Abstract

The landscape of oncologic therapies has undergone large changes since the introduction of monoclonal antibody (mAb) based immunotherapies in the late 1990s and early 2000s. MAb-based therapeutics, also called biologics or large molecules, have distinct pharmacological characteristics compared to chemotherapeutics and small molecules. Development of biologics requires thorough assessment of pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) characteristics to ensure safety and demonstration of efficacy. This review provides an overview of the clinical pharmacology packages of biologics for the treatment of oncologic malignancies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) over the past decade (January 2015 and August 2025). The conduct of population PK (PopPK) and exposure-eesponse (E-R) analyses, as well as assessments for drug–drug interactions (DDIs), immunogenicity, and QT prolongation risk are discussed. The aim of this review is to provide insight into the clinical pharmacology assessments for approval of antibody-based therapies in oncology as well as provide a longitudinal view of clinical pharmacology packages in this space.

1. Introduction

Targeted monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based immunotherapies, also referred to as biologics or large molecules, emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s for the treatment of oncologic malignancies. These molecules bind to tumor specific antigens to trigger or modulate an immune response against tumor cells. Since their emergence, the treatment and drug development landscape for oncology has undergone massive changes. Previously, treatment options were heavily centered around systemic cytotoxic agents (i.e., chemotherapies) that, despite their relative efficacy, are limited by significant toxicities due to their non-specific targeting of both healthy and malignant cells. In an effort to improve toxicity profiles of oncologic therapies, development of targeted immunotherapies has been a focus of modern drug development. In the 21st century, the development of targeted biologics has rapidly expanded from traditional mAbs to now encompass therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action (MOAs), including antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific T-cell engagers (TCEs), and fusion proteins.

The development programs of biologics differ greatly from those of small molecule therapeutics due to differences in pharmacology, routes of administration, metabolism pathways, and various other factors. The differences between biologics and small molecules are reflected in the clinical pharmacology packages submitted to the FDA. For example, mAbs are primarily cleared from the body via proteolytic degradation and not via Phase I/II metabolic pathways such as Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, and thus, biologic clinical pharmacology packages do not typically utilize dedicated clinical drug–drug interaction studies, but rather utilize other methods for evaluation. Furthermore, because biologics are administered via intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (SC) routes, food effect studies are not conducted. Lastly, biologics typically have longer half-lives compared to small molecules, though clearance and half-life of a biologic may be impacted by target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) and/or by the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADA). TMDD is a target-mediated clearance pathway that results in rapid clearance of the mAb as it is bound by readily available target sites, while ADA formation may occur based on the immune response elicited by the molecule. The potential impact of TMDD and/or ADA adds an additional layer of complexity to biologic drug development.

As a whole, clinical pharmacology packages describe the pharmacology and pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics of a molecule and therefore are of particular importance within a submission to a regulatory agency for approval. Clinical pharmacology assessments for biologics generally include population pharmacokinetics (PopPK) and exposure–response (E-R) analyses, immunogenicity assessments, DDI assessments, and QT/QTc prolongation risk assessments. However, the development and clinical pharmacology package for each molecule is unique and tailored to the molecule’s pharmacological characteristics. An aspect of a clinical pharmacology package that has been of particular focus within oncology drug development in recent years is dose optimization. Compared to cytotoxic agents, which are generally dosed at the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) reached in clinical trials, biologics in oncology typically exhibit a bell-shaped curve regarding safety and efficacy, requiring thorough risk–benefit analysis when selecting a proposed dosing regimen. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launch of Project Optimus in 2021 placed greater emphasis on dose optimization, increasing focus on obtaining robust pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data starting in Phase 1 clinical trials to ensure adequate characterization of dose–response relationships early in development [1]. A robust understanding of these relationships early in development would then be used to inform dose selection for pivotal trials and proposed dosing regimens.

As the field of oncology evolves and advances in targeted therapies introduce new molecules with novel mechanisms to the development landscape, it is important to understand that clinical pharmacology packages are rarely one-size-fits-all. Though the foundational requirements remain the same, additional consideration may be necessary on a molecule-to-molecule basis to address and characterize potential risks. The current manuscript presents a comprehensive review of the clinical pharmacology packages in biologic license applications (BLAs) for mAb-based therapies and fusion proteins approved by the FDA for an oncologic indication between January 2015 and August 2025. The goal of this review is to deliver insight into clinical pharmacology packages over the past decade and provide a longitudinal view of therapeutic protein development. It is anticipated that this review will enable further development of robust clinical pharmacology packages and highlight additional steps taken to gain regulatory approval.

2. Materials and Methods

To collect a list of FDA-approved BLAs, files were downloaded from Drugs@FDA.gov (accessed on 1 September 2025) [2]. Annual lists of novel drug approvals published by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) were pulled from FDA.gov (accessed on 1 September 2025) [3]. From these listings, mAb-based therapies and fusion proteins with original BLA approvals for oncologic indications approved between 1 January 2015 and 31 August 2025 were included in this review and represent the full scope of this review. BLA review files associated with the first approval of a molecule were selected for this review. A single exception was made in the case of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), which was initially approved in 2000, removed from market due to safety concerns in 2010, and approved at a lower dose after additional dose optimization in 2017. BLA review files for gemtuzumab ozogamicin were only available from the 2017 approval. The information within the 2017 gemtuzumab ozogamicin BLA package utilized data obtained from a Phase 3 randomized trial (ALFA-0701) where a lower dose was evaluated. The 2017 approval at a lower dose could be seen as representative of a shift towards dose optimization within oncology drug development even prior to Project Optimus.

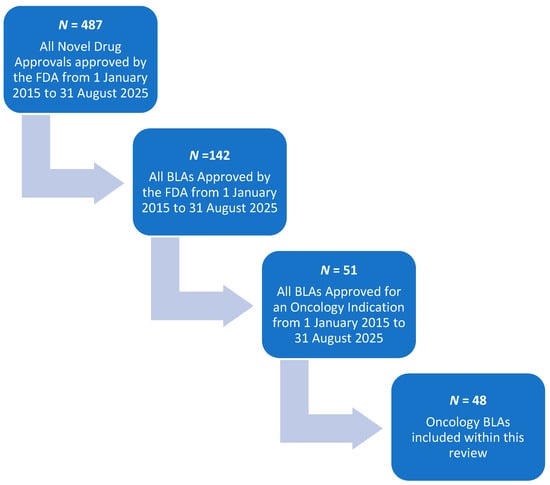

A schematic outlining the methods for selection of BLAs for this review is provided in Figure 1. From January 2015 to August 2025, there were a total of 487 novel drug approvals. New Drug Approvals (NDAs) for small molecule therapies were removed from the dataset, following which 142 original BLAs for new biologic therapies remained. Of these, 51 BLAs were approved for an oncologic indication. Note that this review focuses on antibody-based therapies and fusion proteins; therefore, filgrastim and asparaginase based therapies were not included. Additionally, due to its route of administration directly into the bladder and minimal systemic exposures, Anktiva (nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln) was not included in the dataset. A total of 48 BLAs were included in this review [3].

Figure 1.

Schematic for BLA selection.

Clinical pharmacology packages were obtained via FDA application review files, including Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review, Multi-Discipline Review, Summary Review, and Other Review files. These files are available at Drugs@FDA.gov [2]. Specifically, Other Review files were utilized when they contained QT/QTc Interdisciplinary Review Team responses with detailed information regarding QT prolongation assessments not otherwise found in the Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review or the Multi-Discipline Review. FDA review files were thoroughly evaluated. Published literature, product labels, and approval letters were also reviewed when appropriate. The information obtained includes initial approval indication, modality, mechanism of action, route of administration, approved dosing regimen, conduct of population pharmacokinetics (PopPK) and exposure–response (E-R) analyses, drug–drug interaction (DDI) assessments, QT/QTc prolongation assessments, immunogenicity assessments, and post-marketing requirements or commitments (PMRs or PMCs). PMRs and PMCs were collected from the approval letters associated with the BLA review, as well as using the Post-Marketing Requirements and Commitments Searchable Database available at accessdata.fda.gov [4].

3. Oncology Biologic License Application (BLA) Approvals and Clinical Pharmacology Packages

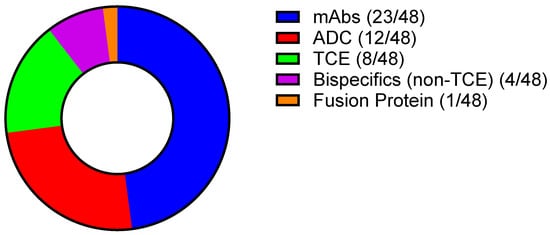

In this review, the clinical pharmacology packages for antibody-based therapies and fusion proteins with original BLA approvals for the treatment of an oncologic indication approved over the past decade (January 2015 to August 2025) were evaluated. Of the 48 molecules included in this review, 23 are mAbs, 12 are antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), 12 are bispecific molecules, 8 of which are bispecific T-cell engagers (TCEs), and 1 molecule is a fusion protein fused to diphtheria toxin (Figure 2). ADCs are molecules that comprise a cytotoxic small molecule payload conjugated to a targeted antibody. When the antibody portion of the ADC is bound to the tumor-specific target, the ADC is internalized and the cytotoxic payload is released, inducing apoptosis of the tumor cell. The 12 ADC molecules included in this review utilize various cytotoxic payloads including monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), topoisomerase I inhibitors, calicheamicin, pyrrolobenzodiazepines (PBD), DM4, and PE38, a Pseudomonas exotoxin. TCEs are bispecific molecules that target a tumor-specific antigen with one arm, and target CD3 on T-cells with the other, bringing the tumor cells in close proximity with the T-cell. The bispecific nature of these molecules allows for targeted T-cell activity and enhanced tumor cell killing. A breakdown of the targets, mechanisms of action (MOAs), and indications is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of modalities included in this review (Created with GraphPad ver. 10.4.1).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical pharmacology packages evaluated.

The clinical pharmacology packages of ADCs require additional considerations compared to that of traditional mAbs. Concentrations of multiple analytes—the intact ADC (ADC; antibody with linker-payload intact), total antibody (tAb; antibody with or without the linker-payload intact), and unconjugated payload (free payload; payload that has been released from the ADC)—should be collected and evaluated throughout development. To characterize the PK of the unconjugated payload, elements of small molecule development should be incorporated into the clinical pharmacology package. For example, the potential impact of the unconjugated payload to cause DDIs or prolong the QT/QTc interval should be evaluated. With regards to the E-R and PopPK analyses, most ADC clinical pharmacology packages in this review included the unconjugated payload as an analyte in addition to the intact ADC and/or tAb.

The development and clinical pharmacology package for a TCE molecule also requires consideration of additional elements compared to a traditional mAb. Due to the nature of TCEs activating the immune system, additional precautions such as cytokine monitoring are needed to evaluate the risk of inducing cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Incorporating sampling for cytokine measurements strategically within clinical trial protocols is important for the development of PK/PD models and E-R analyses to guide decision making and achieve safe and efficacious dosing. These considerations ensure the safety of patients as well as proper characterization of the pharmacology and PK of the TCE. Cytokine release also has the potential to downregulate cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme expression, which should be considered when evaluating for DDIs for TCEs as well as other molecules that modulate cytokine release. Lastly, because TCEs are generally more engineered compared to traditional mAbs, there is higher potential for immunogenicity, which should also be considered in their development.

4. Post-Marketing Requirements (PMRs) and Post-Marketing Commitments (PMCs)

Post-Marketing Requirements (PMRs) and Post-Marketing Commitments (PMCs) may be issued by the FDA upon review and approval of a New Molecular Entity (NME). PMRs/PMCs are studies and clinical trials that sponsors are required to conduct or have committed to conduct after approval to gather additional information about a product’s safety, efficacy, or optimal use. Thus, PMRs/PMCs may be representative of information that was not adequately established in the BLA submission. In addition to PMRs/PMCs, approval of a molecule may be contingent upon accelerated approval requirements to confirm clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial and/or may be subject to pediatric requirements to conduct additional clinical trials in the pediatric patient population.

Of the 48 approvals included in this review, nearly all approvals (94%; 45/48) were issued at least one PMR, PMC, accelerated approval requirement, or pediatric requirement. A total of 60% (29/48) of approvals were granted accelerated approval by the FDA, all of which were issued accelerated approval requirement(s) to confirm the anticipated clinical benefit that had been established via the surrogate endpoint through a confirmatory clinical trial. If clinical benefit cannot be confirmed in a confirmatory trial, accelerated approval may be withdrawn.

With regards to PMRs/PMCs specifically, 79% (38/48) of approvals received at least one PMR or PMC. A total of 31% (15/48) of approvals were issued one or more PMRs/PMCs related to safety to further characterize specific adverse events, including infusion-related reactions. The adverse events listed in the PMRs/PMCs were variable and associated with the toxicities observed in clinical trials. Characterization of the adverse events as issued in the PMRs/PMCs ranged from (1) submission of datasets from across clinical studies, (2) conducting integrated safety analyses, (3) conducting long-term safety monitoring, (4) amending study protocols for ongoing studies to include additional assessments, or (5) conduct of additional clinical studies. A total of 21% (10/48) of approvals were issued PMCs related to efficacy. These PMCs included completing and submitting data upon completion of pivotal studies or updating current analyses with additional outcomes.

PMRs and PMCs to further characterize PK, safety, and efficacy in specific subpopulations (i.e., special populations) were issued in 48% (23/48) of approvals. These PMRs/PMCs were issued in cases where the FDA determined that one or more special populations were not adequately represented in the clinical trial population to inform labeling. These PMRs/PMCs were issued for further evaluation in patients with renal or hepatic impairment (issued to 10% [5/48] of approvals), pediatric populations (issued to 17% [8/48] of approvals, including approvals issued pediatric requirements), patients who were 65 years of age or older (issued to 4% [2/48] of approvals), and patients with specific genomic markers (issued to 4% [2/48] of approvals). The most common special population that the FDA issued PMRs/PMCs for further evaluation of PK, safety, and efficacy data in was patients of U.S. ethnic and racial minorities (31%; 15/48). For these PMRs/PMCs, sponsors were issued to conduct additional studies with a clinical trial population representative of the U.S. patient population. Information regarding PMRs/PMCs issued with regards to dose optimization, immunogenicity, DDI, or QT assessments are discussed separately in the E-R analysis, Immunogenicity, DDI, and QT assessment sections, respectively.

5. Clinical Pharmacology Assessments

5.1. Population PK (PopPK) Analyses

PopPK modeling is an important tool for characterizing a molecule’s PK profile across the patient population and evaluating potential sources of interindividual variability within the PK data. PopPK models evaluate the impact of intrinsic factors, such as body weight, age, race/ethnicity, as well as extrinsic factors, such as concomitant medications or formulation type, as covariates to assess their impact on PK parameters (e.g., clearance (CL) and volume of distributions (Vz)). The FDA Guidance “Population Pharmacokinetics Guidance for Industry” [101] further outlines the applications for PopPK analyses to inform drug development. The reliability of results from PopPK analyses to inform dosing recommendations for specific patient sub-groups is dependent upon sufficient PK sample collection in an adequate number of patients during clinical trials to fully characterize the PK profile. For example, clinical pharmacology packages that failed to include adequate numbers of patients of U.S. racial and ethnic minorities in the PK population were deemed to have insufficient evidence to evaluate the impact of race or ethnicity as a covariate in the PopPK analyses. In one such clinical pharmacology package, PK data to assess the impact of racial categories was available in mainly White (n = 510) and Asian (n = 423) patients, with a relatively lower number of patients of other racial categories (n = 79). There was little PK data in Black or African American patients (n = 19). A PMC was issued to conduct an integrated analysis of data from clinical trials, observational studies, and post-marketing reports to further characterize the safety, efficacy, PK, and PD of the drug in the underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups, especially Black or African American patients given their underrepresentation in the clinical trial data [93,94].

The PK of most molecules included in this review were described with a 2-compartment model with linear elimination. For molecules that exhibited Michaelis–Menten PK (non-linear PK) due to TMDD, the effect of covariates was assessed on the linear phase of elimination. Within the clinical pharmacology packages included in this review, the intrinsic factors that were most commonly evaluated as covariates in the PopPK analysis (evaluated in >90% [more than 44 of 48] of approvals) were related to body size (e.g., body weight, body surface area [BSA], body mass index [BMI], etc.), age, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, and laboratory values associated with renal and hepatic function. It is important to note that, in oncology drug development, dedicated renal or hepatic impairment studies in healthy volunteers are generally not conducted due to the toxicity profile of oncology drugs. Furthermore, biologics are catabolized via proteolytic degradation and not metabolized via renal or hepatic pathways. PopPK analyses can be used instead to evaluate the impact of renal or hepatic dysfunction, given that there is an adequate number of patients within the PopPK dataset to represent this population with adequate PK sampling data pooled across multiple clinical trials. Insufficient PK data in patients with renal or hepatic impairment is likely to result in PMRs/PMCs. In one BLA submission, the results of the PopPK analysis determined that there was no meaningful difference in exposure (Cmax and Cavg) between the mild or moderate renal impairment subgroups and those with normal renal function. However, the PopPK analysis population included mainly patients with mild (n = 118), moderate (n = 50), and normal (n = 159) renal function, with only one patient with severe renal impairment included in the moderate renal function group. Likely due to a lack of patients with severe renal impairment in the PopPK analysis, the FDA issued a PMR to conduct an open-label, non-randomized dose escalation trial to determine an appropriate dosing regimen in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment [51,52].

Other factors that were evaluated as covariates in a majority of clinical pharmacology packages included cancer/tumor type (e.g., tumor type, disease type, subtype, tumor histology etc.), ADA status, and disease/tumor characteristics including but not limited to baseline tumor burden, baseline tumor size, baseline number of metastatic sites, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status. To a lesser extent, the impact of potential DDIs and/or co-administered therapies on the PK, prior therapies, and target status were also evaluated. Other covariates evaluated in PopPK analyses were drug product or formulation and cytogenetics or genomic markers.

5.2. Exposure–Response (E-R) Modeling

Though one of the benefits of targeted immunotherapies is their improved safety profile compared to chemotherapeutics, the risk-to-benefit ratio should still be considered throughout development. Exposure–response (E-R) analyses evaluate the relationships between drug exposure and selected safety and efficacy endpoints and are an important facet of a clinical pharmacology package within the BLA submission. E-R analyses are key to determining a dose that appropriately balances the potential efficacy and safety risks of a molecule. Data used in exposure–safety and exposure–efficacy analyses are obtained from early phase clinical trials and can be used to support the selection of a recommended Phase 2 dose and the final proposed dose. Ideally, rich PK data from multiple dose levels would be used to conduct E-R analysis to ensure that adequate and thorough dose optimization has occurred. The FDA Guidance for Industry, “Exposure-Response Relationships: Study Design, Data Analysis, and Regulatory Applications” [102] further outlines the utility of E-R modeling.

E-R analyses for safety and efficacy were included in all but one of the clinical pharmacology packages in this evaluation. In the clinical pharmacology packages evaluated, exposure metrics for E-R analyses included area under the curve (AUC), maximal concentration (Cmax), and last observed concentration (Clast or Ctrough). Safety endpoints for E-R analyses were associated with the toxicities and adverse event profiles for each molecule. Adverse events were often measured by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Grade 1–5 scale. Efficacy endpoints such as overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and objective response rate (ORR) were commonly used as response metrics for efficacy. For the single clinical pharmacology package that did not include E-R analyses, it was stated in the BLA review that these analyses were not conducted due to insufficient PK data as no PK samples were collected in their Phase III trial. A PMR was issued to conduct a study to compare exposure and safety data from approximately 220 patients who completed treatment with this molecule. The main purpose of this study, in combination with historical experience observed in 1100 patients, was to analyze the risk of serious infusion reactions and neuropathy and the overall safety [5,6].

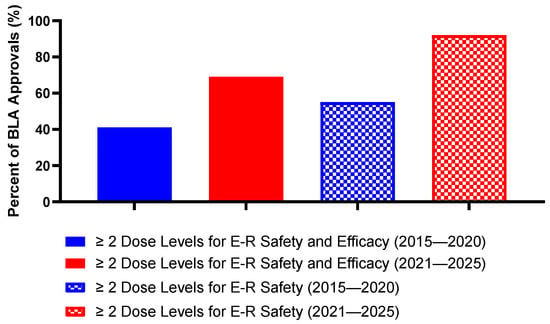

Evaluation of two or more dose levels is important to ensure that an E-R model can adequately support a dose selection decision. Of note, after the launch of Project Optimus in 2021, an emphasis on early optimization of dosing and evaluation of multiple dose levels after Phase 1 dose escalation has resulted in evident changes in the conduct of E-R analyses. Exposure–safety data has commonly used pooled data across multiple clinical trials, dose levels, and patient populations. However, because exposure–efficacy analyses typically utilize data from pivotal trials, prior to the launch of Project Optimus, exposure–efficacy analyses were more likely to include data from a single dose level. Overall, E-R analyses for safety were conducted at two or more dose levels in 75% (36/48) of clinical pharmacology packages evaluated, while only 56% (27/48) of clinical pharmacology packages evaluated two or more dose levels for both exposure–safety and exposure–efficacy analyses. In the years prior to Project Optimus (2015–2020), 55% (12/22) of BLAs utilized multiple doses for safety E-R analyses and 41% (9/22) utilized multiple doses for both safety and efficacy E-R analyses. In recent years, development programs have aligned with Project Optimus, represented by a distinct increase in E-R analyses utilizing data from multiple dose levels. A total of 92% (24/26) of approvals since 2021 included multiple dose levels in their exposure–safety analyses and 69% (18/26) of approvals included multiple doses in both their exposure–safety and exposure–efficacy analyses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of BLA approvals that utilize ≥ 2 dose levels for exposure–response analyses prior to and following Project Optimus. (Created with GraphPad ver. 10.4.1).

Of note, for both E-R and PopPK analyses, adequate collection of PK data should be included within the clinical trial protocols to ensure that the results of these analyses are reliable. PMRs/PMCs related to dose optimization were issued to 8% (4/48) of approvals within this review. Of these four approvals, three received PMRs to conduct or complete a randomized clinical trial that evaluated two or more doses. These clinical trials were to be conducted with sufficient PK sampling timepoints to be able to conduct E-R analyses for safety and efficacy [22,66,98]. The remaining approval received a PMC to conduct E-R analyses for efficacy and safety using data from the ongoing clinical trial and combine the results with the existing E-R analysis. The combined results would then be used to determine if a post-marketing trial was needed to optimize the dose in patients who have low exposures at the approved dose [12].

5.3. Immunogenicity Evaluation

All biologics have the potential to trigger an immune response that may impact both safety and efficacy of a drug. Immune responses to biologics may result in the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) and neutralizing antibodies (nAbs), which could impact the PK and safety and hamper the potential efficacy of a drug. With regards to safety concerns, immune responses elicited by biologics may result in immune-mediated toxicities and adverse reactions such as anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions. When ADAs bind to the drug, the drug can be rapidly cleared from circulation resulting in decreased overall exposure. In addition to increased clearance, nAb binding also may prevent the antibody from binding to its target, rendering it unable to enact its MOA. The immunogenic risk of a biologic molecule should be evaluated through characterization of the incidence and prevalence of ADA and its potential impact on PK, safety, and efficacy. The FDA guidance “Immunogenicity Assessment for Therapeutic Protein Products” [103] provides information regarding immunogenicity assessments.

Immunogenicity was evaluated in all but one (98%; 47/48) of the clinical pharmacology packages evaluated in this review. Generally, samples for immunogenicity testing were obtained throughout clinical trials and were evaluated using a tiered approach. Samples are first analyzed using a screening assay to detect the presence of ADA, followed by a confirmatory assay to obtain ADA titers, and for samples that have been confirmed positive for ADA, a nAb assay is then used to determine the presence of nAb. The potential impact of immunogenicity on the PK, safety, and efficacy of a molecule was then evaluated. The single clinical pharmacology package that did not evaluate immunogenicity received three total PMRs in relation to immunogenicity; two PMRs were issued to submit validation reports for sensitive and accurate ADA and nAb assays and one PMR was issued to conduct a clinical study to assess the ADA/nAb response using validated assays and submit the final study report [23,24].

Overall, 40% (19/48) of approvals were issued PMRs/PMCs to assess the presence and impact on PK, safety, and efficacy by ADA and/or nAb. These PMRs/PMCs were issued due to (1) lack of ADA and/or nAb information in the BLA submission, (2) insufficiencies of the assays, or (3) failure to use a validated assay. Examples of each of these situations are included below.

- Lack of ADA and/or nAb information in the BLA submission: In one clinical pharmacology package, no information on the presence or impact of nAbs was included within the submission. Thus, a PMC was issued to assess the presence of nAb in all patient samples that tested positive for ADA and evaluate the clinical impact on PK, safety, and efficacy [13,14].

- Insufficiencies associated with the assays for ADA and/or nAb measurement: In one clinical pharmacology package, the assay utilized in the Phase I/II studies had a drug tolerance limit below the levels of drug present in a majority of serum samples; thus, an accurate determination of ADA could not be made. A total of three PMRs were issued. Two PMRs were issued to conduct a study to validate assays for both ADA and nAb, and an additional PMR was issued to conduct a study to assess ADA response with the validated assays [7,8].

- Failure to use a validated assay: In another package, a majority of the ADA sampling conducted in the clinical trials were deemed unreliable as the assays used were not validated. A PMC was issued to conduct immunogenicity testing in all patients enrolled in the ongoing confirmatory study and any planned clinical trials using validated assays to characterize the incidence of ADA and nAb and assess the impact of ADA on the PK, safety, and efficacy [45,46].

5.4. Drug–Drug Interactions (DDIs)

In small molecule drug development, clinical DDI studies are conducted in healthy volunteers and molecules are classified as victims or perpetrators based on their potential impact on CYP. Biologics are expected to be catabolized via proteolytic degradation and are not expected to be metabolized via Phase I or II metabolizing enzymes (CYP or UGT). Therefore, they are at low risk to result in DDIs as a victim or perpetrator through these pathways. However, the presence of DDIs and their potential impact on the PK of the investigational product (IP) or co-administered drugs is still evaluated in biologic clinical pharmacology packages [104]. For molecules that are proposed to be used in combination with another therapy (e.g., chemotherapeutic or another mAb), DDI evaluations may be used to assess the potential impact of co-administration on the PK of the IP. Other co-administered drugs that were evaluated for their impact on the PK of a biologic included systemic corticosteroids and tocilizumab (anti-IL-6 mAb). Additional considerations for DDI pathways are highlighted when looking specifically at TCEs and ADCs, as discussed below. A breakdown of DDI potential and monitoring strategies by modality is provided in Table 2.

When addressing the potential for clinically relevant DDIs, most clinical pharmacology packages included a statement to reference the expected clearance pathways of biologics (i.e., proteolytic degradation) and the low likelihood for DDI via CYP or UGT. Of note, due to the potential for cytokine modulation to impact CYP, molecules with potential to elicit cytokine release typically included evaluation of the cytokine release profile as part of DDI assessments. For molecules that do not modulate cytokine release as part of their MOA, a statement on the low likelihood of DDI based on cytokine modulation was included. Based on this review, evaluations for DDIs in oncology mAb development were conducted via PopPK analysis (48% [23/48] of approvals), evaluation of cytokine release (23% [11/48] of approvals), or through development of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model (15% [7/48] of approvals).

In oncology, co-administration of a mAb and a chemotherapeutic or another immunotherapeutic as a combined dosing regimen may limit the potential for immune escape and provide potential for increased efficacy. Of the BLAs in this review, 31% (15/48) had an approved dosing regimen to be used in combination with another therapy. These molecules were typically administered in combination throughout the clinical trials. The evaluation of co-administration with the combination therapy assessed clinically meaningful changes in the PK of the IP, most commonly as a covariate within a PopPK analysis.

As mentioned above, for molecules that modulate cytokine release as part of their MOA, such as TCEs, the cytokine release profiles and their potential impact on CYP and UGT are generally more thoroughly evaluated. Jiang et al. noted that IL-6 EC50 values on CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are 75.2 pg/mL and 51 pg/mL, respectively [105]. However, molecules in this review that exhibited IL-6 concentrations higher than the EC50 values from the literature were not identified to have clinically significant DDIs [71,77]. Another TCE evaluated in this review induced a mean IL-6 concentration of 26 pg/mL, and no clinically relevant interaction was expected for this molecule [83]. Peak cytokine concentrations are expected to occur early after TCE administration including after initiation of step-up dosing up to 14 days after the first full dose, and during and after CRS. The overall DDI risk is still low, as the increase in cytokines is transient and return to baseline quickly.

ADCs have additional risk for DDIs compared to traditional mAbs due to the presence of the small molecule payload and its potential release into circulation. Historically, in vitro studies have shown MMAE to be a substrate for and mainly metabolized by CYP3A4 as well as a substrate for and inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (P-gp). It is generally recommended to monitor patients for adverse reactions if strong CYP3A4 inhibitors are taken concurrently with an MMAE ADC. Of note, the first MMAE ADC to be approved in 2011 conducted a clinical DDI study to evaluate potential for MMAE to cause DDIs [106]. Two of the four MMAE ADC BLAs included in this review referred to this clinical DDI study [35,55]. The other two MMAE ADCs evaluated DDIs utilizing a PBPK model [33,97]. Unconjugated DXd (tecan-ADCs) are substrates for CYP3A and organic anion transporting peptide (OATP), though similar to MMAE ADCs, monitoring is needed only when taken concurrently with strong inhibitors. One of the tecan-ADCs included in this review conducted a clinical DDI study to evaluate the effect of inhibitors of (OATP)1B, and CYP3A on unconjugated tecan, and included co-administration with ritonavir or itraconazole as covariates in the PopPK analysis [37]. The other tecan-ADC did not include drug interaction studies in their BLA submission, but did include information on UGT1A1 involvement in the metabolism of the payload. It was also noted in the BLA that patients with decreased UGT1A1 function due to loss of function alleles exhibited higher incidence of neutropenia. Recommendation to avoid concomitant medications that modulate UGT1A1 function was included in the labeling [41]. Unconjugated calicheamicin (ozogamicin-ADCs) is a substrate for P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by CYP450 or UGT enzymes, with no clinically impactful inhibition on either. The clinical pharmacology package for both ozogamicin ADCs included concomitant administration with other therapies as a covariate in their PopPK analysis as an evaluation of DDI [21,23]. Unconjugated DM4 and its metabolite S-methyl-DM4 show no clinically relevant DDIs, though it is a substrate of CYP3A4 and monitoring of patients is recommended. One of the DM4 ADCs included the administration of CYP3A inhibitors and inducers as a covariate in the PopPK analysis [65]. The clinical pharmacology package for the other DM4 ADC did not include a DDI evaluation [27]. Pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) is a substrate for CYP3A and P-gp according to in vitro studies. The DDI risk for PBD is expected to be low, and available data within PopPK analysis indicates that no dose modifications are required when co-administered with CYP3A and P-gp inhibitors, only monitoring [51].

Table 2.

Summary of DDI potential by modality.

Table 2.

Summary of DDI potential by modality.

| Modality | Payload | DDI Potential | Monitoring | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody | N/A | Not expected | Low likelihood of DDI | N/A |

| ADC | MMAE | Substrate of CYP3A, inhibitor of P-gp | Toxicities associated with ADC payload, especially when coadministration with CYP inhibitors | [21,23,27,33,35,37,41,51,55,65,97,106] |

| DXd | Substrate of CYP3A and OATP; potential substrate of UGT1A1 | |||

| Calicheamicin | Not a substrate of CYP450 enzymes or UGT | |||

| DM4 | Substrate of CYP3A | |||

| PBD | Substrate of CYP3A and P-gp | |||

| TCE | N/A | Elevation of cytokines; IL-6 may impact CYP and UGT | Peak cytokine levels, especially IL-6, during initiation of TCE therapy and first full dose | [71,77,83,105] |

5.5. QT Prolongation Evaluation

It is recommended to evaluate the potential of non-antiarrhythmic drugs to prolong to QT/QTc intervals in the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) E14 guidance [107]. General framework to evaluate the QT/QTc effects of non-antiarrhythmic drugs is also provided in the guidance. For small molecules, lack of impact on the QT interval is typically established through a dedicated thorough QT study (TQT) study. In general, the impact of a molecule on the QT interval compared to placebo is evaluated in healthy volunteers; however, they are sometimes conducted in cancer patients. First-in-human trials in oncology are typically conducted in relapsed/refractory (R/R) patient populations where the use of placebo is not ethically feasible, and therefore, dose/exposure range is used to assess the IP QT prolongation risk.

In general, biologics are not expected to interact with cardiac ion channels and therefore have a low likelihood of impacting the QT interval. Most clinical pharmacology packages evaluated in this review included this statement in their QT assessment. Additionally for ADCs, the circulating concentrations of the cytotoxic small molecule payload is expected to be relatively low and therefore unlikely to impact cardiac ion channels clinically. That being said, nearly all clinical pharmacology packages evaluated included an evaluation of potential impact on the QT interval (96%; 46/48). Two clinical pharmacology packages (4%; 2/48) included a clinical QT study, while five (10%; 5/48) included a QT sub-study, QT study arm, or included collection of QT assessments as a secondary endpoint. Most clinical pharmacology packages (96%; 46/48) collected ECGs or included cardiac monitoring in their clinical trial protocols. In 44% (21/48) of clinical pharmacology packages evaluated, a concentration-QTc analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between PK concentrations and QT prolongation. Ideally, to facilitate the conduct of a concentration-QTc analysis, triplicate 12-lead ECGs were taken with time-matched PK sampling timepoints throughout dose escalation in the Phase I and/or Phase II trials. Other kinds of analyses that were conducted for QT prolongation assessments included by-time analyses (10%; 5/48) and categorical analyses (21%; 10/48).

PMRs related to QT prolongation assessments were issued for two BLA submissions. In one of these instances, FDA review had determined that the potential of the molecule to induce QT interval prolongation had not been fully assessed as analysis was limited by incomplete data. In the clinical trial protocols for this submission, ECG findings were only to be recorded if they were abnormal; therefore, assessment of the QT interval was not performed for all patients. Additionally, for patients who did have QT assessments recorded, a significant proportion (49.5% [202/408]) were missing baseline values. A QT sub-study was included as part of the ongoing confirmatory Phase III trial and a PMR was issued to submit the final QT prolongation evaluation report for the QT sub-study to the FDA [41,42]. The other BLA submission that received a QT/QTc related PMR did not include any ECG information from patients who had been treated. The PMR issued was to conduct a study to determine the effect of the drug on the QT interval in humans [23,24].

Overall, a large majority of clinical pharmacology packages for oncology biologics did not include a dedicated TQT study. However, collection of time-matched triplicate ECGs and PK sampling throughout dose escalation and the conduct of exposure-QTc analyses were generally sufficient to establish lack of risk for QT prolongation.

6. Integrated Discussion and Conclusions

Clinical pharmacology packages ensure proper evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of a drug. Each clinical pharmacology package should be tailored to the molecule, as novel biologic formats and mechanisms create complexities within required assessments. Any gaps in a clinical pharmacology package may result in PMRs/PMCs, something that can be avoided with robust characterization of an IP. Integration of modeling strategies can aid in the evaluation of PK, PD, and ADME characteristics of a biologic and therefore can be used to address clinical pharmacology questions that may have required dedicated clinical studies in small molecule development. PopPK and E-R analyses were utilized extensively in supporting dose and schedule selection throughout this review. PopPK analyses were also utilized to evaluate DDI potential and immunogenicity risk through covariate analysis. In addition, PBPK modeling was utilized to evaluate potential DDIs, though in a small subset of clinical pharmacology packages (15%; 7/48 approvals). TCEs and ADCs carry additional DDI risks, as their structures and mechanisms may influence CYP. Generally, only monitoring is necessary in these circumstances, and for other mAbs, a statement that discusses the expected catabolism through proteolysis may be sufficient. Concentration-QTc analyses were beneficial for evaluation of QT prolongation risk as an alternative to a dedicated clinical TQT study. In the BLAs evaluated, inclusion of time-matched ECGs and PK sampling timepoints in the protocols ofPhase I studies were important to ensure QT/QTc prolongation risk was adequately assessed across a dose range. With regards to immunogenicity assessments, the results of this review indicate that use of validated assays with adequate drug tolerance is crucial to appropriately evaluating the presence of ADA/nAbs and the potential impact on PK, safety, and efficacy of the biologic. Specifically, technical insufficiencies associated with the sensitivity of the assays used for immunogenicity assessments, use of non-validated assays, and/or inadequate collection of PK and immunogenicity samples often resulted in PMRs/PMCs.

To ensure adequacy of the clinical pharmacology package, collection of robust PK/PD data is crucial, particularly related to the ability to conduct PopPK and E-R analyses. The collection of rich PK/PD data during dose escalation in Phase 1 studies provides an opportunity for early understanding of a molecule’s PK/PD characteristics to aid in decision-making later in the development program. Insufficiencies in data collection can result in limitations in labeling and/or issuance PMRs/PMCs from the FDA for further evaluation. These deficiencies may include lack of robust PK sampling at multiple dose levels or within special populations (i.e., patients with renal or hepatic dysfunction, racial or ethnic minorities, etc.). A high degree of planning and awareness is necessary early in development to ensure that appropriate and thorough data collection is conducted. A notable takeaway from this review is an emphasis on inclusion of adequate PK data in specific patient sub-populations to support labeling. Though the inclusion of race/ethnicity as a covariate was seen in almost all PopPK analyses (>90% [more than 44 of 48]), inadequate data from small sample sizes in racial and ethnic minorities did not lead to robust, label supporting data. This lack of PK data resulted in PMRs/PMCs for additional data in racial and ethnic minority populations issued by the FDA in 31% (15/48) of approvals.

Overall, developing a clinical pharmacology package uniquely fit to the IP is key to ensuring a safe and efficacious product reaches patients. Our review has highlighted specific strategies used to characterize the PK, PD, safety, and efficacy of approved biologics in oncology over the course of the past decade. A key shift over the years within the review was the introduction of Project Optimus. The focus to emphasize the early optimization of dosing and the evaluation of multiple dose levels after Phase 1 dose escalation has successfully informed investigators what dose of an IP fits the patient population. This was reflected in the increased utilization of multiple doses in E-R analyses post-introduction of Project Optimus (i.e., Prior to 2021, 41% of approvals utilized multiple dose levels for E-R analyses for efficacy and safety, compared with 69% of approvals post-2021). Future development of biologics in oncology will benefit from leveraging initiatives such as Project Optimus, as the drive to develop optimized therapies will continue to remain a focal point.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G., H.D., and S.B.; investigation, K.G. and H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G. and H.D.; writing—review and editing, K.G., H.D., A.S., and S.B.; visualization, K.G. and H.D.; supervision, A.S. and S.B.; project administration, K.G. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Kate Gallinero (K.G.) and Hunter Daws (H.D.) were employed by the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences at Drake University in collaboration with Vanadro Drug Development Consulting. Authors Sanela Bilic (S.B.) and Amanda Singh (A.S.) were employed by Vanadro Drug Development Consulting. S.B. and A.S. were involved as consultants for Immunocore Limited during the development of tebentafusp (Kimmtrak). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PD | Pharmacodynamics |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| MOA | Mechanism of action |

| ADC | Antibody–drug conjugate |

| TCE | T-cell engager |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| DDI | Drug–drug interaction |

| IV | Intravenous |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| TMDD | Target-mediated drug disposition |

| ADA | Anti-drug antibody |

| PopPK | Population pharmacokinetics |

| E-R | Exposure–response |

| BLA | Biologic license application |

| CDER | Center for Drug Evaluation and Research |

| NDA | Novel Drug Application |

| PMR | Post-marketing requirements |

| PMC | Post-marketing commitment |

| NME | New molecular entity |

| MMAE | Monomethyl auristatin E |

| PBD | Pyrrolobenzodiazepine |

| tAb | Total antibody |

| Cmax | Maximal concentration |

| Clast/Ctrough | Last observed concentration |

| nAb | Neutralizing antibody |

| IP | Investigational product |

References

- US FDA. Guidance for Industry. Optimizing the Dosage of Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products for the Treatment of Oncologic Diseases. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/164555/download (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Drugs@FDA. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- New Drugs at FDA: CDER’s New Molecular Entities and New Therapeutic Biological Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda?from=email%3AnotifyAnalysts (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Postmarketing Requirements and Commitments: Searchable Database. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/pmc/index.cfm (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Dinutuximab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/125516Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dinutuximab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/125516Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Daratumumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/761036Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Daratumumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/761036Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Necitumumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/125547Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Necitumumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/125547Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Elotuzumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/761035Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Elotuzumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/761035Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Atezolizumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/761034Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Atezolizumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2016/761034Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Olaratumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/761038Orig1s000MultiDisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Olaratumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2016/761038Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Avelumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/761049Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Avelumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2017/761049Orig1s000ltredt.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Durvalumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/761069Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Durvalumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2017/761069Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/761040Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Inotuzumab Ozogamicin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2017/761040Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/761060Orig1s000Orig1Orig2s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2017/761060Orig1s000Orig2s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Mogamulizumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/761051Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mogamulizumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2018/761051Orig1s000Ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Moxetumomab Pasudotox. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/761104Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Moxetumomab Pasudotox Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2018/761104Orig1s000Ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Cemiplimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/761097Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cemiplimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2018/761097Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Tagraxofusp. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/761116Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tagraxofusp Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2022/761116Orig1s005ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology Review. Polatuzumab Vedotin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/761121Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Polatuzumab Vedotin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2019/761121Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Enfortumab Vedotin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/761137Orig1s000MultiDiscliplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Enfortumab Vedotin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2019/761137Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/761139Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Trastuzumab Deruxtecan Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2019/761139Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Isatuximab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/761113Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Isatuximab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2020/761113Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Sacituzumab Govitecan. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/761115Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sacituzumab Govitecan Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2020/761115Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tafasitamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/761163Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tafasitamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2020/761163Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Naxitamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/761171Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Naxitamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2020/761171Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Margetuximab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/761150Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Margetuximab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2020/761150Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Dostarlimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/761174Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dostarlimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2021/761174Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Loncastuximab Tesirine. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/761196Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Loncastuximab Tesirine Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2021/761196Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Amivantamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/761210Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Amivantamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2021/761210Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tisotumab Vedotin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/761208Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tisotumab Vedotin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2021/761208Orig1s000_Corrected_ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tebentafusp. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761228Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tebentafusp Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2022/761228Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Nivolumab, Relatlimab (Opdualag). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761234Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Opdualag Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2022/761234Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tremelimumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761270Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tremelimumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761270Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Teclistamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761291Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Teclistamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2022/761291Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Mirvetuximab Sorvtansine. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761310Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mirvetuximab Sorvtansine Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2022/761310Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Mosunetuzumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761263Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mosunetuzumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761263Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Retifanlimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761334Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Retifanlimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761334Orig1s000correctedltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Epcoritamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761324Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Epcoritamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761324Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Glofitamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761309Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Glofitamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761309Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Talquetamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761342Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Talquetamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761342Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Elranatamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761345Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Elranatamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761345Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Toripalimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/761240Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Toripalimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2023/761240Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tislelizumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/761232Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tislelizumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761232Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Tarlatamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/761344Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tarlatamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761344Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Zolbetuximab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/761365Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zolbetuximab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761365Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Zanidatamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/761416Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zanidatamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761416Orig1s000Correctedltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Zenocutuzumab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761352Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zenocutuzumab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761352Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Cosibelimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761297Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cosibelimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2024/761297orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Datopotamab Deruxtecan. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761394Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Datopotamab Deruxtecan Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2025/761394Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Penpulimab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761258Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Penpulimab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2025/761258Orig1s000correctedltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Telisotuzumab Vedotin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761384Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Telisotuzumab Vedotin Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2025/761384Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Multi-Discipline Review. Linvoseltamab. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/761400Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Linvoseltamab Approval Letter. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2025/761400Orig1s000ltr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- US FDA. Guidance for Industry. Population Pharmacokinetics. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/128793/download (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- US FDA. Guidance for Industry. Exposure-Response Relationships—Study Design, Data Analysis, and Regulatory Applications. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/71277/download (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- US FDA. Guidance for Industry. Immunogenicity Testing of Therapeutic Protein Products—Developing and Validating Assays for Anti-Drug Antibody Detection. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/119788/download (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Harvey, R.D.; Morgan, E.T. Cancer, inflammation, and therapy: Effects on cytochrome p450-mediated drug metabolism and implications for novel immunotherapeutic agents. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 96, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, H. Development of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Predict Dis-ease-Mediated Therapeutic Protein-Drug Interactions: Modulation of Multiple Cytochrome P450 Enzymes by Interleukin-6. AAPS J. 2016, 18, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US FDA. Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review. Brentuximab Vedotin. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/125388Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- ICH-E14 Guidance for Industry. The Clinical Evaluation of QT/QTs Interval Prolongation and Proarrhythmic Potential for Non-Antiarrhythmic drugs. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-e-14-clinical-evaluation-qtqts-interval-prolongation-and-proarrhythmic-potential-non-antiarrhythmic-drugs-step-5_en.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.