and extended intervals for double-negative women). Linkage with national registries on vaccination status, treatments and long-term outcomes will be essential to refine absolute-risk estimates and inform future guideline updates.

5. Conclusions

Co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay (HPV16/18/45) and liquid-based cytology improved detection performance compared with cytology alone in women < 40 years in this retrospective, population-based cohort. Sensitivity for CIN2+ increased from 63.7% with cytology alone to 71.0% with co-testing (absolute +7.3 percentage points; relative +11.4%; p = 0.034). Co-testing produced wide, clinically relevant risk gradients: CIN2+ risk was 58.3% in double-positive women (HPV mRNA-positive and ASC-US+) and 3.3% in double-negative women (HPV mRNA-negative and normal cytology), with no cancers observed over 8–10 years in the latter group. HPV mRNA-positive/normal cytology carried higher CIN2+ risk (35.3%) than HPV mRNA-negative/ASC-US+ (23.0%; p = 0.011), underscoring limitations of cytology alone and the incremental value of E6/E7 mRNA detection for risk stratification in this age group.

Within the context of an organized, cytology-based screening program and a largely unvaccinated birth cohort, these findings support co-testing with a 3-type HPV mRNA assay and cytology as a useful approach for improving individual risk stratification—prioritizing expedited colposcopy for double-positive and HPV mRNA-positive/normal-cytology results, while allowing longer intervals for double-negative women. However, the non-randomized, calendar-based design, the restriction to three HPV genotypes, and the absence of individual data on vaccination and other potential confounders limit causal inference and direct extrapolation to fully vaccinated cohorts and to contemporary primary HPV DNA screening frameworks with extended genotyping. In present-day programs, targeted HPV mRNA testing should therefore be considered primarily as a candidate quality-assurance or triage tool. Its optimal role, if any, will need to be confirmed through prospective studies and formal cost-effectiveness evaluations in vaccinated populations before routine policy adoption can be recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.S.; methodology, S.W.S. and G.S.S.; validation, S.W.S., G.S.S. and M.B.; formal analysis, S.W.S.; investigation, M.B. and S.W.S.; resources, S.W.S. and G.S.S.; data curation, S.W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and S.W.S.; writing—review and editing, M.B., G.S.S. and S.W.S.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, S.W.S. and G.S.S.; project administration, S.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, REC Nord (protocol code 2013/497/REK Nord) on 13 March 2013. As a quality-assurance project with waiver of informed consent, and by the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN) Data Protection Officer (reference 2016/2873).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because only leftover screening material collected during routine care was used, no additional sampling or contact with patients occurred, and all analyses were performed on anonymized datasets within a quality-assurance framework.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified analysis datasets and code supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data cannot be shared publicly due to privacy and ethical restrictions under Norwegian data protection regulations and institutional policies. Aggregate results are provided within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Department of Clinical Pathology at the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN) for their collaboration, and the laboratory personnel involved in HPV testing, cytology and histopathology for their excellent technical support. This work is based on the master thesis of the first author, conducted at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. We also acknowledge PreTect AS for assay-related technical information regarding the PreTect SEE mRNA test; PreTect AS had no role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or the decision to submit the manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT (GPT-5) for copy-editing to improve spelling, grammar, clarity and flow. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| CIN2+ | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse |

| CIN3 | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 |

| AIS | Adenocarcinoma in situ |

| LBC | Liquid-based cytology |

| NILM | Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy |

| ASC-US | Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance |

| ASC-US+ | ASC-US or more severe cytological abnormalities (ASC-US, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, AIS, CxCa) |

| LSIL | Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| ASC-H | Atypical squamous cells—cannot exclude HSIL |

| HSIL | High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| ISC | Intrinsic sample control |

| UNN | University Hospital of North Norway |

| REC | Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC Nord) |

| NASBA | Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CxCa | Cervical cancer |

References

- Arbyn, M.; Castellsagué, X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L.; Saraiya, M.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2675–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravdal, B.H.; Lönnberg, S.; Skare, G.B.; Sulo, G.; Bjørge, T. Cervical cancer in women under 30 years of age in Norway: A population-based cohort study. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegoke, O.; Kulasingam, S.; Virnig, B. Cervical cancer trends in the United States: A 35-year population-based analysis. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.Y.F.; Bierman, R.; Beardsley, L.; Chang, C.J.; Burk, R.D. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human Papillomaviruses; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2007; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 90. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321760/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Perkins, R.B.; Guido, R.S.; Castle, P.E.; Chelmow, D.; Einstein, M.H.; Garcia, F.; Huh, W.K.; Kim, J.J.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Nayar, R.; et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J. Low Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 102–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, S.J.; Krist, A.H.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.; Kemper, A.R.; Kubik, M.; et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018, 320, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572321/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Arbyn, M.; Anttila, A.; Jordan, J.; Ronco, G.; Schenck, U.; Segnan, N.; Wiener, H.; Herbert, A.; von Karsa, L. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition—Summary document. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkehelseinstituttet (Norwegian Institute of Public Health). Kvalitetsmanual for Livmorhalsprogrammet [Quality Manual for the Cervical Cancer Screening Programme]; Folkehelseinstituttet: Oslo, Norway, 2025; Available online: https://www.fhi.no/kreft/kreftscreening/livmorhalsprogrammet/helsepersonell/kvalitetsmanual/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Al-Shibli, K.; Mohammed, H.A.L.; Maurseth, R.; Fostervold, M.; Werner, S.; Sørbye, S.W. Impact of HPV mRNA types 16, 18, 45 detection on the risk of CIN3+ in young women with normal cervical cytology. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, P.; Zannoni, G.F.; Ricci, C.; D’Onghia, S.; Trivellizzi, I.N.; Di Franco, A.; Vellone, V.G.; Durante, M.; Fadda, G.; Scambia, G.; et al. Clinical performance of human papillomavirus E6 and E7 mRNA testing for high-grade lesions of the cervix. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3895–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, P.; Rauen, K.A.; McCormick, F. The duality of human oncoproteins: Drivers of cancer and congenital disorders. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Tommasino, M.; Depuydt, C.; Dillner, J. Are 20 human papillomavirus types causing cervical cancer? J. Pathol. 2014, 234, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjalma, W.A.; Fiander, A.; Reich, O.; Powell, N.; Nowakowski, A.M.; Kirschner, B.; Koiss, R.; O’Leary, J.; Joura, E.A.; Rosenlund, M.; et al. Differences in human papillomavirus type distribution in high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cervical cancer in Europe. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørbye, S.W.; Falang, B.M.; Antonsen, M. Distribution of HPV Types in Tumor Tissue from Non-Vaccinated Women with Cervical Cancer in Norway. J. Mol. Pathol. 2023, 4, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westre, B.; Giske, A.; Guttormsen, H.; Wergeland Sørbye, S.; Skjeldestad, F.E. Quality control of cervical cytology using a 3-type HPV mRNA test increases screening program sensitivity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2+ in young Norwegian women—A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkehelseinstituttet (Norwegian Institute of Public Health). HPV-Vaksine (Humant Papillomavirus). Vaksinasjonsveilederen for Helsepersonell; Folkehelseinstituttet: Oslo, Norway, 2025; Available online: https://www.fhi.no/va/vaksinasjonshandboka/vaksiner-mot-de-enkelte-sykdommene/hpv-vaksinasjon/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Folkehelseinstituttet (Norwegian Institute of Public Health). Tidlig Innhentingsvaksinering mot HPV gir Ekstra Helsegevinst. 10 January 2020. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/kreft/kreftforskning/nyheter/tidlig-innhentingsvaksinering-mot-hpv-gir-ekstra-helsegevinst/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2017, 92, 241–268. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9219-241-268 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, K. Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falang, B.M. PreTect SEE. Protocols.io. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/pretect-see-e6nvw6qxwgmk/v1 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Katki, H.A.; Kinney, W.K.; Fetterman, B.; Lorey, T.; Poitras, N.E.; Cheung, L.; Demuth, F.; Schiffman, M.; Wacholder, S.; Castle, P.E. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: A population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørbye, S.W.; Arbyn, M.; Fismen, S.; Gutteberg, T.J.; Mortensen, E.S. HPV E6/E7 mRNA testing is more specific than cytology in post-colposcopy follow-up of women with negative cervical biopsy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.; Schiffman, M.; Tarone, R.; ALTS Study Group. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: Baseline results from a randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Sasieni, P.; Meijer, C.J.; Clavel, C.; Koliopoulos, G.; Dillner, J. Chapter 9: Clinical applications of HPV testing: A summary of meta-analyses. Vaccine 2006, 24 (Suppl. S3), S78–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, J.C.; Schiffman, M.; Katki, H.A.; Castle, P.E.; Fetterman, B.; Wentzensen, N.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.; Cheung, L.C.; Kinney, W.K. Reassurance against future risk of precancer and cancer conferred by a negative human papillomavirus test. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørbye, S.; Falang, B.M.; Antonsen, M.; Mortensen, E. Genotype-specific HPV mRNA triage improves CIN2+ detection efficiency compared to cytology: A population-based study of HPV DNA-positive women. Pathogens 2025, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.; Sørbye, S.W.; Tiwari, S.; Løchen, M.-L.; Skjeldestad, F.E. Risk of intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse (CIN3+) among women examined by a 5-type HPV mRNA test during 2003 and 2004, followed through 2015. Cancers 2023, 15, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). Cervical Cancer Screening Programme—Frequently Asked Questions for Professionals. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/cervical-cancer-screening-programme/professionals/faq (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Bevolkingsonderzoek Nederland. Cervical Cancer Screening—The Invitation. Available online: https://www.bevolkingsonderzoeknederland.nl/en/cervical-cancer/the-invitation/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Yeh, P.T.; Kennedy, C.E.; de Vuyst, H.; Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda Flores, C.E.; Gomez Gutierrez, G.; Ortiz Leon, J.M.; Cruz Rodriguez, D.; Sørbye, S.W. Self-collected versus clinician-collected cervical samples for the detection of HPV infections by 14-type DNA and 7-type mRNA tests. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, C.E.A.; Falang, B.M.; Gómez-Laguna, L.; Gutiérrez, G.G.; León, J.M.O.; Uribe, M.; Cruz, O.; Sørbye, S.W. Enhancing Cervical Cancer Screening with 7-Type HPV mRNA E6/E7 Testing on Self-Collected Samples: Multicentric Insights from Mexico. Cancers 2024, 16, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, M.; Pruski, D.; Millert-Kalińska, S.; Krzyżaniak, M.; de Mezer, M.; Frydrychowicz, M.; Jach, R.; Żurawski, J. Expression of E4 Protein and HPV Major Capsid Protein (L1) as A Novel Combination in Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Samlet Informasjon Vedrørende «HPV-Primærscreening» med Utvidet Genotyping og Aldersbestemt Utredningsstrategi» [Compiled Information on “Primary HPV Screening with Extended Genotyping and Age-Stratified Management”]; Norwegian Institute of Public Health: Oslo, Norway, 2024; Available online: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/livmorhalsprogrammet/rapporter/andre-rapporter/20240208_samlet_rapport_utvidet_genotyping-1.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).